Abstract

Background and Hypothesis

Through decades the clinical recovery outcomes among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia have been highly inconsistent ranging from 13.5% to 57%. The primary objective of this updated examination was to report the pooled estimate and explore various moderators to improve the understanding of the course of schizophrenia.

Study Design

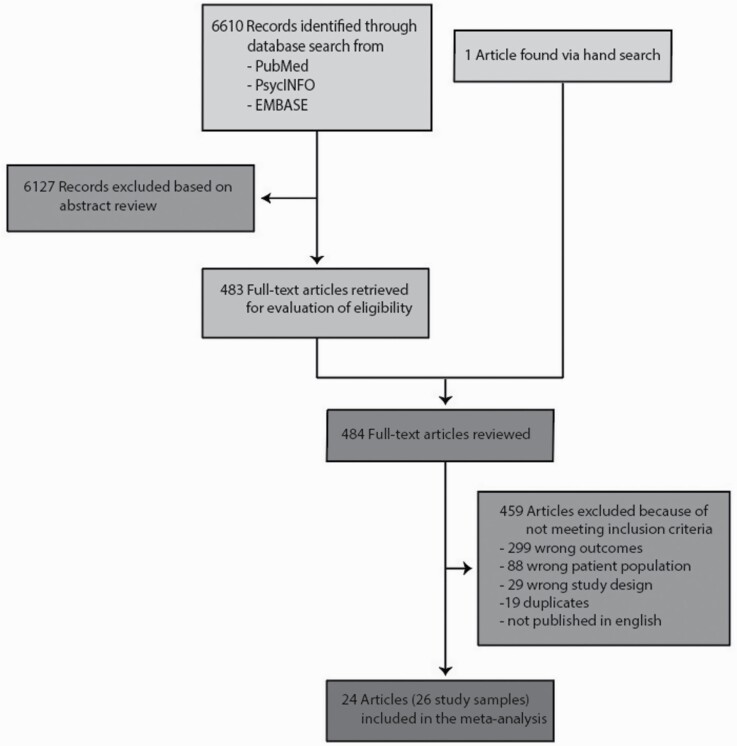

A systematic literature search was set up on PubMed, PsycInfo, and EMBASE until January 13th, 2022. Both observational and interventional studies among cohorts of individuals with the first episode of schizophrenia reporting on clinical recovery were included. The PRISMA 2020 statement was used and data was extracted for a random-effects meta-analysis, meta-regression, and sensitivity analyses. Risk of bias was assessed using The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale.

Study Results

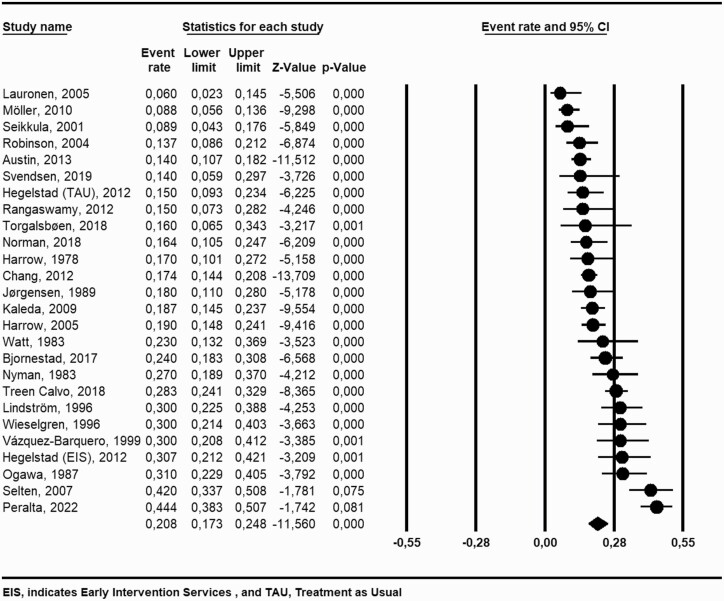

A 20.8% (95% CI = 17.3 to 24.8) recovery rate was found among 26 unique study samples (mean trial duration, 9.5 years) including 3877 individuals (mean age, 26.4 years). In meta-regression none of the following study characteristics could uncover the diverse reported recovery rates; age at inclusion (P = .84), year of inclusion (P = .93), follow-up time (P = .99), drop-out rate (P = .07), or strictness of the recovery criteria (P = .35). Furthermore, no differences in recovery were found between early intervention services (EIS; 19.5%; 95% CI = 15.0 to 24.8) compared to other interventions (21%; 95% CI = 16.9 to 25.8), P = .65.

Conclusions

A clinical recovery rate of approximately 21% was found with minimum impact from various moderators. The rate was not different comparing EIS with other interventions implying that new initiatives are needed to improve the rate of recovery.

Keywords: recovery, first-episode schizophrenia, first-episode psychosis, schizophrenia, early intervention services

Introduction

Kraepelin was the first to introduce the term “recovered” into the field of psychiatry, where he described the natural course of schizophrenia, with only 2.6% having permanent recovery and 13% experiencing recovery in a limited period.1 Since then the concept of clinical recovery has evolved and today, schizophrenia is no longer perceived as a deterministic illness. Still, the disorder is one of the leading causes of years lived with disabilities according to the World Health Organization (WHO) and therefore considered a major public health challenge.2 Furthermore, it has dominant influence on life expectancy with men and women losing more than 13 years and 11 years compared to the general population, respectively.3 Despite these problematic health issues, a substantial number of individuals with schizophrenia experience improvement of symptoms including clinical recovery.4 Multiple studies have for decades reported varying percentages of clinical recovery among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia ranging from 13.5% to 57%.5–8 Experts in the field suggest that the definition of clinical recovery should be based on the remission criteria put forward by the Remission of Schizophrenia Working Group9 (RSWG) as well as a functional and social dimension.10 Yet, there is still a lack of consensus on the criteria of clinical recovery.9,10. A recent, systematics review from 2021 found a 57% recovery rate among non-affective first-episode psychosis studies in nonclinical trials from the 21st century.6 The recovery criteria were based on the RSWG9 and/or Warner criteria11 and included a requirement of employment. A meta-analysis from 2017 among individuals with first-episode psychosis reported a 38% clinical recovery rate but when restricting the analysis to individuals with first-episode schizophrenia the recovery percentage fell to 30% based on 12 studies.7 Another meta-analysis from 2013 found a 13.5% clinical recovery rate in naturalistic studies among individuals with schizophrenia in various stages of illness.8 The authors found no significant difference in the percentage of clinical recovery in accordance with the first episode or multiple episodes of schizophrenia as well as gender, duration of follow-up or the strictness of the recovery criteria. As previously reported by the International Pilot Studies of Schizophrenia (IPSS)12,13 a significantly higher recovery percentage was found for low- and lower-middle-income countries compared to high and upper-middle-income countries.

Most of the prior reviews were based on non-interventional naturalistic cohort studies with recovery percentages ranging from 13.5% to 57%. In this updated systematic review and meta-analysis, we will reexamine the recovery percentage among individuals with a first-episode psychosis in the schizophrenia spectrum. First-Episode Schizophrenia should be viewed as a subgroup of the broader used term First-Episode Psychosis. We will uncover to which extent the observed inconsistencies in recovery percentages can be explained by clinical study characteristics. We will investigate the effects of different duration criteria of recovery, the strictness of the recovery criteria, and the inclusion of the remission criteria in the definition of recovery based on the RSWG.9 Additionally, we have allowed for all study interventions to be included to investigate the influence of early intervention services (EIS) on the recovery percentage.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement14 was used in the development of this review (see Supplementary Material for PRISMA 2020 Checklist). Furthermore, the protocol of this review was submitted a priori to PROSPERO (ID: CRD42021230667) and there were no deviations from the pre-published protocol.

Literature Search

We title-searched PubMed, PsychInfo, and EMBASE until January 13th, 2022 with the following search string developed by specialists in recovery to cover the definitions and words used to describe clinical recovery (see the Supplementary Material for search strategies and the search dates for all databases): (“schizo*” OR “psychoses” OR “psychosis” OR “psychotic” OR “first episode psychos*”) AND (“recovery” OR “remission” OR “prognos*” OR “course” OR “outcome*” OR “longitudinal” OR “follow-up” OR “long-term”)

The search was completed by scanning reference lists from the retrieved articles and handsearching recent reviews and meta-analyses of recovery and consulting experts in the field to find additional studies. Also, an alert was set up on all saved searches in the databases in order to get informed if any relevant new literature emerge. References were imported into the systematic review software tool Covidence and duplicates were removed.15

Inclusion Criteria

We included observational and interventional longitudinal studies reporting on clinical recovery among individuals diagnosed with a first episode of psychosis in the schizophrenia spectrum. The following inclusion criteria were used: studies published in English, studies with 15 or more individuals aged 16 years or older, studies with a follow-up time of at least 12 months. Furthermore, studies with multiple cohorts from different studies were included.

Data Abstraction

Two independent reviewers (H.G.H. and H.S.) screened all studies based on title and abstract and full text. Any discrepancies were resolved by seeking consensus or consulting a third reviewer (N.A.).

Outcome and Data Synthesis

As reported in the prespecified protocol submitted to PROSPERO the primary outcome was clinical recovery rates. In accordance with previous meta-analyses7,8 clinical recovery was defined as measures for both a clinical dimension (eg, symptom rating scales, absence of psychotic symptoms, no relapses or use of psychiatric hospitalization) and a social/functional dimension (eg, social/functional rating scales, social, occupational, or educational domains) with a duration of at least 12 months on either clinical or social/functional dimensions. In studies that did not specifically state the word recovery, we extracted data from study texts and tables to satisfy our recovery criteria. An example of a sufficient recovery definition would be a study stating a symptom dimension of symptom remission for 12 months and a social/functional dimension of living independently and social interaction with a score of 4 or more on the Strauss–Carpenter Level of Function Scale.12 Another example of a sufficient recovery definition would be a symptom dimension of absence of major symptoms throughout the follow-up year and a social/functional dimension with adequate psychosocial functioning, instrumental work (half-time or more) including absence of a very poor social activity level (see Supplementary Table 2 for the individual study definitions of clinical recovery). Furthermore, we extracted data on study characteristics including age at inclusion (mean), setting (inpatients vs both in- and outpatients), year of inclusion (year at the midpoint of the data collection period), country of origin (high income-countries vs upper middle to low income-countries16), intervention (EIS vs other interventions), duration of follow-up, drop-out rates, and use of RSWG criteria in the recovery definition as well as strictness (using a strictness score designed by Jääskeläinen et al.8) and the duration of the recovery definition (1 vs 2 vs 3 years or more). In studies with multiple follow-up points the study with the longest follow-up time was included.

Additionally, data were also extracted on the first author, year of publication, study design, sample size, sex distribution, use of antipsychotics, diagnostic classification (ie, schizophrenia, schizophreniform, schizoaffective, and delusional disorder, etc.) and diagnostic tool(s) used for diagnosis (Table 1). Furthermore, see Supplementary Table 1 for further details on the individual study characteristics.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Author, Year of Publication | Country | Illness Stage at Entry | Mean Age (Years) | Sample Size Baseline | Sample Size Follow-up | Intervention | Years of Follow-up | Clinical Recovery % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austin , 2013 |

Denmark (Europe) | FEP/FES | 26.6 | 496 | 304 | EIS | 10 | 14 |

| Bjornestad, 2017 | Norway (Europe) | FEP/FES | 26.85 | 363 | 178 | EIS | 2 | 24 |

| Chang (EASY Program), 2012 | Hongkong (Asia) | FEP/FES | 21 | 700 | 539 | EIS | 3 | 17.4 |

| Harrow, 1978 | USA (North America) | FES | 23.5 (median) | 79 | 75 | Case-control study | 2.7 | 17 |

| Harrow, 2005 | USA (North America) | FES | 22.8 | 274 | 274 | Case-control study | 15 | 19 |

| Hegelstad, 2012 | Norway/Denmark (Europe) | FES | 26/31 | 140/141 | 73/101 | Quasi-experimental design Case-control study | 10 | 30.7 (EIS) 15 (TAU) |

| Jørgensen, 1989 | Denmark (Europe) | First admitted delusional psychosis (FES/FEP) | 36 | 88 | 79 | General psychiatric hospital treatment | 4 | 18 |

| Kaleda, 2009 | Russia (Asia/Europe) | FES | 20.4 | 278 | 278 | General psychiatric hospital treatment | 15 | 18.7 |

| Lauronen, 2005 | Finland (Europe) | FES | 23.5 | 71 | 71 | Epidemiologic Birth cohort | NA | 6 |

| Lindström, 1996 | Sweden (Europe) | FEP never treated with antipsychotics | 27.1 | 120 | 120 | Treated with neuroleptics, social skill straining and family support | 5 | 30 |

| Möller, 2010 | Germany (Europe) | First admitted patients (FES) | 35 | 323 | 197 | General psychiatric hospital treatment | 15 | 8.8 |

| Norman, 2018 | Canada (North America) | FEP/FES | 25.2 | 166 | 106 | EIS | 5 | 16.4 |

| Nyman, 1983 | Sweden (Europe) | FES | 25.9 | 110 | 91 | General psychiatric hospital treatment | 6–9 | 27 |

| Ogawa, 1987 | Japan (Asia) | FES | 81% were under 30 years, 79% were first admissions | 140 | 105 | Neuroleptics, open-door system, intensive care | 23.6 | 31 |

| Peralta, 2022 | Europe (Spain) | FES | 27.5 | 623 | 243 | General psychiatric hospital treatment | 21 | 44.4 |

| Rangaswamy, 2012 | India (Asia) | FES | 24.5 | 90 | 47 | NA | 25 | 15 |

| Robinson, 2004 | USA (North America) | FES | 25.2 | 118 | 118 | Standardized medication algorithm | 5 | 13.7 |

| Seikkula, 2001 | Finland (Europe) | FES | 26.5 | 90 | 78 | The Open Dialogue Approach | 2 | 8.9 |

| Selten, 2007 | Netherlands (Europe) | First admitted patients (FES) | 24.5 (median) | 125 | 125 | NA | 2.5 | 42 |

| Svendsen, 2019 | Norway (Europe) | FES | 25.2 | 56 | 35 | Local mental health services | 7 | 14 |

| Torgalsbøen, 2018 | Norway (Europe) | FEP/FES | 21 | 31 | 28 | Local mental health services | 4 | 16 |

| Treen Calvo, 2018 | Spain (Europe) | FES | 30 | 577 | 399 | NA | 3 | 28.3 |

| Vázquez-Barquero, 1999 | Spain (Europe) | FES | NA | 86 | 76 | NA | 3 | 30 |

| Watt, 1983 | United Kingdom (Europe) | FEP | 17–60 | 48 | 48 | Terapeutic trial with neuroleptics | 5 | 23 |

| Wieselgren, 1996 | Sweden (Europe) | First-admitted and had never been treated with neuroleptics (FES) | 27.1 | 120 | 89 | Special ward for young psychotic patients | 5 | 30 |

Note: FEP, First Episode of Psychosis; FES, First Episode of Schizophrenia; EIS, early intervention services; TAU, treatment as usual; NA, not applicable/available.

To evaluate the strictness of the clinical recovery we used a strictness score designed by Jääskeläinen et al.8. First, the clinical definitions of recovery were scored. Second, the degree of symptom severity and functional/social dimensions of clinical recovery were scored. Third, the mean of these estimates was calculated resulting in a strictness score between 0 and 100: where 100 indicates the most stringent definition and 0 the vaguest definition

Risk of bias was assessed by H.G.H. and M.S. using The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) developed for cohort and case-control studies by the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute.17 The NOS scale covers the following 3 categories with subitems: The Selection category including (1) representativeness of the exposed cohort, (2) selection of the nonexposed cohort, (3) ascertainment of exposure, (4) demonstration that outcome of interest was not present at start of study and the Comparability category including comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis. The Outcome category including (1) assessment of Outcome, (2) was follow-up long enough for outcomes to occur, and (3) adequacy of follow-up of cohorts. A study can be awarded a maximum of one star for each numbered item within the Selection and Outcome categories and a maximum of 2 stars can be given for Comparability but Since comparability between groups was not the object of this review, every study was allocated two stars in this item. Higher scores indicated better quality and lower risk of bias. To distinguish between good and poor-quality studies every study was given a quality score and divided into high quality (total score of ≥7) and low quality (≤6) (see Supplementary Table 1 for the individuals study quality scores).

During data extraction, all studies clearly stating less than 12 months duration on either clinical or social/functional dimensions in the recovery criteria were excluded from the primary analysis. Still, for 11 studies there was uncertainty of the duration of the recovery criteria, therefore these studies were excluded from the primary analysis but included in sensitivity analyses. All WHO-led studies did obtain the recovery criteria but did not satisfy the inclusion criteria (ie, individuals diagnosed with a first episode of psychosis in the schizophrenia spectrum). Instead, they reported on mixed samples (both first episodes and multiple episodes of psychosis) and therefore these studies were excluded from the primary analysis and included in sensitivity analyses (see Supplementary Tables 4 and 5) for more characteristics among WHO-led studies and studies with uncertainty of the duration of the recovery criteria, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

With the use of Comprehensive Meta-analysis version 3 statistical software we conducted a random effects meta-analysis (performed by H.G.H. and H.S.). Pooled overall estimates of proportions of clinical recovery rates were performed with 95% CIs. Continuous variables were expressed with coefficients and categorical variables were expressed with pooled event rates and associated 95% CIs. Study heterogeneity was explored using I2 statistics, with I2 > 50% indicating significant heterogeneity.

Moderators were explored in meta-regressions for continuous variables (ie, age of inclusion, year of inclusion, study follow-up time, drop-out rate, proportion of use of antipsychotics over the follow-up period, and strictness of the recovery criteria) and reported on logit event rate. Subgroup analyses were used for categorical variables (ie, inpatients vs both in- and outpatients, high income-countries vs upper middle to low income-countries, early intervention studies vs other studies, risk of bias assessment with NOS scores ≤6 vs ≥7 and use of RSWG criteria9 in the recovery definition vs no use of the RSWG criteria). In sensitivity analysis we first included 7 WHO-led studies with both multiple- and first-episode psychosis into the primary analysis and second, we added further 11 studies with uncertainty of the duration of the recovery criteria to the primary analysis. Finally, when inspecting funnel plots Egger’s regression was used to detect publication bias.

Results

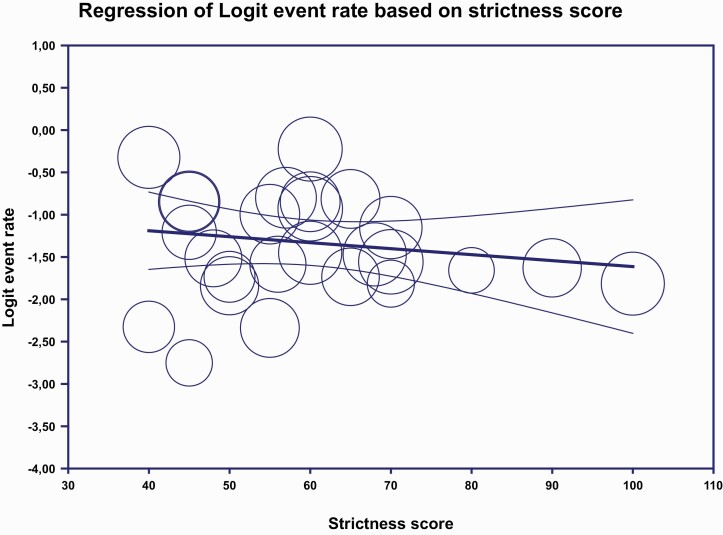

After duplicate removal, a total of 6610 studies were identified of which 483 articles were full text screened and 25 of these met the study inclusion criteria18–42 (figure 1). All together these articles included 26 unique study samples with 3877 individuals from 15 different countries (Table 1). We found a 20.8% pooled recovery rate (95% CI = 17.3 to 24.8, I2 = 88.9%) among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (figure 2). Participants included had a mean age of 26.4 years (range 21.0–36.0 years) and a mean follow-up time of 9.5 years (range 2–27 years). When exploring the different definitions of recovery there was no significant difference on the recovery percentage among studies with a recovery definition based on the remission criteria by RSWG vs no use of RSWG criteria (23.0%; 95% CI = 16.1 to 31.7, 8 studies vs 19.9%; 95% CI = 16.1 to 24.3, 18 studies), P = .48. When exploring the duration criteria of the recovery definition we found no significant differences among studies with a duration criterion of 3 years or more (24.1%; 95% CI = 18.4 to 31.1, 5 studies) vs 2 years (16.0%; 95% CI = 11.3 to 22.3, 11 studies) vs 1-year duration (24.8%; 95% CI = 18.9 to 31.7, 10 studies), P =.09. In meta-regression we found a nonsignificant tendency (2-sided P-value = .35) that stricter recovery definitions lead to a lower recovery percentage (based on the Strictness score of Jääskeläinen et al.) (figure 3) with 13% of the variation being explained by the strictness of the recovery definition. See Supplementary Table 2 for the individual study definitions of clinical recovery.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Fig. 2.

Forrest plot—pooled recovery rate.

Fig. 3.

Meta-regression strictness score.

Looking at the risk of bias assessment, we found no significant differences on recovery percentage among studies with a lower quality score (NOS of ≤6) (21.4%; 95% CI = 17.4 to 26.0, 15 studies) compared to a higher quality score (NOS of ≥7) (20.2%; 95% CI =14.6 to 27.4, 11 studies), P =.78. When investigating the setting for inclusion of the study participants no differences in recovery were found between inpatients (21.3%; 95% CI =16.2 to 27.6, 13 studies) and mixed patients (22.1%; 95% CI = 16.1 to 29.5, 9 studies), P = .86.

To explore sociocultural differences, we divided the origin of the study samples into high income- countries vs upper middle- to low income-countries and found no significant differences in recovery percentage (21.1; 95% CI = 17.3 to 25.4, 24 studies vs 18.2%; 95% CI = 14.4 to 22.8, 2 studies, P = .33). When adding further 16 studies into the analysis (including WHO-led studies with mixed samples of multiple and first episode of psychosis and studies with uncertainty of the duration of the recovery criteria) we still found no significant difference between high income-countries (22.3%; 95% CI =19.4 to 25.5, 36 studies) and upper middle- to low income-countries (25.1%; 95% CI = 14.8 to 39.4, 6 studies), P =.65. Exploring the study intervention, we found no significant differences in the recovery percentage among studies with EIS (19.5%; 95% CI = 15.0 to 24.8, 5 studies) compared to other interventions (21.0%; 95% CI = 16.9 to 25.8, 21 studies), P =.66. The comparison studies of other interventions included three case-control studies, one epidemiological study, one therapeutic trial with either oral or injected depot neuroleptics and the remaining 16 studies was observational with various definitions of both local and general psychiatric in- and outpatient treatments (Table 1).

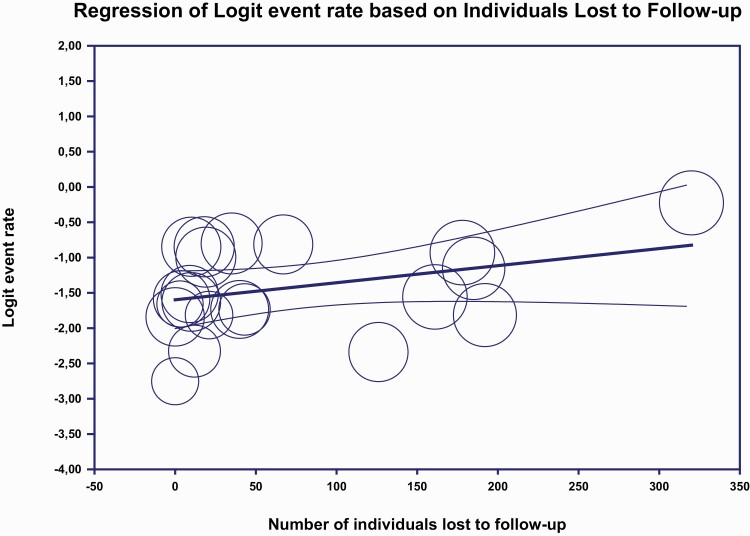

In meta-regression, there was no effect on the study follow-up time on the recovery percentage (see Supplementary figure 2). A tendency of a higher recovery was found for studies with greater drop-out rate (figure 4), but this was not significant. When investigating year and age of inclusion in meta-regression still no significant differences were detected (see Supplementary Table 3 for Results of univariate meta-regression analyses).

Fig. 4.

Meta-regression lost to follow-up .

Investigation of publication bias indicated a possible lack of small studies reporting on high recovery rates (see Supplementary figure 4).

Six studies23,34,36,38,41,42 (7 unique study samples) reported on proportion of use of antipsychotics. The 15-year follow-up of the Chicago follow-up study reported the lowest use of anti-psychotics with 62% of participants in treatment with antipsychotics.36 The study of schizophrenia in Japan reported the highest use with 91% of participants being prescribed neuroleptics without further specification.23 The rest of the studies reported the use of antipsychotics ranging from 63% till 74%34,38,41,42

In post-hoc meta-regression, no significant differences in recovery rate were found between the studies regarding the proportion of use of antipsychotics among study participants over the follow-up period, (2-sided P-value = .08) (see Supplementary Table 3 for Results of univariate meta-regression analyses).

Sensitivity Analyses

When including 7 WHO initiated studies,43–49 with both multiple- and first-episode psychosis, into the analysis the recovery percentage was estimated to be 21.6% (95% CI =18.4 to 25.2, 33 studies) and there was no significant difference between the recovery rate among WHO-led studies (24.4%; 95% CI = 17.5 to 33.0, 7 studies) and the studies in the primary analysis (20.8%; 95% CI =17.3 to 24.8, 26 studies), P = .4 (see Supplementary figure 5)

In another sensitivity analysis, we further added 11 studies50–60 with uncertainty of the duration of the recovery criteria and the overall recovery percentage was estimated to 22.3% (95% CI = 19.2 to 25.7, 37 studies), with no significant difference in recovery rate between the studies in the primary analysis and studies with uncertainty of the duration of the recovery criteria (25.6%; 95% CI = 19.9 to 32.4, 11 studies), P = .18 (see Supplementary figure 6).

Discussion

We found a 20.8% recovery rate among individuals with a first episode of psychosis in the schizophrenia spectrum during a mean follow-up of 9.5 years. Most important, a wide confidence interval, despite high number of studies, and a strikingly high heterogeneity, suggest that average rates of recovery should be interpreted cautiously. We explored the explanatory effect of several a-priori-defined moderators, without identifying any single factor that explained a statistical or clinically significant amount of the variation. When exploring the various definitions of recovery, no significant differences in recovery rates were found dependent on the strictness of the recovery definition applied in studies, the duration criterion of the recovery definition, or the use of the RSWG9 criteria in the clinical recovery definition. A nonsignificant tendency of higher recovery rates was found for studies with higher attrition bias, implying that individuals with less fortunate outcomes might drop out, thereby improving the recovery rate in the studies.

Previous meta-analyses on recovery have methodological concerns on how to compare results from different studies with varying inclusion criteria such as heterogenous samples with different illness stages at study entry as well as different follow-up periods. When we included further studies to the primary analysis, such as WHO-led studies with unverified illness stages the recovery percentage remained largely the same. Also, no effect was found on recovery rates according to duration of study follow-up time. Furthermore, age and year of study inclusion might be of critical importance when comparing outcomes between studies. Yet again, no significant modification of the recovery percentage was detected for these categorical values. In addition, the setting for inclusion of the study participants (inpatients vs both in- and outpatients) had no influence on the recovery percentage. This meta-analysis is therefore consistent with others that find either no predictors or only weak predictors of outcome. Based on these results it is therefore important that we do not prejudge who is likely to recover clinically and who is not.

Studies have suggested that continuous use of antipsychotic medication may impact negatively on the recovery rate. Only 6 studies23,34,36,38,41,42 (7 unique study samples) reported on use of anti-psychotics ranging from 62% to 91% of study participants in treatment with anti-psychotics. In post-hoc meta-regression no differences in recovery rate was found between the studies on the basis of use of antipsychotic medication. Since only 6 studies reported on this outcome this result is highly inconclusive and should be interpreted with caution.

It could be hypothesized that increased use of EIS may increase recovery rates. Findings favoring EIS in the short term have been confirmed in a recent meta-analysis including 10 randomized controlled trials among individuals with schizophrenia.61 With a mean trial duration of 16.2 months the authors found better effects on all outcomes including recovery (3 studies, n = 640) compared to treatment as usual.61 Surprisingly, this finding was not confirmed in this meta-analysis. When comparing 5 studies with EIS (n = 1293, mean follow-up time 6 years) to other interventions no difference was detected in the recovery rate. This could be due to small sample size or heterogeneity of interventions in the comparison studies. The finding might also imply that effects on clinical outcomes disappear among early intervention samples in the long-term.62

Back in the 1960s, the WHO-led IPSS studies found significantly better social and symptomatic outcomes among individuals from developing countries compared to developed countries.13 These results were later confirmed in the Determinants of Outcome of Severe Mental Disorders studies including research centers in 10 different countries.63 The reasons for the differences in course and outcomes are still not fully understood but findings point to social factors such as family relations and support to explain the better outcomes rather than biological factors. Likewise, some meta-analyses have found differences in recovery between Continents7 as well as high- and low-income countries8 whereas others find no difference between regions.6 In this meta-analysis, no low-income countries were represented. Instead when exploring the nature of schizophrenia between high-income countries vs upper middle- to middle income-countries, we did not find any significant difference in recovery percentage. Albeit, this result should be interpreted with caution since only 2 studies in the primary analysis were not from high-income countries. When adding further strength into the analysis by including WHO-led studies with mixed samples of multiple and first episode of psychosis and studies with uncertainty of the duration of the recovery criteria we found no significant difference between high-income countries (36 studies) and upper middle- to middle income countries (including 6 studies from India, Nigeria, Colombia, South Africa, and Russia).

In accordance with previous meta-analyses in the field, we implemented relatively strict criteria for clinical recovery demanding a symptom dimension and a social/functional dimension with at least 12 months duration on either one. Still, the field of psychiatry would benefit from a consensus definition of clinical recovery. A clear definition would allow for transparency and for comparison between interventions and outcomes in studies among individuals diagnosed with psychosis. Also, it would promote and maintain long-term positive outcomes in schizophrenia and make recovery a treatment goal instead of an unachievable ambition.

Limitations

The inference made to real-world populations, regarding average recovery rates and lack of explanatory effect of explored variables, should be subjected to caution. The interpretation of recovery rates is limited by the high degree of heterogeneity, which challenges if mean values are meaningful at all, despite our attempts to homogenize the clinical population and the definition of recovery. There are inherent limitations in the methodology of exploring explanatory variables. Due to the expected high heterogeneity between studies, meta-analyses are not the ideal way to explore predictors of clinical recovery, still we find the lowest heterogeneity between studies compared to previous meta-analyses in the field.

Interpreting effects of early intervention studies leads to risk of confounding and should be interpreted as ecological associations rather than causal effects, since the comparison studies refer to various other study designs (ie, case-control studies, epidemiological studies, therapeutic trials, and observational studies with various definitions of both local and general psychiatric in- and outpatient treatments). Furthermore, small number of studies included in subgroup analyses and meta-regression confuses the differentiation between inconclusive and truly neutral findings and introduces a somehow contra-intuitive risk of spurious positive findings.

Also, to avoid methodological concerns on how to compare results from different studies with different illness stages at study entry we were strict on only including individuals with a first episode of schizophrenia into the analyses, excluding those diagnosed with affective psychosis. Furthermore, we only included studies with individuals in the early stages of the illness, since samples with mixed illness stages would also bias the results, hence retrospective diagnosis risks conflating outcomes with diagnosis (ie, diagnosing people with worse outcomes as having schizophrenia).

The funnel plot indicated possible publication bias, with a relative scarcity of small studies reporting high recovery rates. This finding is noteworthy since most small studies with relatively large effects tend to get published. If this potential lack of small studies with large effects is true, then our findings may be considered conservative with underestimation of the true recovery rate.

Too little information was available at baseline in the studies on alcohol and substance abuse, use of antipsychotics, and positive and negative symptoms which might moderate long-term outcomes. Furthermore, small amount of subgroup analysis reporting on recovery percentages among men and women were not sufficient for analysis.

In the literature search for this systematic review and meta-analysis, we did not use controlled vocabulary terms, instead, we did a title-search which is in line with previous systematic reviews in the field.7,8

Strengths

This knowledge synthesis is done according to a prepublished protocol with rigid description of definitions and analysis plan, restricting the risks of spurious findings and adhering to the PRISMA 2020 statement. We had strict definitions of inclusion criteria and definitions of outcomes, to ensure that we only included individual diagnosed with psychosis in the schizophrenia spectrum, excluding individuals with first-episode affective psychosis, and that the definition of recovery included a symptom dimension and social/functional component and a criterion of duration to enhance clinical importance. Five years have gone since the latest update on long-term recovery among first-episode schizophrenia. Compared to the latest meta-analyses in 2017, we found a markedly lower recovery rate of 21% compared to the 30% recovery rate among first-episode schizophrenia reported by Lally et al. The reason for this deviating finding could be the lack of risk of bias assessment in the 2017 meta-analysis which might lead to non-representable sampling. We were also able to increase the number of included studies (more than doubled the number of studies in the analysis) among first-episode schizophrenia, increasing the power and the possibilities to explore heterogeneity. Since, previous meta-analyses excluded interventions studies6,8 and randomized controlled trials,7 we are the first to report on EIS compared to other interventions. Furthermore, we were able to increase the follow-up time of the included studies from 7.2 years to 9.5 years.

Conclusion

Overall, a clinical recovery of approximately 21% was found among individuals with a first-episode schizophrenia with minimum impact on the recovery rate from various moderators. This finding is in line with earlier systematics reviews and indicates that Kraepelin’s view on schizophrenia as chronic and deteriorating development is too pessimistic. As implication for future research, we suggest that alternative moderators and mediators are searched for, in order to understand the recovery process and develop more effective interventions. Some proposed factors could be substance abuse, level of psychotic and negative symptoms, duration of untreated psychosis and adherence to treatment, all factors we were unable to explore due to lack of information. Exploring these in future systematic reviews including individual-level data, may improve the knowledge gap. Finally, the recovery rate was not different comparing EIS with other interventions implying that new initiatives are needed to improve the rate of recovery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Troels Boldt Rømer for inspiration to the data extraction process. The team of Inclusion and Recovery for expertise in the search-string and -strategy process. The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

Contributor Information

Helene Gjervig Hansen, Copenhagen Research Centre for Mental Health – CORE, Mental Health Centre Copenhagen, Faculty of Health Science, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Helene Speyer, Copenhagen Research Centre for Mental Health – CORE, Mental Health Centre Copenhagen, Faculty of Health Science, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Marie Starzer, Copenhagen Research Centre for Mental Health – CORE, Mental Health Centre Copenhagen, Faculty of Health Science, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Nikolai Albert, Copenhagen Research Centre for Mental Health – CORE, Mental Health Centre Copenhagen, Faculty of Health Science, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; Center of Psychiatry Amager, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Carsten Hjorthøj, Copenhagen Research Centre for Mental Health – CORE, Mental Health Centre Copenhagen, Faculty of Health Science, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark; Section of Epidemiology, Department of Public Health, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Lene Falgaard Eplov, Copenhagen Research Centre for Mental Health – CORE, Mental Health Centre Copenhagen, Faculty of Health Science, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Merete Nordentoft, Copenhagen Research Centre for Mental Health – CORE, Mental Health Centre Copenhagen, Faculty of Health Science, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Funding

The project was funded by unrestricted grants from the Tryg Foundation (ID: 121654) and Health Foundation (ID: 19-B-0130). The sponsors had no role in the acquisition of the data, interpretation of the results, or the decision to publish the findings.

References

- 1. Kraepelin E, Amberg E.. Psychiatrie: Ein Lehrbuch fur Studierende und Aertze. Leipzig: Verlag von Johann Ambrosius Barth; 1909. [Google Scholar]

- 2. James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1789–1858. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laursen TM, Plana-Ripoll O, Andersen PK, et al. Cause-specific life years lost among persons diagnosed with schizophrenia: is it getting better or worse? Schizophr Res. 2019;206:284–290. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. James DH, Ross JB, Mauricio T, Christine Waternaux GO.. One hundred years of schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of the outcome literature. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(10):1409–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Menezes NM, Arenovich T, Zipursky RB.. A systematic review of longitudinal outcome studies of first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med. 2006;36(10):1349–1362. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Huxley P, Krayer A, Poole R, Prendergast L, Aryal S, Warner R.. Schizophrenia outcomes in the 21st century: a systematic review. Brain Behav. 2021;11(6):1–12. doi: 10.1002/brb3.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lally J, Ajnakina O, Stubbs B, et al. Remission and recovery from first-episode psychosis in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of long-term outcome studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;211(6):350–358. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.117.201475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jääskeläinen E, Juola P, Hirvonen N, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(6):1296–1306. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Andreasen NC, Carpenter WT, Kane JM, Lasser RA, Marder SR, Weinberger DR.. Remission in schizophrenia: proposed criteria and rationale for consensus. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, Gutkind D.. Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2002;14(4):256–272. doi: 10.1080/0954026021000016905. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Warner R. Recovery from schizophrenia and the recovery model. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22(4):374–380. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0B013E32832C920B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jablensky A, Sartorius N, Ernberg G, et al. Schizophrenia: manifestations, incidence and course in different cultures. A World Health Organization ten-country study. Psychol Med Monogr Suppl. 1992;20:1–97. doi: 10.1017/S0264180100000904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sartorius N, Gulbinat W, Harrison G, Laska E, Siegel C.. Long-term follow-up of schizophrenia in 16 countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1996;31(5):249–258. doi: 10.1007/BF00787917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/BMJ.N71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Covidence. Better Systematic Review Management. https://www.covidence.org/. Accessed January 4, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Bank Open Data | Data. https://data.worldbank.org/. Accessed March 4, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed January 4, 2022.

- 18. Austin SF, Mors O, Secher RG, et al. Predictors of recovery in first episode psychosis: the OPUS cohort at 10year follow-up. Schizophr Res. 2013;150(1):163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bjornestad J, Hegelstad WV, Joa I, et al. “With a little help from my friends” social predictors of clinical recovery in first-episode psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2017;255:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Möller HJ, Jäger M, Riedel M, Obermeier M, Strauss A, Bottlender R.. The Munich 15-year follow-up study (MUFUSSAD) on first-hospitalized patients with schizophrenic or affective disorders: comparison of psychopathological and psychosocial course and outcome and prediction of chronicity. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;260(5):367–384. doi: 10.1007/s00406-010-0117-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Norman RMG, MacDougall A, Manchanda R, Harricharan R.. An examination of components of recovery after five years of treatment in an early intervention program for psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2018;195:469–474. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nyman AK, Jonsson H.. Differential evaluation of outcome in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;68(6):458–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ogawa K, Miya M, Watarai A, Nakazawa M, Yuasa S.. A long-term follow-up study of schizophrenia in Japan. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;151:758–765. https://regroup-production.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/ReviewReference/282945444/Brit_J_Psych_1987_Ogawa.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAJBZQODCMKJA4H7DA&Expires=1625488900&Signature=FF1o2usT3C2dJM3v4I%2FXH8kiYYY%3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peralta V, García de Jalón E, Moreno-Izco L, et al. Long-term outcomes of first-admission psychosis: a naturalistic 21-year follow-up study of symptomatic, functional and personal recovery and their baseline predictors. Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(3):631–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rangaswamy T. Twenty-five years of schizophrenia: the Madras longitudinal study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2012;54(2):134– 10.4103/0019-5545.99531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Robinson DG, Woerner MG, McMeniman M, Mendelowitz A, Bilder RM.. Symptomatic and functional recovery from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):473–479. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seikkula J, Alakare B, Aaltonen J.. Open dialogue in psychosis II: a comparison of good and poor outcome cases. J Constr Psychol 2001;14(4):267–284. doi: 10.1080/107205301750433405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Svendsen IH, Øie MG, Møller P, Nelson B, Haug E, Melle I.. Basic self-disturbances independently predict recovery in psychotic disorders: a seven year follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2019;212:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Torgalsbøen AK, Fu S, Czajkowski N.. Resilience trajectories to full recovery in first-episode schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2018;52:54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chang WC, Tang JY, Hui CL, et al. Prediction of remission and recovery in young people presenting with first-episode psychosis in Hong Kong: a 3-year follow-up study. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46(2):100–108. doi: 10.1177/0004867411428015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Treen Calvo D, Giménez-Donoso S, Setién-Suero E, Toll Privat A, Crespo-Facorro B, Ayesa Arriola R.. Targeting recovery in first episode psychosis: the importance of neurocognition and premorbid adjustment in a 3-year longitudinal study. Schizophr Res. 2018;195:320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vázquez-Barquero JL, Cuesta MJ, Herrera Castanedo S, Lastra I, Herrán A, Dunn G.. Cantabria first-episode schizophrenia study: three-year follow-up. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:141–149. https://regroup-production.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/ReviewReference/282529691/BJP_1999_Vazquez-Barquero.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAJBZQODCMKJA4H7DA&Expires=1625488909&Signature=OKLssshzlnUYIxZ35QrPETJT%2Ff0%3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Watt DC, Shepherd M, Katz K.. The natural history of schizophrenia: a 5-year prospective follow-up of a representative sample of schizophrenics by means of a standardized clinical and social assessment. Psychol Med. 1983;13(3):663–670. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700048091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wieselgren IM, Lindström LH.. A prospective 1-5 year outcome study in first-admitted and readmitted schizophrenic patients; relationship to heredity, premorbid adjustment, duration of disease and education level at index admission and neuroleptic treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93(1):9–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10613.x.- [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Selten JP, Veen ND, Hoek HW, et al. Early course of schizophrenia in a representative Dutch incidence cohort. Schizophr Res. 2007;97(1-3):79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Harrow M, Grossman LS, Jobe TH, Herbener ES.. Do patients with schizophrenia ever show periods of recovery? A 15-year multi-follow-up study. Schizophr Bull. 2005;31(3):723–734. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbi026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Harrow M, GrinkerRR, Sr, Silverstein ML, Holzman P.. Is modern-day schizophrenic outcome still negative? Am J Psychiatry. 1978;135(10):1156–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hegelstad WT, Larsen TK, Auestad B, et al. Long-term follow-up of the TIPS early detection in psychosis study: effects on 10-year outcome. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):374–380. doi: 10.1080/1533015X.2013.796190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jørgensen P. Prediction of clinical course and outcome in delusional psychoses: a multivariate analysis of a 4-year re-follow-up. Psychopathology. 1989;22(4):218–223. doi: 10.1159/000284601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kaleda VG. The course and outcomes of episodic endogenous psychoses with juvenile onset (a follow-up study). Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2009;39(9):873–884. doi: 10.1007/s11055-009-9208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lauronen E, Koskinen J, Veijola J, et al. Recovery from schizophrenic psychoses within the northern Finland 1966 birth cohort. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(3):375–383. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v66n0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lindström L. Clinical and biological markers for outcome in schizophrenia: a review of a longitudinal follow-up study in uppsala schizophrenia research project. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14(95):23S–26S. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(95)00201-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dube KC, Kumar N, Dube S.. Long term course and outcome of the Agra cases in the International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1984;70(2):170–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1984.tb01195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, et al. Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:506–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lambert M, Naber D, Schacht A, et al. Rates and predictors of remission and recovery during 3 years in 392 never-treated patients with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118(3):220–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. León CA. Clinical course and outcome of schizophrenia in Cali, Colombia: a 10-year follow-up study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989;177(10):593–606. https://regroup-production.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/ReviewReference/282945341/JNerv_Mental_disease_1989_Leon.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAJBZQODCMKJA4H7DA&Expires=1625488986&Signature=%2BgzQ4NQg%2BaAozN%2BZiN8waLrsjCU%3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mason P, Harrison G, Glazebrook C, Medley I, Dalkin T, Croupace T.. Characteristics of outcome in schizophrenia at 13 years. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;167(NOV.):596–603. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.5.596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Prudo R, Blum HM.. Five-year outcome and prognosis in schizophrenia: a report from the London Field Research Centre of the International Pilot Study of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150(MAR.):345–354. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.3.345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sartorius N, Jablensky A, Shapiro R.. Two-year follow-up of the patients included in the WHO International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 1977;7(3):529–541. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700004517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ayesa-Arriola R, Ortíz-García De La Foz V, Martínez-García O, et al. Dissecting the functional outcomes of first episode schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a 10-year follow-up study in the PAFIP cohort. Psychol Med. 2021;51(2):264–277. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719003179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bland RC, Parker JH, Orn H.. Prognosis in schizophrenia. Prognostic predictors and outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1978;35(1):72–77. https://regroup-production.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/ReviewReference/282528053/Arch_Gen_Psych_1978_Bland.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAJBZQODCMKJA4H7DA&Expires=1626775393&Signature=bJa84VKK0MvG0F%2BBWsVPm35TcO4%3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Todd NA. First episode schizophrenia: three year and sixteen year follow-up. Heal Bull. 1988;46(1):18–25. https://regroup-production.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/ReviewReference/282529428/Health_Bull_1988_Todd.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAJBZQODCMKJA4H7DA&Expires=1625488920&Signature=JUnllrl%2F9S2%2Bydc1Szf9%2BP6TD2o%3D. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bland RC, Orn H.. 14‐Year outcome in early schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1978;58(4):327–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1978.tb00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ciompi L. Three lectures on schizophrenia. The natural history of schizophrenia in the long term. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;136(5):413–420. doi: 10.1192/bjp.136.5.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Henry LP, Amminger P, Harris MG, et al. The EPPIC follow-up study of first-episode psychosis: longer-term clinical and functional outcome 7 years after index admission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(7):716–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Huber G, Gross G, Schuttler R, Linz M.. Longitudinal studies of schizophrenic patients. Schizophr Bull. 1980;6(4):592–605. doi: 10.1093/schbul/6.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jung SH, Kim WH, Choi HJ, et al. Factors affecting treatment discontinuation and treatment outcome in patients with Schizophrenia in Korea: 10-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Investig. 2011;8(1):22–29. doi: 10.4306/pi.2011.8.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Noreik K, Astrup C, Dalgard OS, Holmboe R.. A prolonged follow-up of acute schizophrenic and schizophreniform psychoses. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1967;43(4):432–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1967.tb05780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ohaeri J. Long-term outcome of treated schizophrenia in a Nigerian cohort. Retrospective analysis of 7-year follow-ups. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181(8):514–516. https://regroup-production.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/ReviewReference/282529176/JNervMentDis_1993_Ohaeri.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAJBZQODCMKJA4H7DA&Expires=1625488781&Signature=DOl4I4927zC5fpA1LjNL3OCI1vE%3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Phahladira L, Luckhoff HK, Asmal L, et al. Early recovery in the first 24 months of treatment in first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. npj Schizophr. 2020;6(1):2. doi: 10.1038/s41537-019-0091-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Correll CU, Galling B, Pawar A, et al. Comparison of early intervention services vs treatment as usual for early-phase psychosis: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(6):555–565. . doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Gry Secher R, Hjorthøj CR, Austin SF, et al. Ten-year follow-up of the OPUS specialized early intervention trial for patients with a first episode of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(3):617–626. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, et al. Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:506–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.