Abstract

The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is considered as one of the most disastrous pandemics for human health and the world economy. RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) is one of the key enzymes that control viral replication. RdRp is an attractive and promising therapeutic target for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 disease. It has attracted much interest of medicinal chemists, especially after the approval of Remdesivir. This study highlights the most promising SARS-CoV-2 RdRp repurposed drugs in addition to natural and synthetic agents. Although many in silico predicted agents have been developed, the lack of in vitro and in vivo experimental data has hindered their application in drug discovery programs.

Keywords: Polymerase, RdRp, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Remdesivir, Favipiravir, Molnupiravir, Computational studies

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Infectious diseases are still one of the major public health challenges. Diverse microorganisms including viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites are the main cause of infectious diseases [1]. Many epidemics and pandemics due to HIV/AIDS, avian flu, swine flu, Ebola, Zika, SARS-CoV-2, and monkeypox viruses have occurred in the last few decades [2,3]. The entire global population is still suffering from emergent and recurring infectious diseases caused by many microorganisms [4]. About two years ago, the WHO (World Health Organization) announced COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019) as a public health concern (March 11, 2020) due to the widespread global impact of an infectious SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2) parasite. More than 6.6 million deaths and 639 million infected patients have been reported till the beginning of December 2022 [5,6]. The first identified case of SARS-CoV-2 was reported in the local fish and wild animal market in Wuhan City, China [7]. SARS-CoV-2 is a RNA zoonotic virus (family: Coronaviridae, order: Nidovirales, genus: Betacoronavirus). It is mainly found in bats. After this virus was transferred to humans in China, it then widely spread to all other countries, leading to a global pandemic [[8], [9], [10]]. Four genera (α, β, δ, and ɤ) of coronavirus are known [11]. Several waves of SARS-CoV-2 infections have been recognized due to viral mutations. The most important variants of the virus are Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron variants. The new Omicron variant indicates that the epidemic/pandemic is far from its end due to its efficient human-to-human transmission [12]. The main symptoms due to the infection from this variant are fever, dry cough, diarrhea, and shortness of breath besides blood clotting and stroke in severe conditions [10,13]. Repurposed drugs and vaccination substantially helped to overcome the pandemic and retain the socioeconomic status and human life to normal [14].

SARS-CoV-2 belongs to a positive-sense single-stranded RNA viral group (ssRNA(+)). It can infect humans and largely spreads through close contact and by breathing droplets generated by coughing/sneezing. Its genetic material can directly act as a viral messenger RNA (mRNA) and translate into viral proteins in the host cell [[15], [16], [17]]. Several enzymes are involved in coronaviral replication. Thus, targeting these enzymes in drug discovery efforts might lead to promising antiviral drugs [18]. The SARS-CoV-2 nonstructural proteins including RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and main protease (Mpro) are crucial for viral genomic transcription and replication [17,19]. The crystal structures of both RdRP and Mpro are available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [[20], [21], [22]].

The enzyme RdRp is encoded in all RNA viruses. Viral RdRp is the main target for developing potent antiviral agents against SARS-CoV-2, not only due to its ability to accelerate the replication of RNA but also due to the lack of RdRp closely related host cell counterparts. Theoretically, the designed agent will selectively target the viral RdRp with no off-target side effects [23].

RdRp inhibitors are categorized into two classes based on their structure and location for binding to RdRp: nucleoside analog inhibitors (NIs) and non-nucleoside analog inhibitors (NNIs). Structurally, NIs are known to bind the RdRp protein at the enzyme active site, NNIs bind to the allosteric sites of RdRp. Several studies on RdRp inhibitors with various applications have been reported. Tian et al. reported a recent review for RdRp inhibitors however, most of the mentioned analogs are for pyrimidine-containing compounds (either NIs and NNIs) [24]. This current review adopts wider scope summarizing the natural and synthetic compounds as well as the repurposed drugs/active agents with RdRp inhibitory properties for treating SARS-CoV-2, with various heterocyclic scaffolds. Notably, the screening techniques for coronavirus RdRp are not as simple as those for proteases [25]. With increasing interest, a few studies on RdRp screening for coronavirus have been reported.

2. Drug repurposing

Development of new drug(s) usually involves many successive stages which are: design, synthesis, bio-properties investigation, formulation of prototypes, and pre-clinical and clinical trials. Due to the pandemic outbreak, drug repurposing is considered the most accessible and appealing approach for urgent identifying potential therapeutics to control the disaster and save human lives. Drug repurposing means the adoption of an existing broad-spectrum therapeutical entity of potential efficacy and minimal adverse effects for clinical application of the infected patients supported by pre-clinical establishments. Drug repurposing strategy is superior to traditional drug discovery in terms of cost and time reduction. In addition to a lower failure rate compared with the traditional approaches owing to its well-established efficacy, metabolic characteristics, dose determination, and safety or toxicity issues [[26], [27], [28]]. FDA (food and drug administration) approved several drugs of other pathophysiological under the emergency use authorization of which antiviral drugs (remdesivir, penciclovir and favipiravir) and antimalarial drugs (chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine) as anti-COVID-19 agents. Meanwhile, adverse effects humbled the clinical applicability of some of them [[29], [30], [31]].

2.1. Remdesivir (RDV, formerly GS-5734)

Yin et al. investigated the inhibition of the RdRp from SARS-CoV-2 by remdesivir. The complex structure of SARS-CoV-2 RdRp and remdesivir reveals that the partial double-stranded RNA template is inserted into the central channel of the RdRp, where remdesivir is covalently incorporated into the primer strand at the first replicated base pair and terminates chain elongation [32]. Remdesivir (RDV) is the first FDA-authorized drug to treat COVID-19 patients with severe conditions (on Oct. 22, 2020) [33,34]. Remdesivir is a phosphoramidite prodrug of a 1′-cyano-substituted adenosine nucleotide analog, which acts as an RNA polymerase inhibitor (regulate genomic replication) developed initially by Gilead Sciences for Ebola viral infections treatment in 2014 [35]. It has been mentioned as a broad-spectrum antiviral property against various acute viral infections caused by different ssRNA viruses including Hendra virus, Lassa fever virus, Junin virus, Nipah virus, and coronaviruses (SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV) in addition to the efficacy in the therapeutical composition against HCV (hepatitis C virus) and HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) [[36], [37], [38]]. Remdesivir is the first candidate as an anti-COVID-19 drug owing to its broad spectrum as an antiviral agent, especially on coronaviruses (SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV), this encourages Gilead Sciences to repurpose it to treat patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 and approved by FDA in 2020 for treatment patient with COVID-19 infection [34,39].

The broad-spectrum antiviral properties of Remdesivir are attributed to its ability to be metabolized in the host cell as nucleoside triphosphate (RDV-TP). Consequently, it can be integrated within the nascent viral RNA chains due to the RdRp action. Thus, viral RNA synthesis is terminated (Fig. 1 ) [34,40]. In the VERO-E6 assay, the EC50 of Remdesivir is 0.77 μM, and the CC50 = >100 μM (SI, selectivity index = >129.87) [41].

Fig. 1.

Strucure of Remdesivir prodrug and its active triphosphate derivatives (RDV-TP).

To improve the t1/2 and in-vivo metabolism of the Remdesivir, Wen et al. replaced the hydrogen in the active molecular group with isotope deuterium as the carbon-deuterium bonds (C–D) are more stable than carbon-hydrogen bonds(C–H) [24,42,43].

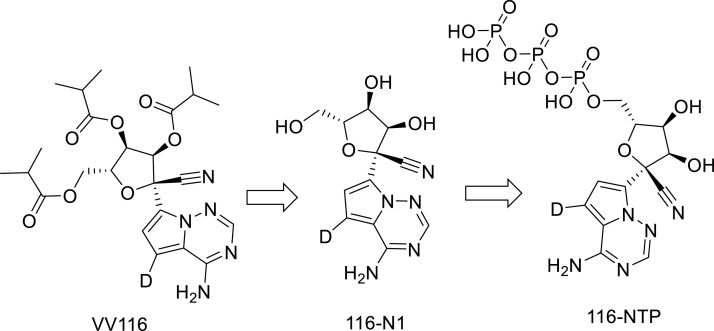

New oral RDV derivatives were found to demonstrate SARS-CoV-2 RdRp inhibitors such as VV116 and GS-621763. VV116 (JT001) is a tri-isobutyrate ester RDV prodrug derivative. VV116 is rapidly metabolized into the parent nucleoside (116-N1) in vivo which is intracellularly converted to the active form nucleoside triphosphate that incorporates with RdRp, thus inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 replication [44] (Fig. 2 ). VV116 exhibited potent activity against a panel of SARS-CoV-2 variants [45,46] with satisfactory safety in phase I studies [44].

Fig. 2.

Structures of W116, 116-N1 and 116-NTP.

Another oral RDV derivative is GS-621763 metabolized in plasma to GS-441524 (Fig. 3 ). In the lung the triphosphate effectively controls the SARS-CoV2 replication. Both metabolites GS-621763 and GS-441524 possess anti-SARS-CoV-2 properties against different variants. Viral proliferation was completely terminated by oral GS-621763 [47].

Fig. 3.

Structures of GS-621763 and GS-441524.

2.2. Favipiravir

Another nucleotide analog inhibitor of RdRp is Favipiravir (FPV, favilavi, or Avigan). Favipiravir was originally developed by Toyama Chemicals, Japan, and approved as anti-influenza in 2014 in Japan [48,49]. Favipiravir is a RdRp inhibitor that has demonstrated antiviral activity against influenza virus H1N1 infection [48]. During the Ebola virus outbreak in West Africa, Favipiravir has been evaluated against human Ebola virus infection. It reveals a promising activity against Ebola virus infection in the mouse model however, poor activity was observed in human Ebola infections [50].

Favipiravir showed effectiveness in controlling the progression of the SARS-COV-2 virus. Patients with mild COVID-19 had a potential clinical recovery rate [51]. While treating severe COVID-19 patients with Favipiravir, an improvement in the lymphocyte count was recorded [52]. Therefore, the clinical tackle was recommended for mild-to-moderate COVID-19 patients with Favipiravir [53].

Favipiravir (pro-drug) metabolized in the body to the active favipiravir-ribofuranosyl-5′-triphosphate (FPV-RTP) via ribosylation and phosphorylation which binds to the active site of the viral RdRp thus terminates the replication of viral RNA (Fig. 4 ) [54]. In Vero-E6 assay, Favipiravir reveals EC50 = 61.88 and CC50 = >400 μM (SI = 6.46) [41].

Fig. 4.

Structures of Favipiravir and its ribofuranosyl-triphosphate analogue.

2.3. Molnupiravir

Molnupiravir (EIDD-1931 or NHC) is the isopropyl ester pro-drug of the ribonucleoside analog β-D-N4-hydroxycytidine [55]. It can inhibit SARS-CoV-2 replication in human airway epithelial cell cultures and various animal models [56,57]. Clinical trial studies supported the effectiveness of Molnupiravir against SARS-CoV-2 relative to Placebo (inert medication with no therapeutical value) [58]. Molnupiravir was granted emergency use authorization by FDA and MRHA (medicines and healthcare products regulatory agency) for the treatment COVID-19 patients (Fig. 5 ) [59].

Fig. 5.

Molnupiravir, COVID-19 therapeutical agent.

The inhibitory mechanism of Molnupiravir is quite similar to that of Favipiravir. The oral administration of molnupiravir rapidly appears in plasma and is converted to its triphosphate form in cells. The active NHC triphosphate form is incorporated into viral RNA in place of cytosine or uracil by RdRp, causing a break of viral replication [56,60,61]. The IC50 = 1.965, 0.7556 μM of Molnupiravir are against WT and Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variants, respectively in Calu-3 cells [62].

2.4. Galidesivir

Galidesivir (BCX4430) (Fig. 6 ) is an adenosine analog with RdRp replication inhibitory activities against many RNA viruses including Ebola, Zika, Marburg, and yellow fever (in vitro and in animal models) [63,64]. In Syrian golden hamster models, it was tested as anti-SARS-CoV-2 reducing the lung pathology upon the treatment initiated 24 h before the viral infection, compared with untreated controls [65]. The Galidesivir triphosphate is the active substrate responsible for binding to the active site of the viral RdRp and terminates the replication of viral RNA [66]. Table 1 exhibits the anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity of Galidesivir in different cell cultures [65].

Fig. 6.

Galidesivir(BCX4430) RdRNAp replication inhibitor.

Table 1.

The anti-SARS-CoV-2 properties of Galidesivir against different cell cultures.

| Cell line | SARS-CoV-2 strains | Assay | Incubation period | EC50 (μM) | EC90 (μM) | CC50 (μM) | SI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 | WA1/2020 | VYRa | 24 h | n.d.b | 14.19 | 82.8 | 5.8 |

| Vero-76 | WA1/2020 | VYRa | 24 h | n.d.b | 10.94 | >295.7 | >27 |

| CPEc | 50.3 | 5.8 | |||||

| Calu-3 | WA1/2020 | Imaging | 2 h | 14.15 | n.d. | >50 | >3.5 |

VYR = Viral Yield Reduction.

n.d. = not determined.

CPE = cytopathic effect.

2.5. Ribavirin

Ribavirin (RBV,1-β-d-ribofuranosyl-1,2,4-triazole-3-carboxamide) is a guanosine analog (Fig. 7 ). Ribavirin has a broad antiviral spectrum against in vitro human cell line and several animal models [67]. It was repurposed to treat COVID-19, and reflected a promising activity against SARS-CoV-2 [68,69]. RBV was reported to have a high survival rate in severe patients due to its ability for viral clearance (observational study) [70]. Another clinical trial (Phase II) demonstrated that a combination of RBV, interferon beta-1b, and lopinavir-ritonavir, is a potential treatment for mild to moderate COVID-19 patients [71]. Hemolytic anemia in addition to the reduction of calcium and magnesium in the elder besides the restriction for pregnant women are the serious adverse effects of RBV [72]. The active substrate RBV triphosphate (RBV-TP) is formed via the host cell kinases, which pairs with the uridine triphosphate or cytidine triphosphate in the RNA template resulting in lethal mutagenesis and so prevents viral RNA replication [73]. The EC50 = 7.1, CC50 = 160 μM (SI = 16) are of Ribavirin in Calu-3 assay [74].

Fig. 7.

Ribavirin, a broad spectrum antiviral agent.

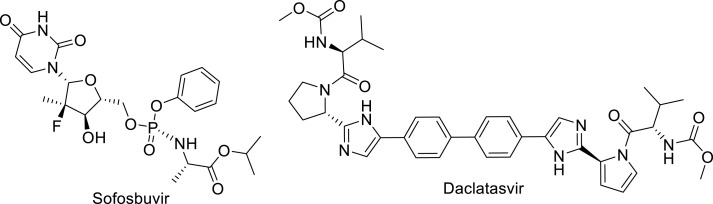

2.6. Sofosbuvir and daclatasvir

The replication process of HCV is similar to that of coronavirus, especially at the start of the disease. Anti-HCV therapies such as Sofosbuvir (HCV polymerase inhibitor) [75] and Daclatasvir (RNA replication and virion assembly inhibitor) [76] were suggested to have promising potential in the treatment of COVID-19 (Fig. 8 ) [74]. Randomized clinical trials on moderate or severe COVID-19 patients demonstrated that sofosbuvir and daclatasvir reducing the hospital stay duration relative to the standard care alone. This is attributed to the daclatasvir/sofosbuvir antiviral efficacy on SARS-CoV-2 replication in respiratory cells [74,77]. The EC50 = 7.3, 1.1 and CC50 = 512, 38 μM are for Sofosbuvir and Daclatasvir, respectively in Calu-3 assay [74].

Fig. 8.

Sofosbuvir and, Daclatasvir, repurposed drugs fir COVID-19.

Alovudine and AZT which are nucleotide-related structures to Sofosbuvir (2′-fluoro-2′-methyl-UTP) were investigated as anti-SARS-CoV RdRp-inhibitors (Fig. 9 ). They terminate RNA synthesis and replication of the virus in model polymerase extension experiments [78].

Fig. 9.

Structural of Alovudine and azidothymidine (AZT).

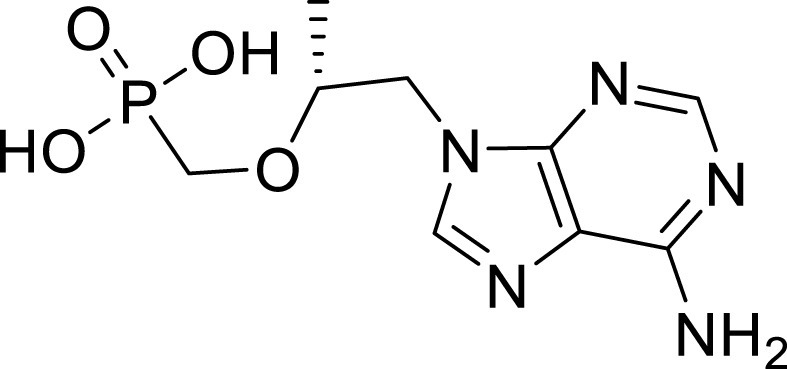

2.7. Tenofovir

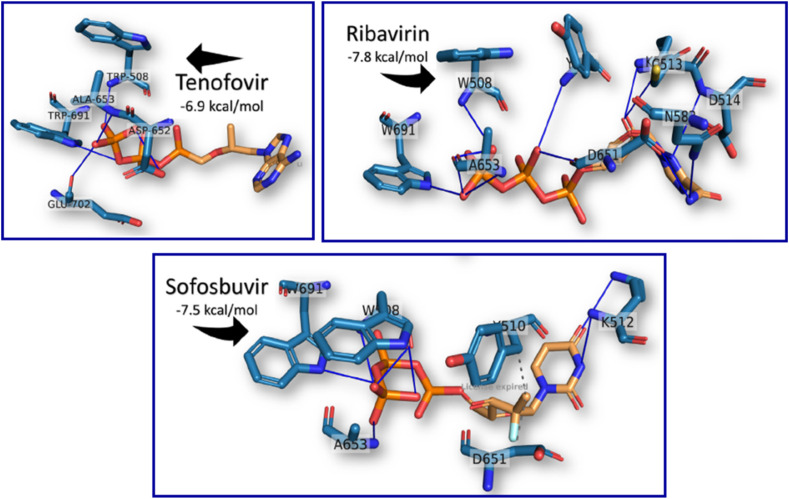

Tenofovir is a broad-spectrum antiviral drug active against the HIV and hepatitis B virus (HBV). The active triphosphate form of the tenofovir diphosphate acts as a terminator of viral RNA subsequent polymerase synthesis (Fig. 10 ) [79,80]. Few in vitro studies on tenofovir or its prodrug formulations have been reported. The results are not promising and are contradictory [81,82]. Although these reports, in silico studies mentioned that tenofovir binds strongly to SARS-CoV-2 RdRp, with binding energies close to other successful drugs (Remdesivir, Galidesivir, Ribavirin, and Sofosbuvir) with no supporting biochemical observations (Fig. 11 ) [83].

Fig. 10.

Structure of tenofovir.

Fig. 11.

Docking poses of Tenofovir, Ribavirin and Sofosbuvir in SARS HCoV RdRp (PDB ID: 6NUR), using AutoDock Vina software [80].

2.8. AT-527

AT-527 is an orally available prodrug of a guanosine nucleotide analog that acts as a potent broad-spectrum anti-coronavirus inhibitor in a variety of cell lines by targeting the RdRp activity (Fig. 12 ) [84]. AT-527 is converted by cellular enzymes to the active triphosphate metabolite, AT-9010. AT-527 recently entered phase III clinical trials to treat COVID-19 [85]. AT-9010 can bind to the active site of RdRp exhibiting promising efficacy against COVID-19 [86].

Fig. 12.

Structures of AT-527 and AT-9010.

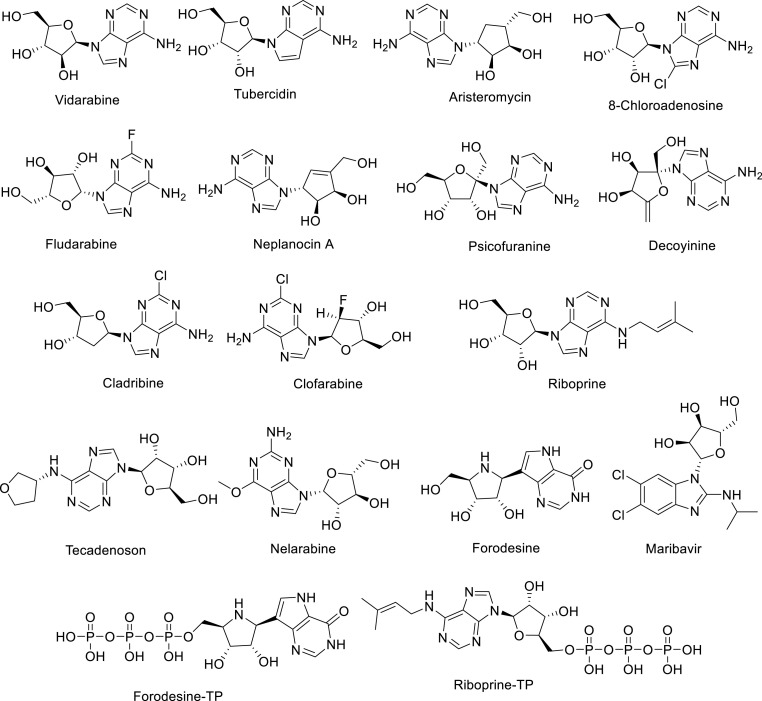

Nucleoside analogs were used in searching for potent anti-SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors with both SARS-CoV-2-RdRp and SARS-CoV-2 exonuclease (ExoN) dual inhibitory enzyme effects as a strategy to combat COVID-19 [87]. Based on the pharmacodynamic/pharmacokinetic results and predicted anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities, analogs were selected for docking studies (Fig. 13 ). Blind docking was performed via MOE (molecular operating environment) software using SARS-CoV-2 RdRp (PDB, ID: 7BV2) and ExoN (PDB, ID: 7MC6) proteins from PDB (protein data bank). The molecular docking results revealed that some of the compounds were with promising binding energies in both enzymes relative to Riboprine-TP and Forodesine-TP (triphosphates). The assumptions were supported by in vitro testing as anti-RdRp, anti-ExoN, and anti-SARS-CoV-2 [88].

Fig. 13.

Strucure of promising nucleosides as anti-RdRNAP, anti-ExoN, and anti-SARS-CoV-2 relative to Riboprine-TP and Forodesine-TP.

3. Natural RdRp inhibitors

Natural isolate compounds have a significant impact on drug development and pharmacotherapy due to their tremendous structural, and chemical variety, and relatively low toxicity. Numerous natural products were discovered to have medicinal potential, including morphine, quinine, paclitaxel, penicillin, lovastatin, and doxorubicin. Natural compounds were and still are one of the major sources for new medications, with an estimated 34% of approved new chemical entities between 2000 and 2014 coming from natural compounds isolated from plants, microorganisms, and other resources. Many analogs of potential bio-properties are mimicked based on the chemical scaffold of promising natural biologically active entities [[89], [90], [91]]. A famous example is Artemisinin, one of the recent naturally isolate compounds with high potential as anti-malarial (Plasmodium falciparum) properties described by Tu Youyou (Noble Prize winner in 2015). Artemisinin is extracted from the plant Artemisia annua (sweet wormwood, a herb used in traditional medicine in Chinese) [92]. Several review articles reported the antiviral properties of some natural isolate compounds [[93], [94], [95]].

3.1. Benzopyrans

Flavonoids and their glycosides or their bioisosteres displayed antiviral properties inhibiting different stages of the virus infective cycle (inhibition of viral protease, RNA polymerase, and mRNA). Different reports mentioned the efficacy against some RNA viruses (SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and influenza A virus) [[96], [97], [98]].

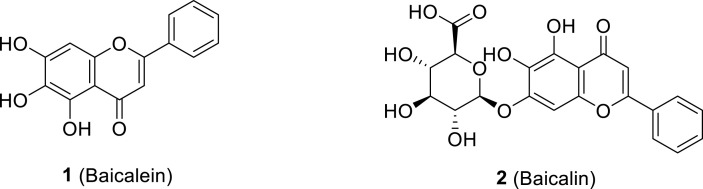

Zandi et al. reported the antiviral properties of baicalein 1 and baicalin 2 (polyphenolic flavonoids accessible in traditional Chinese medicine extracted from Scutellaria baicalensis root) against SARS-CoV-2 through cell-based and biochemical studies (Fig. 14 ). Both compounds inhibited activity against SARS-CoV-2 RdRp with higher efficacy for baicalein than that of baicalin. Antiviral evaluation assay of baicalein and baicalin exhibited 99.8% and 98% inhibition of SARS-CoV-2, respectively (at 20 μM). Baicalein also showed more potency against SARS-CoV-2 relative to baicalin with an EC50 = 4.5 μM and EC90 = 7.6 μM. Both compounds also demonstrated anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity when tested in Vero-E6 and human Calu3 cells with safe cytotoxicity (EC50 = 4.5, 9.0; 1.2, 8.0; CC50 = 8.6, >100; 91, >100 μM for baicalein and baicalin in Vero-E6 and Calu3 cells, respectively). In the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp testing of the compounds using Remdesivir-triphosphate (RDV-TP, reference standard), baicalein significantly revealed higher potency against RNA polymerase than that of RDV-TP and baicalin. In silico studies (PDB, ID: 6XQB) using AutoDock Vina 1.5.6 and Discovery Studio 2.5 software showed that both compounds were with higher affinity to SARS-CoV-2 RdRp compared with Remdesivir (Fig. 15 ) [99].

Fig. 14.

Baicalein (1) and Baicalin (2) polyphenolic flavonoids of potential anti-SARS-CoV-2 RdRp.

Fig. 15.

Baicalein and baicalin in the active site of PDB, ID: 6XQB [99].

A series of 4H-chromen-4-one containing compounds were subjected to virtual screening studies with the coronavirus main protease (Mpro, also called 3CLpro “3-chymotrypsin-like cysteine protease”, PDB: 6LU7) using AUTO-DOCK and VINA software. The top hits (isoginkgetin, bilobetin, and afzelin molecules, Fig. 16 ) were subjected to in vitro testing (SARS-CoV-2–infected Vero cell drug screening assay). Isoginkgetin was the most potent active agent discovered with IC50 = 22.81 μM, relative to IC50 = 7.18, 11.63, and 11.49 μM for the standard references Remdesivir, Chloroquine, and Iopinavir, respectively. Isoginkgetin was also docked in RdRp (PDB: 6M71) (Fig. 17 ). Good binding affinities were noticed in both SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and RdRp docking studies supporting its efficacy [100].

Fig. 16.

Strucures for Isoginkgetin, Bilobetin and, Afzelin.

Fig. 17.

3D-conformations of (A) afzelin, (B) bilobetin, (C) isoginkgetin, (D) chloroquine, (E) remdesivir, and (F) lopinavir in PDB: 6 M71 [100].

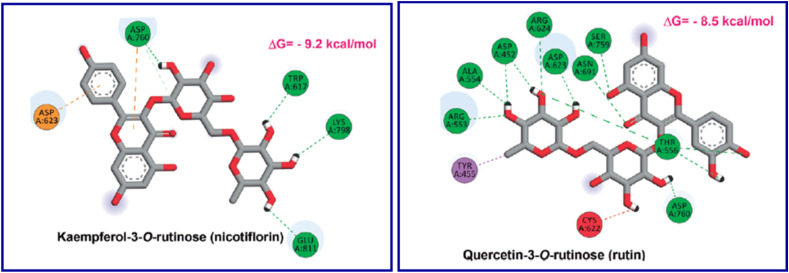

In silico studies adopting the docking technique (AutoDock Vina software) of quercetin-3-O-rutinoside (rutin) and kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside (nicotiflorin) “flavonoid glycosides found in Dysphania ambrosioides” in the SARS-CoV-2 MPRO (PDB: 6W63) and RdRp (PDB: 6M71), support the possibility as promising agents against SARS-CoV-2. However, intensive in vitro and in vivo studies are still needed for these assumptions (Fig. 18, Fig. 19 ) [101].

Fig. 18.

Rutin and Nicotiflorin, promising anti-SARS-CoV-2 based on in silico studies.

Fig. 19.

Nicotiflorin and rutin in the active site of PDB: 6M71 [101].

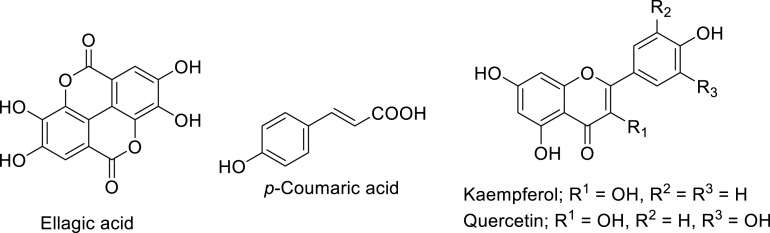

Similarly, various flavonoids and triterpenes were considered in docking studies against RdRp (PDB: 7BV2) utilizing Schrödinger software revealing promising docking scores with no experimental supporting (in vitro/in vivo) observations [102]. Ellagic acid, p-Coumaric acid, kaempferol, and quercetin (Fig. 20 ) were also mentioned as anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents due to docking studies in Mpro (PDB: 6LU7) and RdRp (PDB: 6M71) utilizing AutoDock Vina software (Fig. 21 ) [103].

Fig. 20.

Ellagic acid, p-Coumaric acid, Kaempferol, and Quercetin, promising anti- SARS-CoV-2 supported by in silico studies.

Fig. 21.

Docking confirmations of (a) ellagic acid, (b) hesperetin, and (c) kaempferol in PDB: 6M71 [103].

Theaflavin extracted from Camellia sinensin, is a polyphenolic compound found in black tea with a considerable medicinal value useable in Chinese traditional medicine (Fig. 22 ). Theaflavin and theaflavin gallate derivatives exhibit broad-spectrum antiviral properties against several viruses, influenza A and B and hepatitis C virus [104,105]. In silico studies utilizing theaflavin revealed promising efficacy against RdRp of SARS-CoV-2. Similar observations were also noticed for SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV, using the UCSF Chimera and SWISS-MODEL (Fig. 23 ) [106].

Fig. 22.

Theaflavin and theaflavin-3,3′-di-O-gallate.

Fig. 23.

2D-interaction diagram of Theaflavin and SARS‐CoV‐2 RdRp by the Blind Dock server [106].

In-silico studies, including molecular docking (DOCK 6 software) and molecular dynamics simulations, identified four phytochemicals, from Indian medicinal plants, swertiapuniside, and amarogentin (from Swertia chirayita), cordifolide A (from Tinospora cordifolia) and sitoindoside IX (from Withania Somnifera) as RdRp inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 24 ) [107].

Fig. 24.

Phytochemicals from Indian medicinal plants of potential RdRp inhibitors.

3.2. Alkaloid

Alkaloids are found in Cryptolepis sanguinolenta (West African herb with antiviral, antiplasmodial and anti-inflammatory properties) [108]. In silico studies for the potential anti-SARS-CoV-2, the main protease (Mpro, PDB: 6LU7) and RdRp (PDB: 6M71) were considered for the alkaloid analogs. Cryptomisrine, cryptospirolepine, cryptoquindoline, and biscryptolepine showed promising affinity towards RdRp enzyme, suggesting their potential inhibitory properties towards both proteins (Fig. 25, Fig. 26 ) [109].

Fig. 25.

Cryptomisrine, cryptospirolepine, cryptoquindoline and biscryptolepine of potentional inhibitory properties against MPro and RdRp through in silico studies.

Fig. 26.

View of 3D- (left) and 2D-interactions (right) of (a) cryptomisrine, (b) cryptospirolepine and (c) cryptoquindoline with RdRp enzyme active pocket [109].

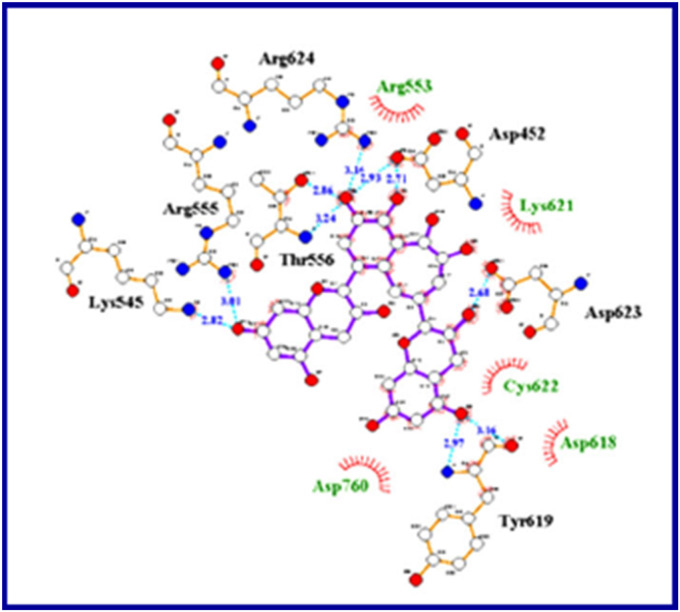

In another in silico molecular docking study for some of the food bioactive compounds, three alkaloids phycocyanobilin (found in Spirulina), riboflavin (found in eggs, meat, fruits), cyanidin (found in grapes and berries) revealed high binding affinity towards SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and RdRp enzymes relative to the antiviral drugs Remdesivir, Nelfinavir, and Lopinavir utilizing AutoDock Vina software (Fig. 27, Fig. 28 ) [110].

Fig. 27.

Phycocyanobilins, riboflavin and cyanidin of potential inhibitory properties against Mpro and RdRp enzymes through in silico studies.

Fig. 28.

Docked compounds “(a) Phycocyanobilin, (b) Riboflavin, (c) Cyanidin and (d) Daidzein” in RdRp [110].

3.3. Polycyclic aromatic

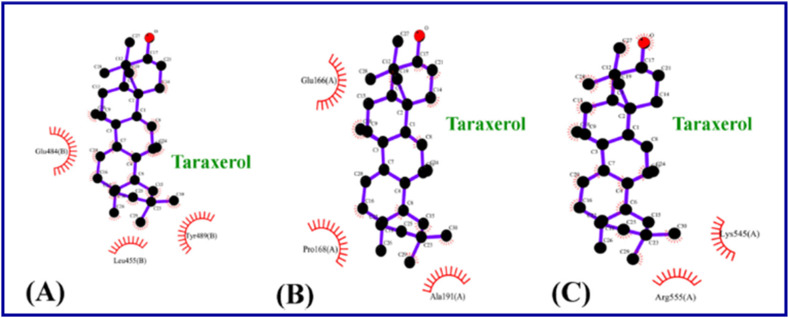

The potential inhibitory effects of phytocompounds derived from Clerodendrum spp (with the application against respiratory disorders problems) [111,112] against SARS-CoV-2 RdRp (PDB: 7BV2) were studied by molecular docking (AutoDock Vina software). Taraxerol, friedelin, and stigmasterol displayed the highest binding potential relative to Remdesivir and Favipiravir. They also exhibited promising inhibitory affinity against the Mpro (SARS-CoV-2 spike protein) (Fig. 29, Fig. 30 ) [113].

Fig. 29.

Phytocompounds of potential inhibitory properties aganst SARS-CoV-2Mpro and RdRp through in silico studies.

Fig. 30.

Interaction of Taraxerol in (A) SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, (B) SARS-CoV-2 Mpro and (C) SARS-CoV-2 RdRp [113].

4. Synthetic non-nucleoside RdRp inhibitors

4.1. Indole

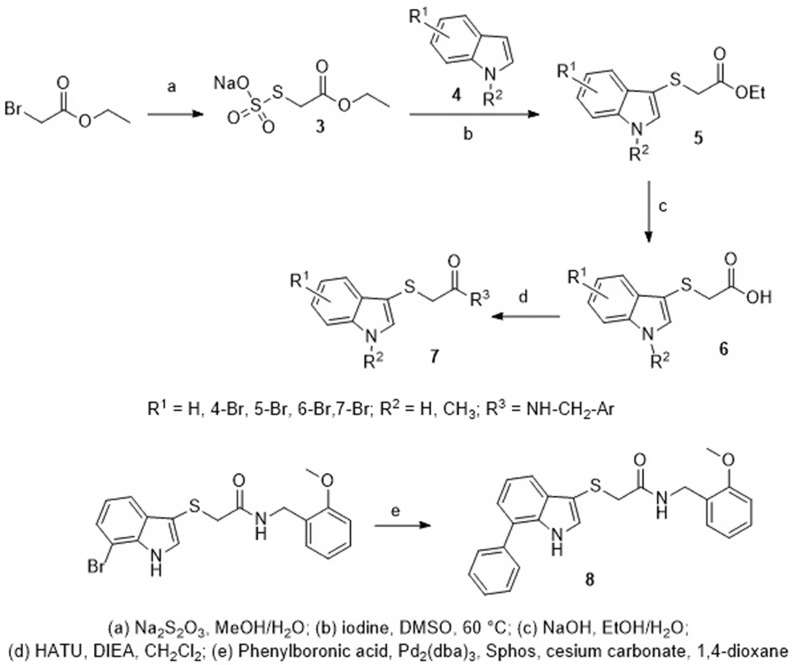

A series of 2-[(indol-3-yl)thio)]-N-benzyl-acetamides 7 were synthesized through the reaction of the Bunte salt ethyl acetate-2-sodium thiosulfate 3, and indole derivatives 4 to afford the indolyl thioacetates 5. The hydrolysis of 5 yielded the corresponding acids 6. Finally, the coupling reaction of 6 with different substituted benzylamines afforded the target products 7. Compound 8 was also generated via Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling of its corresponding analog 7 with phenylboronic acid (Scheme 1 ) [114].

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 2-[(indol-3-yl)thio]-N-benzyl-acetamides 7 and 8.

CoV-RdRp-Gluc reporter assay was considered for evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 RdRp inhibitory properties of the synthesized agents. Five compounds (7a-7d, 8) showed dose-dependent inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 RdRp with IC50 values of 1.11–4.55 μM while the IC50 of the positive control (Remdesivir) was 1.19 μM (Fig. 31 ). The most potent five compounds (7a-7d, 8) were further evaluated for their ability to inhibit the RNA synthesis by SARS-CoV-2 RdRp. All of them decreased the levels of viral plus- and minus-strand Gluc RNA in a dose-dependent manner (at 5 and 10 μM concentrations). Three compounds 7b, 7d, and 8 diminished the levels of both plus- and minus-strand Gluc RNA more potently than the Remdesivir. The antiviral effect of the most potent compound 7d was evaluated against the human coronavirus strains HCoV-OC43 (β-coronavirus as SARS-CoV-2) and HCoVNL63 (α-coronavirus as SARS-CoV-2) in a cell-based assay in vitro. It was found that compound 7d inhibits the replication of HCoV-OC43 more effectively than Remdesivir in a dose-dependent manner [114].

Fig. 31.

Effective candidates in the CoV-RdRp-Gluc reporter assay.

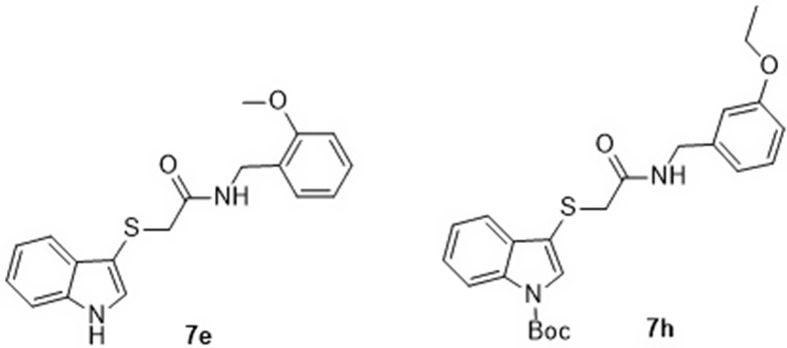

The 2-[(1H-indol-3-yl)thio]-N-phenyl-acetamide, 2-[(indol-3-yl)thio)-N-benzyl-acetamide (Scheme 1), and 2,3-dithioindole derivatives (synthesized according to Scheme 2 ) were screened through CoV-RdRp-Gluc assay. Compound 7h (R1 = H, R2 = Boc, R3 = 3-EtOC6H4) represented the most promising agent (EC50 = 1.41 μM, selectivity index = >70.92). However, the other compounds showed good to mild RdRp inhibition effect with an EC50 = 1.70, 2.75, 2.53, 3.07, 1.05 μM for 7e (R1 = R2 = H, R3 = 2-MeOC6H4), 7f (R1 = R2 = H, R3 = 3,4-Cl2C6H3), 7g (R1 = R2 = H, R3 = 3-H3CC6H4), 9a (R = 3,4-Cl2), and Remdesivir respectively [115].

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 2,3-dithioindoles 9.

High potency against SARS-CoV-2 RdRp was revealed by compounds 7e and 7h (EC50 = 1.58, 1.18 μM, respectively measured in HEK293T cells with CCK-8 kits) relative to Remdesivir (EC50 = 0.73 μM, measured in A549 cells with CCK-8 kits) [115] (Fig. 32 ).

Fig. 32.

Compounds 7e and 7h with high potency against SARS-CoV-2 RdRp.

4.2. Quinoline

Quinoline derivatives 10a‒c (Fig. 33 ), that considered previously against the influenza A virus, were repurposed as SARS-CoV-2-RdRp inhibitors. The assumed compounds revealed promising inhibitory properties relative to Remdesivir at 10 μM (95.03%, 92.85%, and 74.94% for 10a‒10c, respectively). The CC50 values for 10a‒10c were 70.79, 72.44, and 79.43 μM, respectively, with therapeutic indexes 65.55, 34.83, and 20.26, respectively reflecting their low cytotoxicity. Compound 10a showed antiviral activity against human coronavirus strains HCoV-OC43 and HCoVNL63 determine by the cell-based assay (HCT-8 and LLC-MK2 cell lines infected with HCoV-OC43 “β-coronavirus as SARS-CoV-2” and HCoV-NL63 (α-coronavirus as SARS-CoV-2″) [116].

Fig. 33.

Quinolines 10a-c of promising SARS-CoV-2-RdRp inhibitory properties.

4.3. Suramin

A 100 year-old-drug, Suramin (Fig. 34 ) is identified as a potent inhibitor of the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp and acts by blocking the binding of RNA to the enzyme. Biochemical studies suggest Suramin and its derivatives are at least 20-fold more potent than Remdesivir. The 2.6 Å cryo-electron microscopy structure of the viral RdRp bound to Suramin uncovers two binding sites of which one directly blocks the binding of the RNA template strand and the other clashes with the RNA primer strand near the RdRp catalytic site, thus inhibiting RdRp activity. The IC50 values obtained from the solution-based assays of RdRp inhibition for Suramin is 0.26 μM, and for Remdesivir in its triphosphate form (RDV-TP) is 6.21 μM under identical assay conditions, suggesting that Suramin is at least 20-fold more potent than RDV-TP [117].

Fig. 34.

Suramin, a promising RdRp inhibitor.

5. In silico proposed compounds

In silico techniques help design bioactive agents and identify anti-SARS-CoV-2 hits [118,119]. Diverse acyclic [120] and heterocycles [[121], [122], [123]] of different scaffolds (triazole [124], oxadiazole [125], thiadiazole [126], indole [127], pyridine [128], pyrimidine [129] and coumarin [130]) were predicated as effective inhibitory agents for SARS-CoV-2 RdRp. However, the lack of experimental in vitro and in vivo observed results hindered the usefulness of these proposed prospective compounds. Recently, Saha et al. explored the impact of natural products (Tellimagrandin I, SaikosaponinB2, Hesperidin (−)-Epigallocatechin Gallate) on SARS-COV-2 RdRp protein [131].

In addition to the nucleoside and non-nucleoside based RdRp inhibitors, many lead candidates were identified through molecular docking and homolog model-based screening. Parvez et al. revealed that antibacterial drugs (fidaxomicin, ivermectin, rifabutin, and rifapentine) show potential interaction with SARS-COV-2 RdRp protein (Fig. 35 ). These drugs could be further investigated and considered as leads for further development of potential RdRp inhibitors for SARS-COV-2 [132].

Fig. 35.

Rifapentine, Rifabutin, Fidaxomicin and Ivermectin of potential interaction with SARS-COV-2 RdRNAP protein.

6. Predicted ADME-Tox Properties

Drug development is always a tedious and challenging task. Several strategies have been used in recent years to expertise the process which includes molecular hybridization, molecular docking, and consideration of ADME-Tox properties. As many drug candidates fail to reach their drug target because of their poor ADME-Tox profile. It is essential to pay attention for having balanced pharmacokinetic properties while developing new RdRp inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2. The descriptor and drug-likeness properties of the compounds included in this article were calculated with the Swiss ADME server [133] and STARDROP software [134]. Among the various parameters, we considered to include molecular weight (MW), logP, hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), number of rotatable bonds (RB), topological polar surface area (TPSA), ability to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), human intestine absorption (HIA), inhibition of P-glycoprotein (P-gp), human ether-a-go-go-related gene (hERG) potassium channel inhibition and bioavailability score (BS) as these properties play critical role (see Table 2 ). These data could serve as additional information for the new drug development process.

Table 2.

Predicted ADME-Tox properties.

| Compd. | MW | logP | HBD | HBA | RB | TPSA | BBB | HIA | P-gp substrate | hERG pIC50 | BS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remdesivir | 602.6 | 1.77 | 4 | 14 | 15 | 203.5 | – | – | yes | 4.60 | 0.17 |

| VV116 | 501.5 | 2.59 | 1 | 12 | 12 | 168.1 | – | + | no | 4.16 | 0.17 |

| GS-621763 | 501.5 | 2.59 | 1 | 12 | 12 | 168.1 | – | + | no | 4.17 | 0.17 |

| Favipiravir | 157.1 | −1.25 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 88.84 | – | + | no | 3.28 | 0.55 |

| Molnupiravir | 329.3 | −0.34 | 4 | 10 | 6 | 143.1 | – | – | no | 3.85 | 0.55 |

| Galidesivir | 265.3 | −1.20 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 140.3 | – | + | yes | 3.69 | 0.55 |

| Ribavirin | 244.2 | −1.85 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 143.7 | – | – | no | 3.26 | 0.55 |

| Sofosbuvir | 529.5 | 1.19 | 3 | 12 | 11 | 158.2 | – | + | yes | 4.51 | 0.17 |

| Daclatasvir | 734.8 | 4.00 | 4 | 14 | 17 | 176.3 | – | + | yes | 4.57 | 0.17 |

| Alovudine | 244.32 | −0.44 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 84.32 | – | + | no | 4.21 | 0.55 |

| Azidothymidine | 267.2 | −0.02 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 134.1 | – | + | no | 4.09 | 0.55 |

| Tenofovir | 287.2 | −0.005 | 3 | 9 | 5 | 136.4 | – | – | yes | 4.61 | 0.55 |

| AT-527 | 581.5 | 2.03 | 4 | 14 | 12 | 185 | – | – | yes | 4.96 | 0.17 |

| Vidarabine | 267.2 | −1.05 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 139.5 | – | + | no | 4.19 | 0.55 |

| Tubercidin | 266.3 | −0.77 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 126.7 | – | + | no | 4.24 | 0.55 |

| Aristeromycin | 265.3 | −0.53 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 130.3 | – | – | yes | 4.47 | 0.55 |

| 8-Chloroadenosine | 301.7 | −0.49 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 139.5 | – | + | no | 4.29 | 0.55 |

| Fludarabine | 285.2 | −1.04 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 139.5 | – | + | no | 4.44 | 0.55 |

| Neplanocin A | 263.3 | −0.77 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 130.3 | – | + | yes | 4.61 | 0.55 |

| Psicofuranine | 297.3 | −1.7 | 5 | 10 | 3 | 159.8 | – | + | yes | 3.96 | 0.55 |

| Decoyinine | 279.3 | −1.22 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 139.5 | – | + | yes | 4.15 | 0.55 |

| Cladribine | 285.7 | 0.02 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 119.3 | – | – | no | 4.45 | 0.55 |

| Clofarabine | 303.7 | −0.19 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 119.3 | – | + | no | 4.47 | 0.55 |

| Riboprine | 335.4 | 0.23 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 125.6 | – | – | yes | 5.19 | 0.55 |

| Tecadenoson | 337.3 | −0.20 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 134.8 | – | – | yes | 7.83 | 0.55 |

| Nelarabine | 297.3 | −0.98 | 4 | 10 | 3 | 148.8 | – | + | no | 4.20 | 0.55 |

| Forodesine | 266.3 | −1.59 | 6 | 8 | 2 | 134.3 | – | + | no | 3.72 | 0.55 |

| Maribavir | 376.2 | 2.09 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 99.77 | – | + | yes | 5.17 | 0.55 |

| Forodesine-TP | 506.2 | −0.40 | 9 | 17 | 8 | 273.9 | – | – | yes | 2.35 | 0.11 |

| Riboprine-TP | 575.3 | 0.58 | 7 | 18 | 11 | 265.1 | – | – | yes | 3.55 | 0.11 |

| Baicalein | 270.2 | 0.31 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 90.9 | – | + | no | 4.54 | 0.55 |

| Baicalin | 446.4 | 2.94 | 6 | 11 | 4 | 187.1 | – | + | no | 3.03 | 0.11 |

| Isoginkgetin | 566.5 | 4.24 | 4 | 10 | 5 | 159.8 | – | + | no | 5.11 | 0.55 |

| Bilobetin | 552.5 | 3.81 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 170.8 | – | + | yes | 5.01 | 0.55 |

| Afzelin | 432.4 | 0.40 | 6 | 10 | 3 | 170.1 | – | – | no | 4.41 | 0.55 |

| Rutin | 610.5 | −0.82 | 10 | 16 | 6 | 269.4 | – | – | yes | 3.89 | 0.17 |

| Nicotiflorin | 594.5 | −0.69 | 9 | 15 | 6 | 249.2 | – | – | yes | 4.04 | 0.17 |

| Ellagic acid | 302.2 | 1.57 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 141.3 | – | + | yes | 5.16 | 0.55 |

| p-Coumaric acid | 164.2 | 1.47 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 57.53 | + | + | no | 3.58 | 0.55 |

| Kaempferol | 286.2 | 2.55 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 111.1 | – | + | no | 4.65 | 0.55 |

| Quercetin | 302.2 | 1.54 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 131.4 | – | + | no | 4.41 | 0.55 |

| Theaflavin | 564.5 | 1.65 | 9 | 12 | 2 | 217.6 | – | – | yes | 4.90 | 0.17 |

| Swertiapuniside | 598.5 | −1.18 | 9 | 16 | 7 | 258.4 | – | – | no | 4.22 | 0.17 |

| Amarogentin | 586.5 | 0.81 | 6 | 13 | 8 | 201.7 | – | – | yes | 4.08 | 0.11 |

| Cordifolide A | 598.7 | 0.34 | 5 | 12 | 7 | 185.3 | – | + | yes | 4.00 | 0.17 |

| Sitoindoside IX | 632.7 | 0.57 | 5 | 11 | 6 | 175.5 | – | + | yes | 4.29 | 0.17 |

| Cryptomisrine | 462.5 | 4.98 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 74.43 | – | + | yes | 5.65 | 0.17 |

| Cryptospirolepine | 504.6 | 5.70 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 44.27 | – | + | no | 6.17 | 0.55 |

| Cryptoquindoline | 448.5 | 6.74 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 35.64 | + | + | yes | 7.01 | 0.55 |

| Biscryptolepine | 462.5 | 7.93 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 35.64 | + | + | yes | 6.65 | 0.55 |

| Phycocyanobilin | 588.7 | 3.79 | 5 | 10 | 11 | 164.7 | – | – | yes | 2.64 | 0.11 |

| Riboflavin | 376.4 | −0.86 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 161.6 | – | + | no | 4.40 | 0.55 |

| Cyanidin | 287.2 | 2.09 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 112.4 | – | + | no | 4.72 | 0.55 |

| Taraxerol | 426.7 | 5.80 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 20.23 | + | + | no | 5.41 | 0.55 |

| Friedelin | 426.7 | 5.53 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 17.07 | + | + | no | 5.08 | 0.55 |

| Stigmasterol | 412.7 | 7.16 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 20.23 | + | + | yes | 6.28 | 0.55 |

| 7a | 386.5 | 4.56 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 36.1 | + | + | no | 5.40 | 0.55 |

| 7b | 310.4 | 3.16 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 36.1 | + | + | no | 4.91 | 0.55 |

| 7c | 465.4 | 5.37 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 36.1 | + | + | yes | 5.51 | 0.55 |

| 7d | 449.4 | 4.08 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 54.56 | – | + | yes | 5.07 | 0.55 |

| 7e | 326.4 | 2.84 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 54.12 | + | + | no | 4.27 | 0.55 |

| 7f | 440.6 | 4.57 | 1 | 6 | 11 | 69.56 | – | + | yes | 5.18 | 0.55 |

| 10a | 476.6 | 3.75 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 84 | – | + | yes | 5.41 | 0.55 |

| 10b | 461.1 | 3.75 | 1 | 7 | 10 | 80.76 | – | + | yes | 5.31 | 0.55 |

| 10c | 461.1 | 3.74 | 1 | 7 | 10 | 80.76 | – | + | yes | 5.31 | 0.55 |

| Suramin | 1297 | 1.97 | 12 | 29 | 22 | 483.8 | – | – | yes | 3.96 | 0.11 |

| Rifabutin | 847 | 2.90 | 5 | 15 | 5 | 205.6 | – | + | yes | 4.24 | nd |

| Rifapentine | 877 | 4.05 | 6 | 16 | 6 | 220.1 | – | + | yes | 6.24 | nd |

| Fidaxomicin | 1058 | 3.76 | 7 | 18 | 15 | 266.7 | – | – | yes | 4.82 | nd |

| Ivermectin | 875.1 | 3.33 | 3 | 14 | 8 | 170.1 | – | – | yes | 4.96 | nd |

Ideal values for oral drug candidates: MW ≥ 500; logP ≥5; HBD ≥5; HBA ≥10; RB ≥ 10; TPSA ≥140; BBB (−); HIA (+); P-gp substrate (yes); hERG pIC50 ≥ 5; BS ≥ 0.55.

7. Conclusion

SARS-CoV-2 is considered one of the most severe pandemics facing the global population. The development of efficient anti-SARS-CoV-2 drugs over a short time is associated with many challenges, considerable obstacles, and unknown difficulties. Among various modern approaches to adopt for developing potential drug candidates for SARS-CoV-2, rational drug design and drug repurposing strategies are key. In the past two years, RdRp is found to be a prime target as this enzyme has capable to combat viral replication. Some drugs have been identified as anti-SARS-CoV-2 RdRp accessible for mild and weak infectious patients. Numerous natural and synthetic molecules have also been investigated. However, drug candidates with higher potency are still in demand. In silico studies have been exploring the most in the search for potential drug candidates but without supporting in vitro and in vivo observations their accessibilities will be hindered for any drug discovery program. We believe the compiled information will develop an interest in this field among the research community and provide them with a deeper understanding of the requirements and importance of chemical scaffolds for designing potential RdRp inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported financially by National Research Centre, Egypt, project ID: 13060103. We also thank the Department of Chemistry and Physics at Augusta University for their support.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.https://www.emro.who.int/health-topics/infectious-diseases/index.html (accessed on Dec. 1, 2022)

- 2.Miroa J.M., Moreno A. The infectious diseases challenges facing Spain in 2040 require the specialty: A national and international survey. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clín. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.eimc.2022.08.009. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Santangelo O.E., Gianfredi V., Provenzano S. Wikipedia searches and the epidemiology of infectious diseases: a systematic review. Data Knowl. Eng. 2022;142 doi: 10.1016/j.datak.2022.102093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee M., Kim J.W., Jang B., Dove An infectious disease outbreak statistics visualization system. IEEE Access. 2018;6:47206–47216. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2867030. https://doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2867030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on Dec. 1, 2022)

- 6.World Health Statistics 2022: Monitoring Health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. ISBN 978-92-4-005114-0 (electronic version), ISBN 978-92-4-005115-7 (print version).

- 7.Lu H., Stratton C.W., Tang Y.-W. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: the mystery and the miracle. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:401–402. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678. https://doi:10.1002/jmv.25678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng L., Zhang L., Huang J., Nandakumar K.S., Liu S., Cheng K. Potential treatment methods targeting 2019-nCoV infection. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;205 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seliem I.A., Panda S.S., Girgis A.S., Moatasim Y., Kandeil A., Mostafa A., Ali M.A., Nossier E.S., Rasslan F., Srour A.M., Sakhuja R., Ibrahim T.S., Abdel-samii Z.K.M., Al-Mahmoudy A.M.M. New quinoline-triazole conjugates: synthesis, and antiviral properties against SARS-CoV-2. Bioorg. Chem. 2021;114 doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou P., Yang X.-L., Wang X.-G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.-R., Zhu Y., Li B., Huang C.-L., Chen H.-D., Chen J., Luo Y., Guo H., Jiang R.-D., Liu M.-Q., Chen Y., Shen X.-R., Wang X., Zheng X.-S., Zhao K., Chen Q.-J., Deng F., Liu L.-L., Yan B., Zhan F.-X., Wang Y.-Y., Xiao G.-F., Shi Z.-L. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nascimento Junior J.A.C., Santos A.M., Quintans-Junior L.J., Walker C.I.B., Borges L.P., Serafini M.R. SARS, MERS and SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) treatment: a patent review. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2020;30:567tic. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2020.1772231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Araf Y., Akter F., Tang Y.‐d., Fatemi R., Parvez S.A., Zheng C., Hossain G. Omicron variant of SARS‐CoV‐2: genomics, transmissibility, and responses to current COVID‐19 vaccines. J. Med. Virol. 2022;94:1825–1832. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27588. https://doi:10.1002/jmv.27588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fawazy N.G., Panda S.S., Mostafa A., Kariuki B.M., Bekheit M.S., Moatasim Y., Kutkat O., Fayad W., El-Manawaty M.A., Soliman A.A.F., El-Shiekh R.A., Srour A.M., Barghash R.F., Girgis A.S. Development of spiro-3-indolin-2-one containing compounds of antiproliferative and anti-SARS-CoV-2 properties. Sci. Rep. 2022;12 doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-17883-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krause R., Smolle J. Covid-19 mortality and local burden of infectious diseases: a worldwide country-by-country analysis. J. Infect. Public Health. 2022;15:1370–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2022.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buonaguro L., Tagliamonte M., Tornesello M.L., Buonaguro F.M. SARS-CoV-2 RNA polymerase as target for antiviral therapy. J. Transl. Med. 2020;18:185. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02355-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durmuş S., Ülgen K.Ö. Comparative interactomics for virus-human protein-protein interactions: DNA viruses versus RNA viruses. FEBS Open Bio. 2017;7:96–107. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12167. https://doi:10.1002/2211-5463.12167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu W., Chen C.Z., Gorshkov K., Xu M., Lo D.C., Zheng W. RNA-dependent RNA polymerase as a target for COVID-19 drug discovery. SLAS Discovery. 2020;25:1141–1151. doi: 10.1177/24725552209421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banerjee R., Perera L., Tillekeratne L.M.V. Potential SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. Drug Discov. Today. 2021;26:804–816. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2020.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ullrich S., Nitsche C. The SARS-CoV-2 main protease as drug target. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2020;30 doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2020.127377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elmezayen A.D., Al-Obaidi A., Şahin A.T., Yelekçi K. Drug repurposing for coronavirus (COVID-19): in silico screening of known drugs against coronavirus 3CL hydrolase and protease enzymes. J. Biomol. Struct. Dynam. 2021;39:2980–2992. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1758791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao Y., Yan L., Huang Y., Liu F., Zhao Y., Cao L., Wang T., Sun Q., Ming Z., Zhang L., Ge J., Zheng L., Zhang Y., Wang H., Zhu Y., Zhu C., Hu T., Hua T., Zhang B., Yang X., Li J., Yang H., Liu Z., Xu W., Guddat L.W., Wang Q., Lou Z., Rao Z. Structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from COVID-19 virus. Science. 2020;368:779–782. doi: 10.1126/science.abb7498. https://doi:10.1126/science.abb7498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seliem I.A., Girgis A.S., Moatasim Y., Kandeil A., Mostafa A., Ali M.A., Bekheit M.S., Panda S.S. New pyrazine conjugates: synthesis, computational studies, and antiviral properties against SARS-CoV-2. ChemMedChem. 2021;16:3418–3427. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202100476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu X., Chen Y., Lu X., Zhang W., Fang W., Yuan L., Wang X. An update on inhibitors targeting RNA-dependent RNA polymerase for COVID-19 treatment: promises and challenges. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2022;205 doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2022.115279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tian L., Qiang T., Liang C., Ren X., Jia M., Zhang J., Li J., Wan M., Wen X.Y., Li H., Cao W., Liu H. RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) inhibitors: the current landscape and repurposing for the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021;213 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zandi K., Musall K., Oo A., Cao D., Liang B., Hassandarvish P., Lan S., Slack R.L., Kirby K.A., Bassit L., Amblard F., Kim B., AbuBakar S., Sarafianos S.G., Schinazi R.F. Baicalein and baicalin inhibit SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent-RNA polymerase. Microorganisms. 2021;9:893. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9050893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Almeida S.M.V., Soares J.C.S., dos Santos K.L., Alves J.E.F., Ribeiro A.G., Jacob I.T.T., Ferreira C.J.d.S., dos Santos J.C., de Oliveira J.F., de Carvalho Junior L.B., de Lima M.d.C.A. COVID-19 therapy: what weapons do we bring into battle? Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020;28 doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu C., Liu Y., Yang Y., Zhang P., Zhong W., Wang Y., Wang Q., Xu Y., Li M., Li X., Zheng M., Chen L., Li H. Analysis of therapeutic targets for SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of potential drugs by computational methods. Acta Pharm. Sinica B10. 2020:766–788. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gil C., Martinez A. Is drug repurposing really the future of drug discovery or is new innovation truly the way forward? Expet Opin. Drug Discov. 2021;16:829–831. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2021.1912733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez M.A. Efficacy of repurposed antiviral drugs: lessons from COVID-19. Drug Discov. Today. 2022;27:1954–1960. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2022.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao X., Jing X., Wang J., Zheng Y., Qiu Y., Ji H., Peng L., Jiang S., Wu W., Guo D. Safety considerations of chloroquine in the treatment of patients with diabetes and COVID-19. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022;361 doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2022.109954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cortegiani A., Ingoglia G., Ippolito M., Giarratano A., Einav S. A systematic review on the efficacy and safety of chloroquine for the treatment of COVID-19. J. Crit. Care. 2020;57:279–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin W., Mao C., Luan X., Shen D.-D., Shen Q., Su H., Wang X., Zhou F., Zhao W., Gao M., Chang S., Xie Y.-C., Tian G., Jiang H.-W., Tao S.-C., Shen J., Jiang Y., Jiang H., Xu Y., Zhang S., Zhang Y., Xu H.E. Structural basis for inhibition of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from SARS-CoV-2 by remdesivir. Science. 2020;368:1499–1504. doi: 10.1126/science.abc1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.https://www.drugs.com/history/veklury.html (accessed on Dec. 7, 2022)

- 34.Lamb Y.N. Remdesivir: first approval. Drugs. 2020;80:1355–1363. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01378-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warren T.K., Jordan R., Lo M.K., Ray A.S., Mackman R.L., Soloveva V., Siegel D., Perron M., Bannister R., Hui H.C., Larson N., Strickley R., Wells J., Stuthman K.S., Van Tongeren S.A., Garza N.L., Donnelly G., Shurtleff A.C., Retterer C.J., Gharaibeh D., Zamani R., Kenny T., Eaton B.P., Grimes E., Welch L.S., Gomba L., Wilhelmsen C.L., Nichols D.K., Nuss J.E., Nagle E.R., Kugelman J.R., Palacios G., Doerffler E., Neville S., Carra E., Clarke M.O., Zhang L., Lew W., Ross B., Wang Q., Chun K., Wolfe L., Babusis D., Park Y., Stray K.M., Trancheva I., Feng J.Y., Barauskas O., Xu Y., Wong P., Braun M.R., Flint M., McMullan L.K., Chen S.-S., Fearns R., Swaminathan S., Mayers D.L., Spiropoulou C.F., Lee W.A., Nichol S.T., Cihlar T., Bavari S. Therapeutic efficacy of the small molecule GS-5734 against Ebola virus in rhesus monkeys. Nature. 2016;531:381–385. doi: 10.1038/nature17180. https://doi:10.1038/nature17180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lo M.K., Jordan R., Arvey A., Sudhamsu J., Shrivastava-Ranjan P., Hotard A.L., Flint M., McMullan L.K., Siegel D., Clarke M.O., Mackman R.L., Hui H.C., Perron M., Ray A.S., Cihlar T., Nichol S.T., Spiropoulou C.F. GS-5734 and its parent nucleoside analog inhibit Filo-, Pneumo-, and Paramyxoviruses. Sci. Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/srep43395. https://doi:10.1038/srep43395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheahan T.P., Sims A.C., Graham R.L., Menachery V.D., Gralinski L.E., Case J.B., Leist S.R., Pyrc K., Feng J.Y., Trantcheva I., Bannister R., Park Y., Babusis D., Clarke M.O., Mackman R.L., Spahn J.E., Palmiotti C.A., Siegel D., Ray A.S., Cihlar T., Jordan R., Denison M.R., Baric R.S. Broad-spectrum antiviral GS-5734 inhibits both epidemic and zoonotic coronaviruses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9(396):eaal3653. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal3653. https://doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aal3653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown A.J., Won J.J., Graham R.L., Dinnon K.H., III, Sims A.C., Feng J.Y., Cihlar T., Denison M.R., Baric R.S., Sheahan T.P. Broad spectrum antiviral remdesivir inhibits human endemic and zoonotic deltacoronaviruses with a highly divergent RNA dependent RNA polymerase. Antivir. Res. 2019;169 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2019.104541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferner R.E., Aronson J.K. Remdesivir in covid-19, A drug with potential-don’t waste time on uncontrolled observations. BMJ. 2020;369:m1610. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1610. https://doi:10.1136/bmj.m1610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cardile A.P., Warren T.K., Martins K.A., Reisler R.B., Bavari S. Will there Be a cure for Ebola? Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2017;57:329–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010716-105055. https://doi:10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010716-105055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang M., Cao R., Zhang L., Yang X., Liu J., Xu M., Shi Z., Hu Z., Zhong W., Xiao G. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hughes S., Troise O., Donaldson H., Mughal N., Moore L.S.P. Bacterialand fungal coinfection among hospitalized patients with COVID-19: aretro- spective cohortstudy in a UKsecondary-care setting. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020;26:1395–1399. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wen W.D., Chen Q., Shi W.Q., Deng C., Shi Y., Tang W., Chen K., Wu X., Dai M.X., Tang Y.J. 5 June 2020. Deuterium A Nucleoside Analogue and Preparation Method and Use Thereof. CN111233929A. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qian H.-j., Wang Y., Zhang M.-q., Xie Y.-c., Wu Q.-q., Liang L.-y., Cao Y., Duan H.-q., Tian G.-h., Ma J., Zhang Z.-b., Li N., Jia J.-y., Zhang J., Aisa H.A., Shen J.-s., Yu C., Jiang H.-l., Zhang W.-h., Wang Z., Liu G.-y. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of VV116, an oral nucleoside analog against SARS-CoV-2, in Chinese healthy subjects. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2022:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41401-022-00895-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xie Y., Yin W., Zhang Y., Shang W., Wang Z., Luan X., Tian G., Aisa H.A., Xu Y., Xiao G., Li J., Jiang H., Zhang S., Zhang L., Xu H.E., Shen J. Design and development of an oral remdesivir derivative VV116 against SARS-CoV-2. Cell Res. 2021;31:1212–1214. doi: 10.1038/s41422-021-00570-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shen Y., Ai J., Lin N., Zhang H., Li Y., Wang H., Wang S., Wang Z., Li T., Sun F., Fan Z., Li L., Lu Y., Meng X., Xiao H., Hu H., Ling Y., Li F., Li H., Xi C., Gu L., Zhang W., Fan X. An open, prospective cohort study of VV116 in Chinese participants infected with SARS-CoV-2 omicron variants. Emerg. Microb. Infect. 2022;11:1518–1523. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2078230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cox R.M., Wolf J.D., Lieber C.M., Sourimant J., Lin M.J., Babusis D., DuPont V., Chan J., Barrett K.T., Lye D., Kalla R., Chun K., Mackman R.L., Ye C., Cihlar T., Martinez-Sobrido L., Greninger A.L., Bilello J.P., Plemper R.K. Oral prodrug of remdesivir parent GS-441524 is efficacious against SARS-CoV-2 in ferrets. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:6415. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26760-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Furuta Y., Komeno T., Nakamura T. Favipiravir (T-705), a broad spectrum inhibitor of viral RNA polymerase. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B. 2017;93:449–463. doi: 10.2183/pjab.93.027. https://doi:10.2183/pjab.93.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shiraki K., Daikoku T. Favipiravir, an anti-influenza drug against life-threatening RNA virus infections. Pharmacol. Therapeut. 2020;209 doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gatherer D. The 2014 Ebola virus disease outbreak in West Africa. J. General Virol. 2014;95:1619–1624. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.067199-0. https://doi:10.1099/vir.0.067199-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reddy O.S., Lai W.-F. Tackling COVID-19 using Remdesivir and Favipiravir as therapeutic options. Chembiochem. 2021;22:939–948. doi: 10.1002/cbic.202000595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dauby N., Van Praet S., Vanhomwegen C., Veliziotis I., Konopnicki D., Roman A. Tolerability of favipiravir therapy in critically ill patients with COVID‐19: a report of four cases. J. Med. Virol. 2021;93:689–691. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26488. https://doi:10.1002/jmv.26488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Udwadia Z.F., Singh P., Barkate Ha, Patil S., Rangwala S., Pendse A., Kadam J., Wu W., Caracta C.F., Tandon M. Efficacy and safety of favipiravir, an oral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor, in mild-to-moderate COVID-19: a randomized, comparative, open-label, multicenter, phase 3 clinical trial. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;103:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naydenova K., Muir K.W., Wu L.-F., Zhang Z., Coscia F., Peet M.J., Castro-Hartmann P., Qian P., Sader K., Dent K., Kimanius D., Sutherland J.D., Löwe J., Barford D., Russo C.J. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in the presence of favipiravir-RTP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2021946118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vicenti I., Zazzi M., Saladini F. SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase as a therapeutic target for COVID-19. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2021;31:325–337. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2021.1880568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pourkarim F., Pourtaghi-Anvarian S., Rezaee H. Molnupiravir: a new candidate for COVID-19 treatment. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2022;10 doi: 10.1002/prp2.909. https://doi:10.1002/prp2.909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wahl A., Gralinski L.E., Johnson C.E., Yao W., Kovarova M., Dinnon K.H., II, Liu H., Madden V.J., Krzystek H.M., De C., White K.K., Gully K., Schäfer A., Zaman T., Leist S.R., Grant P.O., Bluemling Gr R., Kolykhalov A.A., Natchus M.G., Askin F.B., Painter G., Browne E.P., Jones C.D., Pickles R.J., Baric R.S., Garcia J.V. SARS-CoV-2 infection is effectively treated and prevented by EIDD-2801. Nature. 2021;591:451–457. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03312-w. https://doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03312-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bernal A.J., Gomes da Silva M.M., Musungaie D.B., Kovalchuk E., Gonzalez A., Reyes V.D., Martin-Quiros A., Caraco Y., Williams-Diaz A., Brown M.L., Du J., Pedley A., Assaid C., Strizki J., Grobler J.A., Shamsuddin H.H., Tipping R., Wan H., Paschke A., Butterton J.R., Johnson M.G., De Anda C. Molnupiravir for oral treatment of Covid-19 in nonhospitalized patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022;386:509–520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116044. https://doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2116044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Parums D.V. Editorial: current status of oral antiviral drug treatments for SARS-CoV-2 infection in non-hospitalized patients. Med. Sci. Mon. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2022;28 doi: 10.12659/MSM.935952. https://doi:10.12659/MSM.935952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Urakova N., Kuznetsova V., Crossman D.K., Sokratian A., Guthrie Da B., Kolykhalov A.A., Lockwood M.A., Natchus M.G., Crowley M.R., Painter G.R., Frolova E.I., Frolov I. β-D-N4-Hydroxycytidine is a potent anti-alphavirus compound that induces a high level of mutations in the viral genome. J. Virol. 2018;92 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01965-17. e01965-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Painter W.P., Holman W., Bush J.A., Almazedi F., Malik H., Eraut N.C.J.E., Morin M.J., Szewczyk L.J., Painter G.R. Human safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of Molnupiravir, a novel broad-spectrum oral antiviral agent with activity against SARS-CoV-2. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021;65 doi: 10.1128/AAC.02428-20. e02428-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li P., Wang Y., Lavrijsen M., Lamers M.M., de Vries A.C., Rottier R.J., Bruno M.J., Peppelenbosch M.P., Haagmans B.L., Pan Q. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant is highly sensitive to molnupiravir, nirmatrelvir, and the combination. Cell Res. 2022;32:322–324. doi: 10.1038/s41422-022-00618-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Julander J.G., Siddharthan V., Evans J., Taylor R., Tolbert K., Apuli C., Stewart J., Collins P., Gebre M., Neilson S., Van Wettere A., Lee Y.-M., Sheridan W.P., Morrey J.D., Babu Y.S. Efficacy of the broad-spectrum antiviral compound BCX4430 against Zika virus in cell culture and in a mouse model. Antivir. Res. 2017;137:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.11.003. https://doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taylor R., Kotian P., Warren T., Panchal R., Bavari S., Julander J., Dobo S., Rose A., El-Kattan Y., Taubenheim B., Babu Y., Sheridan W.P. BCX4430 ‒ A broad-spectrum antiviral adenosine nucleoside analog under development for the treatment of Ebola virus disease. J. Inf. Public Health. 2016;9:220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taylor R., Bowen R., Demarest J.F., DeSpirito M., Hartwig A., Bielefeldt-Ohmann H., Walling D.M., Mathis A., Babu Y.S. Activity of Galidesivir in a hamster model of SARS-CoV-2. Viruses. 2022;14:8. doi: 10.3390/v14010008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Warren T.K., Wells J., Panchal R.G., Stuthman K.S., Garza N.L., Van Tongeren S.A., Dong L., Retterer C.J., Eaton B.P., Pegoraro G., Honnold S., Bantia S., Kotian P., Chen X., Taubenheim B.R., Welch L.S., Minning D.M., Babu Y.S., Sheridan W.P., Bavari S. Protection against filovirus diseases by a novel broad-spectrum nucleoside analogue BCX4430. Nature. 2014;508:402–405. doi: 10.1038/nature13027. https://doi:10.1038/nature13027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sidwell R.W., Huffman J.H., Khare G.P., Allen L.B., Witkowski J.T., Robins R.K. Broad-spectrum antiviral activity of Virazole: 1-beta-D-ribofuranosyl-1,2,4- triazole-3-carboxamide. Science. 1972;177:705–706. doi: 10.1126/science.177.4050.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Elfiky A.A. SARS-CoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) targeting: an in silico perspective. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021;39:3204–3212. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1761882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Elfiky A.A. Anti-HCV, nucleotide inhibitors, repurposing against COVID-19. Life Sci. 2020;248 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xu Y., Li M., Zhou L., Liu D., He W., Liang W., Sun Q., Sun H., Li Y., Liu X. Ribavirin treatment for critically Ill COVID-19 patients: an observational study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021;14:5287–5291. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S330743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hung I.F.-N., Lung K.-C., Tso E.Y.-K., Liu R., Chung T.W.-H., Chu M.-Y., Ng Y.-Y., Lo J., Chan J., Tam An R., Shum H.-P., Chan V., Wu A.K.-L., Sin K.-M., Leung W.-S., Law W.-L., Lung D.C., Sin S., Yeung P., Yip C.C.-Y., Zhang R.R., Fung Ag Y.-F., Yan E.Y.-W., Leung K.-H., Ip J.D., Chu A.W.-H., Chan W.-M., Ng An C.-K., Lee R., Fung K., Yeung A., Wu T.-C., Chan J.W.-M., Yan W.-W., Chan W.-M., Chan J.F.-W., Lie A.K.-W., Tsang O.T.-Y., Cheng V.C.-C., Que T.-L., Lau C.-S., Chan K.-H., To K.K.-W., Yuen K.-Y. Triple combination of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir–ritonavir, and ribavirin in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1695–1704. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brochot E., Castelain S., Duverlie G., Capron D., Nguyen-Khac E., François C. Ribavirin monitoring in chronic hepatitis C therapy: anaemia versus efficacy. Antivir. Ther. 2010;15:687–695. doi: 10.3851/IMP1609. https://doi:10.3851/IMP1609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Crotty S., Maag D., Arnold J.J., Zhong W., Lau J.Y.N., Hong Z., Andino R., Cameron C.E. The broad-spectrum antiviral ribonucleoside ribavirin is an RNA virus mutagen. Nat. Med. 2000;6:1375–1379. doi: 10.1038/82191. https://doi:10.1038/82191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sacramento C.Q., Fintelman-Rodrigues N., Temerozo J.R., Da Silva A.d.P.D., Gomes Dias S.d.S., da Silva C.d.S., Ferreira A.C., Mattos M., Pão C.R.R., de Freitas C.S., Soares V.C., Hoelz L.V.B., Fernandes T.V.A., Branco F.S.C., Bastos M.M., Boechat N., Saraiva F.B., Ferreira M.A., Jockusch S., Wang X., Tao C., Chien M., Xie W., Patel D., Garzia A., Tuschl T., Russo J.J., Rajoli R.K.R., Pedrosa C.S.G., Vitória G., Souza L.R.Q., Goto-Silva L., Guimarães M.Z., Rehen S.K., Owen A., Bozza F.A., Bou-Habib D.C., Ju J., Bozza P.T., Souza T.M.L. In vitro antiviral activity of the anti-HCV drugs daclatasvir and sofosbuvir against SARS-CoV-2, the aetiological agent of COVID-19. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021;76:1874–1885. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkab072. https://doi:10.1093/jac/dkab072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heo Y.-A., Deeks E.D. Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir/Voxilaprevir: A Review in chronic hepatitis C, Drugs. 2018;78:577–587. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0895-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smith M.A., Regal R.E., Mohammad R.A. Daclatasvir: a NS5A replication complex inhibitor for hepatitis C infection. Ann. Pharm. (Poznan) 2016;50:39–46. doi: 10.1177/1060028015610342. https://doi:10.1177/1060028015610342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sadeghi A., Asgari A.A., Norouzi A., Kheiri Z., Anushirvani A., Montazeri M., Hosamirudsai H., Afhami S., Akbarpour E., Aliannejad R., Radmard A.R., Davarpanah A.H., Levi J., Wentzel H., Qavi A., Garratt A., Simmons B., Hill A., Merat S. Sofosbuvir and daclatasvir compared with standard of care in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with moderate or severe coronavirus infection (COVID-19): a randomized controlled trial. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020;75:3379–3385. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa334. https://doi:10.1093/jac/dkaa334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ju J., Li X., Kumar S., Jockusch S., Chien M., Tao C., Morozova I., Kalachikov S., Kirchdoerfer R.N., Russo J.J. Nucleotide analogues as inhibitors of SARS-CoV polymerase. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2020 doi: 10.1002/prp2.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.De Clercq E. Tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) as the successor of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) Biochem. Pharmacol. 2016;119:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.04.015. https://doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2016.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lou L. Advances in nucleotide antiviral development from scientific discovery to clinical applications: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for hepatitis B. J. Clin. Transl. Hepatol. 2013;1:33–38. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2013.004XX. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Feng J.Y., Du Pont V., Babusis D., Gordon C.J., Tchesnokov E.P., Perry J.K., Duong V., Vijjapurapu A., Zhao X., Chan J., Cohen C., Juneja K., Cihlar T., Götte M., Bilello J.P. The nucleoside/nucleotide analogs Tenofovir and Emtricitabine are inactive against SARS-CoV-2. Molecules. 2022;27:4212. doi: 10.3390/molecules27134212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zanella I., Zizioli D., Castelli F., Quiros-Roldan E. Tenofovir, another inexpensive, well-known and widely available old drug repurposed for SARS-COV-2 infection. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14:454. doi: 10.3390/ph14050454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Elfiky A.A. Ribavirin, remdesivir, sofosbuvir, Galidesivir, and tenofovir against SARSCoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp): a molecular docking study. Life Sci. 2020;253 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Good S.S., Westover J., Jung K.H., Zhou X.-J., Moussa A., La Colla P., Collu G., Canard B., Sommadossi J.-P. AT-527, a Double prodrug of a guanosine nucleotide analog, is a potent inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro and a promising oral antiviral for treatment of COVID-19. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021;65 doi: 10.1128/AAC.02479-20. e02479-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Han Y.J., Lee K.H., Yoon S., Nam S.W., Ryu S., Seong D., Kim J.S., Lee J.Y., Yang J.W., Lee J., Koyanagi A., Hong S.H., Dragioti E., Radua J., Smith L., Oh H., Abou Ghayda R., Kronbichler A., Effenberger M., Kresse D., Denicolò S., Kang W., Jacob L., Shin H., Shin J.I. Treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a systematic review of in vitro, in vivo, and clinical trials. Theranostics. 2021;11:1207–1231. doi: 10.7150/thno.48342. https://doi:10.7150/thno.48342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shannon A., Fattorini V., Sama B., Selisko B., Feracci M., Falcou C., Gauffre P., El Kazzi P., Delpal A., Decroly E., Alvarez K., Eydoux C., Guillemot J.-C., Moussa A., Good S.S., La Colla P., Lin K., Sommadossi J.-P., Zhu Y., Yan X., Shi H., Ferron F., Canard B. A dual mechanism of action of AT-527 against SARS-CoV-2 polymerase. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:621. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28113-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Khater S., Kumar P., Dasgupta N., Das G., Ray S., Prakash A. Combining SARS-CoV-2 proofreading exonuclease and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitors as a strategy to combat COVID-19: a high-throughput in silico screening. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.647693. https://doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.647693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rabie A.M., Abdalla M. Forodesine and Riboprine exhibit strong anti-SARS-CoV-2 repurposing potential: In silico and in vitro studies. ACS Bio. Med. Chem. 2022 doi: 10.1021/acsbiomedchemau.2c00039. Au (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Newman D.J., Cragg G.M. Natural products as sources of new drugs from 1981 to 2014. J. Nat. Prod. 2016;79:629–661. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01055. https://doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.De Clercq E., Li G. Approved antiviral drugs over the past 50 years. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2016;29:695i747. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00102-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Girgis A.S., D'Arcy P., Aboshouk D.R., Bekheit M.S. Synthesis and bio-properties of 4-piperidone containing compounds as curcumin mimics. RSC Adv. 2022;12:31102–31123. doi: 10.1039/d2ra05518j. http://doi:10.1039/d2ra05518j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nelson K.M., Dahlin J.L., Bisson J., Graham Ja, Pauli G.F., Walters M.A. The essential medicinal chemistry of curcumin. J. Med. Chem. 2017;60:1620–1637. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00975. http://doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chakravarti R., Singh R., Ghosh A., Dey D., Sharma P., Velayutham R., Roy S., Ghosh D. A review on potential of natural products in the management of COVID-19. RSC Adv. 2021;11:16711–16735. doi: 10.1039/d1ra00644d. http://doi:10.1039/d1ra00644d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Thomas E., Stewart L.E., Darley B.A., Pham A.M., Esteban I., Panda S.S. Plant-based natural products and extracts: potential source to develop new antiviral drug candidates. Molecules. 2021;26:6197. doi: 10.3390/molecules26206197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Owen L., Laird K., Shivkumar M. Antiviral plant-derived natural products to combat RNA viruses: targets throughout the viral life cycle. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2021;75:476–499. doi: 10.1111/lam.13637. http://doi:10.1111/lam.13637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mani J.S., Johnson J.B., Steel J.C., Broszczak D.A., Neilsen P.M., Walsh K.B., Naiker M. Natural product-derived phytochemicals as potential agents against coronaviruses: a review. Virus Res. 2020;284 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.197989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Solnier J., Fladerer J.-P. Flavonoids: a complementary approach to conventional therapy of COVID-19? Phytochemistry Rev. 2021;20:773–795. doi: 10.1007/s11101-020-09720-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Limanaqi F., Busceti C.L., Biagioni F., Lazzeri G., Forte M., Schiavon S., Sciarretta S., Frati G., Fornai F. Cell clearing systems as targets of polyphenols in viral infections: potential implications for COVID-19 pathogenesis. Antioxidants. 2020;9:1105. doi: 10.3390/antiox9111105. https://doi:10.3390/antiox9111105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zandi K., Musall K., Oo A., Cao D., Liang B., Hassandarvish P., Lan S., Slack R.L., Kirby K.A., Bassit L., Amblard F., Kim B., AbuBakar S., Sarafianos S.G., Schinazi R.F. Baicalein and baicalin inhibit SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent-RNA polymerase. Microorganisms. 2021;9:893. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9050893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Raj V., Lee J.-H., Shim J.-J., Lee J. Antiviral activities of 4H-chromen-4-one scaffold-containing flavonoids against SARS–CoV–2 using computational and in vitro approaches. J. Mol. Liquids. 2022;353 doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2022.118775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.da Silva F.M.A., da Silva K.P.A., de Oliveira L.P.M., Costa E.V., Koolen H.H.F., Pinheiro M.L.B., de Souza A.Q.L., de Souza A.D.L. Flavonoid glycosides and their putative human metabolites as potential inhibitors of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz, Rio de Janeiro. 2020;115 doi: 10.1590/0074-02760200207. https://doi:10.1590/0074-02760200207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Goyal R.K., Majeed J., Tonk R., Dhobi M., Patel B., Sharma K., Apparsundaram S. Current targets and drug candidates for prevention and treatment of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020;21:365–384. doi: 10.31083/j.rcm.2020.03.118. https://doi:10.31083/j.rcm.2020.03.118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Shaldam M.A., Yahya G., Mohamed N.H., Abdel-Daim M.M., Al Naggar Y. In silico screening of potent bioactive compounds from honeybee products against COVID-19 target enzymes. Env. Sci. Poll. Research. 2021;28:40507–40514. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-14195-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yang Z.-F., Bai L.-P., Huang W.-b., Li X.-Z., Zhao S.-S., Zhong N.-S., Jiang Z.-H. Comparison of in vitro antiviral activity of tea polyphenols against influenza A and B viruses and structure‒activity relationship analysis. Fitoterapia. 2014;93:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chowdhury P., Sahuc M.-E., Rouillé Y., Rivière C., Bonneau N., Vandeputte A., Brodin P., Goswami M., Bandyopadhyay T., Dubuisson J., Séron K. Theaflavins, polyphenols of black tea, inhibit entry of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lung J., Lin Y.‐S., Yang Y.‐H., Chou Y.‐L., Shu L.‐H., Cheng Y.‐C., Liu H.T., Wu C.‐Y. The potential chemical structure of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA‐dependent RNA polymerase. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:693–697. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25761. https://doi:10.1002/jmv.25761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Koulgi S., Jani V., Uppuladinne V M., Sonavane N.U., Joshi R. Natural plant products as potential inhibitors of RNA dependent RNA polymerase of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Osafo N., Mensah K.B., Kofi Yeboah O. Phytochemical and pharmacological review of Cryptolepis sanguinolenta (lindl.) schlechter, hindawi. Adv. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2017;3026370 doi: 10.1155/2017/3026370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Borquaye L.S., Gasu E.N., Ampomah G.B., Kyei L.K., Amarh M.A., Mensah C.N., Nartey D., Commodore M., Adomako A.K., Acheampong P., Mensah J.O., Mormor D.B., Aboagye C.I. Alkaloids from Cryptolepis sanguinolenta as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins: an in silico study. Hindawi BioMed. Res. Intern. 2020;5324560 doi: 10.1155/2020/5324560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pendyalaa B., Patras A. 2020. In Silico Screening of Food Bioactive Compounds to Predict Potential Inhibitors of COVID-19 Main Protease (Mpro) and RNA-dependent RNA Polymerase (RdRp)https://doi:10.26434/chemrxiv.12051927.v2 ChemRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jang M.G., Oh J.M., Ko H.C., Kim J.-W., Baek S., Jin Y.J., Hur S.-P., Kim S.-J. Clerodendrum trichotomum extract improves metabolic derangements in high fructose diet-fed rats. Anim. Cell Syst. 2021;25:396–404. doi: 10.1080/19768354.2021.2004221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]