Abstract

Background/Aims

Enteroenteric intussusception in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (EI-PJS) is traditionally treated by surgery. However, enteroscopic treatment is a minimally invasive approach worth attempting. We aimed to develop a risk scoring system to facilitate decision-making in the treatment of EI-PJS.

Methods

This was a single-center case-control study, including 80 patients diagnosed with PJS and coexisting intussusception between January 2015 and January 2021 in Air Force Medical Center. We performed logistic regression analysis to identify independent risk factors and allocated different points to each subcategory of risk factors; the total score of individuals ranged from 0 to 9 points. Then, we constructed a risk stratification system based on the possibility of requiring surgery 0–3 points for “low-risk,” 4–6 points for “moderate-risk,” and 7–9 points for “high-risk.”

Results

Sixty-one patients (76.25%) were successfully treated with enteroscopy. Sixteen patients (20.0%) failed enteroscopic treatment and subsequently underwent surgery, and three patients (3.75%) received surgery directly. Abdominal pain, the diameter of the responsible polyp, and the length of intussusception were independent risk factors for predicting the possibility of requiring surgery. According to the risk scoring system, the incidence rates of surgery were 4.44% in the low-risk tier, 30.43% in the moderate-risk tier, and 83.33% in the high-risk tier. From low- to high-risk tiers, the trend of increasing risk was significant (p<0.001).

Conclusions

We developed a risk scoring system based on abdominal pain, diameter of the responsible polyps, and length of intussusception. It can preoperatively stratify patients according to the risk of requiring surgery for EI-PJS to facilitate treatment decision-making.

Keywords: Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Intussusception, Double-balloon enteroscopy, Risk assessment

INTRODUCTION

Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) is a rare hereditary polyposis syndrome characterized by multiple gastrointestinal polyps, mucocutaneous pigmentations, and predisposition towards malignancy. Polyps located in the small intestine can dramatically increase the risk of enteroenteric intussusception (EI), with a cumulative risk of 50% at the age of 20.1 As one of the most dreadful complications of PJS, intussusception may lead to intestinal ischemia and occasionally require urgent surgical treatment. Traditionally, the most used treatment for enteroenteric intussusception in PJS (EI-PJS) was surgery. With the advance of therapeutic enteroscopy, it is now possible to remove the lead point and reduce the intussusception with enteroscopy. This minimally invasive treatment has great advantages in avoiding abdominal incisions or postoperative adhesions and maintaining the integrity of the gastrointestinal tract. However, the enteroscopic approach is not suitable for all patients. Without risk stratification, the abuse of this treatment may be futile or even dangerous. Therefore, an important point before the treatment decision-making is to correctly distinguish patients who might be successfully treated by enteroscopy from those who require surgery. Unfortunately, due to the low incidence of EI-PJS, reported literature in this field so far are mostly case reports2-4 and there are almost no specialized cohort studies, which hampered the recommendation on the treatment of EI-PJS.5-7 Thus, we performed this retrospective case-control study to explore the independent risk factors impacting the treatment approach and develop a risk scoring system to facilitate the treatment decision-making for patients with EI-PJS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients and groups

We reviewed patients diagnosed with PJS and EI at Air Force Medical Center from January 2015 to January 2021. Medical records and image data were collected regarding the demographic data, family history, surgical history, abdominal pain, white blood cell count, hemoglobin concentration, characteristics of polyps, and intussusceptions, as well as surgical operation and/or enteroscopic treatment results. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients were diagnosed with PJS (according to the clinical diagnostic criteria proposed by Beggs et al.8) and coexisted EI (according to radiologist's diagnosis based on typical computed tomography [CT] scan finding9); (2) patients older than 14 years. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the clinical data was incomplete; (2) patients underwent surgery due to cancer. Patients who received only enteroscopic treatment were regarded as enteroscopy group. In this group, the eliminations of polyps were executed through enteroscopic snare polypectomy, and the reductions of intussusceptions were achieved by withdrawal of enteroscopy and over-tube. Patients who eventually received surgical treatment (irrespective of whether they have undergone enteroscopic attempt or not) were regarded as surgery group. The Ethics Committee of Air Force Medical Center approved the study (approval number: 2021-101-PJ01) and the informed consent was waived.

2. Data collection

Abdominal pain was assessed using the verbal rating scale, which was divided into no pain, mild pain, moderate pain, and severe pain.10 To simplify the statistical analysis, we used a binary scale to classify the degree of abdominal pain.

The maximum diameter of the polyp at the tip of intussusception (responsible polyp) was measured directly on the CT scan. The length of intussusception was measured along the long axis of the intestinal on contiguous sections. If the intussusception was oriented in a craniocaudal direction, length was calculated by observing the number of images on which the target pattern appearance was evident; if the intussusception was oriented horizontally, the length of the abnormal segment of intestine was measured directly; if the intussusception was oriented obliquely, the length was measured by a combination of this techniques.11 If there were multiple intussusceptions in a single patient, we only recorded the maximum length for statistical analysis.

3. Statistical analysis

Quantitative data with normality were described by mean and standard deviation and compared using the two independent samples t-test, and non-normal quantitative data were expressed by median and interquartile range and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Ordered categorical data were also compared using the Mann-Whitney U test, and unordered categorical data were compared using the chi-square test.

Risk factors with p-value <0.10 in the univariate analysis were used for multivariate analysis. Risk factors with p-value <0.05 in the multivariate analysis were used to establish a logistic regression equation. We attributed 0 points as a reference and allocated different points to each subcategory of risk factors based on the regression coefficient (β). With the total score (sum of each subcategory corresponding points of risk factors), we built a risk stratification including low-risk tier, moderate-risk tier, and high-risk tier. The risk stratification was assessed by the trend for risks with a linear-by-linear association test. A p-value <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant and two-tailed tests were used. Statistical calculations were generated using IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

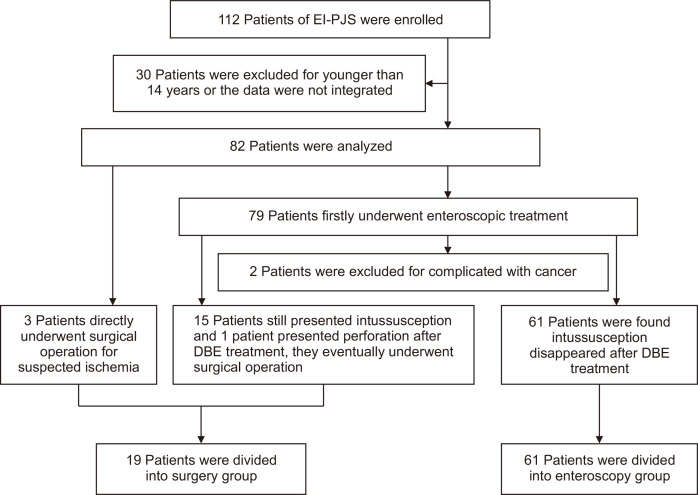

One hundred twelve patients were collected. Thirty of them were excluded due to being under 14 years of age or incomplete data. Of those included patients, three cases were directly operated on due to acute abdomen. The initial treatment of the other 79 cases was double balloon-assisted enteroscopy (EN450P5 or EN450T5 or EN580T; Fujifilm Inc., Tokyo, Japan), but two of them were excluded because they were confirmed to have cancer by enteroscopic biopsy and subsequently underwent surgery. Among the remaining 77 cases, 15 patients failed the reductions of intussusceptions and one patient had perforation after enteroscopic treatment. Those 16 patients subsequently received surgery. As a result, a total of 80 patients were analyzed, and there were 19 cases and 61 cases in surgery group and enteroscopy group, respectively. The flowchart of population selection and grouping was shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for population selection and grouping.

EI-PJS, enteroenteric intussusception in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome; DBE, double-balloon enteroscopy.

Of 80 patients, 50 cases (62.5%) were male. The median age was 24 years (interquartile range, 18 to 31 years), ranging from 15 to 50 years. Thirty cases (37.5%) were positive with family history. Thirty-five cases (43.75%) were positive with abdominal surgical history. Twenty-five cases (31.25%) had initiative hospitalizations for enteroscopic polypectomy before the diagnosis of EI-PJS, of which seven cases were hospitalized more than 3 times. The number of cases who presented with no pain, mild pain, moderate pain, and severe pain were 34, 26, 17, and 3, respectively. The mean white blood cell count was 5.88±2.42 ×109/L. The mean hemoglobin concentration was 101.67±22.79 g/L, 61.25% of patients presented with anemia (hemoglobin <110 g/L). The median number of polyps was 8.5 (interquartile range, 4 to 12). The average diameter of responsible polyps was 4.70±1.14 cm, ranging from 2.5 cm to 7.2 cm. The median length of intussusception was 8.6 cm (interquartile range, 6.6 to 16.0 cm), ranging from 4.2 cm to 25.2 cm.

Of the 19 patients (23.75%) in surgery group, 10 cases underwent laparotomy and nine patients underwent laparoscopy, all patients recovered smoothly after surgery. Of the 61 patients (76.25%) in enteroscopy group, six cases (9.8%) experienced post-polypectomy syndrome, the clinical manifestations mainly included moderate abdominal pain, fever, vomiting, and hematochezia, and they were successfully treated by conservative management. When we compared the demographics and potential risk factors of the two groups, univariate analysis showed that there were statistically significant differences in abdominal pain, hemoglobin concentration, polyp diameter, intussusception length, and the number of intussusceptions. The detailed results are shown in Table 1. Subsequent multivariable analysis confirmed that abdominal pain, diameter of responsible polyp, and length of intussusception were independent risk factors impacting the treatment approach. The detailed results are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Comparison of the Demographics and Potential Risk Factors between the Surgery Group and Enteroscopy Group

| Characteristics | Surgery group (n=19) | Enteroscopy group (n=61) | t or Z or χ2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female/male) | 9/10 | 21/40 | 1.035* | 0.309 |

| Age, yr | 23 (19–31) | 24 (18–31) | –0.028† | 0.977 |

| Family history (positive/negative) | 8/11 | 22/39 | 0.225* | 0.635 |

| Abdominal operation history (positive/negative) | 8/11 | 27/34 | 0.027* | 0.869 |

| Abdominal pain (none or mild/moderate or severe) | 7/12 | 53/8 | –4.371† | <0.001 |

| White blood cell count, ×109/L | 6.40±3.20 | 5.72±2.13 | 1.070‡ | 0.288 |

| Hemoglobin concentration, g/L | 87.37±19.84 | 106.11±21.64 | 3.323‡ | 0.001 |

| Diameter of polyps, cm | 5.53±0.79 | 4.44±1.11 | –4.006‡ | <0.001 |

| No. of polyps | 10 (6–17) | 7 (3–10) | –1.826† | 0.068 |

| Length of intussusception, cm | 16.7 (13.5–20.4) | 8.3 (6.4–10.6) | –5.032† | <0.001 |

| No. of intussusceptions | 2 (1–3) | 1 (1–2) | –2.371† | 0.018 |

Data are presented as number, median (interquartile range), or mean±SD.

*Chi-square test (χ2); †Mann-Whitney test (Z); ‡Independent samples t-test (t).

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis of Risk Factors for Surgery in Patients with EI-PJS

| Risk factor | β | SE | p-value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None or mild abdominal pain | –2.851 | 0.943 | 0.003 | 0.058 (0.009–0.367) |

| Hemoglobin concentration | –0.035 | 0.023 | 0.132 | 0.966 (0.923–1.011) |

| Diameter of polyps | 1.342 | 0.563 | 0.017 | 3.829 (1.271–11.537) |

| No. of polyps | 0.033 | 0.034 | 0.339 | 1.033 (0.966–1.105) |

| Length of intussusception | 0.208 | 0.089 | 0.019 | 1.232 (1.034–1.467) |

| No. of intussusceptions | 0.149 | 0.460 | 0.745 | 1.161 (0.471–2.859) |

EI-PJS, enteroenteric intussusception in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome; β, regression coefficient; SE, standard error; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

With the regression coefficient, we constructed a regression equation to calculate the probability of individuals undergoing surgery (Supplementary Fig. 1). The –2 log-likelihood of this equation was 42.98, Cox-Snell and Nagelkerke R square were 0.428 and 0.643, respectively. With calculated probability >0.5 as a cutoff value, the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of this equation to predict EI-PJS patients need surgery were 0.7368, 0.9508, and 0.90, respectively.

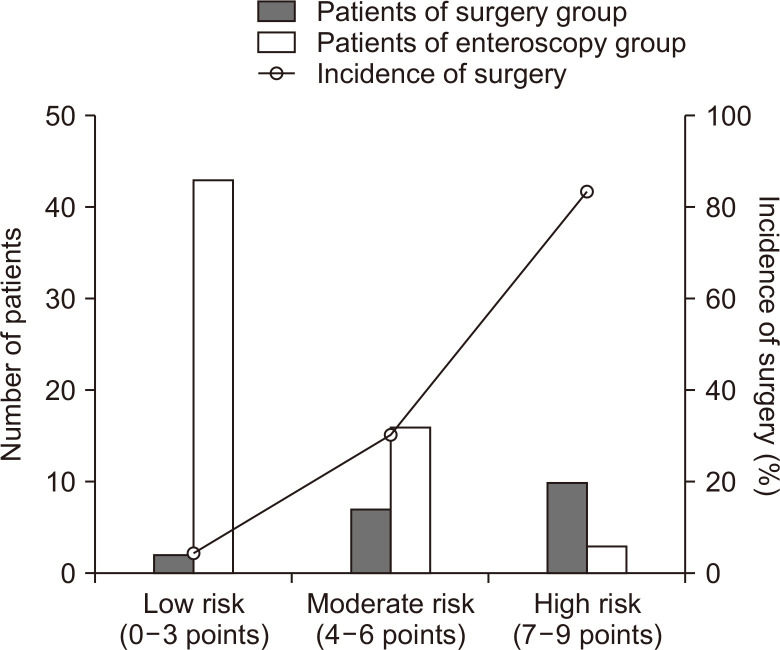

To simplify the preprocedural evaluation and facilitate clinical use, a risk scoring system composed of risk scoring rules and total score stratification was proposed. We developed risk scoring rules based on the regression coefficients and clinical practice experiences, as shown in Table 3. According to the rules, the total score of an EI-PJS patient was the sum of subcategory corresponding points of three risk factors, ranging from 0 to 9 points. The receiver operating characteristic curves of the total score and three independent risk factors were shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.89 (95% confidence interval, 0.819 to 0.968) for total score, 0.88 for length of intussusception, 0.78 for diameter of polyp, and 0.75 for abdominal pain, respectively. Based on the possibility of requiring surgery, the total score was stratified into three tiers: 0–3 points for “low-risk,” 4–6 points for “moderate-risk,” and 7–9 points for “high-risk.” According to the risk scoring system, of the 80 patients, 45 cases (56.25%), 23 cases (28.75%), and 12 cases (15.0%) were in the low-risk tier, moderate-risk tier, and high-risk tier, respectively. The incidences of surgery in low-risk tier, moderate-risk tier, and high-risk tier were 4.44%, 30.43%, and 83.33%, respectively. We observed a trend of significantly increased risk from low- to high-risk tiers (linear trend χ2=31.52, p<0.001, linear-by-linear association test), the results were shown in Fig. 2.

Table 3.

Risk Scoring Rule for Patients with EI-PJS

| Risk factor | Subcategories | Point |

|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | None or mild | 0 |

| Moderate or severe | 2 | |

| Length of intussusception | <8 cm | 0 |

| 8–16 cm | 1 | |

| >16 cm | 3 | |

| Diameter of polyps | <4 cm | 0 |

| 4–6 cm | 2 | |

| >6 cm | 4 |

EI-PJS, enteroenteric intussusception in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

Fig. 2.

The incidence of surgery in each risk tier. The proportions of low-risk, moderate-risk, and high-risk cases were 56.25%, 28.75%, and 15%, respectively. The rates of required surgery in low-risk tier, moderate-risk tier, and high-risk tier were 4.44%, 30.43%, and 83.33%, respectively. The risk of requiring surgery was significantly increased from the low- to high-risk tier (linear trend χ2=31.52, p<0.001, linear-by-linear association test).

DISCUSSION

Intussusception is defined as the invagination of a segment of intestine into an adjacent segment. Most adult intussusceptions are traditionally believed to have an identifiable cause, mainly including benign and malignant tumors.12 Currently, surgery is still the mainstay of treatment, particularly for intussusception with a lead point,13 because this feature is not only accompanied by the high incidence of malignant tumors, but also the potential risk of acute abdomen.14 However, surgery may not be the best option for most patients with EI-PJS. Notwithstanding that we had reported the malignant predisposition of PJS,15 the EI-PJS was mainly caused by benign hamartomatous polyps. As high as 97.6% (80/82) of responsible polyps of intussusception were benign in our study, while the proportion was 99.2% (119/120) in another study.1 Moreover, if we can remove the polyps and reduce the intussusceptions through the enteroscopic approach, it can also obviate the potential risk of acute abdomen. Therefore, EI-PJS is not a contraindication for enteroscopy.

According to our results, the enteroscopic approach had a high success rate in the treatment of EI-PJS, particularly in patients with low-risk features. Historically, Ohmiya et al.16 described the treatment of small intestinal polyps in PJS with double balloon-assisted enteroscopy in 2005. With the advancement of enteroscopic skills, pioneers in this field have performed enteroscopic polypectomy safely and effectively.17 Even in patients with intussusception, there were reports of successful enteroscopic treatment. For example, van Lier et al.1 reported that six cases of EI-PJS that were successfully treated by enteroscopy with polyp removal in 2010. Then Sakamoto et al.18 reported that five of six patients with EI-PJS successfully received double balloon-assisted enteroscopy treatment. Compared with surgery, the enteroscopic treatment is more minimally invasive and has an edge on avoiding intestine loss, postoperative adhesions, and abdominal scar. Besides, this minimally invasive treatment can be repeated, which is very important for PJS patients, because as polyps continue to grow, they may face repeated treatments. Considering the advantages of the enteroscopic treatment, after obtaining patients' informed consent, we were more inclined to this minimally invasive therapy when facing EI-PJS. Fortunately, most of our choices were right, and the prognoses of patients in our study were gratifying. Meanwhile, we must notice that enteroscopic treatment is not suitable for all patients. On the contrary, if we apply this approach indiscriminately, it may be futile or even dangerous. Therefore, elucidating the risk factors and stratifying the risk of requiring surgery are necessary for the treatment decision of EI-PJS.

Abdominal pain is the most common clinical manifestation of intussusception, accounting for 54.5% to 73% of patients.13,19,20 In our study, 60 cases (75%) experienced none or mild abdominal pain. This was inconsistent with a reported article, in which 80% presented with acute abdomen.1 This discrepancy may be ascribed to the fact that as every adult PJS patient in our department underwent CT scan to evaluate the gastrointestinal polyps, more incidental intussusceptions were diagnosed.13 Seventeen cases presented with moderate abdominal pain, but nine of them failed the enteroscopic treatment and eventually received surgery. Thus, doctors should remain vigilant when facing such symptoms. Patients with suspected enteric ischemia should receive surgical treatment.6 Those patients are usually characterized by continuous severe abdominal pain, sometimes accompanied by fever, leukocytosis, or hematochezia, and are not suitable for enteroscopic therapy.

The diameter of responsible polyp is another risk factor that affects the enteroscopic treatment. First, huge polyps are prone to cause tamponade of enteric cavity and make the polyp pedicle poorly exposed, which is particularly common in polyps larger than 6 cm. In clinical practice, we only snare the lesions with a clear vision of polyp pedicle, because in the situation of intussusception, if we blindly perform the polypectomy, the intestinal wall is easily entangled in the snare and lead to perforation. Second, huge polyps are more often nourished by thick arteries hidden in thick stalks, which will increase the bleeding risk. The huge polyps with a limited operating view or thick stalks were deemed unsuitable for safe enteroscopic polypectomy and were subsequently referred for surgery. For some huge polyps evaluated as treatable by enteroscopy, we usually performed the endoscopic mucosal resection to remove the polyps. If the polyp was too large to be fully captured with a snare, we performed piecemeal polypectomy. During this process, we usually employ the force coagulation model more frequently to reduce the risk of bleeding.

The length of intussusception was reported as a feature to distinguish self-limiting intussusception from these requiring surgery.11,13,21 Most authors argued that intussusceptions ≥5 cm in length should be treated with surgery. These studies did not consider the enteroscopic treatment as an alternative. Reviewing the average length of intussusception of “surgical cases” in these reports, we can find that they were similar to the length of intussusception of enteroscopy group (8.8 cm11 or 9.6 cm21 vs 8.3 cm). While the intussusceptions indeed requiring surgery in our study were those with a median length of 16.7 cm. Therefore, we can speculate that patients who were recommended for surgery based on length of intussusception may have an opportunity for enteroscopic treatment.

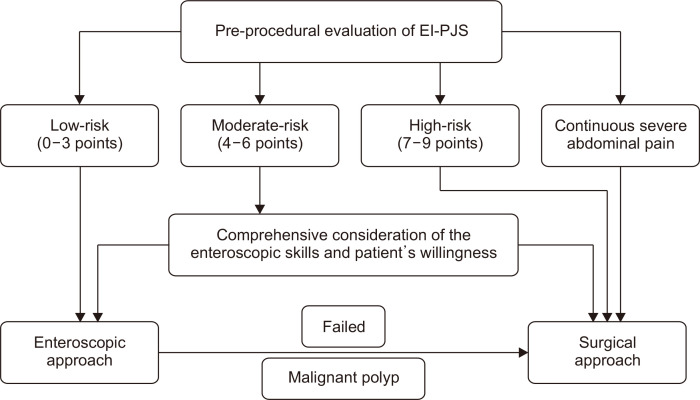

The risk scoring system based on abdominal pain, diameter of polyp, and length of intussusception are friendly to clinical use. First, the parameters are easily obtained, provided that a preprocedural CT scan is performed. This examination was a mandatory item for adults in our department for it can provide basic information about polyps and intussusceptions of PJS. Although the radiation exposure time for a single CT examination is relatively short, we cannot ignore the cumulative effect of radiation for patients with PJS who may undergo CT examination frequently. The magnetic resonance enterography may be an alternative worth researching though it is more expensive.22 Second, the risk scoring system is concise and intuitive, containing only three risk factors, and the subcategories of each risk factor are distinguishable. Third, the risk scoring system can accurately stratify the risk for requiring surgery and then facilitate tailoring the intervention. Based on the risk scoring system, we also proposed a decision-making algorithm of the treatment in EI-PJS (Fig. 3). For patients at low-risk tier (0–3 points), the failure rate of enteroscopic treatment was very low (4.44%). Considering the advantages of this minimally invasive treatment, it should be the first choice. When the enteroscopic treatment failed or encountered malignant polyps, surgery should be considered; For patients at moderate-risk tier (4–6 points), there was a moderate failure rate (30.43%). Thus, an individualized decision after comprehensive consideration of the enteroscopic skills and patient’s willingness is necessary. Endoscopists with extensive enteroscopic treatment experience can try this minimally invasive approach after thoroughly evaluating the conditions, meanwhile, it is recommended to arrange a backup surgery in case the enteroscopic treatment fails. For patients at high-risk tier (7–9 points) or patients with continuous severe abdominal pain, surgical treatment should be given priority, because enteroscopic treatment may be futile (with a failure rate of 83.33%) or even dangerous.

Fig. 3.

Decision-making algorithm regarding the treatment in patients with enteroenteric intussusception in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (EI-PJS).

It was worth noting that the proportion of low-risk patients in our study was the highest (56.3%), this result may be attributed to that some patients have had enteroscopic polypectomy before presenting intussusception. Furthermore, regular surveillance with enteroscopic polypectomy can dramatically decrease the incidence of intussusception in PJS.17,18,23 Hopefully, through effective monitoring and minimally invasive treatment, PJS patients can be free from surgery due to intussusception in the future.

There are some limitations of our study. First, limited by the retrospective database, we used the verbal rating scale to classify abdominal pain, which was a relatively crude scale compared to the other pain scales.10 Besides, only three patients with continuous severe pain were enrolled, and they were statistically classified into the “moderate and severe pain” subcategory. This may weaken the characteristic of this symptom as an indication for surgery. Second, the “length of intussusception” was not strictly defined before. We adopted the measurement method proposed by Lvoff et al.11 Even though this method was widely accepted by later researchers, the measurements of intussusception length were relatively vague rather than precise. Moreover, the length of the intestinal tract involved in intussusception is about 3 times the “length of intussusception.” However, these did not shift its capacity of predicting the difficulty of enteroscopic treatment. Third, this was a single-center retrospective study, which shared the disadvantage of this design with potential selection bias, and due to the rare incidence of EI-PJS, the sample size was small. A prospective, multicenter study is needed to validate the risk scoring system in the future.

In conclusion, we have developed a risk scoring system for EI-PJS based on abdominal pain, diameter of polyps, and length of intussusception, which can stratify the risk of requiring surgery and facilitate the therapy decision-making. Patients with low-risk features can choose minimally invasive enteroscopic treatment as the first-line therapy.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary materials can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.5009/gnl210390.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Study concept and design: N.X. Data acquisition: N.X., T.Z. Data analysis and interpretation: N.X., T.Z. Drafting of the manuscript: N.X. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: N.X., S.N. Statistical analysis: N.X. Administrative, technical, or material support; study supervision: Jing Z, Jinlong Z, H.L., S.N. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.van Lier MG, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Wagner A, van Leerdam ME, Kuipers EJ. High cumulative risk of intussusception in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: time to update surveillance guidelines? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:940–945. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sengupta S, Bose S. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:472. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm1806623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miura Y, Yamamoto H, Sunada K, et al. Reduction of ileoileal intussusception by using double-balloon endoscopy in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:658–659. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.AlSamman MA, Ferreira JD, Moustafa A, Moveson J, Akerman P. Successful endoscopic reduction of an ileocolonic intussusception in an adult with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gastroenterology Res. 2019;12:40–42. doi: 10.14740/gr1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Latchford A, Cohen S, Auth M, et al. Management of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome in children and adolescents: a position paper from the ESPGHAN Polyposis Working Group. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019;68:442–452. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000002248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wagner A, Aretz S, Auranen A, et al. The management of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: European Hereditary Tumour Group (EHTG) Guideline. J Clin Med. 2021;10:473. doi: 10.3390/jcm10030473.07c4edfe88294aad98beb1c582260f29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Leerdam ME, Roos VH, van Hooft JE, et al. Endoscopic management of polyposis syndromes: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2019;51:877–895. doi: 10.1055/a-0965-0605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975–986. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.198499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gayer G, Zissin R, Apter S, Papa M, Hertz M. Adult intussusception: a CT diagnosis. Br J Radiol. 2002;75:185–190. doi: 10.1259/bjr.75.890.750185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, et al. Studies comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:1073–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lvoff N, Breiman RS, Coakley FV, Lu Y, Warren RS. Distinguishing features of self-limiting adult small-bowel intussusception identified at CT. Radiology. 2003;227:68–72. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2272020455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barussaud M, Regenet N, Briennon X, et al. Clinical spectrum and surgical approach of adult intussusceptions: a multicentric study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:834–839. doi: 10.1007/s00384-005-0789-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onkendi EO, Grotz TE, Murray JA, Donohue JH. Adult intussusception in the last 25 years of modern imaging: is surgery still indicated? J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1699–1705. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1609-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong KD, Kim J, Ji W, Wexner SD. Adult intussusception: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23:315–324. doi: 10.1007/s10151-019-01980-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen HY, Jin XW, Li BR, et al. Cancer risk in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a retrospective cohort study of 336 cases. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317705131. doi: 10.1177/1010428317705131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohmiya N, Taguchi A, Shirai K, et al. Endoscopic resection of Peutz-Jeghers polyps throughout the small intestine at double-balloon enteroscopy without laparotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:140–147. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)02457-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao H, van Lier MG, Poley JW, Kuipers EJ, van Leerdam ME, Mensink PB. Endoscopic therapy of small-bowel polyps by double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:768–773. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sakamoto H, Yamamoto H, Hayashi Y, et al. Nonsurgical management of small-bowel polyps in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome with extensive polypectomy by using double-balloon endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:328–333. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Honjo H, Mike M, Kusanagi H, Kano N. Adult intussusception: a retrospective review. World J Surg. 2015;39:134–138. doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2759-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Somma F, Faggian A, Serra N, et al. Bowel intussusceptions in adults: the role of imaging. Radiol Med. 2015;120:105–117. doi: 10.1007/s11547-014-0454-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duc VT, Chien PC, Huyen L, et al. Differentiation between surgical and nonsurgical intussusception: a diagnostic model using multi-detector computed tomography. Acta Inform Med. 2021;29:32–37. doi: 10.5455/aim.2021.29.32-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goverde A, Korsse SE, Wagner A, et al. Small-bowel surveillance in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: comparing magnetic resonance enteroclysis and double balloon enteroscopy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:e27–e33. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cortegoso Valdivia P, Rondonotti E, Pennazio M. Safety and efficacy of an enteroscopy-based approach in reducing the polyp burden in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: experience from a tertiary referral center. Ther Adv Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;13:2631774520919369. doi: 10.1177/2631774520919369.771b938e1f8e499da27944590b12487a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.