Abstract

DNA fingerprinting methods have evolved as major tools in fungal epidemiology. However, no single method has emerged as the method of choice, and some methods perform better than others at different levels of resolution. In this review, requirements for an effective DNA fingerprinting method are proposed and procedures are described for testing the efficacy of a method. In light of the proposed requirements, the most common methods now being used to DNA fingerprint the infectious fungi are described and assessed. These methods include restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLP), RFLP with hybridization probes, randomly amplified polymorphic DNA and other PCR-based methods, electrophoretic karyotyping, and sequencing-based methods. Procedures for computing similarity coefficients, generating phylogenetic trees, and testing the stability of clusters are then described. To facilitate the analysis of DNA fingerprinting data, computer-assisted methods are described. Finally, the problems inherent in the collection of test and control isolates are considered, and DNA fingerprinting studies of strain maintenance during persistent or recurrent infections, microevolution in infecting strains, and the origin of nosocomial infections are assessed in light of the preceding discussion of the ins and outs of DNA fingerprinting. The intent of this review is to generate an awareness of the need to verify the efficacy of each DNA fingerprinting method for the level of genetic relatedness necessary to answer the epidemiological question posed, to use quantitative methods to analyze DNA fingerprint data, to use computer-assisted DNA fingerprint analysis systems to analyze data, and to file data in a form that can be used in the future for retrospective and comparative studies.

Interest in assessing the genetic relatedness of isolates of the same species has grown rapidly as we have delved deeper into the epidemiology of a variety of fungal diseases. Indeed, as molecular genetic approaches have evolved for unraveling the basic biology of particular fungal pathogens, so have methods for fingerprinting them at the genetic level. In 1985, there were 3 nonforensic publications that had “DNA fingerprinting” in the title or abstract, and in 1996, 11 years later, there were 318, and these did not include papers that used DNA fingerprinting techniques but did not reference them specifically as such. Although the recent availability of DNA fingerprinting techniques provides investigators and clinicians with tools for tracking strains and identifying the sources of particular infections, the variety of methods and the low level of sophistication applied in most cases to the analysis of data have led to problems with interpretation. Not all DNA fingerprinting methods are equally effective (see, e.g., references 151, 152, 208, and 288), and some can lead to misinformation. In the case of the infectious fungi, no single DNA fingerprinting technique has evolved as a dominant method, and in fact, each method has its own set of assets and limitations. In some cases, a method resolves differences between isolates, but because the method has not been adequately characterized, it is not clear how the differences can be interpreted in terms of genetic distance. In other words, it is not clear if resolved differences between isolates reflect minor changes representing the microevolution of a single strain over a short period or major differences between highly unrelated strains. When a potentially effective fingerprinting method is used, the user may not know how to interpret the results adequately. Even more worrisome is the continuous stream of published studies in which data that could have been quantitatively analyzed and then stored are dealt with by the authors in a superficial, qualitative, one-time manner. Indeed, the most wasteful aspect of DNA fingerprinting studies to date is the underutilization of data. With the advent of computer-assisted DNA fingerprint analysis systems, DNA fingerprint data can now not only be quantitatively compared but can also be normalized to a universal standard and then stored in a database so that every newly analyzed isolate can be compared retrospectively and quantitatively with every previously analyzed isolate of that species. Indeed, if a method is highly reproducible between laboratories, the data from different laboratories can be compared and pooled in a general data bank.

DNA fingerprinting of the infectious fungi has become an important subdiscipline of medical mycology. As DNA fingerprinting is more frequently applied to a variety of epidemiological problems, it becomes increasingly evident that there are “ins and outs” to the methods. Criteria can be used to assess the resolution of a particular fingerprinting method, and strategies have evolved to verify the efficacy of a fingerprinting method. Researchers can now assess beforehand whether a particular method will provide data that will answer the questions posed. In addition, criteria have evolved to assess whether a fingerprinting method is amenable to computer-assisted methods. Therefore, it seems timely that the various techniques now being used to fingerprint fungi infectious to humans be described, compared, and evaluated. In addition, the ground rules for selecting a method should be discussed and the major results of recent DNA fingerprinting studies should be reviewed within this context. These are the general objectives of this review. The discussion that follows will rely disproportionately upon examples from the fingerprinting literature of Candida albicans and related species, since I have worked primarily on these systems and can therefore draw more easily upon that literature in arguing particular points. However, the points that are made will be applicable to DNA fingerprinting of the infectious fungi in general.

QUESTIONS THAT REQUIRE DNA FINGERPRINTING

To understand the dynamics of an infectious organism in a human population, decipher the complex relationship between commensalism and infection, identify the origin of an infection, or monitor the emergence of drug-resistant strains, one must have a method for assessing genetic relatedness. Species typing is a necessary first step in all epidemiological studies, but one must have a way of assessing the relatedness of isolates within a species if one wants to understand many of the epidemiological questions that are posed. In the discussion that follows in this review, an isolate is defined as a clone collected independently of other isolates. Two independently collected isolates may be completely unrelated or genetically indistinguishable. In contrast, a strain refers to a collection of isolates of the same species that are highly related or genetically indistinguishable. To classify two isolates as belonging to the same strain or as members of different strains, one must have a DNA fingerprinting method that has been appropriately characterized to perform these functions. The need for sensitive DNA fingerprinting methods is especially important when diseases emanate from commensal organisms, when strains become specialized for particular body locations or compromising conditions, when strains undergo microevolution for rapid adaptation, or when strains are communicated between individuals. If a transplant recipient enters a hospital, is immunosuppressed, and then presents with a nosocomial bloodstream infection that proves to be due to a fungus, how is the origin of the infecting fungus elucidated? How does one distinguish an organism originating in the hospital from an organism that was a commensal in an anatomical location other than the bloodstream (e.g., the gastrointestinal tract) when the patient first entered the hospital? To discriminate between these alternatives, simply identifying the infecting strain for species is insufficient. If one identifies the strain as C. albicans, and over 50% of patients and hospital staff carry C. albicans as a commensal in one or more body locations, species typing tells us little about the origin of the infection. To identify the origin of the infecting organism, one must collect isolates from hospital workers who have interacted with the patient, the patient's immediate physical environment, visitors, and different body locations of the patient prior to and during hospitalization. One must then have a DNA fingerprinting system that is effective in discriminating between unrelated isolates, recognizing the same strain in different isolates, and recognizing highly related but nonidentical isolates (i.e., isolates that differ due to microevolution). The fingerprinting system must be verified for its effectiveness at these different levels of discrimination and must provide a database for estimating the probability that a particular strain identified by the particular DNA fingerprinting method will be isolated twice by chance in a particular geographical locale.

Consider another example that requires sophisticated fingerprinting. If a drug-resistant strain colonizes a patient and it becomes necessary to estimate the potential threat this strain poses to the general population, isolates from hundreds of individuals must be analyzed for both drug resistance and genetic relatedness. The DNA fingerprinting method must have sufficient resolving power to discriminate this particular strain from the majority of other strains in the geographical locale, and it must be amenable to computer-assisted analysis, especially if surveillance is to be performed over time with a significant number of isolates. Because comparisons of genetic relatedness between isolates fingerprinted at different times must be performed, the fingerprinting method must be reproducible and quantitative. There are many more examples of epidemiological problems and questions, each with its own set of demands on the technology of DNA fingerprinting and analysis. Fortunately, DNA fingerprinting methods that fulfill the majority of these demands and are within the technical capabilities of most medical mycologists have been developed for several pathogenic fungi. Criteria have been formulated that, if followed, will lead to the development or selection of fingerprinting methods that can be effectively used to obtain very good and sometimes definitive answers to many of the epidemiological questions medical mycologists might pose.

BIOTYPING IS INADEQUATE AS A DNA FINGERPRINTING METHOD

Before the development of DNA fingerprinting methods, researchers in medical mycology realized that not all fungal isolates of a given species exhibited the same general phenotype. Therefore, they reasoned that differences in phenotype reflected genetic differences between strains. Without methods for measuring differences or similarities at the level of DNA, they resorted to biotyping methods that reflected genotype. In 1950, Evans used agglutination tests to distinguish three serotypes, A, B, and C, of Cryptococcus neoformans (109). In 1968, Wilson and coworkers identified a fourth serotype, D (428). It was subsequently demonstrated that the most prevalent serotype in the United States was A (25) and that the dominant serotype in Thailand changed with the emergence of AIDS (378). The usefulness of serotyping C. neoformans has been confirmed by the large number of studies employing the method—more than 150 studies were identified in a MedLine search of the bibliography database in 1998, and that represented an underestimate. Serotyping alone, however, falls short as a strain-typing method. For instance, if the majority of isolates in a geographical locale are primarily one serotype, this method does not provide adequate strain resolution for most of the epidemiological questions posed.

One of the first biotyping strategies used to discriminate among C. albicans strains was also based on serotyping. Hasenclever and coworkers separated C. albicans strains into the two serotypes A and B (133, 134, 379), and this method has been used to type strains for the past 38 years (see, e.g., references 45, 103, 246, 258, 371, and 415). However, just as for Cryptococcus neoformans, separation of an entire species into a few groups does not provide meaningful resolution for the majority of epidemiological questions posed. In addition, it was demonstrated that different serotyping methods did not always group strains in the same manner. Three serotyping methods that had been established by 1990 for C. albicans included Hasenclever's original antisera HSN1 and HSN2 (133, 134, 379), the Iatron Candida Check factor 6 typing antiserum (IF6) (283), and agglutination with the monoclonal antibody H9 (45). Brawner (44) compared these serotype methods and demonstrated strong correlations between HSN1 and HSN2 and between these two antisera and H9 but not between IF6 and either HSN1, HSN2, or H9. Even more worrisome was the discovery that antigen expression could be affected by the phase of growth and, more importantly, that serotype B cells could produce serotype A antigen (283), which placed in question the entire methodology. For the A and B serotypes in C. albicans, the problem with variability probably lies in the fact that antigenicity is based on the polysaccharide moieties of the phosphomanno-protein complexes (227, 341, 394).

Realizing the shortcomings of serotyping, Odds and Abbott in the early 1980s developed the first complex biotyping protocol for distinguishing among Candida species and among strains of a species (240, 241). The rationale behind the Odds and Abbott method made sense. If one selects a large enough list of diverse phenotypic characteristics, the combined phenotype should reflect the genotype, even if a few of the selected characteristics proved to be sensitive to the environment and hence unreliable. The original method of Odds and Abbott (240) for species typing included nine assays that were quite easy to perform, involving the growth of cells of a cloned isolate on test agars with different compositions. These assays tested for growth at pH 1.4; production of secreted acid proteinase; resistance to flucytosine, boric acid, and safranin; assimilation of urea, sorbose, and citrate; and sensitivity to high salt. This list of assessed characteristics was effective in discriminating among species, and four additional tests, i.e., resistance to tetrazolium salts, sodium periodate, and cetrimide and growth on MacConkey agar, were used to supplement the preceding tests for discrimination among strains within a Candida species. Alterations in the method have also been developed to make it more amenable to general use (75). In the original application of this method to oral and vaginal isolates, 45 different types were identified (240), but the system had the potential for discriminating 512 types. The use of this biotyping strategy proved effective in a number of epidemiological studies (see, e.g., references 166, 189, 235, 244, 245, 247, 248, 276, 342, and 434), and if care was taken in standardizing methods, intralaboratory reproducibility could be achieved. Unfortunately, the Odds and Abbott biotyping system was found to have poor interlaboratory reproducibility among five laboratories (242). The conclusion of the authors of this latter study was that although this biotyping method was effective for research applications, it probably would not prove effective for clinical use. In addition to serotyping and the Odds and Abbott biotyping method, a number of other biotyping methods have been used to discriminate C. albicans strains, including morphotyping (145, 270, 293), resistotyping (144, 215), killer yeast typing (278, 279), enzyme typing (66, 424, 425), sugar assimilation typing (50, 105, 113, 120) and drug susceptibility typing (294). Isoenzyme biotyping has also been successfully applied to Candida species (52, 180, 288). However, because the different isoenzyme patterns in a method such as multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE) directly reflect allelic differences at defined loci and because MLEE outperforms several popular DNA fingerprinting methods in assessing genetic relatedness, it is dealt with separately in a following section.

Although biotyping methods became less popular with the emergence of DNA fingerprinting, the use of sugar assimilation profiles has remained the most popular method for rapid species identification. Commercial kits have been available for several years that assess the assimilation of more than 19 carbohydrates as the only source of carbon (50, 105, 113, 120), and their reliability in determining species is quite high (greater than 90%). In addition, an indicator agar referred to commercially as CHROMagar is now available that discriminates colorimetrically between species and is based upon the reduction of unnamed compounds (243, 263, 324). The CHROMagar method is probably not as discriminatory as the sugar assimilation kits, but the convenience of plating cells on a single indicator agar is unparalleled for preliminary identification of species and as an indicator of population homogeneity.

Although phenotype reflects genotype by definition, biotyping methods have fundamental problems that render them in some instances inadequate for discriminating among strains within a species. First, many of the assays in the Odds and Abbott method and in sugar assimilation profiles may be too sensitive to growth conditions; this is probably the reason why unacceptable levels of interlaboratory variability have been reported (242). As noted, even the expression of serotypes can be affected by growth (45, 283). Second, C. albicans and related species undergo spontaneous high-frequency switching among a limited number of general phenotypes (48, 239, 280, 305, 344, 345, 351, 359) that affects a variety of phenotypic traits, including antigenicity (2), sensitivity to antifungal agents (343, 356), uptake of dyes (4), secretion of acid proteinase (233) and assimilation of carbohydrates (350). These differences exist among the switch phenotypes of the same strain grown under the same growth conditions. For instance, C. albicans strain WO-1 switches reversibly and spontaneously at frequencies of approximately 10−3 between hemispheric white and flatter grey (opaque) colony phenotypes (345). The white-opaque transition results in dramatic changes in a variety of cellular traits (4, 351, 356) and the activation-deactivation of several white and opaque phase-specific genes (143, 232, 233, 248, 353, 354, 367, 418). White-phase cells will assimilate ribitol, xylitol, methyl-d-glucoside, and trehalose, but opaque-phase cells will not (350), and this pattern changes in a perfectly reversible fashion with each spontaneous switch. In addition, while white-phase cells secrete negligible amounts of aspartyl proteinase in either Lee's medium or serum-containing medium, opaque-phase cells secrete copious amounts (233); again, this change reverses with each spontaneous switch. Although most do not switch at high frequency, all isolates of C. albicans are capable of switching. In the minority of strains in which switching occurs at high frequency, the use of biotyping for strain discrimination could lead to erroneous results. Switching has also been demonstrated in Candida tropicalis (360), Candida glabrata (173), and Cryptococcus neoformans (127).

Recently, de Bernardis et al. (85) presented evidence that differences in pH in different host niches can dramatically affect the expression of several genes in C. albicans. As C. albicans multiplies in culture, it causes a continuous decrease in the pH of the medium. Cells may continually change their pattern of gene expression as the cell density increases and as the pH decreases. Therefore, if the growth conditions and time of harvesting are not precisely duplicated among experiments and laboratories, intralaboratory and interlaboratory reproducibility of biotyping methods will be compromised. In contrast, the basic DNA sequence of an organism can be presumed to be insensitive to short-term environmental change and thus should provide a more stable alternative for strain discrimination.

REQUIREMENTS FOR AN EFFECTIVE DNA FINGERPRINTING SYSTEM

To assess the relatedness of strains within a fungal species, a method must be used that measures relatedness at the genotypic level. Assessment at this level in most cases involves direct DNA measurements. Methods that directly measure DNA differences among strains within a species are henceforth referred to as DNA fingerprinting methods. For a DNA fingerprinting method to be effective for epidemiological purposes, it must fulfill certain general requirements. It should be kept in mind, however, that the stringency of these requirements will vary in relation to the defined objectives of each epidemiological study.

Resistance to Environmental Perturbations and High-Frequency Genomic Reorganization

Since the data obtained by any DNA fingerprinting method reflects the genetic relatedness among isolates, the genetic differences a particular method reveals must be due to evolutionary change. However, the rate of change of some DNA sequences may be inordinately affected by the environment or the physiological state of the cell. For instance, maintenance of a minichromosome or nonintegrated plasmid may be affected by growth conditions or cellular phenotype. A DNA fingerprinting method that targets such nonchromosomal DNA might therefore be unreliable. A DNA fingerprinting method must also be resistant to DNA reorganizational events that are affected by phenotype. For instance, C. albicans strain 3153A can undergo high-frequency phenotypic switching among seven general phenotypes (344, 351). In the dominant o-smooth phenotype, the organism switches to the other variant phenotypes at frequencies of less than 10−4, but when expressing a variant phenotype such as “star” or “irregular wrinkle,” the organism switches to other phenotypes at frequencies of approximately 10−2 (295, 344). When cells of strain 3153A are in the dominant and more stable o-smooth phenotype, their electrophoretic karyotype is relatively stable (295). However, when they express a less stable variant phenotype, their electrophoretic karyotype also becomes less stable, changing at extraordinarily high frequencies, primarily as a result of the nonreciprocal reorganization of rDNA cistrons in the two rDNA-containing chromosomes (295). Therefore, electrophoretic karyotypes of cells in a high-frequency mode of switching can rapidly diverge and converge in switching lineages (295). The convergence of karyotypic patterns leads to homoplasy, defined as common characteristics that do not have a common ancestry. Homoplasy is a characteristic that is inconsistent with the goals of a fingerprinting method. Recently, B. B. Magee and P. T. Magee (personal communication) discovered that the electrophoretic karyotypes of C. dubliniensis was hypervariable and that the reorganization of non-rDNA-containing chromosomes was also involved. Although high-frequency changes such as those noted for C. albicans and C. dubliniensis karyotypes may interfere with the capacity to distinguish between moderately related and unrelated strains, they can be used effectively to assess microevolution within an infecting strain (192). However, the demonstration of high-frequency reorganization and homoplasy reduces the effectiveness of karyotyping as a general DNA fingerprinting method for C. albicans.

If an organism undergoes reversible high-frequency DNA reorganization at specific loci in association with phenotypic switching, as occurs in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (125), Escherichia coli (125), and Borrelia hermsii (16), or if an organism undergoes irreversible DNA reorganization at specific loci in association with antigenic switching, as occurs in Trypanosoma brucei (99) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (383), the sequences at these loci should not be employed in a general DNA fingerprinting method. In the setting of reversible reorganization, the system will inherently lead to homoplasy.

Data Should Reflect Genetic Distance

The requirement that the data should reflect genetic distance is, perhaps, the trickiest and most important requirement. Many methods elucidate genotypic traits that are stable within a strain but vary among strains and therefore are reasonably effective in identifying the same strain and distinguishing among unrelated strains in independent isolates. Problems arise, however, when the researcher wishes to group isolates into moderately related clusters or identify microevolution within a strain. An effective DNA fingerprinting system should (i) identify the same strain in independent isolates, (ii) identify microevolutionary changes in a strain, (iii) cluster moderately related isolates and (iv) identify completely unrelated isolates. These levels of resolution are diagrammed in relation to evolutionary time in Fig. 1. Although several DNA fingerprinting methods fulfill requirements i and iv and some fulfill i, ii, and iv, several of the popular DNA fingerprinting do not fulfill requirement iii. The capacity to measure genetic distance in moderately related isolates may, in fact, be the most difficult requirement to meet. Unfortunately, no DNA fingerprinting method provides a definitive measure of genetic distance between two isolates, although some come far closer than others. As Tibayrenc has so poignantly articulated, “there is actually no means to fully ascertain the identity of two microbial genotypes but to sequence their entire genome” (391). Because different molecular markers may have different molecular clocks (i.e., the evolutionary speed at which they change), a good DNA fingerprinting method should be based on a number of molecular markers. The method should also be resistant to homoplasy. A DNA fingerprinting method should provide quantitative data that reflect genetic distance. One way to assess whether a DNA fingerprinting method fulfills this requirement is to compare the data generated by one method with those generated by a completely unrelated DNA fingerprinting method for the same set of test isolates (392, 395). The set of test isolates should include ones which are identical, ones which are highly related but nonidentical, and ones which are independent with no known relationships, including moderately and completely unrelated isolates (288). If the two methods identify the identical isolates and nonidentical but highly related isolates as such, generally cluster less closely related isolates in a similar fashion, and distinguish among completely unrelated isolates, then, in essence, the two methods have cross-verified each other for all of the levels of resolution described in Fig. 1. However, such verification can be achieved only for species with a predominantly clonal population structure (see the next section).

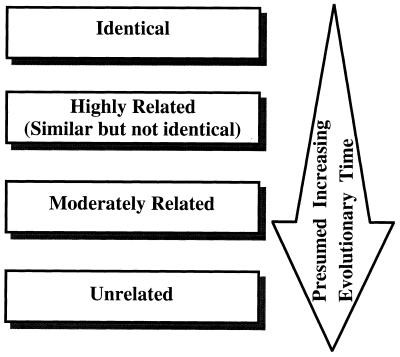

FIG. 1.

Levels of relatedness that must be resolved by DNA fingerprinting methods. The order of relatedness is presented, with relatedness in each category defined methodologically. “Identical” means that the DNA fingerprints of isolates are indistinguishable by most methods. “Highly Related” means that the DNA fingerprints are highly similar but nonidentical. Usually, differences between highly related isolates are due to hypervariable changes reflecting microevolution. “Moderately Related” means that isolates group in a dendrogram in a cluster defined by a similarity coefficient threshold well above the average similarity coefficient for a set of presumed unrelated isolates. “Unrelated” means that the SAB of isolates is near or below the average similarity coefficient for a set of presumed unrelated isolates.

Stability over Time for Some but Not All Epidemiological Questions

The data generated for a strain by a DNA fingerprinting method (e.g., a gel pattern) must be relatively stable over many generations. This requires that there be little recombination between the sequences selected for analysis and the populations within the species under analysis undergo primarily clonal reproduction. If panmixia (random gene exchange) occurs at high frequencies due to sexual mating and recombination, the results of epidemiological studies employing standard DNA fingerprinting methods are more difficult to interpret. Fortunately, many infectious fungi undergo recombination or gene exchange at extremely low frequencies (386). It has been concluded that C. albicans reproduction is primarily clonal (130, 291) and that standard DNA fingerprinting methods are applicable.

In addition to the stability resulting from clonal reproduction, a DNA fingerprinting method should assess primarily sequences that are not highly reorganizational (i.e., are reasonably stable over time). For instance, a complex DNA fingerprinting probe such as the 11-kb Ca3 probe of C. albicans (288, 315, 359) contains both repetitive sequences dispersed throughout the genome (e.g., the RPS repetitive element) and unique sequences represented at only one locus (152, 289). Because sequences in the genome containing clusters of full-length RPS units (73, 150) undergo frequent reorganization through duplication and deletion of full-length units (289), frequent changes occur in bands in the Ca3 hybridization pattern containing full-length RPS sequences. Bands containing full-length RPS elements represent, on average, one-fifth of the pattern generated by Ca3. Because the remaining four-fifths of the Ca3 hybridization pattern represent less variable sequences (3), these latter bands tend to stabilize the pattern. In contrast, a probe consisting entirely of RPS elements will generate a far less stable fingerprint pattern than will the complex Ca3 probe (289), and therefore the former will be far less effective in accurately clustering moderately related isolates. Therefore, both the full-length Ca3 probe and a restricted RPS probe can be used in studies assessing rapid change due to microevolution, but only the full-length Ca3 probe can be used in studies in which moderately related isolates must be analyzed.

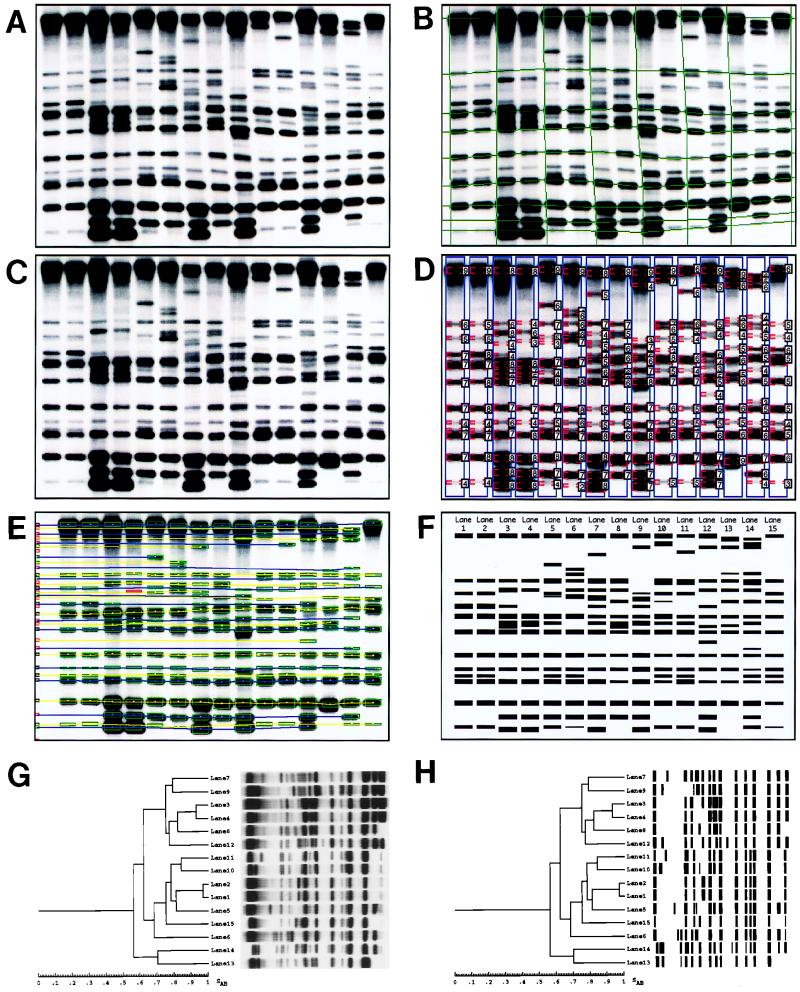

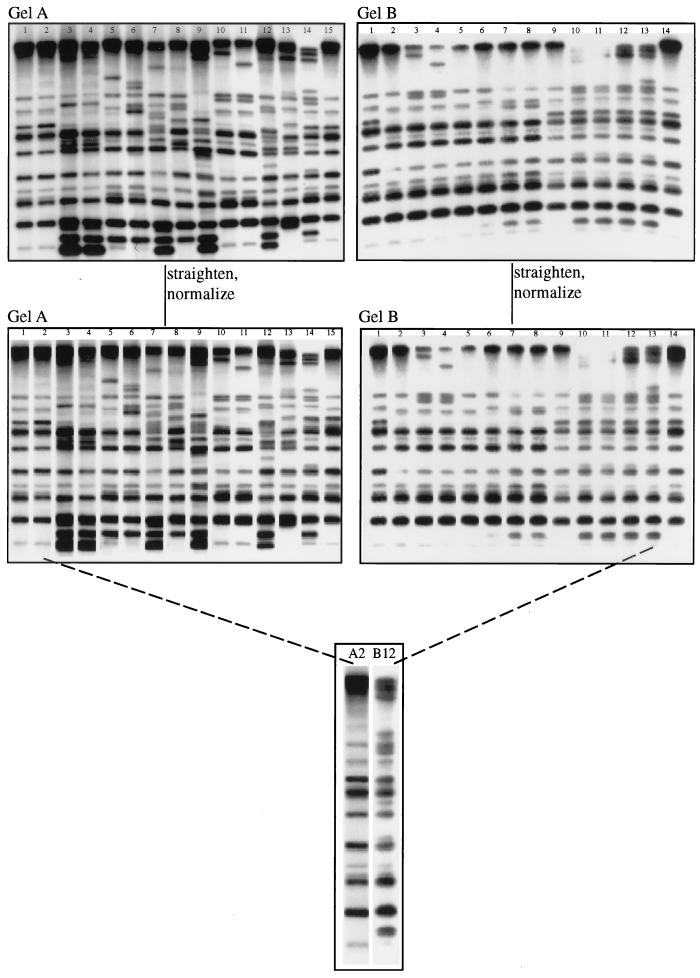

Amenability to Automated Computer-Assisted Analysis

Sophisticated computer-assisted systems have evolved for the automatic analysis and storage of DNA fingerprinting data in the form of banding patterns. These systems, which are discussed in more detail in a later section, automatically identify the lanes and bands in Southern blot patterns, density-scan the bands in a pattern, normalize patterns to universal standards, compute similarity coefficients for every pair of isolates, and generate phylogenetic trees (dendrograms). Computer programs have also evolved to store and analyze sequence data. The storage and rapid accessibility of data has emerged as a requirement for any fingerprinting method, since it provides a mechanism for retrospective analyses and for comparisons among studies.

THE MOST COMMON METHODS TO DNA FINGERPRINT THE INFECTIOUS FUNGI

Multilocus Enzyme Electrophoresis

Before considering the major DNA-based methods, we must consider MLEE and comparable methods that assess isozymes or allozymes, since they outperform many of the DNA-based methods at most levels of resolution. The power of MLEE is that if one is careful in selecting enzymes, one can discriminate among the gene products of different alleles for a number of loci. Thus, the method can assess codominant markers in diploids for each locus, a requirement for evolutionary biologists that is not achieved by a few of the popular DNA fingerprinting methods.

The MLEE method is straightforward. Cell extracts are separated by starch gel electrophoresis, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, or isoelectric focusing under native conditions, and the enzymes are visualized in the gels by specific enzyme-staining procedures. For haploids, one band is obtained, and for diploids, one or two are obtained. In some cases, the enzyme is active in multimeric forms, but in most of these cases the enzyme phenotypes can be assessed. To obtain complex data for computing a similarity coefficient between two isolates, several enzymes must be assessed. For instance, in a recent analysis by Pujol et al. (288) of C. albicans using MLEE, 21 enzymes were tested on 29 isolates. Thirteen exhibited variability and were therefore used in the analysis. In Fig. 2, an example is presented of starch gel electrophoresis patterns for mannose-6-phosphate isomerase and the two loci expressing hexokinase activity.

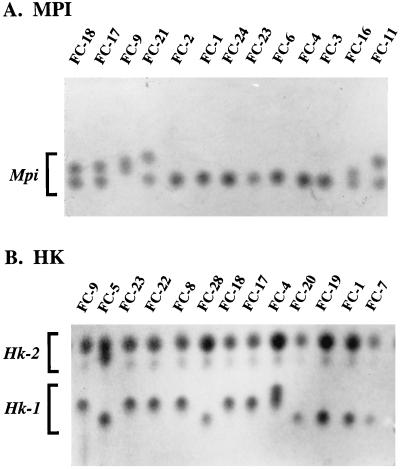

FIG. 2.

Examples of starch gel electrophoresis patterns of two enzymes, mannose-6-phosphate isomerase (MPI) (A) and hexokinase (HK) (B), used in an MLEE analysis of 13 C. albicans isolates. While the mannose-6-phosphate isomerase activity was expressed by a single locus, the hexokinase activity was expressed by two loci, Hk-1 and HK-2. Reproduced from reference 288 with permission of the publisher.

MLEE has been used to fingerprint C. albicans (8, 9, 17, 34, 35, 67, 91, 179, 180, 182, 234, 288, 291, 292, 301, 321), C. tropicalis (95, 180), Candida lusitaniae (220), Candida haemulonii (183), Candida parapsilosis (188), Candida guillermondii (325), Cryptococcus neoformans (28, 40, 41, 42, 43, 316), and Aspergillus fumigatus (307). This method was recently verified for C. albicans by a cluster analysis of a set of test isolates in which MLEE, randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) and Southern blot hybridization with fingerprinting probes were compared and parity was demonstrated (288). It was further demonstrated that if enough markers are used, MLEE will reveal microevolution within strains (288). There is little question that MLEE is an excellent method for DNA fingerprinting infectious fungi, since information is provided at all of the levels of resolution outlined in Fig. 1. The only drawback to this method is that it is relatively time-consuming, because one must combine the data from at least 10 enzymes that provide variability among isolates.

Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism without Hybridization

One of the first DNA fingerprinting methods used to assess strain relatedness in the infectious fungi is restriction fragment analysis, or restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) comparisons, without probe hybridization. RFLP has been applied to a variety of infectious fungi, including C. albicans (21, 63, 77, 78, 146, 161, 208, 262, 326, 346, 382, 384, 399, 410), C. parapsilosis (39, 267), Candida rugosa (92), Candida utilis (1), C. tropicalis (94), C. lusitaniae (163, 266), Cryptococcus neoformans (82), Histoplasma capsulatum (405) and A. fumigatus (55, 186). The method is straightforward. DNA is extracted from spheroplasts, digested with one or more endonucleases, and separated by electrophoresis in an agarose gel. The banding pattern of digested DNA is then visualized, usually by staining with ethidium bromide. Separation depends upon the percentage of agarose in the gel, the electrophoresis time, the voltage, and the particular endonuclease(s) employed. All of the experimental conditions must be determined empirically. The pattern is based on different fragment lengths determined by the restriction sites identified by the particular endonuclease(s) employed. Variations among strains can occur as a result of changes in restriction site sequences, secondary modification of restriction sites, deletion of recognition sites, or deletions and insertions in the sequences between recognition sites.

In bacteria, which have lower genomic complexity and contain less repetitive DNA than eukaryotes, the complex ethidium bromide-stained RFLP banding pattern can be more concise and the intensity of bands can be relatively equivalent. In spite of this, complex RFLPs have been used in only a limited number of DNA fingerprinting studies of bacteria (see, e.g., references 100, 132, 272, 273, and 380). In infectious fungi, the increased complexity of the genome increases the number of bands obtained with conventional endonucleases. This decreases the resolution of bands representing unique sequences. While the Escherichia coli genome contains approximately 3.0 × 107 bp (31), the C. albicans genome contains approximately 2 × 108 bp (304, 416), a 6.5-fold difference in size. The E. coli genome contains approximately 4,300 genes, while the estimate for C. albicans is at least 50% greater. Like all eukaryotic genomes, fungal genomes contain repetitive rRNA genes with relatively homologous sequences and intergenic regions. Eukaryotic ribosomal cistrons are usually clustered on one or two chromosomes. The C. albicans genome contains approximately 50 to 130 rDNA cistrons per diploid genome (149). Fungi also contain multiple copies of the mitochondrial genome (see, e.g., reference 373). rDNA sequences (326) and to a lesser extent mitochondrial DNA sequences (251, 427) represent the majority of intense bands in an RFLP pattern. A particularly good ethidium bromide-stained gel containing RFLP patterns of a number of C. albicans isolates is presented in Fig. 3A. The same gel after Southern blotting and hybridization with a radiolabeled probe of the C. albicans large-subunit, small-subunit, and 5S rDNAs is presented in Fig. 3B. Each lane of the ethidium bromide-stained gel (Fig. 3A) contains a complex background pattern of EcoRI fragments of various sizes and several intensely stained bands. While a subset of intensely stained bands was shown to represent mitochondrial DNA by hybridization (427), the majority of these bands were ribosomal, as is evident in a comparison of Fig. 3A and B. Variation is evident between isolates (Fig. 3A), but this variation is most readily resolved in the intensely hybridized rDNA bands (Fig. 3B). In contrast to the well-resolved low-intensity bands in the example in Fig. 3A, the low-intensity bands in most published RFLP patterns are poorly resolved. Therefore, comparisons of RFLP patterns rely in many cases only on differences between the most intense bands (i.e., the rDNA fragments). As will become clear in the next section, these fragments do not provide enough information to assess the relatedness of moderately related isolates. Even so, there is abundant evidence from the many RFLP studies of C. albicans (see, e.g., references 78, 262, 268, 326, and 346) that the method has been successful in identifying the same strain in independent isolates and in distinguishing among unrelated isolates. In a limited number of studies, the most intense bands have been manually digitized into databases for computer-assisted analysis (see, e.g., reference 78), but the general patterns are usually too dense and unresolved for automatic computer-assisted analyses. RFLP without a hybridization probe therefore represents a legitimate method for answering select epidemiological questions related to the infectious fungi, but it does not lend itself to studies in which cluster analyses of moderately related isolates is necessary. Therefore, RFLP is not well suited for large epidemiological studies. More importantly, the method has not been critically validated by comparison with another method for the levels of resolution listed in Fig. 1. It has not been critically tested by cluster analysis for how well it performs in grouping moderately related isolates, as have MLEE, RAPD and Southern blot hybridization with complex probes (288). It is faster, however, than all the alternative methods, including Southern blot hybridization, PCR-based methods, and sequencing methods.

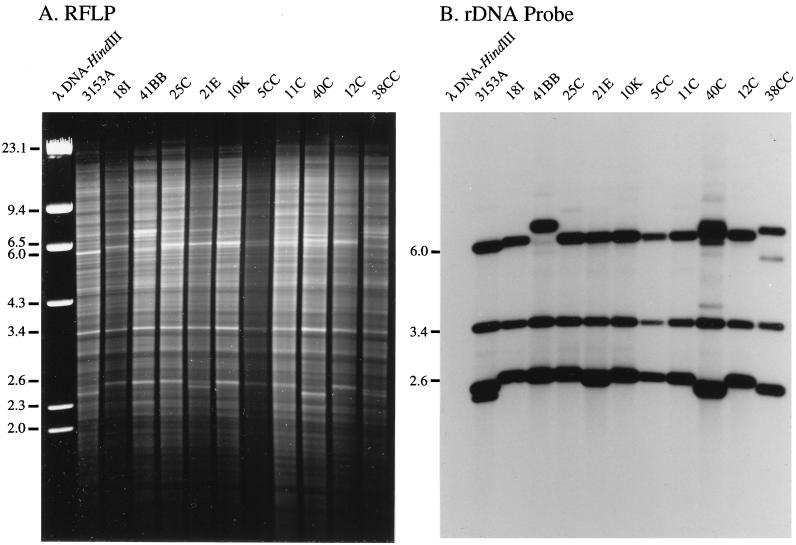

FIG. 3.

(A) RFLP patterns for 11 C. albicans isolates. In each case, whole-cell DNA was digested with EcoRI, electrophoresed in an agarose gel, and stained with ethidium bromide. The resolution of bands in this gel is unusually good. (B) Southern blot hybridization of the gel in panel A with a radioactive ribosomal probe containing 28S, 18S, and 5S rDNA. Note that the most intense bands in the ethidium bromide-stained pattern are ribosomal.

Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphisms with Hybridization Probes

A general RFLP pattern of eukaryotic cell DNA visualized by ethidium bromide staining is poorly resolved primarily because all restriction fragments are stained. Fragments within the pattern are in fact highly resolved, and a method for selectively visualizing a limited number of fragments will provide a more highly resolved fingerprint pattern for analysis. To visualize particular fragments in the pattern, one can probe a Southern blot of the RFLP gel with a radiolabeled or biotinylated DNA sequence that recognizes one or more fragments as a result of sequence homology, as in Fig. 3B. The stringency of hybridization can be controlled by varying the salt concentration and/or temperature (318). If the probe identifies a unique sequence (e.g., a single gene), the resulting pattern will be simple. If the unique sequence is relatively intact within a single restriction fragment in the gel, the probe will hybridize to only that fragment. In a haploid organism, the pattern will include only one band. In a diploid organism, such as C. albicans, the pattern will include one or two bands. If a site for the restriction enzyme employed is contained within the unique sequence, more than two bands are possible. Single-gene probes can discriminate among some isolates based upon allelic polymorphisms. However, because single-gene probes generate patterns with only one or two bands, they do not alone provide the level of data complexity necessary for measuring genetic distance. For instance, the URA5 gene was used to probe HaeII-digested DNA of 17 clinical isolates of C. neoformans (82). Isolates were separated into four types based on the size of URA5-containing fragments, but the resolution (i.e., the number of isolates distinguished genetically) was far below that obtained in the same study with the repetitive CNRE-1 DNA probe (82).

rDNA and mDNA probes.

The low resolution of a single-copy probe was realized quite early by researchers attempting to DNA fingerprint fungi. It was apparent that by using a number of single-copy probes, one could obtain data similar to those of MLEE, but the process would be labor-intensive. Therefore, probes that hybridized to repeat sequences dispersed throughout the genome were sought, since it was believed that either the repeat sequences or bordering sequences would vary among strains and that the resulting data from one Southern blot hybridization pattern would be complex enough to reflect genetic distance. Labeled C. albicans rDNA was used to probe Southern blots of C. albicans total-cell DNA, and although the method provided some resolution of unrelated strains (206, 217), the complexity of the hybridization pattern was not that much greater than that of patterns obtained with single-copy probes. Using rDNA as a probe, Stein et al. (370) were able to distinguish five patterns in 18 isolates of C. albicans. The rDNA hybridization patterns with EcoRI-digested DNA had a maximum of three bands (370, 415) and were comparable to those in Fig. 3B. One, two, or all three rDNA bands were common to apparently unrelated isolates at a relatively high frequency, suggesting homoplasy. rDNA and spacer regions of rDNA have also been tested as DNA fingerprinting probes in a number of infectious fungi other than C. albicans (see, e.g., references 62, 111, 119, 363, and 366), but in no case were complex enough patterns generated to be considered effective fingerprinting probes.

In bacteria, rDNA probes do generate relatively complex fingerprint patterns (49, 88, 138, 286) and have been the basis of relatively elegant automated ribotyping systems, such as the Riboprinter Microbial Characterization System marketed by Qualicon (Wilmington, Del.). Because ribosomal cistrons are dispersed throughout the single-chromosome genome of bacteria (237), endonuclease digests of bacterial DNA will contain multiple fragments of different sizes containing rDNA sequences. Thus, variability in fragment size will depend on differences in sequences bordering the rDNA cistrons as well as rDNA polymorphisms. This has resulted in high levels of resolution for discriminating among bacterial species and strains. In contrast, eukaryotic ribosomal cistrons are clustered (126, 135, 339, 406). Endonuclease digestion of these tandem repeats, which are separated by spacer sequences, generates fragments of similar relative sizes, resulting in a far simpler Southern blot hybridization pattern (i.e., a pattern with fewer bands) (Fig. 3B) and therefore low in resolution for strain discrimination (see, e.g., reference 320). Therefore, although effective in DNA fingerprinting bacteria, rDNA probes have not been that effective in DNA fingerprinting fungi.

The pattern obtained by probing a Southern blot of EcoRI-digested whole-cell DNA of C. albicans with mitochondrial DNA appears to be more complex than that obtained with a rDNA probe. Wills et al. (427) obtained five distinct bands, and the pattern varied among isolates sufficiently to suggest that Southern blot hybridization with a mitochondrial DNA probe would be effective in identifying the same strain in independent isolates and in distinguishing among unrelated strains of C. albicans (251). In an analysis of type I and type II Candida stellatoidea, a close relative of C. albicans, the hybridization patterns of type I isolates were identical but those of type II isolates varied (170). The patterns of some type II C. stellatoidea isolates were indistinguishable from those of some C. albicans isolates, demonstrating a lack of species specificity or low resolving power, if one accepts C. stellatoidea as an independent species (170). It is more likely that C. stellatoidea type II represents a subgroup of C. albicans, as has been suggested (172, 290). rDNA and mitochondrial DNA probes, therefore, have not been generally used in broad epidemiological studies of the infectious fungi, and neither method has been validated for the different levels of genetic resolution.

Repetitive and complex DNA probes for C. albicans.

To date, the most successful and popular hybridization probes for the fungi have been cloned fragments containing repetitive genomic sequences. Two such probes for C. albicans, 27A (327) and Ca3 (315, 359), were cloned at approximately the same time in the late 1980s and subsequently were found to be related (Fig. 4) (289). Because both contain sequences of the C. albicans repetitive element RPS and common non-RPS upstream sequences (Fig. 4) (73, 150), these probes hybridize to a majority of the same bands in a Southern blot. However, the two probes are not identical. 27A contains sequences downstream of the RPS cluster that hybridize to unique bands, while Ca3 contains sequences upstream of the RPS cluster that hybridize to unique bands (Fig. 4) (289). By comparison, Ca3 is a more complex probe than 27A, containing an additional repetitive sequence, the B sequence (Fig. 4). Ca3 generates a pattern that is, on average, more complex than that generated by 27A (C. Pujol, S. Joly, S. Lockhart, and D. R. Soll, unpublished observations). Furthermore, DNA fingerprinting with Ca3 fulfills the general requirements set forth in a previous section of this review for effective fingerprinting methods (288). Ca3 and 27A have been used in a number of epidemiological studies of C. albicans and the highly related species C. dubliniensis (see, e.g., references 6, 80, 137, 164, 168, 192, 196, 216, 218, 227, 246, 265, 271, 297, 310, 315, 327, 328, 329, 330, 332, 334–336, 352, 357, 358, 359, 374, 377, and 419).

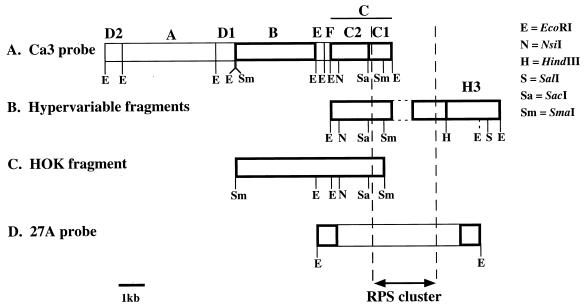

FIG. 4.

Physical maps of the complex DNA fingerprinting probe Ca3 (3, 192, 290), the HOK fragment (76), hypervariable fragments of isolates that hybridize to Ca3 (290), and an RPS cluster (150) of C. albicans. Known DNA sequences are represented by boxes with thick walls. Relative positions are assigned by DNA homology. RPS regions contain different numbers of full-length RPS units and are demarcated by dashed borders. The vertically dashed EcoRI site located to the right of the RPS region of the hypervariable fragments was observed in only one fragment (290). Reproduced from reference 76 with permission of the publisher.

The logic and methods used to clone and characterize 27A and Ca3 have also been used to develop similar complex probes for other infectious fungi, including A. fumigatus (122), C. tropicalis (152), C. glabrata (194), C. dubliniensis (151), C. parapsilosis (L. Enger and D. R. Soll, unpublished data), and C. lusitaniae (S. R. Lockhart, A. Hill, M. Pfaller, and D. R. Soll, unpublished data). The logic behind using a complex probe is relatively straightforward. In a Southern blot of endonuclease-digested genomic DNA, such a probe will hybridize to repetitive sequences dispersed throughout the genome, thus identifying variability among isolates at a variety of dispersed loci. It will also hybridize to additional sequences that are less variable, including sequences that vary as a result of allelic polymorphisms. Finally, it will hybridize to some hypervariable sequences, revealing microevolutionary changes within a strain. The virtue of the complex probe is that all this information is provided by a single Southern blot hybridization pattern. A complex probe should generate a pattern complex enough to provide an accurate and sensitive measure that reflects the relatedness of isolates. The major portion of the pattern it generates must be relatively stable over time for a particular strain. In addition, the probe should contain one or more sequences that hybridize to monomorphic fragments (i.e., fragments that exhibit the same size in all or most strains within a species). Monomorphic bands will facilitate normalization to a universal standard for computer-assisted storage for subsequent retrospective and comparative studies (see below).

Cloning complex DNA probes.

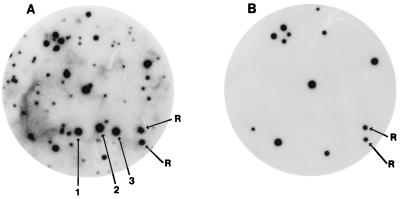

To clone complex DNA fingerprinting probes, genomic DNA is first prepared from spheroplasts, being careful not to shear the DNA unnecessarily. Contaminating RNA is digested with RNaseA. The genomic DNA is then incubated with a selected endonuclease (e.g., Sau3AI), aliquots are removed at short time intervals, and the reaction is stopped. The DNA of each sample is electrophoresed, and the time at which the majority of DNA falls in the size range of 10 to 20 kb is noted. The reaction is then scaled up. Fractions in the 10- to 20-kb range are ligated to lambda arms, packaged, titrated, and amplified. This library is then screened with radiolabeled genomic DNA for fragments that harbor at least one repetitive sequence. This can be accomplished either by limiting the time of hybridization or by limiting the concentration of probe. One can simultaneously screen duplicate blots for fragments that contain ribosomal sequences. In the blot probed with genomic DNA, intensely hybridizing clones that appear as dark dots in the autoradiogram (Fig. 5A) represent putative repetitive DNA inserts. Those dark dots with no correlates in the duplicate blot probed with rDNA (Fig. 5B) represent putative complex probes.

FIG. 5.

Hybridization screen used to select genomic clones of A. fumigatus that contained repetitive sequences that were nonribosomal. A genomic library was blotted on duplicate filters and hybridized with either radiolabeled genomic DNA (A) or a radiolabeled ribosomal probe (B). R, clones containing ribosomal DNA sequences; 1, 2, 3, potential complex probes containing repetitive sequences but devoid of ribosomal sequences. Reproduced from reference 123 with permission of the publisher.

When this method was recently applied to C. glabrata, seven clones were isolated that generated both unique and common bands when used to probe Southern blots of EcoRI-digested DNA of a set of test isolates (194). In all cases, the patterns appeared complex enough to compute meaningful similarity coefficients between pairs of isolates (194). However, the seven probes generated patterns for the same strain of C. glabrata with different degrees of band similarity. They also cross-hybridized, suggesting that they contained common sequences. One of these probes, Cg6, was tested for its capacity to discriminate among unrelated isolates, identify the same strain in different isolates, and identify microevolution within an infecting population (194). The effectiveness of Cg6 at the different levels of genetic relatedness (Fig. 1) was assessed by comparing it to the RAPD method in a cluster analysis (194). The two unrelated methods proved similar in identifying the same strain in different samples, distinguishing among unrelated isolates and clustering moderately related isolates into similar groups. In applying the same type of screen to C. tropicalis (152), 10 clones were isolated that generated complex banding patterns that varied among unrelated isolates. In these 10 clones, two general patterns emerged, suggesting that the probes could be separated into two groups, each containing a distinct family of repetitive elements. This was supported by the absence of cross-hybridization between probes from the two groups (152). Again, the effectiveness of the C. tropicalis probes Ct14 and Ct3, representing the two respective groups, was demonstrated through cross-comparison of their capacity to discriminate among unrelated isolates, identify the same strain in different isolates and cluster moderately related isolates (152).

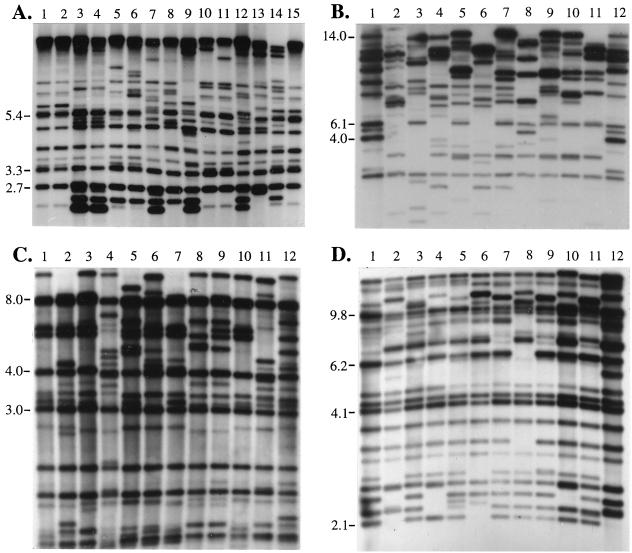

In Fig. 6A through D, examples are presented of the DNA fingerprint patterns generated by the species-specific complex DNA probes Ca3 for C. albicans (192, 315, 332, 359), Ct14 for C. tropicalis (152), Cg6 for C. glabrata (194), and Cd25-1 for C. dubliniensis (151), respectively. Each probe hybridized to fragments of different molecular sizes, and each hybridized to one or more monomorphic bands. The major bands are more distinct than ethidium bromide-stained patterns of similar EcoRI-digested and electrophoretically separated genomic DNA (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 6.

Examples of Southern blot hybridization patterns generated with the complex probes Ca3 of C. albicans (A), Ct14 of C. tropicalis (B), Cg6 of C. glabrata (C), and Cd25-1 of C. dubliniensis (D).

Characterizing complex DNA probes.

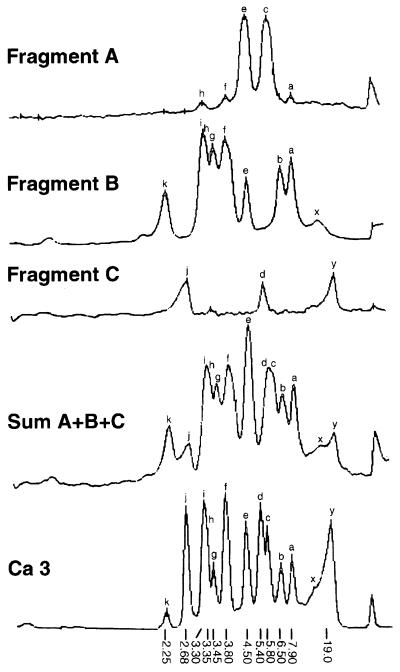

Once a complex probe is cloned, it should be physically mapped, analyzed for genomic distribution, and characterized for resolution. Since the 27A and Ca3 probes of C. albicans represent the most carefully characterized complex probes used to DNA fingerprint the infectious fungi, their characterization will be reviewed in some detail. Scherer and Stevens (327) first demonstrated that the 6.7-kb probe 27A, which was cloned from C. albicans strain 616, a fresh clinical isolate, contained a repeat sequence dispersed throughout the genome. They analyzed two clones from a partial Sau3A digest of genomic DNA that hybridized to the 27A probe and demonstrated that 27A and the two clones contained a common sequence (327), subsequently identified by Iwagushi et al. (150) to be the RPS repetitive element (Fig. 4). The 11-kb probe Ca3, first referred to as JH3 in an article on phenotypic switching in vaginitis isolates (359), was subsequently renamed Ca3 (360). Ca3 was cloned from laboratory strain 3153A and was shown to be dispersed on seven of the eight chromosomes of C. albicans (315). Anderson et al. (3) subsequently digested the Ca3 probe with EcoRI and obtained seven fragments, which, in descending order of size, were labeled A, B, C, D1, D2, E, and F (Fig. 4). The fragments were subsequently mapped in the 5′-to-3′ order (289) (Fig. 4). When EcoRI-digested DNA of C. albicans strain 3153A was probed with fragments A (∼4.2 kb), B (∼3.0 kb), and C (∼2.9 kb), three distinct patterns were obtained which, when combined, accounted for all of the bands obtained when the entire Ca3 probe was employed (Fig. 7). Fragment A generated three different hybridization patterns when used to probe Southern blots of EcoRI-digested DNA of a set of C. albicans isolates, the first consisting of one band at ∼5.8 kb, the second consisting of one band at ∼4.5 kb, and the third consisting of two bands at ∼5.8 and ∼4.5 kb. Thus, fragment A identified a single unique-copy gene, and these three patterns represented allelic variations of a single gene locus. Fragment B generated a pattern which included over half of the bands in the complete Ca3 pattern. The majority of B-pattern bands were polymorphic and represented most of the moderately variable bands necessary for cluster analyses used to demonstrate parity with MLEE and RAPD analysis (288). Fragment C generated patterns that included the highly variable high-molecular-weight bands that have proven valuable in assessing microevolution within an infecting strain (see, e.g., references 192, 196, 289, 330, and 336).

FIG. 7.

Pixel density scans of the Southern blot hybridization patterns generated with EcoRI fragments A, B, and C (Fig. 4) of the Ca3 probe and EcoRI-digested DNA of C. albicans strain 3153A. Note that the summed patterns of fragments A, B, and C (A+B+C) identify all of the major bands in the Ca3 pattern. Reproduced from reference 3 with permission of the publisher.

To determine the genomic distribution of sequences hybridizing to the three major fragments A, B, and C, Southern blots of electrophoretically separated C. albicans chromosomes were probed with the three fragments (3). Seven distinct chromosomal bands of C. albicans strain 3153A were separated by transverse alternating-field electrophoresis (TAFE) and numbered in descending order of size. Since C. albicans contains eight chromosomes (420), there was overlap in at least one position. The entire Ca3 probe hybridized strongly to bands 1, 3, 5, 6, and 7. Subfragment A hybridized strongly to band 7 and weakly to bands 1 and 3. Subfragment B hybridized strongly to bands 5 and 7, and weakly to band 6. Subfragment C hybridized strongly to bands 1, 3, and 6 and weakly to bands 5 and 7. These results demonstrated that both subfragments B and C contained sequences that were dispersed on more than one chromosome and that subfragment C, which contained RPS sequences, was more highly dispersed than was subfragment B.

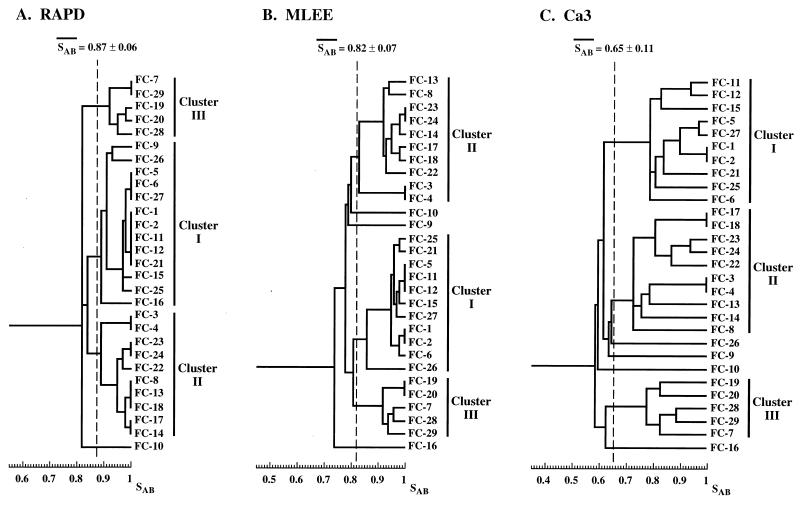

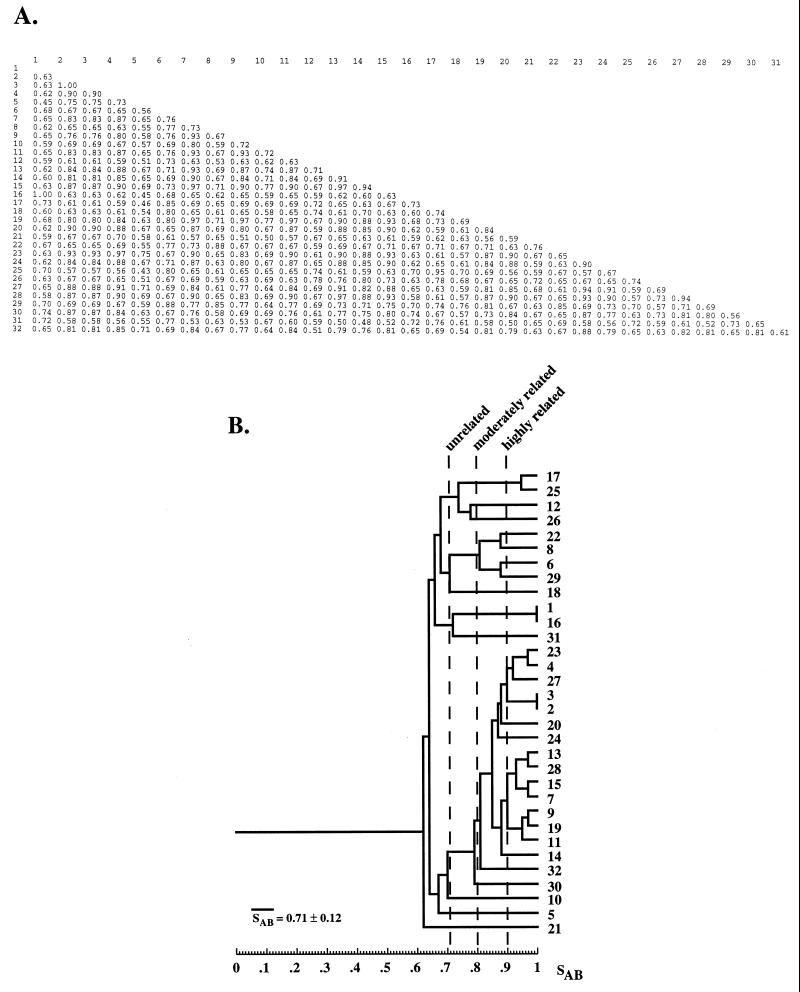

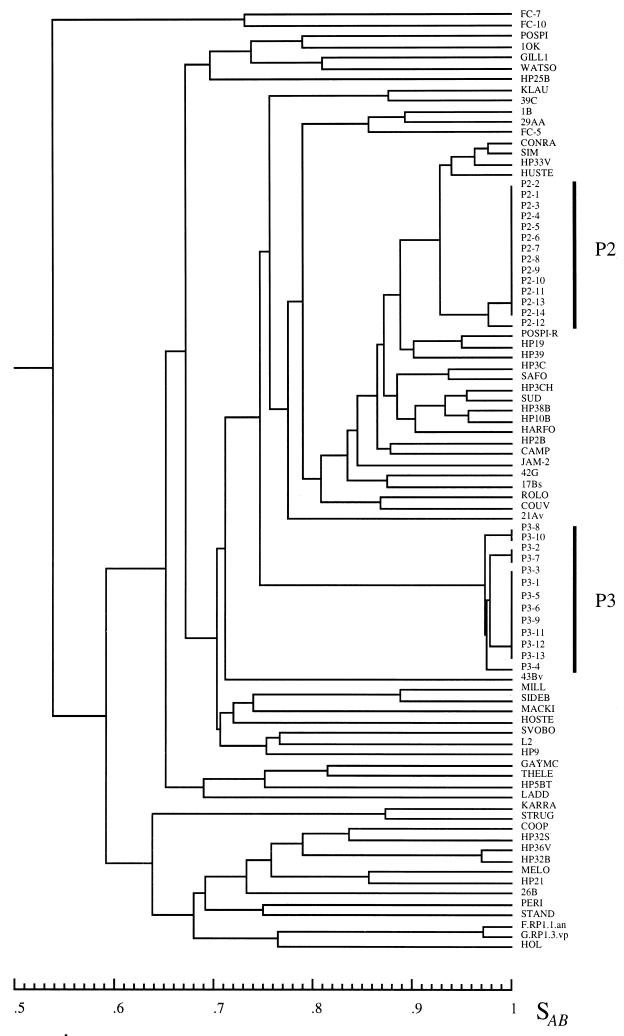

The physical relationships between the Ca3 probe (315), the large EcoRI genomic fragments to which the C fragment of Ca3 hybridizes (3, 289), the 27A probe (327), the recently characterized related HOK fragment (76), and the RPS element (73, 150) were recently determined (74, 76, 287, 289). A comparison of the physical maps is presented in Fig. 4. The three probes Ca3, 27A, and HOK all contain sequences of the C. albicans RPS element and the upstream C2 border of the RPS cluster. Therefore, all three identify a set of common bands in a Southern blot of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA. If the RPS element alone is used as a fingerprinting probe, the pattern is similar to that obtained with the C fragment of the Ca3 probe (150, 289). Although such a pattern is useful in assessing microevolution based on the hypervariability of full-length RPS sequences located in tandem at particular sites in the genome (289), its usefulness as a DNA fingerprinting probe falls short in clustering isolates that are not highly related (289). The problem of using a probe that contains primarily a repetitive dispersed genomic element was recently demonstrated in C. albicans. Lasker et al. (175) cloned the species-specific repetitive element CARE-2 from C. albicans genomic DNA. CARE-2 is a 1.06-kb sequence represented 10 to 14 times in the haploid C. albicans genome (175). It is dispersed on all chromosomes, and Southern blot hybridization demonstrated different copy numbers on different chromosomes (175). When Southern blots of EcoRI-digested DNA of a variety of isolates were probed with labeled CARE-2, complex hybridization patterns were generated that contained approximately the same number of bands as Southern blots probed with Ca3, but in contrast to Ca3, every band in the CARE-2 pattern was variable (288). CARE-2 distinguished unrelated isolates and identified the same strain in independent isolates. However, while the MLEE, RAPD, and Ca3 fingerprinting methods clustered the collection of isolates into three groups in a highly similar fashion (Fig. 8), two of the three groups fragmented into unrelated, smaller groups in the CARE-2 dendrogram (288). Therefore, because CARE-2 identifies only hypervariable fragments, it is far less effective in clustering moderately related isolates.

FIG. 8.

Dendrograms for a set of 29 isolates of C. albicans DNA fingerprinted by RAPD (A), MLEE (B), and Ca3 (C). Reproduced from reference 288 with permission of the publisher.

The results with CARE-2 (288) point to a common misconception regarding a useful DNA fingerprinting probe. There is a tendency to want to reduce a complex DNA fingerprinting probe to a single repeat element, as in the case of reducing Ca3 to the RPS element, based upon the misinformed notion that the more variable a pattern is, the better it will serve in DNA fingerprinting strains. When the bands in the Ca3 pattern were individually analyzed for variability, subsets identified by the subfragments exhibited hypervariability, moderate variability, low variability, and no variability. This combination strengthens the probe, such that the several levels of resolution we have proposed for an effective DNA fingerprinting method are attained (Fig. 1). Reducing Ca3 to RPS results in a probe useful primarily in studies of strain microevolution (289; Pujol et al., unpublished). Therefore, it is a misconception to strive for a probe composed exclusively of a repetitive element, and it is a misnomer to refer to a complex probe as a repetitive probe.

Repetitive and complex probes for fungi other than C. albicans.

As noted, complex species-specific probes have been cloned using the above general method for a variety of infectious fungi (122, 151, 152, 193, 194, 315, 327, 359; L. Enger, S. Joly, C. Pujol, and D. R. Soll, unpublished data). Both the patterns generated by these probes and the variability these probes identify among independent isolates (Fig. 6) suggest that future characterization of the non-C. albicans probes will reveal combinations of unique and repetitive elements similar to those contained in the complex C. albicans probe Ca3 (3, 289). A variety of other probes have been developed for C. albicans over the past several years that might be useful for DNA fingerprinting studies. Wilkinson et al. (422) first used poly(G-T) as a Southern blot hybridization probe and demonstrated variation among C. albicans isolates and differences between C. albicans and C. glabrata. Noting in 1993 that there were no good, accessible probes for Candida species other than for C. albicans, Sullivan et al. tested five oligonucleotides, (GGAT)4, (GGTG)5, (GATA)4, (GACA)4 and (GT)8, on a variety of Candida species and selected (CT)8 as the most effective for strain discrimination based on pattern complexity and variability (374). These sequences, which identify microsatellite regions, must still be characterized to determine whether they will serve as effective fingerprinting systems. Thrash-Bingham and Gorman (390) cloned two repetitive sequences, the 0.2-kb Rel-1 and the 2.8-kb Rel-2 sequences. Rel-2 belongs to the same repeat family as CARE-2. One subcloned fragment of Rel-2 that included bp 1478 to 2787 generated a complex pattern, but neither Rel-1 nor Rel-2 was characterized further for their potential use in DNA fingerprinting. Carlotti et al. (62) cloned the probe CkF1,2, which included the 3′ end of the large-subunit rRNA gene and the repeat sequence CKRS-1, from Candida krusei. Banding patterns appeared laddered, suggesting tandem deletion and duplication of the 165-bp kre element. The fingerprint pattern of CkF1,2, however, was not complex enough to be used to assess the relatedness of moderately related isolates in cluster analyses, and the probe has not been validated for fingerprinting. Such a probe, however, should be effective in assessing microevolution in infecting populations of C. krusei.

Probes containing repeat sequences have also been used to discriminate among strains of Cryptococcus neoformans. Spitzer and Spitzer (364) cloned CNRE-1, which hybridized to seven C. neoformans chromosomes and to 12 bands of a Southern blot of SstI-digested DNA of strain ATCC 6352. However, CNRE-1 generated far fewer bands and with far less intensity when hybridized to SstI-digested DNA of strain ATCC 28958 (171). This difference in hybridization appears to reflect genetic differences between serotypes A and D of C. neoformans. In addition, CNRE-1 exhibited only weak hybridization to serotype C strains. CNRE-1 fingerprinting was evaluated by comparing its discriminatory capacity to that of URA5 gene sequences (117). Groupings of URA5 alleles by parsimony analysis coincided with CNRE-1 groupings. These results suggested little genetic exchange between groups within a single geographical locale. A second DNA probe, the linear autonomous plasmid UT-4p, was used by Varma and Kwon-Chung to fingerprint C. neoformans (397). UT-4p generated hybridization patterns specific to the different serotypes of C. neoformans and showed minor variation among isolates within each group. The UT-4p pattern was stable in strains serially subcultured and identified the same strain in different isolates (397). As with CNRE-1 fingerprinting, UT-4p fingerprinting has also been used in a limited number of epidemiological studies (102). However, neither CNRE-1 nor UT-4p has been sufficiently characterized for the levels of resolution set forth in Fig. 1.

Several fingerprinting probes have been developed for Aspergillus flavus. pAF28 represents a 6.2-kb partial EcoRI digestion fragment that is species specific and generates a complex Southern blot hybridization pattern (214). This probe effectively discriminated among unrelated isolates. Repetitive sequences derived from Aspergillus nidulans and Neurospora crassa have also been used as probes for A. flavus, A. parasiticus, and A. nomius (230). Using the strategy employed to clone Ca3, several fingerprinting probes, including 3.11, 3.19, and 3.9, were developed for A. fumigatus (122). By limited cluster analysis, the three probes grouped the majority of moderately related A. fumigatus isolates in a similar fashion. These probes were subsequently demonstrated to be quite effective in the analysis of nosocomial infections (see, e.g., reference 124). Other probes have also been developed for Histoplasma capsulatum. rDNA and mitochondrial DNA probes have been used (363), but, again, they have not evolved for general use because of problems of resolution. One probe, yps-3, which hybridizes to yeast-phase-specific mRNAs of H. capsulatum (159), was subsequently used as a fingerprinting probe (158). yps-3 identified polymorphic differences between strains but generated only a very limited pattern of one or two bands. Therefore, yps-3 does not provide sufficiently complex data to be considered an effective fingerprinting probe.

In summary, complex DNA probes can be the basis for extremely effective DNA fingerprinting methods. Probes that generate patterns of only a few bands, however, do not provide enough complexity, and probes that contain exclusively a dispersed repetitive element may identify sequences too hypervariable for clustering moderately related isolates. The latter probes may, however, be very effective in studies of microevolution or in studies in which strains must be identified simply as related or unrelated. In some cases, while one probe may be more effective in clustering moderately related isolates, another may be more effective in identifying microevolutionary changes. In such cases, both probes can be used and the data can be combined, as has been suggested for the C. tropicalis probes Ct14 and Ct3 (152).

Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA and Related PCR-Based Fingerprinting Methods

Although a variety of PCR-based strategies have been developed for DNA fingerprinting purposes (59), RAPD (59, 413, 423) has evolved as the most popular method for DNA fingerprinting the infectious fungi. Using random primers of approximately 10 bases, amplicons throughout the genome are targeted and amplified. Amplified products are separated on an agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. When a single random oligonucleotide primer is used in a reaction, it hybridizes to homologous sequences in the genome. If the primer hybridizes to sequences on alternative DNA strands within roughly 3 kb, the DNA region between the two hybridization sites will be amplified using Taq polymerase. In the first reaction on each strand, a sequence is replicated by the DNA polymerase beginning at the site of hybridization and extending beyond the point at which there is a cognate sequence on the opposite strand. However, in the second reaction, the primer finds the homologous site within the first amplified strand and the replication reaction extends the second strand to the terminus of the sequence, which is the homologous sequence on the opposite strand. This second reaction produces the first amplified sequences equal in length to the targeted amplicon. In the amplification reactions that follow, primers continue to promote exclusively the synthesis of fragments of the amplicon sequence.

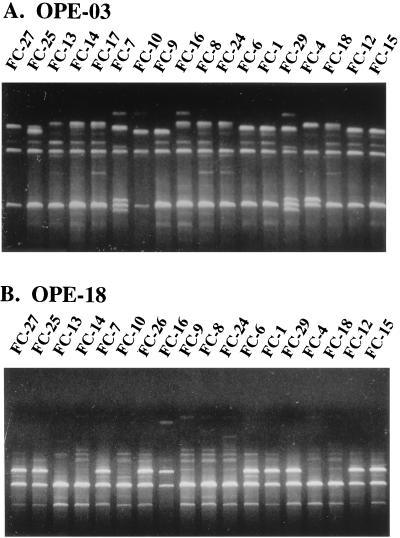

In the development of a RAPD DNA fingerprinting system for a particular species, a number of oligonucleotide primers must be tested, and those that provide the best variability among independent isolates are selected. Although a single primer can generate a relatively complex pattern that varies among isolates, in most cases a single primer provides one to three intense bands that may differ among isolates. Therefore, one must usually select a number of primers, run each independently for each test isolate, and combine the information. This strategy is illustrated by the work of Pujol et al. (288), who tested 40 random primers (each 10 bases in length) on a limited number of C. albicans test isolates; 8 were selected that provided maximum variability. Only reproducible, intense bands in each pattern were used in the analysis. Each primer generated one to six intense bands. Examples of RAPD patterns with the primers OPE-3 and OPE-18 are presented in Fig. 9. The combined number of intense bands generated by eight primers selected by Pujol et al. for variability among isolates was 31, but only 16 were polymorphic for the 29 test isolates. When dendrograms were generated based on similarity coefficients computed from the combined data obtained with the eight probes, clustering of the 29 test isolates was similar to that obtained using either MLEE or Southern blot hybridization with the Ca3 probe. Parity has also been demonstrated between the RAPD method and Southern blot hybridization with complex probes of C. glabrata (194). The results of Pujol et al. (288) suggest that the RAPD method of fingerprinting attains the same data complexity and resolving power as complex DNA fingerprinting probes and MLEE. These findings are of no surprise. Complex probes such as Ca3 identify a number of homologous sequences throughout the genome homologous to different portions of the probe, and MLEE accumulates allelic data for a number of genes. A combination of random oligonucleotide primers provides similar data. Pujol et al. (288) demonstrated that RAPD, MLEE, and Ca3 fingerprinting of C. albicans not only clustered moderately related isolates in a similar fashion but also afforded similar levels of resolution of microevolution within a clonal population. However, it should be noted that the microevolutionary changes identified by the three methods were independent and that the methods therefore did not identify changes in the same highly related isolates. Rather, the methods measured similar frequencies of variants within the same strain. Recently, the RAPD method was used to analyze the level of homology among fragments amplified by the same primers in closely related species of the sunflower (303). A total of 91% of comigrating fragments exhibited homology. This represents a high level of homology, given that the test was interspecific. Thormann et al. (388) further demonstrated that RAPD fragments of cruciferous plant species with similar molecular weights were identical, but they were not always identical between species. Together, these results demonstrate the efficacy of the RAPD method in assessing genetic relatedness. Similar tests have not yet been reported for the fungi, although one can assume that the outcomes will be similar.

FIG. 9.

Examples of RAPD patterns with the primers OPE-3 (A) and OPE-18 (B) for different C. albicans isolates. Reproduced from reference 288 with permission of the publisher.

The RAPD method of DNA fingerprinting has become quite popular for all infectious fungi and has been successfully applied to C. albicans (see, e.g., references 22, 36, 37, 77, 83, 86, 131, 140, 141, 181, 223, 288, 306, 309, 369, and 393), C. dubliniensis (79), C. parapsilosis (199), C. lusitaniae (163, 181), C. tropicalis (181, 187), C. glabrata (195, 181, 337, 387), C. krusei (437), C. famata (437), C. rugosa, (437), A. fumigatus (5, 11, 178, 187, 200, 202, 228, 296), A. flavus (51), Cryptococcus neoformans (32, 33, 41, 68, 71, 72, 117, 197, 282, 311, 361, 362, 375), H. capsulatum (160, 431), and Blastomyces dermatitidis (435). However, several caveats of the procedure must be kept in mind. First, there is the problem of reproducibility not only among laboratories but within a laboratory over time, and this single problem, although not insurmountable, makes the development of a common database difficult. Virtually every methodological aspect of PCR can affect reproducibility. Artifactual variation can occur as a result of small differences in the primer-to-template-concentration ratio, the temperatures during the amplification reaction, and the concentration of magnesium in the reaction mixture (104). Changes in these parameters affect most notably the presence of low-intensity bands but can also affect the position and intensity of high-intensity bands. This may explain the general result that even in the same laboratory, using the same thermocycler and reagents, variation occurs in the low-intensity bands (see, e.g., reference 215). Even more disturbing are reports of variation due to the Taq enzyme source. Louden et al., who have used the RAPD methodology to fingerprint A. fumigatus isolates in a number of studies (202), reported that different lots of Taq polymerase resulted in great enough variability to generate what they termed “pseudoclusters” (201). Evidence was presented that one enzyme lot could not discriminate among isolates while the other could. Meunier and Grimont (222) reported artifactual variation due to the use of Taq DNA polymerase from different manufacturers. They also added the manufacturer of the thermocycler to the list of variables that could affect the RAPD pattern. The artifacts observed were primarily, but not exclusively, in low-intensity bands (222). It is therefore imperative that such factors be considered when comparing RAPD patterns from different laboratories. Such factors place constraints on the use of this technology in generating a global database.

One promising modification of RAPD is amplified fragment length polymorphism (408). This method selectively amplifies restriction fragments in a genomic DNA digest. Amplification is achieved by using the adapter and restriction sites for the annealing of primers, and fragment selection is achieved by adding selective bases to the 3′ end of the primers. By using stringent reaction conditions for primer annealing, the reliability of the method has been reported to be superior to that of the RAPD method, and careful selection of the restriction enzymes and selective nucleotides at the primer 3′ ends results in a complex fingerprint pattern in a sequencing gel with yeast DNA as template (408). This method may evolve into a superior DNA fingerprinting method, but at the time of this review there has been no meaningful development for the infectious fungi.

The PCR method can also be used to target specific sequences. Customized primers have been developed for the spacer regions between ribosomal cistrons, the spacer regions between tRNAs, and microsatellite sequences. Theoretically, the complexity of the information obtained with primers to these repetitive sequences should be similar to that using hybridization probes of the same sequences. Therefore, primers customized for ribosomal spacer sequences will most probably not provide great enough complexity. For microsatellites, primers can be designed outside of the regions (221), or primers like (GTG)5 can be used. In the former case, differences in size are due to insertions and deletions of the short tandem repeats of the microsatellite regions. For a given locus, these differences can be interpreted as alleles, but these regions may undergo recombination at extremely high frequencies and may therefore have their greatest value in the analysis of microevolution. In the case of primers like (GTG)5, the primers will amplify genomic fragments flanked by inversely oriented targeted motifs. This method, referred to as interrepeat PCR, should result in a higher level of reproducibility than RAPD because the annealing temperature is higher (19, 224).

Thanos et al. (387) compared the arbitrary 10-mer primer AP3, the primer T3B designed on the basis of the intergenic tRNA spacer region, and the primer (GTG)5 designed on the basis of a microsatellite sequence for their capacity to discriminate not only among Candida species but also among strains within a species. The discriminatory capacity of the arbitrary 10-mer primer was greater than that of the intergenic tRNA spacer primer (387). Although Thanos et al. (387) demonstrated that intergenic tRNA spacer sequences vary among species, variability among strains within a species did not appear to be great enough for clustering moderately related isolates. Microsatellite and minisatellite primers should be more effective, since these sequences are usually dispersed throughout the genome. However, as with repeat sequence probes, variability due to a high frequency of change in satellite DNA sequences may decrease the effectiveness of the method in clustering moderately related isolates. For C. albicans, repeat sequences targeted for amplification have included minisatellite and microsatellite sequences (90, 177, 333, 375), the CARE-2 element and the COM-21 element, a repeat element within the RPS1 repetitive element (298), repeat sequences found in prokaryotes and eukaryotes (395, 396), and rDNA (15, 376).