Abstract

Introduction

For Streptococcus pneumoniae, β-lactam susceptibility can be predicted from the amino acid sequence of the penicillin-binding proteins PBP1a, PBP2b, and PBP2x. The combination of PBP-subtypes provides a PBP-profile, which correlates to a phenotypic minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC). The non-S. pneumoniae Mitis-group streptococci (MGS) have similar PBPs and exchange pbp-alleles with S. pneumoniae. We studied whether a simple BLAST analysis could be used to predict phenotypic susceptibility in Danish S. pneumoniae isolates and in internationally collected MGS.

Method

Isolates with available WGS and phenotypic susceptibility data were included. For each isolate, the best matching PBP-profile was identified by BLAST analysis. The corresponding MICs for penicillin and ceftriaxone was retrieved. Category agreement (CA), minor-, major-, and very major discrepancy was calculated. Genotypic-phenotypic accuracy was examined with Deming regression.

Results

Among 88 S. pneumoniae isolates, 55 isolates had a recognized PBP-profile, and CA was 100% for penicillin and 98.2% for ceftriaxone. In 33 S. pneumoniae isolates with a new PBP-profile, CA was 90.9% (penicillin) and 93.8% (ceftriaxone) using the nearest recognized PBP-profile. Applying the S. pneumoniae database to non-S. pneumoniae MGS revealed that none had a recognized PBP-profile. For Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae, CA was 100% for penicillin and ceftriaxone in 19 susceptible isolates. In 33 Streptococcus mitis isolates, CA was 75.8% (penicillin) and 86.2% (ceftriaxone) and in 25 Streptococcus oralis isolates CA was 8% (penicillin) and 100% (ceftriaxone).

Conclusion

Using a simple BLAST analysis, genotypic susceptibility prediction was accurate in Danish S. pneumoniae isolates, particularly in isolates with recognized PBP-profiles. Susceptibility was poorly predicted in other MGS using the current database.

Keywords: penicillin-binding proteins, penicillin, genotypic susceptibility, pneumococcus, Streptococcus

1. Introduction

With increased use of whole genome sequencing (WGS) in clinical microbiological laboratories comes the need for developing robust methods for the prediction of antimicrobial susceptibility from WGS data and for generating data for phenotypic-genotypic correlation of susceptibility (Ellington et al., 2017). Genotypic susceptibility prediction from WGS data is of value in culture-negative specimens, e.g., due to prior antibiotic treatment. Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major pathogen which in 2019 caused 639 cases of invasive infections in Denmark, primarily bloodstream infections (BSI) and meningitis (DANMAP, 2019). The 30-day mortality for S. pneumoniae BSIs has been estimated to 16% (Christensen et al., 2012). Of other bacterial species among the Mitis group streptococci (MGS), Streptococcus mitis and Streptococcus oralis are mainly commensals, but have significant clinical importance, e.g., in infective endocarditis (Rasmussen et al., 2016). Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae is mainly associated with lower respiratory tract infections (Arbique et al., 2004) and hepatic/bile-duct infections (Fuursted et al., 2016).

Most invasive Danish S. pneumoniae are susceptible toward benzylpenicillin, 95.1% in 2019 (DANMAP, 2019), and this is the recommended treatment for susceptible strains. Benzylpenicillin is also the recommended treatment for MGS endocarditis (Habib et al., 2009). Penicillin binds to the transpeptidase domain (TPD) of the penicillin-binding-protein (PBP) and inhibits cell-wall synthesis (Hakenbeck et al., 2012). Penicillin non-susceptible strains have mutations in the pbp2x and pbp2b alleles, that are associated with low-level resistance, and alterations in the pbp1a allele is associated with high-level resistance (Smith and Klugman, 1998). While susceptible S. pneumoniae have conserved pbp-alleles, alleles of non-susceptible strains have a mosaic structure due to horizontal gene transfer by homologous recombination with alleles from non-susceptible MGS. Both susceptible and non-susceptible isolates of S. mitis, S. oralis and S. infantis have a considerable number of polymorphic sites in all three pbp-genes, which is an important reservoir for pneumococcal resistance genes (Jensen et al., 2015). In S. pseudopneumoniae, penicillin-susceptible isolates contain pbp2x alleles distinct from S. pneumoniae and S. mitis, while penicillin-resistant isolates display similar mosaic structures (Van Der Linden et al., 2017).

A method for genotypic prediction of β-lactam susceptibility in S. pneumoniae was first developed by Metcalf et al. (2016b). From a collection of invasive S. pneumoniae isolates, the amino acid sequences of the TPD of the three PBPs, PBP1a, PBP2b and PBP2x, were characterized, and subsequently 69, 77 and 127 unique initial subtypes were identified. A “PBP-profile” could be assigned as a combination of the three PBP-TPD-subtypes, and each PBP-profile correlated to phenotypic MIC values for penicillin and other β-lactam antibiotics. The method was further validated by Metcalf et al. (2016a) and refined by Li et al. (2016) to include newly encountered PBP profiles. Using statistical predictive models, susceptibility could accurately be predicted in 94–99% of cases (Li et al., 2016). This method was also used in isolates with previously uncharacterized PBP-profiles, and showed an overall essential agreement of >97% and a category agreement >93% (Li et al., 2017).

In the present study, we examined an alternative method for genomic susceptibility prediction, which require only basic bioinformatic skills. We used a simple BLAST analysis to identify the nearest PBP-profile of an isolate and used the correlated phenotypic MIC for susceptibility prediction.

We examined the performance of this method in a collection of Danish S. pneumoniae isolates, both with recognized or new PBP-profiles. Since non-S. pneumoniae MGS have similar PBPs and exchange alleles with S. pneumoniae, we were curious whether the same method could be applied to these species and how well susceptibility could be predicted.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Strains

We included 88 clinical S. pneumoniae isolates, 19 S. pseudopneumoniae isolates, 33 S. mitis isolates, 25 S. oralis isolates and 1 S. infantis isolate based on available WGS data and phenotypic susceptibility (MIC) for penicillin and for most isolates ceftriaxone (CFT). Isolates were retrieved from Danish and international collections of MGS (Supplementary Table S1): (1) Danish laboratory surveillance system at the Danish national Neisseria and Streptococcus Reference Laboratory (NSR), Statens Serum Institut, Denmark (SSI) (Kavalari et al., 2019), (2) Department of Biomedicine, Faculty of Health, Aarhus University, Denmark (Aarhus) (Jensen et al., 2015, 2016), (3) The Regional Department of Clinical Microbiology, Region Zealand, Slagelse Hospital, Denmark (Slagelse) (Rasmussen et al., 2016), (4) Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Center, Halifax, Canada via the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, United States (CDC) (Arbique et al., 2004), and (5) the One Day in Denmark (ODiD) project, National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark, Denmark (Rebelo et al., 2022).

2.2. WGS, species identification, multi locus sequence typing (MLST) and molecular serotyping

Isolates from SSI and the 10 S. pseudopneumoniae isolates from CDC were sequenced by paired-end Illumina sequencing (Illumina MiSeq) as previously described (Kavalari et al., 2019). For some isolates from Slagelse and all isolates from Aarhus, WGS data were retrieved from GenBank.1 The remaining isolates from Slagelse were sequenced using Illumina HiSeq 2000 as previously described (4). Isolates from the ODiD-project were sequenced using the Illumina NextSeq 500 platform and pair-end sequencing and The Center for Genomic Epidemiology pipeline (Rebelo et al., 2022). Species identification was confirmed by cgMLSA from WGS data (Jensen et al., 2021). Software Pathogenwatch (Wellcome Sanger Institute)2 was used for MLST and molecular serotyping of S. pneumoniae isolates. For MLST, the seven housekeeping genes aroE, gdh, gki, recP, spi, xpt and ddl were used, retrieved from the PubMLST website https://pubmlst.org/spneumoniae/ (Jolley et al., 2018). The method used for serotyping is based on SeroBA (Epping et al., 2018).

2.3. Phenotypic susceptibility testing

For the isolates from Slagelse/CDC, the ODiD-project and from SSI from year 2010, the MIC for penicillin and ceftriaxone was determined using Sensititre broth microdilution method (Streptococcus species MIC Plate, STP6F, Trek Diagnostic System, United Kingdom) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Before year 2010, the isolates from SSI was tested with Etest (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) on Danish Blood Agar (Resistance plates, SSI Diagnostica) incubated at 36° C, 5% CO2 (DANMAP, 2009). Isolates from Aarhus, were tested with agar dilution method (Jensen et al., 2015). EUCAST breakpoints table version 103 was used for interpretation of SIR susceptibility.

2.4. Prediction of genotypic β-lactam susceptibility

Genotypic prediction of β-lactam susceptibility was performed using the classification system described by Li et al. (2016). From the CDC Streptococcus laboratory website,4 we obtained the amino acid sequences for the TPD subtypes of PBP1a, PBP2b and PBP2x in S. pneumoniae which at the time of data analysis was 101, 121, and 203 subtypes of PBP1a, PBP2b and PBP2x (June 2017). Using WGS data from our isolates, a nucleotide-protein BLAST analysis was performed using the NCBI Genome Workbench, version 3.0.0.5 to identify the nearest PBP1a, PBP2b and PBP2x subtypes. In the case of 100% identity for all three PBPs, a “PBP-profile” (PBP-type) was assigned, and the corresponding phenotypic MIC values for penicillin and ceftriaxone was retrieved from the available “PBP-type-To-MIC table,” accessed in June 2017. This contains 422 PBP-profiles for penicillin and 317 PBP-profiles for ceftriaxone. Although the number of PBP subtypes has increased significantly since (477 subtypes of PBP1a, 658 subtypes of PBP2b and 1050 subtypes of PBP2x by September 2022), the correlation of a whole PBP-type to a phenotypic susceptibility has not been updated since.

Isolates without a recognized PBP-profile included isolates where the exact combination of the three PBP-TPBs was not in the PBP-to-MIC table. Other isolates, particularly non-S. pneumoniae MGS, had substitutions in one or more PBP-TPDs. For MIC-prediction in these isolates, we created a database containing the concatenated PBP-TPD sequence for all published PBP-profiles with a correlating MIC. This database was used for a BLAST analysis with the concatenated PBP-TPD sequence for a given isolate. The best matching PBP-profile was identified as the result with the highest percent identity together with the highest total BLAST score.

Using this method, isolates could have a PBP-profile as best match with more substitutions than the sum of substitutions in each PBP separately. The applied method was chosen, because it requires only basic bioinformatic skills, a simple database containing the PBP-TPD amino acid sequences and the correlating phenotypic MIC and is fast to run.

2.5. Phylogenetic analysis of the concatenated PBP TPD sequence

A phylogenetic analysis of the concatenated PBP amino acid sequence from each isolate was performed using IQ-TREE (Nguyen et al., 2015) with a Blosum62 scoring matrix for amino-acid substitutions. The model only allowed amino acid sequences of equal length. All, except three S. mitis isolates, had a concatenated sequence of 914 amino acids. Isolates Sm7 and Sm19 had one insertion (position 326) and Sm32 three insertions (position 326–328), which were omitted for the phylogenetic analyses after ensuring that the PBP-profile was the same before and after the modification. We included the concatenated PBP amino acid sequence of the species type strains: S. pneumoniae NCTC 7465T (NCBI reference NZ_LN831051.1), S. pseudopneumoniae ATCC-BAA-960T (NZ_AICS00000000.1), S. mitis NCTC 12261T (NZ_CP028414.1), S. oralis ATCC 35037T (NZ_LR134336.1) and S. infantis ATCC 700779T (NZ_GL732439.1). An outlier reference sequence was included: the concatenated PBP-sequence of Streptococcus dysgalactiae subspecies equisimilis AC2713 (NC_019042.1) was modified to a length of 914 amino acids by using an alignment with S. pneumoniae R6 to omit insertions at positions 525, 526, 532, 533, 650, 692, 897, and deletions at positions 327, 328, 867 were replaced by the corresponding amino acid in R6. The software iTOL version 5.6.26 was used for visualization of trees.

2.6. Statistical analyses

We reported the number of isolates phenotypic and genotypic susceptible (S), susceptible-increased-exposure (I) and resistant (R) toward penicillin and ceftriaxone. Category agreement (CA) was defined as correctly predicted S-I-R, minor discrepancy (MiD) was susceptible isolates predicted to be susceptible-increased-exposure, susceptible-increased-exposure isolates predicted to be resistant and opposite. Major discrepancy (MaD) was isolates being resistant by genotype but susceptible by phenotype, while very major discrepancy (VMaD) was isolates being susceptible by genotype but resistant by phenotype. Essential agreement (EA) was an equal genotypic/ phenotypic MIC +/− one two-fold dilution. For isolates with an MIC ≤0.03, the value 0.03 was used.

For S. pneumoniae positive and negative predictive values (PPV, NPV) for non-susceptibility were calculated. Deming regression models were used to visualize log2 transformed phenotypic-genotypic MIC, using statistical software RStudio version 1.1.453. Isolates with an MIC ≤0.03, was given the value 0.03 and MIC >2 the value 4.

2.7. Ethical considerations

The data used did not include any personalized data.

3. Results

We included 88 isolates of S. pneumoniae, of which 62 were from BSI or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and the remaining isolates were mainly from respiratory specimens. S. pneumoniae isolates were collected in Denmark between 1999 and 2018 except one historic isolate (1943), and included 23 different serotypes and 34 different MLSTs. The 19 S. pseudopneumoniae isolates included 13 respiratory isolates, of which most originated from Canada (5). Among the 33 S. mitis isolates, 14 were from BSI and the remaining were mainly respiratory isolates and among the 25 S. oralis isolates, 21 were BSI, mainly endocarditis isolates. The S. infantis isolate was isolated from a urogenital infection (Supplementary Table S1). All species were identified using cgMLSA (Supplementary Figure S1).

3.1. PBP-types in Danish Streptococcus pneumoniae and MGS

In 55 of 88 S. pneumoniae isolates (62.5%), PBP1a, PBP2b and PBP2x all exactly matched a subtype in the database, and a recognized PBP-profile and a corresponding MIC could be predicted. Among isolates from the ODiD-project, 11 of 16 isolates (68.8%) had a recognized PBP-profile.

In the remaining 33 S. pneumoniae isolates, we found a new PBP-profile, since that exact combination of PBP-subtypes was not in the database, or there were new substitutions in the PBPs. There was between 1 and 43 substitutions in the concatenated PBP-sequence, when compared to the best matching recognized PBP-profile. (Table 1). Among the 88 S. pneumoniae isolates, there were 37 unique PBP-profiles, of which 17 were a recognized PBP-profile.

Table 1.

Unique PBP-profiles and PBP1a-, PBP2b- and PBP2x-subtypes in Streptococcus pneumoniae and MLST and genomic serotypes.

| PBP-profile/nearest PPB-profile | Number of isolates | PBP-profile identity % | Substi-tutions | PBP1a | PBP2b | PBP2x | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest subtype | Substi-tutions | Nearest subtype | Substi-tutions | Nearest subtype | Substi-tuitions | MLST (n) | Serotypes (n) | ||||

| Type strain NTCT 7465 PT_0–4-0 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 1a0 | 0 | 2b4 | 0 | 2×0 | 0 | ST615 | 1 |

| PT_0–0-0 | 5 | 100 | 0 | 1a0 | 0 | 2b0 | 0 | 2×0 | 0 | 11,131, 452, 2,964, NA (2) | 12F, 24, 35D (3) |

| PT_0–0-0 | 1 | 99.89 | 1 | 1a0 | 0 | 2b0 | 1 | 2×0 | 0 | 7,179 | 24 |

| PT_0–0-0 | 2 | 99.23 | 7 | 1a86 | 0 | 2b82 | 0 | 2×162 | 0 | 448,1,229 | NT |

| PT_0–0-2 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 1a0 | 0 | 2b0 | 0 | 2×2 | 0 | 4,753 | 10A |

| PT_0–0-28 | 10 | 99.12 | 8 | 1a2 | 0 | 2b0 | 0 | 2×28 | 7 | 162 (9), NA (1) | 24 |

| PT_0–0-3 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 1a0 | 0 | 2b0 | 0 | 2×3 | 0 | NA | 7C |

| PT_0–1-1 | 1 | 97.48 | 23 | 1a0 | 4 | 2b1 | 0 | 2×99 | 7 | 13,224 | 7C |

| PT_0–1-2 | 4 | 99.34 | 6 | 1a2 | 0 | 2b103 | 0 | 2×0 | 0 | 11,100 | 24 |

| PT_1–0-0 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 1a1 | 0 | 2b0 | 0 | 2×0 | 0 | 3,811 | 15A |

| PT_12–0-0 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 1a12 | 0 | 2b0 | 0 | 2×0 | 0 | 1,766 | 31 |

| PT_13–11-33 | 1 | 99.78 | 2 | 1a13 | 1 | 2b11 | 1 | 2×33 | 1 | 271 | 19F |

| PT_13–14-26 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 1a13 | 0 | 2b14 | 0 | 2×26 | 0 | 320 | 19A |

| PT_15–12-18 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 1a15 | 0 | 2b14 | 0 | 2×18 | 0 | 81 | 6A |

| PT-15-14-96 | 1 | 97.81 | 20 | 1a15 | 0 | 2b38 | 0 | 2×43 | 5 | NA | 6A |

| PT_15–16-8 | 1 | 99.78 | 2 | 1a15 | 0 | 2b12 | 0 | 2×8 | 0 | 156 | 11A |

| PT_15–7-8 | 1 | 98.91 | 10 | 1a15 | 0 | 2b49 | 0 | 2×36 | 0 | 166 | 11A |

| PT_15–7-8 | 1 | 98.36 | 15 | 1a15 | 0 | 2b76 | 0 | 2×36 | 4 | 838 | 9 V |

| PT_17–15-22 | 2 | 100 | 0 | 1a17 | 0 | 2b15 | 0 | 2×22 | 0 | 230, NA | 24 |

| PT_17–15-22 | 1 | 98.03 | 18 | 1a17 | 0 | 2b12 | 0 | 2×22 | 0 | 156 | 9 V |

| PT_17–15-22 | 2 | 97.16 | 26 | 1a17 | 0 | 2b15 | 0 | 2×171 | 3 | 4,253 | 24 |

| PT_17–16-47 | 1 | 99.56 | 4 | 1a17 | 0 | 2b39 | 0 | 2×18 | 0 | 276 | 19A |

| PT_18–7-8 | 1 | 97.15 | 26 | 1a10 | 0 | 2b53 | 0 | 2×20 | 0 | NA | 21 |

| PT_2–0-0 | 25 | 100 | 0 | 1a2 | 0 | 2b0 | 0 | 2×0 | 0 | 72 (23), 2,567 (2) | 24 (23), 29 (2) |

| PT_20–18-25 | 1 | 98.58 | 13 | 1a8 | 4 | 2b18 | 0 | 2×25 | 0 | 275 | 15B |

| PT_2–0-2 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 1a2 | 0 | 2b0 | 0 | 2×2 | 0 | 1,262 | 15C |

| PT_2–6-2 / PT_1–6-0 | 1 | 99.78 | 2 | 1a1 | 0 | 2b82 | 0 | 2×2 | 0 | 2,369 | 20 |

| PT_27–11-8 | 1 | 97.81 | 20 | 1a47 | 1 | 2b11 | 0 | 2×8 | 2 | NA | NT |

| PT_34–32-43 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 1a34 | 0 | 2b32 | 0 | 2×43 | 0 | 179 | 19F |

| PT_34–89-147 | 1 | 99.67 | 3 | 1a25 | 0 | 2b7 | 0 | 2×56 | 0 | 8,991 | NT |

| PT_3–6-5 | 7 | 100 | 0 | 1a3 | 0 | 2b6 | 0 | 2×5 | 0 | 53 | 8 |

| PT_4–7-7 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 1a4 | 0 | 2b7 | 0 | 2×7 | 0 | 558 | 35B |

| PT_54–61-92 | 1 | 95.3 | 43 | 1a25 | 15 | 2b15 | 2 | 2×91 | 4 | NA | NT |

| PT_62–0-2 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 1a62 | 0 | 2b0 | 0 | 2×2 | 0 | NA | 3 |

| PT_7–1-1 | 3 | 100 | 0 | 1a7 | 0 | 2b1 | 0 | 2×1 | 0 | 1,349, 13,087 | 1, 23B |

| PT_7–1-30 | 1 | 98.91 | 10 | 1a7 | 0 | 2b1 | 0 | 2×123 | 3 | 3,369 | 35D |

| PT_78–0-0 | 7 | 100 | 0 | 1a78 | 0 | 2b0 | 0 | 2×0 | 0 | 162 | 24 |

| PT_8–67–103 | 1 | 100 | 0 | 1a8 | 0 | 2b67 | 0 | 2×103 | 0 | 135 | 6B |

None of the non-S. pneumoniae MGS had a recognized PBP-profile. In S. pseudopneumoniae, 5 of 19 isolates had a PBP2b sequence also found in S. pneumoniae, (PBP2b0). Nearest PBP-profiles had 11–19 substitutions in the concatenated PBP-sequence (Supplementary Table S2). The 33 S. mitis isolates were more diverse in their PBP profiles with no isolate having the exact same amino acid sequence as another isolate. Five isolates had a PBP2b and/or PBP2x-subtype that were recognized from S. pneumoniae (Supplementary Table S4). The S. oralis isolates generally had more substitutions (40–91) than S. mitis. In 22 of the 25 isolates, the nearest PBP-profile was PT_17–1-22, but mostly with different substitutions (Supplementary Table S6). The one S. infantis isolate had 94 substitutions (Supplementary Table S8).

3.2. Correlation of PBP-profile with MLST and genomic serotype in Streptococcus pneumoniae

For six unique PBP-profiles, isolates had several MLSTs, while for six other unique PBP-profiles all isolates with the same profile had the same MLST. Isolates with the same MLST profile could have different PBP-profiles, e.g., ST-162 isolates had both PT_0–0-28 (8 substitutions, 9 isolates) and PT_78–0-0- (7 substitutions, 7 isolates) as the nearest PBP-profile. Most isolates belonged to serogroup 24 but represented eight different PBP-profiles. Likewise, PT_0–0-0 and PT_2–0-0- were seen in more than one serotype (Table 1).

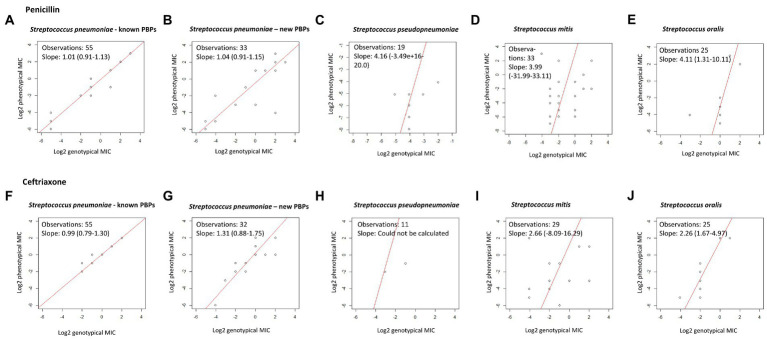

3.3. Penicillin: Correlation between genotypic MIC prediction and phenotypic susceptibility

Among the 55 S. pneumoniae isolates with a recognized PBP-profile, 46 were phenotypic and genotypic susceptible to penicillin, seven were phenotypic and genotypic susceptible-increased-exposure, and two were phenotypic and genotypic resistant, and this resulted in 100% CA (Table 2). EA was 98.2%; one isolate with a genotypic MIC of 2 μg/mL had a phenotypic MIC of 0.5 μg/mL (Table 3). Among the 33 isolates with a new PBP-profile not included in the database, more isolates had reduced susceptibility. CA was 90.9% with a MiD in two isolates and a MaD in one isolate (Table 2), and these three isolates contained many substitutions (23, 26, and 43). EA was 93.9% (Table 4). PPV and NPV for non-susceptibility were 93 and 94%. Genotypic-phenotypic accuracy using Deming regression showed a slope closer to unity for isolates with a recognized PBP-profile [1.01 (0.91–1.13)], compared to isolates with a new PBP-profile [1.04 (0.91–1.15)] (Figures 1A,B).

Table 2.

Phenotypic-genotypic correlation for penicillin and ceftriaxone susceptibility in S. pneumoniae and non-S. pneumoniae mitis group streptococci.

| S. pneumoniae | S. pneumoniae | S. pseudopneumoniae | S. mitis | S. oralis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recognized PBP-profiles | New PBP-profiles | ||||

| Number of isolates | 55 | 33 | 19 | 33 | 25 |

| PBP-substitutions | 0 | 1–43 | 11–24 | 9–66 | 40–91 |

| Penicillin susceptibility | |||||

| Genotypic S/I/R A | 46/7/2 | 18/8/7 | 19/0/0 | 25/6/2 | 1/23/1 |

| Phenotypic S/I/R A | 46/7/2 | 18/10/5 | 19/0/0 | 27/4/2 | 23/0/2 |

| Category agreement B | 100% (55/55) | 90.9% (30/33) | 100% (19/19) | 75.8% (25/33) | 8% (2/25) |

| Minor discrepancy C | 0% (0/63) | 5.9% (2/33) | 0% (0/19) | 18.2% (6/33) | 92% (23/25) |

| Major discrepancy D | 0% (0/63) | 2.9% (1/33) | 0% (0/19) | 3.0% (1/33) | 0% (0/25) |

| Very major discrepancy E | 0% (0/63) | 0% (0/33) | 0% (0/19) | 3.0% (1/33) | 0% (0/25) |

| Ceftriaxone susceptibility | |||||

| Genotypic S/I/R/NA A | 52/2/1 | 23/7/2/1 | 12/0/0 | 24/0/5/4 | 23/0/2 |

| Phenotypical S/I/R A | 51/3/1 | 24/7/2 | 18/0/0 | 30/0/3 | 23/0/2 |

| Category agreement B | 98.2% (54/55) | 93.8% (30/32) | 100% (11/11) | 86.2% (25/29) | 100% (25/25) |

| Minor discrepancy C | 1.8% (1/55) | 6.3% (2/32) | 0% (0/12) | 0% (0/29) | 0% (0/25) |

| Major discrepancy D | 0% (0/55) | 0% (0/32) | 0% (0/12) | 10.3% (3/29) | 0% (0/25) |

| Very major discrepancy E | 0% (0/55) | 0% (0/32) | 0% (0/12) | 3.4% (1/29) | 0% (0/25) |

A S/I/R: Susceptible standard dosing regimen/Susceptible increased exposure/Resistant according to EUCAST breakpoints v. 10.0. For S. pneumoniae: S: ≤0.06 mg/L (PEN), S ≤ 0.5 mg/L (CFT); I: 0.06–2 mg/L (PEN), 1–2 (CFT); R > 2 (PEN/CFT). For mitis group streptococci (S. viridans): S ≤ 0.25 (PEN), S ≤ 0.5 (CFT); I: 0.5–2 (PEN), R > 2 (PEN), R > 0.5 (CFT). B Category agreement: Same S / I / R category. C Minor discrepancy: Genotype S and phenotype I or genotype I and phenotype R or opposite. D Major discrepancy: Genotype R and phenotype S. E Very major discrepancy: Genotype S and phenotype R.

Table 3.

Genotypic and phenotypic susceptibility in Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates with a recognized PBP-profile.

| Isolate | ID | Year | Source of infection | PBP-profile | Substi-tutions | Oxacillin | Penicillin | Ceftriaxone | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pheno-typic mm | Geno-typic MIC | Geno-typic S-I-R | Pheno-typic MIC | Pheno-typic S-I-R | Geno-typic MIC | Geno-typic S-I-R | Pheno-typic MIC | Pheno-typic S-I-R | ||||||

| 2011–1853 | Pn1 | 2011 | Invasive | PT_0–0-0 | 0 | 25 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2017–0795 | Pn2 | 2017 | Invasive | PT_0–0-0 | 0 | 28 | ≤0.03 | S | 0.008 | S | ≤0.03 | S | 0,03 | S |

| 2017–0758 | Pn3 | 2017 | Invasive | PT_0–0-0 | 0 | 27 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2014–0010 | Pn4 | 2014 | Invasive | PT_0–0-0 | 0 | 30 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2018-F8-32 | Pn5 | 2018 | Respiratory | PT_0–0-0 | 0 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2018-F1-175 | Pn9 | 2018 | Respiratory | PT_0–0-2 | 0 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2017–4068 | Pn19 | 2017 | Invasive | PT_0–0-3 | 0 | 28 | ≤0.03 | S | 0.008 | S | ≤0.03 | S | 0.06 | S |

| 2018-F5-219 | Pn25 | 2018 | Invasive | PT_1–0-0 | 0 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.5 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2018-F1-282 | Pn26 | 2018 | Respiratory | PT_12–0-0 | 0 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2010–0479 | Pn28 | 2010 | Respiratory | PT_13–14-26 | 0 | NA | 8 | R | >4 | R | 4 | R | >2 | R |

| 2010–0164 | Pn29 | 2010 | Respiratory | PT_15–12-18 | 0 | NA | 4 | R | 4 | R | 2 | I | 2 | I |

| 2003–0373 | Pn34 | 2003 | Invasive | PT_17–15-22 | 0 | NA | 0.5 | I | 0.5 | I | 0.25 | S | 0.25 | S |

| 2008–1108 | Pn35 | 2008 | Invasive | PT_17–15-22 | 0 | NA | 0.5 | I | 1 | I | 0.25 | S | 0.5 | S |

| 2004–1073 | Pn41 | 2004 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 29 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2010–0993 | Pn42 | 2010 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 21 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2005–0741 | Pn43 | 2005 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 21 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2006–0579 | Pn44 | 2006 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 25 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2010–0510 | Pn45 | 2010 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 27 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2002–1030 | Pn46 | 2002 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 24 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2012–0390 | Pn47 | 2012 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 28 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2006–1119 | Pn48 | 2006 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 29 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2007–1134 | Pn49 | 2007 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 24 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2009–1199 | Pn50 | 2009 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 28 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2010–0805 | Pn51 | 2010 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 32 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 1999–0630 | Pn52 | 1999 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 29 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2005–0527 | Pn53 | 2005 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 24 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2015–0090 | Pn54 | 2014 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | 0.016 | S | ≤0.03 | S | 0.016 | S |

| 2014–0403 | Pn55 | 2014 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 29 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2014–0054 | Pn56 | 2014 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 27 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2004–1186 | Pn57 | 2004 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2007–0258 | Pn58 | 2007 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 29 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2013–0366 | Pn59 | 2013 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 29 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2016–0104 | Pn60 | 2016 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | 0,016 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2006–0194 | Pn61 | 2006 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2014–0100 | Pn62 | 2014 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 25 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2012–0272 | Pn63 | 2012 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 29 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2009–0273 | Pn64 | 2009 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | 28 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2013–0128 | Pn65 | 2013 | Invasive | PT_2–0-0 | 0 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | 0,03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2018-F1-70 | Pn67 | 2018 | Respiratory | PT_2–0-2 | 0 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | 0.06 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2010–0976 | Pn70 | 2010 | Respiratory | PT_34–32-43 | 0 | NA | 2 | I | 2 | I | ≤0.5 | S | 1 | I |

| 2018-F11-21 | Pn72 | 2018 | Invasive | PT_3–6-5 | 0 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2018-F2-278 | Pn73 | 2018 | Invasive | PT_3–6-5 | 0 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2018-F11-42 | Pn74 | 2018 | Invasive | PT_3–6-5 | 0 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2006–0685 | Pn75 | 2006 | Respiratory | PT_4–7-7 | 0 | NA | 2 | I | 0,5 | I | 1 | I | 1 | I |

| 2018-F9-15 | Pn77 | 2018 | Invasive | PT_62–0-2 | 0 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2018-F7-86 | Pn78 | 2018 | Invasive | PT_7–1-1 | 0 | NA | 0.25 | I | 0.25 | I | ≤0.5 | S | <0.12 | S |

| 2018-F2-190 | Pn79 | 2018 | Invasive | PT_7–1-1 | 0 | NA | 0.25 | I | 0.25 | I | ≤0.5 | S | <0.12 | S |

| 2012–0263 | Pn81 | 2012 | Invasive | PT_78–0-0 | 0 | 28 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2014–0149 | Pn82 | 2014 | Invasive | PT_78–0-0 | 0 | 28 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2016–0201 | Pn83 | 2016 | Invasive | PT_78–0-0 | 0 | 28 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2016–0041 | Pn84 | 2016 | Invasive | PT_78–0-0 | 0 | 29 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2015–0120 | Pn85 | 2015 | Invasive | PT_78–0-0 | 0 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | 0.016 | S | ≤0.03 | S | 0.008 | S |

| 2015–0641 | Pn86 | 2015 | Invasive | PT_78–0-0 | 0 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | 0.016 | S | ≤0.03 | S | 0.008 | S |

| 2015–0096 | Pn87 | 2015 | Invasive | PT_78–0-0 | 0 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | 0.03 | S | ≤0–03 | S | 0.016 | S |

| 2007–0130 | Pn88 | 2007 | Respiratory | PT_8–67–103 | 0 | NA | 0.5 | I | 0.25 | I | ≤0.5 | S | 0.25 | S |

Table 4.

Genotypic and phenotypic susceptibility in Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates with a new PBP-profile.

| Isolate | ID | Year | Source of infection | Nearest PBP-profile | Substi-tutions | Oxacillin | Penicillin | Ceftriaxone | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pheno-typic mm | Geno-typic MIC | Geno-typic S-I-R | Pheno-typic MIC | Pheno-typic S-I-R | Geno-typic MIC | Geno-typic S-I-R | Pheno-typic MIC | Pheno-typic S-I-R | ||||||

| 2003-24F | Pn6 | 1943 | Respiratory | PT_0–0-0 | 1 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | 0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | 0.12 | S |

| 2018-F10-36 | Pn7 | 2018 | Other | PT_0–0-0 | 7 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2018-F8-14 | Pn8 | 2018 | Other | PT_0–0-0 | 7 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2018-F11-2 | Pn10 | 2018 | Respiratory | PT_0–0-28 | 8 | NA | 0.06 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.5 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2017–0068 | Pn11 | 2017 | Invasive | PT_0–0-28 | 8 | NA | 0.06 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.5 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2015–0223 | Pn12 | 2015 | Invasive | PT_0–0-28 | 8 | NA | 0.06 | S | 0.03 | S | ≤0.5 | S | 0.06 | S |

| 2017–0345 | Pn13 | 2017 | Invasive | PT_0–0-28 | 8 | NA | 0.06 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.5 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2016–0350 | Pn14 | 2016 | Invasive | PT_0–0-28 | 8 | NA | 0.06 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.5 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2007–0834 | Pn15 | 2007 | Invasive | PT_0–0-28 | 8 | NA | 0.06 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.5 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2009–0811 | Pn16 | 2009 | Invasive | PT_0–0-28 | 8 | NA | 0.06 | S | 0.03 | S | ≤0.5 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2014–0404 | Pn17 | 2014 | Invasive | PT_0–0-28 | 8 | NA | 0.06 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.5 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2014–0747 | Pn18 | 2014 | Invasive | PT_0–0-28 | 8 | NA | 0.06 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.5 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2016–0487 | Pn20 | 2016 | Invasive | PT_0–1-1 | 23 | 12 | 0.06 | S | 0.25 | I | 0.12 | S | 0.12 | S |

| 2013–0682 | Pn21 | 2013 | Invasive | PT_0–1-2 | 6 | 29 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | 0.06 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2014–0669 | Pn22 | 2014 | Invasive | PT_0–1-2 | 6 | 25 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | 0.06 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2015–0182 | Pn23 | 2015 | Invasive | PT_0–1-2 | 6 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | 0.016 | S | 0.06 | S | 0.016 | S |

| 2008–0266 | Pn24 | 2008 | Invasive | PT_0–1-2 | 6 | 24 | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | 0.06 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 2010–0812 | Pn27 | 2010 | Respiratory | PT_13–11-33 | 2 | NA | 4 | R | >4 | R | 4 | R | >2 | R |

| 2010–0661 | Pn30 | 2010 | Respiratory | PT_15–14-96 | 20 | NA | 8 | R | 4 | R | >2 | R | 1 | I |

| 2010–129 | Pn31 | 2010 | Respiratory | PT_15–16-8 | 2 | NA | 1 | I | 2 | I | 1 | I | 1 | I |

| 2010–1247 | Pn32 | 2010 | Respiratory | PT_15–7-8 | 10 | NA | 4 | R | 4 | R | 1 | I | 2 | I |

| 2010–1060 | Pn33 | 2010 | Respiratory | PT_15–7-8 | 15 | NA | 4 | R | 4 | R | 1 | I | 2 | I |

| 2002–1038 | Pn36 | 2002 | Respiratory | PT_17–15-22 | 18 | NA | 0.5 | I | 0.5 | I | 0.25 | S | 0.50 | S |

| 2013–0699 | Pn37 | 2013 | Invasive | PT_17–15-22 | 26 | NA | 0.5 | I | 0.5 | I | ≤0.5 | S | 0.25 | S |

| 2015–0233 | Pn38 | 2015 | Invasive | PT_17–15-22 | 26 | NA | 0.5 | I | 0.5 | I | 0.25 | S | 0.25 | S |

| 2010–1006 | Pn39 | 2010 | Respiratory | PT_17–16-47 | 4 | NA | 2 | I | 2 | I | 2 | I | 1 | I |

| 2010–0484 | Pn40 | 2010 | Respiratory | PT_18–7-8 | 26 | NA | 4 | R | 2 | I | 1 | I | 2 | I |

| 2002–1043 | Pn66 | 2002 | Respiratory | PT_20–18-25 | 13 | NA | 1 | I | 0.12 | I | ≤0.5 | S | 0.25 | S |

| 2018-F8-24 | Pn68 | 2018 | Invasive | PT_2–6-2/ PT_1–6-0 | 2 | NA | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.03 | S | ≤0.12 | S |

| 1999–1138 | Pn69 | 1999 | Respiratory | PT_27–11-8 | 20 | NA | 4 | R | 4 | R | 1 | I | 4 | R |

| 2010–1248 | Pn71 | 2010 | Respiratory | PT_34–89-147 | 3 | NA | 2 | I | 2 | I | 1 | I | 1 | I |

| 2018-F5-29 | Pn76 | 2018 | Respiratory | PT_54–61-92 | 43 | NA | 4 | R | 0.06 | S | NA | NA | ≤0.12 | S |

| PROJ-57-2 | Pn80 | NA | Respiratory | PT_7–1-30 | 10 | NA | 0.25 | I | 0.12 | I | ≤0.5 | S | 0.25 | S |

Figure 1.

Deming regression of genotypic and phenotypic MIC for penicillin and ceftriaxone. Using log2-transformed genotypic and phenotypic MIC, statistical software R. A slope of 1 indicates exact MIC agreement. (A–E) Show results for penicillin. (F–J) Show results for ceftriaxone.

All S. pseudopneumoniae isolates were phenotypic and genotypic susceptible toward penicillin and CA was 100%. Among S. mitis isolates of which 27 were phenotypic susceptible, CA was only 75.8% with six MiD, one MaD, and one VMaD. Among S. oralis, two isolates were phenotypically resistant toward penicillin; one was resistant and one was susceptible-increased-exposure by genotype. The remaining isolates were phenotypically susceptible, but all except one was susceptible-increased-exposure by genotypic prediction, resulting in a very poor CA of 8% (2 of 25) (Table 2). All phenotypic and genotypic MICs for penicillin are presented in Supplementary Tables S3, S5, S7 and S9. Compared to S. pneumoniae, the non-S. pneumoniae MGS had much poorer MIC correlation in Deming regression curves (Figures 1C–E).

3.4. Ceftriaxone: Correlation between genotypic MIC prediction and phenotypic susceptibility

For S. pneumoniae isolates with a recognized PBP-profile, 52 isolates were genotypic susceptible, but one isolate with a genotypic MIC of ≤0.5 μg/mL had a phenotypic MIC of 1 μg/mL resulting in one MiD (1.8%) and thus a CA of 98.2%. This was however a single dilution difference. For isolates with a new PBP-profile, one isolate had no available genotypic MIC in the CDC PBP-to-MIC database. CA for S. pneumoniae isolates was 93.8%, and two isolates had a MiD. PPV and NPV for non-susceptibility was 100 and 98%. S. pseudopneumoniae isolates with an available susceptibility had a CA of 100%. In S. mitis, 30 isolates were phenotypic susceptible toward ceftriaxone, and three isolates had reduced phenotypic susceptibility. CA was 86.2% with three MaD and one VMaD. In S. oralis, two isolates were both phenotypic and genotypic resistant toward ceftriaxone, and the remaining isolates were genotypic and phenotypic susceptible with a 100% CA (Table 2). Genotypic-phenotypic MIC correlation for ceftriaxone is shown in Figures 1F–J.

3.5. Genotypic prediction based on a single PBP subtype

We explored whether identifying the PBP subtype of only one of three PBPs in an isolate, could be enough to predict susceptibility (S, I or R), and this was the case for many subtypes. However, both susceptible and susceptible-increased-exposure isolates had common subtypes, such as PBP2b0, PBP2x0 or PBP2x2. For PBP1a only a few subtypes always predicted high level resistance, while other subtypes could be either I or R, or even S or R for one subtype (Supplementary Table S10). Therefore, it is necessary to identify the subtype of all three PBPs to predict susceptibility correctly.

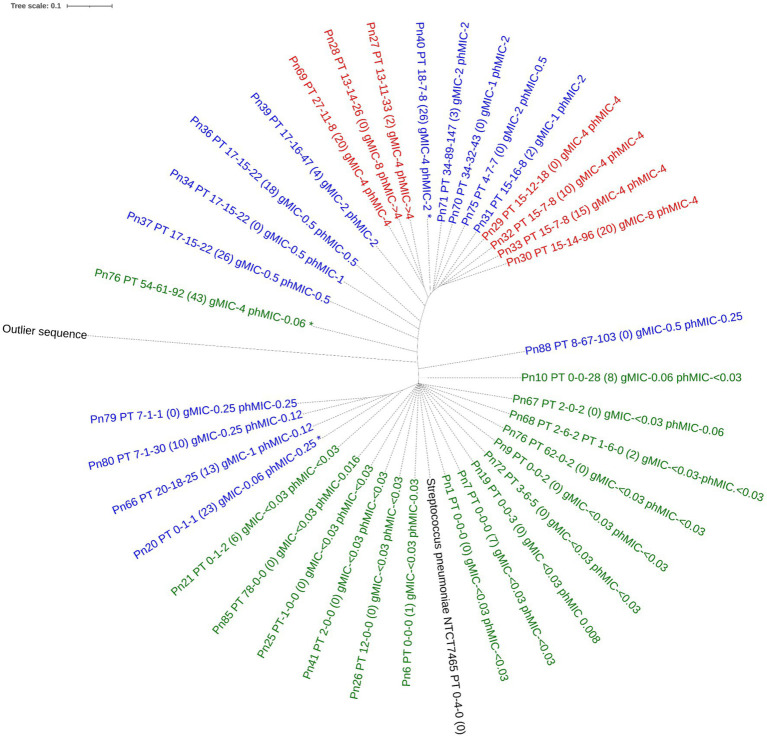

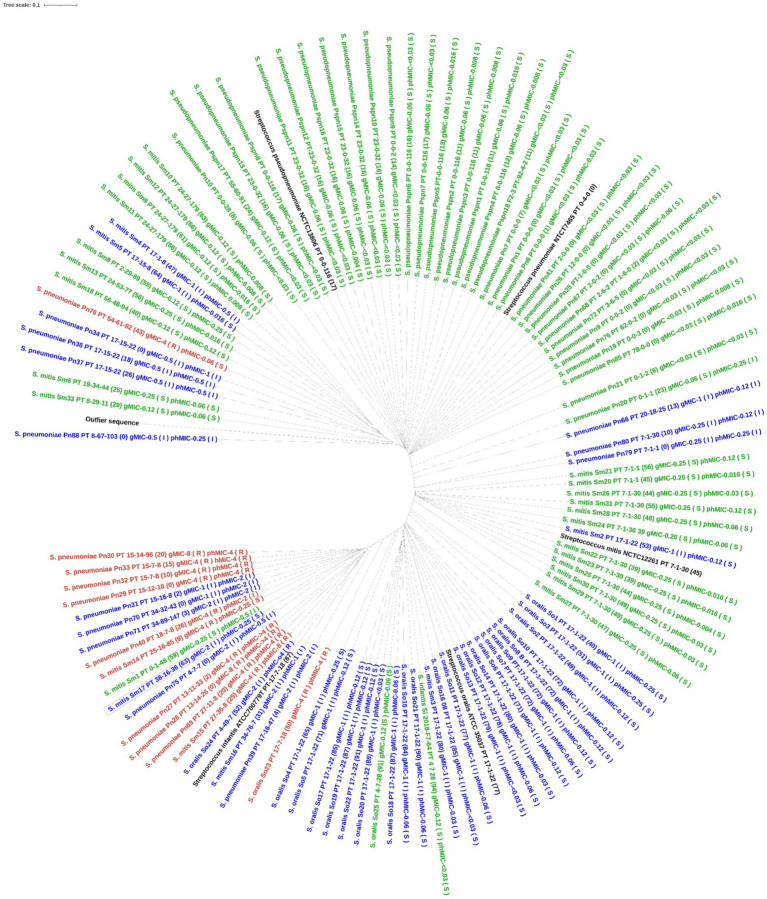

3.6. Phylogenetic analysis of the PBP-TPD

For S. pneumoniae, the concatenated PBP amino acid sequence of the susceptible isolates clustered with that of the S. pneumoniae reference genome (NTCT 7465). Phenotypic non-susceptible isolates clustered in one larger group including isolates being either susceptible-increased-exposure or resistant and in one smaller group, where one isolate, Pn20, was susceptible by genotype. This isolate had 23 substitutions to the nearest PBP-type, which may explain this finding. Only one unique profile (isolate, Pn76) was susceptible by phenotype, but resistant by genotype (MaD). Three isolates, all with PBP-profile PT_17–15-22, but with 0, 18, and 26 substitutions respectively, clustered together and had similar phenotypic MICs between 0.5 and 1 μg/mL, indicating no functional importance of these substitutions on susceptibility (Figure 2). When including all species in the analysis, the type strains for S. pneumoniae, S. pseudopneumoniae, S. mitis and S. oralis all clustered with susceptible isolates of that species. A separate cluster of susceptible S. mitis isolates was seen, and both S. mitis clusters had related non-susceptible S. pneumoniae isolates, suggesting a horizontal gene transfer between these two species. The one S. infantis isolate clustered with one S. mitis and one S. oralis isolate, both susceptible by phenotype, but susceptible-increased-exposure by genotype. A separate cluster included isolates of S. pneumoniae, S. mitis and S. oralis being susceptible-increased-exposure and resistant, and surprisingly, the S. infantis type strain was in this cluster (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of the concatenated amino acid sequence of PBP1a, PBP2b and PBP2x in Streptococcus pneumoniae with unique PBP-profiles. The tree was constructed using IQ-TREE software with a Blosum62 substitution model. Label contains isolate id, nearest PBP-profile (number of PBP amino acid substitutions), genotypic MIC, phenotypic MIC. Tree is colored by phenotypical susceptibility: Green is susceptible standard dosing regimen blue is susceptible increased exposure, red is resistant. The outlier sequence was constructed from Streptococcus dysgoloctiae AC2713. *indicates category disagreement.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree of the concatenated PBP amino acid sequence in all mitis group streptococci. The tree was constructed using IQ-TREE software with Blosum62 substitution model. Label contains species and isolate id, nearest PBP-profile (number of PBP amino acid substitutions), genotypic MIC, phenotypic MIC. Tree is colored by genotypic susceptibility (green is susceptible, blue is susceptible increased exposure, red is resistant). The outlier sequence was constructed from Streptococcus dysgalactiae AC2713.

4. Discussion

We studied genotypic prediction of β-lactam susceptibility in selected isolates of Danish S. pneumoniae and internationally collected non-S. pneumoniae MGS using a different method than previously described (Li et al., 2016; Metcalf et al., 2016b), namely BLAST analysis. This method only requires basic bioinformatic skills. Prediction was based on the concatenated amino acid sequence of the TPD of PBP1a, PBP2b and PBP2x in S. pneumoniae. There was an excellent prediction of β-lactam susceptibility in S. pneumoniae isolates with recognized PBP-profiles. There was a good prediction in S. pneumoniae isolates with new PBP-profiles when the nearest PBP-profile, identified by BLAST analysis, was used. Overall, the method performed well in Danish S. pneumoniae isolates. The method itself could also be applied to non-S. pneumoniae MGS, but none of these MGS species had a recognized PBP-profile. Using the database validated for S. pneumoniae, susceptibility to penicillin and ceftriaxone was poorly predicted for non-S. pneumoniae MGS. The method could potentially be used in non-S. pneumoniae MGS if a similar database is developed and validated using a larger collection of β-lactam susceptible and resistant isolates.

In our study, CA for S. pneumoniae was 100% for penicillin and 98.2% for ceftriaxone in isolates with a recognized PBP-profile. This is comparable with results from other studies. Li et al. (2016) tested three statistical models for genomic MIC prediction of β-lactam antibiotics. If a PBP-profile was present in the training dataset, EA was >98% and CA was >94%, for isolates in the test dataset [“mode MIC” (MM) statistical model]. In a subsequent study (Li et al., 2017), there was an acceptable performance for all β-lactams, with an EA of >97% and a CA of >90% (Random Forest model). Metcalf et al. (2016a) analyzed 2205 isolates with 145 recognized PBP-profiles and found that CA was 97.3%. Of 1724 isolates being phenotypic susceptible, 0.8% had wrong category predicted, this was 6% among 418 I-isolates, and 33.3% among 63 R- isolates.

We found that 54% of isolates had a new PBP-profile. Geographical differences in PBP-subtypes in circulating strains may explain this. It may also reflect that TPD-PBP substitutions continuously develop, due to the usage of β-lactam antibiotics which correlates to the proportion of non-susceptible S. pneumoniae isolates (Jensen et al., 2015). Regarding susceptibility prediction for isolates with a new PBP-profile, we found that CA for penicillin was 90.9%, MaD was 2.9% and there was no VMaD. Li et al. [14] found that EA and CA for penicillin was approximately 90% when the PBP-profile was not in the training dataset. MaD and VMaD were too high for all models in their study. Thus, regarding CA, our method, using a simple BLAST analysis, was not inferior to the previously published statistical models, both for isolates with a recognized and with a new PBP-profile.

Molecular based diagnostic tests are increasingly being explored as a supplement to culture, e.g., in bacterial meningitis (Moon et al., 2019; Nakagawa et al., 2019; Hong et al., 2020). This is particularly of value in pathogen positive, but culture negative specimens, e.g., due to prior antibiotic treatment. Genotypic susceptibility prediction could potentially ensure appropriate and narrow antibiotic treatment, when culture is not possible. In a clinical setting, a consensus is needed regarding the accepted CA, MaD and VMaD and whether this is different, depending on the type of infection. Using our BLAST method, genotypical susceptibility prediction may be safe to guide treatment, if a recognized PBP-profile is identified since CA was 100% for penicillin and 98.2% for ceftriaxone. In particular, when treating severe invasive infections we could have concerns using our method in isolates with new PBP-profiles with a CA of 90.9% (penicillin) and 93.8% (ceftriaxone). From a surveillance perspective, we find our results of the overall CA for S. pneumoniae acceptable, being 90.9–100%. Including culture negative specimens in the surveillance could provide more accurate estimates of susceptibility in circulating strains.

To our knowledge, this study is among the first published studies that explores phenotypic-genotypic susceptibility in non-S. pneumoniae MGS. For these species, and especially for the S. mitis species, there was a poor prediction of susceptibility using the database validated for S. pneumoniae. In S. pneumoniae, the number of substitutions in the PBPs correlates with reduced susceptibility (Li et al., 2016). For the non-S. pneumoniae MGS, both susceptible and non-susceptible isolates had many substitutions. Whether these substitutions reflect reduced susceptibility, or a different species is not clear. Although the prediction was poor, the method itself could easily be applied to the non-S. pneumoniae MGS, which had PBP-sequences of equal length as S. pneumoniae.

A limitation is that we studied a selected group of isolates. Our isolates were not representative of current clinical samples, except for isolates from the ODiD-project. Overall, there were more non-susceptible S. pneumoniae isolates than in the Danish national surveillance (DANMAP, 2019). Another limitation is that phenotypic testing was performed by different laboratories with different methods for susceptibility testing. Retesting was not possible in case of MIC discrepancies.

When using BLAST analysis the result is highly dependent on the number of isolates in the database. For S. pneumoniae our method provided an acceptable susceptibility prediction, but the robustness and reproducibility of our method needs to be tested in further studies using clinical isolates. In particular, validation for non-susceptible isolates is needed, since this has the greatest clinical impact. If databases for PBP-profile and phenotypic MIC correlation are improved, the need for validating the method for isolates with new PBP-profiles is less important.

We only included few non-S. pneumoniae MGS isolates. For these species, a much larger validation is needed using species-specific PBP-profile to MIC databases. This would be particularly challenging for the S. mitis species, since they have very diverse PBP-profiles, even among susceptible strains. This was also reflected in our data. A continuous surveillance of PBP-profiles and the correlating phenotypic susceptibility in circulating strains of S. pneumoniae and non-S. pneumoniae MGSis challenging but also necessary for the performance of the method.

In conclusion, in Danish S. pneumoniae isolates, our alternative method for prediction of β-lactam susceptibility from genomic data, using BLAST analysis, had a performance comparable to other studies for recognized PBP-profiles. Isolates with a new PBP-profile had an acceptable susceptibility prediction but the method needs further validation. The method could be applied to other MGS, but prediction was poor. The PBP classification system is an important step in the direction of genotypic susceptibility testing of streptococci for routine diagnostic purposes. This could improve susceptibility testing in pathogen positive, but culture negative clinical specimens.

Data availability statement

Regarding access to the data, the datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author contributions

HE, KF, KS, and H-CS: conception of the work. HE, KF, AJ, CJ, XN, JC, PS, AR, FA, KS, H-CS, and the ODiD Consortium: laboratory investigation and bioinformatics, critical revision of the article, and final approval of the article. HE, KS, KF, and H-CS: drafting of the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

H-CS is involved with projects supported by Pfizer.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

Members of the One Day in Denmark (ODiD) Consortium are as follows:

Valeria Bortolaia; Pimlapas Leekitcharoenphon, Technical University of Denmark, National Food Institute, Kongens Lyngby, Denmark; Dennis Schrøder Hansen; Herlev Hospital, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Herlev, Denmark; Hans Linde Nielsen; Aalborg University Hospital, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Aalborg, Denmark; Svend Ellermann-Eriksen and Niels Nørskov-Lauritsen; Aarhus University Hospital, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Aarhus, Denmark; Michael Kemp; Odense University Hospital, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Odense, Denmark; Bent Løwe Røder; Slagelse Hospital, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Slagelse, Denmark; Niels Frimodt-Møller; Rigshospitalet, Department of Clinical Microbiology, København, Denmark; Turid Snekloth Søndergaard; Hospital of Southern Jutland, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Sønderborg, Denmark; John Eugenio Coia; Sydvestjysk Hospital, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Esbjerg, Denmark; Claus Østergaard; Vejle Hospital, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Vejle, Denmark; Henrik Westh; Hvidovre Hospital, Department of Clinical Microbiology, Hvidovre, Denmark, and Department of Clinical Medicine, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Kirsten Burmeister and Karina Kaae are acknowledged for their skilled laboratory work and guidance in this study. We acknowledge the Danish Departments of Clinical Microbiology for submitting invasive pneumococcal isolates for national surveillance throughout the study period.

Footnotes

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1120023/full#supplementary-material

References

- Arbique J. C., Poyart C., Trieu-Cuot P., Quesne G., Carvalho M. D. G. S., Steigerwalt A. G., et al. (2004). Accuracy of phenotypic and genotypic testing for identification of Streptococcus pneumoniae and description of Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae sp. nov. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 4686–4696. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4686-4696.2004, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J. S., Jensen T. G., Kolmos H. J., Pedersen C., Lassen A. (2012). Bacteremia with Streptococcus pneumoniae: Sepsis and other risk factors for 30-day mortality-a hospital-based cohort study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 31, 2719–2725. doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1619-5, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DANMAP (2009) “Appendix 2 Materials and Methods, Susceptibility Tesring,” in Use of antimicrobial agents and occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria from food animals, foods and humans in Denmark. eds. Jensen V. F., Hammerum A. M. (Statens Serum Institute; Danish Veterinary and Food Administration; Danish Medicines Agency; National Veterinary Institute, Technical University of Denmark and National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark; ), 128–129. [Google Scholar]

- DANMAP (2019). “Resistance in human pathogens, 8.3.5 Streptococcus pneumoniae; ” in Use of antimicrobial agents and occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria from food animals, food and humans in Denmark. (Statens Serum Institut and National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark; ), 126. [Google Scholar]

- Ellington M. J., Ekelund O., Aarestrup F. M., Canton R., Doumith M., Giske C., et al. (2017). The role of whole genome sequencing in antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bacteria: report from the EUCAST subcommittee. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 23, 2–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.11.012, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epping L., van Tonder A. J., Gladstone R. A., Bentley S. D., Page A. J., Keane J. A. (2018). SeroBA: rapid high-throughput serotyping of Streptococcus pneumoniae from whole genome sequence data. Microb. Genomics 4, 1–6. doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000186, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuursted K., Littauer P. J., Greve T., Scholz C. F. P. (2016). Septicemia with Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae: report of three cases with an apparent hepatic or bile duct association. Infect. Dis. 48, 636–639. doi: 10.3109/23744235.2016.1157896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib G., Hoen B., Tornos P., Thuny F., Prendergast B., Vilacosta I., et al. (2009). Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infective endocarditis (new version 2009). Eur. Heart J. 30, 2369–2413. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp285, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakenbeck R., Brückner R., Denapaite D., Maurer P. (2012). Molecular mechanisms of b -lactam resistance in. Future Microbiol. 7, 395–410. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.2, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong N. T. T., Nghia H. D. T., Thanh T. T., Lan N. P. H., Ny N. T. H., Ngoc N. M., et al. (2020). Cerebrospinal fluid MinION sequencing of 16S rRNA gene for rapid and accurate diagnosis of bacterial meningitis. J. Infect. 80, 469–496. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2019.12.011, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen C. S., Iversen K. H., Dargis R., Shewmaker P., Rasmussen S., Christensen J. J., et al. (2021). Streptococcus pseudopneumoniae: use of whole-genome sequences to validate species identification methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 59, 1–11. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02503-20, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen A., Scholz C. F. P., Kilian M. (2016). Re-evaluation of the taxonomy of the mitis group of the genus Streptococcus based on whole genome phylogenetic analyses, and proposed reclassification of Streptococcus dentisani as Streptococcus oralis subsp. dentisani comb. nov., Streptococcus tigurinus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 66, 4803–4820. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001433, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen A., Valdórsson O., Frimodt-Møller N., Hollingshead S., Kilian M. (2015). Commensal streptococci serve as a reservoir for β-lactam resistance genes in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 3529–3540. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00429-15, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley K. A., Bray J. E., Maiden M. C. J. (2018). Open-access bacterial population genomics: BIGSdb software, the PubMLST.org website and their applications [version 1; referees: 2 approved]. Wellcome Open Res. 3, 124–120. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.14826.1, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavalari I. D., Fuursted K., Krogfelt K. A., Slotved H. C. (2019). Molecular characterization and epidemiology of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 24F in Denmark. Sci. Rep. 9, 5481–5489. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41983-8, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Metcalf B. J., Chochua S., Li Z., Gertz R. E., Walker H., et al. (2016). Penicillin-binding protein transpeptidase signatures for tracking and predicting β-lactam resistance levels in Streptococcus pneumoniae. mBio 7:e00756-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00756-16, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Metcalf B. J., Chochua S., Li Z., Gertz R. E., Walker H., et al. (2017). Validation of β-lactam minimum inhibitory concentration predictions for pneumococcal isolates with newly encountered penicillin binding protein (PBP) sequences. BMC Genomics 18, 621–610. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4017-7, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf B. J., Chochua S., Gertz R. E., Li Z., Walker H., Tran T., et al. (2016a). Using whole genome sequencing to identify resistance determinants and predict antimicrobial resistance phenotypes for year 2015 invasive pneumococcal disease isolates recovered in the United States. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 22, 1002.e1–1002.e8. doi: 10.1016/J.CMI.2016.08.001, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf B. J., Gertz R. E., Gladstone R. A., Walker H., Sherwood L. K., Jackson D., et al. (2016b). Strain features and distributions in pneumococci from children with invasive disease before and after 13-valent conjugate vaccine implementation in the USA. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 22, 60.e9–60.e29. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.08.027, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon J., Kim N., Kim T. J., Jun J. S., Lee H. S., Shin H. R., et al. (2019). Rapid diagnosis of bacterial meningitis by nanopore 16S amplicon sequencing: a pilot study. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 309:151338. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2019.151338, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa S., Inoue S., Kryukov K., Yamagishi J., Ohno A., Hayashida K., et al. (2019). Rapid sequencing-based diagnosis of infectious bacterial species from meningitis patients in Zambia. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 8:e01087-11. doi: 10.1002/cti2.1087, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen L. T., Schmidt H. A., Von Haeseler A., Minh B. Q. (2015). IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen L. H., Dargis R., Højholt K., Christensen J. J., Skovgaard O., Justesen U. S., et al. (2016). Whole genome sequencing as a tool for phylogenetic analysis of clinical strains of Mitis group streptococci. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 35, 1615–1625. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2700-2, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebelo A. R., Ibfelt T., Bortolaia V., Leekitcharoenphon P., Hansen D. S., Nielsen H. L., et al. (2022). One Day in Denmark: Nationwide point-prevalence survey of human bacterial isolates and comparison of classical and whole-genome sequence-based species identification methods. PLoS One 17:e0261999-17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261999, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. M., Klugman K. P. (1998). Alterations in PBP 1a essential for high-level penicillin resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42, 1329–1333. doi: 10.1128/AAC.42.6.1329, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Linden M., Otten J., Bergmann C., Latorre C., Liñares J., Hakenbeck R. (2017). Insight into the diversity of penicillin-binding protein 2x alleles and mutations in viridans streptococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, 1–18. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02646-16, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Regarding access to the data, the datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.