Abstract

An epidemic of infectious diseases such as COVID-19 can affect mental health, which may be associated with suicidal behaviors. This study was conducted based on the systematic review and meta-analysis methods for evaluating the prevalence of suicide ideation during COVID-19. This study used Preferred Systematic Review Reporting System and Meta- Analysis guideline and valid keywords. The articles related to the prevalence of suicide ideation during COVID-19 pandemic were obtained by searching among different databases including Scopus, Web of science, PubMed, ISC, Google scholar, SID, and Magiran. All of the articles published from the beginning of January 2020 to the end of May 2021 were reviewed. Among 478 articles screened, 377 articles were related to the studied topic, among which 38 articles were selected after assessing the title and abstract of which for reviewing the full text and finally 18 studies were included in the meta-analysis. Based on the results, the prevalence of suicide ideation and attempt among all studies were equal to 13% (95% confidence interval = 0.11-0.15, I2 = 99.7%, P = 0.00) and 1% (95% confidence interval = 0.00-0.01, I2 = 95.5%, P = 0.00), respectively. Based on the results, the prevalence of suicide attempt and ideation is possible during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, health officials should pay attention to mental health issues in addition to the protective measures for preventing or reducing the infection with COVID-19. The increase of psychological consequences is probably related to the effect of lifestyle changes which associates with the spread of the disease. In the current meta-analysis performed, the prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt was examined during the COVID-19 pandemic period and compared to the previous period without COVID-19. The effect of COVID-19 on suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt has never been studied.

Keywords: COVID-19, suicidal attempt, suicidal ideation, suicidal thought

Introduction

Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) first appeared in late 2019 as the outbreak of respiratory diseases in Wuhan City, Hubei Province, China, and rapidly spread around the world.[1] It was first reported to the World Health Organization on December 31, 2019. Then, the outbreak of COVID-19 was considered as a global health emergency on January 30, 2020 and declared as a pandemic on March 11, 2020.[2,3] COVID-19 pandemic affects many aspects of people's lives including health, economic welfare, individual and social life, family relationships, job, food, hygiene, and emotions around the world. Lack of vaccine and antiviral drugs causes some restrictive measures and nonpharmacological interventions such as quarantine, isolation, social distance, and the closure of institutions and cancellation of gatherings were used for controlling the spread of the virus. Therefore, this infectious disease causes lifestyle changes, worry and obsessive-compulsive disorder, and unpleasant feelings such as sadness, anxiety, and loss of life control,[4] which can be a sign of mental disorders such as depression or anxiety.[5] Uncertainty about the time of return to the normal life or whether it will return at all causes the difficulty in managing plans, which leads to the additional pressures.[6] Moreover, the issues such as economic and social harm, increased stress, and job loss are considered as the major causes for mental health problems related to COVID-19 pandemic, which may be related to suicidal behaviors.[7,8,9] Environmental changes are a source of stress[10] which leads to the neurological and psychological changes associated with suicidal behaviors.[11] Suicidal behavior is multifactorial;[12] the stress of an unfavorable life was reported as a risk factor for suicide ideation.[13] This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of suicide ideation and attempt during COVID-19 pandemic through a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Method

This study was performed by using Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses criteria.[14] The protocol of this review study is registered in PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Review with the code CRD42021276988.

Search strategy

Searches were conducted on various databases including Scopus, ISC, Web of Science, PubMed, SID, Google scholar, and Magiran by using valid keywords such as suicidal ideation OR suicidal thought, mental health problem OR mental health disorder, psychiatric disease OR psychiatric disorder, 2019 novel coronavirus disease OR COVID-19 OR COVID-19 pandemic OR SARS-CoV-2 infection OR COVID-19 virus disease OR 2019 novel coronavirus infection OR 2019-nCoV infection OR coronavirus disease 2019 OR coronavirus disease-19 OR 2019-nCoV disease OR COVID-19 virus infection OR coronavirus infection OR 2019-nCoV OR Wuhan coronavirus OR SARS-CoV-2 and appropriate strategies from the beginning of January 2020 to the end of May 2021.

Samples of the search strategy used in PubMed included “suicidal ideation*” OR “suicidal thought*” OR “mental health problem*” OR “mental health disorder*” OR “psychiatric disease*” OR “psychiatric disorder*” AND “2019 novel coronavirus disease” OR “COVID-19” OR “COVID-19 pandemic” OR “SARS-CoV-2 infection” OR “COVID-19 virus disease” OR “2019 novel coronavirus infection” OR “2019-nCoV infection” OR “coronavirus disease 2019” OR “coronavirus disease-19” OR “2019-nCoV disease” OR “COVID-19 virus infection” OR “coronavirus Infection” OR “Middle East respiratory syndrome” OR “MERS” OR “2019-nCoV” OR “Wuhan coronavirus” OR “SARS-CoV-2”.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria included the studies examining the association between COVID-19 and the suicide ideation and attempt. Exclusion criteria included the report of suicide risk, letter to the editor, systematic review, and studies which did not have sufficient information to participate in the study.

Study selection

Among 478 articles reviewed, 201 cases were deleted related to the irrelevance and duplication of which. Then, 41 articles were selected for a full-text review by considering the title and abstracts of 377 studies. Finally, 18 studies entered the statistical evaluation process.

Quality assessment and data extraction

The quality of the studies was assessed using the standard STROBE checklist.[15] The minimum and maximum scores were 0 and 44 in this checklist, respectively. The studies with a minimum score of 16[16] were selected for the meta-analysis. The required data were extracted from the selected final studies using a checklist prepared by the research team. Data included author name, year of publication, place of study, type of study, sample size, number of suicide ideation and attempt, and number of men and women.

Statistical analysis

Random effects model was used for this meta-analysis. The heterogeneity was assessed among the studies using I2 method,[17] when the value of I2 index is less than 25%, between 25%-75% and 75% and more indicates low, and moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively. Publication bias was quantitatively evaluated by using the Egger's test.[18] STATA software version 14 was used for data analysis.

Results

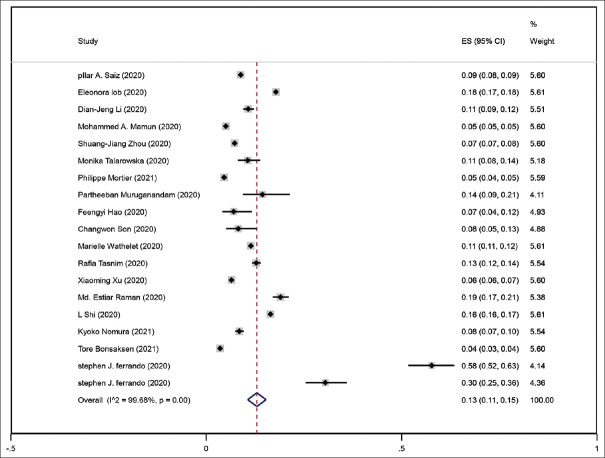

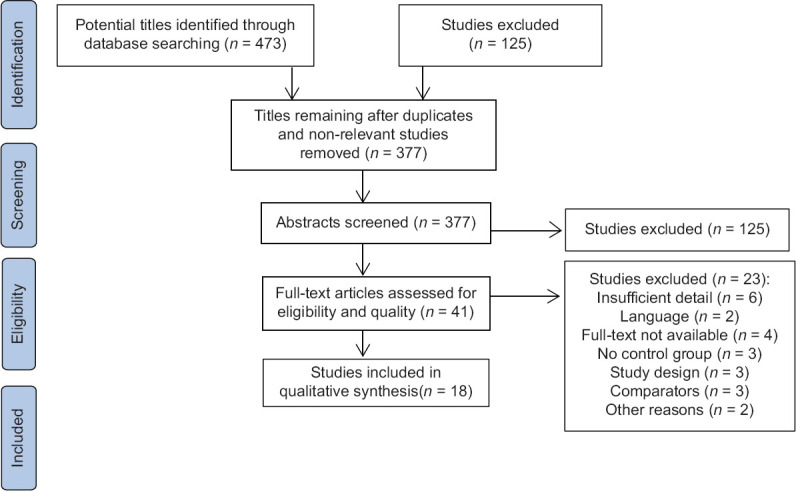

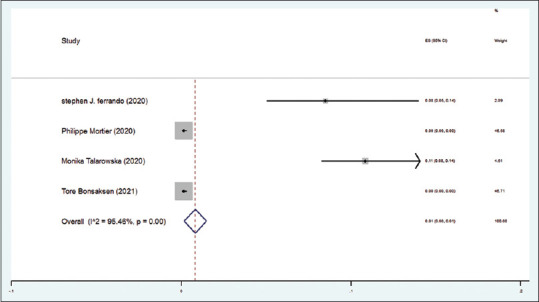

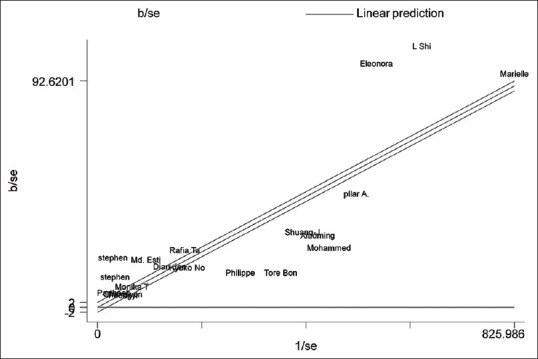

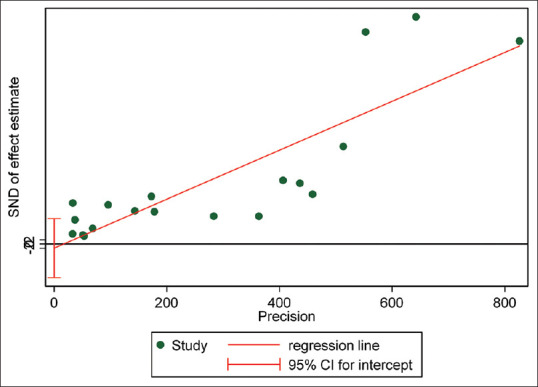

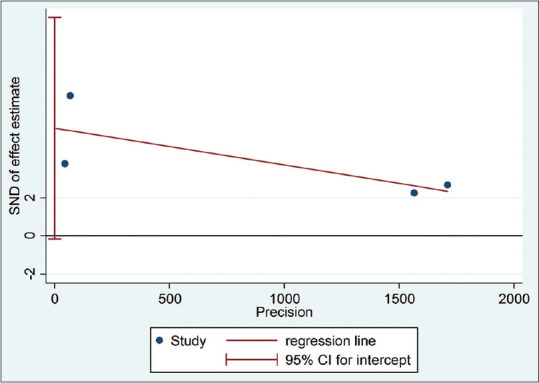

After reviewing 478 articles, 201 cases were deleted due to irrelevance and duplication. Therefore, 377 studies were screened and titles and abstracts of which were evaluated. Among which, 41 articles were selected for a full-text review. Finally, 18 studies entered the meta-analysis process [Figure 1]. Among 243,114 people evaluated, 147,654 and 92,019 cases were women and men, respectively, and the gender of the rest was unknown [Tables 1 and 2]. Using the random effects model indicated that the prevalence of suicide ideation and attempt among all studies were equal to 13% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.11-0.15, I2 = 99.7%, P = 0.00) and 1% (95% CI = 0.00-0.01, I2 = 95.5%, P = 0.00), respectively [Figures 2 and 3]. Evaluating the heterogeneity among all the studies graphically showed that not all the studies were within the 95% CI. Therefore, the results of the studies of this meta-analysis were heterogeneous [Figures 4 and 5]. Moreover, the Egger diagram among suicide ideation studies was almost crossed the origin below regression line. Therefore, no significant publication bias occurred in suicide ideation studies [Figure 6]. However, the presence of bias publication was confirmed among suicide attempt studies because the result of Egger's test is almost significant (P = 0.05) and its confidence range (-0.16 to 11.42) is variable [Figure 7].

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study and selection of studies based on the PRISMA steps

Table 1.

Characteristics of extracted papers for meta-analysis

| Author | Year | Design | Location | Subjects | Male | Female | Suicidal ideation | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sáiz et al.[19] | 2020 | cross-sectional | Spain | 21,207 | 6,439 | 14,768 | 1,873 | 469 | 1,404 |

| Iob et al.[20] | 2020 | cross-sectional | London | 44,775 | 21,929 | 22,846 | 7,984 | 3,885 | 4,099 |

| Li et al.[9] | 2020 | cross-sectional | Taiwan | 1,970 | 650 | 1,305 | 212 | ||

| Mamun et al.[21] | 2020 | cross-sectional | Bangladesh | 10,056 | 5,650 | 4,406 | 506 | 215 | 291 |

| Zhou et al.[22] | 2020 | cross-sectional | China | 11,133 | 4,195 | 6,938 | 810 | 341 | 469 |

| Talarowska et al.[23] | 2020 | cross-sectional | Poles | 443 | 47 | ||||

| Mortier et al.[24] | 2021 | cross-sectional | Spain | 3,500 | 1,583 | 1,917 | 20 | ||

| Muruganandam et al.[25] | 2020 | cross-sectional | South India | 132 | 19 | ||||

| Hao et al.[26] | 2020 | cross-sectional | China | 185 | 13 | ||||

| Son et al.[27] | 2020 | cross-sectional | Texas | 195 | 84 | 111 | 16 | ||

| Wathelet et al.[28] | 2020 | cross-sectional | France | 69,054 | 18,019 | 51,035 | 7,891 | 1,783 | 6,108 |

| Tasnim et al.[29] | 2020 | cross-sectional | Bangladesh | 3,331 | 1,979 | 1,352 | 427 | 227 | 200 |

| Xu et al.[30] | 2020 | cross-sectional | China | 11,507 | 2,521 | 8,986 | 744 | 151 | 593 |

| Raman et al.[31] | 2020 | cross-sectional | Bangladesh | 1415 | 875 | 540 | 269 | ||

| Shi et al.[32] | 2020 | cross-sectional | China | 56,679 | 27,149 | 29,530 | 9,322 | 5,195 | 4,127 |

| Nomura et al.[33] | 2021 | cross-sectional | Japan | 2,449 | 207 | ||||

| Bonsaksen et al.[34] | 2021 | cross-sectional | Norwegian | 4,527 | 659 | 3,650 | 161 | 17 | 143 |

| Ferrando et al.[35] | 2020 | retrospective cohort | New York City | cnt: 202 case: 65 | cnt: 85 case: 38 | cnt: 111 case: 38 | cnt: 93 case: 61 | ||

| Ferrando et al.[35] | 2020 | retrospective cohort | New York City | cnt: 153 case: 136 | cnt: 91 case: 73 | cnt: 59 case: 62 | cnt: 28 case: 60 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of the extracted papers for meta-analysis

| Author | Year | Design | Location | Subjects | Male | Female | Suicidal attempt | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ferrando et al.[35] | 2020 | retrospective cohort | New York City | cnt: 202 case: 65 | cnt: 85 case: 38 | cnt: 111 case: 38 | cnt: 10 case: 1 | ||

| Ferrando et al.[35] | 2020 | retrospective cohort | New York City | cnt: 153 case: 136 | cnt: 91 case: 73 | cnt: 59 case: 62 | cnt: 6 case: 7 | ||

| Talarowska et al.[23] | 2020 | cross-sectional | Poles | 443 | 48 | ||||

| Mortier et al.[24] | 2020 | cross-sectional | Spain | 3,500 | 1,583 | 1,917 | 5 | ||

| Bonsaksen et al.[34] | 2021 | cross-sectional | Norwegian | 4,527 | 659 | 3,650 | 7 | 2 | 5 |

Figure 2.

Forrest plot of the prevalence of suicide ideation during COVID-19

Figure 3.

Forrest plot of the prevalence of suicide attempt during COVID-19

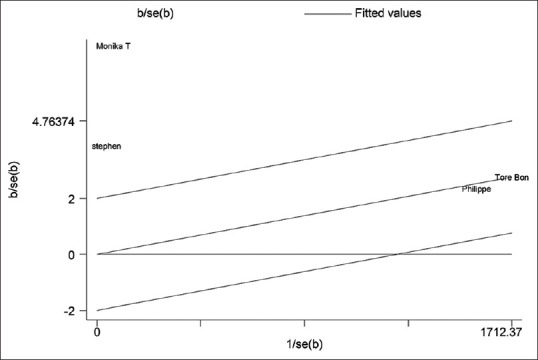

Figure 4.

Evaluating the heterogeneity among all suicide ideation studies graphically

Figure 5.

Evaluating the heterogeneity among all suicide attempt studies graphically

Figure 6.

Results of publication bias test in suicide ideation studies based on the Egger's test

Figure 7.

Results of publication bias test in suicide attempt studies based on the Egger's test

Discussion

This meta-analysis provided a review of the prevalence of suicide ideation and attempt during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was reported 0.13% and 0.01%, respectively.

The meta-analysis conducted by Justin P Dube indicted that the average prevalence of suicide ideation and attempt and self-harm was 10.81%, 4.68%, and 9.63%, respectively. Furthermore, the psychological, economic, behavioral, and psychosocial-social problems related to COVID-19 were associated with an increase in suicidal behaviors compared to before the pandemic.[36] The problems including job instability, poverty, and low income can cause suicidal behaviors. Meta-analysis of Eric Robinson demonstrated an overall increase in symptoms of mental health disorders including anxiety, depression, and mood disorders compared to before the outbreak of COVID-19.[37] Based on the results, the epidemic of infectious diseases can be considered as a factor endangering the mental health of people in society. A cross-sectional study of Mohammed A. Mamun showed that the prevalence of depression and suicide thoughts associated with COVID-19 was 33% and 5%, respectively. The main factors of suicide and depression included young age, being a woman, smoking, having various diseases, having a higher score than the COVID-19 fear scale, and insomnia.[21]

The meta-analysis of Sofia Pappa indicated that the prevalence of anxiety and depression among healthcare workers was 23.2% and 22.8%, respectively.[38] Meta-analysis of Tianchen Wu demonstrated that the overall prevalence of depression, anxiety, distress, and insomnia was 31.4%, 31.9%, 41.1%, and 37.9%, respectively. Patients with noninfectious chronic disease, quarantined persons, and patients with COVID-19 had the highest risk of depression (Q = 26.73, P <.01) and anxiety (Q = 21.86, P <.01). The general population and nonmedical staff had a lower risk of distress compared to other populations (Q = 461.21, P <.01). Physicians, nurses, and nonmedical staff showed a higher prevalence of insomnia than other populations (Q = 196.64, P <.01).[39]

Meta-analysis of Eric Robinson which was related to the mental health changes during and before the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that an overall increase was observed in mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic (standardized mean change), which was more pronounced during March to April 2020 (standardized mean change =0.102 [95% CI:.026 to. 192], P =0.03).[37]

The meta-analysis conducted by Gabriele Prati showed that COVID-19 pandemic had the little effect on mental health symptoms (g = 0.17, S.E. = 0.05, 95% CI (0.06-0.24), P =0.001). Due to the significant heterogeneity among the data, it was possible that the effects of COVID-19 pandemic were different in various groups of the society and were influenced by social and contextual factors.[40] Further studies are suggested for assessing the risk factors and predisposing factors of mental disorders. Moreover, the necessary measures should be done for reducing stress, anxiety disorders, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, which may be associated with suicidal behaviors.

Conclusion

Health officials should pay attention to mental health issues in addition to the protective measures for preventing or reducing the infection with COVID-19 because the prevalence of suicide attempt and thought is possible during the COVID-19 pandemic. The increase of psychological consequences is probably related to the effect of lifestyle changes which is related to the spread of the disease. In the current meta-analysis performed, the prevalence of suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt was examined during the COVID-19 pandemic period and compared to the previous period without COVID-19. The effect of COVID-19 on suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt has never been studied.

Limitations

Reporting the suicide risk instead of reporting the total number of suicide ideation and attempts in some studies was one of the limitations of this study, along with a lack of reporting the prevalence of suicide ideation and attempt based on the gender in some studies. Moreover, full text of some articles was not available. Finally, the reported high heterogeneity, which may be related to the large difference in sample size.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Control CfD. Prevention. Novel coronavirus, Wuhan, China: 2019-nCoV situation summary. Appendices. 2019;28:2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallegos A. WHO Declares Public Health Emergency for Novel Coronavirus. Medscape Medical News. 2020. Jan 30, [Last accessed on 2020 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/924596 .

- 3.Ramzy A, McNeil DG. W.H.O. Declares Global Emergency as Wuhan Coronavirus Spreads. The New York Times. 2020. Jan 30, [Last accessed on 2020 Jan 30]. Available from: https://nyti.ms/2RER70M .

- 4.Curry LC, Stone JG. The grief process: A preparation for death. Clin Nurse Spec. 1991;5:17–22. doi: 10.1097/00002800-199100510-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sønderskov KM, Dinesen PT, Santini ZI, Dinesen Østergaard S. The depressive state of Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2020;32:1–3. doi: 10.1017/neu.2020.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vinkers CH, van Amelsvoort T, Bisson JI, Branchi I, Cryan JF, Domschke K, et al. Stress resilience during the coronavirus pandemic. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;35:12–6. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iob E, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Abuse, self-harm and suicidal ideation in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Psychiatry. 2020;217:543–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gratz KL, Tull MT, Richmond JR, Edmonds KA, Scamaldo KM, Rose JP. Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness explain the associations of COVID-19 social and economic consequences to suicide risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2020;50:1140–8. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li DJ, Ko NY, Chen YL, Wang PW, Chang YP, Yen CF, et al. COVID-19-related factors associated with sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts among the Taiwanese public: A Facebook survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:4479. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17124479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreno JL, Nabity PS, Kanzler KE, Bryan CJ, McGeary CA, McGeary DD. Negative life events (NLEs) contributing to psychological distress, pain, and disability in a U.S. military sample. Mil Med. 2019;184:e148–55. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usy259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moscicki EK, Umhau JC. Environmental stressors may drive inflammation and alter neurocircuitry to promote suicidal behavior. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:21. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-1007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Heeringen K, Mann JJ. The neurobiology of suicide. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:63–72. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu RT, Miller I. Life events and suicidal ideation and behavior: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34:181–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. STROBE Initiative. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1495–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kazemzadeh M, Shafiei E, Jahangiri K, Yousefi K, Sahebi A. The preparedness of hospital emergency departments for responding to disasters in Iran; A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2019;7:e58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tu ZH, He JW, Zhou N. Sleep quality and mood symptoms in conscripted frontline nurse in Wuhan, China during COVID-19 outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e20769. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000020769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi X, Nie C, Shi S, Wang T, Yang H, Zhou Y, et al. Effect comparison between Egger's test and Begg's test in publication bias diagnosis in meta-analyses: Evidence from a pilot survey. Int J Res Stud Biosci. 2017;5:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sáiz PA, de la Fuente-Tomas L, García-Alvarez L, Bobes-Bascarán MT, Moya-Lacasa C, García-Portilla MP, et al. Prevalence of passive suicidal ideation in the early stage of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and lockdown in a large Spanish sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81:20l13421. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20l13421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iob E, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Abuse, self-harm and suicidal ideation in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Psychiatry. 2020;217:543–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mamun MA, Sakib N, Gozal D, Bhuiyan AI, Hossain S, Bodrud-Doza M, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and serious psychological consequences in Bangladesh: A population-based nationwide study. J Affect Disord. 2021;279:462–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou S-J, Qi M, Wang L-L, Yang X-J, Gao L, Zhang S-Y, et al. Mental health problems and related factors in Chinese university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Talarowska M, Chodkiewicz J, Nawrocka N, Miniszewska J, Biliński P. Mental health and the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic—Polish research study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:7015. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17197015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mortier P, Vilagut G, Ferrer M, Alayo I, Bruffaerts R, Cristóbal-Narváez P, et al. Thirty-day suicidal thoughts and behaviours in the Spanish adult general population during the first wave of the Spain COVID-19 pandemic. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2021;30:e19. doi: 10.1017/S2045796021000093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muruganandam P, Neelamegam S, Menon V, Alexander J, Chaturvedi SK. COVID-19 and severe mental illness: Impact on patients and its relation with their awareness about COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113265. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hao F, Tan W, Jiang L, Zhang L, Zhao X, Zou Y, et al. Do psychiatric patients experience more psychiatric symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown.A case-control study with service and research implications for immunopsychiatry? Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:100–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Son C, Hegde S, Smith A, Wang X, Sasangohar F. Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e21279. doi: 10.2196/21279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wathelet M, Duhem S, Vaiva G, Baubet T, Habran E, Veerapa E, et al. Factors associated with mental health disorders among university students in France confined during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2025591. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tasnim R, Islam MS, Sujan MS, Sikder MT, Potenza MN. Suicidal ideation among Bangladeshi university students early during the COVID-19 pandemic: Prevalence estimates and correlates. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;119:105703. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu X, Wang W, Chen J, Ai M, Shi L, Wang L, et al. Suicidal and self-harm ideation among Chinese hospital staff during the COVID-19 pandemic: Prevalence and correlates. Psychiatry Res. 2021;296:113654. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahman ME, Al Zubayer A, Bhuiyan MR, Jobe MC, Khan MK. Suicidal behaviors and suicide risk among Bangladeshi people during the COVID-19 pandemic: An online cross-sectional survey. Heliyon. 2021;7:e05937. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e05937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi L, Que JY, Lu ZA, Gong YM, Liu L, Wang YH, et al. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal ideation among the general population in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64:e18. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nomura K, Minamizono S, Maeda E, Kim R, Iwata T, Hirayama J, et al. Cross-sectional survey of depressive symptoms and suicide-related ideation at a Japanese national university during the COVID-19 stay-home order. Environ Health Prev Med. 2021;26:30. doi: 10.1186/s12199-021-00953-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonsaksen T, Skogstad L, Heir T, Ekeberg Ø, Schou-Bredal I, Grimholt TK. Suicide thoughts and attempts in the Norwegian general population during the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:4102. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferrando SJ, Klepacz L, Lynch S, Shahar S, Dornbush R, Smiley A, et al. Psychiatric emergencies during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in the suburban New York City area. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;136:552–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dubé JP, Smith MM, Sherry SB, Hewitt PL, Stewart SH. Suicide behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis of 54 studies. Psychiatry Res. 2021;301:113998. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinson E, Sutin AR, Daly M, Jones A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.Journal of affective disorders. 2022;296:567–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu T, Jia X, Shi H, Niu J, Yin X, Xie J, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:91–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prati G, Mancini AD. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: A review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychol Med. 2021;51:201–11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721000015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]