Abstract

Purpose

Many patients diagnosed with lymphoma are of working age. Cancer patients are known to have a higher risk of sick leave and disability pension, but this has only been delineated for certain subtypes of lymphoma. Therefore, this study aimed at investigating the overall risk of disability pension for all lymphoma subtypes and at quantifying return to work for patients with lymphoma in work before diagnosis.

Patients and Methods

Patients aged 18–60 years with lymphoma in complete remission (CR) diagnosed between 2000 and 2019 were included in the study. Using national registers, each patient was matched with five comparators from the general population with same sex, birth year, and level of Charlson Comorbidity Index. Risk of disability pension was calculated from 90 days after CR or end of treatment with competing events (death, retirement pension, early retirement pension, relapse for patients, or lymphoma diagnosis for comparators). Return to work for patients was calculated annually until 5 years after diagnosis for patients employed before diagnosis.

Results

In total, 4072 patients and 20,360 comparators were included. There was a significant increased risk of disability pension for patients with all types of lymphoma compared to the general population (5-year risk difference: 5.3 (95% confidence interval (CI): 4.4;6.2)). Patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma were more likely to get disability pension than patients with Hodgkin lymphoma (sex- and age-adjusted 10-year risk difference: 2.9 (95% CI: 0.3;5.5)). One year after diagnosis, 24.5% of the relapse-free patients were on sick leave. Return to work was highest 2 years after diagnosis (82.1%).

Conclusion

Patients with lymphoma across all subtypes have a significantly higher risk of disability pension. Return to work peaks at 2 years after diagnosis.

Keywords: lymphoma, disability pension, return to work

Introduction

Cancer patients in general are facing a risk of prolonged sick leave and early retirement.1,2 Thus, return to work rates for cancer patients are low and many patients have reduced income.3,4 Lymphoma is a heterogenous cancer. The median age at onset varies by subtype. Approximately one-third of patients diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) are below 60 years at diagnosis. For Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), the median age is even lower.5–7 As many patients with lymphoma are diagnosed early in adult life, return to work after lymphoma is important for at least two reasons: first, to reduce the negative impact of lymphoma on patients’ quality of life; second, to ease the economic burden of the disease for the patient and society alike.

Earlier studies have shown return to work rates of 85–90% 2 years after diagnosis among younger patients with lymphoma.8 However, for patients treated with more toxic treatments, the return-to-work rates are lower.9,10 The risk of disability pension has been found to be higher than the general population in selected subgroups of lymphoma.11,12

Patients with lymphoma have experienced improved survival rates in recent years.13,14 But some patients have persistent complications like treatment-related toxicity, which may influence their ability to work after treatment. Thus, patients with lymphoma are younger than most other cancer patients, their life expectancy has grown, and they have a risk of treatment-related toxicities which may impact return to work and risk of disability pension. However, to our knowledge, no study has examined the risk of disability pension for all subtypes of lymphoma combined.

The purpose of the present study was, firstly, to investigate the risk of disability pension among Danish patients with all types of lymphoma compared with the general population; secondly, to examine the impact of social and clinical factors on the risk of disability pension among patients with lymphoma; and, thirdly, to quantify the proportion of lymphoma survivors, holding a job at the time of diagnosis, who were able to return to work.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Patients were included from the Danish National Lymphoma Registry (LYFO). As all residents in Denmark have access to a tax-paid public healthcare system, all Danish patients with lymphoma are treated at public hospitals where registration in LYFO is mandatory. The register holds baseline information such as time of diagnosis, lymphoma subtype, stage, performance status, and localization of lymphoma as well as information on treatment, relapse, and survival. LYFO has been validated, and its coverage and completeness are high.15 Danish patients aged 18–60 years, diagnosed with lymphoma from January 1, 2000, to May 31, 2019, and who attained complete remission (CR) or CR unconfirmed (CRu) after first-line treatment were included. We only included patients aged ≤60 years to ensure sufficient time with possible affiliation to the labor market after diagnosis of lymphoma. Furthermore, patients should be alive, relapse free, and living in Denmark at the index date which was defined as 90 days after CR/CRu. Patients registered with lymphoma in the Danish Cancer Registry before 2000 or patients receiving disability pension, retirement pension, or early retirement before the index date were excluded. The included subtypes of lymphoma are outlined in Supplemental Table S1.

Each patient was matched with five Danish comparators without a history of lymphoma, disability pension, retirement pension, or early retirement. The comparators were randomly selected without replacement from the Danish Civil Registration System (CRS).16,17 Comparators were assigned the index date from the corresponding patient. Comparators were matched on sex, birth year, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) calculated 180 days prior to lymphoma diagnosis.18–20

Registers and Covariates

Information on both patients and matched comparators was collected from various registers. All residents in Denmark are registered with a unique civil registration number (CPR number), allowing linkage of registers on an individual level.

The DREAM database holds weekly information on all public transfer payments given to all Danish residents since 1991.21 All payment codes in DREAM were categorized as described in Supplemental Table S2. The date of disability, retirement, and early retirement pension was defined as the first day of the first week with a payment from the respective pension. The pre-lymphoma employment status was calculated between week 10 and week 18 before diagnosis. It was defined as the employment status occurring in at least five of the 9 weeks. The 9-week gap between diagnosis and evaluation of employment status was introduced, as symptoms of lymphoma could affect the ability to work in the weeks leading up to diagnosis.

The CCI was calculated based on information from The Danish National Patient Register (all diagnosis), The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register (dementia), and The National Prescription Registry (diabetes).22–26

Cohabiting status and education level were extracted the year before index date. Information on the highest completed education was found in Population’s Education Register (PER), and divided into four groups according to the ISCED11 levels (ISCED 0–2, 3, 5–6 and 7–8).27,28 ISCED level 4 was omitted as it does not exist in Denmark.

Equalized income was retrieved from The Income Statistics Register the year before diagnosis.29 Equalized income was calculated based on the total disposable income of the household and adjusted according to the OECD-modified equivalence scale, which is based on the number of adults and children in the household.30 Equalized income was then categorized into four groups according to the patients’ and the comparators’ age and the quartiles of the equalized income in five-year intervals (eg, 15–19 years, 20–24 years, etc) for the whole Danish population in the relevant year (1999–2018). The year- and age-specific quartiles for equalized income for the whole Danish population were obtained from Statistics Denmark (Supplemental Table S3).

Outcome

The primary endpoint was disability pension defined as a payment code for disability pension in DREAM. The secondary endpoint was return to work. Return to work was presented as proportions and with the Work Participation Score (WPS).31 In brief, WPS is the number of weeks being self-supporting (including state education grant, parental leave, and leave of absence) divided by the total number of weeks. WPS is presented in percentage, and a higher score equals higher participation in the labor market. WPS was calculated between the first and second year after diagnosis (52 weeks). Proportions were calculated only for patients and their matched comparators who held a job before receiving the lymphoma diagnosis. Only patients with a least one matched comparator holding a job were included in this analysis. Patients and comparators receiving permanent social benefits (flexible job or pension regardless of type) and those who were not alive, had emigrated, or relapsed within the first 2 years after diagnosis were excluded.

Statistical Analysis

Follow-up was measured from the index date until event (disability pension), competing event (death, retirement pension, early retirement pension, relapse for patients, or lymphoma diagnosis for comparators), or censoring (end of follow-up on December 31, 2021, or emigration).

The cumulative risk of disability pension was calculated with the above mentioned competing events using the Aalen–Johansen estimator, and differences between groups were tested using Gray’s test.32,33

Crude differences in the risk of disability pension were computed for patients with lymphoma and comparators at 5 and 10 years using a pseudo-observation approach without violation the original matching.34,35 For patients with lymphoma, crude and sex- and age-adjusted (18–30; 31–40; 41–50 and 51–60 years) risk differences in subgroups were calculated using the same approach.

Return to work was calculated annually until 5 years and at 10 years after the date of diagnosis for patients in work before diagnosis. The calculation was done over 9 weeks with the week of anniversary centralized. Patients were excluded from this analysis at the time of emigration, relapse, death, or censoring. Employment status was defined as the status present at least five of the 9 weeks, except if one of the 9 weeks was flexible job, disability pension, early retirement pension, or retirement pension (in ranked order), then this status defined the employment status. The WPS analyses were calculated for all patients with lymphoma and in subgroups. A sensitivity analysis with the exclusion of all relapses within the first 3 years was done to ensure that WPS was not affected by delayed diagnosis of relapse.

Statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Gary, North Carolina, USA) and R version 4.0.3 (R foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The study was registered in the research registry of the North Denmark Region (2021–217) and approved by the Danish Patient Safety Authority (3–3013-2536/1).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

A total of 4072 patients with lymphoma and 20,360 matched comparators were included (median age: 47 years; 58.6% males). Median follow-up was 9.8 years for patients and 10.1 years for comparators. The median time from diagnosis to index date was 41.7 weeks (IQR: 34.6–48.9 weeks). Thirty patients (0.74%) had more than 3 years between diagnosis and index date. Patients’ and comparators’ baseline characteristics are described in Table 1 and Supplemental Table S4.

Table 1.

Baseline and Clinical Characteristics of Patients and Matched Comparators

| Lymphoma (n=4072) | Comparators (n=20,360) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 47 (18–60) | 47 (17–60) |

| Age group, n (%) | ||

| 18–30 | 753 (18.5) | 3792 (18.6) |

| 31–40 | 704 (17.3) | 3464 (17.0) |

| 41–50 | 1000 (24.6) | 5030 (24.7) |

| 51–60 | 1615 (39.7) | 8074 (39.7) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 2385 (58.6) | 11,925 (58.6) |

| Female | 1687 (41.4) | 8435 (41.4) |

| Cohabiting status, n (%) | ||

| Living alone/unknown | 1169 (28.7) | 6060 (29.8) |

| Living with partner | 2903 (71.3) | 14,300 (70.2) |

| Education level (ISCED), n (%) | ||

| ISCED 0–2 | 956 (23.5) | 4572 (22.5) |

| ISCED 3 | 1809 (44.4) | 9208 (45.2) |

| ISCED 5–6 | 899 (22.1) | 4274 (21.0) |

| ISCED 7–8 | 360 (8.8) | 1735 (8.5) |

| Unknown | 48 (1.2) | 571 (2.8) |

| Equalized income, quartiles, n (%) | ||

| Lowest | 864 (21.2) | 4401 (21.6) |

| Second lowest | 1012 (24.9) | 4981 (24.5) |

| Second highest | 1058 (26.0) | 5194 (25.5) |

| Highest | 1116 (27.4) | 5428 (26.7) |

| Unknown | 22 (0.5) | 356 (1.7) |

| Country of origin, n (%) | ||

| Denmark | 3689 (90.6) | 18,305 (89.9) |

| Western country | 158 (3.9) | 842 (4.1) |

| Non-western country | 225 (5.5) | 1206 (5.9) |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 7 (0.0) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||

| Workinga | 3423 (84.1) | 17,245 (84.7) |

| Unemployed | 348 (8.5) | 1775 (8.7) |

| Sick leave | 173 (4.2) | 594 (2.9) |

| Flexible job | 114 (2.8) | 505 (2.5) |

| Unknown | 14 (0.3) | 241 (1.2) |

| Long-term sickness,b n (%) | ||

| No | 3348 (82.2) | 18,770 (92.2) |

| Yes | 724 (17.8) | 1590 (7.8) |

| CCI before diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| 0-1 | 3744 (91.9) | 18,720 (91.9) |

| 2 | 207 (5.1) | 1035 (5.1) |

| ≥3 | 121 (3.0) | 605 (3.0) |

Notes: aWorking group includes students, parental leave and leave of absence. bFour or more consecutive weeks within the last year before diagnosis or similar date for comparators.

Abbreviations: ISCED, International Standard Classification of Education; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index.

Risk of Disability Pension

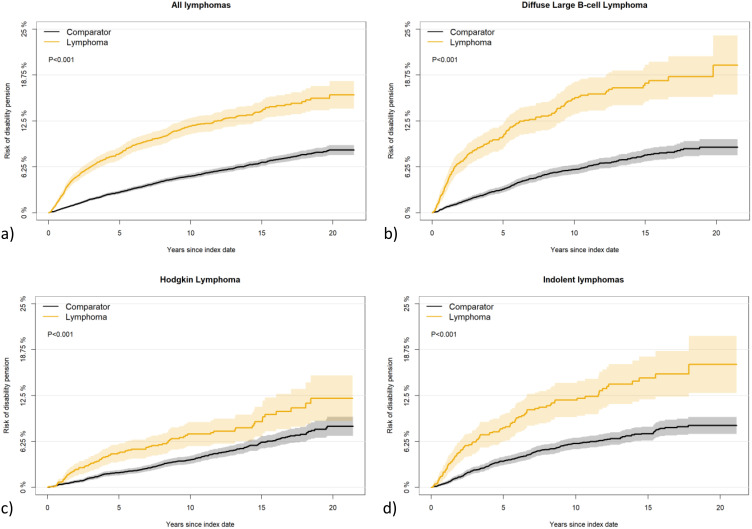

Patients with lymphoma had a significantly higher risk of disability pension than comparators (Figure 1A) with a 5-year cumulative risk of 8.1% (95% CI: 7.2;8.9%) and 2.8% (95% CI: 2.5;3.0%), respectively, 5-year risk difference (RD): 5.3 (95% CI: 4.4;6.2). The corresponding cumulative risks for 10 years were 11.8% (95% CI: 10.7;12.9%) and 5.0% (95% CI: 4.6;5.3%), respectively, 10-year RD: 6.8 (95% CI: 5.7;8.0).

Figure 1.

Cumulative risk of disability pension for patients with lymphoma and the matched comparators. (A) All lymphoma, (B) Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, (C) Hodgkin lymphoma, (D) Indolent lymphoma.

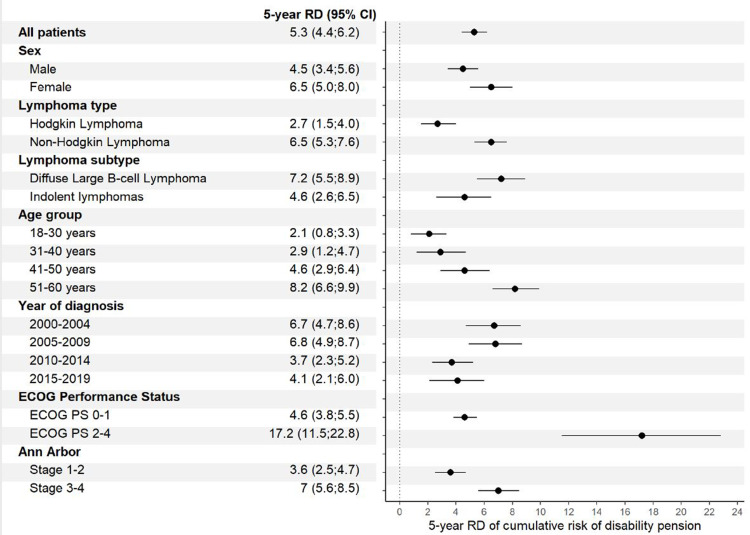

The risk of disability pension was significantly increased at 5 and 10 years compared with comparators for all patients with lymphoma regardless of sex, HL/NHL, lymphoma subtype, age, year of diagnosis, performance status, and Ann Arbor stage (Figures 1B-D, 2, Supplemental Figure S1, and Supplemental Figure S2).

Figure 2.

5-year absolute crude risk differences of disability pension in subgroups between patients with lymphoma and comparators.

Abbreviations: RD, risk differences; CI, confidence interval; ECOG PS, ECOG Performance Status.

Risk Factors for Disability Pension

Patients with NHL had a higher risk of disability pension compared to patients with HL 5 years after index (crude RD 4.9 (95% CI: 3.3;6.5)). RD adjusted for sex and age was 1.9 (95% CI: 0.0;3.8). Ten years after index, the crude RD was 6.5 (95% CI: 4.4;8.7) and the RD adjusted for sex and age was 2.9 (95% CI: 0.3;5.5). A significantly higher five-year risk of disability pension was associated with female sex, higher age, diagnosis in the earliest calendar periods, living alone, lower education level, lower equalized income, sick leave within the year before diagnosis, higher CCI, higher Ann Arbor stage, and poorer ECOG Performance Status (Table 2). The risk for the above-mentioned groups was higher both in the crude and the sex- and age-adjusted analysis. Results were similar for 10-year RD except for calendar time of diagnosis (Supplemental Table S5).

Table 2.

Risk of Disability Pension, Risk Difference Between Subgroups (Crude and Adjusted for Sex and Age) for Patients with Lymphoma 5 Years After Index Date with 95% Confidence Interval

| Risk (%) | RD (Crude) | RD (Adjusted) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 7.0 (5.9;8.0) | 0 | |

| Female | 9.5 (8.1;11.0) | 2.5 (0.8;4.3) | |

| Age at diagnosis | |||

| 18–30 years | 2.7 (1.5;3.9) | 0 | |

| 31–40 years | 5.3 (3.6;7.0) | 2.5 (0.5;4.6) | |

| 41–50 years | 7.7 (6.0;9.4) | 5.0 (2.9;7.1) | |

| 51–60 years | 11.9 (10.3;13.6) | 9.2 (7.2;11.2) | |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 2000–2004 | 9.9 (8.1;11.8) | 0 | 0 |

| 2005–2009 | 9.7 (7.9;11.5) | −0.2 (−2.9;2.5) | −0.3 (−2.9;2.4) |

| 2010–2014 | 5.5 (4.1;6.9) | −4.5 (−6.9;-2.1) | −4.2 (−6.6;-1.8) |

| 2015–2019 | 7.3 (5.4;9.2) | −2.7 (−5.2;-0.3) | −2.5 (−5.0;-0.1) |

| Cohabiting status | |||

| Living alone | 10.6 (8.7;12.4) | 0 | 0 |

| Living with partner | 7.0 (6.1;8.0) | −3.5 (−5.6;-1.5) | −4.9 (−6.9;-2.8) |

| Education level | |||

| ISCED 0–2 | 12.9 (10.8;15.1) | 0 | 0 |

| ISCED 3 | 7.3 (6.1;8.5) | −5.7 (−8.2;-3.2) | −5.4 (−7.9;-2.9) |

| ISCED 5–6 | 5.1 (3.6;6.6) | −7.8 (−10.5;-5.2) | −8.2 (−10.8;-5.6) |

| ISCED 7–8 | 3.3 (1.4;5.2) | −9.7 (−12.6;-6.8) | −9.5 (−12.4;-6.6) |

| Equalized income | |||

| Lowest | 15.6 (13.1;18.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Second lowest | 9.0 (7.2;10.8) | −6.5 (−9.5;-3.4) | −7.3 (−10.3;-4.3) |

| Second highest | 6.0 (4.5;7.5) | −9.5 (−12.4;-6.6) | −10.2 (−13.1;-7.4) |

| Highest | 3.2 (2.2;4.3) | −12.3 (−15.0;-9.6) | −12.8 (−15.5;-10.1) |

| Consecutive sick leave min. 4 weeks within the year before diagnosis | |||

| No sick leave | 5.8 (5.0;6.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Sick leave | 18.3 (15.4;21.1) | 12.4 (9.5;15.4) | 11.5 (8.6;14.5) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |||

| 0-1 | 7.4 (6.5;8.2) | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 15.3 (10.3;20.3) | 8.0 (2.9;13.0) | 6.0 (1.0;11.0) |

| ≥ 3 | 16.7 (9.8;23.6) | 9.1 (2.3;16.0) | 8.1 (1.1;15.1) |

| Lymphoma type | |||

| Hodgkin Lymphoma | 4.7 (3.5;5.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma | 9.6 (8.5;10.7) | 4.9 (3.3;6.5) | 1.9 (0.0;3.8) |

| Lymphoma subtype | |||

| DLBCL | 10.4 (8.7;12.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Nodular lymphocyte predominant | 3.9 (0.0;8.3) | −6.4 (−11.1;-1.7) | −3.3 (−8.0;1.4) |

| Classical Hodgkin lymphoma | 4.7 (3.5;6.0) | −5.7 (−7.7;-3.6) | −2.5 (−4.9;-0.2) |

| Indolent lymphomas | 8.1 (6.3;10.0) | −2.3 (−4.8;0.2) | −3.0 (−5.6;-0.5) |

| Intermediate lymphomas | 8.7 (4.0;13.5) | −1.7 (−6.7;3.3) | −2.8 (−7.9;2.4) |

| Aggressive T-cell lymphomas | 13.3 (8.8;17.8) | 2.9 (−2.0;7.7) | 3.9 (−0.9;8.7) |

| Other aggressive B-cell lymphomas | 5.1 (1.4;8.7) | −5.4 (−9.4;-1.3) | −2.0 (−6.1;2.2) |

| Other | 10.9 (4.1;17.6) | 0.3 (−6.5;7.2) | 0.6 (−6.2;7.5) |

| Ann Arbor | |||

| 1–2 | 6.2 (5.2;7.3) | 0 | 0 |

| 3–4 | 10.0 (8.6;11.4) | 3.8 (2.0;5.5) | 2.9 (1.2;4.7) |

| ECOG Performance Status | |||

| 0-1 | 7.4 (6.5;8.2) | 0 | 0 |

| 2–4 | 20.1 (14.6;25.6) | 12.8 (7.1;18.5) | 12.3 (6.7;17.9) |

Abbreviations: RD, risk difference; ISCED, International Standard Classification of Education; DLBCL, diffuse large B cell lymphoma.

Return to Work After Lymphoma

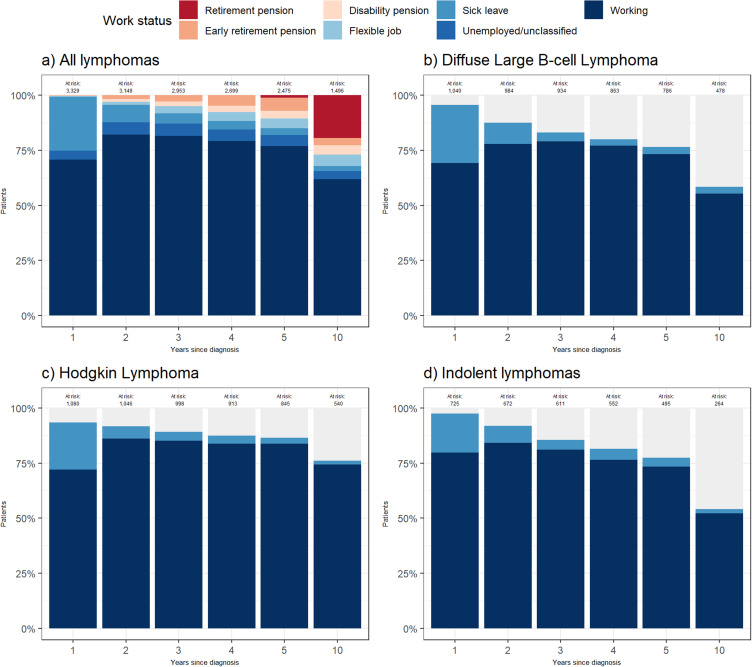

In total, 3423 (84.1%) patients with lymphoma (median age: 47 years) were employed before diagnosis. One year after diagnosis, 70.8% of the relapse-free patients, employed before diagnosis had returned to work and were holding a job (Figure 3A). Two years after diagnosis, the working group had increased to 82.1%. Hereafter, the percentage fell to 77% and 61.8% five and ten years after diagnosis. The proportion of sick leave was highest in the first year (24.5%) and lowest 10 years after diagnosis (2.3%). This pattern was consistent across the three major lymphoma subtypes (Figure 3B-D).

Figure 3.

Work status 1–5 and 10 years after diagnosis for patients with lymphoma in work before diagnosis and in live, not emigrated, censored and without relapse. Unclassified patients comprise <5 patients each year. (A) All lymphoma, (B) Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, (C) Hodgkin Lymphoma, (D) Indolent lymphoma. Due to small subgroups, only information on “working” and “sick leave” is stated for (B-D).

In the analysis of WPS, 3020 patients with lymphoma and 12,561 of their matched comparators met the inclusion criteria. The average patient with lymphoma was self-supporting 42 weeks out of 52 weeks between the first and the second year after diagnosis, corresponding to a mean WPS of 81.4%. The corresponding average ability of self-support was 49 weeks for comparators (mean WPS of 93.4%). The WPS for subgroups is shown in Table 3. The sensitivity analysis with exclusion of all relapses within the first 3 years revealed no changes in WPS.

Table 3.

Work Participation Score (WPS) Between 1 and 2 Years After Diagnosis for Patients with Lymphoma and Comparators Holding a Job Before Diagnosis

| Lymphoma | Comparator | |

|---|---|---|

| All | ||

| Patients (n) | 3020 | 12,561 |

| WPS (%) | 81.4 | 93.4 |

| Number of weeks | 42 | 49 |

| DLBCL | ||

| Patients (n) | 919 | 3817 |

| WPS (%) | 79.9 | 93.8 |

| Number of weeks | 42 | 49 |

| Indolent lymphomas | ||

| Patients (n) | 644 | 2661 |

| WPS (%) | 85.6 | 93.4 |

| Number of weeks | 45 | 49 |

| NHL | ||

| Patients (n) | 1991 | 8285 |

| WPS (%) | 80.7 | 93.7 |

| Number of weeks | 42 | 49 |

| HL | ||

| Patients (n) | 1029 | 4276 |

| WPS (%) | 82.8 | 92.9 |

| Number of weeks | 43 | 48 |

Abbreviations: DLBCL, diffuse large B cell lymphoma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; HL, Hodgkin lymphoma.

Discussion

This national cohort study reports the risk of disability pension across all subtypes of lymphoma. Within the period of 2000–2021, there was a significant higher risk of disability pension among patients with lymphoma compared with the general population with a 5-year risk difference of 5.3 (95% CI: 4.4;6.2), and a 10-year risk difference of 6.8 (95% CI: 5.7;8.0).

Our results regarding Hodgkin lymphoma are similar to results from earlier studies from Denmark and Sweden.11,12 Data on non-Hodgkin lymphoma as a collective group are however sparse. Kiserud et al investigated the risk of disability pension among lymphoma patients treated with high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation (HDT-ASCT), and found the cumulative risk to be 19% after a mean follow-up of 12.4 years.36 This is higher than our findings and could be explained by the highly toxic treatment given to all patients in the study by Kiserud et al. In contrast, less than 8% of our patients were treated with HDT-ASCT. On the contrary, Taskila et al found no difference in work ability (defined as a score 0–10 compared to with their lifetime best work ability) among cancer survivors and their referents.37 The study did, however, include different types of cancer (breast, testicular, prostate, and lymphoma), and it only included patients with favorable prognosis, ie, no advanced stage.

Disability pension can be granted to all citizens with a permanently reduced capacity to work in Denmark. Some risk factors for disability pension are well known, eg, female sex, higher age, living alone, long-term illness, low level of education, unskilled work, and receipt of welfare payments.38–41 As anticipated, these factors, along with high-stage disease and low physical well-being at diagnosis, were also associated with an increased risk of disability pension among patents with lymphoma in this study. This being so, patients with lymphoma had the same risk factors for becoming recipients of disability pension as the general population and are therefore neither more difficult nor easier to identify and hence pose no extra follow-up requirements in the public social security system.

When comparing the risk of disability pension for NHL patients to the risk for HL patients, there was a sex- and age-adjusted RD of 1.9 (95% CI: 0.0;3.8) and 2.9 (95% CI: 0.3;5.5) after 5 and 10 years, respectively. This could be explained by the higher disease stage and greater use of HDT-ASCT within the group of NHL patients. Another explanation for this could be a difference in life situation, when diagnosed with lymphoma. HL patients are often younger and may not have chosen education or found a job yet. Therefore, they might be more prone to adjust their work life. Whereas NHL patients are older and probably more locked in their work life leaving disability pension to be a more favorable solution.

The sex- and age-adjusted 5-year RD decreased for patients diagnosed more recently. This may be due to a structural change in the Danish legislation in 2013 reducing the possibility to be granted disability pension, especially for citizens below the age of 40 years. Pedersen et al, who investigated the risk of disability pension before and after 2013 for cancer patients and comparators, found similar results.42 Another explanation could be the advances in both lymphoma treatment and supportive care reducing the risk of long-term complications that could affect the work ability.

Return to work increased up to the second year after diagnosis, where it peaked at 82.1%. Afterwards, it decreased to 77% at 5 years after diagnosis. Leuteritz et al found return to work among young adult HL and NHL survivors (aged 18–39 years) to be higher than in the present study.8 On the contrary, Hartung et al found lower return to work in a group of patients with all types of hematological cancer.43 However, only half of the patients were diagnosed with lymphoma by Hartung et al, and type of hematological cancer has been shown to affect the ability to return to work.3

The work participation score (WPS) in the present cohort was found to be 81.4% between 1 and 2 years after diagnosis. To our knowledge, no other study has investigated WPS after lymphoma. Pedersen et al investigated WPS after colon and rectal cancer.44 They found the WPS to be lower (75.97% and 70.23% 2 years after colon and rectal cancer, respectively). This could be due to difference in cancer types and a higher proportion of patients above 50 years in the study by Pedersen et al. The last explanation is underlined by a difference in the WPS for comparators, in the study by Pedersen et al being 89.20% (colon cancer) and 89.70% (rectal cancer), and in the present study being 93.4%.

This study holds several strengths. The use of validated nation-wide registers with high coverage ensures that almost all patients with lymphoma in Denmark are included, reducing the risk of selection- and information bias. Another strength is the long follow-up time with a median at 9.8 years for patients and 10.1 years for comparators. Combined with the low grade of missing values in the registers, and the high number of included patients, the present study is made with valid and precise data and has long follow-up.

However, the use of register data is also a limitation. The DREAM register does not include the cause of sick leave or disability pension. Therefore, it was not possible to distinguish between physical and mental causes. Furthermore, it cannot be precluded that a part of the elevated risk of disability pension can be related to other factors than the lymphoma. However, other known risk factors for disability pension are well balanced between patients and comparators in this study. Knowing what deprive the patients their ability to work is the first step towards helping them overcome the problems. This may help the patients keep their affiliation to the labor market and thereby ensuring their economy and maybe also increasing their quality of life. Therefore, it would be relevant to do a retrospective or prospective study with patient reported outcome-data on work-life and quality of life.

Another limitation is the unreported numbers on short-term sick leave. In Denmark, the work employer must pay for the first part of the sick leave for an employee. If the sick leave is longer than this period, the whole sick leave will be registered in the DREAM database. But short-term sick leaves less than the part the employer must pay is not registered. The period that the employer must pay has increased from 14 to 30 days during the study period. Therefore, there is a possibility that the amount of sick leave, both before the lymphoma diagnosis and during the follow-up, have been underreported if patients were on short-term sick leaves.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study found a significant higher risk of disability pension among patients with lymphoma compared with the general population. Further research is needed to investigate the cause of this increased risk. The risk factors for disability pension among patients with lymphoma did not differ from the risk factors known from other groups. Finally, the proportion of return to work was highest 2 years after diagnosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Andreas Kiesbye Øvlisen and Peter Enemark Lund for help with data management in SAS, and all the clinical staff who provided data for Danish National Lymphoma Registry (LYFO).

Funding Statement

The study is supported by Dagmar Marshalls Foundation (E.F.M), Master Carpenter Jørgen Holm and wife Elisa born Hansen’s memorial trust (E.F.M), the Karen Elise Jensen Foundation (L.H.J), Gilead Science Denmark (J.B) and the Danish Cancer Society (T.C.E-G, J.B). No sponsors have been involved in any part of the study or its publication.

Disclosure

E.F.M.: Grants from Dagmar Marshalls Foundation, grants from Master Carpenter Jørgen Holm and wife Elisa born Hansen’s memorial trust, during the conduct of the study.

L.H.J.: Lecture fee from Roche (2021)

J.B.: Research funding from Gilead Sciences Denmark

J.M.J.: Consulting: Gilead, Novartis, Roche, Incyte, BMS, Orion

M.R.C.: Consulting, speaker fee or advisory role: AbbVie, Janssen, Genmab, Incyte, Nordea

T.S.L.: Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis, Gilead; Research Funding: Genentech

A.O.G.: Lecture fee from Roche (2022)

P.B.: Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche, Incyte, Novartis, Gilead

T.C.E-G.: former employee by Roche; speakers fee from AbbVie (2021)

The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Torp S, Nielsen RA, Gudbergsson SB, Fosså SD, Dahl AA. Sick leave patterns among 5-year cancer survivors: a registry-based retrospective cohort study. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(3):315–323. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0228-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlsen K, Oksbjerg Dalton S, Frederiksen K, Johansen C, Diderichsen F. Cancer and the risk for taking early retirement pension: a Danish cohort study. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36(2):117–125. doi: 10.1177/1403494807085192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horsboel TA, Nielsen CV, Nielsen B, Jensen C, Andersen NT, de Thurah A. Type of hematological malignancy is crucial for the return to work prognosis: a register-based cohort study. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(4):614–623. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0300-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Syse A, Tretli S, Kravdal Ø. Cancer’s impact on employment and earnings-a population-based study from Norway. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2(3):149–158. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0053-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shankland KR, Armitage JO, Hancock BW. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet. 2012;380(9844):848–857. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60605-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roman E, Smith AG. Epidemiology of lymphomas. Histopathology. 2011;58(1):4–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03696.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis WD, Lilly S, Jones KL. Lymphoma: diagnosis and Treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(1):34–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leuteritz K, Friedrich M, Sender A, et al. Return to work and employment situation of young adult cancer survivors: results from the Adolescent and Young Adult-Leipzig Study. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2021;10(2):226–233. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2020.0055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiemann G, Pertz M, Kowalski T, Seidel S, Schlegel U, Thoma P. Complete response to therapy: why do primary central nervous system lymphoma patients not return to work? J Neurooncol. 2020;149(1):171–179. doi: 10.1007/s11060-020-03587-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arboe B, Olsen MH, Goerloev JS, et al. Return to work for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and transformed indolent lymphoma undergoing autologous stem cell transplantation. Clin Epidemiol. 2017;9:321–329. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S134603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horsboel TA, Nielsen CV, Andersen NT, Nielsen B, De Thurah A. Risk of disability pension for patients diagnosed with haematological malignancies: a register-based cohort study. Acta Oncol. 2014;53(6):724–734. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.875625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glimelius I, Ekberg S, Linderoth J, et al. Sick leave and disability pension in Hodgkin lymphoma survivors by stage, treatment, and follow-up time—a population-based comparative study. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(4):599–609. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0436-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(4):220–241. doi: 10.3322/caac.21149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(5):363–385. doi: 10.3322/caac.21565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arboe B, El-Galaly TC, Clausen MR, et al. The Danish National Lymphoma Registry: coverage and Data Quality. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):22–25. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pedersen CB, Gøtzsche H, Møller JO, Mortensen PB. The Danish Civil Registration System. A cohort of eight million persons. Dan Med Bull. 2006;53(4):441–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, Mackenzie CR, New A. Method of classifying prognostic in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in. Med Care. 2005;43:11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sundararajan V, Quan H, Halfan P, et al. Cross-national comparative performance of three versions of the ICD-10 Charlson index. Med Care. 2007;45(12):1210–1215. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181484347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hjollund NH, Larsen FB, Andersen JH. Register-based follow-up of social benefits and other transfer payments: accuracy and degree of completeness in a Danish interdepartmental administrative database compared with a population-based survey. Scand J Public Health. 2007;35(5):497–502. doi: 10.1080/14034940701271882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):30–33. doi: 10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB. The Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):54–57. doi: 10.1177/1403494810395825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallach Kildemoes H, Toft Sørensen H, Hallas J. The Danish national prescription registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7):38–41. doi: 10.1177/1403494810394717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pottegård A, Schmidt SAJ, Wallach-Kildemoes H, Sørensen HT, Hallas J, Schmidt M. Data Resource Profile: the Danish National Prescription Registry. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):798–798f. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyw213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen VM, Rasmussen AW. Danish education registers. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):91–94. doi: 10.1177/1403494810394715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.UNESCO Institute for Statistics. International Standard Classification of Education, ISCED 2011; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baadsgaard M, Quitzau J. Danish registers on personal income and transfer payments. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7_suppl):103–105. doi: 10.1177/1403494811405098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.OECD. What are equivalence scales? OECD Proj Income Distrib Poverty. 2011;1-2:548. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Biering K, Hjøllund NH, Lund T. Methods in measuring return to work: a comparison of measures of return to work following treatment of coronary heart disease. J Occup Rehabil. 2013;23(3):400–405. doi: 10.1007/s10926-012-9405-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Putter H, Fiocco M, Geskus RB. Tutorial in biostatistics: competing risks and multi-state models. Stat Med. 2007;26(11):2389–2430. doi: 10.1002/sim.2712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gray RJA. Class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16(3):1141–1154. doi: 10.1214/aos/1176350951 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andersen PK, Pohar Perme M. Pseudo-observations in survival analysis. Stat Methods Med Res. 2010;19(1):71–99. doi: 10.1177/0962280209105020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klein JP, Gerster M, Andersen PK, Tarima S, Perme MP. SAS and R functions to compute pseudo-values for censored data regression. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2008;89(3):289–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2007.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiserud CE, Fagerli UM, Smeland KB, et al. Pattern of employment and associated factors in long-term lymphoma survivors 10 years after high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(5):547–553. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2015.1125015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taskila T, Martikainen R, Hietanen P, Lindbohm ML. Comparative study of work ability between cancer survivors and their referents. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(5):914–920. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brun C, Bøggild H, Eshøj P. Socioeconomic risk indicators for disability pension within the Danish workforce. A registry-based cohort study of the period 1994-1998. Ugeskr Laeger. 2003;35:3315–3319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krokstad S, Johnsen R, Westin S. Social determinants of disability pension: a 10-year follow-up of 62 000 people in a Norwegian county population. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(6):1183–1191. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.6.1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bruusgaard D, Smeby L, Claussen B. Education and disability pension: a stronger association than previously found. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38(7):686–690. doi: 10.1177/1403494810378916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karlsson N, Borg K, Carstensen J, Hensing G, Alexanderson K. Risk of disability pension in relation to gender and age in a Swedish county; a 12-year population based, prospective cohort study. Work. 2006;27(2):173–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pedersen P, Aagesen M, Tang LH, Bruun NH, Zwisler AD, Stapelfeldt CM. Risk of being granted disability pension among incident cancer patients before and after a structural pension reform: a Danish population-based, matched cohort study. Scand J Work Environ Heal. 2020;46(4):382–391. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.3883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hartung TJ, Sautier LP, Scherwath A, et al. Return to work in patients with hematological cancers 1 year after treatment: a prospective longitudinal study. Oncol Res Treat. 2018;41(11):697–701. doi: 10.1159/000491589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pedersen P, Laurberg S, Andersen NT, et al. Differences in work participation between incident colon and rectal cancer patients—a 10-year follow-up study with matched controls. J Cancer Surviv. 2021;16:73–85. doi: 10.1007/s11764-021-01005-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]