Abstract

Background

The relationship between biomarkers of metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance, plasma triglyceride/HDL cholesterol (TG/HDL-C) ratio, on the rate of cognitive decline in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia stages of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is unknown. The role of peripheral and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of Apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1), a key functional component of HDL, on cognitive decline also remains unclear among them. Here we evaluate baseline plasma TG/HDL-C ratio and CSF and plasma ApoA1 levels and their relation with cognitive decline in the MCI and Dementia stages of AD.

Patients and methods

A retrospective longitudinal study (156 participants; 106 MCI, 50 AD dementia) from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, with an average of 4.0 (SD 2.8) years follow-up. Baseline plasma TG/HDL-C, plasma, and CSF ApoA1 and their relationship to inflammation and blood–brain barrier (BBB) biomarkers and longitudinal cognitive outcomes were evaluated. Multivariable linear mixed effect models were used to assess the effect of baseline analytes with longitudinal changes in Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE), Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB), and Logical Memory delayed recall (LM) score after controlling for well-known covariates.

Results

A total of 156 participants included 98 women, 63%; mean age was 74.9 (SD 7.3) years. At baseline, MCI and dementia groups did not differ significantly in TG/HDL-C (Wilcoxon W statistic = 0.39, p = 0.39) and CSF ApoA1 levels (W = 3642, p = 0.29), but the dementia group had higher plasma ApoA1 than the MCI group (W = 4615, p = 0.01). Higher TG/HDL-C ratio was associated with faster decline in CDR-SB among MCI and dementia groups. Higher plasma ApoA1 was associated with faster decline in MMSE and LM among MCI, while in contrast higher CSF ApoA1 levels related to slower cognitive decline in MMSE among MCI. CSF and plasma ApoA1 also show opposite directional correlations with biomarkers of BBB integrity. CSF but not plasma levels of ApoA1 positively correlated to inflammation analytes in the AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications (KEGG ID:KO04933).

Conclusions

Biomarkers of metabolic syndrome relate to rate of cognitive decline among MCI and dementia individuals. Elevated plasma TG/HDL-C ratio and plasma ApoA1 are associated with worse cognitive outcomes in MCI and dementia participants. CSF ApoA1 and plasma ApoA1 likely have different roles in AD progression in MCI stage.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13195-023-01203-y.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Metabolic syndrome, ApoA1, Triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein ratio, Cognitive decline, MCI, Dementia, Blood–brain barrier, Neuroinflammation, CSF, Apolipoprotein

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome refers to the co-occurrence of cardiovascular risk factors, including insulin resistance, obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, and identifies patients who are at high risk of developing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes [1]. Meta-analyses have reported that those with diabetes diagnosis have a 25–91% elevated risk of developing dementia in their lifetimes [2], while metabolic syndrome increased the risk of progression from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to dementia [3]. Cardiovascular risk factors and diabetes are also well-known modifiable factors for dementia risk worldwide [4]. However, the relationship between biomarkers of metabolic syndrome on the rate of cognitive decline among MCI and dementia patients is still poorly characterized.

Plasma triglyceride-to-HDL cholesterol (TG/HDL-C) is often routinely measured in general clinical practice and is often elevated in individuals with metabolic syndrome [5, 6]. High TG/HDL-C is the single most powerful predictor of extensive coronary heart disease among other lipid variables [7]. High TG/HDL-C has been reported to be closely related to systemic insulin resistance and subclinical inflammation in adults [8, 9]. However, there is conflicting information concerning the association of TGs on Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and its related outcomes [10–13], as the changes observed could be related to disease stage. Imaging studies have shown that higher insulin resistance and subsequent hyperinsulinemia predict hypermetabolism in the early mild cognitive impairment (MCI) stage clinical progressors and hypometabolism in medial temporal regions in the later AD dementia stage [14]. Clarifying the role of TG/HDL-C changes in both MCI and AD dementia stages is important for targeted lifestyle and metabolic syndrome modifying therapies to improve cognitive outcomes.

Elevated plasma high-density lipoproteins (HDL) levels have been reported to associate with sharper mental abilities in the elderly [9, 10], while low HDL levels are a risk factor for future memory decline in middle-aged adults [11]. Apolipoprotein A1 (ApoA1) is the key functional component of HDL that participates in cholesterol efflux. APOA1 gene polymorphism has also been related to cognitive impairment [15]. ApoA1 is anti-atherogenic and reduces vascular inflammation and thus has protective effects on cardiovascular and stroke risk in addition to amyloid changes related to AD [16]. Plasma ApoA1 is a stronger prognostic marker than HDL cholesterol for cardiovascular disease and ischemic stroke in some studies [17, 18]. ApoA1 has robust animal and clinical data supporting its role in AD pathophysiology [19, 20]. Lower plasma ApoA1 and HDL levels correlate with higher amyloid burden, increased risk for AD [21, 22], and increased cognitive score severity in AD [22]. However, among normal cognition elderly subjects, the association between plasma ApoA1 and the risk of dementia is inconclusive in results from prospective and cohort studies [23–26].

Cells in the brain do not express ApoA1, and plasma ApoA1 enters the central nervous system (CNS) from the periphery to become a component of CNS lipoproteins [27]. Results from AD mouse models suggest that ApoA1 may be regulated by distinct mechanisms on either side of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and that ApoA1 may serve to integrate peripheral and CNS lipid metabolism [28]. The relative contributions of peripheral and CNS pools of ApoA1 to neuropathological and behavioral outcomes and their association with BBB integrity is controversial [16]. However, clarity on this association is important for potential targeted therapeutic interventions against ApoA1 mechanisms in clinical patients with AD.

This study has two primary aims: (1) to address our lack of understanding of the relationship between a commonly used clinical biomarker of metabolic syndrome, plasma TG/HDL-C ratio, and cognitive outcomes in the MCI or dementia stages of AD, and (2) given that increased BBB permeability and related biomarker changes have been reported in MCI and dementia stages of AD [29], to clarify the relationship between plasma or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) ApoA1 levels and clinical outcomes as well as evaluate their levels in relation to BBB integrity biomarkers. Our main hypotheses were as follows: (a) that plasma TG/HDL-C ratio is a clinical biomarker that associates with measures of longitudinal cognitive decline in MCI and dementia and (b) both plasma and CSF levels of ApoA1 equally associate with measures of longitudinal cognitive decline in MCI and dementia. We addressed these hypotheses among MCI and dementia participants in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) cohort.

Methods

Patients

The ADNI is a longitudinal multicenter study designed to develop clinical, imaging, genetic, and biochemical biomarkers for the early detection and tracking of AD. ADNI was launched by the National Institute of Aging with additional support from private pharmaceutical companies and nonprofit organizations. The eligibility criteria for the first phase of the ADNI study are described in the ADNI1 protocol (http://adni.loni.usc.edu/methods/documents/). Briefly, eligible participants (55 to 90 years old) had an informant that provided an independent evaluation of functioning and was fluent in either English or Spanish. Participants had completed at least 6 years of education (or had a work history sufficient to exclude intellectual disability). For clinical staging, the categories of MCI (MCI group) and AD dementia (dementia group) were used as noted in the ADNIMERGE dataset (downloaded on 10/05/2020). AD biomarker concentration data in CSF, including CSF Aβ1–42, t-tau, and p-tau181, were generated using the Elecsys method [30] provided in ADNIMERGE. Previously published CSF Aβ1–42 and p-tau181 cut points in the ADNI sample, Aβ1–42 < 976.6 pg/mL, p-tau181 > 21.8 pg/mL, were used to define amyloid-positive and tau-positive frequency in the MCI and dementia groups [31].

CSF and plasma ApoA1 along with BBB biomarkers

In ADNI, levels of ApoA1 and BBB biomarkers (Vascular cell adhesion protein 1, VCAM1; Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1, ICAM1; and Matrix metallopeptidase 9, MMP9) were assessed in a fasting state with the RBM Discovery MAP® v.1.0 panel, on a Luminex platform (Myriad Genetics; Salt Lake City, UT). The CSF and plasma multiplex data used in this analysis were cleaned and quality controlled based on the methodology described in the statistical analysis of the Biomarkers Consortium Data Primer. The least detectable level for ApoA1, VCAM1, ICAM1, and MMP9 was 0.006875 μg/ml, 0.0148 ng/ml, 0.84 ng/ml, and 4.08 ng/ml, respectively.

Inflammatory biomarkers

We explored the relationship between ApoA1 and a panel of CSF and plasma inflammatory biomarker data in ADNI participants who had curated CSF and plasma multiplex data (see Supplementary material), the details of which have been published previously [32].

Plasma TG/HDL-C

Total TG and HDL-C data was downloaded from the ADNI_LIPIDOMICSRADER file on 12/15/2021. Total TG and HDL-C were determined using COBAS C311 analyzer assays (Roche Diagnostics, Florham Park, NJ), which utilize enzymatic colorimetric methods. These analysis methods are further described in ADNI reference documents with plasma tests performed after overnight fasting (http://adni.loni.usc.edu/methods/documents/).

Cognitive and functional measures

The Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) [33], Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB) [34], and Logical Memory delayed recall score (LM) (Wechsler Memory Scale, Logical Memory subtest) [35] were used to characterize the degree of baseline cognitive and functional deficits and to assess cognitive and functional change from baseline at each year of longitudinal follow-up.

Body mass index (BMI), lipid-modifying medications, and diabetes status

Participant BMI ranged from 17.2 to 38.8, mean 25.5 (3.7). A history of use of lipid profile modifying medications (see Supplementary material) was noted among 40 of the 156 participants at the time of plasma and CSF measurements. The presence of type II diabetes among participants was ascertained from their medical history and included 6 of the 156 participants.

Statistical analysis

Normality was assessed for continuous variables by Q-Q plots following which a t-test was applied to compare normally distributed continuous variables. Wilcoxon rank-sum test with W statistic was applied to compare non-normally distributed continuous variables. Chi-squared test was conducted for categorical variables. Multivariable linear mixed effect models were used to assess the effect of baseline plasma TG/HDL-C ratio, plasma ApoA1, and CSF ApoA1 when taken together with changes in CDR-SB and MMSE (dependent variable) after controlling for well-known covariates of age, sex, education years, BMI, CSF Abeta-42, CSF p-tau, use of lipid-lowering medications, and APOEε4 status. Multiple imputation using fully conditional specification was performed to account for missing data in covariates used in the multivariable models (missing data in BMI, CSF p-tau variables) and 10 imputation data sets were created. Models were run separately for each imputation data set and then pooled to provide sensitivity analysis. Additional exploratory analyses evaluated whether associations between baseline markers and changes in cognitive outcomes within strata were defined by APOEε4 status. Univariate Pearson correlations between the inflammatory markers and TG/HDL and ApoA1 with a false discovery rate (FDR) correction of 0.05 were also completed. The sample size within each stratum prevented evaluation of interactions between APOEε4 status and the other markers and for the role of diabetes in these results.

All tests were two-tailed and with a significance level of < 0.05. R version 3.5.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), SAS software version 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC), and IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. (IBM, Armonk, NY) were used for analyses.

Functional pathway analysis on inflammatory analytes of interest

The inflammatory analytes of significance identified in the univariate correlational analysis in relation to TG/HDL, plasma, and CSF ApoA1 were entered into STRING: functional protein association networks for pathway enrichment analysis [36]. The top pathway for each analysis with the largest analyte count and the lowest P value following false discovery rate (FDR) correction is reported.

Results

A total of 156 participants were included in the analysis [MCI group (n = 106) and Dementia group (n = 50); 98 women, 63%; mean (SD) age was 74.9 (7.3) years]. 64 of 106 in the MCI group (60.3%) and 37 of 50 in the dementia group (74%) were CSF amyloid and tau positive supporting underlying AD pathology. Table 1 provides demographics, baseline cognitive data, and biomarker data of participants from the ADNI cohort. At baseline, the MCI and dementia groups did not differ significantly for TG/HDL (W = 0.39, p = 0.39) and CSF ApoA1 levels (W = 3642, p = 0.29), but the dementia group had higher plasma ApoA1 than the MCI group (W = 4615, p = 0.01). Among MCI, plasma/CSF ApoA1 ratio was 744.96 (SD 432.92) and dementia 957.472 (SD 606.822). The TG/HDL ratio correlated moderately with BMI (r = 0.33; p = 0.002 for MCI; r = 0.35; p = 0.070 for Dementia). CSF ApoA1 was positively correlated to CSF Abeta 42 levels in MCI (r = 0.36, p < 0.001) and had borderline significance for dementia (r = 0.32, p = 0.069) but not p-tau181 or total-tau. TG/HDL and plasma ApoA1 were not significantly correlated to CSF AD biomarkers (Supplementary tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Overall (N = 156) | MCI group (N = 106) | Dementia group (N = 50) | Test | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | N | Statistics | N | Statistics | N | Statistics | Statistic | p-value |

| Age (years) | 156 | 74.9 ± 7.3 | 106 | 75.0 ± 6.9 | 50 | 74.5 ± 8.0 | 0.41 | 0.68a |

| Gender | 156 | 106 | 50 | 3.69 | 0.055c | |||

| Male | 58 (37.2) | 34 (32.1) | 24 (48.0) | |||||

| Female | 98 (62.8) | 72 (67.9) | 26 (52.0) | |||||

| BMI | 122 | 25.5 ± 3.7 | 84 | 25.6 ± 3.7 | 38 | 25.4 ± 3.8 | 0.22 | 0.82a |

| Education (years) | 156 | 16.0 [14.0, 18.0] | 106 | 16.0 [14.0, 18.0] | 50 | 15.5 [12.0, 18.0] | 3291 | 0.016b |

| APOE ε4 carrier | 156 | 94 (60.3) | 106 | 58 (54.7) | 50 | 36 (72.0) | 4.24 | 0.040c |

| MMSE | 156 | 25.8 ± 2.4 | 106 | 26.9 ± 1.7 | 50 | 23.5 ± 1.9 | 10.8 | < 0.001a |

| CDR-SB | 156 | 2.4 ± 1.7 | 106 | 1.6 ± 0.89 | 50 | 4.3 ± 1.6 | -11.2 | < 0.001a |

| Logical memory delayed recall | 156 | 2.0 [0.00, 4.0] | 106 | 3.0 [1.00, 6.0] | 50 | 0.00 [0.00, 2.0] | 2595 | < 0.001b |

| CSF A-Beta42 (log2)* | 156 | 650.5 [497.5, 862.6] | 106 | 665.3 [565.2, 957.8] | 50 | 545.7 [430.7, 730.9] | 3162 | 0.004b |

| CSF P-tau(log2)* | 155 | 31.3 [22.5, 40.4] | 106 | 29.5 [21.8, 39.1] | 49 | 33.3 [26.0, 44.3] | 4250 | 0.10b |

| Type 2 diabetes medical history | 156 | 6 (3.84) | 106 | 5 (4.71) | 50 | 1 (2) | 0.68 | 0.37c |

| Any lipid-modifying medication use | 156 | 40 (25.6) | 106 | 26 (24.5) | 50 | 14 (28.0) | 0.21 | 0.64c |

| Plasma TG/HDL | 156 | 2.1 [1.3, 3.2] | 106 | 2.0 [1.2, 3.3] | 50 | 2.3 [1.4, 3.2] | 4152 | 0.39b |

| Plasma ApoA1 µg/ml | 156 | 0.56 [0.46, 0.73] | 106 | 0.55 [0.41, 0.71] | 50 | 0.59 [0.52, 0.86] | 4615 | 0.010b |

| CSF ApoA1 µg/ml | 156 | 0.0008 [0.0006, 0.0012] | 106 | 0.0008 [0.0006, 0.0012] | 50 | 0.0007 [0.0006, 0.0011] | 3642 | 0.29b |

| Follow-up (years) | 156 | 4.0 ± 2.8 | 106 | 4.9 ± 3.0 | 50 | 2.0 ± 0.5 | 9.8 | < 0.001a |

Statistics presented as mean ± SD, median [P25, P75], N (column %)

p-values: at-test with T statistic, bWilcoxon rank-sum test with W statistic, cPearson’s chi-square test with chi-square statistic

Bold p values: p < 0.05

*60.3% of the MCI group and 74% of the dementia group met CSF amyloid and tau thresholds supporting underlying AD pathology

Hypothesis 1: Plasma TG/HDL-C ratio and longitudinal cognitive decline

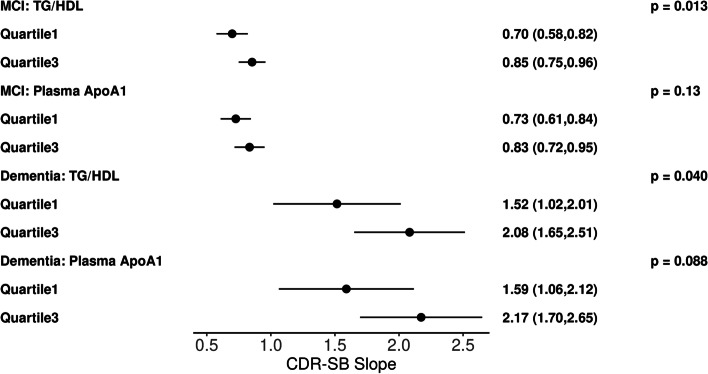

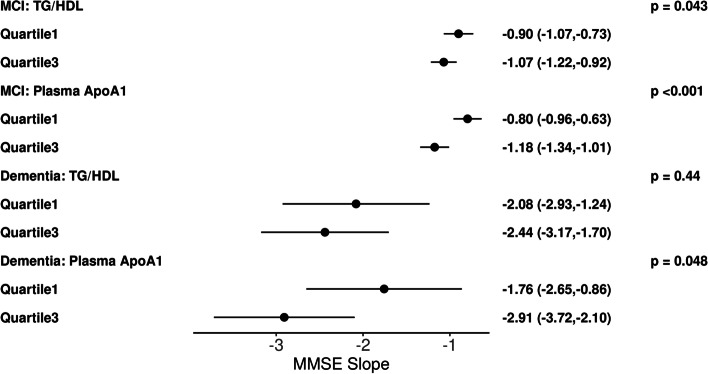

Among subjects in the MCI group, baseline plasma TG/HDL-C ratio was associated significantly with longitudinal change in MMSE (β − 1.13 [95% CI, − 0.25 to − 0.004], p = 0.043) and CDR-SB (β 0.12 [95% CI 0.02 to 0.21], p = 0.013), where higher TG/HDL-C had a faster rate of decline. Subjects in the dementia group also showed plasma TG/HDL-C ratio to be associated significantly with longitudinal change in CDR-SB (β 0.47 [95% CI 0.02 to 0.92], p = 0.04) with the same directional association (Table 2, Figs. 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Linear mixed model results of MCI and Dementia groups for plasma TG/HDL ratios and ApoA1 levels, and CSF ApoA1 levels

| MCI group | Dementia group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect |

Slope (95% CI) |

p-value |

Slope (95% CI) |

p-value |

| MMSE | ||||

| CSF ApoA1 |

0.204 (0.030,0.377) |

0.022 |

− 0.683 (− 1.525,0.159) |

0.11 |

| Plasma ApoA1 |

− 0.498 (− 0.744, − 0.253) |

< 0.001 |

− 1.546 (− 3.080, − 0.012) |

0.048 |

| TG/HDL ratio |

− 0.127 (− 0.251, − 0.004) |

0.043 |

− 0.299 (− 1.063, 0.466) |

0.44 |

| CDR-SB | ||||

| CSF ApoA1 |

− 0.025 (− 0.148, 0.099) |

0.69 |

0.112 (− 0.383, 0.607) |

0.65 |

| Plasma ApoA1 |

0.141 (− 0.041, 0.324) |

0.13 |

0.784 (− 0.118, 1.686) |

0.088 |

| TG/HDL ratio |

0.116 (0.024, 0.207) |

0.013 |

0.472 (0.023, 0.921) |

0.040 |

| LM | ||||

| CSF ApoA1 |

− 0.002 (− 0.144, 0.140) |

0.97 |

0.203 (− 0.145, 0.550) |

0.25 |

| Plasma ApoA1 |

− 0.303 (− 0.502, − 0.103) |

0.003 |

− 0.424 (− 1.053, 0.204) |

0.18 |

| TG/HDL ratio |

0.009 (− 0.091,0.109) |

0.87 |

0.141 (− 0.182, 0.464) |

0.39 |

MMSE, Mini-Mental Status Exam score; CDR-SB, Clinical Dementia Rating Scale–Sum of Boxes score; LM, logical memory delayed recall score. Positive slope notes faster progression CDR-SB; negative slope notes faster progression in MMSE and LM

Fig. 1.

Illustrative plots representing multivariable linear mixed effect model slope and 95% confidence interval results for analytes (TG/HDL, plasma APOA1) versus longitudinal CDR-SB score at the first-quartile and third quartiles in the MCI group (n = 106) or dementia group (n = 50)

Fig. 2.

Illustrative plots representing multivariable linear mixed effect model slope and 95% confidence interval results for analytes (TG/HDL, plasma APOA1) versus longitudinal MMSE score at the first quartile and third quartiles in the MCI group (n = 106) or dementia group (n = 50)

Hypothesis 2: Plasma and CSF levels of ApoA1 and longitudinal cognitive decline

Among subjects in the MCI group, baseline plasma ApoA1 was associated with a decline in MMSE (β − 4.98 [95% CI, − 0.74 to − 0.25], p < 0.001) and LM scores (β − 0.303 [95% CI, − 0.50 to − 0.10], p = 0.003). Among both MCI and dementia groups, higher plasma ApoA1 had a faster rate of decline. Similarly, in the dementia group, baseline plasma ApoA1 was also associated with MMSE decline (β − 1.55 [95% CI –3.01 to − 0.01], p = 0.048) (Table 2, Figs. 1 and 2). Conversely, lower CSF ApoA1 level had a faster rate of decline in MMSE (β 0.20 [95% CI, 0.03 to 0.38], p = 0.022) among MCI subjects. Key results remained robust after multiple imputation and sensitivity analysis (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis of linear mixed model results for the MCI and dementia groups for plasma TG/HDL, ApoA1, and CSF ApoA1 using imputed data

| MCI group | Dementia group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Slope (95% CI) | p-value | Slope (95% CI) | p-value |

| MMSE | ||||

| CSF ApoA1 |

0.219 (0.068, 0.370) |

0.005 |

− 0.407 (− 1.157, 0.344) |

0.29 |

| Plasma ApoA1 |

− 0.492 (− 0.717, − 0.266) |

< 0.001 |

− 1.207 (− 2.537, 0.123) |

0.075 |

| TG/HDL |

− 0.165 (− 0.275, − 0.054) |

0.004 |

− 0.247 (− 0.950, 0.455) |

0.49 |

| CDR-SB | ||||

| CSF ApoA1 |

− 0.065 (− 0.174, 0.044) |

0.24 |

− 0.015 (− 0.446, 0.417) |

0.95 |

| Plasma ApoA1 |

0.173 (0.006, 0.340) |

0.043 |

0.522 (− 0.246, 1.290) |

0.18 |

| TG/HDL |

0.152 (0.070, 0.234) |

< 0.001 |

0.402 (− 0.002, 0.807) |

0.051 |

| LM | ||||

| CSF ApoA1 |

0.039 (− 0.086, 0.165) |

0.54 |

0.118 (− 0.176, 0.412) |

0.43 |

| Plasma ApoA1 |

− 0.280 (− 0.467, − 0.094) |

0.003 |

− 0.344 (− 0.862, 0.174) |

0.19 |

| TG/HDL |

− 0.010 (− 0.101, 0.082) |

0.83 |

0.134 (− 0.147, 0.415) |

0.35 |

Linear mixed effect models

MMSE Mini-Mental Status Exam score, CDR-SB Clinical Dementia Rating Scale–Sum of Boxes score, LM Logical memory delayed recall score

Relationship between CSF, plasma ApoA1, and BBB biomarkers

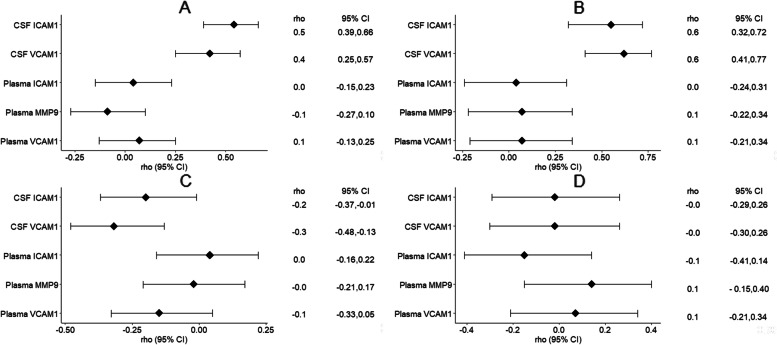

In the MCI group, CSF ApoA1 levels correlated positively with CSF ICAM1 and VACM1 levels [correlation range 0.42 to 0.54, all p < 0.001], while plasma ApoA1 levels correlated negatively with CSF ICAM1 and VCAM1 levels [correlation range − 0.20 to − 0.34, p < 0.001 to 0.04] (Tables 4 and 5, Fig. 3).

Table 4.

Correlations between lipid variables and CSF and plasma BBB integrity biomarkers in the MCI group

| All MCI | Apoeε4 + | Apoe4ε - | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | N | rho (95% CI) | p-value | N | rho (95% CI) | p-value | N | rho (95% CI) | p-value |

| CSF ApoA1 | CSF ICAM1 | 106 | 0.54 (0.39, 0.66) | < 0.001 | 58 | 0.51 (0.29, 0.68) | < 0.001 | 48 | 0.59 (0.37, 0.75) | < 0.001 |

| CSF VCAM1 | 106 | 0.42 (0.25, 0.57) | < 0.001 | 58 | 0.31 (0.06, 0.53) | 0.017 | 48 | 0.50 (0.25, 0.69) | < 0.001 | |

| Plasma ICAM1 | 106 | 0.04 (− 0.15, 0.23) | 0.69 | 58 | 0.03 (− 0.23, 0.29) | 0.81 | 48 | − 0.00 (− 0.29, 0.28) | 0.99 | |

| Plasma MMP9 | 106 | − 0.09 (− 0.27, 0.10) | 0.37 | 58 | − 0.11 (− 0.36, 0.16) | 0.43 | 48 | − 0.05 (− 0.33, 0.23) | 0.72 | |

| Plasma VCAM1 | 106 | 0.07 (− 0.13, 0.25) | 0.50 | 58 | 0.15 (− 0.12, 0.39) | 0.27 | 48 | − 0.07 (− 0.35, 0.22) | 0.62 | |

| Plasma ApoA1 | CSF ICAM1 | 106 | − 0.20 (− 0.37, − 0.01) | 0.044 | 58 | − 0.18 (− 0.42, 0.08) | 0.18 | 48 | − 0.22 (− 0.47, 0.07) | 0.13 |

| CSF VCAM1 | 106 | − 0.32 (− 0.48, − 0.13) | < 0.001 | 58 | − 0.44 (− 0.62, − 0.20) | < 0.001 | 48 | − 0.18 (− 0.44, 0.11) | 0.22 | |

| Plasma ICAM1 | 106 | 0.04 (− 0.16, 0.22) | 0.72 | 58 | 0.21 (− 0.05, 0.44) | 0.12 | 48 | − 0.11 (− 0.38, 0.18) | 0.48 | |

| Plasma MMP9 | 106 | − 0.02 (− 0.21, 0.17) | 0.86 | 58 | − 0.16 (− 0.40, 0.10) | 0.22 | 48 | 0.15 (− 0.14, 0.42) | 0.30 | |

| Plasma VCAM1 | 106 | − 0.15 (− 0.33, 0.05) | 0.13 | 58 | − 0.07 (− 0.33, 0.19) | 0.58 | 48 | − 0.16 (− 0.42, 0.13) | 0.28 | |

| TG/HDL | CSF ICAM1 | 106 | 0.09 (− 0.11, 0.27) | 0.38 | 58 | − 0.06 (− 0.31, 0.20) | 0.68 | 48 | 0.25 (− 0.04, 0.50) | 0.092 |

| CSF VCAM1 | 106 | 0.32 (0.14, 0.48) | < 0.001 | 58 | 0.34 (0.09, 0.55) | 0.009 | 48 | 0.30 (0.02, 0.54) | 0.038 | |

| Plasma ICAM1 | 106 | 0.01 (− 0.18, 0.20) | 0.92 | 58 | − 0.14 (− 0.39, 0.12) | 0.29 | 48 | 0.19 (− 0.10, 0.45) | 0.20 | |

| Plasma MMP9 | 106 | 0.13 (− 0.06, 0.31) | 0.19 | 58 | 0.21 (− 0.05, 0.44) | 0.11 | 48 | 0.02 (− 0.27, 0.30) | 0.90 | |

| Plasma VCAM1 | 106 | 0.12 (− 0.07, 0.31) | 0.21 | 58 | − 0.12 (− 0.36, 0.15) | 0.39 | 48 | 0.36 (0.08, 0.58) | 0.012 | |

rho Pearson’s correlation, CI Confidence interval, FDR < 0.05 in bold, ApoA1 Apolipoprotein, TG/HDL Plasma triglyceride/HDL cholesterol ratio

Table 5.

Correlations between lipid variables and CSF and plasma BBB integrity biomarkers in the dementia group

| All dementia | Apoe4 ε + | Apoe4ε- | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | N | rho (95% CI) | p-value | N | rho (95% CI) | p-value | N | rho (95% CI) | p-value |

| CSF ApoA1 | CSF ICAM1 | 50 | 0.55 (0.32, 0.72) | < 0.001 | 36 | 0.64 (0.40, 0.80) | < 0.001 | 14 | 0.39 (− 0.18, 0.76) | 0.18 |

| CSF VCAM1 | 50 | 0.62 (0.41, 0.77) | < 0.001 | 36 | 0.64 (0.40, 0.80) | < 0.001 | 14 | 0.57 (0.06, 0.85) | 0.030 | |

| Plasma ICAM1 | 50 | 0.04 (− 0.24, 0.31) | 0.79 | 36 | 0.18 (− 0.16, 0.48) | 0.29 | 14 | − 0.31 (− 0.72, 0.27) | 0.30 | |

| Plasma MMP9 | 50 | 0.07 (− 0.22, 0.34) | 0.65 | 36 | − 0.02 (− 0.35, 0.31) | 0.90 | 14 | 0.29 (− 0.29, 0.71) | 0.33 | |

| Plasma VCAM1 | 50 | 0.07 (− 0.21, 0.34) | 0.63 | 36 | 0.06 (− 0.27, 0.38) | 0.73 | 14 | 0.09 (− 0.46, 0.59) | 0.76 | |

| Plasma ApoA1 | CSF ICAM1 | 50 | − 0.02 (− 0.29, 0.26) | 0.90 | 36 | − 0.02 (− 0.34, 0.31) | 0.93 | 14 | − 0.02 (− 0.55, 0.52) | 0.94 |

| CSF VCAM1 | 50 | − 0.02 (− 0.30, 0.26) | 0.89 | 36 | 0.02 (− 0.31, 0.35) | 0.89 | 14 | − 0.19 (− 0.65, 0.38) | 0.52 | |

| Plasma ICAM1 | 50 | − 0.15 (− 0.41, 0.14) | 0.31 | 36 | − 0.14 (− 0.45, 0.20) | 0.41 | 14 | − 0.19 (− 0.65, 0.38) | 0.52 | |

| Plasma MMP9 | 50 | 0.14 (− 0.15, 0.40) | 0.34 | 36 | 0.14 (− 0.20, 0.45) | 0.42 | 14 | 0.11 (− 0.44, 0.61) | 0.70 | |

| Plasma VCAM1 | 50 | 0.07 (− 0.21, 0.34) | 0.63 | 36 | 0.15 (− 0.19, 0.46) | 0.38 | 14 | − 0.20 (− 0.66, 0.37) | 0.50 | |

| TG/HDL | CSF ICAM1 | 50 | − 0.00 (− 0.28, 0.28) | 0.98 | 36 | − 0.07 (− 0.39, 0.26) | 0.67 | 14 | 0.11 (− 0.45, 0.61) | 0.71 |

| CSF VCAM1 | 50 | − 0.09 (− 0.36, 0.19) | 0.51 | 36 | − 0.17 (− 0.47, 0.17) | 0.33 | 14 | 0.06 (− 0.49, 0.57) | 0.85 | |

| Plasma ICAM1 | 50 | 0.30 (0.02, 0.53) | 0.036 | 36 | 0.28 (− 0.05, 0.56) | 0.097 | 14 | 0.34 (− 0.23, 0.74) | 0.24 | |

| Plasma MMP9 | 50 | − 0.20 (− 0.45, 0.09) | 0.18 | 36 | − 0.10 (− 0.41, 0.24) | 0.57 | 14 | − 0.43 (− 0.78, 0.13) | 0.13 | |

| Plasma VCAM1 | 50 | 0.01 (− 0.27, 0.29) | 0.95 | 36 | − 0.13 (− 0.44, 0.20) | 0.44 | 14 | 0.39 (− 0.18, 0.76) | 0.17 | |

rho, Pearson’s correlation; CI, confidence interval; FDR < 0.05 in bold; ApoA1, apolipoprotein; TG/HDL, plasma triglyceride/HDL cholesterol ratio

Fig. 3.

Pearson correlation forest plots. A. CSF ApoA1 BBB markers in MCI group, B. CSF ApoA1 BBB markers in dementia group, C. Plasma ApoA1 BBB markers in MCI group, D. Plasma ApoA1 BBB markers in the dementia group

In the dementia group, CSF ApoA1 levels correlated positively with CSF ICAM1 and VACM1 levels [correlation range 0.55 to 0.62, all p < 0.001], while a negative correlation was observed between plasma ApoA1 and CSF ICAM1 and VCAM1, but this correlation was not significant.

Stratification by APOE ε4 status

To further evaluate the differential effects of APOE ε4 on key plasma and CSF analytes, we evaluated the robustness of above results among smaller sample sizes of APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers.

Among both APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers in the MCI and Dementia groups, CSF ApoA1 levels correlated positively with CSF ICAM1 and VCAM1 levels [correlation range 0.42 to 0.59, all p < 0.001], while plasma ApoA1 levels correlated negatively with CSF ICAM1 (− 0.20, p = 0.04) and VCAM1 levels (− 0.32. p < 0.001) only among MCI group APOE ε4carriers (Table 6).

Table 6.

Summary of Linear mixed model results of MCI and Dementia groups and by APOE ε4 status for plasma TG/HDL ratio and ApoA1, and CSF ApoA1 levels

| Analyte | All MCI (n = 106) | MCI APOE4 positive (n = 58) | MCI APOE4 negative (n = 48) |

All dementia (n = 50) | Dementia APOE4 positive (n = 36) | Dementia APOE4 negative (n = 14) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma TG/HDL | Faster | Faster | N.S | Faster | Faster | N.S |

| Plasma ApoA1 | Faster | Faster | Faster | Faster | Faster | Faster |

| CSF ApoA1 | Slower | Faster | N.S | N.S | Faster | N.S |

Faster: Higher baseline analyte levels relate to faster progression in one or more of the three cognitive scores: MMSE, CDR-SB, LM

Slower: Higher baseline analyte levels relate to slower progression in one or more of the three cognitive scores: MMSE, CDR-SB, LM

N.S Non-significant results

Among the MCI APOE ε4 carriers, higher plasma TG/HDL-C had a faster rate of decline in MMSE and CDR-SB. Among both MCI APOE ε4 non-carriers and carriers, higher plasma ApoA1 had a faster rate of decline in MMSE (Tables 6 and 7). Higher plasma ApoA1 in MCI APOE ε4 non-carriers alone had a faster rate of decline in LM scores (β − 0.60 [95% CI, − 0.87 to − 0.33], p < 0.001). Higher CSF ApoA1 in MCI APOE ε4 carriers also had a faster rate of decline in CDR-SB (β 0.22 [95% CI, 0.06 to 0.38], p = 0.008).

Table 7.

Linear mixed model results of the MCI and dementia groups stratified by APOE ε4 status

| MCI group | Dementia group | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APOEε4 positive (n = 58) | APOEε4 negative (n = 48) | APOEε4 positive (n = 36) | APOEε4 negative (n = 14) | |||||

| Effect | Slope (95% CI) | p-value | Slope (95% CI) | p-value | Slope (95% CI) | p-value | Slope (95% CI) | p-value |

| MMSE | ||||||||

| CSF ApoA1 | − 0.059 (0.302, 0.183) | 0.63 | 0.233 (− 0.024, 0.489) | 0.075 | − 1.029 (− 1.950, − 0.108) | 0.029 | 1.078 (− 0.205, 2.361) | 0.097 |

| Plasma ApoA1 | − 0.798 (− 1.258, − 0.339) | < 0.001 | − 0.474 (− 0.740, − 0.209) | < 0.001 | − 1.715 (− 3.285, − 0.146) | 0.033 | − 0.794 (− 3.923, 2.336) | 0.61 |

| Plasma TG/HDL | − 0.327 (− 0.562, − 0.093) | 0.006 | − 0.044 (− 0.173, 0.084) | 0.50 | − 0.559 (− 1.279, 0.162) | 0.13 | 0.960 (− 1.045, 2.965) | 0.34 |

| CDR-SB | ||||||||

| CSF ApoA1 | 0.220 (0.057, 0.383) | 0.008 | 0.076 (− 0.113, 0.264) | 0.43 | 0.137 (− 0.451, 0.725) | 0.64 | − 0.474 (− 1.245, 0.297) | 0.22 |

| Plasma ApoA1 | 0.518 (0.199, 0.838) | 0.002 | − 0.032 (− 0.229, 0.164) | 0.75 | 0.656 (− 0.346, 1.658) | 0.19 | 0.729 (− 1.151, 2.609) | 0.44 |

| TG/HDL | 0.287 (0.126, 0.448) | < 0.001 | 0.057 (− 0.038, 0.152) | 0.24 | 0.580 (0.120, 1.040) | 0.014 | − 0.112 (− 1.316, 1.093) | 0.85 |

| LM | ||||||||

| CSF ApoA1 | 0.017 (− 0.156, 0.190) | 0.84 | 0.093 (− 0.163, 0.350) | 0.47 | 0.042 (− 0.282, 0.366) | 0.79 | 0.613 (− 0.008, 1.234) | 0.053 |

| Plasma ApoA1 | 0.220 (− 0.108, 0.549) | 0.19 | − 0.598 (− 0.866, − 0.330) | < 0.001 | 0.068 (− 0.479, 0.615) | 0.80 | − 2.753 (− 4.268, − 1.239) | < 0.001 |

| Plasma TG/HDL | 0.125 (− 0.044, 0.293) | 0.15 | 0.002 (− 0.127, 0.130) | 0.98 | 0.142 (− 0.117, 0.402) | 0.28 | − 0.548 (− 1.518, 0.423) | 0.26 |

MMSE Mini-Mental Status Exam score, CDR-SB Clinical Dementia Rating Scale–Sum of Boxes score, LM Logical memory delayed recall score. Positive slope notes faster progression CDR-SB, negative slope notes faster progression in MMSE and LM

Among dementia APOE ε4 carriers, higher plasma TG/HDL-C had a faster rate of decline in CDR-SB and higher plasma ApoA1 had a faster rate of decline in MMSE. Higher plasma ApoA1 in dementia APOE ε4 non-carriers also related to faster decline in LM scores (β − 2.75 [95% CI, − 4.27 to − 1.24], p < 0.001). Among dementia APOE ε4 carriers, higher CSF ApoA1 also had a faster rate of decline in MMSE (β − 1.03 [95% CI, − 1.95 to − 0.11], p = 0.029).

Exploratory inflammatory analyte analysis

In MCI patients, after FDR correction, (a) plasma TG/HDL ratio was positively correlated to CSF (CRP, VCAM1) and plasma (C3, Fibrinogen, ferritin, IL-16) and negatively correlated to plasma (IL-13, IL-3), (b) plasma ApoA1 negatively correlated to CSF (AAT, CRP, VCAM1) and plasma (B2M, Ferritin) and positively correlated to plasma (IL-13, IL-3), and (c) CSF ApoA1 positively correlated to CSF (A2M, AAT, B2M, CRP, CCL2, ICAM1, IL-16, IL-3, IL-6r, IL-8, MMIF, PAI1, TIMP1, VCAM1, VEGF, vWF) but CSF ApoA1 did not correlate to plasma inflammation markers measured (Supplementary table 1).

In dementia patients, after FDR correction, (a) both plasma TG/HDL ratio and plasma ApoA1 were not correlated to CSF inflammatory analytes but negatively correlated to plasma (IL-3), but plasma TG/HDL positively correlated to plasma (C3, CCL11) and (b) CSF ApoA1 positively correlated to CSF (A2M, AAT, B2M, CRP, ICAM1, IL-16, IL-3, IL-8, MMP2, PAI1, TIMP1, VCAM1, VEGF, vWF) and negatively correlated to plasma (IL-3) (Supplementary table 2).

Among both MCI and dementia groups, the top hit among the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways [36] for CSFApoA1 (analyte count 7, P < 0.0001) was the advanced glycation end products(AGE)-receptors for AGE (RAGE) signaling pathway in diabetic complications (KEGG hsa04933). There were not enough inflammatory analytes correlated to TG/HDL and plasma APOA1 for pathway analysis.

Discussion

This study examined longitudinal cognitive outcomes in 156 MCI and AD dementia participants from the ADNI cohort. Our results indicate that elevated biomarkers of metabolic syndrome, higher plasma TG/HDL-C ratios, and plasma ApoA1 levels had a faster cognitive and functional rate of decline in both MCI and AD dementia participants. The results for plasma ApoA1 were significant for both APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers in the MCI and dementia groups for at least one of the three cognitive measures tested (MMSE, CDR-SB, and LM). Notably, CSF and plasma ApoA1 levels show opposite directional correlations with CSF biomarkers of BBB integrity and inflammation markers. CSF ApoA1, but not plasma ApoA1, positively correlates with CSF VCAM1 and CSF ICAM1, regardless of APOE ε4 status and inflammation markers of AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications. We have also previously reported that plasma ApoA1 is positively correlated with CSF t-tau and p-tau, while CSF ApoA1 is negatively correlated with both biomarkers [32]. These results together suggest that plasma and CNS ApoA1 levels are likely differentially modulated in relation to BBB and inflammatory biomarker changes. The clinical implication of this physiological difference between the plasma and CNS ApoA1 pools was noted in the MCI group, where higher plasma ApoA1 was associated with rapid decline in MMSE and LM scores, whereas lower CSF ApoA1 was associated with rapid decline in MMSE scores.

High plasma TG/HDL-C ratios are related to metabolic syndrome [6] and insulin resistance [9]. Insulin resistance can alter systemic lipid metabolism and induce endothelial dysfunction, which together contributes to atherosclerotic plaque formation, altered signal transduction, and delivery of substrates to the myocardium, as noted in coronary disease [7, 37]. Low TG/HDL ratios have been associated with higher scores in memory performance among elderly subjects (> 80 years) [38]. Plasma levels of TG and HDL-C have not been shown to significantly differ between AD dementia, MCI, and healthy controls in a recent meta-analysis [39], which is consistent with the results of the TG/HDL ratio in the current study. Among normal cognition subjects, TG levels correlate with longitudinal cognitive outcomes differently based on the age group examined [40], while high HDL-C levels have been associated with a significantly decreased risk of AD, with a few exceptions [41]. However, no prior studies have evaluated the association of the TG/HDL-C ratio with the longitudinal rate of cognitive and functional decline in MCI and AD dementia, as was performed in the current study. Among MCI subjects in this study, a 4 × difference in the TG/HDL-C ratio relates to a 1/2 point faster progression in MMSE score per year.

Endothelial BBB changes have been noted in AD-related cognitive deficits [42]. Soluble CSF VCAM1 and ICAM1 levels, which reflect changes in the endothelial layer of the BBB, have been correlated with CNS inflammatory changes [43], while in the periphery, VCAM1, and ICAM1 are upregulated in hypercholesterolemia and associated with early atherogenic lesions [44]. Among CNS diseases, CSF levels of VCAM1 and ICAM1 have been noted to correlate more strongly with disease-related outcomes than plasma levels [45, 46]. Taken together, the CSF and plasma levels of ICAM1 and VCAM1 may reflect different pathophysiological processes, with CSF levels of VCAM1 and ICAM1 suggesting BBB-related endothelial damage, and their plasma levels noting peripheral lipidogenic metabolism and atherogenic changes.

In the periphery, ApoA1 is also reported to modulate intestinal homeostasis and microbiota composition, and ApoA1 deficiency-driven dysbiosis may contribute to inflammation or predispose to atherosclerosis development [47], which supports potentially different pathophysiological roles for plasma and CNS ApoA1 pools in AD dementia. Consistent with this, in the current study, unlike the positive correlations between CSF ApoA1 and CSF BBB and inflammation biomarkers, we did not observe significant positive correlations between plasma ApoA1 and CSF BBB and inflammation biomarkers. This would suggest that plasma ApoA1 impact on cognitive outcomes is less likely related to CNS inflammatory and endothelial changes, in contrast to CSF ApoA1.

In AD animal models, over-expression of ApoA1 has been noted to slow the development of age-related learning and memory deficits, despite continued amyloid β deposition, and to associate with decreased neuroinflammation [20]. ApoA1 prevents the formation of Aβ42 aggregates and decreases Aβ42 toxicity in primary brain cells [19]. Consistent with these findings, our results show that higher CSF ApoA1 is related to a slower cognitive decline among the MCI participants.

Analysis of MCI and dementia group cognitive outcomes by APOE ε4 status revealed that higher CSF ApoA1 levels in APOE ε4 carriers had a more rapid clinical progression. This analysis was necessarily limited by sample size, so these results require additional research. However, similar findings among APOE ε4 carriers with subjective cognitive impairment and higher CSF ApoA1 have been associated with an increased risk of clinical progression toward AD [26].

One possibility for the lower CSF ApoA1 in the whole MCI group being associated with the rapid decline in MMSE, whereas a higher CSF ApoA1 among APOE ε4 carriers related to a more rapid clinical progression could be that there is a compensatory upregulation in CSF ApoA1, as a protective factor in the face of enhanced neurodegeneration or cellular stressors, as is noted for some other cell-protective inflammatory analytes [48]. The positive correlation noted in this study between CSF ApoA1 and CSF inflammation markers of AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetes is also consistent with this. If validated, the association of CSF ApoA1 with rapid clinical progression among APOE ε4 carriers and its positive correlation with inflammation biomarkers of AGE-RAGE signaling would not be directly causal.

In both MCI and dementia stages of AD, the levels of plasma ApoA1 are decreased compared to cognitive normal subjects in most studies, with few exceptions, while CSF ApoA1 is reported as unchanged or decreased between disease stages across different studies [16]. The MCI group in the current study had higher plasma ApoA1 levels than the Dementia group. In both MCI and dementia groups, higher plasma ApoA1 was associated with faster progression in MMSE and CDR-SB. In the Amsterdam Dementia Cohort, no significant associations between either CSF or plasma ApoA1 and cognitive decline were found among MCI participants, but the trend was in a similar direction [26]. In categorical analyses limited to normal cognition elders converting to dementia over 2 years in the Sydney Memory and Ageing study, lower plasma ApoA1 levels were associated with an increased risk of dementia [49]. One prospect that has been raised to explain these discrepant results in ApoA1 is that ApoA1, like other neuroinflammatory analytes (sTREM2 and sTNFR2) [48], could increase in the early preclinical phase of AD with an increasing rate of neuropathology burden. Yet as the disease progresses to the clinical symptomatic phase of AD, there could be a decrease in ApoA1 levels when neuropathology levels are not rapidly changing, resulting in differing clinical and imaging outcomes for ApoA1 levels depending on the stage of AD studied [14, 26]. In addition, the frequency of medical co-morbidities including differences in insulin resistance, obesity, lipid profile-modifying medications, racial differences, and relative numbers of APOE ε4 carriers may impact differences in results between cohorts. Methodological differences across studies (categorical outcomes versus continuous outcomes as in the current study) could be another reason for differences between studies. Differences in ApoA1 effects between studies could also be a harbinger suggesting that any future therapeutic benefit of modifying ApoA1 levels and the TG/HDL-C ratio to improve cognitive outcomes could differ based on the specific population targeted: normal cognition elderly, MCI, and AD dementia stages and, likely, between other subpopulations, e.g., based on insulin resistance or APOE ε4 status. Targeting ApoA1 levels and the TG/HDL-C ratio by diet and/or medication options in these clinical subjects warrants future studies.

Limitations

The current study is unique in evaluating plasma TG/HDL-C ratio and both CSF and plasma levels of ApoA1, along with key plasma and CSF BBB and inflammation biomarkers, to clarify the potential pathophysiological role of TG/HDL-C and ApoA1 in the CNS versus periphery in MCI and AD dementia stages. Additional evaluation of cognitive normal subjects and preclinical AD is needed to better understand the implications of these results across all stages of AD. However, this analysis could not be meaningfully expanded to include cognitively normal subjects in the ADNI cohort due to the small size of analysis groups when categorized by their amyloid- and tau-positive biomarkers and APOA1 data. The current results are among a well-characterized cohort with AD biomarkers, and key metabolic syndrome related to medical history. The analysis also accounted for BMI and the use of lipid-modifying medications; however, the effect of other medication interactions and diet on lipid metabolism on the results cannot be entirely ruled out. Another limitation is that the effects of exercise, co-existing inflammatory diseases, biomarkers of diabetes, and cardiovascular risk could not be evaluated in the current study. These interacting factors are worthy of further study. Although the statistical significance level of p < 0.05 is modest, additional sensitivity analyses corroborate the robustness of these effects.

The current results are likely generalizable to MCI and AD dementia subjects without severe metabolic syndrome in a longitudinal clinical cohort. However, given that the ADNI cohort is predominantly White with a higher level of education, there is still a need for replication studies of these results among other racial and ethnic cohorts with diverse educational and socioeconomic backgrounds. In addition, subjects with mixed dementia pathology and concomitant vascular comorbidities constitute a significant proportion of dementia subjects in the community [50] and the significance of these results among them is unclear.

Conclusions

Biomarkers of metabolic syndrome relate to rate of cognitive decline even after controlling for BMI in MCI and dementia individuals. CSF and plasma levels of ApoA1 differentially associate with clinical outcomes in MCI and AD dementia. Plasma levels of ApoA1 and the TG/HDL-C ratio appear to be promising prognostic markers for the rate of cognitive decline in MCI and AD dementia subjects and their therapeutic modification by diet and medication options in these clinical subjects is likely to be of high future interest. These results need additional replication in multiethnic cohorts.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Supplementary material

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table 1. Associations between TG/HDL, APOA1 and AD and inflammatory biomarkers in MCI patients

Additional file 3: Supplementary Table 2. Associations between TG/HDL, APOA1 and AD and inflammatory biomarkers in Dementia patients

Acknowledgements

John Fredieu, PhD, Cleveland Clinic Neurological Institute helped edit the manuscript. He was not compensated for this contribution.

This study was supported by grants K23AG055685-01 (Pillai), US Department of Defense, AZ21003 (Pillai), 1P30 AG062428-01 and P30 AG072959 from the NIA (Pillai, Bekris, Leverenz), Keep Memory Alive Foundation, and by the Jane and Lee Seidman fund.

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data, but did not participate in the analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at:

https://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgment_List.pdf

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADNI

Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative

- ApoA1

Apolipoprotein A1

- BBB

Blood-brain barrier

- BMI

Body mass index

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CDR-SB

Clinical Dementia Rating–Sum of Boxes

- FDR

False discovery rate

- HDL

High-density lipoproteins

- ICAM

Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1

- LM

Logical memory delayed recall

- MMP9

Matrix metallopeptidase 9

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Exam

- MCI

Mild cognitive Impairment

- TG

Plasma triglyceride

- TG/HDL-C

Plasma triglyceride-to-HDL cholesterol

- VCAM1

Vascular cell adhesion protein 1

Authors’ contributions

Jagan Pillai obtained funding, design and conceptualized study, analyzed the data, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript for intellectual content. James Bena organized the data, analyzed the data and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. Lynn Bekris interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. Nandan Kodur literature review, interpreted the data and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. Takhar Kasumov interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. James Leverenz interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. Sangeeta Kashyap conceptualized study, interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

JAP: NIA K23AG055685-01, NIA 1P30 AG062428-01, P30 AG072959 and Keep Memory Alive Foundation, US Department of Defense, AZ210031.

JBL: NIA 1P30 AG062428-01, P30 AG072959 Jane and Lee Seidman fund.

Availability of data and materials

The ADNI data analyzed are available in the ADNI repository, http://adni.loni.usc.edu/.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ADNI study was approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of each participating site and was conducted in accordance with Federal Regulations. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in the ADNI study and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Jagan A. Pillai: (a) grant support from the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the Alzheimer Association, and the Keep Memory Alive Foundation, US Department of Defense; (b) received compensation for serving as a section editor for Springer Nature and a grant reviewer with the Department of Defense and Research Grants Council of Hong Kong.

James Bena: none.

Lynn Bekris: Grant support from the National Institutes of Health.

Nandan Kodur: none.

Takhar Kasumov: none.

James Leverenz: received (a) Scientific Advisory Board of Vaxxinity and (b) grant support from Biogen, GE Healthcare, and National Institutes of Health.

Sangeetha Kashyap: (a) Scientific advisory board of Fractyl Inc.; serves on the Medication Monitoring Committee for GI Dynamics; serves as Chief Medical Officer for Gila Therapeutics; (b) grant support from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Fractyl Inc., Ethicon 422 Endo-Surgery, and Covidien to Cleveland Clinic.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Huang PL. A comprehensive definition for metabolic syndrome. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2(5–6):231–7. doi: 10.1242/dmm.001180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xue M, Xu W, Ou YN, Cao XP, Tan MS, Tan L, Yu JT. Diabetes mellitus and risks of cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 144 prospective studies. Ageing Res Rev. 2019;55:100944. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2019.100944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atti AR, Valente S, Iodice A, Caramella I, Ferrari B, Albert U, Mandelli L, De Ronchi D. Metabolic syndrome, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;27(6):625–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.01.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabia S, Fayosse A, Dumurgier J, Schnitzler A, Empana JP, Ebmeier KP, Dugravot A, Kivimaki M, Singh-Manoux A. Association of ideal cardiovascular health at age 50 with incidence of dementia: 25 year follow-up of Whitehall II cohort study. BMJ. 2019;366:l4414. Epub 2019/08/09 10.1136/bmj.l4414 PubMed PMID: 31391187; PMCID: PMC6664261 at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare no support from any organisation for the submitted work other than the grants reported in the funding section above; no financial relationships with any organisation that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Salazar MR, Carbajal HA, Espeche WG, Aizpurua M, Maciel PM, Reaven GM. Identification of cardiometabolic risk: visceral adiposity index versus triglyceride/HDL cholesterol ratio. Am J Med. 2014;127(2):152–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nie G, Hou S, Zhang M, Peng W. High TG/HDL ratio suggests a higher risk of metabolic syndrome among an elderly Chinese population: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):e041519. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.da Luz PL, Favarato D, Faria-Neto JR, Jr, Lemos P, Chagas AC. High ratio of triglycerides to HDL-cholesterol predicts extensive coronary disease. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2008;63(4):427–32. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322008000400003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li C, Ford ES, Meng YX, Mokdad AH, Reaven GM. Does the association of the triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio with fasting serum insulin differ by race/ethnicity? Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2008;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McLaughlin T, Abbasi F, Cheal K, Chu J, Lamendola C, Reaven G. Use of metabolic markers to identify overweight individuals who are insulin resistant. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(10):802–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernath MM, Bhattacharyya S, Nho K, Barupal DK, Fiehn O, Baillie R, Risacher SL, Arnold M, Jacobson T, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Weiner MW, Doraiswamy PM, Kaddurah-Daouk R, Saykin AJ, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging I. Alzheimer's Disease Metabolomics C Serum triglycerides in Alzheimer disease: Relation to neuroimaging and CSF biomarkers. Neurology. 2020;94(20):e2088–e98. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ostergaard SD, Mukherjee S, Sharp SJ, Proitsi P, Lotta LA, Day F, Perry JR, Boehme KL, Walter S, Kauwe JS, Gibbons LE, Alzheimer's Disease Genetics C. Consortium G. Consortium EP-I. Larson EB, Powell JF, Langenberg C, Crane PK, Wareham NJ, Scott RA. Associations between potentially modifiable risk factors and Alzheimer disease: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 2015;12(6):e1001841; discussion e. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagga K, Gustavsson AM, Stomrud E, Lindqvist D, van Westen D, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Melander O, Hansson O. Increased midlife triglycerides predict brain beta-amyloid and tau pathology 20 years later. Neurology. 2018;90(1):e73–e81. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi HJ, Byun MS, Yi D, Choe YM, Sohn BK, Baek HW, Lee JH, Kim HJ, Han JY, Yoon EJ, Kim YK, Woo JI, Lee DY. Association between serum triglycerides and cerebral amyloidosis in cognitively normal elderly. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24(8):604–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willette AA, Modanlo N, Kapogiannis D, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging I Insulin resistance predicts medial temporal hypermetabolism in mild cognitive impairment conversion to Alzheimer disease. Diabetes. 2015;64(6):1933–40. doi: 10.2337/db14-1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helbecque N, Codron V, Cottel D, Amouyel P. An apolipoprotein A-I gene promoter polymorphism associated with cognitive decline, but not with Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;25(2):97–102. doi: 10.1159/000112176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Endres K. Apolipoprotein A1, the neglected relative of Apolipoprotein E and its potential role in Alzheimer's disease. Neural Regen Res. 2021;16(11):2141–8. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.310669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Florvall G, Basu S, Larsson A. Apolipoprotein A1 is a stronger prognostic marker than are HDL and LDL cholesterol for cardiovascular disease and mortality in elderly men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(12):1262–6. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.12.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhatia M, Howard SC, Clark TG, Neale R, Qizilbash N, Murphy MF, Rothwell PM. Apolipoproteins as predictors of ischaemic stroke in patients with a previous transient ischaemic attack. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;21(5–6):323–8. doi: 10.1159/000091537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lefterov I, Fitz NF, Cronican AA, Fogg A, Lefterov P, Kodali R, Wetzel R, Koldamova R. Apolipoprotein A-I deficiency increases cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cognitive deficits in APP/PS1DeltaE9 mice. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(47):36945–36957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.127738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lewis TL, Cao D, Lu H, Mans RA, Su YR, Jungbauer L, Linton MF, Fazio S, LaDu MJ, Li L. Overexpression of human apolipoprotein A-I preserves cognitive function and attenuates neuroinflammation and cerebral amyloid angiopathy in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(47):36958–68. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.127829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reed B, Villeneuve S, Mack W, DeCarli C, Chui HC, Jagust W. Associations between serum cholesterol levels and cerebral amyloidosis. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(2):195–200. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.5390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merched A, Xia Y, Visvikis S, Serot JM, Siest G. Decreased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and serum apolipoprotein AI concentrations are highly correlated with the severity of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21(1):27–30. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(99)00103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saczynski JS, White L, Peila RL, Rodriguez BL, Launer LJ. The relation between apolipoprotein A-I and dementia: the Honolulu-Asia aging study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(9):985–992. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reynolds CA, Gatz M, Prince JA, Berg S, Pedersen NL. Serum lipid levels and cognitive change in late life. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(3):501–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02739.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tynkkynen J, Hernesniemi JA, Laatikainen T, Havulinna AS, Sundvall J, Leiviska J, Salo P, Salomaa V. Apolipoproteins and HDL cholesterol do not associate with the risk of future dementia and Alzheimer's disease: the National Finnish population study (FINRISK) Age (Dordr) 2016;38(5–6):465–73. doi: 10.1007/s11357-016-9950-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slot RE, Van Harten AC, Kester MI, Jongbloed W, Bouwman FH, Teunissen CE, Scheltens P, Veerhuis R, van der Flier WM. Apolipoprotein A1 in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma and progression to Alzheimer's disease in non-demented elderly. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;56(2):687–697. doi: 10.3233/JAD-151068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vitali C, Wellington CL, Calabresi L. HDL and cholesterol handling in the brain. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;103(3):405–13. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stukas S, May S, Wilkinson A, Chan J, Donkin J, Wellington CL. The LXR agonist GW3965 increases apoA-I protein levels in the central nervous system independent of ABCA1. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821(3):536–546. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sweeney MD, Sagare AP, Zlokovic BV. Blood-brain barrier breakdown in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(3):133–50. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaw LM, Hansson O, Manuilova E, Masters CL, Doecke JD, Li QX, Rutz S, Widmann M, Leinenbach A, Blennow K. Method comparison study of the Elecsys(R) beta-Amyloid (1–42) CSF assay versus comparator assays and LC-MS/MS. Clin Biochem. 2019;72:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2019.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ewers M, Franzmeier N, Suarez-Calvet M, Morenas-Rodriguez E, Caballero MAA, Kleinberger G, Piccio L, Cruchaga C, Deming Y, Dichgans M, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Weiner MW, Haass C, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging I Increased soluble TREM2 in cerebrospinal fluid is associated with reduced cognitive and clinical decline in Alzheimer's disease. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11(507):6221. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aav6221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pillai JA, Maxwell S, Bena J, Bekris LM, Rao SM, Chance M, Lamb BT, Leverenz JBI, Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging I Key inflammatory pathway activations in the MCI stage of Alzheimer's disease. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019;6(7):1248–62. doi: 10.1002/acn3.50827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wechsler D. WAIS-R manual : Wechsler adult intelligence scale - revised. San Antonio: Psychological Corp. : Harcourt Brace jovanovich; 1981.

- 36.Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D457–62. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ormazabal V, Nair S, Elfeky O, Aguayo C, Salomon C, Zuniga FA. Association between insulin resistance and the development of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):122. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0762-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katsumata Y, Todoriki H, Higashiuesato Y, Yasura S, Ohya Y, Willcox DC, Dodge HH. Very old adults with better memory function have higher low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and lower triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratios: KOCOA Project. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;34(1):273–9. doi: 10.3233/JAD-121138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y, Zhong X, Shen J, Jiao L, Tong J, Zhao W, Du K, Gong S, Liu M, Wei M. Elevated serum TC and LDL-C levels in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment: A meta-analysis study. Brain Res. 2020;1727:146554. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2019.146554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dimache AM, Salaru DL, Sascau R, Statescu C. The role of high triglycerides level in predicting cognitive impairment: a review of current evidence. Nutrients. 2021;13(6):2118. doi: 10.3390/nu13062118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hottman DA, Chernick D, Cheng S, Wang Z, Li L. HDL and cognition in neurodegenerative disorders. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;72 PT A:22–36. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nation DA, Sweeney MD, Montagne A, Sagare AP, D'Orazio LM, Pachicano M, Sepehrband F, Nelson AR, Buennagel DP, Harrington MG, Benzinger TLS, Fagan AM, Ringman JM, Schneider LS, Morris JC, Chui HC, Law M, Toga AW, Zlokovic BV. Blood-brain barrier breakdown is an early biomarker of human cognitive dysfunction. Nat Med. 2019;25(2):270–6. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0297-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steiner O, Coisne C, Cecchelli R, Boscacci R, Deutsch U, Engelhardt B, Lyck R. Differential roles for endothelial ICAM-1, ICAM-2, and VCAM-1 in shear-resistant T cell arrest, polarization, and directed crawling on blood-brain barrier endothelium. J Immunol. 2010;185(8):4846–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakashima Y, Raines EW, Plump AS, Breslow JL, Ross R. Upregulation of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 at atherosclerosis-prone sites on the endothelium in the ApoE-deficient mouse. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18(5):842–51. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.5.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kraus J, Gerriets T, Leis S, Stolz E, Oschmann P, Heckmann JG. Time course of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 in CSF in patients with basal ganglia haemorrhage. Acta Neurol Scand. 2007;116(1):49–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brodovitch A, Boucraut J, Delmont E, Parlanti A, Grapperon AM, Attarian S, Verschueren A. Combination of serum and CSF neurofilament-light and neuroinflammatory biomarkers to evaluate ALS. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):703. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80370-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yun KE, Kim J, Kim MH, Park E, Kim HL, Chang Y, Ryu S, Kim HN. Major Lipids, Apolipoproteins, and Alterations of Gut Microbiota. J Clin Med. 2020;9(5):1589. doi: 10.3390/jcm9051589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pillai JA, Khrestian M, Bena J, Leverenz JB, Bekris LM. Temporal ordering of inflammatory analytes sTNFR2 and sTREM2 in relation to Alzheimer's disease biomarkers and clinical outcomes. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:676744. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.676744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song F, Poljak A, Crawford J, Kochan NA, Wen W, Cameron B, Lux O, Brodaty H, Mather K, Smythe GA, Sachdev PS. Plasma apolipoprotein levels are associated with cognitive status and decline in a community cohort of older individuals. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e34078. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Langa KM, Foster NL, Larson EB. Mixed dementia: emerging concepts and therapeutic implications. JAMA. 2004;292(23):2901–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.23.2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Supplementary material

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table 1. Associations between TG/HDL, APOA1 and AD and inflammatory biomarkers in MCI patients

Additional file 3: Supplementary Table 2. Associations between TG/HDL, APOA1 and AD and inflammatory biomarkers in Dementia patients

Data Availability Statement

The ADNI data analyzed are available in the ADNI repository, http://adni.loni.usc.edu/.