Abstract

Background and purpose

False-positive radioiodine uptake can sometimes be observed with post-radioiodine treatment (RIT) whole body scanning. Radioiodine pitfall has often been reported as being caused by benign or inflammatory disease, or, in some cases, by tumor lesions. This paper reviews the possible causes of such false-positive imaging, and suggests possible reasons for suspecting these pitfalls.

Methods and results

Online databases, including MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, ISI Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Scopus, were systematically examined, using different keyword combinations: “radioiodine false-positive imaging”, “131 I false-positive imaging” and “ RAI false-positive imaging”. An illustrative case was described. Excluding cases in which SPECT/CT was not performed, a total of 18 papers was found: 17 case reports and one series regarding false-positive iodine—131 uptake after RIT.

Conclusions

The prevalence of radioiodine pitfall was significantly reduced through the use of SPECT/CT imaging, though its possible presence has always to be taken into account. Inflammation, passive iodine accumulation, other tumors, and, sometimes, unknown causes can all potentially generate false-positive imaging. Missing detection of false-positive imaging could result in over-staging and inappropriate RIT or it could lead to the non-detection of other cancers. We examine the reasons for these possible pitfalls.

Keywords: Differentiated thyroid cancer, False-positive radioiodine, False-positive, 131-I, SPECT-CT, Sodium iodine symporter

Introduction

Radioiodine treatment (RIT) after Total Thyroidectomy (TT) for Differentiated Thyroid Cancer (DTC) can be used as an adjuvant therapy [1, 2], and in selected cases, RIT can take on the role of the ablation of remnant thyroid tissue [2–4]. RIT also has a very important diagnostic role in post-therapy whole body scintigraphy (pT-WBS), with or without Single Photon Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography (SPECT/CT) (i.e., hybrid imaging) [4–7]. Both normal and tumorous thyroid cells, though the latter to a lesser extent, have a particular ability to uptake and organify iodine. Sodium Iodine Symporter (NIS) represents the key plasma membrane protein, transporting iodine inside the cell, while a further, complex enzymatic mechanism enables the organification of iodine and its storage, binding it to thyroglobulin and thyroid hormones.

In addition to thyroid cells, NIS can be expressed in several tissues [8], i.e., the salivary glands, which are usually easily visible in pT-WBS. Radioiodine uptake can also be physiologically observed via different mechanisms, in several other tissues/organs (e.g., liver, stomach) and, finally, in the bladder, where radiolabelled urine temporally stagnates before excretion [9–12].

Apart from these well-known areas in which radioiodine can be physiologically observed, the pT-WBS normally shows thyroid remnants and, if present, foci of metastatic disease. However, “false-positive” radioiodine uptake (i.e., radioiodine pitfall) can sometimes be seen in planar imaging, pT-WBS and/or focused static images, due to benign or inflammatory disease, as well as some tumor lesions [13].

SPECT-CT can be used as a complement to planar imaging in order to improve diagnostic performance, especially specificity, and its use has significantly reduced the radioiodine pitfalls [14–16].

It is of paramount importance to exclude or confirm radioiodine uptake as a false-positive in order to carry out more appropriate clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic management of DTC patients. In fact, missing the detection of false-positive imaging could result in over-staging and inappropriate RIT or could lead to the non-detection of other cancers.

In this paper, we describe a paradigmatic clinical case and present a narrative revision of the literature on false-positive radioiodine findings and potential causes.

Materials and methods

Illustrative case

A 48-year-old male underwent a total thyroidectomy for a thyroid nodule (23 mm maximum size) detected in the left lobe, and Thy 5 at fine needle cytology (FNC). From his history, the patient had had asymptomatic SARS-Cov-2 infection one month prior to surgical intervention, but presented no other important pathological disease and no previous lung disease.

At histopathological analysis, a unifocal papillary thyroid cancer (PTC) (20 mm in size), classic and tall cell (30%) variant, was diagnosed (pT1bNx). At 45 days following surgical intervention, neck ultrasonography showed minimal bilateral thyroid remnants, with absence of suspicious/pathological loco-regional lymph-nodes. At that date, basal thyroglobulin (Tg), with low thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) (<0.24 µIU/ml), was 1.10 ng /ml, and the anti-Tg antibodies were negative (i.e., <15 mU/ml). RIT was performed for ablative purposes, using an empiric activity (1110 MBq) after preparation with recombinant human TSH (rh-TSH) administration. Before rh-TSH stimulation, Tg was undetectable (<0.15), with TSH suppressed (<0.01 µIU/ml). A pT-WBS with SPECT-CT imaging was obtained five days after RIT, using a double-headed gamma camera equipped with low-energy high-resolution (LEHR) collimators.

A slight radioiodine uptake in a small thyroid remnant was noted, while an intense radioiodine uptake was detected in the lower lobe of the right lung, corresponding to a sub-pleural mass due to the confluence of nodular lesions with fibrotic streaks and traction bronchiectasis. The lesion was associated with emphysema bubbles, and was confirmed some days later with a focused CT scan obtained with and without contrast medium administration.

The patient underwent 18FDG-PET/CT (297 MBq), which demonstrated abnormal uptake of the metabolic tracer in the lesion (SUV max 6.6; MTV 1.5 ml). After consultation, the thoracic surgeon preferred to perform a surgical excision of the mass due to the risks related to biopsy in such emphysema bubbles. Histology showed a nodular area with cystic dilatations of alveolar spaces, with wide abscessualization and phlogistic infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages with several gigantocellular granulomas. The phlogistic infiltration involved the wall of contiguous bronchioles and lung parenchyma with fibroblastic proliferation.

Literature review

Online databases, including MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, ISI Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Scopus, were systematically examined using the following keyword combinations: “radioiodine false-positive imaging”, “131 I false-positive imaging” and “RAI false-positive imaging”. Because the diagnostic performance of pT-WBS can be significantly improved using SPECT/CT imaging, among the cases and series reported in the literature, we only included those cases in which SPECT/CT was performed, thereby excluding works reporting only planar imaging.

Results

Overall, the literature showed 145 case reports and two series regarding false-positive 131 uptake after RIT

For the reasons stated above, we excluded 129 papers, considering only those in which SPECT/CT was performed. A total of 18 papers were thus included: 1 series [17] and 17 case reports [18–34]. The series reported 23 cases of false-positive results: 15 in the chest, six in the pelvis, one in the cranium, and one in the abdomen. Overall, 20 cases regarded radioiodine uptake in the chest: 11 in the lung (mainly inflammatory), four on the chest bones or on soft tissue due to inflammation/trauma, one in the thymus, one mesenchymal tumor and the rest in not well-characterized sites [17–21, 34]. A total of 15 cases regarded uptake in the abdomen/pelvis: six in the kidney (cysts), five in the ovary (teratoma, benign cysts and malignant disease), two in the uterus and the others in not well-characterized sites [22–29]. Three cases reported uptake in the head: two surgical clips, and one on one eye [30, 31, 33]. A few other cases were in other sites [24, 32]. In many cases, accumulation of radioiodine and the cause was simply classified as “undetermined”.

Discussion

Our case, which we briefly report here, highlights the main points arising from the literature.

In our case, the concern regarding a possible pitfall was raised by the inappropriate value of Tg in the absence of serum anti-Tg antibodies in such a large lung metastasis.

On the other hand, the SPECT/CT and classical diagnostic imaging were not helpful in the final diagnosis. This false-positive case thus shows both similarities and differences compared to other papers in the literature.

In most cases, SPECT/CT together with other classical diagnostic imaging tools were able to assist in making a diagnosis. For example, the explanation for the false-positive was easily arrived at not only through SPECT/CT, but also due to the patient’s personal history. Two cases were due to post-surgical metallic clips, one case was due to a breast implant, and one case was due to recent scarring caused by the transareolar approach employed for the thyroidectomy [21, 34]. In many cases, accumulation of radioiodine was found in anatomic lesions without there being any apparent reasonable explanation, and the cause was simply classified as “undetermined”. However in all cases, diagnosis was possible by SPECT/CT and other imaging techniques. In four cases [17, 22–24], all were in the pelvis, diagnosis was virtually impossible, and surgery had to be performed to clarify the histology. Table 1 reports the possible causes of false-positive imaging, possible sites in SPECT/CT, and possible actions for reaching a diagnosis.

Table 1.

Possible sites, cause of false-positive iodine accumulation and actions

| SITES | Cause | Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Chest | bronchiectasis, pulmonary scleroderma, spindle cell mesenchymal tumor, thymus, bone cysts, vertebral hemangioma, infections, soft tissue inflammations, aortic calcification, indeterminate | CTs, biopsy in selected cases (surgery) |

| Abdomen/pelvis | duodenal diverticulum, renal cyst, polycystic kidney, renal follicular cyst, ovarian cyst, ovarian adenocarcinoma, uterine menstruation dermoid cyst, pelvic endometriosis, renal hamartoma, indeterminate | CTs,MRI (surgery) |

| Head | surgical clips, eye | History, MRI, |

| Other | spermatocele, indeterminate | clinical examination |

CTs Computerized Tomography Scan, MRI Magnetic Resonance Imaging, US Ultrasonography

In almost all cases, as in our reported case, Tg values were either suppressed or low for a metastatic disease. However, Tg was elevated in one case, where pulmonary metastasis coexisted with a false-positive near scapular soft tissue upon chest imaging, due to a mesenchymal tumor [15]. In the latter report [15], the unusual site was a reason for suspecting a pitfall. Of course, the coexistence of metastasis and false-positive imaging could be a most embarrassing situation. The unusual site of the imaging, as reported above, and/or the inappropriate correlation between the burden of the metastasis and the serum Tg values as an inadequate response to RIT, could be a reason for suspecting a false-positive. In one case, Tg levels were high, which then decreased after surgical asportation of an ovarian cyst [22], and surprisingly, the same authors raised concerns regarding the true nature of the ovarian cyst.

The causes for such false-positive findings do not always have a simple explanation. The expression of NIS can be the underlying cause of some radioiodine uptake, and, in fact, NIS can be normally expressed in a number of tissues. More specifically, it can be expressed in salivary glands, in the basolateral membrane of breast ductal epithelium during lactation (and rarely in fibroadenomas), in gastric mucin-producing cells and in the apical surface of enterocytes, in the lacrimal sac and nasolacrimal duct, and in the placenta, where it mediates transport from maternal blood circulation to fetal blood circulation.

Using more sensitive detection methods, NIS expression has also been detected in the pituitary gland, pancreas, testis, prostate, ovary, heart, thymus, and lung. It is therefore not surprising that in some particular conditions or in some particular diseases, at these levels NIS can play a role in abnormal radioiodine concentration and accumulation.

However, in many cases the reason for radioiodine accumulation in some organs or sites cannot be explained by NIS physiological overexpression, and other possible causes need to be considered, such as: (1) passive accumulation of radioiodine in body fluids and in phlogistic tissues; (2) ectopic NIS expression or high vasculature in non-thyroid tumors; (3) contamination (although this can usually be easily detected). From a practical point of view, a careful review of a patient’s history together with a clinical examination could prevent expensive diagnostic tools in certain cases. In our own case, the possible role of SARS-Cov 2 infection and the possibility of an asymptomatic pneumonia remain an unresolved issue. A recent Covid 19 infection could be a point to consider when some doubt exists regarding radioiodine accumulation at SPECT/CT.

Conclusions

False-positive imaging should be considered in order to prevent over-staging of the tumor and, especially, possible over-treatment involving radioiodine. Moreover, false-positive imaging can be due to another kind of tumor, whose diagnosis should not be missed and which would require completely different treatment.

Overall, an examination of the literature, together with our own case, provide practical suggestions in suspecting and overcoming false-positive radioiodine findings.

A discordant result between the serum Tg and the presence and size of the lesion is a first reason for such a suspicion. In a DTC, especially in the initial phase of its natural history, a grossly metastatic disease with a low or undetectable Tg in the absence of anti-Tg antibodies is highly unlikely. Another reason for suspicion could be an unusual site for a metastasis according to the DTC histotype, and, more generally, a very unusual site in itself for a metastasis, above all if the history shows some pathological/traumatic events in that area. Table 1 reports possible diagnostic actions.

In our experience, the SPECT/CT parameters used in our patient (see Fig. 1 caption) could be generally adopted in clinical practice to improve the diagnostic performance of the imaging. However, note that technical parameters (both for SPECT and CT) should always be personalized to the anthropometric features of each patient.

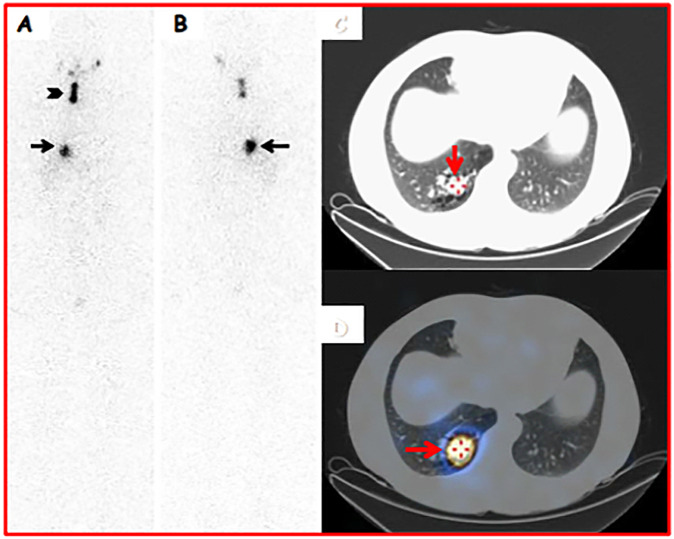

Fig. 1.

A 48-year-old male underwent a total thyroidectomy for a thyroid nodule (23 mm maximum size) detected in the left lobe, and Thy 5 at fine needle cytology (FNC). Histology was conclusive for Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma (classical and tall cell variant) in a small-sized nodule (23 mm) located in the left lobe (pT1bNxMx). An ablative 131I therapy (1110 MBq) was performed after rh-TSH stimulation (0.9 mg/day for two consecutive days). 131I-pT-WBS was acquired in anterior (A) and posterior (B) views from head to distal thighs (magnification: 1×; matrix: 1024*256; acquisition time: 10 cm/s). The study was obtained 9 days after RIT. An area of radioiodine uptake (black arrowhead) was noted in the right thyroid bed (consistent with a thyroid remnant). In addition, a well-defined and quite intense radioiodine uptake was observed in the lower part of the right thoracic region (consistent with lung metastasis) (black arrows). Axial-CT (B) (acquisition parameters: tube 120 kVp voltage, 80–210 mA tube current, 2.5 mm helical thickness, table speed of 37 mm/s, table feed per rotation of 18.75 mm/rot, tube rotation time of 0.8 seconds, and 0.938:1 pitch) and SPECT-CT (C and D) imaging (acquisition parameters: step-and-shoot acquisition mode [40 sec/step, 6° angle, 30 steps/detector]) demonstrated abnormal radioiodine uptake in a solid and sub-pleural mass with irregular border located in the lower lobe of the right lung (consistent with lung metastasis) (red arrows)

Additional imaging studies, such as a CT scan, MRI or, in selected cases, 18F-FDG-PET/CT, represent the natural follow-up for reaching a diagnosis. However, in many cases, a biopsy is required, and in certain cases surgery might be needed to clarify the histology of an unknown lesion.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, et al. 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: The American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2016;26:1–133. doi: 10.1089/thy.2015.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pacini F, Fuhrer D, Elisei R, Handkiewicz-Junak D, Leboulleux S, Luster M, Schlumberger M, Smit JW. 2022 ETA Consensus Statement: What are the indications for post-surgical radioiodine therapy in differentiated thyroid cancer? Eur. Thyroid J. 2022;11(1):e210046. doi: 10.1530/ETJ-21-0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuttle RM, Ahuja S, Avram AM, Bernet VJ, Bourguet P, Daniels GH, et al. Controversies, Consensus, and Collaboration in the Use of 131 I Therapy in Differentiated Thyroid Cancer: A Joint Statement from the American Thyroid Association, the European Association of Nuclear Medicine, the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, and the European Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2019;29:461–470. doi: 10.1089/thy.2018.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campennì A, Barbaro D, Guzzo M, Capocetti F, Giovannella L. Personalized management of differentiated thyroid cancer in real life - practical guidance from a multidisciplinary panel of experts. Endocrine. 2020;70:280–291. doi: 10.1007/s12020-020-02418-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campennì A, Giovanella L, Pignata SA, Violi MA, Siracusa M, Alibrandi A, Moleti M, Amato E, Ruggeri RM, Vermiglio F, Baldari S. Nucl Med Commun. Thyroid remnant ablation in differentiated thyroid cancer: searching for the most effective radioiodine activity and stimulation strategy in a real-life scenario. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2015;36(11):1100–1106. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giovannella L, Deandreis D, Vrachimis A, Campennì A, Petranovic Ovcaricek P. Molecular imaging and theragnostics of thyroid cancers. Cancers. 2022;14(5):1272. doi: 10.3390/cancers14051272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorenzoni A, Capozza A, Seregni E, Giovanella L. Nuclear Medicine Theranostics: Between Atoms and Patients in Nuclear Medicine Therapy. Springer Nature Switzerland AG. 2019;1:10. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jhiang SM, Sipos JA. Na+/I− symporter expression, function, and regulation in non-thyroidal tissues and impact on thyroid cancer therapy. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2021;28(10):T167–T177. doi: 10.1530/ERC-21-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campennì A, Amato E, Laudicella R, Alibrandi A, Cardile D, Pignata SA, Trimarchi F, Ruggeri RM, Auditore L, Baldari S. Recombinant human thyrotropin (rhTSH) versus Levo-thyroxine withdrawal in radioiodine therapy of differentiated thyroid cancer patients: differences in abdominal absorbed dose. Endocrine. 2019;65(1):132–137. doi: 10.1007/s12020-019-01897-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryan J, Curran CE, Hennessy E, Newell J, Morris JC, Kerin MJ, Dwyer RM. The sodium iodide symporter (NIS) and potential regulators in normal, benign and malignant human breast tissue. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(1):e16023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang CC, Lin YH, Kittipayak S, Hwua YS, Wang SY, Pan LK. Biokinetic model of radioiodine I-131 in nine thyroid cancer patients subjected to in-vivo gamma camera scanning: A simplified five-compartmental model. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(5):e0232480. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castro G, Berrocal I, Carmona J, González J, González P. ¹³¹I gastric uptake with and without omeprazole in patients undergoing radioiodine therapy for differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2012;39(8):1356–1357. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2104-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Triggiani V, Giagulli VA, Iovino M, De Pergola G, Licchelli B, Varraso A, Dicembrino F, Valle G, Guastamacchia E. False positive diagnosis on (131)iodine whole-body scintigraphy of differentiated thyroid cancers. Endocrine. 2016;53(3):626–635. doi: 10.1007/s12020-015-0750-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chudgar AV, Shah JC. Pictorial review of false-positive results on radioiodine scintigrams of patients with differentiated thyroid cancer. Radiographics. 2017;37:298–315. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017160074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aide N, Heutte N, Rame JP, Rousseau E, Loiseau C, Henry-Amar M, Bardet S. Clinical relevance of single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography of the neck and thorax in postablation 131I scintigraphy for thyroid cancer. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;94:2075–2084. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Avram AM. Radioiodine scintigraphy with SPECT/CT: an important diagnostic tool for thyroid cancer staging and risk stratification. J. Nucl. Med. 2012;53:754–764. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.104133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oral A, Yazici B, Eraslan C, Burak Z. Unexpected false-positive I-131 uptake in patients with differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Mol. Imaging Radionucl. Ther. 2018;27:99–106. doi: 10.4274/mirt.37450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yano E, Nakajo M, Jinguji M, Tani A, Kitazono I, Yoshiura T. I-131 false-positive uptake in a thymic cyst with expression of the sodium- iodide symporter: A case report. Medicine. 2022;101(26):e29282. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000029282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Posocco D, Kamat B, Dadparvar S. False-positive 123I-uptake mimics metastatic lung disease in a patient with interstitial lung disease secondary to sleroderma. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2022;47(1):79–80. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000003825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang F, Cao L, Zhang C. An unusual false-positive uptake of radioiodine caused by pulmonary vasculature: the usefulness of SPECT/CT. Hell J. Nucl. Med. 2020;23:204–205. doi: 10.1967/s002449912110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Jiang L, Xu Y, Zhang X, Liu B. An Unusual False-Positive Uptake of Radioiodine Caused by Breast Implants. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2022;47:646–647. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000004165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu T, Zhao X, Xu H. False-positive radioiodine uptake in simple ovarian cyst in a DTC patient: a case report. Front. Oncol. 2021;31(11):665135. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.665135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohammadzadeh Kosari H, Zakavi SR, Barashki S, Roustaei Firouzabad H, Ataei Nakhaei S, Aryana K. Incidental finding of a dermoid cyst in a whole-body iodine scan: importance of using (131)SPECT/CT in the differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Nucl. Med. Rev. Cent. East Eur. 2021;24:106–107. doi: 10.5603/NMR.2021.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sallem A, Msakni I, Elajmi W, Hammami H. Pitfall of I-131 whole body scan: a mucinous adenocarcinoma of the ovary. Pan. Afr. Med. J. 2020;8(36):72. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.36.72.21507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu L, Chen Y, Tian T, Huang R, Liu B. Physiologic uterine uptake of radioiodine during menstruation demonstrated by SPECT/CT. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2019;44:975–977. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000002754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hannoush ZC, Palacios JD, Kuker RA, Casula S. False Positive Findings on I-131 WBS and SPECT/CT in Patients with History of Thyroid Cancer: Case Series. Case. Rep. Endocrinol. 2017;2017:8568347. doi: 10.1155/2017/8568347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang R, Zhou K, Fan Q, Chen H, Fan C. A false-positive I-131 finding of duodenum diverticulum in thyroid cancer evaluation by SPECT/CT: a case report. Medicine. 2018;97(8):e99997. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maciejewski A, Czepczynski R, Ruchala M. False-positive radioiodine whole-body scan due to a renal cyst. Endokrynol. Pol. 2018;69:736–739. doi: 10.5603/EP.a2018.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mi YX, Sui X, Huang JM, Wei LG, Xie P. Incidentally polycystic kidney disease identified by SPECT/CT with post-therapy radioiodine scintigraphy in a patient with differentiated thyroid carcinoma: a case report. Medicine. 2017;96(43):e8348. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu L, Chen Y, Tian T, Huang R, Liu B. An unusual false-positve uptake of radioiodine caused by metallic implants. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2019;44(8):e495–e496. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000002587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh JP, Sims JB, Iranpour P. False-positive radioiodine uptake from an intracranial surgical clip. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2022;47(3):e279–e280. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000004002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Filizoğlu N, Öksüzoğlu K, Özgüven S, Buğdaycı O, Erdil TY. Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction on 131I SPECT/CT: Atypical False-positive Paranasal Radioiodine Uptake as a Complication of Single-dose RAI Treatment. Mol. Imaging Radionucl. Ther. 2022;31(3):234–236. doi: 10.4274/mirt.galenos.2021.68926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han N, Zhang Y, Si Z, Wang X. Unexpected false-positive uptake of 131I on the right eye in a patient with differentiated thyroid cancer: a case description. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2022;12(8):4337–4340. doi: 10.21037/qims-22-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang A, Fu W, Deng Y, He L, Zhang W. False-Positive 131I Uptake After Transareola Endoscopic Thyroidectomy in a Patient With Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2022;47(4):324–325. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000004019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]