Abstract

The development of medical products that can delay or prevent progression to stage 3 type 1 diabetes faces many challenges. Of note, optimising patient selection for type 1 diabetes prevention clinical trials is hindered by significant patient heterogeneity and a lack of characterisation of the time-varying probability of progression to stage 3 type 1 diabetes in individuals positive for two or more islet autoantibodies. To meet these needs, the Critical Path Institute’s Type 1 Diabetes Consortium was launched in 2017 as a pre-competitive public–private partnership between stakeholders from the pharmaceutical industry, patient advocacy groups, philanthropic organisations, clinical researchers, the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration. The Type 1 Diabetes Consortium acquired and aggregated data from three longitudinal observational studies, Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY), Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY) and TrialNet Pathway to Prevention (TN01), and used analysis subsets of these data to support the model-based qualification of islet autoantibodies as enrichment biomarkers for patient selection in type 1 diabetes prevention trials, including registration studies. The Type 1 Diabetes Consortium has now received a qualification opinion from the European Medicines Agency for the use of these biomarkers, a major success for the field of type 1 diabetes. This endorsement will improve product developers’ ability to design clinical trials of agents intended to prevent or delay type 1 diabetes that are reduced in size and/or length, while being adequately powered.

Keywords: DAISY, Data, Data sharing, Drug development tools, Islet autoantibodies, Public–private-partnerships, Regulatory science, Review, TEDDY, TrialNet, Type 1 diabetes

Introduction

To date, no disease-modifying therapies have been approved for use in type 1 diabetes. As the global incidence and prevalence of type 1 diabetes increase, there is a growing unmet medical need for therapies that target the underlying disease process [1]. In 2015, to help provide a framework for the development of such therapies, JDRF, the Endocrine Society and the ADA published a foundational staging classification from presymptomatic type 1 diabetes to symptomatic disease [2]. The staging classification established three distinct stages of disease: the presence of two or more islet autoantibodies (AAs) in patients who are normoglycaemic (stage 1); the presence of two or more islet AAs and glucose intolerance or dysglycaemia (stage 2); and clinical manifestation of type 1 diabetes, with typical signs and symptoms of disease (e.g. polyuria, polydipsia, weight loss and fatigue) and dysglycaemia meeting clinical criteria for diabetes (stage 3). A primary intent of this construct is to enhance the clinical development of medical products that prevent, delay or modify the course of type 1 diabetes by establishing patient risk profiles that allow for better patient stratification in clinical trials.

Despite the recent successes seen with teplizumab, the path to develop a new product remains costly, lengthy and high risk for developers [3, 4]. The type 1 diabetes community must continue to look for opportunities to improve the efficiency and likelihood of success of type 1 diabetes prevention development programmes. One proven method for accelerating drug development is the use of drug development tools (DDTs) that help inform regulatory decision making [5–8]. While many types of DDTs exist (e.g. biomarkers, clinical outcomes assessments and in silico models), all aim to streamline the development process.

DDTs also provide several strategic advantages when considering a pharmaceutical organisation’s allocation of resources. The optimised development landscape provided by DDTs increases individual products’ competitiveness for internal resources. Further, because a lack of historical successes in type 1 diabetes product development can affect an organisation’s decision making, DDTs designed for use in type 1 diabetes can improve the likelihood that organisations will invest in this disease. Endorsement of a DDT by the major regulatory agencies (e.g. the European Medicines Agency [EMA] and the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA]) improves the risk–benefit assessment when considering the overall prospect of success in a therapeutic area, thus providing additional confidence for sponsors. The development and regulatory endorsement of DDTs that specifically target earlier stages of intervention in type 1 diabetes will help deliver new agents that prevent or delay clinical disease.

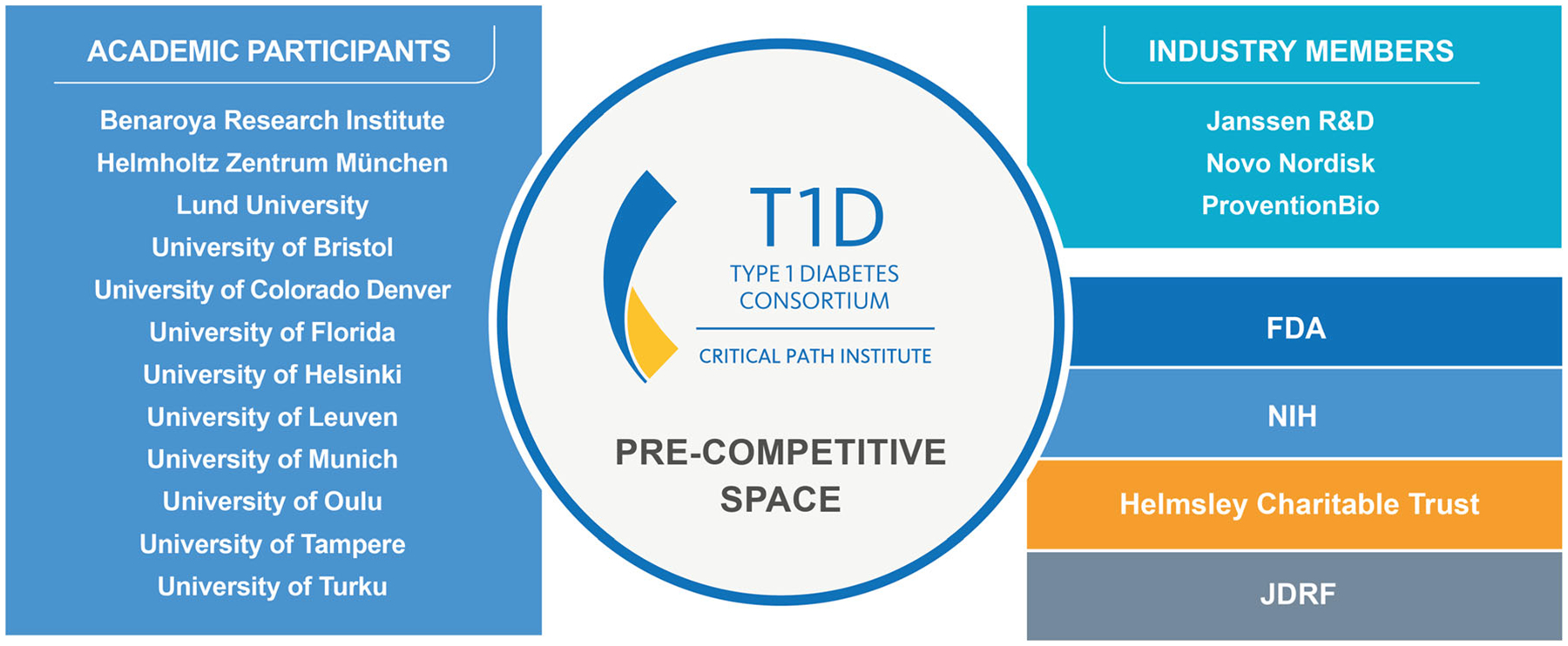

In 2017, the Critical Path Institute’s (C-Path) Type 1 Diabetes Consortium (T1DC) was founded as a pre-competitive public–private partnership between stakeholders from the pharmaceutical industry, patient advocacy groups, philanthropic organisations, clinical research groups, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the FDA (Fig. 1). The T1DC is managed and operated by C-Path, an independent non-profit organisation with a mission to support collaborations that improve the medical product development process. The T1DC focused first on obtaining regulatory endorsement from the FDA and EMA of islet AAs as clinical trial enrichment biomarkers. The general process for triangulating potential drug development needs, solutions and data sources to identify a specific and targeted DDT profile is described in Fig. 2, 3, 4. Following this exercise, a clear data acquisition and regulatory endorsement strategy was developed.

Fig. 1.

Public, private and regulatory members and participant organisations of the T1DC.

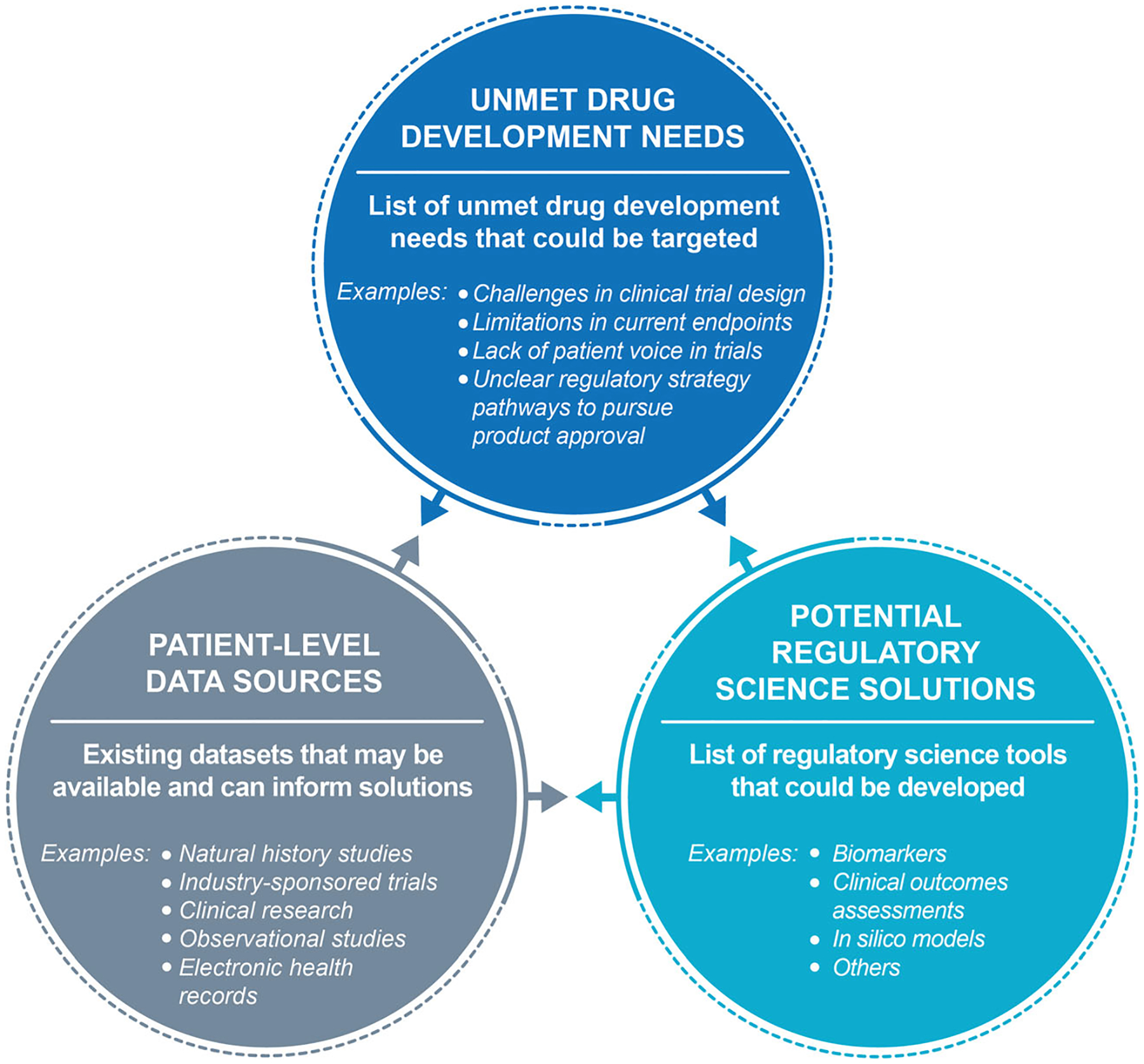

Fig. 2.

The process to identify a drug development solution begins with a generalised landscape assessment. First, an initial broad scoping exercise is performed to identify existing unmet drug development needs, potential regulatory science solutions and patient-level data sources that could inform the consortium activities.

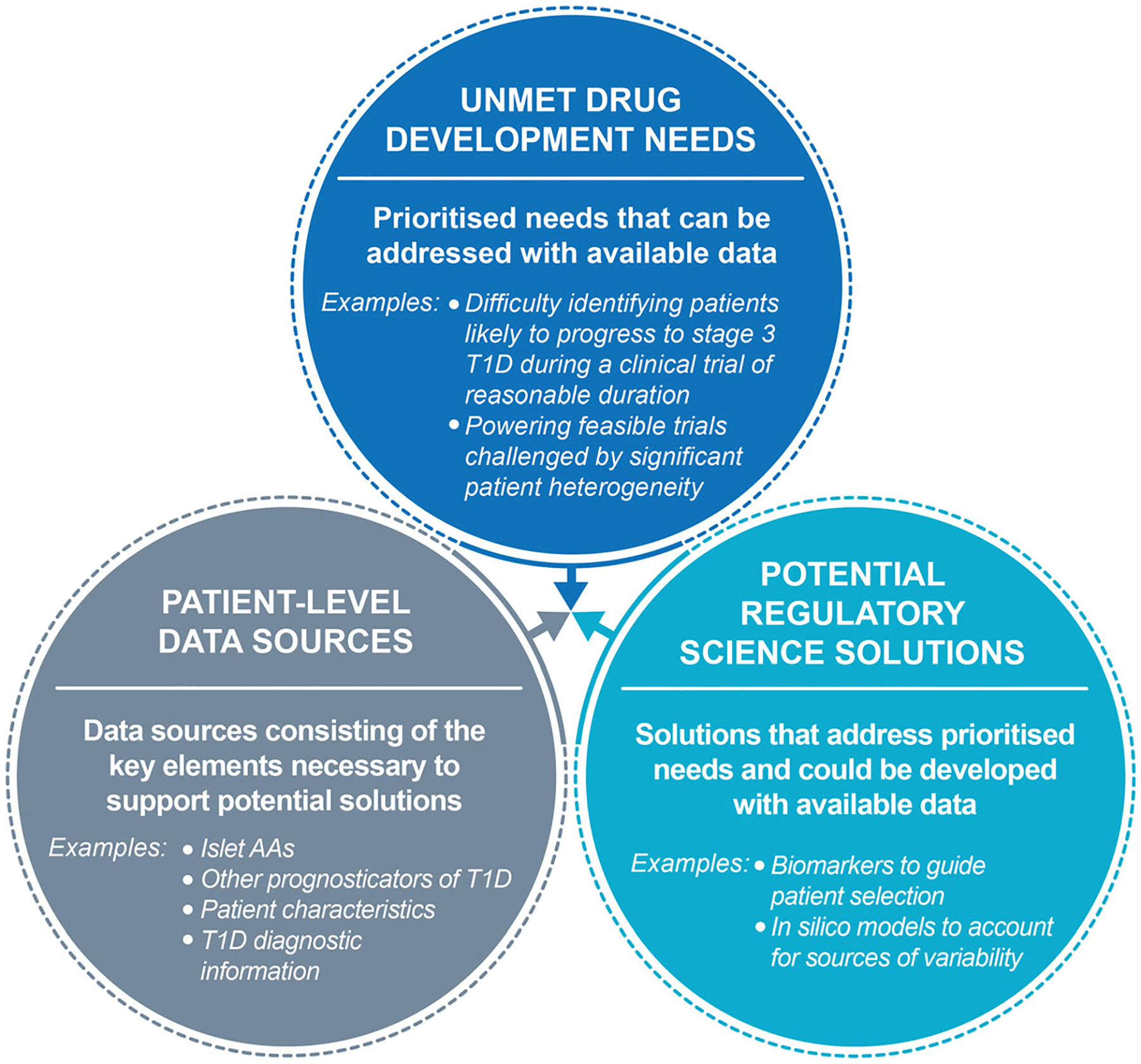

Fig. 3.

The process to identify a drug development solution continues with preliminary feasibility assessments of high potential solutions. The consortium refines and prioritises unmet needs, potential solutions and relevant sources of data based on considerations from each area to identify a clear target tool profile. T1D, type 1 diabetes.

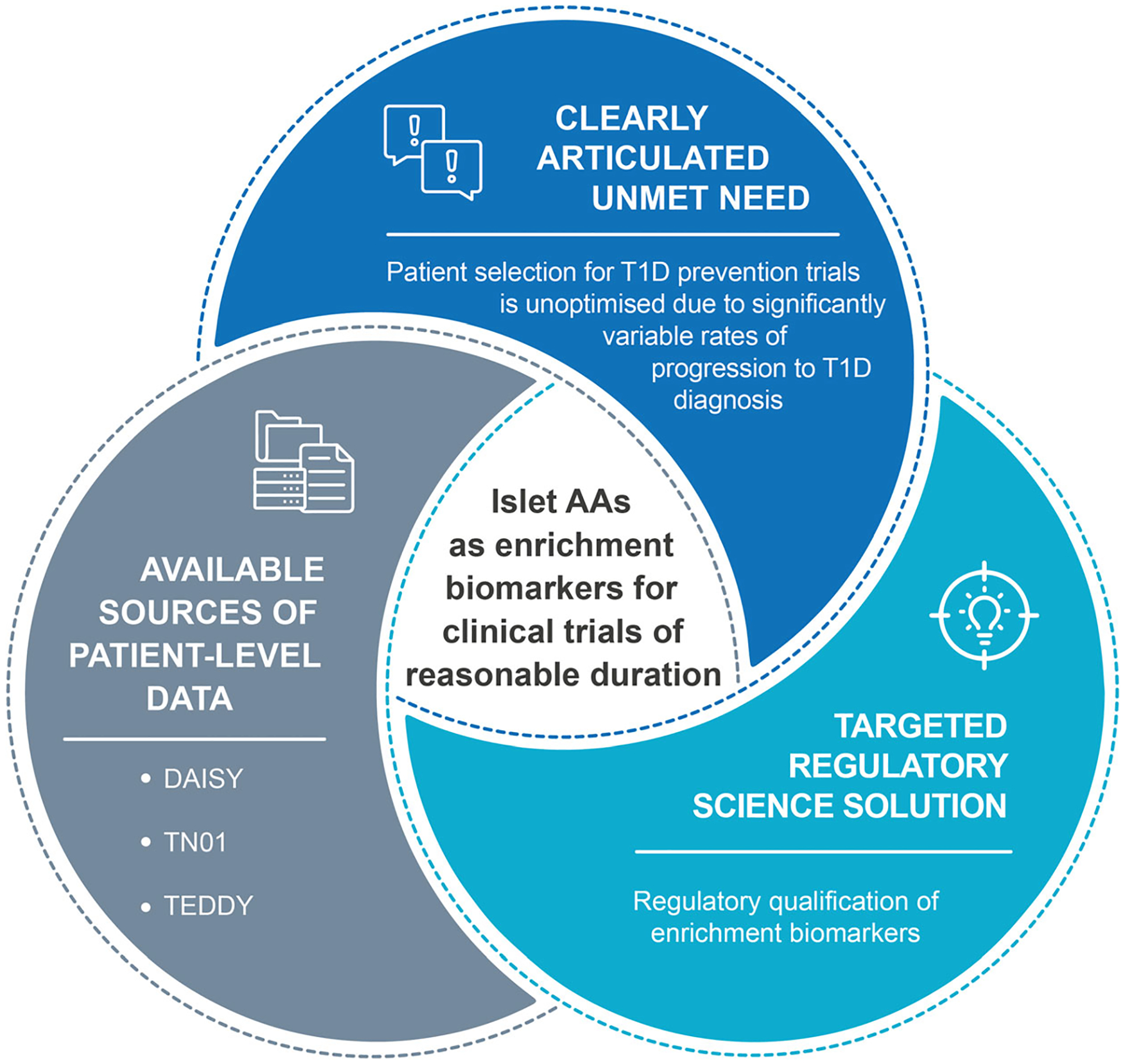

Fig. 4.

The process to identify a drug development solution concludes when a regulatory science solution is identified that is able to meet the clearly articulated unmet need with patient-level data that are available or highly likely to be available. After the target profile is sufficiently refined, a project plan to fully develop, validate and seek appropriate regulatory endorsement of the solution is developed and work to complete the tool begins. T1D, type 1 diabetes.

In February 2022, the T1DC received regulatory endorsement of islet AAs from the EMA through the qualification of novel methodologies pathway [9, 10]. Here, we outline the process by which the T1DC achieved this major milestone through the aggregation of anonymised participant-level data and submissions to the EMA, the results and impact of its work, and potential future directions.

Unmet clinical and drug development needs in type 1 diabetes

The pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes includes autoimmune destruction of pancreatic insulin-producing beta cells. As beta cells are destroyed, patients experience a progressive loss of insulin production, leading to defects in regulation of blood glucose levels. All individuals with type 1 diabetes will eventually require insulin replacement therapy. Lower HbA1c levels, achieved through intensive insulin replacement therapy, reduce the risk of diabetes-associated complications, such as nephropathy, neuropathy, retinopathy and cardiomyopathy [11, 12]. However, most patients struggle or fail to achieve glycaemic and HbA1c targets, and insulin replacement therapy does not replicate physiological insulin secretion and does not target the underlying autoimmune processes that result in type 1 diabetes [13]. To meaningfully prevent or delay the clinical diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in people at risk, therapies that modify the progression of disease are needed.

When considering the process of developing a new therapy, type 1 diabetes presents similar challenges as other chronic autoimmune disease areas, such as inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. A key challenge is the significant underlying patient heterogeneity and substantially different rates of disease progression, which often result in drug registration trials having difficulty identifying optimal patient populations. Clinical trials of therapies intended to prevent or delay stage 3 disease in type 1 diabetes must enrol individuals who are likely to progress to stage 3 disease during the trial.

Current trial enrichment strategies

Historically, clinical trials have included only participants at higher risk for type 1 diabetes to enrich for those likely to progress to stage 3 disease during the trials. However, given the variable rates in disease progression for populations deemed at high risk, failure to identify individuals who are likely to rapidly progress results in trials being burdensomely large or long, and therefore costly for sponsors. Known risk factors for islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes include a history of type 1 diabetes in a first-degree relative or the presence of genetic risk markers, such as specific HLA haplotypes [14]. Another well-established risk factor for the development of type 1 diabetes is the presence of multiple islet AAs, including those to insulin, GAD65, insulinoma antigen-2 (IA-2) and zinc transporter 8 (ZnT8) [15, 16]. Research has shown an increased risk and rate of progression to stage 3 type 1 diabetes in those with two or more islet AAs [17, 18]. Various additional factors, such as age of onset of islet autoimmunity, sex, BMI, race/ethnicity, high-risk HLA genotypes and islet AA titres, have also been shown to affect the rate of progression to stage 3 type 1 diabetes [16, 19–23]. However, the time between development of islet AAs and diagnosis of type 1 diabetes is variable.

According to the consensus staging classification for presymptomatic type 1 diabetes [2], individuals with stage 1 type 1 diabetes (presence of two or more islet AAs, normoglycaemia, presymptomatic) have a 5 year risk of symptomatic disease of approximately 44% [16], while individuals with stage 2 type 1 diabetes (presence of two or more islet AAs, dysglycaemia, presymptomatic) have a 5 year risk of approximately 75% [24]. These progression rates are useful clinically to guide monitoring and reduce the number of people who present with diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis; however, they are insufficient for designing clinical trials of reasonable duration. Similarly, criteria typically used in clinical trials to identify individuals at high risk for symptomatic disease (e.g. first- or second-degree relative status or presence of high-risk alleles) have not fully allowed trial populations to be enriched to optimise trial duration. Better tools are needed to allow for the identification of individuals who are likely to rapidly progress during clinical trials of reasonable duration.

Meeting drug development needs

The type 1 diabetes drug development ecosystem has several advantages for innovation relative to many other therapeutic areas. Large-scale international clinical research collaborations, long-term prospective studies and trial networks have provided a rich source of data. Researchers have dedicated decades to describing the natural history of islet autoimmunity and continue to evaluate proof-of-concept clinical trials in individuals at higher risk of disease. Screening efforts established across multiple regions worldwide have helped identify general populations of individuals at risk of progressing to stage 3 type 1 diabetes.

For example, in 2015, Fr1da was launched as the first programme of its kind to screen general population children in Bavaria, Germany, for presymptomatic type 1 diabetes. In this study, children in the general population can be screened for the presence of islet AAs during routine infant and early childhood well child visits at age 2–5 years, regardless of genetic risk status. As of early 2020, over 90,000 children had been screened; 280 (approximately 0.3%) of these children had two or more islet AAs, of whom 62 developed clinical type 1 diabetes [25]. In the USA, the Autoimmunity Screening for Kids (ASK) programme was piloted in 2014 [26] and expanded in 2017 to screen general population children aged 2–17 years through a variety of screening sites and strategies [27, 28]. Of the first 22,500 children screened, 110 (0.5%) had multiple islet AAs [29]. Momentum has built towards general population screening, and other programmes have been initiated or are being planned in the USA, Europe and Australia. An important element of these studies is the ability to identify individuals with early-stage type 1 diabetes who could be eligible for studies of novel therapies aimed at delaying or preventing the disease.

Secondary use of data from these and similar studies can improve the drug development process and support the development of new DDTs. For example, although islet AAs are frequently used as part of trial inclusion criteria, there remains no regulatory-endorsed mechanism to enrich studies for individuals at risk for type 1 diabetes who are likely to rapidly progress to stage 3 disease during clinical efficacy evaluation stages of development, including in registration studies. Large-scale type 1 diabetes screening studies can provide substantial evidence for obtaining regulatory approval of enrichment biomarkers, which allows clinical trials to include individuals who have a higher likelihood of experiencing an event (in this case diagnosis of type 1 diabetes) and hence increases the statistical power of the trials. Overall, the use of enrichment biomarkers allows for clinical trials to be streamlined.

To maximise the utility to drug developers of islet AAs as enrichment biomarkers, the T1DC aimed to incorporate important sources of patient heterogeneity, including sex, age and glycaemic status, with islet AA status using a model-based approach. The T1DC then sought to develop a regulatory-grade model capable of identifying individuals who are likely to progress to type 1 diabetes during trials of reasonable duration, defined by the consortium as 2–3 years.

Obtaining regulatory endorsement of islet AAs as enrichment biomarkers for type 1 diabetes prevention clinical trials

Regulatory agencies often require datasets that include multiple studies and cohorts, and data must often be submitted to the regulatory agencies as part of the endorsement process. The T1DC provides a critical pre-competitive space for collaborators, who often compete with individual products, to share resources and expertise. Critically, in addition to sharing data, consortium stakeholders also contribute in the form of statistical analyses, assay performance characterisation, knowledge on data standards, and scientific and regulatory guidance, among other things, which are all required to obtain regulatory endorsements.

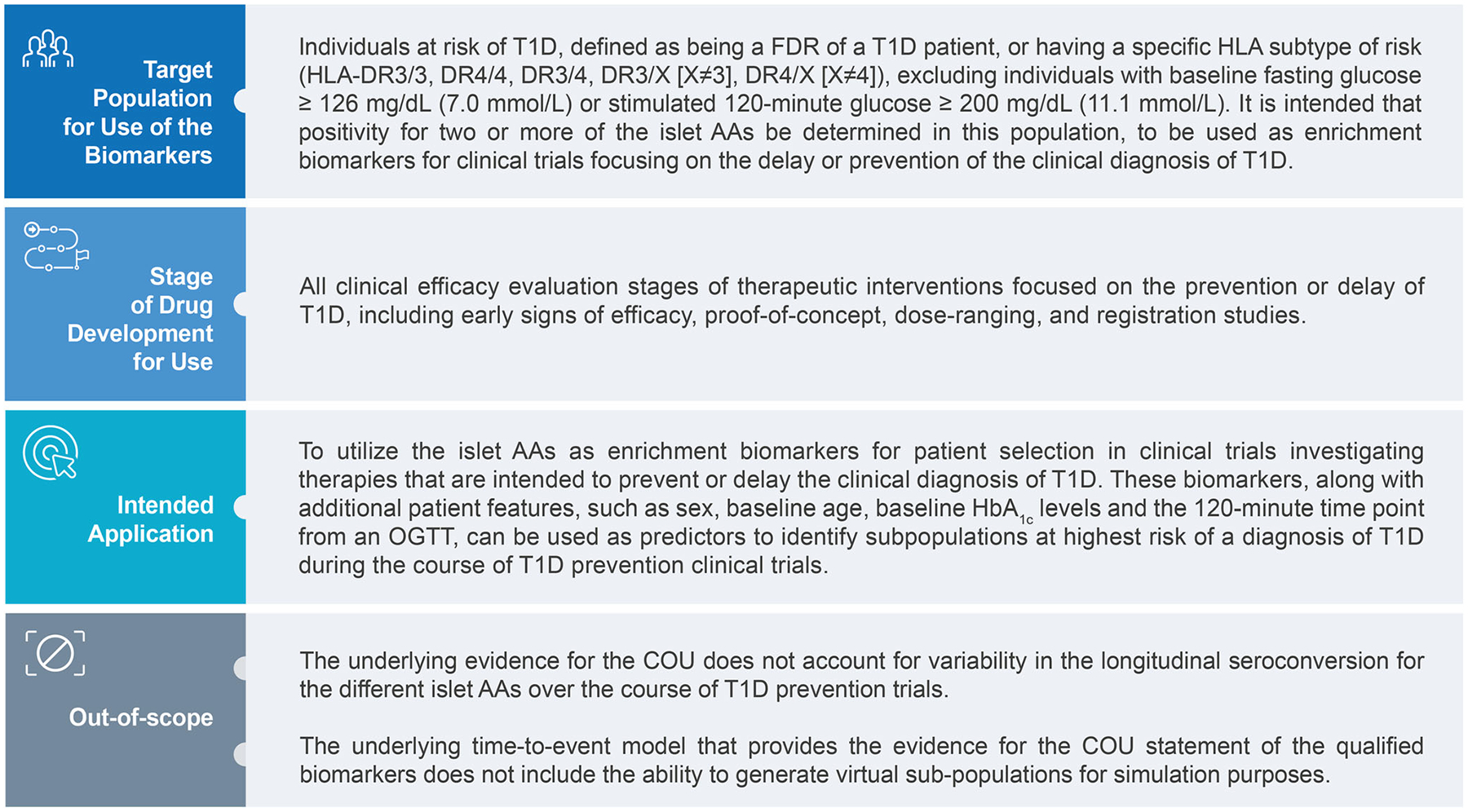

The T1DC initially sought qualification advice from the EMA. During the qualification advice procedure, the EMA issued a letter of support for the T1DC’s work and encouraged the type 1 diabetes community to participate [30]. The EMA also provided feedback regarding the data available at that time and the intended analysis. Accordingly, the T1DC sought to aggregate historical participant-level data (and the required supporting analytical evidence) from several large longitudinal type 1 diabetes observational studies, and leverage member expertise to develop an evidentiary package sufficient to support a defined context of use (COU). A COU, akin to a drug’s labelled indication, should be fully supported by the submitted data and analyses and provides information on precisely how a tool is endorsed for use. Like an investigational product’s target development profile, a target COU is initially defined and then modified throughout the DDT development process as new data are obtained and following conversations with regulators. The final qualified COU for use of islet AAs as enrichment biomarkers is provided in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

COU for the use of islet AAs as enrichment biomarkers in the EMA’s qualification opinion. FDR, first-degree relative; T1D, type 1 diabetes.

Data sharing and standardisation

The T1DC received, curated and aggregated data from three longitudinal studies: the Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY) study (data locked as of June 2018), the TrialNet Pathway to Prevention (TN01; data locked as of December 2018) and the Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY; data locked as of June 2017). These three studies generally aim to identify factors (e.g. environmental, metabolic, immunological and genetic) that contribute to progression to type 1 diabetes in at-risk individuals. Importantly, these studies include two birth cohort studies (DAISY and TEDDY) that include the associated full time history of relevant events, such as the development of multiple islet AAs and clinical diagnosis, and a patient population with data available from the time of presentation with multiple islet AAs (TN01).

According to feedback received from the EMA during the qualification advice procedure, the modelling dataset comprised data from TEDDY and TN01, while data from DAISY were used for external validation. A derived baseline was constructed as the first instance at which an individual had confirmation of the presence of any two or more islet AAs, an HbA1c assessment and an OGTT. These variables reflect how sponsors typically assess individuals for enrolment in late-stage clinical trials (i.e. antibody screening followed by glycaemic assessment). Individuals not yet clinically diagnosed with type 1 diabetes and without HbA1c and/or OGTT values that satisfied ADA criteria for likely type 1 diabetes were excluded from the analysis, as they would probably be excluded from relevant clinical trials (and thus not meet the specified COU).

Modelling analysis, results and regulatory submission

The aggregated analysis dataset included 2317 individuals with at least two islet AAs. Complete information required for the derived baseline was available for 2022 individuals, who were included in the modelling analysis. Of these 2022 individuals, 512 were diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, with a mean time to diagnosis of 2.16 years (SD 1.51 years). The validation dataset included 34 individuals with at least two islet AAs and the necessary derived baseline data. Table 1 describes the participants included in the analysis and validation datasets.

Table 1.

Summary of covariates at the derived baseline and percentage of participants who progressed to a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in the analysis and validation datasets

| Study | Participants (n) | Age, years | Female, % | Has FDR with type 1 diabetes, % | 0 min OGTT, mmol/l | 120 min OGTT, mmol/l | HbA1c, mmol/mol | HbA1c, % | Type 1 diabetes diagnosis, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEDDY | 353 | 5.8 (2.5) | 41.6 | 18.4 | 4.8 (0.5) | 6.0 (1.3) | 33.3 (2.6) | 5.2 (0.2) | 39.1 |

| TN01 | 1669 | 13.0 (10.0) | 45.5 | 91.0 | 4.9 (0.5) | 6.7 (1.6) | 32.2 (3.5) | 5.1 (0.3) | 22.9 |

| DAISY | 34 | 10.9 (4.4) | 47.1 | 52.9 | 4.8 (0.5) | 6.4 (1.3) | 34.4 (4.2) | 5.3 (0.4) | 35.3 |

Data are mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated

FDR, first-degree relative

A review of the published literature on previous modelling efforts was undertaken to inform the analysis needed to provide evidence supporting the use of islet AAs in clinical trial decision making. The modelling analysis was discussed with the EMA at several points during the qualification process and is described thoroughly in the T1DC’s regulatory submissions (available on the EMA’s website: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en), the EMA’s qualification opinion and a separate publication [10, 31, 32]. Briefly, a parametric accelerated failure time (AFT) model was developed based on the aggregated dataset to predict time to type 1 diabetes diagnosis. A Weibull distribution for the baseline hazard was selected for the AFT model. The covariates that were evaluated during the model building process included islet AA combinations (all possible combinations of two or three islet AAs or all four islet AAs), study ID, flag for high-risk HLA subtype, first-degree relative with type 1 diabetes, age, sex, BMI, HbA1c and OGTT measurements.

Summary results indicated that the combinations of GAD65 and insulin/proinsulin AAs and GAD65 and ZnT8 had the lowest relative risks compared with all other combinations, while the combination of IA-2 and ZnT8 had the highest relative risk [31, 32]. Relative risks for all combinations of three islet AAs were not significantly different from the baseline hazard. The presence of all four islet AAs had a marginal increased relative risk compared with the baseline hazard. Inclusion of 120 min OGTT measurements, baseline age, sex and HbA1c values had a significant ability to further stratify the risk of type 1 diabetes diagnosis within islet AA-positive populations [31, 32]. Following regulatory submissions of the full analysis and discussion meetings with the regulators, EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use concluded that the evidence provided through the modelling exercise was sufficient to issue a positive qualification opinion for the use of islet AAs, with relevant clinical features, as enrichment biomarkers in type 1 diabetes prevention clinical trials.

Impact of the qualification on type 1 diabetes trials

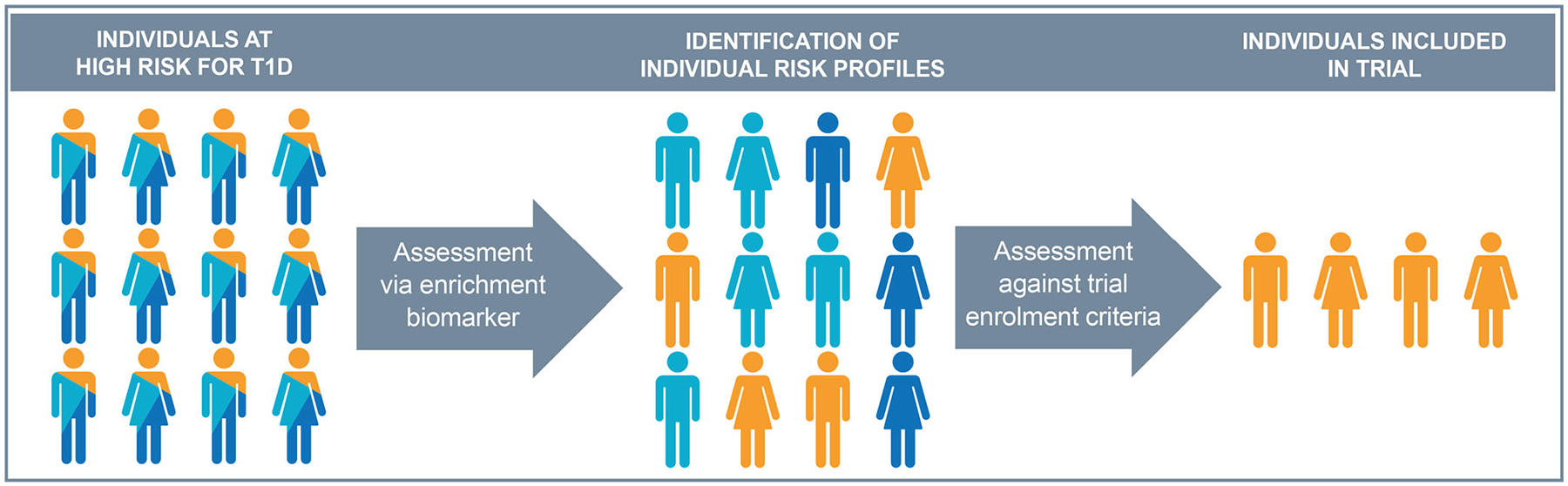

The overall goal of the EMA’s qualification of novel methodologies programme is to facilitate formal EMA review of new innovative methods or DDTs, which can drastically transform the product development landscape. The current work represents the first regulatory-endorsed approach to clinical trial enrichment in type 1 diabetes. The models, which will now be made publicly available, allow individual risk assessment during study screening to identify individuals who are eligible for participation (Fig. 6) and provide drug developers with a higher level of confidence that their trials are enriched in a manner consistent with regulatory agency thinking.

Fig. 6.

Utility of islet AAs (with additional clinical features) as enrichment biomarkers to identify individuals at high risk of disease progression for enrolment in type 1 diabetes (T1D) prevention clinical trials. Islet AA status, with relevant clinical features (defined in the qualification as sex, baseline age, blood glucose measures from the 120 min OGTT and HbA1c levels), are used as a model-based enrichment biomarker, according to the qualified COU. This allows for identification of an individual’s risk of progression and is assessed against the established trial enrolment criteria to identify eligible individuals. In the T1DC qualification opinion, individuals at high risk were defined as being first-degree relatives of a type 1 diabetes patient or having a specific HLA subtype of risk (HLA-DR3/3, DR4/4, DR3/4, DR3/X [X≠3], DR4/X [X≠4]), excluding individuals with baseline fasting glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l (≥126 mg/dl) or stimulated 120 min glucose ≥11.1 mmol/l (≥200 mg/dl).

As such, this endorsement will improve product developers’ ability to design less risky and more efficient clinical trials of agents that are intended to prevent or delay the onset of type 1 diabetes (i.e. trials of reduced size and/or length, while being adequately powered). As the endorsed COU includes use in ‘all clinical efficacy evaluations stages … including early signs of efficacy, proof-of-concept, dose-ranging, and registration studies’, the tool is capable of supporting decision making across the clinical development spectrum. By making the regulatory submission and models publicly available, they can be incorporated into the design of trials by the entire community. A graphical user interface will also be made publicly available to better aid product developers in designing trials, based on the qualification opinion models.

Building on the accomplishments of this work, the T1DC community identified additional unmet needs in type 1 diabetes prevention drug development. Next, the T1DC community intends to develop and obtain regulatory endorsement of a clinical trial simulation (CTS) tool for type 1 diabetes prevention studies. CTS tools allow clinically relevant features and measures, along with relevant sources of variability, such as patient baseline characteristics or trial designs, to be modelled such that in silico optimisation of trial design can be carried out prior to the initiation of live trials. CTS tools can increase the efficiency of trials (e.g. enabling power to be maintained when using smaller sample sizes or in trials of shorter duration). As significantly more data are required to build this tool, the T1DC has already begun accelerating its data sharing efforts. To date, the T1DC has acquired six datasets from across the community, representing data from 280,974 screened individuals.

Lessons learned

This work represents the first major data sharing collaboration between drug developers, clinical and academic researchers and philanthropic organisations focused on generating new tools for use in type 1 diabetes prevention drug development. Lessons learned over the course of this endeavour will inform future similar efforts by the type 1 diabetes community.

Data sharing intended to support medical product development requires significant forethought and can be enhanced through prospective consideration of the use of data standards, data dictionaries and consenting processes that explicitly allow for secondary uses of data. Given the importance of data generated from longitudinal observational trials and clinical studies, participant consent for secondary uses of data from these studies is critical, as this is often not possible to obtain after study completion. Ensuring that data are collected and quality controlled in a manner that is suitable for regulatory submissions is also essential to maximise the impact of data from these studies. Further, aligning study data collection procedures with established standards at an early point during study planning can speed up protocol development and future data collection.

Future efforts in type 1 diabetes should also consider the collection of data from continuous glucose monitors (CGMs), as these devices are rich sources of data. Small studies of islet AA-positive individuals have assessed the utility of CGMs in assessing glycaemic status and beta cell function, controlling HbA1c and predicting progression to stage 3 disease [33–36]. In the clinical trial setting, CGMs may provide benefits over currently accepted clinically meaningful markers of disease, such as OGTTs, which can be burdensome for patients. However, work remains to demonstrate how CGM-generated data translate to clinical meaningfulness in type 1 diabetes prevention and how this can be applied in the regulatory context.

Conclusions

The collaborative space provided by the T1DC has resulted in islet AAs being endorsed by the EMA for use as enrichment biomarkers in type 1 diabetes prevention clinical trials. In its qualification opinion, the EMA acknowledged ‘the unmet need for better means to optimize drug development’ in type 1 diabetes and supported ‘the clinical interest of identifying a good biomarker for type 1 diabetes onset’ in high-risk populations [10]. By identifying pressing unmet drug development needs in type 1 diabetes, gathering consensus across type 1 diabetes stakeholders and facilitating actionable data sharing, a powerful new tool has been developed for the community. Future trials that implement this tool should be designed in consideration of secondary data sharing to facilitate the development of additional type 1 diabetes DDTs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the T1DC members for their guidance and support. The TEDDY and TN01 studies were conducted by the TEDDY and TN01 investigators and were supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). The data from TEDDY and TN01 reported here were supplied by the NIDDK Central Repositories. This manuscript was not prepared in collaboration with the investigators of the TEDDY and TN01 studies and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the TEDDY and TN01 studies, the NIDDK Central Repositories or the NIDDK. The T1DC recognises the DAISY study group for contribution of data and provision of support. The T1DC thanks A. J. K. Williams (University of Bristol) and L. Yu (University of Colorado Denver) for their contributions to the documentation of the islet AA assays used in the TEDDY, TN01 and DAISY studies. The T1DC thanks J. Podichetty (Critical Path Institute), P. Lang (Critical Path Institute) and J. Burton (Critical Path Institute) for their contributions to the modelling work.

Funding

The T1DC and this project are supported by funds from JDRF International, Helmsley Charitable Trust, Janssen Research & Development, Novo Nordisk and ProventionBio. The Critical Path Institute is supported by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and is 56.5% funded by the FDA/HHS (totalling $16,749,891) and 43.5% funded by non-government sources (totalling $12,895,366). The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, the FDA/HHS or the US government. For more information, please see www.FDA.gov.

Authors’ relationships and activities

JLD and CR are currently employees of Janssen Research & Development. MM is currently an employee of JDRF International. BIF is a member of the advisory board for ProventionBio and is supported by a training grant from JDRF International (JDRF 5-ECR-2017-388-A-N). The authors declare that there are no other relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, their work.

Abbreviations

- AA

Autoantibodies

- CGM

Continuous glucose monitor

- COU

Context of use

- C-Path

Critical Path Institute

- CTS

Clinical trial simulation

- DAISY

Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young

- DDT

Drug development tool

- EMA

European Medicines Agency

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- IA-2

Insulinoma antigen-2

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- T1DC

Type 1 Diabetes Consortium

- TEDDY

Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young

- TN01

TrialNet Pathway to Prevention

- ZnT8

Zinc transporter 8

Footnotes

Supplementary Information The online version contains a slideset of the figures for download, which is available to authorised users at https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-022-05751-0.

Data availability

The aggregated dataset that was the basis for the work discussed in this publication is not publicly available, as per the requirements in the data contribution agreements.

References

- 1.Mobasseri M, Shirmohammadi M, Amiri T, Vahed N, Hosseini Fard H, Ghojazadeh M (2020) Prevalence and incidence of type 1 diabetes in the world: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Promot Perspect 10(2):98–115. 10.34172/hpp.2020.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Insel RA, Dunne JL, Atkinson MA et al. (2015) Staging presymptomatic type 1 diabetes: a scientific statement of JDRF, the Endocrine Society, and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 38(10):1964–1974. 10.2337/dc15-1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herold KC, Bundy BN, Long SA et al. (2019) An anti-CD3 antibody, teplizumab, in relatives at risk for type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 381(7):603–613. 10.1056/NEJMoa1902226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sims EK, Bundy BN, Stier K et al. (2021) Teplizumab improves and stabilizes beta cell function in antibody-positive high-risk individuals. Sci Transl Med 13(583):eabc8980. 10.1126/scitranslmed.abc8980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephenson D, Sauer J-M (2014) The Predictive Safety Testing Consortium and the Coalition Against Major Diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 13(11):793–794. 10.1038/nrd4440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kraus VB (2018) Biomarkers as drug development tools: discovery, validation, qualification and use. Nat Rev Rheumatol 14(6): 354–362. 10.1038/s41584-018-0005-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conrado DJ, Larkindale J, Berg A et al. (2019) Towards regulatory endorsement of drug development tools to promote the application of model-informed drug development in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 46(5):441–455. 10.1007/s10928-019-09642-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arnerić SP, Kern VD, Stephenson DT (2018) Regulatory-accepted drug development tools are needed to accelerate innovative CNS disease treatments. Biochem Pharmacol 151:291–306. 10.1016/j.bcp.2018.01.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.European Medicines Agency (2020) Qualification of novel methodologies for drug development: guidance to applicants. Available from www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/qualification-novel-methodologies-drug-development-guidance-applicants_en.pdf. Accessed 5 April 2021

- 10.European Medicines Agency (2022) Qualification opinion of islet autoantibodies (AAs) as enrichment biomarkers for type 1 diabetes (T1D) prevention clinical trials. Available from www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/qualification-opinion-islet-autoantibodies-aas-enrichment-biomarkers-type-1-diabetes-t1d-prevention_en.pdf. Accessed 27 April 2022

- 11.Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group, Nathan DM, Genuth S et al. (1993) The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 329 (14): 977–986. 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT)/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) Study Research Group (2016) Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular outcomes in type 1 diabetes: the DCCT/EDIC study 30-year follow-up. Diabetes Care 39(5):686–693. 10.2337/dc15-1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foster NC, Beck RW, Miller KM et al. (2019) State of type 1 diabetes management and outcomes from the T1D exchange in 2016–2018. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics 21(2):66–72. 10.1089/dia.2018.0384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrat LA, Vehik K, Sharp SA et al. (2020) A combined risk score enhances prediction of type 1 diabetes among susceptible children. Nat Med 26(8):1247–1255. 10.1038/s41591-020-0930-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krischer JP, Liu X, Vehik K et al. (2019) Predicting islet cell autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes: an 8-year TEDDY study progress report. Diabetes Care 42(6):1051–1060. 10.2337/dc18-2282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ziegler AG, Rewers M, Simell O et al. (2013) Seroconversion to multiple islet autoantibodies and risk of progression to diabetes in children. JAMA 309(23):2473–2479. 10.1001/jama.2013.6285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veijola R, Koskinen M, Helminen O, Hekkala A (2016) Dysregulation of glucose metabolism in preclinical type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 17(Suppl 22):25–30. 10.1111/pedi.12392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu P, Krischer JP, Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group (2016) Prognostic classification factors associated with development of multiple autoantibodies, dysglycemia, and type 1 diabetes-a recursive partitioning analysis. Diabetes Care 39(6):1036–1044. 10.2337/dc15-2292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frohnert BI, Ide L, Dong F et al. (2017) Late-onset islet autoimmunity in childhood: the Diabetes Autoimmunity Study in the Young (DAISY). Diabetologia 60(6):998–1006. 10.1007/s00125-017-4256-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferrara CT, Geyer SM, Evans-Molina C et al. (2017) The role of age and excess body mass index in progression to type 1 diabetes in at-risk adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102(12):4596–4603. 10.1210/jc.2017-01490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tosur M, Geyer SM, Rodriguez H et al. (2018) Ethnic differences in progression of islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes in relatives at risk. Diabetologia. 10.1007/s00125-018-4660-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Köhler M, Beyerlein A, Vehik K et al. (2017) Joint modeling of longitudinal autoantibody patterns and progression to type 1 diabetes: results from the TEDDY study. Acta Diabetol 54(11):1009–1017. 10.1007/s00592-017-1033-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steck AK, Vehik K, Bonifacio E et al. (2015) Predictors of progression from the appearance of islet autoantibodies to early childhood diabetes: The Environmental Determinants of Diabetes in the Young (TEDDY). Diabetes Care 38(5):808–813. 10.2337/dc14-2426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krischer JP, Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group (2013) The use of intermediate endpoints in the design of type 1 diabetes prevention trials. Diabetologia 56(9):1919–1924. 10.1007/s00125-013-2960-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ziegler A-G, Kick K, Bonifacio E et al. (2020) Yield of a public health screening of children for islet autoantibodies in Bavaria. Germany. JAMA 323(4):339. 10.1001/jama.2019.21565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gesualdo PD, Bautista KA, Waugh KC et al. (2015) Feasibility of screening for T1D and celiac disease in a pediatric clinic setting. Pediatr Diabetes. 10.1111/pedi.12301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geno Rasmussen CR, Rewers M, Baxter J et al. (2018) Population screening for T1D and celiac disease-Autoimmunity Screening for Kids (ASK). Diabetes 67(supplement_1):182-OR. 10.2337/db18-182-OR [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McQueen RB, Rasmussen CG, Waugh K et al. (2020) Cost and cost-effectiveness of large-scale screening for type 1 diabetes in Colorado. Diabetes Care 43(7):1496–1503. 10.2337/dc19-2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steck AK, Dong F, Geno Rasmussen CR et al. (2021) CGM metrics predict imminent progression to type 1 diabetes: Autoimmunity Screening for Kids (ASK) study. American Diabetes Association. Figure 10.2337/figshare.17049941.v1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.European Medicines Agency (2020) Letter of support for ‘Islet autoantibodies as enrichment biomarkers for type 1 diabetes prevention studies, through a quantitative disease progression model’. Available from www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/letter-support-islet-autoantibodies-enrichment-biomarkers-type-1-diabetes-prevention-studies-through_en.pdf. Accessed 2 February 2022

- 31.Type 1 Diabetes Consortium (2020) Islet autoantibodies as enrichment biomarkers for type 1 diabetes prevention clinical trials: briefing dossier for qualification opinion. Available from www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/other/islet-autoantibodies-aas-briefing-document_en.pdf. Accessed 2 February 2022

- 32.Podichetty JT, Lang P, O’Doherty IM et al. (2022) Leveraging real-world data for EMA qualification of a model-based biomarker tool to optimize type-1 diabetes prevention studies. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 111(5):1133–1141. 10.1002/cpt.2559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helminen O, Pokka T, Tossavainen P, Ilonen J, Knip M, Veijola R (2016) Continuous glucose monitoring and HbA1c in the evaluation of glucose metabolism in children at high risk for type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 120:89–96. 10.1016/j.diabres.2016.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Dalem A, Demeester S, Balti EV et al. (2015) Relationship between glycaemic variability and hyperglycaemic clamp-derived functional variables in (impending) type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia 58(12):2753–2764. 10.1007/s00125-015-3761-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US) (2021) Identifier: NCT04335513, Trial of early initiation of CGM-guided insulin therapy in stage 2 T1D (TESS). Available from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04335513. Accessed 16 May 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steck AK, Dong F, Taki I et al. (2019) Continuous glucose monitoring predicts progression to diabetes in autoantibody positive children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 104(8):3337–3344. 10.1210/jc.2018-02196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The aggregated dataset that was the basis for the work discussed in this publication is not publicly available, as per the requirements in the data contribution agreements.