Abstract

Background

The number of children in sexual minority parent families has increased. This systematic review aims to synthesise the evidence of disparities in family outcomes between sexual minority and heterosexual families and to identify specific social risk factors of poor family outcomes.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, the Web of Science, Embase, the Cochrane Library and APA PsycNet for original studies that compared family outcomes between sexual minority and heterosexual families. Two reviewers independently selected studies and assessed the risk of bias of included studies. Narrative synthesis and meta-analysis were conducted to synthesise evidence.

Results

Thirty-four articles were included. The narrative synthesis results revealed several significant findings for children’s gender role behaviour and gender identity/sexual orientation outcomes. Overall, 16 of 34 studies were included in the meta-analyses. The quantitative synthesis results suggested that sexual minority families may perform better in children’s psychological adjustment and parent–child relationship than heterosexual families (standardised mean difference (SMD) −0.13, 95% CI −0.20 to −0.05; SMD 0.13, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.20), but not couple relationship satisfaction (SMD 0.26, 95% CI −0.13 to 0.64), parental mental health (SMD 0.00, 95% CI −0.16 to 0.16), parenting stress (SMD 0.01, 95% CI −0.20 to 0.22) or family functioning (SMD 0.18, 95% CI −0.11 to 0.46).

Conclusion

Most of the family outcomes are similar between sexual minority and heterosexual families, and sexual minority families have even better outcomes in some domains. Relevant social risk factors of poor family outcomes included stigma and discrimination, poor social support and marital status, etc. The next step is to integrate multiple aspects of support and multilevel interventions to reduce the adverse effects on family outcomes with a long-term goal of influencing policy and law making for better services to individuals, families, communities and schools.

Keywords: child health, public health, systematic review

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

The number of children in families with parents who are sexual minorities has increased.

Despite improvements in public attitudes towards sexual minorities nowadays, sexual minority parenting does remain a controversial topic around the world.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

In countries and regions where same-sex relationships are legalised, most of the family outcomes are similar between sexual minority and heterosexual families, and sexual minority families have even better outcomes in some domains.

Sexual minority families may experience some additional stressors related to their sexual minority status. Community context and climate have an impact on the health and well-being of sexual minority parents and their children. We summarised social risk factors of poor family outcomes and would like to offer suggestions for researchers, policy-makers and practitioners.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Parents’ sexual orientation is not an important determinant of children’s development. We advocate among policy-makers, communities, schools, families and individuals for better awareness of family outcomes of sexual minorities.

More research is needed to learn more about how communities around the world can support positive development among all children of sexual minority parents and how legal and policy contexts affect their lives and their children.

Introduction

Sexual and gender minorities is an umbrella term including lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, gender non-conforming people and other populations whose sexual orientation or gender identity and reproductive development is considered outside cultural, societal or physiological norms.1–3 Compared with the heterosexual population, sexual and gender minorities have an increased risk for health problems.4–6 In recent years, the number of children in families with parents who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer has increased.7–9 A report in 2018 showed that, in the USA, same-sex couples are seven times more likely than different-sex couples to be raising an adopted or foster child, and there are an estimated 114 000 same-sex couples raising children.9 Despite recent improvements in public attitudes towards sexual minority families, sexual minority parenting is still a controversial topic around the world, and the outcomes of sexual minority families remain not fully understood.10 11

Since the 1980s, many countries have started to expand marriage rights to sexual minority couples in the areas of relationship recognition, tax insurance and child adoption.12 In 1989, Denmark was the first country in the world to introduce a law allowing same-sex partnership registration.12 The legal recognition of same-sex relationships (eg, registered partnerships or civil unions) is a critical step forward in advancing equal marriage rights for sexual and gender minorities.13 14 As of December 2021, around the globe over 40 countries and territories allow sexual minority couples to marry. Once national laws and public policies of equal marriage rights for sexual minority couples are settled, the law can ultimately establish necessary conditions for children to be conceived, born and raised; and thus for children to thrive in an optimal environment.15

Given the social, cultural, political and legal divide on the topic of the sexual minority family, debate persists about whether parental sexual orientation affects family outcomes. Evidence from a previous qualitative review suggested that children raised by lesbian and gay parents do not experience adverse outcomes (eg, emotional functioning, stigmatisation) compared with other children.16 A quantitative review indicated that children of gay parents had significantly better outcomes than did children of heterosexual parents on some psychological adjustment domains.17 However, some studies have shown contradictory findings that children from sexual minority parent families may have worse developmental outcomes than children from heterosexual families in some domains, such as children’s health, education or marijuana use.18–20 The sexual minority stress theory suggests that sexual minorities often experience chronic psychosocial stress.21 In recent years, there has been greater attention to sexual minority parents and their children. Numerous studies have compared family outcomes between sexual minority and heterosexual parent households. Based on this body of literature, we included a comparison group of heterosexual parent households in this review.

Thus far, little is systematically known about the disparities in family outcomes between sexual minority and heterosexual families after the legal recognition of same-sex relationships. Further understanding of the disparities in multiple measures of outcomes may inform general debates and policy interventions in family structure and child health. This systematic review aims to compare the disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual parent families in the following major family outcomes: children, parent, household-level outcomes. We also discuss social risk factors of poor family outcomes and offer some suggestions for improving family outcomes.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.22

Search strategy

We searched PubMed, the Web of Science, Embase, the Cochrane Library and APA PsycNet for eligible articles published in any language from 1 January 1989 to 1 April 2022. The detailed search strategies are available in online supplemental appendix S1. We also manually examined reference lists of reviews, original studies and related systematic reviews to identify additional publications that we may have missed in our electronic search.

bmjgh-2022-010556supp001.pdf (3.9MB, pdf)

Eligibility criteria

To meet the inclusion criteria, articles had to: (1) be conducted in the country after the legal recognition of same-sex relationships; (2) be primary studies using qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods; (3) compare the differences between sexual minority and heterosexual parents, and/or their children; and (4) data that have been used once in a manuscript to avoid replication. In addition, all articles were based on the time of recognition of the first type of law, regardless of the type of law. Exclusion criteria included: (1) grey literature (eg, meeting abstracts, dissertations, theses); (2) literature review or purely theoretical discussion paper; (3) a policy statement/agenda; (4) a comment or letter; or (5) lack of data on parenting for sexual and gender minorities. In the USA, some states began to recognise same-sex relationships from 2000. Therefore, for studies conducted in the USA, we included studies conducted after 2000.

Study selection and data extraction

We first exported titles and abstracts identified through the database searches to EndNote and removed duplicates. Two investigators (YZ and MW) independently assessed the titles and abstracts of all identified articles. Then, we obtained and examined the full text of the potential articles and, if necessary, discussed the content with a third review author (MH) to decide whether or not to include articles thought to be contentious. After the study selection process, two reviewers (YZ and MW) independently extracted data from the included studies using a predesigned standardised Excel form with the following information: first author, publication year, location, sample size, age, study design, meta-analysis (yes/no), outcome measures, who reported the data and main finding.

Quality assessment

We assessed the quality of each extracted article using the Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies, Cohort Studies or Qualitative Research Critical Appraisal Tool.23 Two reviewers (YZ and MH) independently assessed risk of bias using percentage scores following Ancheta’s report.24 Low quality of a study was considered if the score percentage was 49% or lower, moderate if the score percentage was 50%–69% and high if the score was 70% or higher. Detailed information about the quality of included articles is listed in online supplemental appendix S2.

Assessment of heterogeneity and publication bias

To assess the heterogeneity of studies in meta-analysis, we applied principles from both Cochran’s Q test and Higgins I2 test. P-value of Cochran’s Q test less than 0.05 considered problematically high heterogeneity. Moderate heterogeneity was considered if I2 was 30%–50%, and high if I² exceeded 50%. Random effects model (p<0.05, I2≥50%) would be used for the data were high heterogeneity, otherwise, a fixed effects model (p>0.05, I2<50%) would be selected. Sensitivity analysis was also conducted if there was problematic heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed by inspecting funnel plots analysis. If the Egger’s test has p>0.05, it means no evidence of publication bias; otherwise, there would be a publication bias.

Outcome measures

A thematic analysis of the literature was conducted to identify outcomes. Two researchers separately coded the outcome measures from each study. The two coding results were compared and discussed. After resolving the discrepancies, outcomes were categorised into the following three main domains with 11 themes: children’s developmental outcomes (children’s psychological adjustment, physical health, gender role behaviour, gender identity/sexual orientation and education outcomes), parents’ psychological adjustment (parental mental health, parenting stress) and household-level outcomes (parent–child relationship, couple relationship satisfaction, family functioning, social support, etc). A detailed definition and explanation of each outcome were listed in online supplemental appendix S3.

Statistical analysis

Most of the outcomes in this review were continuous, so we selected standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% CI as the effect size for reporting the results of meta-analysis. Given that the scoring standards of measurement tools used in different studies are inconsistent, for the scale scores with inconsistent evaluation criteria, we reversed scoring to make the scale in the same direction (online supplemental appendix S4). If the outcomes were measured at a different time point, the terminal follow-up visits were chosen to compare the differences in outcomes between two family types. A fixed effects or random effects model was selected according to the deviance information criterion. We set the significance level at 0.05 for pooled estimation results and built forest plots for each outcome using R V.4.0.4, including three R packages: meta, metafor and dmetar. For the quantitative studies and qualitative studies that could not be included in meta-analysis, we used narrative synthesis to aggregate, integrate and interpret the results. We provided the data of outcome for the main findings in table 1.

Table 1.

Included study characteristics

| Study | Location | Sample size | Age, years mean (range/SD) | Study design | Meta-analysis (yes/no) | Outcome measures | Main finding |

| Farr et al26 | USA | 106 children (56 ([61.9%] LG vs 50 ([38.1%] heterosexual) | Children: 3.01 (1.08-6/1.31); parents: 41.69 (30-60/5.51) | Cross-sectional | Yes | Children’s psychological adjustment; children’s gender role behaviour; couple relationship satisfaction; family functioning*† | No significant differences were found between same-sex parent families and heterosexual parent families in children’s psychological adjustment, gender role behaviour, couple relationship satisfaction, family functioning. |

| Goldberg and Smith27 | USA | 174 parents (107 ([61.5%] LG vs 67 ([38.5%] heterosexual) | Children: 5.42; parents: NA | Cohort | Yes | Children’s psychological adjustment; parents’ mental health; other outcomes: parent-school relationships* | Same-sex parents reported significantly lower levels of child internalising symptoms than heterosexual parents, but not in child externalising symptoms. No significant differences were found in depression. Other related outcomes: Gay men reported the highest parent-teacher relationships quality (3.47 (0.06)) and heterosexual men the lowest (3.05 (0.68)). Lesbians reported the least acceptance by other parents (4.03 (0.10)) than gay (4.39 (0.09)) and heterosexual parents (4.30 (0.66)). Lesbian mothers were the most likely to report negative adoption-related experiences with teachers (20.4%) than gay (5.4%) and heterosexual parents (9.1%). There were no other significant differences for parent-school variables. |

| Bos et al30 | Netherlands | 102 children (51 ([50%] L vs 51 ([50%] heterosexual) | Children: 15.9 (1.30); parents: NA | Cohort | Yes | Children’s psychological adjustment; parent–child relationship; other outcomes: adolescents substance use‡ | The adolescents with lesbian mothers scored significantly lower on the conduct problems and higher on self-esteem than their counterparts in heterosexual families. No significant differences were found in parent–child relationship quality. Other outcomes: No significant differences were found between adolescents in lesbian and heterosexual households in the consumption of cigarettes (0.76 (1.30) vs 0.76 (1.59)), alcohol ((0.60 (0.70) vs 0.82 (1.75))), and marijuana/hashish (0.26 (0.66) vs 0.35 (1.54)). |

| Bos et al31 | Netherlands | 200 families (100 ([50%] L vs 100 ([50%] heterosexual) | Children: 5.95 (4-8/1.30); parents: NA | Cross-sectional | Yes | Children’s psychological adjustment; couple relationship satisfaction* | No significant differences were found in total problem behaviour. Lesbian mothers seem to be significantly more satisfied with their partner as a co-parent than heterosexual mothers are. |

| Gartrell and Bos33 | USA | 171 children (78 ([45.6%] L vs 93 ([54.4%] Achenbach’s normative sample) | Children: 17.05; parents: NA | Cohort | Yes | Children’s psychological adjustment; children’s educational outcomes* | The children with lesbian mothers were rated significantly lower in externalising problem behaviour than the normative sample, not in internalising problem behaviour. The adolescents with lesbian mothers demonstrated higher levels of school/academic competence than gender-matched normative samples (5.2 (0.9) vs 2.8 (0.9)). |

| Averett et al25 | USA | 1384 children (155 ([11.20%] L vs 1,229 ([88.80%] heterosexual) | Children: (1.5–18); parents: 47.80 (8.64) | Cross-sectional | Yes | Children’s psychological adjustment; family functioning* | Same-sex parents reported significantly lower in externalising problems of their adopted children than heterosexual parents reported, but not in internalising problems. In 1.5- to 5-year-old group, no statistically significant differences were found in family functioning. In 6- to 18-year-old group, Same-sex parents reported significantly lower levels of family functioning. |

| McConnachie et al36 | UK | 111 families (68 ([61.3%] LG vs 43 ([38.7%] heterosexual) | Children:11.85 (10-14/1.20); parents: 48.26 (6.09) | Cohort | Yes | Children’s psychological adjustment; parents’ mental health; parent–child relationship*†‡ | No significant differences were found between same-sex parent families and heterosexual parent families in terms of children’s psychological adjustment, parent mental health and parent–child relationship. |

| Bos et al32 | The Netherlands | 190 families (95 ([50%] LG vs 95 ([50%] heterosexual) | Children:11; parents: 40 | Cross-sectional | Yes | Children’s psychological adjustment; parenting stress; social support* | No significant differences were found between same-sex and heterosexual families in children’s psychological adjustment, parenting stress and the use of formal and informal support(formal: 0.73 (0.87) vs 0.70 (1.04); informal: 1.95 (0.77) vs 2.03 (0.66)). |

| Baiocco et al28 | Italy | 390 children (195 ([50%] LG vs 195 ([50%] heterosexual) | Children: 4.33 (3-11/1.83); parents: 39.17 (7.04) | Cross-sectional | Yes | Children’s psychological adjustment; couple relationship satisfaction; family functioning; other outcomes: parental self-agency* | Gay and lesbian parent families reported fewer child psychological problems, higher levels of couple relationship satisfaction and family functioning, than did different-sex parent families. Other outcomes: Gay and lesbian parent families reported higher levels of parental self-agency (27.25 (4.25), 26.46 (4.07)) than did different-sex parent families (25.37 (4.62)), with no differences found between the gay and lesbian parent families. |

| Calzo et al18 | USA | 21 103 children (296 ([1.40%] LGB vs 20,807 ([98.60%] heterosexual) | Children: (4–17); parents: NA | Cross-sectional | Yes | Children’s psychological adjustment; parents’ mental health* | Children of bisexual parents had higher SDQ scores than children of heterosexual parents. Children of lesbian and gay parents did not differ from children of heterosexual parents in emotional and mental health difficulties. Bisexual parents demonstrated substantially higher levels of distress than either lesbian or gay or heterosexual parents. No significant differences were found between gay or lesbian parents and heterosexual parents in distress levels. |

| Golombok et al35 | UK | 130 families (81 ([62.3%] LG vs 49 ([37.7%] heterosexual) | Children: 6 (4-8); parents: 42.22 (6.07) | Cross-sectional | Yes | Children’s psychological adjustment; children’s gender role behaviour; parents’ mental health; parenting stress; parent–child relationship*† | Children in gay and lesbian families were less externalising problems than children in heterosexual parent families, but not in internalising symptoms. No significant difference were found between same-sex and heterosexual families in terms of gender role behaviour. Gay fathers showed lower levels of both depression and parenting stress, but not in anxiety. Gay fathers showed lower levels of parenting stress. Gay fathers showed higher levels of parent–child relationship. |

| Bos and Sandfort29 | The Netherlands | 131 children (63 ([48.09%] L vs 68 ([51.91%] heterosexual) | Children: (8-12); parents: NA | Cross-sectional | Yes | Children’s psychological adjustment; children’s gender identity/sexual orientation‡ | No differences were found in psychosocial adjustment between children with same-sex parents and children with opposite-sex parents. Children in lesbian families felt less parental pressure to conform to gender stereotypes(1.46 (0.53) vs 1.69 (0.65)), were less likely to experience their own gender as superior(2.15 (0.49) vs 2.51 (0.64))and were more likely to be uncertain about future heterosexual romantic involvement(2.32 (0.71) vs 2.08 (0.76)). |

| Sullins39 | USA | 207 007 children (512 ([0.25%] same-sex vs 206,495 ([99.75%] heterosexual) | Children: (0–18); parents: NA | Cross-sectional | No | Children’s psychological adjustment* | Children of same-sex parents have more than twice as prevalent in emotional problems as children of opposite-sex parents (RR: 2.4, 95% CI: 1.7 to 3.0). |

| Regnerus20 | USA | 1155 children (236 ([20.43%] LG vs 919 ([79.57%] heterosexual) | Children: (18–39); parents: NA | Cross-sectional | No | Children’s psychological adjustment; children’s physical health; children’s gender identity /sexual orientation; children’s educational outcomes‡ | The children with same-sex parents worse on the CES-D (depression) index (2.19 vs 1.83) and apt to have thought recently about committing suicide (18% vs 5%), than children in heterosexual married families, but not in anxiety (2.67 vs 2.46). Children of lesbian parents reported worse physical health (3.38), but no significant differences between children of gay parents (3.58) and children of heterosexual married families (3.75). Children of lesbian mother families and gay father families were less likely to self-identify as entirely heterosexual than children of heterosexual married families (61% vs 71% vs 90%). Children of parents who have lesbian or gay romantic relationship worse on educational attainment than do respondents from different-sex married families (2.39 vs 2.64 vs 3.19). |

| Crouch et al38 | Australia | 5525 children (500 ([9.05%] LGBTQ or other vs 5,025 (90.95%] population normative data) | Children: (0–17); parents: NA | Cross-sectional | No | Children’s psychological adjustment; children’s physical health* | Children in same-sex families had higher scores in measures of general behaviour compared with population normative data (β: 2.93, 95% CI: 0.35 to 5.52), but not in SDQ scores, role-emotional/behavioural, mental health and self-esteem scores. Children in sexual minority families had higher scores on measures of general health compared with population normative data (β=5.60, 95% CI=2.69 to 8.52, p = < 0.001), but not in child health for physical functioning, role-physical, and bodily pain (β=0.78, 95% CI = −1.79 to 3.35; β = −0.89, 95% CI = −3.60 to 1.81; β = −1.70, 95% CI = −4.60 to 1.20). |

| Reczek et al37 | USA | 167 047 children (633 ([0.4%] same-sex vs 166,414 ([99.6%] heterosexual) | Children: (4-17); parents: NA | Cross-sectional | No | Children’s psychological adjustment; children’s physical health* | Same-sex cohabiting parents were significantly more likely than different-sex married parents to report higher levels of child emotional difficulties (5.3% vs 0.8%), less likely to respond ‘certainly true’ to the question about children being well-behaved (65.8% vs 79.1 %) and more likely to report good/fair/poor health (20.7% vs 13.8 %). No significant differences were found between children in same-sex married families and children in heterosexual married families on physical health outcomes (18.5% vs 13.8%). |

| Goldberg and Garcia34 | USA | 136 families (80 ([58.8%] LG vs 56 ([41.2%] heterosexual) | Children: (8-16); parents: NA | Cross-sectional | No | Children’s psychological adjustment* | CBCL total score were uncorrelated with family type (r = −0.14, p>0.1). |

| Bos et al40 | USA | 190 families (95 ([50%] L vs 95 ([50%] heterosexual) | Children: 10.67 (6-17/5.04); parents: 47.61 (6.45) | Cross-sectional | No | Children’s physical health; parenting stress; parent–child relationship; couple relationship satisfaction* | No differences were observed between same-sex parents and heterosexual parents in children’s health(4.63 (0.64) vs 4.58 (0.72)), parent–child relationship and couple relationship satisfaction. Same-sex parents reported significantly more stress than did different-sex parents. |

| Goldberg and Garcia42 | USA | 181 parents (104([57.5%] LG vs 77([42.5%] heterosexual) | Children: 6.06; parents: NA | Cohort | No | Children’s gender role behaviour* | No significant differences among lesbian, gay, or heterosexual parent families for girls’ gender role behaviour(37.86 (11.43), 39.38 (11.70), 34.80 (9.24), respectively); boys with lesbian mothers are less masculine than boys in other family types(56.47 (11.76), 62.42 (11.92), 64.49 (9.32) respectively). The degree of gender differentiation did not differ between heterosexual vs gay parent families. |

| Cenegy et al19 | USA | 27 810 families (1,005([3.6%] same-sex vs 26,805([96.4%] heterosexual) | Children: 3.68 (0–17); parents: 36.93 | Cross-sectional | No | Children’s physical health* | Poorer health among children in same-sex couple as well as heterosexual cohabiting couple and never married single-parent families (2.22, 2.31, 2.38, respectively) than heterosexual married families (1.97). |

| Carnaghi et al41 | Italy | 80 children (NA G vs NA heterosexual) | Children: 21.23 (1.97); parents: NA | Cross-sectional | No | Children’s gender role behaviour; children’s gender identity / sexual orientation‡ | The son of the GMM and GMF was perceived as being similarly masculine as the son of the heterosexual couple. The son of the GFF was perceived as less masculine than the sons of all the other parent descriptions.(heterosexual, GMM, GMF, GFF: 3.04 (0.14), 3.05 (0.13), 3.29 (0.13), 3.68 (0.15) respectively). The son raised by heterosexual couple would develop as heterosexual than the son raised by the GMM, the GMF, the GFF(5.29 (0.14) vs 4.81 (0.15), 4.78 (0.14), 4.64 (0.15)). |

| Boertien and Bernardi44 | USA | 1 952 490 children (7,792([0.4%] same-sex vs 1,944,698([99.6%] heterosexual) | Children: 12 (8-16); parents: 43.85 | Cross-sectional | No | Children’s educational outcomes*† | The initial differences between same-sex and different-sex parent families observed in 2008 disappeared within a few years (probability of being behind in school in 2008: 5.1% vs 3.0%; in 2010, 2.4% vs 2.9%). |

| Watkins46 | USA | 1 012 927 children (4,430([0.44%] same-sex vs 1,008,497([99.56%] heterosexual) | Children: NA; parents: NA | Cross-sectional | No | Children’s educational outcomes* | Among the children of married couples, Children who reside with gay, lesbian, heterosexual couples have a grade retention rate of 4.94%, 4.76% and 4.43% respectively. Among the children of unmarried couples, Children who reside with heterosexual, gay and lesbian parents have a grade retention rate of 6.09%, 6.13%, and 4.90%, respectively. |

| Kabátek and Perales45 | The Netherlands | 1 454 577 children (3,006([0.21] same-sex vs 1,451,571([99.79%] heterosexual) | Children: NA; parents: NA | Cross-sectional | No | Children’s educational outcomes*† | Children in same-sex parent families attain overall Cito test scores that are five percentile points higher than those of children in different-sex parent families, and they are more likely to enter an academic (ie, advanced) high school track (AME=21.61%, p<0.01), graduate from high school (AME=1.47%, p=0.01), and enrol in college (AME=11.20%, p=0.02). No differences were found in grade-retention rate (AME = −3.45%, p=0.32). |

| Allen43 | Canada | 1 401 466 parents (1,392([0.1%] LG vs 1,400,074(99.9%] heterosexual) | Children: (0–22); parents: NA | Cross-sectional | No | Children’s educational outcomes c | Children of gay and lesbian parents have a lower graduation rate compared with children of married opposite-sex families (60% vs 52% vs 72%). |

| Farr and Vázquez47 | USA | 209 parents (110([52.6%] LG vs 99([47.4%] heterosexual) | Children: 8.36 (1.66); parents: 47.56 (5.87) | Cohort | Yes | Parents’ mental health; parent–child relationship a, c | No significant differences were found in parents’ mental health and parent–child relationship between same-sex and heterosexual parent families. |

| Farr and Patterson50 | USA | 104 families (54([51.9%] LG vs 50([48.1%] heterosexual) | Children: 3.01 (1.08-6/1.31); parents: 41.69 (30-60/5.51) | Cross-sectional | Yes | Parent–child relationship a | Lesbian couples showed the most supportive and least undermining behaviour, whereas gay couples showed the least supportive behaviour, and heterosexual couples the most undermining behaviour. |

| Gelderen et al48 | UK, The Netherlands, France | 140 families (99([70.7%] LG vs 41([29.3%] heterosexual) | Children: (0.28–0.38); parents: 34.8 (22-59/5.07) | Cross-sectional | Yes | Parents’ mental health; parenting stress; couple relationship satisfaction a | No significant differences were found in anxiety and depression, parenting stress, relationship satisfaction between same-sex couples and different-sex couples after controlling for caregiver role. |

| Goldberg et al51 | USA | 42 parents (30([71.4%] LG vs 12([28.6%] heterosexual) | Children: 4.63 (0–16); parents: 37.55 (6.17) | qualitative | No | Couple relationship satisfaction a | There were few differences in intimate relationships by parent sexual orientation. Same-sex couples cited some additional stressors related to their sexual minority status. |

| Farr49 | USA | 184 parents (103([56%] LG vs 81([44%] heterosexual) | Children: 8.38 (1.62); parents: 47.50 (5.56) | Cohort | Yes | Parenting stress; family functioning a | No significant differences were found between family types in parent adjustment and family functioning. |

| Solomon et al53 | USA | 985 parents (573([41.8%] LG vs 412([58.2%] heterosexual) | Children:14.29 (11.76); parents: 43.38 (7.27) | Cross-sectional | No | Social support a | The three types of couples (lesbians in civil unions, lesbians not in civil unions, and heterosexual married women) did not differ on perceived social support from friends(15.55 (4.45) vs 15.80 (4.22) vs 14.86 (4.32)). Lesbians in civil unions and not in civil unions perceived significantly less social support from family than did heterosexual married women.(12.14 (6.60) vs 11.29 (6.58) vs 15.33 (5.15)). Gay men in both types of couples perceived significantly more social support from friends than did heterosexual married men(15.26 (4.76) vs 11.42 (5.35)). The three groups (gay men in civil unions, gay men not in civil unions, and heterosexual married men) did not differ significantly in perceived social support from family (11.90 (6.48) vs 11.07 (6.46) vs 12.80 (5.89)). |

| Goldberg et al52 | USA | 84 parents (60([71.4%] LG vs 24([28.6%] heterosexual) | Children: 4.63 (0–16); parents: 37.55 (6.17) | qualitative | No | Social support a | Lesbian and gay participants faced additional concerns regarding the security of their placement due to the possibility for discrimination. |

| Goldberg et al55 | USA | 45 parents (30([66.67%] LG vs 15([33.33%] heterosexual) | Children: 5.78 (1.51); parents: NA | qualitative | No | Other outcomes: parental school involvement a | Gay male couples (n=9) and heterosexual couples (n=8) more often described differential involvement, whereby one partner was more involved at school than the other; lesbian couples were slightly less likely to describe a pattern of differential involvement (n=5). |

| Goldberg and Smith54 | USA | 105 parents (65([61.90%] LG vs 40([38.10%] heterosexual) | Children: 3.47 (0.99); parents: NA | Cross-sectional | No | Other outcomes: preschool selection considerations and experiences of school mistreatment a | Same-sex parents were more likely to consider racial diversity than heterosexual parents when selecting children’s preschool (47.5% vs 28%). In reporting on their experiences with schools, heterosexual parents were more likely to perceive mistreatment due to their adoptive status than sexual-minority parents. |

Data are mean, range, mean (SD), or mean (range), unless otherwise stated. Children refer to parents’ offspring of all ages throughout the article. In sample size column, LGBTQ refer to lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer parents, respectively. In outcome measures column, *parent-reported data, †teacher-reported data and ‡child-reported data. In main finding column, the data of each study included in meta-analysis were listed in online supplemental appendix tables S4A–S4F.

AME, estimates from logistic regression models are expressed as average marginal effects (AMEs); GFF, gay male parents both described as feminine; GMF, gay male parents, one described as masculine and one as feminine; GMM, gay male parents both described as masculine; NA, Not Applicable.

Patient and public involvement

Patients or members of the public were not directly involved in this research study.

Results

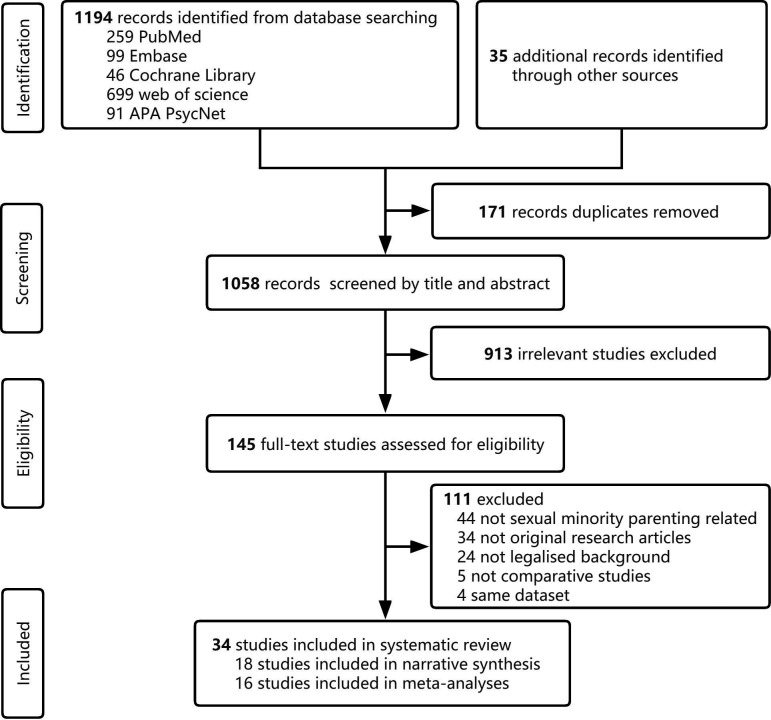

The search identified 1194 articles plus 35 articles through other sources, of which 1058 articles remained after duplicates were removed. Moreover, 913 articles were considered irrelevant and further excluded after title and abstract screening, which left 145 eligible articles for full-text screening. After further excluding 111 articles for various reasons, 34 articles remained for analysis in this review (figure 1), of which, 18 were included for narrative synthesis and 16 for meta-analyses.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study selection procedure.

Study characteristics

Table 1 displays the characteristics of studies included in the current systematic review and meta-analysis. Data and outcome measures of each study included in meta-analyses are listed in online supplemental appendix S4. Most studies (n=22) were conducted in the US, two were conducted in Australia and Canada, respectively; whereas the remaining studies (n=10) were conducted in Europe. Among the 34 studies, seven were cohort studies, 22 were cross-sectional studies, and three were qualitative studies. Three qualitative studies all used thematic analysis for data analysis. One research article was on gay parent families only, and three research articles were on lesbian parent families only. Twenty-eight research articles were on both gay and lesbian parent families. One research article was on lesbian, gay and bisexual parent families; and one was on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer parents. Our analysis included four articles at moderate risk of bias and 30 articles at low risk of bias. No studies were considered at severe risk of bias. Risk of bias was mainly related to confounding factors, or non-objective measures of exposure factors (online supplemental appendix S2). The included 34 studies were categorised into the following three areas including 11 main themes: children’s developmental outcomes (17 for children’s psychological adjustment,18 20 25–39 five for children’s physical health,19 20 37 38 40 four for children’s gender role behaviour,26 35 41 42 three for children’s gender identity/sexual orientation,20 29 41 six for children’s educational outcomes,20 33 43–46 parents’ psychological adjustment (six for parental mental health,18 27 35 36 47 48 five for parenting stress,32 35 40 48 49 household-level outcomes (six for parent–child relationship,30 35 36 40 47 50 six for couple relationship satisfaction,26 28 31 40 48 51 four for family functioning,25 26 28 49 three for social support,32 52 53 and five outcomes that cannot be grouped into themes (preschool selection considerations,54 parental school involvement,55 parent-school relationships,27 parental self-agency,28 and child’s substance use.30 The outcome measures in table 1 were listed in the order of the above themes.

Children’s psychological adjustment

We identified 17 studies in this search with regard to children’s psychological adjustment, among them, five articles were included in narrative synthesis. Three studies reported that children of sexual minority parents were as likely as children of heterosexual parents to grow up healthy and well adjusted.34 37 38 Two studies reported more emotional problems for children with sexual minority parents than for children with heterosexual parents20 39 (table 1).

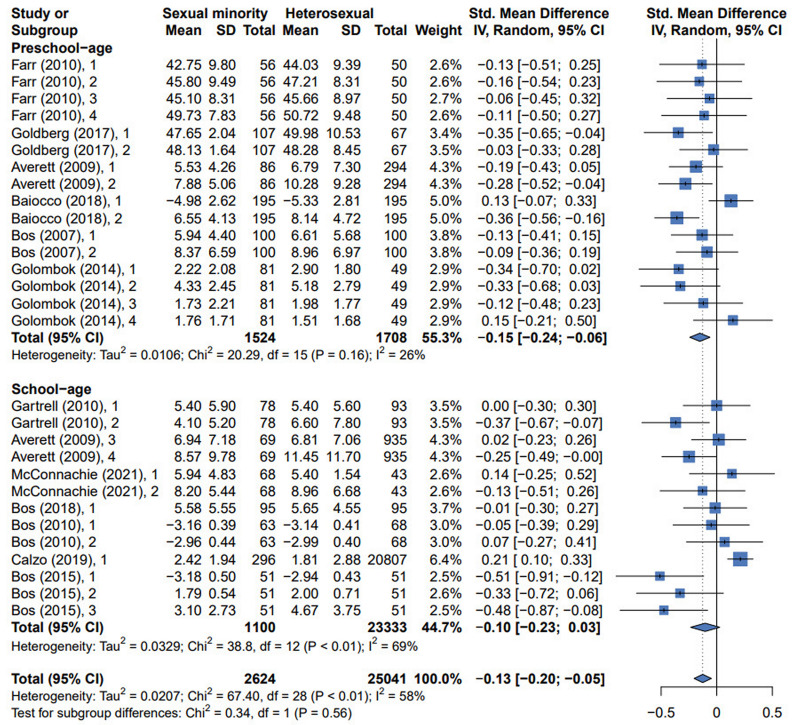

Among the 17 studies, 12 were selected for meta-analysis.18 25–33 35 36 The overall effect size for children’s psychological adjustment was statistically significant (SMD −0.13, 95% CI [95% CI] −0.20 to −0.05) (figure 2). Sensitivity analysis showed the overall effect size was not influenced by removing single effect size (online supplemental appendix S5A). Egger’s regression test showed there was a publication bias (p<0.05) (online supplemental appendix S7A). This result indicates that children raised by sexual minority parents were found to adjust better on some psychological domains than children raised by the different-sex parents.

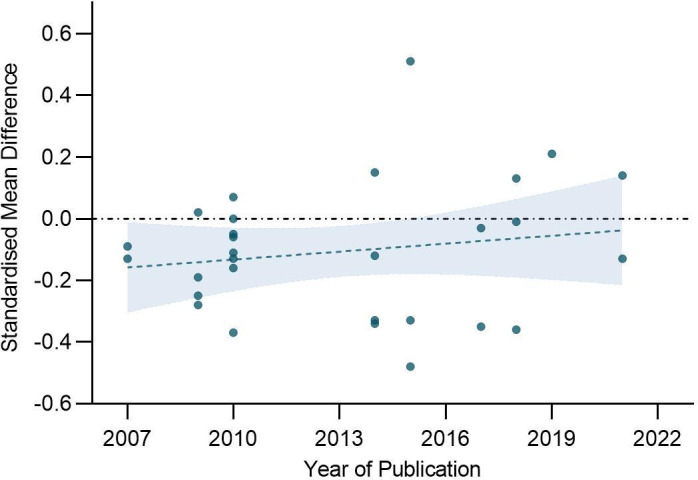

Figure 2.

The forest plots for children’s psychological adjustment.

Further, we stratified studies by age of children (school-age vs preschool-age), pathway to parenthood (adopted vs biological), outcome measure type (internalising vs externalising), country (USA vs the Netherlands vs UK vs Italy), geographical region (continent) (online supplemental appendix S6). In the preschool-age group (≤ 6 years), the results indicated that sexual minority parents reported significantly fewer psychological problems of children than heterosexual parents (SMD −0.15, 95% CI −0.24 to −0.06). In the school-age group (> 6 years), no differences were found between children with sexual minority parents and children with heterosexual parents (SMD −0.10, 95% CI −0.23 to 0.03). This suggests the age of the children may be a factor affecting the pooled effect size. The effect size was significant for both the adopted subgroup and biological subgroup (SMD −0.15, 95% CI −0.23 to −0.07; SMD −0.16, 95% CI −0.28 to −0.03). In addition, subgroup analysis results showed that heterosexual parents reported significantly more internalising and externalising problems among their children than reported by sexual minority parents (SMD −0.12, 95% CI −0.21 to −0.03; SMD −0.23, 95% CI −0.32 to −0.13). When subgroup analysis was performed by country, sexual minority parents reported significantly fewer psychological problems than heterosexual parents in the Netherlands (SMD −0.16, 95% CI −0.29 to −0.03). The results of subgroup analysis by region showed that, in Europe, there is a statistically significant effect size (SMD −0.14, 95% CI −0.24 to −0.03); in the Americas, the effect size was not statistically significant (SMD −0.11, 95% CI −0.23 to −0.00). Finally, we analysed the change of difference between children in sexual minority families and children in heterosexual families in children’s psychological adjustment over time (the year of publication). As shown in figure 3, there was a decreasing trend in the difference between the two groups over time.

Figure 3.

The change of difference between children in sexual minority families and children in heterosexual families in children’s psychological adjustment over time.

Children’s physical health

Five studies on children’s physical health were included in narrative synthesis.19 20 37 38 40 Three articles reported that children in sexual minority parent and heterosexual households are similar on physical health outcomes.37 38 40 Children in cohabiting households have poorer health outcomes than children in married households.19 37 Regnerus’s study showed that the children of lesbian parents report worse physical health,20 but it is worth noting that the result should be taken with caution because its definition of ‘child with same-sex parents’ is controversial.17 37 39

Children’s gender role behaviour

Four articles reported children’s gender role behaviour,26 35 41 42 all of which were included in narrative synthesis. Two articles show there were no significant differences among children in different family type in gender role behaviour.26 35 In Goldberg’s research, sons in lesbian parent families were less masculine than sons in gay and heterosexual parent families; but there were no significant differences across family type for girls’ behaviour at each time point.42 In addition, sons of GMM (gay-male parents both described as masculine) are similarly masculine as sons of heterosexual parents. The son of the GFF (gay-male parents both described as feminine) was perceived as less masculine than the sons of the other parent descriptions.41

Children’s gender identity/sexual orientation

All three studies show that children’s gender identity/sexual orientation may vary by family type.20 29 41 These studies found that compared with the children who lived in heterosexual parent families, the children who lived in sexual minority parent families had a lower expected likelihood of developing as heterosexual.20 29 41 The detailed results were shown in table 1.

Children’s educational outcomes

We conducted a narrative synthesis of six studies on children’s educational outcomes.20 33 43–46 Four studies indicated that children from same-sex couples appear to have the higher rate of grade retention, lower graduation rate or worse educational attainment than children from different-sex couples.20 43 44 46 On the contrary, two studies reported that children in sexual minority parent families outperform children in heterosexual parent families on standardised test scores, high school graduation rates, college enrolment, and school/academic competence.33 45

Parents’ psychological adjustment

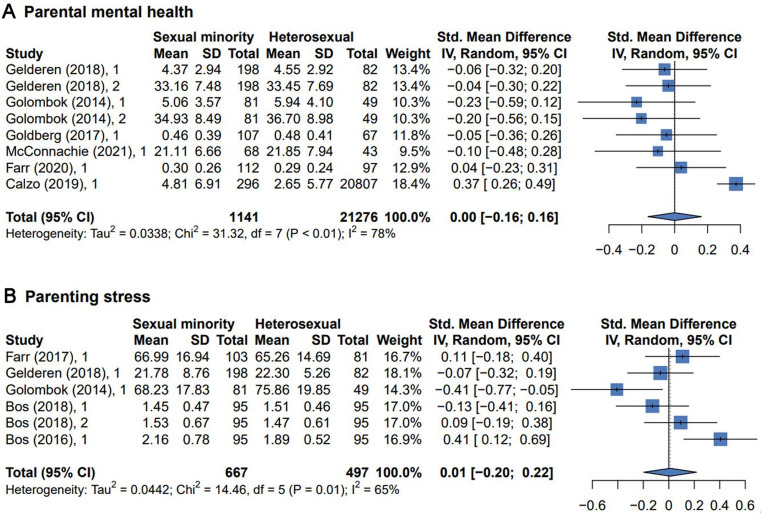

Parental mental health (anxiety, depression and distress) and parenting stress were included in this topic. For parental mental health, bisexual individuals in general experience greater levels of psychological distress than lesbian or gay and heterosexual individuals.18 When comparing gay or lesbian vs heterosexual parents, the result did not reveal appreciable differences in distress levels.18 As for quantitative synthesis results (figure 4A), the results of six studies on parental mental health showed no significant differences between family types in terms of parental mental health (SMD 0.00, 95% CI −0.16 to 0.16).18 27 35 36 47 48 Sensitivity analysis showed the overall effect size was not influenced by removing single effect size (online supplemental appendix S5B). Egger’s regression test showed a publication bias (p<0.05) (online supplemental appendix S7B).

Figure 4.

The forest plots for parents’ psychological adjustment.

Five articles reported the differences in parenting stress.32 35 40 48 49 All these studies were chosen for meta-analysis. The estimated overall effect size was not statistically significant (SMD 0.01, 95% CI −0.20 to 0.22) (figure 4B), showing that the parenting stress was no different between sexual minority and heterosexual parents. Sensitivity analysis showed no single effect size influenced the overall result (online supplemental appendix S5C). Egger’s regression test also showed no evidence of publication bias (p>0.05) (online supplemental appendix S7C).

Parent–child relationship

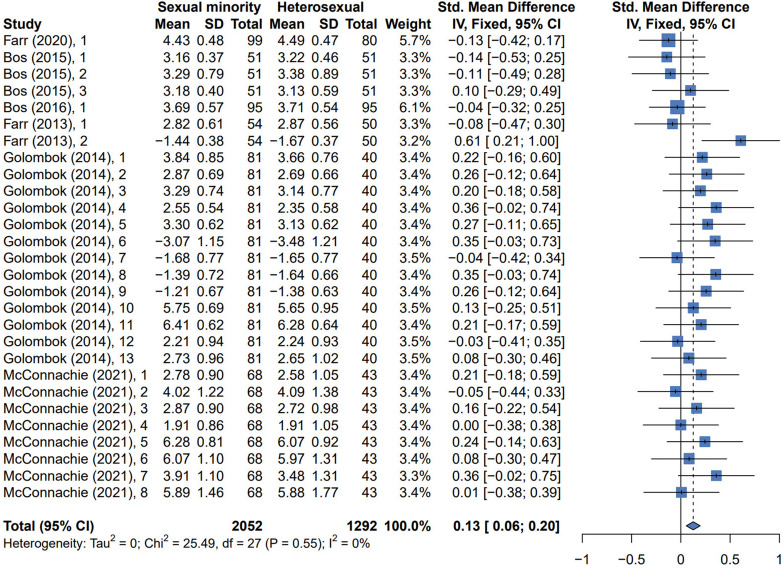

Six studies reported the differences in parent–child relationships among different family types, all of them were selected for meta-analysis.30 35 36 40 47 50 The overall effect size was statistically significant (SMD 0.13, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.20) (figure 5), indicating that sexual minority parent groups showed higher levels of parent–child relationship quality, such as higher levels of warmth, greater amounts of interaction and more supportive behaviour, when compared with the heterosexual parent groups. Egger’s regression test showed no publication bias (p>0.05) (online supplemental appendix S7D). Sensitivity analysis showed no single effect size influenced the overall result (online supplemental appendix S5D).

Figure 5.

The forest plots for parent–child relationship.

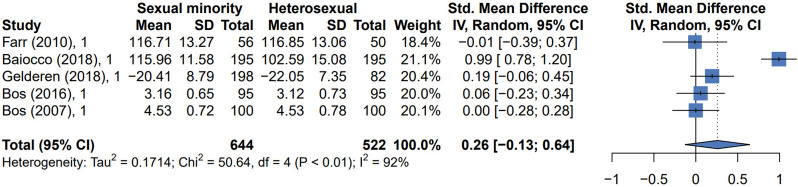

Couple relationship satisfaction

Six studies collected data on couple relationship satisfaction among different family types.26 28 31 40 48 51 Among them, a qualitative study examined changes in couple intimate relationship. The finding showed few differences in intimate relationship by parent sexual orientation.51 Another five studies were chosen for meta-analysis.26 28 31 40 48 The estimated overall effect size was not statistically significant (SMD 0.26, 95% CI −0.13 to 0.64) (figure 6), indicating that sexual minority couples and heterosexual couples did not show difference on these measures of couple relationship satisfaction. Egger’s regression test showed no publication bias (p>0.05) (online supplemental appendix S7E). Sensitivity analysis showed no single effect size influenced the overall result (online supplemental appendix S5E).

Figure 6.

The forest plots for couple relationship satisfaction.

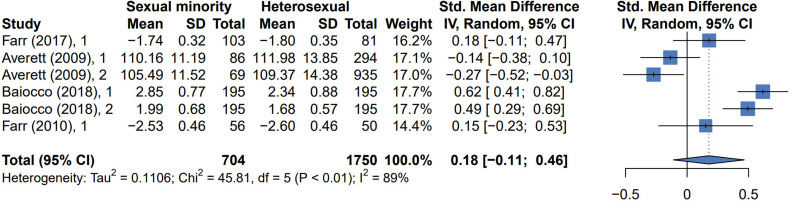

Family functioning

All studies of this topic were chosen for meta-analysis.25 26 28 49 From figure 7, the heterogeneity test showed wide heterogeneity across effect sizes (p<0.05, I2=89%). The random effects model was used. The overall effect size was not statistically significant (SMD 0.18, 95% CI −0.11 to 0.46), suggesting that family functioning was no different between sexual minority parent families and heterosexual families. Sensitivity analysis showed the overall effect size was influenced by removing single effect size (online supplemental appendix S5F). Leave-one-out analysis showed that no singular study when omitted diminished the significant heterogeneity present (online supplemental appendix S5F). Egger’s regression test showed there was a publication bias (p<0.05) (online supplemental appendix S7F), which also adds uncertainty to the estimates. Given that these differences are sensitive to sample exclusions, it is recommended that the result based on six effect sizes should be interpreted with caution. Thus, the certainty of evidence was graded low.

Figure 7.

The forest plots for family functioning.

Social support

Three articles reported the differences in social support among gay, lesbian and heterosexual parent families.32 52 53 All three studies on this topic were included in narrative synthesis (table 1). Overall, same-sex parents did not perceive a significant lack of social support.32 53 Lesbian and gay participants faced additional concerns regarding the security of their placement due to the possibility of homophobic discrimination.52

Other outcomes

Five outcomes cannot be grouped into themes. Three studies report the outcomes on school-related aspects,27 54 55 the detailed results are listed in table 1. Regarding the consumption of cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana/hashish, no significant differences were found between children in lesbian parent families and children in heterosexual parent families.30 Compared with different-sex parent families, same-sex parent families reported higher levels of parental self-agency.28

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to identify the disparities in family outcomes between sexual minority parent families and heterosexual parent families against the background of legal recognition of same-sex relationships. Contrary to many concerns, our review found most family outcomes were similar between these two family types, and sexual minority families have even better outcomes in some domains, such as child psychological adjustment and child-parent relationships.

While some evidence was found that sexual minority parents were more likely than heterosexual parents to adopt hard-to-place children,54 our meta-analysis found better psychological adjustment in children raised by sexual minorities, especially in preschool age children. This result is consistent with previous reviews17 and may be due to better preparedness in the face of strong anti-gay stigma related to sexual minority parent families, and therefore may have displayed greater adjustment difficulties. Another potential explanation is potential higher socioeconomic status and more egalitarian parenting roles in sexual minority parent families.17 Sexual minorities historically have faced more rigorous scrutiny than heterosexuals regarding their rights to become parents.15 In fact, growing up with sexual minority parents may confer some advantages to children. They have been described as more tolerant of diversity and more nurturing towards younger children than children of heterosexual parents.15

Based the results of narrative synthesis, children who lived in sexual minority parent families had a lower expected likelihood of developing as heterosexual, compared with the children who lived in heterosexual parent families.20 29 41 Moreover, the level of gender stereotype is moulded by the parent-related gender-role information.41 For example, the son of the GFF was perceived as less masculine.41 There may be less gender stereotyping in minority parent families, and this effect may be positive. Regardless of family type, if parents hold more liberal attitudes towards gender-related behaviour, their children hold more flexible attitudes towards gender.29 Children of sexual minority parents receive different gender-related information and they will likely develop different ideas about gender identity or sexual orientation than their counterparts in heterosexual families. The impact of sexual minority parents’ attitudes toward gender on their children might be uniquely positive. Exploration of gender identity and sexuality may actually enhance children’s ability to succeed and thrive in a range of contexts.

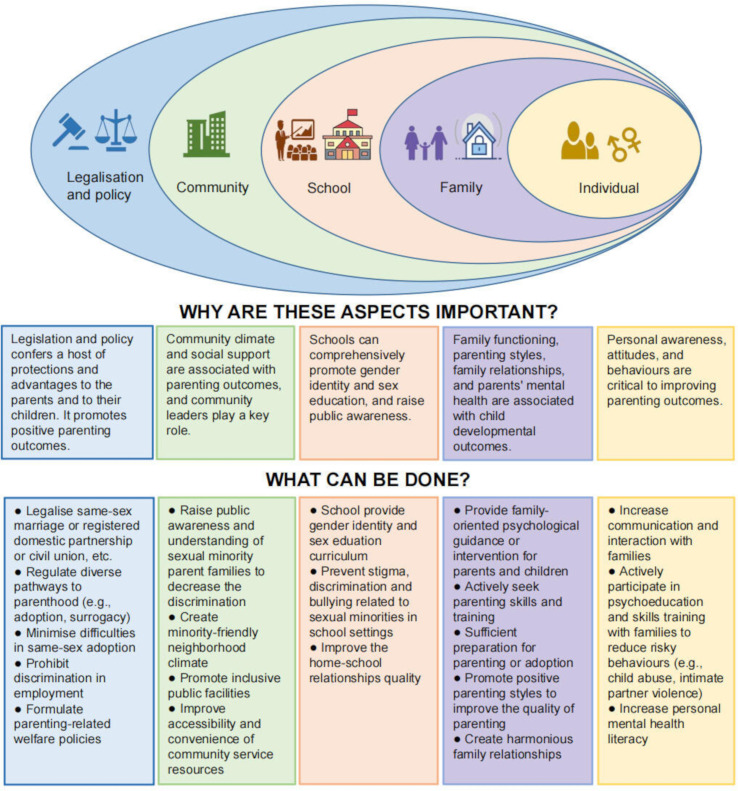

Implications for policy and practice

Our findings indicated that children of sexual minority couples are not at a disadvantage when compared with children of heterosexual couples. We advocate among policy-makers, communities, schools, families, and individuals for better awareness of family outcomes of sexual minorities. Despite some shared characteristics and experiences, families headed by sexual minorities are diverse. The experiences may influence parenting practices and family dynamics.56 To address the existing key problems, several actions are necessary to improve sexual minorities’ family outcomes. Based on the findings from our systematic review as well as some specific recommendations that were originally detailed in the included studies, we summarised social risk factors of poor family outcomes and would like to offer suggestions for researchers, policy-makers, and practitioners that might lead to better family outcomes for sexual minority families (figure 8).

Figure 8.

Proposed actions to improve the family outcomes.

Factors related to children’s psychological adjustment

A growing body of research has demonstrated a link between family process variables and children’s psychological adjustment, such as parenting stress, couple satisfaction, and parenting quality.26 28 32 35 36 Much research has shown that parenting stress and parental mental health are linked to children’s psychological adjustment.17 18 20 26 32 36 39 48 49 51 Parents under greater stress are less likely to provide supportive home environments for their children, consequently children’s development may be affected.57 Children are more likely to thrive when their parents are in good mental health.58 Therefore, it is essential to provide psychological guidance or intervention for parents and children.

The family environment may influence children’s adjustment.18 30 35 59 60 Lower couple relationship satisfaction and parents’ unstable union statuses were significantly associated with assessments of child behaviour problems.26 28 31 37 And, parenting styles were also found to be significantly associated with children’s adjustment.26 49 60 Therefore, it is essential to promote positive parenting styles and increase communication and interaction among family members.

Social climate and environment may be related to children’s psychological adjustment.27 61 Figure 3 suggested that there was a decreasing trend in the difference between children of sexual minority parents and children of heterosexual parents in children’s psychological adjustment over time, which may be due to an increasingly inclusive social environment and greater public awareness of sexual minorities. Homophobic stigmatisation and perceived stigma were related to more psychological problems.33 38 Subgroup analysis by country and region showed that, sexual minority parents reported significantly fewer psychological problems than heterosexual parents in Europe, especially in the Netherlands. Indeed, the Netherlands was the first country in the world to legalise same-sex marriage.14 In a country with a rather tolerant climate toward homosexuality, life may be easier for both children and parents in a sexual minority family.

Factors related to children’s physical health

Studies have shown that children in cohabiting households or single-parent families have poorer health outcomes than children in married households.19 37 Legal marriage confers a host of protections and advantages to the couples who marry and to their children.62 These findings play an important role in health policy, improving child health outcomes.

Factors related to children’s educational outcomes

Research suggests that adequate parenting preparation and positive parenting are important for children’s educational outcomes.63–65 Discrimination and stigma related to parental sexual orientation are an important risk factor.44 Therefore, sexual-minority parents were more likely to consider racial diversity of school than heterosexual parents.54 Parental instability has been found to be detrimental for their children’s educational outcomes.44 62 Parents should make sufficient preparation for parenting, and fully participate in the children’s education process. Schools should take measures to prevent stigma, discrimination and bullying related to sexual minorities in the school setting.

Factors related to family relationship

Many new parents experienced a decline in their relationship quality across the first year of parenthood.51 Parents who reported greater use of confrontative coping, higher levels of depression, and higher levels of relationship maintenance behaviours in pre-adoption reported a greater decline in couple relationship quality.66 At the same time, the exposure to sexual minority stressors might have a negative influence on partner relationship satisfaction.48 On the contrary, some participants emphasised that the experience of parenting had enhanced their relationship and brought them closer.51 Practitioners should provide supportive interventions for diverse couples during the transition to parenthood and reduce sexual minority stressors.

Factors related to parents’ psychological adjustment

Greater social support was related to lower parenting stress.20 57 Parents with older children, more children, and children who were adopted at older ages reported more parenting stress.57 For parenting stress, there was a significant decline over time for heterosexual parents but not for gay and lesbian parents.67 Based on the sexual minority stress model, sexual minority parents may be stigmatised in relation to their sexual orientation.68 Participants with better self-identity and who were more open about their sexual orientation reported higher self-esteem and more positive feelings overall.57 Therefore, social workers or related professionals should provide parenting skills guidance and psychological intervention. At the same time, it is essential to raise public awareness and understanding of sexual minority parent families to reduce discrimination.48

Factors related to social support

Given the Netherlands’ reputation for liberal policies, Dutch children would be more likely than children in some other areas to tell peers about their mothers’ sexual identities and less likely to say they had encountered prejudice and discrimination.56 Social support and community climate variations have an impact on the health and well-being of sexual minority parents and their children.69 Overall, legal marriage confers a host of protections and advantages to the couples who marry and to their children,15 such legalisation reduces the stress and stigma of homosexuality.43 62

Limitations

Despite the significance of this review study, there were a few limitations. First, our overall pooled estimates may be overestimated. Since the studies were limited to regions where same-sex relationships were legalised, most of the studies we included originated in Western Europe and North America, where the social climate for sexual minority parents is generally favourable. The next step could be to summarise the studies conducted in the regions where same-sex relationships are illegal. Second, most of the samples included in this review were gay and lesbian households. Some also considered the unique experiences and concerns of bisexual parents. For example, bisexual parents appear to be in different-gender partnerships or single, and report higher psychological distress than parents of other sexual identities.70 Research on transgender or other sexual minority parent families remains relatively limited.71 72 Important future directions will be exploring the experiences of bisexual- and transgender-parents and their children. Thirdly, based on the availability of the existing data, we were not able to conduct more detailed and in-depth analysis for demographic characteristics. Future reviews need to pay more attention to the demographic characteristics when summarising their findings. Fourthly, we might not have fully captured the effects of changes in legislation implementation on the outcomes. The legal situation for sexual minority parents varies from one country to another around the world.56 Researchers need to learn more about how legal and policy contexts affect the lives of sexual minority parents and their children.73 In addition, our analysis included four articles with a moderate risk of bias.20 40 41 53 We should evaluate these results with caution, especially when considering the controversial study by Regnerus.20

Conclusion

This review showed that most of the family outcomes are similar between sexual minority families and heterosexual families. Research on sexual minority parents and their children has broadened our understanding of contemporary family life, and has added to our understanding of parenting and child development. One contribution of this review is the recognition that parents’ sexual orientation is not, in and of itself, an important determinant of children’s development. Another contribution of this review is that there are significant risk factors often associated with the sexual minority experience and family functioning, such as stigma, poor social support and parenting styles. Policy-makers, practitioners and the public must work together to improve family outcomes, regardless of sexual orientation. In the years ahead, we need to learn more about how communities around the world can support positive development among all children of sexual minority parents and how legal and policy contexts affect their lives and their children.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Contributors: YZ, HH and MW contributed equally to this paper and are joint first authors. WP and CN contributed equally to this paper and are joint last authors. YZ, HH, MW, and CN conceived and designed the study. YZ, MW and HH conducted the systematic search, screened articles, and read the full texts for eligibility. YZ and MW extracted data from the original studies. YZ and HH evaluated the studies for risk of bias. JZ and YZ performed the analyses. YZ, HH and MW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. WP and CN contributed to the interpretation of the results and critically revised the manuscript as well as monitored the review process. All authors provided advice at different stages. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. CN is the guarantor.

Funding: This study received support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81803295 and 81760602), the Innovation Project of Guangxi Graduate Education (YCSW2022201).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Athan AM. Reproductive identity: an emerging concept. Am Psychol 2020;75:445–56. 10.1037/amp0000623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wynn JK, Reavis EA. Representation of sexual and gender minorities in psychiatric research. Psychiatry Res 2022;307:114324. 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Center for Biotechnology Information . Sexual and gender minorities. 2022. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/?term=Sexual+and+gender+minorities

- 4.Thoma BC, Eckstrand KL, Montano GT, et al. Gender nonconformity and minority stress among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci 2021;16:1165–83. 10.1177/1745691620968766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Post D, Veling W, investigators G. Sexual minority status, social adversity and risk for psychotic disorders-results from the group study. Psychol Med 2021;51:770–6. 10.1017/S0033291719003726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vélez C, Casimiro I, Pitts R, et al. Digestive health in sexual and gender minority populations. Am J Gastroenterol 2022;117:865–75. 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farr RH, Vázquez CP, Patterson CJ. LGBTQ adoptive parents and their children. In: Goldberg A, Allen K, eds. LGBTQ-parent families: innovations in research and implications for practice. Cham: Springer, 2020: 45–64. Available: 10.1007/978-3-030-35610-1_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reczek C. Sexual- and gender-minority families: a 2010 to 2020 decade in review. J Marriage Fam 2020;82:300–25. 10.1111/jomf.12607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Williams Institute . How many same-sex couples in the US are raising children? 2018. Available: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/same-sex-parents-us

- 10.Patterson CJ. Parental sexual orientation, parental gender identity, and the development of children. Adv Child Dev Behav 2022;63:71–102. 10.1016/bs.acdb.2022.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg AE, Gartrell NK. LGB-parent families: the current state of the research and directions for the future. Adv Child Dev Behav 2014;46:57–88. 10.1016/b978-0-12-800285-8.00003-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roseneil S, Crowhurst I, Hellesund T, et al. Changing landscapes of heteronormativity: the regulation and normalization of same-sex sexualities in europe. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 2013;20:165–99. 10.1093/sp/jxt006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herek GM. Legal recognition of same-sex relationships in the United States: a social science perspective. Am Psychol 2006;61:607–21. 10.1037/0003-066X.61.6.607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trandafir M. The effect of same-sex marriage laws on different-sex marriage: evidence from the Netherlands. Demography 2014;51:317–40. 10.1007/s13524-013-0248-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pawelski JG, Perrin EC, Foy JM, et al. The effects of marriage, civil Union, and domestic partnership laws on the health and well-being of children. Pediatrics 2006;118:349–64. 10.1542/peds.2006-1279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderssen N, Amlie C, Ytterøy EA. Outcomes for children with lesbian or gay parents. A review of studies from 1978 to 2000. Scand J Psychol 2002;43:335–51. 10.1111/1467-9450.00302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller BG, Kors S, Macfie J. No differences? meta-analytic comparisons of psychological adjustment in children of gay fathers and heterosexual parents. Psychol Sex Orient Gender Diversity 2017;4:14–22. 10.1037/sgd0000203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calzo JP, Mays VM, Björkenstam C, et al. Parental sexual orientation and children’s psychological well-being: 2013-2015 National health interview survey. Child Dev 2019;90:1097–108. 10.1111/cdev.12989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cenegy LF, Denney JT, Kimbro RT. Family diversity and child health: where do same‐sex couple families fit? J Marriage Fam 2018;80:198–218. 10.1111/jomf.12437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Regnerus M. How different are the adult children of parents who have same-sex relationships? findings from the new family structures study. Soc Sci Res 2012;41:752–70. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 2003;129:674–97. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aromataris E, Munn Z. JBI manual for evidence synthesis: JBI. 2020. Available: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global

- 24.Ancheta AJ, Bruzzese JM, Hughes TL. The impact of positive school climate on suicidality and mental health among LGBTQ adolescents: a systematic review. J Sch Nurs 2021;37:75–86. 10.1177/1059840520970847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Averett P, Nalavany B, Ryan S. An evaluation of gay/lesbian and heterosexual adoption. Adoption Quarterly 2009;12:129–51. 10.1080/10926750903313278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farr RH, Forssell SL, Patterson CJ. Parenting and child development in adoptive families: does parental sexual orientation matter? Appl Develop Sci 2010;14:164–78. 10.1080/10888691.2010.500958 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldberg AE, Smith JZ. Parent-school relationships and young adopted children’s psychological adjustment in lesbian-, gay-, and heterosexual-parent families. Early Childhood Res Quart 2017;40:174–87. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baiocco R, Carone N, Ioverno S, et al. Same-Sex and different-sex parent families in Italy: is parents’ sexual orientation associated with child health outcomes and parental dimensions? J Dev Behav Pediatr 2018;39:555–63. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bos H, Sandfort TGM. Children’s gender identity in lesbian and heterosexual two-parent families. Sex Roles 2010;62:114–26. 10.1007/s11199-009-9704-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bos H, van Gelderen L, Gartrell N. Lesbian and heterosexual two-parent families: adolescent–parent relationship quality and adolescent well-being. J Child Fam Stud 2015;24:1031–46. 10.1007/s10826-014-9913-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bos HMW, van Balen F, van den Boom DC. Child adjustment and parenting in planned lesbian-parent families. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2007;77:38–48. 10.1037/0002-9432.77.1.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bos HMW, Kuyper L, Gartrell NK. A population-based comparison of female and male same-sex parent and different-sex parent households. Fam Process 2018;57:148–64. 10.1111/famp.12278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gartrell N, Bos H. Us national longitudinal lesbian family study: psychological adjustment of 17-year-old adolescents. Pediatrics 2010;126:28–36. 10.1542/peds.2009-3153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldberg AE, Garcia R. Community characteristics, victimization, and psychological adjustment among school-aged adopted children with lesbian, gay, and heterosexual parents. Front Psychol 2020;11:372. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golombok S, Mellish L, Jennings S, et al. Adoptive gay father families: parent-child relationships and children’s psychological adjustment. Child Dev 2014;85:456–68. 10.1111/cdev.12155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McConnachie AL, Ayed N, Foley S, et al. Adoptive gay father families: a longitudinal study of children’s adjustment at early adolescence. Child Dev 2021;92:425–43. 10.1111/cdev.13442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reczek C, Spiker R, Liu H, et al. Family structure and child health: does the sex composition of parents matter? Demography 2016;53:1605–30. 10.1007/s13524-016-0501-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crouch SR, Waters E, McNair R, et al. Parent-reported measures of child health and wellbeing in same-sex parent families: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2014;14:635. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sullins D. Emotional problems among children with same-sex parents: difference by definition. BJESBS 2015;7:99–120. 10.9734/BJESBS/2015/15823 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bos HMW, Knox JR, van Rijn-van Gelderen L, et al. Same-Sex and different-sex parent households and child health outcomes: findings from the National survey of children’s health. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2016;37:179–87. 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carnaghi A, Anderson J, Bianchi M. On the origin of beliefs about the sexual orientation and gender-role development of children raised by gay-male and heterosexual parents: an Italian study. Men and Masculinities 2020;23:636–60. 10.1177/1097184X18775462 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldberg AE, Garcia RL. Gender-typed behavior over time in children with lesbian, gay, and heterosexual parents. J Fam Psychol 2016;30:854–65. 10.1037/fam0000226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allen DW. High school graduation rates among children of same-sex households. Rev Econ Household 2013;11:635–58. 10.1007/s11150-013-9220-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boertien D, Bernardi F. Same-Sex parents and children’s school progress: an association that disappeared over time. Demography 2019;56:477–501. 10.1007/s13524-018-0759-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kabátek J, Perales F. Academic achievement of children in same- and different-sex-parented families: a population-level analysis of linked administrative data from the Netherlands. Demography 2021;58:393–418. 10.1215/00703370-8994569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watkins CS. School progress among children of same-sex couples. Demography 2018;55:799–821. 10.1007/s13524-018-0678-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farr RH, Vázquez CP. Stigma experiences, mental health, perceived parenting competence, and parent-child relationships among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual adoptive parents in the united states. Front Psychol 2020;11:445. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Rijn-van Gelderen L, Bos HWM, Jorgensen TD, et al. Wellbeing of gay fathers with children born through surrogacy: a comparison with lesbian-mother families and heterosexual IVF parent families. Hum Reprod 2018;33:101–8. 10.1093/humrep/dex339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Farr RH. Does parental sexual orientation matter? A longitudinal follow-up of adoptive families with school-age children. Dev Psychol 2017;53:252–64. 10.1037/dev0000228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farr RH, Patterson CJ. Coparenting among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual couples: associations with adopted children’s outcomes. Child Dev 2013;84:1226–40. 10.1111/cdev.12046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldberg AE, Kinkler LA, Moyer AM, et al. Intimate relationship challenges in early parenthood among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual couples adopting via the child welfare system. Prof Psychol Res Pr 2014;45:221–30. 10.1037/a0037443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goldberg A, Moyer AM, Kinkler LA, et al. “When yo’’re sitting on the fence, hop’s the hardest part”: challenges and experiences of heterosexual and same-sex couples adopting through the child welfare system. Adopt Q 2012;15:288–315. 10.1080/10926755.2012.731032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Solomon SE, Rothblum ED, Balsam KF. Pioneers in partnership: lesbian and gay male couples in civil unions compared with those not in civil unions and married heterosexual siblings. J Fam Psychol 2004;18:275–86. 10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goldberg AE, Smith JZ. Preschool selection considerations and experiences of school mistreatment among lesbian, gay, and heterosexual adoptive parents. Early Child Res Q 2014;29:64–75. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goldberg AE, Black KA, Manley MH, et al. We told them that we are both really involved parents’: sexual minority and heterosexual adoptive parents’ engagement in school communities. Gender and Education 2017;29:614–31. 10.1080/09540253.2017.1296114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patterson CJ. Parents’ sexual orientation and children’s development. Child Dev Perspect 2017;11:45–9. 10.1111/cdep.12207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tornello SL, Farr RH, Patterson CJ. Predictors of parenting stress among gay adoptive fathers in the United States. J Fam Psychol 2011;25:591–600. 10.1037/a0024480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goldberg AE, Smith JZ. Stigma, social context, and mental health: lesbian and gay couples across the transition to adoptive parenthood. J Couns Psychol 2011;58:139–50. 10.1037/a0021684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Palacios J, Brodzinsky D. Review: adoption research: trends, topics, outcomes. Int J Behav Develop 2010;34:270–84. 10.1177/0165025410362837 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lamb ME. Mothers, fathers, families, and circumstances: factors affecting children’s adjustment. App Develop Sci 2012;16:98–111. 10.1080/10888691.2012.667344 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fedewa AL, Clark TP. Parent practices and home-school partnerships: a differential effect for children with same-sex coupled parents? J GLBT Fam Stud 2009;5:312–39. 10.1080/15504280903263736 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosenfeld MJ. Nontraditional families and childhood progress through school. Demography 2013;50:963–9. 10.1007/s13524-012-0170-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gartrell N, Banks A, Reed N, et al. The National lesbian family study: 3. interviews with mothers of five-year-olds. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2000;70:542–8. 10.1037/h0087823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gartrell N, Deck A, Rodas C, et al. The National lesbian family study: 4. interviews with the 10-year-old children. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2005;75:518–24. 10.1037/0002-9432.75.4.518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gartrell N, Hamilton J, Banks A, et al. The National lesbian family study: 1. interviews with prospective mothers. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1996;66:272–81. 10.1037/h0080178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goldberg AE, Smith JZ, Kashy DA. Preadoptive factors predicting lesbian, gay, and heterosexual couples’ relationship quality across the transition to adoptive parenthood. J Fam Psychol 2010;24:221–32. 10.1037/a0019615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lavner JA, Waterman J, Peplau LA. Parent adjustment over time in gay, lesbian, and heterosexual parent families adopting from foster care. Am J Orthopsychiatry 2014;84:46–53. 10.1037/h0098853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weber S. A stigma identification framework for family nurses working with parents who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgendered and their families. J Fam Nurs 2010;16:378–93. 10.1177/1074840710384999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chbat M, Côté I, Pagé G, et al. Intersectional analysis of the life course of LGBTQ+ parent families in Québec: partial and homonormative inclusion. J Homosex 2022;2022:1–22. 10.1080/00918369.2022.2049025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Manley MH, Ross LE. What do we now know about bisexual parenting? A continuing call for research. In: Goldberg AE, Allen KR, eds. LGBTQ-parent families: innovations in research and implications for practice. Cham: Springer, 2020: 65–83. Available: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-35610-1_4 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pfeffer CA, Jones KB. Transgender-parent families. In: Goldberg AE, Allen KR, eds. LGBTQ-parent families: innovations in research and implications for practice. Cham: Springer, 2020: 199–214. Available: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-35610-1_12 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ross LE, Goldberg AE, Tarasoff LA, et al. Perceptions of partner support among pregnant plurisexual women: A qualitative study. Sex Relation Ther 2018;33:59–78. 10.1080/14681994.2017.1419562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Widiss DA. Legal recognition of same-sex relationships: new possibilities for research on the role of marriage law in household labor allocation. J Fam Theory Rev 2016;8:10–29. 10.1111/jftr.12123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data