Highlights

-

•

Lactobacillus (LAB) from poultry probiotic products harbored one or more ARGs.

-

•

Co-culture caused transmission of qnrS, CTX-M-1, and tetA genes from LAB to E. coli.

-

•

There is a potential risk of spread of AMR through LAB among poultry population.

Keywords: Probiotics, Lactobacillus, Antimicrobial resistance gene, Horizontal transfer, Poultry

Abstract

The study was conducted to identify the antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) in Lactobacillus spp. from poultry probiotic products and their potential to spread among Escherichia coli. Lactobacillus spp. were isolated and identified from 35 poultry probiotic samples based on the cultural, biochemical, and molecular findings. All the isolates (n = 35) were screened for the presence of some ARGs such as β-lactamases encoding genes (blaTEM, blaCTXM-1, and blaCTXM-2), plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance gene (qnrA, qnrB, and qnrS), and tetracycline resistance genes (tetA and tetB). Five Lactobacillus spp. isolates from three brands were positive for one or more ARGs. The qnrS was detected in four isolates. The blaTEM and tetB were detected in two isolates. One isolate contained blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2, and tetA genes. Brand-wise analysis revealed that one isolate from Brand 4 contained blaTEM, blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2, qnrS, and tetA genes, one isolate from Brand 2 contained blaTEM gene, and three isolates from Brand 7 harbored qnrS gene. The co-culture of Lactobacillus spp. and E. coli resulted in the transmission of qnrS, CTX-M-1, and tetA from Lactobacillus spp. to E. coli. Results of antimicrobial susceptibility test revealed that the highest resistance was observed to cefepime and cefotaxime followed by penicillin G, oxacillin, cefuroxime, and ofloxacin. The findings of the present study indicate the potential risk of horizontal spread of antimicrobial resistance through probiotic bacteria among the poultry population. Therefore, it is very necessary to check for ARGs along with other attributes of probiotic bacteria to avoid the inclusion of resistant strains in probiotics.

1. Introduction

Antibiotic resistance (AMR) is a One Health issue affecting not only people, but animals, plants, and the environment, and it is now recognized as one of the biggest threats to global health, food security, and development (CDC, 2022; WHO, 2020). Of many factors responsible for the emergence and spread of AMR, the non-therapeutic use of antimicrobials in food animal production is considered an important one (Aarestrup, 2005; de Souza & Hidalgo, 1997; Koike et al., 2017; Levy & Bonnie, 2004).

Increasing evidences of AMR from food animals specially poultry led several countries limit or even the complete ban of antibiotic growth promoters (AGPs) in food animal production (de Souza & Hidalgo, 1997; WHO, 2017). The European Commission banned the marketing and use of AGPs in feed nutrition since 2006 (di Gioia & Biavati, 2018). Such impose on the use of AGPs led the livestock and poultry raisers, and the animal researchers to explore viable alternatives that can improve the gut health and natural immunity of food animals (Callaway et al., 2021; Evangelista et al., 2021; Gaggìa et al., 2010; Marquardt & Li, 2018; Seidavi et al., 2021). In this sense, the use of probiotic microorganisms alone or together with prebiotics, enzymes, and organic acids has gained much attention (Elgeddawy et al., 2020; Hussein et al., 2020; Windisch et al., 2008).

Probiotics are living non-pathogenic microorganisms in single or mixed cultures that, when administered in sufficient amounts, can cause beneficial effects such as enhanced growth rates, improved immune response, and increased resistance to harmful bacteria (Zheng et al., 2016).

Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) or Lactobacilli are Gram-positive and catalase-negative bacteria, which are highly beneficial probiotic organisms and have special features that make them safe (Karami et al., 2017; Puranik et al., 2019). Lactobacilli become established in the gastro-intestinal (GI) tract of chicks immediately after hatching, and their metabolic activity lowers the pH of the digesta, inhibiting the growth of enterobacteria and other undesirable bacteria (Zhao et al., 2007). Several previous reports had shown that LAB improves the growth performance, feed efficiency, and the immune response of chickens through enhancing the intestinal development and nutrients absorption, regulating the mucosal immune system, inhibiting intestinal pathogen colonization and infection, and reshaping intestinal microbiota (Bajagai et al., 2016; Mehdi et al., 2018; Shim et al., 2010; Wang & Gu, 2010). However, it's important to remember that they have the potential to spread antimicrobial resistance to harmful bacteria (Ammor et al., 2007). The safety of these microorganisms, especially the presence of possibly transferable antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs), is a concern (Ammor et al., 2007). Intrinsic and acquired resistance by mutation are thought to present a low risk of horizontal spread, but acquired resistance mediated by additional genes is thought to have the highest risk of horizontal spread (Henriques Normark & Normark, 2002; Levy & Bonnie, 2004). Some ARGs have been detected in LAB and probiotic bacteria, which are assumed to have been acquired through horizontal transmission (Ammor et al., 2007).

Furthermore, the widespread usage of probiotic bacteria in conjunction with or in close association with antibiotic use, or rather misuse, can build up an antibiotic resistance gene in probiotic bacteria (Wong et al., 2015). Probiotic bacteria are known to harbor intrinsic and mobile genetic elements that confer resistance to a wide variety of antibiotics (Zheng et al., 2017).

Presently, different commercial probiotic products marketed globally are available for use in poultry. In Bangladesh, there has been a growing demand for poultry probiotics since the government of Bangladesh has banned the use of antibiotics as growth promoters in poultry and livestock with the enactment of the Fish Feed and Animal Feed Act 2010. There are several commercial probiotic products available for use in poultry production in Bangladesh. The Department of Livestock Services (DLS) under the Ministry of Fisheries and Livestock of Bangladesh gives NOC (No Objection Certificate) to import probiotics from abroad. The poultry probiotic products used in this study were imported by Bangladeshi companies having approval from the DLS. However, in the emergence of antimicrobial resistance, the probiotic products lack evidence of being free from any ARGs. Therefore, the study was conducted to identify the ARGs in Lactobacillus spp. from commercially available poultry probiotic products and in vitro assessment of their potential to spread among E. coli.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Probiotic samples

A total of 35 probiotic samples of seven different commercial products from seven brands/companies (five from each brand) commonly used in poultry were purchased from veterinary pharmacies as products of seven companies were available at that time in the market. Products of Brand 2 and 4 were of a single production batch while products of other brands were of two batches. Different species of Lactobacilli were the common bacteria with other probiotic organisms in all the samples as per product information provided by the pharmaceutical companies (Supplementary Table 1). Each sample was coded with a unique identification number.

2.2. Culture of Lactobacillus spp

The protocol described earlier by Thakur et al. (2017) was followed for the isolation and identification of Lactobacillus spp. Briefly, after homogenization of each sample, 0.1 g of sample was diluted in sterile normal saline and subsequently made 10-fold serial dilution with distilled water. Ten µL of each dilution was inoculated into 10 mL of nutrient broth (NB) and incubated at 37⁰C for 24 h. A loopful of culture broth was streaked onto deMan Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) agar media (Himedia, India, M641) (Jomehzadeh et al., 2020). The border of agar plates was sealed with parafilm to make anaerobic conditions and then incubated at 37⁰C for 24–48 h. The presumptive positive round and creamy white colonies of Lactobacillus spp. as described by Forouhandeh et al. (2010) were picked and subcultured twice subsequently on MRS agar plates to obtain pure colonies.

2.3. Microscopic examination and biochemical tests

All the isolates were Gram stained with Grams Stain-Kit (HiMedia, India) on clean glass slides and examined microscopically under 100x objectives with immersion oil. The presumptive Lactobacillus spp. was Gram-positive, violet in color, short rod and/or round in shape and arranged in chain or cluster. Biochemical tests such as catalase, indole, and methyl red tests were performed with all the isolates as per the methods described earlier (Thakur et al., 2017).

2.4. Molecular identification

2.4.1. DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from the pure culture of Lactobacillus spp. using the “boiling” method as described earlier (Dashti et al., 2009). Briefly, 1 mL aliquot of overnight cultures in NB was taken into a 1.5 mL DNase/RNase-free eppendorf tube using DNase/RNase free pipette tips and centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 rpm. The supernatant was discarded, and the colony sediment was washed twice with 200 μL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. The pelleted bacterial cells were re-suspended in 200 μL of double distilled water (DDW) and vortexed. The suspension was boiled for 15 min at 100⁰C on a hot water bath. The eppendorf tube was kept on ice for 15 min just after boiling and then centrifuged for 5 min at 14,000 rpm. Finally, 100 µL of supernatant was carefully transferred into another DNase/RNase-free eppendorf tube and stored at –20⁰C as a DNA template for PCR assay.

2.4.2. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

PCR was used to confirm the isolates as Lactobacillus spp. that were culturally and biochemically positive. The 16S-23S rRNA gene-specific primers (forward: 5′-TGG AAA CAG GTG CTA ATA CCG-3′ and reverse: 5′-CCA TTG TGG AAG ATT CCC-3′) were used to amplify the target fragment sizes of 247 bp as described earlier (McOrist et al., 2002). PCR was performed in a total volume of 25 µL using a thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems Veriti™ 96-Well Thermal Cycler). The reaction mixture contained 12.5 µL of master mix (Biolabs, USA), 1 µL of each forward and reverse primers, 9 µL of nuclease-free water, and 1.5 µL of DNA template. The PCR condition was initial denaturation at 94⁰C for 4 min, followed by 28 cycles of denaturation at 94⁰C for 1 min, annealing at 54⁰C for 1 min, extension at 72⁰C for 1 min, and final extension at 72⁰C for 4 min McOrist et al. (2002).

2.4.3. Agarose gel electrophoresis

PCR products were subjected to gel electrophoresis on 1.5% UltraPure™ Agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (5 μg/mL) for 50 min at a constant 100 V. The resulting band of PCR product was visualized under a UV transilluminator and photographed.

2.5. Antimicrobial susceptibility test

The antimicrobial susceptibility test was performed with the Lactobacillus spp. isolates (n = 35) using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method as per guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2018). The turbidity of each bacterial suspension was adjusted to 0.5 McFarland standard, then inoculated onto the Mueller-Hinton agar plate (MHA; Himedia, India). Finally, a commercial antimicrobial-impregnated disk (Biomaxima, Polland) was placed over the agar surface using sterile forceps and incubated at 37⁰C for 24 h. A total of 18 antimicrobials of 10 different classes were tested (Supplementary Table 2). The width of the inhibitory zones was measured in millimeters using a measuring scale across the center of the discs after incubation. The results were interpreted following criteria set by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2018) and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST, 2018). The bacteria were reported as sensitive, intermediate, or resistant to each of the antimicrobial agents used in the test.

2.6. Detection of antimicrobial resistance genes

2.6.1. Detection of β-lactamase genes

A multiplex PCR was performed using particular primers specified in Supplementary Table 3 to identify the β-lactamase-encoding genes (broad-spectrum β-lactamases: blaTEM, blaSHV, and extended-spectrum β-lactamases: blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2) in Lactobacillus spp. as per the protocol described by Le et al. (2015). PCR was performed in a total volume of 25 µL using a thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems Veriti™ 96-Well Thermal Cycler). The reaction mixture contained 12.5 µL of master mix (Biolabs, USA), 1 µL of each forward and reverse primers, 3.5 µL of nuclease-free water, and 1 µL of DNA template. The PCR condition was initial denaturation at 95⁰C for 5 min, followed by 25 cycles of denaturation at 95⁰C for 30 s, annealing at 60⁰C for 1 min, extension at 72⁰C for 1 min, and final extension at 72⁰C for 10 min. The positive (containing E. coli with known β-lactamase genes: BAU-CM42Ec [MT820240], BAU-CM226 [MT820299], BAU-CM173Ec [MT820250], and BAU-SW46Ec [MT822177]) and negative (sterile phosphate buffer saline) controls were included in each run. The PCR amplicons were visualized by using a UV-transilluminator and photographed. A 100-bp molecular weight standard ladder was included in each run.

2.6.2. Detection of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (PMQR) genes

A standardized multiplex PCR assay targeting PMQR genes (qnrA, qnrB, and qnrS) in Lactobacillus spp. was used in this study (Robicsek, Strahilevitz, Sahm, Jacoby, & Hooper, 2006). The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 3. PCR was performed with a 25 μL reaction mixture, which contained 12.5 µL of PCR master mix, 1.5 µL of each of the forward and reverse primers, 2.5 µL of nuclease-free water, and 1 µL of DNA template. The following cycling parameters were used: an initial denaturation at 94⁰C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 94⁰C for 45 s, annealing at 57⁰C for 45 s, extension at 72⁰C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72⁰C for 8 min. The positive (containing E. coli with known PMQR genes: BAU-CM96Ec [MT820256], BAU-CM100 [MT796965], and BAU-CM160Ec [MT820281]) and negative (sterile phosphate buffer saline) controls were included in each run. The PCR amplicons were visualized by using a UV-transilluminator and photographed.

2.6.3. Detection of tetracycline resistance genes

A standardized duplex PCR test was used targeting tetracycline resistance genes (tetA and tetB) in Lactobacillus spp. (Goswami et al., 2008). The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 3. PCR was performed in a total volume of 25 µL containing 12.5 µL of master mix (Biolabs, USA), 1 µL of each forward and reverse primers, 7.5 µL of nuclease-free water, and 1 µL of DNA template. The PCR condition was initial denaturation at 94⁰C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94⁰C for 1 min, annealing at 56⁰C for 1 min, extension at 72⁰C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72⁰C for 7 min. The positive (containing E. coli with known tetracycline resistance genes: BAU-B247 [MZ067440] and BAU-SW1 [MZ067452]) and negative (sterile phosphate buffer saline) controls were used in each run. The PCR amplicons were visualized by using a UV-transilluminator and photographed.

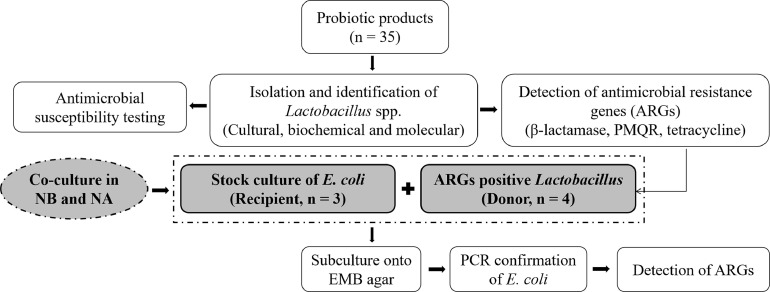

2.7. Assessment of in vitro horizontal gene transfer

2.7.1. Co-culture of Lactobacillus spp. and E. coli

Antimicrobial resistance gene-positive isolates of Lactobacillus spp. (n = 4) were inoculated into NB and incubated at 37⁰C for 24 h. Stock cultures of E. coli (n = 3, BAU-CM155 [MT834995], BAU-CM252 [MT834996], and BAU-SW65 [MT835006]) that were previously characterized by Parvin (2020) were obtained from Population Medicine and AMR laboratory and used as recipients in this study. The recipient BAU-CM252 E. coli isolate was negative for blaSHV, blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2, qnrA, qnrB, qnrS, tetA, tetB, the BAU-CM155 E. coli isolate was negative for blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2, qnrA, tetA, tetB, and the BAU-SW65 isolate was negative for blaSHV, blaCTX-M-2, qnrA, qnrB, qnrS. However, the E. coli isolates were revived in NB after incubation at 37⁰C for 24 h, and reconfirmed for the absence of aforesaid resistance genes by multiplex PCR as described elsewhere. The isolates of Lactobacillus spp. and E. coli used for co-culture are listed in Table 1, and the layout of co-culture was illustrated in Fig. 1. A loopful of cultured Lactobacillus spp. and E. coli was inoculated into NB together, and onto a same nutrient agar (NA) plate side by side, and incubated at 37⁰C for 24 h. Then, a loopful culture from NB and two colonies of E. coli from NA were inoculated onto EMB (Eosin Methylene Blue) agar to obtain pure colonies. The E. coli isolates were characterized by dark blue color colonies with metallic sheen on EMB agar, and positive reaction to catalase, indole, MR, and TSI tests. Finally, DNA was extracted from pure colonies of E. coli, and subjected to PCR assay for confirmation of E. coli and detection of antimicrobial resistance genes.

Table 1.

Isolates of Lactobacillus spp. (donor) and E. coli (recipient) containing different antimicrobial resistance genes used for co-culture.

| Lactobacillus spp. (donor) | E. coli (recipient) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name of the isolate | Resistance genes | Name of the isolate | Resistance genes | Remarks |

| Ep4 | blaTEM, blaCTXM-1, blaCTXM-2, qnrS, tetA | E1 (BAU-CM252) | blaTEM | E1 recipient isolate was negative for blaSHV, blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2, qnrA, qnrB, qnrS, tetA and tetB |

| Pb3 | qnrS | E2 (BAU-SW65) | blaTEM, blaCTXM-1 | E2 recipient isolate was negative for blaSHV, blaCTX-M-2, qnrA, qnrB, qnrS |

| Pb4 | qnrS, tetB | E3 (BAU-CM155) | qnrB, qnrS | E3 recipient isolate was negative for blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2, qnrA, tetA and tetB |

| Pb5 | qnrS, tetB | |||

Fig. 1.

The layout of co-culture of Lactobacillus spp. and E. coli.

2.7.2. Detection of resistance genes in E. coli recovered from co-culture

The presence of β-lactamase genes (blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2), PMQR genes (qnrA, qnrB, qnrS), and tetracycline genes (tetA, tetB) in E. coli were determined using standardized multiplex PCR with specific primers listed in Supplementary Table 3. The PCR protocol was followed for respective β-lactamase (blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2), PMQR (qnrA, qnrS), and tetracycline (tetA, tetB) genes. The PCR product was electrophoresed on 1.5% agarose gel as described elsewhere.

3. Results

3.1. Cultural, morphological and biochemical properties of Lactobacillus spp

Lactobacillus spp. were successfully isolated from all the 35 probiotic samples of seven different brands. On MRS agar, Lactobacillus spp. produced round and creamy white colonies (Supplementary Fig. 1). Morphologically, the isolates were Gram positive rod/short-rod shaped. Biochemically, all the isolates were catalase and indole negative and methyl red positive.

3.2. Results of molecular detection of Lactobacillus spp

All the isolates were confirmed as Lactobacillus spp. by PCR as they generated 247 bp fragment size on amplification (Supplementary Fig. 2).

3.3. Antimicrobial resistance pattern of Lactobacillus spp

The antimicrobial susceptibility test revealed that cefepime (82.9%) and cefotaxime (77.1%) had the highest resistance, followed by penicillin G (68.6%), oxacillin, cefuroxime and ofloxacin (62.9%) (Fig. 2). The least resistance was observed to ciprofloxacin (5.7%); and nalidixic acid, vancomycin, and clindamycin (11.4%). None of the isolates were resistant to linezolid and levofloxacin. Brand-wise resistance to antimicrobials revealed that all isolates from brand 1, brand 5 and brand 6 showed a higher rate of resistance to penicillin G, ampicillin, amoxicillin, oxacillin, cefuroxime, cefotaxime, cefepime, and meropenem (Supplementary Table 4).

Fig. 2.

Antimicrobial resistance pattern of Lactobacillus spp. isolated from probiotic samples.

Legends: R = Resistant, I = Intermediate, S = Susceptible.

3.4. Distribution of antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs)

Several ARGs were detected in five isolates of Lactobacillus spp. from probiotic samples of three different brands/companies (Table 2). Among plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes (qnrA, qnrB, qnrS), only qnrS was detected in four (11.4%) isolates. The β-lactamase – blaTEM and tetracycline resistance gene - tetB were detected in two isolates. blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2, and tetA were also identified in one isolate. Brand-wise analysis revealed that one isolate from Brand 4 was positive for blaTEM, blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2, qnrS and tetA genes, and one isolate from Brand 2 was positive for the blaTEM gene (Supplementary Fig. 3), and three isolates from Brand 7 harbored qnrS gene (Supplementary Fig. 4 a,b), of which, two were positive for tetB also (Supplementary Fig. 5 a,b).

Table 2.

Antimicrobial resistance genes in Lactobacillus spp. isolated from probiotic samples of different brands/companies.

| Brand/Company | Probiotic bacteria | Resistance genes* |

|---|---|---|

| Brand 2 | Lactobacillus spp. | blaTEM (1) |

| Brand 4 | Lactobacillus spp. | blaTEM (1), blaCTX-M-1 (1), blaCTX-M-2 (1), qnrS (1), tetA (1) |

| Brand 7 | Lactobacillus spp. | qnrS (3), tetB (2) |

| Brand 1 | Lactobacillus spp. | None |

| Brand 3 | Lactobacillus spp. | None |

| Brand 5 | Lactobacillus spp. | None |

| Brand 6 | Lactobacillus spp. | None |

All the isolates were screened for β-lactamases - blaTEM, blaSHV, blaCTX-M-1, bla CTX-M-2; Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes - qnrA, qnrB, qnrS; Tetracycline resistance genes - tetA and tetB.

Values in the parenthesis indicate the number of isolates of Lactobacillus spp.

3.5. Horizontal transfer of resistance genes from Lactobacillus spp. to E. coli

Of 22 co-culture combinations, transfer of resistance gene(s) from Lactobacillus spp. to E. coli was observed in 10 (45.5%) combinations (Table 3). Considering the culture media (nutrient agar/nutrient broth), 6 (42.9%) out of 14 culture combinations resulted in the transmission of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance gene (qnrS) from Lactobacillus to E. coli (Table 3). In the case of tetracycline resistance gene, the transfer of tetA gene from Lactobacillus spp. to E. coli occurred in all four co-culture combinations. However, no transmission of β-lactamase genes from Lactobacillus to E. coli was observed in any co-culture combinations.

Table 3.

Horizontal transfer of antimicrobial resistance gene from probiotic bacteria Lactobacillus spp. to E. coli.

| Co-culture combination (Lactobacillus spp. + E. coli) | Co-culture media (NB/NA) | Donor organism (Lactobacillus spp. – positive for resistance gene of interest) | Recipient organism (E. coli – negative for resistance gene of interest) | Transfer result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb3+E2 | NA | Pb3 (qnrS) | E2 | E2 (qnrS) |

| Pb3+E2 | NB | Pb3 (qnrS) | E2 | E2 (qnrS) |

| Pb4+E2 | NA | Pb4 (qnrS) | E2 | E2 (qnrS) |

| Pb4+E2 | NB | Pb4 (qnrS) | E2 | E2 (qnrS) |

| Pb5+E2 | NA | Pb5 (qnrS) | E2 | E2 (qnrS) |

| Pb5+E2 | NB | Pb5 (qnrS) | E2 | E2 (qnrS) |

| Pb3+E1 | NA | Pb3 (qnrS) | E1 | No transmission |

| Pb3+E1 | NB | Pb3 (qnrS) | E1 | No transmission |

| Pb4+E1 | NA | Pb4 (qnrS) | E1 | No transmission |

| Pb4+E1 | NB | Pb4 (qnrS) | E1 | No transmission |

| Pb5+E1 | NA | Pb5 (qnrS) | E1 | No transmission |

| Pb5+E1 | NB | Pb5 (qnrS) | E1 | No transmission |

| Ep4+E1 | NA | Ep4 (qnrS) | E1 | No transmission |

| Ep4+E1 | NB | Ep4 (qnrS) | E1 | No transmission |

| Ep4+E1 | NA | Ep4 (blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2) | E1 | No transmission |

| Ep4+E1 | NB | Ep4 (blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2) | E1 | No transmission |

| Ep4+E3 | NA | Ep4 (blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2) | E3 | No transmission |

| Ep4+E3 | NB | Ep4 (blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2) | E3 | No transmission |

| Ep4+E1 | NA | Ep4 (tetA) | E1 | E1 (tetA) |

| Ep4+E1 | NB | Ep4 (tetA) | E1 | E1 (tetA) |

| Ep4+E3 | NA | Ep4 (tetA) | E3 | E3 (tetA) |

| Ep4+E3 | NB | Ep4 (tetA) | E3 | E3 (tetA) |

Lactobacillus spp. isolates: Pb3, Pb4, Pb5, and Ep4; E. coli isolates: E1, E2, and E3.

NA = Nutrient agar, NB = Nutrient broth.

4. Discussion

It is well established that probiotics have a beneficial effect on gut health and the production performance of poultry. However, it's important to remember that they have the potential to spread antibiotic resistance to harmful bacteria. The presence of transferable resistance genes is thought to have the highest risk of horizontal spread (Henriques Normark & Normark, 2002; Levy & Bonnie, 2004). The findings of the present study confirmed the presence of one or more antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) in some isolates of Lactobacillus spp. from commercial poultry probiotic products. And co-culture of Lactobacillus spp. with E. coli resulted in the transmission of some of the ARGs to E. coli, which is thought to present the potential risk of the spread of antimicrobial resistance among the poultry population, humans, and the environment as well through horizontal transfer (Nawaz et al., 2011).

The identified ARGs were β-lactamases encoding genes (blaTEM, blaCTXM-1 and blaCTXM-2), plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance gene (qnrS), and tetracycline resistance genes (tetA and tetB). Most importantly, one isolate from Brand 4 harbored blaTEM, blaCTX-M-1, blaCTX-M-2, qnrS, and tetA genes; three isolates from Brand 7 contained qnrS gene. Probiotic bacteria are known to harbor intrinsic and mobile genetic elements that confer resistance to a wide variety of antibiotics (Zheng et al., 2017). Furthermore, the widespread usage of probiotic bacteria in conjunction with or in close association with antibiotic use, or rather misuse, can build up an antibiotic resistance gene in probiotic bacteria (Wong et al., 2015), and can spread to a wider bacterial population through horizontal gene transfer mechanism, mostly by conjugation. In our study, the transfer of qnrS and tetA genes from Lactobacillus spp. to E. coli was observed in more than 40% cases of co-cultures. Thus, it is very likely that probiotic bacteria can transfer resistance genes to gut microbiota of poultry, and eventually to the environment. Previous studies have demonstrated the horizontal transfer of several resistance genes among bacterial species by conjugation (Roberts et al., 1996; Toomey et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2007). Therefore, strains intended for use in feed should be carefully checked for resistance along with other attributes of probiotic bacteria to avoid the inclusion of resistant strains in probiotics (Patterson & Burkholder, 2003).

Antimicrobial sensitivity testing revealed that isolates of Lactobacillus spp. were resistant to several antimicrobials. The highest resistance was observed to cefepime and cefotaxime followed by penicillin G, oxacillin, cefuroxime, and ofloxacin. The least resistance was observed against ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, vancomycin, and clindamycin. Lactobacilli resistance to different antibiotics varies widely (Gueimonde et al., 2013). Lactobacilli are usually sensitive to penicillin and β-lactamase but are more resistant to cephalosporins. Lactic acid bacteria are known to carry plasmids of various sizes, and certain antibiotic resistance determinants have been found on plasmids (Gevers et al., 2003). The high prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant Lactobacillus spp. isolated from poultry probiotic products was associated with the brands, which could be due to brand-level differences in production. Here in this study, plasmid conjugation was not performed to detect and characterize plasmids in recipient strains, which would be worthwhile. However, we screened carefully both the donor Lactobacilli and recipient E. coli for the absence or presence of ARGs of interest. Lactobacillus isolates could be genotyped to provide more information on the genetic relatedness of those strains used in probiotics. Furthermore, the presence of other bacteria other than Lactobacillus as reservoirs of ARGs in the original products could not be ruled out.

5. Conclusions

The findings of the present study confirmed that some isolates of Lactobacillus spp. from poultry probiotic products of some brands/pharmaceutical companies contained one or more antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs). The co-culture of Lactobacillus spp. with E. coli resulted in the transmission of some of the ARGs to E. coli, which is thought to present the potential risk of spread of antimicrobial resistance among the poultry population through horizontal transfer. Therefore, it is necessary to screen ARGs along with other attributes of probiotic bacteria to avoid the inclusion of resistant strains in probiotics.

Ethical statement

The study did not involve any animal or human subjects. However, the study protocol was approved by the departmental Board of Studies and the Committee for Advanced Studies and Research of the university.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.vas.2023.100292.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Aarestrup F.M. Veterinary drug usage and antimicrobial resistance in bacteria of animal origin. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2005;96:271–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2005.pto960401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammor M.S., Belén Flórez A., Mayo B. Antibiotic resistance in non-enterococcal lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria. Food Microbiology. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajagai Y.S., Klieve A.V., Dart P.J., Bryden W.L. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO); Rome, Italy: 2016. Probiotics in animal nutrition: Production, impact and regulation, FAO animal production and health paper (FAO) eng no. 179. [Google Scholar]

- Callaway T.R., Lillehoj H., Chuanchuen R., Gay C.G. Alternatives to antibiotics: A symposium on the challenges and solutions for animal health and production. Antibiotics. 2021;10:471. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10050471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC Combating antimicrobial resistance in people and animals: A one health approach [WWW document] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- CLSI . 27th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, PA: 2018. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-seventh informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S27., CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. CLSI supplement M1002018. [Google Scholar]

- Dashti A.A., Jadaon M.M., Abdulsamad A.M., Dashti H.M. Heat treatment of bacteria: A simple method of DNA extraction for molecular techniques. Kuwait Medical Journal. 2009;41:117–122. [Google Scholar]

- de Souza C.M., Hidalgo M.P.L. The medical impact of antimicrobial use in food animals. Report of a WHO Meeting; Berlin, Germany; World Heal. Organ.; 1997. pp. 13–17. 13-17 October 1997. [Google Scholar]

- di Gioia D., Biavati B. Probiotics and prebiotics in animal health and food safety: Conclusive remarks and future perspectives. Probiotics and Prebiotics in Animal Health and Food Safety. 2018 doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-71950-4_11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elgeddawy S.A., Shaheen H.M., El-Sayed Y.S., Abd Elaziz M., Darwish A., Samak D., Batiha G.E., Mady R.A., Bin-Jumah M., Allam A.A., Alagawany M., Taha A.E., El-Mleeh A., El-Sayed S.A.A., Abd El-Hack M.E., Elnesr S.S. Effects of the dietary inclusion of a probiotic or prebiotic on florfenicol pharmacokinetic profile in broiler chicken. ournal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition. 2020;104:549–557. doi: 10.1111/jpn.13317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST EUCAST breakpoints. European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 2018:0–77. [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista A.G., Corrêa J.A.F., Pinto A.C.S.M., Luciano F.B. The impact of essential oils on antibiotic use in animal production regarding antimicrobial resistance – a review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2021:1–17. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2021.1883548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forouhandeh H., Vahed S.Z., Hejazi M.S., Nahaei M.R., Dibavar M.A. Isolation and phenotypic characterization of lactobacillus species from various dairy products. Current Research in Bacteriology. 2010;3:84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Gaggìa F., Mattarelli P., Biavati B. Probiotics and prebiotics in animal feeding for safe food production. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2010;141 doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gevers D., Huys G., Swings J. In vitro conjugal transfer of tetracycline resistance from Lactobacillus isolates to other Gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2003;225:125–130. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00505-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goswami P.S., Gyles C.L., Friendship R.M., Poppe C., Kozak G.K., Boerlin P. Effect of plasmid pTENT2 on severity of porcine post-weaning diarrhoea induced by an O149 enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Veterinary Microbiology. 2008;131:400–405. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueimonde M., Sánchez B., de los Reyes-Gavilán C.G., Margolles A. Antibiotic resistance in probiotic bacteria. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2013;4:1–6. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques Normark B., Normark S. Evolution and spread of antibiotic resistance. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2002;252:91–106. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein E.O.S., Suliman G.M., Alowaimer A.N., Ahmed S.H., Abd El-Hack M.E., Taha A.E., Swelum A.A. Growth, carcass characteristics, and meat quality of broilers fed a low-energy diet supplemented with a multienzyme preparation. Poultry Science. 2020;99:1988–1994. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2019.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jomehzadeh N., Javaherizadeh H., Amin M., Saki M., Al-Ouqaili M.T.S., Hamidi H., Seyedmahmoudi M., Gorjian Z. Isolation and identification of potential probiotic Lactobacillus species from feces of infants in southwest Iran. International Journal of Infectious Diseases : IJID : Official Publication of the International Society for Infectious Diseases. 2020;96:524–530. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karami S., Roayaei M., Hamzavi H., Bahmani M., Hassanzad-Azar H., Leila M., Rafieian-Kopaei M. Isolation and identification of probiotic Lactobacillus from local dairy and evaluating their antagonistic effect on pathogens. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Investigation. 2017;7:137. doi: 10.4103/jphi.jphi_8_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike S., Mackie R., Aminov R. Agricultural use of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Natural Environments and Long-term Effects. 2017:217–250. [Google Scholar]

- Le Q.P., Ueda S., Nguyen T.N.H., Dao T.V.K., Van Hoang T.A., Tran T.T.N.…Vien Q.M. Characteristics of extended-spectrum β-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli in retail meats and shrimp at a local market in Vietnam. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 2015;12(8):719–725. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2015.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy S.B., Bonnie M. Antibacterial resistance worldwide: Causes, challenges and responses. Nature Medicine. 2004;10:S122–S129. doi: 10.1038/nm1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt R.R., Li S. Antimicrobial resistance in livestock: Advances and alternatives to antibiotics. Animal Frontiers. 2018;8:30–37. doi: 10.1093/af/vfy001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McOrist A.L., Jackson M., Bird A.R. A comparison of five methods for extraction of bacterial DNA from human faecal samples. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2002;50:131–139. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(02)00018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehdi Y., Létourneau-Montminy M.-.P., Gaucher M.-.L., Chorfi Y., Suresh G., Rouissi T., Brar S.K., Côté C., Ramirez A.A., Godbout S. Use of antibiotics in broiler production: Global impacts and alternatives. Animal Nutrition. 2018;4:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz M., Wang J., Zhou A., Ma C., Wu X., Moore J.E., Cherie Millar B., Xu J. Characterization and transfer of antibiotic resistance in lactic acid bacteria from fermented food products. Current Microbiology. 2011;62:1081–1089. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9856-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvin M.S. Faculty of Veterinary Science, Bangladesh Agricultural University; Mymensingh, Bangladesh: 2020. A PhD thesis, submitted to the Department of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson J.A., Burkholder K.M. Application of prebiotics and probiotics in poultry production. Poultry Science. 2003;82:627–631. doi: 10.1093/ps/82.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puranik S., Munishamanna K.B., Sruthy K.S. Isolation and characterization of lactic acid bacteria from banana pseudostem. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences. 2019;8:39–47. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2019.803.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts M.C., Facinelli B., Giovanetti E., Varaldo P.E. Transferable erythromycin resistance in Listeria spp. isolated from food. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1996;62:269–270. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.269-270.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robicsek A., Strahilevitz J., Sahm D.F., Jacoby G.A., Hooper D.C. qnr prevalence in ceftazidime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates from the United States. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2006;50(8):2872–2874. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01647-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidavi A., Tavakoli M., Slozhenkina M., Gorlov I., Hashem N.M., Asroosh F., Taha A.E., Abd El-Hack M.E., Swelum A.A. The use of some plant-derived products as effective alternatives to antibiotic growth promoters in organic poultry production: A review. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2021;28:47856–47868. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-15460-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim Y.H., Shinde P.L., Choi J.Y., Kim J.S., Seo D.K., Pak J.I., Chae B.J., Kwon I.K. Evaluation of multi-microbial probiotics produced by submerged liquid and solid substrate fermentation methods in broilers. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences. 2010;23:521–529. [Google Scholar]

- Thakur M., Deshpande H.W., Bhate M.A. Isolation and identification of lactic acid bacteria and their exploration in non-dairy probiotic drink. International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences. 2017;6:1023–1030. doi: 10.20546/ijcmas.2017.604.127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey N., Monaghan Á., Fanning S., Bolton D.J. Assessment of antimicrobial resistance transfer between lactic acid bacteria and potential foodborne pathogens using in vitro methods and mating in a food matrix. Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 2009;6:925–933. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2009.0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Gu Q. Effect of probiotic on growth performance and digestive enzyme activity of Arbor Acres broilers. Research in Veterinary Science. 2010;89:163–167. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . World Health Organization. 2020. Antibiotic resistance [WWW document] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . World Health Organization; 2017. WHO guidelines on use of medically important antimicrobials in food-producing animals. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windisch W., Schedle K., Plitzner C., Kroismayr A. Use of phytogenic products as feed additives for swine and poultry. Journal of Animal Science. 2008;86:E140–E148. doi: 10.2527/jas.2007-0459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong A., Ngu D.Y.Saint, Dan L.A., Ooi A., Lim R.L.H. Detection of antibiotic resistance in probiotics of dietary supplements. Nutrition Journal. 2015;14:12–17. doi: 10.1186/s12937-015-0084-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Yeh E., Hall G., Cripe J., Bhagwat A.A., Meng J. Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from retail foods. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2007;113:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R., Sun J., Mo H., Zhu Y. Analysis of functional properties of Lactobacillus acidophilus. World Journal of Microbiology & Biotechnology. 2007;23:195–200. doi: 10.1007/s11274-006-9209-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng A., Luo J., Meng K., Li J., Bryden W.L., Chang W., Zhang S., Wang L.X.N., Liu G., Yao B. Probiotic (Enterococcus faecium) induced responses of the hepatic proteome improves metabolic efficiency of broiler chickens (Gallus gallus) BMC Genomics. 2016;17 doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2371-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M., Zhang R., Tian X., Zhou X., Pan X., Wong A. Assessing the risk of probiotic dietary supplements in the context of antibiotic resistance. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2017;8:1–8. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.