Abstract

Purpose

Recent years have seen an increased awareness of sarcopenia in the cross field of osteoporosis and sarcopenia. The goal of this study was to evaluate current bibliometric characteristics and the status of cross-sectional studies between osteoporosis and sarcopenia.

Methods

Publications related to osteoporosis and sarcopenia published between January 2000 and November 2022 were extracted from the Web of Science Core Collection; bibliometric and visualization were performed by Microsoft Office Excel, VOSviewer, Citespace, and R.

Results

A total of 1128 documents written by 5791 authors from 1758 organizations in 62 countries and published in 405 journals were identified. USA was the leading country with the highest publication and total citation. University of Melbourne contributed the most publications, while Tufts University had the largest citations. Osteoporosis International was the most influential journals in this field with the highest publications, citations and H index. Cooper C was the most influential author, who published the 20 studies, had the highest local citations and the highest H index. The keywords were classified into 6 clusters: Cluster 1 (aging), Cluster 2 (frailty) and Cluster 3 (osteosarcopenia).

Conclusion

Our bibliometric results revealed that the global osteoporosis and sarcopenia-related research increased rapidly from 2000 to 2022, suggesting it was a promising area of research for the future. The future trends in the cross field of sarcopenia and osteoporosis would be the molecular mechanisms of crosstalk between muscles and bones, safety and efficacy interventions with a dual effect on muscle and bone and osteosarcopenia.

Keywords: osteoporosis, sarcopenia, bibliometric analysis, CiteSpace, VOSviewer

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a degenerative systemic skeletal disease characterized by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue.1 With advancing age, especially for the postmenopausal women, the dynamic balance between bone formation and resorption is disrupted and reversed which ultimately leads to osteoporosis.2 Under most circumstances, osteoporosis is a silent and asymptomatic disease.3 However, the increase of bone fragility caused by osteoporosis increases the risk of fragility fractures (osteoporotic fractures), which has imposed a substantial burden on individuals, families and society due to the high mortality and morbidity rates.4 Meanwhile the researchers are coming to the realization that osteoporosis is not the only risk factor for fractures since the low bone mass can no longer explain the dramatic increase in fracture risk with advancing aging.5,6 It is now widely accepted that identifying those at risk for fragility fractures requires a more sophisticated approach than a simple bone mass-based approach.7 As a result of this appreciation, fracture risk calculators like FRAX have been developed, which take elements other than bone mass into account.8,9 Such calculators are a significant advance, but still imperfect, as fragility fractures do occur in some individuals who are currently identified as low risk.10 In recent years, the role of muscle, another important component of the motion system, in falls and fractures has gradually been recognized.11,12 The loss of muscle mass, strength, and function is a fundamental cause of and contributor to disability in older people, which refers to the sarcopenia.13–15

Sarcopenia was initially defined as the age-related loss of muscle mass in 1989, which has gradually expanded to include the muscle mass, muscle strength, and physical performance.16 However, there is no widely accepted worldwide consensus on sarcopenia as the Europe and Asia have launched their own consensus, respectively.15,17 As with osteoporosis, sarcopenia primarily affects the older population, and its prevalence increases with increasing age.18 Approximately 30% of people aged 65 and older are reported to suffer from sarcopenia, while it can reach as high as 50% to 60% in people aged 80 and older.15 Consequently, the coexisting osteoporosis and sarcopenia in the elderly population is pretty common.19,20 Initially, it was believed that osteoporosis and sarcopenia were two separate diseases that existed in tandem.21 While more and more evidence indicated that osteoporosis and sarcopenia tend to coexist more frequently than expected, which was also not happened by chance.22,23 Clinically, osteoporosis increases the risk of developing sarcopenia and vice versa.24 Moreover, the coexistence of osteoporosis and sarcopenia exacerbated negative health outcomes which has been described as a hazardous duet.23,25 Pathologically, osteoporosis and sarcopenia share the common biological pathways (at least in part) such as aging, inflammation, hormonal and nutritional deficits.26–28 Furthermore, bone and muscle are found to be closely related both anatomically and metabolically, and possess a number of chemical and metabolic properties that are closely related.11,29,30 For instance, irisin, a cytokine secreted by skeletal muscle, has dual effect on bones and muscles.31,32 Consequently, the cross-sectional studies between these two diseases are becoming more and more popular. Some researchers proposed that osteoporosis and sarcopenia should be considered as an only entity: osteosarcopenia.33,34

However, a few studies have analyzed and summarized osteoporosis and sarcopenia study characteristics and topics. Most recently, Yu et al conducted a meta-analysis which included 56 studies, and highlighted the importance of sarcopenia screening for those at risk of osteoporosis, and vice versa.24 And Laskou et al only focus on the osteosarcopenia in their review.20 On the other hand, the traditional review cannot provide an overall view of a specific field over time. Thus, previous studies have not fully addressed how osteoporosis and sarcopenia have evolved and what the current status is. While bibliometric analysis, as an emerging subfield of library and information science, provides a quantitative and qualitative method to determine research trends and identify frontiers in a field visually.35 A wide range of fields have been using it recently for analyzing published literature, which include the osteoporosis and sarcopenia, respectively.36–38 However, within the cross field of osteoporosis and sarcopenia, the bibliometric characteristics have not yet been explored. In this study, we aimed to analyze the literature in the cross field of osteoporosis and sarcopenia from 2000 to 2022 to understand the current trends and topics by using bibliometric methods and to provide a comprehensive overview for researchers to explore this field and perform further studies.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources and Search Strategies

Relevant literature was collected from the Web of Science Core Collection (WoSCC), which is considered one of the most comprehensive and authoritative database platforms. As the concept of sarcopenia was first proposed by Rosenberg in 1989.16 The date of the search was from 1 January 1989 to 30 November 2022. In current study, the search terms were as follows: theme = sarcopenia AND theme = osteoporosis AND publishing year = (1989–2022) AND Document types = (ARTICLE OR REVIEW) AND Language = (English). Once the retrieval had been completed, the bibliometric data of retrieved literature were downloaded as “full record and cited reference” from WoSCC database for further analysis. The bibliometric data include the publishing year, title, author names, nationalities, affiliations, abstract, keywords, name of journals, and H-index.

Bibliometric Analysis and Visualization

Following the screening and extraction of relevant data from the final articles included, two authors independently screened and extracted articles’ publication dates, authors, countries, regions, institutions, journals, keywords, citation frequency, H-index, etc. After data collection, a visual analysis was performed using Microsoft Office Excel 2019, CiteSpace 5.8.R3, and VOSviewer 1.6.18, along with the R package Bibliometric.39–41 For instance, Microsoft Office Excel 2019 was used to analyze the descriptive bibliometric indicators, including the annual number of publications, countries, authors, institutions, journals, keywords, and citations. While the VOSviewer and R package Bibliometric were used to analyze the co-occurrence, co-authorship and co-citation of countries, organizations, and authors. For the CiteSpace, the burst-detection function of it was utilized to identify the keywords and references with strong citation bursts, which can serve as signs of hot spots and research trends in different periods.

Results

Trends in Global Publications

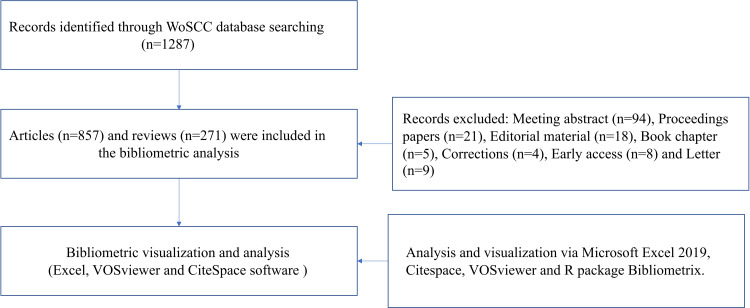

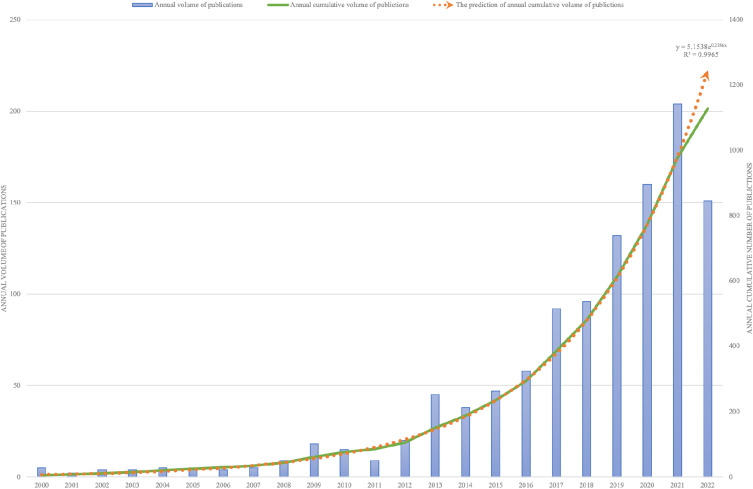

According to the search criteria, a total of 1287 documents were retrieved from the year of 1988 to 2022. Subsequently, 1287 of documents were identified by excluding the meeting abstract (94), proceedings papers (21), editorial material (18), book chapter (5), corrections (4), early access (8) and letter (9). Finally, 1128 documents written by 5791 authors from 1758 organizations and published in 405 journals were identified (Figure 1). Among them are 857 articles (76%) and 271 reviews (24%). As shown in Figure 2, prior to 2000, the research on sarcopenia associated with osteoporosis received little attention. After 2000, global literature has been increasing steadily over time with an annual growth rate of 17.54%. According to the annual publications, two stages could roughly be distinguished. During the first phase (2000–2012), fewer than 20 documents were published per year. While in the second stage (2013–2022), there was a rapid increase in the number of published articles and it peaked in 2021 with 204 documents (18.1%). To predict the future global literature trend, a predicted growth model equation was established by using Microsoft Excel 2019: y = 5.1538e0.2386x, R² = 0.9965 (x means the year and y means the predicted number of studies per year). As 2022 came to an end, 151 articles have been published, which seemed that it could not meet the expected number of publications. Overall, these results demonstrate the growing attention and rapid development of research into sarcopenia-associated osteoporosis.

Figure 1.

Workflow diagram of this study.

Figure 2.

The number of publications about sarcopenia and osteoporosis from 2000 to 2022.

Analysis of Distribution of Countries

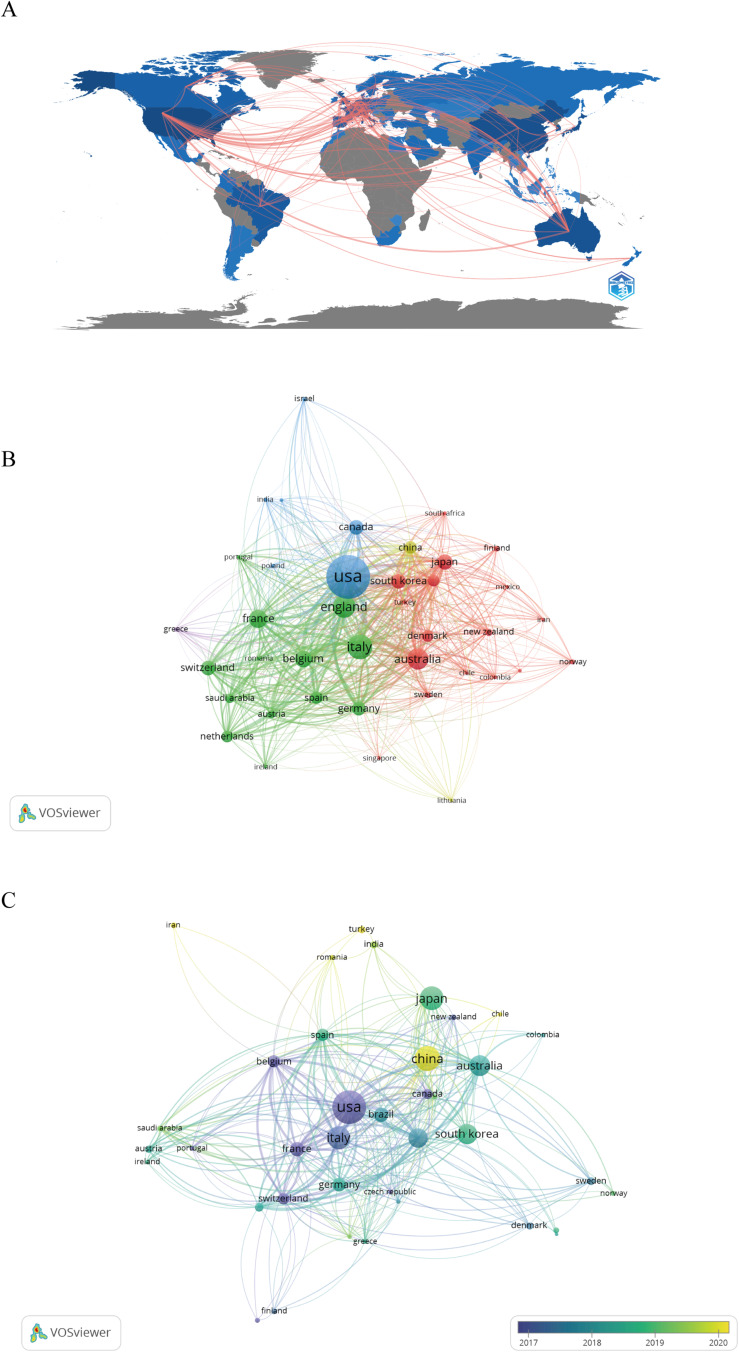

A total of 62 countries contributed publications related to sarcopenia and osteoporosis. During the past 22 years, USA has dominated this field of research with regard to the number of publications, citations and collaborations. In terms of publications, the USA was the top country (248, 21.99%), followed by China (148, 13.13%), Japan (136, 12.06%), Italy (129, 11.44%) and Australia (109, 9.66%). In terms of total citations of publications, USA also had significant advantages with a total citation of 14,556, followed by Italy (5365), England (4561), Australia (4003) and France (3236). In terms of cooperation between countries, the USA is also the most cooperative, which worked closely with several countries such as Italy, Australia, England, and China. As shown in Figure 3, in this field, research is mainly conducted in developed countries such as USA and the European countries which also work closely together. However, in the past three years, the main countries of research have gradually shifted from the USA and Europe to the Asian countries, especially China (Figure 3C), probably due to its aging population.

Figure 3.

The analysis of countries. (A) Heat map showing the distribution and cooperation in the world. (B) Citation of countries, the size of the nodes represents the number of citations. (C) Number of national publications. The size of nodes is determined by the publication numbers. The color indicates the average appearing year.

Analysis of Institutions and Authors

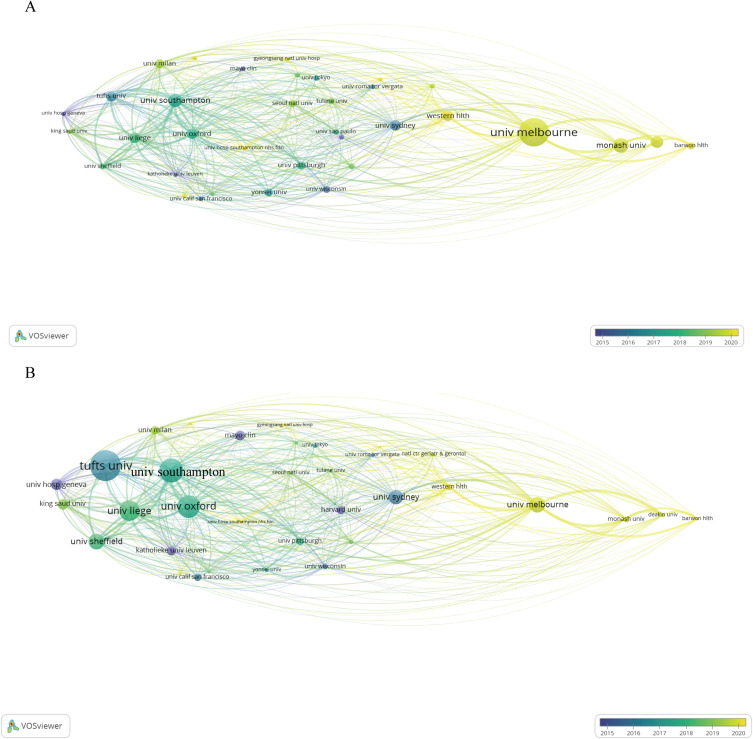

A total of 1758 institutions worldwide got involved. There were 35 organizations with at least 10 publications and the top 10 productive institutions published more than 20 publications which was summarized in Table 1. In terms of publications, University of Melbourne is ranked first, with 65 documents and 1358 citations, followed by Monash University (34 publications, 527 citations) and University of Southampton (30 publications, 2084 citations) (Figure 4A). However, in terms of total citations of publications, as shown in the Figure 4B, Tufts University ranks the first (22 publications, 2649 citations), followed by University of Southampton, and University of Oxford (24 publications, 1962 citations). It appears that the publications of these productive institutions did not match with their citations. However, when the timing of publication was taken into account, we found that most of these high productive institutions are emerging research institutions in the recent years when compared with the institutions with high citations. The citations of high productive institutions may increase gradually over time. The collaboration network between institutions also shows that there is strong cooperation relationship between institutions with high productions and high citations, respectively. Such as collaboration between University of Melbourne and Monash University with high productions, Tufts University and University of Southampton with high citations.

Table 1.

The General Information of the Top 10 Productive Institutions

| Institutions | Country | Publications | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| University of Melbourne | Australia | 65 | 1358 |

| Monash University | Australia | 34 | 527 |

| University of Southampton | England | 30 | 2084 |

| Deakin University | Australia | 27 | 356 |

| University of Liege | Belgium | 25 | 1763 |

| Western Health | Canada | 25 | 544 |

| University of Oxford | England | 24 | 1962 |

| The University of Sydney | Australia | 24 | 1239 |

| Tufts University | USA | 22 | 2649 |

| University of Milan | Italy | 21 | 732 |

Figure 4.

Coauthorship of institutions in sarcopenia and osteoporosis. (A) The size of the nodes represents the number of publications, the color indicates the average appearing year. (B) The size of the nodes represents the number of citations, the color indicates the average appearing year.

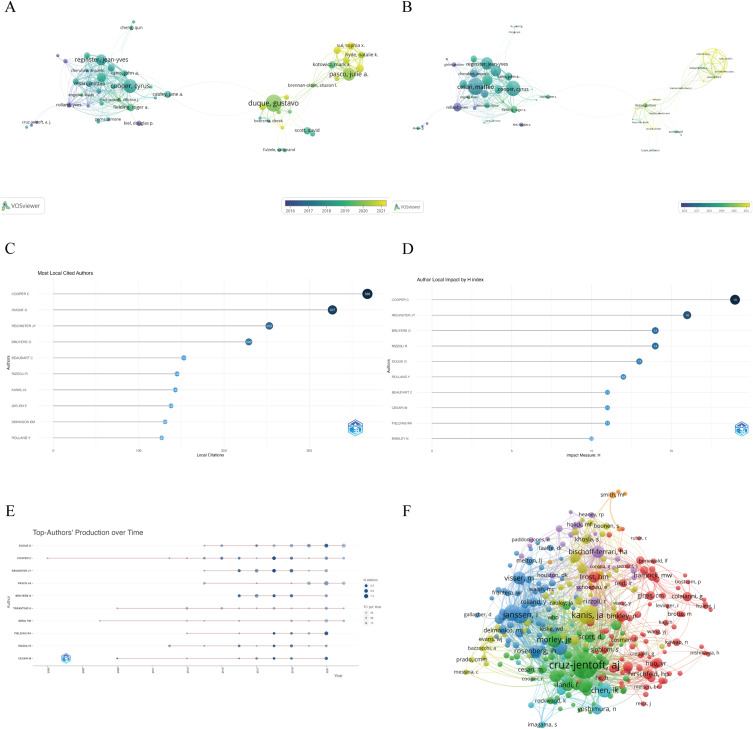

A total of 5791 authors participated in the studies. The characters about citation and number of publications of the most productive 10 authors focusing on sarcopenia and osteoporosis were summarized in Table 2. Among the top 10 authors, 149 publications were published, accounting for 13% of all publications in this area. As an index of an author’s contribution, the number of citations is crucial. In the current study, five authors have been cited more than 1000 times: Cesari M (citation = 1814), Cooper C (citation = 1627), Reginster JY (citation = 1359), Bruyere O (citation = 1196) and Rizzoli R (citation = 1121) (Figure 5A and B). Furthermore, the H index, local citations and publications over time of the top 10 authors were also analyzed via R package bibliometrix and shown in Figure 5. On the basis of the above, Cooper C was the most influential author in the field, who published the 20 studies, had the highest local citations of 368 and the highest H index of 19. Cooper C was also the researcher who has been following this field for the longest time (Figure 5E). Co-cited authors are those who are also cited by other papers and constitute a co-citation relationship. Figure 5F shows a network map of co-cited authors. Cruz-Jentoft is the most frequently co-cited author with 680 citations, followed by Kanis J (citation = 331) and Janssen I (citation = 266).

Table 2.

The General Information of the Top 10 Productive Authors

| Authors | Country | Institutions | Publications | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cauley JA | USA | University of Pittsburgh | 10 | 476 |

| Scott D | Australia | Monash University | 11 | 327 |

| Fielding RA | USA | Tufts University | 11 | 750 |

| Rizzoli R | Switzerland | Geneva University Hospitals and Faculty of Medicine | 11 | 1121 |

| Tarantino U | Italy | University of Rome Tor Vergata | 12 | 223 |

| Bruyere O | Belgium | University of Liege | 14 | 1196 |

| Reginster JY | Belgium | University of Liege | 16 | 1359 |

| Pasco JA | Australia | Deakin University | 19 | 254 |

| Cooper C | England | University of Southampton | 20 | 1627 |

| Duque G | Australia | The University of Sydney (2007–2022) | 25 | 525 |

Figure 5.

The analysis of authors. (A) The size of the nodes represents the number of publications, the color indicates the average appearing year. (B) The size of the nodes represents the number of citations, the color indicates the average appearing year. (C) The most local cited authors. (D) H index of top 10 authors. (E) The publication over time of top 10 productive authors. (F) Network map of co-cited authors.

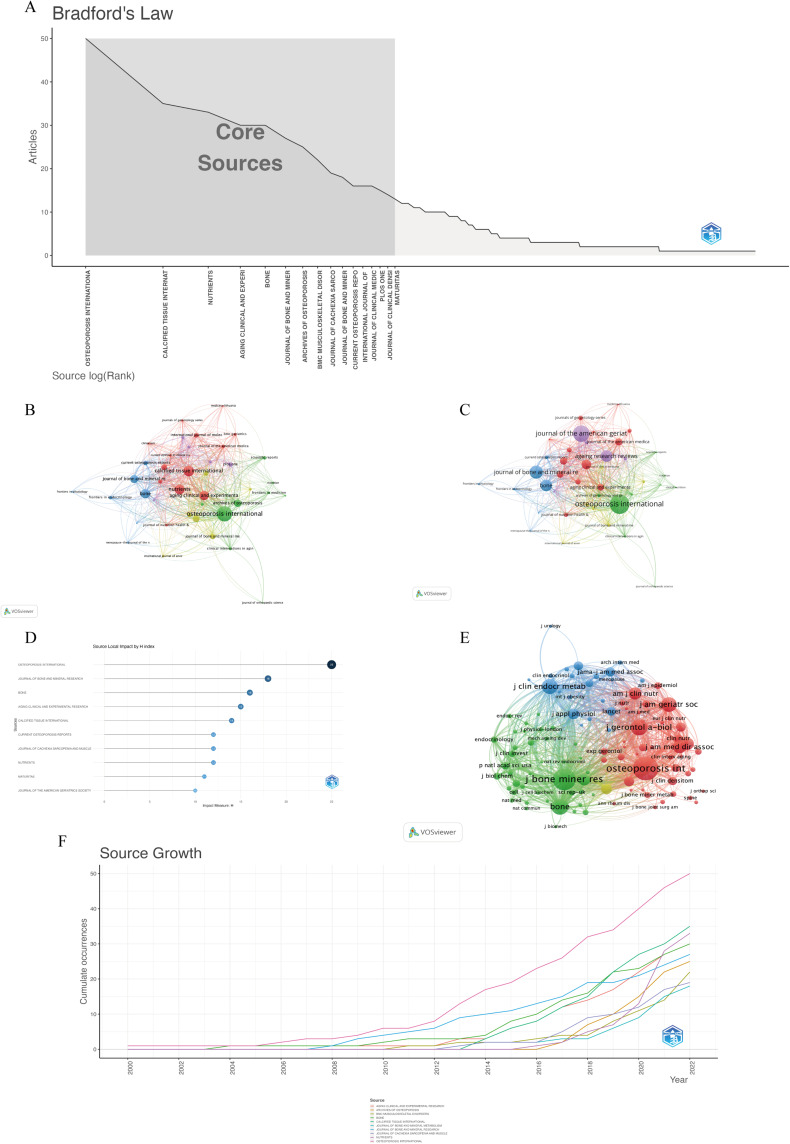

Analysis of Journals

All documents were published in 405 journals. Among them, 40 journals had at least 5 publications. According to the Bradford’s Law, 16 journals have been identified as core journals which were summarized in Table 3, Figure 6A. However, in terms of citations, there were still some journals were not identified as the core journals with high citations (Figure 6C), such as Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (citation = 1699, production = 11), Ageing Research Reviews (citation = 1195, production = 10) and Journal of the American Medical Directors Association (citation = 717, production = 11). To better illustrate the impact of these journal in this field of sarcopenia and osteoporosis, the H index and dynamic publications of top journals are also shown in Figure 6D and F. Taken together, Osteoporosis International is the most influential journals in this field with the highest publications of 50 (Figure 6B), the highest citations of 2028 and the highest H index of 25. The co-citation relationship between journals was visualized were also shown in the Figure 6E, Osteoporosis International also ranks the first of 5959 co-cited journals, followed by Journal of Bone and Mineral Research and BONE.

Table 3.

The General Information of Identified Core Journals in the Field of Sarcopenia and Osteoporosis

| Journal | Documents | Citations |

|---|---|---|

| Journal of Clinical Medicine | 16 | 58 |

| Archives of Osteoporosis | 25 | 178 |

| International Journal of Molecular Sciences | 16 | 183 |

| BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders | 22 | 231 |

| Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism | 18 | 260 |

| Journal Of Clinical Densitometry | 14 | 281 |

| PLOS ONE | 15 | 300 |

| Current Osteoporosis Reports | 16 | 362 |

| Nutrients | 33 | 505 |

| Aging Clinical and Experimental Research | 30 | 642 |

| Maturitas | 13 | 659 |

| Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle | 19 | 758 |

| Calcified Tissue International | 35 | 964 |

| Bone | 30 | 1173 |

| Journal of Bone and Mineral Research | 27 | 1355 |

| Osteoporosis International | 50 | 2028 |

Figure 6.

Analysis of journals. (A) Core journals according to the Bradford’s Law. (B) The analysis of publications. The size of the nodes represents the number of publications. (C) The analysis of citations. The size of the nodes represents the number of citations. (D) The H index of top 10 journals. (E) The co-citation relationship between journals. (F) The dynamic publications of top journals.

Analysis of Citation and Co-Citation

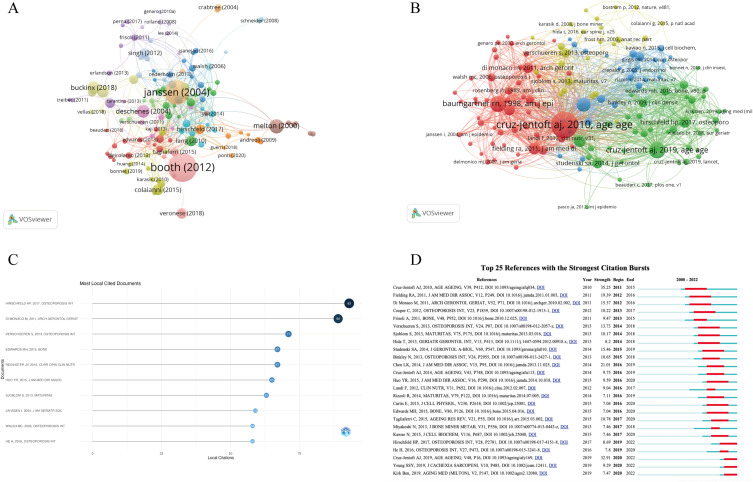

A total of 176 documents in this field have more than 50 global citations (Figure 7A). “Lack of Exercise Is a Major Cause of Chronic Diseases” (citation = 1166),42 “The Healthcare Costs of Sarcopenia in the United States” (citation = 885),43 and “Epidemiology of Sarcopenia” (citation = 865) ranked the top three.44 To better reflect the trends within the field, the most local cited documents were also analyzed and summarized in Table 4, Figure 7C. 138 documents have been cited by the included documents for more than 20 times. “Osteosarcopenia: where bone, muscle, and fat collide” was the most local cited document with citations of 93,34 followed by “Prevalence of sarcopenia and its association with osteoporosis in 313 older women following a hip fracture” with citations of 89,45 and “Sarcopenia and its relationship with bone mineral density in middle-aged and elderly European men” with citations of 71.46 Moreover, co-cited references were also analyzed and summarized in Table 5, Figure 7B. The European consensus on definition and diagnosis of sarcopenia ranks the top two.17,47 In addition, a citation burst also indicates the interest of researchers in a particular domain in a period. Between 2000 and 2022, the strongest citation bursts in the field were identified via CiteSpace (Figure 7D). During the last three years, the strongest citation was “Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis”,17 followed by “Sarcopenia and its association with falls and fractures in older adults: A systematic review and meta‐analysis”,14 and “Osteosarcopenia: where bone, muscle, and fat collide”.34

Figure 7.

The analysis of citation and co-citation. (A) Network map of global citations of documents. (B) Network map of co-cited references. (C) The top 10 local cited documents. (D) The 25 references with strongest citation bursts between 2000 to 2022; the red bars represent the duration of bursts.

Table 4.

The Top 10 Local Cited Documents in the Field of Sarcopenia and Osteoporosis

| Title | Journal | Year | Local Citations | Global Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteosarcopenia: where bone, muscle, and fat collide | Osteoporosis International | 2017 | 93 | 203 |

| Prevalence of sarcopenia and its association with osteoporosis in 313 older women following a hip fracture | Archives of Gerontology And Geriatrics | 2011 | 89 | 172 |

| Sarcopenia and its relationship with bone mineral density in middle-aged and elderly European men | Osteoporosis International | 2013 | 71 | 169 |

| Osteoporosis and sarcopenia in older age | Bone | 2015 | 67 | 166 |

| Osteoporosis and sarcopenia: two diseases or one? | Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition And Metabolic Care | 2016 | 67 | 123 |

| Phenotype of osteosarcopenia in older individuals with a history of falling | Journal of The American Medical Directors Association | 2015 | 65 | 112 |

| Relationship between postmenopausal osteoporosis and the components of clinical sarcopenia | Maturitas | 2013 | 63 | 126 |

| The healthcare costs of sarcopenia in the United States | Journal of The American Geriatrics Society | 2004 | 59 | 885 |

| Sarcopenia in premenopausal and postmenopausal women with osteopenia, osteoporosis and normal bone mineral density | Osteoporosis International | 2006 | 58 | 151 |

| Relationship of sarcopenia and body composition with osteoporosis | Osteoporosis International | 2016 | 58 | 112 |

Table 5.

The Top 10 Co-Cited References in the Field of Sarcopenia and Osteoporosis

| Title | Journal | Author | Year | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People | Age Ageing | Cruz-Jentoft AJ | 2010 | 364 |

| Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis | Age Ageing | Cruz-Jentoft AJ | 2019 | 174 |

| Epidemiology of Sarcopenia among the Elderly in New Mexico | American Journal of Epidemiology | Baumgartner RN | 1988 | 170 |

| Sarcopenia in Asia: consensus report of the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia | Journal of the American Medical Directors Association | Chen LK | 2014 | 135 |

| Frailty in Older Adults: Evidence for a Phenotype | The Journals of Gerontology: Series A | Fried LP | 2001 | 108 |

| Sarcopenia: An Undiagnosed Condition in Older Adults. Current Consensus Definition: Prevalence, Etiology, and Consequences. International Working Group on Sarcopenia | Journal of the American Medical Directors Association | Fielding RA | 2011 | 104 |

| Low Relative Skeletal Muscle Mass (Sarcopenia) in Older Persons Is Associated with Functional Impairment and Physical Disability | Journal of the American Geriatrics Society | Janssen I | 2002 | 94 |

| Osteosarcopenia: where bone, muscle, and fat collide | Osteoporosis International | Hirschfeld HP | 2017 | 93 |

| The FNIH Sarcopenia Project: Rationale, Study Description, Conference Recommendations, and Final Estimates | The Journals of Gerontology: Series A | Studenski SA | 2014 | 91 |

| Prevalence of sarcopenia and its association with osteoporosis in 313 older women following a hip fracture | Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics | Di Monaco M | 2011 | 89 |

Analysis of Keywords

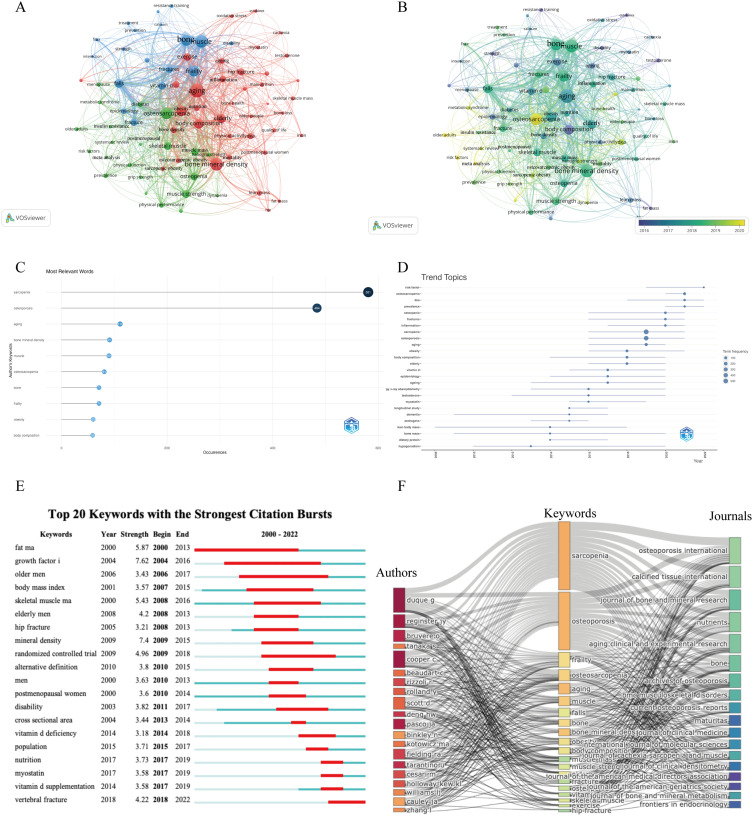

A total of 1850 author keywords were extracted from 1128 documents. Sarcopenia and osteoporosis, which have the highest frequency of occurrences of 581 and 484, were excluded from the network analysis in order to reveal the evolution of keywords. The co-occurring author keywords, with a minimum occurrence of 5 times, were identified and visualized in VOSviewer software (Figure 8A and B). The author keywords with the highest density are aging, bone mineral density, muscle, osteosarcopenia, bone, frailty, obesity, and body composition (Figure 8C). In addition, we classified the keywords into 3 clusters: Cluster 1 (aging), Cluster 2 (frailty) and Cluster 3 (osteosarcopenia) (Figure 8A). For the Cluster 1 (red), it main focuses on the pathologies and molecular mechanisms between sarcopenia and osteoporosis. Keywords such as bone mineral density, muscle mass, inflammation, irisin, oxidative stress, myostatin and testosterone were frequently occurred. The Cluster 2 (blue) frailty mainly focuses on clinical connections and treatments in sarcopenia and osteoporosis, which include vitamin D, calcium, treatment, resistance training. The Cluster 3 (green) osteosarcopenia is a newly defined condition characterized by osteoporosis and sarcopenia occurring simultaneously. The evolution of keywords over time was also shown in Figure 8B. Keywords appearing in blue are relatively old, whereas those appearing in yellow are more recent. As shown in Figure 8, the research trends in this field have gradual shifted from cluster 1, 2 to 3. Besides, the trend of the keyword from 2000 to 2022 was further analyzed via R package bibliometric (Figure 8D), which also indicated that researchers are more interested in osteosarcopenia in the recent years. Additionally, CiteSpace’s burst detection algorithm was used to detect the burst of keywords. The top 20 keywords with the highest burst strength are shown in Figure 8E.

Figure 8.

The analysis of keywords. (A and B) Network visualization of the keywords co-occurrence analysis. The size of the nodes represents frequency. The color indicates the average appearing year in (B). (C) The frequency of the top 10 keywords. (D) The trend topics based on keywords generated by R package Bibliometric. (E) Top 20 keywords with strongest citation bursts between 2000 to 2022; the red bars represent the duration of bursts. (F) Three-field graphs of authors, keywords, and journals.

Three-field graphs were constructed to observe the relationship between authors, keywords, and journals (Figure 8F). Keyword results were in line with the above analysis. Duque G, Reginster JY and Cooper C have relatively strong links with the keywords “sarcopenia” and “osteoporosis” for the authors. The strongest links to those two keywords were then discovered to be Osteoarthritis International and Calcified Tissue International. Meanwhile, Duque G contributed the most links to the trend topic “osteosarcopenia”, showing that he is the leading author on this topic.

Discussion

As two skeletal muscle diseases, sarcopenia and osteoporosis, that occur predominantly in the elderly, have bring a heavy burden on the society.45,48 With a worldwide population aging, the incidence of two diseases is gradually increasing which has attracted the attention of researchers. Accompanied by a daily increasing number of studies, it is crucial for researchers to keep up with the newest understandings and findings in this field, as well as the comprehensive understanding of the historical lineage. However, a traditional systematic review cannot provide an overall view of a specific field over time. On the contrary, bibliometrics, an independent and newborn discipline, could review the large amount of literature quantitatively over time and investigate potential hotspots that many researchers are interested in.49 In the current study, we clearly outlined the trend, progress and hotspots in the cross field of sarcopenia and osteoporosis. Via bibliometric analysis, our results identified the most influential authors, institutions, journals, publications, and keywords in sarcopenia and osteoporosis. Researchers who are interested in this field could get directions and suggestions from this document, enabling them to gain an easier and deeper understanding of the sarcopenia and osteoporosis.

Although sarcopenia had been proposed in 1989, the research on sarcopenia and osteoporosis had not gained attention until 2000. Afterwards, the annual publications of this field have gradually increased. Especially in 2013, it was a turning point, where the volume of publications doubled. Probably due to the several proposed consensuses on the definition and diagnosis of sarcopenia.15,47 After that, the annual publications grown rapidly, peaking in 2021 with a publication of 204. As can be seen, sarcopenia and osteoporosis are gaining increasing attention among the researchers, and the literature in this field is likely to continue to grow.

Regarding national contributions, a total of 62 countries contributed publications related to sarcopenia and osteoporosis. Among them, USA holds an overwhelmingly dominant position, with the highest number of publications and citations, and strong collaborations with other countries, such as Italy, Australia, England, and China. Through the cooperation network, the researches were mainly conducted in developed countries such as USA, European countries and Australia which also worked closely together. As two strongly age-related diseases, together with the aging population in developed countries, it is not surprising that these developed countries are intensively studying sarcopenia and osteoporosis. While in the recent years, Asian countries such as China, Japan and Korea have gradually contributed a significant number of publications in this field which may also be due to the gradual aging of the population in these countries. Especially for the China, the most populous country in the world, the total number of elderly people aged 60 and above was 264 million in 2020, accounting for 18.7% of the total population.50 The number of publications from China would be expected to continue to increase in the future. In terms of institutions, the top 10 influential institutions were all from developed countries which was in line with the analysis of national contributions. Among them, University of Melbourne in Australia has the most publications, while Tufts University in USA has the most citations. The two institutions may have strong academic foundations in this field, making them a good source for up-to-date information. Notably, the high productive institutions are emerging research institutions in the recent years which may represent the leading-edge research, while the institutions with more citations could be considered as the foundation in the field of sarcopenia and osteoporosis.

For the analysis of authorships, several authors had made significant contributions to the field and half of them are members of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP), which had published two European consensus on definition and diagnosis of the sarcopenia.17,47 While the rest authors took their place in the association of osteoporosis. For instance, Cruz-Jentoft, the most frequently co-cited author in the current study, was the leader of European consensus on sarcopenia. Cesari M, Cooper C and Bruyere O, who had been cited for more than 1000, also participated in the consensus.17,47 On the other hand, Kanis JA, Cooper C, Rizzoli R and Reginster JY were the member of Scientific Advisory Board of the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis (ESCEO).51 As the cross field between sarcopenia and osteoporosis, Cooper C was considered as the most influential author in terms of the H index, local citations and publications over time. He leaded multiple internationally competitive programmes of research into the epidemiology of musculoskeletal disorders, most notably osteoporosis and sarcopenia.52,53 While Gustavo D had published the most publications in this field but received the less citations. He and his colleagues first proposed the osteosarcopenia, a trend topic in sarcopenia and osteoporosis, to describe a group of older individuals who have osteoporosis and sarcopenia.34 It is reasonable to believe that his influence in this field will continue to increase in the future. We also identified the core journals in sarcopenia and osteoporosis. Osteoporosis International was the most influential journals in this field with the highest publications, highest citations and highest H index. Cooperative research and publishing may take advantage of these various results in the future, as well as the access to the most advanced understanding of sarcopenia and osteoporosis.

To better understand the evolutionary trends in this field, we conducted the analysis the documents and keywords. Based on the clusters of the keywords, research in this area was divided into three main sections. Cluster 1 aging, which was the beginning of research in this field, represents the pathologies and molecular mechanisms between sarcopenia and osteoporosis. As two age-related diseases, aging is both the shared clinical feature and common pathogenesis in sarcopenia and osteoporosis.11,29 Followed by the changes in body composition, the loss of normal bone and muscle mass are core pathologies of osteoporosis and sarcopenia, respectively.54 Keywords such as bone mineral density and muscle mass were frequently occurred. However, the lack of recognition of sarcopenia in the early stage made the association with osteoporosis weak, especially the definition and diagnosis of the sarcopenia. The establishment of two consensus on sarcopenia published by International and European Working Group, which were the references with the strongest citation bursts in the early stage, laid the foundation for later research.47,55 Thereafter, a more in-depth study of the molecular mechanisms of these two diseases had emerged. Crosstalk between muscles and bones has historically been considered to be a mechanical phenomenon. However, the emerging notion that bone and muscle both function as secretory endocrine organs has challenged this dogma.29,33,34,56 While sarcopenia and osteoporosis are two most representative diseases. The research on molecular mechanisms may be conductive to identifying potential novel therapies for osteoporosis and sarcopenia.28,30 The representative keywords were inflammation, irisin, oxidative stress, myostatin and testosterone. Meanwhile, the references with the strongest citation bursts at this stage were about the cross talk between muscle and bone.11,57 However, these keywords had lower frequency of occurrence as well as centrality, which indicated that there was no consensus in this area of research and further research is still needed.

Cluster 2 frailty mainly focuses on clinical connections and treatments in sarcopenia and osteoporosis. As an important geriatric syndrome, frailty is characterized by low strength, slow walking speed, low activity, falls and fractures.58 The decrease in muscle and bone mass and the features of sarcopenia and osteoporosis were closely linked to these adverse outcomes, especially the falls and the fractures.20,27,58 It would seem to be normal for many older individuals, especially, to suffer from concurrent osteoporosis and sarcopenia, which increases their risk of complications and further increases their risk for mortality.22,23,59 For the treatments or the preventions, as shown in Figure 7, there was no novel methods for the sarcopenia and osteoporosis. Exercise and supplemental nutrition continued to be the primary treatments for this condition.25,60–62 There has been substantial research showing that exercise, particularly resistance exercise, significantly improves muscle and bone mass, increases muscle strength, reduces or delays functional limitations and reduces the risk of falls or fractures among older people.61,63,64 Both dietary vitamin D and calcium supplementation were recommended for the sarcopenic and osteoporotic patients.52,65–67 The keywords “vitamin d deficiency”, “nutrition” and “vitamin d supplementation” still had the strongest citation bursts during 2014 to 2019. However, this also reflected the truth that the pharmacological approach to the sarcopenia and osteoporosis was still missing, unlike osteoporosis which already had several available medications.68,69 There is a need of further researches to develop the pharmaceutical treatments that have dual effects on muscle and bone.

Cluster 3 osteosarcopenia was the hot topics in recent years, as shown in the Figure. Within the field of sarcopenia and osteoporosis, the document “Osteosarcopenia: where bone, muscle, and fat collide” published by Gustavo D in Osteoporosis International had received the most citations, which also had the strongest citations bursts since 2019 to 2022.34 Due to the high prevalence of concomitant sarcopenia and osteoporosis and the crosstalk between muscle and bone, the researchers had gradually recognized the concomitant sarcopenia and osteoporosis as a single definition of osteosarcopenia. While actually, as early as 2013, Binkley et al had already proposed to term the combination of sarcopenia and osteoporosis as dysmobility syndrome, analogous to the approach taken with metabolic syndrome.70 However, perhaps due to the lack of cognition about sarcopenia or the fact that this concept was too broad, the concept had not received much attention at that time. A growing number of clinical studies had shown that sarcopenia can increase the possibility of developing the osteoporosis vice versa.48,71–73 Meanwhile, the combination of these two diseases exacerbates the risk of falls, fractures, institutionalization, and poor quality of life.21,27,74,75 Together with the achievements of crosstalk between the bone and muscle, at present, the hotspots for sarcopenia and osteoporosis have shifted from the intersection of two diseases to the point of convergence: osteosarcopenia.33,74 The concept of osteosarcopenia highlighted the identical roles of muscle and bone in the pathogenesis as well as in the treatments. While with it comes, little is known about the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, outcomes, and management strategies of osteosarcopenia, which may require further in-depth study in the future.

There were some limitations to our study. Firstly, it is important to note that all publications included in our study were sourced from SCI-E, which means that many studies that were not included in SCI-E may have been excluded. Nevertheless, SCI-E is a widely used database in the world which includes a lot of high-quality literature. Secondly, research and review articles in English were the only ones collected in this study. The articles published in non-English languages or articles that were not research/review articles were not included in this study, which may result in some omissions in the study. Lastly, due to the fact that new research is updated every day, some highly cited studies that have been published in recent years may be overlooked because their short publication time may leave them relatively unnoticed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study was the first to analyze the global research trends for the cross field between sarcopenia and osteoporosis over the past two decades through bibliometric analysis in a scientifically rigorous and comprehensive manner. In this study, we have systematically summarized the global publication trends and helped researchers identify the key authors, institutions, and journals that have contributed to this field and pave the way for further research. Moreover, through the keyword and co-citation analysis, future trends in the cross field of sarcopenia and osteoporosis would be the molecular mechanisms of crosstalk between muscles and bones, safety and efficacy interventions with a dual effect on muscle and bone and osteosarcopenia.

Ethical Statement

No ethical committee approval was required because the data used in this study were obtained from published articles.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Lane JM, Russell L, Khan SN. Osteoporosis. Clin Orthop Relat R. 2000;372:139–150. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200003000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armas LAG, Recker RR. Pathophysiology of osteoporosis new mechanistic insights. Endocrin Metab Clin. 2012;41(3):475–486. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2012.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eriksen EF. Treatment of osteopenia. Rev Endocr Metabolic Disord. 2012;13(3):209–223. doi: 10.1007/s11154-011-9187-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coughlan T, Dockery F. Osteoporosis and fracture risk in older people. Clin Med. 2014;14(2):187–191. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.14-2-187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pisani P, Renna MD, Conversano F, et al. Major osteoporotic fragility fractures: risk factor updates and societal impact. World J Orthop. 2016;7(3):171–181. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v7.i3.171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cauley JA, Cawthon PM, Peters KE, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in older men: the osteoporotic fractures in Men Study (MrOS). J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31(10):1810–1819. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmadzadeh A, Emam M, Rajaei A, Moslemizadeh M, Jalessi M. Comparison of three different osteoporosis risk assessment tools: orai (osteoporosis risk assessment instrument), SCORE (simple calculated osteoporosis risk estimation) and OST (osteoporosis self-assessment tool). Med J Islamic Repub Iran. 2013;28:94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards BJ. Osteoporosis Risk Calculators. J Clin Densitom. 2017;20(3):379–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2017.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanis JA, Harvey NC, Johansson H, Odén A, Leslie WD, McCloskey EV. FRAX Update. J Clin Densitom. 2017;20(3):360–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2017.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bolland MJ, Siu AT, Mason BH, et al. Evaluation of the FRAX and Garvan fracture risk calculators in older women. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26(2):420–427. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis E, Litwic A, Cooper C, Dennison E. Determinants of muscle and bone aging. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230(11):2618–2625. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang M, Liu J, Chen X, Wang X, Chen X. Muscle quality and spine fractures. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13(2):1426–1428. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santilli V, Bernetti A, Mangone M, Paoloni M. Clinical definition of sarcopenia. Clin Cases Mineral Bone Metabol. 2014;11(3):177–180. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yeung SSY, Reijnierse EM, Pham VK, et al. Sarcopenia and its association with falls and fractures in older adults: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019;10(3):485–500. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen LK, Liu LK, Woo J, et al. Sarcopenia in Asia: consensus report of the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(2):95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg IH. Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance. J Nutr. 1997;127(5):990S–991S. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.5.990s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2018;48(1):16–31. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afy169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keevil VL, Romero-Ortuno R. Ageing well: a review of sarcopenia and frailty. P Nutr Soc. 2015;74(4):337–347. doi: 10.1017/s0029665115002037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kirk B, Kuo CL, Xiang M, Duque G. Associations between leukocyte telomere length and osteosarcopenia in 20,400 adults aged 60 years and over: data from the UK Biobank. Bone. 2022;161:116425. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2022.116425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laskou F, Fuggle NR, Patel HP, Jameson K, Cooper C, Dennison E. Associations of osteoporosis and sarcopenia with frailty and multimorbidity among participants of the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13(1):220–229. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards MH, Dennison EM, Sayer AA, Fielding R, Cooper C. Osteoporosis and sarcopenia in older age. Bone. 2015;80:126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee DY, Shin S. Association of sarcopenia with osteopenia and osteoporosis in community-dwelling older Korean adults: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Med. 2021;11(1):129. doi: 10.3390/jcm11010129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pang BWJ, Wee SL, Chen KK, et al. Coexistence of osteoporosis, sarcopenia and obesity in community-dwelling adults – the Yishun Study. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 2021;7(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.afos.2020.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu X, Sun S, Zhang S, et al. A pooled analysis of the association between sarcopenia and osteoporosis. Medicine. 2022;101(46):e31692. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000031692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirk B, Zanker J, Duque G. Osteosarcopenia: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment—facts and numbers. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020;11(3):609–618. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hata R, Miyamoto K, Abe Y, et al. Osteoporosis and sarcopenia are associated with each other and reduced IGF1 levels are a risk for both diseases in the very old elderly. Bone. 2023;166:116570. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2022.116570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greco EA, Pietschmann P, Migliaccio S. Osteoporosis and sarcopenia increase frailty syndrome in the elderly. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:255. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarantino U, Baldi J, Celi M, et al. Osteoporosis and sarcopenia: the connections. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2013;25(Suppl 1):93–95. doi: 10.1007/s40520-013-0097-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.He C, He W, Hou J, et al. Bone and muscle crosstalk in aging. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:585644. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.585644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sasako T, Umehara T, Soeda K, et al. Deletion of skeletal muscle Akt1/2 causes osteosarcopenia and reduces lifespan in mice. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):5655. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-33008-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colaianni G, Cinti S, Colucci S, Grano M. Irisin and musculoskeletal health. Ann Ny Acad Sci. 2017;1402(1):5–9. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holmes D. Irisin boosts bone mass. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11(12):689. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirk B, Saedi AA, Duque G. Osteosarcopenia: a case of geroscience. Aging Med. 2019;2(3):147–156. doi: 10.1002/agm2.12080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hirschfeld HP, Kinsella R, Duque G. Osteosarcopenia: where bone, muscle, and fat collide. Osteoporosis Int. 2017;28(10):2781–2790. doi: 10.1007/s00198-017-4151-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bornmann L, Leydesdorff L. Scientometrics in a changing research landscape. EMBO Rep. 2014;15(12):1228–1232. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang B, Feng C, Li C, Tu C, Li Z. A bibliometric and visualization analysis of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis research from 2012 to 2021. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:961471. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.961471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao Y, Deng Z, Tan H, Jiang T, Chen Z. Bibliometric analysis of the knowledge base and future trends on sarcopenia from 1999–2021. Int J Environ Res Pu. 2022;19(14):8866. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19148866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang L, Jiang J, Li Y, et al. Global trends and hotspots in research on osteoporosis rehabilitation: a bibliometric study and visualization analysis. Frontiers Public Heal. 2022;10:1022035. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1022035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Eck NJ, Waltman L. Software survey: vOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics. 2010;84(2):523–538. doi: 10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen C. Searching for intellectual turning points: progressive knowledge domain visualization. Proc National Acad Sci. 2004;101(suppl_1):5303–5310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307513100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aria M, Cuccurullo C. bibliometrix: an R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J Informetr. 2017;11(4):959–975. doi: 10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Booth FW, Roberts CK, Laye MJ. Comprehensive physiology. Compr Physiol. 2013;2(2):1143–1211. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Janssen I, Shepard DS, Katzmarzyk PT, Roubenoff R. The healthcare costs of sarcopenia in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(1):80–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Melton LJ, Khosla S, Crowson CS, O’Connor MK, O’Fallon WM, Riggs BL. Epidemiology of sarcopenia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(6):625–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04719.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miyakoshi N, Hongo M, Mizutani Y, Shimada Y. Prevalence of sarcopenia in Japanese women with osteopenia and osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Metab. 2013;31(5):556–561. doi: 10.1007/s00774-013-0443-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verschueren S, Gielen E, O’Neill TW, et al. Sarcopenia and its relationship with bone mineral density in middle-aged and elderly European men. Osteoporosis Int. 2013;24(1):87–98. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2057-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010;39(4):412–423. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Monaco MD, Vallero F, Monaco RD, Tappero R. Prevalence of sarcopenia and its association with osteoporosis in 313 older women following a Hip fracture. Arch Gerontol Geriat. 2011;52(1):71–74. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2010.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ellegaard O, Wallin JA. The bibliometric analysis of scholarly production: how great is the impact? Scientometrics. 2015;105(3):1809–1831. doi: 10.1007/s11192-015-1645-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gong J, Wang G, Wang Y, et al. Nowcasting and forecasting the care needs of the older population in China: analysis of data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Lancet Public Heal. 2022;7(12):e1005–e1013. doi: 10.1016/s2468-2667(22)00203-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kanis JA, Cooper C, Rizzoli R, Reginster JY; (IOF) SAB of the ES for C and EA of O (ESCEO) and the C of SA and NS of the IOF. European guidance for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Osteoporosis Int. 2019;30(1):3–44. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4704-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chevalley T, Brandi ML, Cashman KD, et al. Role of vitamin D supplementation in the management of musculoskeletal diseases: update from an European Society of Clinical and Economical Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO) working group. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2022;34(11):2603–2623. doi: 10.1007/s40520-022-02279-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reginster JY, Beaudart C, Al-Daghri N, et al. Update on the ESCEO recommendation for the conduct of clinical trials for drugs aiming at the treatment of sarcopenia in older adults. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33(1):3–17. doi: 10.1007/s40520-020-01663-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He H, Liu Y, Tian Q, Papasian CJ, Hu T, Deng HW. Relationship of sarcopenia and body composition with osteoporosis. Osteoporosis Int. 2016;27(2):473–482. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3241-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fielding RA, Vellas B, Evans WJ, et al. Sarcopenia: an undiagnosed condition in older adults. current consensus definition: prevalence, etiology, and consequences. international working group on sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12(4):249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li G, Zhang L, Wang D, et al. Muscle‐bone crosstalk and potential therapies for sarco‐osteoporosis. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(9):14262–14273. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kawao N, Kaji H. Interactions between muscle tissues and bone metabolism. J Cell Biochem. 2015;116(5):687–695. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cooper C, Dere W, Evans W, et al. Frailty and sarcopenia: definitions and outcome parameters. Osteoporosis Int. 2012;23(7):1839–1848. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-1913-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laskou F, Patel HP, Cooper C, Dennison E. A pas de deux of osteoporosis and sarcopenia: osteosarcopenia. Climacteric. 2022;25(1):88–95. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2021.1951204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Srivastava M, Deal C. Osteoporosis in elderly: prevention and treatment. Clin Geriatr Med. 2002;18(3):529–555. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0690(02)00022-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Landi F, Schneider SM, et al. Prevalence of and interventions for sarcopenia in ageing adults: a systematic review. Report of the International Sarcopenia Initiative (EWGSOP and IWGS). Age Ageing. 2014;43(6):748–759. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Coll PP, Phu S, Hajjar SH, Kirk B, Duque G, Taxel P. The prevention of osteoporosis and sarcopenia in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(5):1388–1398. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Florin A, Lambert C, Sanchez C, et al. The secretome of skeletal muscle cells: a systematic review. Osteoarthr Cartil Open. 2020;2(1):100019. doi: 10.1016/j.ocarto.2019.100019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Giangregorio LM, Papaioannou A, MacIntyre NJ, et al. Too Fit To Fracture: exercise recommendations for individuals with osteoporosis or osteoporotic vertebral fracture. Osteoporosis Int. 2014;25(3):821–835. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2523-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rupp T, Von Vopelius E, Strahl A, et al. Beneficial effects of denosumab on muscle performance in patients with low BMD: a retrospective, propensity score-matched study. Osteoporosis Int. 2022;33(10):2177–2184. doi: 10.1007/s00198-022-06470-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bauer JM, Verlaan S, Bautmans I, et al. Effects of a vitamin D and leucine-enriched whey protein nutritional supplement on measures of sarcopenia in older adults, the PROVIDE study: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(9):740–747. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ganapathy A, Nieves JW. Nutrition and sarcopenia—what do we know? Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1755. doi: 10.3390/nu12061755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vellucci R, Terenzi R, Kanis JA, et al. Understanding osteoporotic pain and its pharmacological treatment. Osteoporosis Int. 2018;29(7):1477–1491. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4476-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Feike Y, Zhijie L, Wei C. Advances in research on pharmacotherapy of sarcopenia. Aging Med. 2021;4(3):221–233. doi: 10.1002/agm2.12168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Binkley N, Krueger D, Buehring B. What’s in a name revisited: should osteoporosis and sarcopenia be considered components of “dysmobility syndrome?”. Osteoporosis Int. 2013;24(12):2955–2959. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2427-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Walsh MC, Hunter GR, Livingstone MB. Sarcopenia in premenopausal and postmenopausal women with osteopenia, osteoporosis and normal bone mineral density. Osteoporosis Int. 2006;17(1):61–67. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1900-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Binkley N, Buehring B. Beyond FRAX®: it’s time to consider “Sarco-Osteopenia”. J Clin Densitom. 2009;12(4):413–416. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2009.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Frisoli A, Chaves PH, Ingham SJM, Fried LP. Severe osteopenia and osteoporosis, sarcopenia, and frailty status in community-dwelling older women: results from the Women’s Health and Aging Study (WHAS) II. Bone. 2011;48(4):952–957. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.12.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huo YR, Suriyaarachchi P, Gomez F, et al. Phenotype of osteosarcopenia in older individuals with a history of falling. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(4):290–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tarantino U, Baldi J, Scimeca M, et al. The role of sarcopenia with and without fracture. Inj. 2016;47:S3–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2016.07.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]