Abstract

Objectives

To assess access children with HIV have to comprehensive HIV care services, to longitudinally evaluate the implementation and scale-up of services, and to use site services and clinical cohort data to explore whether access to these services influences retention in care.

Methods

A cross-sectional standardised survey was completed in 2014–2015 by sites providing paediatric HIV care across regions of the International Epidemiology Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) consortium. We developed a comprehensiveness score based on the WHO’s nine categories of essential services to categorise sites as ‘low’ (0–5), ‘medium’, (6–7) or ‘high’ (8–9). When available, comprehensiveness scores were compared with scores from a 2009 survey. We used patient-level data with site services to investigate the relationship between the comprehensiveness of services and retention.

Results

Survey data from 174 IeDEA sites in 32 countries were analysed. Of the WHO essential services, sites were most likely to offer antiretroviral therapy (ART) provision and counselling (n=173; 99%), co-trimoxazole prophylaxis (168; 97%), prevention of perinatal transmission services (167; 96%), outreach for patient engagement and follow-up (166; 95%), CD4 cell count testing (126; 88%), tuberculosis screening (151; 87%) and select immunisation services (126; 72%). Sites were less likely to offer nutrition/food support (97; 56%), viral load testing (99; 69%) and HIV counselling and testing (69; 40%). 10% of sites rated ‘low’, 59% ‘medium’ and 31% ‘high’ in the comprehensiveness score. The mean comprehensiveness of services score increased significantly from 5.6 in 2009 to 7.3 in 2014 (p<0.001; n=30). Patient-level analysis of lost to follow-up after ART initiation estimated the hazard was highest in sites rated ‘low’ and lowest in sites rated ‘high’.

Conclusion

This global assessment suggests the potential care impact of scaling-up and sustaining comprehensive paediatric HIV services. Meeting recommendations for comprehensive HIV services should remain a global priority.

Keywords: Health policy, HIV & AIDS, International health services, PAEDIATRICS

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This study fills a critical gap in the literature, given the lack of similar assessments of the trend and impact of changes in paediatric HIV care services across a broad global geography.

Though we had a limited response rate of 53%, this study provides an assessment across the broad range of actual paediatric HIV care practice globally, with comprehensive details.

A comparison of site-level assessments and patient-level data reveals the clinical impact of a lack of comprehensive services for children living with HIV.

The data for this study were collected from September 2014 to January 2015 and may not represent the current state of HIV paediatric care; however, these are still some of the only data on this topic available.

Limitations in the available patient-level data meant that certain analyses were only done for the East Africa region.

Introduction

In 2020, there were an estimated 1.7 million children with HIV between the ages of 0 and 15 years.1 New infections among children declined by 53% from 2010 to 2020, with most new infections occurring in African countries. Access to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART), however, remains an important challenge for this population. In 2020, only 54% of children with HIV globally were accessing ART, which is substantially lower than the percentage of adults with HIV accessing ART (74%).1 Barriers to scale-up of paediatric treatment include inadequate access to early infant diagnosis, lack of provider experience in delivering paediatric care, limited availability of paediatric antiretroviral formulations and weak healthcare infrastructure, but there are few data on the extent to which these specific paediatric HIV services are available globally.2–5 For children with HIV who are in care, losses to follow-up from care and deaths while in care appear to remain high, though these rates are difficult to accurately report.6 7 It is important to document the capacity of HIV care and treatment programmes to deliver comprehensive, integrated HIV prevention, care and treatment services to children across multiple regions in order to identify gaps in services and target resources appropriately.8–12

Data on clinical capacity and services are also needed to ensure that paediatric services continue to improve their quality and comprehensiveness, in line with global guidelines for the care of children living with and exposed to HIV. An assessment of global paediatric HIV care capacity at sites of the International Epidemiology Databases Evaluating AIDS (IeDEA) consortium from 2009 revealed that only 38% of sites had capacity for routine viral load monitoring, and that 89% had direct access to infant HIV DNA PCR testing.13 Over time, the WHO has continued to revise its guidelines for the care of children with HIV, including initiation of ART for all children under 5 years of age, initiation of ART for all children >5 years of age with a CD4 cell count <500 cells/µL, routine viral load monitoring for all patients,14 and then the expansion to recommend treatment of all children and adults with HIV with lifelong ART regardless of immunologic status.15 The ultimate goal of these guidelines is to improve paediatric morbidity and mortality related to HIV through expanded prevention, treatment and monitoring services.

Examining whether and how the availability of more comprehensive HIV prevention and treatment services improve patient-level paediatric outcomes are important steps in ensuring that global care services ultimately improve the care of children. Here, we draw on site-level survey assessments administered to a consortium of HIV care programmes worldwide to assess the extent to which children with HIV have access to comprehensive HIV care services, to evaluate the implementation and scale-up of these services over time, and to compare these survey findings with clinical cohort data to explore whether access to these services influences the retention in care of children with HIV.

Methods

Population

The IeDEA research consortium was established in 2005 with support from the US National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases to develop a global resource of clinical data from people with HIV (www.iedea.org). IeDEA collects data from seven international regional data centres: the Asia-Pacific, CCASAnet (encompassing the Caribbean Central and South America), Central Africa, East Africa, NA-ACCORD (encompassing Canada and the USA), Southern Africa, and West Africa. Each IeDEA region collaborates with clinical sites to define key variables and harmonise large datasets to address research questions around the impact of the global ART roll-out on HIV-related clinical services and outcomes. Paediatric clinical and ART resources across the Africa and Asia-based HIV care sites were previously evaluated in 2009.13

Study design and data collection

We surveyed the IeDEA sites that provide HIV treatment and prevention services to children, in any configuration of stand-alone paediatric services or combined care for children and adults. The standardised site assessment tool was adapted from the site assessment survey done in 2009.13 Study data were collected and managed using a web-based survey on the Research Electronic Data Capture platform (www.project-redcap.org) hosted at the Vanderbilt Institute for Global Health at Vanderbilt University. Site clinical directors or managers were asked to complete the survey, providing information about the sites’ physical and clinical characteristics and capacity to deliver WHO-recommended paediatric HIV prevention, care and treatment services. In 2009, 26 sites in Asia Pacific, 16 sites in Central Africa, 52 sites in East Africa, 19 sites in Southern Africa and 21 sites in Western Africa were surveyed (N=143). In 2014, an additional 31 sites were surveyed (see table 1 for regional breakdown). Between 2009 and 2014, 30 sites both (1) provided care for children and/or adolescents with HIV and (2) had consistent site IDs between 2009 and 2014 and and therefore these sites’ survey findings were used to compare care services.

Table 1.

2014 survey site characteristics by International Epidemiology Databases to Evaluate AIDS region (n=174 sites)*

| Asia-Pacific (n=16) |

CCASAnet (n=7) |

Central Africa (n=17) |

East Africa (n=34) |

Southern Africa (n=88) |

West Africa (n=12) |

Total (n=174) |

||

| No of paediatric and adolescents in care, 2014 | 70 (2 sites) | 611 (7 sites) | 1748 (13 sites) | 8165 (33 sites) | 3113 (12 sites) | 3076 (10 sites) | 16 783 (77 sites) | |

| Age at enrolment for patients in care in 2014 | 0 to <5 | 47 (67.1) | 356 (58.3) | 567 (32.4) | 3519 (43.1) | 1934 (62.1) | 1666 (54.2) | 8089 (48.2) |

| 5 to <10 | 17 (24.3) | 150 (24.5) | 628 (35.9) | 2844 (34.8) | 685 (22.0) | 989 (32.2) | 5313 (31.7) | |

| 10 to <15 | 6 (8.6) | 89 (14.6) | 461 (26.4) | 1514 (18.5) | 427 (13.7) | 389 (12.6) | 2886 (17.2) | |

| 15 to 16 | 0 (0.0) | 16 (2.6) | 92 (5.3) | 288 (3.5) | 67 (2.2) | 32 (1.0) | 495 (2.9) | |

| Patient population | Children only | 16 (100.0) | 3 (42.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.4) | 10 (83.3) | 32 (18.4) |

| Both children and adults | 0 (0.0) | 4 (57.1) | 17 (100.0) | 34 (100.0) | 85 (96.6) | 2 (16.7) | 142 (81.6) | |

| Site location† | Urban | 0 (0.0) | 7 (100.0) | 16 (94.1) | 9 (26.5) | 32 (36.4) | 3 (25.0) | 67 (38.5) |

| Mostly urban | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (23.5) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (50.0) | 14 (8.0) | |

| Mostly rural | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (35.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (6.9) | |

| Rural | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (14.7) | 51 (58.0) | 0 (0.0) | 56 (32.2) | |

| Other/mixed urban–rural | 16 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (5.7) | 3 (25.0) | 25 (14.4) | |

| Type of facility | Public | 15 (93.8) | 6 (85.7) | 16 (94.1) | 31 (91.2) | 83 (94.3) | 11 (91.7) | 162 (93.1) |

| Private | 1 (6.3) | 1 (14.3) | 1 (5.9) | 3 (8.8) | 5 (5.7) | 1 (8.3) | 12 (6.9) | |

| Level of facility | Primary | 2 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (38.2) | 54 (61.4) | 1 (8.3) | 70 (40.2) |

| Secondary | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (47.1) | 25 (28.4) | 2 (16.7) | 43 (24.7) | |

| Tertiary | 14 (87.5) | 7 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) | 5 (14.7) | 9 (10.2) | 7 (58.3) | 59 (33.9) | |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (16.7) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Academic affiliation | No | 4 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (82.4) | 22 (64.7) | 77 (87.5) | 4 (33.3) | 121 (69.5) |

| Yes | 12 (75.0) | 7 (100.0) | 3 (17.6) | 12 (35.3) | 10 (11.4) | 8 (66.7) | 52 (29.9) | |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Paediatrician on site | Available every day clinic open | 15 (93.8) | 7 (100.0) | 6 (35.3) | 2 (5.9) | 5 (5.7) | 10 (83.3) | 45 (25.9) |

| Available some days | 1 (6.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (23.5) | 12 (35.3) | 7 (8.0) | 1 (8.3) | 25 (14.4) | |

| Not available | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (41.2) | 20 (58.8) | 76 (86.4) | 1 (8.3) | 104 (59.8) |

*Findings other than ‘Paediatric and Adolescents in Care’ are listed as n (%).

†Urban=officially designated to be city with city administration and political bodies; mostly urban=big and small towns, periurban areas, growth points, mining communities; mostly rural=large and small scale commercial farming areas; rural=subsistence farming areas; other/mixed urban–rural=for example, small town, periurban area, growth points, mining community).

We created a measure of comprehensiveness of paediatric care services based on the WHO’s nine categories of essential services: (1) ART access with psychosocial and adherence counselling; (2) nutrition or food support or counselling; (3) prevention of perinatal transmission services, including medication; (4) CD4 cell count and HIV viral load testing; (5) tuberculosis screening; (6) counselling and testing for HIV, (7) co-trimoxazole prophylaxis, (8) immunisation access for select vaccine-preventable diseases (hepatitis B, pneumococcal, influenza vaccine or yellow fever vaccines) and (9) outreach for patient engagement and follow-up.16 In calculating the comprehensiveness score, one point was awarded for each service adequately provided by the site, with a total score range between 0 (no services offered) and 9 (all services offered). Sites were then categorised into ‘low’ (0–5), ‘medium’6 7 or ‘high’8 9 service levels, as was done in prior global site assessment evaluations, from similar site assessment surveys done in 2009.13

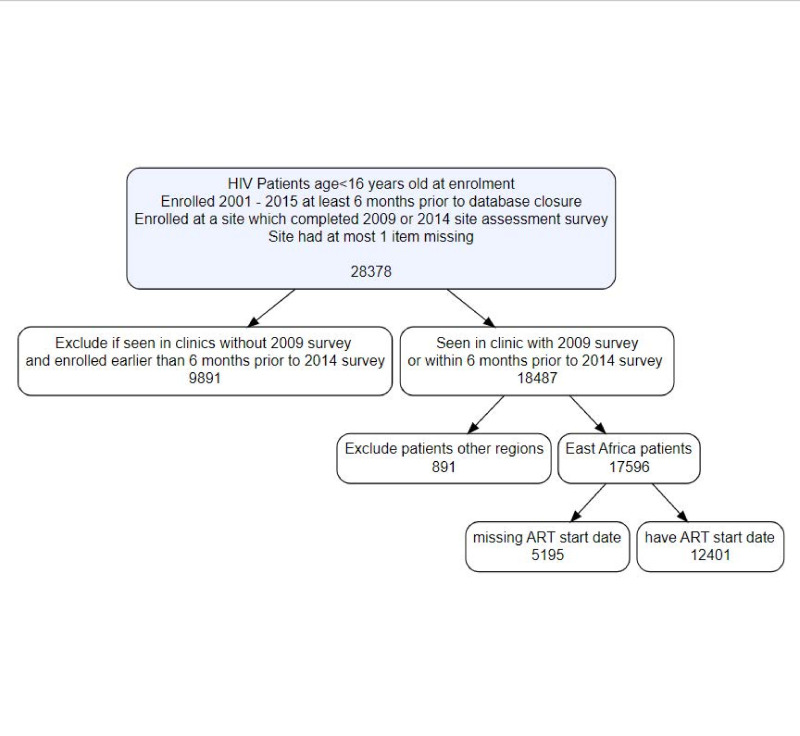

In order to investigate the relationship between the comprehensiveness of available services and retention in care, patient-level data were also extracted from the IeDEA global cohort database. Patient inclusion criteria were: (1) documented HIV infection; (2) age <16 years of age at enrolment; (3) enrolled into care in 2001 or later at least 6 months prior to site-specific database closure and (4) either enrolled at a site which completed the 2009 survey or enrolled within 6 months of the 2014 site assessment survey. Due to high amount of missing data for items from site surveys, only patients seen at sites with missing data for at most 1 item (n=62 sites) were included in the analysis (n=28 378). The sample was further restricted by including only patients enrolled within 6 months of the 2014 survey if they were affiliated with sites only completing that round of surveys (n=18 487). Since the resulting deidentified patient-level dataset was overwhelmingly from East Africa (n=17 596 (95.2%)) and less than 5% of the sample consisted of patients from the IeDEA regions of Asia-Pacific, CCASAnet, Central Africa and West Africa, we selected only sites in East Africa (52 sites) for the patient-level analyses. Then, the dataset was further restricted to patients with non-missing ART start dates (n=12 401 in 35 centres) (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of inclusion criteria for patient level analysis. ART, antiretroviral therapy.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute). Descriptive analyses of the 2014 survey were performed, with site characteristics stratified by region. We were able to link data for 30 clinics which responded to both the 2009 and 2014 IeDEA site assessments surveys and analysed differences in the mean comprehensive of services scores by using paired t-tests.

The analysed patient-level outcome of interest was time from ART start to lost to programme due to either death, transfer or lost to follow-up. Lost to follow-up was defined as no record of death or transfer and no visit between the date of the last clinic visit attended and 6 months or more of database closure. This was a competing risk model with the two competing events being death and lost to follow-up and being transferred coded as censored. Bivariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess the association between comprehensive care category (obtained from the 2014 or earlier 2009 surveys) and lost to programme. A multivariable Cox proportional hazards model which included clinically important patient-level variables—age at ART start (categorical, 0 to <5 years, 5 to <10, 10 to<15, 15 to 16); categorical immune status at ART start as defined by the WHO, based on age and CD4 cell count or percentage depending on age, WHO clinical stage at enrolment and clinic location (urban, mostly urban, mostly rural or rural)—was used to investigate the relationship between level of comprehensiveness of services (low, medium, high) and patient retention in care. HRs and 95% CIs were reported. As a sensitivity analysis, the model was refit using data obtained from multiple imputation for missing values for CD4 percentage (24.0%), WHO clinical stage (13.8%) and age at ART start (0.1%) using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method.17

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design or conduct of our research. In the East Africa region, briefings on the findings were done in clinics to patients, including both study participants and non-participants.

Results

All 536 sites providing HIV care in the IeDEA global regions received the survey, and 287 (53.5%) sites completed the survey between September 2014 and January 2015. Out of those 287 sites, 174 (61%) provided paediatric care. Site characteristics by IeDEA region are shown in table 1. Overall, most sites providing paediatric HIV care (82%) saw both children and adult patients, including almost 17 000 children with HIV. The majority of the sites were in African countries, with 88 sites (51%) from Southern Africa, 34 sites (20%) from East Africa, 17 sites (10%) from Central Africa, 16 sites (9%) from the Asia-Pacific, 12 sites (7%) from West Africa and 7 sites (4%) from CCASAnet. Most of the care sites were located in urban (39%) or mostly urban (8%) settings, and almost all were public facilities (93%). Overall, the HIV care sites were well distributed across different levels of healthcare services; 40% were primary care sites, 25% were secondary care sites and 34% were tertiary care sites. However, the participating sites from the Asia-Pacific, CCASAnet and Central Africa regions were almost exclusively tertiary facilities.

Site-specific characteristics

Most sites (60%) reported that paediatricians were not available, although this varied significantly by region. A majority of sites within the Asia Pacific, CCASAnet and West Africa regions had a paediatrician either available all days or some days, while most sites in the East and Southern Africa regions (which had the largest paediatric patient populations) reported that a paediatrician was not available on any day.

Out of the nine essential services, we found that sites were most likely to offer ART access (99% of sites), co-trimoxazole prophylaxis (97%), comprehensive prevention of perinatal transmission services (96%), outreach services for patient follow-up (95%), tuberculosis screening (87%) and immunisation services (72%) (table 2). During this time period, providing either or both CD4 cell count and viral load testing was considered an essential service, and 88% of sites report CD4 cell count testing and 69% reported viral load testing. Sites were less likely to report offering nutrition counselling or food support (56%), and HIV counselling and testing (40%). The median comprehensive care score was 7 (IQR, 6–7). Among the 174 sites, 18 sites (10%) offered a ‘low’ level of services, 103 sites (59%) offered a ‘medium’ level of services, and 53 (31%) offered a ‘high’ level of services. These ‘high’ levels of services or more comprehensive services were clustered at sites in Asia-Pacific (56% of sites in the region), CCASAnet (43%) and East Africa (44%).

Table 2.

2014 survey site capacity and comprehensiveness of services score by IeDEA region (n=174 sites)*

| WHO essential services | Asia-Pacific (n=16) |

CCASAnet (n=7) |

Central Africa (n=17) |

East Africa (n=34) |

Southern Africa (n=88) |

West Africa (n=12) |

Total (n=174) |

|

| ART access with counselling | 16 (100.0) | 6 (85.7) | 17 (100.0) | 34 (100.0) | 88 (100.0) | 12 (100.0) | 173 (99.4) | |

| Nutrition | 12 (75.0) | 4 (57.1) | 4 (23.5) | 25 (73.5) | 45 (51.1) | 7 (58.3) | 97 (55.7) | |

| Prevention of perinatal transmission services | 13 (81.3) | 7 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) | 34 (100.0) | 87 (98.9) | 9 (75.0) | 167 (96.0) | |

| CD4 testing and/or viral load testing | CD4 | 15 (93.8) | 5 (71.4) | 13 (81.3) | 19 (65.5) | 62 (96.9) | 12 (100.0) | 126 (87.5) |

| Viral load | 11 (68.8) | 4 (57.1) | 12 (75.0) | 26 (89.7) | 37 (57.8) | 9 (75.0) | 99 (68.8) | |

| TB screening | 16 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 12 (70.6) | 32 (94.1) | 77 (87.5) | 7 (58.3) | 151 (86.8) | |

| HIV counselling and testing | 11 (68.8) | 6 (85.7) | 4 (23.5) | 16 (47.1) | 26 (29.5) | 6 (50.0) | 69 (39.7) | |

| Co-trimoxazole | 16 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) | 31 (91.2) | 85 (96.6) | 12 (100.0) | 168 (96.6) | |

| Immunisations | 13 (81.3) | 7 (100.0) | 12 (70.6) | 24 (70.6) | 65 (73.9) | 5 (41.7) | 126 (72.4) | |

| Outreach | 14 (87.5) | 4 (57.1) | 15 (88.2) | 34 (100.0) | 88 (100.0) | 11 (91.7) | 166 (95.4) | |

| Comprehensiveness score | Low (0–5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (29.4) | 2 (5.9) | 8 (9.1) | 3 (25.0) | 18 (10.3) |

| Medium (6–7) | 7 (43.8) | 4 (57.1) | 10 (58.8) | 17 (50.0) | 58 (65.9) | 7 (58.3) | 103 (59.2) | |

| High (8–9) | 9 (56.3) | 3 (42.9) | 2 (11.8) | 15 (44.1) | 22 (25.0) | 2 (16.7) | 53 (30.5) |

*Findings are listed as n (%).

ART, antiretroviral therapy; IeDEA, International Epidemiology Databases to Evaluate AIDS; TB, tuberculosis.

From among paediatric care sites which responded to the 2009 survey (n=143) and 2014 survey (n=714), we were able to link data for 30 sites: East Africa (26 sites), Asia Pacific (3 sites) and Southern Africa (1 site). The mean comprehensiveness of services score increased significantly from 5.6 (SD, 1.4) in 2009 to 7.3 (SD 1.4) in 2014 (p<0.001) (table 3). A greater proportion of sites reported offering services in the 2014 survey compared with the 2009 survey for each of the nine essential services except for CD4 cell count testing and immunisation; 80% of sites reported CD4 cell count testing in 2009 and only 60% reported testing in 2014. Similarly, 80% of sites in 2009 reported offering immunisation services, but only 70% of these same sites reported offered immunisations in 2014. From 2009 to 2014, we found that the largest increases were for nutrition services (13%–80%), viral load testing (7%–83%), HIV counselling and testing (13%–43%) and outreach (70%–100%).

Table 3.

Changes in site capacity and comprehensiveness of services from 2009 to 2014 (n=30)

| Site assessment 1.0 (2009) |

Site assessment 2.0 (2014) |

||

| Comprehensiveness score | Mean±SD | 5.571±1.372 | 7.333±1.373* |

| ART access with counselling | N (%) | 24 (80.0) | 30 (100.0) |

| Nutrition | 4 (13.3) | 24 (80.0) | |

| Prevention of perinatal transmission services | 26 (86.7) | 30 (100.0) | |

| CD4 testing | 24 (80.0) | 18 (60.0) | |

| Viral load testing | 2 (6.7) | 25 (83.3) | |

| TB screening | 25 (83.3) | 28 (93.3) | |

| HIV counselling and testing | 4 (13.3) | 13 (43.3) | |

| Co-trimoxazole | 26 (86.7) | 27 (90.0) | |

| Immunisations | 24 (80.0) | 21 (70.0) | |

| Outreach | 21 (70.0) | 30 (100.0) |

*There was a statistically significant increase in the mean comprehensive care score from 2009 to 2014 among paediatric sites with at most one care item missing. Differences in mean comprehensiveness scores were tested by paired t-test.

TB, tuberculosis.

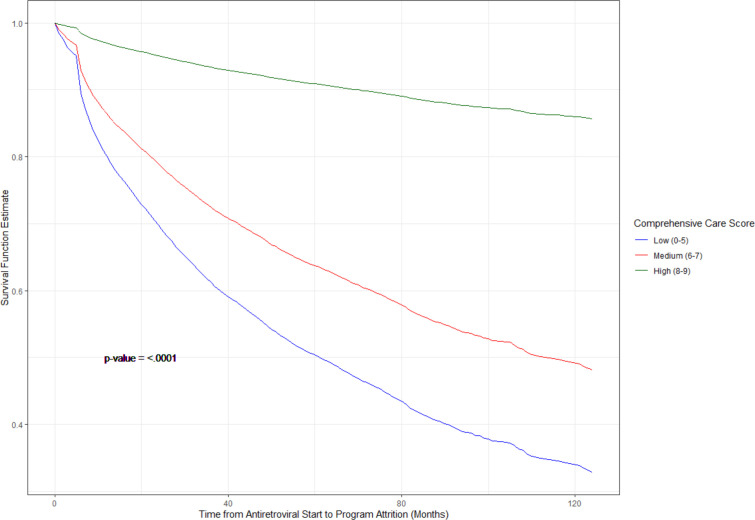

Patient-level analyses

A total of 12 401 children at 35 sites in the East Africa region were included in the patient-level analysis, of which 192 (1%) were at clinics reporting a ‘low’ level of services, 10 386 (84%) were at clinics reporting a ‘medium’ level of services, and 1823 (15%) were at clinics reporting a ‘high’ level of services. Care classification was based on either the 2014 or 2009 surveys. Mean age at enrolment was 5.9 years, with median age of 5 years and range from 0 to 16 years. The probability of lost to follow-up after ART initiation was highest in clinics with a ‘low’ level of services and lowest in clinics with a ‘high’ level of services (figure 2). HRs from bivariate and multiple regression Cox proportional hazard models are presented in table 4. In multivariable Cox proportional hazard models, compared with children in care at clinics providing a ‘low’ level of services, children in care at clinics providing ‘medium’ and ‘high’ levels of services had hazard ratios of lost to follow-up of 0.58 (95% CI 0.47 to 0.72) and 0.12 (95% CI 0.07 to 0.23), respectively, adjusting for age at ART start, gender, immunologic status, WHO clinical stage at enrolment and clinic location. Results from models using imputation of missing covariate data were not substantially different from what is presented here.

Figure 2.

Predicted survival of time from antiretroviral therapy initiation to lost to follow-up by site-level comprehensiveness of services among 12 401 children in East Africa IeDEA enrolled in care from 2001 to 2014. IeDEA, International Epidemiology Databases to Evaluate AIDS.

Table 4.

HRs from Cox proportional hazard models of time to loss to programme

| Level | Bivariate models | Multiple regression | |||||||

| HR | 95% CI | Overall test | P value | HR | 95% CI | Overall test | P value | ||

| Age at ART start | 0 to <1 | 1.715 | (1.460 to 2.015) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 2.298 | (1.530 to 3.452) | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| 1 to <2 | 1.388 | (1.236 to 1.559) | <0.0001 | 1.413 | (1.139 to 1.753) | 0.0017 | |||

| 2 to <5 | reference | reference | |||||||

| 5 to <7 | 0.906 | (0.820 to 1.002) | 0.0541 | 1.042 | (0.907 to 1.197) | 0.5605 | |||

| 7 to <10 | 0.857 | (0.780 to 0.941) | 0.0012 | 0.989 | (0.866 to 1.130) | 0.8700 | |||

| 10 to <13 | 0.941 | (0.851 to 1.040) | 0.2302 | 1.064 | (0.926 to 1.222) | 0.3822 | |||

| 13 to <16 | 1.186 | (1.067 to 1.318) | 0.0016 | 1.309 | (1.132 to 1.514) | 0.0003 | |||

| 16 to <23 | 1.495 | (1.258 to 1.777) | <0.0001 | 1.716 | (1.400 to 2.103) | <0.0001 | |||

| Comprehensive Care Score | (4 to 5) | reference | <0.0001 | reference | <0.0001 | ||||

| (6 to 7) | 0.657 | (0.562 to 0.768) | <0.0001 | 0.584 | (0.472 to 0.722) | <0.0001 | |||

| (8 to 9) | 0.139 | (0.084 to 0.230) | <0.0001 | 0.124 | (0.066 to 0.233) | <0.0001 | |||

| Gender | Female | 1.026 | (0.966 to 1.089) | 0.4056 | 0.4056 | 1.022 | (0.949 to 1.100) | 0.5679 | 0.5679 |

| Male | reference | reference | |||||||

| Immune status | Not significant | reference | <0.0001 | reference | <0.0001 | ||||

| Advanced immunosuppression | 1.026 | (0.899 to 1.172) | 0.7029 | 0.943 | (0.818 to 1.086) | 0.4133 | |||

| Mild immunosuppression | 0.915 | (0.781 to 1.072) | 0.2742 | 0.901 | (0.763 to 1.064) | 0.2183 | |||

| Severe immunosuppression | 1.227 | (1.104 to 1.365) | 0.0002 | 1.141 | (1.019 to 1.278) | 0.0220 | |||

| Facility location | Mostly rural | 0.663 | (0.607 to 0.724) | <0.0001 | 0.721 | (0.636 to 0.816) | <0.0001 | ||

| Mostly urban | 0.571 | (0.524 to 0.623) | <0.0001 | 0.575 | (0.508 to 0.650) | <0.0001 | |||

| Rural | 0.480 | (0.411 to 0.560) | <0.0001 | 0.440 | (0.354 to 0.546) | <0.0001 | |||

| Urban | reference | reference | |||||||

| WHO/CDC stage at ART start | 1 | reference | reference | ||||||

| 2 | 1.104 | (1.035 to 1.177) | 0.0025 | 0.0025 | 1.095 | (1.014 to 1.182) | 0.0200 | 0.0200 | |

ART, antiretroviral therapy; CDC, The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Discussion

With only 54% of children with HIV on treatment globally in 2021 and 40% of children with HIV virally suppressed, it is essential that we understand the capacity of global HIV care and treatment sites to provide comprehensive care to children.1 In this evaluation of a broad range of global care sites providing services to children with HIV, we noted significant improvement in the sites’ provision of essential HIV care and prevention services for children and pregnant people between assessments done in 2009 and 2014. Access to ART and provision of prevention of perinatal transmission services increased substantially in the 30 sites with both assessments—providing the necessary backdrop to achieving an AIDS-free generation through both prevention and treatment. Moreover, there was a dramatic scale-up in access to routine viral load monitoring (from 6.7% to 83.3%), reflecting success in policy shifts to improve access to viral load monitoring and supporting the global efforts to achieve viral suppression. As routine viral load monitoring increased, these data already showed a parallel drop in CD4 cell count testing services by 2014.

Even though the comprehensiveness of essential paediatric HIV services grew substantially in the 5 years between the assessments, we can still see critical gaps in access to broader services for children and adolescents. While services such as providing nutrition support and counselling for HIV testing generally increased, these services remained absent from many sites. Perhaps even more concerning from a child health perspective, particularly in the face of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, fewer sites reported offering immunisations in the 2014 survey. Addressing potential gaps in access to immunisations for children and adolescents at risk of immune-compromise merits close attention. There is a defined need to catch up on the delayed childhood immunisations missed for 23 million children worldwide related to the COVID-19 pandemic.18 Moreover, many health systems might consider the potential for these care sites to bolster broader coverage of vaccinations for human papillomavirus to prevent cervical cancer, and to provide SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. The urgency in moving more paediatric care sites globally to provide the full range of essential services is also highlighted by the potential clinical impact. Our findings, from analyses performed in East Africa, one of our constituent regions, suggest that sites providing more comprehensive services also have more children with HIV retained in care, which may in turn result in less HIV-related disease and fewer adverse clinical outcomes. These sites may also be those with the most robust resources or sites where care is more accessible. In considering how to expand the range of services available in a health system, attention must also be given to what specific resources are already available to adapt to care expansion and how access to even more basic levels of care might be improved.

There are several limitations to these data. The data were collected from September 2014 to January 2015 and may not represent the current state of HIV paediatric care. On the other hand, these data do highlight the trajectory of HIV care systems as global paediatric HIV treatment guidelines shift. Moreover, our observations fill a critical gap in the literature, given the lack of similar assessments of the trend and impact of changes in paediatric HIV care services across a broad global geography. We are able to show the age distribution by region (table 1), allowing the comprehensive assessment of services to be compared across the range of paediatric care, including for varying definitions of ‘child’, whether those less than 15 years or less than 16 years. The response rate to the survey was low, at 53.5%, which may introduce sampling bias that challenges the representativeness of this sample and thus the generalisability of the findings. Nonetheless, the responses we received to represent a cross-sectional description of services for a range of HIV clinical care sites across a wide swath of resource-limited settings and we believe this still may be one of the most detailed description of the HIV and related care services available for children and adolescents globally. While we acknowledge the potential lack of generalisability of the East Africa observations to the IeDEA Network, particularly outside of African countries, we are less concerned about the same between IeDEA-affiliated sites and their ambient environment in their respective countries or other similar sites in Africa. For example, in other patient-level analyses from global IeDEA, the East Africa IeDEA cohort demographics have been representative of broader African settings, both within and outside of IeDEA19–22 Another concern arises due to shifts in the sites participating in the surveys between 2009 and 2014. Because of this shift, we did not have longitudinal data for all sites, in order to assess changes in the services provided over the 5-year period of the study. Nevertheless, a sufficient number of sites did have complete surveys on both occasions. Moreover, the limited response rate indicated by the estimation that only 53% of sites completed the survey is a conservatively low estimate because some of the sites changed their consortium identifiers in the course of the follow-up, making it impossible to pair their data conclusively. Despite the fact that the longitudinal data were only available for 17% of the sites surveyed in 2014, this is still some of the only data on this topic available within these years. The large number of these sites and the consistency of the longitudinal trends in (increasing) comprehensiveness of HIV-related services, provides a broad look at the state of the global paediatric HIV care in these regions during this period.

Conclusions

As global programmes work to expand the availability and quality of paediatric HIV treatment and prevention services, understanding the capacity of global sites caring for this population to provide services for children and adolescents with HIV can guide targets for improving care access and quality. This global survey of IeDEA cohort sites demonstrates significant gains in the comprehensiveness of HIV treatment and prevention services available for children between 2009 and 2014, while identifying important remaining gaps. Data from the East Africa region further suggest that sites providing a comprehensive array of HIV-related services experience higher retention in care among their clients, compared with sites offering lower levels of the essential services for HIV treatment and prevention. Achieving global treatment success for children and adolescents with HIV and eliminating perinatal transmission of HIV requires that we continue to prioritise strengthening the healthcare systems available for these populations with HIV worldwide.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: RCV, CTY, CWW and KW-K designed and provided scientific oversight for the study. Material preparation and data collection were performed by NKNY, CWW, AE, M-AD, VL, PL, RCdMS, CT, CB-M, OET and MS. CTY led data analysis in collaboration with SO and SB. The first draft of the manuscript was written by RCV. NKNY, CWW, AE, M-AD, VL, PL, RCdMS, CT, CB-M, OET, MS, CTY, KW-K, SO, SB, RM and RCV reviewed and contributed to subsequent versions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. RCV is the guarantor of the study.

Funding: The International Epidemiology Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) is supported by the US National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the Fogarty International Center, and the National Library of Medicine: AsiaPacific, U01AI069907; CCASAnet, U01AI069923; Central Africa, U01AI096299; East Africa, U01AI069911; NAACCORD, U01AI069918; Southern Africa, U01AI069924; West Africa, U01AI069919. Informatics resources are supported by the Harmonist project, R24AI124872.

Disclaimer: This work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of any of the institutions mentioned above.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available on request, following a review process and approval by IeDEA. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. All data requests must be approved by IeDEA.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Due to the large number of participating sites in IeDEA, we are unable to provide all approving IRBs and ethical committees along with this submission at this time. We are able to provide the approvals for the East Africa region, which is the leading and coordinating site for this site assessment: Indiana University Institutional Review Board: - IRB# 1105005574 'Regional East Africa International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) Consortium' and - IRB # 1105005572 'International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA), East Africa: Proposal for Data Extraction and Analysis for the Initial Projects'. The patient-related data presented here are based on retrospective deidentified information collected on a routine basis in sites participating in the IeDEA consortium. These data were approved for use by the local institutional review boards in each of the IeDEA countries included in the analysis and consent requirements were deferred to the local institutional review boards. As the patient-level data were collected from routine patient care, consent was not required. All sites and IeDEA regional coordinating centres also had Institutional Review Board approvals in place permitting the collection of site-level data for the survey.

References

- 1. UNAIDS . UNAIDS global AIDS update: confronting inequalities: lessons for pandemic responses from 40 years of AIDS. Geneva: UNAIDS, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ciaranello AL, Park J-E, Ramirez-Avila L, et al. Early infant HIV-1 diagnosis programs in resource-limited settings: opportunities for improved outcomes and more cost-effective interventions. BMC Med 2011;9:59. 10.1186/1741-7015-9-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hazra R, Siberry GK, Mofenson LM. Growing up with HIV: children, adolescents, and young adults with perinatally acquired HIV infection. Annu Rev Med 2010;61:169–85. 10.1146/annurev.med.050108.151127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Essajee S, Bhairavabhotla R, Penazzato M, et al. Scale-Up of early infant HIV diagnosis and improving access to pediatric HIV care in global plan countries: past and future perspectives. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;75 Suppl 1:S51–8. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Penazzato M, Amzel A, Abrams EJ, et al. Pediatric treatment scale-up: the unfinished agenda of the global plan. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;75 Suppl 1:S59–65. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Phelps BR, Ahmed S, Amzel A, et al. Linkage, initiation and retention of children in the antiretroviral therapy cascade: an overview. AIDS 2013;27 Suppl 2:S207–13. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mahy M, Penazzato M, Ciaranello A, et al. Improving estimates of children living with HIV from the spectrum AIDS impact model. AIDS 2017;31 Suppl 1:S13–22. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nash D, Wu Y, Elul B, et al. Program-level and contextual-level determinants of low-median CD4+ cell count in cohorts of persons initiating art in eight sub-Saharan African countries. AIDS 2011;25:1523–33. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834811b2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lamb MR, El-Sadr WM, Geng E, et al. Association of adherence support and outreach services with total attrition, loss to follow-up, and death among art patients in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One 2012;7:e38443. 10.1371/journal.pone.0038443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nash D, Elul B, Rabkin M, et al. Strategies for more effective monitoring and evaluation systems in HIV programmatic scale-up in resource-limited settings: implications for health systems strengthening. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;52 Suppl 1:S58–62. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bbcc45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fenner L, Ballif M, Graber C, et al. Tuberculosis in antiretroviral treatment programs in lower income countries: availability and use of diagnostics and screening. PLoS One 2013;8:e77697. 10.1371/journal.pone.0077697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leroy V, Malateste K, Rabie H, et al. Outcomes of antiretroviral therapy in children in Asia and Africa: a comparative analysis of the iedea pediatric multiregional collaboration. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;62:208–19. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827b70bf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Group IPW. A survey of paediatric HIV programmatic and clinical management practices in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa -- the International epidemiologic databases to evaluate AIDS (iedea). J Int AIDS Soc 2013;16:17998. doi:17998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. World Health Organization . Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection- recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization . Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection - recommendations for a public health approach. 2nd edn. Geneva, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization . Essential prevention and care interventions for adults and adolescents living with HIV in resource-limited settings. Geneva, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schafer JL. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. New York: Chapman and Hall, 1997. 10.1201/9781439821862 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. WHO . COVID-19 pandemic leads to major backsliding on childhood vaccinations, new WHO, UNICEF data shows. New York & Geneva, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jesson J, Ephoevi-Ga A, Desmonde S, et al. Growth in the first 5 years after antiretroviral therapy initiation among HIV-infected children in the iedea West African pediatric cohort. Trop Med Int Health 2019;24:775–85. 10.1111/tmi.13237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Desmonde S, Neilan AM, Musick B, et al. Time-varying age- and CD4-stratified rates of mortality and WHO stage 3 and stage 4 events in children, adolescents and youth 0 to 24 years living with perinatally acquired HIV, before and after antiretroviral therapy initiation in the paediatric iedea global cohort consortium. J Int AIDS Soc 2020;23:e25617. 10.1002/jia2.25617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fritz CQ, Blevins M, Lindegren ML, et al. Comprehensiveness of HIV care provided at global HIV treatment sites in the iedea Consortium: 2009 and 2014. J Int AIDS Soc 2017;20:20933. 10.7448/IAS.20.1.20933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jiamsakul A, Kariminia A, Althoff KN, et al. Hiv viral load suppression in adults and children receiving antiretroviral therapy-results from the iedea collaboration. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;76:319–29. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request, following a review process and approval by IeDEA. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. All data requests must be approved by IeDEA.