Background

Peri-implantitis additional treatment generally aims to repair damaged tissue through a regenerative approach. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (hUCMSCs) produce a high osteogenic effect and are capable of modulating the immune system by suppressing inflammatory response, modulating bone resorption, and inducing endogenous osteogenesis. Aim: This study was intended to discover the effect of hUCMSCs on an implant osseointegration process in peri-implantitis rat subjects as assessed by several markers including interleukin-10 (IL-10), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa- β ligand (RANKL), bone morphogenic protein (BMP-2), osterix (Osx), and osteoprotegerin (OPG). Material and methods: The research design implemented during this study represented a true experimental design incorporating the use of Rattus norvegicus (Wistar strain) as subjects. Results: Data analysed by means of a Brown Forsythe test indicated differences between the increase in BMP-2 expression (p < 0.000) and Osx expression (p < 0.001) and between RANKL expression (p < 0.001, Tukey HSD) and OPG expression (p < 0.000, Games Howell). Conclusion: According to the findings of this research, hUCMSCs induction is successful in accelerating and enhancing osteogenic activity and implant osseointegration in peri-implantitis rat subjects.

Keywords: Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells, Implant, Osseointegration, Peri-implantitis, Medicine

1. Introduction

The success of implant placement is evidenced by the occurrence of osseointegration between the implant and the alveolar bone (Misawa et al., 2016). Nevertheless, persistent bacterial contamination on the implant surface will lead to the formation of a pathogenic biofilm and, in turn, to peri-implantitis (Alghamdi, 2018, Amengual-Peñafiel et al., 2021) which constitutes a major factor in implant failure (Kate et al., 2016, Pirih et al., 2015). In general, its treatment aims to remove the biofilm adhering to the implant surface by means of systemic antibiotic application, mechanical debridement, decontamination using an Er:YAG laser, and combinations of these various forms of treatment. However, none of the primary care strategies has been shown to be particularly potent against peri-implantitis (Novaes et al., 2019, Schminke et al., 2015). In contrast to primary peri-implantitis treatments, secondary forms focus on repairing damaged tissue through a regenerative approach involving the use of growth factors (Amengual-Peñafiel et al., 2021, Novaes et al., 2019). Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells (hUCMSCs) isolated from the umbilical cord are multipotential, have a high osteogenic effect, and are capable of increasing osteogenic activity in rats suffering from osteoporosis (Hendrijantini et al., 2019, Hendrijantini et al., 2018, Marmotti et al., 2017). Induction of hUCMSCs may prove capable of modulating the immune system by suppressing inflammatory response, modulating bone resorption mediated by osteoclasts, and inducing endogenous osteogenesis (Amengual-Peñafiel et al., 2021). However, research using exogenous hUCMSCs induction to treat peri-implantitis has not previously been carried out. In order to determine the nature of the osseointegrative process, several markers can be assessed, including anti-inflammatory and osteogenesis varieties. The purpose of this study was to analyze the effect of hUCMSCs induction on TGF-β, IL-10, BMP-2, OSX, RANKL, and of OPG on the acceleration of osseointegration related to implants in peri-implantitis rat subjects.

2. Material and methods

Ethical Approval

The human umbilical cord used in this study was acquired from cases of Caesarean delivery. Potential donors signed an informed consent document, a course of action approved by the Medical Committee of the local general hospital. The research which entailed the minimal use of animal subjects was approved by the Animal Research Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine (010/HRECC.FODM/I/2022). Studies involving the use of animal subjects had previously been performed at the Institute of Tropical Disease of Universitas Airlangga.

2.1. Study design

The research design used in this study represented a true experimental, randomized, post-test only control group design.

2.2. hUCMSCs preparation

Isolation and culture of hUCMSCs up to passage 6 with 500.000 cells being subsequently injected into the implant site. Flowcytometry performed during passage 4 confirmed the presence of mesenchymal stem cells with positive CD 73, CD 90, CD 105, and negative CD 45.

2.3. Laboratory animal preparation

This research was carried out using healthy, 8–10-week- old, male Rattus norvegicus strain rats, weighing 150–200 g, in accordance with prevailing experimental animal production criteria. Each subject undergoing peri-implantitis was injected in the implant socket by means of a Hamilton syringe prior to implant placement being implemented with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) derived from Porphyromonas gingivalis bacteria 0.01 ml at a dose of 1 μg/0.01 ml of PBS. A period of four weeks was then allowed to elapse to enable peri-implantitis to occur.

2.4. Number of samples and sample groups

The total number of samples was 28, and the LPS injection samples were randomly divided into four groups: C1, C2, T1, and T2. C1 constituted the implant group whose members were terminated after two weeks, C2 was the implant group whose members were terminated after four weeks, T1 was the implant with hUCMSCs induction group whose members were terminated after two weeks, while T2 was the implant with hUCMSCs induction group whose members were terminated after four weeks. This experiment involved the use of a 1x2mm pure titanium implant with a specific drilling bur utilised for animal subjects. The implant placement was performed 7 mm from the distal edge of the femur bone. hUCMSCs were injected with a 27G syringe at a distance of 1 mm from the mesial and distal of the implant site.

2.5. Variables and data collection

Histologic examination was undertaken by the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Universitas Airlangga. Immunohistochemical examination was performed to establish the presence of TGF-β, IL-10, BMP-2, OSX, RANKL, and OPG. The cells observed for TGF-β and IL-10 expressions were osteoblasts found on the marginal areas of the implant site. The data was obtained in accordance with a modified Remmele scale index of Immunoreactive score (IRS) (Nowak et al., 2007). The results represented the cell percentage/positive immunoreactive area scores multiplied by the colour intensity immunoreactive scores (see Table 1).

Table 1.

The modified Remmele scale index of Immunoreactive Score (IRS) (Nowak et al., 2007)

| Score | % Positive cells | Colour intensity score |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | none | No colour reaction |

| 1 | <10 % | Low intensity colour |

| 2 | Between 11, 50 % | Moderate intensity colour |

| 3 | Between 50 and 80 % | High intensity colour |

| 4 | More than 80 % |

The sample data consisted of the average value from five fields of view at 400x magnification using a regular light microscope (Nikon H600L) equipped with a DS Fi2 digital (300 megapixel) camera and image processing software (Nikon Image System).

2.6. Statistical analysis

The data was assessed for its normality and homogeneity by means of a Shapiro Wilk and Levene test. Further analysis of the heterogeny group was performed with a Brown Forsythe and Games-Howell test, while the homogenous group was analyzed using one-way ANOVA and post-hoc Tukey HSD tests. All analysis was completed at a 0.05 significance level.

3. Results

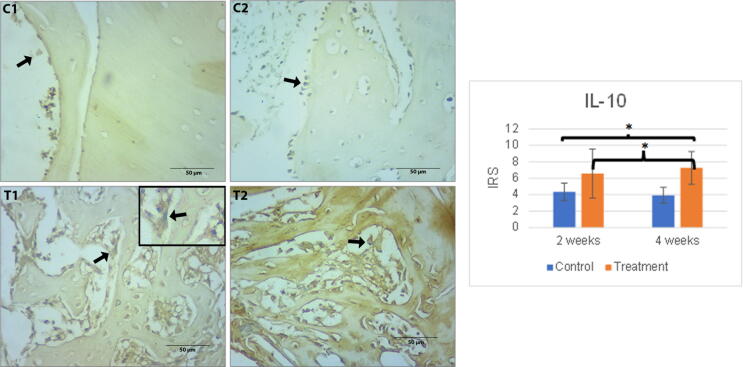

3.1. Il-10

The number of IL-10 expressions in the control group tended to decrease, while that in the treatment group experienced an increasing trend. No difference in the number of expressions was found between groups C1 and C2, or T1 and T2. A statistically significant difference was spotted between C1 and T2, C2 and T2 (p < 0.05). The result of immunohistochemical staining of each group for TGF- β and IL-10 inflammatory markers can be viewed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Left: The immunohistochemical staining of IL-10 expression in all peri-implantitis groups contained in osteoblast cells around the implant site. The black arrow indicates osteoblast cells with an overexpression of IL-10. Scale bar = 50 µm. Each box is presented at 1000x magnification. C1 (implant 2 weeks), C2 (implant 4 weeks), T1 (implant + hUCMSCs 2 weeks), T2 (implant + hUCMSCs 4 weeks). Right: Mean of IRS of IL-10 expressions together with its standard deviation. Single asterisk (*) above the bars represents p value < 0.05, double asterisk (**) represents p value < 0.01, and triple asterisk (***) represents p value < 0.001.

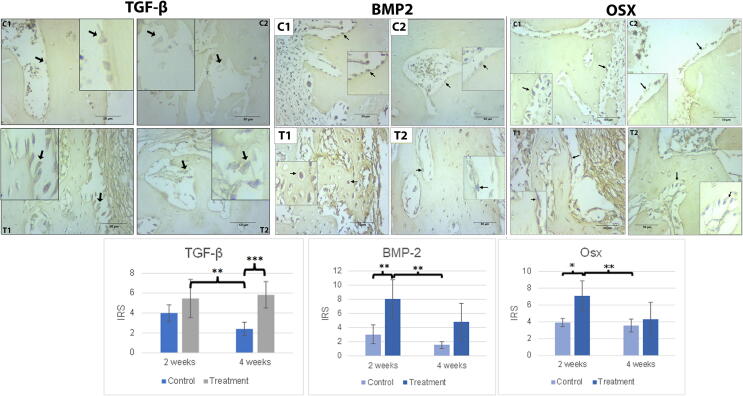

3.2. TGF-β, BMP-2 and Osx

The C2 group experienced the lowest TGF-β expressions compared to any other group, while the T2 group showed the highest. An increased trend in TGF-β expression was observed in both the control and treatment groups, whereas that in the control group decreased. The C2 and T2 groups differed significantly with p values < 0.001. In contrast, no difference was found between either the C1 and C2, or the T1 and T2 groups (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

(A) The immunohistochemical staining of BMP-2 A in all peri-implantitis groups in the osteoblast cells around the implant site. (B). The immunohistochemical staining of Osx expression in all peri-implantitis groups in osteoblast cells around the implant site. The black arrow indicates the osteoblast cells with an overexpression of BMP-2 and Osx. Scale bar = 50 µm. Each box represented positive cells at 1000x magnification. C1 (implant 2 weeks), C2 (implant 4 weeks), T1 (implant + hUCMSCs 2 weeks), T2 (implant + hUCMSCs 4 weeks). (C) Mean of IRS of BMP-2 and Osx expressions together with its standard deviation. The single asterisk (*) above the bars represents p value < 0.05, double asterisk (**) represents p value < 0.01, and triple asterisk (***) represents p value < 0.001.

Treatment group (T1) had the highest expressions of BMP-2, followed by the T2 group. The lowest expressions of BMP-2 were observed in the control groups (C2, C1). While a statistically significant difference was observed between T2 and C1 (p < 0.01), and T2 and C2 (p < 0.01), none was found to exist between the T1 and T2 groups (Fig. 2).

For Osx expressions, the pattern of IRS scores was similar to that for BMP-2 expressions. The T1 group produced the highest expressions, followed by T2, C1, and C2. There was still no significant difference between groups T1 and T2. C1 and T1 differed significantly with p value 0.011 (p < 0.05), while the p value of C2 and T1 was 0.005 (p < 0.01). Both BMP-2 and Osx expressions showed a decline over time (Fig. 2).

The increase in Osx expression over a 2-week period indicated that osteoblast maturation had occurred. This is supported by the microscopic evidence that T2 lamellar bone had been formed in the trabeculae with the immersion of osteocyte cells in the mineralized matrix (Fig. 2).

3.3. RANKL and OPG

Both the control and treatment groups experienced a reduced expression of RANKL and OPG. A similar pattern was seen in both expressions, with the T1 group recording the highest expression, followed by the T2, C1, and C2 groups. The lowest expression occurred in the C2 group. With regard to RANKL expressions, a statistically significant difference was observed between T1 and C1 (p < 0.05), T1 and C2 (p < 0.01), and T1 and T2 (p < 0.05). In the case of OPG expressions, there was a statistically significant difference between C1 and C2, C2 and T1, and C2 and T2 (p < 0.05). In contrast, for T1 and T2 groups no difference existed (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

(A) The immunohistochemical staining of RANKL expression of all peri-implantitis groups in the osteoblast cells around the implant site. (B). The immunohistochemical staining of OPG expression in all peri-implantitis groups in osteoblast cells around the implant site. The black arrow indicates the osteoblast cells with an overexpression of RANKL and OPG. Scale bar = 50 µm. Each box represents cells at 1000x magnification. C1 (implant 2 weeks), C2 (implant 4 weeks), T1 (implant + hUCMSCs 2 weeks), T2 (implant + hUCMSCs 4 weeks). (C) Mean of IRS of RANKL and OPG expressions together with its standard deviation. Single asterisk (*) above bars represents p value < 0.05, double asterisk (**) represents p value < 0.01, and triple asterisk (***) represents p value < 0.001.

4. Discussion

In this study, both anti-inflammatory and osteogenesis markers were used to determine post-hUCMSCS induction osteoblastogenic activity in the peri-implantitis model.

IL-10 is a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine that can limit the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, TNF-, and IFN-γ. It is also considered to be one of the cytokine markers for peri-implantitis. In the course of this study, IL-10 expressions in 4-week treatment group were significantly greater than those of any control group. This result is similar to that of a study by Li et al. (2016) positing that administration of hUCMSC-derived exosome significantly increases IL-10 expression in rats 24 h after severe burn injury. They also proved hUCMSC-exosome to be capable of managing the inflammatory response after LPS induction with increasing levels of IL-10 and suppressed macrophage inflammation (Li et al., 2016). A similar previous study by Ling et al. (2022) also proved that mice having received an experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and hUCMSC injection were still able to increase IL-10 and IL-17 expressions after 14 days (Ling et al., 2022).

The TGF-β role in osteogenesis is widely known. It inhibits the formation of osteoclasts which mobilize TGF-β after the loss of bone matrix and recruit MSCs in areas of bone resorption, thereby enabling the process of osteoblast differentiation. In this study, hUCMSCs groups were able to increase TGF-β expressions. A statistically significant difference of p < 0.000 was found between the 4-week control and treatment groups. The number of TGF-β expressions of control group tended to decrease over time, but that in the treatment group experienced an increase. IL-10 as an anti-inflammatory marker experienced increased expressions over time, there was a significant difference between the treatment administered from two weeks onwards and from four weeks onwards. This proved hUCMSCs capable of maintaining the inflammation at low levels while stimulating proliferation, chemotaxis, and early differentiation of the osteoprogenitor. A study by Zhou (2011) suggests that TGF-β manages osteogenesis via Wnt/β-catenin signaling in hMSCs (Zhou, 2011). On the other hand, TGF-β also negatively regulates differentiation of osteoblasts and mineralization in the latter stages. Further studies of TGF-β dose and period of administration in relation to the treatment of ostheoarthritis are required (Wu et al., 2016).

Bone morphogenic protein (BMP) is a group of proteins that contribute to bone regeneration through the initiation of osteoblastogenesis by progenitor cells (Fernandes and Gomes, 2016). One of the BMP subsets that can induce bone formation is BMP-2 (Sheikh et al., 2015) which is inactive under conditions of homeostasis. If a defect is found in bone, BMP-2 will be activated for bone remodeling by initiating the process of osteoblastogenesis in the quiescent / silent period following bone resorption by osteoclasts24. Data analysis indicated that the highest BMP-2 expression was found in the T1 group. This finding is in accordance with the research of Park et al. conducted in 2019 which showed that the amount of BMP-2 after stem cell induction rose for seven days and then fell up to the twenty-first day (Park et al., 2019). Hendrijantini et al. (2021) also revealed that an increase in BMP-2 expression indicates BMP-2 activity initiating the differentiation of MSCs into osteoprogenitor cells (Hendrijantini et al., 2021). The decrease in BMP-2 expression between 2 weeks and 4 weeks exemplified that osteoblast differentiation has reached the final stage so BMP-2 expression which plays a role in early differentiation will decrease. As seen in the comparison of microscopic appearance between T1 and T2, at T1 the bone trabeculae were still composed of woven bone and there were still many active osteoblasts that would synthesize osteoid. Meanwhile at T2, the osteocyte cells that are in the lacuna have been immersed in the bone matrix and the bone trabeculae are also composed of lamellar tissue, known as lamellar bone trabeculae. Higher value in BMP-2 expression indicates an increase in osteoblastogenesis and osteogenesis activity. This is also supported by the microscopic appearance of the ossification area seen in the T1 group contrasted to the C1 group, as the ossification area in C1 is still in the form of thin bone lines, while in T1 the bone formation looks massive.

These results were in line with the Osx expression level. A significant increase in Osx expression indicated that a differentiation of pre-osteoblasts into mature osteoblasts had occurred. High Osx expression in T1 may be due to an increase in BMP-2 expression which acts as a mediator for Osx regulation induction. Furthermore, during the period from 2 to 4 weeks, a reduction in Osx expression occurred due to osteoblast differentiation having reached its final stage. Consequently, as shown in Fig. 2(B), Osx regulation decreased, as T2 group lamellar bone formed in bone trabeculae with the immersion of osteocyte cells in the mineralized matrix. The reduction in Osx expression between the T1 and T2 groups also indicated that Osx did not experience overexpression since this would have proved noxious. Its potential effect is that of damaging bone through the activation by IL-8 of the osteoclastogenic pathway and parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) (Liu et al., 2020).

There was a statistically significant increase in RANKL between the 2-week control group and the 2-week treatment group (p = 0.013). Contrastingly, there was no difference in RANKL expression between the 4-week control group and the 4-week hUCMSCs treatment (p 0.133). The increase in RANKL recorded for the treatment group could also be due to an increase in osteoblasts as precursors of RANKL (Atkins et al., 2003). MSCs can play a role in increasing osteoblasts (Neve et al., 2011, Sheikh et al., 2015). Moreover, peri-implantitis, an inflammatory process resulting from infection, was identified in the mouse subject. RANKL can also act as an inflammatory mediator by escalating the survival rate of dendritic cells and regulating the spleen node (Leibbrandt and Penninger, 2010). In several recent research findings, the function of osteoclasts has also been shown to be that of an immune regulator whenever the body experiences infectious or pathological conditions. The ability of osteoclasts is not restricted to bone resorption but includes that of acting as an inflammatory agent through an antigen presenting cell (APC) mechanism, accelerating the process of bacterial phagocytosis, and accelerating the activation of T cells (Madel et al., 2019).

Osteoprotegerin (OPG) is a receptor that functions as negative feedback on the process of osteoclastogenesis (Higgs et al., 2017). The binding process of OPG with RANKL prevents RANKL binding to RANK in the preosteoclast membrane. Research on multiple myeloma cases has proved that MSCs significantly increases OPG expression (Higgs et al., 2017). This is consistent with the results of the data analysis completed as part of this study which confirmed a significant increase in OPG in the treatment of hUCMSCs for four weeks compared to four weeks of control (p < 0.038). There was also a statistically significant increase in OPG during the treatment of hUCMSCs for two weeks juxtaposed to the control group for two weeks (p < 0.018). There was a statistically significant decrease in the 4-week control group compared to its 2-week counterpart (p < 0.013) while there was no change between the 2-week and 4-week treatment groups (p < 1.000). This proves that hUCMSCs succeeded in increasing OPG expression and maintaining OPG expression for four weeks post-administration of hUCMSCs in peri-implantitis cases.

5. Conclusion

In vivo induction of hUCMSCs in the peri-implant area has proved successful in accelerating and enhancing osteogenesis activity and implant osseointegration in peri-implantitis rat subjects. This was assessed by the significant increase in TGF-β, IL-10, BMP-2, Osx, and OPG expression.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Nike Hendrijantini: Conceptualization, Validation, Visualization, Supervision. Mefina Kuntjoro: Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Supervision. Bambang Agustono: Conceptualization, Validation, Visualization, Supervision. Ratri Maya Sitalaksmi: Conceptualization, Validation, Visualization, Supervision. Muhammad Dimas Aditya Ari: Conceptualization, Validation, Visualization, Supervision. Marcella Theodora: Software, Formal analysis, Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Rudy Effendi: Software, Formal analysis, Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Ivan Setiawan Djuarsa: Software, Formal analysis, Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Jennifer Widjaja: Data curation, Visualization. Agung Sosiawan: Validation, Investigation, Supervision. Guang Hong: Validation, Investigation, Supervision.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University. Production and hosting by Elsevier.

References

- Alghamdi H.S. Methods to improve osseointegration of dental implants in low quality (Type-IV) bone: an overview. J. Funct. Biomater. 2018;9 doi: 10.3390/JFB9010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amengual-Peñafiel L., Córdova L.A., Constanza Jara-Sepúlveda M., Brañes-Aroca M., Marchesani-Carrasco F., Cartes-Velásquez R. Osteoimmunology drives dental implant osseointegration: a new paradigm for implant dentistry. Jpn Dent. Sci. Rev. 2021;57:12. doi: 10.1016/J.JDSR.2021.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins G.J., Kostakis P., Pan B., Farrugia A., Gronthos S., Evdokiou A., Harrison K., Findlay D.M., Zannettino A.C.W. RANKL expression is related to the differentiation state of human osteoblasts. J. Bone Mineral Res. 2003;18:1088–1098. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.2003.18.6.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes M.H., de Gomes P. Bone cells dynamics during Peri-Implantitis: a theoretical analysis. J Oral Maxillofac Res. 2016;7 doi: 10.5037/JOMR.2016.7306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrijantini N., Kusumaningsih T., Rostiny R., Mulawardhana P., Danudiningrat C.P., Rantam F.A. A potential therapy of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells for bone regeneration on osteoporotic mandibular bone. Eur. J. Dent. 2018;12:358–362. doi: 10.4103/EJD.EJD_342_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrijantini N., Rostiny R., Kurdi A., Ari M.D.A., Sitalaksmi R.M., Hapsari P.D., Arief V., Sati P.Y.I. Molecular triad RANK/ RANKL/OPG in mandible and femur of wistar rats (Rattus norvegicus) With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Recent Adv. Biol. Medicine. 2019;5:1. doi: 10.18639/RABM.2019.959614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrijantini N., Hartono C.K., Daniati R.P., Hong G., Sitalaksmi R.M., Kuntjoro M., Ari M.D.A. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-induced osterix, bone morphogenetic Protein-2, and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase expression in osteoporotic mandibular bone. Eur. J. Dent. 2021;15:84–89. doi: 10.1055/S-0040-1715987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs J.T., Lee J.H., Wang H., Ramani V.C., Chanda D., Hardy C.Y., Sanderson R.D., Ponnazhagan S. Mesenchymal stem cells expressing osteoprotegerin variants inhibit osteolysis in a murine model of multiple myeloma. BloodAdv. 2017;1:2375–2385. doi: 10.1182/BLOODADVANCES.2017007310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kate M.A., Palaskar S., Kapoor P. Implant failure: a dentist’s nightmare. J. Dental Implants. 2016;6:51. doi: 10.4103/0974-6781.202154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leibbrandt A., Penninger J.M. Novel functions of RANK(L) signaling in the immune system. Adv. Experimental Med. Biol. 2010;658:77–94. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1050-9_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Liu L., Yang J., Yu Y., Chai J., Wang L., Ma L., Yin H. Exosome derived from human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell mediates MiR-181c attenuating burn-induced excessive inflammation. EBioMedicine. 2016;8:72–82. doi: 10.1016/J.EBIOM.2016.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling X., Wang T., Han C., Wang P., Liu X., Zheng C., Bi J., Zhou X. IFN-γ-Primed hUCMSCs Significantly Reduced Inflammation via the Foxp3/ROR-γt/STAT3 Signaling Pathway in an Animal Model of Multiple Sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/FIMMU.2022.835345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Fang J., Zhang Q., Zhang X., Cao Y., Chen W., Shao Z., Yang S., Wu D., Hung M., Zhang Y., Tong W., Tian H. Wnt10b-overexpressing umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells promote critical size rat calvarial defect healing by enhanced osteogenesis and VEGF-mediated angiogenesis. J. Orthop. Translat. 2020;23:29. doi: 10.1016/J.JOT.2020.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madel M.B., Ibáñez L., Wakkach A., de Vries T.J., Teti A., Apparailly F., Blin-Wakkach C. Immune function and diversity of osteoclasts in normal and pathological conditions. Front. Immunol. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/FIMMU.2019.01408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmotti A., Mattia S., Castoldi F., Barbero A., Mangiavini L., Bonasia D.E., Bruzzone M., Dettoni F., Scurati R., Peretti G.M. Allogeneic umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells as a potential source for cartilage and bone regeneration: an in vitro study. Stem CellsInt. 2017;2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/1732094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misawa M.Y.O., Huynh-Ba G., Villar G.M., Villar C.C. Efficacy of stem cells on the healing of peri-implant defects: systematic review of preclinical studies. Clin. Exp Dent Res. 2016;2:18–34. doi: 10.1002/CRE2.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neve A., Corrado A., Cantatore F.P. Osteoblast physiology in normal and pathological conditions. Cell Tissue Res. 2011;343:289–302. doi: 10.1007/S00441-010-1086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novaes A.B., Ramos U.D., Rabelo M.D.S., Figueredo G.B. New strategies and developments for peri-implant disease. Braz Oral Res. 2019;33 doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2019.VOL33.0071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak M., Madej J.A., Dziegiel P. Intensity of COX2 expression in cells of soft tissue fibrosacrcomas in dogs as related to grade of tumour malignancy. Bull.-Veterinary Institute in Pulawy. 2007;51:275–279. [Google Scholar]

- Park S.Y., Kim K.H., Kim S., Lee Y.M., Seol Y.J. BMP-2 Gene delivery-based bone regeneration in dentistry. Pharmaceutics. 2019;(11):393. doi: 10.3390/PHARMACEUTICS11080393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirih F.Q., Hiyari S., Leung H.Y., Barroso A.D.V., Jorge A.C.A., Perussolo J., Atti E., Lin Y.L., Tetradis S., Camargo P.M. A Murine Model of Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Peri-Implant Mucositis and Peri-Implantitis. J. Oral Implantol. 2015;41:e158–e164. doi: 10.1563/AAID-JOI-D-14-00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schminke B., vom Orde F., Gruber R., Schliephake H., Bürgers R., Miosge N. The Pathology of Bone Tissue during Peri-Implantitis. J. Dent. Res. 2015;94:354. doi: 10.1177/0022034514559128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh Z., Javaid M.A., Hamdan N., Hashmi R. Bone regeneration using bone morphogenetic proteins and various biomaterial carriers. Materials (Basel) 2015;8:1778–1816. doi: 10.3390/MA8041778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M., Chen G., Li Y.P. TGF-β and BMP signaling in osteoblast, skeletal development, and bone formation, homeostasis and disease. Bone Res. 2016;4 doi: 10.1038/BONERES.2016.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S. TGF-β regulates β-catenin signaling and osteoblast differentiation in human mesenchymal stem cells. J. Cell Biochem. 2011;112:1651–1660. doi: 10.1002/JCB.23079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]