Abstract

Background

Research has shown that eczema patients prefer some degree of shared control over treatment decisions, but little is known about factors perceived to be important to facilitate shared decision making (SDM).

Objective

To determine factors eczema patients and caregivers consider to be important for SDM, and how often they experience them with their eczema healthcare provider (HCP).

Methods

A cross-sectional survey study (64 questions) was conducted, which included factors related to SDM rated by respondents on a Likert scale for importance, and how often these factors were true with their current eczema HCP.

Results

Respondents (840, response rate 62.4%) most frequently rated their health literacy and communication skills as important for SDM. Factors which indicated a strong provider-patient relationship, and HCPs who initiate treatment conversations were also deemed beneficial. Low importance was placed on concordant HCP race/ethnicity, however, of those who did rate it as important, 53/91 identified as Black (half of all Black respondents).

Limitations

A high proportion of respondents were aware of the term SDM prior to the survey.

Conclusions

SDM is more likely to be facilitated when patient education and empowerment are coupled with HCPs who initiate treatment discussions, maintain compassion resilience, and listen to patient perspectives.

Key words: atopic dermatitis, eczema, patient care, patient-provider relationship, shared decision-making, treatment decisions

Abbreviation used: HCP, healthcare provider; NEA, National Eczema Association; PDA, patient decision aid; SDM, shared decision making

Capsule Summary.

-

•

Previous research shows eczema patients want to be involved in decision-making for their treatments.

-

•

Patients do not place responsibility for shared decision-making solely on the provider. Providers who listen, initiate treatment discussions, and use a balance of virtual and in-person visits to save time, may facilitate more successful shared decision-making.

Introduction

Eczema is a chronic, relapsing, and remitting inflammatory skin disease that significantly affects patients’ and caregivers’ quality of life. Long-term control can be challenging to achieve due to eczema’s heterogeneous and protean nature and the need for varied treatment regimens over time.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Recognition of the need to improve eczema care has prompted development of international core outcomes sets for research (eg, Harmonizing Outcome Measures for Eczema), patient education initiatives, mobile apps (eg, EczemaWise [https://www.eczemawise.org/]), patient decision aids (PDAs), and multidisciplinary clinics specifically designed for eczema patients and caregivers.1, 2, 3,9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 Many of these tools were designed to improve patient satisfaction and outcomes by increasing patient self-efficacy and activating them to share in the decision making process for their own care.16, 17, 18

Shared decision making (SDM), specifically, is a process in which medical decision making is achieved by a healthcare provider (HCP) and patient working together, with the HCP contributing medical expertise and the patient contributing values and treatment goals.19 Research has shown that most eczema patients want some degree of shared control over their treatment decisions.20 Additionally, patient-centered communication is taught as an ethical imperative in medical school, yet a broader understanding and application of SDM is still lacking in dermatology.21

SDM is often viewed as a single treatment decision at a single appointment, but it is likely that the ability to engage in SDM at a specific point in time is at least partially dependent on characteristics about the patient, the HCP, and their relationship that are established before that particular appointment. Little is known about which factors eczema patients consider to be most important to engage in SDM. In this study, we aim to elucidate these factors, their relative importance, and how often patients experience them with their current primary eczema HCP.

Methods

Adults (≥18 years) who were residents of the United States (including US territories), with a self-reported diagnosis of eczema (eczema type not asked nor defined) or primary caregivers for pediatric eczema patients were included. Survey availability was communicated to all National Eczema Association (NEA) members via the NEA website, email, social media, and the NEA EczemaWise app, and distributed more broadly through ads run on Facebook and Google. Respondents were recruited from January 2021 to March 2021. Previous work utilized elements of this survey instrument to describe past, present, and future SDM behavior in eczema.20 Those elements are not included in the current study.

Prior to completing the 64-question online survey, respondents provided electronic informed consent, and those that fully completed the survey were eligible for 1 of twenty $50 Amazon gift cards. This study was identified as exempt by the Western Institutional Review Board Copernicus Group. All data were anonymized for analysis and treated confidentially.

Data analysis

Respondents were provided with a series of 21 factors related to the facilitation of SDM (see results section). These factors included aspects about the visit, the HCP, the patients themselves, and guidance. Respondents rated these factors according to their importance for working together with a HCP to identify appropriate treatment options (0-not important at all, 1-of little importance, 2-of average importance, 3-very important, and 4-absolutely essential). Responses were averaged for each factor, to create an overall importance rating score.

Respondents then indicated to what extent these factors were true with their primary eczema HCP (never true, rarely true, sometimes true, usually true, and always true). Respondents were considered to have their “needs met” if they indicated a factor was very important or absolutely essential and it was usually or always true. Needs were considered “not met” for those who indicated a factor was very important or absolutely essential, but reported it to be only sometimes, rarely, or never true. Proportions of those who had needs met or not met were only of those respondents who considered a factor very important or absolutely essential, as those who found a particular factor of average importance, of little importance, or not important at all were not deemed to have a “need” for it.

Analysis was performed using R: A language and environment for statistical computing (version 4.1.0). There were no imputations performed for missing data; some participants were excluded from some analyses due to missing data, and this has been indicated where applicable.

Results

In total, 840 respondents completed the survey (840/1345 who clicked on email link; response rate of 62.4%). Table I shows the characteristics of the included study population (N = 840).

Table I.

Characteristics of the study population

| All (N = 840) | |

|---|---|

| Connection to eczema (n [%]) | |

| Adult patient | 681 (81.1) |

| Caregiver of child | 159 (18.9) |

| Patient age (years; mean ± SD) | 40.1 ± 22.3 |

| Gender of patient (n [%]) | |

| Male | 152 (18.1) |

| Female | 675 (80.4) |

| Other | 13 (1.5) |

| Respondent race (n [%]) | |

| Asian or Asian American | 85 (10.1) |

| Black or African American | 109 (13.0) |

| Multiracial | 43 (5.1) |

| Native American or Alaskan Native | 6 (0.7) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 3 (0.4) |

| White | 555 (66.1) |

| Some other race or ethnicity | 22 (2.6) |

| I do not know/prefer not to say | 17 (2.0) |

| Respondent ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latinx (% Yes) | 72 (8.6) |

| Education (n [%]) | |

| High school, technical postsecondary, some or no high school | 116 (13.8) |

| Completed some college | 169 (20.1) |

| Four-year college degree | 280 (33.3) |

| Master’s degree/Doctorate | 255 (30.3) |

| No response | 20 (2.4) |

| Income (n [%]) | |

| $24,999 or less | 127 (15.1) |

| $25,000 to $49,999 | 152 (18.1) |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 140 (16.7) |

| $75,999 to $99,999 | 113 (13.4) |

| $100,000 to $124,999 | 100 (11.9) |

| $125,000 to $149,999 | 61 (7.3) |

| $150,000 or more | 127 (15.1) |

| No response | 20 (2.4) |

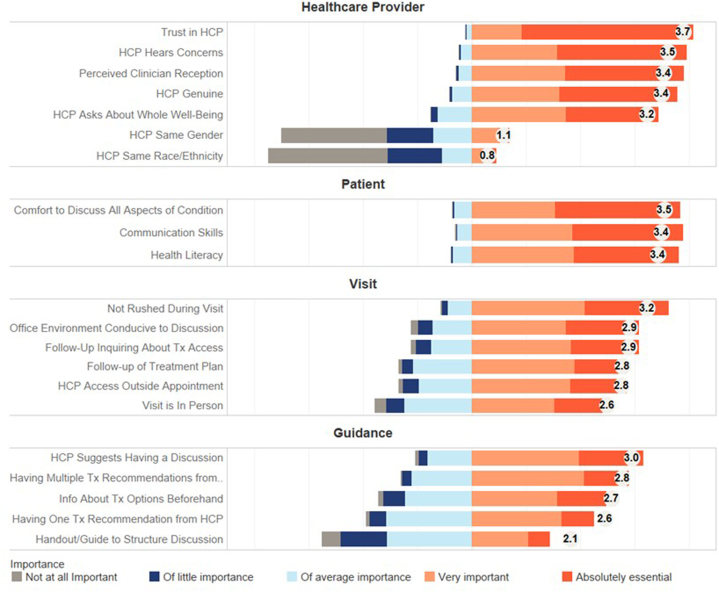

Average importance ratings for all queried SDM factors are shown in Fig 1. Factors were split into different domains that included aspects about the HCP, the patient, the visit, and guidance. The highest ratings within each domain were, “Having a healthcare provider I can trust” (3.7), “Having the comfort to articulate what I want to say about my/my child’s condition” (3.5), “Feeling like I am not rushed during my visit” (3.2), and “Having my healthcare provider be the one to suggest we have a discussion about my/my child’s treatment options” (3.0). Overall, respondents more often rated aspects about themselves and the HCP with higher levels of importance to facilitating SDM, compared to aspects of the visit or treatment guidance.

Fig 1.

Average importance ratings for factors important to facilitate SDM. Note the factors are abbreviated from their original statements; original statements in Table II. SDM, Shared decision making.

The factors with the lowest average ratings were, having an HCP with the same race or ethnicity or a HCP of the same gender (0.8 and 1.1, respectively) followed by “Having a handout/guide to structure the discussion” (2.1). Of respondents who rated HCP race and ethnicity matching their own to be important, 53/91 identified as Black (half of all Black respondents), and of the respondents who rated HCP gender matching their own to be important, only 10/140 were men (6.1% of all male respondents).

Table II shows the list of factors related to facilitation of SDM and the proportion of respondents who found the factor very important/absolutely essential. The final 2 columns show the proportion who felt this need is either met or not met with their current eczema HCP. Many respondents had their needs met for the aspects about their HCPs that they considered most important for SDM: trust, a provider who listens and values their input (needs met by 87.6%, 80.4%, and 79.8%, respectively). Many respondents also felt that their needs were met for aspects about themselves pertaining to health literacy and the ability and comfort to articulate what they want to say to their HCP. Aspects of the visit and guidance were less frequently rated as important for SDM, but unmet needs in these areas were prevalent and included: structured handouts to guide the discussion, open-ended/multiple treatment recommendations from the HCP, and information about treatments before the appointment to prepare (needs not met for 56.3%, 42.2%, and 49.8% of respondents, respectively). For the 9 factors deemed very important/absolutely essential by at least 80% of respondents, the percentage of respondents who indicated their needs were not met ranged from 11.4% to 36.3%.

Table II.

Factors associated with SDM and the proportion of respondents who felt that the need for this factor was either met or not met at their most recent eczema consultation. A need was considered “met” if respondents considered a factor “very important” or “absolutely essential,” and it was “usually” or “always true” with their primary eczema HCP

| Factor | Very important/absolutely essential n (% of total respondents) | Need met n (%) | Need not met n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspects about the healthcare provider | |||

| Having a healthcare provider whom I can trust | 818 (97.4) | 717 (87.6) | 101 (12.4) |

| Having a healthcare provider who listens to my perspectives about certain treatments (including concerns I might have) | 793 (94.4) | 638 (80.4) | 155 (19.6) |

| Having a healthcare provider value my input (based on my experience with eczema as a patient/caregiver) | 783 (93.2) | 625 (79.8) | 158 (20.2) |

| Having a healthcare provider who expresses genuine concern about how I’m doing/my child is doing | 759 (90.3) | 578 (76.1) | 181 (23.9) |

| Having a healthcare provider who asks about/is open to discussing my/my child’s whole well-being (including mental health) | 689 (82.0) | 437 (63.4) | 252 (36.3) |

| Having a healthcare provider with the same gender as me | 140 (16.7) | 120 (85.7) | 20 (14.3) |

| Having a healthcare provider with the same race/ethnicity as me | 91 (10.8) | 47 (51.6) | 44 (49.3) |

| Aspects about the patient | |||

| Having the ability to articulate what I want to say about my/my child’s condition (In other words, knowing how to express my/my child’s symptoms, thoughts and feelings) | 781 (93.0) | 692 (88.6) | 89 (11.4) |

| Having the comfort to articulate what I want to say about my/my child’s condition (In other words, having a safe space to discuss all aspects of my/my child’s condition) | 769 (91.5) | 667 (86.7) | 102 (13.3) |

| Being able to understand the medical terms or concepts discussed during a visit | 763 (90.8) | 666 (87.3) | 97 (12.7) |

| Aspects about the visit | |||

| Feeling like I am not rushed during my visit | 726 (86.4) | 497 (68.5) | 229 (31.5) |

| Being in an office environment which makes me feel like I can engage in a discussion | 618 (73.6) | 482 (78.0) | 136 (22.0) |

| Having follow-up about my/my child's treatment access (eg, ability to purchase/obtain medication that was prescribed, insurance coverage) | 618 (73.6) | 401 (64.9) | 217 (35.1) |

| Having follow-up about my/my child’s treatment(s) or management plan (eg, check-ins, discussions, additional visits) | 572 (68.1) | 394 (68.9) | 178 (31.1) |

| Having the ability to access my/my child’s healthcare provider outside the appointment (eg, by phone, email, online portal) | 572 (68.1) | 411 (71.9) | 161 (28.1) |

| Having an in-person visit (as opposed to a virtual visit by video or phone) | 484 (57.6) | 435 (89.9) | 49 (10.1) |

| Aspects about guidance | |||

| Having my healthcare provider be the one to suggest we have a discussion about my/my child’s treatment options (instead of having the healthcare provider immediately choose the treatment for me without my input) | 634 (75.5) | 390 (61.5) | 244 (38.5) |

| Having an open-ended or multiple recommendations from a healthcare provider about the treatment(s) I/my child could take | 579 (68.9) | 335 (57.8) | 245 (42.2) |

| Having information about treatment options beforehand | 498 (59.3) | 250 (50.2) | 248 (49.8) |

| Having one clear recommendation from a healthcare provider about the treatment(s) I/my child should take | 452 (53.8) | 347 (76.8) | 105 (23.2) |

| Having a handout/guide to structure the discussion | 288 (34.3) | 126 (43.8) | 162 (56.3) |

HCP, Healthcare provider; SDM, shared decision making.

Discussion

In this study, eczema patients and caregivers identify factors about their HCPs, themselves, the eczema care visit, and guidance that are important to them in order to feel comfortable engaging in SDM. Patients and caregivers most frequently cite the importance of their own health literacy and communication skills as well as a trusted HCP who listens to and values patient/caregiver input. Many respondents indicated that their needs for these factors are currently being met, although factors related to guidance of SDM discussions and information about treatment options may be lacking for those who find them important.

Aspects about the provider

Eczema patients and caregivers overwhelmingly prioritized HCPs who elicit trust, listen to their perspectives, and value their input in order to engage in SDM. While many patients felt that these needs were met with their current HCP, there were approximately 10% to 30% who had unmet needs in these key areas. For example, while trust in HCP had the highest average importance score, this need was not met for about 12% of respondents. Trust in an HCP has been shown to increase treatment adherence, while strong patient-HCP relationships can improve a medical practice’s success and decrease communication errors that incur higher costs.22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 A recent study of over 38,000 reviews of general dermatology clinics concluded that a HCP’s personality, empathy, and kindness may overcome other issues that are out of their control.29 This is not surprising, however, effective implementation of SDM should also address and ameliorate HCP compassion fatigue and burnout.30, 31, 32

Although the current study showed that few eczema patients perceived that the race, ethnicity, and gender of their HCP matching their own was important for SDM, as many as half of Black respondents did identify this as a key factor. Previous work has demonstrated that race-concordant medical visits are longer, while patients in race-discordant settings have lower satisfaction, lower ratings on decision making questionnaire items, and are more likely to perceive cultural differences with their HCP.33,34 This finding emphasizes the need for diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts currently undertaken by residency directors.35

Aspects about the patient

Patients and caregivers in this study did not feel that the responsibility for the facilitation of SDM was solely on the HCP. Approximately 92% of respondents said that their own health literacy, ability to articulate their experience, and the comfort to do so were very important or absolutely essential to facilitate SDM. Importantly, about 88% felt that these factors were usually or always true for them with their current eczema HCP. Previous work has confirmed that patient knowledge leads to better health outcomes36 and to increased confidence to engage in SDM.20 However, it is imperative that this perceived knowledge about eczema comes from reputable sources rather than undirected online searches. Providing patients with resources to read between appointments or ‘referring” patients to recognize patient advocacy organizations could improve communication, save the patient time in sourcing reputable information, and save the HCP time during an appointment.

Aspects about the visit and guidance

One barrier often cited as prohibiting use of SDM in routine clinical practice is the lack of time in appointments, as the average time for a general dermatology consultation is just 16.5 minutes.37 In this study, patients reported it was important to not feel rushed during their appointment (86.4%), and yet, around one-third said this was an unmet need with their current HCP. Previous studies have shown that SDM in a dermatology encounter can effectively occur before, during or after a visit, and can take as little as 2 to 5 minutes, without adding overall time to the time already spent in routine discussions of treatment.38, 39, 40, 41 In addition, time spent counseling patients is now more easily reimbursable with 2021 revisions to medical coding. Another mechanism to save time may be virtual visits, which can be scheduled more frequently and may be less time consuming for HCPs and patients. Virtual visits have also been shown to reduce missed appointments in dermatology, especially for non-White patients.42 In our study, 42.4% of patients did not find in-person visits to be important for SDM. HCPs could incorporate a balance of visit types, maintaining in-person visits for times when either the HCP or patient feel they may benefit from more substantial treatment discussions.

Only a third of respondents in this study said that having a handout to guide treatment discussions was very important or essential to facilitating treatment decisions. However, for those who did find it important, 56.3% reported not having this need met with their current HCP. Similarly, around half of respondents did not have their needs met for receiving information about treatment options before an appointment. The low proportion of patients who found a handout to be important might be because many PDAs for atopic dermatitis are still in development or because they have not seen one before. Additionally, HCP training on the framing of conversations around these PDAs – especially regarding quantitative or risk-related information – is still lacking.43 While PDAs and HCP training will take time to validate and implement, HCPs can make use of available evidence-based information from professional medical and patient advocacy organizations as part of appointment discussion and follow-up materials. Additionally, some patients and HCPs may prefer to structure certain SDM conversations over several visits. Where possible, HCPs can aid SDM by providing patients with information about treatment options before an appointment.44, 45, 46

Lastly, a notable unmet need eczema patients and caregivers reported was having an HCP initiate the discussion about treatment options (39% unmet need with current HCP for those who reported it important/essential). This sentiment is supported by previous patient-centered research.20 Patients who feel equipped to discuss treatment options with a doctor they trust may additionally require an opening from the HCP to start the conversation.

Limitations

One limitation in this study is that a large proportion of respondents (75%) were aware of the term “shared decision making” before this survey. Patients and caregivers who receive information from and engage with a patient advocacy organization like NEA likely have higher levels of health literacy, self-efficacy, and communication skills. Consequently, the unmet needs reported in this study probably underestimate the unmet needs of the larger eczema community, especially regarding health literacy and communication skills. An additional limitation is that study respondents were American residents and predominantly female; therefore, the results cannot be globally generalized. Also, as respondents provided information related to their current primary eczema HCP, these data may not reflect previous SDM experiences or those with secondary eczema HCPs.

In considering aspects about patients and HCPs which can facilitate SDM, it is also crucial to consider the structural confines of the healthcare experience, which were not addressed in this study. Patients face barriers to seeing specialists, such as those caused by geographic location, cost, insurance restrictions, and lack of available appointments.47, 48, 49 HCPs face barriers such as lack of training in SDM and both actual and perceived lack of time during appointments. These barriers are often largely outside the control of either of these groups and merit additional study related to facilitation of SDM.

Conclusion

SDM is often viewed as a single treatment decision at 1 appointment, but this oversimplifies the dynamic nature of a chronic disease like eczema, which may require multiple treatment decisions over a patient’s lifetime. While several patient and HCP factors emerged as important to facilitate SDM, each of the 21 queried factors displayed the spectrum of respondent responses, underscoring the potential heterogeneity of “good” SDM in eczema care from the patient perspective and the need for further research. Ideally, SDM results from an ongoing dialogue over many visits between a trusted HCP and a patient with health literacy and self-efficacy. Our study indicates that successful SDM is more likely to be facilitated when efforts to improve patient education and empowerment are coupled with HCPs who initiate treatment discussions, maintain compassion resilience, and listen to and value patient perspectives.

Conflicts of interest

Ms Smith Begolka reported sponsorship from Sanofi/Regeneron during the conduct of the study; advisory board honoraria paid to institution from Pfizer and Incyte and grants paid to institution from Pfizer outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Footnotes

Drs Foster and Loiselle contributed equally to this article.

Funding sources: The National Eczema Association received sponsorship support from Sanofi. The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

IRB approval status: This study was identified as exempt by the Western Institutional Review Board Copernicus Group.

Patient consent: Not applicable.

References

- 1.Eicher L., Knop M., Aszodi N., Senner S., French L.E., Wollenberg A. A systematic review of factors influencing treatment adherence in chronic inflammatory skin disease - strategies for optimizing treatment outcome. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33(12):2253–2263. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel N.U., D'Ambra V., Feldman S.R. Increasing adherence with topical agents for atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(3):323–332. doi: 10.1007/s40257-017-0261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bass A.M., Anderson K.L., Feldman S.R. Interventions to increase treatment adherence in pediatric atopic dermatitis: a systematic review. J Clin Med Res. 2015;4(2):231–242. doi: 10.3390/jcm4020231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krejci-Manwaring J., Tusa M.G., Carroll C., et al. Stealth monitoring of adherence to topical medication: adherence is very poor in children with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(2):211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conde J.F., Kaur M., Fleischer A.B., Jr., Tusa M.G., Camacho F., Feldman S.R. Adherence to clocortolone pivalate cream 0.1% in a pediatric population with atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2008;81(5):435–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hix E., Gustafson C.J., O'Neill J.L., et al. Adherence to a five day treatment course of topical fluocinonide 0.1% cream in atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19(10):20029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Charman C.R., Morris A.D., Williams H.C. Topical corticosteroid phobia in patients with atopic eczema. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142(5):931–936. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohya Y., Williams H., Steptoe A., et al. Psychosocial factors and adherence to treatment advice in childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117(4):852–857. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yentzer B.A., Camacho F.T., Young T., Fountain J.M., Clark A.R., Feldman S.R. Good adherence and early efficacy using desonide hydrogel for atopic dermatitis: results from a program addressing patient compliance. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(4):324–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sagransky M.J., Yentzer B.A., Williams L.L., Clark A.R., Taylor S.L., Feldman S.R. A randomized controlled pilot study of the effects of an extra office visit on adherence and outcomes in atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(12):1428–1430. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guraya A., Pandher K., Porter C.L., et al. Review of the holistic management of pediatric atopic dermatitis. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181(4):1363–1370. doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-04341-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spielman S., LeBovidge J., Timmons K., Schneider L. A review of multidisciplinary interventions in atopic dermatitis. J Clin Med. 2015;4(5):1156–1170. doi: 10.3390/jcm4051156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santer M., Burgess H., Yardley L., et al. Managing childhood eczema: qualitative study exploring carers' experiences of barriers and facilitators to treatment adherence. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69(11):2493–2501. doi: 10.1111/jan.12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams H.C., Schmitt J., Thomas K.S., et al. The HOME Core outcome set for clinical trials of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(6):1899–1911. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leong K., Ong T.W.Y., Foong Y.W., et al. Multidisciplinary management of chronic atopic dermatitis in children and adolescents: a prospective pilot study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(2):822–828. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1782321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bass S.B., Ruzek S.B., Gordon T.F., Fleisher L., McKeown-Conn N., Moore D. Relationship of internet health information use with patient behavior and self-efficacy: experiences of newly diagnosed cancer patients who contact the National Cancer Institute's Cancer Information service. J Health Commun. 2006;11(2):219–236. doi: 10.1080/10810730500526794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salazar L.R. The effect of patient self-advocacy on patient satisfaction: exploring self-compassion as a mediator. Commun Stud. 2018;69(5):567–582. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2018.1462224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hibbard J.H., Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff. 2013;32(2):207–214. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Preventive Services Task Force, Davidson K.W., Mangione C.M., et al. Collaboration and shared decision-making between patients and clinicians in preventive health care decisions and Us Preventive Services Task Force recommendations. JAMA. 2022;327(12):1171–1176. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thibau I.J., Loiselle A.R., Latour E., Foster E., Smith Begolka W. Past, present, and future shared decision-making behavior among patients with eczema and caregivers. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(8):912–918. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison T., Johnson J., Baghoomian W., et al. Shared decision-making in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(3):330. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.5362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thom D.H., Ribisl K.M., Stewart A.L., Luke D.A. Further validation and reliability testing of the trust in physician scale. The Stanford Trust Study physicians. Med Care. 1999;37(5):510–517. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199905000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levinson W., Roter D.L., Mullooly J.P., Dull V.T., Frankel R.M. Physician-patient communication. The relationship with malpractice claims among primary care physicians and surgeons. JAMA. 1997;277(7):553–559. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.7.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ambady N., Laplante D., Nguyen T., Rosenthal R., Chaumeton N., Levinson W. Surgeons' tone of voice: a clue to malpractice history. Surgery. 2002;132(1):5–9. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.124733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hickson G.B., Clayton E.W., Githens P.B., Sloan F.A. Factors that prompted families to file medical malpractice claims following perinatal injuries. JAMA. 1992;267(10):1359–1363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vincent C., Young M., Phillips A. Why do people sue doctors? A study of patients and relatives taking legal action. Lancet. 1994;343(8913):1609–1613. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)93062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forster H.P., Schwartz J., DeRenzo E. Reducing legal risk by practicing patient-centered medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(11):1217–1219. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.11.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brenner R.J., Bartholomew L. Communication errors in radiology: a liability cost analysis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2005;2(5):428–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Queen D., Trager M.H., Fan W., Samie F.H. Patient satisfaction of general dermatology providers: a quantitative and qualitative analysis of 38,008 online reviews. JID Innov. 2021;1(4):100049. doi: 10.1016/j.xjidi.2021.100049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee M.S., Nambudiri V.E. Beyond burnout: talking about physician suicide in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(4):1055–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Moll E.H. Physician burnout in dermatology. Cutis. 2018;102(1):E24–E25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neville K., Cole D.A. The relationships among health promotion behaviors, compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in nurses practicing in a community medical center. JONA: J Nurs Adm. 2013;43(6):348–354. doi: 10.1097/nna.0b013e3182942c23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harvey V.M., Ozoemena U., Paul J., Beydoun H.A., Clemetson N.N., Okoye G.A. Patient-provider communication, concordance, and ratings of care in dermatology: results of a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22(11) 13030/qt06j6p7gh. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper L.A., Roter D.L., Johnson R.L., Ford D.E., Steinwachs D.M., Powe N.R. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):907–915. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desai S.R., Khanna R., Glass D., et al. Embracing diversity in dermatology: Creation of a culture of equity and inclusion in dermatology. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7(4):378–382. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grossman S.K., Schut C., Kupfer J., Valdes-Rodriguez R., Gieler U., Yosipovitch G. Experiences with the first eczema school in the United States. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36(5):662–667. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wong J.L.C., Vincent R.C., Al-Sharqi A. Dermatology consultations: how long do they take? Future Hosp J. 2017;4(1):23–26. doi: 10.7861/futurehosp.4-1-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McLellan C., O'Neil A.I., Cameron M., et al. Facilitating informed treatment decisions in acne: a pilot study of a patient decision aid. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23(1):117–118. doi: 10.1177/1203475418795819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Renzi C., Di Pietro C., Gisondi P., et al. Insufficient knowledge among psoriasis patients can represent a barrier to participation in decision-making. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86(6):528–534. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strober B., van de Kerkhof P.C.M., Callis Duffin K., et al. Feasibility and utility of the Psoriasis Symptom Inventory (PSI) in clinical care settings: a study from the International Psoriasis Council. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20(5):699–709. doi: 10.1007/s40257-019-00458-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Mik S.M.L., Stubenrouch F.E., Balm R., Ubbink D.T. Systematic review of shared decision-making in surgery. Br J Surg. 2018;105(13):1721–1730. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Franciosi E.B., Tan A.J., Kassamali B., O'Connor D.M., Rashighi M., LaChance A.H. Understanding the impact of teledermatology on no-show rates and health care accessibility: a retrospective chart review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(3):769–771. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwartz P.H. The framing Dilemma: quantitative information, shared decision making, and nudging. Med Decis Making. 2022;42(6):726–728. doi: 10.1177/0272989X221109830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leblang C., Taylor S., Brown A., Knapp J., Jindal M. A structured approach to shared decision making training and assessment of knowledge, attitudes and perception of second year medical students. Med Educ Online. 2022;27(1):2044279. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2022.2044279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Driever E.M., Tolhuizen I.M., Duvivier R.J., Stiggelbout A.M., Brand P.L.P. Why do medical residents prefer paternalistic decision making? An interview study. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):155. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03203-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vermeulen F.M., van der Kraaij G.E., Tupker R.A., et al. Towards more shared decision making in dermatology: develop-ment of evidence-based decision cards for psoriasis and atopic eczema treatments. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100(19) doi: 10.2340/00015555-3614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galli E., Neri I., Ricci G., et al. Consensus conference on clinical management of pediatric atopic dermatitis. Ital J Pediatr. 2016;42:26. doi: 10.1186/s13052-016-0229-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feng H., Berk-Krauss J., Feng P.W., Stein J.A. Comparison of dermatologist density between urban and rural counties in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(11):1265. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.3022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tan S.Y., Tsoucas D., Mostaghimi A. Association of dermatologist density with the volume and costs of dermatology procedures among medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(1):73. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.4546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]