Abstract

Study Objectives:

The objectives of this study were to describe the reach and adoption of Geriatric Emergency Department accreditation (GEDA) program and care processes instituted at accredited geriatric emergency departments (GEDs).

Methods:

We analyzed a cross-section of a cohort of United States (US) emergency departments that received GEDA from 5/2018–3/2021. We obtained data from the American College of Emergency Physicians and publicly available sources, including GEDA level, geographic location, urban/rural designation, and care processes instituted. Frequency and proportions, and median and interquartile ranges were used to summarize categorical and continuous data, respectively.

Results:

Over the study period, 225 US GED accreditations were issued and included in our analysis: 14 Level 1, 21 Level 2, and 190 Level 3 GEDs; five GEDs re-applied and received higher level accreditation after initial accreditation at a lower level. Only 9 GEDs were in rural regions. There was significant heterogeneity in protocols enacted at GEDs; minimizing urinary catheter use and fall prevention were the most common.

Conclusions:

There has been rapid growth in GEDs, driven by Level 3 accreditation. Most GEDs are in urban areas, indicating the potential need for expansion beyond these areas. Future research is needed evaluating the impact of GEDA on health care utilization and patient-oriented outcomes.

Keywords: Geriatrics, Aged, Emergency Medicine, Emergency Service, Hospital, Accreditation

Introduction

Background:

As the United States (US) population ages, the healthcare system is increasingly challenged to provide high quality care to older adults. Older adults increasingly require care in emergency departments (EDs) and typically have more extensive evaluations and are more likely to be admitted.1 However, hospitalization also carries risk for older adults, including functional and cognitive decline.2,3

Geriatric EDs (GEDs) were first established in the US over a decade ago in response to the growing geriatric population and their unique emergency care needs.4 However, there was significant variation in staffing, equipment and care processes among these self-designated GEDs.5 In 2014, the Geriatric Emergency Department Guidelines were published to standardize and improve emergency care delivery in GEDs.6 In 2018, ACEP launched the Geriatric ED Accreditation (GEDA) program7 to accredit GEDs based on adherence to the guidelines. GEDA classifies accredited GEDs as Level 1 (gold), 2 (silver) or 3 (bronze) according to degrees of adherence to best practices. Higher level GEDs must meet greater requirements with respect to staffing, geriatric-specific protocols, outcome monitoring, equipment and environmental changes; costs of application are also greater for higher level GEDs (Supplement Figure S1).

Importance:

Since the establishment of the GEDA process over two years ago, there has been no systematic study describing accredited GEDs in the US.

Goals of this investigation:

The objectives of this study were to describe the reach and adoption of ACEP’s GEDA program in the US and geriatric improvement processes implemented across accredited GEDs.

Methods

Study design and setting:

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of a cohort of EDs that received GED accreditation by ACEP on or before March 1, 2021. This was a secondary analysis of previously collected data from the GEDA database; data were not collected specifically to meet the objectives of the study. This study adhered to the strengthening of reporting of observational study designs in epidemiology (STROBE).

Selection of Participants:

We included GEDs that applied for and received accreditation between May 7, 2018 and March 1, 2021. GEDs in countries other than the US were excluded since US classification systems were used to group EDs geographically. In addition, GEDs were excluded from some aspects of the study if data use agreement restrictions prevented review of the GEDA application for research purposes.

Measurements:

We obtained aggregate data on GED applications and approvals from the GEDA database. We reviewed individual applications to abstract data on ED visit volume, proportion of ED volume by individuals ≥65 years of age, primary reason for applying for GEDA, and geriatric-specific policies and protocols. Applications were reviewed after GED accreditation was issued. Zip code was used to classify the facility geographically based on US census region and as metropolitan or non-metropolitan based on 2013 Urban Influence Codes (UICs).8 GEDs with a UIC of 1 or 2 were classified as metropolitan and GEDs with UIC codes of 3 or greater were classified as non-metropolitan (rural). GEDs were also classified by affiliation with an emergency medicine residency program.

The GEDA application guide9 describes 27 potential policies or protocols to improve the emergency care of older ED patients. In the GEDA application, Level 1 and 2 applicants must classify their geriatric care initiatives into these categories; for Level 3 GEDs, a trained research assistant (RA) reviewed the quality initiative(s) described in the application and classified them using the same categories. This research did not involve human subjects, and utilized data from aggregate and anonymous sources, as well as publicly reported data; accordingly, IRB review was not required. Release of data was approved for comparison purposes via a data use agreement with all sites, except for one Level 1 GED which declined and was not included in the analysis and reporting.

Outcomes:

We identified accredited GEDs and GEDA level from the GEDA database.

Analysis:

Frequency and proportions were used to summarize categorical data and median and interquartile ranges (IQR) were used to summarize non-parametric continuous variables.

Results

Characteristics of accredited GEDs:

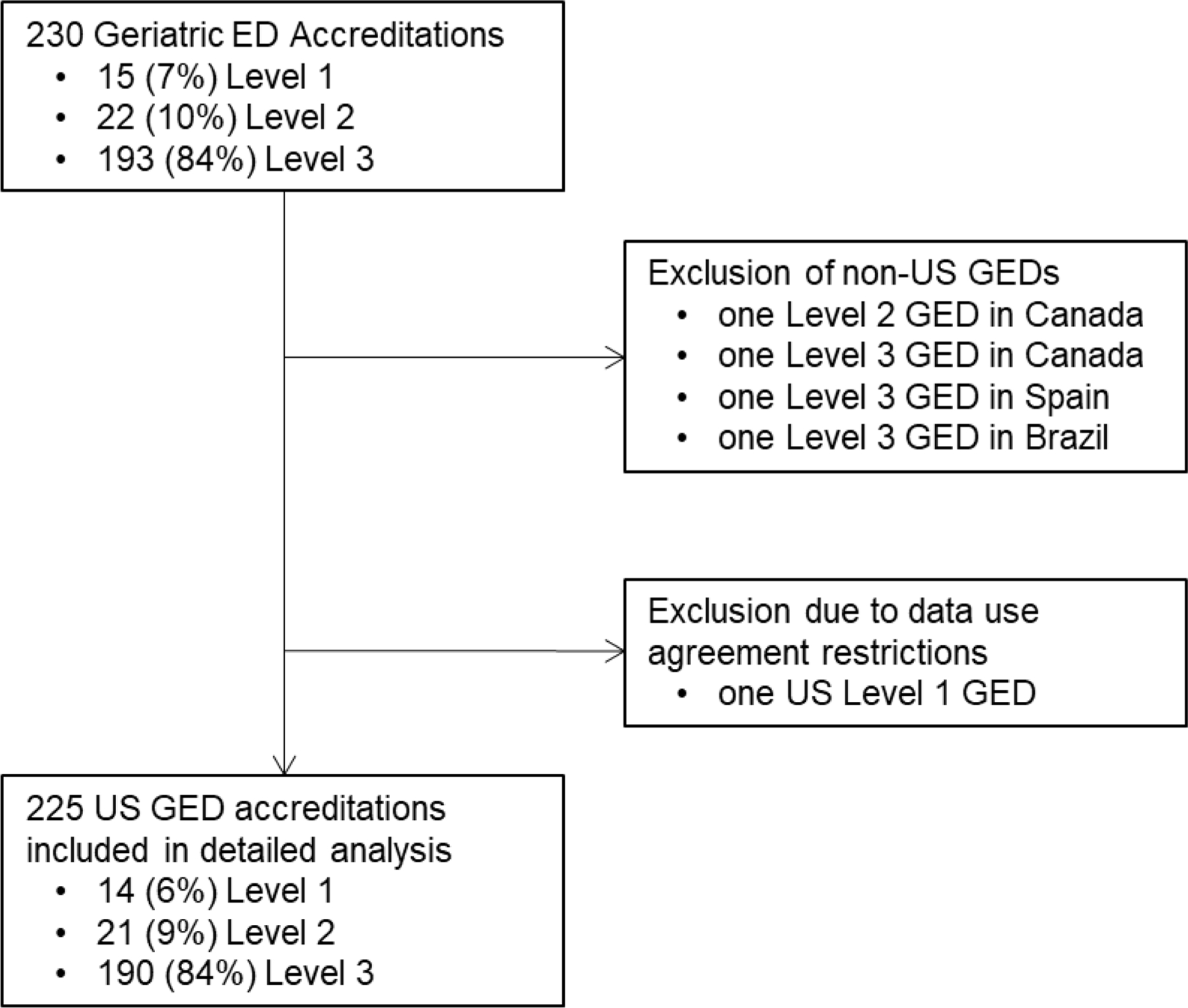

Since the GEDA program began through March 1, 2021, ACEP issued a total of 230 geriatric ED accreditations for a total of 225 EDs across 36 US states, as well as in Canada, Brazil and Spain. The vast majority of approved GEDs were Level 3 (Figure 1; Supplement Figure 1). Over the course of the study, five accredited GEDs applied for and were approved as higher level GEDs: three level 3 GEDs were subsequently accredited as level 2 GEDs, and one level 2 and one level 3 GED were subsequently accredited as level 1 GEDs. Five GEDs were excluded from further analysis: two Level 3 and one Level 2 non-US GEDs and one Level 1 US GED due to data-use-agreement restrictions (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Flow diagram of geriatric ED accreditations included in detailed analysis. Analysis included 225 GED accreditations from 220 EDs; five GEDs re-applied and were approved for a higher level of accreditation during study period. GED=Geriatric Emergency Department; ED=Emergency Department

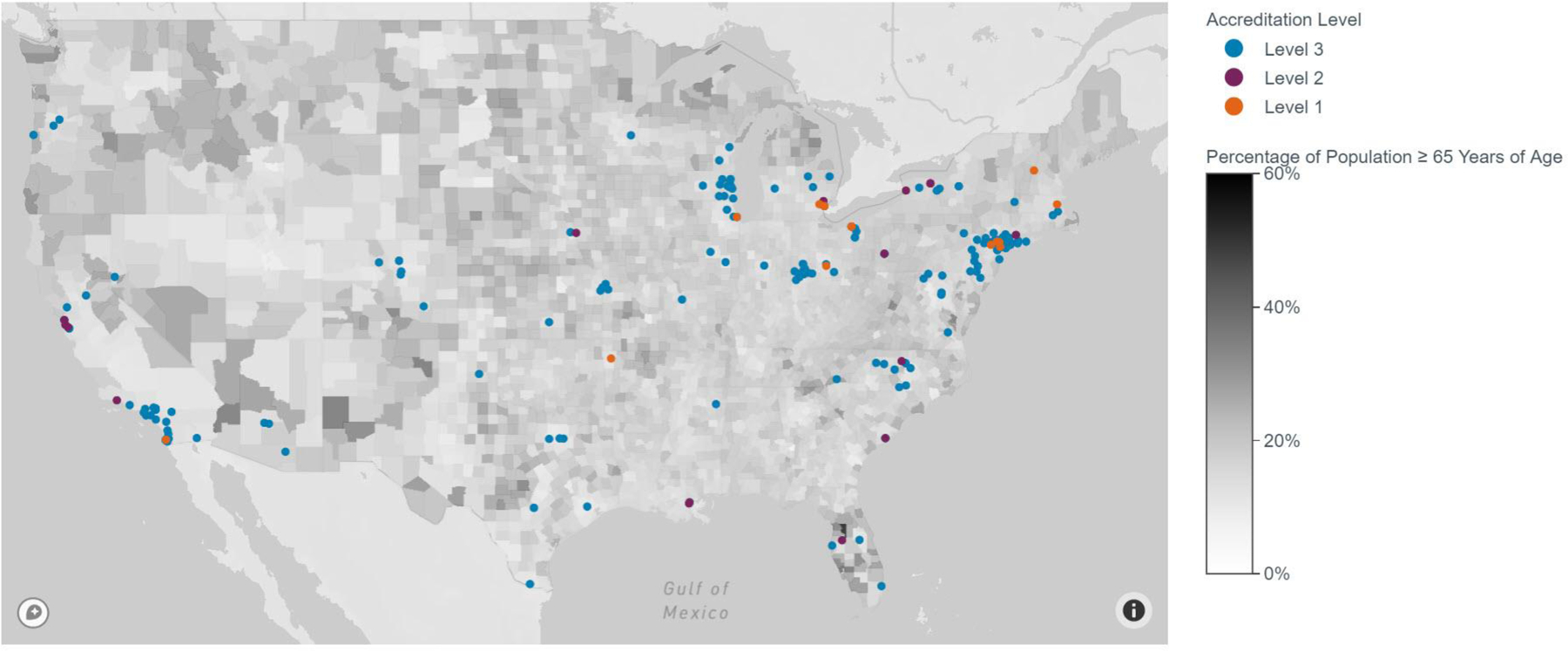

Characteristics for the 225 US GED accreditations included in our study are presented in Supplement Table 1. The most common reason cited for applying for GEDA was to improve care delivery to older adults. Across all GEDs, the median annual ED visit volume was 37,044 (interquartile range [IQR] 22,545 to 59,233) and visits by individuals 65 years of age or older comprised 25% (IQR 19 to 32%) of overall visit volume. The geographic distribution of accredited GEDs, superimposed on a heatmap reflecting the percent of the population that is aged 65 and older, is shown in Figure 2. Only 9 GEDs (4%) were in non-metropolitan regions, 8 of which were Level 3 (Supplement Table 1). Twenty-nine GEDs (13%) were affiliated with an emergency medicine residency program (Supplement Table 1).

Figure 2:

Geographic distribution of accredited geriatric emergency departments in the United States, by accreditation level, and superimposed on a heatmap that reflects the percent of the population that is aged 65 and older, by county.

Geriatric Care Processes

Geriatric care processes implemented at the included GEDs are listed in Table 1. The most common care processes implemented related to addressing geriatric falls (90/225, 40%), minimizing urinary catheter use (87/225, 39%), identifying elder abuse (53/225, 24%), addressing delirium (49/225, 22%) and identifying assessment of function and functional decline (47/225, 21%). Though Level 3 GEDs were only required to have one quality initiative for GEDA, one-quarter reported more than one care process in their application (48/190, 25%).

Table 1:

Geriatric specific protocols, policies, guidelines, or initiatives enacted at US GEDs.

| Protocol/ Policy, n (%) | Level 1 (n = 14) | Level 2 (n = 21) | Level 3 (n=190) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Program to minimization use of urinary catheters | 14 (100) | 20 (95) | 53 (28) |

| Process for identification of elder abuse | 14 (100) | 14 (67) | 25 (13) |

| Program to minimize use of physical restraints | 14 (100) | 14 (67) | 11 (6) |

| Access to palliative care consultation | 14 (100) | 11 (52) | 10 (5) |

| Geriatric pain control guidelines | 14 (100) | 11 (52) | 4 (2) |

| Program on geriatric fall assessment | 13 (93) | 18 (86) | 59 (31) |

| Process for PCP notification | 13 (93) | 14 (67) | 2 (1) |

| Access to transportation services for return to home | 13 (93) | 12 (57) | 0 (0) |

| Program to minimize use of potentially inappropriate medications | 13 (93) | 11 (52) | 9 (5) |

| Delirium screening process | 13 (93) | 9 (43) | 27 (14) |

| Process for care transitions to residential care facilities | 13 (93) | 8 (38) | 0 (0) |

| Guideline to define access to GED from ED triage* | 13 (93) | 6 (29) | N/A* |

| Process for medication reconciliation with a pharmacist | 12 (86) | 9 (43) | 16 (8) |

| Standardized assessment of function and functional decline | 12 (86) | 8 (38) | 27 (14) |

| Dementia screening process | 12 (86) | 5 (24) | 5 (3) |

| Guidelines to minimize NPO designation | 11 (79) | 7 (33) | 2 (1) |

| Program for access to short and long-term rehabilitation | 11 (79) | 5 (24) | 1 (0.5) |

| Program for volunteer engagement | 10 (71) | 5 (24) | 0 (0) |

| Guideline to promote mobility | 11 (79) | 3 (14) | 1 (0.5) |

| Process for post-discharge follow up | 11 (79) | 2 (10) | 3 (2) |

| Access to geriatric psychiatry consultation | 10 (71) | 5 (24) | 5 (3) |

| Program for home assessment of function and safety | 9 (64) | 6 (29) | 0 (0) |

| Access to geriatric specific outpatient clinics for follow up | 9 (64) | 5 (24) | 3 (2) |

| Order sets for ≥3 common geriatric presentations | 8 (57) | 9 (43) | 4 (2) |

| Program for community paramedicine follow up | 3 (21) | 2 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Outreach program to residential care homes | 1 (7) | 4 (19) | 0 (0) |

N=225 - one Level 1 GED was not included due to restrictions in the data use agreement. Level 1 GEDs are required to have at least 20 items and Level 2 GEDs are required to have at least 10 items from the GEDA model of care. Level 3 GEDs are required to have at least one quality initiative, which were reclassified into the GEDA model of care structure. Sites may have exceeded the number of required items. Five GEDs applied for and were accredited at a higher GEDA level; data from original and updated applications were both included under the respective accreditation level.

Not applicable to Level 3 GEDs. GED=Geriatric Emergency Department. ED=Emergency Department. PCP=Primary Care Physician. NPO= “Nil per os”/nothing by mouth.

Limitations:

This study has several limitations. Most data were extracted from the GEDA applications; errors in data entry by sites could have impacted our results. Additionally, the data only allow for a cross-sectional analysis of GEDs based on information provided at the time of accreditation, as opposed to tracking site characteristics and trends over time. Geriatric care processes at level 3 GEDs were classified by a single trained RA; though classifications were reviewed by at least one researcher, an assessment of inter-rater reliability was not performed. We were also unable to independently verify the accuracy or completeness of the data included in the application or validate the quality of geriatric emergency care delivered at these GEDs. However, the process for Level 1 GED accreditation includes a site visit to ensure the GED meets accreditation standards and Level 2 GEDs undergo a telephone site review. Additionally, some of the care processes may have already been enacted prior to deciding to apply for GED; however, as part of accreditation all GEDs must provide evidence that their GEDs actively monitor process and outcomes metrics related to these care processes. Lastly, we limited our analysis to US accredited GEDs; future studies may wish to study GED implementation outside of the US.

Discussion

Over the first two years of ACEP’s GEDA program, 230 GED accreditations were issued. The steady growth in accreditations and its reach to over 36 US states and internationally is one measure of success of this program. While there has been a rapid growth in accredited GEDs, this still accounts for only 4% of the 5,533 EDs in the US10 and, as demonstrated in the heat map, there remain swaths of the country without a GED.

One important consideration is whether GED growth geographically matches the growing population of older adults. The distribution of the GEDs in urban versus rural regions is particularly notable. Only 9 GEDs (4%) were in rural regions, 8 of which were Level 3 GEDs; however, in the US nearly one-fifth of all ED visits occur in the rural setting.11 Potential barriers to GEDA for rural EDs include costs of the application as well as expenses associated with staffing, managing, and equipment for GEDs. While the staffing requirements for higher level GEDs may be a particular challenge for rural EDs, which may have limited resources, financial constraints due to increasing numbers of Medicaid or uninsured patients, and difficulty recruiting and retaining staff,11 if achieved the benefits are universally appealing and can be shared and received by ED patients of all ages. For example, creating processes to facilitate care coordination with primary care physicians or referrals to community programs for older patients discharged home can also be extended to non-geriatric patients. Innovative solutions like leveraging telehealth to extend geriatric-focused interdisciplinary resources such as pharmacy, case management, social work, PT and occupational therapy can assist resource-constrained hospitals for patients of all ages. Such an endeavor is currently underway as a collaboration between the West Health Institute and Dartmouth–Hitchcock Connected Care and Center for Telehealth.12

It is also notable that the two most common quality initiatives enacted at level 3 GEDs align with national safety and reporting measures. Appropriate urinary catheter use is included in ACEP’s Clinical Emergency Data Registry and CMS Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). Fall risk assessment is another MIPS and National Quality Forum measure. GEDA aligns with such programs by recognizing hospitals who provide appropriate care by giving them status and raising the bar for care in all patients. This reinforces the idea that every ED in the US that cares for adults, including resource-constrained EDs, should be able to apply for level 3 GEDA. While this could also be viewed as a relatively low standard to achieve, GEDA requires specific outcome monitoring for these care processes, staff education in geriatric principles, and physician and nurse champions. As Level 3 GEDs reach the end of the 3-year approval period, they will also be required to demonstrate quality improvement to qualify for reaccreditation. Another measure of success for the GEDA program will be the proportion of accredited GEDs that reapply for GEDA, as well as the number that apply for a higher level of geriatric ED accreditation. Though this program has not reached the end of the first three-year approval period, to date 5 GEDs have applied for and received higher level of GEDA.

To ensure continued investment by hospital leaders, the GEDA program will need to be able to demonstrate a return on investment. There is growing evidence demonstrating the positive impact and benefits of Level 1 GEDs: having ED-based transitional care nurses or social workers perform structured assessments for older ED patients is associated with a reduced risk of hospital admission, 30-day readmission, and 30 and 60 days aggregate costs of care.13 Research evaluating the impact of level 2 and 3 GEDs on health care utilization, however, is limited. This is part because lower level GEDs are less likely to be academic institutions and data on impact is more likely to be collected for internal purposes that for publication. Future research will need to evaluate the impact of level 2 and level 3 GEDs. Evaluation of the impact of GEDA on patient-oriented outcomes, such as physical functioning, cognition, and quality of life, will also be an important avenue of research.14 Given the heterogeneity of care processes at accredited GEDs, demonstrating the value and impact of the GEDA program will be complicated by multiple confounders. This underscores the importance of leveraging existing geriatric ED-based research networks such as the Geriatric Emergency Care Applied Research network15 to evaluate the impact of GEDA and GEDs.

In summary, there has been a rapid growth in accredited GEDs in the US and internationally, driven by a desire to improve emergency care for older adults. Continued adoption of GEDA and extension of the program geographically will be important measures of programmatic success, as well whether GEDs apply for re-accreditation or for higher level accreditation. Research is needed on the impact of GEDA on health care utilization and patient-oriented outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Disclosures:

This study received funding support from the West Health Institute (La Jolla, CA). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of West Health. Lauren Southerland is supported by the National Institute of Health (K23AG06128401). Ula Hwang and Christopher Carpenter are supported by the NIH (R33AG058926, R61AG069822). Kevin Biese is supported by the NIH (R61AG069822).

Abbreviations:

- ED

Emergency Department

- GED

Geriatric Emergency Department

- GEDA

Geriatric Emergency Department Accreditation

- ACEP

American College of Emergency Physicians

- PCP

Primary Care Physician

- US

United States

- CMS

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

- APP

Advanced Practice Provider

- PIMs

Potentially Inappropriate Medications

- CAM

Confusion Assessment Method

- bCAM

brief Confusion Assessment Method

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Maura Kennedy, Nicole Tidwell, Kevin Biese and Ula Hwang currently serve on the board of governors of ACEP’s Geriatric ED accreditation (GEDA) program. Chris Carpenter previously served on the GEDA board of governors and currently serves on the GEDA advisory board. Shan Liu and Lauren Southerland are reviewers for the GEDA program.

Conflict of Interest: None

References:

- 1.Hwang U, Morrison RS. The geriatric emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55(11):1873–1876. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01400.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inouye SK, Westendorp RGJ, Saczynski JS. Delirium in elderly people. Lancet 2014;383(9920):911–922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60688-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krumholz HM. Post-Hospital Syndrome — An Acquired, Transient Condition of Generalized Risk. N Engl J Med 2013;368(2):100–102. doi: 10.1056/nejmp1212324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schumacher JG, Hirshon JM, Magidson P, Chrisman M, Hogan T. Tracking the Rise of Geriatric Emergency Departments in the United States. J Appl Gerontol 2020;39(8):871–879. doi: 10.1177/0733464818813030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hogan TM, Olade TO, Carpenter CR. A profile of acute care in an aging America: Snowball sample identification and characterization of united states geriatric emergency departments in 2013. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21(3):337–346. doi: 10.1111/acem.12332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carpenter CR, Bromley M, Caterino JM, et al. Optimal older adult emergency care: Introducing multidisciplinary geriatric emergency department guidelines from the American College of Emergency Physicians, American Geriatrics Society, Emergency Nurses Association, and Society for Academic Emergency Me. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62(7):1360–1363. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.“American College of Emergency Physicians.” ACEP Launches Geriatric Emergency Department Accreditation Program [Press Release]. May 10, 2018 https://www.acep.org/globalassets/sites/acep/media/geda-documents/gedapilotannoucement.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed October 26, 2020.

- 8.Unite Sates Department of Agriculture Economic Research Services. Urban Influence Codes https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/urban-influence-codes/documentation/. Published May 2013. Accessed October 26, 2020.

- 9.“American College of Emergency Physicians.” ACEP Geriatric ED Accreditation: Criteria for Levels 1, 2 & 3 https://www.acep.org/globalassets/sites/geda/documnets/GEDA-criteria.pdf. Accessed October 26, 2020.

- 10.Emergency Medicine Network. 2018 National Emergency Department Inventory – USA – Emergency Medicine Network http://www.emnet-usa.org/nedi/NEDI2018statedata.xls. Accessed December 4, 2020.

- 11.Greenwood-Ericksen MB, Kocher K. Trends in Emergency Department Use by Rural and Urban Populations in the United States. JAMA Netw open 2019;2(4):e191919. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ko KJ, Kurliand MM, Curtis KM, et al. Launching an Emergency Department Telehealth Program During COVID-19: Real-World Implementations for Older Adults - GEDC. J Geriatr Emerg Med 2020;1(7):1–7. https://gedcollaborative.com/article/jgem_vol1_issue7/. Accessed December 24, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hwang U, Dresden S, Vargas-Torres C, et al. Association of a Geriatric Emergency Department Innovation Program with Cost Outcomes Among Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Netw open 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Kennedy M, Ouchi K, Biese K. Geriatric Emergency Care Reduces Health Care Costs - What Are the Next Steps? JAMA Netw Open 2021;4(3):210147. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Building the Geriatric Emergency care Applied Research (GEAR) Network https://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_details.cfm?aid=9763414. Accessed March 5, 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.