Key Points

Question

How did enrollment in Medicare Advantage among beneficiaries with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) change after the implementation of the 21st Century Cures Act (which allowed enrollment de novo in Medicare Advantage for patients with ESRD), and what were the characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD who switched from traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage?

Findings

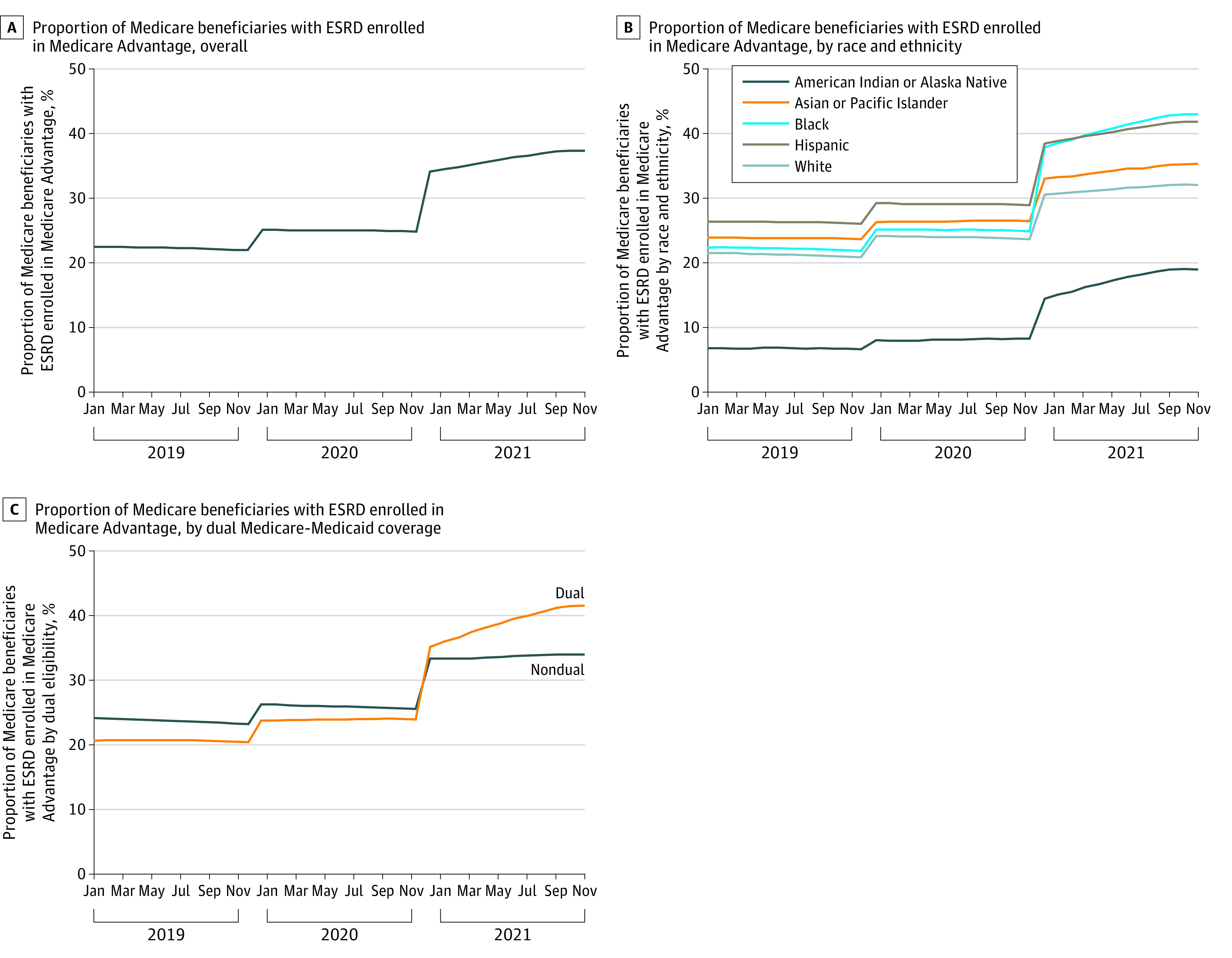

In this cross-sectional study of 575 797 Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD, the proportion enrolled in Medicare Advantage increased by 51%. Increases were largest among Black, Hispanic, and dual-eligible (Medicare and Medicaid) beneficiaries.

Meaning

Among people with ESRD, increases in Medicare Advantage enrollment in the first year after implementation of the 21st Century Cures Act were substantial, particularly among dual-eligible beneficiaries and those from racial or ethnic minority populations.

Abstract

Importance

Before 2021, most Medicare beneficiaries with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) were unable to enroll in private Medicare Advantage (MA) plans. The 21st Century Cures Act permitted these beneficiaries to enroll in MA plans effective January 2021.

Objective

To examine changes in MA enrollment among Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD after enactment of the 21st Century Cures Act overall and by race or ethnicity and dual-eligible status.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional time-trend study used data from Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD (both kidney transplant recipients and those undergoing dialysis) between January 2019 and December 2021. Data were analyzed between June and October 2022.

Exposures

21st Century Cures Act.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcomes were the proportion of Medicare beneficiaries with prevalent ESRD who switched from traditional Medicare to MA between 2020 and 2021 and those with incident ESRD who newly enrolled in MA in 2021. Individuals who stayed in traditional Medicare were enrolled in 2020 and 2021 and those who switched to MA were enrolled in traditional Medicare in 2020 and MA in 2021.

Results

Among 575 797 beneficiaries with ESRD in 2020 or 2021 (mean [SD] age, 64.7 [14.2] years, 42.2% female, 34.0% Black, and 7.7% Hispanic or Latino), the proportion of beneficiaries enrolled in MA increased from 24.8% (December 2020) to 37.4% (December 2021), a relative change of 50.8%. The largest relative increases in MA enrollment were among Black (72.8% relative increase), Hispanic (44.8%), and dual-eligible beneficiaries with ESRD (73.6%). Among 359 617 beneficiaries with TM and prevalent ESRD in 2020, 17.6% switched to MA in 2021. Compared with individuals who stayed in traditional Medicare, those who switched to MA had modestly more chronic conditions (6.3 vs 6.1; difference, 0.12 conditions [95% CI, 0.10-0.16]) and similar nondrug spending in 2020 (difference, $509 [95% CI, −$58 to $1075]) but were more likely to be Black (difference, 19.5 percentage points [95% CI, 19.1-19.9]) and have dual Medicare-Medicaid eligibility (difference, 20.8 percentage points [95% CI, 20.4-21.2]). Among beneficiaries who were newly eligible for Medicare ESRD benefits in 2021, 35.2% enrolled in MA.

Conclusions and Relevance

Results suggest that increases in MA enrollment among Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD were substantial the first year after the 21st Century Cures Act, particularly among Black, Hispanic, and dual-eligible individuals. Policy makers and MA plans may need to assess network adequacy, disenrollment, and equity of care for beneficiaries who enrolled in MA.

This cross-sectional study uses data from Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD (kidney transplant recipients and those undergoing dialysis) to examine changes in Medicare Advantage enrollment after enactment of the 21st Century Cures Act overall, by race and ethnicity, and by dual-eligible status.

Introduction

Kidney failure affects more than 800 000 individuals in the US and disproportionately affects racial and ethnic minority individuals and people with low income.1,2 Kidney failure is a highly morbid condition that requires treatment, usually in the form of transplant or thrice-weekly dialysis sessions, for survival. Most persons with kidney failure in the US qualify for Medicare coverage through its End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Program. The approximately 1% of Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD account for 7% of traditional Medicare (TM) spending.3 Under a provision of the 21st Century Cures Act, Medicare opened up enrollment of patients with ESRD, effective January 1, 2021, in its most widely adopted alternative payment model: private Medicare Advantage (MA) plans.4 Before 2021, persons receiving a diagnosis of ESRD were permitted to enroll only in TM except under limited exceptions (eg, developing incident kidney failure while already enrolled in an MA plan). For many individuals with ESRD who have private insurance when they qualify for Medicare, the Medicare Secondary Payer Act requires that the private insurer cover the first 30 months of care; however, the act does not apply to MA coverage. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) projected that 83 000 persons with ESRD (14% of Medicare’s ESRD population) would join an MA plan within 2 years.5 However, to date there have been few estimates of the initial association between this policy and enrollment choices by individuals with ESRD.

Some patient advocates have suggested that beneficiaries with ESRD could benefit from MA enrollment. For example, these beneficiaries often have multiple comorbidities and higher costs than other Medicare beneficiaries.6,7 Because some MA plans have lower premiums than TM and include out-of-pocket spending limits, MA enrollment could be cost saving to beneficiaries with ESRD.6,8 In general, MA plans disproportionately enroll beneficiaries who are Black, are Hispanic, or have low income, in part because these plans often provide supplemental benefits beyond what is available through TM.9,10,11 Whether this pattern would be consistent among beneficiaries with ESRD, a particularly high-need subpopulation, once they were able to enroll in MA is unknown.

Disenrollment from an insurer can indicate beneficiary preferences or unmet beneficiary needs.12 Therefore, understanding the number of beneficiaries with ESRD who switched from TM to MA, as well as whether certain beneficiary groups disproportionately did so, is critical for policy makers and MA plans to monitor the quality and equity of care, ensure network adequacy, and optimize benefits.

We examined national changes in MA enrollment among Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD in the first year of the Cures Act, stratified by beneficiary race, ethnicity, and dual-eligible status. We then compared characteristics of beneficiaries who stayed in TM with those who switched from TM to MA between 2020 and 2021 and assessed contract characteristics of those newly enrolled in MA. Last, we assessed rates of MA enrollment for and characteristics of beneficiaries who became newly eligible for ESRD benefits in 2021.

Methods

Study Design, Study Population, and Data Sources

We conducted a cross-sectional time-trend study of the changes in enrollment in MA among Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD between 2019 and 2021. The study population included all Medicare beneficiaries with prevalent or incident ESRD in our study period and excluded beneficiaries who died before January 2021 (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Beneficiaries were entitled to Medicare benefits because of ESRD and included individuals requiring long-term dialysis and those who received a transplant. In comparing the characteristics of beneficiaries who stayed in TM with those who switched from TM to MA in 2021, we limited our analysis to beneficiaries who had only TM in 2020. We separately conducted an analysis examining rates of MA enrollment and the characteristics of beneficiaries who became newly eligible for Medicare ESRD benefits (hereafter referred to as beneficiaries with incident ESRD) in 2021.

We used data from the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File, which includes monthly enrollment for each part of the Medicare program and sociodemographic information for all Medicare beneficiaries. To assess beneficiaries’ clinical complexity and previous use patterns, we used data from the file’s Chronic Conditions and Cost and Utilization segments, respectively. The Chronic Conditions segment includes flags for 30 chronic conditions, and the Cost and Utilization segment includes a summary of use and payments for various services in the last year for Medicare beneficiaries with Parts A and B coverage. All costs reflect payments made in the previous year by Medicare, the beneficiary, and other primary payers. More information about the chronic conditions and use can be found in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Among beneficiaries enrolled in MA, the Master Beneficiary Summary File includes a contract identifier, which we used to link to the CMS MA contract files and Ideon network data to examine the characteristics of MA contracts with MA ESRD enrollees in 2021. Ideon is a health technology company that aggregates MA network information at the contract level and has been used in previous research of MA network breadth.13,14 We included county-level characteristics (MA penetration rate, number of dialysis facilities, and Medicare beneficiary composition) by using CMS Dialysis Facility Compare and ESRD Quality Incentive Program data. More information about measures and data sources is available in eTable 1 in the Supplement. Brown University’s institutional review board and the CMS Privacy Board approved the study protocol and waived the need for informed consent owing to use of deidentified data. The study follows the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies.

Measures

Our primary outcome was monthly enrollment in MA vs TM. For our time-trend analysis, we examined changes between 2019 and 2021. We then assessed whether and how enrollment type changed between 2020 and 2021 among prevalent and incident beneficiaries with ESRD. Among beneficiaries with prevalent ESRD, those who were enrolled only in TM in 2020 and 2021 were considered to have stayed in TM, whereas beneficiaries enrolled in TM in 2020 and in MA for at least 1 month in 2021 were considered to have switched to MA. We also calculated rates of changing between enrollment type (ie, beneficiaries who switched to MA). Among beneficiaries with incident ESRD in 2021 (ie, beneficiaries with no prior diagnosis of ESRD before 2021), we assessed whether they enrolled only in TM, only in MA, or in both TM and MA.

We compared differences in sociodemographic characteristics, presence of clinical conditions, and costs and use between beneficiaries who stayed in TM vs those who switched to MA. Sociodemographic characteristics included age, race, ethnicity, dual Medicare-Medicaid eligible status, and reason for current Medicare entitlement. The Master Beneficiary Summary File uses an algorithm developed by the Research Triangle Institute to determine race and ethnicity and classifies beneficiaries as Hispanic or Asian or Pacific Islander according to data from the Social Security Administration or whether they have a first or last name that Research Triangle Institute determined was likely Hispanic or Asian.

Because the Master Beneficiary Summary File Chronic Conditions and Cost and Utilization segments are available only for periods of enrollment in TM, we limited these comparisons to 2020, when the beneficiaries in our comparison were all still in TM. We assessed the presence of 23 clinical conditions, first examining whether a beneficiary had ever received a diagnosis while covered by TM and second examining whether care was sought for that condition in 2020. We selected clinical conditions to align with Medicare’s Hierarchical Condition Categories (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Historical cost-related measures, which reflect payments made for a beneficiary by any payer in 2020, included total costs, as well as spending for prescription drugs (Medicare Parts B and D), outpatient visits (ambulatory surgical centers, dialysis, evaluation and management, hospital outpatient, other carrier, and physician office), inpatient hospitalizations, and postacute care (skilled nursing facility and home health). Measures of use in 2020 included hospital stays and skilled nursing facility stays per 100 beneficiaries. We calculated annual costs and use estimates, which were standardized and weighted according to number of months enrolled in TM to account for beneficiaries with partial TM enrollment.

Among beneficiaries who enrolled in MA in 2021 (both those who switched to MA and beneficiaries with incident ESRD who enrolled in an MA plan in 2021), we describe contract-level characteristics, including plan type, single state vs multistate, parent organization, enrollment in a contract with beneficiaries in a special needs plan, MA star rating, for-profit status, contract age, integrated system, MA penetration rate, county-level dialysis facility supply, contract-level dialysis facility network breadth, and county-level sociodemographic characteristics (eg, proportion of Black beneficiaries).

Statistical Analysis

We report absolute and relative changes in MA enrollment between December 2020 and December 2021 both overall and stratified by beneficiary race and ethnicity and dual Medicare-Medicaid coverage. We compared beneficiary- and county-level characteristics of beneficiaries who stayed in TM vs those who switched to MA and beneficiaries with incident TM vs incident MA, using Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. Statistical significance was set at a 2-sided P < .05. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 17.0 (Stata Corp).

Sensitivity Analyses

To assess the robustness of our analyses, we conducted multiple sensitivity analyses. First, using linear probability models we examined changes in composition of Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD between 2020 and 2021 to assess whether changes in MA enrollment may be associated with changes in the underlying population of Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD. Second, we estimated annual changes (eg, December 2020 to December 2021) and within-year changes (eg, January 2020 to December 2020) in MA enrollment overall and by race, ethnicity, and dual eligibility. Third, we assessed overall trends in MA enrollment among Medicare beneficiaries who did not have ESRD. Fourth, under very specific cases, the most common of which is dual eligibility, CMS allows for midyear switches from TM to MA. Therefore, we recategorized beneficiaries who switched mid-2020 from TM to MA as those who switched to MA. We present Part B and D enrollment among beneficiaries with ESRD.

Results

Study Sample and Trends in MA Enrollment Among Medicare Beneficiaries With ESRD

Our study sample included 575 797 beneficiaries with ESRD in 2020 or 2021. The mean (SD) age was 64.7 (14.2) years, 57.8% were male, 42.2% were female, 34.0% were Black, and 7.7% were Hispanic or Latino. The proportion of all Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD who were enrolled in MA increased from 22.5% to 24.8% between January 2019 and December 2020 (a relative change of 10.2%) and from 24.8% to 37.4% between December 2020 and December 2021 (a relative change of 50.8%) (Figure, A; eTables 2 and 3 in the Supplement). Between January 2019 and December 2021, the proportion of all Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD who were enrolled in MA increased by 66.2%. The lowest rates of MA enrollment in December 2021 were among American Indian or Alaska Native beneficiaries (18.9%) and the highest rates were among Black (42.9%) and Hispanic (41.8%) beneficiaries (Figure, B). Between December 2020 and December 2021, MA enrollment increased for all groups: American Indian or Alaska Native (10.7 percentage points; relative change = 130.8%), Asian or Pacific Islander (8.8 percentage points; relative change = 33.4%), Black (18.1 percentage points; relative change = 72.8%), Hispanic (13.0 percentage points; relative change = 44.8%), and non-Hispanic White (8.4 percentage points; relative change = 35.5%) (eTables 2 and 3 in the Supplement). Before 2021, beneficiaries with dual Medicare-Medicaid coverage had lower rates of MA enrollment; however, beginning in 2021, the proportion of dual-eligible beneficiaries with MA exceeded that of nondual-eligible beneficiaries (Figure, C). Between December 2020 and December 2021, MA enrollment increased by 17.6 percentage points (relative change = 73.6%) for dual-eligible beneficiaries with ESRD and by 8.4 percentage points for nondual-eligible beneficiaries with ESRD (relative change = 32.9%) (eTables 2 and 3 in the Supplement). Comparisons of changes in MA enrollment between 2019 and 2020 and 2020 and 2021 are presented in eTable 4 in the Supplement. Within-year growth in MA enrollment (ie, increases between January and December) increased in 2021 relative to that in prior years (eTable 5 in the Supplement). Rates of switching from TM to MA were higher than those of MA to TM (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

Figure. Proportion of Medicare Beneficiaries With End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Who Were Enrolled in Medicare Advantage in 2019-2021.

A, The numerator is the monthly number of all Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD who were enrolled in a Medicare Advantage (MA) plan. The denominator is the monthly number of all Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD. See eTable 3 in the Supplement for monthly counts of Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD between January 2019 and December 2021.

B, For estimates stratified by race and ethnicity, the numerator is the race and ethnicity–specific monthly number of all Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD who were enrolled in an MA plan and the denominator is the monthly number of all Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD from each racial and ethnic group. Race and ethnicity are from the Master Beneficiary Summary File, which uses an algorithm developed by the Research Triangle Institute to classify beneficiaries as Hispanic or Asian or Pacific Islander according to data from the Social Security Administration or whether they have a first or last name that the institute determined was likely Hispanic or Asian.

C, For estimates stratified by dual Medicare-Medicaid coverage, the numerator is the monthly number of all Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD who were enrolled in an MA plan and who had dual Medicare-Medicaid coverage for at least 1 month in a calendar year, and the denominator is the monthly number of all Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD with dual Medicare-Medicaid coverage for at least 1 month in a calendar year.

Differences Between Beneficiaries Staying in TM and Those Switching to MA

Of the 359 617 beneficiaries with prevalent ESRD and enrolled only in TM in 2020, 63 121 (17.6%) switched from TM to MA in 2021 (Table 1 and Table 2). Compared with beneficiaries who stayed in TM, those who switched to MA were younger (mean [SD], 58.6 [12.4] years vs 62.1 [14.9] years; P < .001). Higher proportions of beneficiaries who switched to MA were female (42.5% vs 40.8%; P < .001), Black (52.2% vs 32.7%; P < .001), and Hispanic or Latino (9.4% vs 8.4%; P < .001). Higher proportions of beneficiaries who switched to MA had at least 1 month of dual Medicare-Medicaid coverage (62.9% vs 42.2%; P < .001), Medicare Part D prescription drug coverage (83.9% vs 71.4%; P < .001), or Medicare Part D low-income subsidy (69.5% vs 46.0%; P < .001). Relative to beneficiaries who stayed in TM, those who switched to MA had modestly more chronic conditions (mean [SD], 6.3 [3.4] vs 6.1 [3.6]; P = .01), higher nondrug outpatient costs (median, $50 683 vs $49 776 [IQR, $41 646-$62 126 vs $38 324-$62 126]; P < .001), similar total nondrug spending (median, $63 908 vs $62 355 [IQR, $46 648-$96 870 vs $44 395-$98 198]; P = .08), and higher Part D prescription drug costs (median, $4961 vs $4564 [IQR, $1316-$12 543 vs $1264-$11 295]; P < .001).

Table 1. Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries With Prevalent ESRD, Based on Enrollment Changes in 2021.

| Characteristics | Switched to Medicare Advantage (n = 63 121)a | Stayed in traditional Medicare (n = 296 496)b |

|---|---|---|

| Beneficiary characteristics | ||

| Enrollment in 2020, median (IQR), mo | ||

| Part A (hospital) | 12 (0-12) | 12 (0-12) |

| Part B (professional fees) | 12 (0-12) | 12 (0-12) |

| Part D (prescription drugs) | 12 (0-12) | 12 (0-12) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 58.6 (12.4) | 62.1 (14.9) |

| Sex, % | ||

| Male | 57.5 | 59.2 |

| Female | 42.5 | 40.8 |

| Race or ethnicity, %c | n = 61 645 | n = 287 625 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1.1 | 1.7 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 3.2 | 4.6 |

| Black | 52.2 | 32.7 |

| Hispanic | 9.4 | 8.4 |

| White | 31.7 | 49.3 |

| Otherd | 2.4 | 3.2 |

| Reason for current Medicare enrollment, % | ||

| Disability insurance benefits | 38.6 | 25.8 |

| Old age and survivors insurance | 32.3 | 47.9 |

| ESRD | 23.3 | 22.6 |

| Both disability insurance benefits and ESRD | 5.9 | 3.6 |

| ≥1 Month dual Medicare-Medicaid coverage, % | 62.9 | 42.2 |

| ≥1 Month Part D plan coverage, % | 83.9 | 71.4 |

| ≥1 Month eligible for Part D low-income subsidy, % | 69.5 | 46.0 |

| No dialysis-related expenditures in 2020, % | 8.4 | 13.4 |

| No. of chronic conditions, mean (SD)e | ||

| Everf | 6.3 (3.4) | 6.1 (3.6) |

| 2020g | 4.1 (3.3) | 4.1 (3.3) |

| Spending in 2020, median (IQR), $h | ||

| Prescription drugs | ||

| Part B | 10 (0-135) | 13 (0-244) |

| Part D | 4961 (1316-12 543) | 4564 (1264-11 295) |

| Total nondrugi | 63 908 (46 648-96 870) | 62 355 (44 395-98 198) |

| Nondrug outpatientj | 50 683 (41 646-62 126) | 49 776 (38 324-62 126) |

| Inpatient hospitalizations | 7922 (0-31 960) | 0 (0-31 376) |

| Postacute care (skilled nursing facility, home health) | 0 (0-2104) | 0 (0-2459) |

| Use in 2020, median (IQR)h | ||

| Hospital stays | 1 (0-2) | 0 (0-2) |

| Skilled nursing facility stays per 100 beneficiaries | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-0) |

| County-level characteristics, median (IQR) | ||

| No. of dialysis facilities in 2020 | 11 (3-31) | 10 (3-30) |

| No. of DaVita-owned facilities | 4 (1-12) | 4 (1-12) |

| No. of Fresenius-owned facilities | 4 (1-9) | 3 (1-8) |

| No. of facilities not owned by DaVita or Fresenius | 2 (0-9) | 2 (0-9) |

| Proportion of female beneficiaries, % | 54.8 (53.9-55.7) | 54.6 (53.6-55.5) |

| Proportion of Black beneficiaries, % | 14.0 (5.3-26.2) | 9.6 (2.8-21.2) |

| Proportion of Hispanic beneficiaries, % | 3.5 (1.3-13.5) | 4.1 (1.4-13.5) |

| Proportion of White beneficiaries, % | 66.8 (50.3-81.1) | 71.2 (52.7-84.9) |

| Proportion of dual beneficiaries, % | 19.7 (16.2-25.2) | 18.8 (15.1-24.9) |

Abbreviation: ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

Indicates a beneficiary was enrolled only in traditional Medicare in 2020 and only in Medicare Advantage in 2021.

Indicates a beneficiary was enrolled only in traditional Medicare in 2020 and 2021.

Race and ethnicity are from the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File, which uses an algorithm developed by the Research Triangle Institute to classify beneficiaries as Hispanic or Asian or Pacific Islander according to data from the Social Security Administration or whether they have a first or last name that the institute determined was likely Hispanic or Asian.

“Other” includes categories not captured by Medicare race and ethnicity variables.

Number of chronic conditions refers to a count of diagnoses.

Chronic conditions (ever) include diagnosis of any of the following: acute myocardial infarction; arthritis; brain damage; breast cancer, prostate cancer, or other cancers; heart failure; chronic kidney disease; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; cirrhosis; cystic fibrosis; depression or bipolar disorder; diabetes; drug or alcohol dependence; HIV/AIDS; hip fracture; ischemic heart disease; leukemia; multiple sclerosis; muscular dystrophy; obesity; pressure ulcers; spinal cord injury; and vascular disease.

Chronic conditions (2020) include the previous list and add Parkinson disease and pneumonia.

Costs and use measures are annualized and weighted by number of months enrolled in Part A (hospitalizations or postacute care), Part B (prescription drugs), and Part D (prescription drugs). All costs reflect payments made in 2020 (paid by Medicare, the beneficiary, and other primary payers [which could include Veterans Affairs or TRICARE paid for services on behalf of the beneficiary]).

Total nondrug spending includes costs for inpatient hospitalizations, postacute care, and outpatient costs, and are weighted by number of months enrolled in Part B.

Outpatient costs and use include ambulatory surgical centers, dialysis (both dialysis capitation and outpatient dialysis costs), evaluation and management, hospital outpatient, other carrier, and physician office visits.

Table 2. Rates of Switching Between Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage Between 2020 and 2021 Enrollments (N = 349 270).

| Characteristics | Switched traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage, No./total (%) [95% CI]a |

|---|---|

| Overalla | 63 121 (17.6) [17.4-17.7] |

| Race and ethnicityb,c | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 685 (12.1) [11.3-13.0] |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1961 (12.8) [12.3-13.3] |

| Black | 32 186 (25.5) [25.2-25.7] |

| Hispanic | 5779 (19.3) [18.9-19.8] |

| White | 19 553 (12.1) [11.9-12.3] |

| Duald,e | 39 729/164 696 (24.1) [23.9-24.3] |

| Never duald,f | 23 392/194 921 (12.0) [11.9-12.1] |

Switching from traditional Medicare (TM) to Medicare Advantage (MA) refers to being enrolled only in TM in 2020 and for at least 1 month in MA in 2021. The numerator is the number of Medicare beneficiaries who switched from TM to MA between 2020 and 2021. The denominator is the number of Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD who were enrolled only in TM in 2020.

Race and ethnicity are from the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary file, which uses an algorithm developed by the Research Triangle Institute to classify beneficiaries as Hispanic or Asian or Pacific Islander according to data from the Social Security Administration or whether they have a first or last name that the institute determined was likely Hispanic or Asian.

The denominator of rates stratified by race or ethnicity is the number of Medicare beneficiaries of each race or ethnicity with ESRD who were enrolled in only TM in 2020.

Dual Medicare-Medicaid coverage refers to having such coverage for at least 1 month in a calendar year.

The denominator is the number of Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD who were enrolled in only TM in 2020 and had at least 1 month of dual Medicare-Medicaid coverage in a calendar year.

The denominator is the number of Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD who were enrolled in only TM in 2020 and had no dual Medicare-Medicaid coverage in a calendar year.

Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries With Incident ESRD in 2021

Of the 91 602 Medicare beneficiaries with incident ESRD in 2021, 32 208 (35.2%) were exclusively enrolled in MA, 52 415 (57.2%) were exclusively enrolled in TM in 2021, and 6979 (7.6%) had at least 1 month in both TM and MA in 2021. Compared with beneficiaries with incident ESRD who were exclusively enrolled in TM in 2021, those who were exclusively enrolled in MA in 2021 were older (mean [SD], 70.9 [10.3] vs 64.9 [14.6]) (Table 3). Relative to beneficiaries with incident ESRD who were enrolled in TM, higher proportions of those enrolled in MA were Black (31.6% vs 24.8%; P < .001), were Hispanic or Latino (5.8% vs 4.0%; P < .001), were enrolled in Medicare because of old age or survivors insurance (78.7% vs 58.2%; P < .001), and had at least 1 month of dual Medicare-Medicaid coverage (39.1% vs 34.4%; P < .001) (Table 3).

Table 3. Characteristics of People Newly Eligible for Medicare ESRD Benefits in 2021a.

| Characteristics | Medicare Advantage (n = 32 208) | Traditional Medicare (n = 52 415) |

|---|---|---|

| Beneficiary characteristics | ||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 72 (66-78) | 67 (56-75) |

| Sex, % | ||

| Male | 54.2 | 59.7 |

| Female | 45.8 | 40.3 |

| Race or ethnicity (n = 31 770 for Medicare Advantage; n = 50 670 for traditional Medicare), %b | ||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.4 | 1.2 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 3.4 | 3.0 |

| Black | 31.6 | 24.8 |

| Hispanic | 5.8 | 4.0 |

| White | 55.5 | 60.0 |

| Otherc | 3.3 | 7.0 |

| Reason for current Medicare entitlement, % | ||

| Old age and survivors insurance | 78.7 | 58.2 |

| Disability insurance benefits | 18.8 | 15.4 |

| ESRD | 0.8 | 24.9 |

| Both disability insurance benefits and ESRD | 1.7 | 1.5 |

| ≥1 Month dual Medicare-Medicaid coverage in 2021, % | 39.1 | 34.4 |

| ≥1 Month eligible for Part D coverage in 2021, % | 98.1 | 65.5 |

| ≥1 Month eligible for Part D low-income subsidy in 2021, % | 45.7 | 55.7 |

| County-level characteristics, median (IQR) | ||

| No. of dialysis facilities in 2020 | 12 (3-35) | 8 (2-24) |

| No. of DaVita-owned facilities | 5 (1-13) | 3 (0-9) |

| No. of Fresenius-owned facilities | 4 (1-9) | 3 (1-7) |

| No. of facilities not owned by DaVita or Fresenius | 3 (0-10) | 2 (0-7) |

| Proportion of female beneficiaries, % | 54.6 (53.7-55.5) | 54.5 (53.5-55.4) |

| Proportion of Black beneficiaries, % | 10.0 (3.4-20.7) | 8.1 (2.5-18.9) |

| Proportion of Hispanic beneficiaries, % | 4.1 (1.4-14.9) | 3.4 (1.3-12.3) |

| Proportion of White beneficiaries, % | 71.1 (52.3-84.7) | 75.2 (56.6-88.2) |

| Proportion of dual beneficiaries, % | 19.5 (15.9-25.0) | 18.4 (14.6-24.7) |

Abbreviation: ESRD, end-stage renal disease.

Sample limited to Medicare beneficiaries who became newly eligible for ESRD benefits in 2021. Table does not include Medicare beneficiaries who became newly eligible for ESRD benefits in 2021 who switched coverage and had at least 1 month in both traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage (n = 6979, or 7.6% of the sample).

Race and ethnicity are from the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary file, which uses an algorithm developed by the Research Triangle Institute to classify beneficiaries as Hispanic or Asian or Pacific Islander according to data from the Social Security Administration or whether they have a first or last name that the institute determined was likely Hispanic or Asian.

Other includes categories not captured by Medicare race and ethnicity variables.

Contract Characteristics

Common contract characteristics for beneficiaries who switched to MA and those with incident ESRD who enrolled in MA in 2021 included those that were multistate (57.4% and 60.7%, respectively), for profit (91.9% and 79.2%, respectively), or older than 10 years (59.5% and 75.2%, respectively) (Table 4). The most common parent organizations for contracts of beneficiaries who switched to MA and those with incident ESRD who enrolled in MA were UnitedHealth Group Inc (31.3% and 28.1%, respectively) and Humana Inc (24.8% and 21.2%, respectively).

Table 4. Contract Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries With ESRD and Enrolled in Medicare Advantage in 2021.

| Characteristics | Prevalent ESRD, switched to Medicare Advantage (n = 63 121) | Incident ESRD, enrolled in Medicare Advantage (n = 32 208) |

|---|---|---|

| County-level MA penetration rate, mean (SD), %a | 46.4 (11.5) | 48.3 (11.3) |

| Plan type | ||

| HMO or HMO POS | 63.6 | 62.1 |

| Local PPO | 28.8 | 29.6 |

| Regional PPO | 4.3 | 5.5 |

| Other (MSA, Medicare-Medicaid plan, national PACE, PFFS) | 3.3 | 2.6 |

| Multistate | 57.4 | 60.7 |

| Parent organization | ||

| UnitedHealth Group, Inc | 31.3 | 28.1 |

| Humana Inc | 24.8 | 21.2 |

| Centene Corporation | 12.2 | 5.7 |

| Anthem Inc | 9.5 | 6.5 |

| CVS Health Corporation | 7.2 | 8.9 |

| Cigna | 2.5 | 2.9 |

| Other | 12.5 | 26.7 |

| Enrollment in MA contracts with >0% special needs plan | 80.5 | 67.9 |

| MA star rating, mean (SD)b | 3.8 (0.5) | 3.9 (0.5) |

| For profit | 91.9 | 79.2 |

| Contract age, yc | ||

| ≤5 | 25.7 | 13.7 |

| 6-10 | 14.8 | 11.1 |

| >10 | 59.5 | 75.2 |

| Integrated system, %d | 4.6 | 10.7 |

| Dialysis facility network breadth, mean (SD) in 2020e | 63.8 (23.6) | 68.0 (21.3) |

| Narrow dialysis facility networks in 2020f | 7.8 | 3.8 |

Abbreviations: ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HMO, health maintenance organization; MA, Medicare Advantage; MSA, medical savings account; PACE, Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly; PFFS, private fee for service; POS, point of service; PPO, preferred provider organization.

Medicare Advantage penetration rate is defined as the county-level proportion of all Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in MA.

Medicare Advantage star ratings range between 1 and 5 stars (1 star is the lowest rating and 5 stars is the highest). Ratings are calculated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services on the basis of 30 to 35 measures of satisfaction and quality outcomes.

Contract age refers to the number of years a plan or contract has been operating, which is calculated as the difference between the contract effective date and 2021.

Integrated system refers to MA contracts that were associated with a health system or hospital.

Dialysis facility network breadth is defined as the proportion of dialysis facilities located in each MA contract’s service area that were included in that contract’s network.

Narrow networks are defined as those that included less than or equal to 25% of available dialysis facilities in a given contract’s service area.

Sensitivity Analyses

The composition of Medicare beneficiaries with prevalent or incident ESRD changed slightly between 2020 and 2021 (eTable 6 in the Supplement). We present the distribution of enrollment changes among Medicare beneficiaries with prevalent ESRD between 2020 and 2021, including those with mixed TM and MA enrollment in both years, those who stayed enrolled in MA in both years, and those who switched to MA (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Trends in MA enrollment among Medicare beneficiaries without ESRD between 2019 and 2021 were more modest compared with those for individuals with ESRD (eTable 7 and eFigure 3 in the Supplement). Detailed use and cost measures by service type and payer are presented in eTable 8 in the Supplement. We present characteristics of beneficiaries who switched in mid-2020 from TM to MA (eTable 9 in the Supplement) and enrollment rates in Medicare Parts B and D (eTable 10 in the Supplement). Data were analyzed between June and October 2022.

Discussion

In this study of all US Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD, we found that the proportion of those enrolled in MA increased substantially in 2021. To our knowledge, these are the first estimates of changes in MA enrollment by Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD after the implementation of the Cures Act, both overall and stratified by key sociodemographic characteristics. Nationwide, there was a 51% increase in MA enrollment among all beneficiaries with ESRD, exceeding CMS projections of approximately 30% in 2021.5 Our study builds on these estimates by showing that there were disproportionately higher enrollment increases in MA among ESRD beneficiaries who were Black, were Hispanic, and had low income. Among beneficiaries with prevalent ESRD and enrolled only in TM in 2020, approximately 17.6% switched from TM to MA in 2021; compared with those who remained in TM, those who switched to MA were substantially more likely to be Black or Hispanic or Latino and dually eligible for Medicaid, but differences in the number of chronic conditions and health care spending in the year before switching were modest. Among beneficiaries with incident kidney failure in 2021, 35.5% enrolled in MA, an increase of nearly 10 percentage points since 2020. Contract characteristics (eg, plan type, parent organization, star ratings) for MA enrollees with ESRD in our study were comparable to those for all MA enrollees.15,16

Before the Cures Act, MA plans enrolled approximately 24 million Medicare beneficiaries (42% of all Medicare beneficiaries).15 Our estimates build on recent work suggesting high rates of growth in MA enrollment among racial and ethnic minority and dual-eligible populations.8,17 Although there is no evidence to suggest differences in 1-year mortality rates among beneficiaries with ESRD in TM vs MA,18 fundamental questions about the value of managed care for persons with serious health conditions such as ESRD remain unanswered. Medicare Advantage plans receive capitated payments to bear financial risk for covered services and are held accountable for quality of care. These incentives may yield innovative approaches to improve the value of care, although they may also limit access to care. For example, MA plans may implement tailored interventions for these populations and, unlike TM, may cover benefits to address unmet social needs (eg, food insecurity).19 However, MA plans also face incentives to restrict use of high-cost services and have higher disenrollment rates among patients with intensive health care needs.12,20 After the first year of the Cures Act, it will be critical for policy makers and MA plans to monitor whether provider networks (eg, dialysis facilities, nephrology services) were equipped to facilitate access to care for substantially more MA enrollees with ESRD.14 Future work may also assess changes in use after switches from TM to MA, voluntary disenrollment from MA, experiences of care among beneficiaries in MA plans, and whether some plan types perform better for beneficiaries with ESRD.10,12,20,21

Our findings also have important implications for equity of care among beneficiaries with ESRD, a condition that disproportionately affects individuals who are Black, are Hispanic, or have low income.1,2,22,23,24,25 Our study findings are consistent with studies indicating that the largest increases between 2009 and 2018 in MA enrollment for beneficiaries with ESRD were among those who were Black, Hispanic, dual eligible, or residing in disadvantaged neighborhoods.17 Because of structural racism and other inequities, people who are Black, are Hispanic, and have low income bear the burden of inequitable access to care, including for kidney disease. For example, Black people have a higher incidence of ESRD, more delays in referral to nephrology care, and poorer-quality dialysis than non-Hispanic White people.25 Similarly, compared with non-Hispanic White people, Hispanic or Latino individuals have higher prevalence rates of ESRD.26 There are well-documented racial and ethnic inequities in health outcomes among MA enrollees.17,27,28,29,30,31 For example, compared with TM, MA is associated with better outcomes and ambulatory care access for beneficiaries from racial and ethnic minority groups; however, these racial and ethnic minority beneficiaries reported worse outcomes for most measures compared with their White counterparts, irrespective of whether they were in MA or TM.32 Because the number and offerings of various MA plans have diversified,17 it will be critical for MA plans to measure and assess racial and ethnic inequities in access to care, use, and health outcomes among newly enrolled beneficiaries with ESRD.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations: first, data were unavailable for historical cost and use for individuals with MA in 2020, limiting our ability to assess the characteristics of those who stayed in MA or who enrolled in both TM and MA in 2020. We therefore focused our comparison on beneficiaries who stayed in TM and those who switched to MA who enrolled in TM in 2020. Second, our race and ethnicity variable used the Research Triangle Institute algorithm, and it is possible that some beneficiaries were misclassified. Third, we were unable to assess differences between beneficiaries with ESRD who were undergoing long-term dialysis or required a kidney transplant. Fourth, in our data we were unable to account for some of the dynamics of Medicare eligibility (eg, individuals with a diagnosis of ESRD but not yet Medicare eligible in our study period). In addition, the ESRD population is dynamic and only those who were alive in both 2020 and 2021 were included in the main analyses in the study. It is possible that some patients who would have switched to MA in 2021 died before they could switch and that mortality rates among beneficiaries with ESRD could be differential by health insurance type (TM vs MA). However, a recent study comparing risk-adjusted 1-year mortality rates did not identify significant differences.18 Fifth, our study period overlapped with the COVID-19 pandemic, and it is possible that the pandemic influenced these outcomes. Some previous work indicated that the pandemic affected mortality rates and treatment initiation for patients with kidney failure, with disproportionate effects on Black patients.33,34 Sixth, because we lacked data on CMS payments or MA spending, we were unable to estimate the financial implications of the entry of patients with ESRD into MA.

Conclusions

In the first year after implementation of the 21st Century Cures Act, increases in MA enrollment among Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD were substantial—particularly among Black, Hispanic, and dual-eligible individuals—and exceeded initial CMS projections. Continued monitoring of network adequacy, use, disenrollment, and equity of care will be critical for policy makers and MA plans to ensure adequate access to care for beneficiaries with ESRD.

eTable 1. Data Sources and Measure Definitions

eFigure 1. Study Flow Chart: Medicare Beneficiaries With Prevalent Kidney Failure in 2020

eTable 2. Relative Changes in Medicare Advantage Enrollment, Overall and by Race and Ethnicity and Dual Medicare-Medicaid Enrollment Between December 2020 and December 2021

eTable 3. Medicare Beneficiaries With ESRD Overall and by Race, Ethnicity, and Dual Eligibility, 2019-2021

eTable 4. Changes in Composition of Medicare Beneficiaries With End-Stage Renal Disease Between 2020 and 2021

eFigure 2. Changes in Medicare Advantage Enrollment Among Medicare Beneficiaries With End-Stage Renal Disease, 2020-2021

eFigure 3. Proportion of Medicare Beneficiaries Without End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Enrolled in Medicare Advantage, 2019-2021

eTable 5. Relative Changes in Medicare Advantage Enrollment Among Medicare Beneficiaries With No Diagnosis of End-Stage Renal Disease

eTable 6. Annual Changes in Medicare Advantage Enrollment, 2019-2021

eTable 7. Within-Year Changes in Medicare Advantage Enrollment, 2019-2021

eTable 8. Use and Costs of Medicare Beneficiaries With Prevalent End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Based on Changes in Enrollment, 2020

eTable 9. Alternative Specification of Traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage Switching

eTable 10. Enrollment in Medicare Parts B and D

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Patzer RE, McClellan WM. Influence of race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status on kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8(9):533-541. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nguyen KH, Thorsness R, Swaminathan S, et al. Despite national declines in kidney failure incidence, disparities widened between low- and high-poverty US counties. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(12):1900-1908. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Renal Data System. 2020 USRDS annual data report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2021. Accessed February 16, 2023. https://adr.usrds.org/2020

- 4.21st Century Cures Act, HR 34, 114th Cong (2015).

- 5.Federal Register. Medicare and Medicaid programs: contract year 2021 and 2022 policy and technical changes to the Medicare Advantage program, Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit program, Medicaid program, Medicare Cost Plan program, and programs of all-inclusive care for the elderly. Proposed rule. February 18, 2020. Accessed February 16, 2023. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/02/18/2020-02085/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-contract-year-2021-and-2022-policy-and-technical-changes-to-the

- 6.Morgan PC, Kirchhoff SM. Medicare Advantage (MA) coverage of end stage renal disease (ESRD) and network requirement changes. Congressional Research Service. January 11, 2021. Accessed January 27, 2023. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46655

- 7.Powers BW, Yan J, Zhu J, et al. . The beneficial effects of Medicare Advantage special needs plans for patients with end-stage renal disease. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(9)1486-1494. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyers DJ, Trivedi AN. Trends in the source of new enrollees to Medicare Advantage from 2012 to 2019. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(8):e222585. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.2585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuman P, Jacobson GA. Medicare advantage checkup. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2163-2172. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr1804089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rivera-Hernandez M, Blackwood KL, Moody KA, Trivedi AN. Plan switching and stickiness in Medicare Advantage: a qualitative interview with Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. Med Care Res Rev. 2021;78(6):693-702. doi: 10.1177/1077558720944284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinick R, Haviland A, Hambarsoomian K, Elliott MN. Does the racial/ethnic composition of Medicare Advantage plans reflect their areas of operation? Health Serv Res. 2014;49(2):526-545. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyers DJ, Belanger E, Joyce N, McHugh J, Rahman M, Mor V. Analysis of drivers of disenrollment and plan switching among Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(4):524-532. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu JM, Zhang Y, Polsky D. Networks in ACA marketplaces are narrower for mental health care than for primary care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(9):1624-1631. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyers DJ, Rahman M, Trivedi AN. Narrow primary care networks in Medicare Advantage. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(2):488-491. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06534-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaiser Family Foundation . Medicare Advantage in 2022: enrollment update and key trends. August 25, 2022. Accessed January 27, 2023. https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-in-2022-enrollment-update-and-key-trends/

- 16.Medicare Payment Advisory Committee . March 2022. report to the Congress: Medicare payment policy. MedPAC. March 15, 2022. Accessed January 27, 2023. https://www.medpac.gov/document/march-2022-report-to-the-congress-medicare-payment-policy/

- 17.Meyers DJ, Mor V, Rahman M, Trivedi AN. Growth in Medicare Advantage greatest among Black and Hispanic enrollees. Health Aff (Millwood). 2021;40(6):945-950. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim D, Lee Y, Swaminathan S, et al. Comparison of mortality between Medicare Advantage and traditional Medicare beneficiaries with kidney failure. Am J Manag Care. 2022;28(4):180-186. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2022.88861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyers DJ, Durfey SNM, Gadbois EA, Thomas KS. Early adoption of new supplemental benefits by Medicare Advantage plans. JAMA. 2019;321(22):2238-2240. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.4709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DuGoff E, Chao S. What’s driving high disenrollment in Medicare Advantage? Inquiry. 2019;56:46958019841506. doi: 10.1177/0046958019841506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Q, Trivedi AN, Galarraga O, Chernew ME, Weiner DE, Mor V. Medicare Advantage ratings and voluntary disenrollment among patients with end-stage renal disease. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(1):70-77. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crews DC, Novick TK. Social determinants of CKD hotspots. Semin Nephrol. 2019;39(3):256-262. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2019.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crews DC, Novick TK. Achieving equity in dialysis care and outcomes: the role of policies. Semin Dial. 2020;33(1):43-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nicholas SB, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Norris KC. Socioeconomic disparities in chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015;22(1):6-15. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2014.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohottige D, Diamantidis CJ, Norris KC, Boulware LE. Racism and kidney health: turning equity into a reality. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77(6):951-962. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Desai N, Lora CM, Lash JP, Ricardo AC. CKD and ESRD in US Hispanics. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73(1):102-111. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.02.354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyers DJ, Rahman M, Mor V, Wilson IB, Trivedi AN. Association of Medicare Advantage star ratings with racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in quality of care. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2:e210793. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.0793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park S, Langellier BA, Meyers DJ. Association of health insurance literacy with enrollment in traditional Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and plan characteristics within Medicare Advantage. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(2):e2146792. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.46792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rivera-Hernandez M, Leyva B, Keohane LM, Trivedi AN. Quality of care for white and Hispanic Medicare Advantage enrollees in the United States and Puerto Rico. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(6):787-794. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weech-Maldonado R, Elliott MN, Adams JL, et al. Do racial/ethnic disparities in quality and patient experience within Medicare plans generalize across measures and racial/ethnic groups? Health Serv Res. 2015;50(6):1829-1849. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trivedi AN, Zaslavsky AM, Schneider EC, Ayanian JZ. Relationship between quality of care and racial disparities in Medicare health plans. JAMA. 2006;296(16):1998-2004. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.16.1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnston KJ, Hammond G, Meyers DJ, Joynt Maddox KE. Association of race and ethnicity and Medicare program type with ambulatory care access and quality measures. JAMA. 2021;326(7):628-636. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.10413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim D, Lee Y, Thorsness R, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in excess deaths among persons with kidney failure during the COVID-19 pandemic, March-July 2020. Am J Kidney Dis. 2021;77(5):827-829. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2021.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nguyen KH, Thorsness R, Hayes S, et al. Evaluation of racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in initiation of kidney failure treatment during the first 4 months of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2127369. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.27369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Data Sources and Measure Definitions

eFigure 1. Study Flow Chart: Medicare Beneficiaries With Prevalent Kidney Failure in 2020

eTable 2. Relative Changes in Medicare Advantage Enrollment, Overall and by Race and Ethnicity and Dual Medicare-Medicaid Enrollment Between December 2020 and December 2021

eTable 3. Medicare Beneficiaries With ESRD Overall and by Race, Ethnicity, and Dual Eligibility, 2019-2021

eTable 4. Changes in Composition of Medicare Beneficiaries With End-Stage Renal Disease Between 2020 and 2021

eFigure 2. Changes in Medicare Advantage Enrollment Among Medicare Beneficiaries With End-Stage Renal Disease, 2020-2021

eFigure 3. Proportion of Medicare Beneficiaries Without End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Enrolled in Medicare Advantage, 2019-2021

eTable 5. Relative Changes in Medicare Advantage Enrollment Among Medicare Beneficiaries With No Diagnosis of End-Stage Renal Disease

eTable 6. Annual Changes in Medicare Advantage Enrollment, 2019-2021

eTable 7. Within-Year Changes in Medicare Advantage Enrollment, 2019-2021

eTable 8. Use and Costs of Medicare Beneficiaries With Prevalent End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Based on Changes in Enrollment, 2020

eTable 9. Alternative Specification of Traditional Medicare to Medicare Advantage Switching

eTable 10. Enrollment in Medicare Parts B and D

Data Sharing Statement