Abstract

Accumulation of incompletely folded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) leads to ER stress, activates ER protein degradation pathways, and upregulates genes involved in protein folding. This process is known as the unfolded protein response (UPR). The role of ER protein folding in plant responses to nutrient deficiencies is unclear. We analyzed Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) mutants affected in ER protein quality control and established that both CALNEXIN (CNX) genes function in the primary root response to phosphate (Pi) deficiency. CNX1 and CNX2 are homologous ER lectins promoting protein folding of N-glycosylated proteins via the recognition of the GlcMan9GlcNAc2 glycan. Growth of cnx1-1 and cnx2-2 single mutants was similar to that of the wild type under high and low Pi conditions, but the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant showed decreased primary root growth under low Pi conditions due to reduced meristematic cell division. This phenotype was specific to Pi deficiency; the double mutant responded normally to osmotic and salt stress. Expression of CNX2 mutated in amino acids involved in binding the GlcMan9GlcNAc2 glycan failed to complement the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 mutant. The root growth phenotype was Fe-dependent and was associated with root apoplastic Fe accumulation. Two genes involved in Fe-dependent inhibition of primary root growth under Pi deficiency, the ferroxidase LOW PHOSPHATE 1 (LPR1) and P5-type ATPase PLEIOTROPIC DRUG RESISTANCE 2 (PDR2) were epistatic to CNX1/CNX2. Overexpressing PDR2 failed to complement the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 root phenotype. The cnx1-1 cnx2-2 mutant showed no evidence of UPR activation, indicating a limited effect on ER protein folding. CNX might process a set of N-glycosylated proteins specifically involved in the response to Pi deficiency.

Calnexin, a lectin chaperone engaged in the folding of N-glycosylated proteins in the ER, participates in primary root adaptation to low-phosphate conditions.

Introduction

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) serves as the major entry point for proteins into the secretory pathway as well as for proteins destined for the plasma membrane (PM). It is estimated that approximately one-third of cellular proteins pass through this organelle (Strasser, 2018). The ER is thus a major site for folding and quality control of proteins involved in numerous cellular processes, including cell wall synthesis, nutrient transport, and PM-based signal transduction (Brandizzi, 2021). The ER harbors two main pathways to assist in protein folding. The first pathway involves the general chaperones BINDING PROTEINS (BiPs), which belong to the classical heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) family, the DNA J protein ERdj3 and its associated STROMAL-DERIVED FACTOR 2 (SDF2) protein, and protein disulfide isomerases (PDI), which promote the formation of disulfide bonds (Strasser, 2018). The second pathway, a distinct ER folding pathway known as the calnexin–calreticulin cycle, is dedicated to N-glycosylated proteins. Calnexin and calreticulin are lectins that share a common architecture consisting of two major domains: a glycan binding domain and a long flexible P-domain involved in recruiting other co-chaperones such as PDIs. While calnexin is anchored to the ER via a transmembrane domain, its homologue calreticulin is soluble within the ER matrix and harbors a luminal KDEL ER retrieval signal (Strasser, 2018; Kozlov and Gehring, 2020). Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) contains two CALNEXIN (CNX) genes and three CALRETICULIN (CRT) genes (Persson et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2017).

In the CNX–CRT cycle, proteins entering the ER are first conjugated with a Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 glycan on specific asparagines (ASN) by the oligosaccharyltransferase (OST) complex. The N-linked glycans are then trimmed by two glucosidases (GCSI and GCSII) to generate a monoglucosylated GlcMan9GlcNAc2 glycan, which specifically interacts with CNX or CRT to promote protein folding and maturation. Removal of the terminal glucose by GCSII leads to the release of the glycoprotein from CNX/CRT. If the protein is inappropriately folded after release, the glucosyltransferase UDP-glucose:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase (UGGT) adds back a terminal glucose, enabling the re-association of the misfolded glycoprotein with CNX or CRT and thus initiating an additional round of folding (Liu and Howell, 2010; Strasser, 2018).

ER proteins that repeatedly fail to properly fold after several rounds of the CNX–CRT cycle are directed to become degraded. An important pathway for ER protein degradation involves the translocation of misfolded proteins to the cytosol for proteasomal degradation, a process termed ER-associated degradation (ERAD). Protein degradation through ERAD involves the recognition and transport of misfolded proteins across the ER membrane to the cytosol, followed by polyubiquitination and degradation via the 26S proteasome (Chen et al., 2020). The accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER leads to ER stress and the activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR). In turn, the activation of the UPR results in the upregulation of genes involved in vesicular trafficking, ERAD, and protein folding, including BiPs and PDIs (Liu and Howell, 2016). The UPR signaling pathway has two branches. In the first branch, the ER-anchored RNA splicing factor INOSITOL-REQUIRING 1 (IRE1) modifies the mRNA of the transcription factor BASIC LEUCINE-ZIPPER 60 (bZIP60), yielding a form of bZIP60 that lacks a transmembrane domain and is targeted to the nucleus. The second branch of the UPR signaling pathway activates two other members of the bZIP family, bZIP17 and bZIP28, via protease processing in the Golgi (Liu and Howell, 2016). Chronic ER stress that cannot be resolved by the activation of ERAD and the UPR can lead to programmed cell death as well as autophagy (Manghwar and Li, 2022).

ER stress has been associated with numerous abiotic stress factors that are thought to lead to defects in protein folding in the ER, such as heat, drought, osmotic, salt, and metal stress. The link between the control of ER protein folding and abiotic stress has been demonstrated via the analysis of mutants as well as transgenic plants overexpressing genes encoding ER chaperones, such as BiP, CNX, and PDIs, as well as genes involved in the ERAD and UPR pathways, including IRE1 and bZIP28 (Gao et al., 2008; Deng et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2013; Joshi et al., 2019; Park and Park, 2019; Reyes-Impellizzeri and Moreno, 2021). However, whether the control of protein folding in the ER has a role in plant responses to nutrient deficiencies has not been determined, although recent work has shown that autophagy may be implicated in such stress (Naumann et al., 2019; Stephani et al., 2020; Yoshitake et al., 2021).

Phosphorus is one of the most important nutrients affecting plant growth in both agricultural and natural ecosystems (Poirier et al., 2022). Plants acquire phosphorus almost exclusively via the transport of soluble inorganic phosphate (H2PO4−; Pi) into roots. Plants have evolved a series of metabolic and developmental responses to Pi deficiency that are aimed at maximizing Pi acquisition from the environment and optimizing its internal use for growth and reproduction (Dissanayaka et al., 2021; Poirier et al., 2022). One of the best-characterized responses of roots to phosphate deficiency is a decrease in primary root growth associated with reduced root meristem size (Crombez et al., 2019). This phenotype has been associated with the presence of Fe+3-malate complexes in the root meristem leading to changes in the cell wall structure and inhibition of cell-to-cell communication (Müller et al., 2015; Balzergue et al., 2017; Mora-Macias et al., 2017). Genetic screens for genes that contribute to changes in primary root growth under Pi deficiency identified LOW PHOSPHATE 1 (LPR1) and LPR2, encoding ferroxidases that convert Fe+2 to Fe+3, and PLEIOTROPIC DRUG RESISTANCE 2 (PDR2), encoding an ER-localized P5-type ATPase thought to negatively affect LPR activity via an unknown mechanism (Ticconi and Abel, 2004; Svistoonoff et al., 2007; Ticconi et al., 2009; Naumann et al., 2022). Additional proteins found to participate in this pathway include the malate and citrate efflux channel ALUMINUM-ACTIVATED MALATE TRANSPORTER 1 (ALMT1); the SENSITIVE TO PROTON RHIZOTOXICITY 1 (STOP1) transcription factor, which regulates ALMT1 expression; ALUMINUM SENSITIVE 3 (ALS3) and SENSITIVE TO AL RHIZOTOXICITY 1 (STAR1), which together form a tonoplast ABC transporter complex involved in plant tolerance to aluminum (although the nature of the molecule that is transported remains to be defined); and the CLAVATA/ESR-RELATED 14 (CLE14) peptide receptors CLAVATA 2 (CLV2) and PEP1 RECEPTOR 2 (PEPR2) (Balzergue et al., 2017; Dong et al., 2017; Gutierrez-Alanis et al., 2017; Mora-Macias et al., 2017).

In the present study, we analyzed Arabidopsis mutants affected in components of ER protein folding and quality control for their response to phosphate deficiency. We determined that CNX proteins participate in the Fe-dependent inhibition of primary root growth in response to phosphate deficiency.

Results

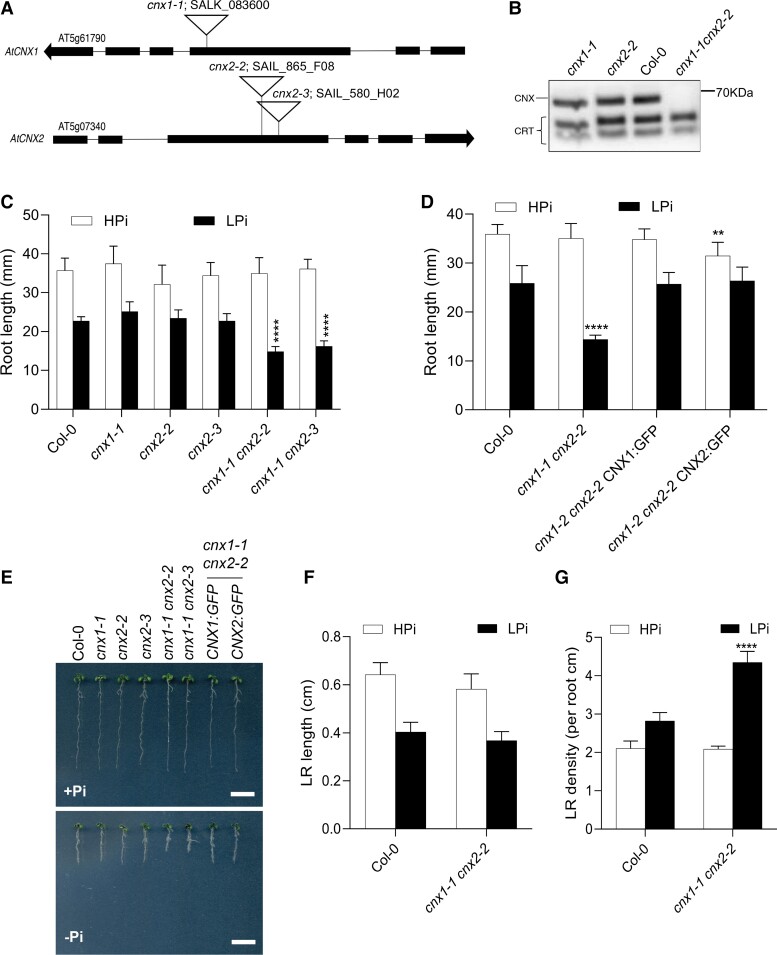

The cnx1 cnx2 double mutant shows reduced primary root growth under low Pi conditions

We crossed the Arabidopsis cnx1-1 mutant (SALK_083600), which has a T-DNA insertion in the third exon of CNX1 (At5g61790), with cnx2-2 (SAIL_865_F08) and cnx2-3 (SAIL_580_H02), which have T-DNA insertions in the third exon of CNX2 (At5g07340), to create two independent double mutant combinations (Figure 1A). Immunoblot analysis of protein extracts from whole seedlings showed that CNX proteins were absent in the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant, indicating that these mutant alleles are likely null (Figure 1B). We grew the plants in fertilized soil and in clay irrigated with nutrient solution containing 1 mM Pi (high Pi; HPi) or 75 µM Pi (low Pi; LPi) and found no significant differences between the single and double mutants compared with the wild type (WT; Col-0) in terms of fresh weight (Supplemental Figure 1, A and B) or Pi content in roots or rosettes (Supplemental Figure 1C). In agreement with these results, there was no significant difference in the amount of Pi acquired by the root system from liquid medium between the WT and the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant, either on LPi and HPi conditions (Supplemental Figure 1D). By contrast, in seedlings grown on agar-solidified medium, primary root length was significantly reduced in the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 and cnx1-1 cnx2-3 double mutants compared with the WT under LPi but not HPi conditions (Figure 1, C and E). This phenotype was complemented by transforming the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant with the CNX1-GFP or CNX2-GFP fusion construct driven by their respective endogenous promoters (Figure 1, D and E). Confocal microscopy of roots of the complemented lines expressing CNX1-GFP or CNX2-GFP revealed localization of these fusion proteins in the ER (Supplemental Figure 2A). Co-localization of CNX1-GFP and CNX2-GFP with an ER marker (ER-RFP) was observed in transiently transfected Nicotiana benthamiana leaf cells (Supplemental Figure 2B).

Figure 1.

Phenotype of the cnx1 cnx2 double mutant under high and low Pi conditions. A, Schematic diagram of the T-DNA insertions in the CNX1 (At5g61790) and CNX2 (At5g07340) genes in the cnx mutants. Exons are shown as black boxes. B, Immunoblot analysis of CNX and CRT in whole protein extracts from seedlings. The position of the 70 kDa molecular weight marker is shown on the right. C, Primary root length of WT compared with that of the cnx1-1 and cnx2-2 single and double mutants. Plants were grown for 7 days on plates containing 1 mM Pi (HPi) or 75 µM Pi (LPi) before measuring primary root length. D, Complementation of the primary root phenotype of cnx1-1 cnx2-2 plants transformed with the CNX1:GFP or CNX2:GFP construct. E, Representative photos of plants analyzed in C and D grown on HPi and LPi plates. Bars represent 1 cm. Length (F) and density (G) of lateral roots (LRs) of WT compared with those of the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant for plants on agar-solidified medium with HPi and LPi for 10 days. In C and D, statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey's test, and significant differences compared with WT in each growth condition are shown. In F and G, differences between WT and cn1-1 cnx2-2 were assessed by an unpaired t test. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001; error bars = SD; n ≥ 9.

No difference in lateral root length was observed between the WT and the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant for plants grown under LPi or HPi conditions (Figure 1F). However, an increase in lateral root density was observed in the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant relative to the WT, but only under LPi (Figure 1G). Such an increase in lateral root density is likely associated with the decrease in primary root length observed in the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 mutant under LPi.

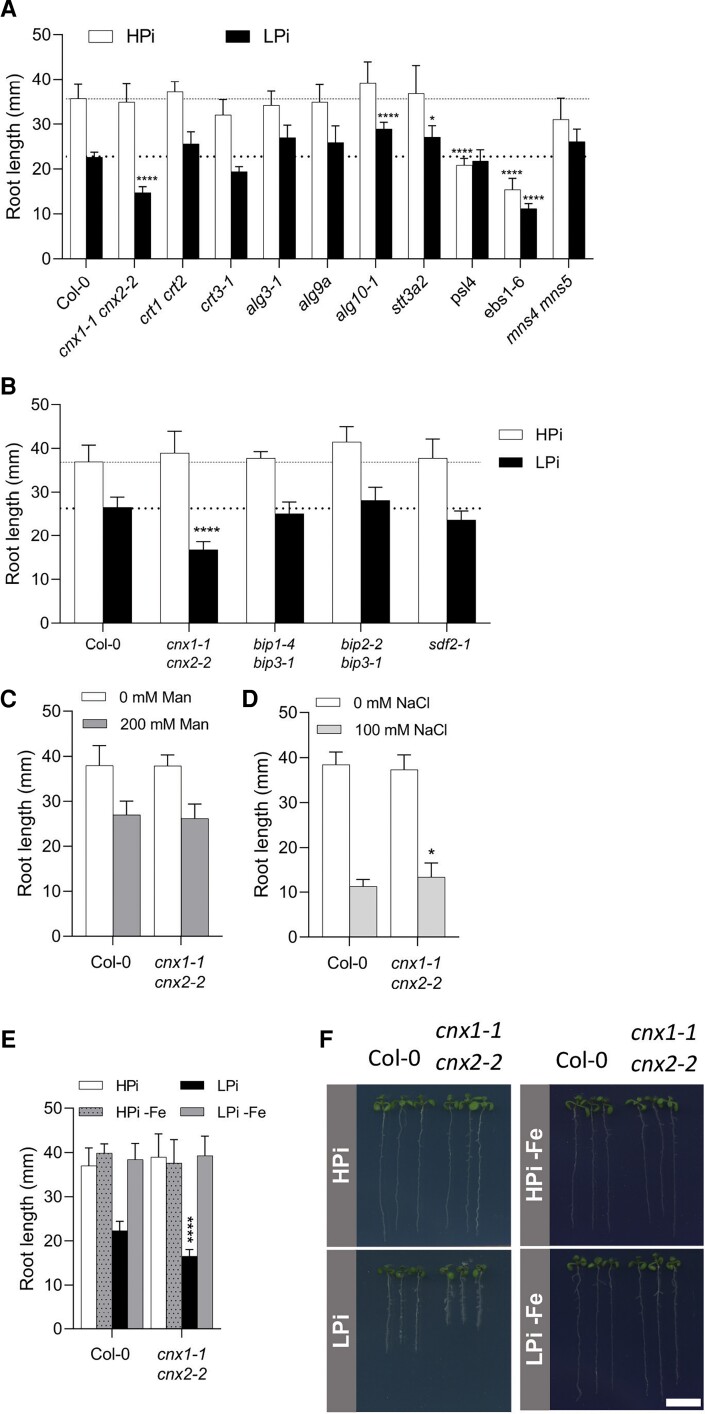

Mutants in other components of the CNX/CRT cycle and ER chaperone system do not reproduce the cnx1 cnx2 root growth phenotype under low Pi

In addition to CNX, ER protein quality control relies on numerous other proteins, including chaperones and enzymes involved in glycosylation and glycan modifications in the ER (Strasser, 2018). We therefore examined primary root growth of mutants in various components of the CNX/CRT cycle and ER protein quality control under LPi conditions. Arabidopsis CRTs are encoded by three genes, which are divided into two groups based on sequence similarity and function: CRT1/CRT2 and CRT3 (Persson et al., 2003; Christensen et al., 2010). No significant differences were detected in the root growth of crt1 crt2 or crt3 mutants under HPi or LPi conditions compared with WT (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Primary root growth of mutants in genes involved in ER protein synthesis and quality control. A and B, Plants were grown for 7 days on plates containing HPi or LPi before measuring primary root length. C and D, Primary root length of WT and cnx1-1 cnx2-2 plants after 7 days of growth on HPi plates (C) without or with 200 mM mannose or (D) without or with 100 mM NaCl. E and F, Primary root length of WT and cnx1-1 cnx2-2 after 7 days of growth on plates containing HPi or LPi half-strength MS medium or the same medium with ferrozine to chelate Fe (HPi-Fe and LPi-Fe). Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey's test, and significant differences compared with WT in each growth condition are shown, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, error bars = SD, n ≥ 5. Bar represents 1 cm in F.

The synthesis of the lipid-linked oligosaccharide unit Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 involves a series of ER glycosyltransferases including the mannosyltransferases ASPARAGINE-LINKED GLYCOSYLATION 3 (ALG3) and ALG9 and the glucosyltransferase ALG10 (Kajiura et al., 2010; Farid et al., 2011; Hong et al., 2012). Following its synthesis, the Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 unit is added to ER proteins co-translationally by the membrane-associated heteromeric OST complex, which includes the catalytic STAUROSPORIN AND TEMPERATURE SENSITIVE 3 (STT3) subunit found as two isoforms in Arabidopsis, namely STT3a and STT3b (Koiwa et al., 2003). Primary root growth under HPi and LPi conditions was not reduced in the alg3-1, alg9a, alg10-1, or stt3a2 mutants compared with WT (Figure 2A).

The presence of terminal α1,2-linked glucose residues, which facilitate the interaction between CNX/CRT and N-glycosylated proteins, is regulated by the trimming action of GCSII and the glucosylating activity of the UDP-glucose:glycoprotein glucosyltransferase (UGGT). PRIORITY IN SWEET LIFE 5 (PSL5) and PSL4 encode the alpha and beta subunits of GCSII, respectively, while the UGGT is encoded by a single EBS1/UGGT gene (Lu et al., 2009). The primary roots of the psl4 mutant were shorter than those of WT when grown on HPi medium, and there was no significant further reduction in their length when grown on LPi medium (Figure 2A). In contrast, primary root growth was severely compromised in the ebs1-6/uggt1-1 mutant on both HPi and low LPi media (Figure 2A).

ER proteins that pass through the CNX/CRT cycle but remain inappropriately folded are degraded by ERAD. This process involves the trimming of mannosyl groups on the N-glycan chain by several α-mannosidases, which include MANNOSIDASE 4 (MNS4) and MNS5 (Huttner et al., 2014). Primary root growth of the mns4 mns5 double mutant was not significantly different from that of WT on HPi or LPi medium (Figure 2A).

We also examined the role of the ER chaperone pathway involving BiP and SDF2 in the response of Arabidopsis roots to Pi deficiency. While SDF2 is encoded by a single gene in Arabidopsis (Nekrasov et al., 2009), three genes encode the ER BiP chaperones. BIP1 and BIP2 encode proteins that are 99% identical and are ubiquitously expressed, while the more divergent BiP3 is expressed under ER stress (Maruyama et al., 2014). Root growth of the bip1-4 bip3-1, bip2-2 bip3-1, and sdf2-1 mutants was similar to that of WT on both HPi and LPi media (Figure 2B).

Several mutants related to the CNX/CRT cycle and ER protein homeostasis, including alg10, stt3a, mns4 mns5, and ebs1-6/uggt1, exhibit strong root growth phenotypes under salt stress (Koiwa et al., 2003; Farid et al., 2011; Huttner et al., 2014; Blanco-Herrera et al., 2015). To investigate whether the reduced primary root length observed in cnx1-1 cnx2-2 was specific to Pi deficiency stress, we examined root growth in this double mutant under two other abiotic stress conditions that reduced primary root growth: osmotic stress (200 mM mannitol) and salt stress (100 mM NaCl). Under both stress conditions, primary root growth was similar in the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant and WT (Figure 2, C and D), indicating that the root growth phenotype of this double mutant is specific to Pi deficiency stress.

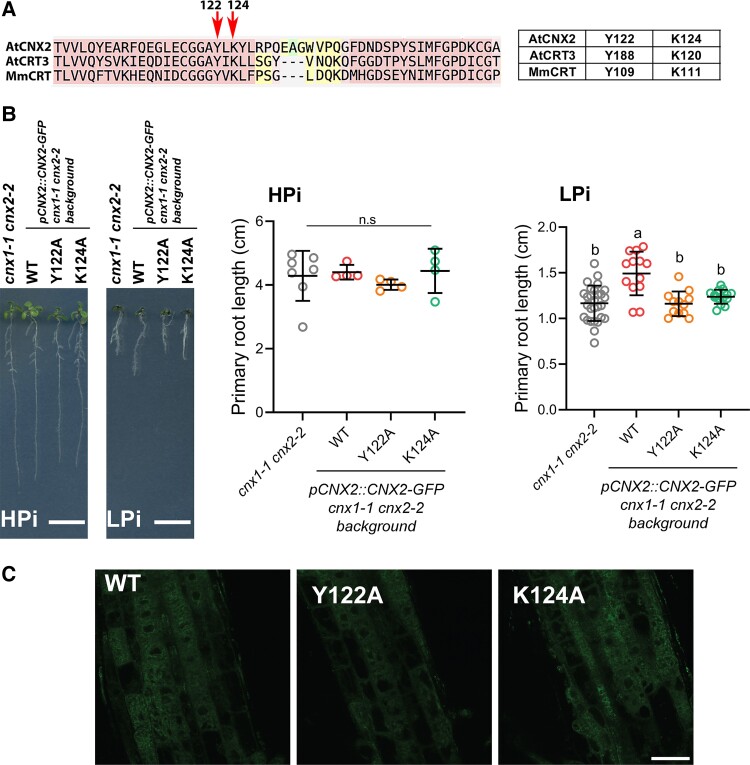

Complementation of the cnx1 cnx2 root phenotype by CNX2 is dependent on amino acids involved in binding the GlcMan9GlcNAc2 glycan

Crystallographic analysis of mouse CRT combined with modeling as well as in vitro biochemical studies have identified a number of amino acids residues directly involved in binding the GlcMan9GlcNAc2 glycan (Kapoor et al., 2004; Thomson and Williams, 2005; Kozlov et al., 2010). Among them are Y109 and K111 which form hydrogen bonds with two distinct oxygens of the terminal glucose residue of GlcMan9GlcNAc2 (Kozlov et al., 2010). Mutation of the corresponding Y118 and K120 residues of the Arabidopsis CRT3 demonstrated the critical role, in vivo, of these amino acids in enabling the interaction of CRT3 with a structurally modified but active version of the BRI1 brassinosteroid receptor found in the bri1-9 mutant (Liu and Li, 2013). Alignment of CNX2 with the Arabidopsis CRT3 and the mouse CRT enabled the identification of the corresponding Y122 and K124 residues in CNX2 (Figure 3A; Supplemental Figure 3). These two residues were independently mutated to alanine in a pCNX2::CNX2-GFP fusion construct and transformed into the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant. While transformation with the WT pCNX2::CNX2-GFP enabled the complementation of the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 short-root phenotype under LPi condition, neither the Y122A or K124A mutants could complement the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 mutant root phenotype, although the mutant and WT constructs were all expressed in the ER of root tips (Figure 3, B and C). These results reveal that the GlcMan9GlcNAc2 binding domain of CNX2 is critical for its role in maintaining primary root growth under LPi condition.

Figure 3.

Mutations in the glycan binding domain of CNX2 abolish its ability to complement the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 mutant phenotype. A, Alignment of segments of CNX2 and CRT3 from Arabidopsis (AtCNX2, AtCRT3) and CRT from mouse (MmCRT). The key amino acids Y122 and K124 from the AtCNX2 targeted by mutagenesis are highlighted by red arrows. The table on the right shows the equivalence in the position of the key tyrosine and lysine residues in AtCNX2, AtCRT3, and MmCRT. B, Primary root length of cnx1-1 cnx2-2 parental plants and transgenic cnx1-1 cnx2-2 transformed with the wild type (WT), Y122A, or K124A mutant versions of the construct pCNX2::CNX2-GFP. Plants were grown for 7 days on plates containing 1 mM Pi (HPi) or 75 µM Pi (LPi) before measuring primary root length. Error bars = SD. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey's test; different letters indicate a significant difference with a P-value < 0.05. Bars in the left photo represent 1 cm. C, Confocal images of GFP expression of WT, Y122A, or K124A mutant versions of the construct pCNX2::CNX2-GFP in roots tips of transgenic cnx1-1 cnx2-2 plants. Bars = 25 µm, applies to all images.

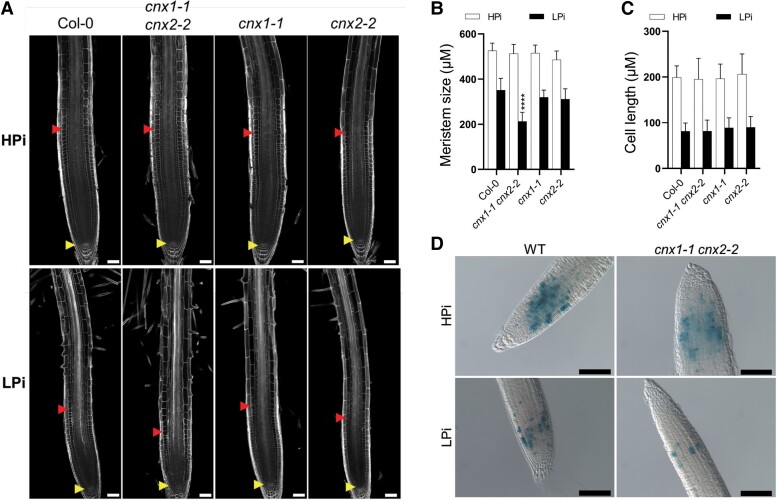

The root phenotype of cnx1 cnx2 is due to reduced root apical meristem activity

Reduced primary root growth under stress conditions can be caused by reduced cell division within the meristem, reduced cell elongation, or both. Under LPi but not HPi conditions, the meristematic zone was smaller in cnx1-1 cnx2-2 compared with WT and the corresponding single mutants (Figure 4, A and B). By contrast, the cell length in the elongation zone was not significantly different between the mutants and WT under HPi or LPi conditions (Figure 4, A and C). These data indicate that cnx1-1 cnx2-2 is mainly affected in meristematic cell division under LPi conditions. To further evaluate the contribution of cell division to the mutant phenotype, we introduced into the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant a reporter construct for cell division consisting of a labile GUS under the control of the cyclin B1 promoter (Colon-Carmona et al., 1999). The number of dividing, GUS-expressing cells, was similar in cnx1-1 cnx2-2 and WT roots under HPi conditions (Figure 4D). By contrast, a clear reduction in GUS-expressing cells was observed in WT roots grown under LPi, in accordance with the known reduction in meristematic cell division under these conditions (Ticconi et al., 2004). Importantly, a further reduction in GUS-expressing cells in root meristems was observed in the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant compared with WT on LPi (Figure 4D). Altogether, these data indicate that the altered primary root growth of cnx1-1 cnx2-2 is primarily due to reduced meristematic cell division under LPi conditions.

Figure 4.

The cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant is affected in meristem activity. A–C, Plants were grown for 7 days on plates containing 1 mM Pi (HPi) or 75 µM Pi (LPi) before measuring the length of the cell division zone in the meristem (A, B), defined in A by the yellow and red arrows, and cell length in the differentiation zone (C). Statistical analysis (B, C) was performed by two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey's test; significant differences compared with WT under each growth condition are shown: ****P < 0.0001; error bars = SD; n ≥ 5 in (B) and 20 in (C). D, WT and cnx1-1 cnx2-2 plants transformed with the cylinB1:GUS reporter gene construct were grown for 7 days on plates containing HPi or LPi medium and stained for β-glucuronidase activity. Bars represent 50 um in A and 100 µm in D.

The root phenotype of cnx1-1 cnx2-2 is dependent on Fe and associated with increased Fe deposition in the meristem

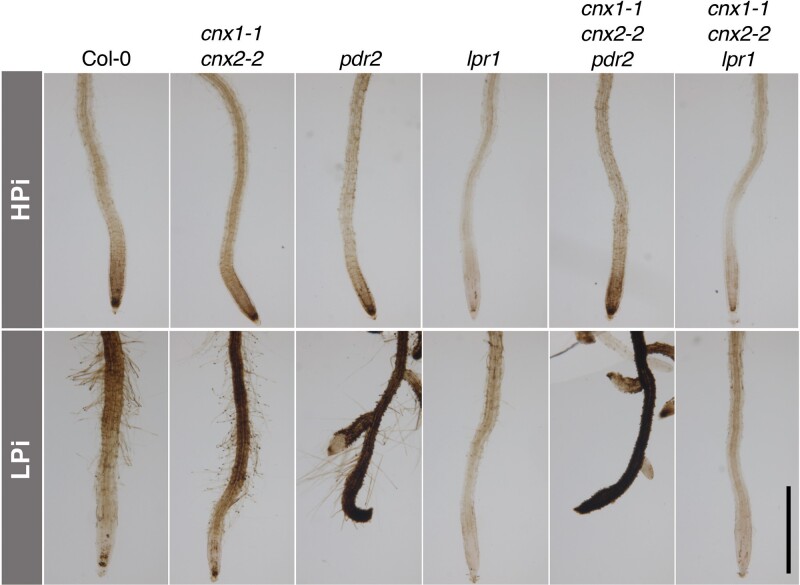

Several studies have shown that the reduced primary root growth of plants under low Pi in WT and in various mutants with more severe root growth inhibition is dependent on the presence of Fe in the growth medium (Ticconi et al., 2009; Müller et al., 2015; Balzergue et al., 2017; Dong et al., 2017). Indeed, a comparison of root growth on HPi and LPi medium with and without Fe showed that the reduced primary root growth observed in cnx1-1 cnx2-2 under LPi conditions was also dependent on the presence of Fe in the medium (Figure 2, E and F). We used Perls-DAB staining to examine the distribution of apoplastic Fe in plants grown under HPi and LPi conditions. The lpr1 mutant (which is insensitive to low Pi-induced root growth inhibition) and pdr2 mutant (which has very strongly reduced primary root growth under low Pi conditions) were used as controls (Müller et al., 2015). In plants grown under HPi conditions, no substantial differences were observed in Fe distribution in the root meristematic and elongation zones between WT and cnx1-1 cnx2-2 or pdr2, whereas lpr1 showed substantially reduced Fe deposition (Figure 5, upper panels). Under LPi conditions, the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant showed robust enhancement of Fe deposition in the root differentiation zone and more modest enhancement in the root elongation and meristematic zones compared with WT, whereas pdr2 roots showed extensive Fe deposition throughout the root, and lpr1 showed minimal Fe deposition (Figure 5, lower panels).

Figure 5.

Fe accumulation and distribution in the roots of mutants grown under high and low Pi conditions. Plants were grown for 7 days on plates containing 1 mM Pi (HPi) or 75 µM Pi (LPi) and subjected to Perls-DAB staining for Fe visualization. Bar represents 1 mm.

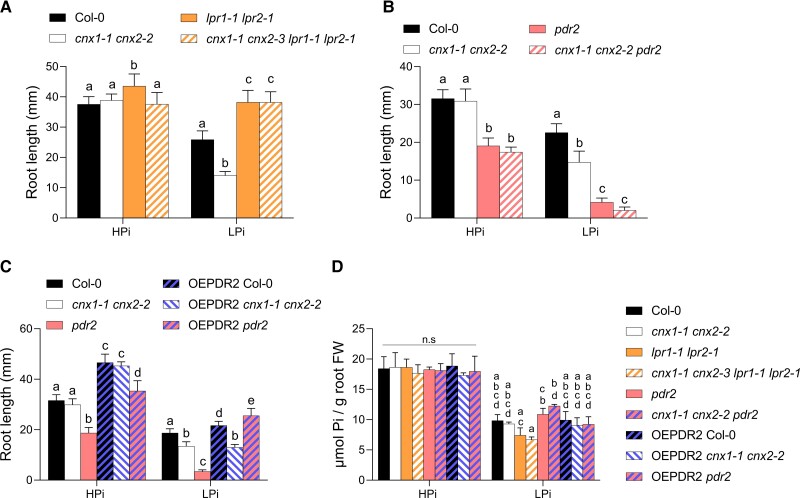

pdr2 and lpr1 lpr2 are epistatic to cnx1-1 cnx2-2

We examined the epistasis among cnx1-1 cnx2-2, lpr1 lpr2, and pdr2 by generating triple and quadruple mutants. Primary root growth of cnx1-1 cnx2-2 lpr1 lpr2 was insensitive to low Pi, as the primary root length of this quadruple mutant was identical to that of lpr1 lpr2 and longer than that of WT under LPi conditions (Figure 6A). The pdr2 mutant showed reduced primary root growth in HPi; this phenotype remained unchanged in the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 pdr2 triple mutant. On LPi medium, the pdr2 mutant showed more strongly reduced primary root growth than cnx1-1 cnx2-2, and this phenotype was maintained in the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 pdr2 triple mutant (Figure 6B). The epistatic action of lpr1 and pdr2 over cnx1-1 cnx2-2 was also observed at the level of Fe accumulation for roots grown under HPi and LPi (Figure 5).

Figure 6.

Epistatic interactions among cnx1-1 cnx2-2, lpr1-1 lpr2-1, and pdr2. Plants were grown for 7 days on 1 mM Pi (HPi) or 75 µM Pi (LPi) plates before recording primary root length. A, Epistatic interaction between cnx1-1 cnx2-2 and lpr1-1 lpr2-1. B, Epistatic interaction between cnx1-1 cnx2-2 and pdr2. C, A T-DNA cassette for PDR2 overexpression under the control of the CaMV35S promoter (OEPDR2) was introgressed into Col-0, cnx1-1 cnx2-2, and pdr2. D, Pi content in roots for plants grown for 7 days on HPi or LPi. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey's test, and significant differences within each growth condition are shown. Different lowercase letters (a, b, c, or d) indicate a significant difference with a P-value < 0.05, n ≥ 6, error bars = SD.

We also examined the effect of overexpressing PDR2 driven by the CaMV35S promoter. WT and pdr2 plants overexpressing PDR2 had significantly longer primary roots compared with those of untransformed WT plants on both HPi and LPi media. By contrast, while cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant plants overexpressing PDR2 also had longer primary roots compared with those of WT plants grown under HPi conditions, the same plants showed shorter primary roots than those of WT plants and comparable root lengths to those of the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant when grown under LPi conditions (Figure 6C). Overall, these data indicate that the primary root phenotypes of pdr2 and lpr1 lpr2 are epistatic to cnx1-1 cnx2-2 under LPi and that overexpressing PDR2 failed to rescue the short-root phenotype of cnx1-1 cnx2-2 under LPi.

Quantification of the Pi content in roots of the various mutants used in the epistasis analysis showed no significant differences for plants grown under HPi condition. On LPi, there was a trend toward lower Pi content in the lpr1 lpr2 and cnx1-1 cnx2-2 lpr1 lpr2 mutants compared with WT, although these differences were not statistically significant (Figure 6D).

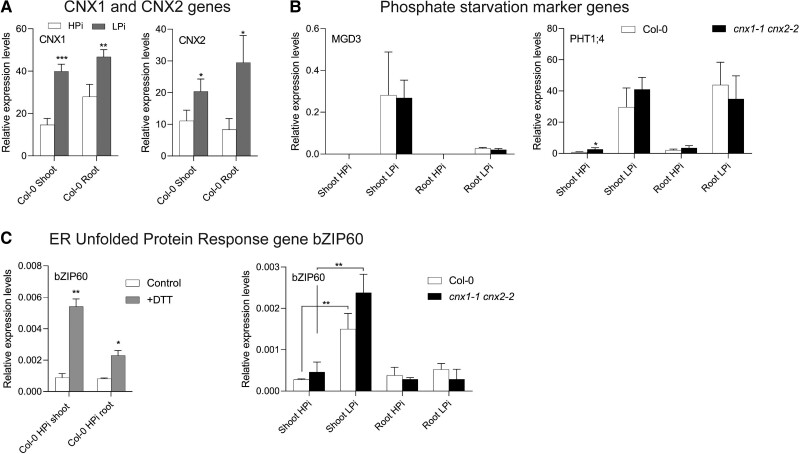

Pi deficiency induces CNX gene expression and ER stress

We examined the expression of CNX1 and CNX2 in the shoots and roots of plants grown on LPi and HPi media via reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). The expression of both CNX1 and CNX2 significantly increased under Pi-deficient conditions (Figure 7A). However, the increase in expression for these genes was moderate compared with that of other Pi deficiency–responsive genes, such as MONOGALACTOSYL DIACYLGLYCEROL SYNTHASE 3 (MGD3) and PHOSPHATE TRANSPORTER 1;4 (PHT1;4) (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Impact of the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 mutations on the expression of Pi deficiency and unfolded protein response marker genes. A, CNX1 and CNX2 expression in the shoots and roots of plants grown for 7 days in 1 mM Pi (HPi) or 75 µM Pi (LPi) medium. B, Expression of the Pi deficiency markers MGD3 and PHT1;4 in the shoots and roots of WT and cnx1-1 cnx2-2 grown for 7 days on HPi or LPi medium. C, Induction of ER unfolded protein response marker gene bZIP60 in the shoots and roots of WT at 24 h after the addition of 2 mM DTT and in the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant compared with WT grown under HPi or LPi conditions. Statistical analysis was performed by Student's t test comparing different treatments (HPi and LPi for A and C, Control and DTT for C) and WT versus cnx1-1 cnx2-2 (B, C), with significant differences indicated by asterisks: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Error bars = SD, n = 3.

We investigated the transcriptional response of the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant to Pi deficiency conditions by examining MGD3 and PHT1;4 expression. The expression of both genes in shoots and roots did not significantly differ between cnx1-1 cnx2-2 and WT on HPi or LPi medium, except that PHT1;4 was slightly upregulated in cnx1-1 cnx2-2 shoots on HPi medium (Figure 7B).

The accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER leads to ER stress and the increased expression of the transcription factor gene bZIP60 (Lu and Christopher, 2008). To determine whether LPi treatment leads to ER stress and whether the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant exhibits greater signs of ER stress compared with WT plants, we compared the expression of bZIP60 in cnx1-1 cnx2-2 versus WT plants grown on HPi and LPi. When we treated plants with the reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT) to induce ER stress, bZIP60 was upregulated, with a greater increase in shoots compared with in roots (Figure 7C; Lu and Christopher, 2008). Under LPi conditions, bZIP60 expression significantly increased in shoots but not in roots in both WT and cnx1-1 cnx2-2, with no significant difference in bZIP60 expression between these lines (Figure 7C). Thus, the removal of calnexin did not lead to an increase in ER stress compared with the stress level in WT under either HPi or LPi conditions.

Discussion

In the present study, while the cnx1-1 and cnx2-2 single mutants showed no defect in primary root growth under HPi or LPi conditions, the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant showed reduced primary root growth under LPi but not HPi conditions; this phenotype was complemented by the expression of either CNX1 or CNX2 driven by their native promoters. Thus, CNX1 and CNX2 are both required and play functionally redundant roles in the response of primary roots to Pi deficiency.

The cnx1 cnx2 double mutant showed no reduction in secondary root growth as well as no reduction in the capacity of the root system to acquire Pi under LPi or HPi conditions. These features likely explain why the cnx1 cnx2 mutant shows no reduction in growth or shoot Pi content when grown in soil or clay substrate irrigated with HPi or LPi solution. Under these experimental conditions, differences in primary root length under LPi condition would have an overall minimal impact on the global root mass and capacity of the root system to acquire Pi from the media or soil solution. Similar results have previously been shown for the pdr2 mutant, which has a stronger primary root growth reduction phenotype on LPi than cnx1 cnx2 (Ticconi et al., 2004).

Both CNX1 and CNX2 are localized to the ER in Arabidopsis, and the corresponding genes are broadly expressed in most tissues (except that only CNX1 is substantially expressed in pollen) and throughout development in both shoots and roots (Liu et al., 2017). Previous analysis of higher-order Arabidopsis mutants of CNX and CRT revealed that while the cnx1 cnx2 double mutant had no phenotype under normal growth conditions, the crt1 crt2 double mutant and the crt1 crt2 crt3 triple mutant showed reduced rosette growth in soil and reduced hypocotyl elongation in the dark (Christensen et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2013; Vu et al., 2017). These results indicate that the CNX and CRT are involved in the folding of at least partially distinct set of client proteins in the ER. CRT3 is a divergent calreticulin within the CRT family and has been shown to contribute to the stability and turnover of several transmembrane receptor-like kinases, such as the brassinosteroid receptor BRI1 as well as the EFR and SOBIR1 receptors involved in plant immunity to bacterial pathogens (Jin et al., 2009; Li et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2014). The absence of primary root phenotype of the crt1 crt2 and crt3-1 mutants on LPi indicate that the calreticulins are unlikely to affect folding of the client protein(s) involved in the primary root growth phenotype of the cnx1 cnx2 mutant.

Analysis of several mutants in genes implicated in the synthesis of the lipid-linked Glc3Man9GlcNAc2 glycan (alg3-1, alg9a, and alg10-1) and its transfer to Asn residues of ER proteins (stt3a), the processing/transfer of the terminal glucose moieties (psl4 and ebs1-6), the ERAD pathway (mns4 mns5), or various ER molecular chaperones (sdf2-1, bip mutants) failed to unambiguously reveal defects in primary root growth specifically under LPi conditions. These mutants affect different steps in pathways with distinct consequences on protein folding, protein quality control, or protein degradation (Strasser, 2018). PSL4 and EBS1/UGGT are two proteins that are directly involved in the CNX/CRT cycle. The presence of primary root growth phenotypes on HPi for the psl4 and ebs1-6 mutants may be masking more subtle effects of the LPi condition. Indeed, ebs1 mutants have been shown to have strong growth defects affecting both shoots and roots (Blanco-Herrera et al., 2015). Furthermore, mutation in the catalytic alpha subunit of the glucosidase II complex, encoded by the PSL5 gene, has a strong shoot and root growth phenotype resulting from defects in cellulose biosynthesis (Burn et al., 2002). The role of the non-catalytic ß subunit of glucosidase II, encoded by PSL4, in the trimming of glucose residues is currently poorly defined and it is plausible that the carbohydrate binding domain of PSL4 modulates glucosidase II activity only on a subset of CNX/CRT client proteins. It is interesting to note that even highly related glycoproteins may have very distinct requirement for the participation of proteins involved in ER protein folding and quality control. For example, while the leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase (LRR-RK) EFR1 requires the participation of PSL4, PSL5, CRT3, and EBS1/UGGT for optimal activity, the same set of proteins appear not necessary for the activity of the related LRR-RK flagellin receptor FLS2 (Li et al., 2009; Lu et al., 2009). Even structural variants of BRI1 show distinct interactions with the components of the CRT–CNX cycle. Although the BRI1-5 variant interacts with CNX1/CNX2, the cnx1 cnx2 bri1-5 triple mutant was indistinguishable from the bri1-5 single mutant, while ebs1 bri1-5 double mutants had enhanced growth inhibition (Hong et al., 2008). In contrast, the BRI1-9 variant interacts with CRT3 and introgression of either crt3 or ebs1 into bri1-9 suppresses the growth phenotype associated with bri1-9 (Jin et al., 2007, 2009). Understanding the contribution of various components of the ER protein folding and quality control on the short-root phenotype of the cnx1 cnx2 mutant will likely require the identification of the CNX1/CNX2-specific client protein(s) affected in the cnx1 cnx2 mutant that are responsible for this phenotype.

Several mutants we have tested for primary root growth under LPi conditions, including alg10-1, stt3a2, ebs1-6, and mns4 mns5, were previously shown to have altered root growth under salt stress (Koiwa et al., 2003; Farid et al., 2011; Huttner et al., 2014; Blanco-Herrera et al., 2015). Considering that the growth of cnx1-1 cnx2-2 roots was comparable to that of WT roots under salt stress and osmotic stress, it is likely that defects in different components of the CNX–CRT cycle affect distinct N-glycosylated proteins to different extents. That is, the proteins affected in the alg10-1, stt3a2, ebs1-6, and mns4 mns5 mutants are involved in the salt stress response, while those affected in cnx1-1 cnx2-2 are involved in the Pi deficiency response.

While the mode of action of CNX and CRT in ER protein folding has essentially been defined through the binding of the GlcMan9GlcNAc2 moiety present on N-glycosylated proteins (Strasser, 2018), recent work has demonstrated that CNX can preferentially interact with misfolded non-glycosylated membrane proteins via its single transmembrane domain (Bloemeke et al., 2022). The fact that CNX2 with mutations in key amino acids involved in interacting with the terminal glucose residue of GlcMan9GlcNAc2 failed to complement the short primary root phenotype of the cnx1 cnx2 mutant shows that the glycan binding activity of CNX2 to target N-glycosylated client protein(s) is an essential element in the response of primary root growth to LPi. While CRT and CNX bind to both soluble and membrane-bound glycoproteins (Helenius and Aebi, 2004), the recently proposed dual binding mode involving interaction of transmembrane domains and N-glycan-dependent binding may distinguish CNX1/CNX2 client proteins from CRT clients (Bloemeke et al., 2022).

The cnx1 cnx2 mutant shares several features with the pdr2, als3, and star1 mutants in terms of their responses to LPi conditions, including Fe-dependent reduced primary root growth associated with a reduction in root meristem size (Ticconi et al., 2004; Müller et al., 2015; Dong et al., 2017). However, the pdr2, als3, and star1 mutants have additional root phenotypes under LPi conditions that are not observed in cnx1-1 cnx2-2, such as reduced cell length in the root elongation zone and a distorted cellular organization of the root meristem. Furthermore, the pdr2 mutant was previously shown to have a strongly reduced number of lateral roots and an induction of PSI gene expression, such as PHT1;4 (Ticconi et al., 2004), features that are not observed in the phenotypically milder cnx1 cnx2 mutant. The apoplastic Fe accumulation (as visualized by Perls-DAB staining) is stronger in pdr2, als3, and star1 roots than in cnx1-1 cnx2-2 roots when grown in LPi in both the elongation and meristematic zones (Ticconi et al., 2004; Müller et al., 2015; Dong et al., 2017). Initial characterization of mutants such as pdr2, lpr1, almt1, and als3 linked strong apoplastic Fe staining in the root meristematic and elongation zones with inhibited cell division and cell elongation. Fe accumulation in the meristem is associated with ROS production, which affects cell wall structure and meristem cell division via reduced mobility of SHORT-ROOT (SHR) in the stem cell niche (Müller et al., 2015; Balzergue et al., 2017). However, a more detailed analysis of dynamic changes in Fe accumulation and primary root growth over time revealed that the extent of primary root growth inhibition cannot simply be directly linked to the level of apoplastic Fe accumulation in the root meristem and elongation zone (Wang et al., 2019). Numerous interactions have been described in the pathways involving Fe and Pi homeostasis, with complex interplay occurring at levels ranging from transport to signaling pathways, which could also impact primary root growth (Hanikenne et al., 2021; Nussaume and Desnos, 2022).

PDR2 encodes a member of the eukaryotic type V subfamily (P5) of P-type ATPase (Ticconi et al., 2009). PDR2 is abundant in the ER, but its mode of action and transport activity are largely unknown, although recent work has reported a role of the yeast P5A ATPase Spf1 in protein translocation in the ER (McKenna et al., 2020). PDR2 is thought to modulate the activity and/or abundance of the ferroxidase LPR1 in the apoplast, which is responsible for the oxidation of Fe+2 to Fe+3 (Müller et al., 2015; Naumann et al., 2022). Consequently, the lpr1 phenotypes (in terms of both Fe deposition and reduced primary root growth under LPi conditions) are epistatic to pdr2 (Ticconi et al., 2009). The lpr1 phenotypes are also epistatic to cnx1-1 cnx2-2. It is unknown if PDR2 is N-glycosylated and if it enters the CNX–CTR cycle. However, considering the milder phenotypes of cnx1-1 cnx2-2 compared with that of pdr2 and the finding that overexpressing PDR2 did not influence the reduced primary root growth of cnx1 cnx2 on LPi medium, it is unlikely that the root growth phenotype of cnx1-1 cnx2-2 is mediated by reduced PDR2 activity.

The lack of calnexin leads to a range of phenotypes in fungi and animals, from lethality in the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe to developmental and neurological abnormalities in zebrafish, mouse, and Drosophila (Parlati et al., 1995; Kraus et al., 2010; Hung et al., 2013; Xiao et al., 2017). The current study highlights a role for calnexin in the response of primary root growth to Pi deficiency. Phosphate deficiency has been associated with an increase in autophagy in root tips and leaves as well as an increase in CNX1 and BiP2 expression (Naumann et al., 2019; Yoshitake et al., 2021). Here, Pi deficiency resulted in the increased expression of CNX1 and CNX2 in both roots and shoots as well as bZIP60 in shoots. Collectively, these data reveal that Pi deficiency is associated with an increase in ER stress. Yet, the absence of a substantial difference in bZIP60 expression between WT and the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant indicates that the absence of calnexin in Arabidopsis does not lead to a systematic increase in ER stress responses, at least under HPi or LPi conditions. This implies that the folding and activity of a restricted number of N-glycosylated proteins are likely affected by the absence of calnexin; one or a few of these proteins likely contribute to the reduced primary root growth under LPi conditions.

Materials and methods

Plant lines and growth conditions

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) seeds were surface sterilized and grown for 7 days on plates containing half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium without phosphate (Caisson Laboratories) supplemented with 75 μM or 1 mM KH2PO4 buffer (pH 5.8), 1% (w/v) sucrose, 0.7% (w/v) agarose, and 500 mg/L 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (final pH 5.8). To induce different levels of phosphate and iron deficiency, ferrozine was added to the medium at a final concentration of 100 μM. Plants were grown vertically on plates at 22°C under a continuous light intensity of 100 μmol/m2/s.

Plants were also grown in soil or in a clay-based substrate (Seramis) irrigated with phosphate-free half-strength MS supplemented with KH2PO4 buffer, pH 5.8. The growth chamber conditions were 22°C and 60% relative humidity with a 16-h-light/8-h-dark photoperiod with 100 μE/m2/s of white light.

All Arabidopsis lines used in this study are in the Col-0 background. A single cnx1 (SALK_083600C) allele and two cnx2 (SAIL_865_F08 and SAIL_580_H02) mutant alleles were identified from T-DNA insertional lines obtained from the European Arabidopsis Stock Center (NASC) (http://arabidopsis.info). Supplemental Table 1 lists the sources of all other lines used in this study. Plants overexpressing PDR2 under the control of the CaMV35S promoter (Ticconi et al., 2009) as well as plants expressing the reporter construct cycB1::GUS (Colon-Carmona et al., 1999) were described previously.

Phosphate quantification

Quantification of Pi was performed as previously described (Ames, 1966). Shoot or root material was placed in pure water, and at least three freeze–thaw cycles were applied to release the inorganic Pi, which was quantified via a molybdate assay using a standard curve. For Pi quantification of seedlings, four biological replicates per condition were utilized, where tissues from 20 seedlings were pooled together. The statistical differences were assessed by two-way ANOVAs followed by Tukey's tests. For Pi quantification on plants grown in soil, tissue from individual plants was collected as biological replicates (8–10 replicates per condition were used). The statistical differences were analyzed by Student's t tests.

DNA constructs and gene expression analysis

PCR-generated fragments of the CNX1 and CNX2 genomic regions lacking stop codons and including the 1-kbp promoter regions were obtained using Phusion HF DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs), inserted into pENTR-2B, and recombined in pMDC107 to generate the GFP-tagged construct using Gateway technology. Generation of the Y122A and K124A point mutants in the construct pCNX2::CNX-GFP was performed by gene synthesis (GenScript Biotech, Netherlands). The various binary vectors were introduced into Arabidopsis plants via Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation using the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998).

Total RNA was extracted from roots or shoots using an RNA Purification kit as described by the manufacturer (Promega), followed by DNase I treatment. cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of RNA using M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega) and oligo d(T)15 following the manufacturer's instructions. RT-qPCR analysis was performed using SYBR Select Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) with primer pairs specific to genes of interest; ACT2 was used for data normalization. The primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 2. Three biological replicates per condition were used, each one consisting of a pool of approximately 60 seedlings. Significant differences in gene expression levels were analyzed using Student's t tests.

Root measurements, microscopy, and staining procedures

Root length was measured using seedlings grown on vertically oriented plates. The plates were scanned on a flatbed scanner to produce image files suitable for quantitative analysis using ImageJ software (v1.44p).

Confocal microscopy was performed using a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal laser scanning microscope. Plant roots were treated with Clearsee solution and stained with calcofluor white (Ursache et al., 2018) to visualize cell walls. A line expressing the cycB1::GUS reporter was used to introgress the construct into the cnx1-1 cnx2-2 double mutant background. Roots were stained for GUS activity as previously described (Lagarde et al., 1996). The tissues were vacuum infiltrated to enhance tissue penetration. Stained tissues were cleared in chloral hydrate solution (2.7 g/mL in 30% (v/v) glycerol) and analyzed using a Leica DM5000B bright-field microscope.

Iron accumulation in seedlings was assayed by Perls-DAB staining as previously described (Müller et al., 2015). Briefly, seedlings were incubated in 4 mL of 2% (v/v) HCl and 2% (w/v) potassium ferrocyanide for 30 min. The samples were washed with water and incubated for 45 min in 4 mL of 10 mM NaN3% and 0.3% H2O2 (v/v) in methanol. The samples were then washed with 100 mM Na-phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and incubated for 30 min in the same buffer containing 0.025% (w/v) DAB and 0.005% (v/v) H2O2. Finally, the samples were washed twice with water, cleared with chloral hydrate (1 g/mL, 15% glycerol (v/v), and analyzed using an optical microscope.

Immunoblot analysis

Proteins were extracted from homogenized plant material at 4°C in extraction buffer containing 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 300 mM sucrose, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 20 mM NaF, and 1× protease inhibitor (Roche EDTA Free Complete Mini Tablet) and sonicated for 10 min in an ice-cold water bath. Fifty micrograms of proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to an Amersham Hybond-P PVDF membrane (GE Healthcare). The membrane was probed with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against maize calreticulin, which cross-reacts with both Arabidopsis calnexin and calreticulin (Persson et al., 2003), and goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) using the Western Bright Sirius HRP substrate (Advansta). Signal intensity was measured using a GE Healthcare ImageQuant RT ECL Imager.

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in The Arabidopsis Information Resource (www.arabidopsis.org) using the gene codes as defined in Supplemental Table 1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Shuh-ichi Nishikawa (Niigata University, Japan), Cyril Zipfel (University of Zurich, Switzerland), and Thierry Desnos (CEA-Cadarache, France) for seeds of the bip, sdf2, and lpr1 lpr2 mutants, respectively.

Contributor Information

Jonatan Montpetit, Department of Plant Molecular Biology, Biophore Building, University of Lausanne, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland.

Joaquín Clúa, Department of Plant Molecular Biology, Biophore Building, University of Lausanne, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland.

Yi-Fang Hsieh, Department of Plant Molecular Biology, Biophore Building, University of Lausanne, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland.

Evangelia Vogiatzaki, Department of Plant Molecular Biology, Biophore Building, University of Lausanne, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland.

Jens Müller, Department of Molecular Signal Processing, Leibniz Institute of Plant Biochemistry, 06120 Halle, Germany.

Steffen Abel, Department of Molecular Signal Processing, Leibniz Institute of Plant Biochemistry, 06120 Halle, Germany.

Richard Strasser, Department of Applied Genetics and Cell Biology, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, Muthgasse 18, A-1190 Vienna, Austria.

Yves Poirier, Department of Plant Molecular Biology, Biophore Building, University of Lausanne, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland.

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Phenotype of the cnx1 cnx2 double mutant under high and low Pi conditions.

Supplemental Figure S2. Localization of CNX1::CNX1-GFP and CNX2::CNX2-GFP in the ER.

Supplemental Figure S3. Amino acid alignment between the CNX2 and CRT3 of Arabidopsis and the mouse CRT3.

Supplemental Table S1. List of mutants used in this work.

Supplemental Table S2. Primer list.

Funding information

This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation (Schweizerische Nationalfonds) grants 31003A-182462 and 31003A-159998 to Y.P.

References

- Ames BN (1966) Assay of inorganic phosphate, total phosphate and phosphatases. Methods Enzymol 8: 115–118 [Google Scholar]

- Balzergue C, Dartevelle T, Godon C, Laugier E, Meisrimler C, Teulon JM, Creff A, Bissler M, Brouchoud C, Hagege A, et al. (2017) Low phosphate activates STOP1-ALMT1 to rapidly inhibit root cell elongation. Nature Commun 8(1): 15300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Herrera F, Moreno AA, Tapia R, Reyes F, Araya M, D'Alessio C, Parodi A, Orellana A (2015) The UDP-glucose: glycoprotein glucosyltransferase (UGGT), a key enzyme in ER quality control, plays a significant role in plant growth as well as biotic and abiotic stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol 15(1): 127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloemeke N, Meighen-Berger K, Hitzenberger M, Bach NC, Parr M, Coelho JP, Frishman D, Zacharias M, Sieber SA, Feige MJ (2022) Intramembrane client recognition potentiates the chaperone functions of calnexin. EMBO J 41(24): e110959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandizzi F (2021) Maintaining the structural and functional homeostasis of the plant endoplasmic reticulum. Dev Cell 56(7): 919–932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burn JE, Hurley UA, Birch RJ, Arioli T, Cork A, Williamson RE (2002) The cellulose-deficient Arabidopsis mutant rsw3 is defective in a gene encoding a putative glucosidase II, an enzyme processing N-glycans during ER quality control. Plant J 32(6): 949–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Yu FF, Xie Q (2020) Insights into endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation in plants. New Phytol 226(2): 345–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen A, Svensson K, Thelin L, Zhang WJ, Tintor N, Prins D, Funke N, Michalak M, Schulze-Lefert P, Saijo Y, et al. (2010) Higher plant calreticulins have acquired specialized functions in Arabidopsis. PLoS One 5(6): e11342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16(6): 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colon-Carmona A, You R, Haimovitch-Gal T, Doerner P (1999) Spatio-temporal analysis of mitotic activity with a labile cyclin-GUS fusion protein. Plant J 20(4): 503–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crombez H, Motte H, Beeckman T (2019) Tackling plant phosphate starvation by the roots. Dev Cell 48(5): 599–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Humbert S, Liu JX, Srivastava R, Rothstein SJ, Howell SH (2011) Heat induces the splicing by IRE1 of a mRNA encoding a transcription factor involved in the unfolded protein response in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108(17): 7247–7252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dissanayaka DMSB, Ghahremani M, Siebers M, Wasaki J, Plaxton WC (2021) Recent insights into the metabolic adaptations of phosphorus-deprived plants. J Exp Bot 72(2): 199–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong JS, Pineros MA, Li XX, Yang HB, Liu Y, Murphy AS, Kochian LV, Liu D (2017) An Arabidopsis ABC transporter mediates phosphate deficiency-induced remodeling of root architecture by modulating iron homeostasis in roots. Mol Plant 10(2): 244–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farid A, Pabst M, Schoberer J, Altmann F, Glossl J, Strasser R (2011) Arabidopsis thaliana alpha1,2-glucosyltransferase (ALG10) is required for efficient N-glycosylation and leaf growth. Plant J 68(2): 314–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao HB, Brandizzi F, Benning C, Larkin RM (2008) A membrane-tethered transcription factor defines a branch of the heat stress response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105(42): 16398–16403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez-Alanis D, Yong-Villalobos L, Jimenez-Sandoval P, Alatorre-Cobos F, Oropeza-Aburto A, Mora-Macias J, Sanchez-Rodriguez F, Cruz-Ramirez A, Herrera-Estrella L (2017) Phosphate starvation-dependent iron mobilization induces CLE14 expression to trigger root meristem differentiation through CLV2/PEPR2 signaling. Dev Cell 41(5): 555–570.e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanikenne M, Esteves SM, Fanara S, Rouached H (2021) Coordinated homeostasis of essential mineral nutrients: a focus on iron. J Exp Bot 72(6): 2136–2153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helenius A, Aebi M (2004) Roles of N-linked glycans in the endoplasmic reticulum. Annu Rev Biochem 73(1): 1019–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z, Jin H, Tzfira T, Li JM (2008) Multiple mechanism-mediated retention of a defective brassinosteroid receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20(12): 3418–3429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z, Kajiura H, Su W, Jin H, Kimura A, Fujiyama K, Li JM (2012) Evolutionarily conserved glycan signal to degrade aberrant brassinosteroid receptors in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109(28): 11437–11442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung IC, Cherng BW, Hsu WM, Lee SJ (2013) Calnexin is required for zebrafish posterior lateral line development. Int J Dev Biol 57(5): 427–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttner S, Veit C, Vavra U, Schoberer J, Liebminger E, Maresch D, Grass J, Altmann F, Mach L, Strasser R (2014) Arabidopsis class I alpha-mannosidases MNS4 and MNS5 are involved in endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of misfolded glycoproteins. Plant Cell 26(4): 1712–1728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Hong Z, Su W, Li JM (2009) A plant-specific calreticulin is a key retention factor for a defective brassinosteroid receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(32): 13612–13617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H, Yan Z, Nam KH, Li JM (2007) Allele-specific suppression of a defective brassinosteroid receptor reveals a physiological role of UGGT in ER quality control. Mol Cell 26(6): 821–830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi R, Paul M, Kumar A, Pandey D (2019) Role of calreticulin in biotic and abiotic stress signalling and tolerance mechanisms in plants. Gene 714: 144004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajiura H, Seki T, Fujiyama K (2010) Arabidopsis thaliana alg3 mutant synthesizes immature oligosaccharides in the ER and accumulates unique N-glycans. Glycobiology 20(6): 736–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor M, Ellgaard L, Gopalakrishnapai J, Schirra C, Gemma E, Oscarson S, Helenius A, Surolia A (2004) Mutational analysis provides molecular insight into the carbohydrate-binding region of calreticulin: pivotal roles of tyrosine-109 and aspartate-135 in carbohydrate recognition. Biochemistry 43(1): 97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Nguyen NH, Nguyen NT, Hong SW, Lee H (2013) Loss of all three calreticulins, CRT1, CRT2 and CRT3, causes enhanced sensitivity to water stress in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep 32(12): 1843–1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koiwa H, Li F, McCully MG, Mendoza I, Koizumi N, Manabe Y, Nakagawa Y, Zhu JH, Rus A, Pardo JM, et al. (2003) The STT3a subunit isoform of the Arabidopsis oligosaccharyltransferase controls adaptive responses to salt/osmotic stress. Plant Cell 15(10): 2273–2284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov G, Gehring K (2020) Calnexin cycle – structural features of the ER chaperone system. FEBS J 287(20): 4322–4340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov G, Pocanschi CL, Rosenauer A, Bastos-Aristizabal S, Gorelik A, Williams DB, Gehring K (2010) Structural basis of carbohydrate recognition by calreticulin. J Biol Chem 285(49): 38612–38620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus A, Groenendyk J, Bedard K, Baldwin TA, Krause KH, Dubois-Dauphin M, Dyck J, Rosenbaum EE, Korngut L, Colley NJ, et al. (2010) Calnexin deficiency leads to dysmyelination. J Biol Chem 285(24): 18928–18938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde D, Basset M, Lepetit M, Conejero G, Gaymard F, Astruc S, Grignon C (1996) Tissue-specific expression of Arabidopsis AKT1 gene is consistent with a role in K+ nutrition. Plant J 9(2): 195–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Zhao-Hui C, Batoux M, Nekrasov V, Roux M, Chinchilla D, Zipfel C, Jones JDG (2009) Specific ER quality control components required for biogenesis of the plant innate immune receptor EFR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(37): 15973–15978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J-X, Howell SH (2010) Endoplasmic reticulum protein quality control and its relationship to environmental stress responses in plants. Plant Cell 22(9): 2930–2942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J-X, Howell SH (2016) Managing the protein folding demands in the endoplasmic reticulum of plants. New Phytol 211(2): 418–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YD, Li JM (2013) An in vivo investigation of amino acid residues critical for the lectin function of Arabidopsis calreticulin 3. Mol Plant 6(3): 985–987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu DYT, Smith PMC, Barton DA, Day DA, Overall RL (2017) Characterisation of Arabidopsis calnexin 1 and calnexin 2 in the endoplasmic reticulum and at plasmodesmata. Protoplasma 254(1): 125–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu DP, Christopher DA (2008) Endoplasmic reticulum stress activates the expression of a sub-group of protein disulfide isomerase genes and AtbZIP60 modulates the response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Genet Genomics 280(3): 199–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Tintor N, Mentzel T, Kombrink E, Boller T, Robatzek S, Schulze-Lefert P, Saijo Y (2009) Uncoupling of sustained MAMP receptor signaling from early outputs in an Arabidopsis endoplasmic reticulum glucosidase II allele. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(52): 22522–22527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manghwar H, Li J (2022) Endoplasmic reticulum stress and unfolded protein response signaling in plants. Int J Mol Sci 23(2): 828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama D, Sugiyama T, Endo T, Nishikawa S (2014) Multiple BiP genes of Arabidopsis thaliana are required for male gametogenesis and pollen competitiveness. Plant Cell Physiol 55(4): 801–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna MJ, Sim SI, Ordureau A, Wei LJ, Harper JW, Shao SC, Park E (2020) The endoplasmic reticulum P5A-ATPase is a transmembrane helix dislocase. Science 369(6511): eabc5809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora-Macias J, Ojeda-Rivera JO, Gutierrez-Alanis D, Yong-Villalobos L, Oropeza-Aburto A, Raya-Gonzalez J, Jimenez-Dominguez G, Chavez-Calvillo G, Rellan-Alvarez R, Herrera-Estrella L (2017) Malate-dependent Fe accumulation is a critical checkpoint in the root developmental response to low phosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114(17): E3563–E3572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J, Toev T, Heisters M, Teller J, Moore KL, Hause G, Dinesh DC, Burstenbinder K, Abel S (2015) Iron-dependent callose deposition adjusts root meristem maintenance to phosphate availability. Dev Cell 33(2): 216–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumann C, Heisters M, Brandt W, Janitza P, Alfs C, Tang N, Nienguesso AT, Ziegler J, Imre R, Mechtler K, et al. (2022) Bacterial-type ferroxidase tunes iron-dependent phosphate sensing during Arabidopsis root development. Curr Biol 32(10): 2189–2205.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumann C, Mueller J, Sakhonwasee S, Wieghaus A, Hause G, Heisters M, Buerstenbinder K, Abel S (2019) The local phosphate deficiency response activates endoplasmic reticulum stress-dependent autophagy. Plant Physiol 179(2): 460–476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nekrasov V, Li J, Batoux M, Roux M, Chu ZH, Lacombe S, Rougon A, Bittel P, Kiss-Papp M, Chinchilla D, et al. (2009) Control of the pattern-recognition receptor EFR by an ER protein complex in plant immunity. EMBO J 28(21): 3428–3438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussaume L, Desnos T (2022) “Je t'aime moi non plus”: a love-hate relationship between iron and phosphate. Mol Plant 15(1): 1–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CJ, Park JM (2019) Endoplasmic reticulum plays a critical role in integrating signals generated by both biotic and abiotic stress in plants. Front Plant Sci 10: 399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parlati F, Dignard D, Bergeron JJM, Thomas DY (1995) The calnexin homolog cnx1(+) in Schizosaccharomyces pombe, is an essential gene which can be complemented by its soluble ER domain. EMBO J 14(13): 3064–3072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persson S, Rosenquist M, Svensson K, Galvao R, Boss WF, Sommarin M (2003) Phylogenetic analyses and expression studies reveal two distinct groups of calreticulin isoforms in higher plants. Plant Physiol 133(3): 1385–1396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poirier Y, Jaskolowski A, Clua J (2022) Phosphate acquisition and metabolism in plants. Curr Biol 32(12): R623–R629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Impellizzeri S, Moreno AA (2021) The endoplasmic reticulum role in the plant response to abiotic stress. Front Plant Sci 12: 755447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephani M, Picchianti L, Gajic A, Beveridge R, Skarwan E, Hernandez VSD, Mohseni A, Clavel M, Zeng YL, Naumann C, et al. (2020) A cross-kingdom conserved ER-phagy receptor maintains endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis during stress. Elife 9: e58396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser R (2018) Protein quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum of plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 69(1): 147–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun TJ, Zhang Q, Gao MH, Zhang YL (2014) Regulation of SOBIR1 accumulation and activation of defense responses in bir1-1 by specific components of ER quality control. Plant J 77(5): 748–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svistoonoff S, Creff A, Reymond M, Sigoillot-Claude C, Ricaud L, Blanchet A, Nussaume L, Desnos T (2007) Root tip contact with low-phosphate media reprograms plant root architecture. Nat Genet 39(6): 792–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson SP, Williams DB (2005) Delineation of the lectin site of the molecular chaperone calreticulin. Cell Stress Chaperon 10(3): 242–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ticconi CA, Abel S (2004) Short on phosphate: plant surveillance and countermeasures. Trends Plant Sci 9(11):548–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ticconi CA, Delatorre CA, Lahner B, Salt DE, Abel S (2004) Arabidopsis pdr2 reveals a phosphate-sensitive checkpoint in root development. Plant J 37(6): 801–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ticconi C, Lucero R, Sakhonwasee S, Adamson A, Creff A, Nussaume L, Desnos T, Abel S (2009) ER-resident proteins PDR2 and LPR1 mediate the developmental response of root meristems to phosphate availability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(33): 14174–14179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursache R, Andersen TG, Marhavy P, Geldner N (2018) A protocol for combining fluorescent proteins with histological stains for diverse cell wall components. Plant J 93(2): 399–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu KV, Nguyen VT, Jeong CY, Lee YH, Lee H, Hong SW (2017) Systematic deletion of the ER lectin chaperone genes reveals their roles in vegetative growth and male gametophyte development in Arabidopsis. Plant J 89(5): 972–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XY, Wang Z, Zheng Z, Dong JS, Song L, Sui LQ, Nussaume L, Desnos T, Liu D (2019) Genetic dissection of Fe-dependent signaling in root developmental responses to phosphate deficiency. Plant Physiol 179(1): 300–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X, Chen CY, Yu TM, Ou JY, Rui ML, Zhai YF, He YJ, Xue L, Ho MS (2017) Molecular chaperone calnexin regulates the function of Drosophila sodium channel paralytic. Front Mol Neurosci 10: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshitake Y, Nakamura S, Shinozaki D, Izumi M, Yoshimoto K, Ohta H, Shimojima M (2021) RCB-mediated chlorophagy caused by oversupply of nitrogen suppresses phosphate-starvation stress in plants. Plant Physiol 185(2): 318–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.