Background

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a rare, inflammatory neutrophilic disease that is characterized by rapidly progressing, painful skin ulcers with peripheral, violaceous erythema and undermined borders.1, 2, 3 While the pathophysiology of PG has not been fully elucidated, pathogenesis has been largely attributed to pathergy. Upon trauma, keratinocytes release interleukin 36 (IL-36) which is thought to play a role in PG pathogenesis and neutrophil recruitment.4,5

To date, there is no standardized treatment for PG. Rapidly progressing cases require early systemic therapies such as prednisone, cyclosporine and anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapies to contain lesions and halt spread.3,6, 7, 8

Spesolimab is an interleukin (IL)-36 receptor blocker that was recently approved for generalized pustular psoriasis (GPP).9 Bachelez et al9 demonstrated in a phase 2 randomized trial that spesolimab treatment resulted in significant clearing of GPP lesions compared to placebo. Given similar mechanisms, we hypothesized that targeting IL-36 in refractory, ulcerative, PG may also result in resolution of a patients’ lesions.

Prior to its approval, spesolimab was obtained for emergency investigational novel drug use in PG (eIND 163533). Permission to administer spesolimab to patient #1 was approved by our institutional review board and the Food and Drug Administration for 4 doses of 900 mg every 4 weeks for 16 weeks. Patient #2 was infused after Food and Drug Administration approval of spesolimab for GPP flares and was prescribed for off-label use.

Case report

Patient #1

A 75-year-old male with no significant past medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with a 4-month history of non-healing, growing ulcers subsequent to Mohs surgery for basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas on his left ear, right cheek, chest, right forehead, and left temple. A biopsy of the sites revealed predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate with no signs of infection. At this time, the patient was diagnosed with postoperative, ulcerative PG.

Our patient failed 8 months of prednisone therapy (ranging from 60 mg/d-20 mg/d), 3 months of adalimumab 40 mg every 2 weeks and 1 month of adalimumab 40 mg weekly therapy, 1 month of cyclosporine 5 mg/kg therapy, and 3 rounds of intralesional triamcinolone injections. Attempts to taper immunosuppressive medication resulted in disease flare and enlarging lesions. Thus, the patient initiated experimental spesolimab treatment while continuing 30 mg/d prednisone and cyclosporine 5 mg/kg/day. When the patient returned for his second treatment at week 5, he was found to have profound regression of lesion size on his left face, right cheek, and chest (Fig 1). Skin over the crater-like lesion on his right cheek had fully re-epithelized. Purulent discharge had resolved and the patient reported resolution of pain. The patient tolerated a rapid taper of prednisone from 60 mg daily to 3 mg daily and cyclosporine from 5 mg/kg/d to 1.5 mg/kg/d over 5 weeks with dramatic improvement in his condition. He completed 4 900 mg spesolimab infusions and saw complete resolution of 1 of his 4 lesions and significant continued improvement in the remaining lesions. Today, he is maintained on every 4-week spesolimab 900 mg infusions and low dose prednisone and cyclosporine treatment given his extensive disease. The patient continues to improve. Of note, the patient developed epididymitis at week 3 of treatment. He was treated with a 1-month course of doxycycline and resumed treatment without any further complications over the 16-week treatment period.

Fig 1.

75-year-old male pyoderma gangrenosum. A-C, Prior to Spesolimab treatment ((A) right cheek, (B) left face, (C) chest). D-F, Five weeks after first 900 mg infusion of spesolimab ((D) right cheek, (E) left face, (F) chest).

Patient #2

A 39-year-old female with a complex medical history of systemic lupus erythematosus, mixed connective tissue disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and scleroderma presented to clinic with multiple, non-healing ulcers on her upper and lower extremities upon stopping long term use mycophenolate mofetil and prednisone. The patient’s treatment regimen consisted of cyclosporine 4 mg/kg, prednisone 60 mg/d, hydroxychloroquine 200 mg/d, and intravenous immune globulin 2 g/kg every 4 weeks. Biopsy of her lesions showed ulceration with suppurative inflammation with no sign of infectious etiology. Due to the patient’s refractory disease, 900 mg spesolimab was administered while maintaining the patient on cyclosporine 4 mg/kg and 30 mg/d prednisone, and 400 mg/d hydroxychloroquine. Within 48 hours of spesolimab infusion, the patient had reduction in oozing of the ulcers on arms and legs with dramatic improvement in pain. In the following weeks, the size of the ulcers began to reduce with significant re-epithelization of the ulcer base (Fig 2). The patient ultimately only needed 2 900 mg spesolimab infusions separated by 4 weeks. She saw complete resolutions of her lesions and was tapered off cyclosporine and remains on 20 mg/d prednisone and 200 mg hydroxychloroquine for her other rheumatological conditions. No adverse effects were observed during or after spesolimab treatment.

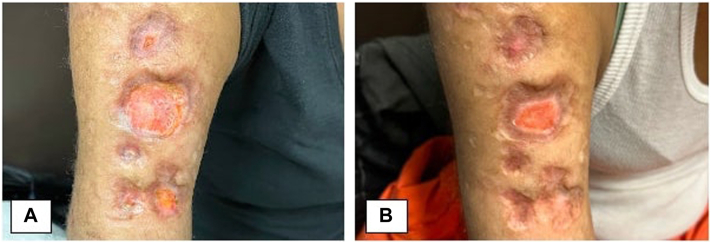

Fig 2.

39-year-old female pyoderma gangrenosum. A, Prior to spesolimab treatment—right upper arm. B, Four weeks after first 900 mg infusion of spesolimab—right upper arm.

Discussion

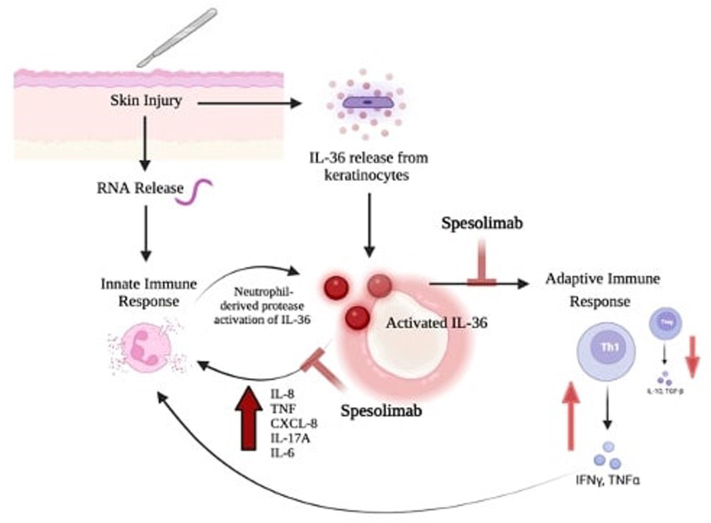

IL-36 is a member of the interleukin 1 cytokine family, which has been implicated in neutrophilic inflammation and the pathogenesis of PG.4,5 In response to IL-36, keratinocytes increase pro-inflammatory signals and skew T cell-differentiation.4,10,11 Taken together, IL-36 affects both the innate and adaptive immune system leading to an unrelenting, pro-inflammatory cycle (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Interleukin 36 (IL-36) plays key role in the inflammatory cycle of pyoderma gangrenosum.4,10,11 Upon skin injury, there is RNA release which activates the innate immune response and leads to neutrophil activation and degranulation. At the same time, keratinocyte injury leads to IL-36 release. Simultaneous occurrence of these events leads to activation of IL-36 by neutrophil-derived proteases. Activated IL-36 leads to increased expression of pro-inflammatory, neutrophil recruiting cytokines interleukin 8, TNF, CXCL-8, interleukin 17A, and interleukin 6. Further, IL-36 activation also leads to skewed Th1 differentiation with decreased Treg differentiation; thereby amplifying the inflammatory response and progression of disease. Spesolimab, an IL-36 receptor blocker, inhibits pro-inflammatory downstream effects of activated IL-36; thereby breaking the inflammatory cycle in pyoderma gangrenosum. CXCL-8, CXC-motif chemokine ligand-8; IL-6, interleukin 6; IL-8, interleukin 8; IL-17A, interleukin 17A; IL-36, interleukin 36; INF-α, interferon- α; INF-y, interferon-γ; Th1, T helper 1 cell; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

(Figure made courtesy of Biorender.com).

We hypothesize that in our patients spesolimab effectively blocked the IL-36 receptor and thereby halted the PG inflammatory cycle. Our patients’ rapid response to spesolimab with significant regeneration of the epithelium within weeks, further suggests that IL-36 plays a central role in the pathogenesis of PG and likely other neutrophilic diseases. Limitations to be considered are that our patients were treated with concomitant immunosuppressive therapies given the extent of their disease. However, both patients experienced noticeable improvement in their condition within 72 hours of infusion, suggesting a direct effect of spesolimab.

Spesolimab is a new treatment; thus, long-term effects of the drug are unknown. During clinical trials for GPP, there were no adverse events that led to discontinuation of the drug.9 Serious adverse events consist of drug reaction with eosinophilia, urinary tract infection, and drug-induced hepatic injury, and arthritis.9 Further studies will be important to evaluate long-term safety and establish a new line of treatment for patients suffering from this debilitating disease.

Conflicts of interest

Dr Lebwohl is an employee of Mount Sinai and receives research funds from: Abbvie, Amgen, Arcutis, Avotres, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cara Therapeutics, Dermavant Sciences, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Inozyme, Janssen Research & Development, LLC, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Regeneron, and UCB, Inc. Dr Lebwohl is also a consultant for AnaptysBio, Arcutis, Inc, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Aristea Therapeutics, Avotres Therapeutics, BioMX, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Brickell Biotech, Castle Biosciences, Corevitas, Dermavant Sciences, Evommune, Inc, Facilitatation of International Dermatology Education, Forte Biosciences, Foundation for Research and Education in Dermatology, Hexima Ltd, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mindera, National Society of Cutaneous Medicine, New York College of Podiatric Medicine, Pfizer, Seanergy, SUN Pharma, Verrica, and Vial. Dr Khattri is an employee of Mount Sinai and receives research funds from Leo Pharma, Abbvie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Celgene, and Acelyrin. Dr Khattri is also a consultant for Leo, Abbvie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Regeneron, Sanofi, and UCB. Author Guénin has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

IRB approval status: Permission to administer spesolimab to patient #1 was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital.

Patient consent: Consent for publication of all patient photographs and medical information was obtained by patient prior to article submission. Both patients in this case report gave consent for their photographs and medication information to be published in print and online and with the understanding this information may be publicly available

References

- 1.Min M.S., Kus K., Wei N., et al. Evaluating the role of histopathology in diagnosing pyoderma gangrenosum using Delphi and PARACELSUS criteria: a multicentre, retrospective cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2022;186(6):1035–1037. doi: 10.1111/bjd.20967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xu A., Balgobind A., Strunk A., Garg A., Alloo A. Prevalence estimates for pyoderma gangrenosum in the United States: an age- and sex-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(2):425–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alavi A., French L.E., Davis M.D., Brassard A., Kirsner R.S. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an update on pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(3):355–372. doi: 10.1007/s40257-017-0251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henry C.M., Sullivan G.P., Clancy D.M., Afonina I.S., Kulms D., Martin S.J. Neutrophil-derived proteases escalate inflammation through activation of IL-36 family cytokines. Cell Rep. 2016;14(4):708–722. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kolios A.G.A., Maul J.-T., Meier B., et al. Canakinumab in adults with steroid-refractory pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(5):1216–1223. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan M.H., Gordon M., Lebwohl O., George J., Lebwohl M.G. Improvement of Pyoderma gangrenosum and psoriasis associated with Crohn disease with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137(7):930–933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooklyn T.N., Dunnill M.G., Shetty A., et al. Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55(4):505–509. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.074815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pomerantz R.G., Husni M.E., Mody E., Qureshi A.A. Adalimumab for treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157(6):1274–1275. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bachelez H., Choon S.E., Marrakchi S., et al. Trial of spesolimab for generalized pustular psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(26):2431–2440. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2111563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrier Y., Ma H.L., Ramon H.E., et al. Inter-regulation of Th17 cytokines and the IL-36 cytokines in vitro and in vivo: implications in psoriasis pathogenesis. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(12):2428–2437. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yuan Z.C., Xu W.D., Liu X.Y., Liu X.Y., Huang A.F., Su L.C. Biology of IL-36 signaling and its role in systemic inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2532. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]