Abstract

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is the most common type of diabetes, affecting 6.28% of the population worldwide. Over the decades, multiple therapies and drugs have been developed to control T2D, but they are far from a long-term solution. Stem cells are promising as novel regenerative treatments, especially mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), which are highly versatile in their regenerative and paracrine capabilities and characteristics. This makes them the most commonly used adult stem cells and ideal candidates to treat diabetes.

Objective

To assess the safety and efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in treating Type 2 diabetes (T2D) in humans.

Methods

Mesenchymal stem cell-based treatments were studied in 262 patients. A total of 6 out of 58 trials fit our inclusion criteria in the last five years.

Results

The treatment of patients with MSCs reduced the dosage of anti-diabetic drugs analyzed over a follow-up period of 12 months. The effective therapy dosage ranged from 1×106 cells/kg to 3.7×106 cells/kg. After treatment, HbAc1 levels were reduced by an average of 32%, and the fasting blood glucose levels were reduced to an average of 45%. The C-peptide levels were decreased by an average of 38% in 2 trials and increased by 36% in 4 trials. No severe adverse events were noted in all trials.

Conclusion

This analysis concludes that MSC treatment of type 2 diabetes is safe and effective. A larger sample size is required, and the trials should also study the effect of differentiated MSCs as insulin-producing cells.

Keywords: stem cell, regenerative medicine, diabetes, mesenchymal stem cells

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a heterogeneous disease characterized by the dysregulation of lipids, carbohydrates, and proteins and associated with impaired insulin secretion, insulin resistance, or both.1 In comparison to Type 1 diabetes, also known as insulin-dependent diabetes, T2DM has a higher prevalence worldwide, accounting for approximately 537 million people in 2021, a number projected to rise to 643 and 783 million people by 2030 and 2045, respectively.2 T2DM majorly occurs in people over 50 years of age but has become increasingly frequent in adults and children below 20.3 T2DM, if not controlled, can lead to long-term complications such as ischemic heart attack, stroke, chronic kidney disease, and diabetic retinopathy.4 (Conventional therapies for T2DM can include lifestyle and diet changes to control the weight and caloric inputs, as well as oral glucose-lowering drugs such as liraglutide (Victoza), semaglutide (Ozempic), and dulaglutide (Trulicity),5 and ultimately daily insulin injections.6 For late-stage T2DM, transplantation of the pancreas remains the mainstay option, but it is costly and characterized by a high risk of recurrence.7 There are multiple limitations to the conventional treatment methods for T2DM. The chemotherapeutic treatments are associated with several side effects, including hepatotoxicity, hypoglycemia, gastrointestinal disturbances, respiratory tract infection, and others. Moreover, these treatments do not reduce the decline of pancreatic β-cell function but instead mitigate the symptoms of the disease (Figure 1).8 Insulin injections, given when the glucose level is not controlled by lifestyle intervention or chemotherapeutic agents, are invasive and associated with poor compliance and can lead to adverse events such as lipohypertrophy, infections, skin allergy at the site of injection, and development of antibodies against the exogenous insulin.9 Alternative therapies are essential for the management of T2DM. Novel stem cell-based therapies were promising for their treatment.10 These cells can renew, regenerate, and secrete crucial factors to maintain other cell types. These stem cells are being assessed in clinical trials to treat various diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease,11 multiple sclerosis,12 multiple myeloma,13 etc. There are three main types of stem cells used for T2DM treatment, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), hematopoietic stem cells, and induced pluripotent stem cells.14 MSCs are the most utilized in T2DM clinical trials because they can be isolated from various autologous or allogenic tissues, including bone marrow, adipose tissue, and blood.15 MSCs can differentiate in multiple cell types and have low immunogenicity. They express low levels of MHC class I, no MHC class II, and do not trigger a proliferative T-cells response.16 To overcome the drawbacks faced by the currently available treatment strategies for type 2 diabetes, stem cell infusion therapies are being developed with the help of mesenchymal stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells, and hematopoietic stem cells. This paper studies the current clinical trials which utilize mesenchymal stem cells and assesses the safety and efficacy of these treatments for late-stage T2DM.

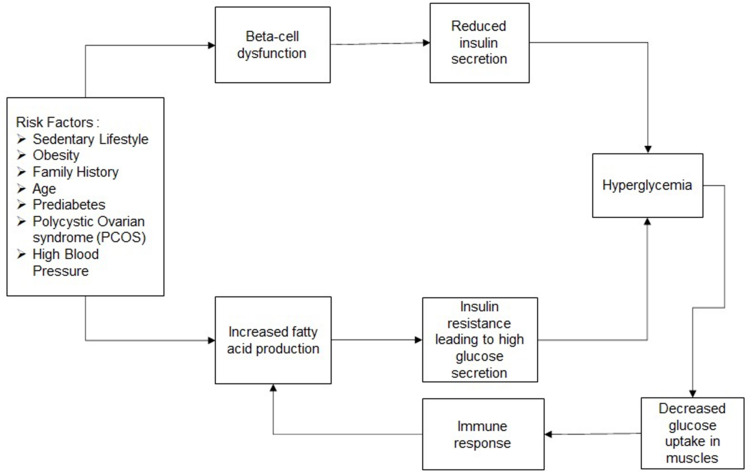

Figure 1.

Flow diagram - T2DM: T2DM is attributed to multiple risk factors, as mentioned above. These factors can cause beta-cell dysfunction over a period of time. Low capacity or dysfunction of the beta cells reduces insulin secretion by the pancreas, which in turn causes hyperglycemia. These risk factors can also lead to increased fatty acid production by the liver, which causes high amounts of glucose secretion to form in the liver. Increased glucose secretion reduces the function of insulin and leads to insulin resistance. Hyperglycaemia leads to low amounts of glucose absorbed by the muscles and causes an immune response. This damages the liver further and increases insulin resistance.

Methods

Search Sources and Strategy

The data were obtained from PubMed and clinicaltrials.gov based on search query terms such as “Type 2 diabetes”, “Stem cell therapies”, “Diabetes”, “Mesenchymal stem cell therapies”, “BM-MSC”, “Diabetes type 2”, “T2DM” DM “BM-HSC”, “UC-MSC”, and limited to completed clinical trials between 2011 and 2021. The search strategy was based on Preserved Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The language was limited to English. Interventional as well as observational studies were included. The meta-analysis did not have clinical trials with insufficient information about the evaluation method, patients suffering from other chronic co-morbidities, and studies with small sample sizes (<10 patients).

Data Extraction

Data extraction was done as per Cochrane guidelines for systematic review. The selection and search were based on the type of trial (interventional or observational), participants (age, sample size, duration of T2DM), treatment of T2DM, and the measure of efficacy such as HbAc1, C-peptide, and FPG (fasting plasma glucose) levels.

Results

The MSCs were characterized by positive and negative markers, including CD90, CD105, CD73, and CD146, and deficient for CD34, CD45, and HLA.

Search Result

A total of 70 trials were collected; only 58 remained after checking for duplication of the records. Out of the 58 clinical trials, only six studies (T1, T2, T3, T4, T5, T6) (Table 1) were included. The remaining ones needed more comprehensive results, had insufficient information about the treatment evaluation methodology, aimed to report the treatment of the long-term comorbidities associated with T2DM instead of the disease, were non-randomized, and participants had other morbidities. The studies included in the meta-analysis were all using injections of autologous MSCs irrespective of their source.

Table 1.

Clinical Trials: MSC-Based Therapies for T2DM

| Identification Code | Clinical Trial Reference | Cell Type Used | Dosage | Enrolled Participants (Age Range) | Intervention Type | Result | Conclusion | Clinical Trial Phase | Country of Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | [17] | BM-MSC | 1×106 cells/kg IV/DPA |

30 (18–50) | Single group assignment (Interventional) Parallel Assignment (RCT) | Adverse events (AE) of hyper-/hypo- glycemia were noted with IV vs. DPA P>0.05 Reduction in HbA1c, FBG, and C-peptide levels after six months, |

BM-MSC therapy was safe with no AE 50% reduction - insulin dose use 50% reduction -in oral drug use |

2 | Vietnam |

| T2 | [18] | BM-MSC | 3.76x106 Cells/kg IV/DPA |

31 (30–65) | Reduction in glycaemic index and HbAc1. Reduction n C-peptide levels. Low insulin resistance | Insulin free for more than four years. | 2 | China | |

| T3 | [19] | WJ-MSC/UC-MSC | 1×106 Cells/kg; DPA |

61 (18–60) | Parallel assignment (interventional) | Improved beta-cell function and insulin sensitivity. Reduction in glycaemic index and insulin requirement. No diabetic complications | Improved beta cells, low insulin requirement, no diabetic complications | 2 | China |

| T4 | [20] | UC-MSC | 1×106 Cells /kg IV |

100 (35–65) | Factorial Assignment | Decreased FPG, 2hPG, and HbA1c levels. ΔCP30/ΔG30 and AUCCP180 were significantly increased, and HOMA-IR was decreased considerably |

LIRA treatment in combination with UC-MSCs improves glucose metabolism and the β cell function in type 2 diabetic patients | 2 | China |

| T5 | [21] | UC-MSC/PD-MSC | 1.35×106 cells/kg IV/DPA |

10 (18–85) | Single group assessment | Simple, safe, and effective therapeutic approach for T2D patients with islet cell dysfunction. | Further large-scale, randomized and well-controlled clinical studies will be required to substantiate these observations | Early 1 | China |

| T6 | [22] | BM-MSC | 1x106 cells/kg IV/DPA |

10 (30–60) | RCT Parallel assessment | Safe and effective treatment with mild adverse effects such as nausea and vomiting in 2 patients | Significant decrease in HbAc1 levels and FBG levels. A slight elevation in C peptide levels after a six-month follow-up. | 1 | India |

Abbreviations: BM–MSC, Bone marrow-derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells; RCT, Randomized Controlled Trials; DPA, Dorsal Pancreatic Artery; IV, Intravenous; HbA1c, Hemoglobin A1C; FBG, Fasting Blood Glucose; WJ-MSC, Wharton’s Jelly derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells; UC-MSC, Umbilical Cord derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance; PD- MSC, Placenta derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells; LIRA, Liraglutide.

Effect of Therapies on Patient Outcomes

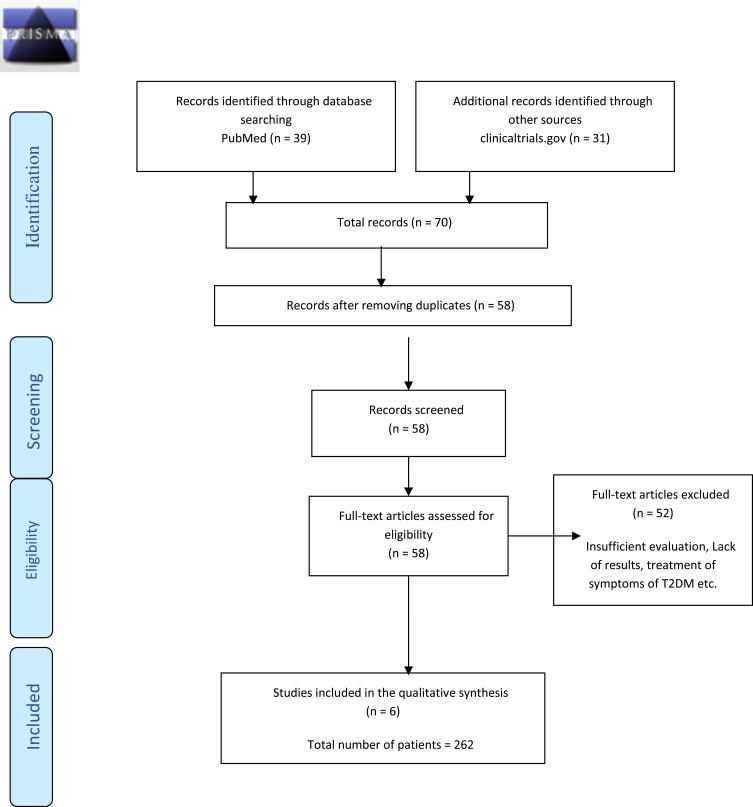

Based on the studied trials, treatment of T2DM using MSCs shows results irrespective of the duration of T2DM and the MSC tissue of origin (Figure 2). The parameters of the studies were similar and led to a reduction in insulin resistance and insulin dependence. Moreover, a significant decrease in HbAc1 and FBG levels suggested improved liver function. The trials also displayed a decrease in C-peptide levels in 2 trials (T1 and T4) out of 6 trials to normal levels, suggesting an improvement in beta islet cells responsible for insulin resistance in the body. The other four trials (T2, T3, T4, and T5) showed increased C-peptide levels.

Figure 2.

Prisma Diagram for study analysis. The diagram depicts the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the studies added to the article.

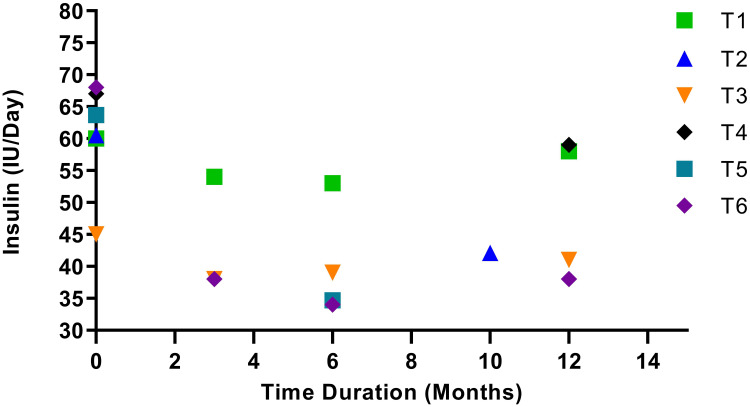

Effect of Therapy on Insulin Resistance

Treatment with MSCs reduces insulin dependence for up to 12 months following the injection. The FBG (fasting blood glucose) was reduced to the normal range of 3.9 to 5.5 g/mmol in all trials. The homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), β-cell function HOMA-β, and insulin sensitivity HOMA- S measured the insulin levels in the participants before and after the study; no significant reduction in insulin resistance was noted in one of the six studies. The five remaining studies did not report insulin resistance measurements. In all studies, insulin resistance was indicated by the amount of insulin required after the treatment (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Insulin requirement before and after MSC treatment. The trials showcased different follow-up times. T1, T3, and T6 showed a decline in insulin requirement for a follow-up period of 3 and 6 months but a steady increase in need at the 12-month follow-up. T5 showed a 45% decrease in insulin requirement when followed up at the 6-month mark, but this study was not followed up further. T4 displayed a 22% lower insulin requirement during the 12-month follow-up period. Insulin requirement for T2 was 30% lower at the ten-month follow-up period, after which the study was not followed up.

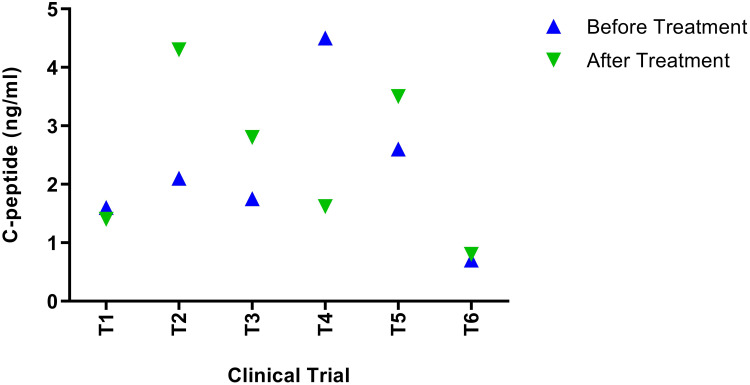

Effect of Therapy on C-Peptide Levels

The fasting C-peptide, obtained after 8–12 hours of patient fasting, is an effective indicator of insulin produced in the body. In three trials, T2, T3, and T5 (Figure 4), the C-peptide levels measured by HOMA-β were higher than 2 ng/mmol. Reduction in the C-peptide level signifies efficient islet cell function as c-peptide levels tend to increase in Type 2 diabetes. This indicates the overproduction of insulin.23 The results in study T4 were found to display C-peptide levels as a potent indicator of the effectiveness of the treatment. Study T1 showed a reduction in c-peptide levels as well, but not to a significant amount. Most studies noted that C-peptide progressively increased with the peak value achieved at six months and a slight decrease later at 12 months. In one study, T6, the C-peptide levels were reduced to normal in the range of 0.5 to 2 ng/mmol and plateaued at the 12-month follow-up mark.

Figure 4.

C-peptide Levels after transplantation of MSCs. T1 and T4 noticed a reduction in c-peptide levels by 12% and 64%, respectively. T2, T3, and T5 noted an increase in the C-peptide levels by 62%, 40%, and 34%, respectively. An increase in T6 was noted after treatment by 10%.

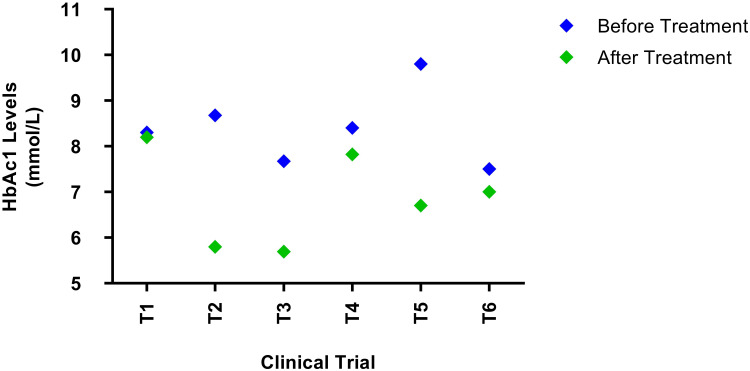

Effect of Therapy on HbA1c Levels

HbAc1 level is a common and effective indicator of the mean glucose level over a long period (2 to 3 months). It provides a much better understanding of long-term glycaemic control than blood and urinary glucose measures. HbAc1 is directly linked to the proportion of glucose bound to the hemoglobin molecules, which occurs continually over the entire life span of the erythrocyte.24 Diabetic patients with very high blood glucose concentrations have 2 to 3 times more HbA1c than normal individuals. The levels of HbAc1 act as effective indicators of the success or failure of the treatment. Upon treatment, all trials observed a significant decrease in the levels of HbAc1 during the three-month follow-up period and a further decline during the 12-month follow-up period. In one study, T1 (Figure 5), the HbAc1 level did not change due to the increased nephropathy in diabetic patients.25

Figure 5.

HbAc1 levels before and after treatment with MSCs. There was a significant decrease in the HbAc1 levels in all trials. After follow up, the HbAc1 levels reduced to 1.2%, 32%,26%,7.1%, 31% and 6% for T1, T2, T3, T4, T5, and T6 respectively.

Adverse Events

All studies observed no severe adverse events other than two studies, T1 and T6 (Table 1), which observed nausea and vomiting in some patients. In one study, T1 noted hypoglycemia. All studies deemed this form of treatment effective and safe.

Discussion

These studies were designed to assess the safety and efficacy of MSCs for the treatment of T2DM. The results from six clinical trials included 262 T2DM patients and demonstrated that MSCs are safe to use and do not display any severe adverse effects; only nausea and vomiting were reported in two clinical trials. The study used mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) because they can easily differentiate into any cell type. They also express low immunogenicity because of low MHC 1 and 2 and do not cause the activation of lymphocytes.26 MSCs were safer than conventional therapies used for late-stage T2DM treatment. The efficiency of MSC therapy was measured based on HbAc1, C-peptide, and FBG levels. Most studies adopted a follow-up period of 12 months after one MSC dosage. The MSC treatment proved to be a long-term solution for most cases. The C-peptide levels remained normal for 12 months following injection. The FBG and HbAc1 levels varied in the different studies but improved in 70% of the patients.

The route of MSC infusion, intravenously or via the dorsal pancreatic artery, did not make a significant difference in the efficacy of the treatment 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up. All studies used autologous MSCs amplified after 3–4 passages. The high number of transplanted cells allows a reduction in the infusion frequency compared to conventional treatment requiring the daily injection of insulin or organ transplantation in more advanced cases. As the cells transplanted were autologous, the number of adverse events remained low compared to allogenic transplants, with the most severe adverse event being hypoglycemia in one study. Recruitment of patients remained low as many needed to fit the inclusion criteria set up by the clinical trials. Conventional treatment of late-stage T2DM generally leads to pancreas transplantation which could cost the patient approximately 110,000 USD. In contrast, MSC transplantation costs 99,000 USD, requiring only a single dose.27 Further trials are required with a more significant number of participants and more follow-up points. Moreover, selecting participants based on the duration of the disease before treatment with MSCs would give more information on the effect of MSC in long-term T2DM.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the studies note that treatment with MSCs is competent and cost-effective. The impact of this treatment mode should be studied with patients in the earlier stage of type 2 diabetes to understand if the treatment would provide long-term results. Moreover, the need for a uniform sample population and inclusion and exclusion criteria reduce the significance of each study. A larger, more uniform sample size and a continuous follow-up period are required. These studies should measure insulin resistance, insulin dependence, C-peptide values, and HbAc1 values.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript does not contain any animal or human studies conducted by any of the authors. This study discusses the impact of stem cells on diabetes and discusses transplantation as a form or treatment and explains the advantages and limitations of autologous transplantation for Type 2 diabetes.

Funding Statement

No funding was received for this work.

Data Sharing Statement

All data is available upon request.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Galicia-Garcia U, Benito-Vicente A, Jebari S, et al. Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:6275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IDF Diabetes Atlas. Diabetes facts & figures; 2021.

- 3.Pulgaron ER, Delamater AM. Obesity and type 2 diabetes in children: epidemiology and treatment. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14(8):508. doi: 10.1007/s11892-014-0508-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Einarson TR, Acs A, Ludwig C, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: a systematic literature review of scientific evidence from across the world in 2007–2017. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):83. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0728-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samar Hafida M. Type 2 Diabetes: Which Medication is Best for Me? Harvard health publishing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Diabetes Association. Summary of revisions: standards of medical care in diabetes-2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(Suppl 1):S4–s6. doi: 10.2337/dc20-Srev [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peracha J, Nath J, Ready A, et al. Risk of post-transplantation diabetes mellitus is greater in South Asian versus Caucasian kidney allograft recipients. Transpl Int. 2016;29(6):727–739. doi: 10.1111/tri.12782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shingler S, Fordham B, Evans M, et al. Utilities for treatment-related adverse events in type 2 diabetes. J Med Econ. 2015;18(1):45–55. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2014.971158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kokil GR, Veedu RN, Ramm GA, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: limitations of conventional therapies and intervention with nucleic acid-based therapeutics. Chem Rev. 2015;115(11):4719–4743. doi: 10.1021/cr5002832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solis MA, Moreno Velásquez I, Correa R, et al. Stem cells as a potential therapy for diabetes mellitus: a call-to-action in Latin America. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2019;11(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s13098-019-0415-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unnisa A, Dua K, Kamal MA. Mechanism of mesenchymal stem cells as a multitarget disease-modifying therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2022;20. doi: 10.2174/1570159X20666220327212414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Visweswaran M, Hendrawan K, Massey JC, et al. Sustained immunotolerance in multiple sclerosis after stem cell transplant. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2022;9(2):206–220. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreau P, Hulin C, Perrot A, et al. Maintenance with daratumumab or observation following treatment with bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone with or without daratumumab and autologous stem-cell transplant in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (CASSIOPEIA): an open-label, randomised, Phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(10):1378–1390. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00428-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bani Hamad FR, Rahat N, Shankar K, et al. Efficacy of stem cell application in diabetes mellitus: promising future therapy for diabetes and its complications. Cureus. 2021;13(2):e13563. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreira A, Kahlenberg S, Hornsby P. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells for diabetes. J Mol Endocrinol. 2017;59(3):R109–r120. doi: 10.1530/JME-17-0117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schu S, Nosov M, O’Flynn L, et al. Immunogenicity of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2012;16(9):2094–2103. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01509.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen LT, Hoang DM, Nguyen KT, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus duration and obesity alter the efficacy of autologously transplanted bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem/stromal cells. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2021;10(9):1266–1278. doi: 10.1002/sctm.20-0506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang L, Zhao S, Mao H, et al. Autologous bone marrow stem cell transplantation for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Chin Med J. 2011;124(22):3622–3628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu J, Wang Y, Gong H, et al. Long term effect and safety of Wharton’s jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells on type 2 diabetes. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12(3):1857–1866. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen P, Huang Q, Xu XJ, et al. 利拉鲁肽联合人脐带间充质干细胞治疗对2型糖尿病患者糖代谢及胰岛β细胞功能的作用 [The effect of liraglutide in combination with human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells treatment on glucose metabolism and β cell function in type 2 diabetes mellitus]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2016;55(5):349–354. Chinese. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2016.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiang R, Han Z, Zhuo G, et al. Transplantation of placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells in type 2 diabetes: a pilot study. Front Med. 2011;5(1):94–100. doi: 10.1007/s11684-011-0116-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhansali S, Dutta P, Kumar V, et al. Efficacy of autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell and mononuclear cell transplantation in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized placebo-controlled comparative study. Stem Cells Dev. 2017;26(7):471–481. doi: 10.1089/scd.2016.0275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leighton E, Sainsbury CA, Jones GC. A Practical Review of C-Peptide Testing in Diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2017;8(3):475–487. doi: 10.1007/s13300-017-0265-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherwani SI, Khan HA, Ekhzaimy A, et al. Significance of HbA1c test in diagnosis and prognosis of diabetic patients. Biomark Insights. 2016;11:BMI.S38440. doi: 10.4137/BMI.S38440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee M-Y, Huang J-C, Chen S-C, et al. Association of HbA1C variability and renal progression in patients with type 2 diabetes with chronic kidney disease stages 3–4. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(12):4116. doi: 10.3390/ijms19124116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berglund AK, Fortier LA, Antczak DF, et al. Immunoprivileged no more: measuring the immunogenicity of allogeneic adult mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8(1):288. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0742-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moassesfar S, Masharani U, Frassetto LA, et al. A comparative analysis of the safety, efficacy, and cost of islet versus pancreas transplantation in nonuremic patients with type 1 diabetes. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(2):518–526. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]