Abstract

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to determine the demographics and perceptions of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) in the field of dermatopathology to provide a measurable baseline for future efforts to enhance equity measures within our subspecialty.

Methods:

A questionnaire based on a previously validated instrument by Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) was sent to American Society of Dermatopathology (ASDP) members to collect the demographic information (gender, race, sexual orientation, disability, experience and practice setting, etc) and evaluate 8 diversity, engagement, and inclusivity statements on a 1–5 Likert scale.

Results:

The demographics of 207/1331 (15%) respondents showed slight male predominance. Eleven percent of respondents identified as LGBTQI. The major racial distribution was comprised of 62% White, 18% Asian (including Middle Eastern/Indian), 10% Hispanic and 4% Black respondents. New-in-practice respondents (those in practice - 5 years or less) were more likely to have a pathology background (71% vs 56%, p = 0.047) than their more-established peers with more than 5 years of service. This trend also contributed to increased diversity in terms of gender (66% females) and race (48% non-White) among the newer generation. Dermatology-trained dermatopathologists were mostly White (70%) and male (53%). Analysis of respondent demographics with perception statements showed that White and U.S. graduate respondents (compared to other groups) were more likely to have a positive perception about DEI within the field of dermatopathology.

Conclusions:

The results provide a snapshot of the current state of diversity within the field of dermatopathology. Moreover, these results highlight opportunities for further increasing diversity in general and leadership in particular within dermatopathology.

Keywords: diversity, equity, inclusion, dermatopathology, dermatology, pathology

INTRODUCTION:

With the changing demographic landscape of the United States1, compounded by societal inequities highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic2, measures to support diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) in medicine are pivotal to tackle disparities that also exist in healthcare.3 Increasing racial/ethnic diversity, introducing underrepresented groups and advancing health equity in medicine can lead to increased productivity and improved quality of scholarly activity through inclusive policies.4 Unfortunately, current demographics in medicine still do not represent the general population, and the skewed demographics are the remnants of historic discrimination and structural racism in the United States that still persist.5

Understanding current perceptions regarding diversity within various specialties may help establish how best to address and implement needed change.6 Dermatopathology being pooled by dermatology and pathology is also more likely to harbor demographic distributions that are different than the parent specialties. The aim of this study was to survey the current self-identified demographic distribution in the field of dermatopathology and also determine the subjective perceptions of DEI and challenges in our specialty. Establishing the current diversity level (or lack thereof) will provide a measurable baseline for subsequent efforts to increase DEI within the subspecialty.

METHODS:

The study was approved by Institutional Review Board and proposed to the board members of the American Society of Dermatopathology (ASDP) to use listserv of the society’s members (including practicing and in-training dermatopathologists) as study participants. A questionnaire based on a previously validated instrument by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC)7 was approved by the ASDP board and sent to ASDP members in April 2021 via email link. This optional questionnaire collected demographic and professional background (gender, race, sexual orientation, veteran status, disability, experience and practice setting) information. It also asked respondents to evaluate 8 perception statements/questions regarding DEI (Appendix A) on a 1–5 Likert scale. The responses were collected anonymously on a departmental SurveyMonkey (Momentive Inc, San Mateo, CA) account. A reminder email was sent one month after the first dispatch and the questionnaire was closed one week after the reminder email.

The questionnaire utilized similar demographics and diversity questions based on the already validated Diversity Engagement Survey Instrument6 designed by AAMC and was developed in consultation with the DEI officer (BG) at our institution to maximize inclusivity and to minimize potential bias in response to the questions. The content/construct validity and internal consistency of relevant diversity questions are the same as the initial AAMC survey. The data was transferred from Survey Monkey and an extensive exploratory data analysis was conducted using R software (R Core Team 2022, Vienna, Austria). Univariate analyses were performed on demographics, professional background and questionnaire responses about diversity perceptions. To gain an insight into subjective perceptions of diversity in dermatopathology, the numerical values of overall respondent-level perception were averaged for each of the 8 Likert-scaled statements. An average value close to 1 corresponded to negative perceptions, while an average near 5 corresponded to positive perceptions. Among our 8 Likert items, statements 1, 4 and 6 were related to diversity, statements 3, 5 and 7 were related to inclusion, and statements 2 and 8 were related to engagement or opportunity7. As such, average scores for these categories were also created. Exploratory factor analysis was utilized to test the reasonableness of subdividing the Likert items into these aggregated categories: diversity, inclusion and engagement. In all but 1 of the 8 statements on DEI, responses of ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’ correspond to positive perceptions by the respondents. For analysis and interpretability purposes, the statement “The dermatopathology community has a diversity problem” was re-worded to be “The dermatopathology community does not have a diversity problem”, and the responses to this item were flipped. This allows for each of the 8 DEI statements to be interpreted in the same direction.

To evaluate the strength of the relationships between demographic and professional background characteristics of respondents, contingency tables were constructed and chi-square (or, in the case of low observed counts, Fisher’s exact) tests were employed. Spearman correlations and factor analysis were utilized to examine the associations between and the dimensionality of the responses to the 8 Likert-scale items, respectively. The relationships between the responses to the Likert-scale items (as well as their aggregates) and respondent characteristics were assessed via Wilcoxon rank sum (or, for more than two categories, Kruskal-Wallis) tests.

RESULTS:

Of the 1331 listserv ASDP members, there were a total of 207 (15.6% response rate) respondents. In all, there were 195 surveys in which respondents answered at least 5 of the 8 diversity statement items. As shown in Table 1, participants were slightly more likely to be male (49% vs 46%) than female, and were predominantly heterosexual (n = 166; 85%) and White (n = 121; 62%). Most did not report a disability (3.6%) or veteran status (6.2%). Respondents were more likely to be U.S. Medical school graduates (71% vs 25%), and they were more likely to have a residency background in pathology (58%) than dermatology (36%). A total of 7 respondents (3.6%) had residencies in both dermatology and pathology. Residents and Fellows made up a total of only 14% of respondents, while those reporting community or private practice (53%) outpaced those in academia (44%). More than 3 in 4 respondents had been in practice for more than 5 years (78%). There was a good balance of regional diversity among this group of dermatopathologists, with no region being represented by more than 24% of participants.

Table 1.

Demographic distribution of survey respondents

| Characteristic | N = 1951 |

|---|---|

| Gender / Gender Identity | |

| Female | 90 (46%) |

| Male | 96 (49%) |

| Non-binary | 1 (0.5%) |

| prefer not to answer | 6 (3.1%) |

| Transgender | 2 (1.0%) |

| Sexual Orientation | |

| heterosexual | 166 (85%) |

| gay | 12 (6.2%) |

| prefer not to answer | 8 (4.1%) |

| bisexual | 5 (2.6%) |

| lesbian | 2 (1.0%) |

| questioning | 2 (1.0%) |

| Race / Ethnicity | |

| Asian | 26 (13%) |

| Black or African American | 7 (3.6%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 19 (9.7%) |

| Middle Eastern or North African | 10 (5.1%) |

| Multiracial or Multiethnic | 5 (2.6%) |

| Native American or Alaska Native | 1 (0.5%) |

| prefer not to answer | 6 (3.1%) |

| White | 121 (62%) |

| Has Disability | |

| No | 183 (94%) |

| prefer not to answer | 5 (2.6%) |

| Yes | 7 (3.6%) |

| Is Veteran | |

| No | 178 (91%) |

| prefer not to answer | 5 (2.6%) |

| Yes | 12 (6.2%) |

| Medical School Location | |

| Non-U.S. Graduate | 49 (25%) |

| prefer not to answer | 7 (3.6%) |

| U.S. Graduate | 139 (71%) |

| Residency in Dermatology or Pathology | |

| both Dermatology and Pathology | 7 (3.6%) |

| Dermatology | 70 (36%) |

| Pathology | 113 (58%) |

| prefer not to answer | 5 (2.6%) |

| Current level of Training | |

| Resident | 15 (7.7%) |

| Dermatopathology Fellow | 12 (6.2%) |

| Board eligible/certified practicing dermatopathologist | 168 (86%) |

| Type of Practice | |

| Academic | 74 (44%) |

| Community/Private | 89 (53%) |

| prefer not to answer | 4 (2.4%) |

| Unknown | 28 |

| Years of Practice | |

| <1 year | 13 (7.9%) |

| 1–5 years | 23 (14%) |

| 6–10 years | 36 (22%) |

| >10 years | 93 (56%) |

| Unknown | 30 |

| Region | |

| Midwest | 47 (24%) |

| Mountain | 10 (5.1%) |

| NA | 0 (0%) |

| Northeast | 47 (24%) |

| Pacific | 22 (11%) |

| prefer not to answer | 14 (7.2%) |

| South | 32 (16%) |

| South Atlantic | 23 (12%) |

n (%)

Factor analysis was employed to better understand the underlying covariation of the Likert items and estimate its dimensionality. Solutions for 2 or 3 factors were examined using a varimax rotation of the factor loading matrix, and the 3-factor solution was preferred based on the eigenvalues of each factor, accounting for 63% of the total variation of the data. This analysis strongly suggests that these data can be divided into 3 categories. Specifically, the 3 diversity items (statements 1, 4 and 6) all loaded heavily onto the 2nd factor, while the other 5 items loaded primarily onto the 1st and 3rd factor. While the factor analysis does suggest that the inclusion and engagement / opportunity items produced similar responses and could possibly be combined, it does provide quantitative justification for subdividing the data into the 3 categories we have chosen to examine.

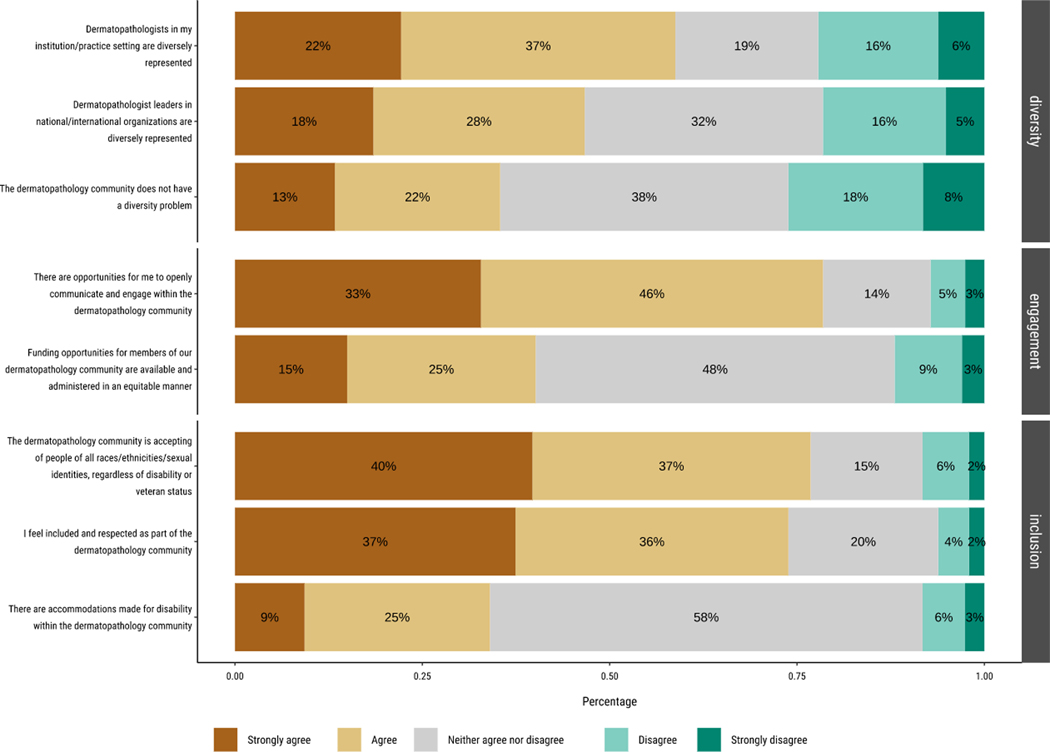

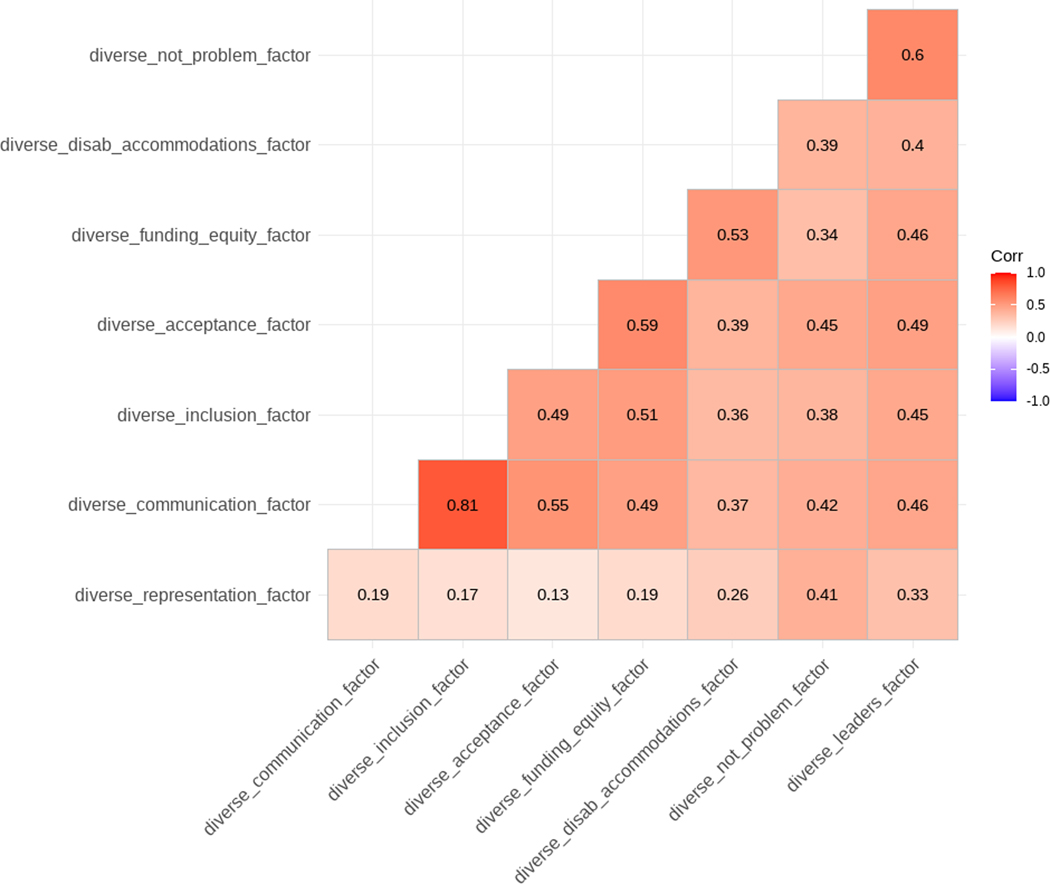

Univariate analyses of perception statements are shown in figure 1. The 3 items with the highest scores (>70% agree or strongly agree as shown by brown or yellow) were related to engagement (1) or inclusion (2). The 3 items with at least 20% of respondents answering disagree or strongly disagree were all related to diversity. On average, the aggregated diversity score was lower (mean = 3.35, sd = 0.91) than the (mean = 3.74, sd = 0.83) and inclusion (mean = 3.81, sd = 0.73) scores. Spearman correlations for perception statement responses showed that all item responses were positively correlated with one another, with correlations ranging from weak positive (0.13) to strong positive (0.81) (Appendix B).

Figure 1:

Analysis of perception statements, grouped into diversity, engagement and inclusion

Bivariate analyses of all participant characteristics with statistically significant associations showed that male respondents were more likely to be White (p=0.05) and were less likely to be in academia (p=0.02). White respondents were more likely to be US graduates (p<0.001) and more likely to be practicing more than 5 years (p=0.03). U.S. graduates were more likely to have completed dermatology residencies (p<0.001). Respondents with dermatology training were likely to be in academia (p<0.001) and to have more than 5 years in practice (p=0.013). New-in-practice respondents (those in practice - 5 years or less) were more likely to have a pathology background (71% vs 56%, p = 0.047) than their more-established peers with more than 5 years of service. In other words, those with less experience (<= 5 years exp) are increasingly non-male (56% vs 48%, NS), non-hetero (18% vs 13%, NS), non-white (48% vs 33%, p = 0.03), path background (71% vs 57%, p = 0.047). In addition, non-heterosexual respondents and non-U.S. graduate respondents were less likely to provide their region of practice.

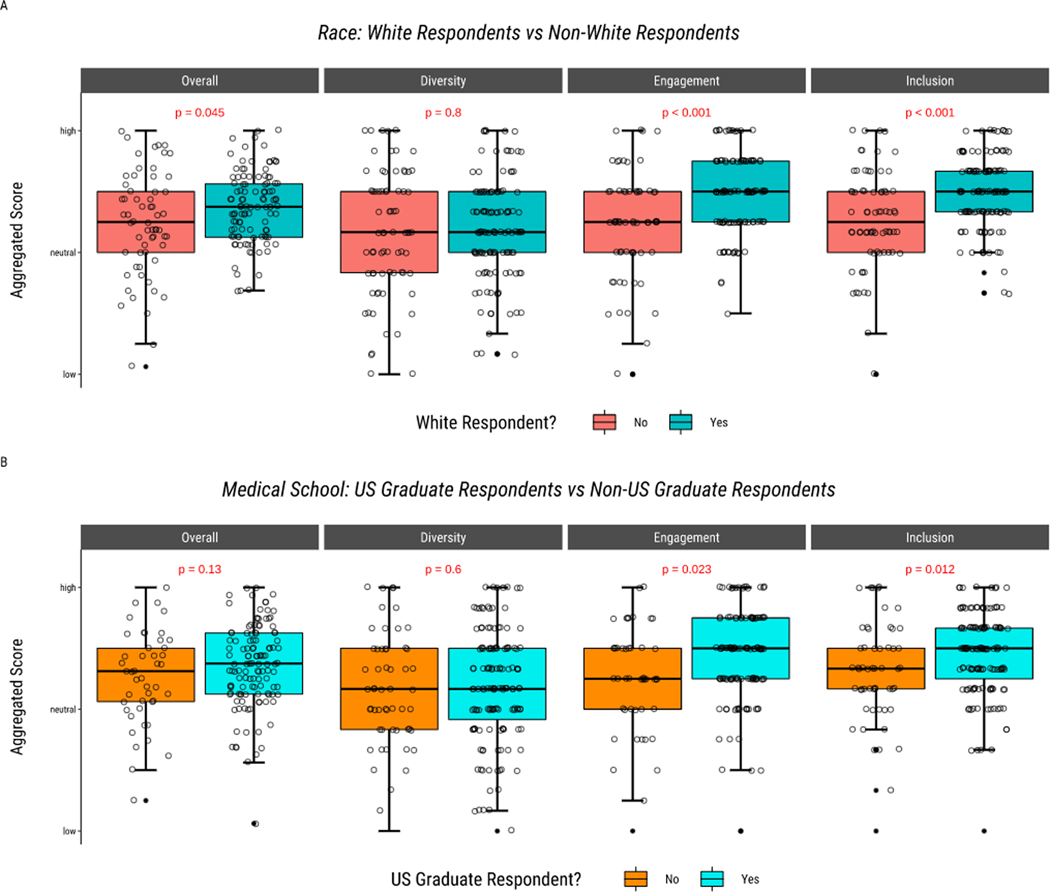

Bivariate associations of all combinations of participant characteristics versus all questionnaire items and aggregates were also analyzed. The most significant associations showed that White and US graduate respondents were more likely to have positive perceptions about diversity (and inclusion and engagement) within the dermatopathology community (figure 2).

Figure 2:

White and U.S graduates have more positive perceptions (for aggregates representing ‘Engagement’ and ‘Inclusion’).

Open comments from respondents are listed in table 2.

Table 2:

Open comments

| I think dermatopathology is one of the most diverse groups of people in the US and abroad. Just attend any ASDP meeting and it’s plain to see. I also think this “baseline” study is simply “woke” BS and no further time or money should be wasted on it! |

| Surveys such as this only allow and provide for the escalation of DIVISION in America. We should celebrate and encourage TALENT & ABILITY, period. |

| I am very ashamed that our society has lowered themselves to this political level. We are all created equal by our Creator. |

| This survey is long overdue. The lack of diversity in the field of dermatopathology needs to be addressed and cultural competency should be a priority. At the 2019 ASDP conference, a prominent and well known dermatopathologist was giving a talk and made an insensitive and racist comment about black people in South Africa. It is quite unfortunate that this was not addressed. I hope the ASDP will take the necessary steps to address the lack of diversity in dermatopathology. |

| I think the dermatopathology community shares the same problem that pathology and all of medicine shares, that it does not adequately represent black folks. |

| In my DP program we have had White, Asian, Arab, Indian and Black. |

| I am the only dermatopathologist in my (private) practice setting, so I am unable to answer some of the questions. I feel like any student who is interested in dermatopathology, works hard, and has a likeable personality has the opportunity to succeed in the field. |

| I would like to see funding from ASDP for meetings and other mentorship opportunities specifically for diverse students and residents interested in dermpath. |

| While I believe there are dermatopathologists of all races, I believe there is discrimination within the dermatopathology community based on training - with pathologists discriminated against and treated as inferior (compared to dermatologists). |

| In addition to the above, there is a gender bias and a “belonging to a white boys club” attitude that is all prevailing in the ASDP leaderships. |

| Who you know is more important than what you can actually do/contribute, sadly... |

| Tribalism and territorialism are the prevailing attitudes of leaders in our fields. How this field could grow and be so much more relevant than it is, if neurodiversity were embraced. |

| To an extent I can’t comment on the amount of diversity within the field as I am only aware of what I see and what is present, not what is absent. |

| How would anyone know the answer to his: “Funding opportunities for members of our dermatopathology community are available and administered in an equitable manner.” best case scenario, it is a feeling |

| Our society needs to have leadership and opportunities equitable for all. This representation should be apparent for all to see. There is an obvious lack of underrepresented groups serving critical and relevant roles within our society. |

| As a non US graduate, my chance of getting dermatopathology fellowship is diminished as the programs prefer white US graduates. |

| I feel that most people that are accepted into dermpath fellowships are Caucasian. I have applied to every program in the country and I only received 2 interviews and no offers. I love dermatopathology and I want to be a part of the dermpath community, but I am unable to gain access into the specialty because I am not Caucasian. This needs to change. |

| Many dermpath programs are run primarily by a dermatology department and they are strongly biased towards white Americans. In my geographic area I have found that dermatology groups who hire dermatopathologists would rather hire a white pathologist who is not specialty trained than a non-caucasian, well trained, board certified, published and experienced dermatopathologist. |

| The lack of objectivity and personal discretions contribute to the lack of diversity. Your connections rather your merit plays more in selection. More than our subjective opinions, one should examine the diversity in leadership and fellowship directors and you will get the answers. |

| There is a clear diversity problem caused by Dermpath attendings. They see applicants as derm trained or path trained. They tent to not choose (offer) non-US graduates. They behave differently to non-native speakers. |

| There is discrimination, bias and less range of opportunity for pathology-trained dermatopathologists versus the dermatology trained dermatopathologists. This is especially apparent when I applied for dermatopathology jobs at academic institutions, especially when the position was in a dermatology department. This lack of diversity and discrimination also applies to private equity dermatology practices in the private sector. |

DISCUSSION:

Dermatopathologists are derived from two medical specialties of over 25000 physicians in the United States.8 The results of our survey study show a balanced distribution of gender and sexual identities within the specialty, similar to national demographic averages.8, 9 However, our study confirms racial disparities among the population sampled, compared to the U.S. population distribution,9 with Black and Hispanic dermatopathologists being the most underrepresented racial groups in our survey results. These results are similar to a recent analysis showing persistent racial disparities among incoming dermatopathology fellows in the past decade.10 Veteran status among dermatopathologists is close to national average of about 10%11 while reported disability status in our results is similar to the prevalence reported in medicine in general.12

While racial disparity exists in the field of pathology itself, 13 our survey data suggests that - particularly in data from more recently graduated dermatopathologists- pathology is contributing more to an increasingly diverse pool in terms of gender, race and foreign graduates in dermatopathology. This is supported by the trend that fewer dermatology residents have been applying for dermatopathology fellowships in recent years.14, 15 Pathology-trained dermatopathologists have been stably represented each year since the early/mid 2000s14. In early 2000s, pathology residency requirements decreased from 5 to 4 years, and since that time, the majority of pathology resident graduates pursue at least one year of fellowship training16. Dermatopathology is one of those options for fellowship training and continues to attract interest. There is minimal literature discussing how and why residents (both dermatology-trained and pathology-trained) choose certain fellowship opportunities, so reasons are largely speculative. Factors for fellowship choice often include future job opportunities, reimbursement considerations, lifestyle and utility/need for dermatopathology skills in future career.

While a large percentage of dermatology-trained dermatopathologists identified as white and male in our survey, aligning with prior studies about racial disparities in dermatology 17, 18, these respondents also tended to have been in practice longer. Evidence supports that gender equity in dermatology has increased in recent years, 18, 19 but those advances may not have yet translated into dermatopathology or were not captured by our point-in-time survey. Community dermatopathologists were found to be relatively less gender and racially diverse but also relatively more years in practice, compared to their academic counterparts. All these associations in totality point toward a shift in gender and racial diversity in the newer generation of dermatopathologists.

Bivariate associations of participant characteristics versus questionnaire items and aggregates revealed that White and US graduate respondents were more likely to have positive perceptions about diversity, inclusion, and engagement within the dermatopathology community. This result is perhaps not surprising, as both represent dominant groups in U.S. medicine. Those respondents not identifying as part of these dominant groups are more likely to experience discrimination, racism, or bias, and therefore 1) recognize its occurrence more readily than those not experiencing it and 2) have more negative perceptions about the state of diversity in our field.

Analysis of the perception statements (Appendix A, and Figure 1) on the survey indicated that respondents generally agreed that the dermatopathology community was inclusive with opportunities for engagement. The three statements with the strongest levels of agreement were related to engagement and inclusivity: “There are opportunities for me to openly communicate and engage within the dermatopathology community”, “The dermatopathology community is accepting of people of all races/ethnicities/sexual identities, regardless of disability or veteran status”, and “I feel included and respected as part of the dermatopathology community”. Statements resulting in less agreement and more negative perceptions from respondents included those related to accommodations for disability, equitable funding opportunities, and the general perception of a diversity problem within the specialty. Similarly, there was more disagreement from respondents about the degree of diversity within individual organizations and within dermatopathology leadership, and several open comments (Table 2) suggested/supported increasing racially diverse representation at the highest levels of the society. Lastly, a few comments highlighted a perception of pathology-trained dermatopathologists being treated differently than dermatology- trained dermatopathologists; future studies may wish to further investigate these claims as a source of bias or inequity in our subspecialty.

A significant limitation of our study is the relatively low response rate, as only 15% of the population was sampled. However, this sample size produces at least 90% confidence with a precision of 4% for rare events with less than 15% prevalence), and 90% confidence with a precision of 5% for events with less than 30% prevalence. As a survey study in which a convenience sample was taken, our data are certainly subject to response bias, which would further lower our confidence in having collected an adequate sample. In addition, while the study provides valuable baseline point-in-time data, the results related to self-reported years of experience should not be assumed to be longitudinal trends in the field, since we were not measuring the responses of the same individuals over time.

Future Directions & Recommendations:

Increasing diversity in medicine may appear challenging because focus is on recruiting the most talented candidates for delivery of quality patient care and lack of such standards in historically underrepresented groups has often been cited as the reasons for lack of representation.20 In reality, diverse and culturally competent work force and leadership benefits employees and (in medicine) patients.21 While evidence-based recommendations are few, efforts to increase DEI could focus on development of holistic criteria (including career environments, available opportunities, cultural competence and humility, etc) and standardized recruitment toolkit/questions for fellowship selection and job recruitment. Curriculum focusing on health disparities, implicit bias and cultural humility should also be integrated into residency/fellowship curriculum and in-particular for program directors and fellowship applicants. The authors also invite the readers to analyze their own implicit bias by taking the Harvard implicit association test.22 Pipeline focused measures in academia (from undergraduate through faculty appointments) for historically excluded populations and those at smaller institutions could include structured mentorship, research opportunities, financial grant programs and invited lectures.23, 24, 25 These efforts will be critical for recruitment, ongoing engagement, and retention of a diverse dermatopathology workforce. At the professional association level, a DEI committee and experts consultation incorporating a broad stakeholder base would help identify target avenues for improvement and affirm the commitment of leadership towards creating and maintaining a culture of DEI, similar to efforts and initiatives by the American Academy of Dermatology, American Society for Clinical Pathology and College of American Pathologists.

CONCLUSIONS:

Our survey indicates that dermatopathology has a narrow gap in terms of gender parity and satisfactory representation of sexual identities, however, racial disparity still exists. The information shared in this study in particular about working environments is overall encouraging, but hopefully it will create momentum for organized, intentional and long-lasting actions by individuals, departments and professional organizations towards furthering DEI measures in dermatopathology.

Acknowledgements:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center For Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number UL1 TR003107. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix A. Diversity statements, responded on a 1–5 Likert scale.

| 1. Dermatopathologists in my institution/practice setting are diversely represented. |

| 2. There are opportunities for me to openly communicate and engage within the dermatopathology community. |

| 3. I feel included and respected as part of the dermatopathology community. |

| 4. The dermatopathology community has a diversity problem. |

| 5. The dermatopathology community is accepting of people of all races/ethnicites/sexual identities, regardless of disability or veteran status. |

| 6. Dermatopathologist leaders in national/international organizations are diversely represented. |

| 7. There are accommodations made for disability within the dermatopathology community |

| 8. Funding opportunities for members of our dermatopathology community are available and administered in an equitable manner. |

Appendix B: Spearman correlation of perception statements.

Figure 3:

Spearman Correlations of Diversity items

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: None

Conflicts of Interests: None

REFERENCES:

- 1.Frey W. The nation is diversifying even faster than predicted, according to new census data. https://www.brookings.edu/research/new-census-data-shows-the-nation-is-diversifying-even-faster-than-predicted/ Last accessed on May 17th, 2022.

- 2.Lopez L, Hart LH, Katz MH. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities Related to COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325(8):719–720. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.26443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson-Agbakwu CE, Ali NS, Oxford CM, Wingo S, Manin E, Coonrod DV. Racism, COVID-19, and Health Inequity in the USA: a Call to Action. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022. Feb;9(1):52–58. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00928-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tzovara A, Amarreh I, Borghesani V, et al. Embracing diversity and inclusivity in an academic setting: Insights from the Organization for Human Brain Mapping. Neuroimage. 2021; 229:117742. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2021.117742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith MM, Rose SH, Schroeder DR, Long TR. Diversity of United States medical students by region compared to US census data. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015; 6:367–72. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S82645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freese C. Organizational change and the dynamics of psychological contracts: A longitudinal study. 2007. Ridderkerk: Ridderprint Offsetdrukkerij B.V [Google Scholar]

- 7.Person SD, Jordan CG, Allison JJ, Fink Ogawa LM, Castillo-Page L, Conrad S, Nivet MA, Plummer DL. Measuring Diversity and Inclusion in Academic Medicine: The Diversity Engagement Survey. Acad Med. 2015; 90(12):1675–83. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Physician Specialty Data Report. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-sex-and-specialty-2019. Last accessed December 29, 2021

- 9.United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/LFE046219 and https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/11/census-bureau-survey-explores-sexual-orientation-and-gender-identity.html. Last accessed December 29, 2021.

- 10.Rehman R, Azam M, Osto M, Daveluy S, Mehregan D. Gender and Ethnic Representation of Incoming Dermatopathology Fellows: A 10-Year Analysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022; 44(3):234–235. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000002129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2020/veterans-report.html. Last accessed January 24th, 2022.

- 12.Nouri Z, Dill MJ, Conrad SS, Moreland CJ, Meeks LM. Estimated Prevalence of US Physicians With Disabilities. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(3):e211254. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White MJ, Wyse RJ, Ware AD, Deville C. Current and Historical Trends in Diversity by Race, Ethnicity, and Sex Within the US Pathology Physician Workforce. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020; 154(4):450–458. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brodell MD RT, Ferringer T Dermatopathology: An Exciting, Innovative, and Compelling Dermatology Subspecialty Worthy of Continued Consideration among Dermatology Residents. SKIN The Journal of Cutaneous Medicine, 2019. 3(4), 286–290. 10.25251/skin.3.4.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Board of Dermatology 2021 Annual Report. https://dlpgnf31z4a6s.cloudfront.net/media/287471/2021-abd-annual-report-dec-22.pdf. Last accessed October 10th, 2022.

- 16.Lagwinski N, Hunt JL. Fellowship trends of pathology residents. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(9):1431–6. doi: 10.5858/133.9.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinojosa JA, Pandya AG. Diversity in the dermatology workforce. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2016; 36(4):242–245. doi: 10.12788/j.sder.2016.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu AG, Lipner SR. National trends in gender and ethnicity in dermatology training: 2006 to 2018. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022; 86(1):211–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shah A, Jalal S, Khosa F. Influences for gender disparity in dermatology in North America. Int J Dermatol. 2018. Feb;57(2):171–176. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guevara JP, Wade R, Aysola J. Racial and Ethnic Diversity at Medical Schools - Why Aren’t We There Yet? N Engl J Med. 2021;385(19):1732–1734. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2105578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradley EH. Diversity, Inclusive Leadership, and Health Outcomes. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2020; 9(7):266–268. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2020.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Project Implicit. Take A Test. https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html. Last accessed December 29, 2021

- 23.Pritchett EN, Pandya AG, Ferguson NN, Hu S, Ortega-Loayza AG, Lim HW. Diversity in dermatology: Roadmap for improvement. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018; 79(2):337–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Mouratidis RW. Where are the rest of us? Improving representation of minority faculty in academic medicine. South Med J. 2014;107(12):739–44. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez JE, Campbell KM, Fogarty JP, Williams RL. Underrepresented minority faculty in academic medicine: a systematic review of URM faculty development. Fam Med. 2014; 46(2):100–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]