Abstract

Background

The definition of feedback in clinical education has shifted from information delivery to student-teacher dialogue. However, based on Hofstede's theory, countries with large power distance or a robust social hierarchy and collectivistic cultural dimensions can reduce the feedback dialogue to a minimum. Indonesia is classified in this group, with some Asian, African, Mediterranean, and Latin American countries. This study explores the interactional communication of feedback during clinical education in a hierarchical and collectivistic context.

Methods

The focused ethnographic approach was applied to the clinical rotation program in an Indonesian teaching hospital. Data sources included observations of feedback episodes during workplace-based assessments followed by interviews with clinical supervisors and students. The data were compiled within 16 weeks of observation in 7 groups of clinical departments, consisting of 28 field notes, audiotaped interviews including nine focus group discussions of students (N = 42), and seven in-depth interviews with clinical supervisors. Data were analyzed through transcription, coding, categorization, and thematic analysis using the symbolic interactionist perspective.

Results

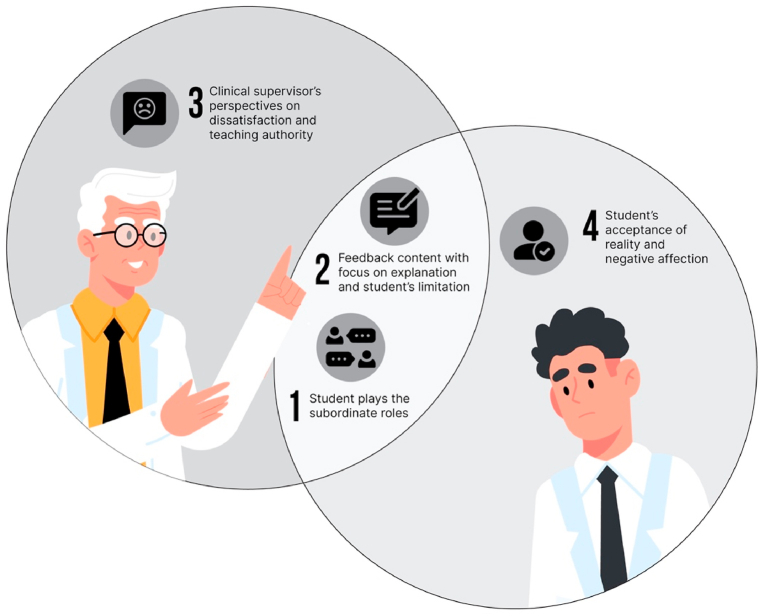

We identified four themes representing actual interactional communication and its ‘meaning’ or interpretation. The interactional communication in feedback is described in the first and second themes, such as 1) Students play the subordinate roles in a feedback dialogue; 2) The feedback content is focused on explanation and students' limitations. The third and fourth themes represent the clinical supervisors' and students' interpretation of their feedback experience, such as 3) Clinical supervisors' perspectives are mostly on dissatisfaction and teaching authority; 4) Students' acceptance of reality and negative affection.

Conclusions

This study shows that the social gap between students and clinical supervisors in Indonesia, and other countries in the same cultural classification, potentially causes communication barriers in the feedback dialogue. The adaptation of ‘feedback as a dialogue’ requires further effort and research to develop communication strategies in feedback that consider the national culture and context.

Keywords: Feedback, Clinical education, Communication, Culture, Dialogue

1. Introduction

In education, feedback is known as a strategy to help students reflect and enhance their learning [1]. Therefore, feedback in clinical education has a significant role in improving medical students' clinical skills [[1], [2], [3]]. Consequently, the quality of feedback in clinical education mirrors future healthcare performance and patient safety [4]. The importance of feedback in clinical education brings a large body of studies to changing the definition of feedback [[5], [6], [7]]. In the early 2000's, feedback was defined as information about student performance based on learning objectives and stated the future direction for improvement [3,8]. However, several studies highlight that feedback in clinical education often does not achieve its goals of driving students' learning and negatively impacts emotional aspects such as anxiety, frustration, or demotivation [6,7,9]. Responding to these problems, recent studies recommended the consideration of ‘educational alliance’ in the student-lecturer relationships to facilitate the feedback as a form of dialogue [[[10], [11], [12]]].

Through the implementation of dialogic feedback, studies found that the mechanism of feedback dialogue is challenging and complicated. The cultural factor strongly influences the student-lecturer relationship and their power disparity [9,[13], [14], [15], [16]]. The highlight of the clinical supervisor and students' relationship in feedback dialogue brings the socio-constructivist and sociocultural approaches to research trends [[17], [18], [19], [20], [21]]. The implication of these perspectives is narrowing the definition of feedback dialogue as a ‘social interaction’ and its cultural consequences.

The feedback mechanism emphasizes how clinical supervisors and students achieve their goals through effective interactional communication as a form of social interaction [9,13,18,[22], [23], [24]]. In line with this perspective, Ajjawi, and Bound bring one socio-constructivist approach called symbolic interactionism to explain the symbols of feedback dialogue and how individuals (clinical supervisor and student) construct meaning, identity, and social order through feedback experiences [9,13]. The symbols in feedback dialogue represent verbal and nonverbal aspects of correcting mistakes, providing information, and facilitating students' self-reflection [5,9,18,25,26]. The meaning of feedback interactions was constructed individually by the clinical supervisor and students. It showed the positive impact of feedback on learning improvement and the negative impact of socio-emotional factors on students [6,7,9,13].

The cultural influence in clinical supervisor-student relationships can represent the form of other social orders in its community, especially teacher-student and doctor-patient relationships [9]. In countries with a robust social hierarchy and a collectivist society, doctor-patient communication is primarily formed in the paternalistic style [27,28]. Corresponding with this fact, studies about the feedback in clinical education in this context represented a parent-children relationship. The feedback dialogue tended to be more instructive [20,21,29,30]. On the other hand, countries with low power distance and individualist or Western societies such as North-western (The US and West Europe) tend to have a more partnership relationship between doctor-patient, reflecting the collegial relationships between clinical supervisors and students or residents [9,13,18,25,[31], [32], [33]].

Previous studies from hierarchical and collectivistic cultures found that patients and students also want a more interactive relationship with their doctors and teachers as an ideal social interaction, similar to what the North-westerns desired [21,[27], [28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34]]. However, despite the interactional communication during feedback in clinical education in this context becoming more challenging, studies on the communication form in the feedback dialogue representing this culture are still limited.

Understanding feedback as dialogue brings new perspectives on the social interaction between clinical supervisor-student and its cultural influence [9,[13], [14], [15], [16]]. This new paradigm has been reflected in many studies using qualitative inquiry, such as ethnography and discourse analysis, predominantly in low power distance and individualist countries [13,18,[20], [21], [22]]. Whereas, studies in feedback during clinical education in the large power distance and collectivist culture mainly focused on student perspective and less on qualitative inquiry [20,21,35]. Therefore, exploring interactional communication in feedback during clinical education in a hierarchical and collectivist culture is essential.

Based on the perspective on sociocultural on feedback dialogue, we used qualitative inquiry with an ethnography approach to explore the research questions as follows: 1) What are the verbal and nonverbal symbols in the interactional communication between clinical supervisors and students during feedback, based on observation in clinical education within hierarchical and collectivist culture? and 2) How is the interactional communication in feedback interpreted by the clinical supervisors and students based on their perceptions?

2. Methods

Based on our research questions, purposively, we focused on the feedback episodes in clinical education in the hierarchical and collectivist culture context. We conducted the observations to describe the interactional communication and interviews to explore the clinical supervisor's and student's perceptions of their feedback experience.

2.1. Context of this study

This study was focused on the feedback during Workplace-based assessment (WPBA) or in the clinical setting in an Indonesian teaching hospital. The WPBA is a group of assessment methods that has the elements such as the observation of students' performance in a real clinical setting and relevant feedback to improve their clinical performance. Therefore, WPBA was based on the formative assessment approach [4]. In the context of this study, the WPBA was done in various methods such as mini Clinical Examination (mini-CEX), Case-based Discussion (CBD), and Direct Observation of Procedural Skills (DOPS) [4].

The Indonesian medical educational phase consists of the undergraduate program (3.5 years), continuing with a clinical education program (1.5 years). After graduating from medical school and passing the national board exam, students continue the one year of internship before starting their career as a general practitioner or continuing to hospital specialist programs [36]. The postgraduate program, including the recent family medicine program, is not compulsory. By this condition, about 1.5 years of clinical education in Indonesia-as the context of this study-was the only ‘real-patient setting’ that would shape the clinical professional competence as a general practitioner.

As a representative of a hierarchical and collectivist culture, this research was conducted in Indonesia, a multi-ethnic country classified as a large power-distance and collectivistic culture, together with other Asian, Arabian, African, and Latin American countries [31,37]. Few other studies from these continents have proven the social gaps that limit dialogue between doctor-patient and teacher-student [27,28,38]. The teaching hospital as the setting of this study is currently located in West Java, with rich Indonesian subcultures, native (Sundanese), and ethnic immigrants (Javanese, Batak, Padang, etc.) [39]. Manners of communities in West Java are characterized by polite manners with high respect for their ancestral heritage called ‘kasepuhan’. These manners are shown in their body language. For example, bow down as a sign of respect, using their thumb if direction intended, nod or look down while conversing with an older person [[38], [39], [40]]. Having a more specific context to draw the hierarchical setting, the context of this study was the private medical school on the army foundation. The clinical rotation takes place in the Army teaching hospital. Therefore, some clinical supervisors have a military background, while others are civilian doctors. As a private medical school, the educational approach of this institution follows the national curriculum, and all students are civilians.

2.2. The theoretical framework of the methodological approach

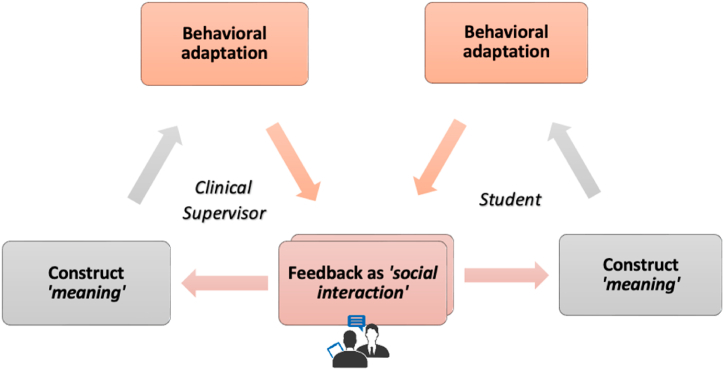

This study is grounded in one of the interpretive approaches in micro-sociology, symbolic interactionism. This approach arose from Mead in 1934 and was developed mainly by Blumer and many social researchers [41]. Blumer stated three principles of symbolic interactionism such as 1) Language, which contains significant symbols in linguistic and nonverbal as the source of meaning, 2) Meaning, which represents the subjective interpretation of people or things in social interaction; 3) Thinking, as self-reflective proses of individuals which can lead to modified behavior during interaction [13,41,42]. From this view, the feedback dialogue was analogically stated as a social interaction between clinical supervisors and students in clinical education (Fig. 1). Consequently, understanding feedback as social interaction should consider the cultural influence, especially in the clinical supervisor and students’ relationship. This study focuses on the hierarchies and collectivist cultural context that hypothetically influence the social relationship between clinical supervisors and students.

Fig. 1.

Feedback as ‘social interaction’ from symbolic interaction theory.

Fig. 1 shows the implication of symbolic interactions theory in feedback, represented in the cycle such as (1) The social interaction between clinical supervisor and student, consisting of symbols on their communication and cultural influence; (2) The construction of meaning from experienced interaction; (3) The self-reflective behavioral adaptation that influence the further interactions.

Underpinning the perspective of symbolic interaction within a specific cultural context, we use the Ethnography strategy as an interpretive inquiry that has a ‘good fit to describe the nature of interactions among cultural attributes. Culture consists of people's behavior, language, or other artifacts in the group or social world that are strongly captured in ethnography within the participant observations approach. The reflexivity in Ethnography strengthens the interpretation of natural processes in human interactions [37,43,44].

Considering the specific context of feedback episodes in clinical education, we used Focused Ethnography (FE). The main differences between FE and traditional ethnography involve the time limit, the focus problem in observation, and engagement with a specific group of participants [43,44]. Therefore, we narrowed the scope of observation in the interactional communication of feedback episodes in clinical education and interviews with students and clinical supervisors as ‘actors’ in feedback interaction.

2.3. Characteristics of participants

The purposive sampling was done to draw the large power distance and collectivist culture in an Indonesian military-based teaching hospital, located in West Java. We included the students with a minimum of six clinical rotation experiences and the clinical supervisors with five years minimum of clinical teaching experience. Four of seven clinical supervisors have a military background, and all students were civilians. Annually, the clinical teachers took the clinical teaching workshops to refresh their teaching skills, including how to provide feedback.

2.4. Data collection

According to the principle of qualitative inquiry, the data collection -such as observations and interviews-was conducted simultaneously with data analysis. The first author (SM) and one standardized observer conducted the participant observation simultaneously. As participant-observer, we engaged in all clinical education activities within 16 weeks, participated in the workplace-based assessment activity, and focused our observation on feedback episodes. Reaching the multiple reality, we collected the observation in different clinical settings and clinical rotations, as mentioned in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic and observation length.

| Clinical rotation | Setting | Students' Characteristics |

Clinical supervisor’ Characteristics |

Length of observation | Data collection |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical rotation experience | Male | Female | Gender | Teaching Experience | Background | Field Notes | Interviews | |||

| Pediatric | Ward and Polyclinic | 9th | 3 | 7 | Female | >10 years | Pediatricians, civil | 3 weeks | 6 feedback episodes | 2 FGDs, 1 in-depth interview |

| Ophthalmology | Polyclinic | 12th | 2 | 3 | Female | >5 years | Ophthalmologists, civil | 2 weeks | 4 feedback episodes | 1 FGDs, 1 in-depth interview |

| Head and Neck | Polyclinic | 13th | 1 | 3 | Male | >10 years | ENT doctor, military | 2 weeks | 3 feedback episodes | 1 FGDs, 1 in-depth interview |

| Psychiatry | Polyclinic | 10th | 1 | 3 | Male | >10 years | Psychiatrist, military | 2 weeks | 4 feedback episodes | 1 FGDs, 1 in-depth interview |

| Forensic | Clinical classroom | 13th | 2 | 3 | Male | >10 years | Forensic specialist, civil | 2 weeks | 5 feedback episodes | 1 FGDs, 1 in-depth interview |

| Internal Medicine | Ward, Clinical classroom | 8th | 1 | 4 | Male | >10 years | Internist, military | 3 weeks | 4 feedback episodes | 1 FGDs, 1 in-depth interview |

| Emergency | Clinical classroom | 11th | 3 | 6 | Male | >10 years | Neurosurgeon, military | 2 weeks | 2 feedback episodes | 2 FGDs, 1 in-depth interview |

The observation results were collected in field notes. At the end of each day's observation, we conducted a debriefing to discuss the findings and wrote the agreement in join field notes. However, we are concerned with the issues of reflexivity to reduce personal perspectives and biases in data collection and analysis, such as researchers' relationship with clinical supervisors and students and researchers' perception and interpretation [16,44,45]. Considering the researcher's relationships with respondents, two observers are undergraduate lecturers in the medical education department, professional colleague for clinical supervisors, and has no significant roles in clinical teaching and assessment that can affect students' biases.

To explore the clinical supervisors' and students’ interpretations of feedback interactions, SM and one standardized facilitator conducted nine semi-structured interviews using focus group discussions (FGDs) for the observed students (N = 42), ranging from 60 to 100 min. For clinical supervisors, SM facilitated the in-depth interviews of observed clinical supervisors ranging from 50 to 90 min. The leading questions for the interviews were similar for clinical supervisors and students, such as 1) “Could you describe your experience during feedback episodes?”; 2) “How do you feel about your feedback experience?”; and 3) “Does your experience meet your expectations?".

2.5. Data analysis

Ethnography data analysis describes the social setting, actors, and situation in a specific cultural context [46]. In this study, the analysis started from constructing the field notes of each observation on feedback episodes and continued with transcripts analysis of the results of the interviews. Concerning the reflexivity issue on researchers' perception and interpretation, the data from field notes and interviews were continually transcribed and coded by SM and one coder using the N-Vivo software. Three clinical supervisors and five students volunteered to do the member-checking procedures. SM and the co-authors (MC, YS, DM) conducted weekly discussions to agree on the codes and categorizations to reduce biases in the perception and interpretation of data. The data were saturated once we found no new codes and categories. To construct the themes, we used the analytical lens of symbolic interaction as described in Fig. 1 [42,45,47].

2.6. Ethical considerations

We obtained ethical approval for this study from the Medical and Health Research Ethics Committee (MHREC) at Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, number KE/FK/1391/EC/2020. We initiated the informed consent process with the clinical supervisors, followed by their clerkship students. We explained the study objectives, the mechanism of observation and interview, and the participants' rights to withdraw from the observation or interview at any time. Finally, informed consent was obtained from all participants to be observed during feedback episodes and conducted the interview. We have the consent to document the observation with field notes. We assured the confidentiality of information and anonymity of participants during analysis and publication.

3. Results

The participant observation was done in the workplace-based assessment session and focused our observation and field notes on the feedback interactional communication between clinical supervisors and students. From our data collection, most of the observed feedback episodes (21 from 28) were done in a particular space in the hospital ward, Polyclinic, and clinical classroom after the patient encounters or clinical case presentation. Seven from 28 feedback episodes in the hospital ward and Polyclinic were delivered in front of the patients during Mini CEX.

Based on the theoretical framework of symbolic interaction, we observed the symbols in interactional communication during feedback episodes. After observation, we enrich our data to capture the ‘meaning’ of the interaction from clinical supervisors' and students' perspectives, using FGDs and in-depth interviews.

We identified four themes representing the hierarchical and collectivist cultural influence on the interactional communication of feedback during clinical education. These themes answered the specific study questions about interaction's verbal and non-verbal symbols (themes 1 and 2) and the meaning or interpretations of the interactions (themes 3 and 4). The themes were as follows: (1) The Student plays the subordinate role in a feedback dialogue; (2) The feedback content focus on explanation and students' limitation; (3) The Clinical supervisor's perspectives on dissatisfaction and teaching authority; (4) Student's acceptance of reality and negative affection.

Explanation of Fig. 2. Interactional communication symbolizes students' role in a subordinate position (theme 1), related to the domination of explanation and students' limitation on feedback content (theme 2). The ‘meaning’ of interaction from clinical supervisors' perspective (theme 3). The ‘meaning’ of interaction from students' perspective (theme 4). The arrows illustrated the cycle of how symbols in interactional communication influence the meaning and vice versa.

Fig. 2.

The illustration of interrelated themes.

3.1. Student plays subordinate roles in a feedback dialogue

As symbols of the subordinate roles of students, we found unequal physical positions during feedback interactions. We noted (24 of 28) students' physical positions during feedback episodes were standing and clinical supervisors sitting. The quotation from our field notes represented the students' and clinical supervisors' positions during the interaction showed in Table 2. The thematic analysis results described in Table 5.

Table 2.

The example of field notes quotations’ interpretations.

| Field notes quotations | Interpretations | Codes |

|---|---|---|

|

Field notes code 08_Polyclinic Friday, 10 a.m. In the polyclinic room, there are two examiner tables, and five chairs, clinical supervisor (CS) sits in one of the examiner's chairs on the right side of the patient's chair. . … While examining the patient and receiving feedback, the student is standing, occasionally bending down and adjusting her position to examine the patient and listen to the CS's advice. |

Student standing while clinical supervisor sitting | The nonverbal symbol of student as subordinate |

|

Field notes code 02 _Polyclinic Thursday, 8.30 a.m. The student, a female, walked rashly through the Clinic. The CS has sat in his chair and is ready to call the patient. The student continued to bow down and said, “Good morning, doctor, pardon me, my name is K, and I have been scheduled mini-CEX for today”. The CS refused to have eye contact and pointed to the medical record without saying a word. The student took the medical record and said, “Pardon me, doctor”. The CS keep silent until the nurse comes and brings the patient to the Clinic. … … The CS finished the patient's examination about 40 min. The student did not have any exams that day. |

Students apologize without any verbal response from the clinical supervisor. Students need a chance to clarify the situation. |

The symbols of the student as subordinate The symbols of the power of the clinical supervisor |

Table 5.

The outline on thematic analysis of themes 1 and 2.

| The field notes interpretation |

Categories | Themes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical supervisors | Students | ||

| The clinical supervisor mostly sits during feedback episode | Students mostly stand during feedback episodes | The nonverbal (physical position) shows the power of the clinical supervisor in the social interaction. | Students' subordinate roles during interactional communication |

| Predominantly explanation, disproval, and judgment sentences | Predominantly apology and approval sentences | The verbal symbols show the power of clinical supervisors. | |

| Minimally approval sentences | Minimally explanation sentences | ||

| High to moderate intonation | Low to moderate intonation | The Nonverbal/ paralinguistic symbols of the higher position of clinical supervisor | |

| The content of explanation sentences is mostly a guidance | Apology and approval sentences showing students' acceptance of their limitation | The feedback conversation primarily explains the clinical skills | The feedback content focus on explanation and student limitation |

| The disproval and judgment sentences showed students' limitation | The content of disproval and judgment is mostly about students' limitations. | ||

| Minimum statement on “what went well” from students' performance | |||

Other linguistic symbols represent the subordinate roles of students identified in the clinical supervisors' verbal communication, mainly containing explanations, confirmations, and judgment sentences, followed by moderate to high intonation. Meanwhile, students' verbal communication primarily represents approval, apology, and a few explanatory sentences, with the non-verbal response mainly derived from low intonation. These findings are represented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The quantification of verbal and non-verbal coding.

| Participants | Verbal |

Apology | Approval | Confirmation | Explanation | Disapproval | Judgment | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonverbal | ||||||||

| Students | Low | 28 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 64 |

| Moderate | 16 | 24 | 14 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 76 | |

| Clinical supervisors | Moderate | 0 | 22 | 35 | 62 | 33 | 38 | 190 |

| High | 0 | 0 | 8 | 5 | 18 | 12 | 43 |

Students often used the ‘ask for permission to speak’ sentences that represent their polite behavior of students. Despite this, we recorded that some students had a chance to speak up, using the explanation sentences with moderate intonation. These findings are represented in Table 4, Table 5.

Table 4.

The examples of interpretations on feedback conversations in field notes.

| Field notes quotation in feedback episodes | Interpretation |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical supervisor | Student | Feedback content | |

|

Fieldnotes code 11_ Polyclinic Tuesday, 9.25 a.m. …. . the patient was still sitting in front of clinical supervisors (CS) and students (S). | |||

| CS: Okay, you were unstructured.. so the history-taking was unclear, right? |

Judgment (V) Confirmation(V) |

Information about limitation | |

| S : <silence> | Silence (NV) | ||

|

CS: You have to get a more profound exploration.. You didn't introduce yourself and didn't ask permission before the examination. You didn't explain what you would do to the patient. Then, you see, your examination, The Rinne and Webber test …. Hmm … <moderate tone> |

Explanation(V) Judgment(V) Moderate intonation (NV) |

Information about what needs to be improved | |

| CS: I think you won't be correct in the interpretation …..” <looking straight to the student > |

Judgment(V) Moderate intonation (NV) |

Information about limitation | |

| S : Pardon me, doc. I am sorry, doc.. <looking down, low tone> | Ask for permission(V) Apology (V) Low intonation (NV) |

||

|

Fieldnotes code 07_ Polyclinic Monday, 10.50 a.m. … … … The patient finished the examination and left the room. | |||

| CS: What was the diagnosis? | Confirmation (V) | Ask questions | |

| S: Pardon me, doc. It was a cataract | Ask for permission(V) Explanation(V) |

||

| CS: Okay, any reasons? | Approval (V) Confirmation (V) |

Ask questions | |

|

S: Pardon me, doctor. The patient has gradually reduced visual activity. <moderate tone> |

Ask for permission(V) Explanation(V) |

||

| CS: Will you decide on the classification also? You have to mention it clearly in your diagnosis. <moderate tone> | Confirmation (V) Explanation(V) |

Information about what needs to be improved | |

| S: Pardon me, doctor, it was an immature cataract since the shadow test was positive. | Ask for permission(V) Explanation(V) |

||

| CS: True.. but what about your shadow test examination back then? Did it right? | Approval (V) Confirmation (V) |

Ask questions | |

| S: Pardon me, doctor, I still have some mistakes, doc. <Moderate tone> | Ask for permission(V) Explanation(V |

||

| CS: See.. for conducting the test, you have to ensure the angle is correct, about 45°, for a clearer view. You have to do better in the next exam, okay? <Moderate tone, friendly facial expression> | Explanation (V) | Information about what needs to be improved Action plan |

|

4. The feedback content focus on explanation and students’ limitation

Based on our observations, we code the feedback conversation into the seven categories of effective feedback, such as 1) based on the observations in students’ performance 2) initiation of feedback; 3) what needs to be improved; 4)”what went well”, 5) compare to standard, 6) explanation or demonstration; 7) action plans [21].

All feedback episodes were based on clinical performance or case presentation and initiated by clinical supervisors. The feedback content predominantly involved correcting students' mistakes and directing and describing things that needed to be improved rather than explaining what went well.

4.1. Clinical supervisor's perspectives on dissatisfaction and teaching authority

Based on our categorization, the clinical supervisor has significant dissatisfaction caused by the gap in their expectations and real students' performance. This category is related to their perception of authority in teaching, represented in Table 6. Based on the observations, the clinical supervisors' disappointment reflects their strict behavior and other nonverbal symbols using high intonation (Table 3).

“… some of them were just silent, even 2/3 of them. I wonder how they could become clerkship students” (Clinical Supervisor _03)

" … they didn't prepare themselves well.." (Clinical Supervisor _07)

" … so, even though we have explained it, they don’t change …” (Clinical Supervisor_03)

“..Sometimes the feedback should be about threats, like, you have to do this or that if you want to pass this clinical rotation” (Clinical Supervisor_08)

Table 6.

The outline of thematic analysis on themes 3 and 4.

| Codes |

Categories |

Themes |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical supervisors' perspective | ||

| • Feeling Upset • Sad • Tired • Disappointed |

Dissatisfaction with student performance | Clinical supervisor's perspectives on dissatisfaction and teaching authority |

| • Repeated errors • Already directed • Below standard • Not as expected • Less preparation • Can not answer • No changes |

The gap between expectations and actual students' performance | |

| • Must be threatened • Must be strict • Must be scolded to change |

Authority in teaching | |

| Student's perspective | ||

| • Disappointed • Afraid • Confused • Threatened • Shy • Sad • Demotivated • Give up • Ignorance |

Negative affection and demotivation | Student's acceptance of reality and negative affection |

| • Detention • Firmness • Judgment • Authoritarian • Negative label • Humiliated • Always wrong |

Feeling inferior and consistently wrong | |

| •Just go with it • Accepting the situation • I kept that in mind |

The attitude of accepting reality | |

The quotes describe that the clinical supervisor mostly interpreted the students who tend to be “silent” as a symbol of the lack of preparation underlying their dissatisfaction. Strengthening their dominant behaviors, clinical supervisors perceived that they needed to be strict, speak in reproof, and threaten their students to make them learn.

4.2. Student's acceptance of reality and negative affection

The students perceived that many feedback experiences resulted in demotivation due to stress and fear, as described in Table 6. Students also convey that they could not consistently implement the clinical supervisor's feedback due to negative emotions such as sadness, anxiety, feeling unfair, and wanting to give up.

…. ., I feel like crying, I felt like.. never did anything right.” (Student_05.2)

" … that's the rules, the student is always wrong …” (Student_02.5)

Interestingly, the students tend to accept the clinical supervisor's attitude and perceive the conditions as “just go with it” or reasonable for them. The students still remember their ‘hard’ experiences with their negative feelings.

5. Discussions

Our study illustrated how Indonesians' hierarchical and collectivist culture influences interactional communication during feedback dialogue in clinical education. We identified four themes that answered the specific study questions about interaction's verbal and non-verbal symbols (themes 1 and 2) and the meaning of interactions (themes 3 and 4).

Corresponding to the symbolic interactionist framework, in the first theme, we identified the 'symbols' in feedback episodes that describe a higher power of clinical supervisors, reinforcing students' subordinate positions during the interaction. The physical position of the sitting clinical supervisor vs. the standing student is the symbol of power in non-verbal communication – comfort belongs to the honorable person – and represents the collectivist culture that avoids face-to-face or confrontative interaction [20,21,31]. Moreover, the clinical supervisor's domination of sentences and moderate to high intonation symbolized their authority. The students responded to clinical supervisors' linguistic symbols with the approval sentences with moderate to low intonations. These recognized ‘symbols’ reflect the character of collectivist and hierarchical culture, such as the authoritarian values in teaching and students who have high respect for their ‘guru’. Moreover, the large power distance consequently polarized the superior-subordinate relations, which are often created by superiors and maintained in social interaction [24,28,30,48,49]. Our findings also represent Hall's theory of high-context communication. This context is the same in Japan, China, Arab countries, and Latin America [50]. The high context culture emphasized nonverbal symbols and the implicit meaning of verbal communication. As a result, high-context messages are mostly not specific and less informative [50,51].

The inequality of power in the lecturer-student relationship was not a new phenomenon. However, in Hofstede's perspective, large power-distance countries tend to have more robust diversity in great-less power relationships [31]. The power gap is often created by superiors and maintained in social interactions. In a hierarchical culture, a large disparity is represented in every social setting, such as the child-parents, student-teacher, employee-manager, and doctor-patient relationships [28,[30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35], [36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52]]. Our findings are a ‘tip of the iceberg phenomenon’ representing the feedback dialogue in a large power distance and collectivist culture.

In the second theme, we describe the influence of the hierarchy and collectivist culture on the feedback content. We found the feedback conversations were predominantly in correcting students' mistakes and explanations or demonstrating clinical skills. Our results align with the previous studies in Indonesia that stated the clinical students valued feedback as instructive and mentioned their weaknesses, and generally were unidirectional [20,21,52]. The findings also represent the hierarchical and collectivist cultural consequences that tend to involve teacher-centered education, and the purpose of education is learning ‘how to do’ [28,53,54]. Unidirectional feedback potentially significantly impacts a student's future performance as a physician [55]. The lack of student engagement during feedback hinders the cognitive process of competency development. Besides, the experience in the feedback dialogue of clinical supervisor-student will unconsciously be role-modeled when students finally reach a higher position, such as in doctor-patient or inter-professional communications. The impact of unidirectional feedback, such as the lack of student competency, including their communication skills, is related to patient safety [55,56].

Following the communication symbols during feedback dialogue, we explored clinical supervisors' and students' interpretations or ‘meaning’ of their repeated feedback experience in the third and fourth themes. The clinical supervisors mostly perceived the gap between their expectations and student performance. Based on their perceptions of teaching authority, they often create strict behavior during feedback episodes captured in the first theme. Despite this, we found the clinical supervisors' behavior is influenced by students' performance and stated as ‘good students, good mood’. Studies show that emotional feedback from clinical supervisors tends to happen because they are worried about patient safety issues [57,58].

However, the students mostly perceived the reality acceptance shown as ‘students always wrong’ phrase and the emotions of guilt, fear, sadness, and the feeling of giving up. These emotional situations should be considered psychological barriers to feedback communication. Based on the psychosocial approach, our findings represent the emotional ‘blackmail’ in the student-lecturer relationship that creates a subordinate position based on fear, obligation, and guilt. Several studies found that negative emotions are related to the cognitive process, such as a self-concept built on failures and accomplishments, leading to low self-esteem [19,27,46,47]. In our context, students' clinical education experience significantly shapes their professional identity as future general practitioners. The lack of feedback and supervision in clinical education due to psychological or cultural barriers in feedback communication can be responsible for their future professionalism and patient safety.

Our interpretation reminds us that culture is not a ‘taken-for-granted’ element. Together with experienced communication symbols in verbal and non-verbal clues, the cultural perspective is constructed by individuals and re-created in their behavior through repeated interaction [[41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52]]. Therefore, to reach effective communication during feedback dialogue, we argued that the rooted and challenging step is to reconceptualize clinical supervisors' teaching approaches, such as from teacher to student-centered, from information providers to facilitate learning. Based on this fundamental paradigm change, the clinical supervisor will be able to reduce their ‘power’ during feedback dialogue. The reduction of authority or power in teaching is expected to become the ‘port the entre’ for students -as subordinate position-to have more ‘change to speak’ events during feedback dialogue.

This study evidenced the complex social process and psychological related to feedback dialogue. Based on the cultural influence, we highlighted the impact of the emotional aspect, both for clinical supervisors and students. Further study is recommended to explore emotional intelligence, such as self-awareness, self-motivation, self-regulation, empathy, and other psychological impacts from feedback dialogue.

In summary, our study is not intended to make a cultural distinction. Nevertheless, it is possible but very challenging to perform effective bidirectional feedback communication in a hierarchical and collectivist cultural context as desired by students in this context [34]. We illustrated how the hierarchy and collectivist culture impact a minimum dialogue, instructive feedback content, and essential emotional issues in the clinical supervisor and student relationship. The results of this study can be the ‘port of entry’ to adapt the feedback as a form of dialogue in the hierarchical and collectivist culture. Therefore, we suggest more participatory studies on how feedback dialogue can occur differently in a specific context, emphasizing the re-concept concerning the teaching and learning approach with the development of emotional intelligence and interpersonal communication skills.

This study has several limitations due to the low number of participants from the widely diverse subcultures of Indonesia. Therefore, we realize that the findings may not be generalized as from Indonesia. Further studies should follow regarding the sample size, the diverse community, and more global studies on different continents. This study confirms the qualitative findings and increases the trustworthiness. First, we triangulate the results by reflexivity approach through data collection and analysis by multiple observers, realities, and interpreters. Second, we used the established theoretical framework related to interactional communication and sociocultural factor. And third, we compared our results to the literature on feedback in clinical education from the similar and different cultural backgrounds.

6. Conclusions

The results illustrated the complexity of interactional communication during feedback in a clinical rotation in Indonesians' hierarchical and collectivist cultural context. We found themes representing the ‘higher’ position of clinical supervisors, responded by the students' subordinate role, and led to the feedback content that concentrates on the students' limitations and guidance. Further, we describe how clinical supervisors and students create meaning in their feedback interactions, such as the clinical supervisors' dissatisfaction with students' performance and authority in teaching. However, we identified the negative affection followed by acceptance of reality from the student's point of view. Therefore, we recommend further studies exploring how effective communication occurs in feedback dialogue within the hierarchical and collectivist culture.

Author contribution statement

conceived and designed the experiments =SM, YS, DM, MC.

performed the experiments= SM , MC.

Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data= SM.

analyzed and interpreted the data= SM.

wrote the paper= SM, YS, DM,MC.

Funding statement

This study was founded by the Indonesian Domestic Lecturer Excellence Scholarship from Indonesian Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education, number B/67/D.D3/KD/02.00/2019.

Data availability statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgment

In this study, we acknowledged all clinical supervisors and students from the study context for their contribution.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14263.

Contributor Information

Sylvia Mustika Sari, Email: sylvia.mustikasari@lecture.unjani.ac.id.

Yoyo Suhoyo, Email: yoyosuhoyo@ugm.ac.id.

Deddy Mulyana, Email: deddy.mulyana@unpad.ac.id.

Mora Claramita, Email: mora.claramita@ugm.ac.id.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Cantillon P., Sargeant J. Giving feedback in clinical settings. BMJ. 2008;337(7681):1292–1294. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Veloski J., Boex J.R., Grasberger M.J., Evans A., Wolfson D.W. Systematic review of the literature on assessment, feedback and physicians' clinical performance*: BEME Guide No. 7. Med. Teach. 2006;28(2):117–128. doi: 10.1080/01421590600622665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pelgrim E.A.M., Kramer A.W.M., Mokkink H.G.A., van der Vleuten C.P.M. The process of feedback in workplace-based assessment: organisation, delivery, continuity. Med. Educ. 2012;46(6):604–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norcini J.B.V. Workplace-based assessment as an educational tool: AMEE Guide No. 31. Med. Teach. 2007;29:855–871. doi: 10.1080/01421590701775453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teunissen P.W., Vleuten Van Der C.P.M. Broadening the scope of feedback to promote its relevance to workplace learning. Acad. Med. 2017;XX(X):1–4. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boud D., Molloy E. 2012. What Is The Problem With Feedback? Feed High Prof Educ Underst It Doing It Well; pp. 1–10. January 2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ajjawi R., Regehr G. When I say … feedback. Med. Educ. 2019;53(7):652–654. doi: 10.1111/medu.13746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hattie J., Timperley H. The power of feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 2007;77(1):81–112. doi: 10.3102/003465430298487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ajjawi R., Boud D. Examining the nature and effects of feedback dialogue. Assess Eval. High Educ. 2018;43(7):1106–1119. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1434128. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Telio S., Regehr G., Ajjawi R. Feedback and the educational alliance: examining credibility judgements and their consequences. Med. Educ. 2016;50(9):933–942. doi: 10.1111/medu.13063. http://10.0.4.87/medu.13063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Telio S., Ajjawi R., Regehr G. The “educational alliance” as a framework for reconceptualizing feedback in medical education. Acad. Med. 2015;90(5):609–614. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jackson D., Davison I., Adams R., Edordu A., Picton A. A systematic review of supervisory relationships in general practitioner training. Med. Educ. 2019;53(9):874–885. doi: 10.1111/medu.13897. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85065663633&doi=10.1111%2Fmedu.13897&partnerID=40&md5=180a6b883108dd837a7127f7ceffb40f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ajjawi R., Boud D. Researching feedback dialogue: an interactional analysis approach. Assess Eval. High Educ. 2017;42(2):252–265. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2015.1102863. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramani S. 2019. Enhancing Impact of Feedback through Transformation of Institutional Culture Subha Ramani Swinging the Pendulum from Recipes to Relationships. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramani Subha, Konings Karen D., Ginsburg Shiphra, Vleuten C.P. Meaningful feedback through a sociocultural lens.pdf. Med. Teach. 2019;September:1–11. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1656804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ramani S., Post S.E., Könings K., Mann K., Katz J.T., van der Vleuten C. It's just not the culture”: a qualitative study exploring residents' perceptions of the impact of institutional culture on feedback. Teach. Learn. Med. 2017;29(2):153–161. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2016.1244014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bing-You R., Hayes V., Palka T., Ford M., Trowbridge R. The art (and artifice) of seeking feedback: clerkship students' approaches to asking for feedback. Acad. Med. 2018;93(8):1218–1226. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002256. https://www.scopus.com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Esterhazy R., Damşa C. Unpacking the feedback process: an analysis of undergraduate students' interactional meaning-making of feedback comments. Stud. High Educ. 2019;44(2):260–274. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2017.1359249. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramani S., Könings K.D., Ginsburg S., van der Vleuten C.P.M. Twelve tips to promote a feedback culture with a growth mind-set: swinging the feedback pendulum from recipes to relationships. Med. Teach. 2019;41(6):625–631. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1432850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suhoyo Y., Van Hell E.A., Prihatiningsih T.S., Kuks J.B.M., Cohen-Schotanus J. Exploring cultural differences in feedback processes and perceived instructiveness during clerkships: replicating a Dutch study in Indonesia. Med. Teach. 2014;36(3):223–229. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.853117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suhoyo Y., Van Hell E.A., Kerdijk W., et al. Influence of feedback characteristics on perceived learning value of feedback in clerkships: does culture matter? BMC Med. Educ. 2017;17(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0904-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Me D., M van B. Stommel W., et al. Using conversation analysis to explore feedback on resident performance. Adv. Heal. Sci. Educ. Theo. Pract. 2019;24(3):577–594. doi: 10.1007/s10459-019-09887-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30941610/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rizan C., Elsey C., Lemon T., Grant A., Monrouxe L.V. Feedback in action within bedside teaching encounters: a video ethnographic study. Med. Educ. 2014;48(9):902–920. doi: 10.1111/medu.12498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blatt B., Confessore S., Kallenberg G., Greenberg L. Verbal interaction analysis: viewing feedback through a different lens. Teach. Learn. Med. 2008;20(4):329–333. doi: 10.1080/10401330802384789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rizan C., Elsey C., Lemon T., Grant A., Monrouxe L.V. Feedback in action within bedside teaching encounters: a video ethnographic study. Med. Educ. 2014;48(9):902–920. doi: 10.1111/medu.12498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adam L.A., Oranje J., Rich A.M., et al. Advancing dental education : feedback processes in the clinical learning environment. J. R Soc. New Zeal. 2019:1–14. doi: 10.1080/03036758.2019.1656650. 0(0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Claramita M., Utarini A., Soebono H., van Dalen J., van der Vleuten C. Doctor-patient communication in a Southeast Asian setting: the conflict between ideal and reality. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2011;16(1):69–80. doi: 10.1007/s10459-010-9242-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Claramita M., Nugraheni M.D.F., van Dalen J., van der Vleuten C. Doctor-patient communication in Southeast Asia: a different culture? Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2013;18(1):15–31. doi: 10.1007/s10459-012-9352-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilbur K., Driessen E.W., Scheele F., Teunissen P.W. Workplace-based assessment in cross-border Health professional education. Teach. Learn. Med. 2019:1–13. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2019.1637742. 0(0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nugraheny E., Claramita M., Rahayu G., Kumara A. Feedback in the nonshifting context of the midwifery clinical education in Indonesia: a mixed methods study. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2016;21(6):628. doi: 10.4103/1735-9066.197671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hofstede G. In: Culture Consequences. Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations. second ed. Thompson J.B., editor. Sage Publication; Thousand Oaks, California: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urquhart L.M., Ker J.S., Rees CE.x. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2018;23(1):159–186. doi: 10.1007/s10459-017-9781-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Møller J.E., Malling B.V. Workplace-based communication skills training in clinical departments: examining the role of collegial relations through positioning theory. Med. Teach. 2019;41(3):309–317. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1464647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Claramita M., Prabandari Y.S., Graber A., Scherpbier A.J.J. Challenges of communication skills transfer of medical students in the cultural context of Indonesia. Interdis. J. Prob. Learn. 2020;14(1):1–11. doi: 10.14434/ijpbl.v14i1.28594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sudarso S., Rahayu G.R., Suhoyo Y. How does feedback in mini-CEX affect students' learning response? Int. J. Med. Educ. 2016;7:407–413. doi: 10.5116/ijme.580b.363d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Indonesia. Law Number (No). 20 of. Medical Education; Jakarta: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hofstede G. Dimensionalizing cultures: the Hofstede model in context. Online Readings Psychol. Cult. 2011;2(1):1–18. doi: 10.9707/2307-0919.1014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mulyana D., Dida S., Suminar J.R., Indriani S.S. Communication barriers between medical practitioners and patients from medical practitioners' perspective. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Human. 2019;27(4):2797–2811. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nalan A.S. Everything about West Java: recognizing the dynamics of West Java cultural heritage. J ISBI. 2020;1(1):1–10. https://jurnal.isbi.ac.id/index.php/Prosiding/issue/view/139 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mulyana D. PT Remaja Rosdakarya; Bandung: 2012. Culture and Communication. An Indonesian Scholar's Perspective. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carter M.J., Fuller C. Symbols, meaning, and action: the past, present, and future of symbolic interactionism. Curr. Sociol. 2016;64(6):931–961. doi: 10.1177/0011392116638396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carter M.J., Fuller C. Sociopedia; 2015. Symbolic Interactionism. May 2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andreassen P., Christensen M.K., Møller J.E. Focused ethnography as an approach in medical education research. Med. Educ. 2020;54(4):296–302. doi: 10.1111/medu.14045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rashid M., Hodgson C.S., Luig T. Ten tips for conducting focused ethnography in medical education research. Med. Educ. Online. 2019;24(1) doi: 10.1080/10872981.2019.1624133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tan M., Zhu L., Wang X.-W., Tan K., MT. Wei Wang X. 2003. Symbolic Interactionist Ethnography: toward Congruence and Trustworthiness.http://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2003/377 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Creswell J.W. 16. second ed. 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aksan N., Kisac B., Aydin M., Demirbuken S. Symbolic interaction theory. Procedia - Soc Behav Sci. 2009;1(1):902–904. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2009.01.160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Claramita M., Susilo A.P., Kharismayekti M., van Dalen J., van der Vleuten C. Introducing a partnership doctor-patient communication guide for teachers in the culturally hierarchical context of Indonesia. Educ. Health Change Learn. Pract. 2013;26(3):147–155. doi: 10.4103/1357-6283.125989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mulyono I.K.A., Irawati S., Susilo A.P., Claramita M. Pharmacist-patient communication in Indonesia: the roter interaction analysis system (RIAS) in a socio-hierarchical context. Pharm. Educ. 2019;19(1):359–369. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mulyana D. In: Health and Therapeutic Communication: an Intercultural Perspective. Morse P., editor. 2016. (Bandung: PT Remaja Rosdakarya). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Littlejohn S.W., Foss K.A. tenth ed. Waveland Press,Inc. Long Grove; 2011. Theories of Human Communication. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Claramita M., Dalen J Van, Van Der Vleuten C.P.M. Doctors in a Southeast Asian country communicate sub-optimally regardless of patients' educational background. Patient Educ. Counsel. 2011;85(3):e169–e174. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tan J., Tengah C., Chong V.H., Liew A., Naing L. Workplace based assessment in an asian context: trainees' and trainers' perception of validity, reliability, feasibility, acceptability, and educational impact. J. Biomed. Educ. 2015;2015:1–8. doi: 10.1155/2015/615169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cultures Hofstede. Organization. 1991 doi: 10.1007/s11569-007-0005-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Myers K., Chou C.L. Collaborative and bidirectional feedback between students and clinical preceptors: promoting effective communication skills on Health care teams. J. Midwifery Wom. Health. 2016;61:22–27. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stevens S., Read J., Baines R., Chatterjee A., Archer J. Validation of multisource feedback in assessing medical performance: a systematic review. J. Continuing Educ. Health Prof. 2018;38(4):262–268. doi: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Jonge L.P.J.W.M., Mesters I., Govaerts M.J.B., et al. Supervisors' intention to observe clinical task performance: an exploratory study using the theory of planned behaviour during postgraduate medical training. BMC Med. Educ. 2020;20(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02047-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Michael Shanahan E., van der Vleuten C., Schuwirth L. Conflict between clinician teachers and their students: the clinician perspective. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2020;25(2):401–414. doi: 10.1007/s10459-019-09933-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data included in article/supp. material/referenced in article.