Abstract

A liposomal form of dexamethasone was obtained. Liposomal vesicles were formed. The efficiency of incorporating dexamethasone into the liposomes was 99.7%. The cytotoxicity of the obtained liposomes was studied on a culture of human lung fibroblast cells using the MTT assay. The toxicity of liposomal dexamethasone was less than that of dexamethasone solution after a 24-h incubation. The half-maximum inhibitory concentration (IC50) was not achieved after 24 h when exposed to liposomal dexamethasone whereas IC50 was 27.5 mg/mL for lecithin (empty liposomes) and 177 µg/mL for dexamethasone solution. The toxicity of liposomal dexamethasone increased much more than that of dexamethasone solution after 48 h of incubation with IC50 values of 36 and 156 µg/mL, respectively. Thus, the liposomal form of dexamethasone has a latent period for implementation of the cytostatic (antiproliferative) action. Experiments on laboratory white rats of both sexes revealed that the inhalation use of liposomal dexamethasone insignificantly changed the functional parameters of their respiratory and cardiovascular systems. The study results could be used for conducting clinical trials.

Keywords: dexamethasone, liposomes, safety of dexamethasone, inhalation use of dexamethasone, human lung fibroblasts, rats

Liposomal drugs are being scrutinized as promising agents for treating acute lung damage [1] and other respiratory diseases [2]. Drug delivery to the lungs using inhalation liposomes is especially critical for reducing local and systemic side effects [3]. The use of inhalation liposomes can be justified because the lipid shell consisting of phosphatidylcholine has surfactant-like properties [4] and can increase the diffusion rate of gases through the alveolar-capillary membrane [5]. The use of inhalation nanomaterials does require safety studies [6]. Thus, it is important to know not only the influence on the holistic organism of drugs encapsulated in liposomes but also the degree of toxicity directly on lung tissue cells.

Glucocorticosteroids are recognized efficacious agents for pathogenetic therapy of various types of pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [7]. Dexamethasone has been highly regarded around the world for the new COVID-19 coronavirus infection [8] as an agent for battling intoxication, inflammation, and sclerotic changes in the lungs [9]. A liposomal form of dexamethasone that was studied for intravenous administration in models of lung pathology is certainly interesting [10, 11]. However, scientific research on inhalation liposomal glucocorticosteroids is exceedingly rare [12]. The questions of the safety and toxicity of an inhalation liposomal dosage form remain open.

The goal of the present work was to establish the degree of safety of a liposomal form of dexamethasone for human lung fibroblasts and to evaluate the effect of liposomes with dexamethasone on the functional parameters of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems of rats upon their inhalation use.

EXPERIMENTAL PART

Preparation of liposomes with dexamethasone

The following chemical substances and reagents were used in the work: dexamethasone substance (Sigma Aldrich, USA); lecithin (phosphatidylcholine) EPCS 10 8018-1/130 (Lipoid, Germany); cholesterol (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc., USA); CHCl3, stabilized (chemically pure, Khimmed, Russia); deionized purified H2O, PM 42-2619-98; NaOH, NaCl (OOO Ekonomkemikal, Russia).

The following laboratory equipment was used: Heidolph Laborota eco rotary evaporator (Germany); LIPEXTM extruder (Northern Lipids Inc., Canada); NANO-flex nanoparticle size analyzer (Microtrac Inc., USA); UV-2600 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Inc., Japan); model 8200 ultrafiltration cell (Amicon, USA); MF-1210-76 dialysis bag with pore size 12-14 kDa and MF-CB-10100 clamp for dialysis bag (MFPI, USA); C-MAG HS 7 magnetic stirrer with heater (IKA, Germany).

Method for preparing liposomes with dexamethasone.

Liposomes were prepared by passive loading. Weighed portions of lecithin (300 mg), cholesterol (20 mg), and dexamethasone (15 mg) were placed into a 1-L round-bottomed flask. Then, CHCl3 was added to dissolve completely the solids. The organic solvent was removed under vacuum at 50ºC to form a lipid film in the flask and eliminate the CHCl3 odor. The film was rinsed off with NaCl solution (5 mL, 0.9%) at 60 rpm and 30ºC. The resulting aqueous-lipid dispersion was passed through polycarbonate filters with pore diameters 400 and 200 nm. Liposomal vesicles were obtained at the exit from the extruder and collected in a flask.

The sizes of the liposomal vesicles were determined by dynamic light scattering using a NANO-flex nano-sizer and the Microtrac Flex 11.0.0.2 program.

The liposomal dispersion was purified of dexamethasone not incorporated into the liposomes by ultrafiltration for 24 h under an N2 atmosphere at 0.3 MPa pressure [13]. Liposomes (8 mL) were adjusted to 50 mL by NaCl solution (50 mL, 0.9%) for the filtration. The thick purified liposome dispersion was again adjusted to a volume of 5 mL using NaCl solution (0.9%). The filtrate exiting the cell was used to determine the dexamethasone concentration by spectrophotometry [14].

Toxicity study in vitro of liposomes with dexamethasone

The cytotoxicity of the emulsions was studied using human lung fibroblast (HLF) cell culture. Cells in the exponential growth phase were inoculated into 96-well plates at a concentration of 5·103 cells/well and incubated for 24 h under standard conditions in DMEM medium with added FBS (10%) and antibiotics (penicillin-streptomycin) at 5% CO2 and 37°C.

The cytotoxicity of liposomal dexamethasone was determined at dexamethasone concentrations in the plate wells of 1500, 750, 325, 162, 81, 40, 20, and 10 µg/mL. The toxicity of dexamethasone solution (solution for injection, KRKA, Slovenia) and empty liposomes at concentrations analogous to liposomal dexamethasone was also tested. The viability of cells was evaluated after 24 and 48 h of incubation using the MTT assay. The viability of cells in all plates was evaluated relative to a control series of wells into which the test components were not placed.

The medium was changed to a 5% solution of MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl] after the incubation period. The MTT was reduced to formazan crystals, which was evaluated using an inverted microscope (Mikromed, Russia). Then, the medium was removed. DMSO (150 µL) was added. The plates were shaken for 20 min at 37°C. The optical density was measured on a Varioskan Lux instrument (Thermo Scientific, USA) at 570 nm against a reference of 650 nm.

The optical density results were expressed in % ODsample/ODcontrol.

Experimental protocol for safety study of inhalation use of liposomal dexamethasone in laboratory animals

The study used outbred white rats of both sexes (n = 10, 5 females and 5 males). Inhalation of liposomal dexamethasone and recording of functional parameters were carried out with intravenous injection into a side tail vein of the anesthetics Rometar (8 mg/kg) and Zoletil (20 mg/kg). The experiment was conducted after approval by the local ethics committee according to rules for working with animals formulated in directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and the European Union Council for the protection of animals used for scientific purposes (Directive 2010). A B. Well WN-117 compressor inhaler (nebulizer) was used for the inhalation. Liposomal dexamethasone was inhaled 5 min before inducing general anesthesia. The inhalation used a mask adapted to the head of the rat. Physiological parameters were recorded using an MP150 system (BIOPAC Systems, Inc., USA). Parameters were recorded initially before inhalation and at 1, 4, 24, and 72 h after it. The animals were evaluated for hemoglobin saturation (SpO2); respiration rate (RR); exhale volume and exhale and inhale rate; heart rate (HR); andsystolic (SAP) and diastolic arterial pressure (DAP).

Observed differences in numerical values were evaluated using the Student t-criterion. Conclusions about the statistical significance of differences were made for significance level p < 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

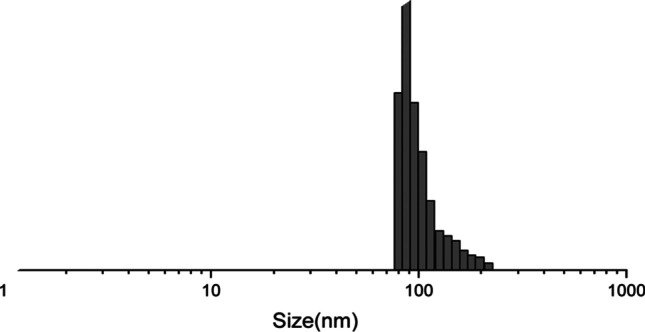

The average diameter of the liposomes with dexamethasone was 86 ± 5 nm(Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Size of obtained liposomes, nm (nano-sizer parameters).

The dexamethasone concentration in the purified liposomal dispersion was 2.93 mg/mL; dexamethasone incorporation efficiency into the liposomes, 99.7%.

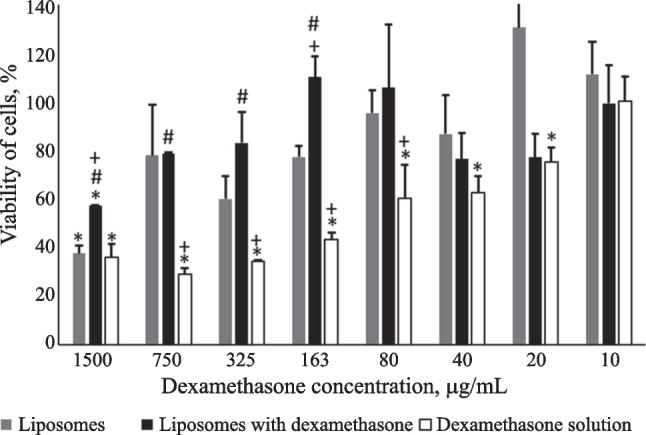

Dexamethasone in solution exhibited statistically significant high toxicity for HLF up to a concentration in the substrate of 20 µg/mL. Liposomal dexamethasone exhibited much lower toxicity than the solution. The survival of cells 24 h after injection of the liposomes with dexamethasone was comparable to the effect on the cells of empty liposomes (Fig. 2). The greatest differences in toxicity between liposomal dexamethasone and its solution occurred at concentrations 750, 325, and 163 µg/mL with significance levels p less than 0.001, 0.05, and 0.01, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Viability of HLF cells for various concentrations of dexamethasone after 24-h incubation from MTT assay data. Note: *survival of cells statistically significantly different from that without addition of tested compounds; #survival of cells with addition of liposomal dexamethasone statistically significantly different from that with addition of an equal concentration of dexamethasone in solution; +statistically significantly different survival of cells from that with addition of empty liposomes. Liposomal suspension contained the maximum and minimum lecithin concentration of 30 and 0.2 mg/mL, respectively.

The IC50 value for the effect of liposomal dexamethasone was not achieved. Empty liposomes showed the IC50 for lecithin of 27.5 mg/mL. The dexamethasone solution had an IC50 of 177 µg/mL.

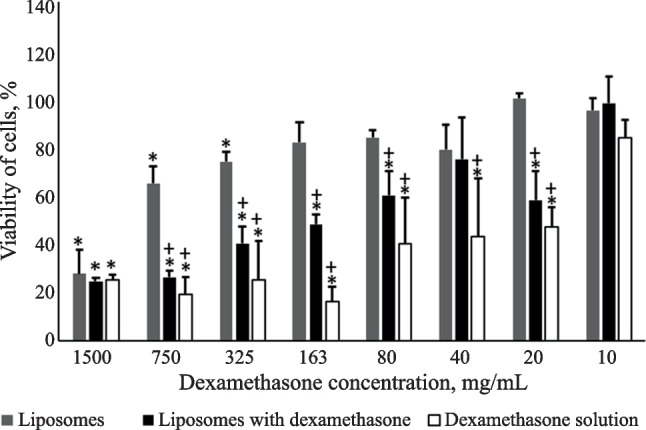

Survival of cells in medium with the added test substances decreased after incubation for 48 h as compared to that found after 24 h (Fig. 3). The viability of cells affected by dexamethasone as liposomes decreased especially strongly and did not differ from that of dexamethasone solution. Liposomal dexamethasone statistically significantly suppressed the viability of HLF at concentrations of 1500 – 20 µg/mL (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Viability of HLF cells for various concentrations of dexamethasone after 48-h incubation from MTT assay data. Note: *survival of cells statistically significantly different from that without addition of tested compounds; +statistically significantly different survival of cells from that with addition of empty liposomes. Liposomal suspension contained the maximum and minimum lecithin concentration of 30 and 0.2 mg/mL, respectively.

Cells subjected to the action of empty liposomes also had lower viability than intact cells after incubation for 48 h at lecithin concentrations of 30, 15, and 7.5 mg/mL (Fig. 3).

The IC50 for dexamethasone solution was 36 µg/mL after 48 h; for liposomal dexamethasone, 158 µg/mL. The toxic effect on the cells of lecithin of empty liposomes practically did not change after incubation for 48 h with an IC50 of 25.5 mg/mL.

All animals survived and did not show any behavioral changes after inhalation of liposomal dexamethasone. The RR, HR, and arterial pressure did not statistically significantly change for 72 h after inhalation of liposomal dexamethasone (Table 1). The air flow rate changed insignificantly and only during exhalation. The exhale rate 24 h after inhalation increased relative to the initial by 18% and decreased by 44% after 72 h. Also, the smallest exhale volume and greatest RR of the whole observation period were observed after 72 h (Table 1). The inhale rate did not change over the whole observation period.

TABLE 1.

Functional Parameters in Rats Before and After Inhalation of Liposomal Dexamethasone

| Parameter | Control points for recording parameters | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | 1 h | 4 h | 24 h | 72 h | |

| SpO2, % | 83 ± 1 | 91 ± 1* | 86 ± 2 | 87 ± 2* | 86 ± 2 |

| pO2, mm Hg | 51 ± 1 | 67 ± 3* | 57 ± 3 | 61 ± 3* | 55 ± 3 |

| RR, min–1 | 78 ± 7 | 82 ± 8 | 81 ± 5 | 89 ± 3 | 94 ± 4 |

| Vex, mL/s | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.2* | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1* |

| Inhale rate, mL/s | 10.0 ± 1.3 | 9.4 ± 0.9 | 11.2 ± 1.4 | 10.5 ± 0.5 | 8.5 ± 1.5 |

| Exhale rate, mL/s | 6.6 ± 0.6 | 5.7 ± 0.7 | 5.5 ± 0.8 | 7.8 ± 0.6* | 3.7 ± 0.6* |

| HR (min(1) | 223 ± 15 | 252 ± 20 | 317 ± 31* | 253 ± 24 | 251 ± 10 |

| SAP, mm Hg | 113 ± 7 | 96 ± 14 | 121 ± 16 | 116 ± 12 | 101 ± 18 |

| DAP, mm Hg | 74 ± 9 | 72 ± 7 | 86 ± 9 | 71 ± 8 | 58 ± 13 |

*parameter statistically significantly different from analogous one in initial stage (within group).

Hemoglobin oxygenation and saturation changed insignificantly 1 and 24 h after inhalation of liposomes and tended to increase.

Liposomal dexamethasone showed extremely low toxicity for HLF. Considering that glucocorticosteroids themselves possess antiproliferation action, the results indicated that this effect was neutralized because of the liposome shell. Liposomal dexamethasone had delayed action on the cells, in contrast to dexamethasone solution. Liposomal dexamethasone was nontoxic for cells after a 24-h incubation and even less toxic than empty liposomes although its toxicity increased after 48 h and was comparable to that of dexamethasone solution during the first days of incubation. The delayed in vitro toxic effect may have been caused by slow release of dexamethasone from the liposomes or slower intracellular diffusion of the liposomes with dexamethasone.

An in vivo study showed that inhalation use of liposomal dexamethasone caused little change in the functional parameters of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems in rats. Several significant changes of the respiratory parameters could be attributed to the effects of general anesthesia.

Thus, the liposomal form of dexamethasone was less toxic for HLF than dexamethasone solution and had a latent period for exhibiting a cytostatic (antiproliferative) effect. It was safe for inhalation use in laboratory animals.

Footnotes

Translated from Khimiko-Farmatsevticheskii Zhurnal, Vol. 56, No. 12, pp. 23 – 26, December, 2022.

References

- 1.Hu YZ, Li M, Zhang TT, Jin YG. Yaoxue Xuebao. 2016;51(12):1906–1912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.W.Wijagkanalan, S. Kawakami, Y. Higuchi, et al., J. Controlled Release, 149(1), 42 – 50 (2011); doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Rudokas M, Najlah M, Alhnan MA, Elhissi A. Med. Princ. Pract. 2016;25(Suppl. 2):60–72. doi: 10.1159/000445116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.A. L. Baptista, P. J. Coutinho, M. E. Real Oliveira, and J. I. Gomes, J. Liposome Res., 13(2), 111 – 121 (2003); doi: 10.1081/lpr-120020314. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Agassandian M, Mallampalli RK. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1831(3):612–625. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morimoto Y, Horie M, Kobayashi N, et al. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46(3):770–781. doi: 10.1021/ar200311b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.V. V. Salukhov, E. V. Kryukov, A. A. Chugunov, et al., Med. Sovet, No. 12, 162 – 172 (2021); doi: 10.21518/2079-701X-2021-12-162-172.

- 8.P. Horby, W. S. Lim, and J. R. Emberson, N. Engl. J. Med., 384(8), 693 – 704 (2021); doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.M. A. Pinzon, S. Ortiz, H. Holguin, et al., PLoS One, 16(5), e0252057 (2021); doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.O. A. Kulikov, A. V. Zaborovskii, D. V. Yunina, et al., Chel. Ego Zdorov’e, 24(3), 39 – 49 (2021); doi: 10.21626/vestnik/2021-3/05.

- 11.O. A. Kulikov, V. P. Ageev, E. E. Marochkina, et al., Res. Results Pharmacol., 5(2), 23 – 41 (2019); doi: 10.3897/rrpharmacology.5.35529.

- 12.M. J. Altube, S. M. Selzer, M. A. de Farias, et al., Nanomedicine, 11(16), 2103 – 2117 (2016); doi: 10.2217/nnm-2016-0165. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Soni PK, Saini TR. Pharm. Nanotechnol. 2021;9(5):347–360. doi: 10.2174/2211738509666211124145848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O. A. Kulikov, Vopr. Biol., Med. Farm. Khim., 20, No. 6, 24 – 27 (2017).