Abstract

Background

Deoxynivalenol (DON) is a widespread issue for feed and food safety, leading to animal and human health risks. The objective of this study was to determine whether ferroptosis is involved in DON-induced intestinal injury in piglets. Three groups of 21-day-old male weanling piglets (n = 7/group) were fed a control diet, or diet adding 1.0 or 3.0 mg DON/kg. At week 4, serum and small intestines were collected to assay for biochemistry, histology, redox status and ferroptosis-related genes expression. In addition, the involvement of ferroptosis and the role of FTL gene in DON-induced cell death were further verified in the IPEC-J2 cells.

Results

Compared to the control, dietary supplementation of DON at 1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg induced different degrees of damage in the duodenum, jejunum and ileum, and increased (P < 0.05) serum lipopolysaccharide concentration by 46.2%–51.4%. Dietary DON supplementation at 1.0 and (or) 3.0 mg/kg increased (P < 0.05) concentrations of malondialdehyde (17.4%–86.5%) and protein carbonyl by 33.1%–92.3% in the duodenum, jejunum and ileum. In addition, dietary supplemented with DON upregulated (P < 0.05) ferroptotic gene (DMT1) and anti-ferroptotic genes (FTL and FTH1), while downregulated (P < 0.05) anti-ferroptotic genes (FPN, FSP1 and CISD1) in the duodenum of the porcine. Furthermore, the in vitro study has demonstrated that deferiprone, a potent ferroptotic inhibitor, mitigated (P < 0.05) DON-induced cytotoxicity in porcine small intestinal IPEC-J2 cells. Additionally, deferiprone prevented or alleviated (P < 0.05) the dysregulation of ferroptosis-related genes (ACSL4 and FTL) by DON in IPEC-J2 cells. Moreover, specific siRNA knockdown FTL gene expression compromised the DON-induced cell death in IPEC-J2 cells.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study revealed that ferroptosis is involved in DON-induced intestinal damage in porcine, and sheds a new light on the toxicity of DON to piglets.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40104-023-00841-4.

Keywords: Deoxynivalenol, Ferroptosis, Intestine, Piglets, Toxicity

Introduction

Deoxynivalenol (DON), is a type B trichothecene largely generated by Fusarium graminearum and F. culmorum. DON is one of the most widespread mycotoxins contaminates in cereal, including wheat, barley, oats, millet and corn and their by-products [1–3]. Climate change and associated global warming is increasing crop susceptibility to fungal infection, which is further resulting in increased DON contamination of cereals [3]. It was reported that consumption of food and feed contaminated by DON leads to food refusal, emesis, diarrhea and impaired intestinal and immune function in humans and farm animals [4–6]. It also could be residual in the animal food as the secondary environmental pollution to endanger human health [6, 7]. Therefore, in view of the harmful effects of DON, its toxic mechanisms to animals have drawn great attention during the past decades [8].

DON is quickly and efficiently absorbed in the upper part of the small intestine, which is the primary target organ damaged by DON [9]. It is well documented that the intestinal toxicity of DON is associated with impairment of the intestinal structure, epithelial barrier, intestinal mucosal immunity and gut microbiota homeostasis [2, 10]. These DON-induced intestinal damages have been attributed primary to DON’s ability to binding to the eukaryotic 60S ribosomal subunit, blocking peptidyl transferase, and inhibiting translation, but concurrently activating mitogen-activated protein kinase via the “ribotoxic stress response” and inducing inflammation and apoptosis [11]. Also, generation of DON-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) can induce oxidative stress and apoptosis, which has been recognized as another outcome of DON toxicity [10, 12].

Unlike apoptosis, ferroptosis is a newly discovered form of iron-dependent and ROS-reliant cell death with characteristics of lipid peroxide accumulation, and cytological change, including reduced or vanished mitochondrial cristae, and ruptured and condensed mitochondrial membrane [13]. However, whether ferroptosis is involved in DON-induced intestinal damage remains unclear. Among animal species, pigs are highly susceptible to DON [14]. Thus, in this study, pigs were selected to determine whether or not DON-induced intestinal injury is associated with the regulation of ferroptosis signaling.

Materials and methods

Piglets, treatments, and sample collection

The animal protocol for this study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Huazhong Agricultural University, China. In total, 21 castrated male crossbred [(Duroc × Landrace) × Large White] weanling piglets (aged 3 weeks) were randomly allocated to 3 groups; each group was assigned to 7 pens of 1 piglet/pen. Piglets were allowed free access to water and a corn-soybean based diet (Control; Additional file 1: Table S1) formulated to meet the NRC nutritional requirements (NRC, 2012) [15], or the control diet spiked with 1.0 mg/kg DON or 3.0 mg/kg DON. Based on the Chinese hygiene standard of 1.0 mg/kg for DON in pig compound feed and since it has been reported that diet contaminated with 2.89 mg/kg DON decreased the performance and caused intestinal damage in piglets, we set the above doses of DON [16]. The DON was produced by the Fusarium graminearum strain W3008 and mixed into the pig feed as in our previous study [16]. The concentrations of DON, aflatoxin B1 and zearalenone in the feed were measured by specific assay kits (COKAS4000W, COKAQ8000 and COKAS5000W) from the Romer Labs, Singapore. The experiment lasted 28 d. At the end of the experiment, all pigs were humanely euthanized by intravenous injection of sodium pentobarbital (40 mg/kg BW) to harvest blood and intestine for either serology analysis or histology examination. Five-cm of mid-duodenum, mid-jejunum and mid-ileum were cut and washed with ice-cold saline, then divided into aliquots and collected in Eppendorf tubes that were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until use.

Histology, serum biochemistry and redox status analysis

The duodenum, jejunum, ileum tissues were microscopically examined after fixing in 10% neutral-buffered formalin and processing for paraffin embedding, sectioning at 5 μm, and then staining with hematoxylin and eosin [17]. The concentrations of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), malondialdehyde (MDA), protein carbonyl (PC) and reduced glutathione (GSH) and activity of diamine oxidase (DAO), superoxide dismutase (SOD), total antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) were measured by a colorimetric method with the use of specific assay kits (H255, A003-1-2, A087-1-2, A006-1-1, A088-1-1, A001-1-2 and A015-1-2) from the Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute of China. Protein concentration was measured by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Jiangsu, China).

Porcine IPEC-J2 cell culture and viability assay

The porcine IPEC-J2 cell line was cultured following the method as previously described [16]. Briefly, the cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 IU penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere, and medium was changed at 24 h intervals. For DON exposure, IPEC-J2 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate (1 × 104 cells/well) and incubated for 24 h, then, treated with DON (0–1000 μg/L; Additional file 2: Fig. S1A), or deferiprone (DFP, 10-80 μmol/L; Additional file 2: Fig. S1B) for 24 h to determine the 30% inhibitory concentration (IC30) of DON or the safety dose of DFP by measuring cells viability with the CCK-8 kit following the manufacturer’s instruction (Beyotime biotechnology, China). The determined IC30 of DON and safety dose of DFP were 500 μg/L and 20 μmol/L, respectively, which were used for the further analysis. 1) To verify whether ferroptosis involved in DON-induced cell death in IPEC-J2 cells, the cells were treated with normal cell cultural medium (control), control added with 500 μg/L DON (DON), or control added with 500 μg/L DON plus 20 μmol/L DFP (DON+DFP) for 24 h. Then, calcein acetoxymethyl ester (Calcein AM, Abcam, ab141420) were used for assaying the cells viability. The fluorescence intensity was observed and analyzed using fluorescence microscope and software Image J. 2) To verify whether ferritin light chain (FTL) involved in DON-mediated ferroptosis in IPEC-J2 cells, the cells were treated with negative control siRNA (NC), negative control siRNA plus 500 μg/L DON (NC+DON), 50 nmol/L FTL siRNA (siRNA), or 50 nmol/L FTL siRNA plus 500 μg/L DON (siRNA+DON). Briefly, the siRNA (Additional file 3: Table S2) was transfected to the cells with 0.2% Lipofectamin 2000 reagent (Invitrogen, Shanghai, China) treatment for 48 h incubation, then, 500 μg/L DON was added for 24 h treatment. Then, the cells viability was measured by CCK-8 kit as described above. The cells were also collected and stored at −80 °C until other assays.

Real-time q-PCR and western blot analyses

Real-time q-PCR analysis was conducted as previously described [5]. Briefly, total mRNA was extracted from the jejunum with Trizol (Invitrogen) following the instructions of the manufacturer. Primers for ferroptosis-related genes and the house keeping gene β-actin were designed using Primer Express 3.0 (Applied Biosystems) and are presented in Additional file 4: Table S3. The 2-ddCt method was used for the quantification of target genes, and the relative abundance of target genes was normalized to β-actin. Western blot analyses of the jejunum samples were performed as previously described [18], and the primary antibody used for each gene is presented in Additional file 5: Table S4. The concentration of protein was detected by the bicinchoninic acid assay (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Jiangsu, China).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS (version 13, Chicago, IL, USA). Data were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA with a significance level of P < 0.05, and the Tukey-Kramer method was used for multiple mean comparisons. Data are presented as means ± SD.

Results

Intestinal histology, serum biochemistry, and redox status

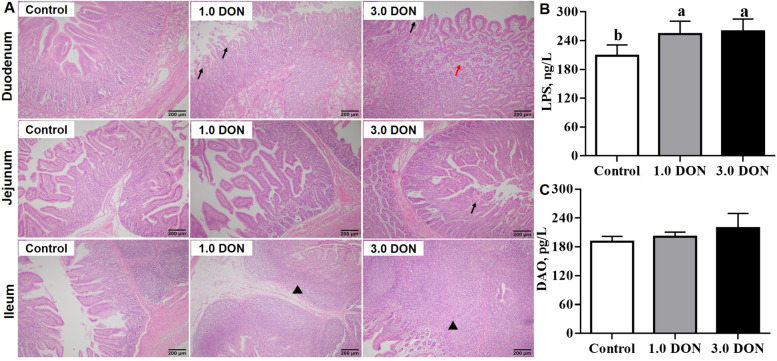

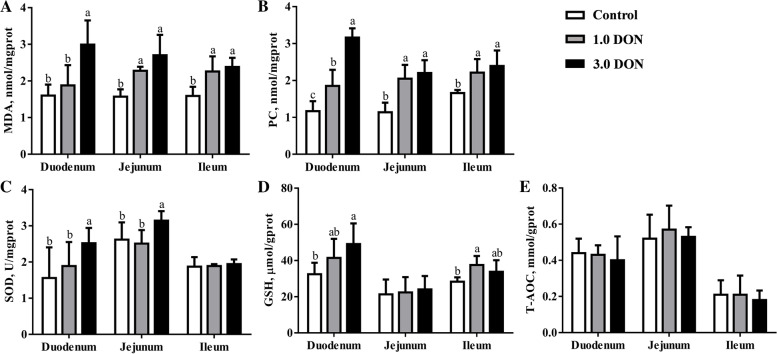

As shown in Fig. 1A, compared with the control, dietary supplementation of DON at 1.0 and (or) 3.0 mg/kg induced degeneration and necrosis of villous epithelium cell, and lamina propria edema in duodenum, degeneration and necrosis of villous epithelium cell in the jejunum, lymphocyte hyperplasia in ileum. Meanwhile, dietary supplementation of DON at 1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg increased (P < 0.05) the LPS concentration by 46.2% and 51.4% in the serum of piglets (Fig. 1B), while DON did not affect (P ≥ 0.05) the DAO activity in the serum (Fig. 1C). Compared with the control, dietary supplementation of DON at 1.0 mg/kg increased (P < 0.05) concentrations of MDA by 41.9% and 45.5% in the jejunum and ileum, while 3.0 mg/kg DON increased (P < 0.05) concentrations of MDA by 49.1%–86.5% in the duodenum, jejunum and ileum (Fig. 2A). In addition, dietary supplementation of DON at 1.0 increased (P < 0.05) concentrations of PC by 33.1%–79.8% and 3.0 mg/kg DON increased (P < 0.05) concentrations of PC by 43.9%–170.0% (Fig. 2B) in the duodenum, jejunum and ileum. Meanwhile, dietary supplementation of DON at 3.0 mg/kg increased (P < 0.05) SOD activity in the duodenum and jejunum by 19.8%–61.5% and dietary supplementation of DON at 1.0 mg/kg increased (P < 0.05) GSH concentration by 32.5% in the ileum (Fig. 2C and D). However, dietary supplementation of DON did not affect (P ≥ 0.05) the T-AOC in the intestinal samples (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 1.

Effects of DON on histology of intestine and serum biochemistry in weaned piglets. Histological sections of duodenum, jejunum and ileum (A). The content of LPS (B) and DAO (C) in serum. Values are expressed as means ± SD, n = 7. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin; photomicrographs are shown at 200× magnification. Black arrow indicates degeneration, necrosis and desquamation of villous epithelial cells; Black arrowhead indicates lymphocyte hyperplasia; Red arrow indicates lamina propria edema. Labeled means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05. LPS, lipopolysaccharid, DAO, diamine oxidase; Control, base diet; 1.0 DON, basal diet supplemented with 1.0 mg/kg DON; 3.0 DON, basal diet supplemented with 3.0 mg/kg DON

Fig. 2.

Effects of DON on redox status of intestine in weaned piglets. Values are expressed as means ± SD, n = 7. Labeled means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05. MDA, malondialdehyde; PC, protein carbonyl, SOD, superoxide dismutase; GSH, reduced glutathione; T-AOC, total antioxidant capacity; Control, base diet; 1.0 DON, basal diet supplemented with 1.0 mg/kg DON; 3.0 DON, basal diet supplemented with 3.0 mg/kg DON

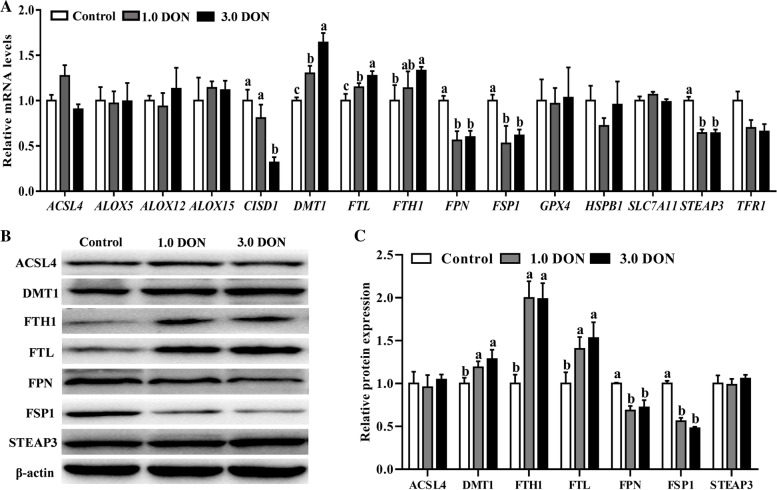

Expression of ferroptosis-related genes in duodenum

The expressions of 15 ferroptosis-related genes at mRNA and (or) protein levels in the duodenum are presented in Fig. 3. Specifically, both dietary supplementation of DON at 1.0 mg/kg and 3.0 mg/kg increased (P < 0.05) the mRNA levels of divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) and FTL and decreased (P < 0.05) ferroportin (FPN), ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) and six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3 (STEAP3). Notably, dietary supplementation of DON at 3.0 mg/kg also increased (P < 0.05) the mRNA levels of ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1) and decreased (P < 0.05) CDGSH iron sulfur domain 1 (CISD1) in the duodenum (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, dietary supplementation of DON at 1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg also increased (P < 0.05) DMT1, FTH1 and FTL and decreased (P < 0.05) FPN and FSP1 at protein levels in the duodenum (Fig. 3B and C). However, the expression of the rest of 8 genes was not significantly affected (P ≥ 0.05) by the DON supplementation in the duodenum of porcine (Fig. 3A–C).

Fig. 3.

Effects of DON on the expression of ferroptosis-related genes in duodenum. The relative mRNA abundance of ferroptosis-related genes in duodenum (A). Values are expressed as means ± SD, n = 7. A representative image (B) and the relative density (C) of protein bands of ferroptosis-related proteins in duodenum. Values are expressed as means ± SD, n = 3. Labeled means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05. Control, base diet; 1.0 DON, basal diet supplemented with 1.0 mg/kg DON; 3.0 DON, basal diet supplemented with 3.0 mg/kg DON. ACSL4, acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4; ALOX5, arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase; ALOX12, arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase, 12S type; ALOX15, arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase; CISD1, CDGSH iron sulfur domain 1; DMT1, divalent metal transporter 1; FTL, ferritin light chain; FPN, ferroportin; FTH1, ferritin heavy chain 1; FSP1, ferroptosis suppressor protein 1; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4; HSPB1, heat shock protein family B (small) member 1; SLC7A11, solute carrier family 7 member 11; STEAP3, six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3; TFR1, transferrin receptor

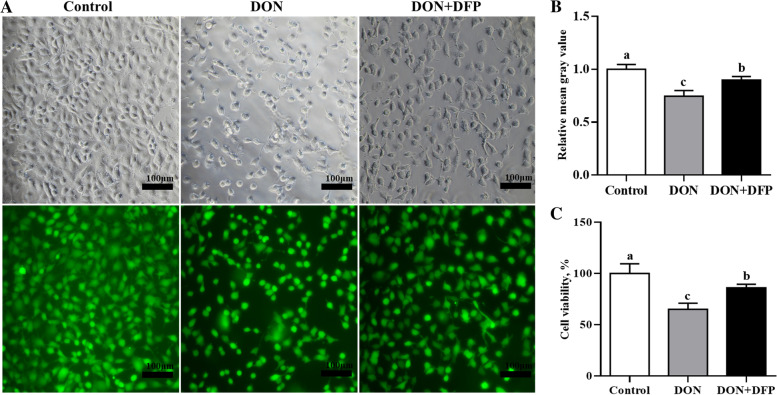

Verification of ferroptosis involvement in DON-induced cell death in IPEC-J2 cells

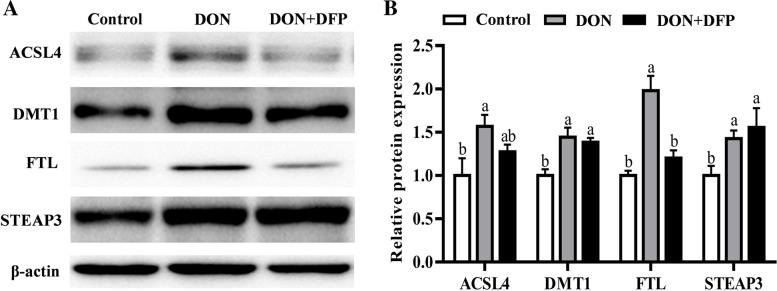

Compared with the control, DON supplementation reduced (P < 0.05) the IPEC-J2 cell viability (Fig. 4A–C) by 25.3% and 34.5%, as evidenced by the Calcein AM staining and CCK-8 analysis. Notably, DON-induced changes were alleviated (P < 0.05) by 15.1% and 20.5% in the IPEC-J2 cells by the supplementation with DFP (Fig. 4A–C). Furthermore, DON supplementation upregulated (P < 0.05) acyl-coenzyme A synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4), DMT1, FTL and STEAP3 protein productions compared with the control (Fig. 5A and B). Notably, changes of the ACSL4 and FTL protein productions observed in the DON group were attenuated (P < 0.05) in the DON+DFP group (Fig. 5A and B).

Fig. 4.

Effects of DON and DFP on IPEC-J2 cell viability. The cells viability was assayed by calcein acetoxymethyl ester (Calcein AM; A) and the values shows the fluorescence intensity was analyzed by Image J (B). Cell viability was analyzed by CCK-8 (C). Values are expressed as means ± SD, n =6. Labeled means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05. Control, cell culture medium; DON, cell culture medium+500 μg/L DON; DON+DFP, cell culture medium+500 μg/L DON+20 μmol/L DFP

Fig. 5.

Effects of DON and DFP on the expression of ferroptosis-related proteins in IPEC-J2. A representative image (A) and the relative density (B) of protein bands of ferroptosis-related proteins in IPEC-J2 cells. Values are expressed as means ± SD, n = 3. Labeled means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05. ACSL4, acyl-coenzyme A synthetase long-chain family member 4; DMT1, metal transporter 1; FTL, ferritin light chain; STEAP3, six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3. Control, cell culture medium; DON, cell culture medium+DON; DON+DFP, cell culture medium+ DON+DFP

Verification of the role of FTL involvement in DON-mediated ferroptosis in IPEC-J2 cells

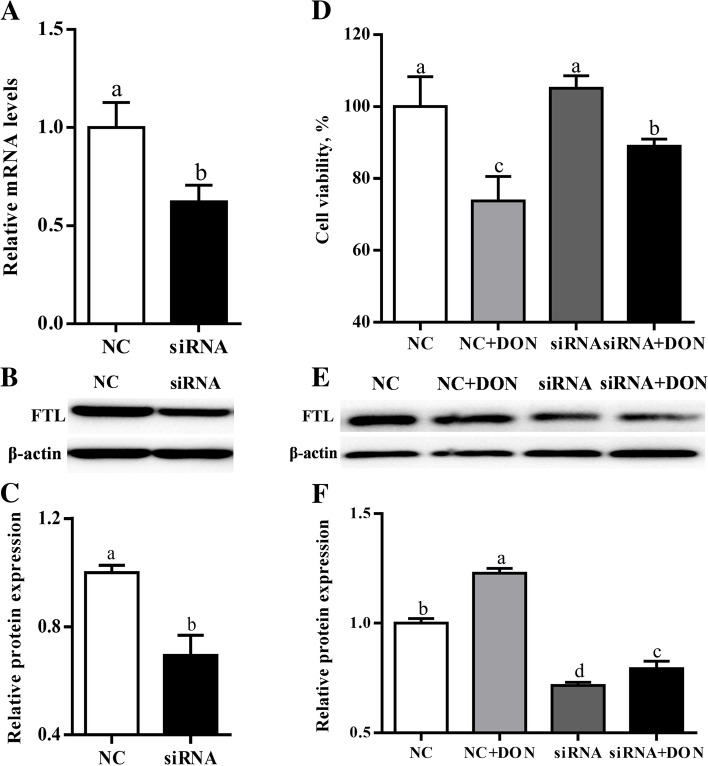

Compared with the control, the IPEC-J2 cells treated with FTL-specific siRNA had downregulated (P < 0.05) FTL expression at mRNA level (Fig. 6A). Furthermore, the FTL-specific siRNA treatment also downregulated (P < 0.05) FTL protein production by IPEC-J2 cells (Fig. 6B and C). Compared with the control, DON supplementation reduced (P < 0.05) the viability of IPEC-J2 cells by 26.2%, while knockdown of FTL mitigated (P < 0.05) these changes induced by DON (Fig. 6D). Additionally, DON supplementation upregulated (P < 0.05) FTL protein production by IPEC-J2 cells compared with the control (Fig. 6E and F). Notably, upregulation of the FTL protein production observed in the DON group was prevented (P < 0.05) in the DON+siRNA group (Fig. 6E and F).

Fig. 6.

Verification of the role of FTL in involvement in DON-mediated ferroptosis in IPEC-J2 cells. Relative mRNA (A), a representative image (B) and the relative density (C) of protein bands of FTL in IPEC-J2 cell after FTL siRNA transfection. IPEC-J2 cell viability was analyzed by CCK-8 after treated by FTL siRNA transfection and DON treatment (D). A representative image (E) and the relative density (F) of protein bands of FTL in IPEC-J2 cell after FTL siRNA transfection and DON treatment. Values are expressed as means ± SD, n = 3–6. Labeled means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05. NC, cells treated with negative control siRNA; siRNA, cells treated with FTL siRNA; NC+DON, cell treated with negative control siRNA plus DON; siRNA+DON, cell treated with FTL siRNA plus DON

Discussion

Dietary supplementation of DON at 1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg was shown to induce intestinal damage. Piglets that consumed DON manifested pathological signs of intestinal injury, including degeneration, necrosis and lymphocyte hyperplasia, and (or) lamina propria edema in duodenum, jejunum and ileum. These outcomes were in agreement with previous studies, which have reported that pigs fed diets contaminated with 2.89 and 4.0 mg/kg DON exhibited gastrointestinal damage [16, 19, 20]. In addition, LPS is a pivotal virulence factor and present in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria [21]; increased gut permeability or damage can be recognized by the leakage of LPS into the blood [22, 23]. Our results indicate a higher serum LPS concentration for DON supplementation than for the control, which would seem to confirm an impairment of the intestinal integrity and injury. Notably, although the Chinese safety standard sets 1.0 mg/kg for DON in pig compound feed [3], the current study showed that 1.0 mg/kg of DON had caused significant damage to the gastrointestinal tract of piglets. These findings warn us that suitable remediation strategy for DON need to be applied in the feed industry.

Impairment of redox balance is well-documented as one of the common mechanisms for DON-triggered cell deaths in different organs of animals [24–26]. Indeed, the piglets exposed to 1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg DON suffered from intestinal oxidative stress, as indicated by increase of the biomarkers of lipid oxidation (MDA) and protein oxidation (PC) to varying degrees in duodenum, jejunum and ileum. Intriguingly, SOD and GSH, which play pivotal roles in the antioxidant defense, were partly increased by DON in duodenum, jejunum and (or) ileum in the current study. This might be explained as a compensatory mechanism that piglets activated the antioxidant system as an adaptation to the DON-induced oxidative damage in intestine [27]. This helps piglets to maintain the redox homeostasis under DON-induced damage in intestine [27]. These outcomes are in agreement with previous reports, which reported that 3.0 mg/kg and 10 μmol/L DON impaired the redox homeostasis in mice and human intestinal cell line Caco-2 [28–30]. Taken together, these results implicate that DON-induced oxidative stress as the cause of cell death could be one of the major reasons for the intestinal damage [21–33].

An interesting finding from the present study is that dysregulation of ferroptosis signaling expression appears to be a novel mechanism for the DON-induced intestinal injury damage in piglets. Specifically, dietary DON supplementation upregulated of DMT1, FTL and FTH1, and downregulated FPN, FSP1 and CISD1 at mRNA and (or) protein levels in the duodenum. Because DMT1 is responsible for Fe2+ import, which would result in lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis, and FPN is responsible for the Fe2+ export, which plays roles in inhibiting ferroptosis [34], both FSP1 and CISD1 can protect against mitochondrial lipid peroxidation, and thus inhibit ferroptosis [35, 36]. The upregulation of DMT1 and downregulation of FPN, FSP1 and CISD1 by DON may induce ferroptosis in this study. Ferritin, a protein complex represented by FTL and FTH1, plays roles in cytoplasmic iron storage and contributes to inhibiting ferroptosis [37]. Strikingly, these two proteins were upregulated by DON in the present study, which may be interpreted as a complex feedback mechanism working against DON-induced ferroptosis.

Furthermore, the in vitro study with IPEC-J2 cells confirmed that ferroptosis is involved in the DON-induced cell death in IPEC-J2 cells [8]. Specifically, DON decreased the viability of IPEC-J2 cells, while this change was alleviated by the supplementation of an iron chelator DFP, which is a potent inhibitor of ferroptosis. These outcomes revealed that ferroptosis might involve in the DON-mediated cell death. Furthermore, DON upregulated 4 ferroptosis-related genes (DMT1, STEAP3, ACSL4 and FTL) [38–42]. Notably, the DFP treatment prevented or alleviated the changes on IPEC-J2 cell ACSL4 and FTL expression that was induced by DON. These outcomes further demonstrated that ferroptosis may be involved in the DON-induced cell death in the current study.

Because FTL was upregulated by DON in both the duodenum of piglets and IPEC-J2 cells, this study verified that DON mediates ferroptosis. Consistent with previous findings, DON reduced the viability of IPEC-J2 cells, while compensatory feedback for the upregulation of anti-ferroptosis protein FTL [43]. Notably, the present study showed that specific siRNA knockdown FTL protein production compromised the DON-induced cytotoxicity in IPEC-J2 cells. It is possible that FTL knockdown leads to an iron-rich response, which would lead to decelerated iron uptake and accelerated iron efflux, resulting in the decrease in the intracellular bioactive iron, and thus mitigating ferroptotic cell death in response to DON [13, 37]. However, the exact functions and mechanism of FTL in DON-induced ferroptosis need further exploration.

Conclusions

In summary, the present study found that consumption of feed contaminated with ≥ 1.0 mg/kg DON caused piglet intestinal damage, as evidenced by changes in the histopathologic lesions and elevated serum LPS concentrations, presumably due to leaky gut. Meanwhile, the DON-induced intestinal injury was further evidenced by the impairment of redox homeostasis and ferroptosis signaling. Furthermore, DFP, a potent ferroptosis inhibitor, alleviated DON-induced cell death in IPEC-J2 cells in the present study. This result provided further evidence that ferroptosis might be involved in the DON-induced cell death. Moreover, specific siRNA knockdown FTL protein production compromised the DON-induced cytotoxicity in IPEC-J2 cells. Overall, these findings helped us better understand the toxicity of DON and provided novel target for the development remediation strategies to detoxify DON in piglets.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Ingredients and nutrients composition of the Control diet.

Additional file 2: Fig. S1. Effects of DON (A) and DFP (B) on cell viability.

Additional file 3: Table S2. The sequences of siRNA for the knockdown analysis.

Additional file 4: Table S3. List of primers used for q-PCR analysis.

Additional file 5: Table S4. List of antibodies used for western blot analysis.

Abbreviations

- ACSL4

Acyl-CoA synthetase long chain family member 4

- ALOX5

Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase

- ALOX12

Arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase, 12S type

- ALOX15

Arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase

- CISD1

CDGSH iron sulfur domain 1

- DAO

Diamine oxidase

- DMT1

Divalent metal transporter 1

- DON

Deoxynivalenol

- FPN

Ferroportin

- FSP1

Ferroptosis suppressor protein 1

- FTL

Ferritin light chain

- FTH1

Ferritin heavy chain 1

- GPX4

Glutathione peroxidase 4

- GSH

Glutathione

- HSPB1

Heat shock protein family B (small) member 1

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- MDA

Malondialdehyde

- PC

Protein carbonyl

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SLC7A11

Solute carrier family 7 member 11

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- STEAP3

Six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3

- T-AOC

Total antioxidant capacity

- TFR1

Transferrin receptor

Authors’ contributions

LHS and HW designed the research; ML, LZ, YXM, JHL, JCY and JW conducted the experiments and analyzed the data; LM and LHS wrote the paper; NAK and HW help review and edit the paper; LHS had the primary responsibility for the final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China, Projects (2016YFD0501207 and 2018YFD0500601) and a donation from Jiangsu Aomai Bio-technology Co., Ltd.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are publicly available.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The animal protocol for this study (HZAUSW-2018-028) was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Huazhong Agricultural University, China.

Consent for publication

All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Hao Wu, Email: whao.1988@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Lvhui Sun, Email: lvhuisun@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Ma R, Zhang L, Liu M, Su YT, Xie WM, Zhang NY, et al. Individual and combined occurrence of mycotoxins in feed ingredients and complete feeds in China. Toxins (Basel) 2018;10(3):113. doi: 10.3390/toxins10030113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu M, Zhang L, Chu XH, Ma R, Wang YW, Liu Q, et al. Effects of deoxynivalenol on the porcine growth performance and intestinal microbiota and potential remediation by a modified HSCAS binder. Food Chem Toxicol. 2020;141:111373. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao L, Zhang L, Xu ZJ, Liu XD, Chen LY, Dai JF, et al. Occurrence of aflatoxin B 1, deoxynivalenol and zearalenone in feeds in China during 2018-2020. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2021;12(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s40104-021-00603-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li X, Guo Y, Zhao L, Fan Y, Ji C, Zhang J, et al. Protective effects of Devosia sp. ANSB714 on growth performance, immunity function, antioxidant capacity and tissue residues in growing-finishing pigs fed with deoxynivalenol contaminated diets. Food Chem Toxicol. 2018;121:246–251. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang L, Ma R, Zhu MX, Zhang NY, Liu XL, Wang YW, et al. Effect of deoxynivalenol on the porcine acquired immune response and potential remediation by a novel modified HSCAS adsorbent. Food Chem Toxicol. 2020;138:111187. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luo S, Terciolo C, Neves M, Puel S, Naylies C, Lippi Y, et al. Comparative sensitivity of proliferative and differentiated intestinal epithelial cells to the food contaminant, deoxynivalenol. Environ Pollut. 2021;277:116818. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coppa CFSC, Cirelli AC, Gonçalves BL, Barnabé EMB, Petta T, Franco LT, et al. Mycotoxin occurrence in breast milk and exposure estimation of lactating mothers using urinary biomarkers in São Paulo. Brazil. Environ Pollut. 2021;279:116938. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu M, Zhao L, Gong GX, Zhang L, Shi L, Dai JF, et al. Invited review: Remediation strategies for mycotoxin control in feed. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2022;13(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s40104-021-00661-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waché YJ, Valat C, Postollec G, Bougeard S, Burel C, Oswald IP, et al. Impact of deoxynivalenol on the intestinal microflora of pigs. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10(1):1–17. doi: 10.3390/ijms10010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang S, Wu KT, Xue DF, Zhang C, Rajput SA, Qi DS. Mechanism of deoxynivalenol mediated gastrointestinal toxicity: Insights from mitochondrial dysfunction. Food Chem Toxicol. 2021;153:112214. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2021.112214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooft JM, Bureau DP. Deoxynivalenol: Mechanisms of action and its effects on various terrestrial and aquatic species. Food Chem Toxicol. 2021;157:112616. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2021.112616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Yang S, Li P, Wu A, Nepovimova E, Long M, Wu W, et al. MicroRNA regulates the toxicological mechanism of four mycotoxins in vivo and in vitro. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2022;13(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s40104-021-00653-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang XJ, Stockwell BR, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22(4):266–282. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rotter BA, Prelusky DB, Pestka JJ. Toxicology of deoxynivalenol (vomitoxin) J Toxicol Environ Health. 1996;48(1):1–34. doi: 10.1080/009841096161447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NRC . Nutrient requirements of swine. Washington: Natl Acad Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang S, Yang JC, Zhang B, Wu K, Yang A, Li C, et al. Deoxynivalenol impairs porcine intestinal host defense peptide expression in weaned piglets and IPEC-J2 cells. Toxins (Basel) 2018;10(12):541. doi: 10.3390/toxins10120541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun LH, Zhang NY, Zhu MK, Zhao L, Zhou JC, Qi DS. Prevention of aflatoxin B1 hepatoxicity by dietary selenium is associated with inhibition of cytochrome P450 isozymes and up-regulation of 6 selenoprotein genes in chick liver. J Nutr. 2016;146:655–661. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.224626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang JQ, Ren FZ, Jiang YY, Xiao C, Lei XG. Selenoproteins protect against avian nutritional muscular dystrophy by metabolizing peroxides and regulating redox/apoptotic signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;83:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao H, Tan BE, Wu MM, Yin YL, Li TJ, Yuan DX, et al. Effects of composite antimicrobial peptides in weanling piglets challenged with deoxynivalenol: II. Intestinal morphology and function. J Anim Sci. 2013;91(10):4750–4756. doi: 10.2527/jas.2013-6427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu MM, Xiao H, Ren WK, Yin J, Tan B, Liu G, et al. Therapeutic effects of glutamic acid in piglets challenged with deoxynivalenol. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e100591. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu RZ, He ZY, Liu M, Tan JJ, Zhang HF, Hou DX, et al. Dietary protocatechuic acid ameliorates inflammation and up-regulates intestinal tight junction proteins by modulating gut microbiota in LPS-challenged piglets. J Anim Sci Biotechnol. 2020;11:92. doi: 10.1186/s40104-020-00492-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilani S, Howarth GS, Kitessa SM, Forder REA, Tran CD, Hughes RJ. New biomarkers for intestinal permeability induced by lipopolysaccharide in chickens. Anim Prod Sci. 2016;56:1984–1997. doi: 10.1071/AN15725. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alhenaky A, Abdelqader A, Abuajamieh M, Al-Fataftah AR. The effect of heat stress on intestinal integrity and salmonella invasion in broiler birds. J Therm Biol. 2017;70(Pt B):9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jtherbio.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li DT, Ma HR, Ye YQ, Ji CY, Tang XH, Ouyang D, et al. Deoxynivalenol induces apoptosis in mouse thymic epithelial cells through mitochondria-mediated pathway. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2014;38(1):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra S, Dwivedi PD, Pandey HP, Das M. Role of oxidative stress in Deoxynivalenol induced toxicity. Food Chem Toxicol. 2014;72:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2014.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang JM, Jin YC, Wu SL, Yu H, Zhao Y, Fang HT, et al. Deoxynivalenol induces oxidative stress, inflammatory response and apoptosis in bovine mammary epithelial cells. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 2019;103(6):1663–1674. doi: 10.1111/jpn.13180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao L, Feng Y, Deng J, Zhang NY, Zhang WP, Liu XL, et al. Selenium deficiency aggravates aflatoxin B1-induced immunotoxicity in chick spleen by regulating 6 selenoprotein genes and redox/inflammation/apoptotic signaling. J Nutr. 2019;149:894–901. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxz019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kouadio JH, Mobio TA, Baudrimont I, Moukha S, Dan SD, Creppy EE. Comparative study of cytotoxicity and oxidative stress induced by deoxynivalenol, zearalenone or fumonisin B1 in human intestinal cell line Caco-2. Toxicology. 2005;213(1–2):56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liao SM, Liu G, Tian B, Qi M, Li JJ, Li XQ, et al. Fullerene C60 protects against intestinal injury from deoxynivalenol toxicity by improving antioxidant capacity. Life (Basel) 2021;11(6):491. doi: 10.3390/life11060491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ren ZH, Guo CY, He HY, Zuo ZC, Hu YC, Yu SM, et al. Effects of deoxynivalenol on mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy in pig spleen lymphocytes. Food Chem Toxicol. 2020;140:111357. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wan MLY, Turner PC, Co VA, Wang MF, Amiri KMA, El-Nezami H. Schisandrin A protects intestinal epithelial cells from deoxynivalenol-induced cytotoxicity, oxidative damage and inflammation. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):19173. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-55821-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liao P, Li YH, Li MJ, Chen XF, Yuan DX, Tang M, et al. Baicalin alleviates deoxynivalenol-induced intestinal inflammation and oxidative stress damage by inhibiting NF-κB and increasing mTOR signaling pathways in piglets. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020;140:111326. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang M, Yuan DX, Liao P. Berberine improves intestinal barrier function and reduces inflammation, immunosuppression, and oxidative stress by regulating the NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathway in deoxynivalenol-challenged piglets. Environ Pollut. 2021;289:117865. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bao WD, Pang P, Zhou XT, Hu F, Xiong W, Chen K, et al. Loss of ferroportin induces memory impairment by promoting ferroptosis in Alzheimer's disease. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28(5):1548–1562. doi: 10.1038/s41418-020-00685-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan H, Li XM, Zhang XJ, Kang R, Tang DL. CISD1 inhibits ferroptosis by protection against mitochondrial lipid peroxidation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;478(2):838–844. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doll S, Freitas FP, Shah R, Aldrovandi M, da Silva MC, Ingold I, et al. FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature. 2019;575(7784):693–698. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1707-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xie Y, Hou W, Song X, Yu Y, Huang J, Sun X, et al. Ferroptosis: process and function. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23(3):369–379. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xie L, Zheng W, Xin N, Xie J, Wang T, Wang ZY. Ebselen inhibits iron-induced tau phosphorylation by attenuating DMT1 up-regulation and cellular iron uptake. Neurochem Int. 2012;61(3):334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuan H, Li XM, Zhang XY, Kang R, Tang DL. Identification of ACSL4 as a biomarker and contributor of ferroptosis. Biochem Bioph Res Commun. 2016;478(3):1338–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen YJ, Wang JY, Wang JT, Wang JH, Wang RQ, Xi QH, et al. Astragalus polysaccharide prevents ferroptosis in a murine model of experimental colitis and human Caco-2 cells via inhibiting NRF2/HO-1 pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2021;911:174518. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2021.174518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song QX, Peng SX, Sun ZP, Heng XY, Zhu XS. Temozolomide drives ferroptosis via a DMT1-dependent pathway in glioblastoma cells. Yonsei Med J. 2021;62(9):843–849. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2021.62.9.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ye CL, Du Y, Yu X, Chen ZY, Wang L, Zheng YF, et al. STEAP3 affects ferroptosis and progression of renal cell carcinoma through the p53/xCT pathway. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2022;21:15330338221078728. doi: 10.1177/15330338221078728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kang RF, Li RN, Dai PY, Li Z, Li YS, Li CM. Deoxynivalenol induced apoptosis and inflammation of IPEC-J2 cells by promoting ROS production. Environ Pollut. 2019;251:689–698. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Ingredients and nutrients composition of the Control diet.

Additional file 2: Fig. S1. Effects of DON (A) and DFP (B) on cell viability.

Additional file 3: Table S2. The sequences of siRNA for the knockdown analysis.

Additional file 4: Table S3. List of primers used for q-PCR analysis.

Additional file 5: Table S4. List of antibodies used for western blot analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are publicly available.