Abstract

With the numerous advances and broad applications of mobile health (mHealth), establishing concrete data sharing, privacy, and governance strategies at national (or regional) levels is essential to protect individual privacy and data usage. This article applies the recent Health Data Governance Principles to provide a guiding framework for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to create a comprehensive mHealth data governance strategy. We provide three objectives: (1) establish data rights and ownership to promote equitable benefits from health data, (2) protect people through building trust and addressing patients’ concerns, and (3) promote health value by enhancing health systems and services. We also recommend actions for realizing each objective to guide LMICs based on their unique mHealth data ecosystems. These objectives require adopting a regulatory framework for data rights and protection, building trust for data sharing, and enhancing interoperability to use new datasets in advancing healthcare services and innovation.

Keywords: data governance, digital health, global health informatics, mHealth, sustainable development goals (SDGs)

INTRODUCTION

The Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) has rapidly accelerated the global adoption of mobile health (mHealth) devices and software, which have become central public health tools for health monitoring, telemedicine, and surveillance.1,2 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), mHealth is defined as “the use of mobile wireless technologies for public health,” which encompasses a vast array of tools to support health such as mobile phones, wearable sensors, and video applications (apps).3 mHealth tools have been increasingly used in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), particularly short messaging service approaches, with evidence suggesting effective delivery of health information to patients for disease management and support for healthcare workers.4,5 The United Nations has also incorporated mHealth into their Sustainable Development Goals6,7 to address global challenges such as poverty and the lack of universal health coverage.8 While use of mHealth data has demonstrated positive impacts in public health planning and response,2,9 data governance regulations have lagged behind innovation.10 For example, with the wide use of contact-tracing apps, data sharing is a complex issue regarding which types of data are collected, how they are stored, for how long, and who has access.4 Some governments have endorsed apps that track individuals during quarantine11,12 or even enforce quarantine by asking individuals to submit “selfies.”13 These challenges span a number of domains, including data privacy, ownership, protection, consent, and ethics.14 LMICs are notably faced with these challenges,15,16 as many lack digital data governance strategies.17 Careful consideration of data governance and regulatory issues in LMICs is essential to realize the full promise of mHealth to improve health outcomes and delivery.18,19

To address some of these challenges, several frameworks and strategies have been developed to guide health data regulation and governance.15,20 For example, the WHO global strategy on digital health (2020–2025)21 set a strategic objective for digital health governance at national and international levels through the creation of sustainable and robust governance structures, including regulatory frameworks. The Lancet Commission also developed a conceptual framework on digital technologies as new determinants of health.10 The framework includes data governance as one of ten potential enablers of digital health future readiness, with emphasis on equity and human rights. Additionally, key elements of digital data governance have been outlined to protect and promote well-being of vulnerable populations in LMICs.20 In this article, we build upon this body of existing work to create an mHealth data governance framework with a set of recommended actions for LMICs.

HEALTH DATA GOVERNANCE PRINCIPLES

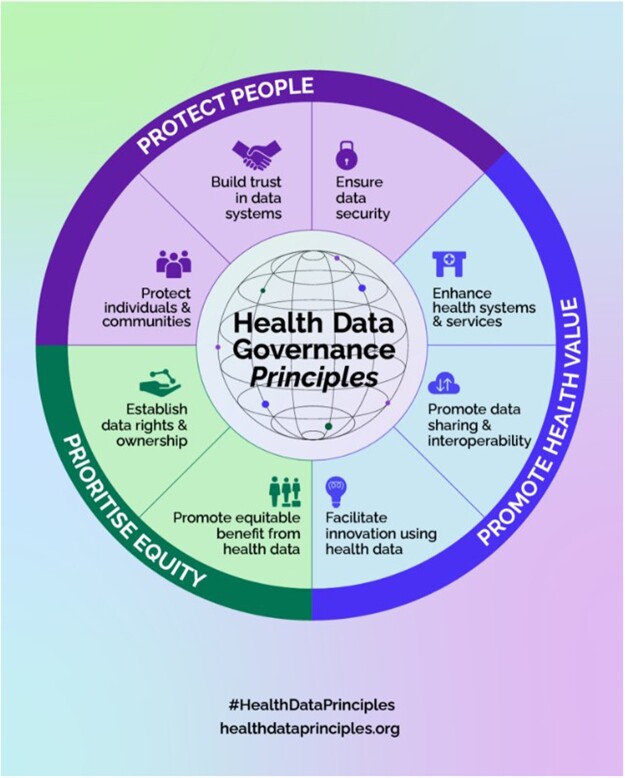

In April 2022, the Health Data Governance Principles22 were created to universalize the benefits of digital health through protecting people, promoting health value, and prioritizing equity. These principles, developed in partnership with more than 200 digital health experts from over 130 global organizations, are the first global set of principles developed to guide the use of data in health systems (Figure 1). The principles are grounded in human rights and equity to support public health systems that can deliver healthcare broadly. They balance the rights of individuals with the rights of organizations and public health. This creates a common vision where people and communities can share, use, and benefit from health data. Drawing upon these principles, we provide tailored objectives and recommendations, encompassing tools and guiding examples, that could be used to guide LMICs in mHealth data governance (Table 1). This work was conducted by members of the Health Level Seven International (HL7®) Patient Contributed Data group, which focuses on identifying principles and rights for patients and their data as well as assessing standards that impact patient contributed data.

Figure 1.

Health data governance principles.22

Table 1.

mHealth data governance mapped to health data governance principles

| Health data governance principles | Objectives | Recommended actions for mHealth data governance in LMICs |

|---|---|---|

| Prioritize equity | Objective 1: Prioritize equity through establishing mHealth data rights and ownership |

|

| Used framework: EU GDPR | Guiding example : A checklist for implementing digital data governance principles | |

| Protect people | Objective 2: Protect people through building trust and representing the patients’ perspective on mHealth data |

|

| Used tool: The Data Futures Partnership in New Zealand | Guiding example: Digital Health Europe project | |

| Promote health value | Objective 3: Promote health value through enhancing systems and services representing the health system’s perspective on mHealth data |

|

| Used tool: The WHO guidance on the ethics and governance of AI in health | Guiding example: principles and norms governing responsible data sharing in international health research | |

| Next steps |

|

|

| Examples on how to use this framework in LMICs |

|

|

Objective 1: prioritize equity through establishing mHealth data rights and ownership

mHealth data governance should be based on strong and clear data-related rights, including the basic human rights to protection, safety, and to benefit equitably from data contributed at individual and community levels. Indigenous researchers in the United States have put forth recommendations for considering ethics around health research and data that center on group-level concerns and tribal autonomies and sovereignties, aligning with Indigenous communitarian ethics, rather than “Western” individualistic ethics.23

Define mHealth data governance roles and responsibilities

To ensure mHealth data rights and ownership, it is valuable to define various mHealth data roles within health data systems in light of a data protection framework, including: data owner, data custodian, data processor, data steward, data trustee, and data use beneficiary. Establishing roles helps to clarify who has the right to do what and who must ensure these rights are upheld.

At a national or regional level, a regulatory framework using existing data governance guidelines, such as in the European Union’s (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR),24 should identify:

rights and roles of primary mHealth data actors (individuals, family members, caregivers, healthcare providers).

ownership of different types of mHealth data (patient-generated health data, health records, app or device-produced data, etc.).

Codify mHealth data rights and ownership

The identified rights and ownership should be codified in legislation and policy in alignment with current national (regional or global) data protection regulation frameworks. These should include definitions of ownership, for example: mHealth data are owned by the individual, community providing the data, healthcare providers. They also should incorporate related rights such as the right to control the use of data, decline participation in data collection, withdraw data from a system, and to obtain benefit.

mHealth data ownership implies that individuals have a right to know, determine, and control how their data are used, and to benefit equitably from such data. The right to access data is different from owning that data, which may vary according to mHealth data types and the linked stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities.

Extend data rights and ownership to products and services

The identified mHealth data rights and ownership model should be extended to related products and services. For example, the secondary use of data in research also should not cause harm to individuals or communities.25,26 Similarly, individual and community ownership over their data extend to the right to equitable benefit-sharing from the products and services built from their contributed data. Services built from the data might include artificial intelligence (AI) products or reselling personal data for profit by a third party.

Guiding example

The EU GDPR stimulated a global discussion about data privacy and protection and specified how organizations must deal with personal identified data. Currently, many jurisdictions are moving towards GDPR-compatible regimes. The GDPR identifies principles relating to the processing of personal data: (1) lawfulness, fairness, and transparency, (2) purpose limitation, (3) data minimization, (4) accuracy, (5) storage limitations, (6) integrity and confidentiality, (7) accountability, (8) international transfer. The GDPR rights of the data subject are: (1) right to be informed, (2) right of access, (3) right to rectification, (4) right to object to processing, (5) right to object automated decision-making, (6) right to be forgotten, (7) right to data portability, (8) right to restrict processing.

Tiffin et al20 provided a practical checklist for implementing digital data governance principles derived from their experiences working with digital health data in LMICs. They examined four key domains: ethics and informed consent, data access, sustainability, and legal framework.

Objective 2: protect people through building trust (patients’ perspective on mHealth data)

Building trust in data systems and practices requires the codevelopment of mHealth governance systems in a participatory and transparent manner with individuals and communities.27,28 The covering regulations and guidelines should be accessible, understood, and followed in practice to build trust. Trust requires safeguarding data, ensuring privacy, and establishing transparent and inclusive data collection, processing, storage, analysis, use, sharing, and disposal processes.

Key patient concerns relate to data privacy and security and how researchers and companies will use their data,29 which may prevent patients from sharing their data. Willingness to share data is impacted by the degree of trust in the entity and its policies, as well as concerns about downstream use of the data. In LMICs, data mishandling or reidentification could stigmatize communities or populations.30

Establish transparent and accessible processes and systems

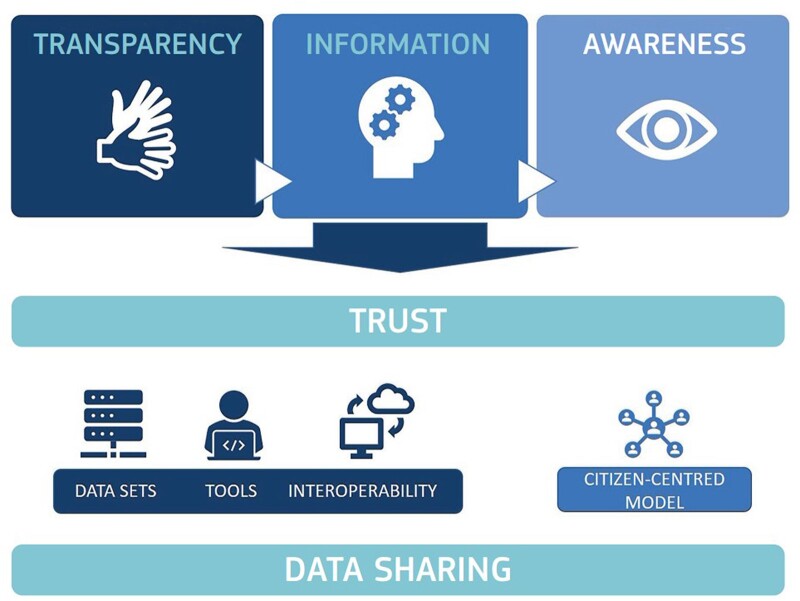

Transparency in mHealth data governance is required to create buy-in from stakeholders, particularly patients, around data processes. The Data Futures Partnership in New Zealand31 defines transparent data use with three dimensions: value, protection, and choice (Figure 2). Accordingly, stakeholders can understand how and why data are collected (value); how data are stored, analyzed, and used (protection); and how the systems and processes that support data governance operate (choice).

Figure 2.

Transparent data use dial (Source: Data Futures Partnership in New Zealand).31

Guiding example

The Digital Health Europe project32 introduced a framework for citizen-controlled data sharing to motivate citizens to share their own data (Figure 3).33 On the policy level, the framework addresses transparency, information, awareness, and trust-building. Technically, it focuses on datasets, tools, and interoperability. LMICs could leverage a similar individual-controlled data sharing model to facilitate trust and mutual reciprocity.

Figure 3.

Framework for citizen-controlled data sharing (Source: Digital Health Europe project).33

Objective 3: promote health value through enhancing systems and services (health system’s perspective on mHealth data)

mHealth data governance can enable meaningful use of data to enhance health system efficiency and resilience. Data can actively contribute to the transformation of health systems into value-based systems.34 Embedding these principles in LMIC environments can facilitate the development of equitable and efficient health systems.

Evaluate the benefits of mHealth data

The secondary use of mHealth data in medical research and policymaking has demonstrated the potential to advance medical sciences, public health services, and healthcare innovation,35–37 especially when AI tools are used to analyze the information.38–40 Consequently, stakeholders legitimately require appropriate, secure access to data. Citizens who contribute data must also understand how their data may contribute to research and development.

Guiding example

Kalkman et al41 conducted a systematic review of the principles and norms governing responsible data sharing in international health research. They identified four themes (societal benefits and value; distribution of risks, benefits, and burdens; respect for individuals and groups; and public trust and engagement) under which relevant principles and norms are grouped (Table 2). This work could lead to development of a harmonized governance framework for data sharing in health research.

Table 2.

Themes and principles for responsible health data sharing (adapted—Source: Kalkman et al41)

| Main themes | Norms and principles |

|---|---|

| Societal benefits and value | Accessibility, Data quality, Sustainability, Scientific progress/value, Promote health and well-being, Interoperability, Scientific validity, Societal benefit, Duty to share, Collaboration and capacity building, Health-related public interest, Improved clinical care, Enhance healthcare decision-making, Social value, Individual benefit, Improve public health, Efficiency. |

| Distribution of risks, benefits and burdens | Benefit-sharing, Reciprocity, Risk-benefit evaluation, Equity and fairness, Protection of intellectual property, Attribution, Proportionality, Ownership, Recognition and attribution. |

| Respect for individuals and groups | Respect/protect privacy, Protect confidentiality, Ensure data security, Respect individuals, Respect individual rights, Individual autonomy, Respect dignity of individuals, Respect (the dignity of) communities, Prevent discrimination, Legal compliance, Protect life, health and well-being, Respect families, Respect welfare of individuals. |

| Public trust and engagement | Transparency, Accountability, Engagement/participation, Maintain public trust, Maintain integrity, Responsibility, Professionalism, Health democracy, Solidarity. |

Promote data sharing and interoperability

Interoperability initiatives have demonstrated secure mHealth data sharing between systems.42,43 Concepts like data portability, open data, community data, data trustees, and data exchanges could also be considered part of the data sharing and interoperability mechanism.

Knudsen highlighted the following five principles to achieve better data interoperability44:

Principle 1: Healthcare providers need access to data beyond silos.

Principle 2: Healthcare providers need rich data interoperability.

Principle 3: Healthcare providers need real-time, actionable insights.

Principle 4: Respond to challenges with automated workflows.

Principle 5: Data must be shared using industry standards, such as HL7 Fast Health Interoperability Resources (FHIR®).

Recently, the FHIR for FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) implementation guide was introduced to provide guidance on how HL7 FHIR can be used for supporting FAIR health data implementation and assessment.45 However, data interoperability currently applies primarily to data collected originally by health systems and needs to be extended to mHealth data collected through apps and devices.

Facilitate innovation using mHealth data

mHealth tools can provide novel and real-time data into clinical care,46 although large-scale successes remain elusive.47 With these datasets, AI and big data analytics can be applied, leading to new tools, innovative healthcare services, and health insights at individual and population levels. This requires developing a governance environment that can enable innovation and effectively support the application of new digital technologies, as well as new kinds of data uses.

Guiding report

The WHO recently published guidance on the ethics and governance of AI in health.48 The report identified six core principles to mitigate ethical challenges and risks: (1) protect autonomy; (2) promote human well-being, human safety, and the public interest; (3) ensure transparency, explainability, and intelligibility; (4) foster responsibility and accountability; (5) ensure inclusiveness and equity; (6) promote AI that is responsive and sustainable.

CONCLUSION

mHealth has demonstrated strong potential to advance medicine, healthcare services, and innovation globally. As the volume of mHealth devices continues to grow and new data streams emerge, global stakeholder engagement is needed to implement and maintain mHealth data governance in LMICs. The Health Data Governance Principles provide a base for harmonizing and creating data governance strategies internationally. Leveraging this framework, we identified relevant objectives for mHealth data protection, sharing, and interoperability. To realize these objectives, collaborative participation from patients, communities, health systems, and governments is essential for improving global health equity and outcomes.

FUNDING

This perspective received no specific grant from any public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agency. ACG is currently supported by a VA Advanced Fellowship in Medical Informatics. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs or those of the United States Government. AP is supported by Funding Award No. T15 LM007079.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

RH wrote the first draft of the manuscript. ACG, AP, and JO made substantial edits and contributions and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank other members of the Patient Contributed Data group (sponsored by the HL7 Patient Empowerment workgroup) for their valuable comments and fruitful discussions.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

Contributor Information

Rada Hussein, Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Digital Health and Prevention, Salzburg, Austria.

Ashley C Griffin, Department of Health Policy, VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California, USA.

Adrienne Pichon, Department of Biomedical Informatics, Columbia University, New York, New York, USA.

Jan Oldenburg, Participatory Health Consulting, LLC, Richmond, Virginia, USA.

DATA AVAILABILITY

No new data were generated or analyzed in the context of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1. Giansanti D. The role of the mHealth in the fight against the Covid-19: successes and failures. Healthcare (Basel) 2021; 9 (1): 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Asadzadeh A, Kalankesh LR.. A scope of mobile health solutions in COVID-19 pandemics. Inform Med Unlocked 2021; 23: 100558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Executive Board 142. mHealth: Use of Appropriate Digital Technologies for Public Health: Report by the Director-General. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274134. Accessed May 11, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 4. McCool J, Dobson R, Whittaker R, Paton C.. Mobile health (mHealth) in low- and middle-income countries. Annu Rev Public Health 2022; 43 (1): 525–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Labrique AB, Wadhwani C, Williams KA, et al. Best practices in scaling digital health in low and middle income countries. Glob Health 2018; 14 (1): 103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Novillo-Ortiz D, De Fátima Marin H, Saigí-Rubió F.. The role of digital health in supporting the achievement of the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Int J Med Inform 2018; 114: 106–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Asi YM, Williams C.. The role of digital health in making progress toward sustainable development goal (SDG) 3 in conflict-affected populations. Int J Med Inform 2018; 114: 114–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hussein R. A review of realizing the universal health coverage (UHC) goals by 2030: part 2—what is the role of eHealth and technology? J Med Syst 2015; 39 (7): 72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Giansanti D. The Italian fight against the COVID-19 pandemic in the second phase: the renewed opportunity of telemedicine. Telemed e-Health 2020; 26 (11): 1328–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kickbusch I, Piselli D, Agrawal A, et al. The Lancet and Financial Times Commission on governing health futures 2030: growing up in a digital world. Lancet 2021; 398 (10312): 1727–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ITU News. Ghana launches COVID-19 tracker app. Geneva: International Telecommunication Union (ITU); May 14, 2020. https://www.itu.int/hub/2020/05/ghana-launches-covid-19-tracker-app/. Accessed May 11, 2022.

- 12. Obaid R. Saudi Health Ministry launches app to help monitor COVID-19 patients. Jeddah: Arab News. Saudi Research & Publishing Company; April 8, 2020. https://arab.news/zr3a5. Accessed May 11, 2022.

- 13. Thiagarajan K. An Indian state tells quarantined folks: “a selfie an hour will keep the police away.” Washington, DC: National Public Radio (NPR); April 12, 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/04/12/828843214/an-indian-state-tells-quarantined-folks-a-selfie-an-hour-will-keep-the-police-aw. Accessed May 11, 2022.

- 14. McKinsey & Company. Unlocking Digital Healthcare in Lower- and Middle-Income Countries. San Francisco: McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/unlocking-digital-healthcare-in-lower-and-middle-income-countries. Accessed May 11, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mason C, Lazenby S, Stuhldreher R, Kimball M, Bartlein R.. Lessons learned from implementing digital health tools to address COVID-19 in LMICs. Front Public Health 2022; 10: 859941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Verhagen LM, R de G, Lawrence CA, Taljaard J, Cotton MF, Rabie H.. COVID-19 response in low- and middle-income countries: don’t overlook the role of mobile phone communication. Int J Infect Dis 2020; 99: 334–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Data Protection and Privacy Legislation Worldwide. Geneva: The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). https://unctad.org/page/data-protection-and-privacy-legislation-worldwide. Accessed May 11, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cummins N, Schuller BW.. Five crucial challenges in digital health. Front Digit Health 2020; 2: 536203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Winter JS, Davidson EJ.. Harmonizing Regulatory Spheres to Overcome Challenges for Governance of Patient-Generated Health Data in the Age of Artificial Intelligence and Big Data. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network; 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3749529. Accessed May 12, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tiffin N, George A, LeFevre AE.. How to use relevant data for maximal benefit with minimal risk: digital health data governance to protect vulnerable populations in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health 2019; 4 (2): e001395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Digital Health 2020–2025. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Transform Health. Health Data Governance Principles: Universalizing the benefits of health digitalization. Geneva: Transform Health; 2022. License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tsosie KS, Claw KG, Garrison NA.. Considering “respect for sovereignty” beyond the Belmont report and the common rule: ethical and legal implications for American Indian and Alaska native peoples. Am J Bioeth 2021; 21 (10): 27–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)—Official Legal Text. General data protection regulation (GDPR). https://gdpr-info.eu/. Accessed May 11, 2022.

- 25. Tripathy JP. Secondary data analysis: ethical issues and challenges. Iran J Public Health 2013; 42 (12): 1478–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mello MM, Wolf LE.. The Havasupai Indian tribe case—lessons for research involving stored biologic samples. N Engl J Med 2010; 363 (3): 204–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Akhlaq A, McKinstry B, Muhammad KB, Sheikh A.. Barriers and facilitators to health information exchange in low- and middle-income country settings: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan 2016; 31 (9): 1310–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gagnon MP, Ngangue P, Payne-Gagnon J, Desmartis M.. m-Health adoption by healthcare professionals: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2016; 23 (1): 212–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cortez A, Hsii P, Mitchell E, Riehl V, Smith P.. Conceptualizing a Data Infrastructure for the Capture, Use, and Sharing of Patient-Generated Health Data in Care Delivery and Research through 2024. Washington, DC: The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC). Accenture Federal Services; 2018. https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/onc_pghd_final_white_paper.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Parker M. Ethical sharing of health research data in low- and middle-income countries: views of research stakeholders. Public Health Research Data Forum. 2014. https://wellcome.org/what-we-do/our-work/public-health-research-data-forum. https://cms.wellcome.org/sites/default/files/ethical-sharing-of-health-research-data-in-low-and-middle-income-countries-phrdf-2014.pdf. Accessed May 11, 2022.

- 31. Bhunia P. Data Futures Partnership in New Zealand issues guidelines for organisations to develop social license for data use. OpenGov Asia. 2017. https://opengovasia.com/data-futures-partnership-in-new-zealand-issues-guidelines-for-organisations-to-develop-social-license-for-data-use/. Accessed May 11, 2022.

- 32.DigitalHealthEurope consortium. DigitalHealthEurope Project. Empowering citizens and building a healthier society through digital health. https://digitalhealtheurope.eu/. Accessed May 12, 2022.

- 33. Consultation paper: citizen-controlled health data sharing governance—DigitalHealthEurope. https://digitalhealtheurope.eu/results-and-publications/consultation-paper-citizen-controlled-health-data-sharing-governance/. Accessed May 11, 2022.

- 34. Lavallee DC, Lee JR, Austin E, et al. mHealth and patient generated health data: stakeholder perspectives on opportunities and barriers for transforming healthcare. Mhealth 2020; 6: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hsueh P-Y, Cheung Y-K, Dey S, et al. Added value from secondary use of person generated health data in consumer health informatics. Yearb Med Inform 2017; 26 (1): 160–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Velmovitsky PE, Bevilacqua T, Alencar P, Cowan D, Morita PP.. Convergence of precision medicine and public health into precision public health: toward a big data perspective. Front Public Health 2021; 9: 561873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schmitz H, Howe CL, Armstrong DG, Subbian V.. Leveraging mobile health applications for biomedical research and citizen science: a scoping review. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2018; 25 (12): 1685–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bohr A, Memarzadeh K. The rise of artificial intelligence in healthcare applications. In: Bohr A, Memarzadeh K, eds. Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press;2020: 25–60. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Khan ZF, Alotaibi SR.. Applications of artificial intelligence and big data analytics in m-Health: a healthcare system perspective. J Healthc Eng 2020; 2020: 8894694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dullabh P, Sandberg SF, Heaney-Huls K, et al. Challenges and opportunities for advancing patient-centered clinical decision support: findings from a horizon scan. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2022; 29 (7): 1233–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kalkman S, Mostert M, Gerlinger C, van Delden JJM, vanThiel GJMW.. Responsible data sharing in international health research: a systematic review of principles and norms. BMC Med Ethics 2019; 20 (1): 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zeng B, Bove R, Carini S, et al. Standardized integration of person-generated data into routine clinical care. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2022; 10 (2): e31048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vaidyam A, Halamka J, Torous J.. Enabling research and clinical use of patient-generated health data (the mindLAMP Platform): digital phenotyping study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2022; 10 (1): e30557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Knudsen J. Guiding Principles for Better Data Interoperability in Healthcare. Chicago, IL: Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS); 2021. https://www.himss.org/resources/guiding-principles-better-data-interoperability-healthcare. Accessed May 11, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 45. FHIR for FAIR—FHIR Implementation Guide—FHIR v4.3.0-snapshot1. http://build.fhir.org/ig/HL7/fhir-for-fair/. Accessed May 11, 2022.

- 46. Demiris G, Iribarren SJ, Sward K, Lee S, Yang R.. Patient generated health data use in clinical practice: a systematic review. Nurs Outlook 2019; 67 (4): 311–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tiase VL, Hull W, McFarland MM, et al. Patient-generated health data and electronic health record integration: a scoping review. JAMIA Open 2020; 3 (4): 619–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.World Health Organization. Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence for Health: WHO Guidance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated or analyzed in the context of this article.