This cohort study assesses the association of COVID-19 vaccination with breakthrough infections and complications in patients with cancer compared with noncancer controls.

Key Points

Question

What is the outcome of COVID-19 vaccination in patients with hematologic and solid cancer?

Findings

In this cohort study of 289 400 vaccinated patients with cancer and 1 157 600 matched noncancer controls, patients with cancer had significantly higher risk of breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 outcomes including hospitalization and death; the risk was substantial for patients with hematologic cancer and patients with solid cancer receiving active chemotherapy. A third vaccine dose was associated with lower risk of infection and severe outcomes.

Meaning

Patients receiving cancer treatment and patients with hematologic cancer, regardless of treatment status, should be prioritized for booster vaccination, preexposure prophylaxis, and, in the event of SARS-CoV-2 infection, early antiviral therapy.

Abstract

Importance

Patients with cancer are known to have increased risk of COVID-19 complications, including death.

Objective

To determine the association of COVID-19 vaccination with breakthrough infections and complications in patients with cancer compared to noncancer controls.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective population-based cohort study using linked administrative databases in Ontario, Canada, in residents 18 years and older who received COVID-19 vaccination. Three matched groups were identified (based on age, sex, type of vaccine, date of vaccine): 1:4 match for patients with hematologic and solid cancer to noncancer controls (hematologic and solid cancers separately analyzed), 1:1 match between patients with hematologic and patients with solid cancer.

Exposures

Cancer diagnosis.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Outcomes occurring 14 days after receipt of second COVID-19 vaccination dose: primary outcome was SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection; secondary outcomes were emergency department visit, hospitalization, and death within 4 weeks of SARS-CoV-2 infection (end of follow-up March 31, 2022). Multivariable cumulative incidence function models were used to obtain adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) and 95% CIs.

Results

A total of 289 400 vaccinated patients with cancer (39 880 hematologic; 249 520 solid) with 1 157 600 matched noncancer controls were identified; the cohort was 65.4% female, and mean (SD) age was 66 (14.0) years. SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection was higher in patients with hematologic cancer (aHR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.20-1.46; P < .001) but not in patients with solid cancer (aHR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.96-1.05; P = .87). COVID-19 severe outcomes (composite of hospitalization and death) were significantly higher in patients with cancer compared to patients without cancer (aHR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.42-1.63; P < .001). Risk of severe outcomes was higher among patients with hematologic cancer (aHR, 2.51; 95% CI, 2.21-2.85; P < .001) than patients with solid cancer (aHR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.24-1.64; P < .001). Patients receiving active treatment had a further heightened risk for COVID-19 severe outcomes, particularly those who received anti-CD20 therapy. Third vaccination dose was associated with lower infection and COVID-19 complications, except for patients receiving anti-CD20 therapy.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this large population-based cohort study, patients with cancer had greater risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and worse outcomes than patients without cancer, and the risk was highest for patients with hematologic cancer and any patients with cancer receiving active treatment. Triple vaccination was associated with lower risk of poor outcomes.

Introduction

Early studies in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic reported that patients with cancer were at increased risk of COVID-19 severe outcomes compared to those without cancer, particularly patients with hematologic cancers.1 Studies on antibody responses postvaccination revealed that SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections correlate with lower levels of anti-spike IgG and neutralizing antibodies.2 Reports have shown reduced seroresponse following vaccination in patients with cancer.3,4 As such, we hypothesized that patients with cancer have worse outcome after vaccination, with greater breakthrough infections and worse COVID-19 outcomes, particularly for patients with hematologic cancer.

In this large population-based cohort study, we set out to examine the relative risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections and COVID-19 outcomes in vaccinated patients with cancer vs matched noncancer controls, and separately, in those with hematologic vs solid cancer.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study using linked administrative databases, held at ICES (formerly the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences), which captures individual-level records all 14 million residents of Ontario, Canada. This study complied with ICES data confidentiality and privacy guidelines and was approved by the Research Ethics Board at the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (REB# 4995).

Study Population, Exposure, and Definitions

All Ontario residents 18 years and older who received 2 or more doses of COVID-19 vaccination between December 9, 2020 (the date of vaccine approval in Canada), and December 17, 2021, were eligible for inclusion. Index date was defined as the 14th day after second COVID-19 vaccination. Exclusion criteria were as follows: invalid health card number and no health care contact within 2 years of the index date.

Patients with cancer were defined as eligible individuals with a diagnosis of hematologic or solid cancer within 10 years of index date, identified through Ontario Cancer Registry (OCR) (International Classification of Diseases [ICD] codes in eTable 1 in Supplement 1), while noncancer controls were defined as those with no record of cancer. We then matched patients with hematologic cancer or solid cancer with 4 noncancer controls, respectively, and separately, 1:1 matching of patients with hematologic cancer with patients with solid cancer, based on age, sex, type of COVID-19 vaccine (mRNA-based BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273; non-mRNA based ChAdOx1 nCoV-19), and date of vaccination plus or minus 3 days (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1 shows visual representation of matched groups).

Covariates

Demographic information on age, sex, socioeconomic status, and vital status was identified by deterministic linkage of OCR records to the Registered Persons Database. Other databases accessed to identify comorbidities and comorbidity burden are detailed in eMethods in Supplement 1, and ICD 10th revision (ICD-10) codes are presented in eTable 2 in Supplement 1.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection (polymerase chain reaction [PCR] confirmed, identified through Ontario Laboratory Information Database) after the index date. The secondary outcomes were COVID-19–related emergency department (ED) visit (without inpatient admission) identified through the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System database, inpatient hospitalization (including intensive care unit admissions) identified through the Hospital Discharge Abstract Database, or death (individuals with death recorded in the Registered Persons Database within 4 weeks of a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test result, as previously defined5,6). COVID-19 ED visits and hospitalizations with an associated positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test result were ascertained through ICD-10 codes U07.1 and U07.2, previously validated with 98% sensitivity and 99% specific in the US hospital setting.7

End of follow-up differed for primary and secondary outcomes. Breakthrough infections were captured until December 31, 2021, as Ontario eligibility criteria for PCR testing changed after this date to limit testing to high-risk individuals and high-risk settings (including ED visits and hospitalizations).8 COVID-19–related outcomes were captured until March 31, 2022.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Standardized differences were computed for baseline characteristics. We used cumulative incidence functions (CIFs) and univariate and multivariate cause-specific Cox proportional hazard models to compare the risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection between the matched groups, and estimated the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs based on comparison of time-to-event rates. Similarly, CIFs and cause-specific hazard models were used to compare the risk of COVID-19–related outcomes, ED visit, death, and severe COVID-19 outcomes defined as a composite of hospitalization or death. Multivariate models adjusted for comorbidity score using aggregated clinical groups, and COVID-19 dose 3 vaccination as a time-varying covariate.

Planned a priori restricted analysis was conducted for patients with cancer receiving active chemotherapy (defined as within 6 months of the index date to end of follow-up period) and anti-CD20 treatment (defined as within 12 months of the index date to end of follow-up period).

Individuals were followed up from index date and censored at time of death, December 31, 2021, for breakthrough infections, or March 31, 2022, for COVID-19 outcomes, whichever came first.

For all analyses, a 2-tailed P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Patient Characteristics

The study population included 289 400 vaccinated patients with cancer (39 880 hematologic cancer, 249 520 solid), and 1 157 600 matched vaccinated noncancer controls. The cohort was 65.4% female, and mean (SD) age was 66 (14.0) years (Table 1; full characteristics summarized in eTable 3 in Supplement 1). The majority of the study population was vaccinated with an mRNA-based vaccine. Hematologic cancer and solid cancer were separately 1:1 matched (eTable 4 in Supplement 1). Compared to patients without cancer, patients with cancer had a higher comorbidity index; however, standardized differences of comorbidities recognized as factors associated with severe COVID-19 outcomes were similar.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of 289 400 Vaccinated Patients With Cancer and 1 157 600 Vaccinated Noncancer Controls.

| Characteristica | No. (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noncancer controls | All cancer | Standardized differences | Hematologic | Solid | |

| No. | 1 157 600 | 289 400 | 39 880 | 249 520 | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 66.04 (14.01) | 66.05 (14.01) | 0 | 65.85 (15.59) | 66.08 (13.74) |

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 757 109 (65.4) | 189 278 (65.4) | 0 | 18 640 (46.7) | 170 638 (68.4) |

| Male | 400 492 (34.6) | 100 123 (34.6) | 0 | 21 240 (53.3) | 78 883 (31.6) |

| Vaccine type | |||||

| Mixed | 30 681 (2.1) | 17 129 (5.9) | 0.259 | 1845 (4.6) | 15 284 (6.1) |

| mRNA | 1 389 060 (96.0) | 264 124 (91.3) | 0.079 | 37 058 (92.9) | 227 066 (91.0) |

| Non-mRNA | 27 259 (1.9) | 8147 (2.8) | 0.255 | 977 (2.4) | 7170 (2.9) |

| ACG category | |||||

| 0-4 | 490 292 (42.4) | 77 196 (26.7) | 0.334 | 10 252 (25.7) | 66 944 (26.8) |

| 5-9 | 481 698 (41.6) | 132 945 (45.9) | 0.278 | 17 580 (44.1) | 115 365 (46.2) |

| ≥10 | 185 610 (16.0) | 79 259 (27.4) | 0.087 | 12 048 (30.2) | 67 211 (26.9) |

| Active chemotherapy | 0 | 38 155 (13.2) | 0.551 | 9554 (24.0) | 28 601 (11.5) |

| Anti-CD20 therapy | 0 | 2362 (0.8) | 0.128 | 2238 (5.6) | 124 (<0.1) |

Abbreviation: ACG, aggregated clinical group.

Full baseline characteristics are shown in eTable 3 in Supplement 1.

Among patients with cancer, 24.0% and 11.5% were receiving active chemotherapy for hematologic and solid cancer, respectively. Among patients with hematologic cancer, 5.6% received anti-CD20 therapy.

SARS-CoV-2 Breakthrough Infections

During follow-up until December 31, 2021, there were 3118 and 12 150 breakthrough infections in the cancer and noncancer groups, respectively. Unadjusted CIF curves of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection between matched groups are shown in eFigure 2 in Supplement 1, with corresponding forest plot of unadjusted HRs shown in eFigure 3 in Supplement 1, and adjusted HRs shown in Table 2. SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection was significantly higher in all patients with cancer when compared to noncancer controls (adjusted HR [aHR], 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01-1.09; P = .02). However, the higher breakthrough infection risk was seen in patients with hematologic cancer (aHR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.20-1.46; P < .001) but not patients with solid cancer (aHR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.96-1.05; P = .87). Correspondingly, higher risk of breakthrough infection was observed when comparing patients with hematologic vs solid cancers (aHR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.07-1.36; P < .001).

Table 2. Adjusted Hazard Ratios for Relative Risk of SARS-CoV-2 Breakthrough Infection and COVID-19–Related Outcomes in Respective Matched Groups.

| Outcome | aHR (95% CI)a | P value |

|---|---|---|

| All patients with cancer vs controls | ||

| Breakthrough infection | 1.05 (1.01-1.09) | .02 |

| ED visit | 1.28 (1.17-1.39) | <.001 |

| Hospitalization/death | 1.52 (1.42-1.63) | <.001 |

| Death | 1.60 (1.42-1.81) | <.001 |

| Hematologic vs controls | ||

| Breakthrough infection | 1.33 (1.20-1.46) | <.001 |

| ED visit | 2.54 (2.12-3.05) | <.001 |

| Hospitalization/death | 2.51 (2.21-2.85) | <.001 |

| Death | 2.32 (1.81-2.97) | <.001 |

| Solid vs controls | ||

| Breakthrough infection | 1.00 (0.96-1.05) | .87 |

| ED visit | 1.06 (0.96-1.17) | .29 |

| Hospitalization/death | 1.29 (1.20-1.39) | <.001 |

| Death | 1.43 (1.24-1.64) | <.001 |

| Hematologic vs solid | ||

| Breakthrough infection | 1.20 (1.07-1.36) | .003 |

| ED visit | 2.43 (1.92-3.09) | <.001 |

| Hospitalization/death | 1.83 (1.92-3.09) | <.001 |

| Death | 1.75 (1.33-2.30) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; ED, emergency department.

Adjusted for aggregated clinical group score and receipt of third COVID-19 vaccination as time-varying covariate.

Receipt of a third vaccine dose was consistently associated with lower risk of breakthrough infection: all patients with cancer aHR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.54-0.61; P < .001; patients with hematologic cancer aHR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.54-0.69; P < .001; patients with solid cancer aHR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.53-0.60; P < .001; hematologic vs solid aHR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.50-0.70; P < .001.

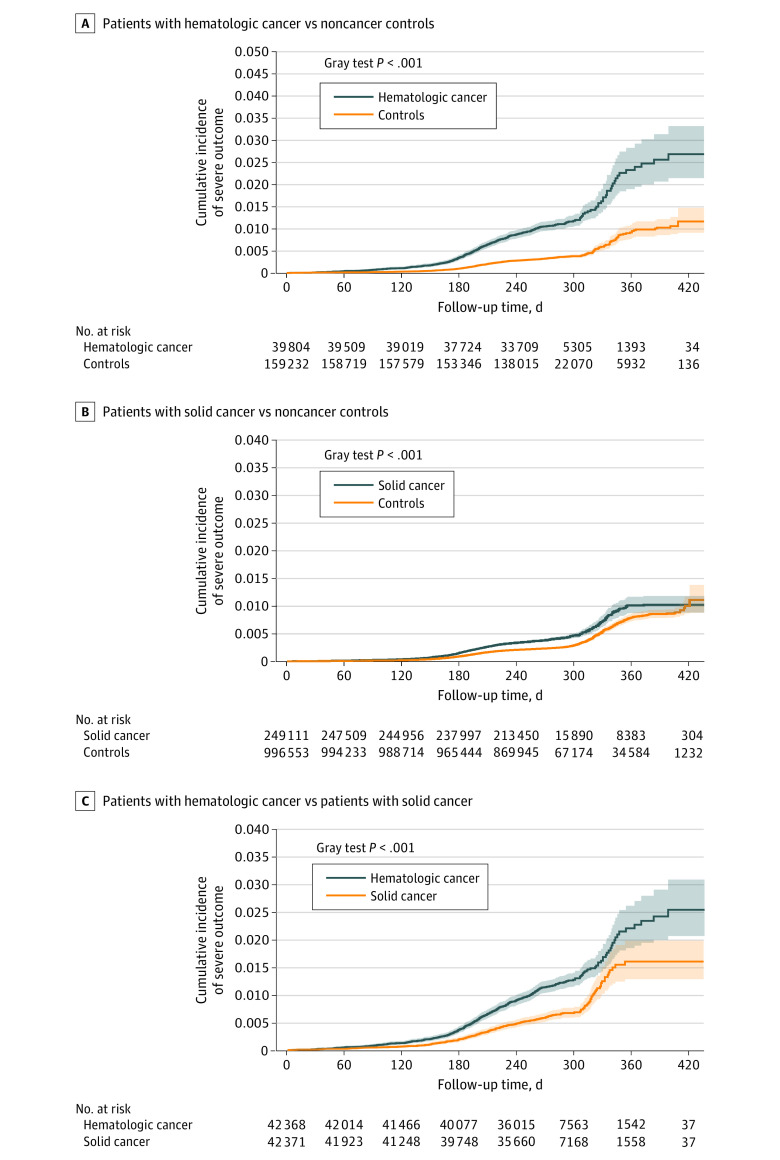

COVID-19–Related Outcomes

During follow-up until March 31, 2022, there were 711 and 1399 ED visits and severe outcomes in the cancer group, and 1918 and 3078 ED visits and severe outcomes in the noncancer group, respectively. Unadjusted CIF curves of COVID-19–related ED visits and severe outcomes for matched groups are shown in eFigure 4 in Supplement 1; Figure 1, respectively. Emergency department visits, severe outcomes, and death were all significantly higher in patients with cancer compared to noncancer controls (ED visit aHR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.17-1.39; P < .001; severe outcomes aHR, 1.52; 95% CI, 1.42-1.63; P < .001; death aHR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.42-1.81; P < .001; Table 2). The increased risk was more pronounced for patients with hematologic cancer (ED visit aHR, 2.54; 95% CI, 2.12-3.05; P < .001; severe outcomes aHR, 2.51; 95% CI, 2.21-2.85; P < .001; death aHR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.81-2.97; P < .001) than patients with solid cancer (ED visit aHR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.96-1.17; P = .29; severe outcomes aHR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.20-1.39; P < .001; death aHR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.24-1.64; P < .001). Patients with hematologic cancer had 1.8- to 2.4-fold higher risk of COVID-19–related complications compared to matched patients with solid cancer (ED visit aHR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.92-3.09; P < .001; severe outcomes aHR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.92-3.09; P < .001; death aHR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.33-2.30; P < .001).

Figure 1. Cumulative Incidence of COVID-19 Outcomes Following Vaccination Among All Patients With Cancer.

Cumulative incidence of composite of COVID-19–related hospitalization or death for matched groups: patients with hematologic cancer vs noncancer controls (A); patients with solid cancer vs noncancer controls (B); patients with hematologic cancer vs patients with solid cancer (C). Shaded areas indicate 95% CIs.

Receipt of third vaccine dose was consistently protective of all COVID-19-related outcomes examined. For all patients with cancer compared to noncancer controls: ED visit aHR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.37-0.45; P < .001; severe outcomes aHR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.41-0.48; P < .001; death aHR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.35-0.45; P < .001. Similarly, significant protective association with the third dose was observed for other matched groups (eTables 5-7 in Supplement 1).

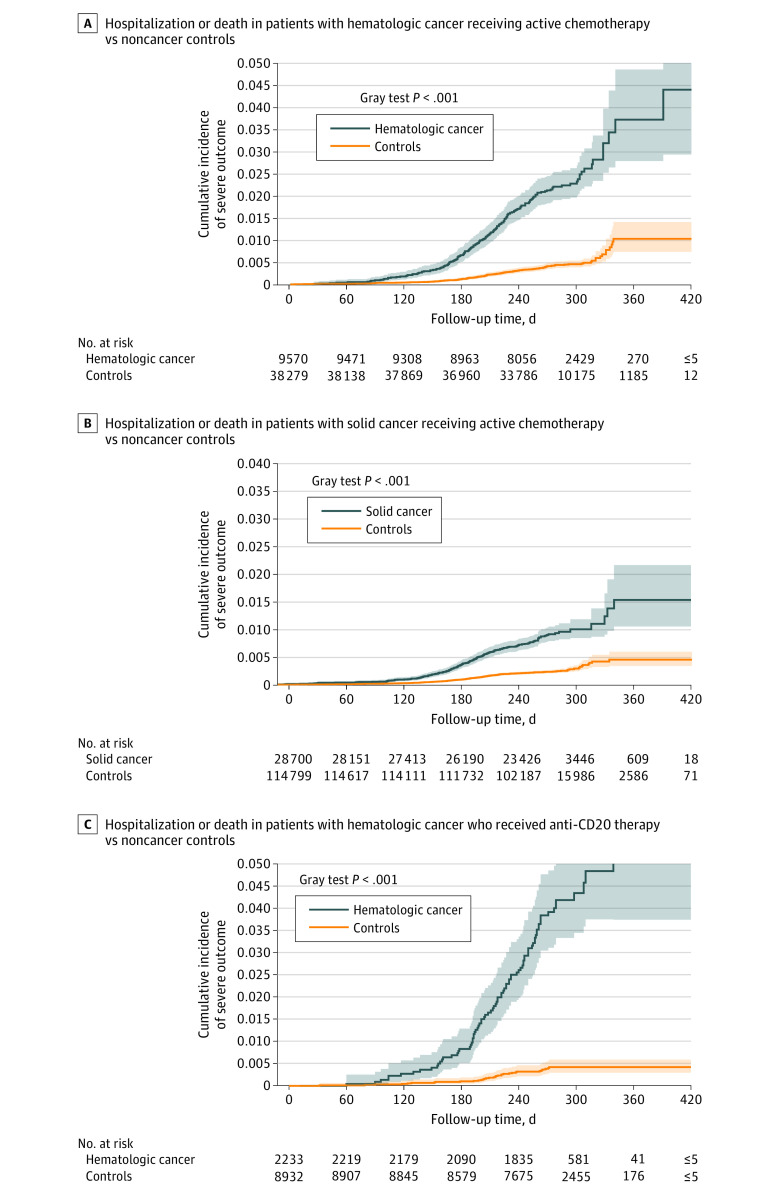

Vaccinated Patients With Cancer Receiving Active Therapy

Compared to noncancer controls, vaccinated patients with hematologic cancer (n = 9557) receiving active chemotherapy had a higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections (aHR, 1.63; 95% CI, 1.34-1.98; P < .001, eFigure 5A in Supplement 1) and COVID-19 outcomes (ED visit aHR, 4.22; 95% CI, 3.08-5.76; P < .001, eFigure 5C in Supplement 1; severe outcomes aHR, 3.97; 95% CI, 3.20-4.92; P < .001, Figure 2A; death aHR, 3.21; 95% CI, 2.19-4.71; P < .001) (Table 3). While no significant difference in breakthrough infection risk was observed in patients with solid cancer receiving active chemotherapy (n = 28 620) (aHR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.88-1.14; P = .99, eFigure 5B in Supplement 1), higher risk of ED visit, severe outcomes, and death were observed (ED visit aHR, 1.59; 95% CI, 1.25-2.03; P < .001, eFigure 5D in Supplement 1; severe outcomes aHR, 2.64; 95% CI, 2.19-3.18; P < .001, Figure 2B; death aHR, 4.48; 95% CI, 3.32-6.86; P < .001) (Table 3).

Figure 2. Cumulative Incidence of COVID-19 Outcomes Following Vaccination Among Patients With Cancer Receiving Active Therapy.

Cumulative incidence of COVID-19–related composite of hospitalization or death among matched patients with hematologic cancer receiving active chemotherapy vs noncancer controls (A) and patients with solid cancer receiving active chemotherapy vs noncancer controls (B). C, Cumulative incidence of COVID-19–related composite of hospitalization or death among matched patients with hematologic cancer who received anti-CD20 therapy vs noncancer controls. Shaded areas indicate 95% CIs.

Table 3. Adjusted Hazard Ratios for Relative Risk of SARS-CoV-2 Breakthrough Infection and COVID-19–Related Outcomes Restricted to Patients Receiving Active Treatment in Respective Matched Groups.

| Outcome | aHR (95% CI)a | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Hematologic receiving active chemotherapy vs controls | ||

| Breakthrough infection | 1.63 (1.34-1.98) | <.001 |

| ED visit | 4.22 (3.08-5.76) | <.001 |

| Hospitalization/death | 3.97 (3.20-4.92) | <.001 |

| Death | 3.21 (2.19-4.71) | <.001 |

| Solid receiving active chemotherapy vs controls | ||

| Breakthrough infection | 1.00 (0.88-1.14) | .99 |

| ED visit | 1.59 (1.25-2.03) | <.001 |

| Hospitalization/death | 2.64 (2.19-3.18) | <.001 |

| Death | 4.48 (3.32-6.86) | <.001 |

| Hematologic receiving anti-CD20 therapy vs controls | ||

| Breakthrough infection | 1.88 (1.27-2.78) | .002 |

| ED visit | 12.31 (6.37-23.79) | <.001 |

| Hospitalization/death | 7.14 (4.67-10.92) | <.001 |

| Death | 6.28 (2.86-13.82) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: aHR, adjusted hazard ratio; ED, emergency department.

Adjusted for aggregated clinical group score and receipt of third COVID-19 vaccination as time-varying covariate.

For patients with hematologic cancer who received anti-CD20 therapy (n = 2233), the risk of breakthrough infection was even higher (aHR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.27-2.78; P = .002, eFigure 6A in Supplement 1). Importantly, these patients had the most pronounced risk of COVID-19 outcomes relative to their matched controls (ED visit aHR, 12.31; 95% CI, 6.37-23.79; P < .001, eFigure 6B in Supplement 1; severe outcomes aHR, 7.14; 95% CI, 4.67-10.92; P < .001, Figure 2C; death aHR, 6.28; 95% CI, 2.86-13.82; P < .001) (Table 3).

A third COVID-19 vaccination dose was similarly associated with protection of COVID-19 outcomes in patients with cancer receiving active chemotherapy (eTables 8-9 in Supplement 1). However, a third vaccine dose was not associated with protection of COVID-19 outcomes in patients with hematologic cancer who received anti-CD20 therapy (eTable 10 in Supplement 1).

Discussion

In this large population-based cohort study of vaccinated patients with cancer (289 400), matched to vaccinated patients without cancer, patients with cancer had higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19–related poor outcomes compared to noncancer controls. The heightened risk was most notable for those receiving active chemotherapy and anti-CD20 therapy. In comparison to matched patients with solid cancer, patients with hematologic cancer had nearly 2-fold increased risk of severe outcomes and were at higher risk even in the absence of active chemotherapy.

Our study corroborates and builds on recently published studies addressing COVID-19 vaccine outcomes in the cancer population. Wu et al6 found that a proxy measure for effectiveness of the vaccine was 58% for all patients with cancer and 57% for those receiving active chemotherapy, respectively. However, COVID-19–related outcomes were not addressed in their study. The National COVID Cohort Collaborative compared outcomes of breakthrough infection, hospitalization, and death in vaccinated patients with cancer to unvaccinated patients without cancer (follow-up May 2021), showing that patients with cancer, particularly those with hematologic cancer, were more likely to develop breakthrough infections and severe outcomes, with odds ratios of 1.12 for breakthrough infection, and 1.33 for severe outcomes.9 A recent study by Wang et al10 comparing 45 253 matched vaccinated patients with cancer to noncancer controls showed that breakthrough infections, hospitalizations, and mortality were higher in patients with cancer (follow-up November 2021); however, outcomes in patients with hematologic cancer were not separately reported, and effect of active treatment was not addressed. The most recently published study by the UK Coronavirus Cancer Evaluation Project included 377 194 vaccinated patients with cancer compared to noncancer controls in a test-negative case-control design, with a primary outcome of breakthrough infections, reporting a lower efficacy of 65.5% in the cancer population, and lowest efficacy in those with hematologic cancers and those receiving active therapy.5

Our study differed in study design compared to aforementioned reports. The main objective herein was to estimate the relative risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19 complications in the vaccinated cancer population against a matched vaccinated population of controls without cancer, while several of the above studies examined vaccine effectiveness by comparing SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection between vaccinated vs unvaccinated patients with cancer. Our study is also unique as we sought to analyze patients with hematologic cancer separately and to our knowledge is the first to systematically match hematologic cancer to solid cancer for comparative analysis. Furthermore, our study is one of the largest population-based studies with the longest follow-up to date (March 31, 2022), which encompasses infections with SARS-CoV-2 Alpha variant, Delta variant, and Omicron variant. Lastly, our study is the first, to the best of our knowledge, to examine the association of COVID-19 booster vaccination with outcomes in the cancer population, while prior studies included data on 2 doses only.

Findings from our study certainly support worse outcome following COVID-19 vaccine in the cancer population compared to noncancer population, with more breakthrough infections and worse outcomes despite vaccination. This was particularly true for patients with cancer receiving active chemotherapy, with up to 4-fold higher risk for COVID-19 severe outcomes including hospitalization and death in patients with hematologic cancer. Although the population-based nature of this study did not allow us to discern the precise cause of death, our surrogate definition (death within 28 days of SARS-CoV-2 infection) is congruent with the definition used in prior reports.5,6 Given that the death risk in those with a breakthrough COVID-19 infection is higher compared to matched controls, the excess mortality risk is highly likely to be associated with COVID-19. Nevertheless, despite our findings of greater mortality, absolute rate of death was low compared to the prevaccination era (where rate of death ranged from 15%-35%1,11,12), suggesting that COVID-19 vaccination and targeted therapies likely were associated with better outcomes in this population.

Our results certainly support the notion that patients with hematologic cancer are at highest risk of poor COVID-19 outcomes. The risk difference observed between hematologic and solid cancers may reflect the disease-specific biology of hematologic cancers and type of therapy received. These findings are aligned with the lower vaccine serologic response reported in hematologic cancers, particularly patients with lymphoid cancers and/or receiving B-cell–depleting therapies (eg, anti-CD20 therapy) with markedly impaired immune response.3 In contrast, patients with solid cancer likely have similar vaccine serologic responsiveness compared to controls.4 COVID-19 outcomes in patients treated with anti-CD20 remain sparse in the literature. An earlier study by Mittelman et al13 compared vaccine efficacy in 32 516 matched hematologic cancer vs noncancer controls and reported a relative risk of 1.6 for infection and 2.3 for severe COVID-19 outcomes. In their study, only a small subset of 275 patients received rituximab, and although the authors noted higher risk of COVID-19 infection, relative risk was not reported. Our study offers the largest cohort of patients (>2000) who received anti-CD20 therapy, who have a substantially increased risk of infection and poor outcomes with 6- to 7-fold relative risk of hospitalization or death. Importantly, a third vaccine dose was not associated with protection against severe outcomes in this vulnerable population. This is not surprising given that B-cell reconstitution requires 9 to 12 months after last dose of anti-CD20 therapy.14 These data strongly support the use of additional layers of protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients who received or are receiving anti-CD20 therapy, such as preexposure COVID-19 prophylaxis with tixagevimab/cilgavimab (Evusheld).15 Of note, phase 3 trial data of Evusheld included only a small proportion of patients with cancer (7.4%),15 and its efficacy in the immunocompromised population, including those receiving anti-CD20 therapy, has not yet been evaluated. Future studies are required to address the effect of Evusheld on COVID-19 outcomes in patients exposed to anti-CD20 therapy.

Despite the lack of protection with a third dose of the vaccine in patients who received anti-CD20 therapy, we are the first, to our knowledge, to show that booster vaccination protects against breakthrough infection and severe outcomes in other patients with cancer. Our results support the use of booster doses to confer and enhance protection against COVID-19 hospitalizations and death among patients with cancer, even during Omicron variant surge.16 These results are aligned with studies reporting serologic responses following third vaccine dose, demonstrating that it significantly improved SARS-CoV-2 antibody concentrations and neutralizing capacity in patients with hematologic cancer.17,18 Taken together, our results support global vaccination programs prioritizing booster vaccination in those with hematologic cancers and patients with cancer receiving active therapy.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. It is limited by lack of granularity of clinical data due to use of administrative databases, and there may be residual confounding from unrecognized and unavailable factors. There may be behavioral differences in infection control practices and health care setting exposures between patients with cancer and noncancer controls that may affect outcomes. Although the Ontario Laboratory Information Database has been demonstrated to capture 91.8% of all provincially reported cases of laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection,19 breakthrough infections identified through self-administered rapid antigen tests are not captured. As such, bias in identification of breakthrough infections may exist in our study as patients with cancer likely have more health care contact and greater access and vigilance for COVID-19 testing than the general population. Cause-specific death information is lacking in this data set as there is a time delay in administrative linking of this information to patients. However, we used a definition for COVID-19–related death congruent with recent literature definition.6 Due to limitations of the Ontario medication database (limited to individuals ≥65 years), we were unable to ascertain patients receiving oral B-cell–depleting therapies, limiting our ability to examine the relative risk of such therapies on COVID-19 outcomes. Similarly, we were not able to ascertain receipt of COVID-19–directed therapies (corticosteroids, remdesivir, sotrovimab, tocilizumab, nirmatrelvir/ritonavir) and could not study their association with COVID-19 outcomes. Lastly, as with all retrospective studies, although this study reports important associations, causality cannot be established. Despite these limitations, the large sample size of matched patients with cancer, comparative analysis between hematologic and solid cancer, and incorporation of third vaccine dose data, makes this study a unique contribution to the COVID-19 literature in the cancer population.

Conclusions

In this large, population-based cohort study of vaccinated patients with cancer matched to vaccinated noncancer controls, findings show that patients with cancer have greater risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and worse COVID-19–related outcomes, but there is a protective association with third vaccine dose. Risks are highest for patients with hematologic cancer, particularly those receiving anti-CD20 therapy and patients with solid cancer receiving active chemotherapy. Our findings support the prioritization of high-risk populations for booster vaccination, forthcoming variant-specific vaccine products, preexposure prophylaxis (where available), and rapid antiviral treatment in the face of SARS-CoV-2 infection as COVID-19 continues to be relevant with ongoing surges leading to excess morbidity and mortality.

eMethods.

eFigure 1. Visualization of matched groups

eFigure 2. Cumulative incidence of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection following vaccination in the matched comparative groups

eFigure 3. Unadjusted hazard ratios for SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection, emergency visitation (ED), composite of COVID-19-related hospitalization or death (severe outcome), and death following vaccination within matched groups

eFigure 4. Cumulative incidence of COVID-19-related emergency visitation within matched groups

eFigure 5. Cumulative incidence of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19-related emergency room (ED) amongst matched cancer patients receiving active chemotherapy

eFigure 6. Cumulative incidence of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19-related emergency room (ED) amongst matched cancer patients

eTable 1. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) morphology codes for cancer subtypes

eTable 2. International classification of diseases (ICD) codes for comorbidities

eTable 3. Baseline characteristics of 289,400 vaccinated patients with cancer and 1,157,600 vaccinated non-cancer controls

eTable 4. Baseline characteristics of 42,473 matched patients with hematologic and solid cancer

eTable 5. Multivariable analysis for risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19 related outcomes in matched patients with hematologic cancer and non-cancer controls

eTable 6. Multivariable analysis for risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19 related outcomes in matched patients with solid cancer and non-cancer controls

eTable 7. Multivariable analysis for risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19-related outcomes in matched patients with hematologic cancer and solid cancer

eTable 8. Multivariable analysis for risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19 related outcomes in matched patients with hematologic cancer receiving active chemotherapy and non-cancer controls

eTable 9. Multivariable analysis for risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19 related outcomes in matched patients with solid cancer receiving active chemotherapy and non-cancer controls

eTable 10. Multivariable analysis for risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19 related outcomes in matched patients with hematologic cancer who received anti-CD20 therapy and non-cancer controls

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Vijenthira A, Gong IY, Fox TA, et al. Outcomes of patients with hematologic malignancies and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 3377 patients. Blood. 2020;136(25):2881-2892. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020008824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergwerk M, Gonen T, Lustig Y, et al. Covid-19 breakthrough infections in vaccinated health care workers. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(16):1474-1484. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2109072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gong IY, Vijenthira A, Betschel SD, Hicks LK, Cheung MC. COVID-19 vaccine response in patients with hematologic malignancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Hematol. 2022;97(4):E132-E135. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thakkar A, Gonzalez-Lugo JD, Goradia N, et al. Seroconversion rates following COVID-19 vaccination among patients with cancer. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(8):1081-1090.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee LYW, Starkey T, Ionescu MC, et al. ; NCRI Consumer Forum . Vaccine effectiveness against COVID-19 breakthrough infections in patients with cancer (UKCCEP): a population-based test-negative case-control study. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(6):748-757. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00202-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu JT, La J, Branch-Elliman W, et al. Association of COVID-19 vaccination with SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with cancer: a US nationwide Veterans Affairs study. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(2):281-286. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.5771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kadri SS, Gundrum J, Warner S, et al. Uptake and accuracy of the diagnosis code for COVID-19 among US hospitalizations. JAMA. 2020;324(24):2553-2554. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.20323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Updated eligibility for PCR testing and case and contact management guidance in Ontario. Published December 30, 2021. Accessed August 14, 2022. https://news.ontario.ca/en/backgrounder/1001387/updated-eligibility-for-pcr-testing-and-case-and-contact-management-guidance-in-ontario

- 9.Song Q, Bates B, Shao YR, et al. Risk and outcome of breakthrough COVID-19 infections in vaccinated patients with cancer: real-world evidence from the National COVID Cohort Collaborative. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(13):1414-1427. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang W, Kaelber DC, Xu R, Berger NA. Breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infections, hospitalizations, and mortality in vaccinated patients with cancer in the US between December 2020 and November 2021. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(7):1027-1034. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zarifkar P, Kamath A, Robinson C, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2021;33(3):e180-e191. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2020.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang H, Han H, He T, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19-infected cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(4):371-380. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mittelman M, Magen O, Barda N, et al. Effectiveness of the BNT162b2mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in patients with hematological neoplasms in a nationwide mass vaccination setting. Blood. 2022;139(10):1439-1451. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021013768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anolik JH, Friedberg JW, Zheng B, et al. B cell reconstitution after rituximab treatment of lymphoma recapitulates B cell ontogeny. Clin Immunol. 2007;122(2):139-145. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levin MJ, Ustianowski A, De Wit S, et al. ; PROVENT Study Group . Intramuscular AZD7442 (tixagevimab-cilgavimab) for prevention of Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(23):2188-2200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu J, Chandrashekar A, Sellers D, et al. Vaccines elicit highly conserved cellular immunity to SARS-CoV-2 Omicron. Nature. 2022;603(7901):493-496. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04465-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenberger LM, Saltzman LA, Senefeld JW, Johnson PW, DeGennaro LJ, Nichols GL. Anti-spike antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 booster vaccination in patients with B cell-derived hematologic malignancies. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(10):1297-1299. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haggenburg S, Hofsink Q, Lissenberg-Witte BI, et al. ; COBRA KAI Study Team . Antibody response in immunocompromised patients with hematologic cancers who received a 3-dose mRNA-1273 vaccination schedule for COVID-19. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(10):1477-1483. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.3227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chung H, He S, Nasreen S, et al. ; Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) Provincial Collaborative Network (PCN) Investigators . Effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 covid-19 vaccines against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe covid-19 outcomes in Ontario, Canada: test negative design study. BMJ. 2021;374:n1943. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.

eFigure 1. Visualization of matched groups

eFigure 2. Cumulative incidence of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection following vaccination in the matched comparative groups

eFigure 3. Unadjusted hazard ratios for SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection, emergency visitation (ED), composite of COVID-19-related hospitalization or death (severe outcome), and death following vaccination within matched groups

eFigure 4. Cumulative incidence of COVID-19-related emergency visitation within matched groups

eFigure 5. Cumulative incidence of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19-related emergency room (ED) amongst matched cancer patients receiving active chemotherapy

eFigure 6. Cumulative incidence of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19-related emergency room (ED) amongst matched cancer patients

eTable 1. The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) morphology codes for cancer subtypes

eTable 2. International classification of diseases (ICD) codes for comorbidities

eTable 3. Baseline characteristics of 289,400 vaccinated patients with cancer and 1,157,600 vaccinated non-cancer controls

eTable 4. Baseline characteristics of 42,473 matched patients with hematologic and solid cancer

eTable 5. Multivariable analysis for risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19 related outcomes in matched patients with hematologic cancer and non-cancer controls

eTable 6. Multivariable analysis for risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19 related outcomes in matched patients with solid cancer and non-cancer controls

eTable 7. Multivariable analysis for risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19-related outcomes in matched patients with hematologic cancer and solid cancer

eTable 8. Multivariable analysis for risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19 related outcomes in matched patients with hematologic cancer receiving active chemotherapy and non-cancer controls

eTable 9. Multivariable analysis for risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19 related outcomes in matched patients with solid cancer receiving active chemotherapy and non-cancer controls

eTable 10. Multivariable analysis for risk of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection and COVID-19 related outcomes in matched patients with hematologic cancer who received anti-CD20 therapy and non-cancer controls

Data Sharing Statement