Abstract

SPINDLY (SPY) is a novel nucleocytoplasmic protein O-fucosyltransferase that regulates target protein activity or stability via O-fucosylation of specific Ser/Thr residues. Previous genetic studies indicate that AtSPY regulates plant development during vegetative and reproductive growth by modulating gibberellin and cytokinin responses. AtSPY also regulates the circadian clock and plant responses to biotic and abiotic stresses. The pleiotropic phenotypes of spy mutants point to the likely role of AtSPY in regulating key proteins functioning in diverse cellular pathways. However, very few AtSPY targets are known. Here, we identified 88 SPY targets from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and Nicotiana benthamiana via the purification of O-fucosylated peptides using Aleuria aurantia lectin followed by electron transfer dissociation-MS/MS analysis. Most AtSPY targets were nuclear proteins that function in DNA repair, transcription, RNA splicing, and nucleocytoplasmic transport. Cytoplasmic AtSPY targets were involved in microtubule-mediated cell division/growth and protein folding. A comparison with the published O-linked-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) proteome revealed that 30% of AtSPY targets were also O-GlcNAcylated, indicating that these distinct glycosylations could co-regulate many protein functions. This study unveiled the roles of O-fucosylation in modulating many key nuclear and cytoplasmic proteins and provided a valuable resource for elucidating the regulatory mechanisms involved.

Introduction

SPINDLY (SPY) in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) (AtSPY) was identified through mutant screens for suppressors of phytohormone gibberellin (GA)-deficient phenotypes (Jacobsen and Olszewski, 1993; Silverstone et al., 1997). These early studies indicate that AtSPY functions as a repressor of GA signaling and that it inhibits all aspects of GA-regulated developmental processes, including seed germination, vegetative growth, floral induction, and anther development. Further characterization of hypomorphic spy mutants shows that AtSPY also regulates root development (Cui and Benfey, 2009; Mutanwad et al., 2020), functions as a positive regulator of phytohormone cytokinin signaling (Greenboim-Wainberg et al., 2005; Maymon et al., 2009), regulates the circadian clock (Tseng et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2020), and the plant's responses to biotic and abiotic stresses (Qin et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2019). These genetic studies indicate that AtSPY plays diverse roles in plant development. However, its biochemical function as a nucleocytoplasmic protein O-fucosyltransferase (POFUT) has only been recently uncovered (Zentella et al., 2017) and very few protein targets are known (Olszewski et al., 2010; Sun, 2021).

AtSPY and its paralog SECRET AGENT in Arabidopsis (AtSEC), both contain a tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) domain and a glycosyltransferase catalytic domain that is similar to the animal O-linked-N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) transferase (OGT) (Jacobsen et al., 1996; Hartweck et al., 2002; Olszewski et al., 2010; Hart et al., 2011). Our biochemical analysis showed that AtSEC is an OGT, which O-GlcNAcylates Ser/Thr residues of target proteins (Zentella et al., 2016). Surprisingly, AtSPY is a protein O-fucosyltransferase (POFUT), which O-fucosylates Ser/Thr residues of target proteins (Zentella et al., 2017). AtSPY is a novel nucleocytoplasmic-localized POFUT (Swain et al., 2002; Zentella et al., 2017), which is distinct from endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-localized POFUTs in animals that modify secreted cell surface proteins to promote protein folding and/or ligand binding (Valero-Gonzalez et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017; Holdener and Haltiwanger, 2019). Interestingly, AtSPY and AtSEC play opposite roles in regulating DELLAs, key transcription regulators in GA signaling (Zentella et al., 2016, 2017). DELLAs are master growth repressors, which coordinate multiple signaling activities by protein–protein interactions with key transcription factors in response to internal and external cues (Sun, 2011; Daviere and Achard, 2016). For example, DELLAs inhibit hypocotyl growth by sequestering key transcription factors (BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT1 [BZR1] and PHYTOCHROME-INTERACTING-FACTORs [e.g. PIF3 and PIF4]) that promote hypocotyl elongation in response to the phytohormone brassinosteroid (BR) and external light conditions (de Lucas et al., 2008; Feng et al., 2008; Bai et al., 2012). AtSPY-mediated O-fucosylation of DELLA enhances its binding to BZR1 and PIFs (Zentella et al., 2017), whereas O-GlcNAcylation of DELLA by AtSEC reduces DELLA-BZR1/PIFs interactions (Zentella et al., 2016). Thus, AtSPY and AtSEC differentially modulate DELLA activity, which, in turn, alters GA, BR, and light signaling pathways to regulate plant growth and development.

The functional interplay between AtSPY and AtSEC is complex and may depend on the target proteins and developmental processes. As described above, AtSPY and AtSEC play opposite roles in regulating AtDELLA-mediated signaling activities (Zentella et al., 2016, 2017). Similarly, AtSPY and AtSEC oppositely regulate a splicing factor, ACINUS, in alternative splicing of selected target genes (Bi et al., 2021), although the regulatory mechanism is unclear. In contrast, AtSPY and AtSEC appear to additively regulate embryo development as the spy sec double mutant is embryo-lethal (Hartweck et al., 2002, 2006). In addition, both spy and sec Arabidopsis mutants flower earlier than the wild-type (WT) (Jacobsen and Olszewski, 1993; Silverstone et al., 2007; Xing et al., 2018). However, AtSPY delays flowering by enhancing DELLA activity, as well as by regulating the circadian clock (Tseng et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2020), while AtSEC inhibits flowering by inducing expression of the master flowering repressor FLC (Xing et al., 2018). Intriguingly, AtSPY, but not AtSEC, uniquely regulates cytokinin responses and circadian rhythms. The spy mutants exhibit reduced cytokinin responses, including reduced leaf serration and fewer sepal trichomes (Greenboim-Wainberg et al., 2005; Maymon et al., 2009). Two bHLH transcription factors, TCP14 and TCP15, interact with AtSPY in regulating cytokinin responses (Steiner et al., 2012). TCP14 protein levels in Arabidopsis TCP14 overexpression lines are lower in the spy mutant than in the WT, suggesting that SPY promotes cytokinin signaling by preventing TCP14 degradation (Steiner et al., 2016, 2021). In addition, the spy mutants confer a longer circadian period than the WT (Tseng et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2020). Further biochemical analysis showed that AtSPY O-fucosylates and destabilizes the transcription repressor PSEUDO RESPONSE REGULATOR 5 (PRR5), a key regulator of circadian clock speed (Tseng et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2020). SPY also promotes abscisic acid signaling by modifying a co-chaperonin CPN20 and inhibits CPN20 translocation into the chloroplast (Liang et al., 2021).

Phylogenetic analysis indicates that all plants contain both SPY and SEC genes but that metazoans and fungi only contain SEC-Like (OGT) genes & nbsp; (Olszewski et al. 2010). The roles of OGT in animals have been studied extensively, and it regulates intracellular processes, including transcription, translation, protein stability, activity, and subcellular localization (Bond and Hanover, 2015; Hart, 2019). In contrast, the functions of POFUT (SPY) and OGT (SEC) in plants are largely unknown. The pleiotropic phenotypes of spy and sec mutants suggest that AtSPY and AtSEC may modify many key regulators in diverse biological processes. Consistent with this idea, recent proteomic studies have identified 262 O-GlcNAcylated Arabidopsis proteins and 168 in winter wheat Triticum aestivum, many of which function in transcriptional regulation, RNA processing, translation, and metabolic processes (Xu et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2019). However, the known protein substrates of AtSPY only include DELLAs (master growth repressors), PRR5 (a circadian clock component; Wang et al., 2020), ACINUS (an RNA splicing factor; Bi et al., 2021), and CPN20 (a chloroplast co-chaperonin; Liang et al., 2021).

In this study, the global functions of SPY in plants were investigated using a proteomic approach. O-fucosylated proteins from Arabidopsis were enriched by pull-down assays using Aleuria aurantia lectin (AAL) that binds terminal fucose at high affinity (Bandini et al., 2016), followed by liquid chromatography-electron transfer dissociation (LC–ETD)-MS/MS analysis. We have identified 114 peptides that belong to 20 Arabidopsis proteins, including nuclear proteins that function in transcription, DNA repair, RNA splicing, as well as cytoplasmic proteins involved in cell division, cell growth, and protein folding. To identify additional SPY targets, we transiently expressed AtSPY in Nicotiana benthamiana to enhance global protein O-fucosylation and identified 68 O-fucosylated N. benthamiana proteins. The majority of O-fucosylated proteins are nuclear-localized, revealing the key roles of SPY in regulating gene expression in the nucleus. In addition, 30% of these O-fucosylated proteins are also O-GlcNAcylated by AtSEC, indicating that SPY and SEC share many protein substrates. We also showed that the transient co-expression system in N. benthamiana provides an efficient platform for identifying potential enzyme targets and for assaying POFUT and OGT activities.

Results

Identification of O-fucosylated Arabidopsis proteins using AAL pull-down and MS analysis

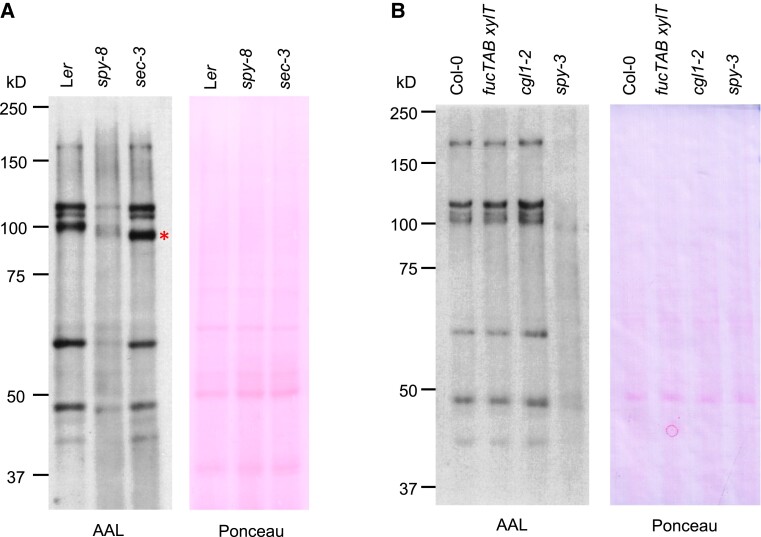

We first assessed the effectiveness of AAL (a terminal fucose-specific lectin) to detect O-fucosylated proteins in Arabidopsis protein extracts by protein blot analysis using biotinylated AAL (Figure 1). Nuclear fractions from WT, spy, and sec mutants were analyzed in Figure 1A. WT (Ler ecotype) displayed a set of AAL-detected strong protein bands, while the spy-8 mutant showed very little signals on the AAL blot. We also analyzed the sec-3 mutant extract by AAL blotting to determine whether impaired OGT may affect global protein O-fucosylation because co-expression of SPY and SEC compete with each other in reciprocal modification of RGA in N. benthamiana (Zentella et al., 2017). The AAL blot analysis showed that sec-3 displayed similar overall O-fucosylation patterns as in WT (Figure 1A). Interestingly, the 100 kD protein band in WT appeared to shift to faster mobility in spy-8 and sec-3, suggesting that O-fucosylation may promote O-GlcNAcylation of this protein because increased O-GlcNAcylation results in reduced gel mobility (Zentella et al., 2016). In addition, nuclear fractions of Ler and sec-3 contained more O-fucosylated proteins than the cytoplasmic/chloroplast fraction (Supplemental Figure 1). Similarly, the spy-3 allele in the Col-0 ecotype background almost completely abolished AAL-detected signals in comparison to the WT (Col-0) (Figure 1B). These results indicate that AAL blot analysis is effective in detecting protein O-fucosylation in WT Arabidopsis extracts.

Figure 1.

Detection of O-fucosylated proteins in nuclear fractions of WT Arabidopsis and mutants by AAL blot analysis. Immunoblots contained nuclear protein extracts from WT, and different mutants as labeled. The blots were probed with AAL-biotin, followed by HRP-streptavidin. In A, ecotype Ler is the WT control. The asterisk indicates the band that is shifted to faster mobility in sec-3. In B, ecotype Col-0 is the WT control. fucTAB xylT, the fucTA fucTB xylT triple mutant. The image of the Ponceau-staining blot shows similar loading. Representative images of 2 biological repeats are shown.

In plants, fucosylation is abundantly present in N-glycan-containing proteins on the cell surface and in the cell wall through the activity of ER or Golgi-localized glycosyltransferases (Strasser, 2016). To reduce the background due to N-fucosylated proteins, we obtained the Arabidopsis complex glycan1 (cgl1) mutant and the fucTA fucTB XylT triple mutant, both of which are impaired in complex N-glycan maturation. CGL1 encodes N-acetyl glucosaminyl transferase I, which catalyzes an early key step in the synthesis of complex N-glycan on glycoproteins, and the cgl1 mutation should result in the lack of fucosylation of N-glycan (von Schaewen et al., 1993; Frank et al., 2008). The fucTA fucTB XylT triple null mutant is defective in β1,2-xylosyltransferase (XylT) and two fucosyltransferases (FucTA and FucTB), which are required for the addition of 1,3-linked fucose (the main fucose in plant glycans) to the N-glycan on glycoproteins (Strasser et al., 2004). Interestingly, nuclear fractions of these mutants did not show obvious changes in the overall signals on the AAL blot compared to the WT sample (Figure 1B). This could be due to much reduced N-glycosylated proteins in the nuclear fractions and the detection limit of the AAL blot for only highly fucosylated proteins (see below).

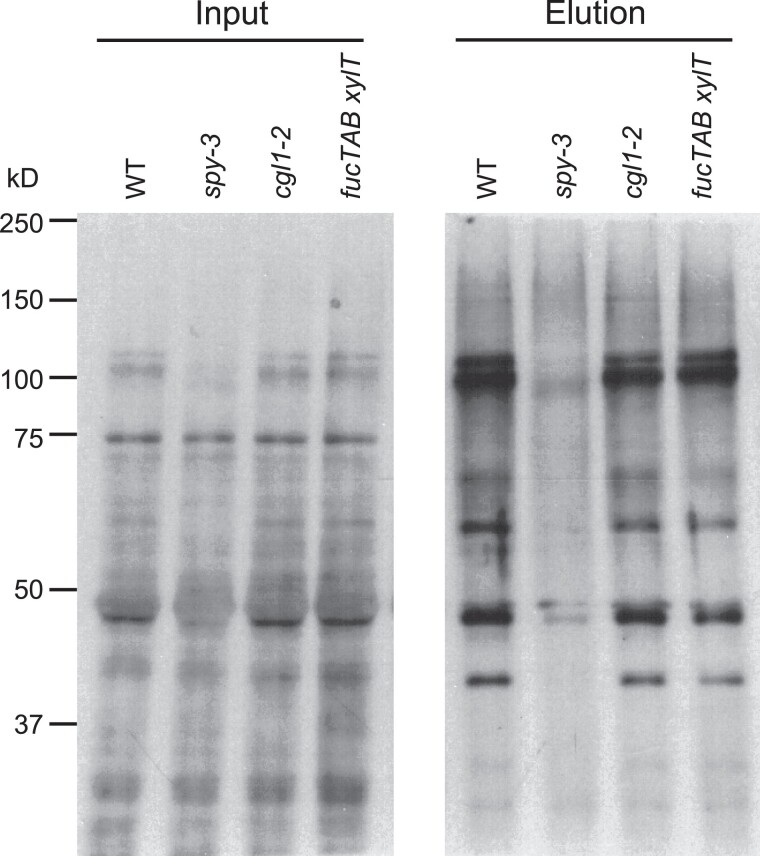

We then performed in vitro pull-down assays using AAL-agarose to purify O-fucosylated proteins from Arabidopsis total or nuclear protein extracts and then followed by AAL blot analysis. Again, the pull-down proteins from Col-0 (WT), cgl1 and fucTA fucTB XylT mutants showed similar signals on the AAL blot (Figure 2 and Supplemental Figure 2). These results indicated that AAL–agarose was effective in pulling down O-fucosylated proteins from Arabidopsis total or nuclear protein extracts. Although the cgl1 mutant did not show reduced background in our AAL blot analysis, this mutant should still help to lower the N-glycosylated protein contaminants for the ETD–MS/MS analysis, which is much more sensitive than the AAL blot. Therefore, to prepare samples for MS analysis, we used the cgl1 mutant seedlings and enriched for O-fucosylated peptides from trypsin-digested total protein extracts or nuclear fractions by AAL–agarose pull-down. The use of nuclear fraction should further enrich for nuclear-localized O-fucosylated proteins and reduce the amounts of the N-glycosylated proteins as AAL can bind to non-fucose sugars (e.g. arabinose) at lower affinities (Fukumori et al., 1990; Ogawa et al., 2001). After AAL pull-down, peptide samples were analyzed by ETD–MS/MS analysis to detect O-fucosylated peptides and to map the modification sites. We identified 114 O-fucosylated peptides (including 27 peptides with mapped O-Fuc sites), which correspond to 20 Arabidopsis proteins (Table 1 and Supplemental Tables 1 and 2, Supplemental Data set 1–set 6). We noticed that most of these peptides contain 2 or 3 O-fucosylated residues, suggesting that highly fucosylated peptides bind more strongly to AAL. This finding is consistent with the structure of AAL, which consists of five fucose binding sites (Fujihashi et al., 2003). Seventeen of the 20 identified SPY targets are nuclear proteins, even when we used samples purified from total protein extracts without nuclear fractionation (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 1). Although our Arabidopsis O-Fuc protein dataset is limited, these results suggested that SPY-regulated cellular functions are localized mostly to the nucleus.

Figure 2.

Pull-down of O-fucosylated proteins from total extracts of WT Arabidopsis and mutants. Immunoblots contained input (left panel) or AAL–agarose pull-down proteins from total protein extracts (right panel) from WT, and different mutants as labeled. The blots were probed with AAL-biotin, followed by HRP-streptavidin. Representative images of two biological repeats are shown.

Table 1.

O-fucosylated Arabidopsis proteins identified by AAL pull-down and MS analysis

| O-Fuc proteins | Biochemical function | Physiological function |

References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleus | |||

| NUP1a, 58, 62, 98A, 214a | Nuclear pore complex | Transport across nuclear envelope | Tamura et al. (2010) |

| TCP8a, 9, 14a, 15, 21 | Transcription factors | Plant development, hormone responses | Danisman (2016) |

| IDD4, 5a | Transcription factors | Plant development and immunity | Colasanti et al. (2006), Yoshida et al. (2014), Volz et al. (2019) |

| PHR1 | Transcription factor | Phosphate starvation response | Rubio et al. (2001), Bustos et al. (2010) |

| TAF12 | Transcription initiation factor | RNA Pol II preinitiation complex assembly | Lago et al. (2004) |

| SUA | RNA splicing factor | Rescue abi3-5 | Sugliani et al. (2010) |

| PHD | Protein transport/targeting | Interact with NUP82 | Scheffzek and Welti (2012), Tamura et al. (2017) |

| APE2 | DNA repair enzyme | Base excision repair | Li et al. (2018) |

| Cytoplasm | |||

| NEDD1a | Microtubule binding | Cell division | Zeng et al. (2009) |

| CLASP | Microtubule binding | Cell division, cell expansion | Ambrose et al. (2007) |

| PapD-like | Protein chaperone | Protein folding | Vetsch et al. (2004) |

The protein is also O-GlcNAcylated, as reported by Xu et al. (2017).

Among the O-fucosylated nuclear proteins, five are nucleoporins (NUPs: NUP1, 58, 62, 98A, 214) that are nuclear pore complex components for controlling nucleocytoplasmic transport of macromolecules (Tamura et al., 2010; Raices and D’Angelo, 2012), and eight are from three distinct classes of transcription factors (TEOSINTE BRANCHED 1, CYCLOIDEA, PCF1s [TCPs], INDETERMINATE DOMAINs [IDDs], and PHOSPHATE STARVATION RESPONSE 1 [PHR1]) (Table 1). The five Class I TCPs (TCP8, 9, 14, 15, 21) are non-canonical bHLH transcription factors (Martin-Trillo and Cubas, 2010; Danisman, 2016), which promote cell proliferation and regulate the development of organs (e.g. leaf, stem, flower). The two IDDs (IDD4 and IDD5) are members of the IDD subfamily of C2H2 zinc finger transcription factors, which regulate root patterning, starch synthesis, and plant immunity (Colasanti et al., 2006; Moreno-Risueno et al., 2015; Volz et al., 2019). PHR1, a member of the MYB-coiled-coil (MYB-CC) family of transcription factors, is a master activator of the phosphate starvation response genes (Rubio et al., 2001; Bustos et al., 2010). Other nuclear proteins include TBP-ASSOCIATED FACTOR 12 (TAF12) for RNA Pol II preinitiation complex assembly (Lago et al., 2004), a Pleckstrin Homology (PH) Domain protein (PHD) for protein transport/targeting (Scheffzek and Welti, 2012), SUPPRESSOR OF abi3-5 (SUA, a splicing factor) (Sugliani et al., 2010), and APURINIC/APYRIMIDINIC ENDONUCLEASE2 (APE2, a base excision repair enzyme) (Li et al., 2018) (Table 1). We also identified three cytoplasmic-localized SPY targets: NEDD1, a microtubule-binding WD40 repeat protein (Zeng et al., 2009); CLASP (CLIP-associated protein), a microtubule-associated protein that is involved in both cell division and cell expansion (Ambrose et al., 2007), and a PapD-like protein that may function as a chaperone for protein folding (Vetsch et al., 2004).

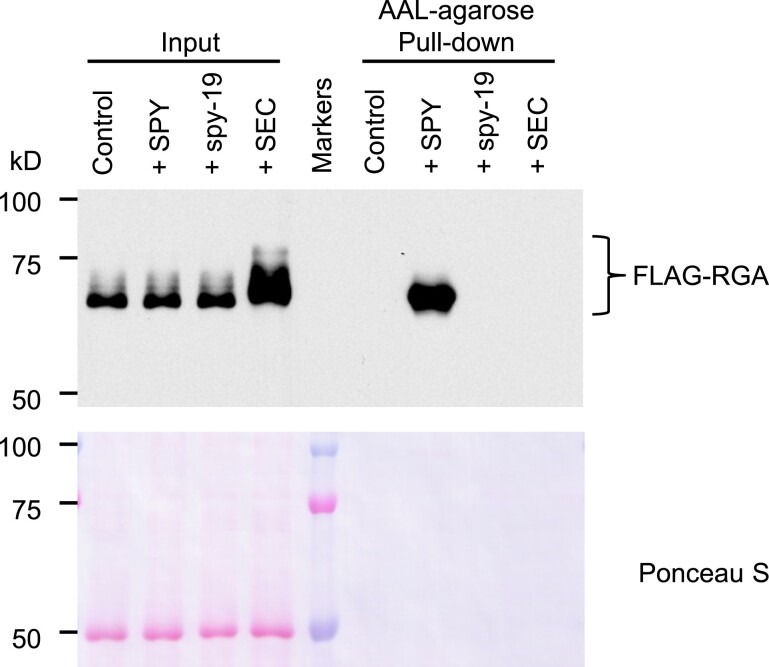

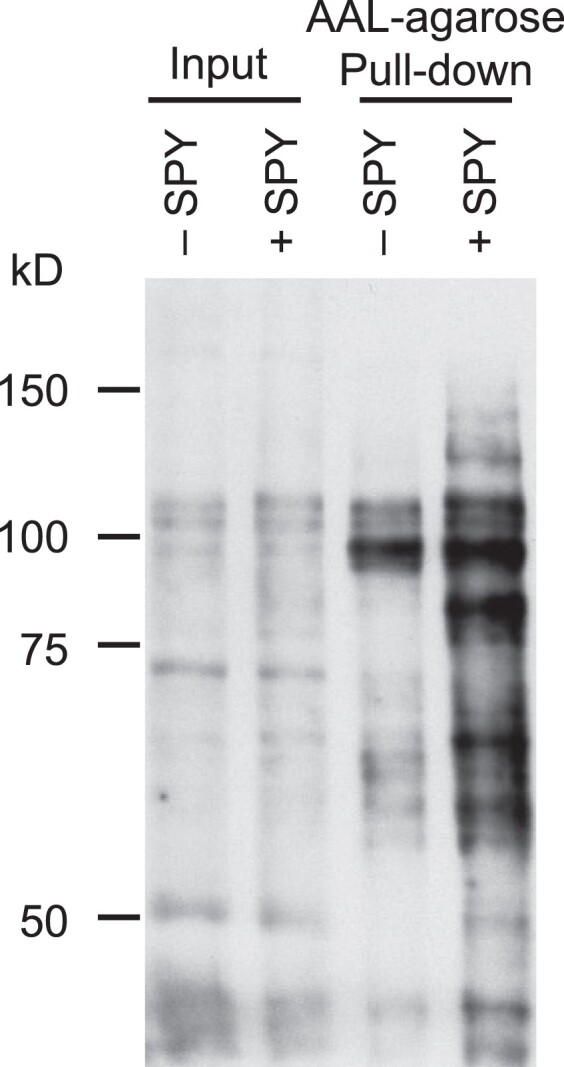

Identification of O-fucosylated N. benthamiana proteins

In an attempt to identify additional SPY targets, we took advantage of the transient expression system in N. benthamiana, which we have previously developed for POFUT activity assay by transient co-expression of target proteins with AtSPY. Using this system, we have shown that FLAG-RGA is highly O-fucosylated by AtSPY by MS analysis (Zentella et al., 2017). The sequences of SPY orthologs are highly conserved in plants. Therefore, we reasoned that overexpression of AtSPY in N. benthamiana should result in elevated O-fucosylation of endogenous N. benthamiana proteins. To test this idea, we transiently expressed 35S:Myc-AtSPY (+SPY) in N. benthamiana and performed AAL–agarose pull-down to enrich for O-fucosylated proteins. AAL blot analysis showed that the + SPY pull-down sample displayed dramatically increased global protein O-fucosylation compared with the –SPY pull-down sample (Figure 3). To further examine the specificity of the AAL pull-down, we expressed FLAG-RGA alone or co-expressed FLAG-RGA with AtSPY or spy-19 (an inactive mutant protein) or AtSEC in N. benthamiana and then performed AAL–agarose pull-down. Immunoblot analysis using an anti-FLAG antibody showed that AAL only pull-downed FLAG-RGA from + SPY sample, indicating that AAL is highly specific to enrich for O-fucosylated proteins (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Expression of AtSPY in N. benthamiana dramatically increased global protein O-fucosylation. AtSPY was transiently expressed in N. benthamiana (+SPY), and total protein extracts of N. benthamiana (− or + SPY) were enriched for O-fucosylated proteins by in vitro pull-down using AAL–agarose. Immunoblot containing input or pull-downed proteins was probed with AAL-biotin and detected with HRP-streptavidin. Representative images of 2 biological repeats are shown.

Figure 4.

Detection of O-fucosylated FLAG-RGA by AtSPY using transient expression system in N. benthamiana. FLAG-tagged RGA was expressed alone (control) or co-expressed with AtSPY, spy-19 (a hypomorphic allele) or AtSEC in N. benthamiana. O-fucosylated proteins were pull-downed by AAL–agarose. Immunoblot containing input or AAL–agarose pull-down samples was probed with an anti-FLAG antibody. Markers, protein molecular mass markers. The reduced FLAG-RGA mobility in the + SEC sample (α-FLAG blot) comparing to the other samples is due to O-GlcNAcylation (Zentella et al., 2016). Representative images of two biological repeats are shown.

To identify O-fucosylated N. benthamiana proteins by MS analysis, we applied the same purification procedure described above to enrich for O-fucosylated peptides using AAL–agarose and trypsin-digested total protein extracts from N. benthamiana that was transiently expressed with AtSPY. ETD–MS/MS analysis identified 68 O-fucosylated peptides (corresponding to 50 proteins), most of which were di- or tri-fucosylated (Supplemental Table 3). These results indicate that mono-fucosylated peptides are underrepresented in both Arabidopsis and N. benthamiana data sets (Supplemental Tables 1 and 3). In an effort to recover more mono-fucosylated peptides, we modified our purification procedure to pull-down O-fucosylated proteins by AAL–agarose prior to trypsin digestion, followed by MS analysis. We reasoned that AAL pull-down of undigested proteins may allow stronger binding of AAL to proteins that contain multiple mono-fucosylated residues that are not clustered within a single tryptic peptide. Indeed, with this modified method, we identified 35 O-fucosylated peptides (from 25 proteins), the majority of which were mono-fucosylated (Supplemental Table 3). In total, we have identified 103 O-fucosylated peptides (Supplemental Table 3, Supplemental Data set 7–set 9), which correspond to 68 O-fucosylated N. benthamiana proteins (Supplemental Table 4). A number of these N. benthamiana proteins are putative orthologs of O-fucosylated Arabidopsis proteins, including NUPs (NUP1, 62, 98a, 136a, 136b, 214), TCPs (TCP8, 14a, 14b, 20), SUA, NEDD1, CLASPs (CLASP-like-a, b, c). We also identified many new potential AtSPY targets (Supplemental Table 4). These include three classes of transcription factors: bHLHs (128-like, 130-like) (Bailey et al., 2003), WRKYs (31, 33a, 33b, 72) (Eulgem et al., 2000), and bZIP63-like involved in ABA and sugar signaling and circadian regulation (Matiolli et al., 2011; Frank et al., 2018). Other nuclear proteins involved in transcription regulation include MORPHEUS' MOLECULE1 (MOM1)-like transcription silencer (Amedeo et al., 2000), Modifier of SNC1-like (MOS1-like, for epigenetic regulation) (Li et al., 2010), TIME FOR COFFEE-like (TIC-like, for circadian regulation) (Ding et al., 2007), TOPLESS-related protein4 (TPR4)-like (transcription corepressor) (Long et al., 2006), VIP2-like (for transcription regulation) (Wang et al., 2013). We also identified several RNA remodeling/processing enzymes: Zinc finger C3H32-like and 58-like proteins for RNA-binding/processing (Wang et al., 2008), DEAD-box ATP-dependent RNA helicase 24, LARP1c-like for RNA binding/leaf senescence (Zhang et al., 2012), PUMILIO 2-like (PUM2-like, 3′-UTR RNA-binding protein that mediates post-transcriptional regulation) (Francischini and Quaggio, 2009), and VARICOSE (VCS)-like (mRNA decapping) (Xu et al., 2006). Additionally, we identified several ARF GTPase-activating proteins in the ARF-GAD family (AGD6, 8, 14) that are involved in vesicular transport (Vernoud et al., 2003). These results indicated that transient expression of AtSPY in this heterologous system could be employed to identify AtSPY targets effectively. Taken together, the O-Fuc proteomes in Arabidopsis and N. benthamiana revealed putative roles of protein O-fucosylation by SPY in modulating many key nuclear and cytoplasmic functions.

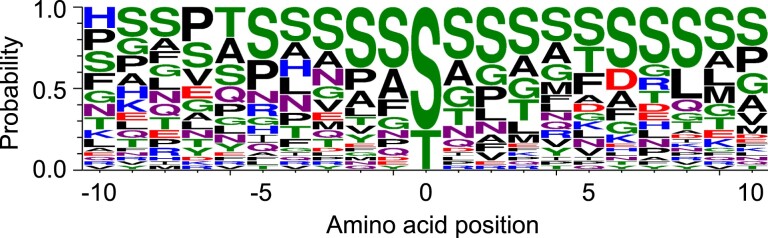

With a total of 37 mapped O-Fuc sites among the Arabidopsis and N. benthamiana proteins (Supplemental Table 2), we looked for preferred/consensus amino acid sequences around these modification sites by WebLogo (Schneider and Stephens, 1990; Crooks et al., 2004). Ser is the most frequent residue on both sides of the O-Fuc sites (+/− 10 positions), except for a slight preference of Thr at −6 and Pro at −7 position (Figure 5). This is in contrast to the OGT/SEC target sites with a strong preference for Val at −1 and Pro at −2 and −3 positions (Xu et al., 2017; Toleman et al., 2018).

Figure 5.

Sequence motifs around the O-Fuc sites. Sequence logo was generated using a total of 37 mapped O-fucosylated peptides in Arabidopsis (17) and N. benthamiana (20) with WebLogo. Each fucosylated S or T residue was placed at 0 position.

AtSPY and AtSEC share many protein substrates

Comparison of our O-Fuc Arabidopsis proteome dataset with the published O-GlcNAc Arabidopsis proteome (Xu et al., 2017) revealed that 30% of the O-fucosylated proteins are also O-GlcNAcylated, presumably by AtSEC (Table 1 and Supplemental Figure 3). Using the N. benthamiana O-Fuc proteome, we searched for the putative Arabidopsis orthologs by BLAST to identify potential AtSPY substrates, 40% of which are present in the O-GlcNAc proteome (Supplemental Table 4) (Xu et al., 2017). These results indicate that AtSPY and AtSEC co-regulate many target proteins.

Several IDDs (C2H2 transcription factors) and class I TCPs are either O-fucosylated or O-GlcNAcylated based on the proteomic studies (Table 1) (Xu et al., 2017). Only IDD5, TCP8, and TCP14 were found to be both O-Fuc and O-GlcNAc modified by MS analysis. The transcription initiation factor TAF12 was also identified as a SPY target. We tested TCP14, four IDDs (IDD1, 3, 5, 10) and TAF12 using the transient expression system in N. benthamiana to determine whether these proteins can be modified by both AtSPY and AtSEC. RGA (an AtDELLA) was included as a positive control in this co-expression system as it was shown to be O-fucosylated and O-GlcNAcylated by SPY and SEC, respectively (Zentella et al., 2016, 2017). GFP-NLS was also included as a negative control. Each selected target protein (FLAG-tagged) was co-expressed with Myc-tagged AtSPY or AtSEC, individually, and affinity-purified FLAG-tagged target proteins were analyzed by protein blot analysis using AAL-biotin (for detecting O-fucosylated proteins) or an anti-O-GlcNAc antibody (Figure 6). As expected, based on the proteomic data, RGA, TCP14, and IDD5 were modified by both SPY and SEC. Interestingly, IDD1, 3 and 10, and TAF12 were also modified by SPY and SEC, although IDD1 and IDD3 were absent in either O-GlcNAc or O-Fuc proteome, IDD10 was only found to be O-GlcNAcylated previously, and TAF12 was only present in O-Fuc proteome. These results suggest that most (if not all) IDDs are targets of SPY and SEC. In addition, we tested AtbHLH130 (FBH4), AtWRKY31, and AtC3H58, three putative Arabidopsis orthologs of the O-fucosylated N. benthamiana proteins identified from our proteomic MS analysis (Supplemental Table 4) and showed that they all were O-fucosylated and O-GlcNAcylated by AtSPY and AtSEC, respectively (Figure 6 and Supplemental Figure 4). These results further support that this heterologous system provides a robust tool for the identification of potential targets of AtSPY and AtSEC.

Figure 6.

AtSPY and AtSEC share common targets. FLAG-tagged proteins were expressed alone or co-expressed with AtSEC or AtSPY in N. benthamiana. RGA was included as a positive control, and GFP-NLS was used as a negative control. Immunoblots containing affinity-purified FLAG-tagged proteins were probed with either AAL-biotin or anti-O-GlcNAc antibody (CTD110.6) or anti-FLAG antibody as labeled. As shown in Supplemental Figure 4, AAL and anti-O-GlcNAc antibody displayed specificity for O-fucosylated and O-GlcNAcylated proteins, respectively. The blots for WRKY31 and C3H58 in this figure are the same as lanes 1–2 in Supplemental Figure 4. The reduced protein mobility in the + SEC samples (α-FLAG blots) comparing to the −SEC samples is due to O-GlcNAcylation. Representative images of two biological repeats are shown.

AtSPY promotes, whereas AtSEC reduces accumulation of TCP14 protein

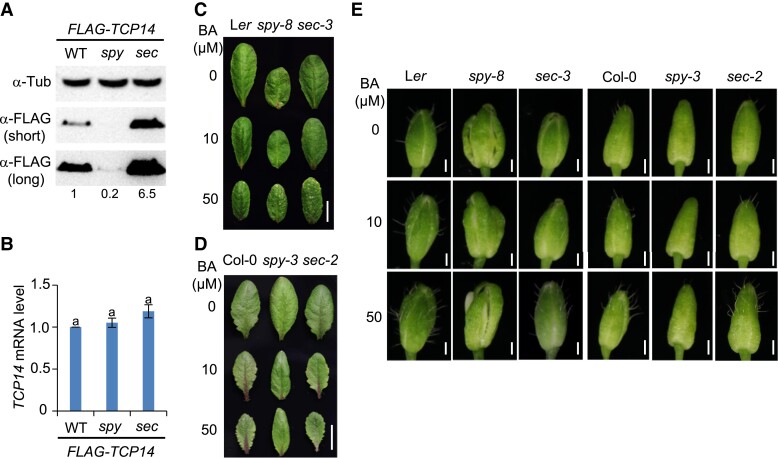

AtTCP14 and its paralog AtTCP15 are two functionally redundant bHLH transcription factors, which promote cell division in response to phytohormone cytokinin signaling (Kieffer et al., 2011; Steiner et al., 2012). Although single mutants do not display obvious phenotypes, the tcp14 tcp15 double mutant exhibits reduced cytokinin responses, including reduced leaf serration and internode length, and absence of trichomes on sepals. TCP14 was reported to be O-GlcNAcylated by SEC (Steiner et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2017). Previous studies also showed that TCP14 interacts with SPY, and TCP14 protein stability depends on SPY (Steiner et al., 2016). However, it has not been shown whether SPY O-fucosylates TCP14 directly, and whether SEC regulates the stability of TCP14. Our proteomics study found both TCP14 and TCP15 to be O-fucosylated by SPY (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 1, Figure 6). To investigate the effects of spy and sec mutations on TCP14 protein, we generated PUBQ10:FLAG-TCP14 transgenic Arabidopsis lines in the WT Ler background, and then crossed one representative line with spy-8 and sec-3, separately. Interestingly, accumulation of FLAG-TCP14 was reduced in spy but increased in sec in comparison to that in WT (Figure 7A), whereas TCP14 mRNA levels remained the same (Figure 7B). These results indicate that SPY and SEC oppositely affect TCP14 protein stability. As the spy mutants show reduced cytokinin responses, including reduced leaf serration and fewer sepal trichomes (Greenboim-Wainberg et al., 2005; Maymon et al., 2009), we compared the phenotypes of the sec-3 mutant (in the Ler background) after mock or 6-benzylaminopurine (BA) treatment with those of WT (Ler) and spy-8. Intriguingly, with mock treatment (0 μM BA), sec-3 displayed similar leaf serration as in Ler, although its flower buds did not produce trichomes, which is similar to spy-8 (Figure 7, C and E). However, in response to 10 and 50 μM BA treatments, the sec-3 mutant showed increased leaf serration and sepal trichome formation similar to Ler, which is in contrast to the lack of responses of spy-8 to BA. We also analyzed the cytokinin responses of another sec allele (sec-2) in the Col-0 background and found that sec-2 displayed similar cytokinin response phenotypes as sec-3 (Figure 7, D and E). Taken together, although TCP14 protein was stabilized by sec mutation, we did not observe enhanced cytokinin responses in the sec mutants.

Figure 7.

TCP14 protein stability was reduced in spy and increased in sec. A, Immunoblots containing protein extracts from 7d-old PUBQ10:FLAG-TCP14 transgenic lines in WT (Ler), spy-8 or sec-3 background were probed with the anti-tubulin or anti-FLAG antibody as labeled. Short, short exposure. Long, long exposure. FLAG-TCP14 protein level in WT was set as 1. Representative images of three biological repeats are shown. B, RT-qPCR analysis shows that relative TCP14 mRNA levels remain similar in WT, spy-8 and sec-3. PP2A mRNA levels were used to normalize samples. Data are means ± SEs of three independent biological samples and two technical repeats each. No significant difference by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's HSD test (SPSS Statistics): P values are 0.776 (WT vs spy), 0.07 (WT vs sec) and 0.227 (spy vs sec). C–E, The spy mutants displayed reduced cytokinin responses, whereas the sec mutants were similar to WT. Photos of representative fifth rosette leaves (in C and D) and stage-10 flower buds (in E) were taken, following the treatment of plants with different concentrations of BA for four weeks. In C and D, Bar = 10 mm. n = 15. In E, Bar = 0.5 mm. n = 15.

Discussion

This proteomic study has identified 20 O-Fuc proteins from Arabidopsis, and 68 from N. benthamiana (with transiently expressed AtSPY). Although our Arabidopsis dataset only represents a fraction of the total O-Fuc proteome, it clearly implicated the roles of SPY in several cellular functions in the nucleus, including transcription (TCPs, IDDs, PHR1, TAF12), RNA splicing (SUA), DNA repair (APE2), and nucleocytoplasmic transport (NUPs) (Table 1). In addition, O-fucosylation was identified in cytoplasmic proteins involved in microtubule-mediated cell division and cell growth (NEDD1 and CLASP), and protein folding (PapD). The N. benthamiana data set includes most of the homologs that were identified as SPY targets in Arabidopsis, as well as many additional new putative SPY targets. Similar to the Arabidopsis O-Fuc proteome, the majority of the potential SPY targets in the N. benthamiana data set are also nuclear proteins with predicted functions in transcription regulation or RNA processing/remodeling (Supplemental Table 4). Our results point to the putative roles of protein O-fucosylation by SPY in modulating many essential nuclear and cytoplasmic functions in plants. These results also support that the transient expression of AtSPY in this heterologous system is valid for identifying potential AtSPY targets. We further demonstrated that the transient co-expression system in N. benthamiana provides a robust platform for assaying POFUT and OGT activities on potential protein substrates. Similar approaches could be applied to the identification of protein substrates of other novel enzymes.

This study also revealed that SPY and SEC share many common protein substrates, indicating that interplay between O-GlcNAc and O-Fuc modifications occurs in diverse cellular functions (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 4), which is consistent with the observed genetic interactions between spy and sec in a number of developmental processes (Olszewski et al., 2010; Sun, 2021). Our previous study showed that the O-Fuc and O-GlcNAc sites in RGA are clustered in nearby Ser/Thr sequences, and that AtSPY and AtSEC compete with each other in reciprocal modifications of RGA when transiently co-expressed in N. benthamina (Zentella et al., 2016, 2017). In the O-Fuc and O-GlcNAc proteomic studies (this work and Xu et al., 2017), six additional Arabidopsis proteins are modified by both SPY and SEC (Table 1 and Supplemental Figure 3). Three of them (NUP214, TCP14, and NEDD1) contain O-Fuc and O-GlcNAc sites that are located in adjacent peptides. Whether the nearby O-Fuc and O-GlcNAc modifications may have antagonistic or additive effects on reciprocal modification will require further studies.

Among the common targets of SPY and SEC, we have examined the effects of O-Fuc and O-GlcNAc modifications on TCP14 in planta. Previous genetic studies showed that TCP14 and TCP15 interact with AtSPY in regulating cytokinin responses (Steiner et al., 2012). The spy mutant displays reduced cytokinin responses (e.g. reduction in leaf serration and trichomes on sepals), which resemble the phenotypes of the tcp14 tcp15 double mutant. In addition, a hypomorphic spy mutation rescues the GFP-TCP14 overexpression phenotypes and causes a reduction in the GFP-TCP14 protein levels compared to that in WT, suggesting that AtSPY promotes TCP14 stability (Steiner et al., 2016). However, TCP14 was only shown to be O-GlcNAcylated by SEC, and the effect of this modification was unknown. Our study shows that both TCP14 and TCP15 were O-fucosylated by SPY in planta. Importantly, TCP14 protein levels were reduced by the spy mutation but were elevated by the sec mutation in planta. These results support that SPY and SEC oppositely regulate TCP14 stability. The opposing effects of SPY and SEC on TCP14 are similar to RGA (an AtDELLA) and ACINUS, although protein–protein interactions were affected in the case of RGA, and the regulatory mechanism for ACINUS activity was unclear. As the genetic interactions between SPY and SEC are complex and can be either antagonistic or additive depending on the developmental processes, it will be important to explore the molecular functions of SPY and SEC in regulating key targets in different cellular pathways.

Sequences of SPY-Like genes are conserved in all plants, suggesting that protein O-fucosylation plays an important role across the plant kingdom. Similar to the reported roles of SPY in Arabidopsis, the alteration of SPY function in petunia also affects seed germination, stem growth, and flower development (Izhaki et al., 2001). Furthermore, reduced SPY activity in rice leads to taller stem and larger panicle size, but fewer panicles (Yano et al., 2019). Our proteomic study laid a foundation to further our understanding of the role of protein O-fucosylation in regulating transcription reprogramming and other intracellular processes during plant development. This study will have broader implications as SPY-Like genes are also present in algae, protists, and bacteria. Recent genetic and biochemical studies in Toxoplasma gondii (a parasitic protist) show that TgSPY also encodes a POFUT, which promotes the accumulation of its target proteins and T. gondii proliferation in vitro and in mice (Bandini et al., 2016, 2021). Therefore, nucleocytoplasmic protein O-fucosylation by SPY orthologs is a conserved regulatory mechanism for controlling a plethora of cellular processes in diverse organisms.

Materials and methods

Plant materials, plant growth conditions, and plant transformation

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) mutants spy-3 (in the Col-0 background), and spy-8, spy-19, and sec-3 in the Ler background have been previously described (Jacobsen and Olszewski, 1993; Silverstone et al., 2007; Zentella et al., 2016, 2017). Mutant cgl1-2 was obtained from the ABRC (Stock CS16366) (von Schaewen et al., 1993; Frank et al., 2008), and the fucTA fucTB xylT triple mutant and sec-2 mutant were kindly provided by Dr. Neil Olszewski (Kim et al., 2013; Hartweck et al., 2002). Unless otherwise stated, all Arabidopsis plants were grown on 0.7% agar plates (w/v) of 0.5× MS media with 1% sucrose (w/v). For mass spectrometry, Arabidopsis plants were grown in liquid media as previously described, but omitting the addition of PuGNAc (Zentella et al., 2016). Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 pMP90 was used for all plant transformations. Generation and isolation of homozygous Arabidopsis transgenic lines containing a single insertion site were performed as described (Hu et al., 2008). For agro-infiltrations, 3-week-old N. benthamiana plants grown on potting soil were used and agro-infiltration procedures were performed as described previously (Zentella et al., 2016). The cytokinin response assays were carried out as described (Greenboim-Wainberg et al., 2005), except that the plants were treated with 0, 10, or 50 μM 6-BA. Statistical analyses were performed with one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) mean separation test (SPSS Statistics).

Plasmid construction

pEarleyGate203, pEG203-SPY, pEG203-spy-19, pEG203-SEC, and pEG100-3xFR have been described (Earley et al., 2006; Zentella et al., 2016, 2017). pDONR221-IDD3, pDONR221-IDD5, and pDONR221-IDD10 were kindly provided by Drs. Ben Scheres and Ikram Blilou (Welch et al., 2007). Other plasmids used in this work were created using standard molecular techniques as summarized in Supplemental Table 5 and Supplemental Methods. Primers for plasmid construction are listed in Supplemental Table 6. All fragments generated by PCR amplification were sequenced to ensure that no mutations were introduced.

Fucosylation detection by protein blot analysis using AAL lectin

For total protein extracts, 30 µg/lane was separated by 8% SDS-PAGE. For nuclear extracts, the equivalent of 20–30 mg of initial plant material (8–12-day-old seedlings) was used. For purified protein from Nicotiana benthamiana, 50–80 ng per lane was used. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBST-500 (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20) for 2 h at room temperature (RT), followed by 1 h incubation with 0.03 µg/ml (30,000× dilution) of biotinylated-Aleuria aurantia lectin (AAL-biotin, Vector Labs, Cat. B-1395, 1 mg/ml) in TBST-500 and 3% BSA (w/v). After washing with TBST-500, the blot was incubated for 30 min at RT with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated Streptavidin (100,000× dilution, Streptavidin-HRP, Jackson Immunoresearch Labs, Cat. 016-030-084) in TBST-500 and 3% BSA. The blot was washed with TBST-500 and detected with SuperSignal Pico chemiluminescent reagent (Thermo-Fisher Scientific).

AAL-Agarose pull-down

The amounts of FLAG-RGA protein in each N. benthamiana tissue were determined by immunoblot analysis. For the pull-down assays, FLAG-RGA protein amounts in different tissues were adjusted to be the same by adding non-infiltrated leaf tissues. Two hundred and fifty milligrams of agro-infiltrated leaf tissue was homogenized in 1.5 ml of extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH7.5, 500 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100 (v/v), 2.5 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 20 µM MG-132, 1× Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich)) on ice and centrifuged at 15,000×g for 10 min at 4°C. A 20 µl of each protein extract were mixed with 30 µl of 2× Laemmli Sample Buffer (LSB) (Bio-Rad) for input analysis. To 1.5 ml of extract, 20 µl of AAL–agarose beads (Vector Labs, Cat. No. AL-1393-2, 2 mg lectin/ml) were added and incubated with rotation for 1.5 h at 4°C. The beads were washed with extraction buffer, 4× with TBST-500 and 1× with 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 and were boiled in 50 µl of 2× LSB for gel blot analysis.

Immunoblot analyses and RT-qPCR analysis

Protein blot analysis using an HRP-FLAG monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. No. A8592) was performed as described (Zentella et al., 2017). To detect O-GlcNAcylated proteins, the purified proteins were transferred to the PVDF membrane. The blocking solution consisted of TBST (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20) and 3% BSA. Detection was done with the anti-O-GlcNAc antibody CTD110.6 (5,000× dilution, Cell Signaling Technology, Cat. No. 9875) and a goat anti-Mouse IgM-HRP secondary antibody (30,000× dilution, Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. 31440). HRP activity was visualized with SuperSignal Pico or SuperSignal Dura chemiluminescent reagents on X-ray film or with an iBright Imaging System (Thermo-Fisher Scientific). RT-qPCR analysis was performed as described previously (Zentella et al., 2017) using total RNA isolated from 7-day-old seedlings of PUBQ10:FLAG-TCP14 transgenic Arabidopsis lines in WT, spy-8 and sec-3 backgrounds.

Protein extraction and tandem affinity purifications

For total protein analyses, 50–100 mg of frozen tissue was homogenized in 1.5 volumes (w/v) of 2× LSB, boiled for 5 min and centrifuged at top speed for 5 min at RT to obtain the supernatant for analysis. The FLAG-tagged proteins (containing a 6xHis-3xFLAG-tag) from agro-infiltrated N. benthamiana leaves for anti-O-GlcNAc and AAL gel blot detections were tandem affinity purified as previously described (Zentella et al., 2016, 2017), except at a smaller scale with 1 g of starting tissue. All purified proteins were quantified against a protein standard by PAGE followed by Oriole gel staining (Bio-Rad) and by anti-FLAG immunoblot analysis.

Nuclear fractionations

Small-scale nuclei isolation from Arabidopsis seedlings was carried out with extraction buffers 1, 2, and 3 of the “Chromatin immunoprecipitation” protocol described by Bowler et al. (2004), except that the starting material was 10-day-old non-crosslinked Arabidopsis seedlings. The tissue was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, ground to fine powder, and 200–500 mg transferred to a 5 ml conical tube containing 3 volumes of ice-cold Extraction Buffer 1 (w/v). After gentle mixing, the suspension was transferred to a 70 µm cell strainer (Fisher, Cat. 22363548) mounted on a 50 ml conical tube, which were then centrifuged at 800×g at 4°C for 3 min. Most of the supernatant was discarded, leaving behind ca. 700 µl to resuspend the pellet. With a wide-bore tip, the suspension was transferred to a 1.5 microfuge tube and spun at 700×g for 5 min at 4°C. The pellet was gently resuspended in 1 ml of Extraction Buffer 2, followed by centrifugation at 700×g for 5 min at 4°C. An aliquot of the soluble fraction was analyzed as the Cytoplasm + Chloroplast fraction. The nuclear pellet was resuspended in 500 µl of extraction buffer 3 and layered onto a 500 µl cushion of extraction buffer 3. After a 10 min centrifugation at 15,000×g at 4°C, the supernatant was aspirated. The purified nuclear pellet was resuspended in 50–100 µl of 2× LSB, boiled for 5 min and centrifuged at top speed at RT to collect the soluble nuclear extract for analysis.

Enrichment of O-fucosylated peptides for MS analyses

Enrichment of O-fucosylated peptides from total Arabidopsis protein extracts was performed according to Xu et al. (2012), except that the starting material was 2 g of 10-day-old cgl1-2 seedlings. The Extraction buffer Y included 0.2 mM Na3VO4 and 25 μM Deoxyfuconojirimycin (DFJ) (Enzo Life Sciences, Cat. No. BML-S108-0005) to inhibit phosphatases and fucosidases, respectively. Prior to trypsin digestion, the protein pellet was dissolved in lysis buffer (6 M Guanidine-HCl) and split into three aliquots (2 mg each). The protein sample was then incubated with 5 mM DTT for 1 h, followed by cysteine alkylation with 15 mM iodoacetamide for 1 h at RT. The sample was diluted 4-fold with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.0 (AMBIC). Trypsin (Promega, Cat. No. V5111) was added at 1:100 (w/w) and digestion carried out overnight at 37°C with gentle mixing. After peptide cleanup, according to Xu et al. (2012), the pellet was dissolved in TBS buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) and filtered through a Biomax 10 K MWCO cartridge (EMD-Millipore) to remove trypsin. The total volume was increased to 1 ml with TBS and 15 µg of AAL-biotin was added. After 4 h incubation with rotation at 4°C, 250 µg of Streptavidin-Magnetic beads (Pierce, Cat. No. 88816) was added and incubated for an additional 1 h. The beads were washed 2× with 0.5 ml of TBS, followed by 0.5 ml of AMBIC using a magnetic stand (New England BioLabs, Cat. No. S1506S). Peptides were eluted with 100 µl of AMBIC and 0.2 M methyl-α-fucopyranoside (αMeFuc) for 16 h with rotation, at 4°C. A second elution was done by incubating with 100 µl of the same elution buffer for 2 h. Both eluates were pooled and lyophilized for MS analysis.

For the N. benthamiana samples, the starting material was leaf tissue agro-infiltrated with 35S:Myc-SPY Agrobacterium strain (Zentella et al., 2016), and 1 mg of total protein was digested with trypsin at a 1:200 (w/w) ratio. Enrichments of O-fucosylated peptide after trypsin digestion were performed using the same procedure described above. For the enrichment of O-fucosylated N. benthamiana proteins prior to trypsin digestion, a modified procedure combining two published methods (Xu et al., 2012; Bandini et al., 2016) was used as described in Supplemental Methods.

To enrich for nuclear proteins, a crude nuclear enrichment procedure was followed: 4 g of finely ground cgl1-2 tissue powder was transferred to a 50 ml conical tube containing 15 ml of ice-cold Extraction Buffer 1 (w/v) (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.4 M Sucrose, 5 mM 2-mercaptoehanol, 1 mM PMSF, SigmaFast protease inhibitors, 20 µM MG-132, 10 µM PUgNAc, 10 µM DFJ). After vortexing and 2 min incubation on ice, the slurry was filtered through 70 µm cell strainers (Fisher, Cat. 22363548) by centrifugation at 800×g at 4°C for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the nuclei-enriched pellet was resuspended in 6 ml of extraction buffer Y. Phenol-based extraction, protein precipitation, digestion, and cleanup were done as described above. The only difference was that trypsin was used at a 1:50 (w/w) ratio.

Identification of O-fucosylation sites by LC–ETD and collision-activated dissociation (CAD)-tandem MS (MS/MS) analyses

Trypsin-digested proteins from Arabidopsis and Nicotiana benthamiana were separated by HPLC and analyzed on a Thermo™ Orbitrap Fusion™ Tribrid™ mass spectrometer equipped with ETD (Udeshi et al., 2008). HPLC was performed as described previously (Zentella et al., 2017). MS1 spectra were acquired in the Orbitrap with a resolution of 60,000 or 120,000, followed by a data-dependent, 3-second TopN method with a neutral loss trigger. Precursors were isolated by resolving quadrupole with a 3 m/z window. CAD MS2 spectra were collected in the Orbitrap with a resolution of 15,000. A neutral loss trigger selected precursors exhibiting the characteristic loss of one to three fucose units in the Orbitrap CAD MS2 spectra for additional fragmentation events. An HCD MS2 (25% NCE) was collected in the Orbitrap with a resolution of 15,000. CAD MS2, CAD MS3, and ETD MS2 spectra were acquired in the ion trap at a normal scan rate. Calibrated reaction times were used for ETD events. Dynamic exclusion was enabled with a repeat count of 2 and an exclusion duration of 6 s.

Peptides enriched from the Arabidopsis nuclear fraction were cleaned up using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) prior to a second MS analysis. The HILIC cleanup procedure was developed by Keira Mahoney (unpublished data). PolyHydroxyethyl A™ (PHEA) bulk material in 100 mM ammonium formate (pH 3) was pipetted onto a glass filter membrane fitted into a 250 µl pipette tip and packed to a bed length of ∼5 mm using a centrifuge. The bed was rinsed with water, followed by 10 mM ammonium formate in 90% acetonitrile, pH 3 (“loading buffer”). Peptides were dried down and resuspended in the loading buffer. Pierce® Retention Time Calibration Mixture was added to the sample. The sample was pipetted onto the packed bed, rinsed with loading buffer, and eluted with 0.1% acetic acid, 50% acetonitrile followed by 0.2% formic acid. The flowthrough and elution fractions were analyzed by MS immediately or stored at −35°C.

Data files were searched using Byonic version 3.8.13 (Protein Metrics) (Bern et al., 2012). Data files resulting from the analysis of Arabidopsis samples were searched against the UniprotKB/Swiss-Prot protein sequence database for Arabidopsis thaliana (UniProt, 2021). Data files produced from N. benthamiana samples were searched against the NbDE proteome database (Kourelis et al., 2019). Search parameters included specific cleavage C-terminal to R, K, W, F, and Y residues with up to five allowed missed cleavages, 10 ppm tolerance for precursor mass, 15 ppm mass tolerance for high-resolution MS2s, and 0.35 Da mass tolerance for low-resolution MS2s. Cleavage after W, F, or Y residues was included because peptides with these unusual ends were observed in the samples, likely caused by endogenous proteinases. Variable modifications selected included oxidation of Met residues, phosphorylation of Ser, Thr, and Tyr residues, alkylation of Cys residues, and O-GlcNAcylation, O-Fucosylation, and O-Hexosylation of Ser and Thr residues. No protein false discovery rate cutoff or score cutoff was applied prior to the output of search results. Peptides were validated by manual inspection of MS2 spectra. Modification sites were determined manually based on ETD spectra.

Consensus logo

The web-based program WebLogo 3.7.12 (http://weblogo.threeplusone.com/; Crooks et al., 2004) was used to create the amino acid logo, using the 37 mapped O-fucosylated sites from Arabidopsis and Nicotiana benthamiana peptides.

Accession numbers

Sequence information for proteins and genes included in this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers NUP1 (AT3G10650), NUP58 (AT4G37130), NUP62 (AT2G45000), NUP98A (AT1G10390), NUP214 (AT1G55540), TCP8 (AT1G58100), TCP9 (AT2G45680), TCP14 (AT3G47620), TCP15 (AT1G69690), TCP21 (AT5G08330), IDD1 (AT5G66730), IDD3 (MAGPIE, AT1G03840), IDD4 (AT2G02080), IDD5 (RAVEN, AT2G02070), IDD10 (JACKDAW, AT5G03150), PHR1 (AT4G28610), TAF12 (AT3G10070), SUA (AT3G54230), PHD (AT4G11790), APE2 (AT4G36050), NEDD1 (AT5G05970), CLASP (AT2G20190), PapD-like (AT4G05060), bHLH130 (FBH4, At2G42280), WRKY31 (At4G22070), C3H58 (At5G18550).2

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

A special thank you to Protein Metrics for providing Byonic.

Contributor Information

Rodolfo Zentella, Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708, USA.

Yan Wang, Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708, USA.

Emily Zahn, Department of Chemistry, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia 22904, USA.

Jianhong Hu, Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708, USA.

Liang Jiang, Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708, USA.

Jeffrey Shabanowitz, Department of Chemistry, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia 22904, USA.

Donald F Hunt, Department of Chemistry, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia 22904, USA; Department of Pathology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia 22903, USA.

Tai-ping Sun, Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708, USA.

Supplemental data

Supplemental Methods

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1 . Comparison of O-fucosylated Arabidopsis proteins in cytoplasmic/chloroplast fraction vs. nuclear fraction by AAL blot analysis.

Supplemental Figure S2 . Pull-down of O-fucosylated proteins from nuclear extracts of WT Arabidopsis and mutants.

Supplemental Figure S3 . Schematic of Arabidopsis proteins that are SPY and SEC targets.

Supplemental Figure S4 . AAL-biotin and anti-O-GlcNAc antibody specifically recognized O-fucosylated and O-GlcNAcylated proteins, respectively.

Supplemental Table S1 . O-fucosylated Arabidopsis peptides identified by ETD–MS/MS.

Supplemental Table S2 . O-fucosylation sites in Arabidopsis and N. benthamiana proteins.

Supplemental Table S3 . O-fucosylated N. benthamiana peptides identified by ETD–MS/MS.

Supplemental Table S4 . O-fucosylated N. benthamiana proteins identified by ETD–MS/MS.

Supplemental Table S5 . List of Constructs.

Supplemental Table S6 . List of Primers.

Supplemental Dataset S1 . ETD MS2 spectrum of the tryptic NUP1 peptide FGQPAAPFsO-FucAPAVSESO-FucSGQISK from Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Dataset S2 . ETD MS2 spectrum of the tryptic TCP8 peptide LLQQAEPAIVAATGTGtO-FucIPANFsO-FucTLSVSLR from Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Dataset S3 . ETD MS2 spectrum of the tryptic IDD4 peptide EENLNAGsO-FucNVSAtO-FucALLQK purified from Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Dataset S4 . ETD MS2 spectrum of the tryptic IDD5 peptide IS(SGS)O-FucVPSLFSSSMQSPNSAPHMSAtO-FucALLQK from Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Dataset S5 . ETD MS2 spectrum of the tryptic PHR1 peptide HLLSSsO-FucNGGAVGHIC(SSSSS)O-FucGFATNLHYSTMVSHEK from Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Dataset S6 . ETD MS2 spectrum of the tryptic TAF12 peptide THFSSAsO-FucSPLLSSSsO-FucAPASSSSSLPISGQQR from Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Dataset S7 . ETD MS2 spectrum of the tryptic WRKY33a peptide TTGVKSEVAPIQSFsO-FucQEK purified from N. benthamiana that was transiently expressed with AtSPY.

Supplemental Dataset S8 . ETD MS2 spectrum of the tryptic C3H58-like-b peptide GGHASHSGVQQSEQSSNPSSGsO-FucsO-FucSSSADHRGEAR from N. benthamiana that was transiently expressed with AtSPY.

Supplemental Dataset S9 . ETD MS2 spectrum of the tryptic VIP2-like peptide FASNNIPVALSQISQG(SS)O-FucHGH(SS)O-FucMTSR from N. benthamiana that was transiently expressed with AtSPY.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM100051 to T.-pS., and GM037537 to D.F.H.) and the National Science Foundation (MCB-1818161 to T.-pS.).

Data availability

Supporting data for this study are available within the paper and in the Supplemental Data.

References

- Ambrose JC, Shoji T, Kotzer AM, Pighin JA, Wasteneys GO (2007) The Arabidopsis CLASP gene encodes a microtubule-associated protein involved in cell expansion and division. Plant Cell 19(9): 2763–2775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amedeo P, Habu Y, Afsar K, Mittelsten Scheid O, Paszkowski J (2000) Disruption of the plant gene MOM releases transcriptional silencing of methylated genes. Nature 405(6783): 203–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai MY, Shang JX, Oh E, Fan M, Bai Y, Zentella R, Sun T-P, Wang Z-Y (2012) Brassinosteroid, gibberellin, and phytochrome signalling pathways impinge on a common transcription module in Arabidopsis. Nat Cell Biol 14(8): 810–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey PC, Martin C, Toledo-Ortiz G, Quail PH, Huq E, Heim MA, Jakoby M, Werber M, Weisshaar B (2003) Update on the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 15(11): 2497–2502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandini G, Agop-Nersesian C, van der Wel H, Mandalasi M, Kim HW, West CM, Samuelson J (2021) The nucleocytosolic O-fucosyltransferase Spindly affects protein expression and virulence in Toxoplasma gondii. J Biol Chem 296(Jan–Jun): 100039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandini G, Haserick JR, Motari E, Ouologuem DT, Lourido S, Roos DS, Costello CE, Robbins PW, Samuelson J (2016) O-fucosylated glycoproteins form assemblies in close proximity to the nuclear pore complexes of Toxoplasma gondii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113(41): 11567–11572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bern M, Kil YJ, Becker C (2012) Byonic: advanced peptide and protein identification software. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 40: 13.20.1–13.20.14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi Y, Deng Z, Ni W, Shrestha R, Savage D, Hartwig T, Patil S, Hong SH, Zhang Z, Oses-Prieto JA, et al. (2021) Arabidopsis ACINUS is O-glycosylated and regulates transcription and alternative splicing of regulators of reproductive transitions. Nat Commun 12(1): 945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond MR, Hanover JA (2015) A little sugar goes a long way: the cell biology of O-GlcNAc. J Cell Biol 208(7): 869–880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler C, Benvenuto G, Laflamme P, Molino D, Probst AV, Tariq M, Paszkowski J (2004) Chromatin techniques for plant cells. Plant J 39(5): 776–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustos R, Castrillo G, Linhares F, Puga MI, Rubio V, Perez-Perez J, Solano R, Leyva A, Paz-Ares J (2010) A central regulatory system largely controls transcriptional activation and repression responses to phosphate starvation in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet 6(9): e1001102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colasanti J, Tremblay R, Wong AY, Coneva V, Kozaki A, Mable BK (2006) The maize INDETERMINATE1 flowering time regulator defines a highly conserved zinc finger protein family in higher plants. BMC Genomics 7(1): 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE (2004) Weblogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res 14(6): 1188–1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H, Benfey PN (2009) Interplay between SCARECROW, GA and LIKE HETEROCHROMATIN PROTEIN 1 in ground tissue patterning in the Arabidopsis root. Plant J 58(6): 1016–1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danisman S (2016) TCP transcription factors at the interface between environmental challenges and the plant's growth responses. Front Plant Sci 7: 1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daviere JM, Achard P (2016) A pivotal role of DELLAs in regulating multiple hormone signals. Mol Plant 9(1): 10–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lucas M, Daviere JM, Rodriguez-Falcon M, Pontin M, Iglesias-Pedraz JM, Lorrain S, Fankhauser C, Blazquez MA, Titarenko E, Prat S (2008) A molecular framework for light and gibberellin control of cell elongation. Nature 451(7177): 480–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Z, Millar AJ, Davis AM, Davis SJ (2007) TIME FOR COFFEE encodes a nuclear regulator in the Arabidopsis thaliana circadian clock. Plant Cell 19(5): 1522–1536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley KW, Haag JR, Pontes O, Opper K, Juehne T, Song KM, Pikaard CS (2006) Gateway-compatible vectors for plant functional genomics and proteomics. Plant J 45(4): 616–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eulgem T, Rushton PJ, Robatzek S, Somssich IE (2000) The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci 5(5): 199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S, Martinez C, Gusmaroli G, Wang Y, Zhou J, Wang F, Chen L, Yu L, Iglesias-Pedraz JM, Kircher S, et al. (2008) Coordinated regulation of Arabidopsis thaliana development by light and gibberellins. Nature 451(7177): 475–479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francischini CW, Quaggio RB (2009) Molecular characterization of Arabidopsis thaliana PUF proteins–binding specificity and target candidates. FEBS J 276(19): 5456–5470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank J, Kaulfurst-Soboll H, Rips S, Koiwa H, von Schaewen A (2008) Comparative analyses of Arabidopsis complex glycan1 mutants and genetic interaction with staurosporin and temperature sensitive3a. Plant Physiol 148(3): 1354–1367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank A, Matiolli CC, Viana AJC, Hearn TJ, Kusakina J, Belbin FE, Wells Newman D, Yochikawa A, Cano-Ramirez DL, Chembath A, et al. (2018) Circadian entrainment in Arabidopsis by the sugar-responsive transcription factor bZIP63. Curr Biol 28(16): 2597–2606.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujihashi M, Peapus DH, Kamiya N, Nagata Y, Miki K (2003) Crystal structure of fucose-specific lectin from Aleuria aurantia binding ligands at three of its five sugar recognition sites. Biochemistry 42(38): 11093–11099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumori F, Takeuchi N, Hagiwara T, Ohbayashi H, Endo T, Kochibe N, Nagata Y, Kobata A (1990) Primary structure of a fucose-specific lectin obtained from a mushroom, Aleuria aurantia. J Biochem 107(2): 190–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenboim-Wainberg Y, Maymon I, Borochov R, Alvarez J, Olszewski N, Ori N, Eshed Y, Weiss D (2005) Cross talk between gibberellin and cytokinin: the Arabidopsis GA response inhibitor SPINDLY plays a positive role in cytokinin signaling. Plant Cell 17(1): 92–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart GW (2019) Nutrient regulation of signaling and transcription. J Biol Chem 294(7): 2211–2231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart GW, Slawson C, Ramirez-Correa G, Lagerlof O (2011) Cross talk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: roles in signaling, transcription, and chronic disease. Annu Rev Biochem 80(1): 825–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartweck LM, Genger RK, Grey WM, Olszewski NE (2006) SECRET AGENT and SPINDLY have overlapping roles in the development of Arabidopsis thaliana L. Heyn. J Exp Bot 57(4): 865–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartweck LM, Scott CL, Olszewski NE (2002) Two O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase genes of Arabidopsis thaliana L. Heynh. have overlapping functions necessary for gamete and seed development. Genetics 161(3): 1279–1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holdener BC, Haltiwanger RS (2019) Protein O-fucosylation: structure and function. Curr Opin Struct Biol 56(Jun): 78–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Mitchum MG, Barnaby N, Ayele BT, Ogawa M, Nam E, Lai W-C, Hanada A, Alonso JM, Ecker JR, et al. (2008) Potential sites of bioactive gibberellin production during reproductive growth in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20(2): 320–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izhaki A, Swain SM, Tseng T-S, Borochov A, Olszewski NE, Weiss D (2001) The role of SPY and its TPR domain in the regulation of gibberellin action throughout the life cycle of Petunia hybrida plants. Plant J 28(2): 181–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen SE, Binkowski KA, Olszewski NE (1996) SPINDLY, a tetratricopeptide repeat protein involved in gibberellin signal transduction in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93(17): 9292–9296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen SE, Olszewski NE (1993) Mutations at the SPINDLY locus of Arabidopsis alter gibberellin signal transduction. Plant Cell 5(8): 887–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer M, Master V, Waites R, Davies B (2011) TCP14 and TCP15 affect internode length and leaf shape in Arabidopsis. Plant J 68(1): 147–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YC, Jahren N, Stone MD, Udeshi ND, Markowski TW, Witthuhn BA, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Olszewski NE (2013) Identification and origin of N-linked β-D-N-acetylglucosamine monosaccharide modifications on Arabidopsis proteins. Plant Physiol 161(1): 455–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourelis J, Kaschani F, Grosse-Holz FM, Homma F, Kaiser M, van der Hoorn RAL (2019) A homology-guided, genome-based proteome for improved proteomics in the alloploid Nicotiana benthamiana. BMC Genomics 20(1): 722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lago C, Clerici E, Mizzi L, Colombo L, Kater MM (2004) TBP-associated factors in Arabidopsis. Gene 342(2): 231–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Han K, Pak JE, Satkunarajah M, Zhou D, Rini JM (2017) Recognition of EGF-like domains by the Notch-modifying O-fucosyltransferase POFUT1. Nat Chem Biol 13(7): 757–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Liang W, Li Y, Qian W (2018) APURINIC/APYRIMIDINIC ENDONUCLEASE2 and ZINC FINGER DNA 3′-PHOSPHOESTERASE play overlapping roles in the maintenance of epigenome and genome stability. Plant Cell 30(9): 1954–1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Tessaro MJ, Li X, Zhang Y (2010) Regulation of the expression of plant resistance gene SNC1 by a protein with a conserved BAT2 domain. Plant Physiol 153(3): 1425–1434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang L, Wang Q, Song Z, Wu Y, Liang Q, Wang Q, Yang J, Bi Y, Zhou W, Fan L-M (2021) O-fucosylation of CPN20 by SPINDLY derepresses abscisic acid signaling during seed germination and seedling development. Front Plant Sci 12: 724144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JA, Ohno C, Smith ZR, Meyerowitz EM (2006) TOPLESS regulates apical embryonic fate in Arabidopsis. Science 312(5779): 1520–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Trillo M, Cubas P (2010) TCP genes: a family snapshot ten years later. Trends Plant Sci 15(1): 31–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matiolli CC, Tomaz JP, Duarte GT, Prado FM, Del Bem LE, Silveira AB, Gauer L, Correa LG, Drumond RD, Viana AJ, et al. (2011) The Arabidopsis bZIP gene AtbZIP63 is a sensitive integrator of transient abscisic acid and glucose signals. Plant Physiol 157(2): 692–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maymon I, Greenboim-Wainberg Y, Sagiv S, Kieber JJ, Moshelion M, Olszewski N, Weiss D (2009) Cytosolic activity of SPINDLY implies the existence of a DELLA-independent gibberellin-response pathway. Plant J 58(6): 979–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Risueno MA, Sozzani R, Yardimci GG, Petricka JJ, Vernoux T, Blilou I, Alonso J, Winter CM, Ohler U, Scheres B, et al. (2015) Transcriptional control of tissue formation throughout root development. Science 350(6259): 426–430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutanwad KV, Zangl I, Lucyshyn D (2020) The Arabidopsis O-fucosyltransferase SPINDLY regulates root hair patterning independently of gibberellin signaling. Development 147(19): dev192039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Otta Y, Ando A, Nagata Y (2001) A lectin from an ascomycete mushroom, Melastiza chateri: no synthesis of the lectin in mycelial isolate. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 65(3): 686–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski NE, West CM, Sassi SO, Hartweck LM (2010) O-GlcNAc protein modification in plants: evolution and function. Biochim Biophys Acta 1800(2): 49–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin F, Kodaira KS, Maruyama K, Mizoi J, Tran LS, Fujita Y, Morimoto K, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K (2011) SPINDLY, a negative regulator of gibberellic acid signaling, is involved in the plant abiotic stress response. Plant Physiol 157(4): 1900–1913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raices M, D'Angelo MA (2012) Nuclear pore complex composition: a new regulator of tissue-specific and developmental functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13(11): 687–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio V, Linhares F, Solano R, Martin AC, Iglesias J, Leyva A, Paz-Ares J (2001) A conserved MYB transcription factor involved in phosphate starvation signaling both in vascular plants and in unicellular algae. Genes Dev 15(16): 2122–2133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffzek K, Welti S (2012) Pleckstrin homology (PH) like domains—versatile modules in protein-protein interaction platforms. FEBS Lett 586(17): 2662–2673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider TD, Stephens RM (1990) Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res 18(20): 6097–6100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone AL, Mak PYA, Casamitjana Martínez E, Sun T-P (1997) The new RGA locus encodes a negative regulator of gibberellin response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 146(3): 1087–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone AL, Tseng T-S, Swain S, Dill A, Jeong SY, Olszewski NE, Sun T-P (2007) Functional analysis of SPINDLY in gibberellin signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 143(2): 987–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner E, Efroni I, Gopalraj M, Saathoff K, Tseng TS, Kieffer M, Eshed Y, Olszewski N, Weiss D (2012) The Arabidopsis O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase SPINDLY interacts with class I TCPs to facilitate cytokinin responses in leaves and flowers. Plant Cell 24(1): 96–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner E, Livne S, Kobinson-Katz T, Tal L, Pri-Tal O, Mosquna A, Tarkowska D, Mueller B, Tarkowski P, Weiss D (2016) The putative O-linked N-acetylglucosamine transferase SPINDLY inhibits class I TCP proteolysis to promote sensitivity to cytokinin. Plant Physiol 171(2): 1485–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner E, Triana MR, Kubasi S, Blum S, Paz-Ares J, Rubio V, Weiss D (2021) KISS ME DEADLY F-box proteins modulate cytokinin responses by targeting the transcription factor TCP14 for degradation. Plant Physiol 185(4): 1495–1499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser R (2016) Plant protein glycosylation. Glycobiology 26(9): 926–939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser R, Altmann F, Mach L, Glossl J, Steinkellner H (2004) Generation of Arabidopsis thaliana plants with complex N-glycans lacking beta1,2-linked xylose and core alpha1,3-linked fucose. FEBS Lett 561(1–3): 132–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugliani M, Brambilla V, Clerkx EJ, Koornneef M, Soppe WJ (2010) The conserved splicing factor SUA controls alternative splicing of the developmental regulator ABI3 in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 22(6): 1936–1946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun TP (2011) The molecular mechanism and evolution of the GA-GID1-DELLA signaling module in plants. Curr Biol 21(9): R338–R345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun TP (2021) Novel nucleocytoplasmic protein O-fucosylation by SPINDLY regulates diverse developmental processes in plants. Curr Opin Struct Biol 68(Jun): 113–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain SM, Tseng T-S, Thornton TM, Gopalraj M, Olszewski N (2002) SPINDLY is a nuclear-localized repressor of gibberellin signal transduction expressed throughout the plant. Plant Physiol 129(2): 605–615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Fukao Y, Hatsugai N, Katagiri F, Hara-Nishimura I (2017) Nup82 functions redundantly with Nup136 in a salicylic acid-dependent defense response of Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleus 8(3): 301–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Fukao Y, Iwamoto M, Haraguchi T, Hara-Nishimura I (2010) Identification and characterization of nuclear pore complex components in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 22(12): 4084–4097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toleman CA, Schumacher MA, Yu SH, Zeng W, Cox NJ, Smith TJ, Soderblom EJ, Wands AM, Kohler JJ, Boyce M (2018) Structural basis of O-GlcNAc recognition by mammalian 14-3-3 proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115(23): 5956–5961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng TS, Salome PA, McClung CR, Olszewski NE (2004) SPINDLY and GIGANTEA interact and act in Arabidopsis thaliana pathways involved in light responses, flowering, and rhythms in cotyledon movements. Plant Cell 16(6): 1550–1563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udeshi ND, Compton PD, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Rose KL (2008) Methods for analyzing peptides and proteins on a chromatographic timescale by electron-transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc 3(11): 1709–1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UniProt C (2021) Uniprot: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res 49(D1): D480–D489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valero-Gonzalez J, Leonhard-Melief C, Lira-Navarrete E, Jimenez-Oses G, Hernandez-Ruiz C, Pallares MC, Yruela I, Vasudevan D, Lostao A, Corzana F, et al. (2016) A proactive role of water molecules in acceptor recognition by protein O-fucosyltransferase 2. Nat Chem Biol 12(4): 240–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernoud V, Horton AC, Yang Z, Nielsen E (2003) Analysis of the small GTPase gene superfamily of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 131(3): 1191–1208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetsch M, Puorger C, Spirig T, Grauschopf U, Weber-Ban EU, Glockshuber R (2004) Pilus chaperones represent a new type of protein-folding catalyst. Nature 431(7006): 329–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz R, Kim SK, Mi J, Rawat AA, Veluchamy A, Mariappan KG, Rayapuram N, Daviere JM, Achard P, Blilou I, et al. (2019) INDETERMINATE-DOMAIN 4 (IDD4) coordinates immune responses with plant-growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Pathog 15(1): e1007499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Schaewen A, Sturm A, O'Neill J, Chrispeels MJ (1993) Isolation of a mutant Arabidopsis plant that lacks N-acetyl glucosaminyl transferase I and is unable to synthesize Golgi-modified complex N-linked glycans. Plant Physiol 102(4): 1109–1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Guo Y, Wu C, Yang G, Li Y, Zheng C (2008) Genome-wide analysis of CCCH zinc finger family in Arabidopsis and rice. BMC Genomics 9(1): 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, He Y, Su C, Zentella R, Sun TP, Wang L (2020) Nuclear localized O-fucosyltransferase SPY facilitates PRR5 proteolysis to fine-tune the pace of Arabidopsis circadian clock. Mol Plant 13(3): 446–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Song X, Gu L, Li X, Cao S, Chu C, Cui X, Chen X, Cao X (2013) NOT2 Proteins promote polymerase II-dependent transcription and interact with multiple MicroRNA biogenesis factors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25(2): 715–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch D, Hassan H, Blilou I, Immink R, Heidstra R, Scheres B (2007) Arabidopsis JACKDAW and MAGPIE zinc finger proteins delimit asymmetric cell division and stabilize tissue boundaries by restricting SHORT-ROOT action. Genes Dev 21(17): 2196–2204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing L, Liu Y, Xu S, Xiao J, Wang B, Deng H, Lu Z, Xu Y, Chong K (2018) Arabidopsis O-GlcNAc transferase SEC activates histone methyltransferase ATX1 to regulate flowering. EMBO J 37(19):e98115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu SL, Chalkley RJ, Maynard JC, Wang W, Ni W, Jiang X, Shin K, Cheng L, Savage D, Huhmer AF, et al. (2017) Proteomic analysis reveals O-GlcNAc modification on proteins with key regulatory functions in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114(8): E1536–E1543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu SL, Chalkley RJ, Wang ZY, Burlingame AL (2012) Identification of O-linked beta-D-N-acetylglucosamine-modified proteins from Arabidopsis. Methods Mol Biol 876: 33–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S, Xiao J, Yin F, Guo X, Xing L, Xu Y, Chong K (2019) The protein modifications of O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation mediate vernalization response for flowering in winter wheat. Plant Physiol 180(3): 1436–1449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Yang JY, Niu QW, Chua NH (2006) Arabidopsis DCP2, DCP1, and VARICOSE form a decapping complex required for postembryonic development. Plant Cell 18(12): 3386–3398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano K, Morinaka Y, Wang F, Huang P, Takehara S, Hirai T, Ito A, Koketsu E, Kawamura M, Kotake K, et al. (2019) GWAS With principal component analysis identifies a gene comprehensively controlling rice architecture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116(42): 21262–21267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H, Hirano K, Sato T, Mitsuda N, Nomoto M, Maeo K, Koketsu E, Mitani R, Kawamura M, Ishiguro S, et al. (2014) DELLA protein functions as a transcriptional activator through the DNA binding of the INDETERMINATE DOMAIN family proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111(21): 7861–7866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng CJ, Lee YR, Liu B (2009) The WD40 repeat protein NEDD1 functions in microtubule organization during cell division in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell 21(4): 1129–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]