Abstract

Onchocerciasis is a major cause of blindness. Although the World Health Organization has been successful in reducing onchocerciasis as a public health problem in parts of West Africa, there remain an estimated 17 million people infected with Onchocerca volvulus, the parasite that causes this disease. Ocular pathology can be manifested in any part of the eye, although disease manifestations are frequently characterized as either posterior or anterior eye disease. This review focuses on onchocerca-mediated keratitis that results from an inflammatory response in the anterior portion of the eye and summarizes what is currently known about human disease. This review also describes studies with experimental models that have been established to determine the immunological mechanisms underlying interstitial keratitis. The pathogenesis of keratitis is thought to be due to the host inflammatory response to degenerating parasites in the eye; therefore, the primary clinical symptoms of onchocercal keratitis (corneal opacification and neovascularization) are induced after injection of soluble O. volvulus antigens into the corneal stroma. Experimental approaches have demonstrated an essential role for sensitized T helper cells and shown that cytokines can regulate the severity of keratitis by controlling recruitment of inflammatory cells into the cornea. Chemokines are also important in inflammatory cell recruitment to the cornea, and their role in onchocerciasis is being examined. Further understanding of the molecular basis of the development of onchocercal keratitis may lead to novel approaches to immunologically based intervention.

The World Health Organization estimates that 123 million people live in areas of Africa, central and South America, Sudan, and Yemen where onchocerciasis (river blindness) is endemic and that 17.7 million people are infected with Onchocerca volvulus, the parasitic helminth that causes this disease (82). Of these, approximately 270,000 are blind and 500,000 have severe visual impairment (82). These numbers may be underestimates, since routine surveys of onchocercal morbidity do not assess visual-field constriction (1, 51). In an effort to combat river blindness, the World Health Organization launched the Onchocerciasis Control Program (OCP) in 1974. The OCP had a mandate to eliminate onchocerciasis as a public health problem in seven countries in West Africa by applying larvicide to blackfly breeding sites. In the 1980s, ivermectin (Mectizan) was shown to be highly effective at reducing the larval burden without causing the side effects induced by diethylcarbamazine (Hetrazan), and in 1987 ivermectin was introduced as part of the program (82). The success of this approach led to expansion of the OCP to 11 countries, and by 1994 the OCP had reduced the risk of disease for 30 million people (48, 82).

When the OCP officially ends in 2002, there will remain an estimated 15 million infected individuals outside the OCP area (62). In 1995, the World Bank established a community-based program, termed the African Program for Onchocerciasis Control, to distribute ivermectin (62). This drug has been and will continue to be donated by Merck & Co., Inc., as part of the Mectizan Donation Program.

To date, ivermectin resistance has been reported only in nematodes that cause veterinary disease (4, 29, 30, 83). However, since this is the only approved drug for onchocerciasis, development of resistance in humans would have a severe impact on public health. Alternate strategies for the control of onchocerciasis as a public health problem include vaccine development, based on understanding of the immune processes involved in parasite clearance, and antipathology approaches based on understanding the mechanism of disease pathogenesis.

PATHOGENESIS OF ONCHOCERCIASIS

Simulium blackflies are the obligate intermediate hosts of O. volvulus. The flies breed in fast-flowing rivers, and infective-stage larvae (L3) are released from infected blackflies during a blood meal. L3 larvae undergo two molts to become adult worms, which can be detected in subcutaneous collagenous nodules. Females release approximately 1,000 microfilariae (L1) per day over a 9- to 14-year period (67, 82), and the cycle is continued after uptake by blackflies during a blood meal.

The severity of ocular pathology in distinct regions of West Africa is due in part to infection with different strains of the parasite. Ocular manifestations are more prevalent in the savanna regions of West Africa, whereas blindness is rare in persons infected in the rain forest regions (13, 14). The difference in strains was illustrated after subconjunctival injection of forest and savanna strains into rabbits. In these studies, Duke and coworkers found that microfilariae of the savanna strain induce a more severe inflammatory response in the cornea than do those of the rain forest strain (18, 27). Subsequent studies led to the identification of DNA sequences specific for the two strains of the parasite (22, 23), and classification of these strains based on sequence correlated well with pathologic manifestations (85). While initial studies suggested that certain species of the blackfly vector transmitted distinct parasite strains, delineation of zones containing these strains has become more difficult as rain forest has been cleared in many parts of West Africa. Transition zones have been shown to contain both strains and/or hybrids (74).

With the exception of nodule formation around the adult worms, most infected individuals manifest no disease symptoms. The standard diagnostic test for onchocerciasis is the skin snip, performed by placing a small piece of skin in a drop of saline or culture medium. After incubation, microscopic examination reveals microfilariae emerging from the tissue. Despite the presence of a heavy worm burden, the skin of most infected individuals appears normal, and histological examination shows parasites in the dermis with no inflammatory response. Although the exact mode of penetration from the skin into the eye is not known, studies by Duke and Garner demonstrated that microfilariae can migrate from the conjunctiva into the cornea (18, 19). Both dermal and ocular manifestations are thought to occur when the parasites die and initiate an inflammatory response. It is the host response to the parasites, rather than direct cytotoxic molecules released from the parasite, that is generally thought to be responsible for disease. This notion is supported by studies in which individuals treated with the anthelminthic diethylcarbamazine develop severe pruritus, presumably as a result of rapid death of microfilariae in the skin (52).

Ocular pathology can be manifested in any part of the eye, although disease manifestations are frequently characterized either as posterior or anterior eye disease. In patients with posterior ocular onchocerciasis, there is atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium, which later becomes more widespread (1). Advanced lesions involve subretinal fibrosis. Induction of posterior disease is thought to involve autoimmune responses, and cross-reactive proteins have been described (10, 46, 68, 79, 80). More direct evidence for a role for cross-reactive immune responses in posterior-segment ocular onchocerciasis was shown by McKechnie et al., who immunized rats with a 39-kDa. O. volvulus protein found to be cross-reactive with a 44-kDa human retinal protein. These animals developed several pathological changes in the posterior segment of the eye, including up-regulation of major histocompatibility complex class II and CD68 (47). Although cross-reactivity with this protein was also observed in human corneas (46), there is no direct evidence of a role for autoimmunity in anterior disease.

In anterior disease, motile worms in the cornea or anterior chamber of the eye can be detected by slit lamp examination after the microfilariae migrate into ocular tissue. When the parasites die, either by natural attrition or after chemotherapy, a local inflammatory response is initiated and causes the formation of discrete areas of corneal opacification (punctuate keratitis). As a result of continued exposure to the parasite or heavy infection, opacities develop at the peripheral stroma, leaving the central area clear and often containing many parasites. Opacification progresses centrally, along with deep vascularization that obscures the entire cornea, causing a complete loss of vision (Fig. 1) (1, 57). Sclerosing keratitis ultimately develops, leading to irreversible blindness.

FIG. 1.

River blindness in a 29-year-old man from Cote d’Ivoire. Note the corneal opacification in the right eye. This individual also had corneal neovascularization and severe conjunctivitis. (Photograph by Eric Pearlman.)

IMMUNOLOGICAL PARAMETERS ASSOCIATED WITH CORNEAL DISEASE

Given the obvious difficulty of obtaining ocular tissue from infected individuals, at least three alternative approaches have been taken to characterize the immunological parameters underlying the pathogenesis of this disease. These include (i) examination of peripheral blood responses, in which parasite-specific T-cell and antibody responses are correlated with disease manifestations; (ii) direct examination of adjacent conjunctival tissue; and (iii) use of animal models of ocular onchocerciasis. Most of these studies have focused on the role of T-cell-associated cytokines.

Cellular Responses in Peripheral Blood of Infected Individuals

Clinical manifestations of onchocerciasis range from generalized microfiladermia and no clinical symptoms to severe localized infection (sowda) and few dermal microfilariae (reviewed by Ottesen [52]). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with generalized microfiladermia and no clinical symptoms have a suppressed proliferative response to parasite antigens (25, 33, 52). These individuals also produce cytokines associated with a T helper type 2 response compared with individuals exposed for a short time (45). Consistent with this finding, Limaye et al. found elevated interleukin-5 (IL-5) levels in serum of patients treated with diethylcarbamazine, which rapidly kills microfilariae and induces eosinophilia (43). However, putatively immune individuals, who are resident in areas of highly endemic infection but have no indication of infection, also have elevated IL-2 and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) responses (15, 20, 21, 70, 81).

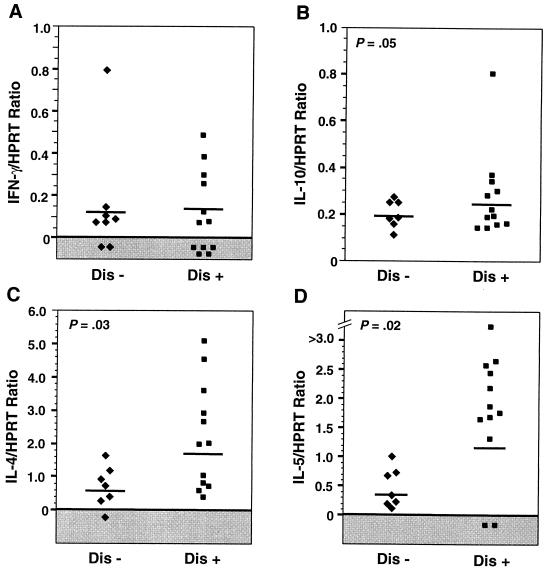

In relation to disease manifestations, Freedman’s group compared peripheral blood leukocyte responses from individuals with and without ocular manifestations (61). They reported that in vitro stimulation with parasite antigens of cells from individuals with ocular onchocerciasis produced more IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10 than did stimulation of cells from infected individuals with no ocular disease. These observations imply that ocular pathology is associated with elevated Th2 responses (Fig. 2) (61).

FIG. 2.

Cytokine expression by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from O. volvulus-infected patients with (Dis+) or without (Dis−) ocular disease. Cells were stimulated with O. volvulus antigens, and cytokine expression was determined by reverse transcription-PCR in relation to the housekeeping gene HPRT. Note the elevated IL-4, IL-5, and IL-10 expression in Dis+ individuals. The horizontal lines denote geometric means. Reprinted from reference 61 with permission of the publisher.

Cellular Responses in Conjunctival Tissue from Onchocerciasis Patients

Conjunctival specimens from infected individuals provide evidence of chronic cellular inflammation and activation of resident cell populations, as indicated by elevated levels of major histocompatibility complex class II molecules and IL-2 receptor expression (9). CD4+ cells were numerous and IL-4 gene expression was elevated in conjunctival biopsy specimens, indicating that a Th2 response is manifested locally as well as systemically in individuals with ocular disease (8).

Experimental Animal Models

Although O. volvulus infects chimpanzees, gorillas, and cynomolgus monkeys, there is no animal model of natural infection with O. volvulus that results in ocular disease (32, 78a). Experimental animal models have therefore been developed that reproduce many of the clinical manifestations observed in human disease (recently reviewed in reference 54) (Fig. 3). These animal models have proven to be extremely useful in understanding the immunopathogenesis of onchocercal keratitis, especially in relation to inflammatory cell recruitment to the cornea.

FIG. 3.

Corneal opacification and neovascularization in a BALB/c mouse. Animals were immunized subcutaneously and challenged intrastromally with soluble O. volvulus antigens. No inflammatory response was induced in the absence of prior immunization. Reprinted from reference 59 with permission of the publisher.

Several studies have independently demonstrated a requirement for antigen-specific T cells in the development of onchocercal keratitis. Donnelly et al. showed that guinea pigs develop ocular disease characterized by limbitis, corneal inflammation, and peripheral corneal neovascularization after intracorneal inoculation of the cattle parasite O. lienalis (16, 17). These workers clearly demonstrated that the inflammatory response and the severity of keratitis is greatly exacerbated if the animals are sensitized prior to ocular challenge, thereby implying a role for specific immunity. They also noted that diethylcarbamazine-induced killing of the parasites results in an exacerbated inflammatory response, which is consistent with the notion that the pathology associated with keratitis is due to a host immune-system-mediated inflammatory response.

Gallin et al. showed that clinical manifestations similar to onchocercal keratitis can be induced in guinea pigs by direct injection of soluble O. volvulus antigens into the corneal stroma, but only if the animals have been previously sensitized (26). Chakravarti et al. found similar results with A/J mice, in which prior immunization with O. volvulus antigens is essential for maximal severity of disease (7). These workers also demonstrated directly the presence of CD4+ cells but not CD8+ cells in the corneal stroma of these animals (5).

Data from our laboratory also showed that prior immunization is necessary for the induction of pathology in BALB/c mice (59). In addition, our studies demonstrated that T cells are required for the development of keratitis, since athymic mice that were immunized and challenged intrastromally with O. volvulus antigen did not develop keratitis (59). Furthermore, adoptive transfer of spleen cells from immunized but not from naive mice reconstituted the development of keratitis in these animals after intrastromal challenge. Although these studies did not identify specific subpopulations of cells, mRNA for CD4 and CD8 cells was detected in recipient corneas.

As observed during human infections, mice develop a predominant Th2 response to repeated exposure to O. volvulus antigen; O. volvulus-stimulated lymph node and spleen cells from immunized mice produce IL-4 and IL-5 and little IFN-γ (59). This response is also manifested locally, since mRNA for IL-4 and IL-5 is up-regulated in the corneas of immunized mice upon intrastromal challenge (6, 58, 59). Subsequent studies have investigated the effect of cytokine modulation on the development of keratitis. These data indicate that the severity of keratitis is regulated by these cytokines and that the regulation is associated with infiltration of inflammatory cells, notably eosinophils, into the cornea. The association between disease severity and presence of a Th2 response suggested that modulation of the Th2 response would reduce the severity of keratitis. Therefore two approaches were taken: (i) ablation of the Th2 development by using IL-4 gene knockout (IL-4−/−) mice, and (ii) induction of a Th1 response by using recombinant IL-12.

IL-4−/− mice do not develop severe keratitis compared with wild-type animals (59). Surprisingly, although they lack IL-4, these mice continue to produce Th2 cytokines, since antigen-specific splenocytes from these animals produced similar levels of IL-5 to those from wild-type animals and IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13 gene expression in corneas was unchanged (58) (Fig. 4). Since significantly fewer inflammatory cells, including eosinophils, were observed in the cornea (Fig. 5), the diminished keratitis in IL-4−/− mice indicates that the regulatory effect of IL-4 is at the level of cell recruitment to the cornea.

FIG. 4.

IL-4 gene knockout (IL-4−/−) mice, which have diminished keratitis compared with immunocompetent IL-4−/− mice, continue to express other Th2-associated cytokines (IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13). The animals were immunized subcutaneously, injected intrastromally with O. volvulus antigens, and sacrificed at the indicted times postinjection. Corneas pooled from five mice per group were processed by reverse transcription-PCR with cytokine-specific primers and compared with the housekeeping gene HPRT. IL-5 and IFN-γ were also secreted in vitro by lymphoid cells from IL-4−/− mice. Reprinted from reference 58 with permission of the publisher.

FIG. 5.

IL-4 regulates inflammatory cell recruitment to the cornea. (A) IL-4+/+ mice, which develop severe keratitis, have extensive stromal edema and inflammatory cell infiltration, notably by eosinophils, 1 week after intrastromal injection. Note also the presence of blood vessels. (B) In contrast, corneas from similarly treated IL-4−/− mice did not develop keratitis, had no stromal edema, and had minimal cellular infiltration. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Magnification, ×400. Reprinted from reference 58 with permission of the publisher.

Studies with recombinant IL-12 also provide evidence for a relationship between severity of disease and inflammatory cell recruitment to the cornea. IL-12 is a monokine with pleiotropic effects, including the ability to induce a Th1-like response via induction of IFN-γ secretion by T cells and NK cells (11, 28, 40). Administration of recombinant IL-12 during initial sensitization to O. volvulus antigen skewed the in vitro cytokine response from a Th2-like profile to a Th1-like profile (60). Gene expression in the corneas of IL-12-treated mice reflected this modulation, with increased expression of IFN-γ and decreased expression of IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13. Despite this shift, systemic administration of IL-12 resulted in exacerbated corneal pathology, with increased infiltration of inflammatory cells, notably eosinophils, into the corneal stroma. Therefore, as with IL-4−/− mice, the effect of IL-12 modulation on the severity of onchocercal keratitis appears to be at the level of cell recruitment.

Eosinophils are the predominant inflammatory cells in the cornea after injection of soluble parasite antigens into the corneal stroma, and several lines of evidence implicate eosinophils in pathogenesis. The severity of keratitis observed in the experiments cited above correlated with the number of eosinophils in the cornea; i.e., IL-4−/− mice developed less severe keratitis than did control animals, and significantly fewer eosinophils were present in the corneas of IL-4−/− mice (58, 59). Conversely, systemic administration of recombinant IL-12 resulted in exacerbated keratitis, which was associated with increased numbers of eosinophils in the cornea (60).

Eosinophils can damage host cells by release of cytotoxic mediators including membrane lipids and granule proteins such as major basic protein (MBP), eosinophil cationic protein, and eosinophil peroxidase (31). Eosinophils have been detected in the corneas of individuals with ocular onchocerciasis (53), and extracellular MBP has been observed in adjacent conjunctival tissue of infected individuals (8). In vitro studies have demonstrated that MBP also has a direct cytotoxic effect on cultured human corneal epithelial cells (75) and inhibits corneal wound healing (76).

Although eosinophils are strongly associated with the development of keratitis, recent studies indicate that neutrophils can also mediate onchocercal keratitis. Temporal analysis of the cellular response to O. volvulus antigens indicated that although eosinophils were the most prominent inflammatory cells at the time of maximal keratitis, there was also an infiltrate of neutrophils that peaked at an earlier time point (Fig. 6) (56). Mice deficient in IL-5 (which is essential for the development and maturation of eosinophils) still developed corneal opacification comparable in severity to that in immunocompetent mice. While the clinical responses in these strains of mice are equivalent, temporal analysis revealed that histologically, the nature of the cellular infiltrate is distinct. The early inflammatory response in the cornea is similar in both strains of mice, where neutrophils are the predominant cell type recruited. However, whereas the neutrophils are replaced by an influx of eosinophils in the corneas of immunocompetent mice, eosinophils are rarely detected and the number of neutrophils remains elevated in the corneas of IL-5−/− mice. These data indicate that in the absence of eosinophils, neutrophils are clearly associated with clinical pathology induced by O. volvulus antigens. These studies demonstrate that neutrophils, together with T cells and eosinophils, contribute to the development of onchocercal keratitis.

FIG. 6.

Neutrophils infiltrate the cornea before eosinophils do. C57BL/6 mice were sacrificed at the indicated times after intrastromal injection, eyes were immersed in formalin, and adjacent 5-μm paraffin sections were immunostained with antisera to eosinophil MBP or with anti-neutrophil MAb 7/4. Reprinted from reference 56 with permission of the publisher.

The biphasic infiltration of neutrophils and eosinophils in response to O. volvulus antigen indicates that recruitment of cells from the vasculature to the corneal stroma is critical in the development of disease. The process of extravasation involves a complex series of events in which inflammatory cells form an initial low-avidity, selectin-mediated interaction with vascular endothelial cells, resulting in “rolling” along the endothelial cell layer. Upon further activation, higher-affinity integrin-mediated binding is initiated and cells migrate through the endothelial-cell barrier and into the tissue following a chemotactic gradient (42).

Chemokines are a family of chemotactic cytokines that have selective activities for cells based on the expression of receptors (2). Recent studies have explored the role of chemokines in other models of corneal inflammation. Neutrophils are prominent after infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa and herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1). Development of Pseudomonas keratitis has recently been shown to be associated with elevated gene expression of multiple chemokines, including eotaxin, IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, MIP-2, and RANTES (39). In herpes simplex keratitis, at least two chemokines are critical in neutrophil migration, since expression of MIP-2 and MIP-1α closely correlates with increased numbers of neutrophils into the cornea (78). Furthermore, in mice that are deficient in MIP-1α, infiltration of CD4+ cells is abrogated and recruitment of neutrophils is reduced by >80% in response to HSV-1 infection (77). Opacification is also significantly reduced in these animals compared to controls, consistent with the role of neutrophils in this disease. MIP-2 depletion also resulted in significant reduction in neutrophil migration to the cornea in HSV-1-infected mice (84).

Two sets of studies support the notion that chemokines are also involved in the pathogenesis of onchocercal keratitis. First, gene expression of chemokines with activity for eosinophils and mononuclear cells is up-regulated in IL-12-treated mice, consistent with increased cell recruitment and the development of exacerbated keratitis (60). Second, significantly fewer eosinophils are present in the corneas of eotaxin gene knockout mice than in the corneas of wild-type mice after intrastromal injection of parasite antigens (Fig. 7) (63). These data indicate that eotaxin contributes to recruitment of eosinophils into the cornea in response to parasite antigens. The role of eotaxin is especially interesting since, unlike other chemokines with activity for eosinophils, eotaxin appears to activate cells exclusively through a single receptor (CCR3), which to date has been identified only on eosinophils and subsets of T helper cells with a type 2 phenotype (64, 65). Since the tools for investigating the role of various chemokines have only recently become available, studies to date have focused on the factors mentioned above. Other chemokines mediating eosinophil and neutrophil recruitment to the cornea in onchocercal keratitis have yet to be identified.

FIG. 7.

The CC chemokine eotaxin contributes to eosinophil recruitment in onchocercal keratitis. Corneas from eotaxin−/− and immunocompetent wild-type mice were immunostained with antisera to eosinophil MBP after subcutaneous and intrastromal injection of O. volvulus antigens. Data points represent individual animals from two separate experiments. Horizontal lines denote means. Adapted from reference 63 with permission of the publisher.

Recruitment of specific cell types also suggests that there is selective expression of adhesion molecules mediating attachment to the vascular endothelium and facilitating transmigration into the tissue in response to a chemotactic gradient. In herpes simplex keratitis, neutrophil migration is dependent on elevated expression of the integrin receptor platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (PECAM-1) on vascular endothelial cells; this expression is tightly regulated by IFN-γ (73). Temporal recruitment of neutrophils and eosinophils into the cornea in O. volvulus models suggests that there is also selective expression of adhesion molecules in onchocercal keratitis. Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) is important in eosinophil recruitment and is up-regulated by IL-4 (49, 50, 66). Differential expression of PECAM-1 and VCAM-1 may also contribute to temporal recruitment of neutrophils and eosinophils to the cornea in onchocercal keratitis, especially as IL-4 is important in the development of corneal pathology.

CONCLUSION

Collectively, the data obtained from experimental models, together with the information available from infected individuals, suggest a sequence of events leading to the development of onchocercal keratitis (Fig. 8). Sensitization by chronic exposure to parasite antigens leads to the development of a systemic Th2 response, including IL-4, which stimulates B-cell production of antibodies, and IL-5, which stimulates eosinophil production and activation. The effector stage is initiated after the release of parasite antigens into the cornea (either from live worms entering and dying or after injection of soluble O. volvulus antigens). This triggers a cascade of events resulting in secretion of chemokines such as eotaxin and RANTES and in elevated expression of adhesion molecules on vascular endothelial cells. These factors induce circulating neutrophils and eosinophils to adhere to limbal vessels and to migrate into the corneal stroma via a chemokine gradient. In addition to stimulating B-cell activation, IL-4 enhances the recruitment of eosinophils, possibly by up-regulating VCAM-1 expression. IL-12, although modulating the Th response to O. volvulus antigens, also elevates chemokine expression and stimulates inflammatory cell recruitment to the cornea. Upon contact with parasite antigens in the cornea, surface-bound immunoglobulin molecules are cross-linked, signaling these inflammatory cells to degranulate. The cytotoxic effect of eosinophil and neutrophil granule proteins disrupts the normal function of resident cells that are critical for maintaining corneal clarity, resulting in corneal opacification.

FIG. 8.

Proposed sequence of events for development of onchocercal keratitis based on studies with a murine model. Systemic exposure to O. volvulus (O.v.) antigens selectively induces a Th2 response, with production of IL-4 and IL-5. The presence of parasite antigens in the cornea stimulates the recruitment of neutrophils and eosinophils into the cornea. The presence of antibody (Ab) at that site probably causes degranulation of these inflammatory cells, leading to disruption of stromal function and loss of corneal clarity (refer to the text for details).

Factors that lead to corneal neovascularization and to fibrosis are less clear. Also, the roles of T cells and neutrophils as effector and regulatory cells within the corneal stroma will be areas for further investigation.

In addition to inflammatory cell recruitment, chemokines have other immunoregulatory properties. Not only can cytokines regulate chemokine synthesis, but also there is evidence that chemokines can effect T-cell differentiation, thereby regulating T helper cell cytokine production. For example, when naive T cells purified from T-cell-receptor transgenic mice are cultured in the presence of MCP-1, they are induced to secrete IL-4 (38). Conversely, when cultured in the presence of antigen and MIP-1α, T cells are induced to secrete IFN-γ. These data indicate that chemokines play a role in the induction of Th responses. In addition, studies with human Th1 and Th2 cell lines have demonstrated selective expression of chemokine receptors, indicating that chemokines can regulate differential recruitment of functional T-cell subsets (44, 64, 65). Furthermore, C-X-C chemokines that target neutrophils and have the N-terminal ELR motif (Glu-Leu-Arg) have been shown to promote angiogenesis (71). This attribute may be of particular interest in onchocercal keratitis, since corneal neovascularization is a prominent feature in clinical disease. Although there is no direct evidence for production of angiogenic factors by the parasites themselves, there are numerous vessels in the onchocercoma where adult worms reside (69).

Another mechanism that can regulate inflammatory-cell recruitment is programmed cell death, or apoptosis, notably via the Fas/Fas ligand apoptotic pathway. Fas ligand is expressed on ocular tissue (34), including the cornea, and is critical in corneal allografts by inducing apoptosis in Fas+ inflammatory cells infiltrating into the cornea (72). A role for this pathway has also been shown in herpes simplex keratitis. Injection of HSV-1 into the anterior chamber of mice deficient in Fas ligand leads to an exacerbated inflammatory response compared to that in immunocompetent mice (34). The fate of neutrophils in immunocompetent mice in experimental onchocerciasis has yet to be explained. Further studies directed at immunological intervention should include induction of apoptosis and interference with the interactions that mediate inflammatory-cell recruitment to the cornea.

Observations that a minority of individuals in areas of endemic infection have no sign of infection provides circumstantial evidence for naturally acquired resistance (20, 21, 81). Given these findings, a number of studies have examined the immune responses underlying acquired resistance to infective-stage larvae and microfilariae. In a model in which resistance to infective-stage larvae (L3) is induced by immunization with irradiated parasites, protection is dependent on IL-4 and IL-5, and eosinophils are associated with degenerating parasites (41). An essential role for IL-4 in the protective response to L3 larvae was further supported by a recent study with IL-4−/− mice (37). Similarly, acquired resistance to O. lienalis microfilariae is IL-5 and eosinophil dependent (24). Interestingly, IL-4 is not required for the development of resistance to the microfilarial stage, since IL-4−/− mice continue to produce IL-5, and resistance in these animals remains IL-5 dependent (35, 36).

Bianco and coworkers suggest that induction of resistance, but not immunopathology, may depend on being able to stimulate IL-5 without stimulating IL-4 (36). Taken together with observations that some regions of individual O. volvulus proteins, such as protein disulfide isomerase, are more likely to induce keratitis than others (55), further directions aimed at vaccine development without pathogenesis may require manipulation of both the host immune response and parasite proteins.

In conclusion, onchocerciasis continues to be an important public health problem. An increased understanding of the immune systems mechanisms underlying pathogenesis and acquired resistance may lead to further strategies for disease prevention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We express our gratitude to David Freedman for permission to publish their findings. We also thank Jamie Albright, Eugenia Diaconu, Fred Hazlett, and Alan Higgins for their expert technical assistance and Fred Heinzel, Charles King, and Richard Silver for critical review of the manuscript.

The work presented from our laboratory was supported by NIH grants EY10320 (E.P.), EY06913 (L.R.H.), and EY11373 and Burroughs Wellcome New Investigator Award 0720 (E.P.). Funding was also provided by the Research to Prevent Blindness Foundation, and by the Ohio Lions Eye Research Foundation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abiose A. Onchocercal eye disease and the impact of Mectizan treatment. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1998;92:S11–S22. doi: 10.1080/00034989859519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baggiolini M, Dewald B, Moser B. Interleukin-8 and related chemotactic cytokines—CXC and CC chemokines. Adv Immunol. 1994;55:97–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reference deleted.

- 4.Breton B, Diagne M, Wanji S, Bougnoux M, Chandre F, Marechal P, Petit G, Vuong P, Bain O. Ivermectin and moxidectin in two filiarial systems: resistance of Monanema martini; inhibition of Litomosoides sigmodontis insemination. Parasitologia. 1997;39:19–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chakravarti B, Herring T A, Lass J H, Parker J S, Bucy R P, Diaconu E, Tseng J, Whitfield D R, Greene B M, Chakravarti D N. Infiltration of CD4+ T cells into cornea during development of Onchocerca volvulus-induced experimental sclerosing keratitis in mice. Cell Immunol. 1994;159:306–314. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1994.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakravarti B, Lagoo-Deenadayalan S, Parker J S, Whitfield D R, Lagoo A, Chakravarti D N. In vivo molecular analysis of cytokines in a murine model of ocular onchocerciasis. I. Up-regulation of IL-4 and IL-5 mRNAs and not IL-2 and IFN gamma mRNAs in the cornea due to experimental interstitial keratitis. Immunol Lett. 1996;54:59–64. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(96)02648-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakravarti B, Lass J H, Diaconu E, Bardenstein D S, Roy C E, Herring T A, Chakravarti D N, Greene B M. Immune-mediated Onchocerca volvulus sclerosing keratitis in the mouse. Exp Eye Res. 1993;57:21–27. doi: 10.1006/exer.1993.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan C, Li Q, Brezin A, Whitcup S, Egwuagu C, Ottesen E, Nussenblatt R. Immunopathology of ocular onchocerciasis. Th-2 helper T cells in the conjunctiva. Ocular Immunol Inflammation. 1993;1:71–77. doi: 10.3109/09273949309086541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan C, Ottesen E, Awadzi K, Badu R, Nussenblatt R. Immunopathology of ocular onchocerciasis. I. Inflammatory of cells infiltrating the anterior segment. Clin Exp Immunol. 1989;77:367–372. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan C-C, Nussenblatt R, Kim M, Palestine A, Awadzi K, Ottesen E. Immunopathology of ocular onchocerciasis. 2. Anti-retinal autoantibodies in serum and ocular fluids. Ophthalmology. 1987;94:439–443. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(87)33452-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan S, Perussia B, Gupta J, Kobayashi M, Pospisil M, Young H, Wolf S, Young D, Clark S, Trinchieri G. Induction of interferon-γ production by natural killer cell stimulatory factor: characterization of the responder cells and synergy with other inducers. J Exp Med. 1991;173:869. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.4.869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connor D H, Chandler F W, Manz H J, Schwartz D A, Lack E E. Pathology of infectious disease. II. Stamford, Conn: Appleton & Lange; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dadzie K, Remme J, Baker R, Rolland A, Thylefors B. Ocular onchocerciasis and intensity of infection in the community. III. West African rainforest foci of the vector Simulium sanctipauli. Trop Med Parasitol. 1990;41:376–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dadzie K, Remme J, Rolland A, Thylefors B. Ocular onchocerciasis and intensity of infection in the community. II. West African rainforest foci of the vector Simulium yahense. Trop Med Parasitol. 1989;40:348–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doetze A, Erttmann K D, Gallin M Y, Fleischer B, Hoerauf A. Production of both IFN-gamma and IL-5 by Onchocerca volvulus S1 antigen-specific CD4+ T cells from putatively immune individuals. Int Immunol. 1997;9:721–729. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.5.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donnelly J J, Rockey J H, Bianco A E, Soulsby E J L. Aqueous humor and serum IgE antibody in experimental ocular infection of guinea pigs. Ophthalmic Res. 1983;15:61–67. doi: 10.1159/000265237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donnelly J J, Rockey J H, Bianco A E, Soulsby E J L. Ocular immunopathologic findings of experimental onchocerciasis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:628–634. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1984.01040030500036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duke B O, Anderson J. A comparison of the lesions produced in the cornea of the rabbit eye by microfilariae of the forest and Sudan-savanna strains of Onchocerca volvulus from Cameroon. I. The clinical picture. Z Tropenmed Parasitol. 1972;23:354–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duke B O, Garner A. Reactions to subconjunctival inoculation of Onchocerca volvulus microfilariae in pre-immunized rabbits. Tropenmed Parasitol. 1975;26:435–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elson L, Calvopina H, Paredes W, Araujo E, Bradley J, Guderian R, Nutman T. Immunity to onchocerciasis: putative immune persons produce a Th-1 like response to Onchocerca volvulus. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:652–658. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elson L, Guderian R, Araujo E, Bradley J, Days A, Nutman T. Immunity to onchocerciasis: identification of a putatively immune population in a hyperendemic area of Ecuador. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:588–594. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.3.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erttmann K, Meredith S, Greene B, Unnasch T. Isolation and characterization of form specific DNA sequences of O. volvulus. Act Leiden. 1990;59:253–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erttmann K, Unnasch T, Greene B, Albiez E, Boateng J, Denke A, Ferraroni J, Karam M, Schulz-Key H, Williams P. A DNA sequence specific for forest form Onchocerca volvulus. Nature. 1987;327:415–417. doi: 10.1038/327415a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folkard S, Hogarth P, Taylor M, Bianco A. Eosinophils are the major effector cells of immunity to microfilariae in a mouse model of onchocerciasis. Parasitology. 1996;112:323–329. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000065847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallin M, Edmonds K, Ellner J J, Erttmann K D, White A T, Newland H S, Taylor H R, Greene B M. Cell-mediated immune responses in human infection with Onchocerca volvulus. J Immunol. 1988;140:1999–2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gallin M Y, Murray D, Lass J H, Grossniklaus H E, Greene B M. Experimental interstitial keratitis induced by Onchocerca volvulus antigens. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106:1447–1452. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060140611033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garner A, Duke B, Anderson J. A comparison of the lesions produced in the cornea of the rabbit eye by microfilariae of the forest and Sudan-savanna strains of Onchocerca volvulus from Cameroon. Z Tropenmed Parasitol. 1973;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Germann T, Gately M, Schoehaut D, Lohoff M, Mattner F, Fischer S, Jin S-C, Schmitt E, Rude E. Interleukin-12/T cell stimulating factor, a cytokine with multiple effects on T helper type 1 (Th1) but not Th2 cells. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:1762. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gill J, Kerr C, Shoop W, Lacey E. Evidence of multiple mechanisms of avermectin resistance in haemonchus contortus—comparison of selection protocols. Int J Parasitol. 1998;28:783–789. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(98)00015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gill J, Lacey E. Avermectin/milbemycin resistance in trichostrongyloid. Int J Parasitol. 1998;28:863–877. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(98)00068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gleich G J, Adolphson C R, Leiferman K M. The biology of the eosinophilic leukocyte. Annu Rev Med. 1993;44:85–101. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.44.020193.000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greene B M. Primate models for onchocerciasis research. Ciba Found Symp. 1987;127:236–243. doi: 10.1002/9780470513446.ch16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greene B M, Fanning M M, Ellner J J. Non-specific suppression of antigen-induced lymphocyte blastogenesis in Onchocerca volvulus infection in man. Clin Exp Immunol. 1983;52:259–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griffith T, Brunner T, Fletcher S, Green D, Ferguson T. Fas ligand-induced apoptosis as mechanism of immune privilege. Science. 1995;270:1189–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5239.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hogarth P, Folkard S, Taylor M, Bianco A. Accelerated clearance of Onchocerca microfilariae and resistance to re-infection in interleukin-4 gene-knockout mice. Parasite Immunol. 1995;17:653–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1995.tb01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hogarth P, Taylor M, Bianco A. IL-5-dependent immunity to microfilariae is independent of IL-4 in a mouse model of onchocerciasis. J Immunol. 1998;160:5436–5440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson E, Schynder-Candrian S, Rajan T, Nelson F, Lustigman S, Abraham D. Immune responses to third stage larvae of Onchocerca volvulus in interferon-gamma and interleukin-4 knockout mice. Parasite Immunol. 1998;20:319–324. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1998.00148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karpus W, Lukacs N, Kennedy K, Smith W, Hurst S, Barrett T. Differential CC chemokine-induced enhancement of T helper cell cytokine production. J Immunol. 1997;158:4129–4136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kernacki K, Goebel D, Poosch M, Hazlett L. Early cytokine and chemokine gene expression during Pseudomonas aeruginosa corneal infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66:376–379. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.376-379.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kobayashi M, Fitz L, Ryan M, Hewick R, Clark S, Chan S, Loudon R, Sherman F, Perussia B, Trinchieri G. Identification and purification of natural killer cell stimulatory factor (NKSF), a cytokine with multiple biological effects on human lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1989;170:827–845. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.3.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lange A, Yutanawiboonchai W, Scott P, Abraham D. IL-4- and IL-5-dependent immunity to Onchocerca volvulus infective larvae in BALB/cBYJ mice. J Immunol. 1994;153:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lawrence M, Springer T. Leukocytes roll on a selection at physiological flow rates: distinction from and pre-requisite for adhesion through integrins. Cell. 1991;68:859–873. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90393-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Limaye A P, Abrams J S, Silver J E, Awadzi K, Francis H F, Ottesen E A, Nutman T B. Interleukin-5 and the post-treatment eosinophilia in patients with onchocerciasis. J Clin Investig. 1991;88:1418–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI115449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loetscher P, Uguccioni M, Bordoli L, Baggiolini M, Moser B. CCR5 is characteristic of Th1 lymphocytes. Nature. 1998;391:344–345. doi: 10.1038/34814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCarthy J, Ottesen E A, Nutman T. Onchocerciasis in endemic and nonendemic populations: differences in clinical presentation and immunologic findings. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:736–741. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.3.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McKechnie N, Braun G, Connor V, Klager S, Taylor D, Alexander R, Gilbert C. Immunologic cross-reactivity in the pathogenesis of ocular onchocerciasis. Investig Ophthalmol Visual Sci. 1993;34:2888–2902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McKechnie N M, Gurr W, Braun G. Immunization with the cross-reactive antigens OV39 from Onchocerca volvulus and the hr44 from human retinal tissue induces ocular pathology and activates retinal microglia. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1334–1343. doi: 10.1086/514130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Molyneux D. Onchocerciasis control in west Africa: current status and future of the onchocerciasis control programme. Parasitol Today. 1995;11:399–402. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moser R, Fehr J, Bruijnzeel P L. IL-4 controls the selective endothelium-driven transmigration of eosinophils from allergic individuals. J Immunol. 1992;149:1432–1438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moser R, Groscurth P, Carballido J M, Bruijnzeel P L, Blaser K, Heusser C H, Fehr J. Interleukin-4 induces tissue eosinophilia in mice: correlation with its in vitro capacity to stimulate the endothelial cell-dependent selective transmigration of human eosinophils. J Lab Clin Med. 1993;122:567–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murdoch I, Jones B, Cousens S, Liman I, Babalola O, Daude J, Abiose A. Visual field constriction as a cause of blindness or visual impairment. Bull W H O. 1997;75:141–146. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ottesen E. Immune responsiveness and the pathogenesis of human onchocerciasis. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:659–671. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paul E, Zimmerman L. Some observations on the ocular pathology of onchocerciasis. Hum Pathol. 1970;1:581–594. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(70)80058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pearlman E. Experimental onchocercal keratitis. Parasitol Today. 1996;12:261–267. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(96)10026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pearlman E, Diaconu E, Hazlett F, Jr, Merriweather A, Unnasch T. Identification of an epitope of a recombinant Onchocerca volvulus protein that induces corneal pathology. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;89:123–135. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pearlman E, Hall L R, Higgins A W, Bardenstein D S, Diaconu E, Hazlett Jr F E, Albright J L, Kazura J W, Lass J H. The role of eosinophils and neutrophils in helminth-induced keratitis. Investig Ophthalmol Visual Sci. 1998;39:1176–1182. . (Erratum [color micrograph], 39:1641.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pearlman E, Lass J. Keratitis due to onchocerciasis. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 1994;7:641–648. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pearlman E, Lass J, Bardenstein D, Diaconu E, Hazlett F E, Albright J, Higgins A, Kazura J. Onchocerca volvulus-mediated keratitis: cytokine production by IL-4-deficient mice. Exp Parasitol. 1996;84:274–281. doi: 10.1006/expr.1996.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pearlman E, Lass J, Bardenstein D, Kopf M, Hazlett F E, Diaconu E, Kazura J. Interleukin 4 and T helper type 2 cells are required for development of experimental onchocercal keratitis (river blindness) J Exp Med. 1995;182:931–940. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.4.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pearlman E, Lass J H, Bardenstein D S, Hazlett F E, Albright J L, Diaconu G, Kazura J W. IL-12 exacerbates helminth-mediated corneal pathology by augmenting cell recruitment and chemokine expression. J Immunol. 1997;158:827–833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Plier D, Awadzi K, Freedman D. Immunoregulation in onchocerciasis: persons with ocular inflammatory disease produce a Th2-like response to Onchocerca volvulus antigen. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:380–386. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.2.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Remme J. The African programme for onchocerciasis control: preparing to launch. Parasitol Today. 1995;11:403–406. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rothenberg M E, MacLean J A, Pearlman E, Leder P. Targeted disruption of the chemokine eotaxin partially reduces peripheral blood and antigen induced tissue eosinophil. J Exp Med. 1997;185:785–790. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sallusto F, Lenig D, Mackay C, Lanzavecchia A. Flexible programs of chemokine receptor expression on human polarized T helper 1 and 2 lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1998;187:875–883. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.6.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sallusto F, Mackay C, Lanzavecchia A. Selective expression of the eotaxin receptor CCR3 by human T helper 2 cells. Science. 1997;277:2005–2007. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schleimer R P, Sterbinsky S A, Kaiser J, Bickel C A, Klunk D A, Tomioka K, Newman W, Luscinskas F W, Gimbrone M J, McIntyre B W. IL-4 induces adherence of human eosinophils and basophils but not neutrophils to endothelium. Association with expression of VCAM-1. J Immunol. 1992;148:1086–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schulz-Key H. Observations on the reproductive biology of Onchocerca volvulus. Acta Leiden. 1990;59:27–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Semba R, Murphy R, Newland H, Awadzi K, Greene B, Taylor H. Longitudinal study of lesions of the posterior segment in onchocerciasis. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1334–1341. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32413-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Smith R J, Cotter T P, Williams J F, Guderian R H. Vascular perfusion of Onchocerca volvulus nodules. Trop Med Parasitol. 1988;39(Suppl. 4):418–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Steel C, Nutman T. Regulation of IL-5 in onchocerciasis. A critical role for IL-2. J Immunol. 1993;150:5511–5518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Strieter R, Polverini P, Kunkel S, Arenberg D, Burdick M, Kasper J, Dzuiba J, Van Damme J, Walz A, Marriott D, Chan S-Y, Roczniak S, Shanafelt A. The functional role of the ELR motif in CXC chemokine-mediated angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:27348–27357. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stuart P, Griffith T, Usui N, Pepose J, Yu X, Ferguson T. CD95 ligand (FasL)-induced apoptosis is necessary for corneal allograft survival. J Clin Investig. 1997;99:396–402. doi: 10.1172/JCI119173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tang Q, Hendricks R. Interferon gamma regulates platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 expression and neutrophil infiltration into herpes simplex virus-infected mouse corneas. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1435–1447. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Toe L, Tang J, Back C, Katholi C, Unnasch T. Vector-parasite transmission complexes for onchocerciasis in West Africa. Lancet. 1997;349:163–166. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)05265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Trocme S, Hallberg C, Gill K, Gleich G, Tyring S, Brysk M. Effects of eosinophil granule proteins on human corneal epithelial cell viability and morphology. Investig Ophthalmol Visual Sci. 1997;38:593–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Trocme S D, Gleich G J, Kephart G M, Zieske J D. Eosinophil granule major basic protein inhibition of corneal epithelial wound healing. Investig Ophthalmol Visual Sci. 1994;35:3051–3056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tumpey T, Cheng H, Cook D, Smithies O, Oakes J, Lausch R. Absence of macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha prevents the development of blinding herpes stromal keratitis. J Virol. 1998;72:3705–3710. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3705-3710.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tumpey T, Cheng H, Yan X, Oakes J, Lausch R. Chemokine synthesis in the HSV-1 infected cornea and its suppression by interleukin-10. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;63:486–492. doi: 10.1002/jlb.63.4.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78a.van den Berghe L, Chardome M, Peel E. The filarial parasites of the Eastern gorilla in the Congo. J Helminthol. 1964;38:349–368. doi: 10.1017/s0022149x00033903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Van der Lelij A, Rothova A, Stilma J, Hoekzema R, Kijlstra A. Cell-mediated immunity against human retinal extract, S-antigen, and interphotoreceptor retinoid binding protein in onchocercal chorioretinopathy. Investig Ophthalmol Visual Sci. 1990;31:2031–2036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Van der Lelij A, Rothova A, Stilma J, Vetter J, Hoekzema R, Kijlstra A. Humoral and cell-mediated immune response against human retinal antigens in relation to ocular onchocerciasis. Acta Leiden. 1990;59:271–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ward D, Nutman T, Zea-Flores G, Pottocarrero C, Lujan A, Ottesen E. Onchocerciasis and immunity in humans: enhanced T cell responsiveness to parasite antigen in putatively immune individuals. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:536–543. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.3.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.World Health Organization. Onchocerciasis and its control. WHO Tech Rep Ser. 1995;852:1–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xu M, Molento M, Blackhall W, Ribeiro P, Beech R, Prichard R. Ivermectin resistance in nematodes may be caused by alteration of P-glycoprotein homolog. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;91:327–335. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(97)00215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yan X-T, Tumpey T, Kunkel S, Oakes J, Lausch R. MIP-2 is more potent than KC at inducing neutrophil migration and tissue injury in the HSV-1 infected cornea. Investig Ophthalmol Visual Sci. 1998;39:1854–1862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zimmerman P, Dadzie K, De Sole G, Remme J, Soumbey Alley E, Unnasch T. Onchocerca volvulus DNA probe classification correlates with epidemiologic patterns of blindness. J Infect Dis. 1992;165:964–968. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.5.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]