Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases remain the leading cause of death, morbidity, and disability. Recently, it has been reported that gonadal hormones such as estradiol can act on membrane receptors and activate intracellular signaling mechanisms, thereby altering cellular function. This study aims to explore the function and molecular mechanism of estradiol on cardiac microvascular endothelial cells (CMVECs). Estradiol had low toxicity to CMVECs. Hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) stimulation inhibited the proliferation and migration of CMVECs, while estradiol significantly promoted proliferation and migration. Estradiol inhibited il-1, IL6, and TNF-α secretion levels after H/R stimulation. Meanwhile, estradiol inhibits oxidative stress and promotes angiogenesis. Further, estradiol upregulated the gene and protein levels of cyclin-dependent kinases 1 (CDK1) and CDK2 after H/R stimulation. When knocking down CDK1 and CDK2 of CMVECs, estradiol did not affect the protein expression of Cyclin E1 and Cyclin D1. Meanwhile, the regulatory effect of estradiol on oxidative stress, angiogenesis, and inflammatory response was significantly weakened or even disappeared. In conclusion, estradiol mediates oxidative stress and angiogenesis of myocardial microvascular endothelial cells by regulating the CDK/cyclin signaling pathway.

Keywords: Cardiovascular diseases, Estradiol, CDK, Oxidative stress, Angiogenesis

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a common disease that seriously threatens human life and health [1]. Cardiovascular disease is more common, disabling, and deadly in older people than younger people [2]. The cardiovascular disease currently kills more than 17 million people each year. The morbidity and mortality of CVD are high in many countries and regions [3,4]. CVD accounts for over 31% of global deaths [1]. With the aging of society, the morbidity and mortality of cardiovascular diseases continue to rise.

Various CVDs (such as Arrhythmia, Myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, hypertension, cardiomyopathy, etc.) are associated with endothelial dysfunction [5]. Endothelial cells can phagocytose foreign bodies, bacteria, and necrotic and aging tissues and participate in the body’s immune function. Hypoxia/reperfusion is the main treatment for ischemic cardiovascular disease [6]. Cardiac microvascular endothelial cells (CMVECs) are sensitive to hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) induced injury [7]. H/R exposure can damage various physiological activities of endothelial cells, including reduced cell survival rate, dysregulation of energy metabolism, impaired angiogenesis, excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and mitochondrial dysfunction [8]. Notably, H/R stimulation has also been shown to trigger the overproduction of pro-inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-8 (IL-8). H/R exposition-induced CMVEC damage has been shown to be associated with several intracellular signaling pathways. Activation of p38 acts a vital role in regulating oxidative stress and inflammatory response [9,10]. In addition, H/R exposure activates nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), which mediates intracellular inflammatory signaling [11]. CMVEC has also been found to have enzyme activity, especially Angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE) activity, which regulates local angiotensin II and bradykinin levels in the heart [12].

Estradiol (E2) is one of the female estrogens. Recently, it has been reported that gonadal hormones such as estradiol can act on membrane receptors and activate intracellular signaling mechanisms, thereby altering cellular function [13]. For example, E2 prevents ischemia/reperfusion injury (IRI)-induced renal dysfunction and tissue damage [14]. Most kidney complications have a high incidence in men than in women. E2 maintains endothelial nitric oxide synthase (ENOS) activity through both genomic and non-genomic signaling pathways, which is crucial in maintaining normal endothelial function. Genomic E2 signaling mainly involves the binding of estradiol to nuclear estrogen receptor α (ERα) and/or estrogen receptor β (ERβ). Dimerization of E2-Erα or E2-Erβ binds estrogen response elements to increase transcriptional activity associated with ENOS production [[15], [16], [17]]. Non-genomic E2 signaling pathways may involve plasma membrane binding ERα, plasma membrane binding, or endoplasmic reticulum binding G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) [18,19]. Thus, E2 activation of ENOS may block cardiomyocyte growth and left ventricular hypertrophy by regulating the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and nutrient activity [20]. Estradiol-bound estrogen receptors regulate the activity of NF-κB and other transcription factors [21]. In addition, E2 may increase the synthesis of IκB and inhibit NF-κB transcriptional binding in vascular smooth muscle via ERβ [22,23].

In this study, we evaluated the effect and mechanisms of E2 on CMVEC injury in a hypoxia/reoxygenation model. We found that E2 effectively inhibits reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels and cellular inflammation and promotes angiogenesis. Furthermore, E2 can promote the expression of cyclin in CMVECs after H/R stimulation. While knockdown of CDK1 and CDK2 reverses the regulation of E2 on CMVECs. In conclusion, E2 mediates oxidative stress and angiogenesis of myocardial microvascular endothelial cells by regulating the expression of CDK1/CDK2.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture and treatment

The Cardiac microvascular endothelial cells (CMVECs) (ATCC, USA) were cultured in DMEM medium (Sigma-Aldrich, MO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Grand Island, NY) with 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The cells were inoculated into 6-well plates or 10 cm dishes. Subsequent experiments were performed when the cells proliferated to 70% of the culture dish.

2.2. Hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) experiment

Isolated CMVECs were pre-incubated with estradiol or the same concentration of DMSO vehicles for 12 h. H/R experiments were performed by placing cells in a sealed chamber with pure N2, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 6 h. Cells were cultured in a normal medium and reoxygenated in normal incubator (95% air + 5% CO2) for 12 h.

2.3. Cell transfection

Control siRNA, siCDK1 and siCDK2 were obtained from Sangon (Shanghai, China) and were transfected into the RCC cell lines using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The effects of silencing were monitored by qRT-PCR. GCUGUACUUCGUCUUCUAAUU and GCCUGAUUACAAGCCAAGUUU were used for CDK1 siRNA and CDK2 siRNA, respectively. MISSION siRNA Universal Negative Control #1 (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a negative control.

2.4. Cell proliferation

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) assay was applied to test the CMVECs' growth. Briefly, cells were seeded in a 96-well plate. After 24 h, cells were treated with E2 for 0 h, 24 h, and 48 h. Add 10 μL of CCK8 solution to each well and incubate for 1 h The absorbance was read at 550 nm using a microplate reader (Thermofisher, USA).

2.5. Wound healing assay

The CMVECs were inoculated into about six-well plates. Cell starvation lasting 8 h, with FBS-free experimental medium, was performed to stop cell proliferation. Next, a wound was made by scratching the monolayer cells with a sterile 10 μL pipette tip, and, after washing, the medium was changed to 0.1% FBS experimental medium containing 150 nM estradiol. Samples were photographed at 0 and 24 h.

2.6. Transwell assay

The CMVECs without FBS was inoculated into the upper chamber of the transwell cell, and a medium containing 10% FBS was added into the lower chamber. After 12 h of routine culture, H/R stimulation and E2 were given for 48 h 48 h later, the cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet. Under the microscope, select five fields (top, bottom, left, right, middle) and take pictures.

2.7. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, USA). Then, mRNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA with the GoldScript one-step RT-PCR kit. RT-qPCR was conducted on an ABI7500 RT-qPCR machine with an SYBR premix Ex Taq™ II PCR Kit. The results of CDK1 and CDK2 expression were normalized to GAPDH expression. The relative expression was calculated by 2−ΔΔCt method. The PCR primers were designed and synthesized by Sangon (Shanghai, China) and were listed below: GAPDH: 5′-AGAAGGCTGGGGCTCATTTG-3′, 5′-AGGGGCCATCCACAGTCTTC-3′; CDK1: 5′-TAGCGCGGATCTACCATACC-3′, 5′-CATGGCTACCACTTGACCTGT-3′; CDK2: 5′-CAGGATGTGACCAAGCCAGT-3′, 5′-TGAGTCCAAATAGCCCAAGG-3′.

2.8. Western blot assay

Cells were collected and added RIPA lysis buffer (Invitrogen, USA) for half an hour. The samples were centrifuged at 12000 rpm at 4 °C for 20 min and measured by the quantitative method of bicinchoninic acid (BCA, Vazyme, China). The samples with 30 μg total protein were separated on SDS-PAGE (Invitrogen, USA) and transferred to the PVDF membrane. 5% skim milk blocked protein expressions for 1 h at room temperature (RT). Primary antibody, CDK1 (CST, USA), CDK2 (CST, USA), Cyclin D1 (CST, USA), Cyclin E1 (CST, USA), GAPDH (CST, USA) was incubated overnight at 4 °C; and the secondary antibody was incubated for 1 h at RT. The membranes were visualized using Pierce® ECL Western Blot.

2.9. Tube formation assay

For tube formation analysis, the substrate (Becton Dickinson Labware, USA) was incubated in a CO2-free incubator at 37 °C for 30–60 min. CMVECs were transferred to the gel at 37 °C, incubated with 5% CO2 for 48 h, and fixed with 4% formaldehyde. Using OpenLab (Improvision, UK) to obtain images of four fields of each gel, measure the total length of the string formed by each well, and determine the average length of each well-type formation.

2.10. Measurement of ROS level

Intracellular ROS levels were investigated by fluorescence imaging. After incubation for 1 and 6 h, the disks were washed with PBS, and 300 μL of DCFH-DA (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the disk surface, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 30 min. Excess dye was removed by washing with PBS and the samples were examined with a confocal laser scanning microscope.

2.11. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The level of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α secretion in the human cells and liver tissues were analyzed using a Human or mouse ROS ELISA kit (Dakewe Biotech, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The optical density measured the absorbance at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

2.12. Statistical analysis

All statistical tests were performed with Sigma Plot 14.0. Data were presented by means ± SD from triplicate experiments. Statistical significance was performed using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test for two data sets when the data met the normal distribution tested by F-test.

3. Results

3.1. Estradiol regulated the proliferation and migration of myocardial microvascular endothelial cells (CMVECs) after hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) injury

CCK-8 kit detected the effect of E2 on the proliferation of CMVECs. The cells were incubated with E2 at 50, 100, and 150 nM for 0, 24, and 48 h, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1A, the concentration of E2 had no significant difference in the proliferation activity of cells. Compared with the control group, the stimulation time of estradiol did not affect cell viability. Therefore, E2 with a concentration of 150 nM was continuously stimulated for 48 h for subsequent experiments. Next, we examined the effect of E2 on the proliferation of CMVECs after hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) injury. As shown in Fig. 1B, E2 up-regulated the proliferation ability of cells inhibited by H/R stimulation. The migration of cells was detected by wound healing and transwell assays. Fig. 1C–F showed that E2 could promote the migration of CMVECs after H/R injury.

Fig. 1.

Estradiol regulated the proliferation and migration of myocardial microvascular endothelial cells (CMVECs) after hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) injury. (A) Cell proliferation was incubated with E2 at a concentration of 50, 100 and 150 nM for 0, 24 and 48 h, respectively. (B) Cell viability was tested by CCK8 assay (****p ≤ 0.0001). (C) Cell migration was determined by wound-healing assay. (D) Quantitative analysis of wound-healing assay. (E) Cell migration was measured by transwell staining. (F) Quantitative analysis of positive transwell staining (**p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001). n = 3.

3.2. Estradiol regulated oxidative stress and angiogenesis of CMVECs

After H/R stimulation, we found that E2 could promote cell proliferation and inhibit cell migration. To further explore the mechanism of E2 regulating proliferation and migration, we first detected the level of reactive oxygen species (ROS). As shown in Fig. 2A and B, E2 effectively down-regulated the level of ROS under hypoxia/reoxygenation condition. The angiogenesis of cells was detected by the tube formation assay. Fig. 2C and D shows that E2 promoted the H/R-inhibited angiogenesis of CMVECs. The regulation of E2 on cellular inflammation was further detected by ELISA. H/R significantly promoted the secretion of IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α. And E2 reversed this phenomenon (Fig. 2E–G).

Fig. 2.

Estradiol inhibits oxidative stress response and promotes angiogenesis after H/R injury. (A) Reactive oxygen species (ROS) level was measured by ROS kits. (B) Quantitative analysis of positive ROS staining. (C) Angiogenesis was determined by tube formation assay. (D) Quantitative analysis of the total length formed by each well (**p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001). (E–G) The expression of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α was monitored by ELISA (***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001). n = 3.

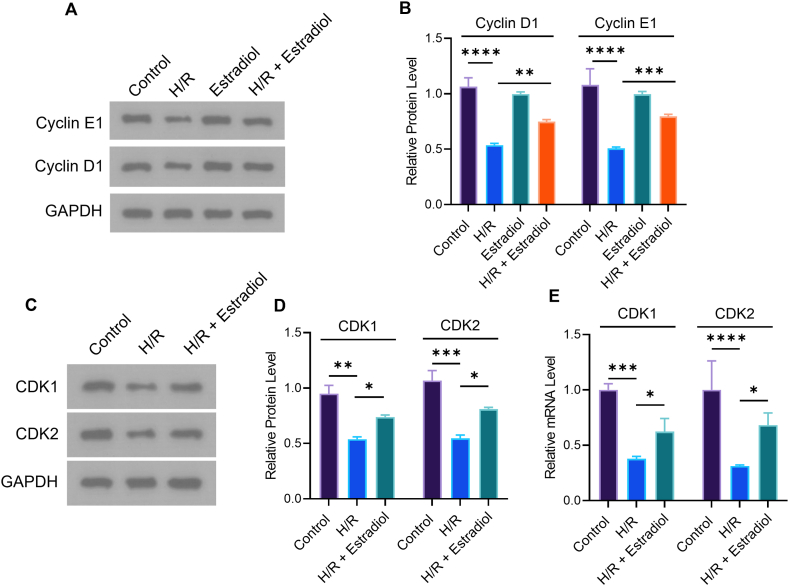

3.3. Estradiol promoted the expression of cyclin and CDK after hypoxia/reoxygenation injury

To further explore how E2 regulates cellular oxidative stress and angiogenesis, we first examined the expression of Cyclin D1 and Cyclin E1 by Western blot assays. As shown in Fig. 3A and B, H/R significantly suppressing the expression of Cyclin D1 and Cyclin E1. And E2 reversed this phenomenon, i.e., E2 promoting the expression of Cyclin D1 and Cyclin E1. We further detected CDK gene and protein levels by RT-PCR and Western blot. Fig. 3E shows that H/R significantly suppressing the expression of CDK1 and CDK2. And E2 reversed this phenomenon, i.e., E2 promoting the expression of CDK1 and CDK2. (Fig. 3C and D).

Fig. 3.

Estradiol promoted the expression of cyclin and CDK after H/R injury. (A) Cyclin D1 and Cyclin E1 protein levels were measured by western blot. (B) Quantitative analysis of protein expression for Cyclin D1 and Cyclin E1. (C) CDK1 and CDK2 protein levels were determined by western blot. (D) Quantitative analysis of protein expression for CDK1 and CDK2. (E) The mRNA level of CDK1 and CDK2 was verified by RT-PCR (***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001). n = 3.

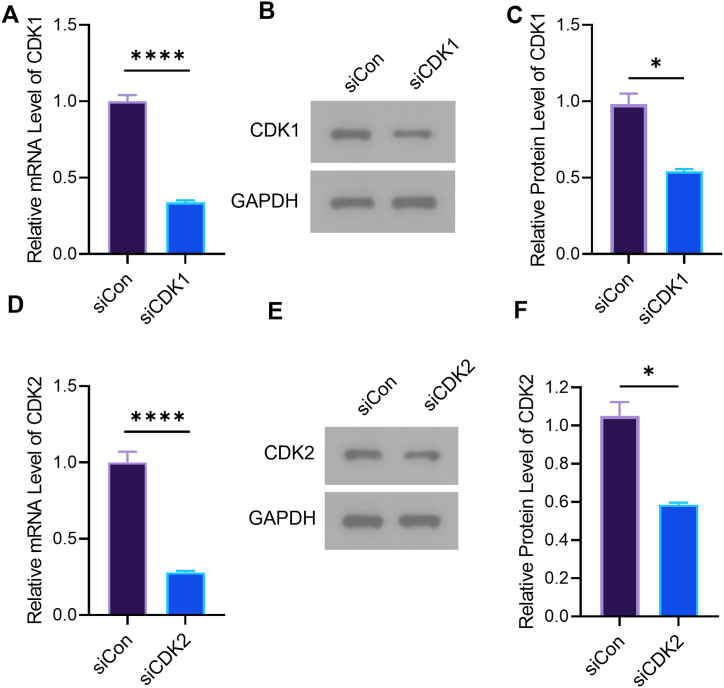

3.4. Knockdown of CDK1 reversed the effect of estradiol on oxidative stress and angiogenesis

To determine whether CDK1 and CDK2 are targets of E2, we first constructed cells with low expression of CDK1. RT-PCR and western blot detected the gene and protein levels of CDK1 and CDK2. CMVECs were transfected with CDK1 and CDK2 siRNA. The gene and protein expression of CDK1 was significantly decreased (Fig. 4A, B, and C). Compared to control cells, the levels of CDK2 gene and protein were significantly lower. (Fig. 4D, E, and F).

Fig. 4.

Knock-down of CDK1 and CDK2 in CMVECs. (A) The gene expression of CDK1 was verified by RT-PCR (****p ≤ 0.0001). (B) The protein expression of CDK1 was monitored by western blot. (C) Quantitative analysis of CDK1 protein level. (D) The gene expression of CDK2 was monitored by was verified by RT-PCR (****p ≤ 0.0001). (E) The protein expression of CDK2 was monitored by western blot. (F) Quantitative analysis of CDK2 protein level. n = 3.

Cells transfected with CDK1 and CDK2 siRNA were used for subsequent exploratory experiments. CCK-8 kit tested the effect of E2 on the proliferation of cells. Compared with the H/R cells, estradiol promoted cell proliferation, and knockdown of CDK1 inhibited the proliferation of cells. E2 had no significant effect on cell proliferation after CDK1 knockdown in H/R model cells (Fig. 5A). E2 can effectively reduce the ROS level under H/R stimulation, and knocking down CDK1 can effectively reverse the inhibitory effect of E2 on ROS (Fig. 5B and C). ELISA results show that knockdown of CDK1 significantly promoted IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α secretion compared with H/R, while estradiol down-regulated IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α secretion. CDK1 knockdown reversed the effect of E2 on the secretion of inflammatory factors (Fig. 5D–F). Fig. 5G and H showed that E2 promoted the H/R-inhibited angiogenesis of CMVECs, and CDK1 knockdown inhibited the effect of E2.

Fig. 5.

Knockdown of CDK1 reversed the effect of estradiol on oxidative stress and angiogenesis. (A) Cell viability was tested by CCK8 assay (****p ≤ 0.0001). (B) ROS level was measured by ROS kit. (C) Quantitative analysis of positive ROS staining. (D–F) The expression of IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α was monitored by ELISA (***p ≤ 0.001, ****p ≤ 0.0001). (G) Angiogenesis was determined by tube formation assay. (H) Quantitative analysis of the total length formed by each well (**p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001). n = 3.

According to wound healing assays and transwell assays, E2 could promote the migration of CMVECs after H/R injury, CDK1 knockdown reversed the effect of E2 (Fig. 6A–D). Western blot was used to detect the expression of Cyclin D1 and Cyclin E1, which shows that knockdown of CDK1 reversed the promoting effect of E2 on Cyclin D1 and Cyclin E1 after H/R injury (Fig. 6E and F).

Fig. 6.

Knockdown of CDK1 reversed the effect of estradiol on cell migration. (A) Cell migration was determined by wound-healing assay. (B) Quantitative analysis of wound-healing assay. (C) Cell migration was measured by transwell staining. (D) Quantitative analysis of positive transwell staining. (E) CDK1 and CDK2 protein levels were determined by western blot. (F) Quantitative analysis of protein expression for CDK1 and CDK2. (**p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001). n = 3.

4. Discussion

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) remain the leading cause of death, morbidity, and disability in our country [24]. CVD causes 3.9 million deaths yearly in Europe, accounting for 45% of all deaths [25]. Furthermore, according to the European International Mortality Statistics, cardiovascular diseases are reported as the leading cause of death, morbidity, and disability in Italy [26]. Ischemia-reperfusion therapy is still the main treatment for ischemic cardiovascular disease [27]. A large number of studies have shown that ischemia-reperfusion therapy easily causes reperfusion injury and inhibits the therapeutic effect. Therefore, inhibition of reperfusion injury and promotion of angiogenesis are the main methods to treat cardiovascular diseases.

Estrogen is the main female steroid hormone and a potent mitogen for endometrial proliferation [28]. Sex differences in myocardial I/R responses are mainly due to estrogen, which is generally accepted by the public [29,30]. E2 can prevent cardiovascular diseases by preventing atherosclerosis and improving coronary insufficiency. Previous studies have shown that E2 enhances the recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) and positively affects angiogenesis in ischemic tissues [31]. CMVECs are an essential cell type from the coronary arteries that play an important role in stimulating angiogenesis and delivering nutrients and oxygen [32]. H/R exposure of CMVECs mimics myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury [33]. Our study shows that high concentrations of E2 did not affect the proliferation of CMVECs, indicating that E2 had low toxicity to CMVECs H/R stimulation inhibited the proliferation and migration of CMVECs, while estradiol significantly promoted proliferation and migration.

H/R stimulation not only affects cell proliferation and migration but also induces oxidative stress, angiogenesis disorder, and inflammatory response. Angiogenesis is a biological process in which new blood vessels grow from existing vascular structures. VEGF, fibroblast growth factor and other factors stimulate angiogenesis [34]. It has been reported that a novel strategy to treat ischemic cardiovascular disease by stimulating angiogenesis may be particularly attractive to patients with diffuse coronary artery disease [35]. Here, we report that E2 effectively reduced oxidative stress response after H/R stimulation. Additionally, E2 promoted angiogenesis compared to the H/R model. Further results indicated that the secretion levels of IL-1, IL6, and TNF-α decreased significantly under the effect of E2. E2 can alleviate the inflammatory response induced by H/R stimulation.

Cyclin-dependent protein kinases (CDK) is a serine/threonine kinase system corresponding to cell cycle progression [36]. Acting synergistically with cyclin, CDK plays a vital role in which CDK is the catalytic subunit and cyclin is the regulatory subunit [37]. Different cyclin-CDK complexes catalyze the phosphorylation of different substrates at different cell cycle phases. E2 promotes the expression of CDK1 and CDK2 in types of cells. Therefore, our results find that E2 upregulated the gene and protein levels of CDK1 and CDK2 inhibited by H/R. We further examined the expression of CDK1 and CDK2 ligand protein Cyclin E1 and Cyclin D1. Results indicate that the protein level of Cyclin E1 and Cyclin D1 greatly increased by the effect of E2 after H/R stimulation. When knocking down CDK1 and CDK2 of CMVECs, E2 did not affect the protein expression of Cyclin E1 and Cyclin D1. At the same time, the effect of estradiol on cell proliferation after H/R injury was significantly weakened. After CDK1 knockdown, the regulatory effect of estradiol on oxidative stress, angiogenesis, and inflammatory response was weakened considerably or even disappeared.

In summary, our results suggest that E2 protects CMVECs from H/R-induced damage by reducing oxidative stress, improving endothelial angiogenesis disorders, and inhibiting inflammation, mediated by activating the CDK1/CDK2 signaling pathway. This study lacks pharmacological studies on E2 in vivo. This will be the direction of subsequent studies in this study. These results suggest that E2 has the potential to be a promising drug for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases.

Statement of ethics

No humans or animals were involved in this research.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contribution

KZ and JX Conceived and designed the experiments. KZ and JX performed the experiments. HW and XL Analyzed and interpreted the data. KZ, BN and JH Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data. KZ, JX and HW Wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

Not Applicable.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e14305.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Virani S.S., et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2020 update: a report from the American heart association. Circulation. 2020;141(9):e139–e596. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aryan L., et al. The role of estrogen receptors in cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21(12) doi: 10.3390/ijms21124314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iorga A., et al. The protective role of estrogen and estrogen receptors in cardiovascular disease and the controversial use of estrogen therapy. Biol. Sex Differ. 2017;8(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s13293-017-0152-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang G., et al. Rapid health transition in China, 1990-2010: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2013;381(9882):1987–2015. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61097-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang W., et al. The pivotal role of mitsugumin 53 in cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2021;21(1):2–11. doi: 10.1007/s12012-020-09609-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ji H., et al. GRP78 effectively protect hypoxia/reperfusion-induced myocardial apoptosis via promotion of the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021;236(2):1228–1236. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao J., et al. Cytomegalovirus beta2.7 RNA transcript protects endothelial cells against apoptosis during ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29(3):342–345. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee Y.S., et al. Sirtuin 1-dependent regulation of high mobility box 1 in hypoxia-reoxygenated brain microvascular endothelial cells: roles in neuronal amyloidogenesis. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(12):1072. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-03293-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bourke L.T., et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies enhance rat neonatal cardiomyocyte apoptosis in an in vitro hypoxia/reoxygenation injury model via p38 MAPK. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(1):e2549. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao X., et al. The suppression of pin1-alleviated oxidative stress through the p38 MAPK pathway in ischemia- and reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/1313847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang S., Yang X. Eleutheroside E decreases oxidative stress and NF-kappaB activation and reprograms the metabolic response against hypoxia-reoxygenation injury in H9c2 cells. Int. Immunopharm. 2020;84 doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ocaranza M.P., et al. Recent insights and therapeutic perspectives of angiotensin-(1-9) in the cardiovascular system. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2014;127(9):549–557. doi: 10.1042/CS20130449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taxier L.R., Gross K.S., Frick K.M. Oestradiol as a neuromodulator of learning and memory. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2020;21(10):535–550. doi: 10.1038/s41583-020-0362-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zimmerman M.A., et al. Medroxyprogesterone opposes estradiol-induced renal damage in midlife ovariectomized Long Evans rats. Menopause. 2020;27(12):1411–1419. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J., et al. 17beta-Estradiol and agonism of G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor enhance hippocampal memory via different cell-signaling mechanisms. J. Neurosci. 2016;36(11):3309–3321. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0257-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adlanmerini M., et al. Mutation of arginine 264 on ERalpha (estrogen receptor alpha) selectively abrogates the rapid signaling of estradiol in the endothelium without altering fertility. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020;40(9):2143–2158. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.314159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simoncini T., et al. Activation of nitric oxide synthesis in human endothelial cells using nomegestrol acetate. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;108(4):969–978. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000233184.64531.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pupo M., Maggiolini M., Musti A.M. GPER mediates non-genomic effects of estrogen. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016;1366:471–488. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3127-9_37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balogh A., et al. Sex hormone-binding globulin provides a novel entry pathway for estradiol and influences subsequent signaling in lymphocytes via membrane receptor. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):4. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36882-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Z., et al. Estrogen receptor alpha mediates the nongenomic activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by estrogen. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;103(3):401–406. doi: 10.1172/JCI5347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H., et al. 17beta-Estradiol alleviates intervertebral disc degeneration by inhibiting NF-kappaB signal pathway. Life Sci. 2021;284 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy A.J., Guyre P.M., Pioli P.A. Estradiol suppresses NF-kappa B activation through coordinated regulation of let-7a and miR-125b in primary human macrophages. J. Immunol. 2010;184(9):5029–5037. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mishra J.S., et al. Estrogen receptor-beta mediates estradiol-induced pregnancy-specific uterine artery endothelial cell angiotensin type-2 receptor expression. Hypertension. 2019;74(4):967–974. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.13429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Z., et al. Association of statin use with disability-free survival and cardiovascular disease among healthy older adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020;76(1):17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Razaz N., et al. Maternal obesity and risk of cardiovascular diseases in offspring: a population-based cohort and sibling-controlled study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(7):572–581. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toniolo M., et al. Unpredictable fall of severe emergent cardiovascular diseases hospital admissions during the COVID-19 pandemic: experience of a single large center in Northern Italy. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020;9(13):e017122. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pourhanifeh M.H., et al. Clinical application of melatonin in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases: current evidence and new insights into the cardioprotective and cardiotherapeutic properties. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2022;36(1):131–155. doi: 10.1007/s10557-020-07052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hawkins Bressler L., et al. Poor endometrial proliferation after clomiphene is associated with altered estrogen action. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021;106(9):2547–2565. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wittnich C., et al. Sex differences in myocardial metabolism and cardiac function: an emerging concept. Pflügers Archiv. 2013;465(5):719–729. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang M., et al. Sex differences in the myocardial inflammatory response to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005;288(2):E321–E326. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00278.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang H., et al. Exosomes from SIRT1-overexpressing ADSCs restore cardiac function by improving angiogenic function of EPCs. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2020;21:737–750. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2020.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu H., et al. Dietary pattern and long-term effects of particulate matter on blood pressure: a large cross-sectional study in Chinese adults. Hypertension. 2021;78(1):184–194. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li W., et al. PLCE1 promotes myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in H/R H9c2 cells and I/R rats by promoting inflammation. Biosci. Rep. 2019;39(7) doi: 10.1042/BSR20181613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y.H., et al. Apelin affects the progression of osteoarthritis by regulating VEGF-dependent angiogenesis and miR-150-5p expression in human synovial fibroblasts. Cells. 2020;9(3) doi: 10.3390/cells9030594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wan X., et al. FOSL2 promotes VEGF-independent angiogenesis by transcriptionnally activating Wnt5a in breast cancer-associated fibroblasts. Theranostics. 2021;11(10):4975–4991. doi: 10.7150/thno.55074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ord M., et al. Cyclin-specific docking mechanisms reveal the complexity of M-CDK function in the cell cycle. Mol. Cell. 2019;75(1):76–89 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loyer P., Trembley J.H. Roles of CDK/Cyclin complexes in transcription and pre-mRNA splicing: cyclins L and CDK11 at the cross-roads of cell cycle and regulation of gene expression. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020;107:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2020.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.