Abstract

Introduction

In 2019, there were over 1.1 million people living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and 2.4 million people living with hepatitis C virus (HCV) in the United States. One in seven (14%) are unaware of their HIV infection and almost half of all HCV infections are undiagnosed. People with unstable housing are disproportionately affected by HIV and HCV. The present study will evaluate interventions by community pharmacists that may reduce HIV and HCV transmission and promote linkage to care.

Methods

This study was conducted in an independent community pharmacy in Spokane, Washington. Eligible study participants were walk-in patients of the pharmacy, over the age of 18, and experiencing homelessness. Pharmacy patients were excluded if they had a history of HIV or HCV diagnosis, received a screening for HIV or HCV in the last six months or were unable to give informed consent. The intervention included administration of HIV and HCV point-of-care testing (POCT) using a blood sample, risk determination interview, comprehensive HIV and HCV education, and personalized post-test and risk mitigation counseling followed by referral to partnering health clinics.

Results

Fifty participants were included in the final data analysis. Twenty-two participants (44%) had a reactive HCV POCT, and one participant had a reactive HIV POCT. Of the 94% of participants who reported illicit drug use, 74% reported injection drug use. Seventy-six percent (n = 38) qualified for PrEP. Pharmacist referrals were made for 28 participants and 71% were confirmed to have established care.

Conclusion

Individuals experiencing homelessness are at an increased risk for acquiring HIV and HCV due to risky sexual behaviors and substance misuse. PrEP is underutilized in the U.S. and pharmacist involvement in the HIV and HCV care continuum may have a significant impact in improving linkage and retention in care of difficult to treat populations.

Keywords: Pharmacy practice, HIV, HCV, Point-of-care testing, Homelessness

Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IVUD, intravenous drug use; POCT, point-of-care testing; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; UNAIDS, United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

1. Background

In 2019, there were over 1.1 million people living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and 2.4 million people living with Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) in the United States (U.S.). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that one in seven (14%) people over the age of 13 are unaware of their HIV infection and nearly half of all HCV infections are undiagnosed.1,2 Transmission of HIV and HCV have considerable overlap with sexual exposure and injection drug use being the primary modes of transmission for both. Among HIV-infected adults in 2009, an estimated 21% were co-infected with HCV.3 People with unstable housing are disproportionately affected by HIV and HCV, with prevalence rates of HIV infection estimated to be as high as 21% and HCV infection as high as 36% which are attributed to higher rates of substance use disorder, severe mental health conditions, and limited access to preventative health measures.4, 5, 6, 7, 8.

In 2019, the CDC reported 34,800 new HIV diagnoses which represents an 8% decline from 2015.9 This accomplishment is in part due to the mobilized effort to increase testing for HIV, promotion of Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) for those with confirmed HIV diagnosis and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for those that are at risk. Despite these advancements in testing, research has shown that individuals at higher risk for acquiring and transmitting HIV and HCV, especially in persons who inject drugs, have discouraging testing rates for both: 8.6% for HIV and 7.7% for HCV.10 Since the majority of testing for communicable diseases occurs in doctor's offices and medical clinics, it is often the responsibility of the primary care provider to initiate the conversation for testing in a time-constrained health visit.11

In 2018, the U.S. saw an estimated 50,300 new HCV infections predominately among young adults aged 20–40 years old.2 HCV infection is primarily transmitted through blood-to-blood contact and is highly linked to IV drug use (IVDU). Since 2011, the U.S. has seen a steady increase in new HCV cases which coincides with the nation's opioid crisis.12 Substance misuse and mental health conditions can increase the risk of HIV and HCV both directly and indirectly. Sexually active adults and adolescents with pre-existing mental health conditions have shown to have higher risk sexual behaviors including multiple sexual partners, alcohol and drug use before sex, transactional sex, and inconsistent condom use which directly increase the risk for HIV and HCV.13, 14, 15. Mental health conditions and substance misuse can also indirectly lead to transmission of communicable diseases like HIV through non-adherence to ART resulting in unsuppressed viral loads and increased risk of transmission.16, 17, 18

Over the past decade, advancements in healthcare have transformed HIV into a manageable chronic disease state, with curative treatment available for HCV. The uptake of PrEP for the prevention of HIV infection is growing, yet it remains underutilized among at-risk populations, especially those with unstable housing.19,20 Data from the CDC National HIV Surveillance System Reports in 2019 showed that only 23% of those eligible for PrEP had it prescribed.21 Although there is no vaccine or pharmacological prevention for HCV infection, curative treatment with combination direct acting antivirals has become highly accessible and more tolerable than previous treatments with interferon therapy.22 Treatment with antivirals is also highly effective with an approximate 90% cure rate after an 8 to 12-week course of treatment.23,24 Despite the advancements in treatment and prevention, the systematic shortfalls in the U.S. healthcare system allow HIV and HCV infection to remain a significant threat to the unhoused population.25

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) initiative reports an ambitious target to achieve the goal of ‘95–95-95’ with the goal to end HIV/AIDS epidemic by 2030: 95% of all people living with HIV will know their HIV status; 95% of all people diagnosed with HIV will receive sustained antiretroviral therapy; and 95% of all people receiving antiretroviral therapy will have viral suppression.26 In the U.S. in 2016, 86% of persons with HIV were aware of their infection, 74% that were diagnosed were receiving care, and 83% of persons in care had achieved viral suppression.27 The U.S. National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan has a similar goal in preventing new viral hepatitis infections, ensuring individuals with viral hepatitis are aware of their infection and have access to high quality treatment.28 Pharmacists are some of the most accessible healthcare providers and are underutilized in the HIV and HCV care continuum.29 Considerable research has shown pharmacist involvement in the care of individuals with HIV and HCV leads to improvement in adherence, reduced pill burden, and higher rates of viral load suppression for HIV, and enhanced cure rates and medication optimization for HCV infection.30, 31, 32, 33, 34 Given the established success of pharmacy involvement in the management of HIV and HCV, there is precedent for community pharmacists to take on a greater role to expand access in the HIV and HCV care continuum by targeting suboptimal linkage and retention in care that is currently impeding the success of UNAIDS initiative and the National Viral Hepatitis Action Plan.

2. Objectives

The objective of this study is to evaluate the prevalence and risk factors for HIV and HCV infection in individuals with unstable housing and to assess the impact pharmacists can have on the HIV and HCV care continuum through screening, education, risk mitigation counseling and referral.

3. Methods

3.1. Project design

This study was conducted in a single independent community pharmacy in Spokane, Washington. Spokane has a population of approximately 230,000, predominately white (83.7%) with over 1700 individuals experiencing homelessness and 13% of the population living below the poverty line.35,36 The pharmacy chosen for this study is in a central location near downtown Spokane where most Drop-in Day Centers, Free Meal Sites, Emergency Shelters, and other general resources are located, which coincides with where most of the unhoused population of Spokane reside. This project received internal college funding for 50 HIV Point-of-Care Tests (POCT) (INSTI HIV-1/−2 Antibody test kit, bioLytical Laboratories), 50 HCV POCT (OraQuick HCV Rapid Antibody Test, OraSure Technologies, Inc.), supplies needed to conduct the tests, and a small gift-card incentive for participants. Participant recruitment from among pharmacy patients continued until 50 participants were identified and enrolled in the study. This study received full-board review by the Washington State University Institutional Review Board and was approved in December 2019 (IRB: 17925–002).

Eligible study participants were walk-in patients of the pharmacy who were over the age of 18 and currently experiencing homelessness (defined as having no nighttime residence, having spent the last 24 h outdoors, in an emergency shelter, or areas not meant for human habitation). Pharmacy patients were excluded from the study if they self-reported a history of HIV or HCV diagnosis, a screening for HIV or HCV within the last 6 months, or were unable to provide informed consent. Those that were eligible to participate in the study were asked if they were interested in receiving free HIV and HCV screening and education. Willing participants were informed that the screening and education would take approximately 30 to 45 min, their information would remain confidential, and were asked to sign a consent form. Interested pharmacy patients were screened by the pharmacist to meet inclusion criteria before being accepted as study participants. Participants who completed the study intervention received a $10 gift card.

3.2. Study intervention

Data collection took place from February 2020 to May 2021. A single HIV pharmacist specialist credentialed through the American Academy of HIV Medicine (AAHIVP) with training on post-test and risk mitigation counseling (SK), was involved in conducting the study intervention. The pharmacist intervention included three activities: administration of an HIV and HCV POCT using a blood sample from a finger prick; a one-on-one risk determination interview; and comprehensive disease state education with personalized risk mitigation and post-test counseling. The intervention began with administration of the POCT with HIV POCT results available within 5 min, and HCV POCT results available within 20 min. POCT results were discussed at the end of the session and while results were pending, the intervention continued with the risk determination interview and education component. Interview questions were developed by the researchers and independently reviewed by three HIV specialist clinical pharmacists, an HIV coordinator at the local health district, and an HIV-specialized physician at a local teaching health clinic. The interview questions were adjusted based on feedback from the subject matter experts before implementation. The risk determination interview included domains for mental health, substance misuse, and sexual behaviors to identify risk of HIV and HCV transmission and evaluate the need for HIV PrEP.

The principal design of the education provided for study participants was adapted from CDC recommendations and the National HIV and HCV curriculum developed by the University of Washington.22,37., 38., 39., 40. In brief, this education was provided as a lecture-based presentation that included disease state overview, risk factors, routes of transmission, available medications for treatment and prevention, clinical course of HIV/HCV infection, information on available community resources, and potential next steps in the setting of a reactive screening. The participants were also provided information on the ‘window period’ of the POCT which is defined as the time between acquisition of HIV or HCV and the time when the point-of-care test will accurately detect the infection. The CDC recommends using a 90-day window period for antibody POCT22,37,40 The educational component of the study intervention was interactive and lasted approximately 20 min.

Study participants were subsequently referred to partnering low-barrier healthcare clinics to establish care, obtain follow-up confirmatory testing, and/or receive evaluation for HIV PrEP based on screening results and identified risk(s) by the pharmacist investigator. To promote patient autonomy, study participants who had a reactive screening or were determined to qualify for PrEP were provided counseling and the option of referral via a ‘warm handoff’. The pharmacist and patient would make a joint call to one of the partnering community clinics to set up an appointment only if participants agreed to a referral.

This research protocol has been previously published in the first study of this research series which was adjusted based on the limitations and successes seen by investigators.41 The risk determination questionnaire was adjusted to include a specific timeframe (“within the last six months” vs. “ever”) in which study participants had engaged in risky sexual behaviors or illicit drug use to differentiate those with a current risk for communicable diseases versus those that may have been at risk during their lifetime. This adjustment enabled the investigators to more accurately determine whether the study participant was a current candidate for HIV PrEP.

From the initial study results, the investigators quickly learned that many study participants would be considered high-risk for HIV acquisition per CDC guidance, and thus a question was added to ascertain the participant's awareness of available HIV prophylaxis options. In the initial iteration of the project, study participants were only referred for HIV PrEP evaluation if it was determined they were high risk for HIV acquisition in the setting of a reactive HCV POCT. In the present version of the intervention, participants were referred for HIV PrEP evaluation if they were determined to be at high risk for HIV acquisition regardless of POCT results. Furthermore, in this version of the research protocol, patient autonomy was promoted by giving study participants the option of referral rather than a standardized process. To enhance participation, investigators removed the requirement to sign a release of medical information form. Although removing this requirement hinders the investigators' ability to evaluate the rate of retention in care and clinical characteristics of study participants, creating a low-barrier service promotes patient comfort and willingness to participate. Finally, this study evaluates the rate at which participants were linked to care, via follow-up communication with the referred providers, which provided the research team with an additional pathway to analyze the effectiveness of the study intervention.

4. Results

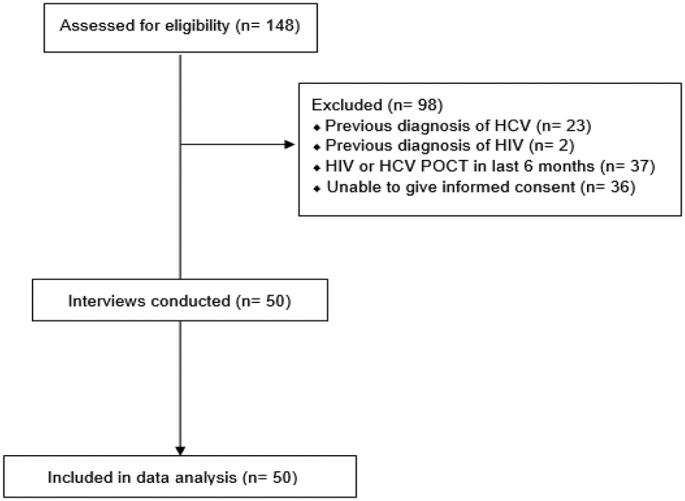

A total of 148 pharmacy patients experiencing homelessness were solicited to partake in the study and a total of 50 participants met the inclusion criteria and were included in the final data analysis, as shown in Fig. 1. Most study participants were white (n = 34, 68%), male (n = 40, 80%), and ages 31–40 years (n = 26, 52%). Patient demographics are displayed in detail in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram of participant recruitment.

Abbreviations used: HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; POCT: point-of-care testing.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and characteristics organized by point-of-care test results.

| Item | Reactive HCV POCT n = 22 n (%) |

Reactive HIV POCT n = 1 n (%) |

Non-Reactive POCTs n = 27 n (%) |

Total n = 50 n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 20 (90.9) | 1 (100) | 19 (70.4) | 40 (80) |

| Female | 2 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 8 (29.6) | 10 (20) |

| Age | ||||

| 20–30 years old | 3 (13.6) | 1 (100) | 6 (22.2) | 10 (20) |

| 31–40 years old | 13 (59.1) | 0 (0) | 13 (48.1) | 26 (52) |

| 41–50 years old | 3 (13.6) | 0 (0) | 5 (18.5) | 8 (16) |

| 51–60 years old | 3 (13.6) | 0 (0) | 3 (11.1) | 6 (12) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 15 (68.2) | 1 (100) | 18 (66.7) | 34 (68) |

| Black | 5 (22.7) | 0 (0) | 4 (14.8) | 9 (18) |

| Latino | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 4 (14.8) | 5 (10) |

| Middle Eastern | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.7) | 2 (4) |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Insured | 14 (63.6) | 1 (100) | 19 (70.4) | 34 (68) |

| Uninsured | 8 (36.4) | 0 (0) | 8 (29.6) | 16 (32) |

| Engagement with primary care provider | ||||

| Currently under care | 11 (50%) | 1 (100) | 16 (59.3) | 28 (56) |

| Not under care | 11 (50%) | 0 (0) | 11 (40.7) | 22 (44) |

| Alcohol use | ||||

| Reported use | 13 (59.1) | 1 (100) | 12 (44.4) | 26 (52) |

| Reported no use | 9 (40.9) | 0 (0) | 15 (55.6) | 24 (48) |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Current smoker | 19 (86.4) | 0 (0) | 21 (77.8) | 40 (80) |

| Non-smoker | 3 (13.6) | 1 (100%) | 6 (22.2) | 10 (20) |

| Illicit drug Use | ||||

| Reported use | 22 (100) | 1 (100) | 24 (89) | 47 (94) |

| Reported no use | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (11) | 3 (6) |

| Living situation | ||||

| Outdoors | 14 (63.6) | 0 (0) | 13 (48.1) | 27 (54) |

| Homeless shelter | 7 (31.8) | 0 (0) | 14 (51.9) | 21 (42) |

| Hotel | 1 (4.5) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) |

Abbreviations used: HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; POCT: point-of-care testing.

POCT results during the study showed that a total of 44% (n = 22) of participants had a reactive HCV screening, indicating potential infection during their lifetime, and 2% (n = 1) of participants had a reactive HIV screening, indicating a potential HIV diagnosis. Seventy-six percent (n = 38) of participants qualified for HIV PrEP but a referral was only made for 36% (n = 14) because some were already being referred for a reactive HCV screening (n = 9) and others opted out (n = 15). Of the 56% (n = 28) of participants that were referred to care, 71% (n = 20) were confirmed to have established care.

4.1. Mental health

Table 2 shows the responses of study participants when asked about current mental health diagnoses. Most study participants (n = 46, 92%) reported having a diagnosed mental health condition. The most prominent forms of mental health conditions were post-traumatic stress disorder (n = 36, 78%), depression (n = 31, 67%), and anxiety (n = 29, 63%). Of those who reported diagnosed mental health conditions, 72% (n = 33) reported receiving treatment for their diagnosis and 87% (n = 40) reported recreational drug use as a form of coping with their mental health condition.

Table 2.

Mental health characteristics of study participants organized by POCT result.

| Diagnosis | Reactive HCV POCT n = 22 n (%) |

Reactive HIV POCT n = 1 n (%) |

Non-Reactive POCTs n = 27 n (%) |

Total n = 50 n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 17 (77.3) | 1 (100) | 13 (48.1) | 31 (62) |

| Anxiety | 13 (59) | 1 (100) | 15 (55.6) | 29 (58) |

| Schizophrenia | 7 (31.8) | 0 (0) | 5 (18.5) | 12 (24) |

| Bipolar | 9 (40.9) | 1 (100) | 16 (59.3) | 26 (52) |

| PTSD | 17 (77.3) | 1 (100) | 18 (66.7) | 36 (72) |

| ADHD | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 5 (18.5) | 6 (12) |

| Insomnia | 4 (18.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.7) | 5 (10) |

| None | 17 (77.3) | 1 (100) | 21 (77.8) | 39 (78) |

| Response to the question “Are you currently receiving treatment for your mental health?” | ||||

| Yes | 14 (63.6) | 1 (100) | 18 (66.7) | 33 (66) |

| No | 8 (36.4) | 0 (0) | 9 (33.3) | 17 (34) |

| Response to the question “Are you using drugs recreationally to cope with one or more of your mental conditions?” | ||||

| Yes | 20 (90.9) | 1 (100) | 19 (70.4) | 40 (80) |

| No | 2 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 8 (29.6) | 10 (20) |

Abbreviations used: HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; POCT: point-of-care testing; PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder; ADHD: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

4.2. Substance misuse

When asked about drug use, 94% of study participants (n = 47) reported active drug use of any kind with methamphetamine being the most popular. Of those who reported any drug use, 74% (n = 35) reported IVDU. Methamphetamine IVDU was the most commonly reported agent (68%, n = 32), followed by heroin IVDU (55%, n = 26). Table 3 shows the recorded responses from study participants regarding substance misuse and recreational drug use.

Table 3.

Participant-reported substance misuse and recreational drug use organized by POCT result.

| Substance | Reactive HCV POCT n = 22 n (%) |

Reactive HIV POCT n = 1 n (%) |

Non-Reactive POCTs n = 27 n (%) |

Total n = 50 n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marijuana active use | ||||

| Yes | 19 (86.4) | 1 (100) | 17 (63) | 37 (74) |

| No | 3 (13.6) | 0 (0) | 10 (37) | 13 (26) |

| Methamphetamine active use | ||||

| IVDU | 11 (50) | 0 (0) | 7 (25.9) | 18 (36) |

| Smoke | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (11.1) | 4 (8) |

| IVDU/Smoke | 8 (36.4) | 0 (0) | 6 (22.2) | 14 (28) |

| No | 2 (9.1) | 1 (1) | 11 (40.7) | 14 (28) |

| Heroin active use | ||||

| IVDU | 12 (54.5) | 0 (0) | 5 (18.5) | 17 (34) |

| Smoke | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| IVDU/Smoke | 4 (18.2) | 0 (0) | 5 (18.5) | 17 (34) |

| No | 5 (22.7) | 1 (100) | 17 (63) | 23 (46) |

| Crack cocaine active use | ||||

| Smoke | 5 (22.7) | 0 (0) | 4 (14.8) | 9 (18) |

| No | 17 (77.3) | 1 (100) | 23 (85.2) | 41 (82) |

| Prescription medications actively used recreationally | ||||

| Opioid* | 8 (36.4) | 0 (0) | 6 (22.2) | 15 (30) |

| Benzodiazepines^ | 3 (13.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.7) | 4 (8) |

| Suboxone | 9 (40.9) | 0 (0) | 7 (25.9) | 15 (30) |

| No | 7 (31.8) | 1 (100) | 17 (63) | 25 (50) |

| Response to the question “Have you borrowed a needle for injection drug use in the last 6 months?” | ||||

| Yes | 19 (86.4) | 0 (0) | 12 (44.4) | 31 (62) |

| No | 3 (13.6) | 1 (100) | 15 (55.6) | 19 (38) |

| Response to the question “Have you ever shared a needle with someone who you knew was HIV or HCV positive?” | ||||

| HCV positive | 8 (36.4) | 0 (0) | 2 (7.4) | 10 (20) |

| HIV positive | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Never | 14 (63.6) | 1 (100) | 25 (92.6) | 40 (80) |

| Response to the question “Do you know where to access clean needles?” | ||||

| Yes | 15 (68.2) | 0 (0) | 16 (59.3) | 31 (62) |

| No | 7 (31.8) | 1 (100) | 11 (40.7) | 19 (38) |

Abbreviations used: HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; POCT: point-of-care testing; IVDU: intravenous drug user.

⁎Opioid Agonist: Examples of reported agents included hydrocodone, oxycodone, morphine.

^Benzodiazepines: Examples of reported agents included clonazepam, lorazepam, alprazolam.

4.3. Sexual behaviors

A total of 16 participants (32%) reported being in a current sexual relationship. Of those in a current sexual relationship, almost 70% (n = 11) were unaware of their partner's HIV or HCV status. Unprotected sexual intercourse was common among study participants with 60% (n = 30) reporting unprotected sex within the last six months. None of the participants reported having sexual intercourse with someone they knew to be diagnosed with HIV; however, six participants (12%) did admit to sexual intercourse with a partner they knew to be diagnosed with HCV. Table 4 shows study participant responses regarding sexual behaviors.

Table 4.

Sexual behaviors reported by study participants organized by POCT result.

| Reactive HCV POCT n = 22 n (%) |

Reactive HIV POCT n = 1 n (%) |

Non-Reactive POCTs n = 27 n (%) |

Total n = 50 n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response to the question “Are you currently in a sexual relationship?” | ||||

| Yes | 9 (40.9) | 0 (0) | 7 (25.9) | 16 (32) |

| No | 13 (59.1) | 1 (100) | 20 (74.1) | 34 (68) |

| Responses to the question “If yes, do you know your partner's HIV and HCV status?” | ||||

| Yes | 7 (31.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (11.1) | 10 (20) |

| No | 2 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 4 (14.8) | 6 (12) |

| Response to the question “Have you had unprotected sex in the last 6 months?” | ||||

| Yes | 16 (72.7) | 0 (0) | 14 (51.9) | 30 (60) |

| No | 6 (27.3) | 1 (100) | 13 (48.1) | 20 (40) |

| Response to the question “Have you had unprotected sex with a stranger in the last 6 months?” | ||||

| Yes | 14 (63.6) | 0 (0) | 12 (44.4) | 26 (52) |

| No | 8 (36.4) | 1 (100) | 15 (55.6) | 24 (48) |

| Response to the question “Have you had unprotected anal sex in the last 6 months?” | ||||

| Yes | 10 (45.4) | 0 (0) | 6 (22.2) | 16 (32) |

| No | 12 (54.5) | 1 (100) | 21 (77.8) | 34 (68) |

| Response to the question “Have you been diagnosed with an STD in last 6 months?” | ||||

| Yes | 3 (13.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (6) |

| No | 19 (86.4) | 1 (100) | 27 (100) | 47 (94) |

| Response to the question “Have you ever had sex with someone known to be HIV or HCV positive?” | ||||

| Yes | 4 (18.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (7.4) | 6 (12) |

| No | 18 (81.8) | 1 (100) | 25 (92.6) | 44 (88) |

| Response to the question “Are you familiar with HIV Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis or PrEP?” | ||||

| Yes | 4 (18.2) | 1 (100) | 7 (25.9) | 12 (24) |

| No | 18 (81.8) | 0 (0) | 20 (74.1) | 38 (76) |

Abbreviations used: HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; POCT: point-of-care testing; STD: sexually transmitted disease.

5. Conclusions

5.1. The role of the pharmacist

Pharmacists are some of the most accessible healthcare providers and are underutilized in the current healthcare system in the U.S.29,42,43 For vulnerable populations such as individuals who are experiencing homelessness, pharmacists can play a significant role in the health management of these patients who have built a trusting relationship through coordination of care and referral.44 Individuals experiencing homelessness tend to overutilize emergency department services as their primary or only source of healthcare resulting from a lack of proactive engagement in care.45 The results of this study show that pharmacists may be in an optimal position to reverse this course and promote engagement and retention in care for vulnerable populations. In this study, the pharmacist intervention included administration of POCT, disease state education, risk mitigation counseling and referral to care. A total of 56% (n = 28) of study participants were referred to care for follow-up confirmatory testing for HIV or HCV and/or evaluation for PrEP. Of those that were referred, 71% (n = 20) of participants were confirmed to have established care through direct follow-up communication with providers. The investigators believe that the successful transitions of care seen is in part due to the rapport built between the pharmacist and the study participant during the study intervention, the respect and autonomy provided to the patient, as well as the comprehensive education and personalized risk mitigation counseling that underlies the patient-centered approach. In this study, the pharmacist investigator was not an established pharmacist at the independent community pharmacy and had no previous relationship with any study participant. The investigators believe that the benefits of this intervention would be even more pronounced where a previous relationship has already been established. With high rates of establishing care resulting from this intervention, improvements in retention may also follow secondary to the comprehensive education provided as seen with other studies.46,47

5.2. HIV and pre-exposure prophylaxis

The Department of Health and Human Services HIV clinical practice guidelines recommend ART for all persons with HIV to reduce morbidity and mortality and to prevent HIV transmission.48 With the introduction of tolerable, affordable, and highly potent antiretroviral therapies such as combination therapy with integrase strand transfer inhibitors, resistance testing for HIV is no longer a necessary precursor to starting a treatment. Rapid Start HIV treatment and the numerous benefits seen with early initiation of therapy on the same day or within 3 days of diagnosis, is a strategy to enhance ART uptake, promote engagement in care and also contributes to Treatment as Prevention.48 Proactively identifying HIV infection through testing, in conjunction with a robust referral pathway to allow for same-day or same-week follow-up, is an essential component for promoting engagement in care and minimizing lost to follow-up which can be achieved through convenient community pharmacy-led services as outlined in this study.49

Individuals at highest risk for acquiring HIV are men who have sex with men, members of the LGBTQ+ community, racial minorities and victims of sexual assault who are also disproportionately affected by homelessness.9,50,51 The risk associated with HIV transmission through sexual contact varies based on the sexual act with the highest risk being receptive anal intercourse, followed by insertive anal intercourse, receptive vaginal intercourse and lastly insertive vaginal intercourse.51 In the present study, 60% (n = 34) of participants reported unprotected sexual intercourse and 32% (n = 16) reported unprotected anal intercourse in the last 6 months. These sexual risk factors for acquiring HIV were considered along with reported drug use and ongoing level of risk of the study participant when determining eligibility and potential benefits from the use of PrEP. One participant not known to have a potential HIV infection at the time of the study intervention, had a reactive HIV POCT and was subsequently referred for follow-up confirmatory testing for HIV. Post-test counseling for a reactive HIV screening involved a detailed conversation on the limitations of the POCT and the importance of follow-up confirmatory testing for diagnosis. Along with anonymous partner notification and same day follow-up with partnering health clinics, the HIV-reactive study participant was well equipped to take a proactive approach to a potential HIV diagnosis.

PrEP using Truvada, Descovy and Apretude provide pharmacologic preventative therapy in oral or injectable dosage forms for persons that are HIV-negative and at high risk for HIV infection.52., 53., 54. Even with the introduction of new agents and removal of financial and therapeutic barriers to these preventative treatments, the utilization of PrEP for high-risk patients and treatment with ART for those with an existing diagnosis remains suboptimal.19, 20, 21. The underutilization of PrEP may be related to lack of awareness and shortcomings from healthcare providers.55 In this study, when participants were asked about their awareness of PrEP for HIV, only 28% (n = 14) indicated hearing about PrEP. None of the participants were currently taking PrEP despite 76% (n = 38) qualifying for PrEP. The study protocol is designed to promote patient autonomy and referrals were only made based on patient preference and willingness with encouragement, counseling, education, and support provided by the pharmacist. Given these limitations, 36% (n = 14) of qualifying participants agreed to a referral to be evaluated for PrEP. To reduce the rate of new HIV infections in the US, the role of community pharmacists in increasing awareness, accessibility and uptake of PrEP is of upmost importance. As of 2019, California authorized pharmacists to furnish up to a 60 days-supply of pre- and post- exposure prophylaxis to patients without a written prescription, with states such as Colorado and Oregon following suit.56., 57., 58. This is a significant advancement in the scope of practice for pharmacists, and in combination with the intervention outlined in this study, the community pharmacy setting is in a unique position to have a compelling impact on the HIV care continuum.

5.3. Hepatitis C

In this study, 44% (n = 22) of participants had a reactive HCV screening indicating potential lifetime infection. Similar to HIV POCT, for an acute or chronic HCV infection diagnosis, follow-up confirmatory testing is required after a reactive HCV antibody POCT. The rate of potential HCV infections in this study population is similar to those seen in previously published research and may be due to the high rates of reported IVDU and sharing of drug paraphernalia.4 There was a high prevalence of self-reported drug use with 94% (n = 47) of participants reporting drug use of any kind and 74% of those (n = 35) reporting injection drug use. In this cohort, methamphetamine was the most commonly injected drug followed by heroin with many participants reporting IVDU with both. An alarming 66% (n = 31) of study participants reported sharing needles for IVDU in the last 6 months which poses the highest risk for HCV transmission. Unsurprisingly, of the participants who reported sharing needles for IVDU, 86% (n = 19) also had a reactive HCV screening. Given the high rate of sharing drug paraphernalia in this population, implementation of syringe services in the community pharmacy setting can also have a significant impact on harm reduction with consideration to HIV and HCV transmission.

5.4. Mental health

Substance misuse, mental health, communicable diseases, and homelessness are closely related with considerable research suggesting that one can be the cause as well as the consequence of others.4, 5, 6, 7, 8.,59,60 It is estimated that the average prevalence of mental health conditions in the homeless population is around 76% with substance misuse being the most common diagnosis.61 In the present study, the investigators found that 92% (n = 46) of participants reported any current diagnosis of mental health condition with PTSD being the most common, followed by depression and anxiety. When participants were asked about treatment for their substance misuse and mental health conditions, approximately 72% (n = 33) of participants reported receiving treatment. Although receiving treatment for their mental health conditions is reassuring, 87% (n = 40) reported continued use of recreational drug use as a method of coping with their mental health condition. The shortcomings of available treatment options for mental health conditions, in combination with a patient population who has historically been difficult to retain in care and maintain adequate levels of adherence, has wide ranging implications for further complications such as transmission of communicable diseases like HIV and HCV. Prioritizing the treatment of psychiatric illness in this population is the key to fostering safe sex and drug use behaviors, promoting positive health outcomes, and increasing uptake of prevention strategies for related disease states such as HIV and HCV. Given the intimate relationship between communicable diseases, mental illness and substance misuse, partnering with clinics that provide mental health services is an essential component in promoting long-term engagement in care for this population. The overarching result of the intervention presented in this study shows that pharmacists in the community setting are well positioned to identify, educate, and connect at-risk individuals to care. Over half of the participants that underwent the study intervention were referred to care (56%) and of those that were referred, 71% established care as a result. Partnering clinics in this study provide holistic patient care and although patients were referred for HIV/HCV confirmatory testing or evaluation for PrEP, there is additional opportunity to also engage in mental health services and other chronic disease state management as needed.

5.5. Limitations

The results of this study must be evaluated in the context of its limitations. This study received internal college funding that allowed for a total of 50 participants to undergo the intervention. The results of the study are similar to research that has been previously published but the small sample size does limit the generalizability of the successes.3 Historically, pharmacists have indicated that staffing and infrastructure constraints limit the ability to provide more comprehensive care which still exists today.62 Of note, the pharmacist undertaking the study intervention was not employed by the independent pharmacy which limits the generalizability of this study regarding staffing. Although the pharmacist involved in implementing this study intervention is a board-certified HIV Pharmacist, the intervention can be successfully implemented by any pharmacist with adequate training in administering POCTs. The sustainability of the service is dependent on the ability of the pharmacist to bill the participant's insurance for service provided which has historically limited these types of clinical services in the community setting. Furthermore, the setting of this study was conducted in a single independent community pharmacy located downtown Spokane, Washington that services a large proportion of patients who are experiencing homelessness and struggling with mental health and substance misuse. Reproducibility of the study results in a non-urban setting may yield different results.

A significant aspect of this research was to obtain follow-up data from participants who established care to evaluate the stage of clinical infection for HIV and HCV at diagnosis and assess their course of therapy for a follow-up period of 6 months. Investigators quickly recognized a major barrier to participant involvement in the study intervention was obtaining a Medical Records Release Authorization despite reassurances of privacy. To promote participation in the study, the investigators removed the requirement for access to follow-up data from the eligibility criteria which hinders the authors' ability to evaluate retention in care. This limitation can be overcome after developing a more interconnected referral system with more robust data sharing capabilities that will be explored in future iterations of this work.

6. Summary

This study looked to evaluate the prevalence and risk factors for HIV and HCV infection in individuals with unstable housing and to assess the impact pharmacists can have on the HIV and HCV care continuum through screening, education, risk mitigation counseling and referral. Individuals experiencing homelessness are at an increased risk for acquiring HIV and HCV due to risky sexual behaviors, substance misuse and high rates of mental health conditions. PrEP is currently underutilized in the U.S. and would greatly benefit this study population with identification of eligibility and patient-specific counseling provided by pharmacists in the community setting. Study participants were highly receptive to the pharmacy-led clinical services provided and had high rates of establishing care with partnering clinics as a result of the intervention. Pharmacist involvement in the mental illness, substance misuse and the HIV/HCV care continuum can have a positive impact on improving linkage and retention in care for difficult to reach populations such as those experiencing homelessness.

Funding

This research received internal funding from a fellowship seed grant from Washington State University.

Disclosures

The authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest or financial relationships.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Sorosh Kherghehpoush, Email: s.kherghehpoush@wsu.edu.

Kimberly C. McKeirnan, Email: kimberly.mckeirnan@wsu.edu.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV Statistics Report. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/index.html Accessed 21 June 2022.

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Hepatitis C Basic Information. https://www.hhs.gov/hepatitis/learn-about-viral-hepatitis/hepatitis-c-basics/index.html Accessed 21 June 2022.

- 3.Garg S., Brooks J., Luo Q., Skarbinski J. Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA); Philadelphia, PA: 2014. Prevalence of and Factors Associated with Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Testing and Infection Among HIV-infected Adults Receiving Medical Care in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beijer U., Wolf A., Fazel S. Prevalence of tuberculosis, hepatitis C virus, and HIV in homeless people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:859–870. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70177-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gelberg L., Robertson M.J., Arangua L., et al. Prevalence, distribution, and correlates of hepatitis C virus infection among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Public Health Rep. 2012;127:407–421. doi: 10.1177/003335491212700409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Padilla M., Frazier E.L., Carree T., Luke Shouse R., Fagan J. Mental health, substance use and HIV risk behaviors among HIV-positive adults who experienced homelessness in the United States - medical monitoring project, 2009-2015. AIDS Care. 2020;32:594–599. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2019.1683808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Audain G., Bookhardt-Murray L.J., Fogg C.J., et al. Health Care for the Homeless Clinicians’ Network, National Health Care for the Homeless Council, Inc; Nashville, TN: 2013. Adapting your Practice: Treatment and Recommendations for Unstably Housed Patients with HIV/AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute on Drug Abuse Common Comorbidities with Substance Use Disorder Research Part 3: The Connection between Substance Use Disorders and HIV. https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/common-comorbidities-substance-use-disorders/part-3-connection-between-substance-use-disorders-hiv Accessed 21 June 2022. [PubMed]

- 9.HIV.gov U.S. Statistics Fast Facts. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/data-and-trends/statistics Accessed 21 June 2022.

- 10.Bull-Otterson L., Huang Y.A., Zhu W., King H., Edlin B.R., Hoover K.W. Human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus infection testing among commercially insured persons who inject drugs, United States, 2010-2017. J Infect Dis. 2020;222:940–947. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petroll A.E., DiFranceisco W., McAuliffe T.L., Seal D.W., Kelly J.A., Pinkerton S.D. HIV testing rates, testing locations, and healthcare utilization among urban African-American men. J Urban Health. 2009;86:119–131. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9339-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humphreys K., Shover C.L., Andrews C.M., et al. Responding to the opioid crisis in North America and beyond: recommendations of the Stanford-lancet commission. Lancet. 2022;399:555–604. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02252-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonfils K.A., Firmin R.L., Salyers M.P., Wright E.R. Sexuality and intimacy among people living with serious mental illnesses: factors contributing to sexual activity. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2015;38:249–255. doi: 10.1037/prj0000117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meade C.S., Sikkema K.J. HIV risk behavior among adults with severe mental illness: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:433–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Office of HIV Psychiatry HIV Mental Health Treatment Issues: HIV and People with Severe Mental Illness (SMI) https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/Professional-Topics/HIV-Psychiatry/FactSheet-SMI-2012.pdf Accessed 24 June 2022.

- 16.Ingersoll K. The impact of psychiatric symptoms, drug use, and medication regimen on non-adherence to HIV treatment. AIDS Care. 2004;16:199–211. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001641048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mellins C.A., Havens J.F., McCaskill E.O., Leu C.S., Brudney K., Chesney M.A. Mental health, substance use and disclosure are significantly associated with the medical treatment adherence of HIV-infected mothers. Psychol Health Med. 2010;7:451–460. doi: 10.1080/1354850021000015267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uldall K.K., Palmer N.B., Whetten K., Mellins C., HIV/AIDS Treatment Adherence, Health Outcomes and Cost Study Group Adherence in people living with HIV/AIDS, mental illness, and chemical dependency: a review of the literature. AIDS Care. 2004;16(suppl 1):S71–S96. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331315277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sullivan P.S., Giler R.M., Mouhanna F., et al. Trends in the use of oral emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for pre-exposure prophylaxis against HIV infection, United States, 2012-2017. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28:833–840. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gregg E., Linn C., Nace E., Gelberg L., Cowan B., Fulcher J.A. Implementation of HIV preexposure prophylaxis in a homeless primary care setting at the veterans affairs. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11 doi: 10.1177/2150132720908370. 2150132720908370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2019 National HIV Surveillance System Reports. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2021/2019-national-hiv-surveillance-system-reports.html Accessed 21 June 2022.

- 22.University of Washington Hepatitis C Online. https://www.hepatitisc.uw.edu/ Accessed 21 June 2022.

- 23.Barocas J.A., Beiser M., León C., Gaeta J.M., O’Connell J.J., Linas B.P. Experience and outcomes of hepatitis C treatment in a cohort of homeless and marginally housed adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:880–882. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schillie S., Wester C., Osborne M., Wesolowski L., Ryerson A.B. CDC recommendations for hepatitis C screening among adults — United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69(RR-2):1–17. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr6902a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gardner E.M., McLees M.P., Steiner J.F., Del Rio C., Burman W.J. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.UNAIDS Fast-track: Ending the AIDS Epidemic by 2030. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC2686_WAD2014report_en.pdf Published October 2014. Accessed 21 June 2022.

- 27.Hall H.I., Brooks J.T., Mermin J. Can the United States achieve 90-90-90? Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2019;14:464–470. doi: 10.1097/COH.0000000000000578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Viral Hepatitis National Strategic Plan for the United States: A Roadmap to Elimination (2021–2025). Washington, DC. 2020. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/Viral-Hepatitis-National-Strategic-Plan-2021-2025.pdf

- 29.Qato D.M., Zenk S., Wilder J., Harrington R., Gaskin D., Alexander G.C. The availability of pharmacies in the United States: 2007-2015. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henderson K.C., Hindman J., Johnson S.C., et al. Apr 2011. AIDS Patient Care and STDs; pp. 221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma A., Chen D.M., Chau F.M., Saberi P. Improving adherence and clinical outcomes through an HIV pharmacist’s interventions. AIDS Care. 2010;22:1189–1194. doi: 10.1080/09540121003668102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.March K., Mak M., Louie S.G. Effects of pharmacists’ interventions on patient outcomes in an HIV primary care clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:2574–2578. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang S., Britt R.B., Hashem M.G., Brown J.N. Outcomes of pharmacy-led hepatitis C direct-acting antiviral utilization management at a veterans affairs medical center. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23:364–369. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.3.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koren D.E., Zuckerman A., Teply R., Nabulsi N.A., Lee T.A., Martin M.T. Expanding hepatitis C virus care and cure: national experience using a clinical pharmacist-driven model. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6:316. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofz316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.City of Spokane Point-in-Time Count WA-502 Spokane City & City CoC. 2022. https://static.spokanecity.org/documents/chhs/hmis/reports/2022-point-in-time-pit-summary.pdf Accessed October 2022.

- 36.United States Cenus Bureau QuickFacts Spokane City. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/spokanecitywashington/PST045221 Washington. Accessed October 2022.

- 37.University of Washington National HIV Curriculum. https://www.hiv.uw.edu/ Accessed 21 June 2022.

- 38.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention A Guide to Comprehensive Hepatitis C Counseling and Testing. https://npin.cdc.gov/publication/guide-comprehensive-hepatitis-c-counseling-and-testing%E2%80%94-public-health-settings Accessed 21 June 2022.

- 39.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV Testing. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/testing/index.html Published June 2020. Accessed 21 June 2022.

- 40.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Understanding The HIV Window Period. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/hiv-testing/hiv-window-period.html Accessed 21 June, 2022.

- 41.Kherghehpoush S., McKeirnan K.C. Pharmacist-led HIV and hepatitis C point-of-care testing and risk mitigation counseling in individuals experiencing homelessness. Explor Res Clin Soc Pharm. 2021;1:10007. doi: 10.1016/j.rcsop.2021.100007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wertheimer A.I. The underutilized pharmacist. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2018;9:77. doi: 10.1111/jphs.12234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kibicho J., Pinkerton S.D., Owczarzak J., Mkandawire-Valhmu L., Kako P.M. Are community-based pharmacists underused in the care of persons living with HIV? A need for structural and policy changes. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;2015(55):19–30. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2015.14107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnsen S., Cuthill F., Blenkinsopp J. Outreach-based clinical pharmacist prescribing input into the healthcare of people experiencing homelessness: a qualitative investigation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:7. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-06013-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sun R., Karaca Z., Wong H.S. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Rockville (MD): October 2017. Characteristics of homeless individuals using emergency department services in 2014: Statistical brief #229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Henderson K.C., Hindman J., Johnson S.C., Valuck R.J., Kiser J.J. Assessing the effectiveness of pharmacy-based adherence interventions on antiretroviral adherence in persons with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25:221–228. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tseng A., Foisy M., Hughes C.A., et al. Role of the pharmacist in caring for patients with HIV/AIDS: clinical practice guidelines. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2012;65:125–145. doi: 10.4212/cjhp.v65i2.1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.HIV.gov. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents Living with HIV. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-arv/initiation-antiretroviral-therapy?view=full Accessed 24 June 2022.

- 49.Grimsrud A., Wilkinson L., Eshun-Wilson I., Holmes C., Sikazwe I., Katz I.T. Understanding engagement in HIV programmes: how health services can adapt to ensure no one is left behind. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2020;17:458–466. doi: 10.1007/s11904-020-00522-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hwang S.W. Homelessness and health. CMAJ. 2001;164:229–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Public Health Agency of Canada Infectious Disease Prevention and Control HIV Transmission Risk: A Summary of the Evidence. https://www.catie.ca/sites/default/files/HIV-TRANSMISSION-RISK-EN.pdf Accessed 21 June 2022.

- 52.Truvada Information for Healthcare Providers. https://www.truvadahcp.com/ Accessed 21 June 2022.

- 53.Descovy Information for US Healthcare Professionals. https://www.descovyhcp.com/ Accessed 21 June 2022.

- 54.Apretude Healthcare Providers Information. https://apretudehcp.com/ Accessed 21 June 2022.

- 55.Yusuf H., Fields E., Arrington-Sanders R., Griffith D., Agwu A.L. HIV preexposure prophylaxis among adolescents in the US: a review. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:1102–1108. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Senate Bill 159 California Legislative Information. https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201920200SB159 Published October 8, 2019. Accessed October 28, 2022.

- 57.HB20–-1061 Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection Prevention Medications Colorado General Assembly. https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb20-1061 Accessed October 28, 2022.

- 58.2021 Regular Session House Bill 2958 Oregon State Legislature. https://olis.oregonlegislature.gov/liz/2021R1/Measures/Overview/HB2958 Accessed October 28, 2022.

- 59.Nationalhomeless.org National Coalition for the Homeless. https://nationalhomeless.org/ Accessed 24 June 2022.

- 60.Polcin D.L. Co-occurring substance abuse and mental health problems among homeless persons: suggestions for research and practice. J Soc Distress Homeless. 2016;25:1–10. doi: 10.1179/1573658X15Y.0000000004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gutwinski S., Schreiter S., Deutscher K., Fazel S. The prevalence of mental disorders among homeless people in high-income countries: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Med. 2021;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McKeirnan K., Kherghehpoush S., Gladchuk A., Patterson S. Addressing barriers to HIV point-of-care testing in community pharmacies. Pharmacy (Basel) 2021 Apr 16;9:84. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy9020084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]