Abstract

Background:

Single Institutional Review Boards (sIRB) are not achieving the benefits envisioned by the National Institutes of Health. The recently published Health Level Seven (HL7®) Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR®) data exchange standard seeks to improve sIRB operational efficiency.

Methods and Results:

We conducted a study to determine whether the use of this standard would be economically attractive for sIRB workflows collectively and for Reviewing and Relying institutions. We examined four sIRB-associated workflows at a single institution: (1) Initial Study Protocol Application, (2) Site Addition for an Approved sIRB study, (3) Continuing Review, and (4) Medical and Non-Medical Event Reporting. Task-level information identified personnel roles and their associated hour requirements for completion. Tasks that would be eliminated by the data exchange standard were identified. Personnel costs were estimated using annual salaries by role. No tasks would be eliminated in the Initial Study Protocol Application or Medical and Non-Medical Event Reporting workflows through use of the proposed data exchange standard. Site Addition workflow hours would be reduced by 2.50 hours per site (from 15.50 to 13.00 hours) and Continuing Review hours would be reduced by 9.00 hours per site per study year (from 36.50 to 27.50 hours). Associated costs savings were $251 for the Site Addition workflow (from $1609 to $1358) and $1033 for the Continuing Review workflow (from $4110 to $3076).

Conclusion:

Use of the proposed HL7 FHIR® data exchange standard would be economically attractive for sIRB workflows collectively and for each entity participating in the new workflows.

Keywords: single institutional review board, workflow, cost analysis, data exchange, HL7 FHIR

INTRODUCTION

Clinical research regulatory approval processes are inefficient and often delay study start-up. Historically, each site in a multisite clinical study submitted the study’s full documentation to its local Institutional Review Board (IRB) and each local IRB undertook a full and independent review of the study (1). The resulting redundant effort and review inconsistencies caused by local IRBs contributed to delays in multisite clinical study initiation (2–4). Researchers found that the average time to site ethics approval was not influenced by the study’s therapeutic area, use of a contract research organization, project manager experience, number of ancillary services, or whether the study was an interventional vs. observational study (5). However, studies have shown that the use of central IRBs (vs. local) can reduce the time for study site IRB or ethics approval (6–8).

The US Government amended the National Institutes of Health (NIH) policy and the Common Rule to require that a single IRB (sIRB) review all NIH-funded, nonexempt, multisite human subjects research beginning January 25th, 2018 (9). These sIRB-associated regulatory changes sought to improve human subject protection by altering study site- and IRB-related workflows and institutional relationships. Although many expected that sIRBs would improve IRB efficiencies, this has not been the case (10, 11). A recent study reported that the sIRB-associated requirement to work with multiple outside or local IRBs and information systems was seen as a barrier to sIRB adoption (1). While some institutions have attempted to deal with these interoperability issues by developing shared IRB applications and workflows, this approach is not feasible on a large scale (12).

Traditionally, the health care industry has addressed interoperability issues by standardizing communications between existing information systems (13). Our team developed the Health Level 7 (HL7®) Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR®) national data exchange standard and software to support sIRB-related data exchange and achieve improvements in operational efficiency. The standard’s Implementation Guide (IG) (published July 2022) describes requirements for electronically exchanging structured information between eIRB systems (system to system) using the international FHIR® standard specification (See Appendix) (14). However, it is not known whether this standard will lead to greater efficiencies for sIRBs in multisite clinical studies.

We conducted a study to describe sIRB-associated workflows, their personnel requirements, and costs before and after implementing the proposed sIRB data exchange standard. We sought to determine whether use of this standard would be economically attractive for sIRB workflows collectively and for each entity participating in the new sIRB workflows.

METHODS

sIRB Data Exchange Standard

The HL7 FHIR® sIRB data exchange standard seeks to standardize data exchange between sIRBs and relying sites (14). The sIRB (also known as the reviewing IRB) “provides the ethical review for all sites participating in a particular multisite study for the duration of the study (15).” The relying institution is, “the participating institution that will rely on (i.e., cede IRB review) to an IRB from another institution to conduct the ethics review of a study that will be conducted at the relying institution (15).” The legal vehicle for this arrangement is a ‘reliance’ or ‘collaborative’ agreement between the sIRB and the relying site (14). The proposed sIRB data exchange standard seeks to improve multisite clinical study efficiency by standardizing information flows between sIRBs and relying sites.

Model design and major components

We developed an economic model to compare differences in the efficiency of multisite clinical study sIRBs operating with and without the HL7 FHIR® sIRB data exchange standard. Four sIRB-associated workflows were included in this analysis: (1) Initial Study Protocol Application, (2) Site Addition for an Approved sIRB Study, (3) Continuing Review, and (4) Medical and Non-Medical Event Reporting. The Duke Health System Institutional Review Board determined that this study was elegible for an exemption.

Study setting and workflow

We examined sIRB-associated workflows at Duke University Medical Center (DUMC). The Duke IRB uses iRIS from iMedRIS software (now part of Cayuse). While each sIRB will complete these workflows, the specific tasks and their sequencing within each workflow may differ among reviewing and relying institutions (16).

Site Data Collection

The Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board Director and Manager of Single IRB Operations were interviewed by study team members with expertise in clinical informatics, (VW), HL7-FHIR® (AW), and IRB operations (AW, KD) to determine how Duke operationalized the four sIRB workflows. This work included a step-by-step sIRB process review that identified the roles involved, tasks associated with those roles, and how documents/data were exchanged between functional groups. Information was also obtained regarding task-specific estimates of personnel hours by role. Study team members used this information to develop workflow descriptions and diagrams. Duke IRB representatives then reviewed this information and provided feedback to ensure accuracy of the workflow documentation. Task sheets were developed for each workflow identifying component tasks, personnel associated roles and their personnel hour requirements for completion of tasks.

In the second data collection phase, two team members from the first phase (AW and KD) met with a Duke IRB member (LM) and a health economics researcher (EE) to review the initial workflow descriptions and task sheets and determine which tasks would be eliminated with the use of the proposed HL7 FHIR® sIRB data exchange standard. All discussants agreed with the final recommendations. This information was then used to create a second set of task lists with revised estimates for personnel hour requirements for completion. Tasks that would be modified but not eliminated by the proposed data exchange standard were assumed to have no change in personnel hours required for completion.

sIRB Workflow Roles and Functional Groups

The workflow descriptions identified five roles. These were: (1) sIRB Administrator, (2) sIRB Staff, (3) Lead Institution Principal Investigator (PI) Staff, (4) Relying Site Principal Investigator (PI) Staff, and (5) Relying Site Administration Staff. The Lead Institution Principal Investigator has legal responsibility for the overall study’s conduct. The Relying Site PIs have legal responsibility for study-related activities at their sites. Both of these roles can delegate particular activities to staff members. In our economic model, the Lead Institution PI Staff role performs duties delegated by the Lead Institutions PI. Similarly, the Relying Site PI Staff and Relying Site Administration Staff roles perform duties delegated by the Relying Site PI. The sIRB Administrator and sIRB Staff titles denote separate roles within the sIRB institution that have different responsibilities. Similarly, the Relying Site PI Staff and Relying Site Administration Staff also denote separate roles within the Relying Site. Different roles were required because these roles were associated with different annual salaries. Although each workflow role may have one or more different job titles at other institutions, we used these role titles in our economic model to best reflect each role’s duties. Lastly, we created three functional groups for reporting purposes. The Single IRB group includes the sIRB Administrator and sIRB Staff roles; the Lead Institution Principal Investigator group includes the Lead Institution PI Staff role; and the Relying Site Principal Investigator group includes the Relying Site PI Staff and Relying Site Administration Staff roles.

Measurements

The primary study endpoints were the reduction in total costs for each of the four workflows after the HL7 FHIR® sIRB data exchange standard implementation. Secondary study endpoints included: (1) total workflow costs before and after the HL7 FHIR® sIRB standard implementation, (2) workflow costs by role and functional group (sIRB, Lead Institution Principal Investigator, and Relying Site Principal Investigator) before and after the HL7 FHIR® data exchange standard implementation, and the differences in workflow costs by role and functional group.

Economic Analysis Computations

Personnel costs are the product of task hours and an hourly rate. Hourly rates were calculated using annual salaries for Duke University Medical Center job classes. We assumed a 35% fringe benefit rate, a 50% indirect cost rate, and an average of 30 direct labor hours per week. The computations and resulting hourly rates are shown in Table 1. Annual salaries ranged from $103,747 for the Lead Institution PI Staff to $63,729 for the sIRB Staff and Relying Site Administrative Staff. The inclusion of fringe benefits and indirect costs significantly increased the total annual costs for each role.

Table 1.

Personnel Costs

| Group | Role | Annual Salary | Total Cost | Hourly Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sIRB | sIRB Administrator | $89,630 | $181,501 | $116 |

| sIRB Staff | $63,729 | $129,051 | $83 | |

| Lead Institution Principal Investigator | Lead Institution PI Staff | $103,747 | $210,088 | $135 |

| Relying Site Principal Investigator | Relying Site PI Staff | $92,213 | $186,731 | $120 |

| Relying Site Administration Staff | $63,729 | $129,051 | $83 |

Notes: Total cost = annual salary * 35% fringe benefits * 50% indirect costs

Hourly rate assumes an average of 30 direct labor hours per week.

RESULTS

sIRB Workflows

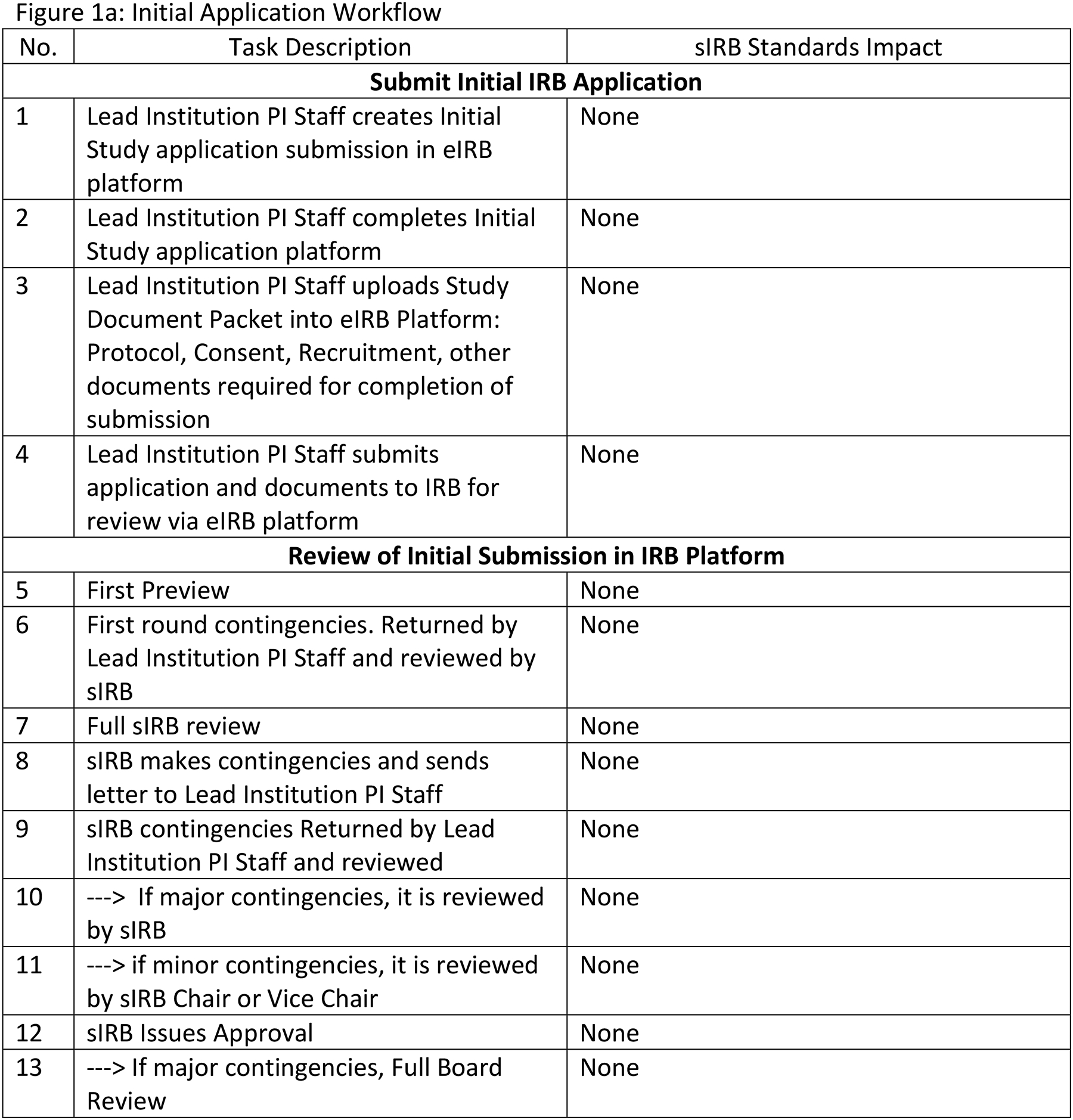

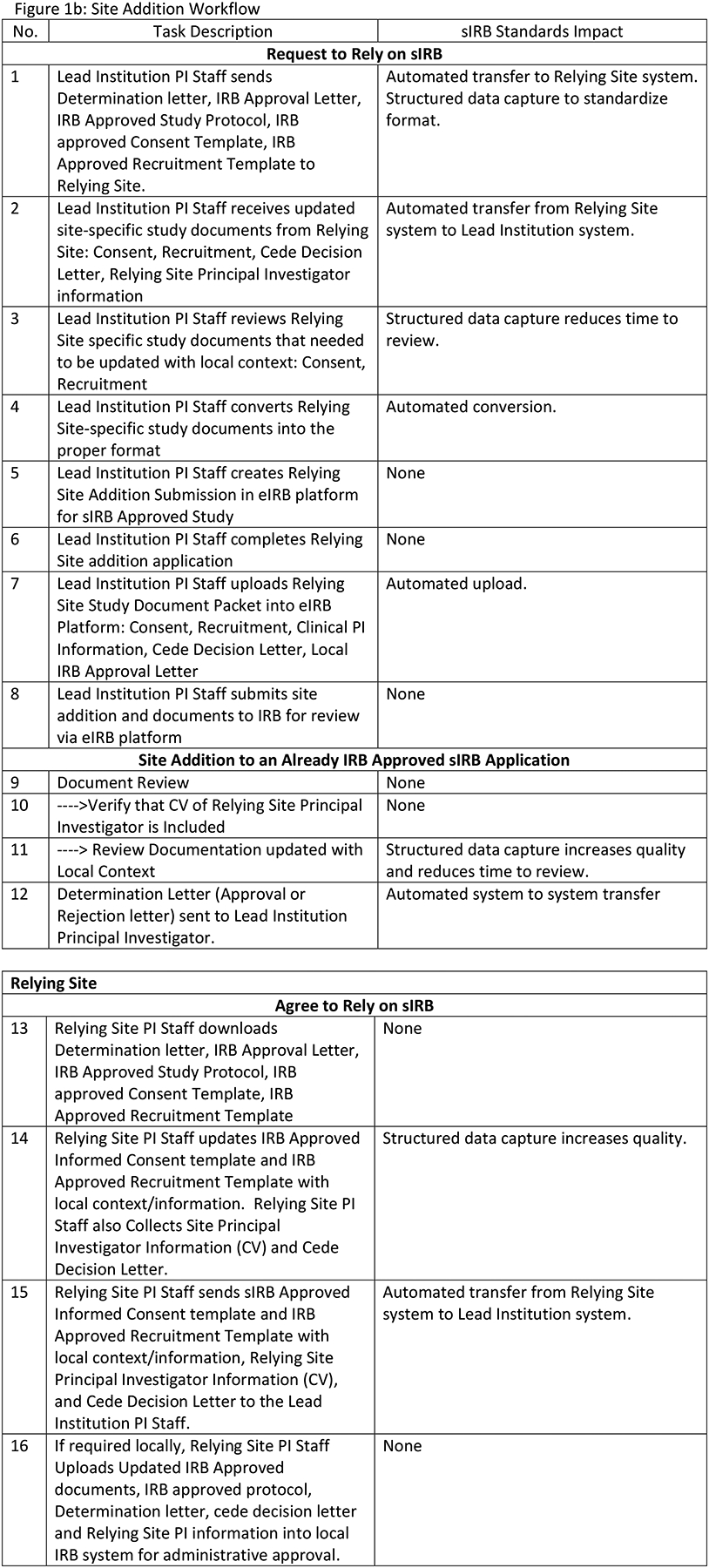

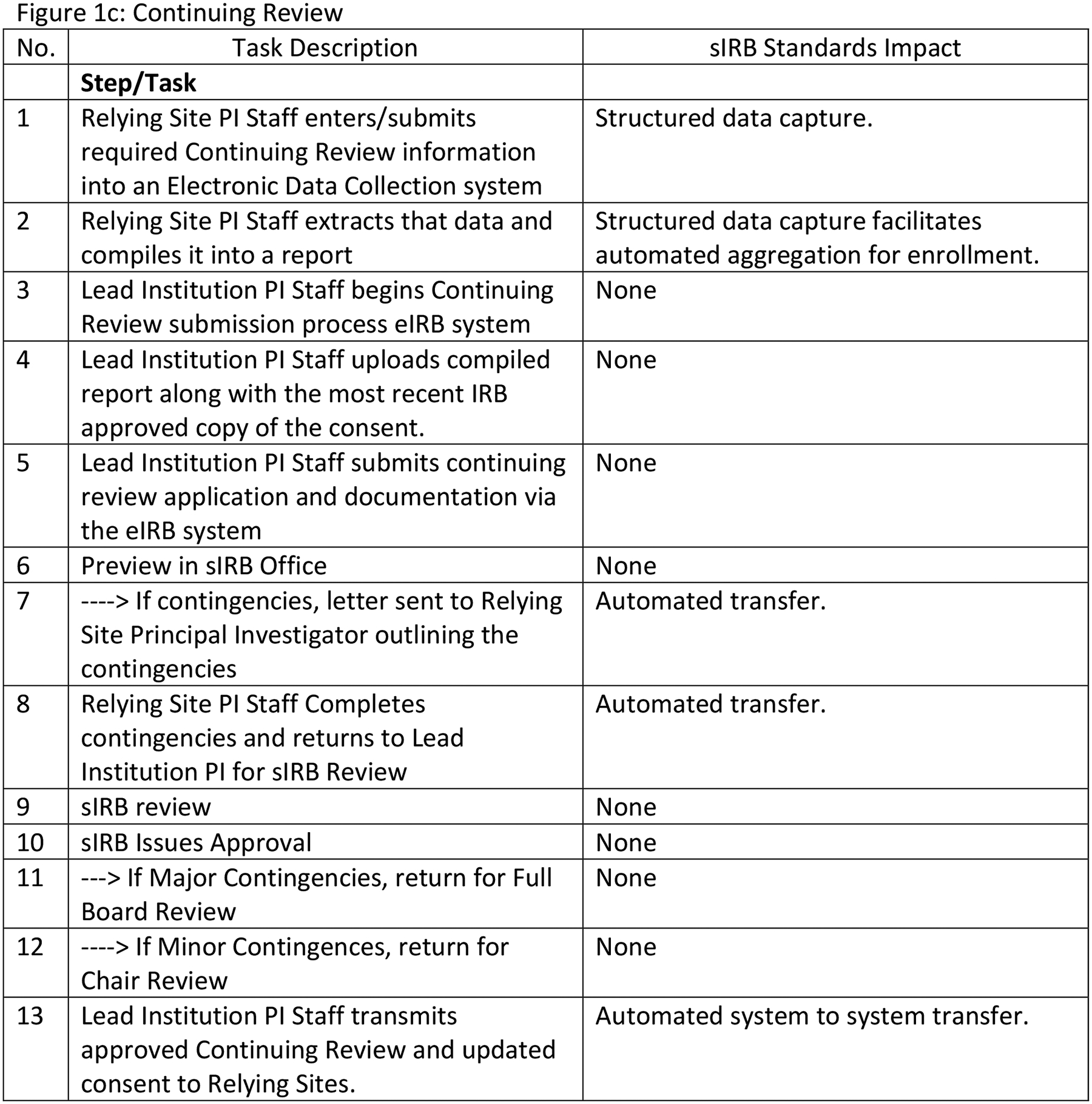

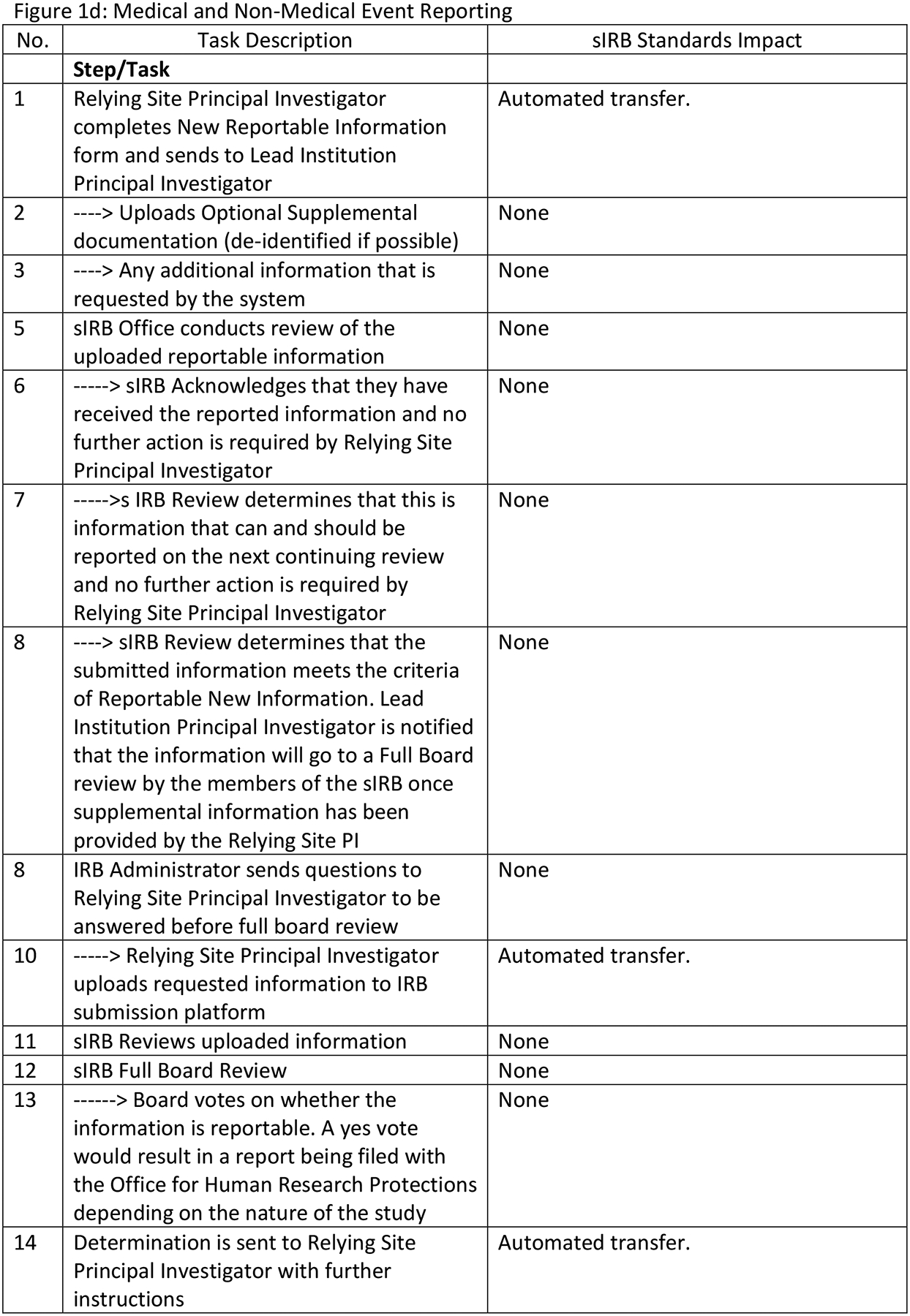

Figure 1 describes the four sIRB workflows before HL7 FHIR® sIRB standard implementation with estimated standard impacts. Our team assumed that implementing the data exchange standard would not eliminate tasks in the Initial Application and Reportable Events workflows. However, tasks would be eliminated in the Continuing Review and Site Addition workflows. Figure 1a describes the Initial Application workflow. Although data exchange standard implementation undoubtedly would alter this workflow, tasks would not be eliminated. Figure 1b describes the Site Addition workflow. Time savings would occur through the automated transmission of forms between systems (Steps 1, 2, 12, 15) and through eliminating the need to convert forms from one format to another. (e.g., MS Word to PDF) (Step 4). There would be additional savings because structured data capture would control which fields could be changed by the Relying site and potentially reduce multiple iterations of form completion. Figure 1c describes the Continuing Review workflow. Savings in this workflow would come from improved communications between the Study IRB Administrator and the Relying Site Staff (Steps 7, 8, 13) as well as efficiencies from the partial automation of patient enrollment report creation (Steps 1, 2). Figure 1d describes the Reportable Event workflow. Use of the data exchange standard clearly would alter this workflow but tasks would not be eliminated.

Figure 1:

sIRB Workflow Descriptions

Workflow Personnel Hours

Table 2 reports workflow level personnel hours by functional group and role. Total workflow hours are higher for the Initial Submission and Continuing Review workflows and lower for the Site Addition and Reportable Events workflows. The Initial Submission workflow required 38.00 hours per study of which 28.00 hours were for the Lead Institution PI Staff. The Site Addition workflow saved 2.50 hours per Site with data exchange standard implementation (reduced from 15.50 hours per Site to 13.00 hours). All functional groups would have small effort reductions (range 0.50 to 1.00 hours per Site) with standard implementation. The Continuing Review workflow saved 9.00 hours per Site per Study Year (reduced from 36.50 hours per Site per Study Year to 27.50 hours) with the Relying Site PI Staff time reduced by 5.00 hours per Study Year (from 20.00 hours per Study Year to 15.00 hours). The Reportable Events workflow required 12.00 hours per Event. All functional groups contributed effort toward this workflow.

Table 2.

Workflow Level Personnel Use (Hours)

| Initial Submission (Per Study) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Role | Without Standard | Change | With Standard |

| Single IRB | sIRB Administrator | 4.00 | 4.00 | |

| sIRB Staff | 6.00 | 6.00 | ||

| Lead Institution Principal Investigator | Lead Institution PI Staff | 28.00 | 28.00 | |

| Total | 38.00 | 38.00 | ||

| Site Addition (Per Site) | ||||

| Group | Role | Without Standard | Change | With Standard |

| Single IRB | sIRB Administrator | 2.00 | 2.00 | |

| sIRB Staff | 2.00 | (1.00) | 1.00 | |

| Lead Institution Principal Investigator | Lead Institution PI Staff | 3.75 | (0.50) | 3.25 |

| Relying Site Principal Investigator | Relying Site PI Staff | 1.75 | (0.50 | 1.25 |

| Relying Site Administration Staff | 6.00 | (0.50) | 5.50 | |

| Total | 15.50 | (2.50) | 13.00 | |

| Continuing Review (Per Site and Study Year) | ||||

| Group | Role | Without Standard | Change | With Standard |

| Single IRB | sIRB Administrator | 4.25 | 4.25 | |

| sIRB Staff | 4.25 | 4.25 | ||

| Lead Institution Principal Investigator | Lead Institution PI Staff | 4.00 | (2.00) | 2.00 |

| Relying Site Principal Investigator | Relying Site PI Staff | 20.00 | (5.00) | 15.00 |

| Relying Site Administration Staff | 4.00 | (2.00) | 2.00 | |

| Total | 36.50 | (9.00) | 27.50 | |

| Medical and Non-Medical Event Reporting (Per Event) | ||||

| Group | Role | Without Standard | Change | With Standard |

| Single IRB | sIRB Administrator | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| sIRB Staff | 3.00 | 3.00 | ||

| Lead Institution Principal Investigator | Lead Institution PI Staff | 3.00 | 3.00 | |

| Relying Site Principal Investigator | Relying Site PI Staff | 4.00 | 4.00 | |

| Relying Site Administration Staff | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Total | 12.00 | 12.00 | ||

Workflow Personnel Costs

Table 3 reports workflow level personnel costs by functional group and role. Total workflow costs are higher for the Initial Submission and Continuing Review workflows and lower for the Site Addition and Reportable Event workflows. The Initial Submission workflow’s total cost was $4733 per Study of which $3771 was for the Lead Institution PI Staff. The Site Addition workflow saved $251 per Site with data exchange standard implementation (reduced from $1609 to $1358). All functional groups would have small cost reductions (range $41 to $83) with standard implementation. The Continuing Review workflow saved $1033 per Site per Study Year (reduced from $4110 to $3076). Each Relying Site PI Staff would save $599 per study year. The Reportable Event total cost was $1330 per Event. All functional groups incurred costs for this workflow.

Table 3.

Workflow Level Personnel Costs

| Initial Submission (Per Study) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Role | Without Standard | Change | With Standard |

| Single IRB | sIRB Administrator | $465 | $465 | |

| sIRB Staff | $496 | $496 | ||

| Lead Institution Principal Investigator | Lead Institution PI Staff | $3771 | $3771 | |

| Total | $4733 | $4733 | ||

| Site Addition (Per Site) | ||||

| Group | Role | Without Standard | Change | With Standard |

| Single IRB | sIRB Administrator | $233 | $233 | |

| sIRB Staff | $165 | −$83 | $83 | |

| Lead Institution Principal Investigator | Lead Institution PI Staff | $505 | −$67 | $438 |

| Relying Site Principal Investigator | Relying Site PI Staff | $209 | −$60 | $150 |

| Relying Site Administration Staff | $496 | −$41 | $455 | |

| Total | $1609 | −$251 | $1358 | |

| Continuing Review (Per Site and Study Year) | ||||

| Group | Role | Without Standard | Change | With Standard |

| Single IRB | sIRB Administrator | $494 | $494 | |

| sIRB Staff | $352 | $352 | ||

| Lead Principal Investigator | Lead Institution PI Staff | $539 | −$269 | $269 |

| Relying Site Principal Investigator | Relying Site PI Staff | $2394 | −$599 | $1795 |

| Relying Site Administration Staff | $331 | −$165 | $165 | |

| Total | $4110 | −$1033 | $3076 | |

| Medical and Non-Medical Event Reporting (Per Event) | ||||

| Group | Role | Without Standard | Change | With Standard |

| Single IRB | sIRB Administrator | $116 | $116 | |

| sIRB Staff | $248 | $248 | ||

| Lead Principal Investigator | Lead Institution PI Staff | $404 | $404 | |

| Relying Site Principal Investigator | Relying Site PI Staff | $479 | $479 | |

| Relying Site Administration Staff | $83 | $83 | ||

| Total | $1330 | $1330 | ||

Clinical Study Simulation Cost Savings

Table 4 simulates functional group cost savings after data exchange standard implementation. Cells in this table show cost savings (total and by functional group) assuming different combinations of clinical study sites and study years. With a minimum of two sites and one study year, there is $2569 in sIRB-associated total cost savings that primarily accrue to the Relying Site Principal Investigator ($1731). As the number of follow-up years increases, the savings are magnified. With two sites and four study years there is $8769 total savings, with $6314 savings for the Relying Site Principal Investigator. Similarly, as the number of study sites increase, the sIRB-associated cost savings increase as well. With four study sites in a one-year study, the sIRB-associated cost savings are twice those with only two study sites ($5138 vs. $2569) as are the Relying Site Principal Investigator costs ($3460 vs. $1731). These cost savings continue to increase as the number of study sites and study years are increased.

Table 4.

Clinical Trial Simulation Cost Savings

| Number of Sites | Functional Group | Number of Study Years | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | ||

| 2 Sites | Single IRB | $165 | $165 | $165 | $165 |

| Lead Institution Principal Investigator | $673 | $1212 | $1751 | $2289 | |

| Relying Site Principal Investigator | $1731 | $3259 | $4786 | $6314 | |

| Total | $2569 | $4636 | $6702 | $8769 | |

| 4 Sites | Single IRB | $331 | $331 | $331 | $331 |

| Lead Institution Principal Investigator | $1347 | $2424 | $3501 | $4579 | |

| Relying Site Principal Investigator | $3460 | $6516 | $9572 | $12,628 | |

| Total | $5138 | $9271 | $13,405 | $17,538 | |

| 8 Sites | Single IRB | $662 | $662 | $662 | $662 |

| Lead Institution Principal Investigator | $2693 | $4848 | $7003 | $9158 | |

| Relying Site Principal Investigator | $6922 | $13,033 | $19,145 | $25,256 | |

| Total | $10,277 | $18,543 | $26,809 | $35,076 | |

| 16 Sites | Single IRB | $1324 | $1324 | $1324 | $1324 |

| Lead Principal Investigator | $5387 | $9696 | $14,006 | $18,315 | |

| Relying Site Principal Investigator | $10,534 | $20,110 | $29,685 | $39,261 | |

| Total | $20,553 | $37,086 | $53,618 | $70,151 | |

| 32 Sites | Single IRB | $2647 | $2647 | $2647 | $2647 |

| Lead Institution Principal Investigator | $10,774 | $19,393 | $28,012 | $36,631 | |

| Relying Site Principal Investigator | $21,067 | $40,219 | $59,371 | $78,523 | |

| Total | $41,106 | $74,171 | $107,237 | $140,302 | |

DISCUSSION

Use of the proposed HL7 FHIR® sIRB data exchange standard was associated with sIRB workflow cost reductions. These cost reductions were primarily observed in the Continuing Review workflow and secondarily in the Site Addition workflow. There were no cost reductions in the Initial Submission and Reportable Events workflows. Because the Continuing Review workflow occurs once per site per study year, these cost reductions are magnified in multi-center clinical studies as the number of sites and study years increase. However, the most important cost driver is the number of study years. Clearly, these results are dependent upon the personnel cost and workflow hour reductions included in our economic model. sIRBs and Relying Sites with lower personnel costs will have lower cost savings. Similarly, sIRBs with different workflows will experience higher or lower cost savings dependent upon the degree to which the proposed HL7 FHIR® sIRB data exchange standard impacts those workflows. Previous researchers have commented that it is difficult to attribute outcomes directly to sIRB policy changes in the clinical research environment after the sIRB model has been implemented (17–21). However, we are modeling the expected economic benefits associated with proposed data exchange standard. Hence, these criticisms do not apply.

Although ours is the first study to investigate the impact of the proposed HL7 FHIR® sIRB data exchange standard upon sIRB workflow economics, others studies have considered the potential cost savings associated with sIRBs (22). As multisite clinical studies have struggled to implement sIRBs those benefits largely have not been achieved (23). Part of the problem is that IRBs are adding sIRB functions onto existing workflows and exchanging documents with multiple sites requires standardization. While this may be a reasonable short-term solution, there are major limitations that cannot be overcome without addressing the complex and repetitive interactions between sIRBs and their Relying sites. An advantage of the proposed HL7 FHIR® sIRB data exchange standard is that it will standardize these workflows and provide a common way for Relying sites to interact with all of their multisite clinical study sIRBs who are using different eIRB information systems. As it is, a Relying site may have different workflows for each of their multisite clinical trials.

Our study has several limitations. First, our analysis did not include the costs to implement the proposed HL7 FHIR® sIRB data exchange standard and integrate it with existing IRB systems. These would be infrastructure costs incurred by reviewing and relying institutions and by their IRB software vendors. Our assumption was that the standard would be included in new releases of the existing IRB and data management systems. To the extent this happens, the incremental costs to the sIRB would be limited to the effort required to update standard operating procedures impacted by the standard’s new functionality. However, if additional costs were incurred, they would be more than equaled by the costs savings we have demonstrated for multisite clinical studies. Second, our costs are for a single sIRB and may not be applicable to sIRBs with different cost structures. While we believe our results are valid for the Duke University Medical Center sIRB, we also believe similar results could be achievable for sIRB-associated workflows at other institutions. Our cost saving estimates were conservative in that we only considered tasks that would be eliminated and did not consider economic benefits accruing from tasks that would be modified by the data exchange standard. Thus, we believe that all sIRBs potentially could benefit from the use of the standard.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that the use of proposed HL7 FHIR® sIRB data exchange standard could be economically attractive for sIRB workflows collectively and for each entity participating in the new sIRB workflows. Once these standards are implemented, subsequent research should determine whether our project cost savings have been realized and whether there are additional cost savings from sIRB tasks that are modified but not eliminated by the standard.

Funding Acknowledgement

The work reported here was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Award Number UL1TR002553-S to Duke University, UL1TR003107 to the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, and UL1TR002645 to the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. The content is solely the responsibility of the author(s) and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Appendix

Single Institutional Review Board (sIRB) Implementation Guide

Project Context

The Health Level Seven (HL7) organization supports international electronic data exchange standards for the transfer and sharing of healthcare clinical and administrative data between software applications. These standards are needed because health care organizations use a variety of computer systems that need to communicate with each other. As examples, physicians need to transmit orders to pharmacies, laboratories need to communicate test results to physicians, and hospitals need to communicate billing information to insurers. HL7 standards provide common formats for the exchange of these data.

Fast Health Interoperability Resources (FHIR) is an HL7 standard that describes resources (data elements and their formats) and an application programming interface (API) for exchanging electronic health records. In 2020, the U.S. Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) issued the Interoperability and Patient Access rule requiring FHIR use by CMS-regulated payers. Under this rule, FHIR APIs were required for Patient Access, Provider Directories, and Payer-to-Payer exchange. Meanwhile, other agencies are harmonizing regulations to facilitate FHIR adoption. As an example, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Civil Rights has proposed changes to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) privacy rule to expand between-provider care coordination disclosures and personal health app access.

Currently, there are no data standards for the exchange of Institutional Review Board-related documents and data between clinical research sites and ethics review boards. The Single Institutional Review Board (sIRB) Implementation Guide seeks to address this deficiency.

Project Objectives

The sIRB data exchange project uses features of the FHIR Questionnaire resource to standardize research study forms for exchanging data between relying institutions and their sIRBs. The project’s products are the set of Questionnaire Responses that will be exchanged. Upon adoption, the sIRB forms will replace existing sIRB media (e.g., paper forms, word processing documents, local IRB software forms).

Project Scope

The sIRB Implementation Guide includes seven sIRB-related research documents: (1) Determination Letter, (2) Protocol, (3) Consent Form, (4) Recruitment Materials, (5) Adverse Medical Events, (6) Non-Medical Events, and (7) Continuing Review. The Protocol, Consent and Recruitment Material forms are included in the initial sIRB submission. The Determination Letter us used by the sIRB to communicate with Relying Sites. The Adverse Medical Event, Non-Medical Event, and Continuing Review forms are used by Relying sites and the sRIB during the study’s conduct. The standard also includes an Initiate a Study form that collects data common to the seven sIRB-related forms.

The current sIRB Implementation Guide describes the creation and exchange of the seven sIRB forms using the FHIR questionnaire and questionnaire response resources. Form pre-population using the Initiate a Study form will be covered in future implementation guide versions.

The sIRB Implementation Guide assumes three actors: (1) sIRB Form Repository, (2) Central IRB Application, and (3) Relying IRB Application. The sIRB Form Repository stores standardized sIRB forms that are requested as templates by other IRB applications. The Central IRB and Relying IRB Applications are enhanced versions of existing applications used by these two entities.

References

- 1.Flynn KE, Hahn CL, Kramer JM, et al. Using central IRBs for multicenter clinical trials in the United States. PLoS One 2013;(1):e e54999.doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054999. Epub 2013 Jan 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), IRB Reliance: A New Model for Accelerating Translational Science. Available from https://ncats.nih.gov/pubs/features/irb-reliance. Accessed May 8, 2017.

- 3.Klitzman R The Ethics Police? The Struggle to Make Human Research Safe. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menikoff J, The paradoxical problem with multiple-IRB review. N Engl J Med. 2010. Oct 21;363(17):1591–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krafcik BM, Doros G, Malikova MA. A single center analysis of factors influencing study start-up times in clinical trials. Future Sci OA 2007. Jul 14;3(4):FSO223. doi: 10.4155/fsoa-2017-0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbott D, Califf RM, Morrison BW, et al. Cycle time metrics for multisite clinical trials in the United States. Ther Innov Regul Sci. 2013. Mar;47(2):152–160. doi: 10.1177/2168479012464371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neuman MD, Gaskins L, Ziolek T and the REGAIN Investigators. Time to institutional review board approval with local versus central review in a multicenter pragmatic trial. Clinical Trials 2018;15(1):107–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goyal A, Schibler T, Alhanti B, et al. Assessment of North American clinical research site performance during the start-up of large cardiovascular clinical trials. JAMA Network Open 2021;4(7): e2117963. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.17963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NIH16 - National Institutes of Health. Final NIH Policy on the Use of a Single Institutional Review Board for Multi-Site Research. June 21, 2016. Notice Number: NOT-OD-16-094. Retrieved from https://grants.nih.gov/policy/humansubjects/single-irb-policy-multi-site-research.htm

- 10.Grady C Institutional review boards: purpose and challenges. Chest. 2015;148(5):1148–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolinetz CD, Collins FS. Single-minded research review: the common rule and single IRB policy. Am J Bioeth. 2017;17(7):34–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Obeid JS, Alexander RW, Gentilin SM, et al. IRB reliance: an informatics approach. J Biomed Inform. 2016;60:58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammond WE. HL7—more than a communications standard. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2003;96:266–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.HL7 FHIR® Single Institutional Review Board Project (sIRB) Implementation Guide (v0.1.0 – CI Build). https://build.fhir.org/ig/HL7/fhir-sirb Accessed August 16, 2022.

- 15.Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative. Evaluation Framework for the NIH Single IRB Policy, September 13, 2019, p.22. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative. Evaluation Framework for the NIH Single IRB Policy, September 13, 2019, p. 4, 21. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diamond MP, Eisenberg E, Huang H, et al. The efficiency of single institutional review board review in National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Cooperative Reproductive Medicine Network-initiated clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2019;16(1):3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaufmann P, O’Rourke PP. Central institutional review board review for an academic trial network. Acad Med. 2015;90(3):321–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Massett HA, Hampp ST, Goldberg JL, et al. Meeting the Challenge: The National Cancer Institute’s Central Institutional Review Board for Multi-Site Research. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(8):819–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bingley PJ, Wherrett DK, Shultz, et al. Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet: A multifaceted approach to bringing disease-modifying therapy to clinical use in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(4):653–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative. Evaluation Framework for the NIH Single IRB Policy, September 13, 2019, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagner TH, Murray C, Goldberg, et al. Costs and benefits of the National Cancer Institute Central Institutional Review Board. J Clin Oncol. 2009;28:662.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative. Evaluation Framework for the NIH Single IRB Policy, September 13, 2019.