Abstract

Background

Globally, there is a rise in chronic disease, including cancer, major organ failure and dementias. Patients and their families in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) pay a high proportion of medical costs out of pocket (OOP), and a diagnosis of serious illness often has catastrophic financial consequences. We therefore conducted a review of the literature to establish what is known about OOP costs near end of life in LMICs.

Aims

To identify, organise and report the evidence on out-of-pocket costs in adult end-of-life populations in LMIC.

Methods

A systematic search of 8 databases and a hand search of relevant systematic reviews and grey literature was performed. Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts, assessed papers for eligibility and extracted data. The review was registered with PROSPERO and adhered to the Preferred Reporting items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool was used to assess quality. The Wagstaff taxonomy was used to describe OOP.

Results

After deduplication, 9,343 studies were screened, of which 51 were read and rejected as full texts, and 12 were included in the final review. OOP costs increased with advanced illness and disease severity. The main drivers of OOP were medications and hospitalizations, with high but variable percentages of the affected populations reporting financial catastrophe, lost income, foregone education and other pressures.

Conclusion

Despite a small number of included studies and heterogeneity in methodology and reporting, it is clear that OOP costs for care near end of life in LMIC represent an important source of catastrophic health expenditures and impoverishment. This suggests a role for widespread, targeted efforts to avoid poverty traps. Financial protection policies for those suffering from incurable disease and future research on the macro- and micro- economics of palliative care delivery in LMIC are greatly needed.

Introduction

Background

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) face sharply increasing incidence of non-communicable diseases such as cancer, major organ failure, and Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias [1]. Health systems widely lack capacity and resources to meet even current levels of need with curative and supportive treatment [2]. Patients and their families in LMICs pay a high proportion of costs out of pocket, and a diagnosis of serious illness often has catastrophic financial consequences for a household [3].

The end-of-life phase has unique physical, psychological and spiritual challenges [4]. There is also a widely documented association between the last year of life and health care utilization [5], particularly when people die with multiple serious chronic diseases [6]. Therefore end-of-life care brings specific financial pressures for patients and their families in terms of medical care (e.g. paying for medications) and unpaid care, foregone income, and transport to and from appointments [7].

People with terminal illness and their families in LMICs are vulnerable to bankruptcy and impoverishment as populations age, and the poorest sections of society are routinely the most vulnerable of all [8]. One particular susceptibility is spending on supposedly disease-modifying treatments, particularly in the absence of palliative care services that aim to guide the patient and family towards better choices. The downstream effects of palliative care are both improved patient reported outcomes, and cost savings [9, 10]. In LMICs, it is unknown what percentage of the high costs of medical care are borne early versus later on in the disease trajectory: it may be that early drivers of financial hardship begin at time of diagnosis, such that by the time a patient reaches end stage disease, the family has already been burdened by heavy costs. For this reason, in high income settings, there is evidence to support early initiation of palliative care, alongside curative treatments [11, 12].

Faced with impossible choices between earning income or caring for a loved one, or between retaining basic assets or paying for treatment, end-of-life care is a potential poverty trap for many [9]. Palliative care services in those countries are generally underdeveloped with widespread prevalence of unmet need [10].

Out-of-pocket costs in LMICs are a long-standing policy question [3]. The economics of end-of-life care has received growing attention in the last decade, but with a heavy focus on high-income countries where high end-of-life costs for the health system often represent overtreatment and poorly coordinated care between hospital and home settings [13]. The situation in LMICs is fundamentally different: high costs near end of life are widely borne by patients and their families, where the alternative is to receive no treatment [9]. Studies examining out-of-pocket costs and family burden have also dealt predominantly with high-income country settings [14].

Rationale and aim

We are unaware of any prior review examining the costs to patients and families in the end-of-life phase in LMICs. We therefore conduct a review of the literature to establish what is known about out-of-pocket costs near end of life in those settings. Arising results can inform efforts in low-resource settings to upscale palliative care provision, to design financial protection policies for people with non-communicable disease, and to conduct future research on the economics of palliative and end-of-life care in settings where prior attention has been minimal.

Materials & methods

Protocol and registration

We registered a protocol for this systematic review on PROSPERO (CRD42020215188). Registration date was November 19th, 2020.

Search strategy and information sources

A clinical librarian (AB) developed the search strategy after a consultation with ER and PM. AB also received related articles which helped formulate the search strategy with the use of the Yale MeSH Analyzer and were later used to validate search concepts.

The search strategy was peer-reviewed by another senior librarian. The search strategy used both keywords and controlled and indexed vocabulary combining the terms for low-and-middle income countries, cost, and palliative care.

The databases were searched from inception to August 5, 2020; the databases included: MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), APA PsycInfo (Ovid), Global Health (Ovid), CINAHL (Ebsco) Web of Science (indexes: SCI-EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI, CPCI-S, CPCI-SSH, BKCI-S, BKCI-SSH, ESCI, CCR-EXPANDED, IC), Scopus, EconLit (ProQuest), and Cochrane CENTRAL. See S1 File for the search details for each database.

We supplemented database searches with other methods. One reviewer (JJ) hand-searched three potentially relevant systematic reviews [10, 15, 16]. One reviewer (AG or AK) hand-searched from 2010 to August 2020 the following journals: Lancet Global Health, BMJ Global Health and Indian Journal of Palliative Care. One reviewer (JJ) hand-searched the following websites as grey literature sources: World Bank, World Health Organization and United Nations University economics department [17–19].

Eligibility criteria and study selection

Inclusion criteria

Population. Adults (aged 18+) at the end of life or diagnosed with one of the following serious life-limiting medical illnesses: advanced cancer, serious heart disease (e.g., heart attack, PVD, CHF), major organ failure (e.g., lung, liver, kidney), advanced Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, AIDS/HIV.

Intervention. Palliative care, supportive care and end of life, opioids, and other pain management medications.

Comparison. Any or none.

Outcome. Out-of-pocket costs incurred by patients and their families in care and treatment for end-of-life care. We include studies that measure the monetary cost of providing informal care, including costed dedicated time, income foregone through lost work, and additional costs incurred (e.g., travel, patient medications).

Setting. Low- and middle-income countries, as defined by the World Bank [20].

Study design. Any.

Exclusion criteria

Population. Studies of children. Studies of people with other chronic diseases (e.g., TB, diabetes) as a primary diagnosis. Studies of people in the early stages of a terminal disease.

Intervention. Screening, identification, diagnosis of disease. Medications with a predominantly curative intent.

Outcome. Costs of care where the patient does not contribute their own resources in money or time, e.g., any service free at the point of use. Prevalence of out-of-pocket payment or unpaid care (e.g., “how many households have an informal carer?”) where that prevalence is not quantified as an estimation of time or cost.

Setting. Studies in high-income countries.

Other. Studies where our population, outcome and setting are not specifically reported, e.g. (1) an overview of out-of-pocket costs at the population level that does not delineate those with terminal illness or at end of life, e.g. (2) a cost of illness study for a terminal illness that does not delineate out-of-pocket and centrally funded costs. Studies where out-of-pocket costs are hypothetical and/or employed as a predictor (e.g., “Is high potential out-of-pocket costs a reason why women do not attend breast cancer screening?”; “What is the willingness to pay for different cancer treatments?”). Any publication type except research articles (e.g., letters to the editor, conference abstracts). We included only English language articles and retained eligible abstracts in other languages to assess risk of bias from the English-only constraint.

Rationale for these criteria

We imposed three basic criteria: LMIC setting, palliative/end-of-life population and out-of-pocket costs as an outcome of interest. Among these, only the first can be categorized discretely according to objective rules (we use The World Bank) [20]. For population, we anticipated challenges in distinguishing the end-of-life phase given that life-limiting illnesses often have poor prognosis in LMIC settings. We did not require that populations are characterized as “end of life” but we did require that the disease be advanced. Populations defined as “early” in a trajectory of serious disease, as well as evaluations of prevention, including vaccination, screening and diagnosis, were excluded. Pharmacoeconomic evaluations of any drugs with life-extending intent were also excluded. For out-of-pocket costs, we defined this broadly to include literal currency spending but also unpaid care and other labor, transport costs, foregone income. Studies that report “total” costs in any circumstance, but do not report separately out-of-pocket and informal care costs, were excluded at full text review. Prior experience showed that evidence on interventions near end of life in LMICs is scant [10], but any study that described, quantified, evaluated determinants, or otherwise addressed specifically our outcome, population and setting of interest were considered eligible.

Study selection

Each title/abstract was screened as (in)eligible by two independent reviewers (two of AG, AK, ER, PM). Disagreements were settled by consensus, with either ER or PM acting as the third reviewer.

Full texts were screened using the same process as titles/abstracts. Quality assessment of included studies was performed by two independent reviewers (one of AG and AK, and one of ER and PM) using the MMAT tool. There was no quality cut-off for inclusion, we resolved that eligible studies be reported in the context of their methods and limitations.

Data extraction and data items

Data were extracted using the same process as titles/abstracts: two independent reviewers, with a third senior reviewer (ER or PM) adjudicating any conflicts. Data were extracted to a bespoke form developed in Excel, that required data points on author, year of publication, country of data collection, year of data collection, study design, sample size (total, exposure, comparison), population, intervention/exposure, comparison, outcome of interest, main results, key themes/messages/strengths, and key limitations. The two reviewers’ outputs were then merged into a single file by a third reviewer (AG or AK), and conflicts or problems solved by consensus.

Risk of bias within individual studies and across studies

In anticipation of a small, heterogeneous literature we did not evaluate risk of bias specifically but assessed bias as part of quality assessment.

Summary measures and synthesis of results

In anticipation of a small, heterogeneous literature we did not pre-specify an outcome of interest (e.g., risk ratio or cost-effectiveness ratio) but instead adopted a flexible approach depending on identified studies, which could include descriptive studies. We planned therefore for narrative synthesis, organizing reported out-of-pocket costs according to seven measures in a well-known systematic review: (i) expenditure in absolute (international dollar) terms; (ii) measures of dispersion (or risk); (iii) the out-of-pocket budget share; (iv) progressivity; (v) the incidence of “catastrophic” expenditures; (vi) inequality in the incidence of catastrophic expenditures; (vii) the incidence of “impoverishing” out-of-pocket expenditures, as well as the addition to the poverty gap due to out-of-pocket expenditures [3].

Results

Study selection

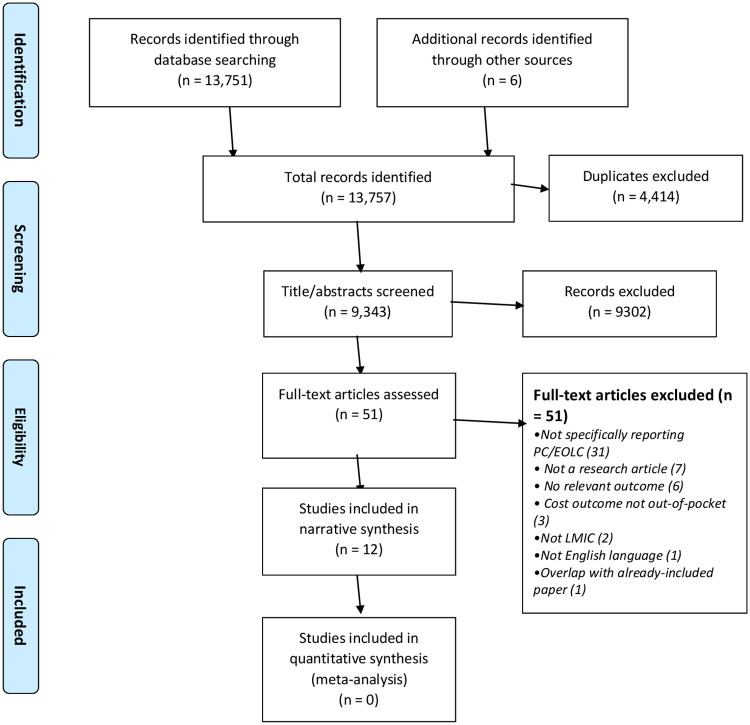

The database search returned a total of 13,751 records with 9,337 unique articles. The hand search identified six additional studies and the grey literature search identified no relevant studies. These 9,343 studies were screened in Covidence. We excluded 9,280 articles after screening of titles and abstracts, and a further 51 articles after reading the full text. One of these exclusions was due to not being in English [21]. Thus, we included 12 articles in our review. See Fig 1.

Fig 1. PRISMA diagram.

Study characteristics

The data extracted from the twelve included studies [22–33] are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Data extraction- all included studies.

| Lead author YearcCountry | Country | Aim(s) | Design | Data sources, years | Inclusion criteria | Sample size | Outcome(s) of interest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arisar (2020) | Pakistan | To describe the financial burden imposed by chronic liver disease (CLD) | Cross-sectional descriptive prospective study | Primary data collection 2016 | CLD patients admitted to a large urban hospital aged 18–80 | N = 190, of whom 28 had a severe disease status | Prevalence of objective and subjective financial burden from CLD: savings, paying bills, access to food and medicine, “worsening economic status” |

| Atieno (2018) | Kenya | To describe the costs of treating cancer patients | Cross-sectional descriptive retrospective study | Secondary analysis of hospital accounting data 2014–16 | Random sample of 10% of cancer patients admitted to a large urban hospital aged 18+ | N = 412 | Direct medical costs of palliative care in KES and USD, “most” paid OOP |

| Das (2018) | India | To study the trends in out-of-pocket expenditure among hospital inpatients over time, and to compare trends for those dying in hospital and discharged alive | Case-control retrospective study | Secondary analysis of nationally representative survey data 1995–96; 2004–05; 2014–15 | Respondents to three waves of a recurring survey of ‘morbidity and health care’ | N = 94,084 Decedents (cases): 4,357 Survivors (controls): 89,727 | OOP inpatient expenditure in INR |

| Emanuel (2010) | India | To gather pilot data on the economic impact of terminal illness on families, and on the feasibility of training caregivers as a method of stemming illness-related poverty. | Exploratory, descriptive prospective study | Primary data collection 2008 | Convenience sampling of families in contact with a single palliative care provider | N = 11 patient-caregiver dyads (22 participants) | Total debt, total health care spending in INR, USD Prevalence of objective and subjective financial burden: giving up work, missing/ discontinuing education, lost income, forced to sell assets, feeling pressure to marry, feeling pressure to generate other income |

| Kimman (2015) | Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Phillipines, Thailand, Vietnam | To describe prevalence of death and financial catastrophe in the year following a cancer diagnosis | Prospective longitudinal study | Primary data collection 2012–13 | People admitted to 47 public and private hospitals and cancer centres with a first-time cancer aged 18+ | N = 9,513 | Prevalence of financial catastrophe, defined as out-of-pocket medical costs exceeding 30% of annual income |

| Kongpakwattana (2019) | Thailand | To describe costs, quality of life and caregiver burden associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). | Cross-sectional descriptive prospective study | Primary data collection and secondary analysis of hospital accounting data 2017–18 | People admitted to a large urban hospital with a diagnosis of AD for at least six months and aged 60+ | N = 148, of whom 54 had a severe disease status | Out-of-pocket expenditure in USD, unpaid caregiver burden |

| Kumar (2018) | India | To describe socio- economic status and demographic profile of patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care. | Cross-sectional descriptive prospective study | Primary data collection 2017 | Patients with advanced cancer receiving outpatient palliative care at a single institution. | N = 80 | Subjective financial burden: financial insecurity |

| Ladusingh (2013) | India | To compare OOP inpatient care expenditures of decedents and survivors | Case-control retrospective study | Secondary analysis of nationally representative survey data 2004–05 | Respondents to one wave of a recurring survey of ‘morbidity and health care’ | N = 31,868 Decedents (cases): 715 Survivors (controls): 31,153 | Out-of-pocket expenditure in INR |

| Leng (2019) | China | To describe cancer treatments and care costs during the last 3 months of life, and to compare geographical disparities | Cross-sectional descriptive retrospective study | Primary data collection 2016 | Caregivers of people who died from cancer between 2013 and 2016. | N = 792 | End-of-life (EOL) health care costs in USD; prevalence of borrowing to meet EOL costs |

| Ngalula (2002) | Tanzania | To assess the levels and determinants of medical care use and household expenditure during terminal illness. | Cross-sectional descriptive retrospective study | Secondary analysis of longitudinal survey data 1996–98 | Households of people who had died aged 15–59 with an established cause of death | N = 181 | Prevalence of health care expenditure and funeral expenses borne OOP; received financial assistance outside the family; sold property for care or funeral |

| Prinja (2018) | India | To assess the health system costs, out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure and extent of financial risk protection associated with treatment of liver disorders. | Case-control retrospective study | Primary data collection and secondary analysis of hospital accounting data 2013–14 | Liver disorder patients admitted to the intensive care unit or high dependency unit of a large urban hospital | N = 150 | Out-of-pocket expenditure in USD and INR; prevalence of catastrophic health expenditure, defined as out-of-pocket medical costs exceeding 40% of non-subsistence expenditure |

| Ratcliff (2017) | India | To describe prevalence of household poverty, association between poverty and palliative care receipt | Single cohort descriptive study, interviews conducted once on experiences at different time points | Primary data collection 2015 | Patients or family members at one of three rural palliative care providers | N = 129 | Prevalence of poverty, medical costs, lost work, debts, sale of assets; association between palliative care receipt and medical costs, work |

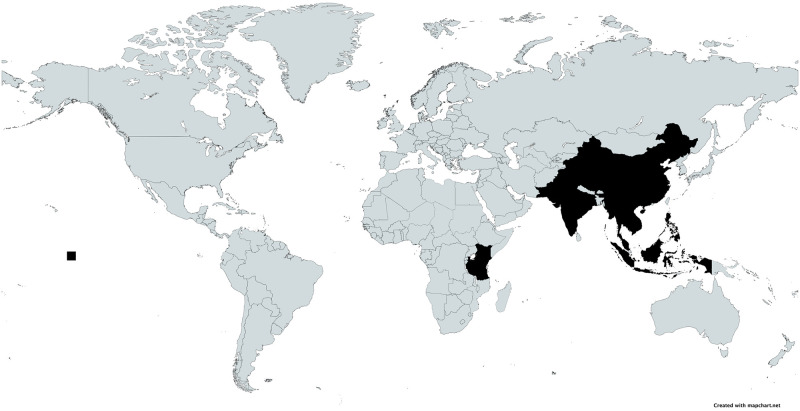

The earliest study was published in 2002 and the most recent in 2020 with a median publication year of 2018. There were six studies conducted in India, and one each conducted in China, Kenya, Pakistan, Tanzania, Thailand and Southeast Asia (covering Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam). See Fig 2.

Fig 2. Map of included countries.

Black = Country included in systematic review.

There were six descriptive cross-sectional studies, of which three were conducted prospectively [26, 27, 32] and three retrospectively [22, 29, 30]. Three further prospective studies involved original data collection: one longitudinal study,[25] one cohort study [33] and one exploratory pilot study.[24] Three were retrospective case-control studies comparing people who died in hospital with those who did not. [23, 28, 31]. No study evaluated the effects of an intervention. The largest study had 94,084 participants, the smallest study had 11 participants with a median sample size of 185.5.

Sampling

Six studies based their sampling frames on diagnosis of a specific disease: three in cancer, [22, 25, 29] two in liver disease [31, 32] and one in Alzheimer’s disease [26]. Three studies conducted convenience sampling via a palliative care provider [24, 27, 33]. Two studies analyzed large population-representative surveys on health and morbidity [23, 28]. One study surveyed households that had recently suffered a bereavement [30].

Outcomes

Nine studies evaluated outcomes specified by the taxonomy of Wagstaff et al [3]. Two studies measured prevalence of financial catastrophe, contextualizing costs according to the means of people with serious illness and their families. [25, 31] Seven studies quantified out-of-pocket spending and/or debt in absolute currency amounts [22–24, 26, 28, 29, 31]. Additionally, one study quantified unpaid carer burden [26] and three studies measured objective and/or subjective financial burden [24, 30, 33].

Quality of reporting

Quality assessment were performed by two independent reviewers (one of AG and AK, and one of ER and PM) using the MMAT tool. The MMAT is intended to be used as a checklist for concomitantly appraising and/or describing studies included in systematic mixed studies reviews (reviews including original qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies). There was no quality cut-off for inclusion, and studies have been reported in the context of their methods and limitations. A summary of the quality assessments is provided in Table 2. Full details of the MMAT scores are provided as S2 File.

Table 2. MMAT quality results.

| Atieno | Arisar | Das | Emanuel | Kimman | Kongpakwattana | Kumar | Ladusingh | Leng | Ngalula | Prinja | Ratcliff | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening questions | Are there clear research questions? | ||||||||||||

| Do the collected data allow to address the research questions? | |||||||||||||

| Qualitative | 1.1. Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | ||||||||||||

| 1.2. Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | |||||||||||||

| 1.3. Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | |||||||||||||

| 1.4. Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by data? | |||||||||||||

| 1.5. Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | |||||||||||||

| Quantitative randomized controlled (trials) | 2.1. Is randomization appropriately performed? | ||||||||||||

| 2.2. Are the groups comparable at baseline? | |||||||||||||

| 2.3. Are there complete outcome data? | |||||||||||||

| 2.4. Are outcome assessors blinded to the intervention provided? | |||||||||||||

| 2.5 Did the participants adhere to the assigned intervention? | |||||||||||||

| Quantitative non-randomized | 3.1. Are the participants representative of the target population? | ||||||||||||

| 3.2. Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? | |||||||||||||

| 3.3. Are there complete outcome data? | |||||||||||||

| 3.4. Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? | |||||||||||||

| 3.5. During the study period, is the intervention administered (or exposure occurred) as intended? | |||||||||||||

| Quantitative descriptive | 4.1. Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the quantitative research question? | ||||||||||||

| 4.2. Is the sample representative of the target population? | |||||||||||||

| 4.3 Are measurements appropriate? | |||||||||||||

| 4.4 Is the risk of non-response bias low? | |||||||||||||

| 4.5 Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | |||||||||||||

| Mixed-methods | 5.1. Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed methods design to address the research question? | ||||||||||||

| 5.2. Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? | |||||||||||||

| 5.3. Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? | |||||||||||||

| 5.4. Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? | |||||||||||||

| 5.5. Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? |

Green = Yes.

Red = No.

Yellow = Unable to determine.

Main results

Main results of each included study are presented in Tables 3–6, separated by outcome.

Table 3. Results of studies quantifying catastrophic financial circumstances.

| Study | Scope | Summary statistics | Key conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kimman (2015) | Prevalence of death and financial catastrophe, defined as out-of-pocket medical costs exceeding 30% of annual income, in the year following a cancer diagnosis | Death: 29% Alive financial catastrophe: 48% Alive no financial catastrophe: 23% | •A minority of people experienced neither death nor financial catastrophe in the year following a cancer diagnosis |

| •Both death and financial catastrophe were significantly associated with proximity to death and baseline socioeconomic status | |||

| •Insurance was also protective against financial catastrophe | |||

| Prinja (2018) | Prevalence of death and financial catastrophe, defined as exceeding 40% of non-subsistence expenditure, among hospital inpatients | All, financial catastrophe: 78% Died, financial catastrophe: 92% Alive, financial catastrophe: 75% | •Very high prevalence of financial catastrophe among both decedents and survivors |

| •Prevalence higher in intensive care unit among survivors, and higher in high dependency unit among decedents | |||

| •Medicines account substantively for costs, showing that purchasing schemes could reduce financial catastrophe |

Table 6. Results of studies reporting prevalence of objective and subjective financial burden.

| Study | Scope | Summary statistics | Key conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ngalula (2002) | Among people who died, prevalence of health care expenditure and funeral expenses borne by decedent and spouse; received financial assistance outside the family; sold property for care or funeral | Decedent or spouse was primary source of payment: AIDS: 37% Other diseases: 48% Injuries: 14% Received financial assistance outside the family: AIDS: 1% Other diseases: 5% Injuries: 0% Sold property for care or funeral: AIDS: 29% Other diseases: 10% Injuries: 19% |

•Widespread prevalence of decedents and families meeting costs, including selling property •Little evidence of financial assistance outside the family |

| Emanuel (2010) | Prevalence of objective and subjective financial burden among people receiving palliative care | Patient left workforce: 100% Family members working less: 100% Education missed or foregone: 100% Had to sell assets: 100% Married/feeling pressure to marry: 45% Resort to dangerous or illegal work: 64% |

•Foregone work, income, education reported by all participants •Widespread prevalence of pressure to replace lost income and meet medical costs |

| Ratcliff (2017) | Prevalence of household poverty, association between poverty and palliative care receipt | Patient left workforce: 66% Family member left workforce: 26% In debt: 98% Had to sell assets: 59% |

•Widespread prevalence of lost income, debt, pressure to sell assets •Palliative care reportedly associated with lower out-of-pocket spending and high income through return to work and awareness of government benefits. No formal statistical evaluation of this. |

| Kumar (2018) | Prevalence of subjective financial burden among patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care | Financial insecurity among participants: 26% Concern regarding financial security of family members in future: 33% |

•Widespread prevalence of insecurity about current and future finances |

| Leng (2019) | Prevalence of borrowing among cancer decedents | Borrowing to meet EOL expenses: 33% | •Widespread prevalence of borrowing, with variation by urban/rural, geographic region and spending type |

| Arisar (2020) | Prevalence of objective and subjective financial burden among patients with severe chronic liver disease | Worsening economic status: 89% Stopped saving: 89% Utilization of previous savings: 93% Need to borrow to meet expenses: 71% Delay in repaying loans: 36% Delay in children’s education: 61% Electricity/gas cut off: 14% Had to leave current house: 14% Had to forego food: 22% Unpaid medical expenses: 47% Skip medicines: 72% Buy fewer medicines than required: 61% Missed surgery: 57% Missed doctor’s appointment: 61% |

•Socioeconomic burden of chronic liver disease is considerable •Magnitude of burden is strongly associated with severity of disease–and is therefore greatest in the end-of-life cohort |

Synthesis of results

Financial catastrophe

Results with respect to financial catastrophe are summarized in Table 3.

In India Prinja et al. [31] reported that 92% of people who died in hospital with advanced liver disease suffered catastrophic finances, defined as out-of-pocket spending that exceeded 40% of subsistence income. Medicines accounted substantively for costs, meaning that publicly funded purchasing schemes could address directly this financial catastrophe.

Kimman et al. [25] followed people for a year following a cancer diagnosis in seven South East Asian countries and found that only 23% were both alive and free of financial catastrophe, defined as out-of-pocket medical costs exceeding 30% of annual income. Among the sample, 48% were alive but facing financial catastrophe, and 29% had died. Since death and financial catastrophe are reported as competing outcomes, it is not known what proportion of those who died experienced high OOP spending and as such the results are not directly comparable with those of Prinja et al [31].

Out-of-pocket costs in absolute terms

Results with respect to costs in absolute terms are summarized in Table 4. All studies reported substantial costs for their populations of interest, and additional factors that determined or mediated costs were identified.

Table 4. Results of studies quantifying out-of-pocket spending, debt.

| Study | Scope | Summary statistics | Key conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emanuel (2010) | Total OOP spending on health care last two months, total debt among people receiving palliative care | Mean total spending: INR 15,000 (USD 325) Mean debt: INR 50,000 (USD 1,082) | •High prevalence of debt, out-of-pocket spending |

| Ladusingh (2013) | Total OOP spending among hospital inpatients | Mean costs Decedents (2004/5): INR 10,036 Survivors (2004/5): INR 7,126 | •OOP spending was significantly higher for those dying in hospital than those discharged alive |

| Atieno (2018) | Total direct medical costs of palliative care in people with cancer | Average cost of palliative care: KES 98,931 (USD 977) Sub-group in public hospital: KES 94,867 (USD 937) Sub-group in private hospital: KES 118,708 (USD 1172) |

•Wide variation in cancer costs by diagnosis and treatment choices •Palliative care accounted for 12% of cancer costs •Other cost categories, e.g. surgery, chemotherapy, were not reported specifically for end-of-life population |

| Das (2018) | Total OOP spending among hospital inpatients | Mean costs Decedents (2004/5): INR 22,649 Survivors (2004/5): INR 15,485 Decedents (2014/5): INR 43,897 Survivors (2014/5): INR 19,438 |

•OOP spending was significantly higher for those dying in hospital than those discharged alive •Mean decedent OOP spending nearly doubled during the ten-year observation period |

| Prinja (2018) | Total OOP spending among hospital inpatients with liver disease | Mean costs All (ICU): INR 2,465 Decedents (ICU): INR 2,128 Survivors (ICU): INR 2,465 All (ICU): INR 1,752 Decedents (ICU): INR 3,553 Survivors (ICU): INR 1,484 |

•OOP costs are higher in intensive care unit among survivors, and higher in high dependency unit among decedents •Wide variation in costs by locality, education, occupation, but these difference are not statistically significant |

| Kongpakwattana (2019) | Total OOP spending among people diagnosed with dementia | Mean OOP spending Mild: USD 509 Moderate: USD 951 Severe: USD 1003 |

•Mean OOP spending was highest among the severe disease group, but this difference was not statistically significant |

| Leng (2019) | Total end-of-life (EOL) health care costs among cancer decedents | Mean total spending OOP: USD 11,288 | •OOP spending was 36% of total cancer costs •OOP spending was significantly higher in urban areas than rural, geographic variation was also identified |

Three studies in the hospital setting found that OOP costs for deceased patients in inpatient care is much greater than that of survivors [23, 28, 31]. Moreover, both total costs for decedents and the difference between decedent and survivor costs appear to be growing over time [21].

Cancer costs in private health care settings were higher than those in public settings [20], and higher for patients living in urban areas than rural areas [29]. People already receiving palliative care have high levels of cost and associated debt, [24] and magnitude of costs is strongly associated with disease severity [26, 32].

Unpaid carer burden

One study looked at unpaid carer burden, summarized in Table 5 [26]. Unpaid caregiving hours were high in all stages of Alzheimer’s disease and highest among the severe disease group. This difference was statistically significant.

Table 5. Results of studies quantifying unpaid care.

| Study | Scope | Summary statistics | Key conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kongpakwattana (2019) | Hours’ unpaid caregiving per month for people diagnosed with dementia | Mean total caregiving time Mild: 204 hours Moderate: 253 hours Severe: 354 hours | •Unpaid caregiving was highest among the severe disease group, and this difference was statistically significant |

Objective and subjective financial burden

Studies quantifying the incidence or prevalence of financial burden in descriptive measures are summarized in Table 6.

These measures affirm the findings in other tables that advanced medical illness results in high costs and financial pressures. Further, illness and associated costs catalyze vicious economic circles for patients and families. Persons with serious illness overwhelmingly lose their jobs or leave the workforce [24, 33]. Family members leave their jobs and drop out of education to provide care [24, 32]. To meet costs, patients and their families borrow money [29, 32, 33] and sell assets, [24, 30, 33] and in some cases forego food, medicines and health care. [32] Financial pressures confer anxiety about the household’s future [27]. Family members feel pressure to marry, or to engage in risky or illegal activity, in order to address lost income and rising costs [24].

Discussion

Key results

Patients approaching end of life in LMIC pay a high proportion of medical costs out of pocket and often suffer catastrophic financial consequences, yet there is a dearth of robust, large scale health economic data to guide hypothesis-generating, poverty-reducing solutions. Financial catastrophe from serious medical illness is not only an issue for patients and families in the end-of-life stage but creates cyclical poverty traps: lost income, increasing borrowing and debt, anxiety and insecurity, and growing pressure to address financial pressures through drastic measures. Our systematic review directly addresses this global inequity with a rigorous search and summary of the existing literature, including a quality assessment.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of the review include the broad search terms, inclusion of grey literature, the geographical heterogeneity in the included studies country of origin, and use of two independent reviewers at each step of the review. Limitations of this review are that much of the existing literature is from household surveys and interviews, thus introducing bias however this is mitigated by country-specific estimates for OOP which were included in three of our included studies. Only studies in English were included.

Interpretation

Inadequate government spending on health is a recurring feature in LMICs. Weak health infrastructure leads to delays in diagnosis and resulting late disease presentations, heavy reliance on out-of-pocket payments and catastrophic health expenditures. Those patients impacted the most include those from remote areas, those with longer and repeat hospitalizations and with the following diagnoses: cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, terminal HIV/AIDs and end stage liver disease. As out-of-pocket spending is inversely proportional to life expectancy, earlier diagnoses through improved screening programs would likely result in more treatable disease, at lower cost.

Policies aimed at bolstering socioeconomic resilience and financial protection are greatly needed in LMICs. A better understanding of early versus late drivers of medical impoverishment is an urgent research priority, as this would inform these strategies. In addition to earlier detection of disease, the provision of early, home-based and widespread access to palliative care in LMIC would serve to decrease OOP and CHE for those with incurable disease, and thus should be considered as a critical health priority and global poverty-reduction strategy. Furthermore, in resource-scare environments, increased access to palliative care would have the secondary effect of liberating limited health resources for those patients with curable disease thus benefiting society at large. The need for greater access to palliative care in LMICs is clear and the evidence for its role as a poverty reduction strategy is emerging. Future research should focus on the implementation and health economic outcomes of palliative care in LMICs, thus improving care for billions of the most vulnerable patients in our global population.

Globally, demographic ageing is likely to result in an increased burden on all levels of health systems and household services, partly due to the relatively long duration of illness at the end of life. Holistic palliative care can mitigate the desperate poverty caused by life-limiting illness, particularly if initiated early in the illness, on a regular basis and on a broad scale. Home-based treatment also frees up hospitals to serve patients with reversible conditions.

Conclusion

Patients approaching end of life in LMIC pay a high proportion of medical costs out of pocket and often suffer financial catastrophe. These effects are long term and potential poverty traps: reduced household income, rising debt, deteriorating mental health, and narrowing life choices. Policies and interventions are needed to prevent these often-avoidable crises. Evidence to inform such policies and interventions is currently thin.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

A text file of the search strategies used in our systematic review.

(DOCX)

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Jaspers L, Colpani V, Chaker L, van der Lee SJ, Muka T, Imo D, et al. The global impact of non-communicable diseases on households and impoverishment: a systematic review. Eur J Epidemiol. 2015. Mar;30(3):163–88. doi: 10.1007/s10654-014-9983-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adam T, de Savigny D. Systems thinking for strengthening health systems in LMICs: need for a paradigm shift. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27:1–3. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr006 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wagstaff A, Eozenou P, & Smitz M. Out-of-Pocket Expenditures on Health: A Global Stocktake. The World Bank Research Observer. 2020; 35(2): 123–157. 10.1093/wbro/lkz009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan RJ., Webster J, & Bowers A. End-of-life care pathways for improving outcomes in caring for the dying. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016;2. Art. No.: CD008006. 10.1002/14651858.CD008006.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bekelman JE, Halpern SD, Blankart CR, Bynum JP, Cohen J, Fowler, et al. Comparison of site of death, health care utilization, and hospital expenditures for patients dying with cancer in 7 developed countries. JAMA.2016;315(3): 272–283. 10.1001/jama.2015.18603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis A, Nallamoth BK, Banerjee M, & Bynum JW. Identification of four unique spending patterns among older adults in the last year of life challenges standard assumptions. 2016; Health Affairs. 2016;35(7): 1316–1323. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardiner C, Brereton L, Frey R, Wilkinson-Meyers, Gott M. Exploring the financial impact of caring for family members receiving palliative and end-of-life care: A systematic review of the literature. Palliat Med. 2014; 28(5):375–90. 10.1177/0269216313510588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruk M, Goldman E, Galea S. Borrowing And Selling To Pay For Health Care In Low- And Middle-Income Countries. Health Affairs. 2009; 28(4):1056–66. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.4.1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson RE & Grant L. What is the value of palliative care provision in low-resource settings? BMJ Global Health. 2017; 2:e000139. 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reid EA, Kovalerchik O, Jubanyik K, Brown S, Hersey D, & Grant L. Is palliative care cost-effective in low-income and middle-income countries? A mixed-methods systematic review. BMJ Support.Palliat. Care. 2018; 9(2). 10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haun MW, Estel S, Rücker G, Friederich HC, Villalobos M, Thomas M, et al. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017. Jun 12;6(6):CD011129. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011129.pub2 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalgard KM, Bergenholtz H, Nielsen ME, Timm H. Early integration of palliative care in hospitals: A systematic review on methods, barriers, and outcome. Palliat Support Care (2014), 12, 495–513. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513001338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith S, Brick A, O’Hara S, & Normand C. Evidence on the cost and cost-effectiveness of palliative care: A literature review. Palliat Med. 2014; 28(2): 130–150. 10.1177/0269216313493466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sum G, Hone T, Atun R, Millett C, Suhrcke M, Mahal A et al. Multimorbidity and out-of-pocket expenditure on medicines: A systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. BMJ Glob Health. 2018; 3(1): e000505 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alam K., Mahal A. Economic impacts of health shocks on households in low and middle income countries: a review of the literature. Global Health 10, 21 (2014). 10.1186/1744-8603-10-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chakraborty R, El-Jawahri AR, Litzow MR, Syrjala KL, Parnes AD, Hashmi SK. A systematic review of religious beliefs about major end-of-life issues in the five major world religions. Palliat Support Care. 2017;15(5):609–622. doi: 10.1017/S1478951516001061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The World Bank Group. https://www.worldbank.org/en/home 4/15/21

- 18.Quah, D. (1999). World Institute for Development Economics Research. https://unu.edu/about/unu-system/wider 4/15/21

- 19.The World Bank. World {Bank} {Group}—{International} {Development}, {Poverty}, & {Sustainability}. https://www.worldbank.org/en/home 4/15/21

- 20.World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups–World Bank Data Help Desk. The World Bank. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups 4/15/221

- 21.Salinas-Escudero G, Carrillo-Vega MF, Pérez-Zepeda MU, & García-Peña C. Out of pocket expenditure on health during the last year of life of Mexican elderly: Analysis of the Enasem. Salud Publica de Mexico. 2019;61(4): 504–513. 10.21149/10146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atieno OM, Opanga S, Martin A, Kurdi A, & Godman B. Pilot study assessing the direct medical cost of treating patients with cancer in Kenya; findings and implications for the future. Journal of Medical Economics. 2018; 21(9): 878–887. 10.1080/13696998.2018.1484372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Das SK, Ladusingh L. Why is the inpatient cost of dying increasing in India? PLoS ONE. 2018; 13(9), e0203454. 10.1371/journal.pone.0203454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emanuel N, Simon MA, Burt M, Joseph A, Sreekumar N, Kundu T et al. Economic impact of terminal illness and the willingness to change it. J Palliat Med. 2010; 13(8), 941–944. 10.1089/jpm.2010.0055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimman M, Jan S, Yip CH, Thabrany H, Peters SA, Bhoo-Pathy N. et al. Catastrophic health expenditure and 12-month mortality associated with cancer in Southeast Asia: Results from a longitudinal study in eight countries. BMC Medicine. 2015; 13(1). 10.1186/s12916-015-0433-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kongpakwattana K, Dejthevaporn C, Krairit O, Dilokthornsakul P, Mohan D, & Chaiyakunapruk N. A Real-World Evidence Analysis of Associations Among Costs, Quality of Life, and Disease-Severity Indicators of Alzheimer’s Disease in Thailand. Value in Health. 2019;, 22(10): 1137–1145. 10.1016/j.jval.2019.04.1937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar G, Panda N, Roy R, & Bhattacharjee G. An observational study to assess the socioeconomic status and demographic profile of advanced cancer patients receiving palliative care in a tertiary-level cancer hospital of Eastern India. Indian J Palliat Care. 2018; 24(4): 496–499. 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_72_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ladusing L, Pandey A. High inpatient care cost of dying in India. J Public Health.2013; 21(5): 435–443. 10.1007/s10389-013-0572-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leng A, Jing J, Nicholas S, & Wang J. Geographical disparities in treatment and health care costs for end-of-life cancer patients in China: A retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1): 39. 10.1186/s12885-018-5237-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ngalula J, Urassa M, Mwaluko G, Isingo R, Ties Boerma J. Health service use and household expenditure during terminal illness due to AIDS in rural Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 2002;7(10):873–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00922.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prinja S, Bahuguna P, Duseja A, Kaur M, Chawla YK. Cost of Intensive Care Treatment for Liver Disorders at Tertiary Care Level in India. Pharmacoecon Open. 2018;2(2):179–190. doi: 10.1007/s41669-017-0041-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qazi Arisar FA, Kamran M, Nadeem R, & Jafri W. Impact of severity of chronic liver disease on health-related economics. Hepatitis Monthly. 2020; 20(6). 10.5812/hepatmon.97933 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ratcliff C, Thyle A, Duomai S, Manak M. Poverty reduction in India through palliative care: A pilot project. Indian J Palliat Care. 2017; 23(1): 41–45. 10.4103/0973-1075.197943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

A text file of the search strategies used in our systematic review.

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting information files.