Abstract

Adolescent sexual and reproductive health (ASRH) in East Africa has prioritized research on the barriers to care, communication, and ASRH knowledge, attitudes, and practices. However, there is little research examining the extent to which meaningful adolescent engagement in research is achieved in practice and how this influences the evidence available to inform ASRH services. This review offers a critical step towards understanding current approaches to adolescent engagement in ASRH research and identifying opportunities to build a strengthened evidence base with adolescent voices at the centre. This scoping review is based on Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) framework, employing a keyword search of four databases via OVID: Medline, Global Health, Embase and PsycINFO. Two reviewers screened title, abstract and full text to select articles examining ASRH in Tanzania, Rwanda, Kenya, and Uganda, published between 2000 and 2020. After articles were selected, data was extracted, synthesized, and thematically organized to highlight emerging themes and potential opportunities for further research. The search yielded 1201 results, 34 of which were included in the final review. Results highlight the methods used to gather adolescent perspectives of ASRH (qualitative), the content of those perspectives (knowledge, sources of information, gaps in information and adolescent friendly services), and the overall narratives that frame discussions of ASRH (risky sexual behaviour, stigma, and gender norms). Findings indicate the extent of adolescent engagement in ASRH research is limited, resulting in a lack of comprehensive evidence, consistent challenges with stigma, little information on holistic concepts and a narrow framing of ASRH. In conclusion, there is opportunity for more meaningful engagement of adolescents in ASRH research. This engagement can be achieved by involving adolescents more comprehensively throughout the research cycle and by expanding the range of ASRH topics explored, as identified by adolescents.

Introduction

Adolescents make up over half of the world’s population and represent the largest generation in history [1,2]. Defined by the United Nations (UN), as young people aged 10 to 19 years old, adolescence is a key time influencing the trajectory of individual and community health outcomes [1,2]. Of particular interest are adolescent sexual and reproductive health (ASRH) outcomes, as adolescents start engaging in sexual behaviour around the age of 15 years [1,3]. Sexual and reproductive health (SRH) is defined as “a wide range of health issues including family planning; maternal and newborn health care; prevention, diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) … [with] services [aiming to prevent] poor SRH, such as … unintended pregnancies, unsafe abortions, [and] complications caused by STIs” [4,5]. Improving SRH outcomes aligns with Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 3.7 and 5.6, which aim to ensure universal access to SRH services and rights [4,5].

In Sub-Saharan Africa, which includes East African countries such as Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, progress on achieving SDG targets remains slow, resulting in a continuing burden of STIs, unmet contraceptive needs, and inadequate quality of SRH care among adolescents [4,6–13]. As such, the focus of health-specific literature in East Africa has been on SRH interventions, barriers to care amongst adolescents, parent and community communication on SRH, and knowledge, attitudes and practices [6,9,14–28]. This slow progress has been attributed to the complexity of defining ASRH priorities and inadequate research evidence to support relevant policy and program decisions [4,12,29]. Increasing adolescent involvement in research about ASRH has been suggested as a way to build a more responsive and relevant evidence base [2,29–32]. Adolescent participation can contribute to defining ASRH services, polices, and programs that better reflect adolescents needs [2,29–32].

There is little research examining the extent to which meaningful adolescent engagement in ASRH research is achieved in practice and how this influences the evidence generated to inform ASRH programming, education, policies and services [2,29–31]. This review offers a critical step towards understanding current approaches to adolescent engagement in SRH research and identifying opportunities to build a strengthened evidence base with adolescent voices at the centre.

The purpose of this paper is to examine adolescent engagement in ASRH research in four East African countries, Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda. These four countries were selected based on the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee data on Aid to Health, which highlights that the largest investments in reproductive health in the East African Community (EAC) are flowing to Tanzania, Uganda, South Sudan, Kenya and Rwanda [33]. However, South Sudan was not included in this analysis given its unstable context and heavy investment in the humanitarian rather than development sector over the last 15 years. In this paper, we will examine, (i) the methods used to gather adolescent perspectives of SRH, (ii) the content of those perspectives and, (iii) the narratives framing discussions of ASRH. The review was guided by the following question: How are adolescents engaged in research on ASRH and what are the perspectives about ASRH in Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda?

Methods

This scoping review aimed to map the existing literature on ASRH in Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda, to consider how adolescents have been engaged in research and the related perspectives about ASRH. A scoping review allows for iterative “mapping” of existing literature towards identifying gaps for future research [34–36]. Our approach was informed by Arksey and O’Malley’s (33) scoping review framework and the PRISMA-ScR Checklist by Tricco et al. (S1 Checklist) (35). We followed a five-stage process involving, 1) identifying the research question, 2) identifying relevant studies, 3) selecting studies, 4) charting the data, and 5) collating, summarizing and reporting results [34].

Identifying relevant studies

We searched four databases through OVID: Medline, Global Health, Embase and PsycINFO. The search strategy involved the keywords “sexual health” or “reproductive health” or “sexual and reproductive health” AND Adolescent* or teen* or youth AND “East Africa” or Tanzania or Rwanda or Uganda or Kenya (S1 Text). The review included peer-reviewed articles written between 2000 and 2020. All searches are current to February 2021.

The inclusion criteria were studies that, 1) focused on adolescents (aged 10–18, pre-university); 2) were conducted in Tanzania, Rwanda, Uganda, or Kenya; 3) discussed the concept of SRH and specifically adolescent perspectives on, from and of SRH; and, 4) were written in English and published between 2000–2020 to capture the current literature on SRH along with historical perspectives.

The exclusion criteria were, 1) literature on interventions or prevalence of SRH that did not provide adolescent perspectives on, from and of SRH; 2) grey literature; 3) studies that were implemented in countries in East Africa outside of Tanzania, Rwanda, Uganda, and Kenya; and, 4) literature that focused on “last mile populations” or niche communities (i.e., refugees). We did not exclude studies based on study design.

Selecting studies

Two reviewers completed the title, abstract screening, and full text review through Covidence, an online reviewing platform. If there was disagreement on inclusion, reviewers discussed until consensus. The primary author subsequently completed an additional full text review for comprehension.

Charting the data

Information from selected studies was collated and summarized using the data extraction framework (Table 1).

Table 1. Data extraction framework.

| Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Author | Where is the main author(s) from? Is the lead author from an African or non-African based institution? |

| Title | What is the title? |

| Journal & type of publication | Indicate both the journal and type of publication (i.e. peer reviewed article etc.) |

| Year of publication | What is the year of publication? |

| Aim/objectives of paper | Describe aim/objective of study |

| Overview of study | Country of study focus, type of study, intervention examining (if applicable), thematic focus area (identify the problem being studied), main objective/aim of study |

| Study design and methods | Type of study, methodology, approach, data collection tools, analysis, outcome measures Whose perspectives were included, discussed, and gathered in study? What do those perspectives involve? Were adolescents involved in development of research, collection of data/analysis, used as member checkers? |

| Overview of results/conclusions | Reported outcomes, summary of key findings, highlight conclusion |

| Limitations | Describe study limitations |

Results

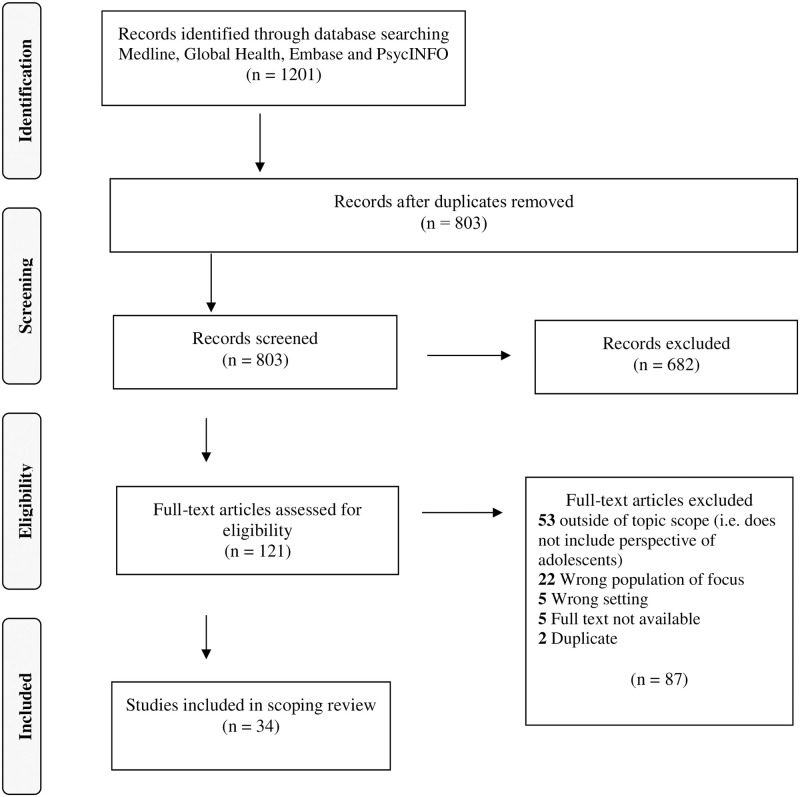

The search yielded 1201 results. Out of those results, 398 were excluded as duplicates and 803 articles were screened (title and abstract). Subsequently, 121 texts were reviewed fully and 34 were included in the final review (see Fig 1, S1 Data). Of these studies, 11 were conducted in Uganda [6,14,26,37–44], 12 in Tanzania [22,27,45–54], eight in Kenya [8,55–61], and three in Rwanda [10,11,62]. The results were summarized to highlight the methods used to gather adolescent perspectives of SRH, the content of those perspectives, and the narratives that frame discussions of ASRH.

Fig 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Methods used to gather perspectives

Almost 62% of articles implemented a qualitative study design and used in-depth interviews and focus groups to collect data. Quantitative study designs accounted for 26%, mixed methods for 6% and participatory approaches for almost 6%. Adolescents were included primarily as study participants and were the only participants in 25 articles [6,8,10,11,22,26,27,38,39,42–44,46–49,51,53,55,56,58,60]. In eight articles, adolescents were involved as participants alongside community members, teachers, caregivers, religious leaders, and healthcare providers [14,40,45,50,52,54,57,59,62]. One study captured adolescent perspectives without directly involving adolescents [41]. None of the articles indicated that adolescents had contributed to developing the research design or contributed to the analysis of data (i.e., member checkers, verifying data analysis, etc.).

Content of perspectives

The content of adolescent perspectives of SRH can be specified as knowledge, sources of information, gaps in information, and adolescent friendly services.

Knowledge

Thirteen articles examined ASRH knowledge, including concepts such as family planning, contraceptives (i.e., condoms), STIs, puberty and, abstinence [8,10,11,22,26,37,39,40,42–45,50,51]. Most of these articles quantitatively measured level of SRH knowledge among adolescents and how knowledge translates into behaviour. Based on the findings, a high level of SRH knowledge did not translate into safer sexual behaviour or genuine understanding of SRH [40,44,45,55,58].

Sources of information

Six articles identified the primary sources of SRH information among adolescents as peers, radio, and parents, with some mentioning health centres [8,14,22,39,47,50]. Radio was identified as the most common source of information due to mass media campaigns, accessibility and convenience [22,47]. Adolescents indicated that parents were a valued and desired source of information even though many parents assumed ASRH was immoral and were hesitant to discuss the topic [14,41,43,45,50,54,59]. Due to this hesitation from parents, adolescents indicated that peers provide a significant amount of SRH information [8,14]. Although health centres were cited as a source of information, the limited confidentiality, lack of adolescent-specific information, and low trust in the care provided, deterred adolescents from seeking SRH information at health centres [22,52,59].

Gaps in information

Adolescents reported misconceptions about aspects of SRH such as contraceptives [38,39,42,43,49,56,60,62]. For example, a number of articles indicated that adolescents believed contraceptives, abortion and family planning were linked to infertility and cancer due to information shared by parents and communities, and due to fear regarding side effects from biomedical treatment [8,22,38,42,43,56,58,60]. The fear of infertility is connected to the high value placed on having children in East Africa [43,53]. Literature noted that adolescents are constrained by cultural and gender norms which equate having children with status and value, creating pressure to prove their fertility, especially among young women [43]. Two articles discussed adolescents wanting to know about diversity in sexual behavior (i.e., curiosity about sex rather than just sexual health) [10,49].

Adolescent friendly services

Seven articles discussed adolescent friendly services [6,8,40,41,50,52,59]. These were defined as non-judgmental, private spaces in which care is free and health practitioners are trained on specific ASRH needs [6,8,50]. Tanzania, Rwanda, Kenya, and Uganda have all focused on providing adolescent friendly services at existing health clinics to increase the access adolescents have to SRH information and care. However, access is limited due to barriers such as confidentiality and limited knowledge of adolescent-specific SRH (6,8,52,55,56,59). Three articles noted the need to shift towards more adolescent involved development of services to address misconceptions and mistrust in existing services [6,8,50].

Narratives framing discussions of ASRH

Narratives framing discussions of ASRH in the literature were consistent over the 20-year period of the review and included risky behavior, stigma, and gender norms. Twelve articles discussed risky sexual behaviour, that is, adolescents engaging in sexual relations, such as sex without a condom and having multiple sexual partners, leading to negative outcomes (e.g., STIs, unwanted pregnancy) [8,11,43–45,50,52–55,58,61]. Transactional sex and a mistrust in condoms were also noted as risky sexual behaviour [43,44,52–54,61]. Sex for pleasure was considered deviant or risky behaviour among adolescents in Rwanda, where abstinence was framed as “good” sexual behaviour [10].

Some articles noted that high levels of SRH knowledge do not translate into decreased risky sexual behaviour [44,45,55,58]. Other articles highlighted how social and environmental factors such as experiences of poverty, unequal gender norms, substance abuse, and lack of parental support correlate with increased risky sexual behaviour [6,8,10,11,50,54].

Stigma, a social determinant of health specifying what is acceptable or deviant SRH behaviour based on assumptions and stereotypes (i.e., religious beliefs and assumptions of sexual “promiscuity”), was discussed in 11 articles, particularly from healthcare providers, communities and parents [38,40,42,43,46,52,53,56–58,61]. Stigma towards sex outside of marriage, use of contraceptives (especially condoms), early or unintended pregnancy, and abortion were discussed as leading to shaming, social isolation and negative name calling [8,38,42,43,52–54,56,61]. Stigma towards contraceptive use was based on the assumption that contraceptives are only for people who are married or have children, and if used otherwise, result in infertility or increased risky sexual behaviour [8,38,42,43,52,56].

Nine articles discussed how gender norms limit the ability of young women to access SRH care and/or engage in safe sexual behavior (e.g., condom use) [8,10,38,42–44,50,53,55]. This included reference to patriarchal gender norms that prioritize men over women resulting in power imbalances and decreased decision making capacity of women, while reinforcing assumptions that young women are sexually promiscuous [10,38,50].

Discussion

With such a significant population of adolescents in the world and adolescence being a key time of growth and challenge, especially in regards to SRH, it is important to identify how adolescents have been engaged in SRH research in Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda. Findings indicate the extent of adolescent engagement is limited, resulting in a lack of comprehensive evidence, consistent challenges with stigma, little information on holistic concepts, and a narrow framing of ASRH.

In the studies reviewed, adolescents were involved as study participants but not in the development or analysis of research projects. Limited engagement through top down, generalized research and programming fails to recognize the intersectional, diverse and context-specific SRH experiences of adolescents in East African countries [2,29,30,63–65]. The value of involving adolescents in SRH research, education and programming development is established [2,29,31,32,50,66–69]. The WHO has called for participatory engagement of adolescents, supporting programs and policies that are “partnership-driven, evidence-informed, gender-responsive, human rights-based, sustainable, people-centered, [and] community-owned” [32]. Participatory action research and community-based participatory research methods have been shown to effectively engage research participants more comprehensively throughout the process of research, resulting in more equitable, context-specific research information and action [30,70–72]. In particular, methods such as photovoice, meaningfully engage adolescents leading to greater peer support, knowledge and insight to inform future SRH education and programming [30,73–75]. It is essential to further engage East African adolescents in SRH research, education and program development in order to create more effective ASRH programs [29,30].

Stigma related to ASRH was noted as a significant challenge for adolescents and stakeholders in the studies reviewed. Stigma from healthcare providers, community leaders and parents towards contraceptive use ultimately limits the perceived and experienced access adolescents have to adolescent friendly services and SRH information [38,43,52,56,61]. Research on how to reduce stigma towards ASRH has showed that open dialogue and communication with all community stakeholder groups, including adolescents, has been effective [43,52]. Based on learning from HIV experiences, it is possible to address stigma in healthcare facilities by engaging in participatory dialogue and action planning with stakeholder groups [52,76]. A recent study in Burundi also recommended engaging religious leaders, confronting gender-based power imbalances and exploring the underlying drivers of health practitioner stigma as norm-shifting interventions [77]. Engaging adolescents and stakeholders in participatory action research focused on stigma reduction can help to address this pernicious barrier to improve ASRH outcomes [2,10,29,45,50,67,78].

The concepts identified in the literature on Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda echo the concepts identified in the global SRH literature over the last 20 years, including family planning, contraceptives, STIs, puberty and abstinence [1,2,8,10,11,22,26,37,39,40,42–45,50,51]. Although important, these SRH concepts do not address a wider scope of ASRH perspectives that include sexual desires, masturbation, and sex for pleasure [10,49,79]. These topics have been included in “Comprehensive sexuality education” (CSE) programs implemented in some Sub-Saharan African countries after the 1994 Conference on Population and Development [80]. In East Africa, however, topics such as masturbation, abortion and sexual orientation directly contradict religious beliefs and traditions such as premarital sexual abstinence and patriarchal gender norms resulting in resistance from communities to include such topics in sex education [80,81]. Research has demonstrated that capturing a wider scope of SRH perspectives among adolescents is important to inform more effective, inclusive and adolescent context-specific research, programming and education [49].

The studies reviewed framed adolescent perspectives of SRH within assumptions of risky behaviour [8,11,43–45,50,52–55,58,61,66,67]. This narrow framing of adolescence as an inherently risky time in an individual’s life does not recognize the intersectional experience of adolescents, ultimately limiting how societies support them [29,66,67]. Adolescence is a key time in which intersecting experiences of race, class, gender, and age impact the health of young people. An intersectional lens to ASRH recognizes the social, political and economic power structures that shape individual interactions and health experiences [82]. For example, economic vulnerability and unequal gender norms in East Africa result in transactional sex and limits agency among young women to access SRH services [8,10,38,42–44,50,53–55,82]. Recognizing the intersecting experiences specific to adolescence, rather than framing adolescence as inherently risky, invites an intersectional reframing of adolescence as a time of capacity building and growth towards increased engagement in SRH [2,10,29,45,50,67,78], leading to more targeted, effective ASRH research, programming and education [82].

This study had several limitations. First, literature was only included if written in English, limiting the diversity of perspectives captured. However, the majority of the literature involved authors from institutions based in East Africa in collaboration with institutions from the United States or Europe. Second, literature was only included if available through university accessible databases. However, the databases provided a wide scope of journals and articles. Finally, the data extraction and analysis of literature was completed only by the primary author (HC). Although we recognize that best practice involves multiple reviewers, the input from contributing authors on conceptualization (LB, HC, PO, DD), data collection (PO, HC), and drafting and editing (HC, DD, AB) added to the rigour of ideas shared.

Conclusion

This scoping review has explored how adolescents have been engaged in SRH research in Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, and Uganda by identifying the methods used to gather adolescent perspectives of SRH, content of those perspectives and narratives framing discussions of ASRH. Findings suggest that there is opportunity for more meaningful engagement of adolescents in ASRH research and exploration of more diverse framings and concepts concerning ASRH, as identified by adolescents. Future research should explore how East African countries engage adolescents in the development of ASRH programming.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

A text file of the search strategy we used in this scoping review.

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lisa Schwartz for her support in the final stages of drafting the manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Bearinger LH, Sieving RE, Ferguson J, Sharma V. Global perspectives on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents: patterns, prevention, and potential. Lancet. 2007;369(9568):1220–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60367-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patton GC, Sawyer SM, Santelli JS, Ross DA, Afifi R, Allen NB, et al. Our future: a Lancet commission on adolescent health and wellbeing. Lancet. 2016;387(10036):2423–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00579-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hindin MJ, Fatusi AO. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in developing countries: An overview of trends and interventions. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2009;35(2):58–62. doi: 10.1363/ipsrh.35.058.09 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ouedraogo L, Nkurunziza T, Muriithi A, John TK, Asmani C, Elamin H, et al. The WHO African Region: Research Priorities on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights. Adv Reprod Sci. 2021;09(01):13–23. doi: 10.4236/arsci.2021.91002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO Regional Office for Europe. Fact sheets on sustainable development goals: health targets—Sexual and Reproductive Health [Internet]. 2017. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/348008/Fact-sheet-SDG-SRH-FINAL-04-09-2017.pdf.

- 6.Atuyambe LM, Kibira SPS, Bukenya J, Muhumuza C, Apolot RR, Mulogo E. Understanding sexual and reproductive health needs of adolescents: Evidence from a formative evaluation in Wakiso district, Uganda Adolescent Health. Reprod Health. 2015;12(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0026-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bylund S, Målqvist M, Peter N, Herzig van Wees S. Negotiating social norms, the legacy of vertical health initiatives and contradicting health policies: a qualitative study of health professionals’ perceptions and attitudes of providing adolescent sexual and reproductive health care in Arusha and Kiliman. Glob Health Action. 2020;13(1). doi: 10.1080/16549716.2020.1775992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Godia PM, Olenja JM, Hofman JJ, Van Den Broek N. Young people’s perception of sexual and reproductive health services in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1). doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hokororo A, Kihunrwa AF, Kalluvya S, Changalucha J, Fitzgerald DW, Downs JA. Barriers to access reproductive health care for pregnant adolescent girls: A qualitative study in Tanzania. Acta Paediatr Int J Paediatr. 2015;104(12):1291–7. doi: 10.1111/apa.12886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michielsen K, Remes P, Rugabo J, Van Rossem R, Temmerman M. Rwandan young people’s perceptions on sexuality and relationships: Results from a qualitative study using the ‘mailbox technique’. Sahara J. 2014;11(1):51–60. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2014.927950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nkurunziza A, Van Endert N, Bagirisano J, Hitayezu JB, Dewaele S, Tengera O, et al. Breaking barriers in the prevention of adolescent pregnancies for in-school children in Kirehe district (Rwanda): A mixed-method study for the development of a peer education program on sexual and reproductive health. Reprod Health. 2020;17(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12978-020-00986-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Sexual and Reproductive Health Fact Sheet [Internet]. 2020. https://www.afro.who.int/publications/sexual-and-reproductive-health-fact-sheet.

- 13.Woog V, Singh S, Browne A, Philbin J. Adolescent Women’s Need for and Use of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in Developing Countries [Internet]. Guttmacher Institute. 2015. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/adolescent-womens-need-and-use-sexual-and-reproductive-health-services-developing-countries.

- 14.Muhwezi WW, Katahoire AR, Banura C, Mugooda H, Kwesiga D, Bastien S, et al. Perceptions and experiences of adolescents, parents and school administrators regarding adolescent-parent communication on sexual and reproductive health issues in urban and rural Uganda Adolescent Health. Reprod Health. 2015;12(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12978-015-0099-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muthengi E, Ferede A, Erulkar A. Parent-child communication and reproductive health behaviors: A survey of adolescent girls in rural Tanzania. Etude la Popul Africaine. 2015;29(2):1887–900. doi: 10.11564/29-2-772 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nalwadda G, Mirembe F, Tumwesigye NM, Byamugisha J, Faxelid E. Constraints and prospects for contraceptive service provision to young people in Uganda: Providers’ perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nkata H, Teixeira R, Barros H. A scoping review on sexual and reproductive health behaviors among Tanzanian adolescents. Public Health Rev. 2019;40(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s40985-019-0114-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seif SA, Kohi TW, Moshiro CS. Sexual and reproductive health communication intervention for caretakers of adolescents: A quasi-experimental study in Unguja- Zanzibar. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0756-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wanje GH, Masese L, Avuvika E, Omoni G, Baghazal A, McClelland RS. P03.26 Parents’ and teachers’ views on adolescents’ sexual health to inform the development of a screening intervention for sexually transmitted infections: a qualitative study. Sex Transm Infect [Internet]. 2015. Sep 1;91(Suppl 2). doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052270.254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warenius LU, Faxelid EA, Chishimba PN, Musandu JO, Ong’any AA, Nissen EB-M. Nurse-Midwives’ Attitudes towards Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Needs in Kenya and Zambia. Reprod Health Matters. 2006;14(27). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aiko T, Horiuchi S, Shimpuku Y, Madeni F, Leshabari S. Overcoming barriers to inclusive education: A reproductive health awareness programme for adolescents in rural Tanzania. Afr J Midwifery Womens Health. 2016;10(1):27–32. doi: 10.12968/ajmw.2016.10.1.27 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dangat CM, Njau B. Knowledge, attitude and practices on family planning services among adolescents in secondary schools in Hai district, northern Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2013;15(1):1–8. doi: 10.4314/thrb.v15i1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kajula LJ, Sheon N, De Vries H, Kaaya SF, Aarø LE. Dynamics of parent-adolescent Communication on sexual health and HIV/AIDS in Tanzania. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(SUPPL. 1):69–74. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0634-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kajula LJ, Darling N, Kaaya SF, De Vries H. Parenting practices and styles associated with adolescent sexual health in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. AIDS Care—Psychol Socio-Medical Asp AIDS/HIV. 2016;28(11):1467–72. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2016.1191598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdallah AK, Magata RJ, Sylvester JN. Barriers to parent-child communication on sexual and reproductive health issues in East Africa: A review of qualitative research in four countries. J African Stud Dev. 2017;9(4):45–50. doi: 10.5897/jasd2016.0410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kemigisha E, Bruce K, Ivanova O, Leye E, Coene G, Ruzaaza GN, et al. Evaluation of a school based comprehensive sexuality education program among very young adolescents in rural Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7805-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madeni F, Horiuchi S, Iida M. Evaluation of a reproductive health awareness program for adolescence in urban Tanzania-A quasi-experimental pre-test post-test research. Reprod Health. 2011;8(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mbeba RM, Mkuye MS, Magembe GE, Yotham WL, Mellah AO, Mkuwa SB. Barriers to sexual reproductive health services and rights among young people in Mtwara district, Tanzania: a qualitative study. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;13 Suppl 1(Supp 1):13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chandra-Mouli V, Svanemyr J, Amin A, Fogstad H, Say L, Girard F, et al. Twenty years after international conference on population and development: Where are we with adolescent sexual and reproductive health and rights? J Adolesc Heal. 2015;56(1):S1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villa-Torres L, Svanemyr J. Ensuring youth’s right to participation and promotion of youth leadership in the development of sexual and reproductive health policies and programs. J Adolesc Heal. 2015;56(1):S51–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wigle J, Paul S, Birn AE, Gladstone B, Braitstein P. Youth participation in sexual and reproductive health: policy, practice, and progress in Malawi. Int J Public Health. 2020;65(4):379–89. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01357-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (2016–2030). 2015. https://www.who.int/life-course/partners/global-strategy/globalstrategyreport2016-2030-lowres.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.OECD. International Development Statistics—Aid to Health. 2019. https://stats.oecd.org/qwids/#?x=2&y=3&f=1:1,4:1,7:1,9:85,5:4,8:85,6:2019&q=1:1+4:1+7:1+9:85+5:4+8:85+6:2020,2019,2018,2017,2016+2:262,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,189,25,27,28,31,29,30,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,89,40,49,50,51,53,54,55,56,57,166,59,273,62,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,78,79,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,90,274,91,92,93,95,96,97,98,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,63,130,131,132,133,135,136,137,138,139,141,144,159,160,161,162,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,154,155,156,157,275,158,163,164,165,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,190,134,191,192,193+3:21,22,23,24,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,35,36,37,38,39&lock=CRS1.

- 34.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peters MDJ, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolf HT, Teich HG, Halpern-Felsher BL, Murphy RJ, Anandaraja N, Stone J, et al. The effectiveness of an adolescent reproductive health education intervention in Uganda. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2015;2015(2). doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2015-0032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cleeve A, Faxelid E, Nalwadda G, Klingberg-Allvin M. Abortion as agentive action: reproductive agency among young women seeking post-abortion care in Uganda. Cult Heal Sex. 2017;19(11):1286–300. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2017.1310297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kemigisha E, Bruce K, Nyakato VN, Ruzaaza GN, Ninsiima AB, Mlahagwa W, et al. Sexual health of very young adolescents in South Western Uganda: A cross-sectional assessment of sexual knowledge and behavior. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12978-018-0595-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kiapi-Iwa L, Hart GJ. The sexual and reproductive health of young people in Adjumani district, Uganda: Qualitative study of the role of formal, informal and traditional health providers. AIDS Care—Psychol Socio-Medical Asp AIDS/HIV. 2004;16(3):339–47. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001665349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kipp W, Chacko S, Laing L, Kabagambe G. Adolescent reproductive health in Uganda: Issues related to access and quality of care. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2007;19(4):383–93. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2007.19.4.383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maly C, McClendon KA, Baumgartner JN, Nakyanjo N, Ddaaki WG, Serwadda D, et al. Perceptions of Adolescent Pregnancy Among Teenage Girls in Rakai, Uganda. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2017;4. doi: 10.1177/2333393617720555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nalwadda G, Mirembe F, Byamugisha J, Faxelid E. Persistent high fertility in Uganda: Young people recount obstacles and enabling factors to use of contraceptives. BMC Public Health. 2010;10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palomino González R, Kadengye DT, Mayega RW. The knowledge-risk-behaviour continuum among young Ugandans: What it tells us about SRH/HIV integration. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(Suppl 1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6809-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sebti A, Buck M, Sanzone L, Liduke BBB, Sanga GM, Carnevale FA. Child and youth participation in sexual health-related discussions, decisions, and actions in Njombe, Tanzania: A focused ethnography. J Child Heal Care. 2019;23(3):370–81. doi: 10.1177/1367493518823920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sommer M. Ideologies of sexuality, menstruation and risk: Girls’ experiences of puberty and schooling in northern Tanzania. Cult Heal Sex. 2009;11(4):383–98. doi: 10.1080/13691050902722372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bastien S, Leshabari MT, Klepp KI. Exposure to information and communication about HIV/AIDS and perceived credibility of information sources among young people in northern Tanzania. African J AIDS Res. 2009;8(2):213–22. doi: 10.2989/AJAR.2009.8.2.9.861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Damian RS, Zakumumpa H, Fonn S. Youth underrepresentation as a barrier to sexual and reproductive healthcare access in Kasulu district, Tanzania: A qualitative thematic analysis. Int J Public Health. 2020;65(4):391–8. doi: 10.1007/s00038-020-01367-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mkumbo KAK. What Tanzanian young people want to know about sexual health; implications for school-based sex and relationships education. Sex Educ. 2010;10(4):405–12. doi: 10.1080/14681811.2010.515097 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mtasingwa LV. Challenges Facing Tanzanian Youth in the Fight Against HIV/AIDS: Lessons Learnt from Mbeya Region, Southern Highlands. Forum Dev Stud [Internet]. 2020. May 3;47(2):283–306. doi: 10.1080/08039410.2020.1784264 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mung’ong’o S, Mugoyela V, Kimaro B. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice on Contraceptive Use among Secondary School Students in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. East Cent African J Pharm Sci. 2010;13(2):43–9. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nyblade L, Stockton M, Nyato D, Wamoyi J. Perceived, anticipated and experienced stigma: exploring manifestations and implications for young people’s sexual and reproductive health and access to care in North-Western Tanzania. Cult Heal Sex. 2017;19(10):1092–107. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2017.1293844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Plummer ML, Wamoyi J, Nyalali K, Mshana G, Shigongo ZS, Ross DA, et al. Aborting and suspending pregnancy in Rural Tanzania: An ethnography of young people’s beliefs and practices. Stud Fam Plann. 2008;39(4):281–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00175.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Remes P, Renju J, Nyalali K, Medard L, Kimaryo M, Changalucha J, et al. Dusty discos and dangerous desires: Community perceptions of adolescent sexual and reproductive health risks and vulnerability and the potential role of parents in rural Mwanza, Tanzania. Cult Heal Sex. 2010;12(3):279–92. doi: 10.1080/13691050903395145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adaji SE, Warenius LU, Ong’any AA, Faxelid EA. The Attitudes of Kenyan In-School Adolescents Toward Sexual Autonomy. Afr J Reprod Health. 2010;14(1):33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rehnström Loi U, Otieno B, Oguttu M, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Klingberg-Allvin M, Faxelid E, et al. Abortion and contraceptive use stigma: a cross-sectional study of attitudes and beliefs in secondary school students in western Kenya. Sex Reprod Heal Matters. 2019;27(3). doi: 10.1080/26410397.2019.1652028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mason L, Nyothach E, Alexander K, Odhiambo FO, Eleveld A, Vulule J, et al. “We keep it secret so no one should know”—A qualitative study to explore young schoolgirls attitudes and experiences with menstruation in rural Western Kenya. PLoS One. 2013;8(11). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mitchell EMH, Halpern CT, Kamathi EM, Owino S. Social scripts and stark realities: Kenyan adolescents’ abortion discourse. Cult Heal Sex. 2006;8(6):515–28. doi: 10.1080/13691050600888400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mutea L, Ontiri S, Kadiri F, Michielesen K, Gichangi P. Access to information and use of adolescent sexual reproductive health services: Qualitative exploration of barriers and facilitators in Kisumu and Kakamega, Kenya. PLoS One. 2020;15(11 November):1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stats MA, Hill DR, Ndirias J. Knowledge and misconceptions surrounding family planning among Young Maasai women in Kenya. Glob Public Health. 2020;1847–56. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2020.1788112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tavrow P, Karei EM, Obbuyi A, Omollo V. Community norms about youth condom use in Western Kenya: is transition occurring? Afr J Reprod Health. 2012;16(2):241–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Coast E, Jones N, Francoise UM, Yadete W, Isimbi R, Gezahegne K, et al. Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health in Ethiopia and Rwanda: A Qualitative Exploration of the Role of Social Norms. SAGE Open. 2019;9(1). doi: 10.1177/2158244019833587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Atchison CJ, Cresswell JA, Kapiga S, Nsanya MK, Crawford EE, Mussa M, et al. Sexuality, fertility and family planning characteristics of married women aged 15 to 19 years in Ethiopia, Nigeria and Tanzania: A comparative analysis of cross-sectional data. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12978-019-0666-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Balabanova D, McKee M, Mills A, Wait G, Haines A. What can global health institutions do to help strengthen health systems in low income countries? Heal Res Policy Syst. 2010;8(22):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-8-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krumeich A, Meershoek A. Health in global context; beyond the social determinants of health? Glob Health Action. 2014;7:1–8. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.23506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bernays S, Bukenya D, Thompson C, Ssembajja F, Seeley J. Being an ‘adolescent’: The consequences of gendered risks for young people in rural Uganda. Childhood. 2018;25(1):19–33. doi: 10.1177/0907568217732119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kendall-Taylor N. Shifting the Frame to Change How We See Young People. J Adolesc Health. 2020;66(2):137–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.11.297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Evelo J. Engaging Young People from the Beginning—SRHR–Women Deliver. Choice Youth Sex [Internet]. 2018;9100. https://womendeliver.org/2018/engaging-young-people-beginning-srhr/.

- 69.UN General Assembly. Convention on the rights of the child. New York; 1989.

- 70.Elder BC, Odoyo KO. Multiple methodologies: using community-based participatory research and decolonizing methodologies in Kenya. Int J Qual Stud Educ. 2018;31(4):293–311. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2017.1422290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gokiert RJ, Willows ND, Georgis R, Stringer H. Wâhkôhtowin: The governance of good community-academic research relationships to improve the health and well-being of children in Alexander First Nation. Int Indig Policy J. 2017;8(2). doi: 10.18584/iipj.2017.8.2.8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ochocka J, Janzen R. Breathing life into theory: Illustrations of community-based research–Hallmarks, functions and phases. Gateways Int J Community Res Engagem. 2014;7(1):18–33. 10.5130/ijcre.v7i1.3486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chakraborty K. “The good muslim girl”: Conducting qualitative participatory research to understand the lives of young muslim women in the bustees of Kolkata. Child Geogr. 2009;7(4):421–34. doi: 10.1080/14733280903234485 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gill R, Black A, Dumont T, Fleming N. Photovoice: A Strategy to Better Understand the Reproductive and Sexual Health Needs of Young Mothers. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29(5):467–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Le TM, Yu N. Sexual and reproductive health challenges facing minority ethnic girls in Vietnam: a photovoice study. Cult Heal Sex. 2020;0(0):1–19. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2020.1753813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pulerwitz J, Michaelis A, Weiss E, Brown L, Mahendra V. Reducing HIV-related stigma: Lessons learned from horizons research and programs. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(2):272–81. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Institute for Reproductive Health (IRH) and Center for Child and Human Development Georgetown University. Exploring social norms around reproductive health affecting unmarried adolescent girls in Burundi. 2021.

- 78.Chandra-Mouli V, Neal S, Moller AB. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health for all in sub-Saharan Africa: a spotlight on inequalities. Reprod Health. 2021;18(Suppl 1):1–4. doi: 10.1186/s12978-021-01145-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kantor LM, Lindberg L. Pleasure and sex education: The need for broadening both content and measurement. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(2):145–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wangamati CK. Comprehensive sexuality education in sub-Saharan Africa: adaptation and implementation challenges in universal access for children and adolescents. Sex Reprod Heal Matters. 2020;28(2). doi: 10.1080/26410397.2020.1851346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wekesah FM, Nyakangi V, Njagi J, Bangha M, Onguss M. Comprehensive Sexuality Education in Sub-Saharan Africa [Internet]. 2019. https://aphrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/CSE-in-SSA-FINAL-2019.pdf.

- 82.Kapilashrami A. What is intersectionality and what promise does it hold for advancing a rights-based sexual and reproductive health agenda? BMJ Sex Reprod Heal. 2020;46(1):4–7. doi: 10.1136/bmjsrh-2019-200314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]