Abstract

Valbenazine is a selective vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitor approved for tardive dyskinesia treatment by the US Food and Drug Administration; its major active metabolite (NBI‐98782) is a 45‐fold more potent inhibitor of VMAT2 than the parent drug. This study aimed to evaluate the pharmacokinetics (PKs), safety, and tolerability and the effect of cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) genotypes to the PKs after the administration of valbenazine in Korean participants. A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, single‐ and multiple‐dose study was conducted in healthy Korean male participants. The single‐dose study was conducted for both 40 and 80 mg valbenazine and the multiple dose study was conducted for 40 mg. After a 1‐week washout, the 40 mg dose group participants received valbenazine 40 mg or placebo once daily for 8 days. Serial blood samples were collected up to 96 h postdose for PK analysis. The CYP2D6 genotypes of the participants were retrospectively analyzed. A total of 50 participants were randomized, and 43 and 20 participants completed the single‐ and multiple‐dose phases of the study, respectively. After single doses, the PK characteristics of valbenazine and its metabolites were similar between the 40 and 80 mg dose groups. After multiple doses, the mean accumulation ratios of valbenazine and NBI‐98782 were ~1.6 and 2.4, respectively. Plasma concentrations of valbenazine and NBI‐98782 were similar between CYP2D6 normal and intermediate metabolizers. Valbenazine was well‐tolerated in healthy Koreans, and its PK characteristics were similar to results previously reported in Americans.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS THE CURRENT KNOWLEDGE ON THE TOPIC?

Valbenazine is a selective vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitor approved for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia. On the basis of previous studies, the sensitivity of valbenazine to ethnic factors is considered to be low, and a pharmacokinetic (PK) bridging study is considered to be sufficient to determine the valbenazine dose in the Korean population.

WHAT QUESTION DID THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

Does PK features of valbenazine in Koreans differ greatly from those of previous studies? How does the PKs of valbenazine and its active metabolite change by CYP2D6 genotypes? Is valbenazine use considered to be safe in the Korean population?

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD TO OUR KNOWLEDGE?

Valbenazine was well‐tolerated in Koreans, and the PK characteristics of valbenazine in Koreans were comparable to results previously reported in Americans. Plasma concentrations of valbenazine and its active metabolite were similar between CYP2D6 normal metabolizers and intermediate metabolizers.

HOW MIGHT THIS CHANGE CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OR TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCE?

This study result might be a good reference to clinicians who should prescribe valbenazine to Korean patients. This study result might be a good reference to the researchers who are interested in pharmacogenetics and PKs of valbenazine and its metabolites.

INTRODUCTION

Tardive dyskinesia is a major clinical consideration associated with chronic use of dopamine receptor blocking agents, including first‐ and second‐generation antipsychotics, and tardive dyskinesia is characterized by irregular, stereotyped, choreiform, and involuntary movements of the tongue, lips, jaw, face, limbs, and trunk. 1 , 2 Nevertheless, the cessation or dose reduction of antipsychotics that are suspected of causing symptoms is a commonly known strategy for clinicians. 3 However, there is a lack of supportive evidence for this practice. Moreover, the cessation or dose reduction of antipsychotics sometimes triggers the acute aggravation of tardive dyskinesia and disturbs the treatment of psychotic syndromes. 4 , 5 Clozapine is known to be relatively tolerable and may be used as an alternative treatment to dopamine receptor‐blocking antipsychotics, but it still has a risk of agranulocytosis. Thus, there are unmet medical needs for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia. 6 , 7

Valbenazine is a selective vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia. 8 As tardive dyskinesia can be caused by postsynaptic super‐sensitivity of dopamine D2‐receptors, an agent that can block or deplete dopamine can be used as a medical treatment for tardive dyskinesia. 9 VMAT2 is the integral membrane protein that transports monoamines from the cellular cytosol to synaptic vesicles and plays an important role in the release of dopamine. 10 Valbenazine selectively inhibits presynaptic VMAT2 and reversibly reduces the release of dopamine from the pre‐synaptic terminal, which may alleviate the involuntary behaviors of tardive dyskinesia. 11 , 12

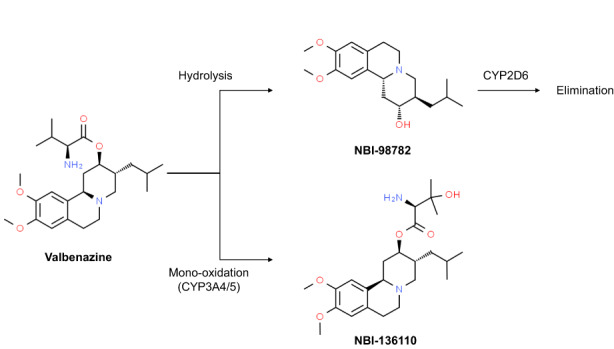

Valbenazine is extensively metabolized by hydrolysis of valine ester to form an active metabolite, [+]‐α‐dihydrotetrabenazine (NBI‐98782), which is further metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 enzyme (Figure 1). In addition, valbenazine is metabolized by CYP3A4/5 to form another active metabolite (NBI‐136110). The NBI‐98782 was the most potent inhibitor of VMAT2 among the parent drug and its metabolites, with its K i (inhibitory constant) of 3.1 nM in an in vitro study. 13 Valbenazine and NBI‐136110 also inhibited human VMAT2, but with ~40–60 times lower affinity (K i were 150 and 220 nM, respectively) than NBI‐98782. In addition, NBI‐98782 showed high specificity to VMAT2 and greatest non‐selectivity to the monoamine receptors compared to the other three dihydrotetrabenazine stereoisomers. 13

FIGURE 1.

Metabolic pathway of valbenazine.

From the various previous clinical and in vitro studies, the sensitivity of valbenazine to ethnic factors is considered to be low. First, its pharmacokinetic (PK) features demonstrated relative dose linearity within the therapeutic dose range from 40 to 80 mg. Second, phase II and III studies illustrated that the efficacy of valbenazine, represented as a change in the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) score from the baseline score in patients with tardive dyskinesia, was dependent on the dose given. 14 , 15 Furthermore, the efficacy of valbenazine was demonstrated in a relatively wide range of doses (25–80 mg). 11 In addition, from the in vitro study result, dose adjustment for valbenazine found out to be unnecessary when used in combination with substrate drugs of CYP1A2, CYP2B6, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2E1, or CYP3A4/5. 8 Even though, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, digoxin, strong CYP3A4 inhibitors/inducers, and strong CYP2D6 inhibitors are known to have significant drug interactions with valbenazine, overall potential of the drug interaction of valbenazine is still considered to be low. 8 Thus, a PK bridging study was considered to be sufficient to determine the valbenazine dose in the Korean population based on existing clinical safety, efficacy, and PK data from other regions.

As the plasma NBI‐98782 concentration is increased in CYP2D6 poor metabolizers (PMs), CYP2D6 genetic polymorphism is one of the important factors that may require dose adjustment of valbenazine. In a previous study, the majority of the East Asian population (about 90%) are categorized into normal or intermediate metabolizers, and only about 0.9% of the East Asians are expected to be PMs. 16 However, CYP2D6 activity on the drug metabolism does not demonstrate an all‐or‐none manner. The frequency of CYP2D5 *10 allele, of which the function is decreased, in the Korean population is known as about 46.2%. 17 Therefore, despite the rare proportion of PMs in Korea, overall mean activity of CYP2D6 is expected to be low. Accordingly, the further pharmacogenomic analysis was designed to find out whether the dose adjustment is necessary in the Korean population.

Based on these understandings, a PK study was conducted to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and PK characteristics of valbenazine in Korean subjects, and the subjects' CYP2D6 genotype were retrospectively analyzed.

METHODS

Study population

Healthy Korean male subjects aged 20–45 years with a body mass index (BMI) between 18.0 and 25.0 kg/m2 were enrolled in the study. Subjects with a history of any clinically significant disease, allergic reactions to any food or valbenazine, a QTc interval >430 ms, or a risk of committing suicide or having any symptoms of major depressive disorder were excluded. The Columbia‐Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C‐SSRS) was used to evaluate suicidal ideation and events, and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI‐II) was used to evaluate the mood state of the subjects. This clinical study (Clinical Research Information Service identifier number: KCT0004667) was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea (H‐1807‐178‐963) and was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice. All of the subjects were fully informed about the study and provided written consent before any study‐related procedures were performed.

Study design

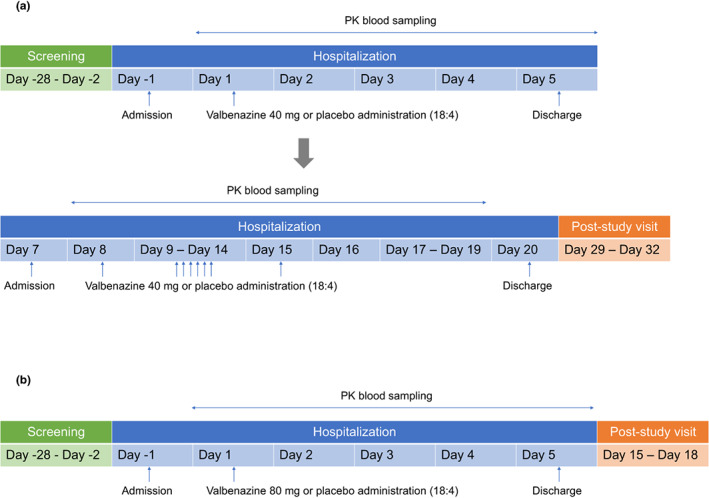

A randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, single‐ and multiple‐dose study was conducted in healthy Korean male subjects. The single‐dose study was conducted for both 40 and 80 mg valbenazine and the multiple dose study was conducted for 40 mg. In every dose group, subjects were randomized to valbenazine or placebo at a ratio of 18:4. In the multiple‐dose study, only the 40 mg dose group subjects from the initial phase received valbenazine 40 mg or placebo once daily for 8 days after a washout period of 7 days (Figure 2). Subjects maintained fasted state 10 h before and 4 h after the study drug administration. A total of 44 subjects were planned to be enrolled: 22 subjects for each dose group. The dose of valbenazine was determined according to the approved doses of valbenazine by the FDA (40 and 80 mg). The administration of the single 80 mg dose and the transition to the 40 mg multiple‐dose phase after the 40 mg single‐dose phase was performed after the evaluation of tolerability data up to the fifth day following a valbenazine 40 mg single dose.

FIGURE 2.

Study design (a) 40 mg dose group, (b) 80 mg dose group. PK, pharmacokinetic.

Determination of plasma concentrations of valbenazine and metabolites

Serial blood samples were collected for PK analysis of valbenazine and its metabolites. In the single‐dose phase, blood samples were collected predose and at 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 8, 12, 18, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after drug administration. In the multiple‐dose phase, blood samples were collected predose (every day) and at 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 8, 12, 18, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after the last dose. Each blood sample was collected in a K2 EDTA tube centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and stored at temperatures below −70°C until the analysis of drug concentration.

Plasma concentrations of valbenazine metabolites (NBI‐98782, NBI‐136110) were determined using a validated high performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method. The liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry system consisted of a mass spectrometry (API4000, AB Sciex Pte. Ltd.) and pump system (LC‐10ATvp, Shimadzu Corp.). To prepare the samples for analysis, a sample of plasma was mixed with acetonitrile in the presence of an internal standard (d6‐NBI‐98854‐2HCl salt for valbenazine; 13C‐NBI‐98782 for NBI‐98782; d6‐NBI‐136110 2HCl salt for NBI‐136110; Neurocrine Biosciences). The mixture was then vortexed for 1 min and centrifuged for 4°C, 2000 g. An aliquot of the supernatant was transferred to an autosampler onto the column at 40°C. Three mobile phases were prepared. Mobile phase A consisted of 5 mM ammonium acetate solution (1000 ml) and ammonium hydroxide solution (1 ml) and mobile phase B consisted of methanol (200 ml), acetonitrile (1800 ml), and ammonium hydroxide solution (2 ml). In addition, mobile phase C consisted of 5 mM ammonium acetate solution (400 ml), methanol (160 ml), acetonitrile (1440 ml), and ammonium hydroxide solution (2 ml). Detection of the precursor‐to‐product ion transition was achieved via electrospray ionization in the positive‐ion mode along with multiple reaction monitoring. The precursor‐to‐product ion pairs of the mass‐to‐charge ratio were 419 to 205 for valbenazine; 425 to 211 for d6‐NBI‐98854‐2HCl salt; 320 to 165 for NBI‐98782; 323 to 167 for 13C‐NBI‐98782; 435 to 302 for NBI‐136110; and 441 to 308 for d6‐NBI‐136110 2HCl salt, respectively. The calibration curves for each analyte had good linearity over the range of 1–500 ng/ml (valbenazine), 0.1–50 ng/ml (NBI‐98782), and 0.2–100 ng/ml (NBI‐136110). The limit of quantification of valbenazine, NBI‐98782 and NBI‐136110 plasma samples were 1.0, 0.1 and 0.2 ng/ml, respectively.

PK analysis

PK parameters including the maximum plasma concentration (C max), time to reach the C max (T max), area under the time‐concentration curve (AUC), apparent total clearance (CL/F), CL/F at steady‐state (CLss/F), apparent volume of distribution during the terminal phase (V z/F), terminal half‐life (t 1/2), ratio of accumulation and linearity factor, were calculated through the noncompartmental method using Phoenix WinNonlin (version 6.3, Certara). The C max and T max were estimated from the observed values. The AUC from time of administration up to the time of the last quantifiable concentration (AUC0–last) was calculated with the linear trapezoidal method, and the AUC from zero to infinity (AUCinf) was calculated as the sum of the AUC0–last and the last measurable concentration divided by the elimination rate constant (λz). The t 1/2 was calculated as t 1/2 = ln2/λz. Accumulation ratio was defined as a ratio of the AUC over 24 h (AUC0–24) on day 15 to the AUC0–24 on day 1. The linearity factor was defined as the ratio of the AUC0–24 on day 15 to the AUCinf on day 1. Metabolic ratio was defined as the ratio of the AUCinf of metabolite to the AUCinf of parent.

Safety and tolerability evaluation

Adverse events (AEs), physical examination findings, vital signs, 12‐lead electrocardiograms, and clinical laboratory test results were monitored for the safety and tolerability evaluation. AEs were monitored by both subject self‐report and investigator routine interview. In addition, the C‐SSRS and BDI‐II scores were also assessed intermittently during the entire trial.

CYP2D6 genotyping

The subjects' CYP2D6 genotypes were retrospectively analyzed because the CYP2D6 enzyme is one of the metabolic pathways of NBI‐98782. Genomic DNA was extracted from the blood sample of each subject and analyzed using an xTAG CYP2D6 kit (Luminex Corporation) according to the manufacturer's instructions by Komabiotech. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction and multiplex Allele Specific Primer Extension was used with Luminex's Universal TAG sorting system on a Luminex 200 platform. Multiple CYP2D6 haplotypes (*2 to *12, *14, *15, *17 *29, *35, and *41) and gene duplication were analyzed. Subjects were classified into four different phenotypes (ultrarapid metabolizer, normal metabolizer [NM], intermediate metabolizer [IM], and PM) by the analyzed genotypes according to a classification method provided in Table S1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Demographic and other baseline data were summarized in safety and tolerability analysis set. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize PK parameters and safety and tolerability parameters. Kruskal–Wallis test was performed to compare PK parameters of valbenazine and NBI‐98782 among different CYP2D6 phenotypes. The hypothesis test was done at the significance level of 0.05.

RESULTS

Study population

A total of 50 subjects were enrolled and, among them, 43 completed the study as planned. A total of 28 subjects were enrolled in the 40 mg single‐dose study group. First, six subjects were enrolled and proceeded with study drug treatment and scheduled PK and safety/tolerability evaluations. However, due to the establishment of a coronavirus disease 2019 risk mitigation strategy, these six subjects were withdrawn from the study. Then, an additional 22 subjects were enrolled, one of whom was dropped before the multiple‐dose study. Thus, a total of 21 subjects completed the 40 mg single‐dose phase and continued to the 40 mg multiple‐dose phase. One subject dropped out before the multiple‐dose study and another subject was withdrawn from the study during the multiple‐dose study part; 20 subjects completed the 40 mg multiple‐dose phase. In the 80 mg single‐dose phase, 22 subjects were enrolled and completed the study as planned. Data from the 50 subjects who received the study drug were used for PK, safety, and tolerability analyses. All subjects were Korean male adults, and there were no CYP2D6 ultra‐rapid metabolizers or PMs. The age, weight, height, BMI, and CYP2D6 phenotypes of the subjects are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of subjects

| Variables | Single dose | Multiple dose | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N = 9) | 40 mg (N = 23) | 80 mg (N = 18) | Placebo (N = 4) | 40 mg (N = 17) | |

| Age, years | 31.8 ± 6.9 | 33.2 ± 5.9 | 31.7 ± 6.1 | 35.8 ± 7.9 | 33.1 ± 6.1 |

| Weight, kg | 66.2 ± 3.4 | 69.0 ± 7.1 | 66.7 ± 8.3 | 66.0 ± 4.7 | 68.6 ± 7.2 |

| Height, cm | 169.9 ± 3.8 | 172.4 ± 5.5 | 173.2 ± 5.8 | 169.8 ± 1.5 | 172.1 ± 5.5 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.0 ± 1.3 | 23.2 ± 1.5 | 22.2 ± 1.9 | 22.9 ± 1.6 | 23.1 ± 1.5 |

| CYP2D6 normal metabolizers | 5 (55.6) | 14 (60.9) | 13 (72.2) | 2 (50.0) | 9 (52.9) |

| CYP2D6 intermediate metabolizers | 4 (44.4) | 9 (39.1) | 5 (27.8) | 2 (50.0) | 8 (47.1) |

Note: Data are presented as the arithmetic mean ± SD, except for CYP2D6 phenotypes that is expressed as the N (%).

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index.

Pharmacokinetics

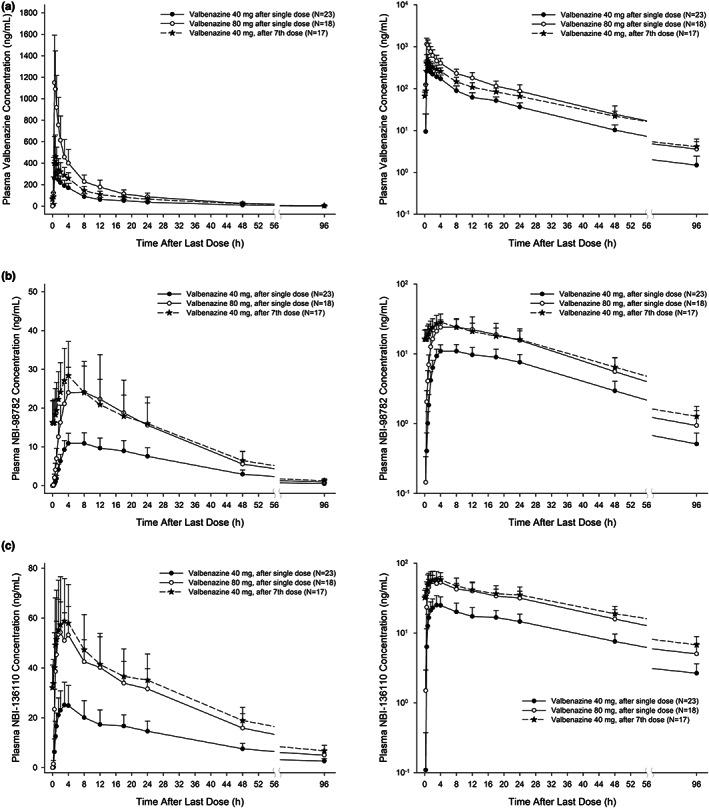

After a single oral administration of valbenazine, plasma concentrations of valbenazine rapidly increased (median T max: 0.5–0.75 h) and showed biphasic elimination with a mean t 1/2 of ~16 h (Figure 3 and Table 2). The plasma concentrations of NBI‐98782 and NBI‐136110 gradually increased (median T max: 2–4 h) and demonstrated monophasic elimination with longer t 1/2 values than valbenazine (Figure 3 and Table 2). The mean t 1/2 of NBI‐98782 was ~18 h and that of NBI‐136110 was ~28 to 30 h. The PK characteristics of valbenazine and its metabolites were similar between the 40 and 80 mg dose groups (Table 2).

FIGURE 3.

Mean plasma concentration‐time profile of valbenazine (a), NBI‐98782 (b), and NBI‐136110 (c) after single oral dose of 40 and 80 mg and after multiple oral doses of valbenazine 40 mg (left: linear scale, right: semi‐log scale).

TABLE 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters

| Korean subjects | US subjects a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single dose | Multiple dose | Single dose | |||

| Parameters | 40 mg | 80 mg | 40 mg | 50 mg | 75 mg |

| (N = 23) | (N = 18) | (N = 17) | (N = 5) | (N = 8) | |

| Valbenazine | |||||

| C max, ng/ml | 372 ± 139 | 1200 ± 369 | 526 ± 205 | 412 ± 236 | 788 ± 220 |

| T max, h | 0.75 [0.5–1.5] | 0.5 [0.5–0.75] | 0.75 [0.5–3] | 0.5 [0.3–4.0] | 1.0 [0.3–2] |

| AUC0–24, h ng/ml | 2240.3 ± 540.7 | 5973.6 ± 1792.3 | 3553.9 ± 842.2 | ||

| AUCinf, h ng/ml | 3061.0 ± 755.6 | 7931.5 ± 2666.9 | 4120 ± 1680 | 7170 ± 1540 | |

| CL/F or CLss/F, L/h | 14.07 ± 4.63 | 10.92 ± 2.77 | 12.11 ± 4.21 | 14.1 ± 6.22 | 11.0 ± 2.81 |

| V z/F, L | 328.21 ± 101.42 | 241.89 ± 59.69 | 331.36 ± 98.78 | ||

| t 1/2, h | 16.36 ± 2.37 | 15.61 ± 2.62 | 19.2 ± 2.14 | 19 ± 2.4 | 20 ± 2.4 |

| Ratio of accumulation | 1.553 ± 0.175 | ||||

| Linearity factor | 1.137 ± 0.138 | ||||

| NBI‐98782 | |||||

| C max, ng/ml | 11.3 ± 2.77 | 26.1 ± 10.2 | 28.6 ± 8.67 | 20.4 ± 7.51 | 31.7 ± 11.4 |

| T max, h | 4 [4–18] | 4 [4–12] | 4 [2–8] | 4.0 [4.0–6.0] | 6.0 [4.0–12] |

| AUC0–24, h ng/ml | 212.6 ± 55.4 | 471.0 ± 182.8 | 505.2 ± 152.3 | ||

| AUCinf, h ng/ml | 422.2 ± 120.7 | 878 ± 384.8 | 575 ± 350 | 1150 ± 706 | |

| t 1/2, h | 18.65 ± 1.85 | 17.77 ± 2.34 | 20.4 ± 1.81 | 19 ± 2.4 | 20 ± 2.4 |

| Ratio of accumulation | 2.369 ± 0.321 | ||||

| Linearity factor | 1.205 ± 0.169 | ||||

| Metabolic ratio, % | 19.07 ± 7.29 | 14.99 ± 5.66 | 25.41 ± 10.04 | ||

| NBI‐136110 | |||||

| C max, ng/ml | 26.2 ± 8.6 | 57.2 ± 13.1 | 63 ± 17.9 | ||

| T max, h | 4 [0.75–18] | 2 [1.5–4] | 3 [1–4] | ||

| AUC0–24, h ng/ml | 436.7 ± 129.2 | 952.6 ± 214.5 | 1049.6 ± 298.8 | ||

| AUCinf, h ng/ml | 1047.6 ± 293.2 | 2183.4 ± 553.3 | |||

| t 1/2, h | 30.65 ± 5.24 | 28.03 ± 5.26 | 32.88 ± 5.11 | ||

| Ratio of accumulation | 2.306 ± 0.391 | ||||

| Linearity factor | 0.941 ± 0.142 | ||||

| Metabolic ratio, % | 32.92 ± 3.24 | 27.17 ± 3.06 | 48.04 ± 6.44 | ||

Note: Data are presented as the arithmetic mean ± SD, except for T max that is expressed as the median [minimum–maximum].

Abbreviations: AUC0–24, area under the plasma concentration‐time curve from 0–24‐h; AUCinf, AUC from zero to infinity; CL/F, apparent oral clearance; CLss/F, apparent oral clearance at steady state; C max, maximum plasma concentration; T max, time to reach C max; V z/F, apparent volume of distribution; t 1/2, terminal elimination half‐life.

Data from US subject was adopted from a previous study results. 18

After multiple oral once daily administrations of valbenazine, the mean accumulation ratios of valbenazine and NBI‐98782 were ~1.6 and 2.4, respectively. In addition, no time‐ or dose‐dependent changes were observed in the PK parameters of valbenazine and its metabolites (Figure 3 and Table 2). The PK characteristics of valbenazine and its metabolites were similar after the single and multiple doses of valbenazine (Table 2) and the linearity factors of valbenazine, NBI‐98782 and NBI‐136110 were close to 1 (Table 2).

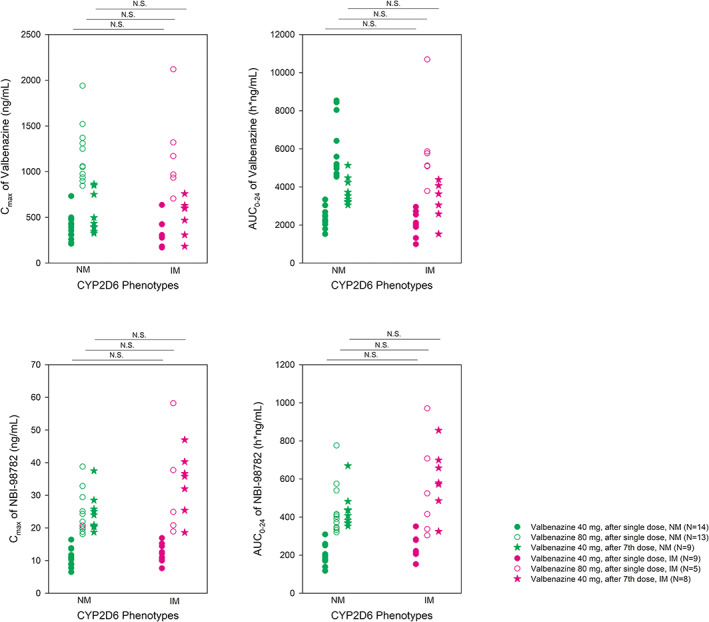

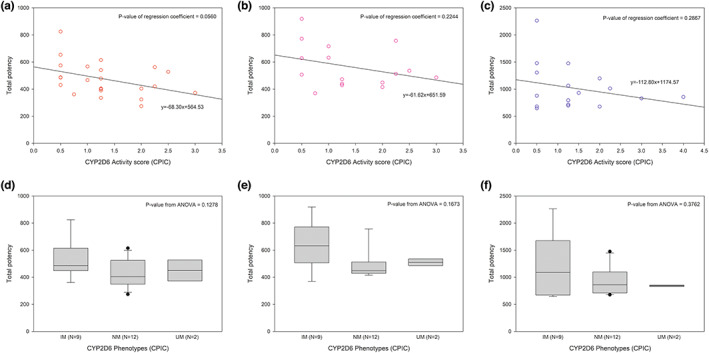

The plasma concentrations of valbenazine and NBI‐136110 showed no significant difference between CYP2D6 NM and IM phenotypes. The mean C max and AUC0–24 of valbenazine and NBI‐98782 showed no significant difference between CYP2D6 NM and IM phenotypes (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Distribution of C max and AUC0–24 of valbenazine and C max, AUC0–24, and metabolic ratio of its metabolite (NBI‐98782) after a single oral dose of valbenazine 40 and 80 mg and after multiple once‐daily oral doses of valbenazine 40 mg, according to CYP2D6 phenotype. AUC0–24, area under the time‐concentration curve from time of administration up to the time of the last quantifiable concentration; C max, maximum plasma concentration; IM, intermediate metabolizer; NM, normal metabolizer; N.S., not significant.

Safety and tolerability

The single administration of valbenazine 40 and 80 mg and the multiple administration of valbenazine 40 mg were well‐tolerated in the subjects. A total of 13 treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs) were reported with “poor quality sleep” in the 40 mg single‐dose group and “somnolence” in the 40 mg multiple‐dose group being the only AEs reported in more than one subject (Table 3). All other TEAEs were reported in only one subject. Of those TEAEs, 11 cases were evaluated to be related to valbenazine administration and categorized as adverse drug reactions (ADRs). There were no serious AEs reported, and the severity of all AEs was mild. The severity of AEs was evaluated according to National Cancer Institute ‐ Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events grading. Among the findings of physical examinations, vital signs, electrocardiograms, and clinical laboratory test results, an increase in blood creatinine and prolonged QT in electrocardiograms were reported as ADRs; these ADRs were observed after the single dose of 40 and 80 mg, respectively. The C‐SSRS results showed that there were no subjects who showed suicidal thoughts after valbenazine administration. The average BDI‐II scores tended to decrease after the administration of the study drugs.

TABLE 3.

Summary of TEAEs

| System organ class | Single‐dose | Multiple‐dose | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred term | Placebo (N = 9) | 40 mg (N = 23) | 80 mg (N = 18) | Placebo (N = 4) | 40 mg (N = 17) |

| Any system organ class | 0 | 4 (17.4) | 2 (11.1) | 1 (25.0) | 6 (35.3) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) |

| Decreased appetite | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) |

| Insomnia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) |

| Nervous system disorder | 0 | 2 (8.7) | 1 (5.6) | 1 (25.0) | 2 (11.8) |

| Dizziness | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 1 (5.9) |

| Headache | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.6) | 1 (25.0) | 0 |

| Poor sleep quality | 0 | 2 (8.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Somnolence | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (11.8) |

| Eye disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 0 |

| Vision blurred | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 0 |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 0 |

| Rhinorrhea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (25.0) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.6) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (17.6) |

| Nausea | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.6) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (5.9) |

| Abdominal pain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) |

| Abdominal pain lower | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) |

| Oral discomfort | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) |

| Pruritis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (11.8) |

| Fatigue | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) |

| Peripheral swelling | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.9) |

| Investigations | 0 | 2 (8.7) | 1 (5.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Blood creatinine increased | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Electrocardiogram QT prolonged | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Liver function test increased | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Note: Data are presented as the N (%).

Abbreviation: TEAEs, treatment‐emergent adverse events.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and PK characteristics of valbenazine for the first time in Korean subjects. Valbenazine was well‐tolerated at a single dose up to 80 mg and at multiple once‐daily doses of 40 mg for 8 days in healthy Korean subjects, based on the resulting AEs, physical examination findings, vital signs, 12‐lead electrocardiograms, and clinical laboratory test results. Valbenazine showed linear PK characteristics after single and multiple doses. The PK parameters of valbenazine, including the T max, t 1/2, CL/F, and V z/F, were comparable between the 40 and 80 mg dose groups. Additionally, from the linearity factors observed, we evaluated that there were no changes in PK characteristics that were dependent on the number of administered doses.

The PK characteristics of valbenazine in Koreans were similar to the results previously reported in (United States) US subjects. In that study, the mean ± SD of CL/F of valbenazine after single oral dose of valbenazine 50 and 75 mg were 14.1 ± 6.22 L/h and 11.0 ± 2.81 L/h, respectively, which were similar to those of Korean subjects (Table 2). 11 , 18 In addition, the mean ± SD of t 1/2 and the T max were comparable between US subjects and Korean subjects (Table 2). 18 Furthermore, after the once daily multiple doses of 50 and 100 mg valbenazine in US subjects, the accumulation index of valbenazine and NBI‐98782 was ~1.5 and 2.6, respectively, which was also similar to those of Korean subjects. 18

In a previous study, no significant differences were found in prevalence of tardive dyskinesia among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanic patients. 19 In addition, there are no other study results suggesting the significant ethnic difference in genetic polymorphisms related to VMAT2. Thus, the pathophysiology and treatment guidelines of tardive dyskinesia and the mechanism of action of valbenazine are not anticipated to be changed by the ethnicity of patients. Therefore, considering the exposure‐response relationship found in previous clinical studies in US patients, the approved valbenazine dose regimen (i.e., a dose between 40 and 80 mg) can also be recommended for Korean patients.

The greatest interest from the pharmacogenetic analysis in this study might be whether the dose adjustment should be considered to patients by their CYP2D6 polymorphisms. Thus, as the ratio of selectivity of valbenazine and NBI‐98782 to VMAT2 is known to be about 1:50, we defined new end point, “total potency,” which can expect the pharmacological activity after the administration of valbenazine. Equation ( ), AUCinf, and AUCtau,ss was used in the calculation for single dose group and multiple dose group, respectively.

| (1) |

In addition to the result already described above, comparison of total potency among different CYP2D6 functionalities might be stronger evidence to the determination of dose adjustment of valbenazine. Although the result above was analyzed based on the predefined phenotyping method (Table S1), in this further analysis, we used a categorization recommended in the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guideline for the further specification of functionalities of each genotype. 16

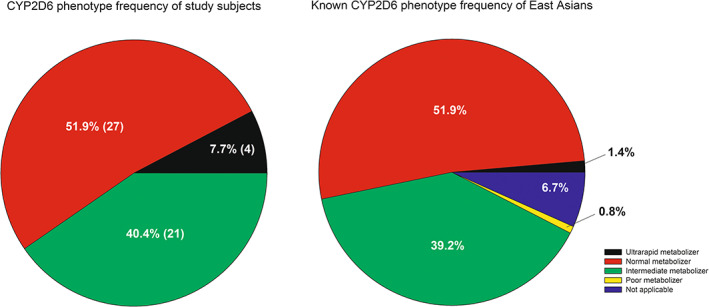

Although the total potency tends to slightly decrease as CYP2D6 activity score decreases, there was no statistical significance in those tendency. In addition, there was also no significant difference among the three different phenotypes (Figure 5). The overall proportion of the phenotype observed in the study was also similar with those with known proportion expected in east Asian population (Figure 6). This supports that our study result well represents the population PKs of valbenazine in Koreans. As the expected activity of active moieties were comparable among various CYP2D6 functionalities, dose adjustment will not be required for Korean CYP2D6, except for CYP2D6 PM which were not observed in this study.

FIGURE 5.

Distribution of total potency by activity scores and phenotypes of CYP2D6 (Activity scores and phenotypes were drawn from CPIC guideline 16 ; (a, d): 40 mg single dose, (b, e): 40 mg multiple doses, (c, f): 80 mg single dose). CPIC, Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium.

FIGURE 6.

Comparison of CYP2D6 phenotype proportions in this study and previously predicted phenotype frequency in east Asians. Phenotyping was done by the method recommended in the CPIC guideline 16 ; data of left diagram are displayed as percentage of subjects (number of subjects). CPIC, Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium.

Our study has several limitations. First, the PK and safety profile of valbenazine were not evaluated in Korean CYP2D6 PMs. As the CYP2D6 PMs are rare in Koreans, the sample size (N = 50) of this study were not enough to recruit at least one CYP2D6 PM. Second, there are no female subjects in the study because only male subjects were enrolled in the previous phase I clinical trial performed in US subjects. Our study was also designed to enroll healthy male subjects to control possible confounding factors which may attribute to unconclusive study result. Conclusively, the lack of clinical pharmacology data in CYP2D6 PMs or female subjects may limit safe and effective use of valbenazine in some Korean patients. However, as the study result is sufficient enough to demonstrate that there is no significant difference in PKs by the ethnicity, dosage adjustment for CYP2D6 PMs in Koreans could be done in the same manner as what the FDA recommends. Still, further studies evaluating the PKs of valbenazine in various populations including CYP2D6 PMs and women is expected to be conducted for effective and safer use of valbenazine.

In conclusion, valbenazine was well‐tolerated after a single dose up to 80 mg and multiple daily doses at 40 mg in Korean healthy subjects, and the PK characteristics were comparable to the previously reported results in American subjects. Furthermore, the overall exposure of active moieties of valbenazine was found out to be rarely affected by CYP2D6 polymorphism. These findings support the consistent use of the previously approved valbenazine dose regimen in Korean patients with tardive dyskinesia.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

W.K.C., I.H., B.K., J.J., K.‐S.Y., and J.O. wrote the manuscript. I.H. designed the research. W.K.C., B.K., J.J., I.‐J.J., and J.O. performed the research. W.K.C. and J.O. analyzed the data.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was sponsored by Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Korea Co., Ltd.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no competing interests for this work.

Supporting information

Appendix S1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Statistical analysis was conducted by Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation.

Chung WK, Hwang I, Kim B, et al. Pharmacokinetics, safety and tolerability of valbenazine in Korean CYP2D6 normal and intermediate metabolizers. Clin Transl Sci. 2023;16:512‐523. doi: 10.1111/cts.13466

REFERENCES

- 1. Tarsy D, Lungu C, Baldessarini RJ. Epidemiology of tardive dyskinesia before and during the era of modern antipsychotic drugs. Handb Clin Neurol. 2011;100:601‐616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Margolese HC, Chouinard G, Kolivakis TT, Beauclair L, Miller R. Tardive dyskinesia in the era of typical and atypical antipsychotics. Part 1: pathophysiology and mechanisms of induction. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(9):541‐547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Egan MF, Apud J, Wyatt RJ. Treatment of tardive dyskinesia. Schizophr Bull. 1997;23(4):583‐609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gardos G, Cole JO, Rapkin RM, et al. Anticholinergic challenge and neuroleptic withdrawal: changes in dyskinesia and symptom measures. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41(11):1030‐1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dixon L, Thaker G, Conley R, Ross D, Cascella N, Tamminga C. Changes in psychopathology and dyskinesia after neuroleptic withdrawal in a double‐blind design. Schizophr Res. 1993;10(3):267‐271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pardis P, Remington G, Panda R, Lemez M, Agid O. Clozapine and tardive dyskinesia in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(10):1187‐1198. doi: 10.1177/0269881119862535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alvir JMJ, Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, Schwimmer JL, Schaaf JA. Clozapine‐induced agranulocytosis – incidence and risk factors in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(3):162‐167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc . INGREZZATM (valbenazine). US Food and Drug Administration Website.

- 9. Caroff SN. Recent advances in the pharmacology of tardive dyskinesia. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2020;18(4):493‐506. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2020.18.4.493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eiden LE, Schäfer MK, Weihe E, Schütz B. The vesicular amine transporter family (SLC18): amine/proton antiporters required for vesicular accumulation and regulated exocytotic secretion of monoamines and acetylcholine. Pflügers Arch. 2004;447(5):636‐640. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1100-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O'Brien CF, Jimenez R, Hauser RA, et al. NBI‐98854, a selective monoamine transport inhibitor for the treatment of tardive dyskinesia: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. Movement Dis. 2015;30(12):1681‐1687. doi: 10.1002/mds.26330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bernstein AI, Stout KA, Miller GW. The vesicular monoamine transporter 2: an underexplored pharmacological target. Neurochem Int. 2014;73:89‐97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Grigoriadis DE, Smith E, Hoare SRJ, Madan A, Bozigian H. Pharmacologic characterization of valbenazine (NBI‐98854) and its metabolites. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2017;361(3):454‐461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kane JM, Correll CU, Liang GS, Burke J, O'Brien CF. Efficacy of Valbenazine (NBI‐98854) in treating subjects with tardive dyskinesia and schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2017;47(3):69‐76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marder SR, Singer C, Lindenmayer JP, et al. A phase 3, 1‐year, open‐label trial of valbenazine in adults with tardive dyskinesia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2019;39(6):620‐627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brown JT, Bishop JR, Sangkuhl K, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guideline for cytochrome P450 (CYP)2D6 genotype and atomoxetine therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2019;106(1):94‐102. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Byeon J‐Y, Kim Y‐H, Lee C‐M, et al. CYP2D6 allele frequencies in Korean population, comparison with East Asian, Caucasian and African populations, and the comparison of metabolic activity of CYP2D6 genotypes. Arch Pharm Res. 2018;41(9):921‐930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Luo R, Bozigian H, Jimenez R, Loewen G, O'Brien CF. Single dose and repeat once‐daily dose safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of valbenazine in healthy male subjects. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2017;47(3):44‐52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sramek J, Roy S, Ahrens T, Pinanong P, Cutler NR, Pi E. Prevalence of tardive dyskinesia among three ethnic groups of chronic psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Serv. 1991;42(6):590‐592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1.