Abstract

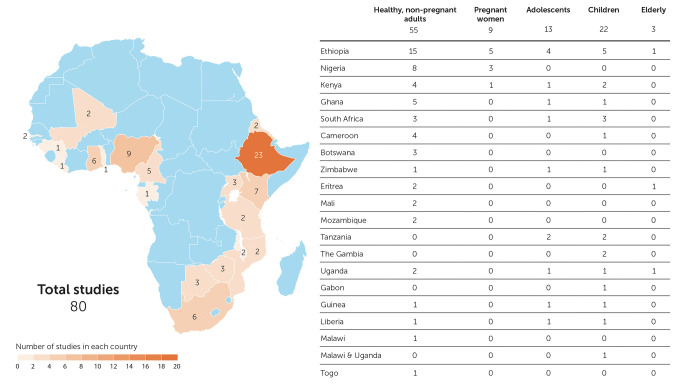

Region-specific laboratory reference intervals (RIs) are important for clinical trials and these data are often sparse in priority areas for research, including Africa. We reviewed data on RIs from Africa to identify gaps in the literature with a systematic review of PubMed for RI studies from Africa published ≥2010. Search focus included clinical analytic chemistry, hematology, immunological parameters and RIs. Data from adults, adolescents, children, pregnant women, and the elderly were included. We excluded manuscripts reporting data from persons with conditions that might preclude clinical trial participation in studies enrolling healthy volunteers. Of 179 identified manuscripts, 80 were included in this review, covering 20 countries with the largest number of studies in Ethiopia (n = 23, 29%). Most studies considered healthy, nonpregnant adults (n = 55, 69%). Nine (11%) studies included pregnant women, 13 (16%) included adolescents and 22 (28%) included children. Recruitment, screening, enrollment procedures and definition of age strata varied across studies. The most common type of RIs reported were hematology (66, 83%); 14 studies (18%) included flow cytometry and/or T cell counts. Other common tests or panels included liver function assays (32, 40%), renal function assays (30, 38%), lipid chemistries (17, 21%) and serum electrolytes (17, 21%). The number of parameters characterized ranged from only one (three studies characterized either CD4+ counts, D-dimer, or hemoglobin), to as many as 40. Statistical methods for calculating RIs varied. 56 (70%) studies compared their results to international RI databases. Though most presented their data side-by-side with international data with little accompanying analysis, nearly all reported deviation from comparator RI data, sometimes with half or more of otherwise healthy participants having an “out of range” result. We found there is limited local RI data available in sub-Saharan Africa. Studies to fill this gap are warranted, including efforts to standardize statistical methods to derive RIs, methods to compare with other RIs, and improve representative participant selection.

Introduction

Laboratory reference intervals (RIs) for a laboratory test are defined as that interval within which falls 95% of the healthy population. Accurate and appropriate RIs are important for the interpretation of clinical laboratory data, and are vital to guide the design, conduct and interpretation of clinical trials to ensure volunteer and product safety. Since 1992, systematic guidelines on the creation of reference intervals have been available from the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) and the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry (IFCC) [1] and more recently new methodology has been proposed as part of a global effort under the IFCC Committee on Reference Intervals and Decision Limits (C-RIDL) to standardize generation of RIs [2–4]. Because establishing RIs is expensive, logistically demanding, and time-consuming, many laboratories rely on RIs from assay package inserts, textbooks, or published data, which may be derived from very different populations. However, international studies employing systematic methodologies have demonstrated important differences between populations for some analytes [5, 6].

Other issues hamper the interpretation of regional RIs. Research Investigators often employ convenience sampling methods, enrolling blood donors, institute staff or students for their studies of reference intervals. While often easier and less expensive, this could introduce a selection bias if the population studied is systematically different from the population against which the RIs are meant to be used (e.g., younger, different patterns in alcohol and/or tobacco consumption, not pregnant, or living with HIV). Selection of study participants should be documented and should include factors such as age, sex, evaluation of health (e.g., at a minimum with a questionnaire, ideally with a physical examination and laboratory testing for pathological conditions) so that partitions of meaningful subclasses may be well described [1]. Additional methodology problems include insufficient sample size, poorly defined statistical methods, incomplete or non-standardized data collection (e.g., demographics, medical history), and inconsistent screening and enrollment procedures.

Sub-Saharan Africa is increasingly being recognized as an important region to conduct clinical trials [7, 8], and thus appropriate RIs are needed to manage volunteer wellbeing and guide the interpretation of clinical trial results. Between 2004 and 2006 IAVI conducted a large, multisite study (including teams from Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda and Zambia) to establish RIs among persons potentially suitable for participation in HIV prevention trials [5, 9]. Since then, large-scale, systematic efforts to characterize regional RIs in India, China and elsewhere around the world have been published [2, 6, 10, 11] but data from sub-Saharan Africa has been more limited. Here we review publications presenting the generation of newer RIs specific to sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

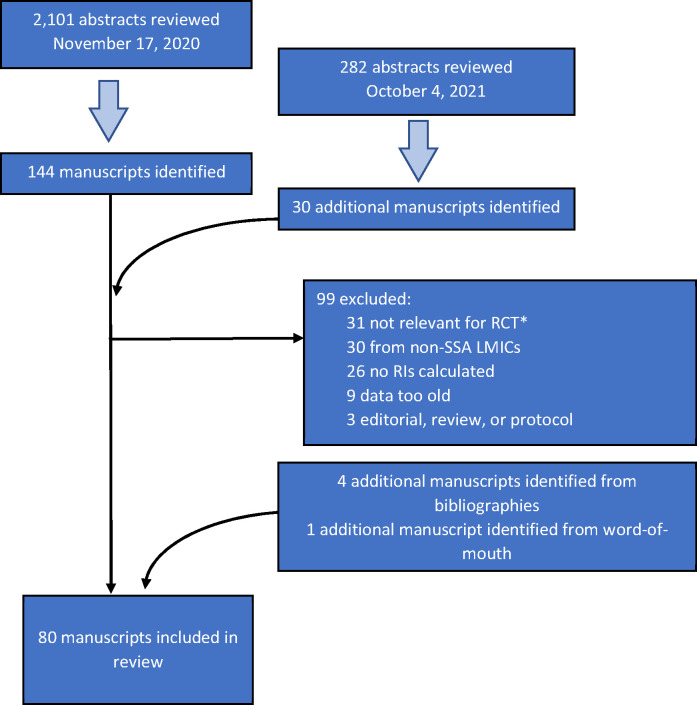

A systematic review of Pubmed and Pubmed Central was conducted in November 2020 to search for laboratory reference intervals in sub-Saharan African populations published in 2010 and later. The search was repeated in October 2021 to update any new publications in the interim. IAVI’s laboratory RI study included work done in 2004–6 [5, 9]; in the interest of focusing on more recent work, we excluded work conducted prior to 2006 (regardless of publication date). The review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (http://www.prisma-statement.org/, accessed 7 January 2022). We did not pool data for any type of meta-analyses, as study designs, source populations, the nature of the data, and the rationale for this review made this irrelevant. The search focus included concepts related to standards in clinical, analytic chemistry, hematology, metabolism, immunological and other assays or markers of important substances found in blood, urine, tissues, and other human biological fluids and reference values/intervals, i.e., the range or frequency distribution of a measurement in a population that has not been selected for the presence of disease or abnormality. Manuscripts that considered only clinical decision limits (i.e., thresholds or ranges of analytes associated with disease or negative clinical outcomes) were not considered. We limited our initial search to studies conducted in Africa. Highly relevant papers were also reviewed for citations and cited papers and with the Pubmed feature find similar articles. Relevant manuscripts that were identified were checked for any additional manuscripts not initially identified. This review was not registered, and a protocol was not prepared. The following terms were searched as MESH terms and as free text words:

blood proteins/standards, c reactive protein/standards, blood sedimentation/standards, ferritins/standards, cytokines/standards, chemokines/standards, vitamin d/standards, blood cell count/standards, clinical laboratory techniques/standards, hematology/standards, reference standards/standards, reference values/standards, bilirubin/standards, metabolism/standards, eosinophils/metabolism, hemoglobins/standards, immunoglobulin g/standards, l lactate dehydrogenase/standards, neutrophils/methods, allergy and immunology/standards, medical laboratory science/standards, blood proteins/standards, blood chemical analysis/standards, clinical chemistry tests/standards, reference intervals.

A secondary search for “African reference standards” and synonyms was performed in African Journal Online (https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajol), Sabinet (https://www.sabinet.co.za/), Google Scholar, Dimensions (https://www.digital-science.com/products/dimensions/), and Project Smile (https://resources.psmile.org/resources/equipment/reference-intervals/reference-ranges). Additional manuscripts were identified by review of selected publication references or by notification from an author.

One author (MP) reviewed each manuscript to extract details including year(s) of study, country or region of study, sample size, study population (i.e., healthy adults, pregnant women, adolescents [typically ages 13–17], children [typically 12 and under and age-stratified], or other), RI calculation methods, and analytes included. Then two authors (VK, PF) reviewed the abstracts independently and, where necessary, the extracted details to further screen manuscripts; both VK and PF had access to all papers. Studies were excluded if they were too old (study conduct was prior to 2006), RIs were not calculated or were calculated for a group with a specific pathological condition or environmental exposure that may not be broadly relevant for clinical trial participants in sub-Saharan Africa (we did seek studies of healthy persons living with HIV, though we did not find any), or the study was not conducted in sub-Saharan Africa. Some manuscripts did not specify when the study was conducted; we reviewed the manuscript for context about timing and opted to include these studies, as it did not appear that they were done prior to 2006. Reviews and editorials were also excluded, though their references were checked for additional manuscripts missed in our initial searches.

Data presented here include year(s) of study; country or regions of study; study population size, recruitment methods, and composition (including ages and methods to describe “health”); methods used to generate RIs; number, type, and category of analytes included; and whether comparisons were made with international findings and how these comparisons were presented (e.g., were they quantified by presenting the number of ‘out of range’ values when compared against another RI range? Were statistical tools employed to test reported RIs against existing ranges?). Bias was assessed by a narrative evaluation of selected study populations and statistical methods. Analytes are listed individually and broadly grouped into 8 categories in Table 1, including hematology, immunology/ lymphocyte subsets, liver/pancreas function, kidney function, blood gas parameters, serum electrolytes, lipid parameters, and others (including thyroid tests, diabetes, tumor markers, markers of inflammation, etc.). A list of abbreviations is shown in Table 2. Text on participant health and RI comparisons shown in Table 3 are often copied or paraphrased directly from the source manuscript.

Table 1. Categorization of reported parameters in 80 manuscripts of RIs in Africa.

| Parameter family | Parameters measured | Number (%) of studies with these parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Hematology Parameters | Total white cell count (including either three or five part differential), hemoglobin, platelet count, platelet distribution width, platelet larger cell ratio, plateletcrit, mean corpuscular volume, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, red blood cell count, RBC distribution width by standard deviation, hematocrit, serum iron, unsaturated and total iron binding capacity, serum transferrin, percent transferrin saturation, activated partial thromboplastin time, prothrombin time, D-dimer, ferritin, mean platelet volume, reticulocytes | 66 (83%) |

| Liver and Pancreas Function Chemistry Parameters | Aspartate amino transferase, alanine amino transferase, alkaline phosphatase, albumin, total protein, gamma (γ) glutamyl transferase, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, lipase, amylase, lactate dehydrogenase | 32 (40%) |

| Renal Function Chemistry Parameters | Blood urea nitrogen, serum cystatin C, creatinine, uric acid | 30 (38%) |

| Immunological/ Lymphocyte Subset Parameters | Immunoglobulins (e.g., IgM, IgG, IgA), complement component 3, lymphocyte subsets (e.g., CD4+, CD8+, CD3+, CD3+/CD4+, CD3+/CD8+, CD3-/CD56+, CD16+/56+, CD3+/HLA DR+, CD3+/CD4+/HLA DR+, CD3+/CD8+/HLA DR+, CD3+/CD4+/45RA+, CD3+/CD4+/45RO+, CD3+/CD8+/45RA+, CD3+/CD8+/45RO+, CD19+) | 23 (29%) |

| Lipid Metabolism Parameters | Triglycerides, cholesterol (total, HDL, LDL), | 17 (21%) |

| Serum Electrolyte Parameters | Bicarbonate, sodium, potassium, chloride, phosphate (Inorganic phosphorus), calcium, magnesium | 17 (21%) |

| Blood Gas Analysis Parameters | pH, Partial pressure of oxygen, carbon dioxide | 5 (6%) |

| Other Chemistry Parameters / Markers | Creatine kinase, blood glucose/fasting blood glucose, prostate-specific antigen, uric acid, C-Reactive Protein, thyroglobulin, thyroid stimulating hormone, free thyroxine, free triiodothyronine, folate, vitamin B12, lactate to pyruvate ratio, Cholinesterase, Free T4 (thyroxine), Free T3 (tri-iodothyronine) | 15 (19%) |

Table 2. List of abbreviations.

| 2HPP | 2-hour post-glucose plasma glucose (2HPP) |

| ALB | Albumin |

| ALP | alkaline phosphatase |

| ALT | alanine aminotransferase |

| aPTT | activated partial thromboplastin time |

| AST | aspartate amino transferase |

| BUN | blood urea nitrogen |

| C3 | complement component 3 |

| CBC | complete blood count |

| CK | creatine kinase |

| Cl | chloride |

| CO2 | carbon dioxide |

| Cr | creatinine |

| CRP | c-reactive protein |

| FBS | fasting blood sugar |

| Fe | iron |

| GGT | gamma-glutamyl transferase (γ-GTP) |

| Hb | hemoglobin |

| HCO3 | bicarbonate |

| Hct | hematocrit |

| HDL | high density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| K | potassium |

| LDH | lactate dehydrogenase |

| LDL | low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| MCH | mean corpuscular hemoglobin |

| MCHC | mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration |

| MCV | mean cell volume |

| MID | basophils, eosinophils, and monocytes |

| MPV | mean platelet volume |

| Na | sodium |

| NK | natural killer cells |

| NRBC | nucleated red blood cell count |

| PCT | plateletcrit |

| PCV | packed cell volume |

| PDW | platelet distribution width |

| P-LCR | platelet larger cell ratio |

| PT | prothrombin time |

| RBC | red blood cells / erythrocytes |

| RDW | red cell distribution width |

| TF | transferrin |

| TG | triglycerides |

| U | Urea (BUN) |

| UA | uric acid |

| VCT | HIV counseling and testing (i.e., HCT) |

| WBC | total white blood cell count / leukocytes |

| γ-GTP | γ-glutamyl-transferase (GGT) |

Table 3. Listing of 80 manuscripts of RIs in Africa including details on year(s) of study, size, population and recruitment, parameters measured (see Table 2 for abbreviations), and any reported comparisons with other RIs.

| References | Years of study | Country/ies of study | N | Study population, recruitment, and type* | Ages** | Definition of "healthy" *** | Parameters measured | RI Methods **** | Analysis platforms | Comparisons across RI data sets / data sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kone 2017 [18] | 2004–2013 | Mali | 213 | Adults recruited at University Teaching Hospital, limited description of recruitment | 18–59 | We defined a healthy volunteer, as a participant with no clinical evidence of TB or HIV and no physical symptom of illness for more than 2 weeks before enrollment, including no evidence of fever, or weight loss. No laboratory screening tests reported | WBC, RBC, Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW, Plt, MPV, Neutrophils, Lymphocytes, Monocytes, Eosinophils, Basophils, CD4+, CD8+ T cells | Other | Coulter counter analyzer (Coulter Ac T diff, Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL); FacsCalibur (FASCalibur, BD, Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) | The authors reported that the hematological parameters’ ranges were mostly different to the universal established ranges (instrument-provided RIs) and presented in a table against values from Togo, Burkina Faso, The Gambia, Nigeria, Mozambique, Tanzania, Ethiopia, and Uganda. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences were not quantified. |

| Alemnji 2010 [19] | 2006 | Cameroon | 501 | Adults from urban and rural areas responding to call for VCT (rural) and blood donors (urban) | 18–59 | Participants with the following outcomes that could affect the serum biochemical parameters were excluded from the study (75 out of the 576 initial participants): pregnancy, HIV-positive status, hepatitis B/C infection, malaria, and urine glucose | AST, ALT, ALP, Creatinine, Total Protein, Albumin, Triglyceride, HDL Cholesterol, LDL Cholesterol, Total Cholesterol, Total Bilirubin, Direct Bilirubin | Other | Not reported | The authors present their results compared to those from 5 clinical laboratories in Cameroon. The authors describe these RIs as "based on values obtained in various kits standardized on foreign populations." They also note their methods were comparable to a study done in Rwanda, but do not present specifics regarding differences. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table (except the data from Rwanda, which was not presented), differences were not quantified. |

| Kumwenda 2012 [20] | 2006–2007 | Malawi & Uganda | 541 | Infants consecutively identified at the time of birth before discharge of mothers from the hospital or at postnatal maternal–child health clinics | 0-6m | Healthy, full-term newborns weighing >2.5 kg, HIV negative mothers | CD4+, CD8+ T cells, Eosinophil, Lymphocyte, Monocyte, Neutrophil, Basophil, White blood cells, Red blood cells, Platelets, Hemoglobin, Hematocrit, Sodium, Potassium, GGT, Creatinine, CO2, Chloride, BUN, Bilirubin total, AST, ALT, ALP | Other | Beckman–Coulter AcT5 Part Diff (California, USA); Malawi only: Beckman–Coulter CX5 Chemistry analyser (Brea, California, USA); Uganda only: COBAS Integra 400+ (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) | The authors used the USA-published text book Harriet Lane Handbook: A Manual for Pediatric House Officers as the reference intervals for comparison. For example, mean haemoglobin and haematocrit values of Malawian and Ugandan infants in this study were consistently lower than those of Caucasian infants after the first week of life. The authors refer to another study where these results are presented against the DAIDS toxicity tables (but no RIs were presented) and many values were found to be out of range. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences were not quantified. |

| Buchanan 2010 [21] | 2006–2008 | Tanzania | 655 | Children and adolescents enrolled from vaccination, ANC and other clinics | birth-11m, 1–4, 5–12, 13–17 | Healthy Tanzanian children/adolescents, HIV negative, with no clinically apparent acute or chronic illness, were not currently on any medications, or were pregnant | Hemoglobin, Hematocrit, MCV, Platelets, WBC, RBC, Lymphocyte, Neutrophils, Monocytes, Eosinophils, Basophils, CD4+, CD8+ T cells | CLSI | Beckman Coulter AcT 5 Diff (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA); FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) | The authors compare their results to Ugandan data, and data from the USA and Europe. The authors describe differences across many parameters between their RIs and the comparator RIs. In the discussion, the authors also apply the U.S. National Institute of Health Division of AIDS (DAIDS) adverse event grading criteria commonly used in clinical trials to their RIs. They found that 128 (21%) of 619 children would be classified as having an adverse event related to Hb level, with 10% grade 1 (mild), 7% grade 2 (moderate), and 3% grade 3 (severe), yet 88% of them would be within this Tanzanian normal 95% reference interval. Further, 13% of all the children in our study would be classified as having an ANC related event. Even more notable, 29 (27%) of 109 healthy infants <12 months would be classified as having an ANC-related toxicity, with all but three being within the normal 95% reference interval for this population. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences between Ugandan, US, European data were not quantified, out of range values were calculated against DAIDS criteria. |

| Humberg 2011 [22] | 2006–2008 | Gabon | 226 | Infants and children screened for malaria vaccine trial | 4-9w, 18-60m | Healthy children; excluded: acute or serious chronic disease, recent use of investigational or nonregistered drugs, administration of immunoglobulins, blood transfusions within 3 months preceding the blood sampling, administration of immunosuppressants within 6 months prior to blood sampling, same sex twin, a family history of congenital or hereditary immunodeficiency, history of splenectomy, major congenital defects, weight-for-age z-score <-2, systemic infections, diarrhea, otitis media, antibiotic treatment up to 8 days before blood sampling, burns and large abscesses. Mild skin diseases or mild infections (e.g. rhinitis, conjunctivitis) were not exclusion criteria. No laboratory screening tests reported | RBC, Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, PLT, WBC, LYM, MON, NEU, EOS, BAS, GPT, Cr | CLSI | ABX Pentra 60 analyser; ABX MIRA PLUS analyser | The authors compared their results to those from two European textbooks from 1998 and 2005, published in Germany. Compared to European populations, values for several red cell parameters (hemoglobin, hematocrit, red blood cell count, mean corpuscular volume) were lower and platelet counts were higher. Eosinophils were higher in the older age group, most likely caused by intestinal helminths. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences were not quantified. |

| Odutola 2014 [23] | 2006–2010 | The Gambia | 675 | Infants of mothers attending Infant Welfare Clinic of periurban Health Centre were invited to participate | 3–10m | Apparently healthy children with no clinically significant acute or chronic illness (e.g., no malaria or diarrhea in past week), samples checked for parasites, Included small number (17) of wasted children | Hemoglobin, red blood cell count, white blood cell count, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, platelets, mean corpuscular volume, Potassium, Chloride, Urea, Creatinine, AST, ALT, ALP, Bilirubin | Other | CELL-DYN 3700 sample loader (ABBOTT, USA); VITROS 350 Analyzer (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, USA) | The authors compared their RIs to those from two textbooks (published in the USA), and compare to data from Nigeria and Tanzania in very broad terms in the discussion section. Their set of hematological and biochemical reference values for healthy infants in The Gambia differs from values in other settings. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences were not quantified. |

| Gitaka 2017 [24] | 2007 | Kenya | 1493 | Children enrolled in RTS,S clinical trials | 4w-7m | No serious acute or chronic illness as determined by history and physical examination (defined as not having any signs and symptoms of disease, ambulatory (children older than 1 year) and not underweight, defined as weight-for age Z score (WAZ) -2), medical history records or laboratory screening tests were eligible, no history of allergic reactions, previous blood transfusion, major congenital defects, or HIV disease Stage III or Stage IV. No laboratory screening tests reported. | Hb, Hct, MCHC, MCV, platelets, WBC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, ALT, Cr | CLSI | Beckman Coulter AcT 5 Diff Haematology Analyzer (Beckman Coulter, USA); Vitalab Selectra-E clinical chemistry analyser (Vital Scientific (Merck), Netherlands) | Findings were compared with published ranges from Tanzania, Europe and The United States. reference ranges in infants largely overlapped with those from United States or Europe, except for the lower limit for Hb, Hct and platelets (lower); and upper limit for platelets (higher) and hematocrit (lower). Community norms for common hematological and biochemical parameters differ from developed countries. No statistical testing was reported. Selected comparisons were reported in a table (not all RIs were shown), differences were not quantified. |

| Segolodi 2014 [25] | 2007–2010 | Botswana | 1786 | Adults screened for TDF2 study | 18–39 | Healthy Botswana adults, limited definition of "health". excluded positive for HBsAg, HIV-positive, on medication for chronic illness and pregnant/breastfeeding. | Hb, Hct, creatinine, inorganic phosphorus, HCO3, potassium, sodium, chloride, BUN, direct bilirubin, total bilirubin, serum amylase, AST, ALT | CLSI and other | A Sysmex XT1800i hematology analyzer (Symex, Kobe, Japan); Roche Integra 400plus analyzer | The authors compare to BOTUSA (western derived ranges), DAIDS Toxicity grading tables, US RIs, and RIs from eastern and southern Africa. BOTUSA reference ranges would have classified participants as out of range for some analytes, with amylase (50.8%) and creatinine (32.0%) producing the highest out of range values. Applying the DAIDS toxicity grading system to the values would have resulted in 45 (2.5%) and 18 (1%) participants as having severe or life-threatening values for amylase and hemoglobin, respectively. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table and text. |

| Odhiambo 2015 [26] | 2007–2010 | Kenya | 953 | Adolescents and adults, sexually active and screened for observational cohort study to estimate HIV incidence | 16–17, 18–34 | Excluded HIV, pregnancy. Tested for HSV-2 and other STI (data not reported). Enrollees from in an observational prospective cohort study known as the Kisumu Incidence Cohort Study. Had to be "healthy" (not defined) | WBC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, RBC, Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, platelet counts, ALT, Cr, BUN | CLSI | Coulter ACT 5Diff CP analyzer (Beckman Coulter, France); Cobas Integra 400 plus biochemistry analyzer (Roche, Germany) | The authors compared their RIs to published region-specific reference intervals (western Kenya and the USA) and the 2004 NIH DAIDS toxicity tables. They found that while 10% would be classified as abnormal by local parameters, >40% would be if using the US DAIDS. Blood urea nitrogen was most often out of range if US based intervals were used: <10% abnormal by local intervals compared to 83% (men) and 95% (women) by US based reference intervals. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table and text. |

| Mine 2012 [27] | 2008 | Botswana | 261 | Adults recruited from HIV testing centers around the capital city | 18–66 | Apparently healthy HIV-negative volunteers, excluded via screening questionnaire: pregnant, breastfeeding, inpatients in a hospital or subjectively ill during the last month, rec’d medical treatment (no time specified), recent or recurrent infection, including HIV and malaria, smoked in the hour before blood was drawn, donated blood in the preceding month | WBC, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils, basophils, a 14-parameter hemogram, integral reticulocyte analysis that includes an immature reticulocyte fraction, NRBC, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW-SD | CLSI | FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, California); Sysmex XE-2100 (Sysmex, Kobe, Japan) | The authors compare their results to those from blood donors also from Botswana, as well as volunteers from eastern and southern Africa (Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda and Zambia), Ethiopia, Uganda, and the USA. Their hemoglobin reference intervals were generally higher than in East Africa, but lower than those from Ethiopia and US-based comparison populations. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences were not quantified. |

| Kueviakoe 2011 [28] | 2008 | Togo | 1349 | Adult blood donors, no description of recruitment. | 17–58 | Being "healthy" was not explicitly reported as a requirement in the methods. Negativity of all serological tests for viral infections (not specified) and for malaria, normal hemoglobin electrophoresis screening, and absence of hypochromia on peripheral blood smear. | WBC, RBC, hemoglobin, hematocrit, MCV, MCH, MCHC, platelets, neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophils, basophils, monocytic cells | Other | Sysmex SF-3000 automated hematology analyzer | The authors compared their RIs to those from Uganda, Central African Republic, Ethiopia, South Africa, Gambia, Kenya, and Tanzania. The median values are similar to the ones found in other studies performed in Africa and even in northern countries (data are not shown). The ranges of different parameters are often different especially for RBC considering the influence of alpha-thalassemia and iron deficiency. The reason for lower absolute neutrophil count is still unclear. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences were not quantified. |

| Woldemichael 2012 [29] | 2008–2009 | Ethiopia | 1965 | 1965 adults randomly selected from population based survey of NCD (same as Haileamlak 2012). | 15–64 | Included all apparently healthy individuals (not defined); disabled and acutely ill during the data collection were excluded. No laboratory screening tests reported | Total cholesterol, triglycerides, total serum protein, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, uric acid, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase | Other | Human star 80 (Gesellschaft fur Biochemica und Diagnostica, Germany) | Presented in the discussion, the authors compare their findings to RIs from Cameroon, East and Southern Africa, and a textbook (based on western values). No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences were not quantified. |

| Haileamlak 2012 [30] | 2008–2009 | Ethiopia | 1965 | 1965 adults randomly selected from population based survey of non-communicable diseases (same as Woldemichael 2012). | 15–64 | Included all apparently healthy individuals (not defined); disabled and acutely ill during the data collection were excluded. No laboratory screening tests reported | Hb, Hct, RBC, MCV, MCH, MCHC, WBC count (including neutrophils, mixed white cells, lymphocytes), platelet count, CD3+, CD4+, CD8+ T cells | Other | KX-21 hematology analyzer, (Sysmex Coporation, Germany); FACS system (Becton Dickinson San Jose California, USA). | Presented with limited descriptions in the discussion, the authors compare their results to RIs from Turkey, Uganda, Malaysia and the textbook Harrisons Principles of Internal Medicine (published in the USA). No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences were not quantified. |

| Santana-Morales 2013 [31] | 2008–2010 | Ethiopia | 454 | Adults and children attending health screening at rural hospital, limited description of recruitment. An additional 117 persons with malaria described in this paper were not considered for this review. |

1–5, 6–12, 13–98 | The following categories were excluded: pregnant, malaria infected (except comparison group), HIV-positive and intestinal helminth-positive. | Hemoglobin | CLSI | Hemo-Control EKF Diagnostic Analyser | The RIs for the Gambo General Rural Hospital population in this study were compared with parameters obtained from other African populations and with parameters set by WHO. In general, the lower limits for adult hemoglobin range obtained from this population were slightly higher than those derived from Kenya, Uganda and Gambia, but were equal to those established by another study in Ethiopia and the hemoglobin range established by WHO (2011). In the child populations, the minimum values were lower than those obtained from different African populations and those established by WHO. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences were not quantified. |

| Schmidt 2018 [32] | 2008–2012 | South Africa | 634 | Infants recruited for TB clinical trials from general population using vaccination clinic records, birth registers and referrals from community contacts and other participants. | 3-6m | BCG vaccinated at birth, HIV-unexposed, neither a maternal history of tuberculosis disease or exposure to infectious household contact, confirmed by either negative TST or IGRA. General good health & weight at the time of screening. No laboratory screening reported. | White blood cell count, Red blood cell count, Hemoglobin, Hematocrit, mean corpuscular volume, Mean corpuscular hemoglobin, Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, Platelet count, Total bilirubin, Alkaline phosphatase, Gamma-glutamyl transferase, Alanine transaminase, Aspartate transaminase | CLSI | Sysmex XN10 instrument (manufactured in Germany); Roche Cobas 6000 instrument (manufactured in Japan) | The authors calculated the percentage of observed values out of bound (in terms of lower and upper limits) compared to NHLS laboratory RIs (derived from Caucasian subjects) and found that parameters in apparently healthy South African infants deviate frequently from these RIs, including abnormalities consistent with subclinical hypochromic microcytic anemia. 91% of platelet values were higher than the NHLS RIs and over half, 55% and 57%, had MCV and MCH values below the lower limits of the NHLS RIs; 4 other RIs had significant (>10%) numbers of values out of range. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, figures, and text. |

| Gelaye 2011 [33] | 2009–2010 | Ethiopia | 1807 | Adult employees of the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia and teachers in government schools from the capital city. A multistage, probabilistic stratified random sampling strategy was used to identify and recruit participants. | 18–60 | subjects were excluded from these analyses if they were currently pregnant or on medication. Subjects older than 60 years of age were also excluded. No laboratory screening tests reported | WBC, RBC, hemoglobin, hematocrit, MCV, MCH, MCHC, platelets, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils | CLSI | Not reported | No |

| Sagnia 2011 [34] | 2009–2010 | Cameroon | 352 | Children from Yaoundé township were recruited by healthcare assistants at the vaccination unit and by township social assistants. | birth-6y | A child was considered healthy when there was no history infectious diseases or hematological and immunological disorders. The parent or guardian of each participant completed a questionnaire. Participants were assessed for signs of febrile illnesses, active infection, malnutrition, and clinical AIDS. exclusion criteria were concurrent illness and/or medication, an axillary temperature of 38°C, malnutrition (weight for height of <70%), an unknown date of birth, and known HIV/AIDS infection. Blood samples were rejected if they were HIV infected or plasmodium positive | Lymphocyte subset reference values CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, CD19+, NK, 4/DR/38, 4/DR, 4/38, 8/DR/38, 8/DR, 8/38, 3/4/RO, 3/4/RA, 4/RO, 4/RA, 3/8/RO, 3/8/RA, 8/RO, 8/RA, 4/RA/62L, 8/RA/62L | Other | FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) | The authors compared their results to selected results from USA, The Netherlands, Malawi, Kenya, Saudi Arabia, Ethiopia, Zambia, and Uganda. Normal lymphocyte subsets values among children from Cameroon differ from reported values in Caucasian and some African populations. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences were not quantified. |

| Dosoo 2014 [35] | 2009–2010 | Ghana | 1442 | Children and adolescents randomly selected from DSS. | 0.5–4, 5–12, 13–17 | General good health as determined by a clinician using medical history and physical examination, excluded adolescent pregnant females. Children with evidence of acute or chronic respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, hepatic, or genitourinary conditions; history of blood donation/transfusion within three months preceding the survey; hospitalization within a month preceding the survey; or any other findings that in the opinion of the examining clinician may compromise the assessment of the laboratory parameters of interest in this study were excluded. No laboratory screening tests reported. | ALT, AST, Amylase, CK, GGT, LDH, total Protein, Albumin, total Bilirubin, Direct Bilirubin, Cholesterol, Glucose, Iron, Triglycerides, Urea, Creatinine, Uric acid, Chloride, Phosphorus, Potassium, Sodium, Hemoglobin, Hematocrit, RBC, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW, Platelets, PDW, Total WBC, Lymphocytes, Monocytes, Granulocytes | CLSI | ABX Micros 60 Hematology Analyzers (Horiba-ABX, Montpellier, France) | The authors compared their results to those from Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, an unnamed "Western country", and lower limits provided from the WHO (presumably from "developed countries"). Hemoglobin, hematocrit, mean cell volume, erythrocytes, urea, and creatinine were lower when compared with values from northern countries but alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and total bilirubin were higher. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were presented in a table; differences were not quantified. |

| Buchanan 2015 [36] | 2009–2011 | Tanzania | 619 | Infants, children and adolescents enrolled from schools and clinics; outreach at places of worship. | 1m-1y, 1–4, 5–12, 13–17 | No fever, no physical complaints, not ill on exam, no chronic illnesses, or meds, not pregnant, HIV negative | Albumin, alkaline phosphatase, ALT, AST, amylase, total bilirubin, calcium, cholesterol, creatinine kinase, bicarbonate, chloride, creatinine, glucose, HDL, LDL, potassium, lipase, phosphorus, magnesium, sodium, total protein, triglycerides, urea | CLSI and other | Cobas Integra 400 plus biochemistry analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Germany) | The authors compared their data to the USA-published Harriet Lane Handbook and the US National Institutes of Health Division of AIDS (DAIDS) grading criteria for classification of adverse events. They found that for selected parameters, up to 15% or more of infants or children in certain age groups would have been categorized as having an adverse event as defined by DAIDS. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were presented in a table and quantified in the text. |

| Tembe 2014 [37] | 2009–2012 | Mozambique | 257 | Young adults participating in a study of the prevalence and incidence of sexually transmitted viruses at the youth-friendly clinic, Maputo Central Hospital. | 18–24 | Volunteers who were febrile, pregnant, or seropositive for HIV, syphilis or hepatitis B surface antigens were excluded from the study. No other description of "healthy" reported | WBC, RBC, platelets, lymphocytes, neutrophils, Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW-SD, RDWCV, PDW, MPV, P-LCR, lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, basophils, eosinophils, creatinine, total bilirubin, albumin, AST, ALT, glucose, urea, uric acid, amylase, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, ALP | CLSI and other | Sysmex KX-21N Hematology Analyzer (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan); Vitalab Selectra Junior (Vital Scientific, Dieren, Netherlands) | The authors compared their results to those from Uganda, Kenya, USA and the 2004 DAIDS toxicity tables. They found that their immunology ranges were comparable to those reported for the US and western Kenya. Hematologic values differed from the US values but were similar to reports of populations in western Kenya and Uganda. The chemistry values were comparable to US values, with few exceptions. However, as many as 69% would be ineligible for trial participation, when screened against the DAIDS tables. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were presented in a table and differences vs. DAIDS table were quantified. |

| Ouma 2021 [38] | 2009–2014 | Kenya | 1,509 | 1509 (53% female) of 1631 Infants participating in GSK phase3 malaria vaccine trial which enrolled volunteers from a local Health and Demographic Surveillance System to ensure a representative sample (no details on the sampling strategy were reported) | 1m-17months | Data from a trained physician-conducted physical examination were reviewed as per the trial procedures to include healthy infants without acute or chronic, clinically significant pulmonary, cardiovascular, hepatobiliary, gastrointestinal, renal, neurological, mental or hematological functional abnormality or illness that required medical therapy. Data included medical history, physical examination (blood pressure, weight, pulse, Z score and vital signs) or clinical assessment before being enrolled into the study. Data from children who had recurrent infection, fever, including HIV (or maternal exposure to HIV) and malaria or severe anemia, defined as hemoglobin level of <5.0g/dl or hemoglobin concentration of <8.0g/dl associated with clinical signs of heart failure and/or severe respiratory distress or those receiving medical treatment at the time of sample collection were excluded from the study. | WBCs, RBCs, HGB, HCT, platelets, granulocytes, lymphocytes, and monocytes were directly measured. MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW and MPV were extrapolated. The analyzer did not give separate counts of neutrophils, basophils and eosinophils. | CLSI | three-Part differential Coulter counter hematology analyzer | Includes comparisons with data from Kilifi (coastal Kenya), Tanzania, USA/Europe. The sources of data from Tanzania and USA/Europe were unclear, and no distinction was made between data from USA and Europe (unclear if data are combined, or which data are from which region). No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences were not quantified. |

| Abera 2012 [39] | 2010 | Ethiopia | 405 | Adult attendees to VCT center in regional referral hospital. | 18–60 | Negative for anti-HIV antibodies, non-pregnant women, nonsmokers, Body Mass Index (BMI) ≥18.5 kg/m2, no history of current or recent morbid conditions such as gastrointestinal tract infections, active tuberculosis, no major surgery, no medication or allergy to drugs, no autoimmune diseases, and no history of blood transfusion | CD4+, CD8+ T cells, WBC, neutrophils, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, some precursor cells, RBC, Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, Platelets | Other | FACS Count (Becton Dickinson, USA); Cell-DYN 1800 (Abbott Lab., USA). | Compared with accepted reference value of the National ART Laboratory [the source of which is not specified], 62 (21.4%), 30 (7.4%) and 36 (8.8%) of the participants had lower than the lower ranges of CD4+ T cells, platelets and leucocytes, respectively. The authors reported using ANOVA and chi squared tests to determine if out of range values differed by gender and found a statistically significant difference between males and females, where 21.5% males and 6.6% females had CD4+ T cells below the normal values (<500 cells/mm3) (P = 0.001). Table 3 shows comparison of the medians and means of the present study with results of earlier studies in Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania; data are presented in a table but no statistical testing is done to compare their ranges to these RIs. The authors recommend the National ART Laboratory guidelines be reevaluated for CD4+ T Cells, but that for hematology they remain acceptable. Comparisons are reported in a table and text. |

| Okonkwo 2015 [40] | 2010 | Nigeria | 304 | Adults recruited using age and gender stratified random sampling to ensure that participants from each Local Government Council matched the overall population structure. | 20+, mean age 50 no upper limit given | Generally of good health with no evidence of a chronic or acute illness on clinical examination, excluded: Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, stroke, kidney disease, family history of kidney disease, significant proteinuria (urine dipstick protein ≥1+ equivalent to approx. 30 mg/dL), liver disease, and pregnancy. No laboratory screening tests reported | Serum Cystatin C, SCr, blood glucose | IFCC | Humalyzer 2000 Chemistry analyzer (Human GmBH Diagnostica Worldwide, Wiesbaden, Germany) | No |

| Palacpac 2014 [41] | 2010 | Uganda | 140 | Children, adolescents, and adults in a Phase Ib trial for malaria vaccine following outreach via radio and schools | 6–10, 11–15, 16–20, 21–32 | Healthy, with no obvious symptoms/signs of either acute or chronic respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, hepatic or renal disease; no history of blood donation/transfusion within one month and, for females, non-lactating and tested for pregnancy (though not explicitly listed as exclusion criterion). Blood checked for malaria (test not reported). | WBC, RBC, Hb, Hct, platelet count, ALP, ALT, AST, γ-GTP, amylase, albumin, total protein, total bilirubin, cholesterol, glucose, creatinine, BUN, uric acid, potassium, sodium | CLSI | Sysmex KX-21N (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan); Cobas C111 (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) | No |

| Melkie 2012 [42] | 2010–2011 | Ethiopia | 117 | Newborns and infants attending OBGYN and vaccination clinics, respectively, limited description of recruitment | newborns & infants | Newborns over 37 weeks of gestation, ≥2500 g birth weight and no history of fetal problems. Preterm newborns, newborns with <2500 g birth weight, newborns requiring intensive resuscitation and care, newborns from mothers with documented antenatal or intra-partum complications (gestational diabetes, HIV, hepatitis B/C, eclampsia, etc.), have organic diseases and other diseases that alter their biochemical profile, have taken medications that can affect their biochemical profile were excluded. Structured questionnaires were used in both cases for the collection of selected demographic information. | Albumin, AST, ALP, direct bilirubin, total bilirubin, ALT, GGT | CLSI | HumaStar 300 analyzer (Human diagnostics worldwide, Germany) | Upon comparison of the RIs obtained from this study with previously reported values of similar age group (assay package insert RIs, and two studies from Canada), visually significant differences were seen. The values were also different from respective adult values determined for adult Ethiopian population (see reference Table 8). No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences were not quantified. |

| Samaneka 2016 [43] | 2011 | Zimbabwe | 769 | Adults, cross-sectional, representative multistage random sample of 3 regions (same study, different population as Gomani 2015) | 18–55 | Healthy, no history, clinical or laboratory evidence of chronic disease (hypertension, diabetes, liver, renal), HIV and HBsAg negative. No reported medications for acute illness (or were within one week past completion of a course of medication) with no abnormal findings on clinical and laboratory examination | White cell count, hemoglobin, automated five part differential, platelet count, MCV, MCHC, MCH, red blood cell count, hematocrit, sodium, potassium, chloride, phosphate, creatinine, creatinine kinase, calcium, urea, AST, ALT, ALP, albumin, total protein, GGT, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, bicarbonate, triglycerides, lipase, cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, glucose | CLSI | Sysmex XT2000I (Symex Europe D-22848Nordersted, Germany); Hitachi 902 (Hitachi, Roche diagnostics D-68292 Mannheim Germany) | No |

| Gomani 2015 [44] | 2011 | Zimbabwe | 302 | Adolescents, community based, using multistage random sampling technique (same study, different population as Samaneka 2016) | 12–17 | Screened for HIV and Hepatitis B. Excluded those with chronic medical conditions like diabetes (no additional details provided). All participants had a physical examination performed by the study physician before enrollment into the study | White Cell, Red Cell, Hemoglobin, Hematocrit, MCV, MCH, MCHC, Platelets, Neutrophil, Lymphocyte, Monocytes, Eosinophil, Basophil, Red blood Cell distribution width, Urea, Sodium, Potassium, Chloride, AST, ALT, ALP, Amylase, Total Protein, Albumin, GGT, Total Bilirubin, Phosphate, Calcium, Bicarbonate, Triglycerides, Creatinine, Lipase, Cholesterol, LDL-C, HDL-C, Glucose, Direct Bilirubin | CLSI | Sysmex xt2000i (Sysmex Europe Norderstedt, Germany). Hitachi 902 (Hitachi, Roche Diagnostics Mannheim, Germany) | No |

| Beavogui 2020 [45] | 2011–2013 | Guinea | 450 | Children, adolescents and adults, no description of recruitment. Some enrolled for 3 visits, across seasons. | 6–10, 11–15, 16–45 | Apparently healthy clinically (this was not described), not pregnant. Everyone was tested for malaria, but test was not reported. | WBC, RBC, Hemoglobin, Hematocrit, MCV, MCH, MCHC, Platelet, MPV, Lymphocytes, Monocytes, Neutrophils, Eosinophils, Basophils, AST, ALT, Total Bilirubin, Creatinine | CLSI | ABX Pentra 60 Hematology Analyzers (Horiba-ABX, Montpellier, France); Piccolo® xpress™ Chemistry Analyzer (USA) | No |

| Odhiambo 2017 [46] | 2011–2014 | Kenya | 120 | Pregnant women, self-selected, seeking ANC care. Prospective/ follow up. | 14–44, no age strata | HIV uninfected, pregnant, with a plan to remain in the area until at least 9 months postpartum, willing to have serial visits at maternal child health clinic with serial HIV testing through 9 months postpartum, not on medication that could alter hematological parameters, and no clinical evidence of malaria and helminth infections | ALT, AST, Bilirubin, Cr, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, Hct, Hb, MCV, RBC, WBC, Neutrophils, Monocytes, Lymphocyte count, Basophils, Eosinophils, Platelets | CLSI | Coulter ACT 5Diff CP analyzer (Beckman Coulter, France) | The authors compared their results to non-pregnant values from Kenya and the US, as well as the 2004 DAIDS Toxicity Tables, using the Wilcoxon text. There were substantial differences in U.S. and Kenyan values for immune-hematological parameters among pregnant/postpartum women, specifically in red blood cell parameters in late pregnancy and 2 weeks postpartum. Using the new hemoglobin reference levels from this study to estimate prevalence of `out of range’ values in a prior Kisumu research cohort of pregnant/postpartum women, resulted in 0% out of range values, in contrast to 96.3% using US non-pregnant reference values. Comparisons were reported in a table and the text. |

| Pennap 2011 [47] | Not reported | Nigeria | 444 | University students, no description of recruitment. | 15–44 | Participants who were either HIV-, HBV- or HVC-positive or who had apparent signs or symptoms of ill-health were excluded from the study. Volunteers who indicated that they were on immunomodulatory drugs or had a history of idiopathic CD4þ T-lymphocytopenia were also excluded. | CD4+ T cells | Other | BD FACScount cytometer | No |

| Maphephu, 2011 [48] | Not reported | Botswana | 309 | Adult anonymized residual blood samples from blood donors. | 16–60 | A professional health counsellor carries out a pre-donation confidential assessment to determine eligibility to donate blood and prior history of diseases, medications, sexual behavior, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and illicit drugs. All the blood collected was tested for presence of HIV and hepatitis A, B and C viruses, and screened for sexually transmitted infections. | Total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol | CLSI | COBAS Integra 400 | The authors compare the cut-off values of total cholesterol concentration in a table showing their Batswana results and those from North American populations according to recommendations of the Laboratory Standardization Panel of the National Cholesterol Education Program. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences were not quantified. |

| Amah-Tariah 2011 [49] | Not reported | Nigeria | 220 | Pregnant women first time attendees to ANC clinic. | 18–42 | Apparently healthy pregnant subjects. No subject had a history of hematinic or any other mineral supplementation during the present pregnancy prior to recruitment into the study. No subject had a history of vaginal bleeding during the present pregnancy and none had received any form of blood transfusion within the past eight months. No laboratory screening tests reported. | Serum iron, iron binding capacity, serum transferrin, percent transferrin saturation, red cell distribution width, platelet count, mean platelet volume, platelet distribution width, plateletcrit, platelet large cell ratio | Other | Prestige 24i automated clinical analyzer (Tokyo Boeki Medical System Ltd. Tokyo, Japan) | No |

| Mugisha 2016 [50] | 2012–2013 | Uganda | 903 | Older adults in General Population Cohort study participating in anemia survey. Limited description of recruitment. | 50–64, 65+, 8% > = 80 | Participants were excluded if they were too ill to answer questions or couldn’t remember their age. Tested for malaria, hookworm, HIV as exclusionary criteria. | Hemoglobin, Hematocrit, Erythrocytes, Platelets, WBC, MCH, MCV, MCHC, Neutrophils, Lymphocytes, Monocytes, Eosinophils, Basophils | CLSI | Beckman Coulter AC.T 5 diff CP Haematology analyzer (Beckman Coulter, USA) | Compared to the reference intervals from old people in high income countries (Australia, China and two studies from USA), all the hematology parameters from this study population were low, with the exception of MCV values compared to the study from China. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences were not quantified. |

| Okebe 2016 [51] | 2012–2013 | The Gambia | 1141 | Children randomly selected from DSS for 2 cross sectional surveys before and after rainy season. No attempts were made to exclude a child based on participation in the previous survey. | 12–59m | The medical history taken by the team nurse focused on any episode of illness such as fever, frequent watery stools, and antibiotic use in the preceding two weeks, blood transfusions or any known medical condition such as sickle cell disease. A brief physical examination comprised of axillary temperature measurement, weight and height measurements, auscultation of the chest and abdominal palpation for enlarged spleen or liver was also done. Only fever was explicitly mentioned as exclusion criteria, febrile recruits (only) were screened for malaria by RDT. No laboratory screening tests reported. | WBC, lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, hemoglobin, platelets, sodium, potassium, urea, creatinine, AST, ALT, total protein, albumin | CLSI | Quintus 5-part Haematology analyzer (Boule Medical AB, Sweden); VITROS 350 analyzer (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, USA) | No |

| Smit 2019 [52] | 2012–2015 | South Africa | 711 | Adults (African, Caucasian and mixed race) recruited from the healthy South African population, no additional description of recruitment. |

18–65, 65+ to analyze variation | Participants were excluded if they suffered from any of the following conditions: (a) diabetes; (b) chronic liver or kidney disease; (c) had blood results which clearly indicated the presence of a severe disease; (d) had been hospitalized or been seriously ill during the previous 4 weeks; (e) donated blood in the previous 3 months; (f) were known carriers of hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV) or HIV; (g) were pregnant or within one year after childbirth; or (h) had participated in a clinical trial in the past 12 weeks. No laboratory screening reported. | Red cell count, Hemoglobin, Hematocrit, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW, White cells, Neutrophils, Lymphocytes, Monocytes, Eosinophils, Basophils, platelets | C-RIDL | Beckman Coulter ACT 5 diff AL analyzer | This study compared RIs within South Africa, between persons of Caucasian, Mixed Ancestry and African descent, ANOVA was used to test differences across ranges. The authors found that white cell, monocyte, neutrophil and red cell indices were significantly different statistically (p<0.05) amongst the three population groups, tending to be lower in Africans than values in persons of Caucasian or Mixed Ancestry (with the exception of some red cell indices, which were significantly different amongst the 3 groups). Comparisons were reported in a table and text. |

| Smit 2021 [53] | 2012–2015 | South Africa | 1,143 | 1,143 apparently healthy volunteers: 551 African and 592 non-African (comprising 383 Caucasian and 209 Mixed Ancestry). No details on sampling strategy reported. | 18–65 | Participants were excluded if they suffered from or had any of the following conditions: (i) diabetes under drug treatment; (ii) reported history of chronic liver or kidney disease; (iii) the presences of a severe disease as indicated by the results obtained in this study; (iv) had been hospitalised or seriously ill during four weeks preceding participation; (v) donated blood in the last three months; (vi) a known carrier state of the hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV) or HIV-positive; (vii) pregnant or within one year after giving birth and (viii) participated in another research study involving an investigational product during the past 12 weeks. | Total Protein, ALB, Urea, UA, Cr, Total Bilirubin, Na, K, Cl, Lactate to pyruvate, Glucose, Calcium, Phosphate, Magnesium, Cholesterol, HDL, LDL, Triglycerides, Thyroglobulin, Thyroglobulin antibodies, Thyroid peroxidase antibodies, Amylase, AST, ALT, LDH, ALP, GGT, CK, Lipase, Cholinesterase, CRP, Fe, Ferritin, TF, IgA, IgG, IgM, Free T4 (thyroxine), Free T3 (tri-iodothyronine), Thyroid-stimulating hormone, Prostate Specific Antigen | C-RIDL | automated Beckman Coulter DXC analyser for the samples obtained between 2012 and 2013 and using a Beckman Coulter AU analyser for the samples obtained in 2014. The analytes that depended on labelled immunoassays were measured by a Beckman Coulter DxI analyser | No |

| Adoga 2012 [54] | Not reported | Nigeria | 1123 | Adults from urban and rural areas, no description of recruitment. | Mean age = 24.4, no ranges given | Participants who were HIV, HBV or HCV positive, or who had apparent signs or symptoms of ill-health were excluded from the study. Pregnant women and volunteers who indicated that they were on immunomodulatory drugs or had a history of idiopathic CD4+ T lymphocytopenia were also excluded. | CD4+, CD3+ T cells | Other | BD FACScount cytometer | No |

| Troy 2012 [55] | Not reported | Zimbabwe | 542 | Infants as part of another study, no description of recruitment. Prospective study. | 3m, 5m, & 9m (same infants) | HIV-infected (PCR), reported as being currently ill on the questionnaire accompanying the blood draw, or with insufficient blood drawn to test for hematologic and immunologic values, were excluded. | WBC, lymphocytes, CD4+ T cells, hemoglobin, MCV, platelets | Other | Sysmex KX-21N Automated Hematology Analyzer (Sysmex Co. Ltd, Kobe, Japan); Partec Cyflow Counter (Partec GmbH, Munster, Germany) | For each value, the percentage of infants with values outside the normal range, as defined by a Text book published in the USA, was calculated. When the age of the study infants did not correspond to those in the reference normal ranges, ranges from adjacent ages were combined using the lowest and highest values to create the broadest range. The presence and degree of toxicities for WBC, hemoglobin and platelets were assessed using the 2009 update of the NIH Division of AIDS 2004 table for the severity of adult and pediatric adverse events. The presence and degree of immunodeficiency by CD4% was assessed using the World Health Organization (WHO) classification for immunodeficiency. Substantial proportions of the platelet counts (44%), hemoglobin results (19%) and mean corpuscular volumes (41%) were outside published normal ranges. The majority (71%) of CD4% values indicated immunodeficiency by World Health Organization criteria. Statistical testing was described but no results are presented. Comparison data are quantified in the text (but not presented in a table or figure). |

| Dosoo 2012 [56] | Not reported | Ghana | 625 | Adults randomly selected from DSS. | 18–59 | General good health as determined by a clinician’s medical history and physical examination, excluded pregnant women. No laboratory screening tests reported | Hemoglobin, Hematocrit, RBC, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW, Platelets, PDW, WBC, Lymphocytes, Monocytes, Granulocytes, ALT, AST, ALP, Amylase, Creatine Kinase, GGT, LDH, Total Protein, Albumin, Total Bilirubin, Direct Bilirubin, Cholesterol, Glucose, Iron, Triglycerides, Urea, Creatinine, Uric Acid, Chloride, Phosphorus, Potassium, Sodium | CLSI | Vitalab Selectra E Clinical Chemistry analyzer (Vital Scientific, The Netherlands); ABX Micros 60 analyzers (Horiba-ABX, Montpellier, France) | The authors compare their results to those from the platform package inserts (i.e., Caucasian), elsewhere in Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania, eastern and southern Africa (Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda and Zambia) and the USA. Compared to other references, the reference values for hemoglobin, hematocrit, red blood cell counts, and urea are lower in the Kintampo study area. Out of range values are shown compared to the package inserts. Using the biochemistry reference values based on the package inserts would have screened out up to 74% (e.g., creatine kinase) of potential male trial participants and >90% (e.g., monocytes) of the population using the hematology parameters. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table and discussed in the text. |

| Asare 2012 [57] | Not reported | Ghana | 4733 | Adults, randomly selected from Urban areas. | 25–65 | Those on medication, pregnant, or those who had diabetes, jaundice or renal failure just to mention a few (complete list not reported), were excluded. No laboratory screening tests reported. | Fasting Blood Glucose, 2HPP, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, TG, UA, U, albumin, ALP | CLSI | Erba Smartlab Automatic Chemistry Analyzer (Erba, TransAsia, India) | Brief mention at the end of the discussion that the wide deviation from the manufacture’s RIs supports our views that local RIs are critical to proper laboratory diagnosis. The assay platforms used in this study are from the UK and from India. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences were not quantified. |

| Chisale 2015 [58] | 2013 | Malawi | 105 | Adult blood donors, no description of recruitment. | 19–35 | Excluded those with detectable blood-borne infections such as malaria, HIV, syphilis, or hepatitis; females who were menstruating, pregnant, or lactating; those with any evidence of acute or chronic illness at the time of the study or in the preceding 3 months; those taking medications for any medical condition; those who smoked tobacco or consumed alcohol or had a current or past history of using illicit drugs; those who had experienced significant blood loss, from any cause (for example, surgery or trauma) within the preceding three months; those who had donated blood within the preceding three months; or those who had received a blood transfusion within the preceding 12 months | WBC counts, neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte, eosinophil, basophil, RBC counts (along with associated variables, such as Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH), platelets counts | Other | Beckman Coulter HmX haematology analyzer | The authors compared their data against reference limits from the machine used, which are based on a European population. The severity of “abnormalities” was classified using the Division of AIDS (DAIDS) criteria. Almost all variables generated some values that were outside the lower and upper reference limits provided by the manufacturers of the machine used. The proportions of out-of-range values ranged from 1.0% (1/105) to 88.6% (93/105). The majority of out-of-range results for Hb concentration and absolute counts of neutrophils, eosinophils and basophils were below the lower reference limits. In contrast, the majority of out-of-range results for platelet and monocyte counts were above the upper reference limits. Up to 55.0% (58/105) of our otherwise healthy study participants would have erroneously been considered to have at least one grade 1–4 hematological adverse event (AE). Some of the abnormal values for Hb concentration, neutrophil count, and platelets were classified as grade 3 (severe) or 4 (potentially life-threatening). No statistical testing was reported. |

| Cumbane 2020 [59] | 2013–2014 | Mozambique | 419 | Adults at high risk for HIV enrolled in cohort study (RV363). | 18–35 | Healthy participants with evidence of malaria, pregnancy, syphilis, hepatitis, and HIV were excluded from this analysis. "Healthy" was not otherwise defined | Total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, ALT, creatinine, glucose, CD3+, CD8+, CD45+, CD4+ T cells, Hemoglobin, Hematocrit, Erythrocytes, Platelets, WBC, MCH, MCV, MCHC, Neutrophils, Lymphocytes, MXD, MPV, RDW_CV, RDW_SD | Other | Sysmex KX21N (Sysmex Corporation, Japan); Vitalab Selectra Junior1 (Vital Scientific, Netherlands); FACS Calibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, USA) | Ranges were compared with those from Mozambique (persons at lower risk for HIV), South Africa, the USA, and the 2014 US National Institute of Health Division of AIDS (DAIDS) toxicity tables. The authors note relative differences across studies and quantify the number of out of range values when compared against the DAIDS tables. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were presented in a table and differences vs. DAIDS table were quantified. |

| Yalew 2016 [60] | 2014 | Ethiopia | 240 | Adult blood donors selected conveniently | 18–50 | The reference individuals were selected based on medical examinations, current health status, blood pressure, taking any medication, working with hazardous chemicals, alcohol intake, presence of inherited health disorder in the family, tuberculosis, lymphadenopathy, weight loss, regular exercise, tobacco smoking, allergy manifestation, fever, malaria, HIV, hepatitis B virus surface antigen, hepatitis C virus antibodies, menstruation, pregnancy and use of contraceptives. | WBC, neutrophils, lymphocytes, eosinophils, monocytes, basophils, platelet count, RBC, Hb, hematocrit, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW | CLSI and other | Cell-Dyn 1800 | The authors compare their results to those from a textbook (Wintrobe’s clinical hematology, derived from a Caucasian population), elsewhere in Ethiopia (Addis Ababa), Burkina Faso, Kenya, Togo, Tanzania, Jamaica, and Eastern and Southern Africa (Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda and Zambia). Median and 95th percentile of WBC for general population were lower than Caucasian population, Addis Ababa, Burkina Faso and Kenya of similar studies. The RBC, Hgb and PCV lower 95% limit values of both sex were lower than studies in Addis Ababa, Kenya, Burkina Faso and text book. While PCV upper limit values higher than the above countries. MCV values of the current study were higher than those countries while MCHC values were lower. Similarly, the absolute values of neutrophils in the current study were lower than Caucasian and Afro Caribbean but higher than African countries and Jamaica but lymphocyte count was higher. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table and text, differences were not quantified. |

| Serena 2019 [61] | 2014 | Mali | 161 | Adult male Malians as they arrived in Italy as immigrants (asylum seekers). | 19–54 | adult Malians, within 3 months of their arrival in Italy as asylum seekers, HBsAg pos, anti-HCV pos, HIV pos excluded. | RBC, Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW, WBC, lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils, platelets, PDW, MPV, PCT, creatinine, glucose, AST, ALT | Other | Sysmex XN 1000 automated hematology analyzer; Dimension Vista 1500 Intelligent Lab System (Siemens) | The authors compared their results to those from the USA (including African Americans), Southern Europe/Italy, Kenya, Mozambique, Ghana, Tanzania, Botswana, Ethiopia, Central African Republic, Rwanda, Zambia, Uganda, Togo, South Africa, and Zimbabwe. The authors note many similarities, and report in the discussion on lower eosinophil and higher monocyte counts were observed in Malians compared to Europeans. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences were not quantified. |

| Ayemoba 2021 [62] | 2014 | Nigeria | 6,169 | 6169 of 7797 consenting male (96.2%) and female (3.8%) military applicants from 37 States of Nigeria. No description of sampling technique | 18–26 | Presence of glycosuria, proteinuria, haematuria and bilirubinuria—and HBV, malaria, HIV, pregnancy—screened out. No description of any screening questionnaires. | Assays performed included liver function tests (Total Serum Proteins, Albumin, Serum Globulin, alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), Alkaline Phosphatase, gammaglutamyl transferase (GGT), Total Bilirubin, Direct and Indirect Bilirubin, Urea, Creatinine, Electrolytes (Na, K, Cl), Lipid profile (Total Cholesterols, HDL, LDL Cholesterols and Triglycerides), Calcium, Phosphate, Uric Acid, serum Lactate and serum Amylase) | CLSI | Selectra Pro-S1 automated clinical chemistry analyzer (Vital Scientific, Elitech Group Company, Netherlands). | Shown against western values (Dosso Ghana, American—Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics 2018, British—Clinical Biochemistry Reference Ranges Handbook 2017) however no quantification of differences made. No statistical testing was reported. |

| Ayemoba 2019 [63] | 2014–2017 | Nigeria | 6153 | Young adults screening for military service across the country. No description of recruitment. | 18–26 | apparently healthy (not described) testing for Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), HIV-1 and 2, malaria and pregnancy as exclusion criteria. | RBC, Hb, PCV, MCV, MCH, MCHC, Plt, WBC | Other | Sysmex KX-21-N hematology auto-analyzer (Sysmex Corporation Inc, Kobe, Japan). | The findings in this study and Western values obtained from Dacie and Lewis Practical Hematology text book are shown in Table 2, while Table 3 shows findings from this study and two neighboring West African countries [Ghana and Togo]. Median platelets count observed in this study (218 x 109/l) was seen to markedly vary from Western Reference values (280 x 109/l) (Table 2). Similarly, MCV was 84fl, 87fl and 85fl in this study and two other West African studies respectively, while Western value was 92fl (Tables 2 and 3). For the rest of the parameters, values from index study, neighboring Western African countries and Western values appeared similar. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table, differences were not quantified. |

| Osunkalu 2014 [64] | Not reported | Nigeria | 365 | Pregnant (n = 294) and not pregnant (n = 71) age-matched women attending the Nigerian Air Force Hospital, no description of recruitment. | Mean ages 28–30, no ranges given | Those with positive history and clinical evidence of past or present thrombo-embolic disorders, cardio-respiratory disorders, metabolic and chronic inflammatory conditions, history of bleeding disorders, use of contraceptives and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, smokers, and alcoholics were excluded from the study and also Injury requiring hospitalization or an emergency room management or special nonorthodox treatment within 4 weeks; surgery within the previous 4 weeks; current infection with fever >38°C; active menstruation; strenuous exercise within 12 hours were also excluded. All participants were those screened negative for Human immune deficiency virus (HIV), Hepatitis B (HBsAg) and Hepatitis C from hospital records. | D-dimer, PT, Platelet counts, INR (international normalized ratio based on PT results), aPTT, AST, ALT | Other | Hitachi chemistry analyzer | No |

| Miri-Dashe 2014 [65] | Not reported | Nigeria | 383 | Adults (blood donors) and pregnant women (ANC clinic attendees) selected during a blood drive. | 18–65 | Excluded positive for HIV rapid test, HBsAg, HCV and Syphilis or donated / received blood transfusion in the previous month. "Healthy" not well defined beyond lab tests. | WBC, RBC, Hb, PCV, platelets, lymphocytes, neutrophils, eosinophil, basophils, MCV, MCH, MCHC, Na, K, Cl, HCO3, Urea, Creatinine, Glucose, AST, ALT, Total Bilirubin, Amylase, Total cholesterol, Triglycerides | Other | Sysmex KX-21N (Sysmex Corporation Kobe, Japan); Vitros 350 fully automated Chemistry Analyzer (Ortho-clinical Diagnostic) | No |

| Genetu 2017 [66] | 2015 | Ethiopia | 200 | Pregnant women attending an ANC clinic, limited description of recruitment | 18–42 | HIV negative, normal BMI (not defined), no other description of inclusion/ exclusion criteria | CD4+ T cells, Lymphocyte count, Total WBC count, Platelet count, RBC count, HB, Hematocrit, MCV, MCH, MCHC | Other | Cell-Dyn® 1800 (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL, USA); BD FACSCount™ system (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA). | Presented in the abstract and mentioned briefly in the discussion, the authors report that compared with the reference ranges derived from other studies, they found considerable variations in CD4+ T-cell count, HB, Hct, and MCV values. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were not presented visually and differences were not quantified. |

| Mulu 2017 [67] | 2015 | Ethiopia | 481 | Adults randomly selected for community based cross sectional survey | 18–65 | Age <18 years, adults with intestinal parasitic infections, hemo-parasites, skin rashes, history of blood transfusion < 6 months, HIV positive, HBsAg positive, HCV positive, pregnant, on any medication, exhibiting febrile symptoms, observable mental illness, disabled, smokers, chronic alcohol use, anemic, chronic diseases and acutely ill patients | WBC, RBC, Platelet, Lymphocyte, Neutrophil, Basophil, Eosinophil, Monocytes, HB, Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, CD4+ T cells | Other | Hematology analyzer MindrayBC320 (Mindray Biomedical electronic Corporation, China); FACS count (Becton Dickinson). | No |

| Siraj 2018 [68] | 2015 | Eritrea | 591 | Adult college students, laboratory staff members, ACHS staff members, factory workers and school teachers | 18–49 | Physical examination and CLSI inclusion and exclusion criteria. The exclusion criteria included: the presence of any disease including: anemia, cardio-vascular disease and high blood pressure. Additional exclusion criteria included: drug therapy, alcohol consumption; heavy smokers, chronic diseases such as diabetic mellitus (DM); individuals who had donated blood in the last 3 months. Individuals who had undergone surgery in the recent past were also excluded Questionnaire provided, mentions pregnancy, menstruation, breast feeding (but no mention in paper of exclusion on these factors). Serological tests for hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) were undertaken. HIV is not reported. | RBC count, Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW, WBC count, (lymphocytes, granulocytes, monocytes), platelet count | CLSI | AU 480 Chemistry System (Beckman Coulter) | The study RIs were compared to values currently in use by the Eritrean ministry of health (based on Beckman Coulter: AU 480 Chemistry System reagents inserts), and RIs from Tanzania, Ghana and elsewhere in Ethiopia. Overall, the proportion of OOR RIs ranged from 3.5 to 46.7%. In order of decreasing magnitude, the proportion of participants who were OOR included MCV (46.7%); MCH (37.9%) and Hb (36.2%). The lowest OOR proportions were observed in RBC (3.5%); platelet count (5.4%), Hct (11.1%), RDW (11.2%), total WBC count (12.5%) and MCHC (14.9%) respectively. This study had higher RBC RI compared to the study conducted in Ghana. However, the upper limit of the combined RBC RI in the Tanzanian study was comparatively higher. Further, the RI for Hgb (12.6–17.7 g/dL) and Hct (38.3–54.4%) were higher than those obtained from Tanzania and Ghana. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a table. |

| Alemu, 2019 [69] | 2015 | Ethiopia | 278 | Pregnant and age-matched, non pregnant women. The former were selected with systematic random sampling technique among ANC clinic attendees, the latter among ANC visitors and staff | Mean age 26, no range given | Apparently healthy; No previous history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and severe anemia, other chronic diseases, and taking medications that affect hematological indices for any reason were excluded. In addition, study participants who were smokers and chewers of chat were also excluded from the study. No laboratory screening tests reported. | WBC, Lymphocytes, Mixed cells, Neutrophils, Hb, Hct, RBC, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW, Platelet, PDW, MPV | Other | Sysmex KX-21N (Kobe, Japan) hematology analyzer | No |

| Omuse 2018 [70] | 2015 | Kenya | 528 | Adults recruited from urban colleges, universities, churches, hospitals, corporations and shopping malls. (same population as Omuse 2020) | 18–65 | Exclusion criteria included individuals with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 35 kg/m2, consumption of ethanol greater than or equal to 70 g per day [equivalent to 5 alcoholic drinks], smoking more than 20 tobacco cigarettes per day, taking regular medication for a chronic disease (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, allergic disorders, depression), recent (less than 15 days) recovery from acute illness, injury or surgery requiring hospitalization, known carrier state of Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C or HIV, pregnant or within 1 year after childbirth | RBC, Hb, Hct, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW, WBC, platelet, leukocyte differential counts of neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte, eosinophil, basophil | C-RIDL | Beckman Coulter ACT 5 DIFF CP analyser | The authors employed C-RIDL methods including larger sample size to facilitate comparisons with other studies. The present their data visually compared to 10 studies from eastern and southern Africa (Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, and Zambia), Kenya (2 additional studies), Uganda, Ethiopia, Tanzania, Rwanda, Ghana, Togo, and South Africa. Their study highlights marked differences in certain CBC parameters such as Hb, eosinophil and platelet counts compared to other SSA countries. The authors also compare their neutrophil data to US RIs and note lower neutrophil counts compared to the US. No statistical testing was reported. Comparisons were reported in a Figure (neutrophil RIs are also specified in the discussion), differences were not quantified. |