Abstract

A detailed kinetic investigation of As(III) oxidation was performed on gold surface within pH between ∼3.0 and ∼9.0. It was found that the As(III) oxidation on the gold surface follows a purely adsorption-controlled process irrespective of pH. The evaluated adsorption equilibrium constant decreased from 3.21 × 105 to 1.61 × 105 mol L−1 for acidic to basic medium, which implies the strong affinity of the arsenic species in the acidic medium. Besides, the estimation of Gibbs free energy revealed that an acidic medium promotes arsenic oxidation on gold surface. In mechanistic aspect, the oxidation reaction adopts a stepwise pathway for acidic medium and a concerted pathway for neutral and basic medium. From the substantial kinetic evaluation, it is established that a conducive and compatible environment for the oxidation of arsenic was found in an acidic medium rather than a basic or neutral medium on gold surface. Besides, in sensitivity concern, neutral and highly acidic medium is quite favourable for the arsenite oxidation on gold surface.

Keywords: pH study, Arsenic oxidation, Au electrode, Kinetics, Sensitivity

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A systematic kinetic investigation for arsenite oxidation was performed on gold surface from pH ∼3.0 to ∼9.0.

-

•

The oxidation reaction proceeds through a purely adsorption-controlled process.

-

•

The oxidation reaction follows stepwise mechanism for acidic medium and concerted mechanism for basic and neutral medium.

-

•

The kinetic properties and sensitivity were determined for the arsenite oxidation reaction at different pH.

1. Introduction

Arsenic, a metalloid chemical present in groundwater, shares many qualities of metals. It is generally found on the surface and naturally occurs in air, water, soil, and foodstuffs. Anthropogenic contamination can boost its level to a certain extent [1,2]. Because of its function in complex biological and chemical activities, it is found in the environment in different forms of organic and inorganic chemicals. The two oxidation states, As(III) and As(V) are some of the most toxicologically relevant arsenic species out of four oxidation states [3]. Inorganic forms (arsenic trichloride, arsine and arsenic trioxide) of arsenic possess the deadly level of toxicity compared to organo-arsenic compounds by being sixty times more toxic than As(V) [4,5].

In general, many therapeutic or healing agents include arsenic as an essential constituent. Likewise, for the treatment of acute leukaemia, arsenic trioxide is being used. Due to its therapeutic usage, it can deactivate almost two hundred enzymes in our body that are actively engaged in cellular energy as well as DNA repairment pathways [6]. Recently, scientific communities have become concerned about the poisoning of the food chain by arsenic-laced water. As well as being primary source of drinking water, ground water contamination with arsenic also raises the eyebrows of people across the world [7,8]. Moreover, there remains a substantial amount of information pertaining to the cancer-causing role of arsenic and its link to a huge number of people suffering from critical diseases, as well as unfavourable skin consequences such as hyperkeratosis and depigmentation [5,9]. As a result of these findings, the US EPA has revised the acceptable limit of arsenic for safe drinking water to be 10 μgL−1 [10]. The situation regarding arsenic contamination in Bangladesh is a genuine concern because of the fact that more than thirteen thousand households are in jeopardy of surpassing the optimum level of arsenic standard for drinking water. The nationwide sporadic screening revealed that more than 80% of the villages tube wells were contaminated, which are termed “hotspots” in the southern and middle portions of the country. Consequently, the predominance of inorganic arsenic poses a significant risk factor to the health of the people of Bangladesh as well as global aspect [[11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]].

Concerning this, sensors such as spectroscopic [[20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]], nanobionic [26], optical [[27], [28], [29], [30]], and aptameric [[31], [32], [33], [34], [35]] are quite customary for all along arsenic detection. Aside from that, electrochemical detection is quite prominent due to its inherent advantages of portability, automation, highly sensitive detection, ease of preparation, and operational simplicity. Moreover, with the advancement of the nano-field, the synthesis of multivariant electrode materials is making it more feasible for selective and low limit of detection of arsenic. Loads of research has already been performed regarding the oxidation of arsenite on different types of electrodes [[36], [37], [38], [39], [40], [41]]. However, the kinetics of arsenite oxidation on Au surface at variable pH are yet to be studied. In this article, a detailed kinetic investigation along with sensitivity has been reported based on data received using voltammetric diagnosis at different pH.

2. Experimental

Sodium arsenite (NaAsO2), Disodium phosphate (Na2HPO4), Monosodium phosphate (NaH2PO4), Sulphuric acid (H2SO4), Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), Acetone (CH3)2CO, and Alumina powder (Al2O3) were brought from Merck, Germany. No additional purification was needed for the chemicals as of being analytical standard. Millipore Milli-Q water of 18.2 M Ω cm (Smart-Q30UT deionized water system, Qingdao, Shandong, China) was used to prepare all the required solutions. pH adjustment was achieved with suitable additions of acidic and basic buffer solutions.

All the experimental works were conducted with a CHI 660E electrochemical workstation (CH Instruments, USA) and Wave Driver 10 (Pine Research Instrumentation, USA) using typical three-electrode system. A gold (Au) disc electrode (0.2 mm of diameter) was employed for performing overall experimental actions. A counter electrode of Pt wire and Ag/AgCl (sat. KCl) were used as a reference electrode, respectively. All potentials here are referenced to the Ag/AgCl (sat. KCl) electrode. The surface of the gold electrode was polished and electrochemically cleaned, similar to the techniques described elsewhere in literature [42]. The total volume of the solution taken for each voltammetric experiment was 10 mL. Prior to the measurements, each solution was purged with N2 to stay out of any additional interferance.

3. Results and discussion

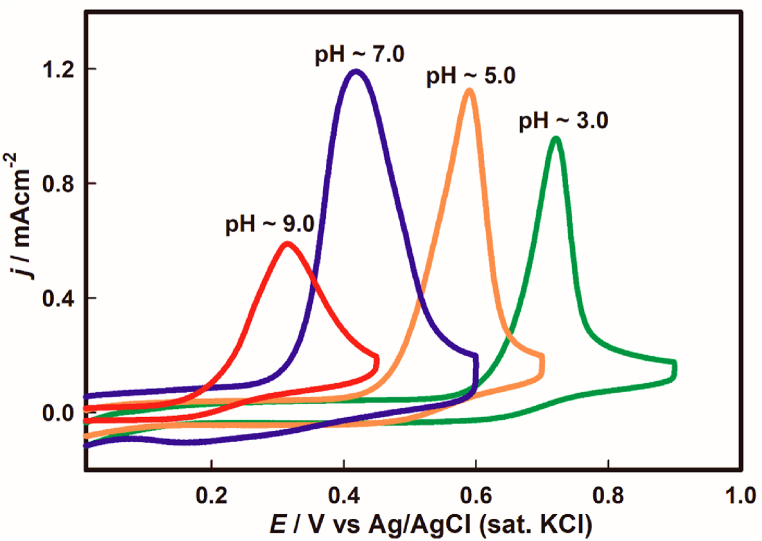

Cyclic voltammograms of the oxidation of 0.5 mM As(III) solution were recorded using a gold electrode under variable pH conditions from ∼3.0 to ∼9.0 at 100 mVs−1 scan rate. From Fig. 1, it is apparent that arsenic oxidation follows a pH dependent trend regarding potential switch during positive going scan and almost no subsequent reduction peak was observed in the reverse scanning.

Fig. 1.

Cyclic voltammograms of 0.5 mM of As(III) oxidation on Au electrode surface at different pH values at 100 mVs−1 scan rate.

Here, the potential has an interesting relationship pertaining to the oxidation of arsenic at the Au electrode from acidic to basic pH. Clearly, the electrostatic energy contribution is comparatively much higher for acidic pH than that of basic pH conditions in regards of As(III) oxidation. Moreover, a distinct comparison of the voltammetric features at different pH are tabulated in Table 1 for the 0.5 mM As(III) oxidation.

Table 1.

Voltammetric properties of 0.5 mM of As(III) oxidation on Au electrode at different pH.

| Voltammetric properties at different pH | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | j (mAcm−2) | Eonset (V) | Ep (V) | RSDa (%) |

| 3.0 | 0.96 | 0.58 | 0.72 | 2.63 |

| 5.0 | 1.12 | 0.45 | 0.59 | 2.86 |

| 7.0 | 1.19 | 0.27 | 0.41 | 3.01 |

| 9.0 | 0.60 | 0.15 | 0.31 | 2.12 |

The value reflects the precision of three consecutive findings.

3.1. Effect of concentration

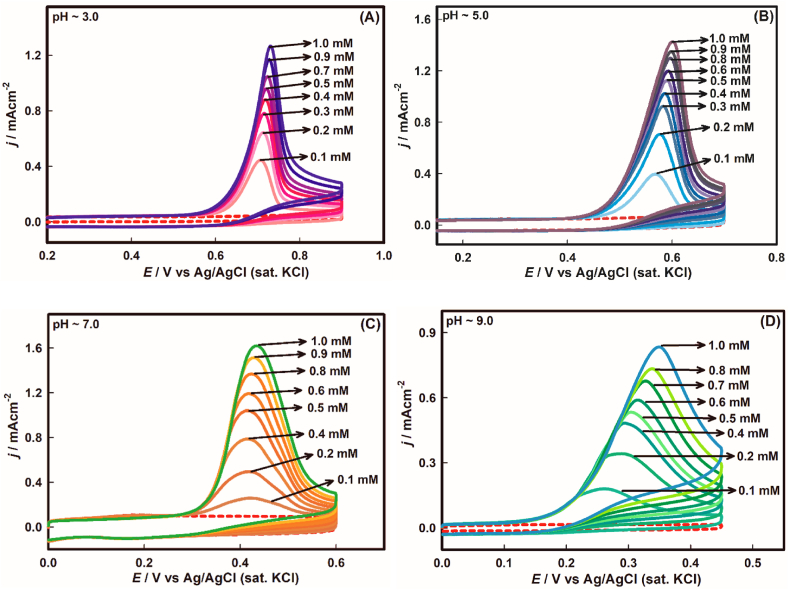

Concentration variant cyclic voltammograms of As(III) oxidation were recorded at different pH using Au electrode at 100 mVs−1 scan rate as can be seen from Fig. 2(A-D). Apparently in each case of pH, peak current density, jp, shoots up with the increment of As(III) concentration. It is noticeable that the peak potential has slight variation from pH ∼3.0 to ∼7.0 but in case of pH ∼9.0, a distinctive shift of potential is visible with the addition of As(III) concentration where concentration overpotential was needed. Moreover, the onset potential shifted to lower value from acidic to basic conditions pertaining to the As(III) oxidation. In general, the effects of concentration against potential have significant importance in kinetic appreciation. In this regard, the kinetic properties were unveiled using this effect in the later sections.

Fig. 2.

Concentration dependent CVs of As(III) oxidation on Au electrode surface at the pH value of (A) ∼3.0, (B) ∼5.0, (C) ∼7.0, and (D) ∼9.0 at 100 mVs−1 scan rate.

Later, the linear sweep voltammograms (see Fig. S1(A-D) of supplementary material) were recorded to check out the sensitivity at variable pH environment from the slope of the linear relationship of current density against concentration (see Fig. S2(A-D) of supplementary material). The sensitivity was found to be 1.4, 0.53, 4.78 and 0.76 mA cm−2 mM−1 for pH ∼3.0, ∼5.0, ∼7.0 and ∼9.0, respectively. That means for the oxidation of arsenite, gold electrode is highly sensitive at neutral medium and then at highly acidic medium. Besides, the electrode is not quite sensitive at pH ∼5.0 and ∼9.0, compared to other medium.

3.2. Effect of scan rates

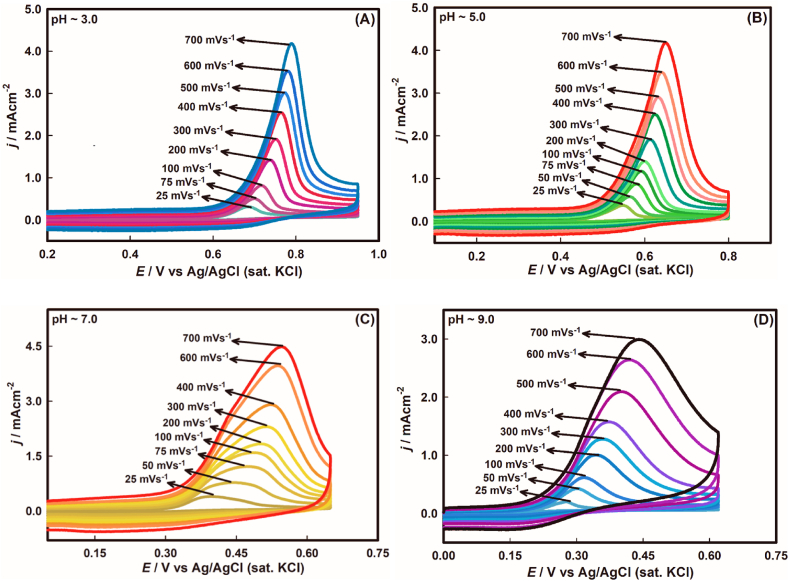

To elucidate the intrinsic features of electrochemical reactions, especially kinetic and mechanistic aspect, effects of scan rate have crucial importance. Hence, the dependency of peak current density with respect to scan rate was recorded as shown in Fig. 3(A-D). It is discernible in the case of each pH value that peak current density amplifies with the consecutive increment of scan rates. This observation endorses the fact that the decrement of the diffusion layer thickness takes place with the increment of scan rates, which turns out to be the increment of current density.

Fig. 3.

Scan rate dependent CVs of 1.0 mM of As(III) oxidation on Au electrode surface at variable pH.

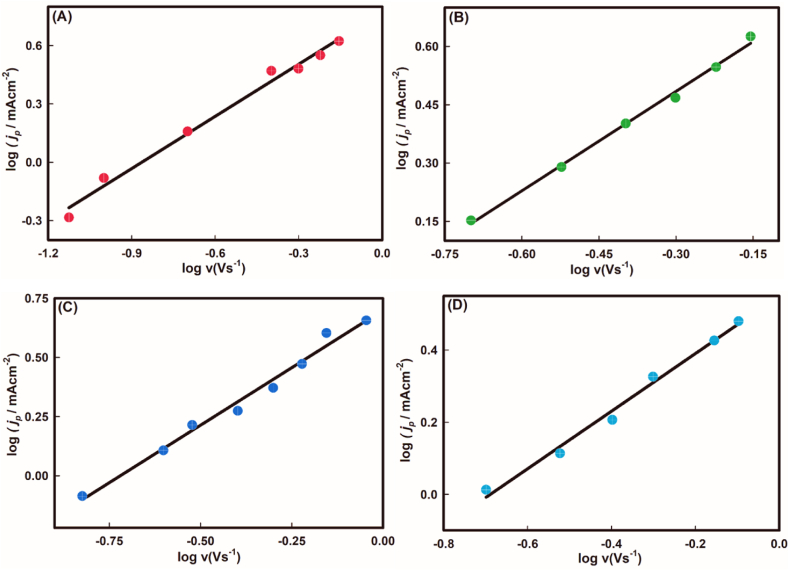

Primarily, the impact of scan rate on kinetic behaviour was examined to assume the surface phenomena, whether diffusion or adsorption-controlled process. From the logarithm of current density against logarithm of scan rate (see Fig. 4(A-D)), the slope for consecutive pH values were found to be 0.89, 0.85, 0.97, 0.81 as given in eqs. (1), (2), (3), (4). Herein, the fractional values signify that the oxidation of As(III) on gold surface is typically an adsorption-controlled process where the electroactive species of As adsorbs from the bulk solution to the planar electrode surface [43].

Fig. 4.

Plots of logarithm of current density, jp, against logarithm of scan rate at variable pH values where (A) pH ∼3.0, (B) pH ∼5.0, (C) pH ∼7.0 and (D) pH ∼9.0.

Linear data fit yields the equations for the consecutive pH values,

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

3.3. Kinetics

Next, it is imperative to unfold the kinetic and mechanistic properties by taking advantage of the effect of concentration as well as scan rates at different pH regarding arsenic oxidation. Here, employing the modified Langmuir eq. (5) [44], the adsorption equilibrium constant was determined by plotting [As(III)]/jp against [As(III)] as shown in Fig. 5(A-D).

| (5) |

Where, b implies the adsorption equilibrium constant, jp and jp. max represent the current density and maximum current density, respectively, at peak potential. Using the slope and the intercept of the plots in Fig. 5(A-D), the adsorption equilibrium constant was determined as tabulated in Table 2. The evaluated adsorption equilibrium constant in acidic medium was found to be almost two times more than in basic medium, which implies the strong affinity of the arsenic species in acidic medium.

Fig. 5.

Plots of [As(III)]/jp, against [As(III)] using the modified Langmuir equation at (A) pH ∼3.0, (B) pH ∼5.0, (C) pH ∼7.0, and (D) pH ∼9.0.

Table 2.

Typical kinetic properties for As(III) oxidation at different pH using Au electrode.

| Kinetic properties at different pH | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | b (molL−1) × 105 | ΔG0 (kJmol−1) | (molcm−2) × 10−9 |

| 3.0 | 3.21 (±0.8) | −31.15 (±0.5) | 1.58 (±1.3) |

| 5.0 | 2.78 (±0.6) | −30.56 (±0.4) | 1.43 (±1.2) |

| 7.0 | 1.91 (±0.6) | −29.89 (±0.6) | 1.53 (±0.8) |

| 9.0 | 1.61 (±0.5) | −28.73 (±0.5) | 0.92 (±0.7) |

Later, employing the equilibrium constant for each certain pH values, the change of the Gibbs free energy due to the adsorption of As(III) ions on Au surface, ΔG0 (=−RT ln b) was also estimated (see Table 2). The observation implies that in basic medium, the Gibbs free energy change is higher than that of acidic medium pertaining to the oxidation of As(III) and the reactions require more driving force for the respective oxidation reaction as a matter of fact that the negative hydroxyl ions may repeal the negative As3O4− ions during the continuation of the reaction. Afterwards, the amount of As(III) adsorbed on the gold electrode surface was determined for the each pH values from eq. (6) [45],

| (6) |

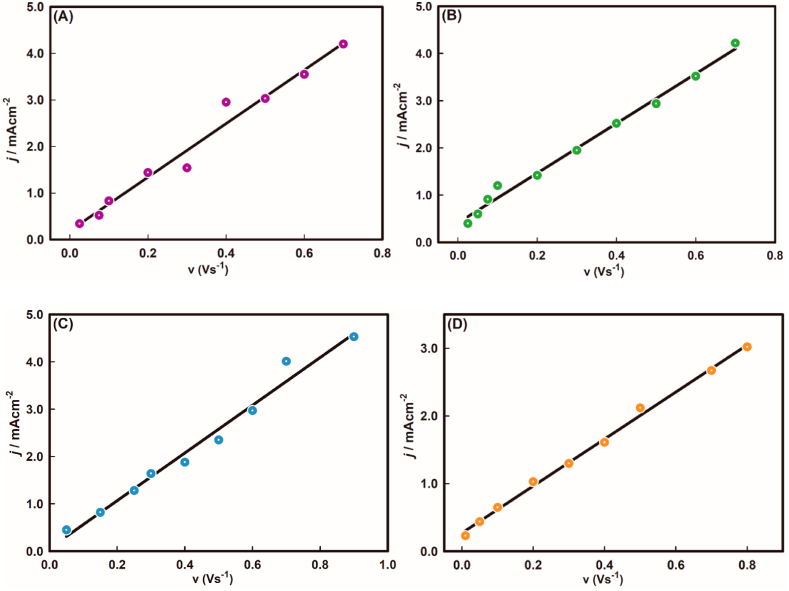

Where, indicates the peak current density, n indicates the number of electrons transferred, indicates the surface coverage of the electrode reaction (molcm−2), F indicates the Faraday constant (96485 C mol−1), R indicates the gas constant (8.314 J K−1 mol−1), v indicates the scan rate (Vs−1) and T indicates the temperature (298 K). Plots of peak current density against the scan rate were drawn (see Fig. 6(A-D)) to calculate the surface concentration of the electrode from the slope values of each plot. The calculated values of are tabulated in Table 2. It is revealed that with the rise in pH values, the surface coverage decreases.

Fig. 6.

Dependency of current density, j against scan rate, v at (A) pH ∼3.0, (B) pH ∼5.0, (C) pH ∼7.0, and (D) pH ∼9.0.

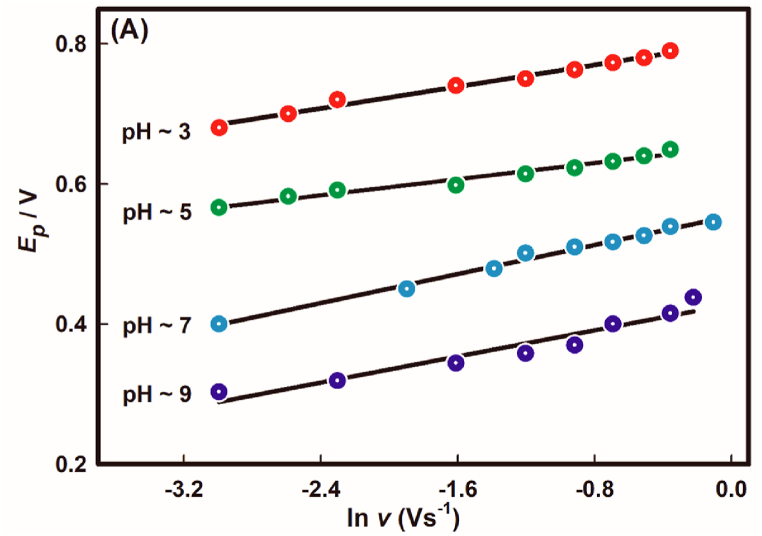

However, for the irreversible surface electrode process of As(III) oxidation on Au surface, eq. (7) [46] could be used for the determination of transfer co-efficient from the slope of Ep against natural logarithm of scan rate,

| (7) |

Here, E0 is the formal potential, β is the transfer coefficient for an anodic process, n is the number of electrons transferred in the rate determining step, which is about to 2 and k0 is the standard heterogeneous rate constant.

The slopes found from Fig. 7 were employed to determine the anodic transfer co-efficient, , of the each pH values pertaining to the oxidation of As(III) using eq. (7). The values were evaluated to be 0.85, 0.78, 0.45 and 0.41 for pH ∼3.0, ∼5.0, ∼7.0 and ∼9.0, respectively. The values indicate that the oxidation of As(III) on Au surface follows step-wise mechanistic pathway for acidic conditions (pH ∼3.0 and ∼5.0) [47]. Conversely, for neutral (pH ∼7.0) and basic medium (pH ∼9.0), the reaction pathway followed concerted mechanism for the concerned oxidation process [48].

Fig. 7.

A plot of peak potential against the logarithm of scan rate of variable pH at 100 mVs−1 scan rate. The experimental conditions are same as mentioned in Fig. 3.

Later, the effect of pH on the potential variation for the oxidation of As(III) was also investigated to look into the proton involvement pertaining to the electrode reaction. It is noticeable from Fig. 8 that the peak potential of As(III) oxidation decreases with the increment of pH.

Fig. 8.

A plot of peak potential (Ep) against pH for As(III) oxidation on Au electrode surface.

A plot of peak potential, Ep, against pH renders a good linear relationship with eq. (8),

| (8) |

Here, the slope found from the relationship is nearly the theoretical value of 59.0 mV pH−1. According to the equation [49], −59.0 m/n = −63.0, where m is the proton participating in the electrode reaction of the As(III) oxidation and n is the number of electron transferred in the oxidation. Note that the ratio of the equation indicates that the number of protons (m) accompanied same number of electrons transferred during the electrode process which was determined to be m = n = 2. That means two electrons were associated with two protons during the electrode reaction of the As(III) oxidation.

4. Conclusion

A systematic kinetic exploration on As(III) oxidation studies were performed using Au electrode from pH ∼3.0 to ∼9.0. The oxidation of As(III) on Au surface is a purely adsorption-controlled process. On top of that, the adsorption equilibrium constant for acidic medium was found almost two times more of basic medium pertaining to the oxidation. The number of electron transfer was also verified that two protons accompanied two electrons in the respective oxidation. Moreover, the oxidation reaction adopts a stepwise pathway for acidic medium, meanwhile for neutral and basic medium, the reaction adopts a concerted pathway. Above all, an acidic medium was found to be more suitable for the concerned oxidation. On extension, further kinetic studies can be performed in gold modified electrode surface for arsenic oxidation at different pH environment by varying temperature.

Author contribution statement

Mohebul Ahsan: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Muhammad Zobayer Bin Mukhlish: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Nazia Khatun: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Mohammad Abul Hasnat: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

Mohammad Abul Hasnat was supported by Shahjalal University of Science and Technology [PS/2022/1/01], Ministry of Science and Technology, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh [SRG-223537, Year 2022], Ministry of Education, Government of the People's Republic of Bangladesh [PS 20201512].

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors indebtedly acknowledge financial supports from Shahjalal University of Science and Technology (Grant No. PS/2022/1/01) along with the partial supports from Ministry of Science and Technology (Project ID: SRG-223537, Year 2022) and the Ministry of Education, Bangladesh (Grant No. PS 20201512).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14192.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Singh R., Singh S., Parihar P., Singh V.P., Prasad S.M. Arsenic contamination, consequences and remediation techniques: a review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2015;112:247–270. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rae I.D. Arsenic: its chemistry, its occurrence in the earth and its release into industry and the environment. ChemTexts. 2020;6:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s40828-020-00118-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kara S., Chormey D.S., Saygılar A., Bakırdere S. Arsenic speciation in rice samples for trace level determination by high performance liquid chromatography-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2021;356 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siddiqui S.I., Chaudhry S.A. A review on graphene oxide and its composites preparation and their use for the removal of As3+ and As5+ from water under the effect of various parameters: application of isotherm, kinetic and thermodynamics. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2018;119:138–163. doi: 10.1016/j.psep.2018.07.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jomova K., Jenisova Z., Feszterova M., Baros S., Liska J., Hudecova D., Rhodes C.J., Valko M. Arsenic: toxicity, oxidative stress and human disease. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2011;31:95–107. doi: 10.1002/JAT.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ratnaike R.N. Acute and chronic arsenic toxicity. Postgrad. Med. 2003;79:391–396. doi: 10.1136/pmj.79.933.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raessler M. The arsenic contamination of drinking and groundwaters in Bangladesh: featuring biogeochemical aspects and implications on public health. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2018;75:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s00244-018-0511-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basu A., Saha D., Saha R., Ghosh T., Saha B. A review on sources, toxicity and remediation technologies for removing arsenic from drinking water. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2014;40:447–485. doi: 10.1007/s11164-012-1000-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kitchin K.T., Wallace K. The role of protein binding of trivalent arsenicals in arsenic carcinogenesis and toxicity. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2008;102:532–539. doi: 10.1016/J.JINORGBIO.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sinha D., Prasad P. Health effects inflicted by chronic low-level arsenic contamination in groundwater: a global public health challenge. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2020;40:87–131. doi: 10.1002/jat.3823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith A.H., Lingas E.O., Rahman M. Contamination of drinking-water by arsenic in Bangladesh: a public health emergency. Bull. World Health Organ. 2000;78:1093–1103. doi: 10.1590/S0042-96862000000900005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brinkel J., Khan M.H., Kraemer A. A systematic review of arsenic exposure and its social and mental health effects with special reference to Bangladesh. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2009;6:1609–1619. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6051609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Argos M., Kalra T., Pierce B.L., Chen Y., Parvez F., Islam T., Ahmed A., Hasan R., Hasan K., Sarwar G., Levy D., Slavkovich V., Graziano J.H., Rathouz P.J., Ahsan H. A prospective study of arsenic exposure from drinking water and incidence of skin lesions in Bangladesh. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011;174:185–194. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahmed M.K., Shaheen N., Islam M.S., Habibullah-al-Mamun M., Islam S., Mohiduzzaman M., Bhattacharjee L. Dietary intake of trace elements from highly consumed cultured fish (Labeo rohita, Pangasius pangasius and Oreochromis mossambicus) and human health risk implications in Bangladesh. Chemosphere. 2015;128:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed M.K., Shaheen N., Islam M.S., Habibullah-Al-Mamun M., Islam S., Islam M.M., Kundu G.K., Bhattacharjee L. A comprehensive assessment of arsenic in commonly consumed foodstuffs to evaluate the potential health risk in Bangladesh. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;544:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.11.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosler H.J., Blöchliger O.R., Inauen J. Personal, social, and situational factors influencing the consumption of drinking water from arsenic-safe deep tubewells in Bangladesh. J. Environ. Manag. 2010;91:1316–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanchett S., Nahar Q., Van Agthoven A., Geers C., Rezvi F.J. Increasing awareness of arsenic in Bangladesh: lessons from a public education programme. Health Pol. Plann. 2002;17:393–401. doi: 10.1093/heapol/17.4.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karim M.M. Arsenic in groundwater and health problems in Bangladesh. Water Res. 2000;34:304–310. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(99)00128-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmad S.A., Khan M.H., Haque M. Arsenic contamination in groundwater in Bangladesh: implications and challenges for healthcare policy. Risk Manag. Healthc. Pol. 2018;11:251–261. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S153188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mulvihill M., Tao A., Benjauthrit K., Arnold J., Yang P. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy for trace arsenic detection in contaminated water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6456–6460. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haider A.F.M.Y., Hedayet Ullah M., Khan Z.H., Kabir F., Abedin K.M. Detection of trace amount of arsenic in groundwater by laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy and adsorption. Opt Laser. Technol. 2014;56:299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.optlastec.2013.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.del González-Chávez M.C.A., Miller B., Maldonado-Mendoza I.E., Scheckel K., Carrillo-González R. Localization and speciation of arsenic in Glomus intraradices by synchrotron radiation spectroscopic analysis. Fungal Biol. 2014;118:444–452. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hao J., Han M.J., Han S., Meng X., Su T.L., Wang Q.K. SERS detection of arsenic in water: a review. J. Environ. Sci. (China) 2015;36:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howard A.G., Arbab-Zavar M.H. Determination of “inorganic” arsenic(lll) and arsenic(v), “methylarsenic” and “dimethylarsenic” species by selective hydride evolution atomicabsorption spectroscopy. Analyst. 1981;106:213–220. doi: 10.1039/AN9810600213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gómez-Ariza J.L., Sánchez-Rodas D., Giráldez I., Morales E. A comparison between ICP-MS and AFS detection for arsenic speciation in environmental samples. Talanta. 2000;51:257–268. doi: 10.1016/S0039-9140(99)00257-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lew T.T.S., Park M., Cui J., Strano M.S. Plant nanobionic sensors for arsenic detection. Adv. Mater. 2021;33 doi: 10.1002/adma.202005683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devi P., Thakur A., Lai R.Y., Saini S., Jain R., Kumar P. Progress in the materials for optical detection of arsenic in water. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2019;110:97–115. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2018.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang L., Chen X.R., Wen S.H., Liang R.P., Qiu J.D. Optical sensors for inorganic arsenic detection. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 2019;118:869–879. doi: 10.1016/j.trac.2019.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wen S., Zhu X. Speciation of inorganic arsenic(III) and arsenic(V) by a facile dual-cloud point extraction coupled with inductively plasma-optical emission spectrometry. Talanta. 2018;181:265–270. doi: 10.1016/J.TALANTA.2017.12.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Rekabi S.H., Mustapha Kamil Y., Abu Bakar M.H., Yap W.F., Lim H.N., Kanagesan S., Mahdi M.A. Hydrous ferric oxide-magnetite-reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite for optical detection of arsenic using surface plasmon resonance. Opt Laser. Technol. 2019;111:417–423. doi: 10.1016/j.optlastec.2018.10.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mao K., Zhang H., Wang Z., Cao H., Zhang K., Li X., Yang Z. Nanomaterial-based aptamer sensors for arsenic detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020;148 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2019.111785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu Y., Liu L., Zhan S., Wang F., Zhou P. Ultrasensitive aptamer biosensor for arsenic(iii) detection in aqueous solution based on surfactant-induced aggregation of gold nanoparticles. Analyst. 2012;137:4171–4178. doi: 10.1039/c2an35711a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhan S., Yu M., Lv J., Wang L., Zhou P. Colorimetric detection of trace arsenic(III) in aqueous solution using arsenic aptamer and gold nanoparticles. Aust. J. Chem. 2014;67:813–818. doi: 10.1071/CH13512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oroval M., Coll C., Bernardos A., Marcos M.D., Martínez-Máñez R., Shchukin D.G., Sancenón F. Selective fluorogenic sensing of as(III) using aptamer-capped nanomaterials. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9:11332–11336. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b15164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan J., Li Q., Zhou D., Chen J. Ultrasensitive aptamer biosensor for arsenic (III) detection based on label-free triple-helix molecular switch and fluorescence sensing platform. Talanta. 2018;189:370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kedzierzawski P., Szklarska-Smiałowska Z. Oxidation of As3+ to As5+ on a gold electrode in aqueous solutions. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 1981;122:269–278. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0728(81)80157-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dai X., Nekrassova O., Hyde M.E., Compton R.G. 2004. Anodic Stripping Voltammetry of Arsenic(III) Using Gold Nanoparticle-Modified Electrodes. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Majid E., Hrapovic S., Liu Y., Male K.B., Luong J.H.T. Electrochemical determination of arsenite using a gold nanoparticle modified glassy carbon electrode and flow analysis. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:762–769. doi: 10.1021/AC0513562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang M., Li P.H., Xu W.H., Wei Y., Li L.N., Huang Y.Y., Sun Y.F., Chen X., Liu J.H., Huang X.J. Reliable electrochemical sensing arsenic(III) in nearly groundwater pH based on efficient adsorption and excellent electrocatalytic ability of AuNPs/CeO2-ZrO2 nanocomposite. Sensor. Actuator. B Chem. 2018;255:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2017.07.204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rassaei L., Sillanpää M., French R.W., Compton R.G., Markenc F. Arsenite determination in phosphate media at electroaggregated gold nanoparticle deposits. Electroanalysis. 2008;20:1286–1292. doi: 10.1002/elan.200804226. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sánchez J.A., Rivas B.L., Pooley S.A., Basaez L., Pereira E., Pignot-Paintrand I., Bucher C., Royal G., Saint-Aman E., Moutet J.C. Electrocatalytic oxidation of As(III) to As(V) using noble metal-polymer nanocomposites. Electrochim. Acta. 2010;55:4876–4882. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2010.03.080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li D., Li J., Jia X., Han Y., Wang E. Electrochemical determination of arsenic(III) on mercaptoethylamine modified Au electrode in neutral media. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2012;733:23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allen L.R.F., Bard J. second ed. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2020. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brylev O., Sarrazin M., Bélanger D., Roué L. Rhodium deposits on pyrolytic graphite substrate: physico-chemical properties and electrocatalytic activity towards nitrate reduction in neutral medium. Appl. Catal., B. 2006;64:243–253. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2005.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laviron E. Adsorption, autoinhibition and autocatalysis in polarography and in linear potential sweep voltammetry. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1974;52:355–393. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0728(74)80448-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laviron E. General expression of the linear potential sweep voltammogram in the case of diffusionless electrochemical systems. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1979;101:19–28. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0728(79)80075-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mumtarin Z., Rahman M.M., Marwani H.M., Hasnat M.A. Electro-kinetics of conversion of NO3− into NO2− and sensing of nitrate ions via reduction reactions at copper immobilized platinum surface in the neutral medium. Electrochim. Acta. 2020;346 doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2020.135994. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hasnat M.A., Hasan M.M., Tanjila N., Alam M.M., Rahman M.M. pH dependent kinetic insights of electrocatalytic arsenite oxidation reactions at Pt surface. Electrochim. Acta. 2017;225:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2016.12.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nicholson R.S. Theory and application of cyclic voltammetry for measurement of electrode reaction kinetics. Anal. Chem. 1965;37:1351–1355. doi: 10.1021/ac60230a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.