Abstract

Cowden syndrome is a rare autosomal dominant genetic disorder characterized by a germline mutation in the phosphatase and tensin homolog gene, leading to multiple hamartomas, neurodevelopmental disorders, and an increased lifetime risk of multiple cancers. Malignancy is the most common cause of mortality in Cowden syndrome, with breast cancer being the most common malignancy encountered in females with the disorder. Screening guidelines for this population should address this risk at an early age. We present a case of metachronous thyroid cancer followed by synchronous breast cancer and melanoma in a young female with Cowden syndrome, highlighting diagnostic imaging, management, and screening considerations.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Thyroid cancer, Melanoma, Cowden syndrome, PTEN, Screening

Introduction

Phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN)-hamartoma tumor syndrome is a spectrum of autosomal dominant disorders with an underlying mutation in the tumor suppressor gene PTEN on chromosome 10 [1,2]. PTEN-hamartoma syndrome is characterized by the development of multiple hamartomas, neurodevelopmental disorders, and an increased risk of malignancy, with specific major and minor diagnostic criteria adopted by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [3,4]. PTEN-hamartoma tumor syndrome has historically included Cowden syndrome, Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, Proteus syndrome, and Lhermitte-Duclos disease [5,6].

Cowden syndrome is characterized by hamartomas in multiple organs and an increased risk of breast, thyroid, and genitourinary carcinomas. Mucocutaneous lesions include trichilemmomas, acral keratoses, neuromas, and papillomas [1]. It is estimated that females with Cowden syndrome have an up to 85% lifetime risk of developing breast cancer, with a 23% risk of developing breast cancer by the age of 30 [7,8].

There are few case reports describing multiple metachronous and synchronous malignancies in patients with this rare disorder, and fewer presenting the imaging spectrum of the disorder [9], [10], [11]. We present a case of a young female with Cowden syndrome who developed synchronous breast cancer and melanoma following metachronous thyroid cancer, highlighting imaging findings to help guide diagnosis and management.

Case report

A premenopausal adolescent female with a physical exam notable for macrocephaly and multiple cutaneous fibromas (Fig. 1), as well as a neurologic history notable for seizures and autism was referred for genetic testing given the constellation of findings concerning for an underlying genetic disorder. Genetic testing revealed a heterozygous disease-causing frameshift PTEN mutation denoted c.321delT, resulting in a premature stop codon. The patient's mutation and clinical picture confirmed the diagnosis of Cowden syndrome.

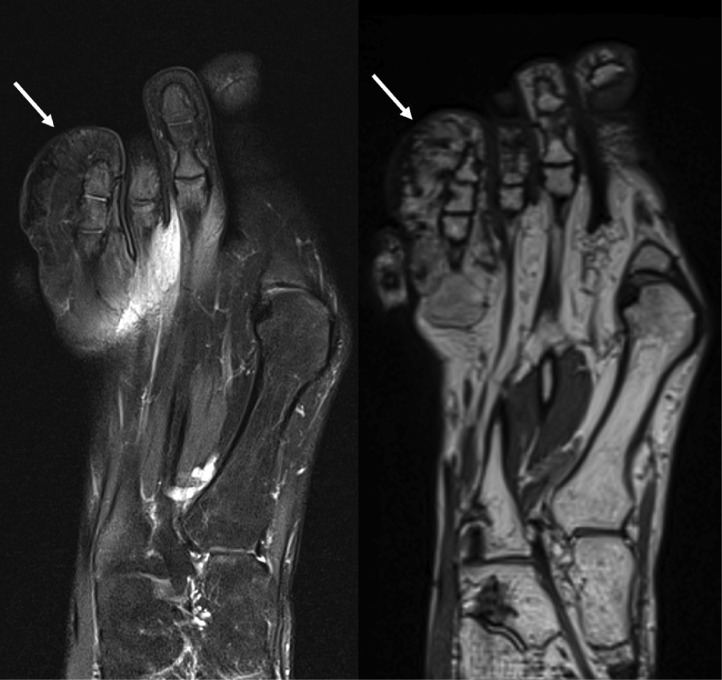

Fig. 1.

Right toe parakeratosis. Right foot noncontrast MRI T2-weighted (left) and proton density (right) images demonstrated a chronically enlarged fourth toe with hypointense signal on all sequences (arrows), suggestive of infantile digital fibromatosis. Skin punch biopsy demonstrated focal parakeratosis and thickened dermal collagen.

Given the patient's diagnosis, annual screening thyroid ultrasound was initiated. At the age of 24, thyroid ultrasound demonstrated a suspicious 0.9 cm right upper pole thyroid nodule (Fig. 2). Fine needle aspiration biopsy confirmed papillary thyroid carcinoma. The patient underwent a right thyroid lobectomy and central neck dissection, with metastatic papillary thyroid cancer found in 4 of 7 lymph nodes.

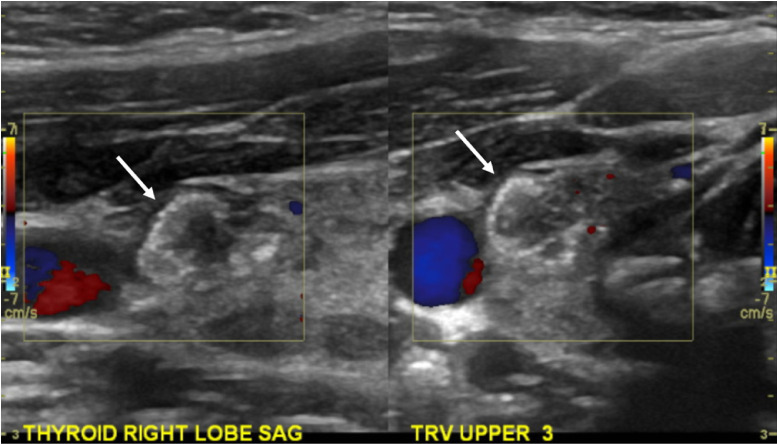

Fig. 2.

Right papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid ultrasound demonstrated a hypoechoic right thyroid nodule (arrows) with minimal vascularity and internal echogenic foci consistent with calcifications. Fine needle aspiration biopsy demonstrated papillary thyroid carcinoma.

At the age of 27, the patient presented with a palpable left breast mass and left nipple inversion. Targeted left breast ultrasound initially performed demonstrated an irregular mass with indistinct margins and hyperechoic foci suggestive of microcalcifications in the left 3:00 breast (Fig. 3). Left axillary ultrasound demonstrated multiple prominent lymph nodes with up to 4 mm cortical thickness. A bilateral mammogram was subsequently performed due to suspicious sonographic findings, demonstrating a 6.8 cm left outer breast global asymmetry with associated fine pleomorphic calcifications, diffuse left breast skin thickening, and left nipple inversion. Multiple coarse calcifications and a retreoareolar breast oval circumscribed mass were also noted in the right breast. The patient underwent ultrasound guided core needle biopsies of the left 3:00 breast mass, left axillary lymph node, and right retroareolar breast mass.

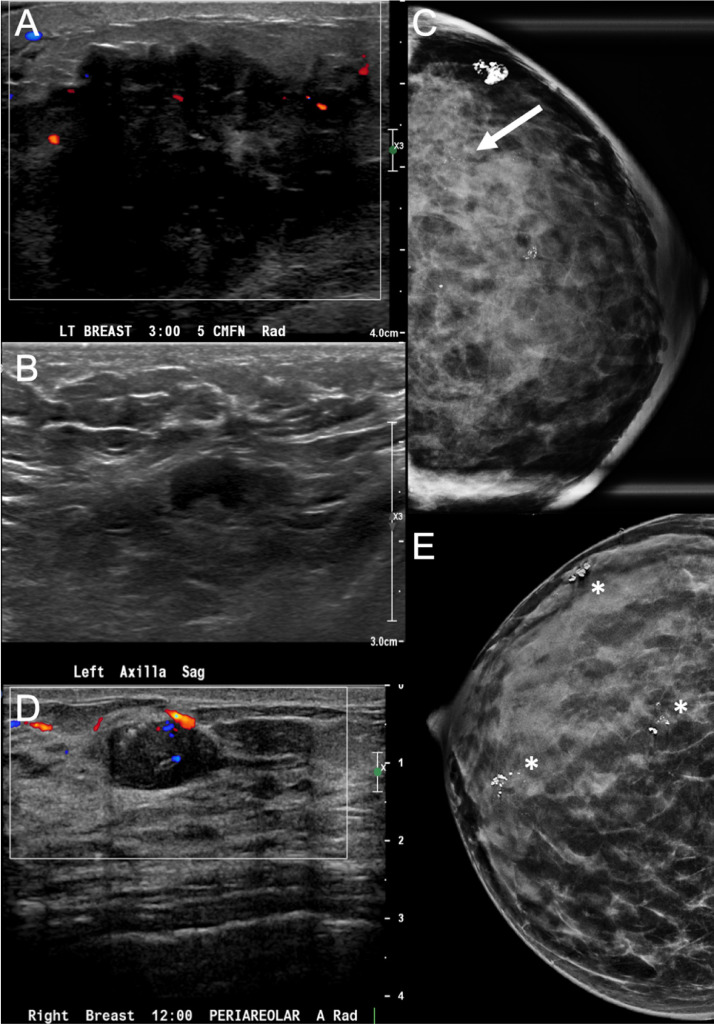

Fig. 3.

Left breast carcinoma and right breast papilloma. Left breast ultrasound demonstrated an irregular hypoechoic palpable mass (A) with associated prominent left axillary lymph nodes (B), subsequently biopsied as IDC with metastatic lymphadenopathy. Left mammogram magnification CC view demonstrated a global asymmetry in the left outer breast (C) with associated fine pleomorphic calcifications (arrow). Right mammogram CC view demonstrated multiple groups of coarse calcifications (asterisks, E), one of which in the right retroareolar region corresponded to an oval hypoechoic mass with internal vascularity on ultrasound (D), subsequently biopsied as a papilloma with ADH. ADH, atypical ductal hyperplasia; IDC, invasive ductal carcinoma.

Biopsy pathology of the left 3:00 breast mass demonstrated grade 3 invasive ductal carcinoma and grade 2 ductal carcinoma in situ with lymphovascular invasion, ER positive and PR/HER2 negative with a high Ki-67 of 35%. The left axillary lymph node demonstrated metastatic carcinoma. The right retroareolar breast biopsy demonstrated an intraductal papilloma with atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH).

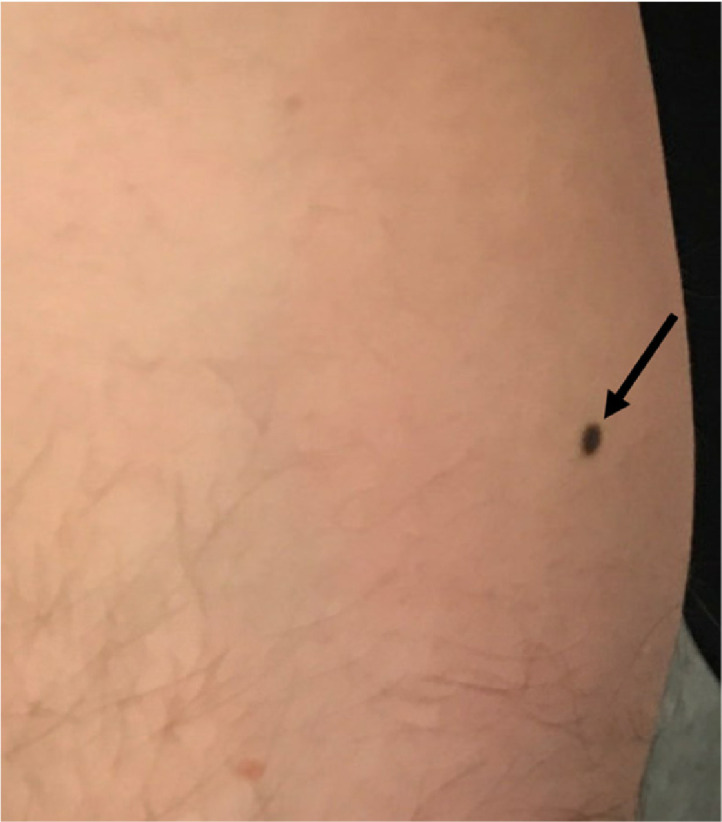

Subsequent PET/CT demonstrated markedly increased FDG uptake in the biopsy proven left breast and left axillary lymph node malignancies, as well as mildly increased FDG uptake in the right breast biopsy proven papilloma with ADH (Fig. 4). Clinically, the patient's left breast cancer was stage III cT3 N1 M0. The patient was treated with neoadjuvant dose-dense doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and paclitaxel chemotherapy for approximately 6 months, with minimal change in tumor burden. During the course of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the patient underwent skin shave biopsy of a newly discovered dark brown macule on the right medial calf noted on physical exam, pathology demonstrating superficial spreading malignant melanoma (Fig. 5).

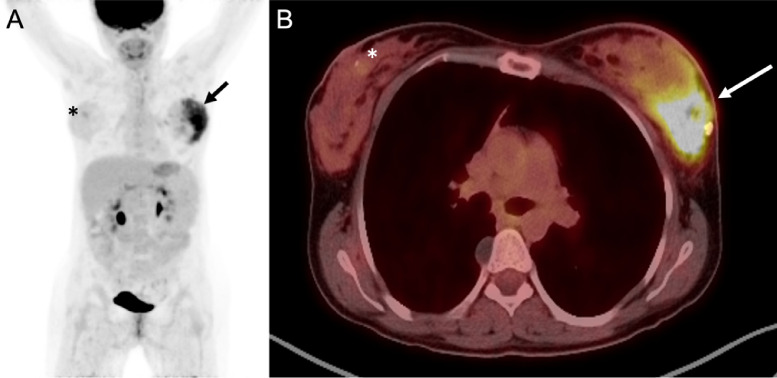

Fig. 4.

PET/CT of left breast carcinoma and right breast papilloma. Whole body maximum intensity projection (A) and fused axial image (B) demonstrated markedly increased FDG uptake in the left outer breast carcinoma (arrows), as well as minimally increased FDG update in the right retroareolar breast papilloma with ADH (asterisks). ADH, atypical ductal hyperplasia.

Fig. 5.

Right calf melanoma. Right medial calf clinical photograph demonstrated a suspicious dark brown macule noted on physical exam. Skin shave biopsy demonstrated superficial spreading malignant melanoma.

At the conclusion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, the patient was treated with a left modified radical mastectomy with sentinel lymph node biopsy, right simple mastectomy, and wide excision of the right calf melanoma. Final left breast surgical pathology demonstrated residual invasive ductal carcinoma with negative margins and 4/5 metastatic left axillary lymph nodes. Final right breast surgical pathology demonstrated the biopsied papilloma with ADH and extensive fibrocystic and fibroadenomatoid changes. Final right calf surgical pathology was negative for residual melanoma.

Following surgical treatment of breast cancer, the patient received adjuvant left chest postmastectomy radiation. The patient was treated with tamoxifen for 5 months, and continued on goserelin, anastrozole, and abemaciclib. The patient was also treated with zoledronic acid for osteoporosis.

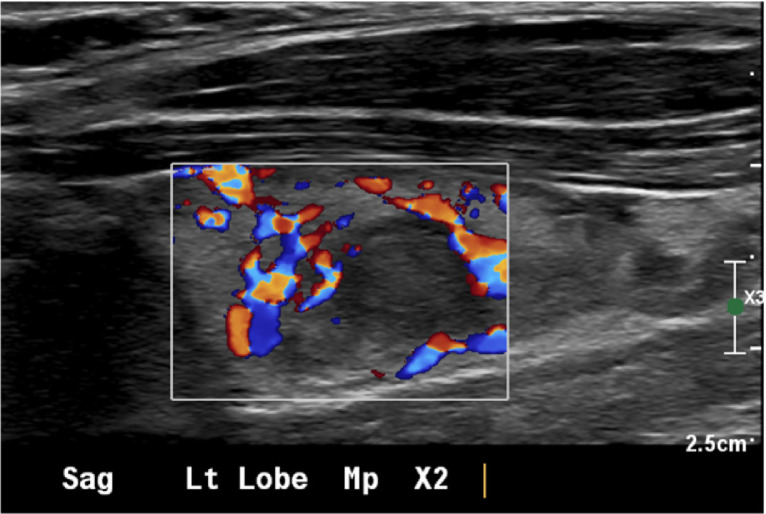

Six months after surgical treatment, the patient was noted to have recurrent papillary thyroid cancer in a 1.1 cm left thyroid nodule (Fig. 6). This was treated with completion thyroidectomy and left central neck dissection. The patient continues to be monitored with neck ultrasounds and thyroid panel laboratory values.

Fig. 6.

Left papillary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid ultrasound demonstrated a hypoechoic left thyroid nodule with peripheral vascularity. Fine needle aspiration biopsy demonstrated papillary thyroid carcinoma.

Discussion

Cowden syndrome is rare, with an estimated incidence of 1 in 200,000 [2]. Individuals with PTEN mutations have a significantly increased cumulative lifetime risk of developing cancer, estimated to be up to 85% by the age of 70 [7]. Breast cancer is the most common malignancy in females with Cowden syndrome, with a lifetime risk estimated to be up to 85%, followed by a 35% increased lifetime risk of thyroid cancer [8]. Melanoma is less common, with a 6% increased risk in this patient population. This case is unique in that the patient not only developed 3 separate malignancies, but the breast cancer and melanoma presented synchronously while the initial and recurrent thyroid cancer presented metachronously.

The most recent NCCN guidelines (version 1.2023) recommends annual mammography and contrast enhanced MRI beginning at age 35 or 10 years before the earliest known familial breast cancer for females with Cowden syndrome, whichever comes sooner [4]. The NCCN also recommends breast awareness at age 18, clinical breast exams every 6-12 months starting at age 25, and the discussion of risk-reducing mastectomy in those with pathogenic/likely pathogenic variant mutations. The American College of Radiology recommends slightly earlier imaging surveillance initiation, with annual screening MRI starting at age 25-30 and annual mammography starting at age 30 for females with a genetics-based increased risk or greater than 20% lifetime risk of breast cancer [12].

Several studies of patients with Cowden syndrome identified breast cancer in females less than 30 years of age [7,8,11,13]. The previously reported up to 85% lifetime risk of breast cancer in females with Cowden syndrome is similar to reported lifetime risks of up to 87% in BRCA1 and 56% in BRCA2 mutation carriers, suggesting that breast cancer screening for those with Cowden syndrome could begin at 25, similar to BRCA mutation carriers [8,14]. If a patient less than 30 presents with an area of palpable concern, the ACR appropriateness criteria recommend targeted ultrasound in the area of clinical concern as the initial exam [15]. However, these criteria note that mammography may also be indicated in the setting of suspicious sonographic findings, as was performed in the presented case.

Females with Cowden syndrome also develop benign breast pathology. One case series demonstrated a nearly 50% prevalence rate of benign breast proliferation, including hemartomas [16]. In this case, surgical pathology from the prophylactic right mastectomy revealed fibrocystic changes, fibroadenomatoid changes, and a papilloma. The presence of many benign breast lesions in patients with Cowden syndrome can make the diagnosis of breast cancer challenging.

Those with Cowden syndrome are also at an increased risk of developing thyroid carcinoma, with a lifetime risk as high as 35% [8]. Although the presented patient had papillary thyroid cancer, both follicular and papillary variants of thyroid cancer have been associated with syndrome [1,17]. Current NCCN guidelines recommend annual screening thyroid ultrasound starting as early as age 7, or at the time of diagnosis [4]. The NCCN also recommends that those with Cowden syndrome undergo annual skin exams given the risk of melanoma as seen in this case, colonoscopies starting at age 35 and every 5 years thereafter given the risk of colorectal carcinoma, possible endometrial biopsies every 1-2 years starting at age 35 given the risk of endometrial carcinoma, and renal ultrasounds every 1-2 years starting at age 40 given the risk of renal cell carcinoma [4].

Conclusion

Although Cowden syndrome and PTHS are rare, the increased risk of multiple malignancies necessitates careful surveillance of this patient population to ensure timely diagnosis and management. This case highlights the imaging spectrum of malignancies seen in Cowden syndrome and the need for appropriate screening guidelines, in particular for young females that are at highest risk of developing breast cancer. Screening interventions provide significant benefit to patients with Cowden syndrome, allowing for early detection, prompt treatment, and improved outcomes.

Patient consent

The authors certify that written, informed consent for publication of this case report was obtained from the patient.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have no disclosures of possible conflict of interest or commercial involvement. The Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board approved this study.

References

- 1.Pilarski R. PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: A clinical overview. Cancers. 2019;11(6):844. doi: 10.3390/cancers11060844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelen M.R., Kremer H., Konings I.B., Schoute F., van Essen A.J., Koch R., et al. Novel PTEN mutations in patients with cowden disease: Absence of clear genotype-phenotype correlations. Eur J Hum Genet. 1999;7(3):267–273. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pilarski R., Burt R., Kohlman W., Pho L., Shannon K.M., Swisher E. Cowden syndrome and the PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: Systematic review and revised diagnostic criteria. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105(21):1607–1616. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic (version 1.2023). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_bop.pdf. [Accessed 10.01.23].

- 5.Blumenthal G.M., Dennis P.A. PTEN hamartoma tumor syndromes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16(11):1289–1300. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hobert J.A., Eng C. PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: An overview. Genet Med. 2009;11(10):687–694. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181ac9aea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bubien V., Bonnet F., Brouste V., Hoppe S., Barouk-Simonet E., David A., et al. High cumulative risks of cancer in patients with PTEN hamartoma tumour syndrome. J Med Genet. 2013;50(4):255–263. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-101339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tan M.H., Mester J.L., Ngeow J., Rybicki L.A., Orloff M.S., Eng C. Lifetime cancer risks in individuals with germline PTEN mutations. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(2):400–407. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melbārde-Gorkuša I., Irmejs A., Bērziņa D., Strumfa I., Aboliņš A., Gardovskis A., et al. Challenges in the management of a patient with cowden syndrome: Case report and literature review. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2012;10(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1897-4287-10-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pradella L.M., Evangelisti C., Ligorio C., Ceccarelli C., Neri I., Zuntini R., et al. A novel deleterious PTEN mutation in a patient with early-onset bilateral breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Won H.S., Chang E.D., Na S.J., Whang I.Y., Lee D.S., You S.H., et al. PTEN mutation identified in patient diagnosed with simultaneous multiple cancers. Cancer Res Treat. 2019;51(1):402–407. doi: 10.4143/crt.2017.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monticciolo D.L., Newell M.S., Moy L., Niell B., Monsees B., Sickles E.A. Breast cancer screening in women at higher-than-average risk: Recommendations from the ACR. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15(3 Pt A):408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riegert-Johnson D.L., Gleeson F.C., Roberts M., Tholen K., Youngborg L., Bullock M., et al. Cancer and lhermitte-duclos disease are common in cowden syndrome patients. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2010;8(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1897-4287-8-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elezaby M., Lees B., Maturen K.E., Barroilhet L., Wisinski K.B., Schrager S., et al. BRCA mutation carriers: Breast and ovarian cancer screening guidelines and imaging considerations. Radiology. 2019;291(3):554–569. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019181814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein K, Kocher M, Lourenco A, Niell B, Bennett D, Chetlen A, et al. American College of Radiology ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Palpable Breast Masses. https://acsearch.acr.org/docs/69495/Narrative. [Accessed 01.10.2022].

- 16.Schrager C.A., Schneider D., Gruener A.C., Tsou H.C., Peacocke M. Clinical and pathological features of breast disease in cowden's syndrome: an underrecognized syndrome with an increased risk of breast cancer. Hum Pathol. 1998;29(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(98)90389-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Szabo Yamashita T., Baky F.J., McKenzie T.J., Thompson G.B., Farley D.R., Lyden M.L., et al. Occurrence and natural history of thyroid cancer in patients with cowden syndrome. Eur Thyroid J. 2020;9(5):243–246. doi: 10.1159/000506422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]