Abstract

The NLRP3 inflammasome is a cytoplasmic supramolecular complex that is activated in response to cellular perturbations triggered by infection and sterile injury. Assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome leads to the activation of caspase-1, which induces the maturation and release of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18 as well as the cleavage of gasdermin D, which promotes a lytic form of cell death. Production of IL-1β via NLRP3 can contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammatory disease whereas aberrant IL-1β secretion through inherited NLRP3 mutations causes autoinflammatory disorders. We discuss in this review recent developments about the structure of the NLRP3 inflammasome, and the cellular processes and signaling events controlling its assembly and activation.

Keywords: Potassium efflux, Mitochondria, Golgi, Metabolism, Ubiquitination, Phosphorylation

The NLRP3 inflammasome: an essential component of the innate immune system

The innate immune system detects the presence of microbes and sterile cellular injury to initiate protective immune responses that promote the elimination of invading pathogens and the repair of damaged tissue. This initial activation of immune responses is largely mediated by host germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that sense molecular motifs conserved in microbes, endogenously derived damage-associated molecules, and cellular activities induced by pathogen virulence factors [1].

One class of intracellular PRRs is the inflammasome-forming sensors that form multimeric protein complexes upon activation leading to the induction of immune responses. After assembly, inflammasomes enable the proteolytic activation of caspase-1 which promotes the processing and release of mature IL-1β and IL-18, as well as the cleavage of gasdermin D (GSDMD) that promotes pore formation and pyroptosis (see Glossary), a lytic form of cell death [2, 3]. The most well-characterized inflammasome is induced through NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3), a PRR that belongs to the NOD-like receptor (NLR) family [2, 3]. The NLRP3 inflammasome promotes the immune system to fight microbial infections; on the other hand, the aberrant activation of NLRP3 through inherited mutations causes several autoinflammatory disorders, and chronic activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome can contribute to the pathogenesis of several inflammatory disorders including diabetes, gouty arthritis, silicosis, atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease [4]. In addition, the NLRP3 inflammasome is important in cancer and metabolic diseases [5]. Here we focus on the recent advances regarding the structure of the NLRP3 inflammasome, and the cellular processes and signaling events controlling its assembly and activation.

NLRP3 structure

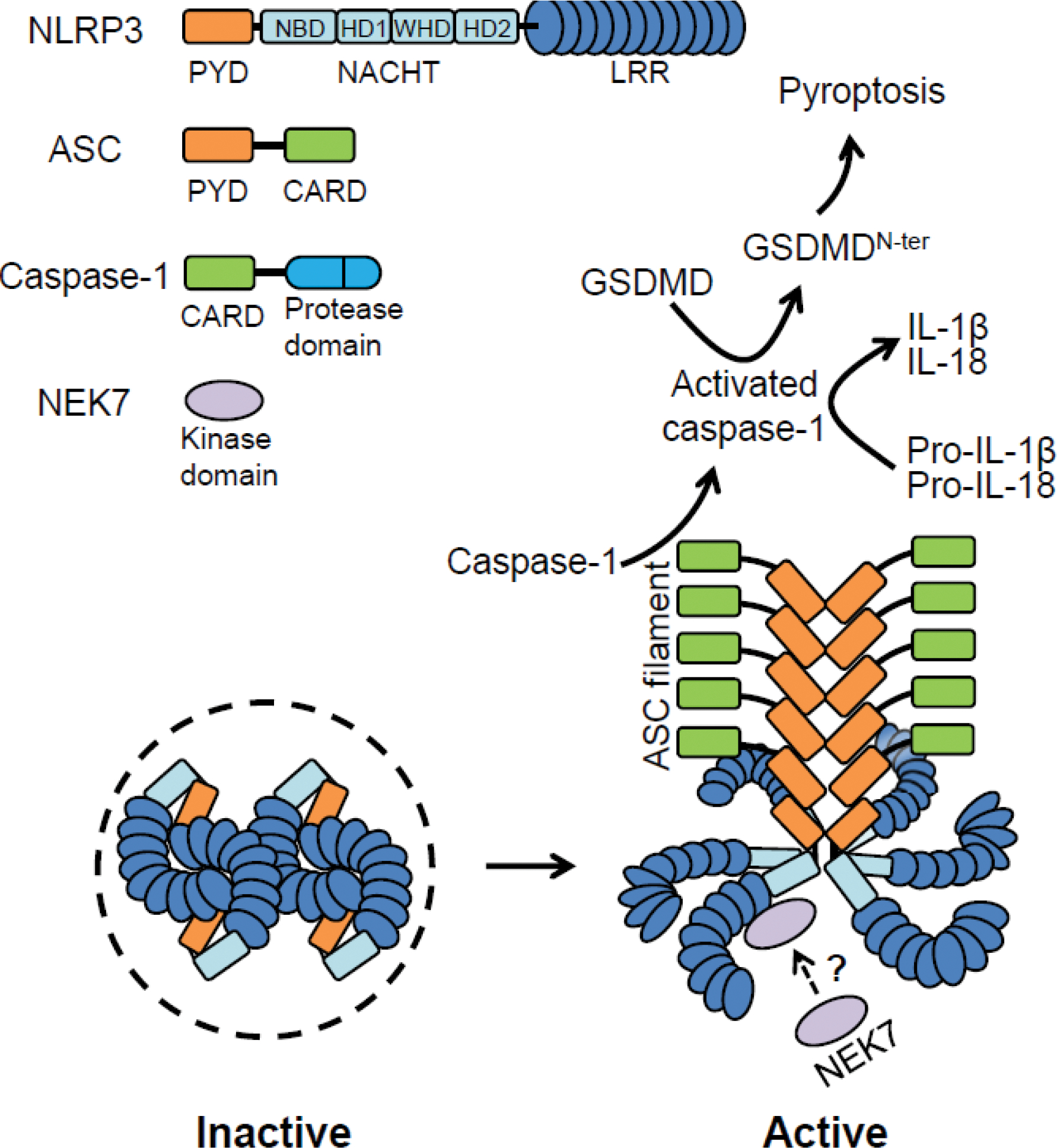

NLRP3 consists of a N-terminal pyrin domain (PYD), a centrally located adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) domain known as nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD or NACHT) that comprises nucleotide-binding domain (NBD), helical domain 1 (HD1), winged helix domain (WHD) and helical domain 2 (HD2) and C-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain that consists of 12 repeats (Figure 1) [6]. Like most inflammasomes, the NLRP3 inflammasome includes the adaptor ASC that is composed of a PYD that associates with the PYD of NLRP3 and a caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD) that interacts with the CARD of caspase-1. Upon inflammasome activation, caspase-1 recruited by the oligomerized ASC can be activated through proximity-induced self-cleavage (Figure 1) [2, 3]. In mouse macrophages, NIMA-Related Kinase 7 (NEK7), a mitotic kinase that interacts with NLRP3 is required for inflammasome activation [7–9]. However, NEK7 appears to function in NLRP3 priming, but not the activation process in human macrophages [10]. In contrast, NLRP11, a NLR family member that is absent in mice, was identified as a component of the NLRP3 inflammasome required for NLRP3 activation in human macrophages [11]. Although further work is needed to verify these results, these observations suggest differential regulation of the NLRP3 inflammation across species.

Figure 1. Components of the NLRP3 inflammasome and proposed model of NLRP3 activation.

Components of NLRP3 inflammasome: NLRP3, ASC, caspase-1 and NIMA-related kinase 7 (NEK7) (top left). The inactive form of NLRP3 (human 10-mer, mouse 12–16 mer) (bottom left). Only four of the NLRP3 monomers are displayed for simplicity to illustrate interactions among leucine-rich repeats (LRRs). The hypothetical model of the active NLRP3 inflammasome (bottom right). For simplicity, only two of the pyrin domains (PYDs) of NLRP3 interacting with the PYDs of ASC are shown. Abbreviations GSDMD, gasdermin D; IL, interleukin.

The first structure of NLRP3 was revealed by cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM) of PYD-deleted ADP-bound human NLRP3 in its inactive conformation in complex with an artificial dimer of NEK7 [6]. NLRP3 and NEK7 interact through two interfaces, one involving the LRRs of NLRP3 and the first half of the NEK7 C-lobe and a second interface between the NACHT domain and the second half of the NEK7 C-lobe [6]. Mutations of amino acid residues involved in the NLRP3-NEK7 interface impaired NLRP3 inflammasome activation [6]. The work suggested that in addition to the NEK7-NLRP3 interaction, further conformational changes in NLRP3 may be needed for inflammasome activation including those mediated by ATP binding and other unknown events [6]. One of these events may be the binding of the receptor for activated C kinase 1 (RACK1) with both NLRP3 and NEK7 as this interaction is important for conformational changes required for inflammasome activation [12].

Originally, it was proposed that NLRP3 exists in a monomeric state with a closed conformation causing auto-inhibition and upon stimulation, NLRP3 assumes an open conformation that enables its oligomerization and activation [3]. This concept was challenged by three recent publications revealing the Cryo-EM structure of the full-length human and mouse NLRP3 in an inactive form with and without the NLRP3 inhibitor MCC950 (also known as CRID3) [13–15]. Inactive NLRP3 forms oligomers that can assemble via LRR-LRR face-to-face interactions between two monomers, and these pairs then interact with other pairs through back-to-back LRR interactions to form a circular “double ring” or “cage” structure, while the NACHT domains barely touch each other [13–15]. The PYDs are shielded inside the “double ring” to presumably prevent inadvertent NLRP3 activation. Because the LRR-LRR face-to-face interface in inactive NLRP3 overlaps with the interface between the LRRs of NLRP3 and NEK7, the binding of NEK7 with NLRP3 could disrupt interactions that maintain the inactive state of NLRP3 (Figure 1). In the proposed activation model, NEK7 binding and other unknown events disassemble the “double ring” into a “single ring” structure and NLRP3 assumes a conformation in which the exposed PYDs are capable of recruiting and nucleating ASC, which leads to caspase-1 activation (Figure 1). There are subtle differences between the three structures of inactive NLRP3 including the number of monomers; for example, human NLRP3 exhibited a decameric structure whereas mouse NLRP3 formed 12–16-mers [13–15]. The different results may reflect technical or species-specific variability. Mutations of amino acid residues in the LRR-LRR dimerization interface of human NLRP3 led to NLRP3 auto-activation and hyperactivation, supporting a role of the LRR domain in keeping the “double ring” structure of NLRP3 inactive [13]. However, this finding contradicts two reports, in which NLRP3 lacking the LRR domain retains similar function as full-length NLRP3 [16, 17]. The reason for the discrepancy in results is unclear and warrants further investigation.

NLRP3 inflammasome activation

The NLRP3 inflammasome can be activated through three pathways: canonical, non-canonical and alternative pathways. Here we focus on canonical activation of NLRP3 and discuss briefly NLRP3 activation via the non-canonical inflammasome and the alternative pathways (Box 1). In mouse macrophages, canonical NLRP3 inflammasome activation is a two-step process. A priming signal is required before a subsequent signal activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Priming is typically induced by stimulation of macrophages with Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands, IL-1β or TNFα which activates NF-κB, leading to the upregulation of NLRP3 and IL-1β [18, 19]. Priming also results in post-translational modification of NLRP3, which will be discussed later, to license the activation of NLRP3. Following priming, the NLRP3 inflammasome can be activated by a wide array of stimuli including ATP, nigericin, gramicidin, bacterial toxins, and particulate matter such as crystals of silica, aluminium hydroxide, monosodium urate, and calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate. The chemical and structural diversity of these activating stimuli suggests that NLRP3 senses a common cellular signal induced by the various stimuli (Figure 2). Here we concentrate on recent progress in understanding the cellular and signaling events leading to canonical NLRP3 activation.

Box 1. Non-canonical and alternative inflammasome activation.

The non-canonical inflammasome is triggered by intracellular lipopolysaccharide (LPS) that is recognized by mouse caspase-11 and human caspase-4 or caspase-5 to trigger pyroptosis via gasdermin D cleavage [103]. Activation of the non-canonical inflammasome also activates the NLRP3 inflammasome by inducing K+ efflux [103, 104]. In the alternative NLRP3 activation pathway, stimulation with TLR ligands including LPS directly activates NLRP3 in certain animal and human cells. For example, LPS alone activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in mouse dendritic cells and mice in vivo independently of P2X7 stimulation [105], although the molecular pathway in the mouse remains unknown. Furthermore, stimulation of human monocytes with TLR2 or TLR4 agonists induces IL-1β secretion, but not in human macrophages or dendritic cells [106]. LPS-induced IL-1β secretion in human monocytes depends on NLRP3-ASC-caspase-1, but is independent of K+ efflux, ASC speck formation and pyroptosis [23]. Instead, this LPS-induced alternative pathway is mediated through TLR4-TRIF-RIPK1-FADD-caspase-8 signaling upstream of NLRP3 in human monocytes [23]. Apolipoprotein C3, a protein component of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), can also engage TLR2 and TLR4, triggering the release of IL-1β in human monocytes via this pathway [107]. Activation of NLRP3 by caspase-8 is also observed during viral infection. For instance, upon sensing Influenza A virus, Z-DNA binding protein 1 regulates NLRP3 activation through RIPK1-RIPK3-caspase-8 signaling [108]. However, the mechanism by which caspase-8 activates NLRP3 remains poorly understood.

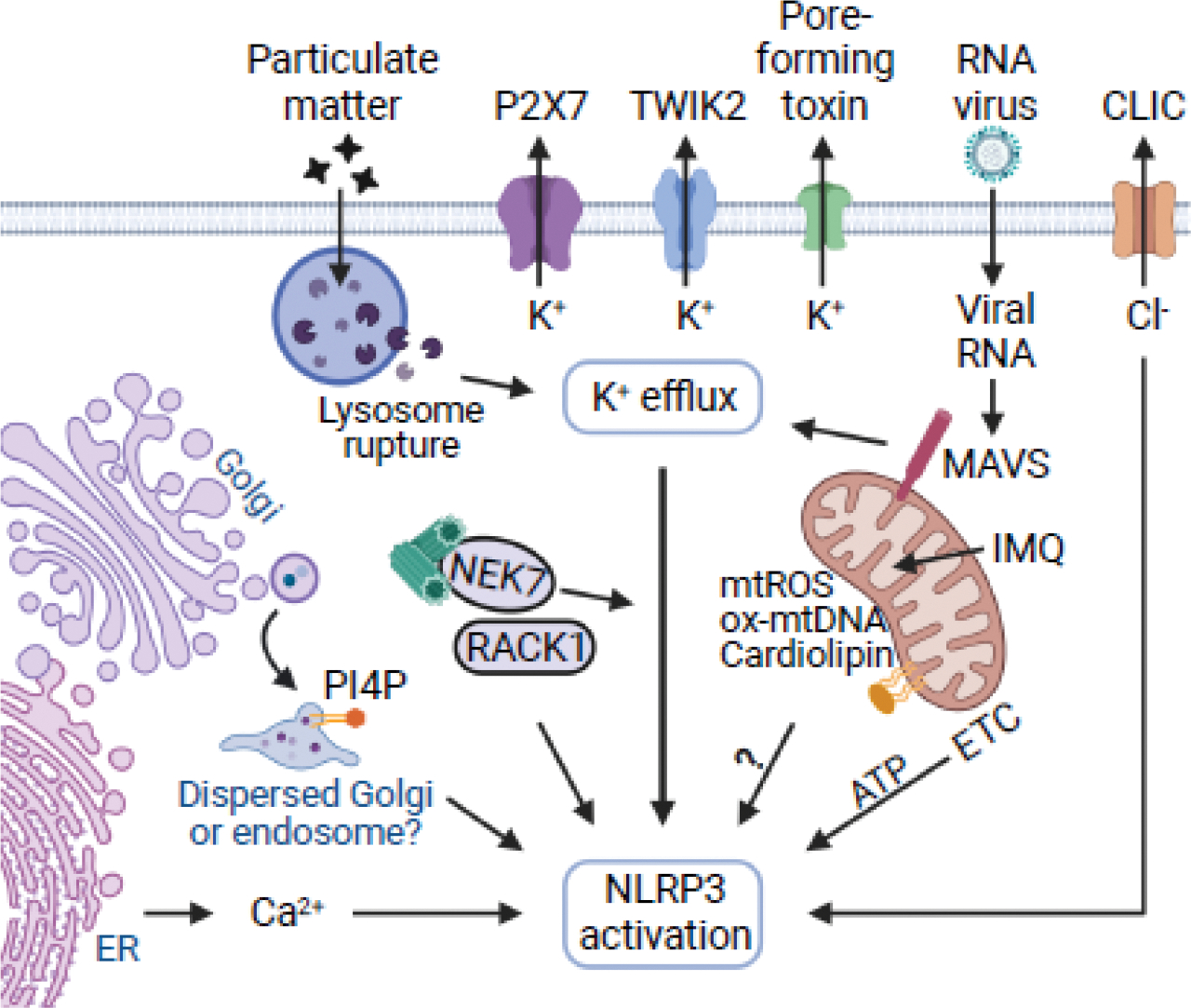

Figure 2. Cellular events leading to NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

The activation signal is provided by an array of stimuli including particulate matter, ATP, pore-forming toxins and RNA viruses. Particulate matter via lysosomal membrane damage and viral RNA through mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) induce K+ efflux, which also occurs upon stimulation with most NLRP3 stimuli. As an exception, imiquimod (IMQ) activates NLRP3 without inducing K+ efflux. NIMA-related kinase 7 (NEK7) functions downstream of K+ efflux. NEK7 is shown associated with the centrosome (in green). The binding of receptor for activated C kinase 1 (RACK1) to NEK7 and NLRP3 is required for inflammasome activation, but the mechanism remains poorly understood. Mitochondrial ETC sustains NLRP3 activation via phosphocreatine-dependent generation of ATP. Dysfunction of the mitochondria is associated with the release of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mtROS) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) into the cytosol as well as localization of cardiolipin to the outer mitochondrial membrane which may promote NLRP3 activation. Upon stimulation, NLRP3 transition to membranes of the dispersed trans-Golgi network (TGN) or endosomes which may be important for inflammasome activation. CLIC, chloride intracellular channel; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ETC, electron transport chain; ox-mtDNA, oxidized; PI4P, phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate; P2X7, purinergic receptor P2X 7; TWIK2, two-pore domain weak inwardly rectifying K+ channel 2. This figure was created with resources from BioRender.com

Activation and regulation by ions

Potassium

Potassium (K+) efflux is induced by practically all NLRP3-activating stimuli and is required for NLRP3 activation (Figure 2) [20]. However, certain imidazoquinolinamines including imiquimod (IMQ) and CL097, and peptidoglycan can activate NLRP3 independently of K+ efflux [21, 22]. In human monocytes activation of NLRP3 with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) alone via an alternative pathway (Box 1) is K+ efflux independent [23]. Thus, in some cells, there are mechanisms of NLRP3 activation that can bypass K+ efflux. In mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages, lowering the extracellular concentration of K+ (≤ 0.5 mM) is sufficient for NLRP3 activation in the absence of additional stimulation, while increasing the extracellular K+ concentration to 30–45 mM has an inhibitory effect on NLRP3 activation [20]. Mechanistically, bacterial toxins, the K+ ionophores nigericin and gramicidin, extracellular ATP via the purinergic P2X7 channel, and the two-pore domain weak inwardly rectifying K+ channel 2 (TWIK2) form pores or permeabilize the plasma membrane enabling K+ efflux [20, 24]. Studies with a bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) assay showed that low intracellular K+ concentration leads to a conformational change in inactive NLRP3 [25]. This structural change is promoted by a unique linker sequence and a short FISNA domain located between the PYD and the NACHT domain of NLRP3 [25]. Notably, replacement of the PYD and the linker sequence of NLRP6, another inflammasome-forming NLR family member that does not respond to K+ efflux, with the PYD, linker sequence and FISNA domain of NLRP3 confers the ability to respond to NLRP3 stimuli [25]. However, this chimeric NLRP6 also responded to IMQ [25], a NLRP3 activator that does not induce K+ efflux, suggesting that K+ efflux-independent triggers induce similar conformational changes. Thus, additional studies are needed to understand how K+ efflux triggers NLRP3 activation.

Sodium

Sodium (Na+) influx has been suggested to regulate NLRP3 activation induced by certain agonists. Lowering extracellular Na+ concentration suppresses NLRP3 activation induced by nigericin, gramicidin and K+-free medium. However, replacing the extracellular Na+ with the cation choline does not compromise NLRP3 activation mediated by ATP, silica, Al(OH)3 and aerolysin [20]. Moreover, Na+ influx is not sufficient for NLRP3 activation because increasing cytosolic Na+ concentrations with a Na+ ionophore does not trigger NLRP3 activation [20]. Monosodium urate crystals increase the intracellular Na+ concentration, resulting in water influx which reduces the intracellular K+ concentration below the threshold required for NLRP3 activation [26]. This suggests that the regulatory role of Na+ in NLRP3 activation is indirect and dependent on the intracellular K+ concentration.

Chloride

The role of chloride (Cl−) fluxes in NLRP3 activation is controversial. Chloride intracellular channels (CLICs) can function downstream of K+ efflux to promote NLRP3-NEK7 interaction and NLRP3 activation [27]. The role of CLIC1 and CLIC4 appears complex in that these channels can also regulate NLRP3 priming including IL-1β transcription [28]. In contrast, the kinase WNK1 negatively regulates NLRP3 activation by modulating chloride/cation cotransporters and inhibiting Cl− efflux [29]. However, chloride/cation cotransporters regulate not only intracellular Cl−, but also intracellular K+ [29]. Furthermore, Cl− efflux promoted ASC oligomerization and inflammasome priming, but not caspase-1 activation which required K+ efflux [30]. These results suggest that Cl− efflux alone is not sufficient for NLRP3 activation, although intracellular Cl− may contribute to NLRP3 activation.

Calcium

Calcium (Ca2+) fluxes have also been linked to NLRP3 activation. An increase in cytosolic Ca2+ induced in response to NLRP3 agonists was suggested to be important for NLRP3 activation [31]. A release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), a major calcium reservoir, to the cytosol through the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor (IP3R) was suggested to be involved because chemical or genetic inhibition of IP3R prevented Ca2+ release and attenuated NLRP3 activation [32]. Since Ca2+ overload leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, it was proposed that Ca2+-mediated mitochondrial damage led to NLRP3 activation [31]. However, inhibition of NLRP3 activation by chemical inhibition of IP3R was independent of Ca2+ signaling [33]. In addition, influx of extracellular Ca2+ is not required for NLRP3 activation in some studies [33]. Thus, there is no convincing evidence supporting a specific role for Ca2+ fluxes in NLRP3 activation.

Activation and regulation by cellular organelles

Mitochondria

The role of the mitochondria in NLRP3 activation remains controversial (Figure 2). The mitochondria can provide a subcellular site for NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and molecules including mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and DNA that can promote NLRP3 activation. A role for the mitochondrial proteins mitofusin-2, cardiolipin, and mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein (MAVS) in NLRP3 activation has been proposed [34–36]. However, localization of NLRP3 to the mitochondria remains controversial [37]. Although MAVS regulates NLRP3 activation induced by RNA viruses, the role of MAVS in non-viral stimuli was not confirmed [34, 38]. Cardiolipin, a phospholipid that is normally located in the mitochondrial inner membrane and externalized in response to mitochondrial dysfunction, can bind the HD2 and the beginning of the LRR domain of NLRP3 to promote inflammasome activation [35]. However, additional studies are needed to clarify the role of cardiolipin, and mitochondrial dysfunction in general in NLRP3 activation.

Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mtROS) that is generated largely through the electron transport chain (ETC) complex I and III has been linked to NLRP3 activation [39]. In line with this, IMQ and CL097 were suggested to activate NLRP3 by targeting quinone oxidoreductases (NQO2) and mitochondrial Complex I which promoted mtROS production [21]. However, whether mtROS is the trigger or a consequence of NLRP3 activation was unclear. In more definitive studies, the ETC complex I or III was replaced with an alternative oxidase that maintained the normal ETC function, but is unable to generate mtROS. In the absence of mtROS, the cells exhibited normal NLRP3 activation and IL-1β release [40], suggesting that mtROS is actually not required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) can be released into the cytosol from damaged mitochondria to promote NLRP3 activation. For example, oxidized mtDNA can bind and activate NLRP3 [41]. Furthermore, TLR-mediated synthesis of mtDNA was necessary for NLRP3 activation, as genetic mtDNA depletion compromised NLRP3 activation [42]. However, the release of mtDNA can also occur as a consequence of NLRP3 activation [43]. Studies have implicated the ETC in NLRP3 activation through phosphocreatine-dependent ATP production [40]. Thus, depletion of mtDNA may indirectly impact NLRP3 activation through its effect on ETC activity. Overall, the role for mtDNA in NLRP3 activation remains controversial.

Microtubule-organizing center (MTOC)

Centrosomes, the main MTOC, are essential for organizing the microtubule network in most animal cells. There is mounting evidence that the MTOC is involved in inflammasome activation. For example, the NEK7 kinase that binds and promotes NLRP3 activation localizes to the centrosome (Figure 2) [44]. Because the centrosome regulates mitosis, it was suggested that mitosis and NLRP3 activation are mutually exclusive, due to the limited availability of NEK7 during mitosis [9]. Another centrosomal kinase, polo-like kinase 4 (PLK4), negatively regulates NLRP3 activation by phosphorylating NEK7 and inhibiting its association with NLRP3 [45]. In addition, NLRP3 localizes to the centrosomal MTOC upon activation [46, 47]. Microtubule-affinity regulating kinase 4 (MARK4) promotes the mobilization of NLRP3 to the MTOC where a single ASC inflammasome punctum assembles in each activated cell [47]. The dynein adapter histone deacetylase 6 (HDAC6) may be involved in the formation of the ASC speck via microtubule-mediated transport of inflammasome components to the MTOC [46]. However, further studies are needed to understand how NLRP3 and ASC are transported to converge into the ASC speck for inflammasome assembly and activation.

Golgi apparatus and endosomes

Mounting evidence links NLRP3 activation to the Golgi apparatus (Figure 2). In initial studies, the SCAP-SREBP2 complex associated with NLRP3 to form a ternary complex that transported NLRP3 from the ER to the Golgi apparatus for optimal inflammasome assembly [48]. More recent studies showed that NLRP3 agonists trigger the formation of dispersed trans-Golgi network (dTGN) and the recruitment of NLRP3 to phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate (PI4P) vesicles was necessary for NLRP3 activation [37]. The recruitment of NLRP3 to the dTGN was dependent on a positively charged polybasic region located between the PYD and the NACHT domain of NLRP3 [37]. In this study, TGN38, which localizes to the Golgi, but also to membrane vesicles that recycle between the plasma membrane, endosomes and the TGN [49, 50], was used as a Golgi marker. Using different TGN markers, it was determined that upon NLRP3 stimulation the TGN remains largely intact, while TGN38 was trapped in endosomes that resemble “dispersed TGN” [51, 52]. Furthermore, retrograde vesicular trafficking of endosomes to the TGN was disrupted by NLRP3 agonists, leading to the accumulation of TGN38 and PI4P-membranes in endosomes. Genetic disruption of endosome-TGN retrograde transport induced NLRP3 activation with LPS alone [52]. Thus, this work suggested that NLRP3 senses the disruption of retrograde trafficking. However, NLRP3 stimuli can cause damage to the mitochondria and other intracellular organelles through ion fluxes which may be independent of NLRP3 activation [20]. Thus, further investigation is needed to clarify the role of the dTGN and vesicular trafficking in NLRP3 activation.

Lysosomes

The NLRP3 inflammasome is also activated by phagocytosis and accumulation of particulate matter in lysosomes, which causes membrane damage and the release of lysosomal cathepsin into the cytosol (Figure 2) [53]. Lysosomal membrane rupture appears to be sufficient for inflammasome activation because the lysosomotropic agent Leu-Leu-O-methyl ester activates NLRP3 [20, 53]. Cathepsin inhibitors blocked caspase-1 activation induced by particulate matter [53]. However, genetic ablation of several cathepsins shows no or minimal alteration of NLRP3 activation [54]. Furthermore, particulate matter-induced cell death is independent of inflammasome activation as it proceeds in the absence of caspase-1 and gasdermin D [55]. K+ efflux is important in inflammasome activation because K+ flux is induced after particulate matter internalization which precedes NLRP3 activation [20]. However, the molecular mechanism that accounts for K+ efflux after lysosomal damage remains unclear.

Other organelles

Cholesterol transport from lysosomes to the ER has been suggested to be required for NLRP3 activation, cholesterol transport blockade or depletion in ER membranes compromises NLRP3 activation [56]. However, the mechanism remains unclear. Ribosomes, the cellular sites for protein synthesis, have been proposed to regulate NLRP3 activation as halting of protein translation triggers NLRP3 activation [57]. Furthermore, polysaccharide galactosaminogalactan of the fungus Aspergillus fumigatus binds ribosomal proteins and blocks protein translation, which results in NLRP3 activation [58]. The role of ribosomes and protein translation in NLRP3 activation is intriguing and warrants further investigation.

Activation and regulation by metabolism

Glycolysis

During inflammation, macrophages undergo metabolic reprogramming to meet new bioenergetic demands that are required for effective macrophage function. Part of this reprogramming is the rapid upregulation of aerobic glycolysis to generate ATP from glucose [59]. Several studies have linked glycolysis to the regulation of NLRP3 activation and IL-1β production. For example, ablation of hexokinase-1, a kinase that catalyzes the first step in glycolysis, impaired LPS-induced NLRP3 activation and IL-1β release [60]. During bacterial infection, hexokinase-1 binds peptidoglycan-derived N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) promoting the translocation of the enzyme from the mitochondria into the cytosol and NLRP3 activation [22]. Incubation of macrophages with 2-deoxy-D-glucose, an inhibitor of glycolysis, reduced NLRP3 activation and IL-1β production [60]. Furthermore, genetic and pharmacological inhibition of pyruvate kinase isoenzyme M2 (PKM2), an enzyme that catalyzes the last step of glycolysis, compromised NLRP3 activation [61]. In contrast to these studies, blocking glycolysis by inhibiting other glycolytic enzymes such as GAPDH or alpha-enolase, was sufficient to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome [62]. The reason for these seemingly contradictory results is unclear, but it may reflect the complexity of interfering with multiple intertwining metabolic pathways in macrophages.

Tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle

In LPS-activated macrophages, the TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) are also upregulated, followed by nitric oxide-mediated disruption of the TCA cycle, leading to the accumulation of metabolites such as succinate and itaconate [63]. Succinate stabilizes the transcription factor hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), increasing IL-1β production [64]. Fumarate, another intermediate of the TCA cycle, inhibited nigericin-induced pyroptosis by modifying gasdermin D cysteine residues into S-(2-succinyl)-cysteine, which reduced gasdermin D processing and pore formation on the plasma membrane [65]. LPS also induces the production of itaconate by upregulating the expression of cis-aconitate decarboxylase, the enzyme responsible for the decarboxylation of the TCA cycle intermediate cis-aconitate in macrophages [66]. Itaconate decreases the expression of IL-1β and several components of the inflammasome thereby reducing NLRP3 activation [67]. In addition, 4-octyl-itaconate (OI), an itaconate derivative, can modulate NLRP3 activation by inhibiting the interaction of NLRP3 with NEK7 through dicarboxypropylation of C548 on NLRP3 [68]. In contrast, another study suggested that itaconate confers tolerance to NLRP3 activation by acting downstream of ASC speck formation [69]. In addition to the TCA metabolites, mitochondrial ETC activity is required for NLRP3 activation through phosphocreatine-dependent ATP production (Figure 2) [40]. These studies suggest complex regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome during metabolic reprogramming in macrophages.

Fatty acid metabolism

Fatty acid metabolism has also been implicated in NLRP3 activation. The saturated fatty acid palmitate induces NLRP3 activation [70] and inhibiting lipid synthesis by targeting mitochondrial uncoupling protein-2 (UCP2) or fatty acid synthase (FASN), compromised NLRP3 activation [71]. While lipid synthesis is required for NLRP3 activation, fatty acid oxidation seems to regulate this inflammasome. For example, genetic ablation of NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4) was associated with reduced expression of carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1A, a key mitochondrial enzyme in the fatty acid oxidation pathway. NOX4 deficiency and reduced fatty acid oxidation resulted in impaired NLRP3 activation, but the mechanism remains poorly understood [72]. In contrast, fatty acid oxidation generates ketone bodies. One of the ketone bodies, β-hydroxybutyrate, inhibits NLRP3 activation by suppressing K+ efflux [73].

NLRP3 inflammasome regulation by post translational modifications (PTMs)

Recent research has revealed roles for PTMs in NLRP3 priming and activation. Here we focus on ubiquitination and phosphorylation and discuss other PTMs including sumoylation and acetylation (Box 2).

Box 2. Sumoylation and acetylation of NLRP3.

Sumoylation is a process in which small ubiquitin-like modifier-1 (SUMO-1) proteins are covalently attached to lysine residues in proteins. The SUMO E3-ligase MAPL sumoylates and suppresses NLRP3 activation, while sentrin-specific protease 6 (SENP6) and SENP7 desumoylates NLRP3, promoting inflammasome activation [109]. NLRP3 sumoylation is also mediated by tripartite motif-containing protein 28 (TRIM28), another E3 SUMO ligase, which promotes NLRP3 expression by inhibiting NLRP3 ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [110]. SUMO-conjugating enzyme UBC9 also positively regulates NLRP3 activation through sumoylation of NLRP3 at K204 while desumoylation of NLRP3 is mediated by SENP3 [111].

Acetylation is a process in which acetyl groups are transferred from acetyl donors, such as acetyl-CoA, to proteins by acetyltransferases. Acetylation mainly occurs on lysine amino acid resides. Lysine acetyltransferase 5 (KAT5) mediates acetylation of NLRP3 at K24 which promotes inflammasome assembly by facilitating the interaction between NLRP3 and ASC or NEK7 [112]. However, another study reported that acetylation of NLRP3 at K21 and K22, instead of K24, plays a major role in promoting NLRP3 activation [113]. In contrast, NLRP3 deacetylation mediated by sirtuin 2 (SIRT2) suppresses inflammasome activation and aging-associated inflammation [113]. The reason for the discrepancy between the two studies remains unclear, although all lysine residues that are proposed to be acetylated reside in the PYD domain of NLRP3, which interacts with the PYD of ASC for inflammasome assembly. (Summarized in Table 1 in the main text.)

Ubiquitination

Several proteins can mediate the ubiquitination of NLRP3 through the addition of ubiquitin chains to regulate inflammasome activation (Table 1). At steady state, the F-box and leucine rich repeat protein 2 (FBXL2) mediates K48-linked polyubiquitination and degradation of NLRP3 while LPS-priming activates F-box protein O3 (FBXO3) to induce the degradation of FBXL2 which enhances NLRP3 expression [74]. The E3 ubiquitin ligase membrane-associated RING finger protein 7 (MARCH7) also limits NLRP3 expression via K48-linked ubiquitination in response to Dopamine D1 receptor signaling resulting in autophagic degradation of NLRP3 [75]. The E3 ligase tripartite motif containing protein 31 (TRIM31) also promotes proteasomal degradation of NLRP3 via K48 ubiquitination [76]. In contrast, E3 ligase ring finger protein 125 (RNF125) catalyzes K63-linked ubiquitination of the LRRs of NLRP3, which recruits E3 ligase Cbl proto-oncogene B (Cbl-b), which promotes K48-linked ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of NLRP3 [77]. Similarly, E3 ligase β-TrCP1 promotes proteasomal degradation of NLRP3 through K27-linked ubiquitination, which can be blocked by the interaction between NLRP3 and the transcription co-activator YAP [78]. In addition to facilitating NLRP3 degradation, ubiquitination can disrupt inflammasome assembly. Cullin1 (CUL1), a component of the Skp1-Cullin1-F-box E3 ligase complex, inhibits NLRP3 activation by binding NLRP3 and promoting its K63 ubiquitination at K689, which blocks the association of NLRP3 with ASC [79]. NLRP3-activating stimuli promote the dissociation of CUL1 from NLRP3, enhancing NLRP3 inflammasome assembly [79]. Moreover, the E3 ligase Ariadne homolog 2 (ARIH2) interacts with NLRP3 to promote its ubiquitination, while its genetic ablation inhibits NLRP3 ubiquitination and promotes NLRP3 activation [80]. In contrast to the negative role of ubiquitination in NLRP3 activation, E3 ligase Pellino2 catalyzes K63 ubiquitination of NLRP3 during priming and facilitates NLRP3 activation [81]. The E2 enzyme ubc13 potentiates NLRP3 inflammasome activation by promoting K63-linked polyubiquitination of mouse NLRP3 at K565 and K687 [82]. However, ubiquitination of of human NLRP3 at K689 (K687 in the mouse) by Cullin1 inhibits NLRP3 activation [79]. The reason for this inconsistency is unclear.

Table 1.

Regulation of NLRP3 through PTMsa

| PTM | Effect on NLRP3 activation | Enzyme | PTM siteb | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitination | Positive | Pellino2 | Unknown | [81] |

| ubc13 | Human: K567, K689; mouse: K565, K687 | [82] | ||

| Negative | FBXL2 | Human: K689; mouse: K687 | [74] | |

| MARCH7 | Unknown | [75] | ||

| TRIM31 | Unknown | [76] | ||

| RNF125 | Unknown | [77] | ||

| Cbl-b | Human: K496; mouse: K492 | [77] | ||

| β-TrCP1 | Human: K384; mouse: K380 | [78] | ||

| Cullin1 | Human: K689; mouse: K687 | [79] | ||

| ARIH2 | Unknown | [80] | ||

| Deubiquitination | Positive | UAF1/USP1 | Unknown | [83] |

| BRCC3 | Unknown | [84,85] | ||

| USP7/USP47 | Unknown | [86] | ||

| Phosphorylation | Positive | Pak1 | Human: T659; mouse: T657 | [92] |

| JNK1 | Human: S198; mouse: S194 | [97] | ||

| BTK | Human: Y136, Y140, Y143c, Y168; mouse: Y132, Y136, Y164 |

[100] | ||

| PKD | Human: S295; mouse: S291 | [102] | ||

| Negative | PKA | Human: S295; mouse: S291 | [87,88] | |

| EphA2 | Human: K136; mouse: K132 | [89] | ||

| AKT | Human: S5; mouse: S3 | [90] | ||

| CSNK1A1 | Human: S806; mouse: S803 | [98] | ||

| Dephosphorylation | Positive | PP2A | Human: S5; mouse: S3 | [93] |

| PTPN22 | Human: Y861; mouse: Y858 | [95] | ||

| PTEN | Human: Y32; mouse: Y30 | [96] | ||

| Sumoylation | Positive | TRIM28 | Unknown | [110] |

| UBC9 | Human: K204; mouse: K200 | [111] | ||

| Negative | MAPL | Unknown | [109] | |

| Desumoylation | Positive | SENP6/7 | Unknown | [109] |

| Negative | SENP3 | Human: K204; mouse: K200 | [111] | |

| Acetylation | Positive | KAT5 | Human: K26; mouse: K24 | [112] |

| Deacetylation | Negative | SIRT2 | Human: K23, K24; mouse: K21, K22 | [113] |

ARIH2, ariadne homolog 2; BRCC3, BRCA1/BRCA2-Containing Complex Subunit 3; BTK, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase; Cbl-b, Cbl proto-oncogene B; CSNK1A1, Casein Kinase 1 Alpha 1; EphA2, Eph receptor A2; FBXL2, F-box and leucine rich repeat protein 2; JNK1, c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1; KAT5, lysine acetyltransferase 5; MAPL, mitochondrial-anchored protein ligase; MARCH7, membrane-associated RING finger protein 7; Pak1, p21-activated kinase 1; PKA, protein kinase A; PKD, protein kinase D; PP2A, protein phosphatase 2; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; PTM, post-translational modification; PTPN22, protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 22; RNF125, ring finger protein 125; SENP3, sentrin-specific protease 3; SIRT2, Sirtuin 2; β-TrCP1, β-transducin repeat containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase; TRIM31, tripartite motif containing protein 31; UAF1, Ubiquitin specific peptidase 1-associated factor 1; Ubc13, ubiquitin conjugating enzyme 13; USP1, Ubiquitin Specific Peptidase 1

The numbering of amino acid residues is based on NP_004886.3 for Homo sapiens, and NP_665826.1 for Mus musculus.

Y143 of human NLRP3 is not conserved in the mouse.

In general, deubiquitination of NLRP3 promotes its activation. For example, the UAF1/USP1 deubiquitinase complex inhibits NLRP3 degradation by removing K48 polyubiquitination chains of NLRP3 [83]. BRCC3, a deubiquitinase for NLRP3, increases NLRP3 activation through the removal of ubiquitin chains from NLRP3 [84, 85]. Likewise, knockdown of two deubiquitinases, USP7 and USP47, compromises NLRP3 activation, although the mechanism is unclear [86]. Collectively, these studies suggest that in most cases ubiquitination negatively regulates NLRP3 activation by inducing NLRP3 degradation or disrupting inflammasome assembly.

Phosphorylation

Phosphorylation regulates NLRP3 activation by regulating inflammasome priming or assembly, or altering NLRP3 subcellular localization (Table 1). Through TGR5 bile acid receptor or prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) signaling, activated PKA phosphorylates NLRP3 at S295 on the NACHT domain and inhibits its ATPase activity [87, 88]. In mouse airway epithelial cells, EphA2, a tyrosine kinase receptor, phosphorylates NLRP3 at Y132 which interferes with inflammasome assembly [89]. At the steady state, AKT limits NLRP3 activation through phosphorylation of NLRP3 at S5, which inhibits PYD-PYD interactions and reduces NLRP3 ubiquitination on K496, blocking its proteasomal degradation of NLRP3 [90]. The TGF-β activated kinase 1 (TAK1) limits TNFα-induced NLRP3 activation at the resting state by inhibiting RIPK1-dependent NF-κB and ERK signaling [91]. In some cases, phosphorylation of NLRP3 promotes inflammasome activation. For example, the E. coli toxin CNF1 induces NLRP3 activation through P21 activated kinase 1 (Pak1)-mediated phosphorylation of NLRP3 at T659 of NLRP3 [92]. Interestingly, phosphorylation of NLRP3 at T659 is required for the interaction between NLRP3 and NEK7 [92].

Dephosphorylation of NLRP3 at S5 by Phosphatase 2A (PP2A) promotes NLRP3 activation [93]. TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and I-kappa-B kinase epsilon (IKKε) counteract the role of PP2A on S5 to limit NLRP3 activation, although these kinases may also act on other amino acid residues that impact NLRP3 activation [94]. Similar to PP2A, other phosphatases can also promote NLRP3 activation. For example, protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor 22 (PTPN22) dephosphorylates NLRP3 at Y861, reducing NLRP3 autophagic degradation [95]. Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) dephosphorylates NLRP3 at Y32 in the PYD, enhancing the interaction between NLRP3 and ASC [96].

Cross-talk between phosphorylation and ubiquitination of NLRP3 has been observed. During priming, JNK1 phosphorylates NLRP3 at S194 to induce BRCC3-mediated deubiquitination and activation of NLRP3 [97]. NLRP3 is also phosphorylated at S803 via the CSNK1A1 kinase during priming while activating signals induce NLRP3 dephosphorylation at the same residue, increasing the recruitment of NEK7 to NLRP3 which promotes BRCC3-mediated deubiquitination and activation of NLRP3 [98].

Phosphorylation can also regulate the subcellular location of NLRP3. A polybasic linker between the PYD and NACHT domain is known to enable the recruitment of NLRP3 to the dTGN (see the section of Golgi apparatus and Endosomes) [37]. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) interacts with NLRP3 and ASC [99], phosphorylates NLRP3 at tyrosine residues 136, 140, 143 and 168, which reside within or adjacent to the polybasic PYD-NACHT linker region that promotes NLRP3 translocation from the intact Golgi to the dTGN and inflammasome activation [100]. These tyrosine modifications alter the net charge of the linker region, providing a plausible mechanism by which BTK promotes NLRP3 activation [100]. In addition, phosphorylation mediated by BTK occurs within the FISNA domain, which facilitates conformation changes resulting from K+ efflux upon NLRP3 activation [25]. Thus, further studies are warranted to determine whether BTK-mediated phosphorylation links K+ efflux to NLRP3 activation. IKKβ activity is also required to recruit NLRP3 to TGN membranes; however, the target of IKKβ in this process is unknown [101]. In response to NLRP3-activating stimuli, diacylglycerol at the Golgi is induced, recruiting protein kinase D (PKD), which phosphorylates NLRP3 at S295 and is sufficient to release NLRP3 from mitochondria-associated ER membranes and promotes the assembly of the active inflammasome [102]. However, phosphorylation of NLRP3 at S295 by PKA inhibits NLRP3 activation [87, 88]. Further studies are needed to understand how phosphorylation at the same residue of NLRP3 results in opposite functional outcomes.

Concluding remarks

A full understanding of NLRP3 activation has been hampered by the fact that NLRP3-activating stimuli often induce intracellular signals that perturb cellular homeostasis of cellular ions, organelles and metabolism in addition to NLRP3 activation. Thus, it has been challenging to determine whether signaling events or perturbations are necessary or act in parallel to NLRP3 activation. Moreover, NLRP3 activation often displays cell-type and inter-species variation, adding more complexity to the system. Recent advances including Cryo-EM structures of NLRP3, identification of the NEK7-NLRP3 interaction and the possible role of organelle homeostasis in NLRP3 activation have fueled progress in the NLRP3 inflammasome field. The recent structural studies of inactive oligomeric NLRP3 are important in that they provide a basis for rational drug development to target the inflammasome. NLRP3 has been shown to localize to several organelles and transition to different intracellular sites during activation. The newly discovered link between NLRP3 activation, the Golgi and endosomes is exciting, but it needs further verification and analysis. So far, with few exceptions, K+ efflux is the most established cellular signal for NLRP3 activation. Despite certain advances, the mechanism by which K+ efflux triggers NLRP3 activation remains obscure. Further investigation in the field is still needed with the ultimate goal of identifying unified mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation (see Outstanding questions).

Outstanding Questions.

What is the structural organization of the active NLRP3 inflammasome?

In addition to NEK7 binding, what events are required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation?

What are the components and the mechanism of activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in human cells and in vivo?

What is the main pathway leading to NLRP3 activation in response to microbial stimuli in vivo?

How are intracellular K+ levels sensed to induce the activation of NLRP3?

How are NLRP3 and ASC transported to converge into the ASC speck for inflammasome assembly and activation?

What is the main intracellular organelle involved in NLRP3 activation?

What is the role of the mitochondria in NLRP3 activation?

Highlights.

The NLRP3 inflammasome, a critical component of the host innate immune system, plays an important role in microbial infection, but its aberrant activation causes inherited disorders and contributes to sporadic inflammatory diseases.

At steady state, the structure of NLRP3 is oligomeric and kept in an inactive form through interactions among the C-terminal LRR domains. In response to specific stimuli, NLRP3 forms a supramolecular complex called the inflammasome that activates caspase-1 leading to the release of IL-1β and IL-18.

The NLRP3 inflammasome senses the disturbance of intracellular homeostasis induced by a wide array of stimuli that converge into K+ efflux, which is critical for NLRP3 activation.

Localization of NLRP3 to the dispersed trans-Golgi network has been suggested to play an important role in NLRP3 activation.

Post-translational modifications regulate the NLRP3 inflammasome at both priming and activation steps.

Acknowledgements

We thank Grace Chen and Joseph Pickard for critical review of the manuscript and Joseph Pickard for help with Figure 1. We apologize to our colleagues whose work was not cited because of space and reference number limitations. The work on the NLRP3 inflammasome in the Núñez laboratory is funded by NIH grant R37 A1 063331.

Glossary

- Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)

circular DNA found inside mitochondria rather than the nucleus.

- Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mtROS)

highly reactive chemicals or radicals, produced from O2 by the mitochondrial electron transport chain during oxidative phosphorylation.

- NOD-like receptors (NLRs)

also known as nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain and leucine rich repeat-containing proteins, a family of intracellular pattern recognition receptors that sense microbial molecules or homeostatic cellular perturbation.

- Priming signal

pre-stimulation with microbial molecules, such as lipopolysaccharide or pro-inflammatory cytokines, to induce pro-IL-1β and to facilitate NLRP3 activation.

- Pyroptosis

a form of lytic cell death that is induced by caspases and associated with cytokine release.

- Toll-like receptors (TLRs)

a group of membrane-bound pattern recognition receptors that bind microbial molecules, such as lipopolysaccharide produced by many microbes. Upon binding, TLRs are activated and initiate signaling pathways leading to pro-inflammatory and anti-microbial responses.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Li D and Wu M (2021) Pattern recognition receptors in health and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 6 (1), 291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He Y et al. (2016) Mechanism and Regulation of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Trends Biochem Sci 41 (12), 1012–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swanson KV et al. (2019) The NLRP3 inflammasome: molecular activation and regulation to therapeutics. Nat Rev Immunol 19 (8), 477–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mangan MSJ et al. (2018) Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 17 (8), 588–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma BR and Kanneganti TD (2021) NLRP3 inflammasome in cancer and metabolic diseases. Nat Immunol 22 (5), 550–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharif H et al. (2019) Structural mechanism for NEK7-licensed activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. Nature 570 (7761), 338–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He Y et al. (2016) NEK7 is an essential mediator of NLRP3 activation downstream of potassium efflux. Nature 530 (7590), 354–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmid-Burgk JL et al. (2016) A Genome-wide CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) Screen Identifies NEK7 as an Essential Component of NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. J Biol Chem 291 (1), 103–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi H et al. (2016) NLRP3 activation and mitosis are mutually exclusive events coordinated by NEK7, a new inflammasome component. Nat Immunol 17 (3), 250–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmacke NA et al. (2019) Priming enables a NEK7-independent route of NLRP3 activation. bioRxiv, 799320. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gangopadhyay A et al. (2022) NLRP3 licenses NLRP11 for inflammasome activation in human macrophages. Nat Immunol 23 (6), 892–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duan Y et al. (2020) RACK1 Mediates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Promoting NLRP3 Active Conformation and Inflammasome Assembly. Cell Rep 33 (7), 108405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andreeva L et al. (2021) NLRP3 cages revealed by full-length mouse NLRP3 structure control pathway activation. Cell 184 (26), 6299–6312 e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochheiser IV et al. (2022) Structure of the NLRP3 decamer bound to the cytokine release inhibitor CRID3. Nature 604 (7904), 184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohto U et al. (2022) Structural basis for the oligomerization-mediated regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119 (11), e2121353119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hafner-Bratkovic I et al. (2018) NLRP3 lacking the leucine-rich repeat domain can be fully activated via the canonical inflammasome pathway. Nat Commun 9 (1), 5182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahman T et al. (2020) NLRP3 Sensing of Diverse Inflammatory Stimuli Requires Distinct Structural Features. Front Immunol 11, 1828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bauernfeind FG et al. (2009) Cutting edge: NF-kappaB activating pattern recognition and cytokine receptors license NLRP3 inflammasome activation by regulating NLRP3 expression. J Immunol 183 (2), 787–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Franchi L et al. (2009) Cutting edge: TNF-alpha mediates sensitization to ATP and silica via the NLRP3 inflammasome in the absence of microbial stimulation. J Immunol 183 (2), 792–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munoz-Planillo R et al. (2013) K(+) efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity 38 (6), 1142–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gross CJ et al. (2016) K(+) Efflux-Independent NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Small Molecules Targeting Mitochondria. Immunity 45 (4), 761–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf AJ et al. (2016) Hexokinase Is an Innate Immune Receptor for the Detection of Bacterial Peptidoglycan. Cell 166 (3), 624–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaidt MM et al. (2016) Human Monocytes Engage an Alternative Inflammasome Pathway. Immunity 44 (4), 833–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di A et al. (2018) The TWIK2 Potassium Efflux Channel in Macrophages Mediates NLRP3 Inflammasome-Induced Inflammation. Immunity 49 (1), 56–65 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tapia-Abellan A et al. (2021) Sensing low intracellular potassium by NLRP3 results in a stable open structure that promotes inflammasome activation. Sci Adv 7 (38), eabf4468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schorn C et al. (2011) Sodium overload and water influx activate the NALP3 inflammasome. J Biol Chem 286 (1), 35–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang T et al. (2017) CLICs-dependent chloride efflux is an essential and proximal upstream event for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nat Commun 8 (1), 202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Domingo-Fernandez R et al. (2017) The intracellular chloride channel proteins CLIC1 and CLIC4 induce IL-1beta transcription and activate the NLRP3 inflammasome. J Biol Chem 292 (29), 12077–12087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayes-Hopfinger L et al. (2021) Chloride sensing by WNK1 regulates NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis. Nat Commun 12 (1), 4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Green JP et al. (2018) Chloride regulates dynamic NLRP3-dependent ASC oligomerization and inflammasome priming. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115 (40), E9371–E9380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murakami T et al. (2012) Critical role for calcium mobilization in activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109 (28), 11282–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee GS et al. (2012) The calcium-sensing receptor regulates the NLRP3 inflammasome through Ca2+ and cAMP. Nature 492 (7427), 123–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katsnelson MA et al. (2015) K+ efflux agonists induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation independently of Ca2+ signaling. J Immunol 194 (8), 3937–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Subramanian N et al. (2013) The adaptor MAVS promotes NLRP3 mitochondrial localization and inflammasome activation. Cell 153 (2), 348–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iyer SS et al. (2013) Mitochondrial cardiolipin is required for Nlrp3 inflammasome activation. Immunity 39 (2), 311–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ichinohe T et al. (2013) Mitochondrial protein mitofusin 2 is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation after RNA virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110 (44), 17963–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen J and Chen ZJ (2018) PtdIns4P on dispersed trans-Golgi network mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 564 (7734), 71–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Franchi L et al. (2014) Cytosolic double-stranded RNA activates the NLRP3 inflammasome via MAVS-induced membrane permeabilization and K+ efflux. J Immunol 193 (8), 4214–4222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou R et al. (2011) A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 469 (7329), 221–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Billingham LK et al. (2022) Mitochondrial electron transport chain is necessary for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol 23 (5), 692–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimada K et al. (2012) Oxidized mitochondrial DNA activates the NLRP3 inflammasome during apoptosis. Immunity 36 (3), 401–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhong Z et al. (2018) New mitochondrial DNA synthesis enables NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 560 (7717), 198–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakahira K et al. (2011) Autophagy proteins regulate innate immune responses by inhibiting the release of mitochondrial DNA mediated by the NALP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol 12 (3), 222–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yissachar N et al. (2006) Nek7 kinase is enriched at the centrosome, and is required for proper spindle assembly and mitotic progression. FEBS Lett 580 (27), 6489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang XD et al. (2020) PLK4 deubiquitination by Spata2-CYLD suppresses NEK7-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation at the centrosome. EMBO J 39 (2), e102201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Magupalli VG et al. (2020) HDAC6 mediates an aggresome-like mechanism for NLRP3 and pyrin inflammasome activation. Science 369 (6510). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li X et al. (2017) MARK4 regulates NLRP3 positioning and inflammasome activation through a microtubule-dependent mechanism. Nat Commun 8, 15986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo C et al. (2018) Cholesterol Homeostatic Regulator SCAP-SREBP2 Integrates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Cholesterol Biosynthetic Signaling in Macrophages. Immunity 49 (5), 842–856 e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chapman RE and Munro S (1994) Retrieval of TGN proteins from the cell surface requires endosomal acidification. EMBO J 13 (10), 2305–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reaves B and Banting G (1994) Vacuolar ATPase inactivation blocks recycling to the trans-Golgi network from the plasma membrane. FEBS Lett 345 (1), 61–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee B et al. (2021) NLRP3 activation in response to disrupted endocytic traffic. bioRxiv, 2021.09.15.460426. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Z et al. (2021) Defective endosome-TGN retrograde transport promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation. bioRxiv, 2021.09.14.460331. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hornung V et al. (2008) Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat Immunol 9 (8), 847–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Orlowski GM et al. (2015) Multiple Cathepsins Promote Pro-IL-1beta Synthesis and NLRP3-Mediated IL-1beta Activation. J Immunol 195 (4), 1685–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rashidi M et al. (2019) The Pyroptotic Cell Death Effector Gasdermin D Is Activated by Gout-Associated Uric Acid Crystals but Is Dispensable for Cell Death and IL-1beta Release. J Immunol 203 (3), 736–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de la Roche M et al. (2018) Trafficking of cholesterol to the ER is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Cell Biol 217 (10), 3560–3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vyleta ML et al. (2012) Suppression of ribosomal function triggers innate immune signaling through activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. PLoS One 7 (5), e36044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Briard B et al. (2020) Galactosaminogalactan activates the inflammasome to provide host protection. Nature 588 (7839), 688–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van den Bossche J et al. (2015) Metabolic Characterization of Polarized M1 and M2 Bone Marrow-derived Macrophages Using Real-time Extracellular Flux Analysis. J Vis Exp (105). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moon JS et al. (2015) mTORC1-Induced HK1-Dependent Glycolysis Regulates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Cell Rep 12 (1), 102–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 61.Xie M et al. (2016) PKM2-dependent glycolysis promotes NLRP3 and AIM2 inflammasome activation. Nat Commun 7, 13280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sanman LE et al. (2016) Disruption of glycolytic flux is a signal for inflammasome signaling and pyroptotic cell death. Elife 5, e13663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Palmieri EM et al. (2020) Nitric oxide orchestrates metabolic rewiring in M1 macrophages by targeting aconitase 2 and pyruvate dehydrogenase. Nat Commun 11 (1), 698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tannahill GM et al. (2013) Succinate is an inflammatory signal that induces IL-1beta through HIF-1alpha. Nature 496 (7444), 238–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Humphries F et al. (2020) Succination inactivates gasdermin D and blocks pyroptosis. Science 369 (6511), 1633–1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Michelucci A et al. (2013) Immune-responsive gene 1 protein links metabolism to immunity by catalyzing itaconic acid production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110 (19), 7820–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lampropoulou V et al. (2016) Itaconate Links Inhibition of Succinate Dehydrogenase with Macrophage Metabolic Remodeling and Regulation of Inflammation. Cell Metab 24 (1), 158–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hooftman A et al. (2020) The Immunomodulatory Metabolite Itaconate Modifies NLRP3 and Inhibits Inflammasome Activation. Cell Metab 32 (3), 468–478 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bambouskova M et al. (2021) Itaconate confers tolerance to late NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Rep 34 (10), 108756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wen H et al. (2011) Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol 12 (5), 408–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moon JS et al. (2015) UCP2-induced fatty acid synthase promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation during sepsis. J Clin Invest 125 (2), 665–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 72.Moon JS et al. (2016) NOX4-dependent fatty acid oxidation promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages. Nat Med 22 (9), 1002–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 73.Youm YH et al. (2015) The ketone metabolite beta-hydroxybutyrate blocks NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammatory disease. Nat Med 21 (3), 263–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Han S et al. (2015) Lipopolysaccharide Primes the NALP3 Inflammasome by Inhibiting Its Ubiquitination and Degradation Mediated by the SCFFBXL2 E3 Ligase. J Biol Chem 290 (29), 18124–18133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yan Y et al. (2015) Dopamine controls systemic inflammation through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome. Cell 160 (1–2), 62–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Song H et al. (2016) The E3 ubiquitin ligase TRIM31 attenuates NLRP3 inflammasome activation by promoting proteasomal degradation of NLRP3. Nat Commun 7, 13727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tang J et al. (2020) Sequential ubiquitination of NLRP3 by RNF125 and Cbl-b limits inflammasome activation and endotoxemia. J Exp Med 217 (4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang D et al. (2021) YAP promotes the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome via blocking K27-linked polyubiquitination of NLRP3. Nat Commun 12 (1), 2674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wan P et al. (2019) Cullin1 binds and promotes NLRP3 ubiquitination to repress systematic inflammasome activation. FASEB J 33 (4), 5793–5807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kawashima A et al. (2017) ARIH2 Ubiquitinates NLRP3 and Negatively Regulates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Macrophages. J Immunol 199 (10), 3614–3622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Humphries F et al. (2018) The E3 ubiquitin ligase Pellino2 mediates priming of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat Commun 9 (1), 1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ni J et al. (2021) Ubc13 Promotes K63-Linked Polyubiquitination of NLRP3 to Activate Inflammasome. J Immunol 206 (10), 2376–2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Song H et al. (2020) UAF1 deubiquitinase complexes facilitate NLRP3 inflammasome activation by promoting NLRP3 expression. Nat Commun 11 (1), 6042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Py BF et al. (2013) Deubiquitination of NLRP3 by BRCC3 critically regulates inflammasome activity. Mol Cell 49 (2), 331–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ren G et al. (2019) ABRO1 promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation through regulation of NLRP3 deubiquitination. EMBO J 38 (6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Palazon-Riquelme P et al. (2018) USP7 and USP47 deubiquitinases regulate NLRP3 inflammasome activation. EMBO Rep 19 (10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Guo C et al. (2016) Bile Acids Control Inflammation and Metabolic Disorder through Inhibition of NLRP3 Inflammasome. Immunity 45 (4), 802–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mortimer L et al. (2016) NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition is disrupted in a group of auto-inflammatory disease CAPS mutations. Nat Immunol 17 (10), 1176–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang A et al. (2020) EphA2 phosphorylates NLRP3 and inhibits inflammasomes in airway epithelial cells. EMBO Rep 21 (7), e49666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhao W et al. (2020) AKT Regulates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation by Phosphorylating NLRP3 Serine 5. J Immunol 205 (8), 2255–2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Malireddi RKS et al. (2018) TAK1 restricts spontaneous NLRP3 activation and cell death to control myeloid proliferation. J Exp Med 215 (4), 1023–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dufies O et al. (2021) Escherichia coli Rho GTPase-activating toxin CNF1 mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation via p21-activated kinases-1/2 during bacteraemia in mice. Nat Microbiol 6 (3), 401–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stutz A et al. (2017) NLRP3 inflammasome assembly is regulated by phosphorylation of the pyrin domain. J Exp Med 214 (6), 1725–1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fischer FA et al. (2021) TBK1 and IKKepsilon act like an OFF switch to limit NLRP3 inflammasome pathway activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118 (38). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Spalinger MR et al. (2016) NLRP3 tyrosine phosphorylation is controlled by protein tyrosine phosphatase PTPN22. J Clin Invest 126 (5), 1783–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Huang Y et al. (2020) Myeloid PTEN promotes chemotherapy-induced NLRP3-inflammasome activation and antitumour immunity. Nat Cell Biol 22 (6), 716–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Song N et al. (2017) NLRP3 Phosphorylation Is an Essential Priming Event for Inflammasome Activation. Mol Cell 68 (1), 185–197 e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Niu T et al. (2021) NLRP3 phosphorylation in its LRR domain critically regulates inflammasome assembly. Nat Commun 12 (1), 5862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ito M et al. (2015) Bruton’s tyrosine kinase is essential for NLRP3 inflammasome activation and contributes to ischaemic brain injury. Nat Commun 6, 7360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bittner ZA et al. (2021) BTK operates a phospho-tyrosine switch to regulate NLRP3 inflammasome activity. J Exp Med 218 (11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Nanda SK et al. (2021) IKKbeta is required for the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. EMBO Rep 22 (10), e50743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang Z et al. (2017) Protein kinase D at the Golgi controls NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Exp Med 214 (9), 2671–2693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Matikainen S et al. (2020) Function and Regulation of Noncanonical Caspase-4/5/11 Inflammasome. J Immunol 204 (12), 3063–3069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yang D et al. (2015) Caspase-11 Requires the Pannexin-1 Channel and the Purinergic P2X7 Pore to Mediate Pyroptosis and Endotoxic Shock. Immunity 43 (5), 923–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.He Y et al. (2013) TLR agonists stimulate Nlrp3-dependent IL-1beta production independently of the purinergic P2X7 receptor in dendritic cells and in vivo. J Immunol 190 (1), 334–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Netea MG et al. (2009) Differential requirement for the activation of the inflammasome for processing and release of IL-1beta in monocytes and macrophages. Blood 113 (10), 2324–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zewinger S et al. (2020) Apolipoprotein C3 induces inflammation and organ damage by alternative inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol 21 (1), 30–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kuriakose T et al. (2016) ZBP1/DAI is an innate sensor of influenza virus triggering the NLRP3 inflammasome and programmed cell death pathways. Sci Immunol 1 (2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Barry R et al. (2018) SUMO-mediated regulation of NLRP3 modulates inflammasome activity. Nat Commun 9 (1), 3001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Qin Y et al. (2021) TRIM28 SUMOylates and stabilizes NLRP3 to facilitate inflammasome activation. Nat Commun 12 (1), 4794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Shao L et al. (2020) SUMO1 SUMOylates and SENP3 deSUMOylates NLRP3 to orchestrate the inflammasome activation. FASEB J 34 (1), 1497–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zhao K et al. (2019) Acetylation is required for NLRP3 self-aggregation and full activation of the inflammasome. bioRxiv, 2019.12.31.891556. [Google Scholar]

- 113.He M et al. (2020) An Acetylation Switch of the NLRP3 Inflammasome Regulates Aging-Associated Chronic Inflammation and Insulin Resistance. Cell Metab 31 (3), 580–591 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]