Abstract

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a heterogenous and challenging hematological malignancy with suboptimal outcomes. The implications of advanced technologies in the genetic characterization of AML have enhanced the understanding of individualized patient risk, which has also led to the development of new therapeutic strategies. A comprehensive study of novel mutations is essential to moderate the complicacies in patient management and achieve optimal outcomes in AML. In this review, we summarized the clinical relevance of important novel mutations, including TET2, ETV6, SATB1, EZH2, PTPN11, and U2AF1, which impact the prognosis of AML. TET2 mutation can lead to DNA hypermethylation, and gene fusion, and mutation in ETV6 disrupts hematopoietic transcription machinery, SATB1 downregulation aggravates the disease, and EZH2 mutation confers resistance to chemotherapy. PTPN11 mutation influences the RAS-MAPK signaling pathway, and U2AF1 alters the splicing of downstream mRNA. The systemic influence of these mutations has adverse consequences. Therefore, extensive research on novel mutations and their mechanism of action in the pathogenesis of AML is vital. This study lays out the perspective of expanding the apprehension about AML and novel drug targets. The combination of advanced genetic techniques, risk stratification, ongoing improvements, and innovations in treatment strategy will undoubtedly lead to improved survival outcomes in AML.

Keywords: Acute myeloid leukemia, genetic mutations, next-generation sequencing, risk-stratification, targeted therapy, survival

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia is a myeloid dysplastic malignancy of hematopoietic stem cells. This disease is presented in children and adults with considerable diversity in molecular pathogenesis and disease outcomes [1]. Cytogenetic abnormalities are more common in pediatric AML (p-AML) than in adult AML, with some of them appearing exclusively in newborns and young children. Additionally, there are significant differences between the epigenetic landscapes of pediatric and adult AML in terms of the frequency and type of mutations in epigenetic modulators [2]. Despite the great degree of heterogeneity, many gene fusions and point mutations are recurrent and have been employed in risk stratification for the past three decades. However, the implication of advanced techniques like karyotyping, chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA), and next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revealed newer mutations, which have diagnostic and prognostic significance.

Acute myeloid leukemia constitutes 15-20% of childhood leukemia and approximately 35% of adult leukemia [3]. The survival rate of AML remains dismal, and there is insufficient understanding of the basis of poor outcomes in AML. However, chromosomal abnormalities like AML-ETO t(8;21), PML-RARA t(15;17), CBFB-MYH11 t(16;16), FLT3-ITD and mutations in CEBPA, KIT, NPM1, and ASXL1 are commonly reported in p-AML and is used in risk stratification on the basis of overall survival and relapse rate. The implication of advanced molecular techniques in diagnosis has revealed new mutations that may have prognostic value.

Recently, there have been significant advancements in the diagnostics of AML and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), including the integration of NGS strategies into establishing diagnostic algorithms, classification and risk stratification systems, and detection of minimal residual disease (MRD). With the availability of more specific treatments for AML (such as FLT3 or IDH1/IDH2 inhibitors), prompt and thorough genetic mutation screening has become a necessary practice [4].

Genetics and mutations in AML

Traditionally, classifying patients with AML into favorable, intermediate, and adverse risk categories entail cytogenetic markers. However, due to the complexity of the disease genetics in patients with normal karyotypes, risk stratification and treatment decision become difficult. Hence high-throughput techniques are implied to identify clinically relevant mutations [5]. The two-hit mutation model proposed by Gilliland and Griffin in 2001 classifies the key oncogenic mutations [6]. It is hypothesized that AML, is a repercussion of a collaboration between at least two broad classes of mutations, wherein Class I mutations confer proliferative, and survival advantages and Class II mutations affect the processes of cell differentiation and apoptosis. Some mutations, mainly epigenetic modifiers, are not identified in these two classes. World Health Organization (WHO), proposed a new classification which uses clinical, morphological, and genetic features to classify different subgroups: AML with recurrent genetic abnormalities, AML with myelodysplastic-related changes, AML therapy-related myeloid neoplasms, and AML without any other specification, which generally is classified on the basis of the FAB [7].

Some of the primarily mutated genes are KIT, FLT3, NPM1, CEBPA, RAS, WT1, BAALC, ERG, MN1, DNMT, TET2, IDH, ASXL1, PTPN11 and CBL. Amongst these, FLT3, NPM1, and CEBPα genes are well studied to be associated with treatment response and disease progression (Table 1) [8-10]. Epigenetic modifiers include DNA methyltransferases: DNMT1, DNMT3A and DNMT3B; methylcytosine dioxygenase: TET1, TET2 and TET3 convert 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) [11,12].

Table 1.

Genetic mutations in acute myeloid leukemia (AML)

| Common mutations | Incidence | References | Novel mutations | Incidence | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||

| Adult | Pediatric | Adult | Pediatric | ||||

| NPM1 | 35% | 8-10% | [13] | CTNNB1 | 22% | 1.8% | [14,15] |

| DNMT3A | 20% | 2.1% | [16,17] | SRSF2 | 12.5% | <1% | [18], TARGET |

| RUNX1 | 10-15% | ~2.8% | [5,19] | PTPN11 | 4% | 6.9% | [20,21] |

| CEBPA | ~10% | 18% | [5,22] | PHF6 | 3% | 2% | [23,18] |

| TP53 | 10% | 2.1% | [24,25] | U2AF1 | 3.4% | <1% | [26], TARGET |

| GATA2 | ~5% | 2.6% | [5] | ETV6 | 1.35% | 2.2% | [27,28] |

Profound mutations in AML

The advent of techniques and their implication in clinical diagnostics has led to the revelation of the most common mutations causing the disease. Risk stratification and estimation of drug response are dependent on these established genetic factors. The favorable group comprises mutations in NPM1 (30% in adults) [29] and CEBPA (10%) [30]. Mutations in ASXl1 (6.5%) and TP53 (8%) [31] present with poor prognosis [32]. A few other mutations, such as PTPN11, NRAS, KRAS, NF1, GATA2, TET2, and DNMT3A, are frequently observed in AML, but the prognosis of these mutations is still undefined [5]. The recent guidelines by European LeukemiaNet (ELN), 2022 have included mutations in BCOR, EZH2, SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1, and/or ZRSR2 under the category of adverse risk (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characterization of recurrent genetic mutations according to the recommendation by ELN, 2022

| Risk group | Mutations |

|---|---|

| Favourable | ·Mutated NPM1 |

| ·bZIP in-frame mutated CEBPA | |

| Intermediate | ·Mutated NPM1 with FLT3-ITD |

| ·Wild-type NPM1 with FLT3-ITD (without adverse-risk genetic lesions) | |

| ·Cytogenetic and/or molecular abnormalities not classified as favorable or adverse | |

| Adverse | ·Mutated ASXL1, BCOR, EZH2, RUNX1, SF3B1, SRSF2, STAG2, U2AF1, and/or ZRSR2 (in absence of favourable risk subtype) |

| ·Mutated TP53 |

The development of disease and its response to the therapy is a repercussion of the altered gene function and its following molecular pathway. Various molecular pathways play a crucial role in maintaining cellular processes; any aberration in these pathways leads to the dysregulation of cellular differentiation and division, ultimately causing malignancy like AML [33]. Signal transducers, epigenetic modifiers, transcription factors, splicing factors, and cohesion complexes are directly or indirectly involved in the disease pathogenesis [34]. A profound understanding of the disease is required to improve the prognosis of AML, which necessitates the further elaboration of consequences linked to mutations with lower prevalence and undefined significance.

In this study, we have performed a comprehensive survey of the literature available on AML (pediatric and adults). We have also, utilized the TARGET database for sequencing data of pediatric patients. Several unexplored and uncategorized mutations were recognized, which lacked prognosis analysis. MYO18, PHF6, SRSF2, CTNNB1, CCND2, EPOR, SF3B1, SMC3, and SETB1 are genes reported in various research studies prevailing in patients of AML. The nature of this disease is heterogenous with high mortality and relapse rate. Despite the availability of risk stratification criteria, the disease outcome remains variable primarily for the intermediate risk class, which is a poorly understood heterogeneous group. Hence, the need for understanding uncommon recurrent mutations is indispensable. Here, we have presented a comprehensive review of such potential mutations, which may have ramifications for improving clinical practices and finding novel drug targets.

Current diagnostic and treatment strategies for AML

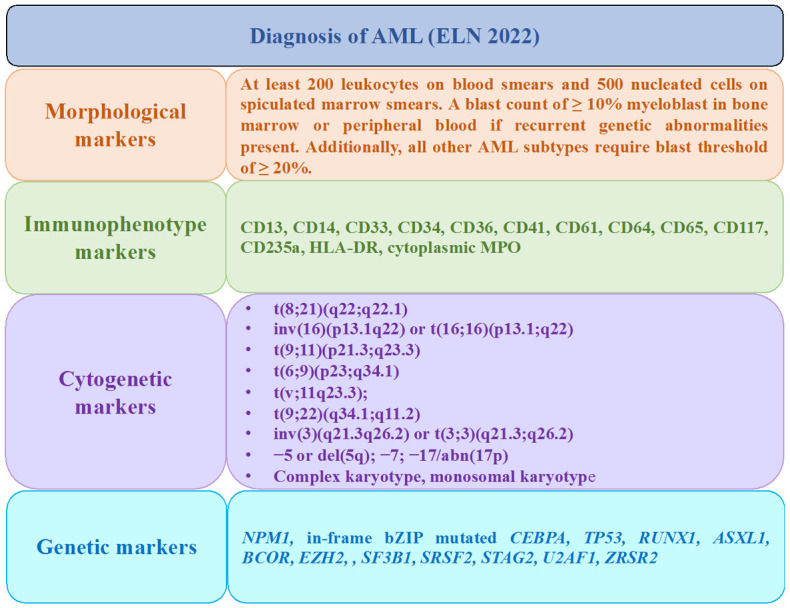

The diagnosis of AML is confirmed by the presence of ≥10% blast cells in peripheral blood or bone marrow with the presence of most common cell surface markers CD33, CD34, CD13, and HLA-DR and recurrent genetic abnormality. Core binding factor (CBF) AML is the most common subtype of AML as t(8;21) (RUNX1-RUNX1T1) and inv(16) (CBFB-MYH11) constitutes 25% of pediatric AML and 15% adult AML cases [35]. Other cytogenetic abnormalities such as t(6;9) (DEK-NUP214) and t(9;22) (BCR-ABL) have relatively lower incidence rates but are associated with poor outcomes of the disease (Figure 1). The genetic aberration in RUNX1, ASXL1, and TP53 are associated with adverse risk [32].

Figure 1.

AML detection markers recommended by European LeukemiaNet (ELN), 2022.

The therapy of AML includes a combination of daunorubicin and cytosine arabinoside (7+3) or cytosine arabinoside, daunorubicin, and etoposide (10+3+5) chemotherapeutics. Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APML) comprises 5-10% of AML cases demarked by the presence of t(15;17) and is treated with all-trans-retinoic acid (ATRA) and arsenic trioxide with a high remission rate (80-90%) [36]. Although these treatment approaches have the potential to reduce the burden of leukemia, the disease’s prognosis is still not optimal because of poor tolerance, a higher risk of induction mortality in patients with concomitant conditions, unfavorable cytogenetics, and molecular mutations. The prognosis of AML varies with age, as adults typically have a worse outcome as compared to pediatric AML. The OS in adults is suboptimal at 40-45%. Whereas, the pediatric population has a better OS and EFS (70-75% and 60-65%, respectively). Complete remission (CR) rates in paediatric AML are 85-90% and 60-70% in adults. The relapse rates within three years account for 40% of pediatric AML and 60% of adult AML [37-39].

The FDA’s recent approval of therapeutics in 2017-18 encouraged the development of novel targeted compounds with therapeutic potential. AML with an FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) mutation that was newly diagnosed has been demonstrated to respond effectively to the multi-kinase inhibitor midostaurin. It cannot be overstated how important Smoothened (SMO), a component of the hedgehog (Hh) signaling system, is for the growth, and maintenance of leukemic stem cells (LSC). LSCs offer resistance to chemotherapy and raise the likelihood of relapse. Glasdegib effectively targets this pathway to increase the survival outcome [40].

Mutations with unknown significance

It has been summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Novel mutations and their association with prognosis in AML

| Study (references) | Functional category | Novel mutations | Study Population | EFS (HR) | OS (HR) | Overall Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al., (2019) [96]; | Methylcytosine dioxygenase | TET2 | Adult | HR: 1.594 | HR: 1.386 | Poor |

| Langemeijer et al., (2010) [97]; | (P=0.002) | (P<0.001) | ||||

| Kaburagi et al., (2019) [98] | Pediatric | 54.5% | 77.9% vs. 75.9% | Poor | ||

| P=0.907 | P=.688 | |||||

| Haferlatch et al., (2012) [99] | Transcription Factor | ETV6 | Adult | 4.0 vs. 15.4 months | 26.3 vs. 62.2 months | Poor |

| Pediatric | - | - | ||||

| Wnt signaling Pathway, cell adherens junctions | CTNNB1 | P<0.05 | Poor | |||

| Chromatin remodeling factor | SATB1 | Poor | ||||

| Stasik et al., 2021 [21]; | Signal transducer (RAS/MAPK pathway) | PTPN11 | Adult | HR: 1.52; P=0.013 | HR: 1.75; P<0.001 | Poor |

| Loh et al., 2004 [100] | Pediatric | No change | No change | |||

| Ohgami et al., (2015) [42]; | Splicing factor | U2AF1 | Adult | P<0.0001 | Median 3 months vs. 7 months | Poor |

| Li et al., [101] | Pediatric | - | - | |||

| Patel et al., (2012) [93] | Transcription Factor | PHF6 | Adult | P=0.006 | Poor |

TET2

TET2 protein catalyzes the conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and somatic loss of mutations in the Ten-Eleven Translocation (TET2) gene supposedly alter hematopoietic stem cell functions and development by epigenetic modifications [41,42]. TET2 mutation is observed in 23% of patients, and according to the European LeukemiaNet (ELN) classification of AML, TET2 mutations are associated with a favorable-risk group but inferior outcome [43]. Figueroa et al. (2010) [44] and Dang et al. (2009) [45] described the mutual exclusion of TET2 mutations with the mutation in IDH1 and IDH2. Contextually, a mutation in IDH1 deregulates the conversion of isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate; instead, NADPH-dependent reduction of α-ketoglutarate to 2-hydroxyglutarate is catalyzed, which inhibits TET2 activity [44-46]. Exon 3 and exon 11 are reported to be more labile to mutations in AML patients. In contrast, the density of mutations is highest in exon 5-9 [41], and it leads to overall DNA hypermethylation in the enhancer region [47].

ETV6

ETV6 or TEL encodes for transcription repressor and has been reported to be a gene fusion partner with more than 30 translocation oncogenes [48]. It has a crucial role in embryonic development and hematopoiesis [49]. ETV6 has three domains: C-terminal DNA binding (ETS) domain, central regulatory domain, and N-terminal pointed (PNT) domain which provides oligomerization motif for fusion with other partners, especially with kinases and leads to constitutive activation of gene fusion transcription factor [50]. Doorn-Khosrovani et al. described that despite the presence of wild-type ETV6, low protein level was transcribed with no relation to mRNA expression level [51]. In de novo pediatric AML, 2.2% of patients had mutations altering ETV6 amino acid sequence, deletion was observed in 1.5% and 9.2% of patients had MNX1/ETV6 translocation. MNX1-ETV6 t(7;12)(q36;p13) translocation is reported to be associated with poor prognosis and is enriched in the infantile group [28]. ETV6 aberrations result in poor outcomes of disease in children and a higher risk of relapse [52].

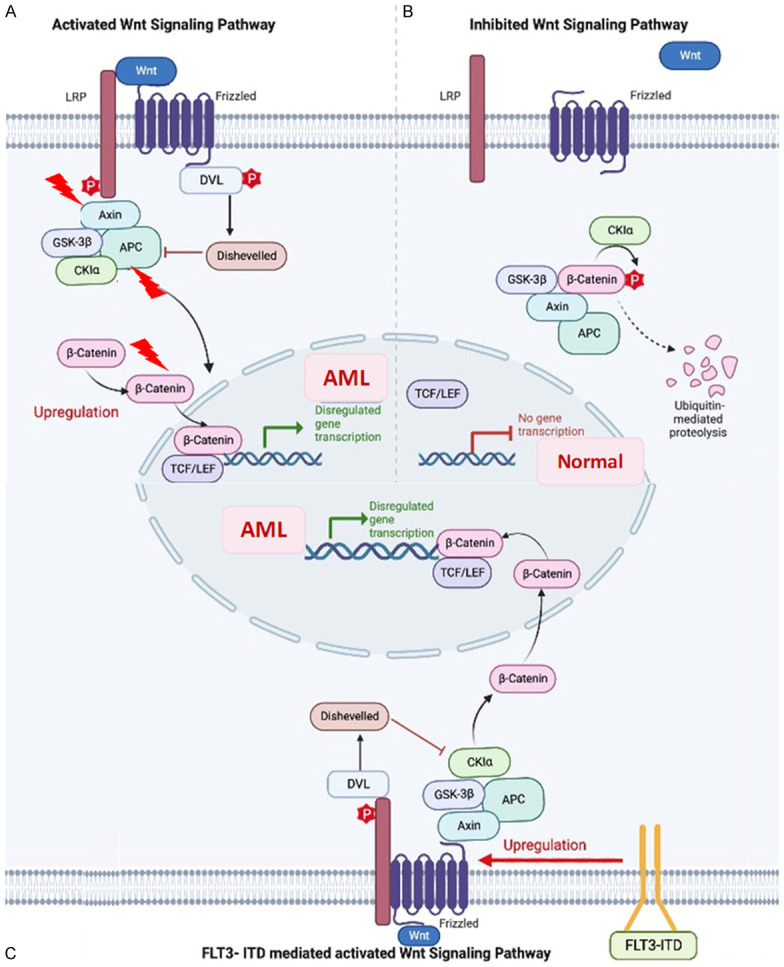

CTNNB1

CTNNB1, which encodes for β-catenin, is a central role player in cell development and defining differentiation fate during embryogenesis through the Wnt signalling pathway and cell-cell adhesion [53,54]. Wnt signalling pathway is primarily involved in the regulation of developmental processes, cell growth, and differentiation [55,56], which can be canonical (β-catenin dependent) or non-canonical (β-catenin independent). Upon activation of the canonical Wnt pathway, β-catenin is hypophosphorylated and stabilized. The canonical pathway is shown to lead to hematopoiesis failure associated with loss in a commitment of myeloid lineage at the granulocyte-macrophage progenitor stage (Figure 2); moreover, it blocks erythrocyte differentiation and lymphoid development facilitating loss of repopulating stem cell activity hence causing hematopoietic crisis [57,58]. β-catenin is evidently linked to clonogenicity of blast cells in AML [59]. Quantitative analysis of CTNNB1 mRNA depicted up to 100-fold upregulation in AML patients which is highly suggestive of its role in disease-related myeloproliferation [53]. In the Chinese population, lower overall survival was observed with high CTNNB1 expression [57]. According to TARGET, deep deletion in CTNNB1 is prevalent in 1.8% of the pediatric population. Griffiths et al. showed β-catenin as an independent prognostic factor and indicator of poor event-free survival (EFS) and OS [15].

Figure 2.

β-catenin stabilization mechanism leading to abnormal hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) proliferation. A. Wnt binding to Frizzeled (fzd) receptors and with Lipoprotein receptor-related proteins 5/6 (LRP5/6) co-receptors, activates the signalling pathway leading to the stabilization of β-catenin additionally, the mutations in Axin, adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), and β-catenin genes can impair the downregulation of β-catenin which leads to dysregulated gene transcription and abnormal HSC differentiation. B. Normal gene transcription by phosphorylation of β-catenin and its subsequent ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. C. Pathway of AML pathogenesis, in the presence of FLT3-ITD (Internal Tandem Duplication) mutations induced FZD expression and increased β-catenin nuclear localization.

SATB1

Special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 1 (SATB1), is a chromatin remodeller which modulates gene expression in different types of cancer. Upregulation of SATB1 is reported to be linked with the progression of the tumor, metastatic potential, and poor prognosis. Luo et al., identified reduced expression of SATB1 in AML patients which consecutively the expression increased in CR (P=0.03), indicative of its role in disease progression and potential as a biomarker for drug response. In this study, adult AML patients (n=52) were categorized into SATB1 high and SATB1 low, with CR rates of 76.5% and 56.1%, respectively. Additionally, they suggested SATB1 regulates various genes involved in hematopoietic cell differentiation and development [60]. There are studies that suggest the role of SATB1 as a regulator of lymphocyte differentiation and additionally, its contribution is predicted to regulate Wnt signalling genes through interaction with β-catenin [60]. Bachas et al., reported SATB1 deregulation in AML relapse (95.7%; 22 out of 23 cases) [61].

PTPN11

The tyrosine-protein phosphatase nonreceptor type 11 (PTPN11) has two N-terminal Src homology 2 (SH2) domains, a protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP) catalytic domain, and a COOH terminus [62]. It encodes for cytoplasmic phosphatase SHP2, which is a crucial role player in cell growth, and cell differentiation and serves as a signaling component to positively regulate RAS/MAPK signaling pathways [63,64]. RAS signaling molecules are frequently observed to be mutated with AML. In a study by Stasik et al., mutation analysis using NGS revealed PTPN11 mutations in 106 of 1529 (6.93%) patients (median VAF: 24%) in dominant (36%) and subclonal (64%) configuration. As per their study, PTPN11 mutations presented with NPM1 (63%), DNMT3A (37%), and NRAS (21%) and had a higher rate of co-occurrence of favorable cytogenetics (57.8% vs. 39.1%; P<0.001) with adverse effect in patients with subclonal PTPN11 mutations (HR: 2.28; P<0.001) but not found with dominant PTPN11 mutations (HR: 1.07; P=0.775). Patients with PTPN11 mutations had poor OS (HR: 1.75; P<0.001), relapse-free survival (RFS) (HR: 1.52; P=0.013), and a lower rate of CR (odds ratio: 0.46; P=0.008) [21]. Somatic gain-of-function mutations in N-SH2/PTP domains prevent the autoregulation of SHP2 catalytic activity during leukemogenesis. Upregulation of SHP2 was found to cause leukemic transformation by increasing hematopoietic progenitor cells’ sensitivity to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and the RAS signaling axis [65-67]. Patients with juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia (JMML) frequently have somatic PTPN11 mutations, and certain other hematologic malignancies have also been associated with this mutation [68] but its association with pediatric AML is not well understood [69]. Alfayez M et al. studied adult patients with AML (N=1406), 112 (8%) had PTPN11mut, which showed results similar to other published studies [21]. They showed an association of PTPN11mut with lower CR rates (54% vs. 40%; P=0.04), and shorter OS (median 13.6 vs. 8.4 months; P=0.008) [70].

U2AF1

Mutations of the splicing machinery are recurrent and specific to myelodysplastic diseases, therapy-related AML, or AML with myelodysplasia-related changes (25.8%), but comparatively uncommon in de novo AML (6.6%) [71]. A noncanonical function of U2 small nuclear RNA auxiliary factor 1 (U2AF1) is reported, it directly binds to mature mRNA in the cytoplasm to negatively regulate mRNA translation. Mutation in U2AF1 affects the splice site selection. The most frequent change in S34F region, alters a conserved nucleic acid-binding domain, recognition of the 3’ splice site, and alternative splicing of many mRNAs. One functional repercussion of alteration in this splicing-independent role is increased synthesis of the secreted chemokine interleukin 8, which promotes metastasis, inflammation, and the growth of cancer in mice and humans [72].

Somatic mutations of the U2AF1 gene have recently been discovered in myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and AML. Qian et al. investigated U2AF1 mutations in Chinese patients with myeloid neoplasms (n=452). In this study, mutations in U2AF1 were recognized in 2.5% (7/275) of AML, which were heterozygous missense mutations in two highly conserved amino acid positions S34 or Q157 [73]. The OS of AML patients affected by mutation was shorter than those without mutation (median seven months) (P=0.035). This study projected that U2AF1 mutation is a recurrent but less frequent event. Patients with U2AF1 mutations had an increased probability of progression of MDS to AML. MDS is reported to progress to AML (MDS/AML) within a few months [74,75]. High-throughput sequencing was implied to identify mutations in 58 genes with known clinical significance in 99 patients with de novo MDS or MDS/AML, and U2AF1 was found to be the most frequently mutated gene (13.6%; 29/214) [76]. U2AF1 mutation has a poor prognosis in AML [42]. A study suggested that alterations in the U2AF1 gene are an uncommon event in pediatric AML, implying that the driver effect of its mutation is unlikely in myeloid leukemogenesis [77].

In a study by Venkatasubramanian et al., “U2AF1-covarying” or “SRSF2-covarying” (CV) had an independent occurrence of splicing-factor mutations, which are principally linked to mis-splicing rather than differential gene expression. U2AF1-CV splicing events are linked to canonical rather than changed U2AF1 binding specificity, in contrast to patients with U2AF1-S3F mutations. In both adult and pediatric cohorts, U2AF1-CV splice events, resulting from an inclination toward longer protein isoforms, have significantly worse outcomes (poor survival and increased relapse). Similar outcomes are observed during relapse in adults [78].

EZH2

The histone lysine N-methyltransferase (EZH2) is the enzymatic component of the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) that regulates stem cell maintenance and differentiation [79,80]. Various studies have defined the heterogeneous nature of EZH2 with a prevalence of 1-5% in AML patients [21,81-83]. Mutations in the gene can be frameshift, nonsense, or missense mutation, whereas truncating mutations are spread throughout the gene. Missense mutations are most prevalent in evolutionarily highly conserved residues in domain II and the CXC-SET domain [84]. In myeloid disorders, EZH2 mutations are found to be inactivating, which suggests the essentiality of the balance of polycomb activity for normal stem cell activity [85]. The correlation of low EZH2 protein levels with poor prognosis in AML patients and failure of consolidation therapy (P=0.004) is suggested in various studies [21,82,86,87]. Göllner et al. showed that a reduction in EZH2 level and histone H3K27 trimethylation led to resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and cytotoxic drugs in AML. Loss of EZH2 protein occurred in about 45% of relapsed AML patients in this study. Various other mechanisms have been mentioned in the literature wherein a decrease in EZH2 mRNA and/or protein levels is associated with the deletion of 7/7q chromosome. Furthermore, dysfunction of splicing by mutations in spliceosomal genes such as U2AF1 or SRSF2 has been related to reduced EZH2 mRNA expression in 10-25% of AML patients [50,88,89]. EZH2 protein expression, analyzed by immunohistochemical staining, showed a significant correlation with poor OS (P=0.008), poor EFS (P=0.005), and poor RFS (P=0.047) [82]. Furthermore, a significant association between the most mutations in E640 K (P=0.049) and E644 K (P=0.047) and chemotherapy resistance after the consolidation phase has been reported [87].

Contrastingly, overexpression of EZH2 has been reported with a high risk in MDS, MDS-derived AML, and AML patients [90]. In a parallel study, 13 out of 714 (1.8%) AML patients were diagnosed with EZH2 mutation and significant association with low blast percentage (21-30%) in bone marrow (P<0.0001) and -7/del(7q) (P=0.025). However, no variance was observed in CR, EFS, or OS between patients with and without EZH2 mutation (P>0.05) [81]. In a different cohort of EZH2-mut AML patients, significantly greater co-occurrence rates were found with RUNX1 (25%), ASXL1 (22%), and NRAS (25%), and comparable results were reported by Kempf et al. [83]. The shorter median OS (12.55 vs. 15.61 months) and RFS (8.15 vs. 17.29 months) were observed for patients with homozygous mutations in comparison to heterozygous mutations. EZH2 mutations are recurrent alterations in patients with AML. However, data implicated the poor potential of EZH2 mutations as an independent prognostic factor in AML [88].

PHF6

An X-linked gene, PHD-finger protein 6 (PHF6), is a tumor suppressor gene that encodes a plant homeodomain (PHD) protein. PHD contains four nuclear localization signals and two imperfect PHD zinc finger domains. It has a suggested role in transcriptional regulation and/or chromatin remodelling [91]. Jalnapurkar SS et al. reported PHF6 mutation in 10 out of 353 AML patients (3%). This gene is reported to be mutated in 3.2% of de novo AML, 4.7% of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), 3% of MDS, and 1.6% of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients. Frameshift and nonsense mutations constitute two-thirds of somatic gene lesions in PHF6, resulting in loss of PHF6 protein. Also, point mutations are clustered in ePHD2 (extended PHD) with unknown functional consequences. A chromatin-binding protein PHF6, binds to key myeloid transcription factors through ePHD domains and restricts AML progression. R274Q mutation in PHF6 enables it to regulate downstream signaling describing a vital role in hematopoiesis [23,92].

PHF6 mutations were identified in 2% of pediatric AML patients, majorly affecting the male population. In a different study, the pediatric de novo AML cohort was enriched in FAB-M0, M1, and M2 lower PHF6 mRNA expression, and the prevalence was persistent as former study. Accordingly, the presence of loss-of-function mutations in PHF6 in pediatric AML indicates its role in leukemogenesis. Mutations in PHF6 are associated with reduced OS (P=0.006) [93]. Investigation of concomitant mutations with PHF6 mutation revealed significant association with RUNX1, U2AF1, SMC1A, ZRSR2, EZH2, and ASXL1 [94,95].

The cytogenetic analysis serves as the basis for AML classification into the favorable, intermediate, or adverse group associated with 5-year OS of ~60%, 30% to 40%, and 5% to 10%, respectively [5]. The advent of NGS approaches, has deciphered a new depth of information, >95% of AML cases are reported to possess at least one somatic mutation, which provides prognostic information of otherwise intermediate-risk cytogenetics [93,102]. The novel mutations bring a new opportunity for researchers and clinicians to treat the disease with a personalized approach. A synthetic molecule-based splicing inhibitor therapy for targeting splicing inhibitors has been postulated for increasing treatment efficacy [103]. Small molecule splicing modulator (H3B-8800) is undergoing a phase 1 trial specifically for patients with hematologic malignancies (#NCT02841540). The aberration in Hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway affects the differentiation of leukemia stem cells, and its upregulation imparts resistance to chemotherapy in AML cells. Glasdegib acts as an oral inhibitor that interacts with SMO in the Hh pathway. In its randomized phase 2 study, the combination of low-dose cytosine arabinoside (LDAC) and Glasdegib is administered to de novo AML or high-risk MDS patients and has shown to improve OS (8.3 months vs. 4.3 months, HR 0.51; 80% CI, 0.39-0.67, P=0.0004) and CR (15% vs. 2.3%) [104]. Likewise, C-82 mediated disruption of Wnt/β-catenin signaling suppressed growth, induced apoptosis, and overcame stromal protection of cancerous and stem/progenitor cells [105].

Authors’ view: Although the treatment procedure has been improved over the years, there is still a significant gap between treatment and improving survival. As a result, the adoption of improved diagnostic tools and targeted medications with minimal toxicity and off-site specificity is becoming progressively vital for early care. Furthermore, more precise risk stratification is required, including mutations and differential expression of pathways. The novel mutations might not have a high prevalence, but the recurrence influences the outcome with or without any other genetic abnormality.

Albeit, AML is a heterogenous malignancy with a dismal outcome, its pathogenesis and biology are poorly understood; however, advancement in technologies has made risk stratification-based treatment to decrease treatment-related toxicity. There is a lot of research that needs to be done to gain knowledge for the novel targeted therapy to make easy access to every needy patient and to make improvements in the outcome of AML. The persistence of epigenetic factor mutations may lead to clonal evolution in chemorefractory cells and leading to chemo-resistance and recurrence of AML. A deeper comprehension of the molecular mechanisms driving chemotherapy resistance must serve as the foundation for the development of revolutionary therapeutic approaches for pediatric AML. Integrative genomic investigations that combine DNA sequencing, DNA copy number analysis, transcriptional profiling, and functional genetic techniques show considerable promise for uncovering other anomalies in AML that are essential for leukemogenesis and can be employed therapeutically. In the future, it may be possible to increase the survival rate in AML patients by using pathogenesis-focused drug combinations.

Conclusion

AML is a rigorous malignancy of hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) characterized by differentiation arrest and uncontrolled clonal proliferation of precursor cells. In traditional clinical practice, history, cell morphology, immunophenotype, cytogenetic studies, and molecular analyses play integral roles in creating diagnosis and risk classification. The exploitation of high-throughput data can provide more targeted solutions to disease complications and prevent secondary recurrence events. Identification of the pathogenic potential of recurrent mutations like TET2, SATB1, PTPN11, U2AF1 and EZH2 lays out provisions for novel drug targets which can be used in combination with common drugs. Refractory disease or relapse highlights the intricacy of AML, and the therapy has its own complicacies. Consequently, additional studies with the discovery of novel drug targets are necessary to achieve new milestones in clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the authors who published their studies related to genetic mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. We also acknowledge All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi, which provided us to work in the field of acute myeloid leukemia.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Abbreviations

- AML

Acute myeloid leukemia

- CI

Confidence interval

- CR

Complete remission

- CTNNB1

Catenin Beta 1

- ETV6

ETS Variant Transcription Factor 6

- CMA

Chromosomal microarray analysis

- EFS

Event free survival

- EZH2

Enhancer of zeste 2 polycomb repressive complex 2

- HR

Hazard risk

- NGS

Next-generation sequencing

- PTPN11

Protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 11

- PHF6

PHD-finger protein 6

- OS

Overall survival

- RFS

Relapse free survival

- SATB1

Special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 1

- TET2

Tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2

- U2AF1

U2 small nuclear RNA auxiliary factor 1

References

- 1.Foran JM. New prognostic markers in acute myeloid leukemia: perspective from the clinic. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2010;2010:47–55. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2010.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaudhury S, O’Connor C, Cañete A, Bittencourt-Silvestre J, Sarrou E, Prendergast Á, Choi J, Johnston P, Wells CA, Gibson B, Keeshan K. Age-specific biological and molecular profiling distinguishes paediatric from adult acute myeloid leukaemias. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5280. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07584-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Creutzig U, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Gibson B, Dworzak MN, Adachi S, de Bont E, Harbott J, Hasle H, Johnston D, Kinoshita A, Lehrnbecher T, Leverger G, Mejstrikova E, Meshinchi S, Pession A, Raimondi SC, Sung L, Stary J, Zwaan CM, Kaspers GJ, Reinhardt D AML Committee of the International BFM Study Group. Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in children and adolescents: recommendations from an international expert panel. Blood. 2012;120:3187–3205. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-362608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shumilov E, Flach J, Kohlmann A, Banz Y, Bonadies N, Fiedler M, Pabst T, Bacher U. Current status and trends in the diagnostics of AML and MDS. Blood Rev. 2018;32:508–519. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiNardo CD, Cortes JE. Mutations in AML: prognostic and therapeutic implications. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016;2016:348–355. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2016.1.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reilly JT. Pathogenesis of acute myeloid leukaemia and inv(16) (p13;q22): a paradigm for understanding leukaemogenesis? Br J Haematol. 2005;128:18–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vardiman JW, Harris NL, Brunning RD. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of the myeloid neoplasms. Blood. 2002;100:2292–2302. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi S. Current findings for recurring mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2011;4:36. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-4-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martelli MP, Sportoletti P, Tiacci E, Martelli MF, Falini B. Mutational landscape of AML with normal cytogenetics: biological and clinical implications. Blood Rev. 2013;27:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubnitz JE, Gibson B, Smith FO. Acute myeloid leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2010;24:35–63. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shih AH, Abdel-Wahab O, Patel JP, Levine RL. The role of mutations in epigenetic regulators in myeloid malignancies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:599–612. doi: 10.1038/nrc3343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang L, Rau R, Goodell MA. DNMT3A in haematological malignancies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:152–65. doi: 10.1038/nrc3895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rau R, Brown P. Nucleophosmin (NPM1) mutations in adult and childhood acute myeloid leukaemia: towards definition of a new leukaemia entity. Hematol Oncol. 2009;27:171–181. doi: 10.1002/hon.904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen CC, Gau JP, You JY, Lee KD, Yu YB, Lu CH, Lin JT, Lan C, Lo WH, Liu JM, Yang CF. Prognostic significance of beta-catenin and topoisomerase IIalpha in de novo acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2009;84:87–92. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ysebaert L, Chicanne G, Demur C, De Toni F, Prade-Houdellier N, Ruidavets JB, Mansat-De Mas V, Rigal-Huguet F, Laurent G, Payrastre B, Manenti S, Racaud-Sultan C. Expression of beta-catenin by acute myeloid leukemia cells predicts enhanced clonogenic capacities and poor prognosis. Leukemia. 2006;20:1211–1216. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaidzik VI, Schlenk RF, Paschka P, Stölzle A, Späth D, Kuendgen A, von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Brugger W, Derigs HG, Kremers S, Greil R, Raghavachar A, Ringhoffer M, Salih HR, Wattad M, Kirchen HG, Runde V, Heil G, Petzer AL, Girschikofsky M, Heuser M, Kayser S, Goehring G, Teleanu MV, Schlegelberger B, Ganser A, Krauter J, Bullinger L, Döhner H, Döhner K. Clinical impact of DNMT3A mutations in younger adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia: results of the AML Study Group (AMLSG) Blood. 2013;121:4769–4777. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-10-461624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hollink IH, Feng Q, Danen-van Oorschot AA, Arentsen-Peters ST, Verboon LJ, Zhang P, de Haas V, Reinhardt D, Creutzig U, Trka J, Pieters R, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Wang J, Zwaan CM. Low frequency of DNMT3A mutations in pediatric AML, and the identification of the OCI-AML3 cell line as an in vitro model. Leukemia. 2012;26:371–373. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimm J, Jentzsch M, Bill M, Backhaus D, Brauer D, Küpper J, Schulz J, Franke GN, Vucinic V, Niederwieser D, Platzbecker U, Schwind S. Clinical implications of SRSF2 mutations in AML patients undergoing allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Am J Hematol. 2021;96:1287–1294. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamato G, Shiba N, Yoshida K, Hara Y, Shiraishi Y, Ohki K, Okubo J, Park MJ, Sotomatsu M, Arakawa H, Kiyokawa N, Tomizawa D, Adachi S, Taga T, Horibe K, Miyano S, Ogawa S, Hayashi Y. RUNX1 mutations in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia are associated with distinct genetic features and an inferior prognosis. Blood. 2018;131:2266–2270. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-11-814442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papaemmanuil E, Gerstung M, Bullinger L, Gaidzik VI, Paschka P, Roberts ND, Potter NE, Heuser M, Thol F, Bolli N, Gundem G, Van Loo P, Martincorena I, Ganly P, Mudie L, McLaren S, O’Meara S, Raine K, Jones DR, Teague JW, Butler AP, Greaves MF, Ganser A, Döhner K, Schlenk RF, Döhner H, Campbell PJ. Genomic classification and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2209–2221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stasik S, Eckardt JN, Kramer M, Röllig C, Krämer A, Scholl S, Hochhaus A, Crysandt M, Brümmendorf TH, Naumann R, Steffen B, Kunzmann V, Einsele H, Schaich M, Burchert A, Neubauer A, Schäfer-Eckart K, Schliemann C, Krause S, Herbst R, Hänel M, Frickhofen N, Noppeney R, Kaiser U, Baldus CD, Kaufmann M, Rácil Z, Platzbecker U, Berdel WE, Mayer J, Serve H, Müller-Tidow C, Ehninger G, Bornhäuser M, Schetelig J, Middeke JM, Thiede C Study Alliance Leukemia (SAL) Impact of PTPN11 mutations on clinical outcome analyzed in 1529 patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 2021;5:3279–3289. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liao XY, Fang JP, Zhou DH, Qiu KY. CEBPA are independent good prognostic factors in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. Hematol Oncol. 2022;40:258–268. doi: 10.1002/hon.2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jalnapurkar SS, Pawar A, Somers P, Ochoco G, George SS, Pimkin M, Paralkar VR. PHF6 restricts AML acceleration by promoting myeloid differentiation genes in leukemic cells. Blood. 2020;136:42–43. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hara Y, Taki T, Yamato G, Yoshida K, Shiozawa Y, Shiba N, Kaburagi T, Shiraishi Y, Ohki K, Kawamura M, Sotomatsu M, Arakawa H, Matsuo H, Shimada A, Toki T, Kiyokawa N, Tomizawa D, Taga T, Ito E, Horibe K, Miyano S, Ogawa S, Adachi S, Hayashi Y. Clinical features of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia with TP53 and CDKN2A/2B copy number alterations. Blood. 2019;134:2727. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dutta S, Pregartner G, Rücker FG, Heitzer E, Zebisch A, Bullinger L, Berghold A, Döhner K, Sill H. Functional classification of TP53 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:637. doi: 10.3390/cancers12030637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bamopoulos SA, Batcha AMN, Jurinovic V, Rothenberg-Thurley M, Janke H, Ksienzyk B, Philippou-Massier J, Graf A, Krebs S, Blum H, Schneider S, Konstandin N, Sauerland MC, Görlich D, Berdel WE, Woermann BJ, Bohlander SK, Canzar S, Mansmann U, Hiddemann W, Braess J, Spiekermann K, Metzeler KH, Herold T. Clinical presentation and differential splicing of SRSF2, U2AF1 and SF3B1 mutations in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2020;34:2621–2634. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0839-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Q, Dong S, Yao H, Wen L, Qiu H, Qin L, Ma L, Chen S. ETV6 mutation in a cohort of 970 patients with hematologic malignancies. Haematologica. 2014;99:e176–8. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.104406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith JL, Ries RE, Wang YC, Leonti AR, Alonzo TA, Gamis AS, Aplenc R, Kolb AE, Huang BJ, Ma X, Shaw TI, Meshinchi S. ETS family transcription factor fusions in childhood AML: distinct expression networks and clinical implications. Blood. 2021;138:2356. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Falini B, Brunetti L, Sportoletti P, Martelli MP. NPM1-mutated acute myeloid leukemia: from bench to bedside. Blood. 2020;136:1707–1721. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019004226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mannelli F, Ponziani V, Bencini S, Bonetti MI, Benelli M, Cutini I, Gianfaldoni G, Scappini B, Pancani F, Piccini M, Rondelli T, Caporale R, Gelli AM, Peruzzi B, Chiarini M, Borlenghi E, Spinelli O, Giupponi D, Zanghì P, Bassan R, Rambaldi A, Rossi G, Bosi A. CEBPA-double-mutated acute myeloid leukemia displays a unique phenotypic profile: a reliable screening method and insight into biological features. Haematologica. 2017;102:529–540. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.151910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molica M, Mazzone C, Niscola P, de Fabritiis P. TP53 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: still a daunting challenge? Front Oncol. 2021;10:610820. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.610820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Döhner H, Estey E, Grimwade D, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Büchner T, Dombret H, Ebert BL, Fenaux P, Larson RA, Levine RL, Lo-Coco F, Naoe T, Niederwieser D, Ossenkoppele GJ, Sanz M, Sierra J, Tallman MS, Tien HF, Wei AH, Löwenberg B, Bloomfield CD. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2017 ELN recommendations from an International Expert Panel. Blood. 2017;129:424–447. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-08-733196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haferlach T. Molecular genetic pathways as therapeutic targets in acute myeloid leukemia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2008:400–411. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2008.1.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ibáñez M, Carbonell-Caballero J, Such E, García-Alonso L, Liquori A, López-Pavía M, Llop M, Alonso C, Barragán E, Gómez-Seguí I, Neef A, Hervás D, Montesinos P, Sanz G, Sanz MA, Dopazo J, Cervera J. The modular network structure of the mutational landscape of acute myeloid leukemia. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0202926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duployez N, Marceau-Renaut A, Boissel N, Petit A, Bucci M, Geffroy S, Lapillonne H, Renneville A, Ragu C, Figeac M, Celli-Lebras K, Lacombe C, Micol JB, Abdel-Wahab O, Cornillet P, Ifrah N, Dombret H, Leverger G, Jourdan E, Preudhomme C. Comprehensive mutational profiling of core binding factor acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2016;127:2451–2459. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-12-688705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kantarjian H, Kadia T, DiNardo C, Daver N, Borthakur G, Jabbour E, Garcia-Manero G, Konopleva M, Ravandi F. Acute myeloid leukemia: current progress and future directions. Blood Cancer J. 2021;11:41. doi: 10.1038/s41408-021-00425-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamamyan G, Kadia T, Ravandi F, Borthakur G, Cortes J, Jabbour E, Daver N, Ohanian M, Kantarjian H, Konopleva M. Frontline treatment of acute myeloid leukemia in adults. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;110:20–34. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Versluis J, Cornelissen JJ, Craddock C, Sanz MÁ, Canaani J, Nagler A. Acute myeloid leukemia in adults. In: Carreras E, Dufour C, Mohty M, Kröger N, editors. The EBMT Handbook: Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation and Cellular Therapies. 7th ed. Cham (CH): Springer; 2019. Chapter 69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molica M, Breccia M, Foa R, Jabbour E, Kadia TM. Maintenance therapy in AML: the past, the present and the future. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:1254–1265. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lai C, Doucette K, Norsworthy K. Recent drug approvals for acute myeloid leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:100. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0774-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weissmann S, Alpermann T, Grossmann V, Kowarsch A, Nadarajah N, Eder C, Dicker F, Fasan A, Haferlach C, Haferlach T, Kern W, Schnittger S, Kohlmann A. Landscape of TET2 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2012;26:934–42. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohgami RS, Ma L, Merker JD, Gotlib JR, Schrijver I, Zehnder JL, Arber DA. Next-generation sequencing of acute myeloid leukemia identifies the significance of TP53, U2AF1, ASXL1, and TET2 mutations. Mod Pathol. 2015;28:706–714. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Metzeler KH, Maharry K, Radmacher MD, Mrózek K, Margeson D, Becker H, Curfman J, Holland KB, Schwind S, Whitman SP, Wu YZ, Blum W, Powell BL, Carter TH, Wetzler M, Moore JO, Kolitz JE, Baer MR, Carroll AJ, Larson RA, Caligiuri MA, Marcucci G, Bloomfield CD. TET2 mutations improve the new European LeukemiaNet risk classification of acute myeloid leukemia: a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:1373–1381. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.7742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Figueroa ME, Abdel-Wahab O, Lu C, Ward PS, Patel J, Shih A, Li Y, Bhagwat N, Vasanthakumar A, Fernandez HF, Tallman MS, Sun Z, Wolniak K, Peeters JK, Liu W, Choe SE, Fantin VR, Paietta E, Löwenberg B, Licht JD, Godley LA, Delwel R, Valk PJ, Thompson CB, Levine RL, Melnick A. Leukemic IDH1 and IDH2 mutations result in a hypermethylation phenotype, disrupt TET2 function, and impair hematopoietic differentiation. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:553–567. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dang L, White DW, Gross S, Bennett BD, Bittinger MA, Driggers EM, Fantin VR, Jang HG, Jin S, Keenan MC, Marks KM, Prins RM, Ward PS, Yen KE, Liau LM, Rabinowitz JD, Cantley LC, Thompson CB, Vander Heiden MG, Su SM. Cancer-associated IDH1 mutations produce 2-hydroxyglutarate. Nature. 2009;462:739–744. doi: 10.1038/nature08617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu W, Yang H, Liu Y, Yang Y, Wang P, Kim SH, Ito S, Yang C, Wang P, Xiao MT, Liu LX, Jiang WQ, Liu J, Zhang JY, Wang B, Frye S, Zhang Y, Xu YH, Lei QY, Guan KL, Zhao SM, Xiong Y. Oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:17–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rasmussen KD, Jia G, Johansen JV, Pedersen MT, Rapin N, Bagger FO, Porse BT, Bernard OA, Christensen J, Helin K. Loss of TET2 in hematopoietic cells leads to DNA hypermethylation of active enhancers and induction of leukemogenesis. Genes Dev. 2015;29:910–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.260174.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hock H, Shimamura A. ETV6 in hematopoiesis and leukemia predisposition. Semin Hematol. 2017;54:98–104. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bąk A, Skonieczka K, Jaśkowiec A, Junkiert-Czarnecka A, Heise M, Pilarska-Deltow M, Potoczek S, Czyżewska M, Haus O. Germline mutations among Polish patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2021;19:42. doi: 10.1186/s13053-021-00200-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou F, Chen B. Acute myeloid leukemia carrying ETV6 mutations: biologic and clinical features. Hematology. 2018;23:608–612. doi: 10.1080/10245332.2018.1482051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn-Khosrovani S, Spensberger D, de Knegt Y, Tang M, Löwenberg B, Delwel R. Somatic heterozygous mutations in ETV6 (TEL) and frequent absence of ETV6 protein in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncogene. 2005;24:4129–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Rooij J, Beuling E, Fornerod M, Obulkasim A, Baruchel A, Trka J, Reinhardt D, Sonneveld E, Zimmermann M, Pieters R, van den Heuvel-Eibrink M, Zwaan CM. ETV6 aberrations are a recurrent event in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia with poor clinical outcome. Blood. 2014;124:1012. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siapati EK, Papadaki M, Kozaou Z, Rouka E, Michali E, Savvidou I, Gogos D, Kyriakou D, Anagnostopoulos NI, Vassilopoulos G. Proliferation and bone marrow engraftment of AML blasts is dependent on β-catenin signalling. Br J Haematol. 2011;152:164–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu HT, Chen WT, Li GW, Shen JX, Ye QQ, Zhang ML, Chen WJ, Liu J. Analysis of the differentially expressed genes induced by cisplatin resistance in oral squamous cell carcinomas and their interaction. Front Genet. 2020;10:1328. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.01328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Slovak ML, Kopecky KJ, Cassileth PA, Harrington DH, Theil KS, Mohamed A, Paietta E, Willman CL, Head DR, Rowe JM, Forman SJ, Appelbaum FR. Karyotypic analysis predicts outcome of preremission and postremission therapy in adult acute myeloid leukemia: a Southwest Oncology Group/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study. Blood. 2000;96:4075–4083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Byrd JC, Mrózek K, Dodge RK, Carroll AJ, Edwards CG, Arthur DC, Pettenati MJ, Patil SR, Rao KW, Watson MS, Koduru PR, Moore JO, Stone RM, Mayer RJ, Feldman EJ, Davey FR, Schiffer CA, Larson RA, Bloomfield CD Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8461) Pretreatment cytogenetic abnormalities are predictive of induction success, cumulative incidence of relapse, and overall survival in adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8461) Blood. 2002;100:4325–4336. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li XX, Guo H, Zhou JD, Wu DH, Ma JC, Wen XM, Zhang W, Xu ZJ, Lin J, Jun Q. Overexpression of CTNNB1: clinical implication in Chinese de novo acute myeloid leukemia. Pathol Res Pract. 2018;214:361–367. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kirstetter P, Anderson K, Porse BT, Jacobsen SE, Nerlov C. Activation of the canonical Wnt pathway leads to loss of hematopoietic stem cell repopulation and multilineage differentiation block. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1048–1056. doi: 10.1038/ni1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chung EJ, Hwang SG, Nguyen P, Lee S, Kim JS, Kim JW, Henkart PA, Bottaro DP, Soon L, Bonvini P, Lee SJ, Karp JE, Oh HJ, Rubin JS, Trepel JB. Regulation of leukemic cell adhesion, proliferation, and survival by beta-catenin. Blood. 2002;100:982–990. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.3.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Luo XD, Yang SJ, Wang JN, Tan L, Liu D, Wang YY, Zheng RH, Wu XH, Xu LH, Tan H. Downregulation of SATB1 increases the invasiveness of Jurkat cell via activation of the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway in vitro. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:7413–7419. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4638-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bachas C, Schuurhuis GJ, Zwaan CM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, den Boer ML, de Bont ES, Kwidama ZJ, Reinhardt D, Creutzig U, de Haas V, Kaspers GJ, Cloos J. Gene expression profiles associated with pediatric relapsed AML. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0121730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhai S, Xue J, Wang Z, Hu L. High expression of special AT-rich sequence binding protein-1 predicts esophageal squamous cell carcinoma relapse and poor prognosis. Oncol Lett. 2017;14:7455–7460. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.7081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pandey R, Saxena M, Kapur R. Role of SHP2 in hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2017;24:307–313. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tonks NK. Protein tyrosine phosphatases: from genes, to function, to disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:833–46. doi: 10.1038/nrm2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chan RJ, Leedy MB, Munugalavadla V, Voorhorst CS, Li Y, Yu M, Kapur R. Human somatic PTPN11 mutations induce hematopoietic-cell hypersensitivity to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 2005;105:3737–3742. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schubbert S, Lieuw K, Rowe SL, Lee CM, Li X, Loh ML, Clapp DW, Shannon KM. Functional analysis of leukemia-associated PTPN11 mutations in primary hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2005;106:311–317. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mohi MG, Williams IR, Dearolf CR, Chan G, Kutok JL, Cohen S, Morgan K, Boulton C, Shigematsu H, Keilhack H, Akashi K, Gilliland DG, Neel BG. Prognostic, therapeutic, and mechanistic implications of a mouse model of leukemia evoked by Shp2 (PTPN11) mutations. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:179–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gupta AK, Meena JP, Chopra A, Tanwar P, Seth R. Juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia-A comprehensive review and recent advances in management. Am J Blood Res. 2021;11:1–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tartaglia M, Martinelli S, Iavarone I, Cazzaniga G, Spinelli M, Giarin E, Petrangeli V, Carta C, Masetti R, Aricò M, Locatelli F, Basso G, Sorcini M, Pession A, Biondi A. Somatic PTPN11 mutations in childhood acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:333–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alfayez M, Issa GC, Patel KP, Wang F, Wang X, Short NJ, Cortes JE, Kadia T, Ravandi F, Pierce S, Assi R, Garcia-Manero G, DiNardo CD, Daver N, Pemmaraju N, Kantarjian H, Borthakur G. The clinical impact of PTPN11 mutations in adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2021;35:691–700. doi: 10.1038/s41375-020-0920-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yoshida K, Sanada M, Shiraishi Y, Nowak D, Nagata Y, Yamamoto R, Sato Y, Sato-Otsubo A, Kon A, Nagasaki M, Chalkidis G, Suzuki Y, Shiosaka M, Kawahata R, Yamaguchi T, Otsu M, Obara N, Sakata-Yanagimoto M, Ishiyama K, Mori H, Nolte F, Hofmann WK, Miyawaki S, Sugano S, Haferlach C, Koeffler HP, Shih LY, Haferlach T, Chiba S, Nakauchi H, Miyano S, Ogawa S. Frequent pathway mutations of splicing machinery in myelodysplasia. Nature. 2011;478:64–69. doi: 10.1038/nature10496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Palangat M, Anastasakis DG, Fei DL, Lindblad KE, Bradley R, Hourigan CS, Hafner M, Larson DR. The splicing factor U2AF1 contributes to cancer progression through a noncanonical role in translation regulation. Genes Dev. 2019;33:482–497. doi: 10.1101/gad.319590.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Qian J, Yao DM, Lin J, Qian W, Wang CZ, Chai HY, Yang J, Li Y, Deng ZQ, Ma JC, Chen XX. U2AF1 mutations in Chinese patients with acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45760. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pellagatti A, Boultwood J. Splicing factor mutant myelodysplastic syndromes: recent advances. Adv Biol Regul. 2020;75:100655. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2019.100655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Maurya N, Mohanty P, Dhangar S, Panchal P, Jijina F, Mathan SLP, Shanmukhaiah C, Madkaikar M, Vundinti BR. Comprehensive analysis of genetic factors predicting overall survival in Myelodysplastic syndromes. Sci Rep. 2022;12:5925. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-09864-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu M, Wang F, Zhang Y, Chen X, Cao P, Nie D, Fang J, Wang M, Liu M, Liu H. Gene mutation spectrum of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and progression to acute myeloid leukemia. Int J Hematol Oncol. 2021;10:IJH34. doi: 10.2217/ijh-2021-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Choi HW, Kim HR, Baek HJ, Kook H, Cho D, Shin JH, Suh SP, Ryang DW, Shin MG. Alteration of the SETBP1 gene and splicing pathway genes SF3B1, U2AF1, and SRSF2 in childhood acute myeloid leukemia. Ann Lab Med. 2015;35:118–22. doi: 10.3343/alm.2015.35.1.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Venkatasubramanian M, Chen X, Chetal K, Kulkarni A, Myers KC, Weirauch MT, Grimes HL, Salomonis N. A prognostic human splicing signature that precurses leukemia. Blood. 2018;132:877. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Skoda RC, Schwaller J. Dual roles of EZH2 in acute myeloid leukemia. J Exp Med. 2019;216:725–727. doi: 10.1084/jem.20190250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tanaka S, Miyagi S, Sashida G, Chiba T, Yuan J, Mochizuki-Kashio M, Suzuki Y, Sugano S, Nakaseko C, Yokote K, Koseki H, Iwama A. Ezh2 augments leukemogenicity by reinforcing differentiation blockage in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2012;120:1107–1117. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-394932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang X, Dai H, Wang Q, Wang Q, Xu Y, Wang Y, Sun A, Ruan J, Chen S, Wu D. EZH2 mutations are related to low blast percentage in bone marrow and -7/del(7q) in de novo acute myeloid leukemia. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Göllner S, Oellerich T, Agrawal-Singh S, Schenk T, Klein HU, Rohde C, Pabst C, Sauer T, Lerdrup M, Tavor S, Stölzel F, Herold S, Ehninger G, Köhler G, Pan KT, Urlaub H, Serve H, Dugas M, Spiekermann K, Vick B, Jeremias I, Berdel WE, Hansen K, Zelent A, Wickenhauser C, Müller LP, Thiede C, Müller-Tidow C. Loss of the histone methyltransferase EZH2 induces resistance to multiple drugs in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Med. 2017;23:69–78. doi: 10.1038/nm.4247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kempf JM, Weser S, Bartoschek MD, Metzeler KH, Vick B, Herold T, Völse K, Mattes R, Scholz M, Wange LE, Festini M, Ugur E, Roas M, Weigert O, Bultmann S, Leonhardt H, Schotta G, Hiddemann W, Jeremias I, Spiekermann K. Loss-of-function mutations in the histone methyltransferase EZH2 promote chemotherapy resistance in AML. Sci Rep. 2021;11:5838. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84708-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ernst T, Chase AJ, Score J, Hidalgo-Curtis CE, Bryant C, Jones AV, Waghorn K, Zoi K, Ross FM, Reiter A, Hochhaus A, Drexler HG, Duncombe A, Cervantes F, Oscier D, Boultwood J, Grand FH, Cross NC. Inactivating mutations of the histone methyltransferase gene EZH2 in myeloid disorders. Nat Genet. 2010;42:722–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sauvageau M, Sauvageau G. Polycomb group proteins: multi-faceted regulators of somatic stem cells and cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;7:299–313. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stomper J, Meier R, Ma T, Pfeifer D, Ihorst G, Blagitko-Dorfs N, Greve G, Zimmer D, Platzbecker U, Hagemeijer A, Schmitt-Graeff I, Lübbert M. Integrative study of EZH2 mutational status, copy number, protein expression and H3K27 trimethylation in AML/MDS patients. Clin Epigenetics. 2021;13:77. doi: 10.1186/s13148-021-01052-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mechaal A, Menif S, Abbes S, Safra I. EZH2, new diagnosis and prognosis marker in acute myeloid leukemia patients. Adv Med Sci. 2019;64:395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.advms.2019.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stasik S, Middeke JM, Kramer M, Röllig C, Krämer A, Scholl S, Hochhaus A, Crysandt M, Brümmendorf TH, Naumann R, Steffen B, Kunzmann V, Einsele H, Schaich M, Burchert A, Neubauer A, Schäfer-Eckart K, Schliemann C, Krause S, Herbst R, Hänel M, Frickhofen N, Noppeney R, Kaiser U, Baldus CD, Kaufmann M, Rácil Z, Platzbecker U, Berdel WE, Mayer J, Serve H, Müller-Tidow C, Ehninger G, Bornhäuser M, Schetelig J, Thiede C Study Alliance Leukemia (SAL) EZH2 mutations and impact on clinical outcome: an analysis in 1,604 patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica. 2020;105:e228–e231. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.222323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Khan SN, Jankowska AM, Mahfouz R, Dunbar AJ, Sugimoto Y, Hosono N, Hu Z, Cheriyath V, Vatolin S, Przychodzen B, Reu FJ, Saunthararajah Y, O’Keefe C, Sekeres MA, List AF, Moliterno AR, McDevitt MA, Maciejewski JP, Makishima H. Multiple mechanisms deregulate EZH2 and histone H3 lysine 27 epigenetic changes in myeloid malignancies. Leukemia. 2013;27:1301–1309. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sashida G, Harada H, Matsui H, Oshima M, Yui M, Harada Y, Tanaka S, Mochizuki-Kashio M, Wang C, Saraya A, Muto T, Hayashi Y, Suzuki K, Nakajima H, Inaba T, Koseki H, Huang G, Kitamura T, Iwama A. Ezh2 loss promotes development of myelodysplastic syndrome but attenuates its predisposition to leukaemic transformation. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4177. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Voss AK, Gamble R, Collin C, Shoubridge C, Corbett M, Gécz J, Thomas T. Protein and gene expression analysis of Phf6, the gene mutated in the Börjeson-Forssman-Lehmann Syndrome of intellectual disability and obesity. Gene Expr Patterns. 2007;7:858–871. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Eisa YA, Guo Y, Yang FC. The role of PHF6 in hematopoiesis and hematologic malignancies. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2023;19:67–75. doi: 10.1007/s12015-022-10447-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Patel JP, Gönen M, Figueroa ME, Fernandez H, Sun Z, Racevskis J, Van Vlierberghe P, Dolgalev I, Thomas S, Aminova O, Huberman K, Cheng J, Viale A, Socci ND, Heguy A, Cherry A, Vance G, Higgins RR, Ketterling RP, Gallagher RE, Litzow M, van den Brink MR, Lazarus HM, Rowe JM, Luger S, Ferrando A, Paietta E, Tallman MS, Melnick A, Abdel-Wahab O, Levine RL. Prognostic relevance of integrated genetic profiling in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1079–1089. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mori T, Nagata Y, Makishima H, Sanada M, Shiozawa Y, Kon A, Yoshizato T, Sato-Otsubo A, Kataoka K, Shiraishi Y, Chiba K, Tanaka H, Ishiyama K, Miyawaki S, Mori H, Nakamaki T, Kihara R, Kiyoi H, Koeffler HP, Shih LY, Miyano S, Naoe T, Haferlach C, Kern W, Haferlach T, Ogawa S, Yoshida K. Somatic PHF6 mutations in 1760 cases with various myeloid neoplasms. Leukemia. 2016;30:2270–2273. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Van Vlierberghe P, Patel J, Abdel-Wahab O, Lobry C, Hedvat CV, Balbin M, Nicolas C, Payer AR, Fernandez HF, Tallman MS, Paietta E, Melnick A, Vandenberghe P, Speleman F, Aifantis I, Cools J, Levine R, Ferrando A. PHF6 mutations in adult acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:130–134. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang R, Gao X, Yu L. The prognostic impact of TET oncogene family member 2 mutations in patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a systematic-review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:389. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5602-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Langemeijer SM, Jansen JH, Hooijer J, van Hoogen P, Stevens-Linders E, Massop M, Waanders E, van Reijmersdal SV, Stevens-Kroef MJ, Zwaan CM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, Sonneveld E, Hoogerbrugge PM, van Kessel AG, Kuiper RP. TET2 mutations in childhood leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:189–92. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kaburagi T, Yamato G, Shiba N, Yoshida K, Hara Y, Shiraishi Y, Ohki K, Sotomatsu M, Arakawa H, Matsuo H, Shimada A, Taki T, Kiyokawa N, Tomizawa D, Horibe K, Miyano S, Taga T, Adachi S, Ogawa S, Hayashi Y. Recurrent gene mutations in pediatric patients with AML by targeted sequencing - the Jccg Study, JPLSG AML-05. Blood. 2019;134:2697. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Haferlach C, Bacher U, Schnittger S, Alpermann T, Zenger M, Kern W, Haferlach T. ETV6 rearrangements are recurrent in myeloid malignancies and are frequently associated with other genetic events. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;51:328–37. doi: 10.1002/gcc.21918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Loh ML, Reynolds MG, Vattikuti S, Gerbing RB, Alonzo TA, Carlson E, Cheng JW, Lee CM, Lange BJ, Meshinchi S Children’s Cancer Group. PTPN11 mutations in pediatric patients with acute myeloid leukemia: results from the Children’s Cancer Group. Leukemia. 2004;18:1831–1834. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Li B, Zou D, Yang S, Ouyang G, Mu Q. Prognostic significance of U2AF1 mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes: a meta-analysis. J Int Med Res. 2020;48:300060519891013. doi: 10.1177/0300060519891013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Ley TJ, Miller C, Ding L, Raphael BJ, Mungall AJ, Robertson A, Hoadley K, Triche TJ Jr, Laird PW, Baty JD, Fulton LL, Fulton R, Heath SE, Kalicki-Veizer J, Kandoth C, Klco JM, Koboldt DC, Kanchi KL, Kulkarni S, Lamprecht TL, Larson DE, Lin L, Lu C, McLellan MD, McMichael JF, Payton J, Schmidt H, Spencer DH, Tomasson MH, Wallis JW, Wartman LD, Watson MA, Welch J, Wendl MC, Ally A, Balasundaram M, Birol I, Butterfield Y, Chiu R, Chu A, Chuah E, Chun HJ, Corbett R, Dhalla N, Guin R, He A, Hirst C, Hirst M, Holt RA, Jones S, Karsan A, Lee D, Li HI, Marra MA, Mayo M, Moore RA, Mungall K, Parker J, Pleasance E, Plettner P, Schein J, Stoll D, Swanson L, Tam A, Thiessen N, Varhol R, Wye N, Zhao Y, Gabriel S, Getz G, Sougnez C, Zou L, Leiserson MD, Vandin F, Wu HT, Applebaum F, Baylin SB, Akbani R, Broom BM, Chen K, Motter TC, Nguyen K, Weinstein JN, Zhang N, Ferguson ML, Adams C, Black A, Bowen J, Gastier-Foster J, Grossman T, Lichtenberg T, Wise L, Davidsen T, Demchok JA, Shaw KR, Sheth M, Sofia HJ, Yang L, Downing JR, Eley G. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2059–2074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lee SC, Dvinge H, Kim E, Cho H, Micol JB, Chung YR, Durham BH, Yoshimi A, Kim YJ, Thomas M, Lobry C, Chen CW, Pastore A, Taylor J, Wang X, Krivtsov A, Armstrong SA, Palacino J, Buonamici S, Smith PG, Bradley RK, Abdel-Wahab O. Modulation of splicing catalysis for therapeutic targeting of leukemia with mutations in genes encoding spliceosomal proteins. Nat Med. 2016;22:672–678. doi: 10.1038/nm.4097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Terao T, Minami Y. Targeting hedgehog (Hh) pathway for the acute myeloid leukemia treatment. Cells. 2019;8:312. doi: 10.3390/cells8040312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jiang X, Mak PY, Mu H, Tao W, Mak DH, Kornblau S, Zhang Q, Ruvolo P, Burks JK, Zhang W, McQueen T, Pan R, Zhou H, Konopleva M, Cortes J, Liu Q, Andreeff M, Carter BZ. Disruption of Wnt/β-catenin exerts antileukemia activity and synergizes with FLT3 inhibition in FLT3-mutant acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:2417–2429. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]