Abstract

Background

At present, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage (PTCD) are frequently used for reducing malignant obstructive jaundice (MOJ). However, it is controversial as to which method is superior in terms of efficacy and safety.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to compare the safety, feasibility, and clinical benefits of ERCP and PTCD in matched cases of MOJ.

Methods

The Web of Science, Cochrane, PubMed, and CNKI databases were searched systematically to identify studies published between January 2000 and December 2019, without language restrictions, that compared ERCP and PTCD in patients with MOJ. The primary outcome was the success rate for each procedure. The secondary outcomes were the technical success rate, serum total bilirubin level, length of hospital stay, hospital expense, complication rate, and survival. This meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.3.

Results

Sixteen studies met the inclusion criteria, including 1,143 cases of ERCP and 854 cases of PTCD. The analysis demonstrated that jaundice remission in PTCD was equal to that in ERCP (mean difference [MD], 1.19; 95% confidence interval [CI]: −0.56 to −2.93; p = 0.18). However, the length of hospital stay in the ERCP group was 3.03 days shorter than that in the PTCD group (MD, −2.41; 95% CI: −4.61 to −0.22; p = 0.03). ERCP had a lower rate of postoperative complications (odds ratio, 0.66; 95% CI: 0.42–1.05); however, the difference was not significant (p = 0.08). ERCP was also more cost-efficient (MD, −5.42; 95% CI: −5.52 to −5.32; p < 0.01). Further, we calculated the absolute mean of hospital stay (ERCP:PTCD = 8.73:12.95 days), hospital expenses (ERCP:PTCD = 5,104.13:5,866.75 RMB), and postoperative complications (ERCP:PTCD = 11.2%:9.1%) in both groups.

Conclusion

For remission of MOJ, PTCD and ERCP had similar clinical efficacy. Each method has its own strengths and weaknesses. Considering that ERCP had a lower rate of postoperative complications, shorter hospital stay, and higher cost efficiency, ERCP may be a superior initial treatment choice for MOJ.

Keywords: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, Percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage, Meta-analysis, Malignant obstructive jaundice

Introduction

Malignant obstructive jaundice (MOJ) is commonly associated with malignant disease, usually involving complete obstruction and a progressive course [1, 2, 3]. MOJ is often associated with pancreatic cancer, common bile duct stones, or hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Due to the delayed symptoms and difficulties preventing early diagnosis, an opportunity for radical surgery is unlikely. Therefore, conservative biliary drainage is a vital option for the treatment of MOJ. At present, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage (PTCD) are common clinical approaches [4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. To address this issue, we systematically compared the surgical success rate, clinical efficacy, and safety of these two techniques using the relevant domestic and foreign literature.

Methods

This study was designed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. We searched medical databases for articles using the term ERCP versus PTCD. This search strategy was designed and executed by an experienced information specialist and was reviewed by two authors (Yantao Fu and Liwei Pang).

Inclusion Criteria

1. Study design: randomized, controlled trials; retrospective cohort studies; and case-control studies

2. Interventions: ERCP or PTCD

3. Participants: patients with clinical manifestations, imaging features, and pathological diagnosis of MOJ

4. Language: no language restrictions

5. Type of article: studies published only as full text articles

6. Studies comparing ERCP with PTCD, involving at least 10 patients among all age groups, and reporting at least one of the primary or secondary outcomes

Exclusion Criteria

1. Non-comparable or non-human studies, review articles, editorials, letters, and case reports

2. Articles not reporting the outcomes of interest

Literature Search Strategy

A detailed literature search was performed using the following keywords: ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, PTCD, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage, malignant obstructive jaundice, and MOJ in the following online databases: Web of Science (217), Cochrane (123), PubMed (103), and CNKI (181) (last search date: January 1, 2020), without restriction with regard to region, publication type, or language. The search strategy applied to PubMed was as follows: ((“endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography” (Supplementary Concept)) OR ERCP) AND ((“percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage” (Supplementary Concept)) OR PTCD) AND (“malignant obstructive jaundice”). When similar reports describing the same population were published, the most recent or complete report was used. The research was conducted individually by Yantao Fu and Liwei Pang; subsequently, all authors compared their results. References from the articles were investigated manually. Any differences were resolved via consensus.

Data Extraction

The following data were extracted: author names, study design, number of patients, operation success rate, serum total bilirubin level (TBiL), and postoperative complications (e.g., acute pancreatitis, cholangitis, hemobilia, and hepatapostema).

Outcomes of Interest

Data were collected on all outcomes in a prestructured proforma as follows.

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was successful drainage tube placement and bile extraction for PTCD and endoscopic nasobiliary drainage and successful stent placement for endoscopic biliary stenting.

Secondary Outcomes

1. Technical success rate

2. Serum TBiL

3. Length of hospital stay

4. Hospital expense

5. Complications

6. Survival

Quality Assessment and Statistical Analysis

The studies were rated for the level of evidence provided according to the criteria of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine in Oxford, UK. The methodological quality was assessed using the modified Newcastle-Ottawa scale (Table 1) [9], consisting of three factors: patient selection, comparability of the study groups, and assessment of outcomes. A score of 0–9 (represented by stars) was allocated to each study, and observational studies achieving Z6 stars were considered to be of high quality. We used Review Manager 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, England) for all statistical analyses. Considering that patients were selected by different surgical teams and operated on at different centers, we chose the random-effects model to assess this heterogeneity; I2 values of >50% were considered significant. Dichotomous variables were analyzed using odds ratios, with p values <0.05 and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) not including a value of 1 supporting statistical significance. Continuous variables were analyzed using the weighted mean difference (MD). This study was performed according to the PRISMA guidelines [10].

Table 1.

Assessment of study quality based on the modified Newcastle-Ottawa scale

| Author | Is the case definition adequate? | Representativeness of the cases | Selection of controls | Definition of controls | Comparability of cases and controls on the basis of the design or analysis | Ascertainment of exposure | Same method of ascertainment for cases and controls | Non-Response rate | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Born et al. (2000) [11] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Virginia et al. (2002) [12] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Hiroyuki et al. (2007) [13] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Saluja et al. (2008) [14] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Kloek et al. (2010) [15] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Hiroshi et al. (2011) [16] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 |

|

| |||||||||

| Walter et al. (2013) [17] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Kim et al. (2015) [18] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Zhang et al. (2016) [19] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Jo et al. (2017) [20] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 |

|

| |||||||||

| Hongeun et al. (2018) [21] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

|

| |||||||||

| O'Brien et al. (2020) [22] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 8 |

|

| |||||||||

| Yuan et al. (2018) [23] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 5 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Che et al. (2019) [24] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Chi et al. (2019) [25] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 7 | |

|

| |||||||||

| Chai et al. (2019) [26] | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | ☆ | 6 | ||

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were examined using the Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Categorical variables were examined using the χ2 or Fisher's exact test as appropriate. All statistical tests were two-tailed. For all analyses, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

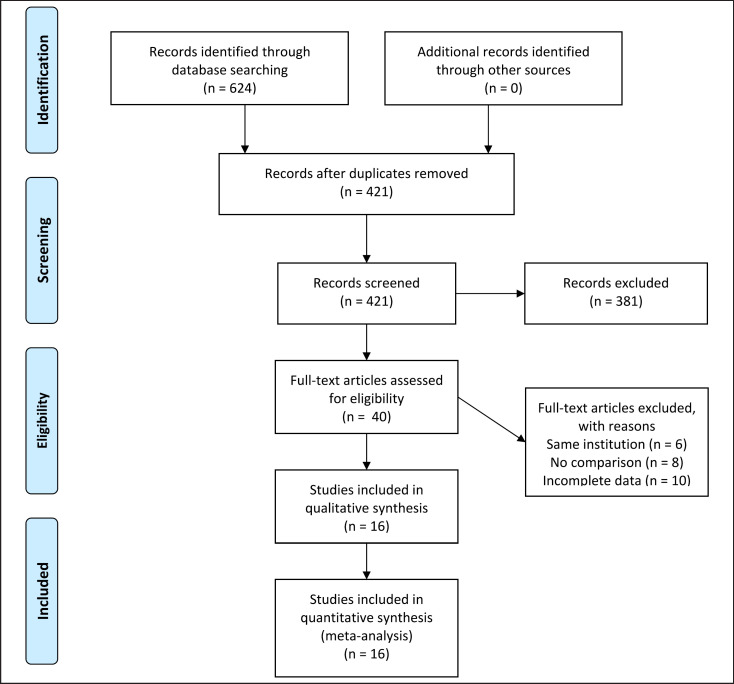

The literature search produced 624 related studies. No other eligible studies were found from other sources. Initially, 40 potentially meaningful articles were included for full-text analysis after reading their titles and abstracts. Of these, we excluded six articles that were from the same institution. Furthermore, eight papers were excluded because the data were not impactful and the authors could not provide information in detail. We excluded another ten studies that lacked comparative analysis. Finally, a total of 16 studies (5 in Chinese and 11 in English) representing 1,143 cases of ERCP and 854 cases of PTCD were included in the meta-analysis [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26]. Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA flow chart of the literature search strategies, and Tables 2 and 3 describe the included articles.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 2.

Basic characteristics of the included studies

| Author | Year | ERCP/PTCD | Study type | Study period | Institution | Bismuth-Corlette class (n) (hilar cholangiocarcinoma) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Born (Germany) [11] | 2000 | 20/39 | Retrospective study | 1992–1994 | Rechts der Isar Hospital, Germany | II-IV (59 patients) |

|

| ||||||

| Virginia (Spain) [12] | 2002 | 26/28 | RCT | 1996–1999 | Hospital Clinic Villarroel Barcelona, Spain | I (16 patients); II (10 patients); Ill (5); IV (1) |

|

| ||||||

| Hiroyuki (Japan) [13] | 2006 | 16/9 | Retrospective study | 1997–2005 | Teine Keijinkai Hospital, Japan | I (3 patients); II (3 patients); IIIa (2 patients); IIIb (2 patients); IV (17 patients) |

|

| ||||||

| Saluja (India) [14] | 2008 | 27/27 | RCT | NR | All India Institute of Medical Sciences | II-III (54 patients) |

|

| ||||||

| Kloek (The Netherlands) [15] | 2009 | 90/11 | Retrospective study | 2001–2008 | University of Amsterdam, Netherlands | I-II (25 patients); III-IV (76) |

|

| ||||||

| Hiroshi (Japan) [16] | 2010 | 80/48 | Retrospective study | 1999–2009 | Hokkaido University, Japan | I (19 patients); II (34 patients); IIIa (24 patients); IIIb (19 patients); IV (32 patients) |

|

| ||||||

| Walter (Canada) [17] | 2012 | 87/42 | Retrospective study | 1991–2011 | Michael's Hospital, Toronto, Canada | I-II (26 patients); III (53 patients); IV (45 patients) |

|

| ||||||

| Kim (Korea) [18] | 2015 | 44/62 | Retrospective study | 2000–2012 | Sungkyunkwan University, Korea | I (2 patients); II (16 patients); III (67 patients); IV (21 patients) |

|

| ||||||

| Zhang (China) [19] | 2016 | 76/64 | Retrospective study | 2010–2014 | People's Armed Police Corps Hospital, China | NR |

|

| ||||||

| Jo (Korea) [20] | 2016 | 55/43 | Retrospective study | 2005–2012 | Severance Hospital, Yonsei University, Korea | I (10 patients); II (11 patients); IIIa (29 patients); IIIb (11 patients); IV (23 patients) |

|

| ||||||

| Hongeun (Korea) [21] | 2017 | 335/234 | Retrospective study | 2000–2014 | Seoul National University Hospital, Korea | NR |

|

| ||||||

| O'Brien (America) [22] | 2018 | 69/18 | Retrospective study | 2006–2017 | University of Louisville, America | NR |

|

| ||||||

| Yuan (China) [23] | 2018 | 62/61 | Retrospective study | 2013–2017 | Zhumadian Hospital, China | NR |

|

| ||||||

| Che (China) [24] | 2019 | 45/45 | Retrospective study | 2016–2018 | Capital Medical University, China | NR |

|

| ||||||

| Chi (China) [25] | 2019 | 39/39 | Retrospective study | 2014–2017 | Chaoyang Hospital of Huainan, China | NR |

|

| ||||||

| Chai (China) [26] | 2019 | 72/84 | Retrospective study | 2012–2017 | The Second Hospital of Tianjin Medical University, China | I (8 patients); II (6 patients); III (14 patients) |

Table 3.

Description of included articles

| Author | Decrease of TBiL (mg/ dL) | Hospital stay (day) | Hospital expense ($) | Complications (%) | Technical success rate (%) | Conversion | Survival, month |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Born (Germany) [11] | 21.7±10.3/14.6±3.8 | − | − | 6 (30)/13 (33) | 80/82 | − | 4.5±3.0/6.0±4.0 |

|

| |||||||

| Virginia (Spain) [12] | 21.1±6.8/17.1±8.6 | 11.9±8.5/8.5±7.1 | 4,224±2275/4,970±2339 | 9 (35)/17 (61) | 58/75 | − | 4.8±3.7/2.0±0.8 |

|

| |||||||

| Hiroyuki (Japan) [13] | − | − | − | 1 (6)/2 (22) | 75/67 | 2/0 | − |

|

| |||||||

| Saluja (India) [14] | 11.5±10.5/11.9±10.7 | − | − | 14 (52)/5 (18) | 81/93 | − | 2.0±0.6/2.0±0.3 |

|

| |||||||

| Kloek (The Netherlands) [15] | 23.0±21.0/18.0±14.0 | − | − | 71 (78)/4 (36) | 81/100 | − | − |

|

| |||||||

| Hiroshi (Japan) [16] | 26.7±9.5/18.7±12.0 | − | − | 36 (45)/15 (31.3) | 80.0/79.2 | 32/2 | − |

|

| |||||||

| Walter (Canada) [17] | − | − | − | 23 (79)/11 (44) | 77/42 | 44/0 | − |

|

| |||||||

| Kim (Korea) [18] | 10.1±8.5/12.2±8.7 | 18.5±10.7/18.3±16.3 | − | 14 (22.6)/24 (54.5) | 56.8/58.1 | 17/4 | 21±11/19±10 |

|

| |||||||

| Zhang (China) [19] | 12.5±7.6/12.6±7.6 | 13.5±2.5/20.1±3.4 | 3,724±213.13/3,056±582.55 | 4 (5.26)/11 (17.19) | 92.1/93.7 | − | − |

|

| |||||||

| Jo (Korea) [20] | 9.5±6.7/8.3±6.3 | 27.4±17.5/26.8±17.9 | − | 20 (36)/12 (27.9) | 93.7/97.3 | 25/2 | 23.5±9.5/26±12 |

|

| |||||||

| Hongeun (Korea) [21] | − | 25.7±14.3/20.6±13.0 | − | 107 (38.2)/109 (46.4) | 82.1/88.5 | − | − |

|

| |||||||

| O'Brien (America) [22] | 15.2±7.1/15.5±9.9 | 6.0±5.0/6.0±4.0 | − | 8 (12)/5 (28) | 94/89 | 8/5 | − |

|

| |||||||

| Yuan (China) [23] | 9.7±6.8/12.5±7.9 | 3.5±2.6/19.9±4.0 | 3,098±284.2/3,609±326.8 | 3 (4.8)/14 (22.9) | 95.1/83.6 | − | − |

|

| |||||||

| Che (China) [24] | − | 12.5±3.9/18.8±4.3 | − | 3 (6.6)/12 (26.6) | 93.3/84.4 | − | 11.0±3.1/7.4±2.7 |

|

| |||||||

| Chi (China) [25] | 8.0±5.5/7.9±5.5 | 13.9±2.4/17.5±2.6 | − | 2 (5.1)/7 (17.9) | 94.8/97.4 | − | − |

|

| |||||||

| Chai (China) [26] | 8.3±6.9/8.2±7.0 | 13.5±4.0/19.1±4.3 | 6,811.6±659.1/7,295.7±870.0 | 4 (5.5)/18 (21.4) | 91.6/95.2 | − | 11.0±1.2/11.2±1.2 |

Meta-Analysis

Primary Outcome

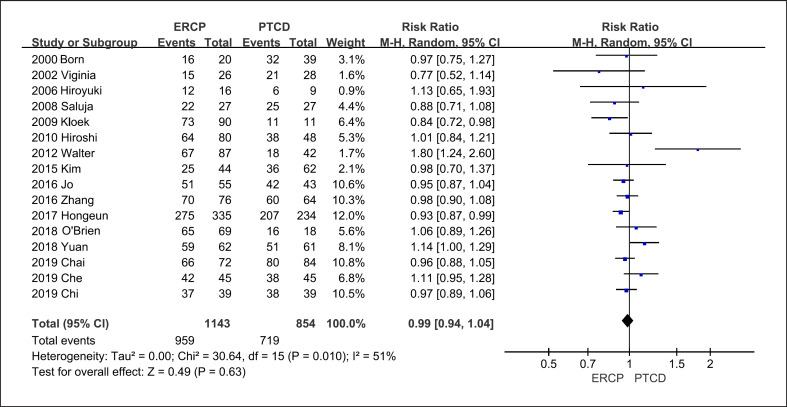

All 16 studies reported the success rates of the two procedures. Overall, ERCP was successful in 84.6% of patients and PTCD in 82.7% (Fig. 2). However, most articles in this meta-analysis represented retrospective and case-control studies; therefore, the success rates of these two procedures may have been overestimated.

Fig. 2.

Forest plots of the meta-analysis. Surgical success rate in studies on the two procedures.

Secondary Outcomes

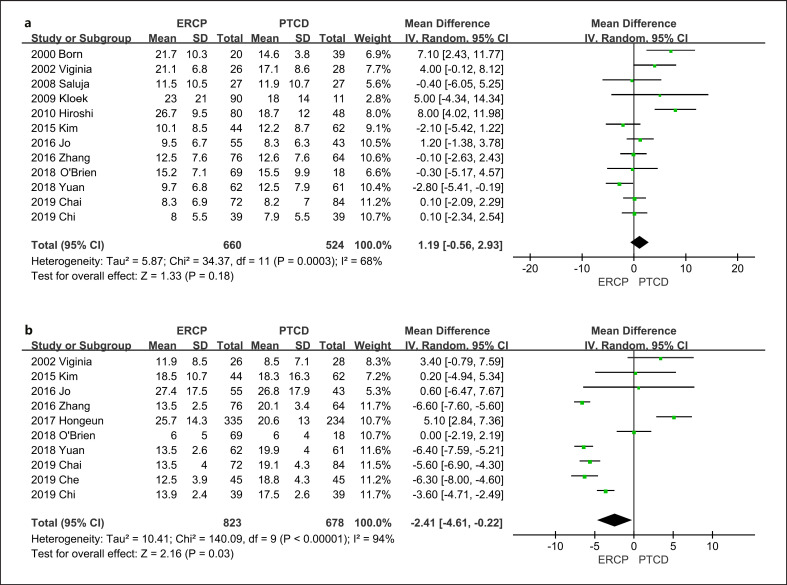

Decrease in TBiL: Twelve articles presented this outcome. The results demonstrated that jaundice remission in PTCD was equal to that in ERCP (MD, 1.19; 95% CI: −0.56–2.93; p = 0.18) (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Forest plots of the meta-analysis. a Decrease of TBiL. b Hospital stay.

Hospital stay: We identified 10 trials with relevant data. The length of hospital stay in the ERCP group was 3.03 days shorter than that in the PTCD group (MD, −2.41, 95% CI: −4.61 to −0.22; p = 0.03). The absolute mean value of hospital stay was ERCP:PTCD = 8.73:12.95 days (Fig. 3b).

Hospital expenses: Hospital charges were recorded in only five trials. ERCP was more cost-efficient (MD, −5.42; 95% CI: −5.52 to −5.32; p < 0.01), and the absolute mean value of hospital expenses was ERCP:PTCD = 5,104.13:5,866.75 RMB.

Postoperative complications: The incidence of postoperative complications was evaluated in all 16 studies. ERCP had a lower probability of postoperative complications (odds ratio, 0.66; 95% CI: 0.42 to 1.05; p = 0.08; ERCP:PTCD = 9.1%:11.2%), including bacterial infection, bile leakage, hemorrhage, and fever; however, but the difference was not significant (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Forest plots of the meta-analysis. a Postoperative complications. b Survival time.

Survival time: Seven trials included data on survival. There was no significant difference between the two groups (MD, 0.80; 95% CI: −0.16 to 1.77; p = 0.10). The results showed that the effects of ERCP and PTCD were nearly equal (11.1:10.5 months) (Fig. 4b).

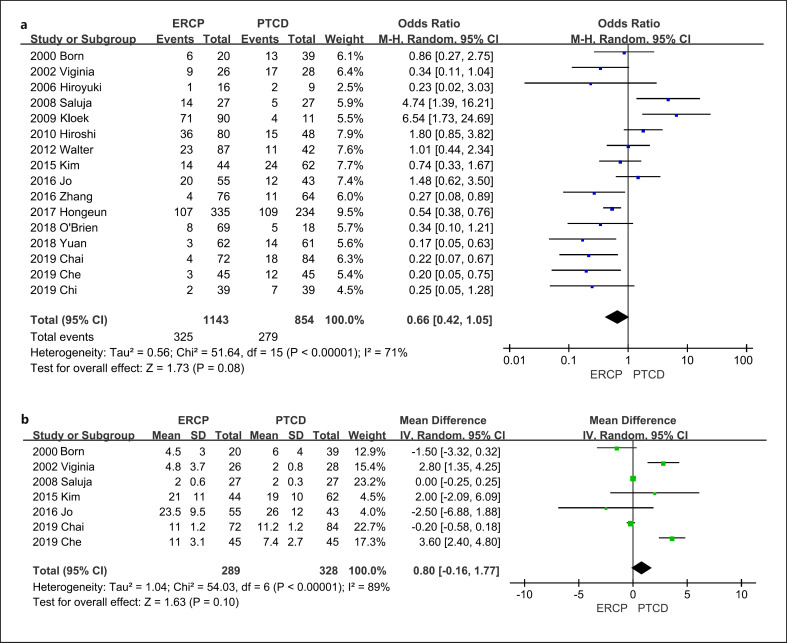

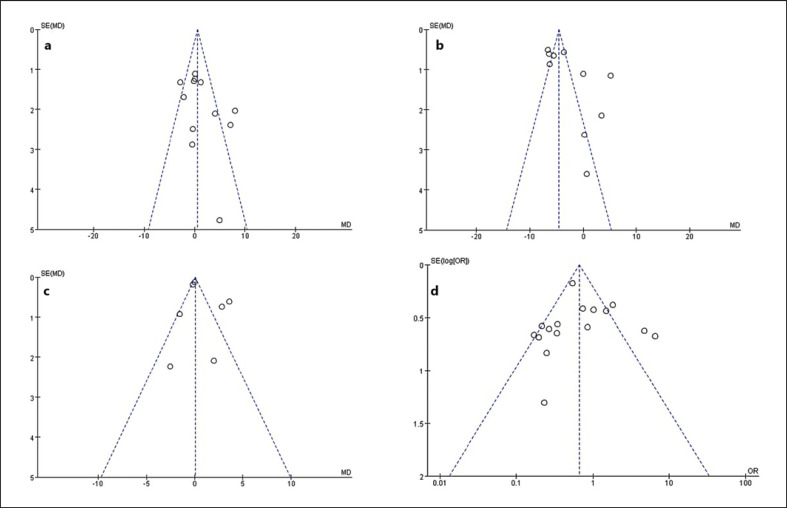

Publication Bias

In this meta-analysis, the funnel plot shapes for the decrease in TBiL, length of hospital stay, postoperative complications, and survival time showed basic symmetry. No significant publication bias was observed. The results were similar, and the combined results were highly reliable (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Funnel plots of the meta-analysis. a 12 articles in the meta-analysis of the decrease in TBiL. b 10 articles in the meta-analysis of hospital stay. c 7 articles in the meta-analysis of survival time. d 16 articles in the meta-analysis of postoperative complications.

Sensitivity and Subgroup Analyses

We performed sensitivity and subgroup analyses for survival time and hospital expenses by evaluating the differences in outcomes and significance using fixed and random-effects models in the meta-analysis or after removing studies with significant bias. Moreover, we divided the studies into subgroups based on (1) whether the study was published in China or elsewhere and (2) NOS score >6. We were able to find a significant source of heterogeneity in the parameters. The underlying reasons may be as follows: (1) most articles in this meta-analysis were retrospective or case-control studies, (2) there were differences in the surgical experience of different operators, and (3) there were no consistent standards in patient selection.

Discussion

MOJ is caused by compression or infiltration by a malignant tumor. As a result, cholestasis and secondary endotoxemia trigger the release of reactive oxygen species, cytokine infiltration, and mitochondrial dysfunction, finally leading to hepatocyte apoptosis and severe complications, including renal or liver failure and coagulation disorders [27, 28, 29]. Biliary malignancies are highly concealed, and jaundice appears late, due to the presence of right vagal hepatic ducts and left and right accessory hepatic ducts in about 9–15% of the general population. When the hepatic duct is occupied by malignant tumors, bile flows out through the “bypass pathway,” which diverts the pressure from the biliary tract, resulting in atypical early clinical symptoms. Thus, diagnosis and treatment are delayed, and the optimal window for radical surgical treatment is lost. There are many patients with extensive metastasis who lose the option of surgery due to advanced age, poor cardiopulmonary function, poor immunity, and other physical conditions [30]. Jaundice can aggravate the injury of Kupffer cells in the liver, impairing the innate immunity associated with the mononuclear macrophage system. With cholestasis, the bile duct becomes predisposed to bacterial growth; in fact, biliary tract infection is the most common perioperative complication, with an incidence of 30–50%. Biliary tract obstruction by a tumor creates “blind bowel loops” in which the lack of bile acid in the intestinal tract causes dysbacteriosis, leading to injury of the intestinal mucosal barrier, ectopic bacterial planting, and electrolyte and metabolic disorders.

Minimally invasive interventions have been rapidly promoted and popularized worldwide because of their advantages of less procedural trauma, positive efficacy, low cost, short hospitalization time, and faster postoperative recovery. A minimally invasive intervention for MOJ involves placing a stent or drainage tube into the obstructed site to relieve jaundice; this can improve the patient's quality of life, create favorable treatment conditions for antitumor therapy, and prolong survival time [31, 32, 33]. ERCP and PTCD are the two main methods for the palliative treatment of MOJ.

PTCD was first used clinically by Molnar and Stocknm in 1974. Biliary dilatation at the stenosis can be performed individually or combined with another procedure such as stent placement and placement of internal and external drainage tubes, according to specific circumstances. PTCD can have a jaundice-reducing effect comparable to that of surgical drainage, and it can also provide a mechanism for local perfusion chemotherapy and intracavity radiotherapy.

ERCP was first developed in 1968, and great progress has been made since then. Many ancillary procedures have been derived from the technique, including endoscopic sphincterotomy, endoscopic pancreatic sphincterotomy, endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage, endoscopic retrograde pancreatic drainage, endoscopic lithotomy, and dilatation of a narrow biliary tract [34, 35, 36]. A recent study of 146 patients who underwent ERCP for obstructive jaundice demonstrated that ERCP was an effective and safe method for the treatment of benign and malignant biliary obstruction [37]. In addition, ERCP enables the diagnosis of malignant stenosis of the distal common bile duct, from where histological samples can be easily obtained [38]. In proximal or intrahepatic bile duct obstruction, PTCD has advantages over ERCP. In a previous study, PTCD decreased the number of patients with postoperative jaundice at different time points, increased 1-year and median survival, and improved the patients' liver function and overall conditions [39]. Because each method has its own advantages and disadvantages, clinicians often have difficulties in choosing between the two.

The results of this meta-analysis suggest that the overall success rates of the surgical treatment of MOJ using ERCP and PTCD are similar. The factors influencing the choice of ERCP are (1) whether the duodenal papilla can be successfully identified through the endoscope; (2) tumor infiltration, pulling, and other factors that can alter the bile duct axis, leading to difficult intubation; and (3) whether the guidewire can smoothly cross the bile duct stenosis. The main factors influencing the choice of PTCD include (1) whether the patient can tolerate the operation; (2) whether the guidewire can pass the biliary stenosis, without which the stents and drainage tube cannot be placed; and (3) whether the angle between the bile duct and the puncture site is too small to place the stent. PTCD has a lower rate of conversion to other methods; this may be because PTCD involves a direct puncture through the liver parenchyma and a shorter pathway to the site of obstruction compared to ERCP. It should be noted that any interventional surgery is invasive, and the therapeutic benefits are accompanied by risks of complications. For example, PTCD is more frequently associated with poor catheter drainage, catheter obstruction, postoperative biliary bleeding, and hepatic injury. ERCP may cause biliary tract infection and acute pancreatitis. Compared with PTCD, the clinical advantages of ERCP with biliary metal stent implantation are that it does not require puncture, is easily performed, and can effectively prevent liver tissue damage. Furthermore, the procedure can be performed with digital subtraction angiography for more precise stent placement. However, a disadvantage of ERCP is that its success is heavily dependent on the anatomical structure because the common bile duct and pancreatic duct form a common channel at the opening of the duodenal papilla in most patients. This leads to inadvertent entry of the catheter or guide thread into the pancreatic duct during the operation, which is also the main cause of postoperative acute pancreatitis.

Finally, endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage has therefore been introduced as an alternative to PTCD in cases of biliary obstruction when ERCP is unsuccessful [40]. A large amount of data was already collected that proves its efficacy, safety, and ability to replace PTCD in cases of ERCP failure. However, the lack of training, absence of enough dedicated devices, and lack of standardization still makes ultrasound-guided biliary drainage a difficult and not very popular procedure, which is related to life-threatening adverse events [41].

Limitations

The advantage of this review is that it provides a comprehensive comparison of ERCP and PTCD. To our knowledge, this is one of the few meta-analyses to explore these two techniques. However, this meta-analysis has limitations that should be noted. First, publication and selection bias could be a substantial issue because of the retrospective matching of cases, patient selection, and assessment of complications. Second, although we searched several databases, the small number of patients and studies limited the statistical reliability. Our results must be confirmed in further high-quality trials with greater sample sizes. Third, we did not further analyze the anatomical conditions and different levels of technology that may influence complication rates. Fourth, ERCP included endoscopic nasobiliary drainage and endoscopic biliary stenting, distinct procedures that were not compared. Fifth, MOJ can be categorized as proximal or distal depending on the location of the obstruction, and we did not compare cases according to these categories. At last, European scholars often preferred ERCP and thus patients presented late for PTCD, and they were more sick patients, so had higher complication rate and prolonged stay in hospital.

Conclusion

The clinical efficacies of ERCP and PTCD for MOJ were similar. Each procedure has strengths and weaknesses. ERCP had a lower rate of postoperative complications, shorter hospital stay, and higher cost efficiency, indicating that ERCP may be a superior initial treatment choice.

Statement of Ethics

An ethics statement is not applicable because this study is based exclusively on published literature.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81670580) and the 345 Talent Project and Shenyang Science and Technology Innovation Talent Support Program for Youth and Midlife (RC200121).

Author Contributions

Liwei Pang: manuscript preparation and data analysis; Shuodong Wu: manuscript editing; Jing Kong: final approval.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81670580) and the 345 Talent Project and Shenyang Science and Technology Innovation Talent Support Program for Youth and Midlife (RC200121).

References

- 1.de Groen PC, Gores GJ, LaRusso NF, Gunderson LL, Nagorney DM. Biliary tract cancers. N Engl J Med. 1999;341((18)):1368–1378. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910283411807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusoff AR, Siti ZM, Muzammil ARM, Yoong BK, Vijeyasingam R. Cholangiocarcinoma: a 10-year experience of a single tertiary centre in the multi ethnicity-Malaysia. Med J Malaysia. 2012;67((1)):45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaib Y, El-Serag HB. The epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2004;24((2)):115–125. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-828889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shin HR, Oh JK, Masuyer E, Curado MP, Bouvard V, Fang YY, et al. Epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma: an update focusing on risk factors. Cancer Sci. 2010;101((3)):579–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01458.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aljiffry M, Walsh MJ, Molinari M. Advances in diagnosis, treatment and palliation of cholangiocarcinoma: 1990–2009. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15((34)):4240–4262. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nehéz L, Andersson R. Compromise of immune function in obstructive jaundice. Eur J Surg. 2003;168((6)):315–328. doi: 10.1080/11024150260284815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pauli-Magnus C, Meier PJ. Hepatocellular transporters and cholestasis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39((4 Suppl 2)):S103–10. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000155550.29643.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wadei HM, Mai ML, Ahsan N, Gonwa TA. Hepatorenal syndrome: pathophysiology and management. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1((5)):1066–1079. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01340406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Robertson J, Peterson J, Welch V, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. 2018. Available at: http://www.ohri.ca/progr ams/clini cal_ epide miolo gy/oxfor d.asp (accessed Mar 18, 2015)

- 10.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. Published 2009 Jul 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Born P, Rösch T, Brühl K, Sandschin W, Weigert N, Ott R, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with advanced hilar bile duct tumors undergoing palliative endoscopic or percutaneous drainage. Z Gastroenterol. 2000;38((6)):483–489. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-14886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piñol V, Castells A, Bordas JM, Real MI, Llach J, Montañà X, et al. Percutaneous self-expanding metal stents versus endoscopic polyethylene endoprostheses for treating malignant biliary obstruction: randomized clinical trial. Radiology. 2002;225((1)):27–34. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2243011517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maguchi H, Takahashi K, Katanuma A, Osanai M, Nakahara K, Matuzaki S, et al. Preoperative biliary drainage for hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14((5)):441–446. doi: 10.1007/s00534-006-1192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saluja SS, Gulati M, Garg PK, Pal H, Pal S, Sahni P, et al. Endoscopic or percutaneous biliary drainage for gallbladder cancer: a randomized trial and quality of life assessment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6((8)):944.e3–950.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kloek JJ, van der Gaag NA, Aziz Y, Rauws EAJ, van Delden OM, Lameris JS, et al. Endoscopic and percutaneous preoperative biliary drainage in patients with suspected hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14((1)):119–125. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1009-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawakami H, Kuwatani M, Onodera M, Haba S, Eto K, Ehira N, et al. Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage is the most suitable preoperative biliary drainage method in the management of patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46((2)):242–248. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0298-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walter T, Ho CS, Horgan AM, Warkentin A, Gallinger S, Greig PD, et al. Endoscopic or percutaneous biliary drainage for Klatskin tumors? J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24((1)):113–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim KM, Park JW, Lee JK, Lee KH, Lee KT, Shim SG. A comparison of preoperative biliary drainage methods for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: endoscopic versus percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. Gut Liver. 2015;9((6)):791–799. doi: 10.5009/gnl14243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jian ZX, he ZL, Liang ZS. Clinical analysis of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage for treatment of malignant obstructive jaundice. Chin J Gen Pract. 2016;14((4)):575–577. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jo JH, Chung MJ, Han DH, Park JY, Bang S, Park SW, et al. Best options for preoperative biliary drainage in patients with Klatskin tumors. Surg Endosc. 2017;31((1)):422–429. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-4993-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee H, Han Y, Kim JR, Kwon W, Kim SW, Jang JY. Preoperative biliary drainage adversely affects surgical outcomes in periampullary cancer: a retrospective and propensity score-matched analysis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25((3)):206–213. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Brien S, Bhutiani N, Egger ME, Brown AN, Weaver KH, Kline D, et al. Comparing the efficacy of initial percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with stenting for relief of biliary obstruction in unresectable cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2020;34((3)):1186–1190. doi: 10.1007/s00464-019-06871-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuan S-tang. Comparison of ERCP and PTCD for biliary metal stent placement in treatment of low malignant obstructive jaundice. Pract Clin Med. 2018;19((11)):33–35. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Che J, Guo-xing W, Xiao HL. Comparative study of ERCP and PTCD in the treatment of obstructive jaundice caused by malignant extrahepatic bile duct tumors. J Clin Exp Med. 2019;18((19)):2091–2094. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang-kun C, Shu-lou S, Zhang K. Comparing the clinical effect of PTCD and ERCP in the treatment of high malignant obstructive jaundice and its effect on liver function. J Hepatobiliary Surg. 2019;27((4)):285–288. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chai CM, Song GD, Fan X. Comparative study of biliary stent placement by percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in treatment of malignant biliary obstruction. World Chin J Digestion. 2019;27:1027–1034. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abrahám S, Szabó A, Kaszaki J, Varga R, Eder K, Duda E, et al. Kupffer cell blockade improves the endotoxin-induced microcirculatory inflammatory response in obstructive jaundice. Shock. 2008;30((1)):69–74. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31815dceea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li DM. Hepatic cell apoptosis in obstructive jaundice[J] Chin J Gen Surg. 2014;23((7)):967–971. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Addley J, Mitchell RM. Advances in the investigation of obstructive jaundice. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14((6)):511–519. doi: 10.1007/s11894-012-0285-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boulay BR, Birg A. Malignant biliary obstruction: from palliation to treatment. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;8((6)):498–508. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v8.i6.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Q, Zhu HD, Guo JH, Teng JG. Status and progress of treatment of malignant biliary obstruction[J] J Southeast Univ (Med Sci Ed) 2014;33((5)):639–643. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez-Miranda M, de la Serna C, Diez-Redondo P, Vila JJ. Endosonography-guided cholangiopancreatography as a salvage drainage procedure for obstructed biliary and pancreatic ducts. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2((6)):212–222. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v2.i6.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khashab MA, Valeshabad AK, Afghani E, Singh VK, Kumbhari V, Messallam A, et al. A comparative evaluation of EUS-guided biliary drainage and percutaneous drainage in patients with distal malignant biliary obstruction and failed ERCP. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60((2)):557–565. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3300-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vila JJ, Artifon EL, Otoch JP. Post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography complications: how can they be avoided? World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4((6)):241–246. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v4.i6.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Delden OM, Laméris JS. Percutaneous drainage and stenting for palliation of malignant bile duct obstruction. Eur Radiol. 2008;18((3)):448–456. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0796-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen BY, Pang LY. Compative study of biliary metallic stent implantation via ERCP and PTCD approaches in treatment of malignant obstructive jaundice. Chin J Bases Clin Gen Surg. 2016;23((8)):967–971. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alatise OI, Owojuyigbe AM, Omisore AD, Ndububa DA, Aburime E, Dua KS, et al. Endoscopic management and clinical outcomes of obstructive jaundice. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2020;27((4)):302–310. doi: 10.4103/npmj.npmj_242_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Cesare E, Puglielli E, Michelini O, Pistoi MA, Lombardi L, Rossi M, et al. Malignant obstructive jaundice: comparison of MRCP and ERCP in the evaluation of distal lesions. Radiol Med. 2003;105((5–6)):445–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qi S, Yan H. Effect of percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainag + radiofrequency ablation combined with biliary stent implantation on the liver function of patients with cholangiocarcinoma complicated with malignant obstructive jaundice. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13((3)):1817–1824. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park DH. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage of hilar biliary obstruction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22((9)):664–668. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karagyozov PI, Tishkov I, Boeva I, Draganov K. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage-current status and future perspectives. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2021 Dec 16;13((12)):607–618. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v13.i12.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.