Abstract

Background

Predictors of poor outcome associated with variceal bleeding remain suboptimal. In patients with cirrhosis, serum lactate combined with Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD-LA) improved prediction across heterogeneous populations. However, prognostic properties have not yet been assessed in the context of variceal bleeding.

Aims

We aimed to evaluate the predictive performance of MELD-LA compared to MELD, lactate, and nadir hemoglobin in cirrhosis patients with variceal bleeding.

Methods

In this multicenter study, we identified 472 patients with variceal bleeding from a German primary cohort (University Hospitals Hamburg/Frankfurt/Cologne), and two independent external validation cohorts [Veterans Affairs (VA), Baylor University]. Discrimination for 30-day mortality was analyzed and scores were compared. MELD-LA was evaluated separately in validation cohorts to ensure consistency of findings.

Results

In contrast to nadir hemoglobin, MELD and peak-lactate at time of bleeding were significantly higher in 30-day non-survivors in the primary cohort (p = 0.708; p < 0.001). MELD-LA had excellent discrimination for 30-day mortality (AUROC 0.82, 95% CI 0.76–0.88), better than MELD and peak-lactate (AUROC 0.78, 95% CI 0.71–0.84; AUROC 0.73, 95% CI 0.66–0.81). MELD-LA predicted 30-day mortality independently of age, sex, severity of liver disease and vasopressor support (HR 1.29 per 1-point-increase of MELD-LA; 95% CI 1.19–1.41; p < 0.001). Similarly, MELD-LA demonstrated excellent discrimination for 30-day mortality in the VA (AUROC = 0.86, 95% CI 0.79–0.93) and Baylor cohort (AUROC = 0.85, 95% CI 0.74–0.95).

Conclusions

MELD-LA significantly improves discrimination of short-term mortality associated with variceal bleeding, compared to MELD, peak-lactate and nadir hemoglobin. Thus, MELD-LA might represent a useful and objective marker for risk assessment and therapeutic intervention in patients with variceal bleeding.

Keywords: Variceal bleeding, GI bleeding, Cirrhosis, MELD-lactate

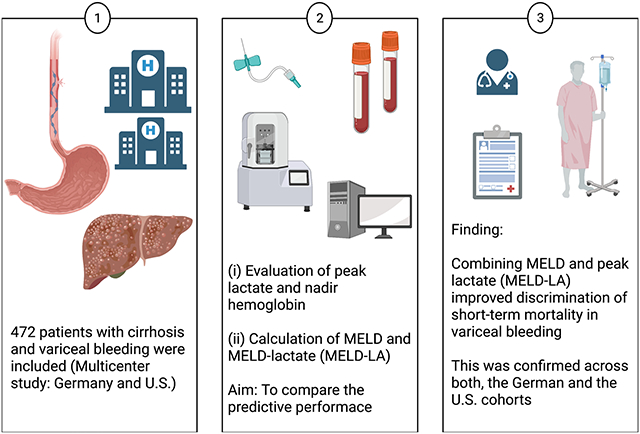

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Variceal bleeding is a frequent and severe cause of acute upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding in patients with cirrhosis, causing up to 70% of bleeding episodes in the context of portal hypertension [1-3]. Esophageal varices are found in more than two thirds of patients with advanced cirrhosis, Child–Turcotte–Pugh (CTP), class B/C [2, 4]. Moreover, upper GI and variceal bleeding are associated with increased mortality and risk of rebleeding [2, 5] with reported mortality rates of 25% within in the first 6 weeks and 40% within 1 year of the episode [6].

In daily clinical routine, hemoglobin levels are often used to rate severity of bleeding events, as low hemoglobin levels have been associated with upper GI bleeding [7]. However, with acute blood loss, both corpuscular and plasma blood components are depleted, and this approach appears to offer an unreliable predictor of bleeding mortality.

Lactate is a widely accepted marker of tissue hypoperfusion and hypoxia. Elevated serum lactate levels are the consequence of increased lactate production or reduced clearance, mainly due to mitochondrial dysfunction [8]. Serum lactate is used as a marker for severity of disease and organ failure in patients with cirrhosis in the intensive care unit and independently predicts short-term mortality in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure [9]. Until now, however, the impact of lactate and its prognostic properties have not been studied in patients with cirrhosis presenting with variceal bleeding. The incorporation of lactate into the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score (MELD-LA) predicts survival in cirrhosis better than MELD or MELD-Na alone across heterogeneous populations.[10, 11].

To address this, we aimed to evaluate the predictive performance of serum lactate and MELD-LA compared to MELD and hemoglobin in patients with cirrhosis presenting with variceal bleeding in a primary German cohort, and to confirm MELD-LA prediction performance in two external independent U.S. validation cohorts.

Patients and Methods

Patients

In this retrospective multicenter study, we evaluated patients with cirrhosis who presented with variceal bleeding between 2009 and 2018. The primary cohort included 232 patients from Germany (University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (n = 129), University Hospital Frankfurt (n = 76), and University Hospital Cologne (n = 27). Additionally, two external independent validation cohorts were comprised of 240 patients from the U.S. (n = 154 patients from the Veterans Affairs (VA) Hospital Systems and n = 86 patients from Baylor University). See study flow chart (Suppl. Figure 1).

Diagnosis of cirrhosis was established by liver histology or combination of typical clinical signs (presence of ascites) together with typical laboratory or radiologic findings (signs of cirrhosis/portal hypertension on abdominal ultrasonography/CT-scan). Inclusion criteria were presence of cirrhosis, variceal bleeding, available serum lactate values and age > 18 years. Patients in the primary cohort were identified by detailed chart review. Variceal bleeding was endoscopically confirmed in the German cohort and via International Classification of Diseases (ICD9-CM: 571.2, 571.5, 571.6; ICD10-CM: K74, K70.3) in the U.S. cohorts [12]. In order to ensure consistency of diagnoses, chart review was performed in subsets of patients to validate the diagnosis.

In the primary cohort, peak serum lactate, nadir hemoglobin levels and endoscopic characteristics were obtained in all patients. Peak serum lactate and nadir hemoglobin levels were obtained at admission, or within 24 h of admission, but prior to endoscopy. MELD score and MELD-LA score (formula: 0.251 + 5.257 × square root (LA) + 0.338 × MELD) were calculated and analyzed [10]. Initial hemodynamics (including need for vasopressor support), severity of disease and comorbidities (CTP, MELD, Charlson comorbidity index [13]) were analyzed. The prognostic properties (AUROC) of the MELD-LA for 30-day and in-hospital mortality were separately evaluated in the U.S. cohorts to ensure consistency of findings.

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and regulations of the local ethics committee of Hamburg (WF-63/16). The Baylor university cohort was approved by the local institutional review board, the VA study by the Institutional Review Board of the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were described as median and 25–75% interquartile range (IQR), and for categorical variables, absolute and relative numbers were presented. Continuous variables were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test and categorical variables were compared using chi-square tests. The overall diagnostic test accuracy was assessed by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves as summarized by the AUROC. In order to assess the performance of the prediction model, calibration curves (plotting observed versus predicted events) were performed, consistent with recommended best practices [14]. Estimates of diagnostic test accuracy (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and likelihood-ratios) were calculated using standard methods. Youden J statistics providing the optimal cut-off between sensitivity and specificity was calculated. To investigate the impact of variables on the time to death over 30 days from the time of hospitalization, Cox proportional hazards models were fit. For data management and analyses we used MS Excel 2008 for Mac (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA), SPSS 27 for Mac (SPSS, Inc. Chicago, IL), and STATA 15.1/IC (College Station, TX). All p values reported are two-sided and p < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

Study Populations

This observational international cohort study included 472 patients with liver cirrhosis presenting with variceal bleeding. Of these, 232 patients were included in the primary (German) cohort, whereas the external independent U.S. validation cohorts included 240 patients.

Primary cohort: Lactate levels compared to hemoglobin, MELD and MELD-LA.

Patients Characteristics and Endoscopic Features in the Primary German Cohort

Seventy percent of patients were male, and the median age was 56 (IQR 48–63). The most common cause of cirrhosis was alcohol-related liver disease (ALD, 50%) followed by viral hepatitis C infection (15%), combination of ALD and viral hepatitis (11%), cryptogenic (8%), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (4%) and others (see Table 1). A total of 19 patients (9%) were classified as CTP class A, 104 (48%) as CTP B and 92 (43%) as CTP C (CTP score could not be calculated in 17 patients due to missing data). The median MELD score at admission was 17 (IQR 12–23). Median nadir hemoglobin prior to endoscopy was 7.6 g/dl (IQR 6.5–8.8), median peak serum lactate was 2.7 mmol/l (IQR 1.7–5.6). (Serum lactate levels > 2 mmol/L are considered elevated). In the primary cohort, the rate of ICU admission was 85% [Hamburg 97/129 (75%), Cologne 25/27 (93%), Frankfurt 76/76 (100%)]. Table 1 shows detailed demographic and clinical characteristics.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of the German primary cohort

| Parameter | Overall (n = 232) |

|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 72 (31) |

| Age (years) | 56 (48–63) |

| Etiology of cirrhosis | |

| Alcoholic liver disease, n (%) | 115 (50) |

| HCV, n (%) | 35 (15) |

| Alcohol + viral, n (%) | 26 (11) |

| PSC, n (%) | 6 (3) |

| NAFLD, n (%) | 10 (4) |

| AIH, n (%) | 6 (3) |

| PBC, n (%) | 3 (1) |

| Cryptogenic | 19 (8) |

| Others | 10 (4) |

| Child–Turcotte–Pugh classification* | |

| A, n (%) | 19 (9) |

| B, n (%) | 104 (48) |

| C, n (%) | 92 (43) |

| MELD score | 17 (12–23) |

| MELD-LA score | 13 (11–16) |

| Charlson comorbidity index# | 5 (4–8) |

| Serum laboratory parameters | |

| Nadir hemoglobin (g/dl) | 7.6 (6.5–8.8) |

| Lactate (mmol/l) | 2.7 (1.7–5.6) |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.1 (0.8–1.9) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 2.4 (1.1–4.8) |

| INR | 1.5 (1.3–1.8) |

| Platelets (G/l) | 93 (60–140) |

| Albumin (g/l)+ | 24 (20–31) |

| MAP (mmHg) | 73 (63–87) |

| Heart rate (bpm)° | 94 (81–110) |

| Vasopressor support, n (%) | 124 (53) |

Data are shown as absolute numbers and percentage or as median with IQR

HCV hepatitis C virus infection, PSC primary sclerosing cholangitis, NAFLD nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, AIH autoimmune hepatitis, PBC primary biliary cholangitis, INR international normalized ratio, MAP mean arterial blood pressure, bpm beats per minute

Data available in 215 patients

n = 142

n = 209

n = 152

Out of 232 patients, a total of 193 (83%) had esophageal variceal bleeding, 21 (9%) had endoscopic variceal ligation-induced ulcer bleeding, 14 patients (6%) had bleeding from isolated gastric (fundus) varices, 2 patients (1%) from gastroesophageal varices type II and 2 patients (1%) from duodenal varices. A total of 179 patients (77%) received transfusion of blood products. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy required intubation in 111 patients (48%). Mean arterial blood pressure was 73 mmHg (IQR 63–87) and 53% of patients received vasopressor support (such as epinephrine or norepinephrine).

In the primary cohort 26 of 232 (11%) patients received a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) implantation directly after endoscopic intervention or within 5 days after the bleeding event. The proportion of patients receiving a TIPS was comparable within the German centers, Hamburg 16/129 (12%), Cologne 3/27 (11%), Frankfurt 7/76 (9%). Mortality rates were slightly lower, in those individuals receiving a TIPS compared to those who did not (30-day mortality 30% vs 32%, p = n.s.; 90-day mortality 31% vs 39%, p = n.s.; 1-year mortality 32% vs 47%, p = n.s.).

Lactate, MELD, Hemoglobin Levels and Patient Outcomes

Among the individuals included in the primary cohort, 30-day and 90-day mortality was 31% and 39%, respectively. While MELD and peak serum lactate levels at time of bleeding were significantly higher in 30-day non-survivors compared to survivors [median lactate 5.1 mmol/l (IQR 2.3–11.6) vs. 2.3 mmol/l (IQR 1.6–3.7), p < 0.001; MELD 22 (IQR 17–32) vs. 14 (IQR 11–20), p < 0.001], nadir hemoglobin levels did not differ between groups [median 7.6 g/dl (IQR 6.7–8.6) vs. 7.7 g/dl (6.5–8.9), p = 0.708]. In the primary cohort, 47% of patients who died within 1-year, died of sepsis/septic shock, 19% in association with bleeding/hemorrhagic shock, 10% due to progress of malignant disease (mainly HCC), and 23% due to others (such as hepatic decompensation with unclear trigger).

Predictive Performance of MELD-LA in the Primary Cohort

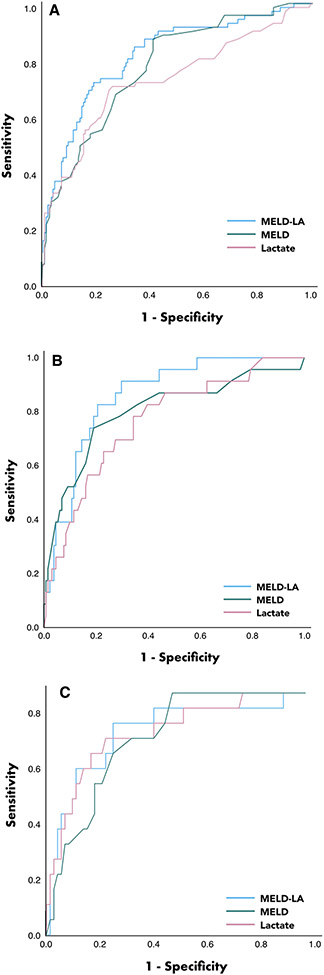

MELD-LA displayed excellent discrimination for 30-day mortality (AUROC 0.82, 95% CI 0.76–0.88), whereas MELD and peak-lactate had good discrimination (AUROC 0.78, 95% CI 0.71–0.84; AUROC 0.73, 95% CI 0.66–0.81, respectively) (see Fig. 1A). MELD-LA was well-calibrated by visual inspection (Supplementary Fig. 2A).

Fig. 1.

A–C Receiver operating curve analysis in prediction of 30-day mortality. Receiver operating curve analysis of MELD-LA, MELD and peak serum lactate and in prediction of 30-day mortality in the primary German validation cohort (A), the VA validation cohort (B) and the Baylor cohort (C) (MELD model for endstage liver disease, MELD-LA incorporation of serum lactate into the MELD score)

Youden index identified MELD-LA > 14.4 as best cut-off for discriminating between 30-day survivors and non-survivors, with a sensitivity of 71%, a specificity of 81%, positive predictive value of 62% and a negative predictive value of 86%. Detailed predictive performance of tested parameters is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Performance in prediction of 30-day mortality in the German primary validation cohort

| Parameter | AUROC | 95% CI | Cut-off | Sens. (%) | Spec. (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactate | 0.73 | 0.66–0.81 | > 3.5 | 71 | 74 | 55 | 85 |

| MELD | 0.78 | 0.71–0.84 | > 15 | 88 | 58 | 49 | 91 |

| MELD-LA | 0.82 | 0.76–0.88 | > 14.4 | 71 | 81 | 62 | 86 |

Discriminative ability of MELD-LA in the primary German cohort

AUROC area under ROC curve, CI confidence interval, Sens. Sensitivity, Spec. Specificity Cut-offs were identified via the Youden-Index

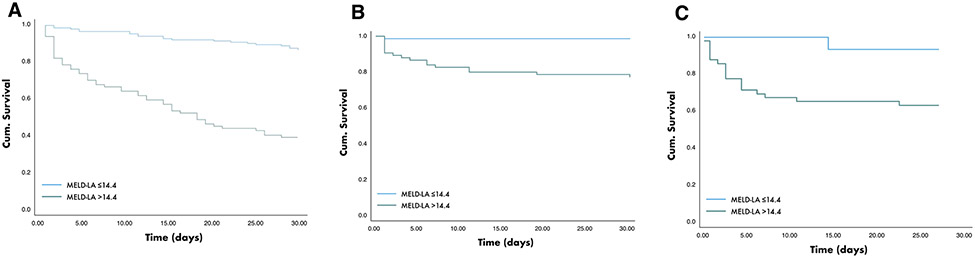

MELD-LA predicted time to death over 30-days independent of age, sex, severity of underlying liver disease (CTP points), necessity of vasopressor support and independent of the study site (Cox hazard regression: HR 1.29 per 1-point increase of MELD-LA; 95% CI 1.19–1.41; p < 0.001). MELD-LA score at a cut-off > 14.4 predicted 30-day mortality with a HR of 6.68 (95% CI 4.00–11.14; p < 0.001). The 30-day mortality rate was significantly higher in patients with MELD-LA > 14.4 compared to those with MELD-LA ≤ 14.4 (71% vs. 29%; log rank test: p < 0.001). Kaplan Meier survival analysis for 30-day mortality is shown in Fig. 2A.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan Meier curve. 30-day mortality rate was significantly higher in patients with MELD-LA > 14.4 compared to those with MELD-LA ≤ 14.4; A in the German primary cohort; B in the VA population and C the Baylor cohort

Validation of MELD-LA in Predicting Outcome in Two Independent External Cohorts

Patient characteristics of the two independent U.S. cohorts are shown in Table 3, respectively. In the Baylor cohort 35/86 patients (41%) were treated in the ICU following the bleeding and endoscopy procedure.

Table 3.

Patient characteristics of the VA and Baylor validation cohort

| Parameter | Veterans’ affairs cohort Value (N = 154) |

Baylor cohort Value (n = 86) |

|---|---|---|

| Female, n (%) | 2 (1) | 37 (43) |

| Age (years) | 57 (53–61) | 56 (50–62) |

| Etiology of cirrhosis | ||

| Viral hepatitis, n (%) | 5 (6) | |

| HCV, n (%) | 13 (8) | |

| Hepatitis B virus, n (%) | 6 (4) | |

| ALD, n (%) | 74 (48) | 79 (92) |

| HCV + ALD, n (%) | 50 (33) | |

| NAFLD, n (%) | 8 (5) | |

| Other, n (%) | 3 (2) | |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index | n.a | 6 (5–8) |

| Serum laboratory parameters | ||

| Sodium (mmol/l) | 136 (133–139) | n.a |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 1.3 (0.9–1.7) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 1.9 (1.1–3.3) | 2.5 (1.4–4.9) |

| INR | 1.4 (1.3–1.7) | 1.6 (1.3–2.0) |

| Platelets (G/l) | n.a | 16.4 (13.5–21.3) |

| MELD score | 15 (11–18) | 18 (13–24) |

| Lactate (mmol/l) | 2.85 (1.8–4.7) | 2.7 (1.7–5.8) |

| Nadir hemoglobin (g/dl) | n.a | n.a |

| MELD-LA score | 15 (12–19) | 17 (12–21) |

Data are shown as absolute numbers and percentage or as median with IQR

HCV hepatitis C virus infection, HBV hepatitis B virus infection, ALD alcoholic liver disease, NAFLD nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, INR international normalized ratio, n.a. not available (Further details are shown in the Supplementary Table)

The 30-day mortality was 14.9% and 90-day mortality was 20.8% in the VA population, whereas in the Baylor cohort, 30-day mortality was 20%, and 90-day mortality was 21.4%.

Like in the primary cohort, MELD-LA demonstrated excellent discrimination for 30-day mortality from the time of variceal bleeding across both U.S. cohorts. The AUROC for 30-day mortality in the VA population was 0.86 (95% CI 0.79–0.93), as illustrated in Fig. 1B. In the Baylor cohort, AUROC of MELD-LA for predicting 30-day mortality was 0.85 (95% CI 0.74–0.95), as shown in Fig. 1C.

A MELD-LA score > 14.4 predicted 30-day mortality with a HR 18.29 (95% CI 2.43–137.50, p = 0.005) in the VA population and a HR of 9.37 (95% CI 1.24–71.25; p < 0.001) in the Baylor cohort, respectively, though the numbers were lower. As in the primary cohort, MELD-LA was generally well calibrated by visual inspection in the external cohorts (Supplementary Fig. 1B/C).

Furthermore, MELD-LA showed excellent discrimination for prediction of in-hospital mortality in both, the national VA population (AUROC = 0.87, 95% CI 0.79–0.95) and the large urban Baylor cohort (AUROC = 0.87, 95% CI 0.78–0.97). Kaplan Meier survival analysis for 30-day mortality of the VA and Baylor population is shown in Fig. 2B and C.

Discussion

Acute variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis is associated with high morbidity and mortality [3, 15]. The established prognosis scores Child Pugh and MELD have been shown to predict mortality specifically in AVB to some extent [16, 17]. Still, more precise predictive models are needed to assist clinicians in risk assessment and medical care. While blood hemoglobin concentration is often used to rate severity of bleeding in clinical routine, there is little evidence to support the validity of this practice. Moreover, identifying variables associated with unfavorable outcomes is the prerequisite for hypotheses regarding goal-directed therapy in acute GI bleeding. To address this, we evaluated the impact of various parameters in predicting short-term mortality with the aim of identifying high-risk individuals.

This multicenter study allowed us to observe that the MELD score and the peak-lactate levels at time of bleeding were significantly higher in 30-day non-survivors, while nadir hemoglobin levels did not differ between groups. However, the MELD-LA had superior discrimination for short-term mortality associated with variceal bleeding as compared to the nadir hemoglobin, the peak-lactate level, or the MELD score at admission.

Recently, serum lactate has been reported as a readily available predictor for short-term mortality in critically ill patients with cirrhosis [9]. In surgical patients, serum lactate has been widely recognized as an important warning signal for increased morbidity and mortality [18]. In addition, low serum hemoglobin and elevation of the MELD score have been associated with upper GI bleeding and increased mortality after variceal rebleeding [7, 15]. Lactate has been incorporated in several scoring systems such as the ACLF (acute-on-chronic liver failure) score, the CTP or recently in the MELD score [9, 10, 19, 20]. Sarmast et al. described MELD-LA as an easy-to-use, but objective parameter in predicting inpatient mortality in patients with chronic liver disease [10]. In addition, Mahmud et al. reported that the MELD-LA score surpasses other scores, such as the MELD or MELD-Na, in the prediction of mortality in patients with cirrhosis. The authors further observed that the best predictive properties of the MELD-LA score in patients with a MELD score was equal to or lower than 15, as well as in cirrhosis patients being hospitalized due to infection or shock [11]. However, in cirrhosis patients with variceal bleeding, it remains unclear whether serum lactate and the MELD-LA are reliable predictors of outcome.

It may be assumed that in the case of severe bleeding, lactate levels increase due to tissue hypoxia and hypoperfusion, as a result of oxygen deficiency caused by low hemoglobin levels and/or cardiocirculatory impairment [21]. Recently Mahmoodpoor et al. studied the correlation of arterial and venous serum lactate levels in adult patients with septic shock. They observed a strong linear correlation between venous and arterial lactate levels, with only minor deviations [22, 23]. In the present study, we found that both serum lactate and the MELD score, but not the nadir hemoglobin levels predicted mortality in cirrhotic patients with upper GI bleeding. An explanation might be that lactate accumulates due to cellular hypoxia and anaerobic glycolysis—both conditions frequently observed in patients with hemorrhagic shock [24, 25]. Besides this, it has been reported that patients with acute or chronic hepatic impairment in particular, are susceptible to hyperlactatemia, as the liver is responsible for more than 2/3 of the body’s lactate clearance [9, 26]. Due to this, hyperlactatemia possibly precedes reduction of serum hemoglobin and may therefore be the more sensitive parameter for hemodynamic insufficiency and liver dysfunction. Therefore, incorporating the MELD-LA score in existing clinical standards could be of value.

In line with D’Amico et al. who reported hematocrit, bilirubin levels and CTP classification as predictors for treatment failure and 6-week mortality in upper GI bleeding in cirrhotic patients, we observed an increased MELD score in 30-day non-survivors [3]. MELD-LA however, had superior predictive performance, predicting short-term mortality independent of age, sex, severity of the underlying liver disease and necessity of vasopressor support. Importantly, MELD-LA was validated as an excellent predictor of mortality in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding in two external validation cohorts. This implies that MELD-LA is a strong and widely applicable model, as the German and the U.S. cohorts are heterogenous and differ largely by etiology, age and severity of underlying liver disease. Furthermore, it is an objective model, it can be obtained on admission, and it is much easier to calculate than CLIF/CLIF-SOFA or APACHE scores. Despite the heterogeneity of our cohorts, MELD-LA has also shown consistency in various urban and rural settings. In summary, MELD-LA can improve the identification of individuals at high risk of mortality among patients with variceal bleeding and cirrhosis, who require more intensive treatment and surveillance. Prospective studies are warranted to validate the predictive performance of MELD-LA in this setting.

In addition to the consistent finding that serum lactate improves risk assessment in variceal bleeding, our data also suggest that serum lactate reflects a key pathologic mechanism underlying deterioration of patients with variceal bleeding: The association of lactate, but not anemia, with patient mortality indicates that impaired tissue microcirculation and consecutive metabolic imbalance may represent a possible therapeutic target. It can be hypothesized that lactate-guided fluid resuscitation or transfusion strategies could improve survival in patients with cirrhosis presenting with variceal bleeding—similar to early goal-directed therapy (including guided fluid resuscitation) in the treatment of septic shock [27-29]. This concept is supported by a large study on peptic ulcer bleeding, indicating that most patients died from non-bleeding causes and that hemodynamic stabilization, maintenance of microcirculation and tissue oxygenation to avoid multiorgan failure and cardiopulmonary death are relevant treatment targets [30]. Thus, our study presents a rationale for future prospective trials on lactate-guided or MELD-LA-guided resuscitation strategies in variceal bleeding. Moreover, in selected patients with advanced chronic liver disease presenting with variceal bleeding, early placement of TIPS has been repeatedly shown to improve survival [31, 32]. Currently, the indication for a pre-emptive TIPS is based on the CTP score (CTP C with 10–13 points) that to some extent underlies subjective interpretations. Newer data also suggest that also patients with ACLF and variceal hemorrhage benefit from pre-emptive TIPS placement [2, 33, 34]. In our study 11% patients received a TIPS implantation in association with bleeding event (within 5 days). Rate of TIPS implementation was comparable within the German centers. Mortality rates were slightly lower, in individuals receiving a TIPS, however this difference did not reach statistical significance. Notably, this study was not powered and designed in order to prove outcome related measures after TIPS implementation. Future studies should investigate the role of MELD-LA as an objective score in predicting response to the use of early TIPS in this setting.

The study is limited to some extent. First, due to the retrospective design of the study, our findings are limited by the data that were recorded and available for chart review. Second, as only German university hospitals were included in the European cohort, findings may not be generalizable to other healthcare settings in rural areas in Europe. To overcome this, we validated results in two independent U.S. cohorts. The cohorts analyzed display significant heterogeneity in terms of size and method of patient selection. For instance, the smaller VA cohort does not represent a comprehensive evaluation of all consecutive patients with cirrhosis and variceal hemorrhage admitted to the center but was selected rather by ICD codes with putative circulatory dysfunction. The German cohorts were selected based on endoscopic diagnosis of variceal bleeding. This implies a significant risk for selection bias and may to some extent explain the different outcome between the cohorts. The high mortality rate in the German cohort may be due to a potential selection bias, as only cases with available serum lactate values were included. While not routinely performed in German centers in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding, lactate measurements are more likely to be available in instable cases requiring an ICU management or anaesthesiological support. Similarly, this is true for the VA cohort, which is limited to only those variceal hemorrhages in which lactate was measured.

Still, despite all differences, the association between MELD-LA and mortality was confirmed across both, the German and the US cohort. But it appears that MELD LA works across cohorts both with low and high mortality as previously shown.

In conclusion, the combination of MELD and serum lactate achieves superior discrimination for short-term mortality associated with variceal bleeding in cirrhosis patients as compared to the MELD score, the nadir hemoglobin, or lactate levels alone. Thus, MELD-LA may serve as a useful objective marker for risk assessment and early targeted therapy in variceal bleeding. Moreover, the association between lactate and mortality suggests that impaired tissue microcirculation and hypoxia promote deterioration of patients with variceal bleeding, warranting future studies on lactate dynamics, lactate-guided fluid resuscitation strategies and investigations of early TIPS in this setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Elaine Hussey for proofreading and linguistic correction of the manuscript.

Funding

This is an academic study; no specific funding has been received for conducting this study.

Abbreviations

- MELD

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

- MELD-LA

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-lactate score

- VA

Veterans Affairs

- GI

Gastrointestinal

- CTP

Child–Turcotte–Pugh

- AUROC

Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

- ALD

Alcohol-related liver disease

Footnotes

Conflict of interest All authors declare that they have no conflict of interests regarding this manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript. Authors had authority over manuscript preparation and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The participating centers take responsibility for the integrity of the original data and data analyses contributed.

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-022-07744-w.

References

- 1.Bosch J, Groszmann RJ, Shah VH. Evolution in the understanding of the pathophysiological basis of portal hypertension: How changes in paradigm are leading to successful new treatments. J Hepatol 2015;62:S121–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address eee, European Association for the Study of the L. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2018;69:406–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Amico G, De Franchis R, Cooperative Study Group. Upper digestive bleeding in cirrhosis. Post-therapeutic outcome and prognostic indicators. Hepatology 2003;38:599–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovalak M, Lake J, Mattek N, Eisen G, Lieberman D, Zaman A. Endoscopic screening for varices in cirrhotic patients: data from a national endoscopic database. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:82–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Franchis R, Baveno VIF. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: Report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: Stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2015;63:743–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.del Olmo JA, Pena A, Serra MA, Wassel AH, Benages A, Rodrigo JM. Predictors of morbidity and mortality after the first episode of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2000;32:19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomizawa M, Shinozaki F, Hasegawa R, et al. Low hemoglobin levels are associated with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Biomed Rep 2016;5:349–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kraut JA, Madias NE. Lactic acidosis. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2309–2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drolz A, Horvatits T, Rutter K, et al. Lactate improves prediction of short-term mortality in critically ill patients with cirrhosis: a multinational study. Hepatology 2019;69(1):258–269. 10.1002/hep.30151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarmast N, Ogola GO, Kouznetsova M, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease-lactate and prediction of inpatient mortality in patients with chronic liver disease. Hepatology 2020;72(5):1747–1757. 10.1002/hep.31199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahmud N, Asrani SK, Kaplan DE, et al. The Predictive Role of MELD-Lactate and Lactate Clearance for In-Hospital Mortality among a National Cirrhosis Cohort. Liver Transpl. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serper M, Kaplan DE, Shults J, et al. Quality Measures, All-Cause Mortality, and Health Care Use in a National Cohort of Veterans With Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2019;70:2062–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steyerberg EW, Vickers AJ, Cook NR, et al. Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology 2010;21:128–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen WT, Lin CY, Sheen IS, et al. MELD score can predict early mortality in patients with rebleeding after band ligation for variceal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:2120–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reverter E, Tandon P, Augustin S, et al. A MELD-based model to determine risk of mortality among patients with acute variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology 2014;146:e413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaman A, Becker T, Lapidus J, Benner K. Risk factors for the presence of varices in cirrhotic patients without a history of variceal hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:2564–2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bakker J, de Lima AP. Increased blood lacate levels: an important warning signal in surgical practice. Crit Care 2004;8:96–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim S, Zerillo J, Tabrizian P, et al. Postoperative Meld-Lactate and Isolated Lactate Values As Outcome Predictors Following Orthotopic Liver Transplantation. Shock 2017;48:36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell J, McPeake J, Shaw M, et al. Validation and analysis of prognostic scoring systems for critically ill patients with cirrhosis admitted to ICU. Crit Care 2015;19:364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.James JH, Luchette FA, McCarter FD, Fischer JE. Lactate is an unreliable indicator of tissue hypoxia in injury or sepsis. Lancet 1999;354:505–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahmoodpoor A, Shadvar K, Sanaie S, et al. Arterial vs venous lactate: Correlation and predictive value of mortality of patients with sepsis during early resuscitation phase. J Crit Care 2020;58:118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Velissaris D, Karamouzos V, Pantzaris ND, Kyriakopoulou O, Gogos C, Karanikolas M. Relation Between Central Venous, Peripheral Venous and Arterial Lactate Levels in Patients With Sepsis in the Emergency Department. J Clin Med Res 2019;11:629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levy B. Lactate and shock state: the metabolic view. Curr Opin Crit Care 2006;12:315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cannon JW. Hemorrhagic Shock. N Engl J Med 2018;378:370–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jeppesen JB, Mortensen C, Bendtsen F, Moller S. Lactate metabolism in chronic liver disease. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 2013;73:293–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mouncey PR, Osborn TM, Power GS, et al. Trial of early, goal-directed resuscitation for septic shock. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1301–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howell MD, Davis AM. Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock. JAMA 2017;317:847–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horvatits T, Drolz A, Trauner M, Fuhrmann V. Liver Injury and Failure in Critical Illness. Hepatology 2019;70:2204–2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sung JJ, Tsoi KK, Ma TK, Yung MY, Lau JY, Chiu PW. Causes of mortality in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding: a prospective cohort study of 10,428 cases. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:84–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lv Y, Yang Z, Liu L, et al. Early TIPS with covered stents versus standard treatment for acute variceal bleeding in patients with advanced cirrhosis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;4:587–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia-Pagan JC, Caca K, Bureau C, et al. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med 2010;362:2370–2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tripathi D, Stanley AJ, Hayes PC, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt in the management of portal hypertension. Gut 2020;69:1173–1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trebicka J, Gu W, Ibanez-Samaniego L, et al. Rebleeding and mortality risk are increased by ACLF but reduced by pre-emptive TIPS. J Hepatol 2020;73:1082–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.