Abstract

Background

Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV) is a major monopartite virus in the family Geminiviridae and has caused severe yield losses in tomato and tobacco planting areas worldwide. Wall-associated kinases (WAKs) and WAK-like kinases (WAKLs) are a subfamily of the receptor-like kinase family implicated in cell wall signaling and transmitting extracellular signals to the cytoplasm, thereby regulating plant growth and development and resistance to abiotic and biotic stresses. Recently, many studies on WAK/WAKL family genes have been performed in various plants under different stresses; however, identification and functional survey of the WAK/WAKL gene family of Nicotiana benthamiana have not yet been performed, even though its genome has been sequenced for several years. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to identify the WAK/WAKL gene family in N. benthamiana and explore their possible functions in response to TYLCV infection.

Results

Thirty-eight putative WAK/WAKL genes were identified and named according to their locations in N. benthamiana. Phylogenetic analysis showed that NbWAK/WAKLs are clustered into five groups. The protein motifs and gene structure compositions of NbWAK/WAKLs appear to be highly conserved among the phylogenetic groups. Numerous cis-acting elements involved in phytohormone and/or stress responses were detected in the promoter regions of NbWAK/WAKLs. Moreover, gene expression analysis revealed that most of the NbWAK/WAKLs are expressed in at least one of the examined tissues, suggesting their possible roles in regulating the growth and development of plants. Virus-induced gene silencing and quantitative PCR analyses demonstrated that NbWAK/WAKLs are implicated in regulating the response of N. benthamiana to TYLCV, ten of which were dramatically upregulated in locally or systemically infected leaves of N. benthamiana following TYLCV infection.

Conclusions

Our study lays an essential base for the further exploration of the potential functions of NbWAK/WAKLs in plant growth and development and response to viral infections in N. benthamiana.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12870-023-04112-2.

Keywords: Nicotiana benthamiana, WAK/WAKL gene family, Phylogenetics, TYLCV infection, Expression profile, Stress response

Background

The Geminiviridae are a large family of plant viruses with circular single-stranded DNA genomes that can infect cash and food crops, resulting in substantial economic losses worldwide [1, 2]. Geminiviruses are currently classified into 14 genera according to their host range, transmission vector, and genome organization, including Becurtovirus, Begomovirus, Capulavirus, Citlodavirus, Curtovirus, Eragrovirus, Grablovirus, Maldovirus, Mastrevirus, Mulcrilevirus, Opunvirus, Topilevirus, Topocuvirus, and Turncurtovirus [3]. Plants infected with geminiviruses frequently exhibit various symptoms, including leaf curl, chlorosis, shoot twisting, stunting, fruit distortion, and plant death, ultimately leading to huge yield losses [4, 5]. Over the past few decades, geminiviruses have spread rapidly around the world due to the high rates of replication, mutation, and recombination in their genomes [6–8]. Every year, the economic losses caused by emerging geminiviruses are estimated to be several hundred million dollars, especially in Africa and Asia [4, 9]. Therefore, geminiviruses have been recognized as a serious threat to global agriculture and food security.

Tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV), a monopartite begomovirus in the family Geminiviridae, has spread worldwide [10]. This virus is a major global virus that causes a severe yellow leaf curl disease and is responsible for significant yield losses in tomato and tobacco planting areas [10, 11]. Recent studies showed that the genome of TYLCV contains eight open reading frames, namely, V1, V2, V3, C1, C2, C3, C4, and C5 [12–14]. TYLCV V3 is an endoplasmic reticulum- and Golgi-localized protein that suppresses host RNA silencing and trafficking of virions between cells in host plants [12, 13]. TYLCV AC5 is a symptom determinant and viral suppressor of RNA silencing, which can inhibit transcriptional gene silencing (TGS) and post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) and increase the pathogenicity of TYLCV to enhance the success of viral infection [14]. TYLCV V2 is a multifunctional protein that has been shown to interact with the host suppressor of gene silencing 3 to inhibit the PTGS [15] and with histone deacetylase 6 and argonaute 4 to inhibit methylation-mediated TGS in plants [16, 17]. Recently, TYLCV V2 was also reported to be involved in the nuclear export of V1, which is critical for the viral spread and systemic infection of TYLCV [18]. Finally, TYLCV C4 is a double-localized protein that interacts with a broad range of plant receptor-like kinases (RLKs) to prevent the cell-to-cell spread of RNA silencing [19, 20]. Additionally, overexpression of TYLCV C4 in Arabidopsis confers drought tolerance via an abscisic acid (ABA)-independent mechanism [21], and transgenic expression of TYLCV C4 in tomatoes leads to an alteration in the expression of plant developmental genes responsible for leaf upward cupping phenotype [22]. Therefore, it seems that each of the TYLCV-encoded proteins plays a critical role in its pathogenicity, and much research is still needed to understand the pathogenic mechanism of TYLCV.

When plants face abiotic and biotic stress conditions, they can sense and transmit external stimulus signals intracellularly through a wide range of receptors and produce various adaptive responses to environmental stimuli [23, 24]. RLKs are a large family that transmits signals from the outside to the inside of the cell via their intracellular kinase domains [25, 26]. Wall-associated kinases (WAKs) are a subfamily of the RLK family that contains a transmembrane proprotein, a cytoplasmic serine/threonine kinase domain, and an epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like structural domain [26, 27]. Furthermore, WAK-like kinases (WAKLs) are a type of RLKs with a structure similar to that of WAKs in plants [28, 29]. WAKs and WAKLs (WAK/WAKLs) form an essential class of RLKs implicated in cell wall signal sensing and transmitting extracellular signals to the cytoplasm, thereby regulating plant growth and development and stress responses [30–32]. For example, in Gossypium hirsutum, WAK/WAKL genes are reported to be involved in cotton fiber growth by regulating auxin and gibberellin levels [33]. In Arabidopsis, AtWAKL10 negatively regulates leaf senescence, and overexpression of AtWAKL10 causes transcriptional alterations of a specific set of genes involved in cell extension and cell wall modification [34]. Furthermore, in Arabidopsis and rice beans, WAK1s are implicated in response to aluminum toxicity, and overexpression of AtWAK1 can enhance plant tolerance to aluminum stress [35, 36]. In rice, OsWAK11 is characterized to detoxify excessive copper, and the knockdown of OsWAK11 results in hypersensitivity to copper toxicity [37].

In addition to the involvement in plant growth and development and responses to abiotic stresses, WAK/WAKL genes also play critical roles in plant responses to pathogen attacks [38, 39]. Recently, WAK/WAKL genes have been identified to prevent fungal and bacterial diseases in several crop species. For example, Xa4 encodes a WAK XA4 in rice and confers durable resistance to Xanthomonas oryzae by strengthening the cell wall [40]. In wheat, Stb6 encodes a conserved WAKL protein that manages gene-for-gene resistance against Zymoseptoria tritici in a hypersensitive response-independent manner [41]. Furthermore, TaWAK2 has been reported to prevent penetration and spread of Fusarium graminearum by suppressing the expression of pectin methyl esterase 1 to produce a more rigid cell wall [42]. In maize, it has also been shown that qHSR1 and Htn1, which encode two WAK/WAKL proteins, are implicated in plant resistance against fungal pathogens Sporisorium reilianum and Exserohilum turcicum, respectively [43, 44]. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that SlWAK1 interacts with Fls2/Fls3 to include the deposition of callose in tomatoes and minimizes the pathogen infection with Pseudomonas syringae [45]. More recently, a specific set of GhWAKLs has been reported to be induced by Verticillium dahliae infection, and the knockdown of GhWAKL expression suppresses jasmonic acid (JA)- and salicylic acid (SA)-mediated defense responses, impairing the resistance of cotton to Verticillium dahliae [46, 47]. These pleiotropic effects on pathogen infections frequently provide additional economic and agronomic benefits for crops that possess these WAK/WAKL genes. However, whether WAK/WAKLs are implicated in plant defense against viral infections remains unclear.

In this study, the WAK/WAKL gene family in Nicotiana benthamiana was identified at a genome-wide level using the bioinformatics method, and their potential roles in response to TYLCV infection were investigated using a virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) approach. We identified 38 WAK/WAKL family members in the N. benthamiana genome and found that 15 WAK/WAKLs are differentially expressed following TYLCV infection. Further VIGS analysis showed that disrupting the expression of WAK/WAKLs in N. benthamiana increases host susceptibility to TYLCV. Our results provide new evidence that N. benthamiana WAK/WAKLs (NbWAK/WAKLs) contribute to plant resistance to TYLCV infection. The study lays an essential base for further research on the potential functions of NbWAK/WAKLs in plant growth and development and response to viral infections in N. benthamiana. In the present study, we aimed to provide a comprehensive view of the NbWAK/WAKL gene family in N. benthamiana and to identify members involved in response to TYLCV infection.

Results

Identification of the WAK/WAKL gene family in N. benthamiana

In this study, a hidden Markov model (HMM) was constructed using WAK/WAKL protein sequences from Arabidopsis and tomato (Additional file 1) to identify the WAK/WAKL gene family N. benthamiana. As a result, 15 putative NbWAK genes and 23 putative NbWAKL genes were identified in N. benthamiana and designated as NbWAK1–NbWAK15 and NbWAKL1–NbWAKL23, respectively, according to their locations in the genome (Table 1). The genomic DNA of the identified NbWAK/WAKLs ranged from 1305 to 13,178 bp. The amino acid residue numbers of the putative NbWAK and NbWAKL proteins varied from 202 to 1159, and their isoelectric point (pI) and molecular weight (MW) ranged from 4.9–9.4 and 22.3–128.2 kDa, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Structural and biochemical features of the WAK/WAKL gene family in N. benthamiana

| Name | Gene IDa | Gene position | Strand | Size | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic DNA (bp) | mRNA (bp) | CDSb (bp) | 5′-UTRc (bp) | 5′-UTRd (bp) | Protein (aa) | pIe | MWf (kDa) | ||||

| NbWAK1 | Niben101Scf00149g10001 | Niben101Scf00149: 1014401..1025094 | forward | 10,694 | 2912 | 2811 | 101 | 0 | 936 | 8.0 | 103.7 |

| NbWAK2 | Niben101Scf00149g10003 | Niben101Scf00149: 1039140..1052317 | reverse | 13,178 | 1707 | 1707 | 0 | 0 | 568 | 6.7 | 62.0 |

| NbWAK3 | Niben101Scf00530g11020 | Niben101Scf00530: 1143477..1146128 | reverse | 2652 | 2075 | 1917 | 42 | 116 | 638 | 7.2 | 72.2 |

| NbWAK4 | Niben101Scf01237g11009 | Niben101Scf01237: 1118347..1122027 | forward | 3681 | 2205 | 2205 | 0 | 0 | 734 | 6.0 | 81.6 |

| NbWAK5 | Niben101Scf02160g02006 | Niben101Scf02160: 217154..220237 | reverse | 3084 | 2707 | 1905 | 291 | 511 | 634 | 6.4 | 71.4 |

| NbWAK6 | Niben101Scf02608g01007 | Niben101Scf02608: 112748..119830 | forward | 7083 | 2385 | 2115 | 270 | 0 | 704 | 6.8 | 77.6 |

| NbWAK7 | Niben101Scf02608g01008 | Niben101Scf02608: 148832..157171 | forward | 8340 | 3204 | 2115 | 270 | 819 | 704 | 6.6 | 77.6 |

| NbWAK8 | Niben101Scf03202g03004 | Niben101Scf03202: 362629..366940 | forward | 4312 | 2247 | 2247 | 0 | 0 | 748 | 6.1 | 82.6 |

| NbWAK9 | Niben101Scf03202g04015 | Niben101Scf03202: 391694..396324 | forward | 4631 | 2202 | 2202 | 0 | 0 | 733 | 7.7 | 79.9 |

| NbWAK10 | Niben101Scf03202g04017 | Niben101Scf03202: 397065..401394 | reverse | 4330 | 2157 | 2157 | 0 | 0 | 718 | 6.4 | 79.7 |

| NbWAK11 | Niben101Scf03472g00005 | Niben101Scf03472: 41760..50789 | reverse | 9030 | 1953 | 1953 | 0 | 0 | 650 | 8.5 | 72.9 |

| NbWAK12 | Niben101Scf06394g08019 | Niben101Scf06394: 877593..890273 | forward | 12,681 | 3083 | 2868 | 215 | 0 | 955 | 6.0 | 105.4 |

| NbWAK13 | Niben101Scf10330g02004 | Niben101Scf10330: 231600..234369 | reverse | 2770 | 2206 | 1893 | 107 | 206 | 630 | 5.7 | 68.3 |

| NbWAK14 | Niben101Scf13018g00012 | Niben101Scf13018: 12405..25275 | reverse | 12,871 | 3699 | 3480 | 219 | 0 | 1159 | 5.9 | 128.2 |

| NbWAK15 | Niben101Scf21196g00008 | Niben101Scf21196: 20786..24874 | forward | 4089 | 1854 | 1854 | 0 | 0 | 617 | 8.3 | 69.0 |

| NbWAKL1 | Niben101Scf00149g10020 | Niben101Scf00149:1031476..1037918 | forward | 6443 | 3469 | 1203 | 88 | 2178 | 400 | 5.1 | 42.9 |

| NbWAKL2 | Niben101Scf00327g01037 | Niben101Scf00327:124864..127845 | reverse | 2982 | 2291 | 1941 | 122 | 228 | 646 | 8.5 | 72.5 |

| NbWAKL3 | Niben101Scf00530g11014 | Niben101Scf00530:1137409..1142320 | reverse | 4912 | 3686 | 1509 | 1733 | 444 | 502 | 5.9 | 57.0 |

| NbWAKL4 | Niben101Scf00700g06021 | Niben101Scf00700:668335..673932 | reverse | 5598 | 2661 | 2661 | 0 | 0 | 886 | 6.2 | 98.8 |

| NbWAKL5 | Niben101Scf01521g06001 | Niben101Scf01521:684767..686339 | reverse | 1573 | 1476 | 915 | 194 | 367 | 304 | 4.9 | 33.6 |

| NbWAKL6 | Niben101Scf02290g02006 | Niben101Scf02290:197165..201565 | forward | 4401 | 2052 | 1908 | 133 | 11 | 635 | 8.4 | 71.1 |

| NbWAKL7 | Niben101Scf02381g08016 | Niben101Scf02381:792605..794693 | reverse | 2089 | 1023 | 1023 | 0 | 0 | 340 | 6.1 | 38.1 |

| NbWAKL8 | Niben101Scf03202g03002 | Niben101Scf03202:301027..307217 | forward | 6191 | 1011 | 1011 | 0 | 0 | 336 | 9.4 | 37.7 |

| NbWAKL9 | Niben101Scf03304g01026 | Niben101Scf03304:167027..172041 | reverse | 5015 | 2064 | 2064 | 0 | 0 | 687 | 6.2 | 76.2 |

| NbWAKL10 | Niben101Scf03363g01019 | Niben101Scf03363:210073..212041 | reverse | 1969 | 1807 | 1029 | 90 | 688 | 342 | 8.3 | 39.0 |

| NbWAKL11 | Niben101Scf03445g00009 | Niben101Scf03445:15851..17440 | forward | 1590 | 1176 | 843 | 333 | 0 | 280 | 5.5 | 30.5 |

| NbWAKL12 | Niben101Scf03939g06023 | Niben101Scf03939:737517..742076 | forward | 4560 | 1395 | 1128 | 0 | 267 | 375 | 6.1 | 41.5 |

| NbWAKL13 | Niben101Scf04445g01002 | Niben101Scf04445:135918..147686 | reverse | 11,769 | 2886 | 2886 | 0 | 0 | 961 | 8.5 | 107.5 |

| NbWAKL14 | Niben101Scf05368g07009 | Niben101Scf05368:738506..740861 | reverse | 2356 | 1865 | 1584 | 0 | 281 | 527 | 6.3 | 59.0 |

| NbWAKL15 | Niben101Scf06394g08020 | Niben101Scf06394:862041..863966 | forward | 1926 | 789 | 789 | 0 | 0 | 262 | 5.1 | 27.8 |

| NbWAKL16 | Niben101Scf06909g04005 | Niben101Scf06909:411031..419054 | reverse | 8024 | 1899 | 1899 | 0 | 0 | 632 | 5.1 | 71.1 |

| NbWAKL17 | Niben101Scf07969g00010 | Niben101Scf07969:42176..44432 | forward | 2257 | 1066 | 888 | 178 | 0 | 295 | 5.3 | 32.5 |

| NbWAKL18 | Niben101Scf11389g01034 | Niben101Scf11389:144908..147896 | forward | 2989 | 1529 | 951 | 197 | 381 | 316 | 4.9 | 34.9 |

| NbWAKL19 | Niben101Scf11416g00017 | Niben101Scf11416:76861..79712 | reverse | 2852 | 1899 | 1899 | 0 | 0 | 632 | 5.9 | 70.2 |

| NbWAKL20 | Niben101Scf14950g00001 | Niben101Scf14950:25106..26461 | reverse | 1356 | 1040 | 864 | 176 | 0 | 287 | 5.3 | 31.4 |

| NbWAKL21 | Niben101Scf20037g00022 | Niben101Scf20037:58700..62033 | reverse | 3334 | 2613 | 2103 | 168 | 342 | 700 | 7.9 | 77.1 |

| NbWAKL22 | Niben101Scf21589g00004 | Niben101Scf21589:55217..57416 | reverse | 2200 | 1074 | 858 | 216 | 0 | 285 | 6.1 | 31.1 |

| NbWAKL23 | Niben101Ctg15342g00002 | Niben101Ctg15342:201..1505 | forward | 1305 | 862 | 609 | 253 | 0 | 202 | 5.3 | 22.3 |

a Gene ID, the gene locus in the Sol Genomics Network (https://solgenomics.net/). b CDS coding sequence. c 5′-UTR 5′-untranslated region. d 3′-UTR 3′-untranslated region. e pI, isoelectric point. f MW, molecular weight

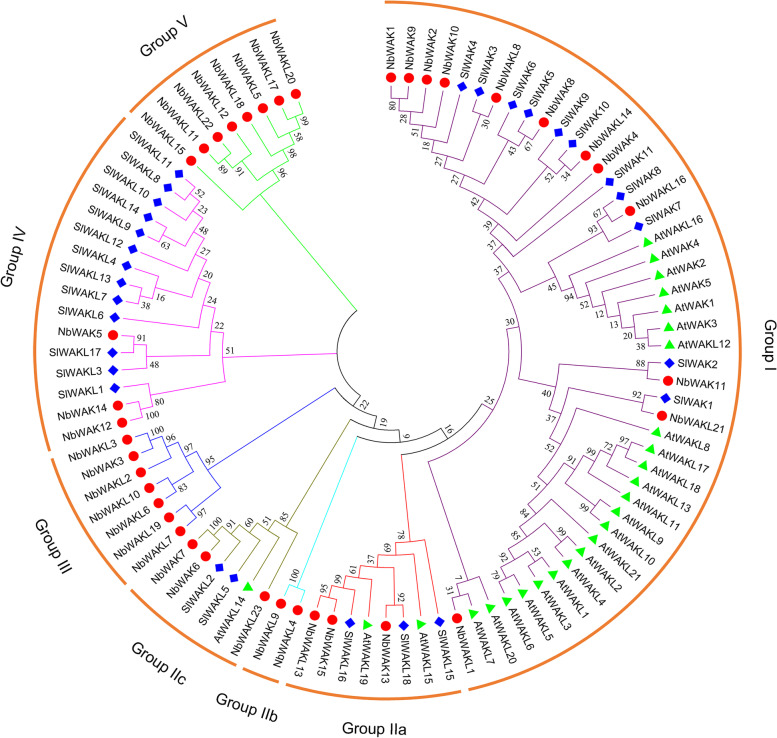

Phylogenetic analysis of NbWAK/WAKL proteins

To determine the evolutionary relationships between the members in the NbWAK/WAKL gene family and further infer their putative functions based on homologous genes in other plants, we constructed a phylogenetic tree using 38 NbWAK/WAKLs together with 26 AtWAK/WAKLs [28] and 29 SlWAK/WAKLs [48]. As shown in Fig. 1, these 93 WAK/WAKL proteins were divided into five clusters (Groups I–V), and Group II was further classified into three subgroups (Groups IIa, IIb, and IIc). Group I consisted of 23 AtWAK/WAKL members, 12 NbWAK/WAKL members, and 11 SlWAK/WAKL members. Group II, the largest subgroup, comprised eight NbWAK/WAKL members, five SlWAK/WAKL members, and three AtWAK/WAKL members. Group III contained only seven members, NbWAK3 and NbWAKLs 2, 3, 6, 7, 10, and 19, and so was the smallest subgroup. Group IV possessed 13 NbWAK/WAKL and three SlWAK/WAKL members. Like Group III, Group V included eight members of NbWAK/WAKLs. Notably, Groups III and V were subgroups specific to N. benthamiana (Fig. 1). These results indicate that N. benthamiana has evolved many WAK/WAKLs during long-term acclimation.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic analysis of wall-associated kinase (WAK) and WAK-like (WAKL) proteins from Nicotiana benthamiana, Arabidopsis, and tomato. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum-likelihood (ML) method with 1000 bootstrap replicates for each branch through MEGA 11.0. WAKs and WAKLs from different plant species are labeled with different colors. Purple, red, turquoise, green-brown, blue, pink, and green clusters represent Groups I, IIa, IIb, IIc, III, IV, and V, respectively

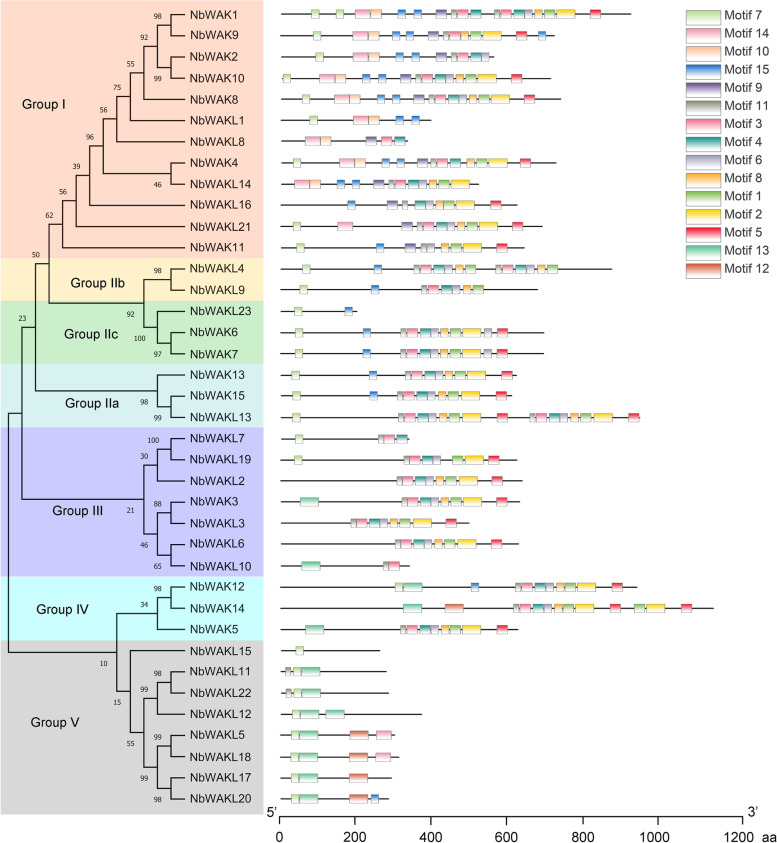

Conserved motif analysis of NbWAK/WAKL Proteins

To fully understand the diverse functions of these NbWAK/WAKL proteins, their conserved motifs were analyzed using the Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation (MEME) suite (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme/) [49]. As shown in Fig. 2, a total of 15 conserved motifs (Motifs 1–15) were detected in the protein sequences of NbWAK/WAKLs. MEME analysis and the phylogenetic tree indicated that motif structures of NbWAK/WAKLs varied considerably between members of different phylogenetic groups, but they were similar between members of the same group (Fig. 2). Furthermore, some motifs were unique to certain phylogenetic groups. For example, Motifs 9 and 10 were present only in Group I, and Motifs 12 and 13 were mainly detected in Group V (Fig. 2), suggesting that these specific motifs might contribute to the functional divergence of NbWAK/WAKLs in different groups. In addition, most of the structurally similar NbWAK/WAKLs were found to possess the common motifs (Fig. 2), indicating similar functions and functional divergence of these family members over their evolutionary courses.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of molecular phylogenetic relationships and conserved motifs of WAK/WAKL proteins in Nicotiana benthamiana. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum-likelihood (ML) method with 1000 bootstrap replicates for each branch through MEGA 11.0. Conserved motifs were identified using the Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation (MEME) suite with the complete protein sequences of NbWAK/WAKLs and visualized using TBtools (v.1.098661). Different colored boxes indicate different motifs. Locations of different motifs are proportional to their sequence lengths

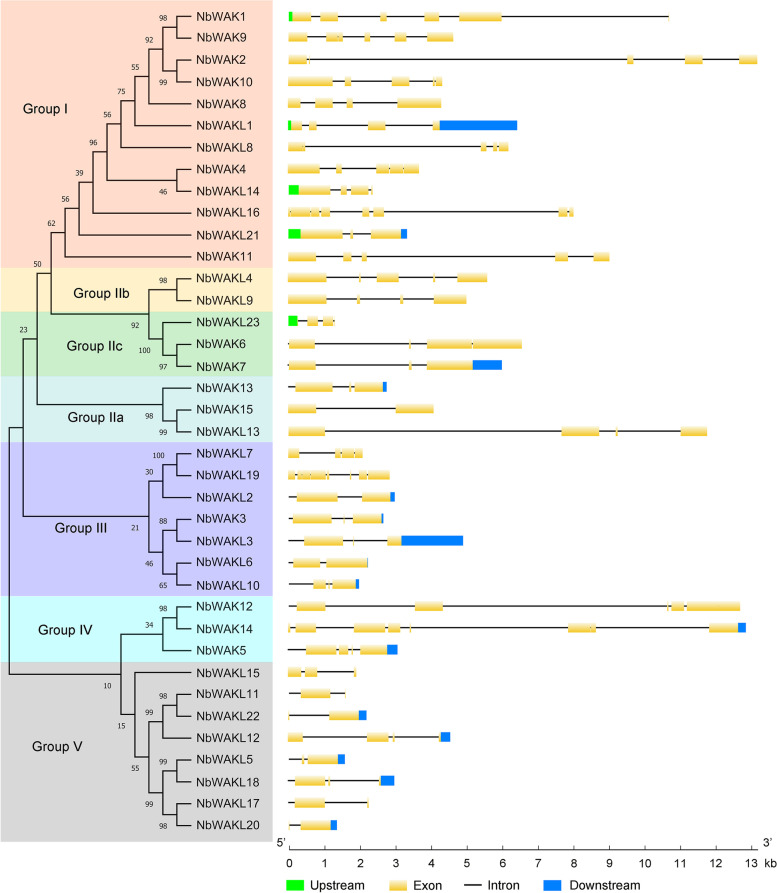

Gene structure analysis of NbWAK/WAKL genes

To obtain more information about the structural diversity of NbWAK/WAKL genes, we constructed a maximum-likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree and analyzed the exon–intron organization of NbWAK/WAKL genes using the Gene Structure Display Server 2.0 (GSDS 2.0) (http://gsds.gao-lab.org/) web portal [50]. As shown in Fig. 3, NbWAK/WAKLs had 2–8 exons, with the most exons (eight exons) found in NbWAK14, NbWAKL16, and NbWAKL19 and the least (two exons) in NbWAKL5, NbWAKL6, NbWAKL11, NbWAKL17, NbWAKL20, and NbWAKL22. Interestingly, most NbWAK/WAKLs in the same phylogenetic group had the same number of exons, such as NbWAK1, NbWAK2, NbWAK4, NbWAK10, NbWAK11, and NbWAKL8 in Group I and NbWAKL5, NbWAKL11, NbWAKL17, NbWAKL20, and NbWAKL22 in Group V (Fig. 3). These results suggest a similar diversity of expansion and evolution among members of the same phylogenetic group of NbWAK/WAKLs in N. benthamiana.

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of molecular phylogenetic relationships and gene structure of WAK/WAKLs in Nicotiana benthamiana. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Maximum-likelihood method with 1000 bootstrap replicates for each branch through MEGA 11.0. The diagrammatic genomic organization of NbWAK/WAKLs was produced using the Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS) 2.0. Upstream sequences, exons, introns, and downstream sequences are indicated by green boxes, yellow boxes, black lines, and blue boxes, respectively

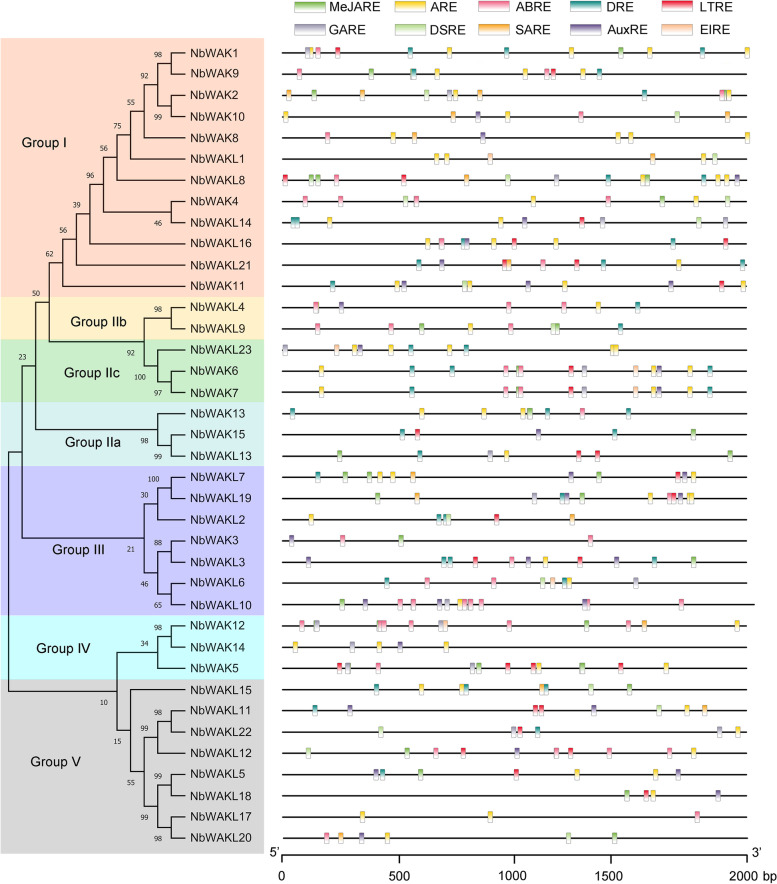

Promoter analysis of NbWAK/WAKL genes

To explore the potential function and regulatory model of these NbWAK/WAKL genes, the cis-acting elements in the 2000 bp promoter sequences of NbWAK/WAKLs were analyzed using the PlantCARE database [51]. As a result, several phytohormone and/or stress response-related cis-acting elements were identified: MeJA-responsive element (MeJARE), anaerobic response element (ARE), ABA-responsive element (ABRE), drought-responsive element (DRE), low-temperature-responsive element (LTRE), gibberellin-responsive element (GARE), defense- and stress-responsive element (DSRE), SA-responsive element (SARE), auxin-responsive element (AuxRE), and elicitor-responsive element (EIRE) (Fig. 4 and Additional file 2). Out of the 38 NbWAK/WAKLs, 36 had the ARE element, 25 possessed the DRE element, 24 contained the ABRE element, 23 harbored the MeJARE and GARE elements, 20 contained the LTRE element, 15 possessed the SARE and AuxRE elements, 13 had the DSRE element, and 6 harbored the EIRE element (Fig. 4 and Additional file 2). These results indicate a possible involvement of these genes in various phytohormone and/or stress responses.

Fig. 4.

Schematic representation of molecular phylogenetic relationships and 2000 bp promoters of WAK/WAKLs in Nicotiana benthamiana. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Maximum-likelihood method with 1000 bootstrap replicates for each branch through MEGA 11.0. The 2000 bp promoter sequences of NbWAK/WAKLs were analyzed using PlantCARE and visualized using TBtools (v.1.098661). Different colored boxes represent different cis-acting elements

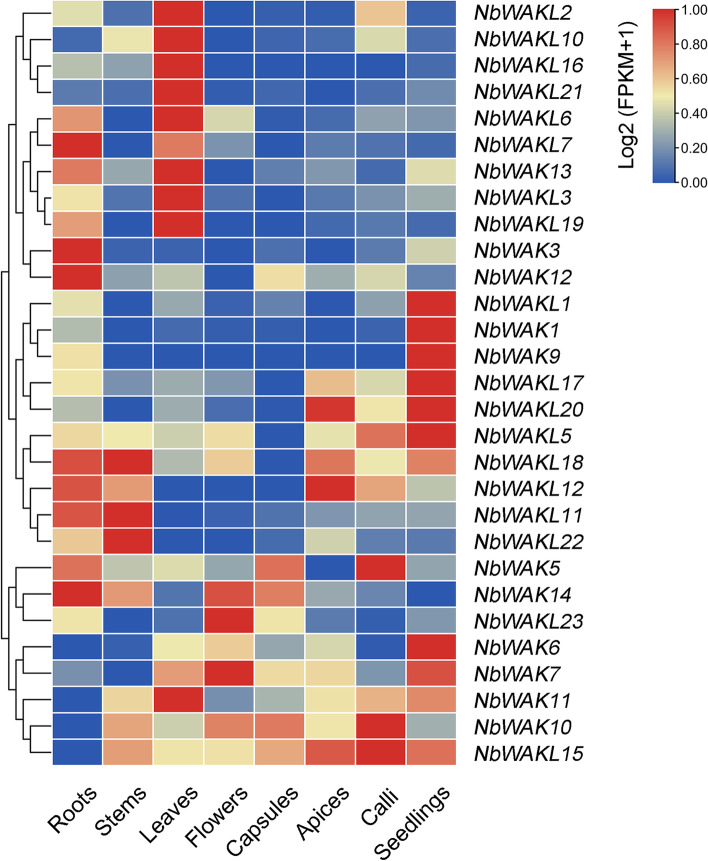

Tissue-specific expression patterns of NbWAK/WAKL genes

To further investigate the expression patterns of NbWAK/WAKLs in N. benthamiana, we analyzed their expression profiles in different tissues (roots, stems, leaves, flowers, capsules, apices, calli, and seedlings) using the public RNA-sequencing data [52]. Expression analysis indicated that 29 of the 38 NbWAK/WAKLs were expressed in at least one tissue (Fig. 5 and Additional file 3). Seven genes (NbWAK5–7, NbWAK10, and NbWAK12–14) were detected in all examined tissues with fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) values ≥1.0 (Fig. 5 and Additional file 3). There were 11 genes (NbWAK3, NbWAK5–7, NbWAK12–14, NbWAKL2, NbWAKL3, NbWAKL6, and NbWAKL11) and 7 genes (NbWAK6, NbWAK10, NbWAK11, NbWAK13, NbWAKL11, NbWAK14, and NbWAKL22) that were highly expressed in the roots and stems of N. benthamiana, respectively (FPKM ≥3.0) (Fig. 5 and Additional file 3). In addition, 12 genes (NbWAK6, NbWAK7, NbWAK10–13, NbWAKL2, NbWAKL3, NbWAKL6, NbWAKL10, NbWAKL19, and NbWAKL21) were highly expressed in the leaves of N. benthamiana (FPKM ≥3.0), with the two highest expression levels noted for NbWAK13 (FPKM ≥52.0) and NbWAKL6 (FPKM ≥42.0) (Fig. 5 and Additional file 3). In the flower tissue of N. benthamiana, seven genes (NbWAK6, NbWAK7, NbWAK10, NbWAK13, NbWAK14, NbWAKL6, and NbWAKL23) showed high expression levels (FPKM ≥3.0), with the two highest expression levels noted for NbWAK14 (FPKM ≥10.0) and NbWAK7 (FPKM ≥7.0) (Fig. 5 and Additional file 3). These data suggest that each NbWAK/WAKL gene has a tissue-specific expression pattern, and such expression patterns may be related to their functions in regulating plant growth and development and stress responses.

Fig. 5.

Expression profiles of NbWAK/WAKLs in different tissues of Nicotiana benthamiana. Transcriptomic data used for tissue expression were obtained from the NCBI sequence read archive (SRA) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/) under the accession number PRJNA188486 [52], and the expression level of each gene is colored based on their Log2 (FPKM+ 1) values calculated from eight tissues: roots, stems, leaves, flowers, capsules, apices, calli, and seedlings. The heatmap was generated using TBtools (v.1.098661)

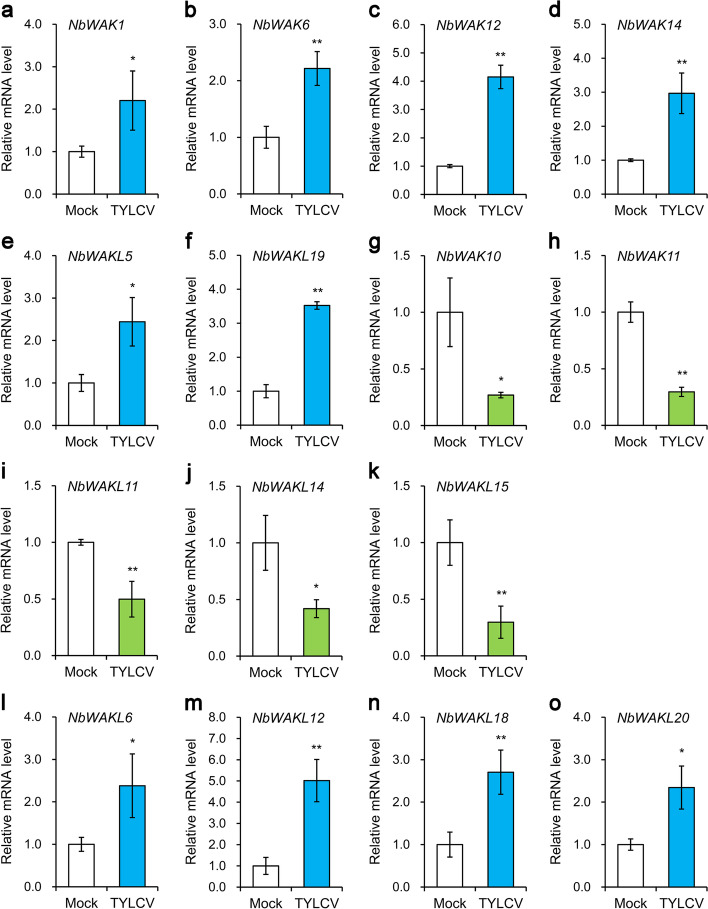

Expression profiles of NbWAK/WAKL genes following TYLCV infection

To test whether NbWAK/WAKLs are involved in response to TYLCV infection, we examined the gene expression profiles of NbWAK/WAKLs in the leaves of N. benthamiana following TYLCV infection using expression data obtained from a previous study [53]. The results revealed that the expression of NbWAK1, NbWAK6, NbWAK12, NbWAK14, NbWAKL5, and NbWAKL19 was upregulated significantly in the locally infected leaves of N. benthamiana following TYLCV infection (Fig. 6a–f). Furthermore, the expression of NbWAK10, NbWAK11, NbWAKL11, NbWAKL14, and NbWAKL15 was downregulated dramatically in the locally infected leaves of N. benthamiana upon TYLCV infection (Fig. 6g–k). In contrast, the expression of NbWAKL6, NbWAKL12, NbWAKL18, and NbWAKL20 was upregulated considerably in systemically infected leaves of N. benthamiana following TYLCV infection (Fig. 6l–o), and none of the NbWAK/WAKLs showed decreased expression levels in the systemic leaves of N. benthamiana in response to TYLCV. Interestingly, each of the upregulated NbWAK/WAKLs was increased more than two-fold in both the locally and systemically infected leaves of N. benthamiana following TYLCV infection (Fig. 6), indicating a critical role for these NbWAK/WAKLs in the response to TYLCV infection.

Fig. 6.

Expression levels of NbWAKWAKLs in leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana following tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV) infection. a–k Relative expression of NbWAK1, NbWAK6, NbWAK12, NbWAK14, NbWAKL5, NbWAKL19, NbWAK10, NbWAK11, NbWAKL11, NbWAKL14, and NbWAKL15 in the locally infected leaves of N. benthamiana upon TYLCV infection. l–o Relative expression of NbWAKL6, NbWAKL12, NbWAKL18, and NbWAKL20 in the systemically infected leaves of N. benthamiana upon TYLCV infection. Data represent relative mRNA levels against the leaves infected with Agrobacterium tumefaciens containing an empty vector (Mock), values of which are set to 1.0 units. The data are given as means ± standard deviation of three biological replicates. Statistically significant differences are marked with asterisks: * P < 0.05 or ** P < 0.01; Student’s t-test

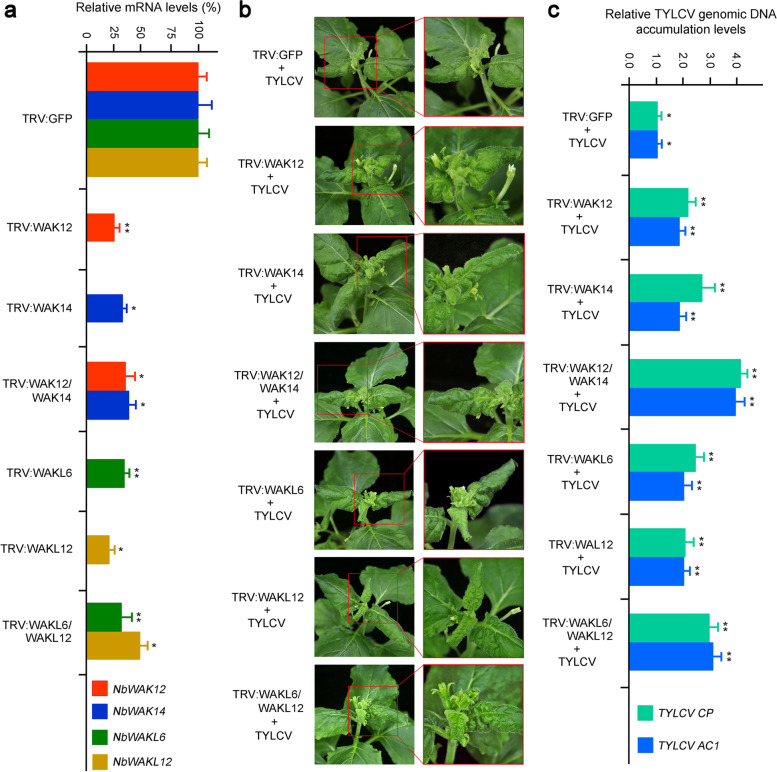

Disruption of the expression of NbWAK/WAKL genes increases host susceptibility to TYLCV

To further investigate the potential function of NbWAK/WAKLs in response to TYLCV infection, we examined their precise role in responding to TYLCV during viral infection using the VIGS technology [54]. Based on the tissue-specific expression patterns and gene expression profiles of NbWAK/NbWAKLs following TYLCV infection (Figs. 5 and 6), four genes, which included two NbWAK genes (NbWAK12 and NbWAK14) and two NbWAKL genes (NbWAKL6 and NbWAKL12), were selected and silenced individually or in combination with each other by TRV-based VIGS system. Compared with the vector control (N. benthamiana seedlings agroinfiltrated with TRV:GFP), the mRNA levels of NbWAK12, NbWAK14, NbWAKL6, and NbWAKL12 in seedlings agroinfiltrated with the silencing vectors were decreased by approximately 40–80% at ten days post-infiltration (dpi) (Fig. 7a), suggesting that VIGS successfully silenced the target genes. Subsequently, the control and silenced seedlings were agroinfiltrated with the infectious clone of TYLCV and monitored for symptom development over time. At 21 dpi, compared with the vector control, severe leaf curling and crinkling symptoms caused by TYLCV were observed in systemic leaves of seedlings in which NbWAK/NbWAKLs were silenced by VIGS, especially in seedlings in which the two components of NbWAK/WAKLs were silenced (Fig. 7b). These results indicated that N. benthamiana seedlings were more susceptible to TYLCV when the NbWAK/WAKL genes were suppressed. For further confirmation, we determined the TYLCV genomic DNA accumulation by calculating the expression levels of TYLCV CP and AC1 using quantitative PCR (qPCR), as established previously [55, 56]. Notably, N. benthamiana seedlings with individual or double silencing of NbWAK/NbWAKLs accumulated more viral genomic DNA than the control plants (Fig. 7c). Altogether, these results suggest that silencing of the components of NbWAK/WAKLs impairs the resistance of N. benthamiana to TYLCV and increases the accumulation of TYLCV genomic DNA in the host plants.

Fig. 7.

Silencing of the NbWAK/WAKLs in Nicotiana benthamiana makes it susceptible to infection with tomato yellow leaf curl virus (TYLCV). a Silencing efficiency was assessed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) at ten days post-inoculation (dpi). The values represent relative mRNA levels against those of the control groups (N. benthamiana seedlings agroinfiltrated with TRV:GFP), values of which are set to 100%. b Disease symptoms caused by TYLCV in the NbWAK/WAKLs silenced N. benthamiana seedlings at 21 dpi. TRV:GFP-agroinfiltrated N. benthamiana seedlings infected with TYLCV were used as the control. c Relative accumulation of TYLCV genomic DNA in the NbWAK/WAKLs silenced N. benthamiana seedlings. Viral accumulation was measured by qPCR at 21 dpi, as shown in Fig. 7a. The values represent relative viral DNA accumulation levels against those of the control groups (TRV:GFP-agroinfiltrated N. benthamiana seedlings infected with TYLCV), values of which are set to 1.0 units. For a and c, the data are given as means ± standard deviation of three biological replicates. Significant differences in expression are marked with asterisks: * P < 0.05 or ** P < 0.01; Student’s t-test

Discussion

The WAK/WAKL gene family is a subset of RLKs that has critical roles in plant growth and development and resistance to abiotic and biotic stresses [30, 38, 39]. Here, we identified and characterized the WAK/WAKL gene family in N. benthamiana. This WAK/WAKL gene family consists of 38 NbWAK/WAKL members, which is more than that observed in tomato [48], Arabidopsis [28], cotton [33], potato [57], and common walnut [58] and less than that found in rice [59], Populus [60], apple [61], Chinese cabbage [62], barley [63], and rose [64]. Based on the amino acid sequences and phylogenetic relationships with the WAK/WAKL proteins in Arabidopsis and tomato, the 38 NbWAK/WAKLs were divided into five groups (Fig. 1). This result is consistent with the findings of previous studies on WAK/WAKLs from other plant species [31, 58, 63, 64]. Interestingly, Groups I and II were composed of WAK/WAKL genes from different plant species, including N. benthamiana, Arabidopsis, and tomato, whereas Groups III, IV, and V consisted of WAK/WAKL genes from N. benthamiana and tomato, suggesting that these WAK/WAKL genes of N. benthamiana and tomato may have evolved independently after the formation of the WAK/WAKL genes of Arabidopsis. This finding corroborates previous studies in which a specific set of WAK/WAKL genes in cotton had evolved independently [31, 65]. In addition, this classification of NbWAK/WAKLs was also supported by the conserved motif and gene structure analyses, showing that each phylogenetic group shares similar motifs and exon–intron structures (Figs. 2 and 3).

Previous studies have demonstrated that exon–intron structures frequently affect the evolution of a gene family [31, 66, 67]. In this study, gene structure analysis showed that different exon–intron structure patterns exist in different phylogenetic groups of NbWAK/WAKLs. The average number of exons of NbWAK/WAKLs was five in Group I, four in Groups II and IV, three in Group III, and two in Group V, respectively (Fig. 3). This finding aligns with the exon–intron structure of WAK/WAKL genes from Populus [60], tomato [48], and cotton [33], which is the result of the continuous evolution of the WAK/WAKL gene family. Furthermore, to obtain additional information about the regulation of NbWAK/WAKLs, we explored the cis-acting elements in their 2000 bp promoter sequences. Ten types of phytohormone and/or stress response-related cis-acting elements were identified, namely, MeJARE, ARE, ABRE, DRE, LTRE, GARE, DSRE, SARE, AuxRE, and EIRE (Fig. 4). This wide range of cis-acting elements is in line with the observations in previous studies on the phytohormone- and/or stress-responsive functions of WAK/WAKL genes in plants [33, 47, 48]. MeJARE, ABRE, GARE, SARE, and AuxRE were identified to involve in plant responses to MeJA, ABA, GA, SA, and auxin, respectively. This result suggests that NbWAK/WAKLs can be regulated by multiple plant hormones and thereby play a regulatory role in stress responses [33, 58]. Moreover, we also identified some cis-acting elements associated with stress responses in the promoter regions of NbWAK/WAKLs, such as ARE, DRE, LTRE, DSRE, and EIRE, suggesting that NbWAK/WAKLs may play a critical role in plant responses to different stresses [48, 68].

In addition, gene expression patterns frequently provide crucial information regarding gene functions [69]. Therefore, expression levels of NbWAK/WAKLs in the roots, stems, leaves, flowers, capsules, apices, calli, and seedlings were determined using public RNA-sequencing data [52]. The results indicated that most of the NbWAK/WAKLs were expressed in at least one tissue (Fig. 5), suggesting they may have essential roles in plant growth and development in N. benthamiana. These results corroborate the findings of previous studies in which WAK/WAKLs were found to have housekeeping functions in plant growth and development [32, 33, 48, 58]. In addition, relatively high expression levels of some genes were detected in the specific tissues, such as NbWAK12, NbWAK13, NbWAK14, and NbWAKL6 in the roots, NbWAK13 in the stems, NbWAK11, NbWAK13, NbWAKL2, NbWAKL3, and NbWAKL6 in the leaves, and NbWAK14 in flowers (Fig. 5 and Additional file 3), suggesting their potential functional implications in these tissues.

TYLCV is an important virus that can cause a severe yellow leaf curl disease in tomatoes and tobacco worldwide [10, 11]. To investigate whether NbWAK/WAKLs are involved in the response of N. benthamiana to TYLCV, we analyzed the expression profiles of NbWAK/WAKLs in locally and systemically infected leaves of N. benthamiana following TYLCV infection. Here, there were six and four NbWAK/WAKLs in the locally and systemically infected leaves of N. benthamiana, respectively, which were upregulated upon TYLCV infection (Fig. 6). These genes were unevenly distributed across each phylogenetic group, in which eight NbWAK/WAKLs (NbWAK12, NbWAK14, NbWAKL5, NbWAKL6, NbWAKL12, and NbWAKL18–20) belonged to the Groups III, IV, and V (Fig. 1) that have evolved independently during long-term evolution. We speculated that these independently evolved NbWAKLs play a crucial role in defending against viral infections. Consequently, four genes, including two NbWAK genes (NbWAK12 and NbWAK14) and two NbWAKL genes (NbWAKL6 and NbWAKL12), were silenced and then functionally determined through their response to TYLCV infection. Furthermore, the VIGS and qPCR results revealed that the accumulation of TYLCV genomic DNA was significantly increased when NbWAK12, NbWAK14, NbWAKL6, and NbWAKL12 were silenced (Fig. 7), suggesting that these NbWAK/WAKLs play a critical role in the response to TYLCV infection. This result corroborates the results from previous studies in which a specific set of WAK/WAKL genes was shown to be strongly induced by pathogens in rice [40], cotton [46], and rose [64]. Although the precise functions of NbWAK/WAKLs in response to TYLCV infection are yet to be elucidated, our findings may help to clarify the expansion of the NbWAK/WAKL gene family and to characterize their function in resistance against TYLCV.

Conclusions

Here, we described the first integrated investigation of the WAK/WAKL gene family in N. benthamiana through gene identification and the analysis of conserved motifs, gene structures, promoters, and tissue and TYLCV response expression profiles. A total of 38 NbWAK/WAKLs were identified on a genome-wide scale, which can provide essential information to functionally characterize the WAK/WAKL gene family in N. benthamiana. In addition, our VIGS and qPCR data demonstrated that TYLCV genomic DNA accumulation significantly increased when the four NbWAK/WAKLs (NbWAK12, NbWAK14, NbWAKL6, and NbWAKL12) were silenced in N. benthamiana. These findings are helpful to explore further the WAK/WAKL gene-mediated molecular processes implicated in response to TYLCV infection and to provide a basis for systematically investigating the functional mechanisms of the WAK/WAKL gene family in N. benthamiana.

Methods

Identification of WAK/WAKL genes in N. benthamiana

Genome sequences of N. benthamiana were obtained from the Sol Genomics Network (https://solgenomics.net/organism/Nicotiana_benthamiana/genome/) [70]. Protein sequences of WAK and WAKL proteins in Arabidopsis and tomato were downloaded from the Arabidopsis Information Resource version 11 (Araport11) (https://www.arabidopsis.org/) and International Tomato Genome Sequencing Consortium version 4.0 (ITAG 4.0) (https://solgenomics.net/organism/Solanum_lycopersicum/genome/), respectively [28, 48]. The known WAK and WAKL protein sequences (Additional file 1) were utilized to construct the HMM profile that was used to query the N. benthamiana protein dataset using HMMER software (v.3.2.1) [71]. The identified WAK and WAKL proteins from N. benthamiana were further confirmed by the presence of GUB_WAK_bind (PF13947), EGF (PF00008), and Pkinase (PF00069) domains using the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/) [72]. Candidate proteins that contained intact GUB_WAK_bind, EGF, and Pkinase domains were identified as NbWAKs; those that included two of these three domains were identified as NbWAKLs; those that had only one of these three domains were removed. The candidates, NbWAK/WAKL genes, identified from N. benthamiana, were named according to their corresponding physical map locations. The pI and MW of NbWAK/WAKL proteins were analyzed using the Compute pI/Mw tool (https://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/).

Phylogenetic tree construction and protein motif analysis

The 38 NbWAK/WAKL protein sequences were used to establish evolutionary relationships with the known WAK/WAKL proteins from Arabidopsis and tomato (Additional file 1). Sequence alignment of these WAK/WAKL protein sequences was carried out using the MUSCLE program in MEGA 11.0 [73], and the phylogenetic tree was built with a ML method [74] based on the alignment through MEGA 11.0. Conserved motifs in NbWAK/WAKL protein sequences were analyzed using the MEME program (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme/) [49] with the following parameters: the maximum motif number was set to 15, and the optimal motif width was set between 6 and 60.

Gene structure and promoter analyses

Gene structure and promoter data for NbWAK/WAKLs were obtained from the Sol Genomics Network (https://solgenomics.net/organism/Nicotiana_benthamiana/genome/) [70]. Gene structure analysis was performed using the GSDS 2.0 (http://gsds.gao-lab.org/) [50]. Promoter analysis was performed by searching 2000 bp sequences upstream from the start codon of NbWAK/WAKLs against the PlantCARE database (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools /plantcare/html/) [51] to identify putative cis-elements as described by Zhao et al. [75]. The MeJARE, ARE, ABRE, DRE, LTRE, GARE, DSRE, SARE, AuxRE, and EIRE related to phytohormone and/or stress responses were further analyzed. The results of the promoter analysis were visualized using TBtools (v.1.098661) [76].

Tissue-specific and differential expression analyses

To determine the expression profiles of NbWAK/WAKLs in different tissues of N. benthamiana, a comparative analysis of published RNA-sequencing data, SRR696961, SRR696992, SRR696940, SRR696938, SRR696884, SRR685298, SRR697013, and SRR696988 [52], was carried out. Sequence assembly was conducted using the HISAT2 (v.2.1.0) [77], and the FPKM values were calculated using the StringTie2 (v.2.1.5) [78]. Different tissues in N. benthamiana, including the root, stem, leaf, flower, capsule, apex, calli, and seedling, were selected [52]. The results of the expression levels of NbWAK/WAKLs were visualized using TBtools (v.1.098661) [76]. For differential expression analysis of NbWAK/WAKLs in response to TYLCV, the gene expression data were obtained from a previous study [53] and re-analyzed using Microsoft Excel (v.2019, Microsoft Corp., USA), as described previously [69].

Plant materials and growth conditions

Wild-type N. benthamiana plants were utilized in this study, and they were grown in a greenhouse belonging to Dr. Zhanqi Wang (Huzhou University) at 25 ± 1 °C with a 16 h/8 h (light/dark) photoperiod as described by Zhong et al. [1]. N. benthamiana seedlings at the 4- to 6-leaf stage were used for the experiments.

VIGS and silencing efficiency assay

To silence the expression of NbWAK12, NbWAK14, NbWAKL12, and NbWAKL6 genes in N. benthamiana, a tobacco rattle virus (TRV)-based VIGS system [54] was used. Approximately 300 bp fragments of WAK/WAKL genes were cloned individually into the KpnI-BamHI sites of the pTRV2 vector to generate VIGS constructs as described previously [6, 79]. The resulting VIGS plasmids were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain EHA105 by electroporation, and Agrobacterium-mediated infiltration of N. benthamiana was carried out as described previously [6]. N. benthamiana seedlings agroinfiltrated with pTRV2:GFP and pTRV1 were used as the control. At ten dpi, the silencing efficiency of the VIGS was evaluated by qPCR analysis as described previously [1, 80]. The primers used for the VIGS constructs and qPCR are listed in Additional file 4.

TYLCV inoculation and viral DNA accumulation

The infectious clone of TYLCV was gifted by Prof. Yan Xie (Zhejiang University, China). Viral inoculation with TYLCV on N. benthamiana was performed as described previously [53]. At 21 dpi, the inoculated N. benthamiana seedlings were photographed, and the systemically infected leaves were sampled. The accumulation of TYLCV CP and AC1 was measured using the qPCR, and the N. benthamiana 25S nuclear rRNA gene (Nb25SrRNA) was used as endogenous control [1, 80]. The relative viral DNA accumulation levels were determined using a comparative threshold cycle (CT) method, and the data were from three independent biological replicates. The primers used for qPCR are listed in Additional file 4.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in three independent replicates, and the data were given as means ± standard deviation (SD). The statistical significance of differences was calculated using Student’s t-test, and a P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1. Protein sequences of WAK/WAKL of Nicotiana benthamiana, Arabidopsis, and tomato.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Cis-acting elements in the promoter regions of NbWAK/WAKL genes.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Tissue expression profiles of NbWAK/WAKL genes.

Additional file 4: Table S4. List of primers used in this study.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Yule Liu (Tsinghua University, China) for providing the tobacco rattle virus (TRV)-based VIGS vectors.

Abbreviations

- ABA

Abscisic acid

- ABRE

ABA-responsive element

- ARE

Anaerobic response element

- AuxRE

Auxin-responsive element

- dpi

Days post-infiltration

- DRE

Drought-responsive element

- DSRE

Defense- and stress-responsive element

- EGF

Epidermal growth factor

- EIRE

Elicitor-responsive element

- FPKM

Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads

- GARE

Gibberellin-responsive element

- GSDS

Gene Structure Display Server

- HMM

Hidden Markov model

- JA

Jasmonic acid

- LTRE

Low-temperature-responsive element

- MeJARE

MeJA-responsive element

- MEME

Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation

- ML

Maximum-likelihood method

- MW

Molecular weight

- pI

Isoelectric point

- PTGS

Post-transcriptional gene silencing

- qPCR

Quantitative PCR

- RLK

Receptor-like kinase

- SA

Salicylic acid

- SARE

SA-responsive element

- TGS

Transcriptional gene silencing

- TYLCV

Tomato yellow leaf curl virus

- WAK

Wall-associated Kinase

- WAKL

WAK-like Kinase

- WAK/WAKL

WAK and WAKL

Authors’ contributions

YW and ZW conceived the study; XZ, JL, LY, and XW conducted experiments; XZ, HX, TH, and YW analyzed experimental data; XZ, YW, and ZW wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31701759, 31972235, and 32102162), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. LQ19C140001), and Zhejiang Basic Public Welfare Research Project of China (No. LGN19C140002). There is no role of the funding body in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. The authors declared that experimental research works on the plants described in this article comply with institutional, national, and international guidelines.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xueting Zhong, Email: zxt@zjhu.edu.cn.

Jiapeng Li, Email: ljpbangbangde@163.com.

Lianlian Yang, Email: yanglianlian929@163.com.

Xiaoyin Wu, Email: wxy2452675088@163.com.

Hong Xu, Email: 19802670032@163.com.

Tao Hu, Email: taohu@zju.edu.cn.

Yajun Wang, Email: wyj@zjhu.edu.cn.

Yaqin Wang, Email: yaqinwang@zju.edu.cn.

Zhanqi Wang, Email: zhqwang@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Zhong X, Wang ZQ, Xiao R, Cao L, Wang Y, Xie Y, et al. Mimic phosphorylation of a βC1 protein encoded by TYLCCNB impairs its functions as a viral suppressor of RNA silencing and a symptom determinant. J Virol. 2017;91(16):e00300–e00317. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00300-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li H, Zeng R, Chen Z, Liu X, Cao Z, Xie Q, et al. S-acylation of a geminivirus C4 protein is essential for regulating the CLAVATA pathway in symptom determination. J Exp Bot. 2018;69(18):4459–4468. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walker PJ, Siddell SG, Lefkowitz EJ, Mushegian AR, Adriaenssens EM, Alfenas-Zerbini P, et al. Changes to virus taxonomy and to the International Code of Virus Classification and Nomenclature ratified by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (2021) Arch Virol. 2021;166(9):2633–2648. doi: 10.1007/s00705-021-05156-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rojas MR, Macedo MA, Maliano MR, Soto-Aguilar M, Souza JO, Briddon RW, et al. World management of geminiviruses. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2018;56:637–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080615-100327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osterbaan LJ, Fuchs M. Dynamic interactions between plant viruses and their hosts for symptom development. J Plant Pathol. 2019;101(4):885–895. doi: 10.1007/s42161-019-00323-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhong X, Wang ZQ, Xiao R, Wang Y, Xie Y, Zhou X. TRAQ analysis of the tobacco leaf proteome reveals that RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) has important roles in defense against geminivirus-betasatellite infection. J Proteome. 2017;152:88–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.García-Arenal F, Zerbini FM. Life on the edge: geminiviruses at the interface between crops and wild plant hosts. Annu Rev Virol. 2019;6(1):411–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-092818-015536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farooq T, Umar M, She X, Tang Y, He Z. Molecular phylogenetics and evolutionary analysis of a highly recombinant begomovirus, cotton leaf curl Multan virus, and associated satellites. Virus Evol. 2021;7(2):veab054. doi: 10.1093/ve/veab054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beam K, Ascencio-Ibáñez JT. Geminivirus resistance: a minireview. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:1131. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.01131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prasad A, Sharma N, Hari-Gowthem G, Muthamilarasan M, Prasad M. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus: impact, challenges, and management. Trends Plant Sci. 2020;25(9):897–911. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2020.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marchant WG, Gautam S, Dutta B, Srinivasan R. Whitefly-mediated transmission and subsequent acquisition of highly similar and naturally occurring tomato yellow leaf curl virus variants. Phytopathology. 2022;112(3):720–728. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-06-21-0248-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gong P, Tan H, Zhao S, Li H, Liu H, Ma Y, et al. Geminiviruses encode additional small proteins with specific subcellular localizations and virulence function. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):4278. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24617-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gong P, Zhao S, Liu H, Chang Z, Li F, Zhou X. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus V3 protein traffics along microfilaments to plasmodesmata to promote virus cell-to-cell movement. Sci China Life Sci. 2022;65(5):1046–1049. doi: 10.1007/s11427-021-2063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao S, Gong P, Ren Y, Liu H, Li H, Li F, et al. The novel C5 protein from tomato yellow leaf curl virus is a virulence factor and suppressor of gene silencing. Stress Biol. 2022;2:19. doi: 10.1007/s44154-022-00044-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glick E, Zrachya A, Levy Y, Mett A, Gidoni D, Belausov E, et al. Interaction with host SGS3 is required for suppression of RNA silencing by tomato yellow leaf curl virus V2 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(1):157–161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709036105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang B, Yang X, Wang Y, Xie Y, Zhou X. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus V2 interacts with host histone deacetylase 6 to suppress methylation-mediated transcriptional gene silencing in plants. J Virol. 2018;92(18):e00036–e00018. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00036-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang L, Ding Y, He L, Zhang G, Zhu JK, Lozano-Duran R. A virus-encoded protein suppresses methylation of the viral genome through its interaction with AGO4 in the Cajal body. Elife. 2020;9:e55542. doi: 10.7554/eLife.55542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao W, Wu S, Barton E, Fan Y, Ji Y, Wang X, et al. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus V2 protein plays a critical role in the nuclear export of V1 protein and viral systemic infection. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:1243. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosas-Diaz T, Zhang D, Fan P, Wang L, Ding X, Jiang Y, et al. A virus-targeted plant receptor-like kinase promotes cell-to-cell spread of RNAi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(6):1388–1393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715556115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garnelo Gómez B, Zhang D, Rosas-Díaz T, Wei Y, Macho AP, Lozano-Durán R. The C4 protein from tomato yellow leaf curl virus can broadly interact with plant receptor-like kinases. Viruses. 2019;11(11):1009. doi: 10.3390/v11111009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corrales-Gutierrez M, Medina-Puche L, Yu Y, Wang L, Ding X, Luna AP, et al. The C4 protein from the geminivirus tomato yellow leaf curl virus confers drought tolerance in Arabidopsis through an ABA-independent mechanism. Plant Biotechnol J. 2020;18(5):1121–1123. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Padmanabhan C, Zheng Y, Shamimuzzaman M, Wilson JR, Gilliard A, Fei Z, et al. The tomato yellow leaf curl virus C4 protein alters the expression of plant developmental genes correlating to leaf upward cupping phenotype in tomato. PLoS One. 2022;17(5):e0257936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0257936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Macho AP, Lozano-Duran R. Molecular dialogues between viruses and receptor-like kinases in plants. Mol Plant Pathol. 2019;20(9):1191–1195. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang H, Zhu J, Gong Z, Zhu JK. Abiotic stress responses in plants. Nat Rev Genet. 2022;23(2):104–119. doi: 10.1038/s41576-021-00413-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolf S. Plant cell wall signalling and receptor-like kinases. Biochem J. 2017;474(4):471–492. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dievart A, Gottin C, Périn C, Ranwez V, Chantret N. Origin and diversity of plant receptor-like kinases. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2020;71:131–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-073019-025927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kohorn BD. WAKs; cell wall associated kinases. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13(5):529–533. doi: 10.1016/S0955-0674(00)00247-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verica JA, He ZH. The cell wall-associated kinase (WAK) and WAK-like kinase gene family. Plant Physiol. 2002;129(2):455–459. doi: 10.1104/pp.011028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kanneganti V, Gupta AK. Wall associated kinases from plants - an overview. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2008;14(1–2):109–118. doi: 10.1007/s12298-008-0010-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohorn BD. Cell wall-associated kinases and pectin perception. J Exp Bot. 2016;67(2):489–494. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Z, Ma W, Ren Z, Wang X, Zhao J, Pei X, et al. Characterization and expression analysis of wall-associated kinase (WAK) and WAK-like family in cotton. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;187:867–879. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.07.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Z. Plant growth: a matter of WAK seeing the wall and talking to BRI1. Curr Biol. 2022;32(12):R564–R566. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dou L, Li Z, Shen Q, Shi H, Li H, Wang W, et al. Genome-wide characterization of the WAK gene family and expression analysis under plant hormone treatment in cotton. BMC Genomics. 2021;22(1):85. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-07378-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li L, Li K, Ali A, Guo Y. AtWAKL10, a cell wall associated receptor-like kinase, negatively regulates leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(9):4885. doi: 10.3390/ijms22094885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sivaguru M, Ezaki B, He ZH, Tong H, Osawa H, Baluska F, et al. Aluminum-induced gene expression and protein localization of a cell wall-associated receptor kinase in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2003;132(4):2256–2266. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.022129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lou HQ, Fan W, Jin JF, Xu JM, Chen WW, Yang JL, et al. A NAC-type transcription factor confers aluminum resistance by regulating cell wall-associated receptor kinase 1 and cell wall pectin. Plant Cell Environ. 2020;43(2):463–478. doi: 10.1111/pce.13676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xia Y, Yin S, Zhang K, Shi X, Lian C, Zhang H, et al. OsWAK11, a rice wall-associated kinase, regulates Cu detoxification by alteration the immobilization of Cu in cell walls. Environ Exp Bot. 2018;150:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Amsbury S. Sensing attack: the role of wall-associated kinases in plant pathogen responses. Plant Physiol. 2020;183(4):1420–1421. doi: 10.1104/pp.20.00821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stephens C, Hammond-Kosack KE, Kanyuka K. WAKsing plant immunity, waning diseases. J Exp Bot. 2022;73(1):22–37. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erab422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu K, Cao J, Zhang J, Xia F, Ke Y, Zhang H, et al. Improvement of multiple agronomic traits by a disease resistance gene via cell wall reinforcement. Nat Plants. 2017;3:17009. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2017.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saintenac C, Lee WS, Cambon F, Rudd JJ, King RC, Marande W, et al. Wheat receptor-kinase-like protein Stb6 controls gene-for-gene resistance to fungal pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici. Nat Genet. 2018;50(3):368–374. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gadaleta A, Colasuonno P, Giove SL, Blanco A, Giancaspro A. Map-based cloning of QFhb.mgb-2A identifies a WAK2 gene responsible for Fusarium Head Blight resistance in wheat. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):6929. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43334-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zuo W, Chao Q, Zhang N, Ye J, Tan G, Li B, et al. A maize wall-associated kinase confers quantitative resistance to head smut. Nat Genet. 2015;47(2):151–157. doi: 10.1038/ng.3170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang P, Praz C, Li B, Singla J, Robert C, Kessel B, et al. Fungal resistance mediated by maize wall-associated kinase ZmWAK-RLK1 correlates with reduced benzoxazinoid content. New Phytol. 2019;221(2):976–987. doi: 10.1111/nph.15419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang N, Pombo MA, Rosli HG, Martin GB. Tomato wall-associated kinase SlWak1 depends on Fls2/Fls3 to promote apoplastic immune responses to Pseudomonas syringae. Plant Physiol. 2020;183(4):1869–1882. doi: 10.1104/pp.20.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feng H, Li C, Zhou J, Yuan Y, Feng Z, Shi Y, et al. A cotton WAKL protein interacted with a DnaJ protein and was involved in defense against Verticillium dahliae. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;167:633–643. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.11.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang J, Xie M, Wang X, Wang G, Zhang Y, Li Z, et al. Identification of cell wall-associated kinases as important regulators involved in Gossypium hirsutum resistance to Verticillium dahliae. BMC Plant Biol. 2021;21(1):220. doi: 10.1186/s12870-021-02992-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun Z, Song Y, Chen D, Zang Y, Zhang Q, Yi Y, et al. Genome-wide identification, classification, characterization, and expression analysis of the wall-associated kinase family during fruit development and under wound stress in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Genes. 2020;11(10):1186. doi: 10.3390/genes11101186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bailey TL, Johnson J, Grant CE, Noble WS. The MEME suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(W1):W39–W49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu B, Jin J, Guo AY, Zhang H, Luo J, Gao G. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(8):296–1297. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lescot M, Déhais P, Thijs G, Marchal K, Moreau Y, Van de Peer Y, et al. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30(1):325–327. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakasugi K, Crowhurst RN, Bally J, Wood CC, Hellens RP, Waterhouse PM. De novo transcriptome sequence assembly and analysis of RNA silencing genes of Nicotiana benthamiana. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59534. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu M, Ding X, Fu X, Lozano-Duran R. Transcriptional reprogramming caused by the geminivirus tomato yellow leaf curl virus in local or systemic infections in Nicotiana benthamiana. BMC Genomics. 2019;20(1):542. doi: 10.1186/s12864-019-5842-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Liu Y, Schiff M, Dinesh-Kumar SP. Virus-induced gene silencing in tomato. Plant J. 2002;31(6):777–786. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang LL, Wang XR, Wei XM, Huang H, Wu JX, Chen XX, et al. The autophagy pathway participates in resistance to tomato yellow leaf curl virus infection in whiteflies. Autophagy. 2016;12(9):1560–1574. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1192749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang Y, Liu T, Shen D, Wang J, Ling X, Hu Z, et al. Tomato yellow leaf curl virus intergenic siRNAs target a host long noncoding RNA to modulate disease symptoms. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15(1):e1007534. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu H, Zhang W, Kang Y, Fan Y, Yang X, Shi M, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of wall-associated kinase (WAK) gene family in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2022;16:317–31.

- 58.Li M, Ma J, Liu H, Ou M, Ye H, Zhao P. Identification and characterization of wall-associated kinase (WAK) and WAK-like (WAKL) gene family in Juglans regia and its wild related species Juglans mandshurica. Genes. 2022;13(1):134. doi: 10.3390/genes13010134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang S, Chen C, Li L, Meng L, Singh J, Jiang N, et al. Evolutionary expansion, gene structure, and expression of the rice wall-associated kinase gene family. Plant Physiol. 2005;139(3):1107–1124. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.069005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tocquard K, Lafon-Placette C, Auguin D, Muries B, Bronner G, Lopez D, et al. In silico study of wall-associated kinase family reveals large-scale genomic expansion potentially connected with functional diversification in Populus. Tree Genet Genomes. 2014;10(5):1135–1147. doi: 10.1007/s11295-014-0748-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zuo C, Liu Y, Guo Z, Mao J, Chu M, Chen B. Genome-wide annotation and expression responses to biotic stresses of the WALL-ASSOCIATED KINASE - RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE (WAK-RLK) gene family in apple (Malus domestica) Eur J Plant Pathol. 2019;153(3):771–785. doi: 10.1007/s10658-018-1591-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang B, Li P, Su T, Li P, Xin X, Wang W, et al. Comprehensive analysis of wall-associated kinase genes and their expression under abiotic and biotic stress in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis) J Plant Growth Regul. 2020;39(1):72–86. doi: 10.1007/s00344-019-09964-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tripathi RK, Aguirre JA, Singh J. Genome-wide analysis of wall associated kinase (WAK) gene family in barley. Genomics. 2021;113(1):523–530. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu X, Wang Z, Tian Y, Zhang S, Li D, Dong W, et al. Characterization of wall-associated kinase/wall-associated kinase-like (WAK/WAKL) family in rose (Rosa chinensis) reveals the role of RcWAK4 in Botrytis resistance. BMC Plant Biol. 2021;21(1):526. doi: 10.1186/s12870-021-03307-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang P, Zhou L, Jamieson P, Zhang L, Zhao Z, Babilonia K, et al. The cotton wall-associated kinase GhWAK7A mediates responses to fungal wilt pathogens by complexing with the chitin sensory receptors. Plant Cell. 2020;32(12):3978–4001. doi: 10.1105/tpc.19.00950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zaynab M, Peng J, Sharif Y, Albaqami M, Al-Yahyai R, Fatima M, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling of DUF221 gene family provides new insights into abiotic stress responses in potato. Front Plant Sci. 2022;12:804600. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.804600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kuzmin E, VanderSluis B, Nguyen Ba AN, Wang W, Koch EN, Usaj M, et al. Exploring whole-genome duplicate gene retention with complex genetic interaction analysis. Science. 2020;368(6498):eaaz5667. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz5667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tan Z, Wen X, Wang Y. Betula platyphylla BpHOX2 transcription factor binds to different cis-acting elements and confers osmotic tolerance. J Integr Plant Biol. 2020;62(11):1762–1779. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jin JF, Wang ZQ, He QY, Wang JY, Li PF, Xu JM, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the NAC transcription factor family in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) during aluminum stress. BMC Genomics. 2020;21(1):288. doi: 10.1186/s12864-020-6689-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bombarely A, Rosli HG, Vrebalov J, Moffett P, Mueller LA, Martin GB. A draft genome sequence of Nicotiana benthamiana to enhance molecular plant-microbe biology research. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2012;25(12):1523–1530. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-06-12-0148-TA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mistry J, Finn RD, Eddy SR, Bateman A, Punta M. Challenges in homology search: HMMER3 and convergent evolution of coiled-coil regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(12):e121. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mistry J, Chuguransky S, Williams L, Qureshi M, Salazar GA, Sonnhammer E, et al. Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D412–D419. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(7):3022–3027. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msab120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leng ZX, Liu Y, Chen ZY, Guo J, Chen J, Zhou YB, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the DUF4228 family in soybean and functional identification of GmDUF4228-70 in response to drought and salt stresses. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:628299. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.628299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhao W, Liu H, Zhang L, Hu Z, Liu J, Hua W, et al. Genome-wide identification and characterization of FBA gene family in polyploid crop Brassica napus. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(22):5749. doi: 10.3390/ijms20225749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He Y, et al. TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant. 2020;13(8):1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, Bennett C, Salzberg SL. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(8):907–915. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kovaka S, Zimin AV, Pertea GM, Razaghi R, Salzberg SL, Pertea M. Transcriptome assembly from long-read RNA-seq alignments with StringTie2. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):278. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1910-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Luo C, Wang ZQ, Liu X, Zhao L, Zhou X, Xie Y. Identification and analysis of potential genes regulated by an alphasatellite (TYLCCNA) that contribute to host resistance against tomato yellow leaf curl China virus and its betasatellite (TYLCCNV/TYLCCNB) infection in Nicotiana benthamiana. Viruses. 2019;11(5):442. doi: 10.3390/v11050442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gui X, Liu C, Qi Y, Zhou X. Geminiviruses employ host DNA glycosylases to subvert DNA methylation-mediated defense. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):575. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28262-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Protein sequences of WAK/WAKL of Nicotiana benthamiana, Arabidopsis, and tomato.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Cis-acting elements in the promoter regions of NbWAK/WAKL genes.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Tissue expression profiles of NbWAK/WAKL genes.

Additional file 4: Table S4. List of primers used in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files.