Abstract

Background

The current global mpox virus (MPXV) outbreak has been declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern by WHO, with more than 80,000 cases confirmed across multiple continents. Diagnosis is confirmed by PCR of viral DNA from vesicle and other swabs.

Objective

The aim of this study was to assess commercial RT PCR assays for Orthopoxvirus (OPX) and MPXV for analytical sensitivity, and percent agreements and compare them to primer/probe sets employed at the Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory (VIDRL), Centers for Disease Control andPrevention (CDC) and US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID). Limits of detection (LOD), intra-run variability, cross-reactivity and performance on forty clinical samples was assessed on eleven commercial assays and five primer/probe combinations used at VIDRL, CDC and USAMRIID.

Results

All assays were able to detect OPX and MPXV (LOD 57 to 14,495 copies/mL) with intra-run coefficients of variation between Cycle thresholds of 0.58 and 3.44, and there was no unexpected cross-reactivity. All assays demonstrated 100% negative percent agreement with clinical samples and all but one yielded 100% positive percent agreement.

Conclusions

Variations in LOD between assays may be dependent on the platform used and sample type. Despite the overall comparable performance of the assays assessed, it is important that routine laboratories perform in-house validations before implementing RT PCR for OPX and/or MPXV as reliable and accurate laboratory diagnosis of MPXV and isolation is crucial to containing the spread of this current outbreak and informing public health interventions and response.

Keywords: Mpox, Monkeypox virus, Orthopoxvirus, Analytical sensitivity, Positive percent agreement, Negative percent agreement, Polymerase chain reaction

1. Background

Mpox virus (MPXV), formerly monkeypox, is a double-stranded DNA virus belonging to Orthopoxvirus (OPX) genus of Poxviridae and related to smallpox [1]. The first human case was identified in 1970 [2], and it has primarily been found in Africa, except when related to travel or imported animals [3], [4], [5]. In May 2022 multiple concurrent cases were identified in several non-endemic countries, including Australia [6,7]. This current MPXV outbreak is the largest globally and marks the first substantial local transmission across multiple continents [7,8]. At 16th November 2022, there were 80,064 confirmed MPXV cases globally [9].

In this current outbreak, most cases are among men who have sex with men [6]. Transmission occurs through respiratory droplets, close/direct contact with skin lesions, and possibly through contaminated fomites [6,8]. In addition to vaccination, rapid diagnosis and infection control measures remain key interventions to reduce ongoing transmission. MPXV diagnostic testing is performed using PCR assays generic to OPX or specific to MPXV [10], [11], [12]. The Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory (VIDRL) utilises in-house, validated assays for OPX and MPXV [13]. Although an increasing number of commercially available assays are available, there are limited published data on their performance characteristics.

1.1. Objectives

In order to inform diagnostic testing algorithms for MPXV, we evaluated nine commercially available MPX and two OPX Real Time RT-PCR assays (Table S1) and compared these with five primer/probe combinations used in laboratories [10,14].

1.2. Study design

MPXV was cultured from a vesicle swab of a patient with MPX in Vero/hSLAM cells in a Physical/Biological Containment Level 3 laboratory. Nucleic Acid was extracted using Qiagen QIAamp Viral Mini Kit (Hilden, Germany) as per manufacturer's instructions. The DNA extract was quantified by digital droplet PCR (Bio-Rad, CA), sequenced (GenBank ON631963) and panels prepared. Limits of Detection (LOD) were assessed with 8 × 4-fold dilution series of extracted DNA, spanning high and low copy number, and tested in quadruplicate with each assay. LOD was defined as the lowest copy number where all four replicates were detected. PCR Efficiency was calculated where there were four or more data-points of the serial dilutions using GraphPad Prism version 9.3.1.

A panel of non-MPXV pathogens (distractor panel), derived from isolates and/or clinical samples in viral transport medium (VTM), was employed to assess specificity. These viruses were chosen as they pose a differential diagnosis and/or may be found at anatomical sites associated with MPXV infection. The distractor panel included high burden (Cycle Threshold (Ct) <23) Varicella Zoster virus (VZV), Herpes Simplex virus, Type 1 (HSV-1) and 2 (HSV-2), Enterovirus (EV), Vaccinia virus (VACV), Orf virus (Orf), Molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV), and a pooled NATtrol Respiratory panel with Ct's 29 to 40 (Zeptometrix, NY). Intra-run variability was assessed by spiking DNA into VTM, universal transport medium, Liquid Amies, 0.9% w/v saline and nuclease free water, re-extracting and testing in quadruplicate, effectively yielding 20 replicates, which were tested in the 16 assays.

Extracted RNA from forty clinical samples was tested in duplicate in all assays after storage of aliquots at −80 °C. Twenty clinical samples were collected in VTM, from two sites from 10 patients with MPX infection. These consisted of 10 genital, 6 skin and 4 oral/throat swabs from suspected mpox lesions. Twenty negative samples in VTM, 9 genital and 11 anal swabs collected before the MPXV epidemic, were tested in duplicate. Samples were considered positive if they had detectable DNA in both duplicates.

Supplementary Table 1 (Table S1) shows the source of the commercial assays assessed, which were performed as per the manufacturer's instructions unless specified. In-house primer/probe combinations assessed are shown in Table S2. All testing was performed on an ABI 7500 FAST Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, CA). Cycling conditions are shown in the Supplementary.

This study was performed under Quality Assurance ethics, QA2019134.

2. Results

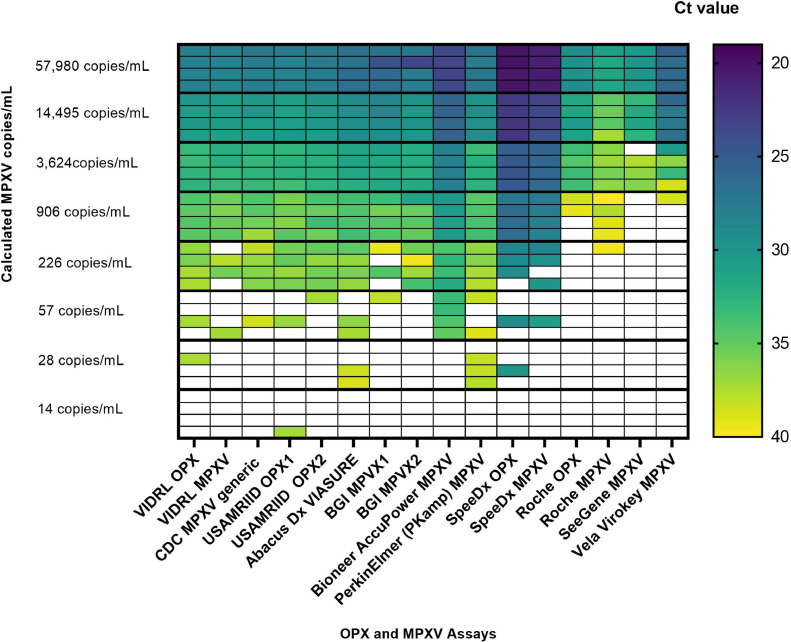

LOD for all the assays are shown in Fig. 1 . Seven of 16 assays yielded LOD of 226 copies/mL and one (Bioneer AccuPower) had LOD of 57 copies/mL. The SpeeDx assays yielded LOD close to 226 copies/mL with 3 of 4 replicates yielding detectable DNA. The Roche, SeeGene and VELA assays had LOD between 906 and 14,495 copies/mL

Fig. 1.

Heat map displaying Limits of Detection results for all assays. Each dilution was tested in quadruplicate in all assays and Cts were recorded. A Ct < 40 was considered positive.

All assays were highly specific with none demonstrating cross-reactions with high burden VZV, HSV-1, HSV-2, EV, Orf, MCV and the respiratory panel. VACV was detected, in VIDRL, USAMRIID [10] and Roche OPX and VIDRL MPXV specific assays. All assays performed well with intra-run variation with coefficients of variation between Ct's of 0.58 to 3.44 (Table S3).

Positive percent agreement (PPA) and negative percent agreement (NPA) of clinical sample results and PCR Efficiency are summarised in Table 1 . All assays detected the 20 known positive clinical samples except for the Vela, which did not detect four samples in all duplicates. The negative samples were non-reactive in all assays.

Table 1.

Positive percent agreement, negative percent agreement and PCR efficiency of OPX and MPXV RT-PCR assays.

| Clinical Samples | VIDRL |

VIDRL |

CDC |

USAMRIID |

USAMRIID |

Abacus dx |

BGI |

Bioneer |

Perkin Elmer PKamp |

SpeeDx |

Roche LightMix M odularDx |

Seegene Novaplex |

Vela ViroKey® |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPX | MPXV | MPXV | OPX | Ortho 2 | VIASURE MPXV | MPXV 1 | MPXV 2 | Accupower ®MPXV |

MPXV | OPX | MPXV | OPX | MPXV | MPXV | MPXV | |

| Positive Percent Agreement (% positive samples detected) |

20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 16 (75) |

| Negative Percent Agreement (% negative samples negative) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) | 20 (100) |

| Total | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| PCR Efficiency% |

89.37 | 89.67 | 80.12 | 94.39 | 93.29 | 79.23 | 64.17 | 74.97 | 84.33 | 78.76 | 84.94 | 86.61 | N/A | 79.82 | N/A | N/A |

3. Discussion

This study showed varying analytical sensitivity between eleven commercial assays for OPX, MPXV and five primer/probe combinations described by VIDRL, CDC and USAMRIID with LOD ranging from 57 to 14,495 copies/mL, Fig. 1. Variability in performance and PCR Efficiency (Table 1) of commercial assays may be explained by prior primer/probe optimisation on proprietary PCR thermal cyclers. Lower LOD may be attributed to increased ratio of sample to mastermix utilised, such as the Bioneer AccuPower and PerkinElmer PKamp assays, See Table S1. Comparison of Ct values between assays was unreliable in this analysis as some assays, notably the Bioneer and SpeeDx assays implemented touchdown amplification or pre-cycling, before capturing fluorescent readouts, Fig. 1.

Reassuringly, all assays performed well with minimal intra-run variability and no cross-reactivity with pathogens that present a similar clinical picture to MPXV. Interestingly, all OPX assays demonstrated reactivity to VACV except for the SpeeDx OPX assay, which was disappointing. The VIDRL MPXV assay demonstrated non-specific reactivity with VACV. Fortunately, VACV has limited utility and unlikely to pose a differential diagnosis. This cross-reactivity has been described by others [15]. Despite differences in LOD, the PPA of nearly all assays assessed was 100%, Table 1. The Vela Virokey however, missed detecting one nasopharyngeal, two oral and one anal swab, potentially due to lower viral burden. Deletions in the TNF receptor gene (J2R), the target site for this assay, have been reported [9,16]. Sequencing of 1 sample did not show deletions but a SNP (results not shown) was detected and may explain the failure to detect this sample. This finding may have clinical implications for pre-symptomatic screening of close contacts [17]. It was reassuring to note that all assays yielded 100% NPA in that all samples collected before the epidemic were negative for MPXV.

A limitation of this study was the small sample size and there may be some sites not tested. Another limitation is utility of a single extraction technique and RT PCR instrument for assessing intra-run variability. Accurate LOD was beyond the means of this study as it would require testing 20 replicates at the lower limit of each of the 16 assays. Individual laboratory assessment is recommended to ascertain optimal extraction and RT PCR platforms are utilised. It is also important to consider implementation of specimen adequacy controls to ensure appropriate sampling [18]. Only 2 of the commercial assays in this study incorporated a known cellularity control (Table S1). Nevertheless, it is encouraging that the majority of assays, described here and elsewhere [19], could be readily implemented for reliable and accurate MPXV diagnosis.

A diversity of assays is required to provide uninterrupted, reliable diagnostic services. This comprehensive evaluation offers valuable information on performance characteristic of a broad range of diagnostic MPXV and OPX assays.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no Conflicts of Interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

The following assays were provided free of charge for evaluation purposes: Perkin Elmer PKamp, SpeeDx OPX and MPXV, Bioneer AccuPower and Vela Virokey.

We thank scientific staff at VIDRL and the patients impacted by monkeypox.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2023.105424.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Petersen E., Kantele A., Koopmans M., Asogun D., Yinka-Ogunleye A., Ihekweazu C., et al. Human monkeypox: epidemiologic and clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and prevention. Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2019;33:1027–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2019.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arita I., Henderson D.A. Monkeypox and whitepox viruses in West and Central Africa. Bull. World Health Organ. 1976;53:347–353. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hobson G., Adamson J., Adler H., Firth R., Gould S., Houlihan C., et al. Family cluster of three cases of monkeypox imported from Nigeria to the United Kingdom, May 2021. Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = Eur. Commun. Dis. Bull. 2021;26 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.32.2100745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dubois M.E., Slifka M.K. Retrospective analysis of monkeypox infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008;14:592–599. doi: 10.3201/eid1404.071044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reed K.D., Melski J.W., Graham M.B., Regnery R.L., Sotir M.J., Wegner M.V., et al. The detection of monkeypox in humans in the Western Hemisphere. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:342–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thornhill J.P., Barkati S., Walmsley S., Rockstroh J., Antinori A., Harrison L.B., et al. Monkeypox virus infection in humans across 16 countries - April–June 2022. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022;387:679–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2207323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin-Delgado M.C., Martin Sanchez F.J., Martinez-Selles M., Molero Garcia J.M., Moreno Guillen S., Rodriguez-Artalejo F.J., et al. Revista espanola de quimioterapia: publicacion oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Quimioterapia; 2022. Monkeypox in Humans: A New Outbreak. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed M., Naseer H., Arshad M., Ahmad A. Monkeypox in 2022: a new threat in developing. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022;78 doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lab Alert: MPXV TNF Receptor Gene Deletion May Lead to False Negative Results with Some MPXV Specific LDTs. https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/world-map.html. 2022. (Accessed 02/12/2023).

- 10.Kulesh D.A., Baker R.O., Loveless B.M., Norwood D., Zwiers S.H., Mucker E., et al. Smallpox and pan-orthopox virus detection by real-time 3′-minor groove binder TaqMan assays on the roche LightCycler and the Cepheid smart Cycler platforms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004;42:601–609. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.2.601-609.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huggett J.F., French D., O’Sullivan D.M., Moran-Gilad J., Zumla A. Monkeypox: another test for PCR, Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European Commun. Dis. Bull. 2022;27:32. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.32.2200497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porzucek A.J., Proctor A.M., Klinkhammer K.E., Tritsch S.R., Robertson M.A., Bashor J.P., et al. Development of an accessible and scalable qPCR assay for Monkeypox virus detection. J. Infect. Dis. 2022;12 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiac414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hammerschlag Y., MacLeod G., Papadakis G., Adan Sanchez A., Druce J., Taiaroa G., et al. Monkeypox infection presenting as genital rash, Australia, May 2022, Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = Eur. Commun. Dis. Bull. 2022;27 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.22.2200411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y., Zhao H., Wilkins K., Hughes C., Damon I.K. Real-time PCR assays for the specific detection of monkeypox virus West African and Congo Basin strain DNA. J. Virol. Methods. 2010;169:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michel J., Targosz A., Rinner T., Bourquain D., Brinkmann A., Sacks J.A., et al. Evaluation of 11 commercially available PCR kits for the detection of monkeypox virus DNA, Berlin, July to September 2022, Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = Eur. Commun. Dis. Bull. 2022;27:45. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2022.27.45.2200816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garrigues J.M., Hemarajata P., Lucero B., Alarcon J., Ransohoff H., Marutani A.N., et al. Identification of human monkeypox virus genome deletions that impact diagnostic assays. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2022;60 doi: 10.1128/jcm.01655-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norz D., Brehm T.T., Tang H.T., Grewe I., Hermanussen L., Matthews H., et al. Clinical characteristics and comparison of longitudinal qPCR results from different specimen types in a cohort of ambulatory and hospitalized patients infected with monkeypox virus. J. Clin. Virol. 2022;155 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2022.105254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mostafa H.H. Importance of internal controls to monitor adequate specimen collection: the case of orthopoxvirus real-time PCR. J. Clin. Virol. 2022;156 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2022.105294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mills M.G., Juergens K.B., Gov J.P., McCormick C.J., Sampoleo R., Kachikis A., et al. Evaluation and clinical validation of monkeypox (mpox) virus real-time PCR assays. J. Clin. Virol. 2023;159 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2022.105373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.