Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) adults have experienced pronounced declines in well-being. However, less is known about how changes to daily routines and settings, such as the shift to remote work within many occupations, may be playing a role in well-being outcomes. Drawing on a unique time diary data source (N = 3515 respondents and 7650 episodes) collected between April 2020–July 2021 through online crowdsourcing platforms, we conducted random effects analyses to examine how working from home has been associated with experienced well-being among LGBTQ and cisgender heterosexual workers in the United States during the pandemic. Findings indicate LGBTQ adults felt significantly less stressed and tired while doing paid work at home than while working at a workplace. In addition, working at a workplace, rather than working from home, appeared to be more detrimental to LGBTQ adults’ well-being compared to their non-LGBTQ counterparts. Adjusting for work characteristics explained some of the difference, whereas adjusting for family characteristics had little impact on the results. It is possible that for LGBTQ employees, working from home mitigates some of the minority stressors experienced during paid work.

Keywords: Mental health, LGBTQ, COVID, Remote work, Minority stress, Emotions, United States

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated shifts in daily experiences have taken a toll on Americans' mental health and well-being. Because of structural vulnerabilities and unequal distribution of stress exposure (Meyer et al., 2008), LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and other sexual and gender minority) individuals are among those particularly at risk for distress (Salerno et al., 2020) and have experienced distinct declines in well-being during the pandemic compared to their cisgender heterosexual counterparts (Baumel et al., 2021; Fish et al., 2021; Mitchell et al., 2022), including lower work-related well-being (Mendes and Pereira, 2021). However, the role of paid work—particularly working from home—in influencing sexual and gender minority peoples’ well-being during the pandemic has not been fully examined. Previous scholarship on LGBTQ work-family border experiences suggests working from home could be associated with enhanced well-being, such as if working remotely from a supportive home environment partially shields LGBTQ workers from stressors like workplace microaggressions. However, it could also be associated with diminished well-being, such as if a blurred border between work and home increases distress among LGBTQ workers who maintain strict separation between domains. Put differently, working remotely during the pandemic could be functioning as a “safe harbor” protective for well-being, or as a “blurred border” potentially detrimental to well-being.

The present study thus focuses on variation by work location in positive and negative indicators of experienced well-being during paid work activities among LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ (i.e., heterosexual and cisgender) adults in the U.S. during the pandemic. Experienced well-being captures moment-to-moment positive and negative emotions and states, such as how happy, stressed, or tired an individual feels (National Research Council, 2013). We examine three research questions: 1) how self-reported experienced well-being indicators vary while working from home compared to working in-person for LGBTQ workers; 2) whether associations between well-being and work location differ across LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers; and 3) whether work and family characteristics are contributing to well-being gaps across work location and LGBTQ status. We explore these questions using time diary data from the Assessing the Social Consequences of COVID-19 (ASCC) study. Because the pandemic fundamentally altered the patterns and practices of paid work, remote work will likely remain part of many class-advantaged occupations going forward (Bloom et al., 2021). Understanding its association with well-being for sexual and gender minority workers is important for supporting LGBTQ workers’ mental health and elucidating the complex links between work and well-being across social locations.

2. Background

2.1. COVID-19 and LGBTQ well-being disparities

Although the pandemic has harmed well-being broadly, declines have been larger for sexual and gender minority individuals (Baumel et al., 2021; Drabble and Eliason, 2021; Fish et al., 2021; Manning and Kamp Dush, 2022; Mitchell et al., 2022). Compared to heterosexual counterparts, lesbian, gay, and especially bisexual adults have experienced a disproportionate drop in well-being across multiple indicators, including psychological distress, mental health, and fatigue, since the onset of the pandemic (Fish et al., 2021). These patterns should be understood in relation to structural inequalities and stigma (Hatzenbuehler and Link, 2014), which already put LGBTQ individuals at risk of worse well-being outcomes relative to their heterosexual and cisgender counterparts prior to the pandemic (Bostwick et al., 2010; White Hughto et al., 2015). Existing social and economic disadvantages among LGBTQ individuals created distinct COVID-related well-being vulnerabilities (Salerno et al., 2020). For example, LGBTQ adults, particularly LGBTQ racialized minorities, were already more likely to be experiencing financial hardship (Badgett et al. 2019), working in occupations with greater economic and health risks (Salerno et al., 2020; Whittington et al., 2020), and facing particular threats to well-being from the intersection of racial discrimination and anti-LGBTQ stigma (e.g., English et al., 2018). Given these disparities, it is important to pay attention to factors that may be contributing to emotional well-being or distress among LGBTQ individuals during the pandemic.

2.2. LGBTQ workplace experiences and well-being

2.2.1. Well-being during work activities

Well-being experiences during paid work are influenced by multiple intersecting factors, from education and labor market structures shaping access to “good jobs” (Kalleberg, 2011) to interpersonal mistreatment at work. Research has shown that worse job conditions—often in precarious and/or demanding positions—are associated with worse well-being outcomes (e.g., Karasek, 1979; Schneider and Harknett, 2019). A smaller number of studies have examined experienced well-being during paid work activities. Compared to non-work activities, time spent in paid work is more likely to have negative emotions like stress as the dominant affective experience (Krueger et al., 2009; Stone et al., 2006). Less is known about how marginalized social statuses and identities may be related to distinct emotional experiences during paid work. Because of structural discrimination and chronic stressors to which LGBTQ individuals are exposed in the workplace, differences in experienced well-being during work activities may exist.

2.2.2. LGBTQ workplace mistreatment

Many sexual and gender minority individuals face discrimination, harassment, and other stressors in the workplace, particularly among those with multiply-marginalized identities (Bowleg et al., 2008; Cech and Rothwell 2019; Goldberg and Smith, 2013; Ragins and Cornwell, 2001; Sawyer et al., 2016; Sawyer et al., 2017). Over a quarter of LGB workers and nearly eight in ten transgender workers in the U.S. have experienced harassment or discrimination at work (Grant et al., 2011; Sears and Mallory, 2011). Although mistreatment can take the form of overt hostility or employment discrimination, it can also present as “systemic informal degradations” of everyday work life (Cech and Rothwell 2019:26) or workplace microaggressions. LGBTQ workers report that experiencing microaggressions at work diminishes well-being, impacts coworker relationships, and harms daily mood (Galupo and Resnick, 2016).

This type of strain has been conceptualized as one form of minority stress (Brooks, 1981; Meyer, 2003), or the ongoing, additional, socially-based stress to which people with marginalized social statuses are subject in their daily lives. Meyer framed minority stress as occurring on a continuum from distal processes (external stressful conditions, such as an unaccepting work environment) to proximal processes (internal perceptions, such as expectations of rejection or identity concealment), both of which influence well-being outcomes. This framework's focus on 1) discriminatory social structures/environments in relation to minority statuses and 2) proximal minority identity processes as dual, interrelated influences on well-being makes it appropriate for studying experienced well-being while working for LGBTQ individuals. Indeed, past research shows experiencing distal and proximal workplace minority stressors is associated with psychological distress among sexual minority workers (Velez et al., 2013) and may affect daily emotions during work activities in addition to the more global impact on well-being. As Meyer and others have noted, however, minority stressors are not experienced uniformly. Uneven distribution of opportunities and discrimination in organizations shape unequal work contexts, characteristics, and experiences for LGBTQ workers across race/ethnicity, gender, parental status, and occupational position (e.g., Alfrey and Twine, 2017). For example, workplace strains may be magnified for Black, Latinx, Asian, and other racialized minority LGBTQ individuals if they already face hypervisibility, discrimination, or exclusion at work (Bowleg et al., 2008; Cech and Rothwell 2019; Ragins et al., 2003; Wingfield and Wingfield 2014). Factors like supervisor support (Goldberg and Smith, 2013), work team structures (Cech and Waidzunas, 2022), the degree to which one is “out” at work (Velez et al., 2013), and work climate and policies (Webster et al., 2018) can also influence work experiences and the degree to which they are experienced as stressful or emotionally depleting.

2.2.3. Strategies to minimize exposure to mistreatment

For some sexual and gender minority employees, workplace experiences are marked by decisions about identity management and pressure to maintain spatial and psychological borders between work and family (Holman, 2018; Ragins et al., 2007). In response to structural or interpersonal discrimination, some LGBTQ workers use strict separation of life domains—e.g., not mentioning their families in workplace conversations—to mitigate stress (Sawyer et al., 2017). This could be understood as a form of “trajectory guarding” (Hart, 2021), or guiding interactions with an aim of minimizing exposure to potential mistreatment. For example, a U.S.-based study with employed, primarily white individuals in same-gender relationships found that because some sexual minority employees did not perceive their families as conforming to how their workplaces defined family, they concealed or differentially disclosed information about partners and children (Sawyer et al., 2017). Similarly, a study on workplace stress among middle-class Black lesbians documented stressful workplace experiences related to the intersection of their identities as racial and sexual minorities; one third of participants avoided discussing their sexual orientation at work or sharing personal information during conversations about weekend plans (Bowleg et al., 2008). Whereas some LGBTQ workers feel comfortable with “domain integration” (Holman, 2018:173) between work and family, for others the blurring of this border may increase distress.

In sum, research demonstrates that unequal exposure to distal and proximal work-related stressors and associated impact on well-being shapes subjective experiences while working and influences mitigation strategies employed by LGBTQ workers. However, these studies have not generally considered the role of work location. Further, for LGBTQ individuals who aim to mitigate workplace stressors by maintaining a clear work/home border, it is unknown how remote work may impact well-being.

2.3. Work location and well-being

Research exploring the relationship between work location and well-being has produced mixed results, with some studies finding an association between remote work and increased positive emotions (Anderson et al., 2014) and other studies finding the opposite (Song and Gao, 2020; for a review, see Charalampous et al., 2018). Pre-pandemic some employees experienced increased job satisfaction while telecommuting, but social connections in workplaces also provide important benefits (Allen et al., 2015). Studies have found well-being benefits when employees gain more control over the location and timing of their paid work, including the ability to work remotely (Moen et al., 2016).

However, the widespread shift within class-advantaged occupations to working from home during the pandemic and an increase in reliance on video conferencing (Parker et al., 2020) changed the nature of remote work in multiple ways. First, the shift marked a pronounced “risk divide” (Grusky et al., 2021) between in-person and remote work. People employed in jobs that could be done remotely—which are held at higher levels by white, Asian, and non-Hispanic workers (Grusky et al., 2021) and people with college and postgraduate degrees (Parker et al., 2020)—were more insulated from health and economic risks (i.e., job loss, reduction in hours) compared to those in face-to-face jobs. Working from home also shifted from an often employee-driven arrangement to a mandatory arrangement. Further, the closure of schools and daycares shaped parents’ remote work experiences, particularly mothers of young children, with parents reporting stress, time pressure, and interruptions (Chung et al., 2020; Lyttelton et al., 2022).

Other research conducted since the onset of the pandemic exploring well-being while working from home has also produced mixed results. Studies in the U.S. and Italy found working from home and social isolation from co-workers linked to worse mental health (Galanti et al., 2021; Xiao et al., 2021). However, emerging research on work experiences during the pandemic suggests heterogenous experiences across groups. For example, remote work was found to be linked overall to better well-being compared to returning to in-person work, but with complex well-being patterns across intersections of race, gender, education, and managerial status (Fan and Moen, 2022). One study of full-time knowledge workers found Black, Hispanic, and Asian workers were more likely than their white counterparts to prefer remote or hybrid work, and have experienced sharper gains in perceptions of a “sense of belonging at work” and being “treated fairly at work” (Future Forum, 2022). Considering only well-being levels overall could be masking heterogeneity in emotional experiences across social locations.

2.4. LGBTQ status and well-being across work locations

Based on these strands of research, one could expect working from home during COVID to be associated with greater or lower well-being among LGBTQ workers. On one hand, reliance on video conferencing (Parker et al., 2020) and the potential for increased visibility of family members might be linked to reduced well-being for some sexual and gender minority workers, with coworkers now in each other's homes through “virtual sight lines” (Kniffin et al., 2021:66) and the border between work and home blurred. These may be particularly salient concerns among workers with marginalized or multiply-marginalized identities, for whom increased visibility of family life may be accompanied by concerns about exposure to judgment or discriminatory treatment. Someone who has worked to maintain a clear border between family and work within an unsupportive work climate—such as avoiding discussing romantic relationships with coworkers—could experience working from home, where a partner or child could be visible during meetings, as detrimental to well-being.

On the other hand, working from home means fewer opportunities for informal interactions with coworkers. Although decreased communication with colleagues among people working from home during COVID is linked to decreased well-being overall (Xiao et al., 2021), work relationships and environments vary and emerging evidence suggests that for some, working from home is a “source of relief” from microaggressions or exclusion (Goldberg, 2022; Future Forum, 2022). Data from the ASCC (Table 1 ) shows sexual and gender minority workers were more likely than their cisgender heterosexual counterparts to report that pre-pandemic interactions with coworkers were exhausting (data not shown indicate this is the case across racial/ethnic groups). Thus, it is plausible that working from home could be linked to increased emotional well-being for LGBTQ individuals, if working from home provides a “safe harbor” (Kniffin et al., 2021:66) where workers experience less exposure to informal conversations about family life and are more insulated from microaggressions related to sexual orientation, gender identity, race, and/or other statuses.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of selected independent variables by workers’ sexual orientation/gender identity.

| LGBTQ | Non-LGBTQ | Test score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 29.75 | 34.50 | p < 0.001 |

| (8.38) | (9.40) | ||

| Gender (%) | p < 0.001 | ||

| Men | 28.6 | 48.3 | |

| Women | 61.7 | 51.7 | |

| Othera | 9.7 | 0 | |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | p < 0.001 | ||

| White | 70.0 | 68.2 | |

| Latinx/Hispanic | 3.7 | 5.8 | |

| Black/African American | 7.9 | 10.8 | |

| Asian | 4.3 | 8.2 | |

| Multiracial/otherb | 14.1 | 7.1 | |

| Pre-COVID employment status (%) | p < 0.001 | ||

| Full-time | 46.5 | 63.6 | |

| Part-time | 22.0 | 13.4 | |

| Self-employed | 14.7 | 11.0 | |

| Not employed | 16.8 | 12.0 | |

| During-COVID employment status (%) | p < 0.001 | ||

| Full-time | 41.7 | 59.5 | |

| Part-time | 19.0 | 12.3 | |

| Self-employed | 16.3 | 12.1 | |

| Not employed | 23.0 | 16.1 | |

| Total work time on the diary day | 311.30 | 375.45 | p < 0.001 |

| (196.71) | (188.59) | ||

| Work from home over 50% of time (%) | 70.0 | 68.4 | p = 0.357 |

| Pre-COVID co-worker interaction exhaustion (%) | p < 0.001 | ||

| Never | 4.9 | 9.3 | |

| Rarely | 18.5 | 25.2 | |

| Sometimes | 30.3 | 33.9 | |

| Often | 14.8 | 12.2 | |

| Always | 8.6 | 4.0 | |

| Not applicable | 22.9 | 15.4 | |

| Have a college degree (%) | 53.2 | 66.5 | p < 0.001 |

| Household income (%) | p < 0.001 | ||

| Lower than 20k | 19.0 | 8.2 | |

| 20k-60k | 40.7 | 37.2 | |

| 60k-100k | 24.5 | 29.8 | |

| Higher than 100k | 15.7 | 24.8 | |

| Household income change (%) | p < 0.001 | ||

| Decreased | 36.6 | 34.0 | |

| Stayed the same | 40.7 | 48.9 | |

| Increased | 22.7 | 17.1 | |

| Home Ownership (%) | p < 0.001 | ||

| Own with mortgage | 32.6 | 41.2 | |

| Own in full | 13.2 | 15.7 | |

| Rented or occupied | 54.2 | 43.1 | |

| Married (%) | 20.3 | 43.1 | p < 0.001 |

| Live with spouse/partner (%) | 41.6 | 57.6 | |

| Live with parents/siblings (%) | 34.5 | 23.3 | |

| Live with friends/roommates/others (%) | 19.7 | 10.2 | |

| Number of household children | 0.19 | 0.52 | p < 0.001 |

| (0.72) | (1.02) | ||

| N of respondents | 864 | 2651 | |

Notes.

Other includes non-binary, transgender, agender, gender non-conforming, or another gender.

Other includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Middle Eastern or North African, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and another race/ethnicity. Small sample sizes did not allow for analysis of these groups separately.

It is important to note, however, home may not be a safe harbor for all LGBTQ adults. For example, LGBTQ individuals may co-reside with unaccepting family members or roommates, potentially navigating minority stressors both at work and at home. This is particularly true during COVID-19, when some sexual minority young adults have been forced to move back in with parents who do not accept their identities (Salerno et al., 2021) or into other unsafe conditions (Drotning et al., 2022).

2.5. The present study

Most previous research on LGBTQ workplace experiences and well-being has not foregrounded the role of work location; similarly, most research on work location and well-being has not focused on heterogeneity across social locations. This study contributes to these literatures by investigating three research questions:

-

1.

Do LGBTQ workers experience better or worse experienced well-being when working from home compared to working at workplaces during COVID?

-

2.

How does the association between well-being and work location vary for LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ adults?

-

3.

How do SES, workplace characteristics, and family characteristics account for different associations between work location and well-being for LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers?

We anticipate the experienced well-being of both LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers during COVID will vary by work location. We also expect work location to impact LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers’ well-being differently. Because the literature is inconclusive on how sexual or gender minority status may moderate associations between work location and emotions, we do not formulate formal hypotheses related to these questions.

3. Methods

3.1. Data

We used data from the Assessing the Social Consequences of COVID-19 (ASCC) study, a longitudinal online survey asking U.S. adults about their daily behaviors and attitudes during the pandemic. Participants were contacted using MTurk and Prolific Academic, crowdsourcing platforms used to recruit participants for surveys, which have been found to produce high-quality data (Peer et al., 2017). Time use data during the pandemic were collected in the second (April–May 2020), third (October–November 2020), and fourth (April–July 2021) waves of the ASCC study using an online implementation of the Day Reconstruction Method, shown to produce valid, reliable activity measures across a 24-h day (Kahneman et al., 2004; Rinderknecht et al., 2022).

ASCC time diary data is particularly suitable for exploring LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers' emotional well-being across work locations during the pandemic. First, ASCC is one of the only studies that has collected data on U.S. adults’ time use and the flow of emotional experiences in most daily activities during COVID. Second, ASCC collected self-reported information on sexual orientation and gender from respondents. To our knowledge, it is the only U.S. data source that collected time diaries and emotions for both partnered and unpartnered self-identified sexual and gender minority adults during the pandemic.

The second, third, and fourth waves of the ASCC study had 2208, 1262, and 2821 respondents. We restricted the analytic sample to working-age respondents (age 18–59) who reported paid work as one of their activities on the diary day. This reduced the number of respondents to 1158 in wave 2, 686 in wave 3, and 1728 in wave 4. Respondents who reported themselves as unemployed or not in the labor force during COVID might still engage in informal income-generating activities or job searching. Dropping these non-employed respondents from the analytic sample had little impact on the results; we report results that include them. After dropping cases with missing values, the final analytic sample included 1144 respondents (2438 work episodes) in wave 2, 672 respondents (1410 work episodes) in wave 3, and 1699 respondents (3802 work episodes) in wave 4. Among them, 260 respondents were interviewed in both wave 2 and 3, 81 in both wave 2 and 4, 75 in both wave 3 and 4, and 173 in all waves.

For all analyses, we pooled wave 2, 3, and 4 data. We took this approach because the number of employed LGBTQ workers who reported doing paid work at a workplace on the diary day in waves 2 and 3 was too small if analyzed separately to generate reliable results (29 respondents in wave 2; 31 respondents in wave 3). Also, supplementary analyses that included interactions of interview wave with key independent variables did not show significant differences across waves (results available on request).

3.2. Measures

Dependent variables: respondents' emotions when doing paid work. Respondents were asked to evaluate on a scale from 1 (very little) to 7 (very much so) how they felt during each work episode across a list of emotions. We examined workers’ feelings of stressed, tired, and meaningful, which are important dimensions of feelings toward paid work. For example, commonly used measures of job burnout identify exhaustion as an important manifestation of job stress (Maslach et al., 2001) or conceptualize burnout as the erosion of a perception of work as meaningful and engaging (Maslach and Leiter, 1997; Maslach et al., 2001). The ASCC survey includes affective measures for these emotions that are validated and have been used on the ATUS (Lee et al., 2016). We also tested other emotions (e.g. pleased, calm, unhappy), but did not observe significant differences between LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers in how work location was associated with their experiences of these emotions (see Online Appendix).

Key independent variables: the first was respondents' self-reported sexual orientation and gender identity. Respondents reported their sexual orientation (lesbian or gay, bisexual, straight, or a sexual orientation not listed), sex assigned at birth (female, male, intersex), and current gender (woman, man, a gender not listed). We used this information to construct a binary variable (0 = non-LGBTQ, 1 = LGBTQ). LGBTQ included sexual minorities (any respondent who self-identifies as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or another sexual orientation such as queer, pansexual, or questioning) and gender minorities (any respondent who identifies with a current gender different from their assigned sex at birth, and those who identify as transgender, non-binary, agender, genderfluid, or another gender). The second key independent variable was the respondents' location of work for each work episode (0 = workplace, 1 = home, and 2 = other locations). Only a small percentage of work episodes happened at locations other than a workplace or the respondent's home (1.9 percent in wave 2, 4.2 percent in wave 3, and 3.1 percent in wave 4). We did not present results for this group due to concerns over result reliability.

Control variables: covariates included respondents' age (in years), age-squared, current gender, race and ethnicity (white, Latinx/Hispanic, Black/African American, Asian, and multiracial or other), and interview wave (wave 2, 3, and 4). These are potential predictors of respondents' experienced well-being during paid work activities (e.g., Flèche and Smith, 2017; Kapteyn et al., 2015). Respondents' work characteristics were measured by the duration of each work episode, total work time on the diary day (both measured in minutes), employment status (full-time, part-time, self-employed, and not employed), occupation, and whether they spent more than 50 percent of paid work time working from home (yes/no) during COVID. Respondents also retrospectively reported their employment status and how often they felt exhausted when interacting with co-workers (never, rarely, sometimes, often, always, and not applicable—for respondents who were not employed or did not have co-workers) before the pandemic. Because respondents' work characteristics, especially whether they could work from home, were highly correlated with their socioeconomic status (SES), we also controlled for respondents' education (0 = no college degree, 1 = college degree), whether they were enrolled in school (yes/no), annual household income (lower than $20,000, $20,000–60,000, $60,000–100,000, and higher than $100,000), change in household income following the pandemic outbreak (decreased, stayed the same, or increased), and home ownership (owned with mortgage, owned in full, and rented or occupied). Respondents’ family characteristics included their marital status (married/not married), whether they co-resided with a spouse/partner, parents/siblings, roommates/friends/others (yes/no), and the number of co-residing minor children.

3.3. Analytic strategies

To explore how the association between work location and emotional experiences varied for LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers, we conducted random effects analyses with respondents' emotions during paid work episodes as dependent variables and the interaction of respondents' sexual orientation/gender identity and work location as the key independent variables. Random effects models can account for the multiple work episodes nested within individuals and adjust for non-independent measurement errors in these episodes. We then explored factors that could be playing a role in the impact of work location on LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers' emotional experiences. This was done by adding respondents’ SES, work, and family characteristic variables into the models and observing changes in the coefficients of key independent variables. We also ran several sensitivity analyses, including limiting the analytic sample to one wave per person if the respondent was interviewed in more than one wave, and weighting the data to match the 2018 General Social Survey (see Online Appendix). Results are substantively similar across these sensitivity analyses.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive statistics

Table 1, Table 2, and Fig. 1 show descriptive statistics of LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ adults who reported doing paid work on the time diary day. Compared with non-LGBTQ workers, LGBTQ workers were younger, more likely to identify as women, more likely to identify as multiracial or as members of an “other” racial group, and had lower levels of education and household income (Table 1). Further, LGBTQ workers were less likely to be married or co-reside with a spouse/partner and minor children, but more likely to live with parents, siblings, friends, roommates, or others during the pandemic.

Table 2.

Duration of each work episode for LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers by work location.

| LGBTQ |

Non-LGBTQ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workplace | Home | Workplace | Home | |

| Duration of each work episode | 254.91 | 127.15 | 241.01 | 145.52 |

| (163.70) | (112.33) | (165.42) | (113.28) | |

| N of work episodes | 377 | 1297 | 1480 | 4272 |

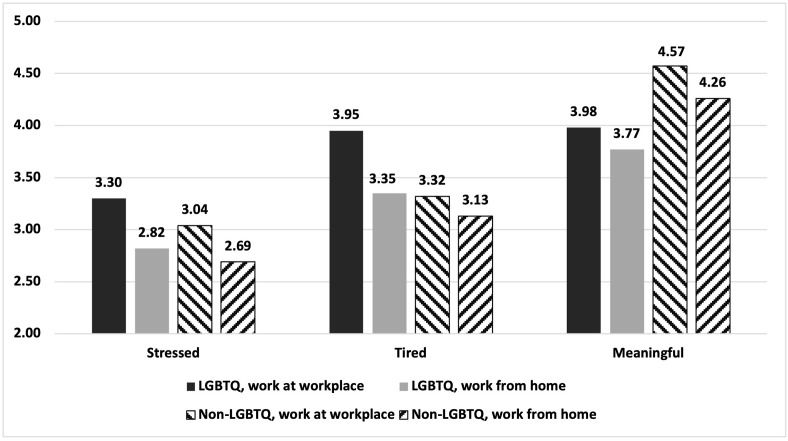

Fig. 1.

Descriptive statistics of LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers' emotions during paid work by work location.

Non-LGBTQ workers were more likely to work full-time than LGBTQ workers before and during the pandemic (Table 1). On the time diary day, LGBTQ workers reported shorter total work time than non-LGBTQ workers. LGBTQ workers' work episodes were shorter than those of non-LGBTQ workers when working from home, whereas when working at a workplace, LGBTQ workers' work episodes were slightly longer than those of non-LGBTQ workers (Table 2). Further, before the pandemic, LGBTQ workers’ frequency of reporting co-worker interaction exhaustion was higher than that of non-LGBTQ workers (Table 1).

Respondents' experienced well-being while working during the pandemic varied by LGBTQ status and work location (Fig. 1). Although all workers reported higher levels of stress when working at a workplace than when working at home, the gap in stress level by work location was larger among LGBTQ workers than non-LGBTQ workers. A similar pattern can be observed in workers’ feelings of tiredness. Further, workers generally found working at a workplace to be more meaningful than working at home. Regardless of work location, non-LGBTQ workers reported experiencing time in work activities as more meaningful than LGBTQ workers.

4.2. LGBTQ status, work location, and emotions while working

We found the impact of work location on workers' feelings of stress and tiredness was significantly different for LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers. No significant difference was observed in perceived meaningfulness, so we exclude the results to conserve space. Models 1 A and 2 A in Table 3 show results of the random effects models without controlling for work and family characteristics. For ease of interpretation, we also present the predicted means of LGBTQ workers' and non-LGBTQ workers' feelings of stress and tiredness by work location (Fig. 2 ). The results show that LGBTQ workers reported significantly higher levels of stress when working at a workplace (3.48) compared to working from home (2.75). Non-LGBTQ workers also felt more stressed when working at workplaces than working at home (3.11 vs. 2.71), but work location had significantly smaller effects on stress for them than for LGBTQ workers. Put another way, working at a workplace during the pandemic was particularly detrimental to LGBTQ workers’ stress levels.

Table 3.

Random effects models of associations between work location and emotions for LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers (N = 7650).

| Stressed |

Tired |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 A | Model 1 B | Model 1C | Model 2 A | Model 2 B | Model 2C | |

| LGBTQ (ref. non-LGBTQ) | 0.368** | 0.249* | 0.240* | 0.520*** | 0.414*** | 0.412*** |

| (0.116) | (0.110) | (0.110) | (0.118) | (0.118) | (0.118) | |

| Work from home (ref. work at workplace) | −0.395*** | −0.297** | −0.300** | −0.106 | 0.307** | 0.306** |

| (0.065) | (0.093) | (0.093) | (0.070) | (0.111) | (0.111) | |

| LGBTQ x Work from home | −0.329* | −0.215+ | −0.214+ | −0.407** | −0.308* | −0.308* |

| (0.128) | (0.121) | (0.121) | (0.131) | (0.131) | (0.132) | |

| Interview wave (ref. wave 2) | ||||||

| Wave 3 | −0.002 | −0.020 | 0.001 | 0.010 | −0.050 | −0.020 |

| (0.063) | (0.063) | (0.064) | (0.065) | (0.064) | (0.064) | |

| Wave 4 | −0.006 | −0.003 | 0.009 | 0.065 | 0.006 | 0.022 |

| (0.055) | (0.055) | (0.056) | (0.058) | (0.059) | (0.059) | |

| Age | 0.050** | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.043* | 0.041+ | 0.034 |

| (0.019) | (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.021) | (0.022) | |

| Age-squared | −0.001*** | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001** | −0.001** | −0.001* |

| (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | |

| Gender (ref. men) | ||||||

| Women | −0.012 | 0.008 | 0.006 | 0.222*** | 0.213*** | 0.204*** |

| (0.056) | (0.056) | (0.057) | (0.057) | (0.058) | (0.058) | |

| Othera | 0.298 | 0.300 | 0.286 | 0.173 | 0.110 | 0.092 |

| (0.196) | (0.190) | (0.191) | (0.213) | (0.211) | (0.212) | |

| Race/ethnicity (ref. White) | ||||||

| Latinx/Hispanic | −0.310* | −0.344** | −0.361** | −0.008 | −0.056 | −0.069 |

| (0.121) | (0.112) | (0.113) | (0.121) | (0.116) | (0.116) | |

| Black/African American | 0.039 | 0.086 | 0.077 | 0.055 | 0.051 | 0.038 |

| (0.096) | (0.093) | (0.094) | (0.095) | (0.095) | (0.097) | |

| Asian | 0.216+ | 0.154 | 0.154 | 0.217* | 0.235* | 0.253* |

| (0.111) | (0.107) | (0.109) | (0.108) | (0.105) | (0.107) | |

| Multiracial/otherb | −0.040 | −0.087 | −0.096 | 0.007 | −0.029 | −0.037 |

| (0.096) | (0.093) | (0.093) | (0.102) | (0.100) | (0.100) | |

| Duration of each work episode | 0.002*** | 0.002*** | <0.001* | <0.001* | ||

| (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | |||

| Total work time on the diary day | <0.001+ | <0.001+ | 0.001*** | 0.001*** | ||

| (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | |||

| Work from home over 50% of time (ref. no) | 0.152 | 0.150 | −0.467*** | −0.468*** | ||

| (0.094) | (0.094) | (0.106) | (0.106) | |||

| During-COVID employment (ref. full-time) | ||||||

| Part-time | 0.022 | 0.008 | −0.032 | −0.042 | ||

| (0.106) | (0.106) | (0.110) | (0.110) | |||

| Self-employed | −0.106 | −0.109 | −0.169 | −0.170 | ||

| (0.121) | (0.120) | (0.133) | (0.133) | |||

| Not employed | −0.099 | −0.111 | −0.128 | −0.139 | ||

| (0.112) | (0.112) | (0.109) | (0.109) | |||

| Pre-COVID employment (ref. full-time) | ||||||

| Part-time | 0.184+ | 0.181+ | 0.234* | 0.241* | ||

| (0.104) | (0.104) | (0.105) | (0.106) | |||

| Self-employed | 0.135 | 0.138 | 0.261+ | 0.271+ | ||

| (0.130) | (0.129) | (0.141) | (0.140) | |||

| Not employed | 0.007 | 0.005 | 0.117 | 0.129 | ||

| (0.163) | (0.164) | (0.180) | (0.180) | |||

| Pre-COVID co-worker interaction exhaustion (ref. never) | ||||||

| Rarely | 0.296** | 0.293** | 0.291** | 0.291** | ||

| (0.100) | (0.100) | (0.106) | (0.106) | |||

| Sometimes | 0.715*** | 0.709*** | 0.662*** | 0.663*** | ||

| (0.098) | (0.098) | (0.102) | (0.103) | |||

| Often | 0.854*** | 0.853*** | 0.881*** | 0.886*** | ||

| (0.112) | (0.112) | (0.120) | (0.120) | |||

| Always | 1.071*** | 1.067*** | 1.234*** | 1.238*** | ||

| (0.164) | (0.164) | (0.161) | (0.161) | |||

| Not applicable | 0.458** | 0.444** | 0.631*** | 0.620*** | ||

| (0.141) | (0.141) | (0.148) | (0.148) | |||

| College degree (ref. no) | 0.083*** | 0.086*** | −0.004 | −0.003 | ||

| (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.023) | (0.023) | |||

| Currently enrolled in school (ref. no) | 0.060 | 0.058 | 0.173* | 0.169* | ||

| (0.069) | (0.069) | (0.075) | (0.075) | |||

| Household income (ref. lower than 20k) | ||||||

| 20k-60k | −0.014 | −0.024 | 0.034 | 0.023 | ||

| (0.095) | (0.095) | (0.098) | (0.099) | |||

| 60k-100k | −0.099 | −0.119 | −0.068 | −0.091 | ||

| (0.103) | (0.104) | (0.106) | (0.107) | |||

| Higher than 100k | −0.193+ | −0.212+ | −0.175 | −0.197+ | ||

| (0.108) | (0.110) | (0.113) | (0.115) | |||

| Household income change (ref. decreased) | ||||||

| Stayed the same | −0.221*** | −0.212*** | −0.158** | −0.148* | ||

| (0.063) | (0.063) | (0.061) | (0.061) | |||

| Increased | −0.180* | −0.171* | −0.219* | −0.213* | ||

| (0.086) | (0.087) | (0.087) | (0.088) | |||

| Home Ownership (ref. own with mortgage) | ||||||

| Own in full | 0.047 | 0.040 | 0.157+ | 0.153+ | ||

| (0.085) | (0.086) | (0.084) | (0.084) | |||

| Rented or occupied | 0.069 | 0.078 | 0.024 | 0.029 | ||

| (0.061) | (0.063) | (0.062) | (0.064) | |||

| Not married (ref. married) | 0.142+ | 0.194* | ||||

| (0.083) | (0.084) | |||||

| Live with spouse/partner (ref. no) | −0.088* | −0.109** | ||||

| (0.042) | (0.039) | |||||

| Live with parents/siblings (ref. no) | 0.128+ | 0.077 | ||||

| (0.075) | (0.074) | |||||

| Live with friends/roommates/others (ref. no) | 0.086 | −0.009 | ||||

| (0.083) | (0.088) | |||||

| Number of household children | 0.035 | 0.057+ | ||||

| (0.033) | (0.033) | |||||

| Constant | 2.498*** | 1.938*** | 1.824*** | 2.927*** | 1.990*** | 1.957*** |

| (0.352) | (0.426) | (0.458) | (0.361) | (0.448) | (0.491) | |

Notes: Results present coefficients from random effects models. Standard errors in parentheses. Coefficients for occupation were omitted to conserve space. + p < 0.1, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Other includes non-binary, transgender, agender, gender non-conforming, or another gender.

Other includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Middle Eastern or North African, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and another race/ethnicity.

Fig. 2.

Predicted means of LGBTQ workers' and non-LGBTQ workers' feelings of stress and tiredness by work location (N = 7650).

Notes: Results are predicted means from random effects models (Model 1 A and 2 A in Table 3). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Regarding feelings of tiredness, the results show LGBTQ workers’ levels of tiredness when working at workplaces (3.86) were significantly higher than when working from home (3.35). In contrast, non-LGBTQ workers reported similar levels of tiredness when working at workplaces (3.33) and at home (3.23).

Model 1 B and 2 B in Table 3 show that adjusting for SES and work characteristics, particularly the duration of each work episode, total work time on the diary day, and pre-pandemic co-worker interaction exhaustion, explained about 35 percent of the difference between LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers in work locations’ impact on stress and approximately 24 percent for tiredness. Supplementary path analyses using structural equation modeling confirmed the differences in stress and tiredness could be partially explained by the mediating influence of having different work episode durations and total work times on the diary day (Online Appendix). In contrast, adding family characteristic variables (Model 1C and 2C in Table 3) to the models had little impact on the interaction term coefficients.

5. Discussion

Does work location influence LGBTQ workers' experienced well-being while working for pay during the pandemic? Further, does the impact of work location on emotional experience vary for LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers? Our analysis revealed significant differences between LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers in the impact of work location on their feelings of stress and tiredness while working. This difference could mainly be attributed to LGBTQ workers' higher stress and tiredness levels while working at a workplace relative to workers in all other groups. Compared with non-LGBTQ workers, working at workplaces instead of from home appeared to be more detrimental to LGBTQ workers’ experienced well-being.

We found employees' work characteristics—specifically the duration of each work episode and total time spent on paid work—mediated some of the differences between LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers in how work locations predicted stress and tiredness. We found that LGBTQ workers on average spent a shorter time on paid work on the diary day than non-LGBTQ workers, and LGBTQ workers also had shorter work episodes than non-LGBTQ workers when working from home. However, when working at a workplace, the duration of LGBTQ workers' work episodes was slightly longer than that of non-LGBTQ workers (Table 2). It is possible that LGBTQ adults who work in-person during the pandemic tend to be in positions with more rigid schedules and less control over their pace of work. LGBTQ workers in the ASCC study were less likely to hold management or professional jobs, and more likely to hold service and sales sector positions than non-LGBTQ workers (Online Appendix). This is consistent with GSS data showing LGBTQ people are disproportionately represented in industries highly impacted by the pandemic such as restaurant and hospital-based jobs (Whittington et al., 2020). These workers may be unable to take a break when they feel tired or stressed. Further, the fact that many such positions require face-to-face work means workers are exposed to higher risks of infection (Grusky et al., 2021) as well as potentially tense COVID-related interactions, such as around mask rules. During the pandemic, working at workplaces may, therefore, be particularly stressful and exhausting for individuals in these positions, exacerbating already-existing work strains. In our analysis, controlling for workers’ occupational category had limited impact on how work location predicts levels of stress and tiredness differently between LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers; however, this may be because the ASCC occupation variable is too broad to fully capture position differences between workers.

Another possible contributing factor for LGBTQ workers' higher stress and tiredness levels when working at workplaces is greater exposure to microaggressions and other forms of minority stress often experienced in these settings. Overall, LGBTQ workers reported finding interactions with co-workers to be exhausting more frequently than non-LGBTQ workers in pre-pandemic times (Table 1). When working from home, LGBTQ individuals may be less exposed to interpersonal mistreatment or conversations about romantic and family life which, for some LGBTQ individuals, is linked to ongoing stressful decision-making about identity disclosure or burdensome “trajectory guarding” (Hart, 2021). This would be consistent with findings that gay and lesbian workers are more likely to concentrate in jobs with “task independence,” or the ability to carry out one's work without relying much on others, as a way to manage workplace stigma (Tilcsik et al., 2015). For LGBTQ employees working in a workplace, experiencing increased COVID-related stressors (i.e. challenging customer interactions, increased health risks) on top of ongoing workplace minority stressors—and the higher burden of emotion work associated with navigating such stressors—may contribute to the disparities in experienced well-being. Although we cannot directly test this theory with the data, results showing LGBTQ workers' emotions vary more across work locations than non-LGBTQ workers, and that pre-pandemic co-worker interaction exhaustion is one significant factor, are consistent with this explanation.

The alternative expectation, that a “blurred” border between work and home among remote LGBTQ workers could be linked to increased distress while working, was not supported by the results because working from home was experienced as comparatively less tiring and stressful. However, we did not have direct measures of how respondents perceived the work-family border during COVID. Although controlling for marital status and living arrangements had limited impact on the relationship between work location and stress/tiredness levels for LGBTQ workers, these variables only indicate the presence of household members, not how LGBTQ workers experienced the potential for increased visibility of family members to co-workers (e.g., though video conferencing). Thus, we cannot rule out blurred work and family border experiences as a possible factor influencing some LGBTQ workers’ well-being.

It is important to note that the impact of work location on LGBTQ workers' emotional experiences may not be experienced uniformly among sexual and gender minorities. For example, workplace strains may be heightened for LGBTQ individuals who also face racial discrimination in the workplace, as well as those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged or subject to other forms of workplace inequality (e.g., Alfrey and Twine, 2017; Bowleg et al., 2008; Cech and Rothwell 2019). LGBTQ workers' experiences of working at home may also vary depending on who they live with during the pandemic and how accepting parents, roommates, or others in the household are of their identities (Salerno et al., 2021). By conducting a series of triple interactions, we tested how race/ethnicity, gender, age, SES, work characteristics, and living arrangements may moderate the differences between LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers in how work location influences their emotions during paid work. We did not observe significant moderating effects, which may be in part because the sample size of LGBTQ workers working at a workplace was too small and does not have enough statistical power to fully examine moderating effects. However, descriptive statistics using a broad binary race/ethnicity variable (white/non-white) suggest non-white LGBTQ workers experienced particularly high stress levels when working at a workplace (Online Appendix). In other words, working at workplaces (as compared to working from home) is associated with greater stress for all LGBTQ workers, and this pattern appears to be more evident for racialized minority LGBTQ workers than for LGBTQ workers racialized as white. Given that structural and interpersonal racism influences LGBTQ workplace stress (e.g., Bowleg et al., 2008) and emerging evidence suggests racialized groups differ in perceptions of working remotely (Future Forum, 2022), future research should examine how work location may influence LGBTQ workers’ emotional experiences differently across racialized groups.

Another limitation is the relatively small number of LGBTQ respondents. Because of this, we used a broad binary indicator (LGBTQ/non-LGBTQ) that groups together all sexual and/or gender minority individuals (208 lesbian/gay, 521 bisexual, 122 other non-heterosexual sexual identities, 84 gender minority individuals). However, workplace experiences for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and other sexual and gender minorities are often quite distinct (e.g., Sawyer et al., 2016). There are also limitations related to survey measures, including perceived work-family border experiences. Household composition represents an indicator of the possibility of increased visibility of family to coworkers, but cannot capture how that visibility is experienced. In addition, past research on LGBTQ workplace experiences and well-being has found factors like work climate, LGBTQ-inclusive policies, and supportive coworkers all play a role (Webster et al., 2018). Although the survey item on exhaustion when interacting with coworkers provides some information on workplace relationships and climate, it does not fully capture these factors.

Despite limitations, this paper is among the first to explore how experienced well-being during paid work may vary systematically across work locations for LGBTQ and non-LGBTQ workers. Our time diary analysis finds important distinctions in experiences of stress and tiredness while working across work locations, particularly for LGBTQ individuals. These results have both theoretical and practical implications. With regard to studies of minority stress, the findings point to the potential complexity and context-specificity of distal and proximal stress processes. While LGBTQ workers may be exposed to workplace minority stress across all work settings, it is possible that stressors are heightened in particular contexts (e.g., working face-to-face during a pandemic) and buffered in other contexts (e.g., working from home). Future research should continue to consider the role of work location in LGBTQ workplace experiences and well-being. Regarding practical implications, the findings underscore the need for nuance among researchers and policymakers when evaluating the link between work location and well-being, and the importance of considering how minority stress processes influence distinct work experiences. Because workplace supports for LGBTQ workers are linked to better well-being outcomes (Webster et al., 2018), organizations should take steps to address workplace minority stress and protect well-being by fostering inclusive practices and policies across all work settings. Further, in line with past research (Moen et al., 2016), our findings reinforce the importance for well-being of providing workers greater control over the circumstances of paid work (e.g., where and when it occurs) when possible.

Focusing on the experienced well-being of sexual and gender minority individuals during paid work across different settings provides a window into another dimension of the mental health consequences of COVID-19, enabling a deeper understanding of how work location and environment may influence well-being in distinct ways for LGBTQ workers. Because remote work is likely to be a permanent component of many jobs going forward, it is important to more fully understand the link between work location and well-being among sexual and gender minority workers and other marginalized workers in years to come.

Credit author statement

Layne Amerikaner: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. Hope Xu Yan: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Liana C. Sayer: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Long Doan: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Data curation, Funding acquisition. Jessica N. Fish: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Kelsey J. Drotning: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. R. Gordon Rinderknecht: Software, Data curation, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgements

Data collection for the Assessing the Social Consequences of COVID-19 study was funded by the University of Maryland Coronavirus Research Seed Fund and a National Science Foundation RAPID Grant (SES-2029963). Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the 2022 Population Association of America and the 2022 Work and Family Researchers Network conferences. Layne Amerikaner and Hope Xu Yan contributed equally to this paper as first authors.

Handling Editor: Medical Sociology Office

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115850.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

Data availability

At the time of manuscript submission, the dataset is not yet publicly available but will be in the future.

References

- Alfrey Lauren, Twine France Winddance. Gender-fluid geek girls: negotiating inequality regimes in the tech industry. Gend. Soc. 2017;31(1):28–50. [Google Scholar]

- Allen Tammy, Golden Timothy, Shockley Kristen. How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychol. Sci. Publ. Interest. 2015;16(2):40–68. doi: 10.1177/1529100615593273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Amanda, Kaplan Seth, Vega Ronald. The impact of telework on emotional experience: when, and for whom, does telework improve daily affective well-being? Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2014;24(6):882–897. [Google Scholar]

- Badgett, M.V. Lee, Choi, Soon Kyu, Wilson, Bianca, 2019. LGBT poverty in the United States: a study of differences between sexual orientation and gender identity. The Williams Institute. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/National-LGBT-Poverty-Oct-2019.pdf. (Accessed 15 February 2022).

- Baumel Katie, Hamlett Mara, Wheeler Brittany, Hall Deborah, Randall Ashley, Mickelson Kristin. Living through COVID-19: social distancing, computer-mediated communication, and well-being in sexual minority and heterosexual adults. J. Homosex. 2021;68(4):673–691. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2020.1868190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom Nicholas, Davis Steven, Zhestkova Yulia. vol. 111. American Economic Association; 2021. (COVID-19 Shifted Patent Applications toward Technologies that Support Working from Home). [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick Wendy, Boyd Carol, Hughes Tonda, Esteban McCabe Sean. Dimensions of sexual orientation and the prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in the United States. Am. J. Publ. Health. 2010;100(3):468–475. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg Lisa, Brooks Kelly, Ritz Susan Faye. ‘Bringing home more than a paycheck:’ an exploratory analysis of Black lesbians' experiences of stress and coping in the workplace. J. Lesb. Stud. 2008;12(1):69–84. doi: 10.1300/10894160802174342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks Virginia. Lexington Books; Lanham, MD: 1981. Minority Stress and Lesbian Women. [Google Scholar]

- Cech Erin, Rothwell William. LGBT workplace inequality in the federal workforce: intersectional processes, organizational contexts, and turnover considerations. ILR Review. 2019;73(1):25–60. [Google Scholar]

- Cech Erin, Waidzunas Tom. LGBTQ@NASA and beyond: work structure and workplace inequality among LGBTQ STEM professionals. Work Occup. 2022;49(2):187–228. doi: 10.1177/07308884221080938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charalampous Maria, Grant Christine, Tramontano Carlo, Michailidis Evie. Systematically reviewing remote E-workers’ well-being at work: a multidimensional approach. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2018;28(1):51–73. [Google Scholar]

- Chung Heejung, Seo Hyojin, Forbes Sarah, Birkett Holly. University of Kent and University of Birmingham; 2020. Working from Home during the COVID-19 Lockdown: Changing Preferences and the Future of Work.https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-social-sciences/business/research/wirc/epp-working-from-home-COVID-19-lockdown.pdf Retrieved. [Google Scholar]

- Drabble Laurie, Eliason Michele. Introduction to special issue: impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on LGBTQ+ health and well-being. J. Homosex. 2021;68(4):545–559. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2020.1868182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drotning Kelsey, Doan Long, Sayer Liana, Fish Jessica, Rinderknecht R. Gordon. Not all homes are safe: family violence following the onset of the covid-19 pandemic. J. Fam. Violence. 2022;38(2):189–201. doi: 10.1007/s10896-022-00372-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English, Devin, Rendina H. Jonathon, Parsons Jeffrey. The effects of intersecting stigma: a longitudinal examination of minority stress, mental health, and substance use among Black, Latino, and multiracial gay and bisexual men. Psychol. Violence. 2018;8(6):669–679. doi: 10.1037/vio0000218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Wen, Moen Phyllis. University of Minnesota Life Course Center Working Paper; 2022. COVID-19 and the Uneven Stress of Social Change: Remote Work and Subjective Well-Being. [Google Scholar]

- Fish Jessica, Salerno John, Williams Natasha, Rinderknecht R. Gordon, Sayer Liana, Doan Long. Sexual minority disparities in health and well-being as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic differ by sexual identity. LGBT Health. 2021;8(4):263–272. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2020.0489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flèche Sarah, Smith Conal. Time use surveys and experienced well-being in France and the United States. OECD Statistics Working Papers. 2017 No. 2017/07. [Google Scholar]

- Galanti Teresa, Guidetti Gloria, Mazzei Elisabetta, Zappalà Salvatore, Toscano Ferdinando. Work from home during the COVID-19 outbreak: the impact on employees' remote work productivity, engagement, and stress. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021;63(7):e432. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galupo M. Paz, Resnick Courtney. In: In Sexual Orientation And Transgender Issues In Organizations: Global Perspectives On LGBT Workforce Diversity. Köllen T., editor. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2016. Experiences of LGBT microaggressions in the workplace: implications for policy; pp. 271–287. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg Emma. 2022. After Two Years of Remote Work, Workers Question Office Life. New York Times.https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/10/business/remote-work-office-life.html Retrieved March 28, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg Abbie, Smith Julianna. Work conditions and mental health in lesbian and gay dual-earner parents. Fam. Relat. 2013;62(5):727–740. [Google Scholar]

- Grant Jamie, Mottet Lisa, Tanis Justin, Harrison Jack, Herman Jody, Keisling Mara. 2011. Injustice at Every Turn: the Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay And Lesbian Task Force. [Google Scholar]

- Future Forum, 2022. Future Forum Pulse. Retrieved https://futureforum.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Future-Forum-Pulse-Report-January-2022.pdf. (Accessed 28 March 2022).

- Grusky, David, Carpenter, Ann, Graves, Erin, Kallschmidt, Anna, Mitnik, Pablo, Nichols, Bethany, Snipp, C. Matthew, 2021. The rise of the noxious contract: job safety in the Covid-19 crisis. Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality Retrieved https://inequality.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/research/articles/covid-noxious-contract.pdf. (Accessed 8 February 2022).

- Hart Chloe Grace. Trajectory guarding: managing unwanted, ambiguously sexual interactions at work. Am. Socio. Rev. 2021;86(2):256–278. [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield Adia Harvey, Wingfield John Harvey. When visibility hurts and helps: how intersections of race and gender shape Black professional men's experiences with tokenization. Cult. Divers Ethnic Minor. Psychol. 2014;20(4):483–490. doi: 10.1037/a0035761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler Mark, Link Bruce. Introduction to the special issue on structural stigma and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014;103:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman Elizabeth Grace. Theoretical extensions of minority stress theory for sexual minority individuals in the workplace: a cross-contextual understanding of minority stress processes. J. Family Theory Rev. 2018;10(1):165–180. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman Daniel, Krueger Alan, Schkade David, Schwarz Norbert, Stone Arthur. A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: the day reconstruction method. Science. 2004;306(5702):1776–1780. doi: 10.1126/science.1103572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg Arne. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 2011. Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: the Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s-2000s. [Google Scholar]

- Kapteyn Arie, Lee Jinkook, Tassot Caroline, Vonkova Hana, Zamarro Gema. Dimensions of subjective well-being. Soc. Indicat. Res. 2015;123(3):625–660. doi: 10.1007/s11205-014-0753-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasek Robert. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979;24(2):285–308. [Google Scholar]

- Kniffin Kevin, Narayanan Jayanth, et al. COVID-19 and the workplace: implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. Am. Psychol. 2021;76(1):63–77. doi: 10.1037/amp0000716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger Alan, Kahneman Daniel, Fischler Claude, Schkade David, Schwarz Norbert, Stone Arthur. Time use and subjective well-being in France and the U.S. Soc. Indicat. Res. 2009;93(1):7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Yoonjoo, Hofferth Sandra, Flood Sarah, Fisher Kimberly. Reliability, validity, and variability of the subjective well-being questions in the 2010 American Time Use Survey. Soc. Indicat. Res. 2016;126(3):1355–1373. doi: 10.1007/s11205-015-0923-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyttelton Thomas, Zang Emma, Musick Kelly. Telecommuting and gender inequalities in parents’ paid and unpaid work before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Marriage Fam. 2022;84(1):230–249. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning Wendy, Kamp Dush Claire. vol. 8. 2022. (COVID-19 Stress and Sexual Identities.” Socius: Sociological Research For a Dynamic World). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maslach Christina, Leiter Michael. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1997. The Truth about Burnout. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach Christina, Schaufeli Wilmar, Leiter Michael. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001;52:397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes Cindy, Pereira Henrique. Assessing the impact of COVID-19 on work-related quality of life through the lens of sexual orientation. Behav. Sci. 2021;11(5):58. doi: 10.3390/bs11050058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer Ilan. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer Ilan, Schwartz Sharon, Frost David. Social patterning of stress and coping: does disadvantaged social statuses confer more stress and fewer coping resources? Soc. Sci. Med. 2008;67(3):368–379. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell Kimberly, Ybarra Michele, Banyard Victoria, Goodman Kimberly, Jones Lisa. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on perceptions of health and well-being among sexual and gender minority adolescents and emerging adults. LGBT Health. 2022;9(1):34–42. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2021.0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen Phyllis, Kelly Erin, Fan Wen, Lee Shi-Rong, Almeida David, Ernst Kossek Ellen, Buxton Orfeu. Does a flexibility/support organizational initiative improve high-tech employees’ well-being? Evidence from the work, family, and health Network. Am. Socio. Rev. 2016;81(1):134–164. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council . In: Subjective Well-Being: Measuring Happiness, Suffering, and Other Dimensions of Experience. Stone A.A., Mackie C., editors. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker Kim, Menasce Horowitz Juliana, Minkin Rachel. Pew Research Center; 2020. How Coronavirus Has – and Hasn't – Changed the Way Americans Work.https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/12/09/how-the-coronavirus-outbreak-has-and-hasnt-changed-the-way-americans-work/#fn-29356-2 Retrieved. [Google Scholar]

- Peer Eyal, Brandimarte Laura, Samat Sonam, Acquisti Alessandro. Beyond the Turk: alternative platforms for crowdsourcing behavioral research. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2017;70:153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Ragins Belle Rose, Cornwell John. Pink triangles: antecedents and consequences of perceived workplace discrimination against gay and lesbian employees. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001;86(6):1244–1261. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.86.6.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragins Belle Rose, Cornwell John, Miller Janice. Heterosexism in the workplace: do race and gender matter? Group Organ. Manag. 2003;28(1):45–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ragins Belle Rose, Singh Romila, Cornwell John. Making the invisible visible: fear and disclosure of sexual orientation at work. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007;92(4):1103–1118. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinderknecht R. Gordon, Doan Long, Sayer Liana. MyTimeUse: an online implementation of the day-reconstruction method. J. Time Use Res. 2022;(1):23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Salerno John, Williams Natasha, Gattamorta Karina. LGBTQ populations: psychologically vulnerable communities in the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020;12(S1):S239–S242. doi: 10.1037/tra0000837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salerno John, Doan Long, Sayer Liana, Kelsey Drotning, Rinderknecht R. Gordon, Fish Jessica. Changes in mental health and well-being are associated with living arrangements with parents during COVID-19 among sexual minority young persons in the U.S. Psychol. Sexual Orient. Gender Div. 2021 doi: 10.1037/sgd0000520. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer Katina, Thoroughgood Christian, Webster Jennica. In: 21–42 in Sexual Orientation And Transgender Issues In Organizations: Global Perspectives On LGBT Workforce Diversity. Köllen T., editor. Springer International Publishing; Cham: 2016. Queering the gender binary: understanding transgender workplace experiences. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer Katina, Thoroughgood Christian, Ladge Jamie. Invisible families, invisible conflicts: examining the added layer of work-family conflict for employees with LGB families. J. Vocat. Behav. 2017;103:23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider Daniel, Harknett Kristen. Consequences of routine work-schedule instability for worker health and well-being. Am. Socio. Rev. 2019;84(1):82–114. doi: 10.1177/0003122418823184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears Brad, Mallory Christy. Williams Institute; 2011. Documented Evidence of Employment Discrimination & its Effects on LGBT People.https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/employ-discrim-effect-lgbt-people/ Retrieved. [Google Scholar]

- Song Younghwan, Gao Jia. Does telework stress employees out? A study on working at home and subjective well-being for wage/salary workers. J. Happiness Stud. 2020;21(7):2649–2668. [Google Scholar]

- Stone Arthur, Schwartz Joseph, Schkade David, Schwarz Norbert, Krueger Alan, Kahneman Daniel. A population approach to the study of emotion: diurnal rhythms of a working day examined with the day reconstruction method. Emotion. 2006;6(1):139–149. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.6.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilcsik András, Anteby Michel, Knight Carly. Concealable stigma and occupational segregation: toward a theory of gay and lesbian occupations. Adm. Sci. Q. 2015;60(3):446–481. [Google Scholar]

- Velez Brandon, Moradi Bonnie, Brewster Melanie. Testing the tenets of minority stress theory in workplace contexts. J. Counsel. Psychol. 2013;60(4):532–542. doi: 10.1037/a0033346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster Jennica, Adams Gary, Maranto Cheryl, Sawyer Katina, Thoroughgood Christian. Workplace contextual supports for LGBT employees: a review, meta-analysis, and agenda for future research. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018;57(1):193–210. [Google Scholar]

- White Hughto Jaclyn, Reisner Sari, Pachankis John. Transgender stigma and health: a critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015;147:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington Charlie, Hadfield Katalina, Calderón Carina. The lives and livelihoods of many in the LGBTQ community are at risk amidst COVID-19 crisis. Human Rights Campaign. 2020 https://www.hrc.org/resources/the-lives-and-livelihoods-of-many-in-the-lgbtq-community-are-at-risk-amidst-covid-19-crisis Retrieved. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Yijing, Becerik-Gerber Burcin, Lucas Gale, Roll Shawn. Impacts of working from home during COVID-19 pandemic on physical and mental well-being of Office workstation users. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021;63(3):181–190. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

At the time of manuscript submission, the dataset is not yet publicly available but will be in the future.