Abstract

Patient: Female, 54-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Gastric antral vascular ectasia

Symptoms: Anemia

Clinical Procedure: Endoscopic argon plasma coagulation • laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy

Specialty: Gastroenterology and Hepatology • Surgery

Objective:

Unknown etiology

Background:

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) is a rare clinical entity that presents with acute upper-gastrointestinal bleeding or chronic anemia. It is characterized by endoscopic watermelon appearance of the stomach. It is usually associated with other comorbidities; however, few articles have previously described GAVE in patients with end-stage renal disease. Its management is controversial, and endoscopic management is considered the treatment of choice.

Case Report:

A middle-age female patient, on regular hemodialysis for ESRD, was referred to the surgical out-patient clinic as a refractory GAVE after failure of endoscopic management as she became blood transfusion-dependent. She underwent laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy with a Billroth II reconstruction of gastrojejunostomy. She had a smooth postoperative course and was followed up in the clinic for 12 months with no complications. Her hemoglobin level was stable at 9.4 g/dL without further blood transfusion.

Conclusions:

Gastric antral vascular ectasia is usually associated with other comorbidities; however, an association between GAVE and CKD is rare. Its management is controversial, and endoscopic management is considered the preferred method of treatment. Laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy is an effective management modality for GAVE, with dramatic improvement and good outcomes in terms of bleeding, blood transfusion requirements, and nutritional status.

Keywords: Blood Transfusion; Gastric Antral Vascular Ectasia; Gastric Bypass; Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic

Background

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) is a rare clinical entity accounting for 4% of non-variceal upper-gastrointestinal bleeding. It is characterized by endoscopic watermelon appearance of the stomach [1–3]. Typically, it is presented by upper-gastrointestinal bleeding leading to chronic anemia [4,5]. GAVE is usually associated with various comorbidities. However, few articles have previously described GAVE in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

Herein, we describe a successful surgical management of a middle-aged woman on regular hemodialysis for ESRD who became a blood transfusion-dependent and was found to have GAVE.

Case Report

A 54-year-old female patient was referred to the upper-gastrointestinal surgery clinic as a case of GAVE refractory to endoscopic management. She was known to have ESRD, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension. She had been on hemodialysis for 6 years. A year prior to presentation, she became blood transfusion-dependent with a baseline hemoglobin level of 4.5–6.1 g/dL, receiving 1 unit of packed RBCs during each dialysis session.

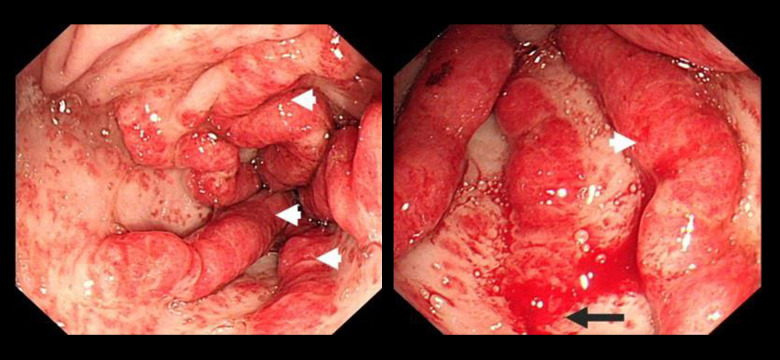

She underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonos-copy, which revealed a typical watermelon appearance of the stomach, with prominent erythematous folds in the antrum, features suggestive of GAVE (Figure 1). She was managed by endoscopic argon plasma coagulation (APC) that was repeated 3 times, with no noticeable clinical or endoscopic improvement.

Figure 1.

Endoscopic view of the stomach showing the classical watermelon appearance with prominent erythematous tortous folds in the antrum suggestive of GAVE. The white arrowhead indicates the tortous prominent folds and the black arrow shows a site of bleeding.

Upon presentation to the surgical clinic, she was pale and undernourished, with bilateral lower-limb edema. Laboratory test results were significant for normocytic normochromic anemia and positive occult blood in the stool. Renal function tests were typical for ESRD. Other lab results, including liver function test and coagulation profile, were unremarkable.

After thorough counseling, she underwent a laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy with a Billroth II reconstruction of gastrojejunostomy. Under general anesthesia, she was placed in a supine anti-Trendelenburg position. Diagnostic laparoscopy showed small amounts of ascites, with a huge fatty liver. The stomach was dissected from the mid-body downward to the pylorus using a sealing device, starting with the greater omentum followed by the lesser omentum. The stomach was transected 1 cm proximal to the pylorus and at the level of the mid-body. Gastrojejunostomy was then performed 60 cm distal to the duodeno-jejunal junction. The blood loss was minimal (around 50 milliliters). The total procedure duration was 115 minutes.

The patient had a smooth postoperative course. A water-soluble study on the third postoperative day excluded leakage. Gradually, she started oral intake and was eventually discharged home on the seventh postoperative day in good condition. She was followed up in the clinic for 1 year with no concerns and good nutritional status. Her hemoglobin level was stable at 9.4 g/dL without further blood transfusions. Her albumin level increased from 1.9 g/dL preoperatively to 3.7 g/dL 1 year postoperatively.

Discussion

GAVE is a rare clinical entity with unknown etiology [2,3]. GAVE is usually associated with various systemic diseases, especially autoimmune diseases. Around 30% of patients with GAVE have liver cirrhosis [2]. Other associated systemic diseases include Sjogren’s syndrome, systemic lupus syndrome, systemic sclerosis, Raynaud’s disease, DM, hypertension, acute myeloid leukemia, and bone marrow transplant [6–9]. Rarely, GAVE has been reported in patients with chronic kidney diseases. We performed a literature review using the terms “gastric antral vascular ectasia,” “GAVE,” “watermelon stomach,” “ESRD,” “chronic kidney disease,” “uremia,” and “hemodialysis” in databases of PubMed, Scopus, Medline, and Google scholar and identified 31 cases of GAVE in patients with chronic kidney diseases (Table 1).

Table 1.

Literature review summary including all reported cases with GAVE in patients with CKD from 1996 to 2020.

| Case No. | Year/Author | No. of reported cases | Age/Sex | Presentation | CKD /ESRD 2ry to | Liver diseases | Duration on dialysis before diagnosis of GAVE | Initial Hgb (g/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1996 Yorioka N, et al [12] | 1 | 70/F | Anemia | Chronic pyelonephritis | No | 9 years | 4.1 |

| 2 | 1996 Hermans C, et al [20] | 1 | 63/M | Anemia | Chronic glomerulone- phritis | No | 6 years | 6.3 |

| 3 | 1998 Chien CC, et al [13] | 1 | 50/F | Anemia | NA | No | 5 years | NA |

| 4 | 2000 Fábián G, et al [21] | 1 | 77/F | Anemia | Hypertensive Nephropathy | No | 2 years | 3.6 |

| 5 | 2003Tomori K, et al [14] | 2 | 69/M | Anemia Hematemesis | Hypertensive Nephropathy | No | 6 months | NA |

| 6 | 57/F | Anemia | Hypertensive Nephropathy | No | 2 years | NA | ||

| 7 | 2005 Pljesa S, et al [22] | 1 | 54/F | Anemia Melena | Chronic pyelonephritis | No | 7 years | 4 |

| 8 | 2006 Stefanidis I, et al [23] | 2 | 61/F | Melena Hypotension during dialysis | Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease | No | 10 months | 7.6 |

| 9 | 72/F | Anemia Melena | Chronic interstitial nephritis | No | 2 years (21 months) | NA | ||

| 10 | 2007 George P, et al [24] | 1 | 42/M | Anemia Melena | Chronic glomerulone- phritis Post-renal transplantation (15 years ago) Chronic allograft nephropathy | Decompensated cirrhosis 2 ry to hepatitis B | Post-renal transplantation | 4 |

| 11 | 2009 Nguyen H, et al [4] | 1 | 63/F | Abdominal pain Vomiting Melena | Diabetic and Hypertensive Nephropathy | Chronic hepatitis C infection, Portal HTN | NA | 6.8 |

| 12 | 2010 Lin W-H, et al [25] | 1 | 38/F | Anemia Melena | NA | No | 7 years | NA |

| 13 | 2011 Iguchi A, et al [6] | 3 | 67/F | Anemia | Chronic glomerulonephritis | No | Not on dialysis | 5.8 |

| 14 | 61/F | Anemia Melena | Hepatorenal syndrome | Alcoholic liver cirrhosis | Not on dialysis | 4.8 | ||

| 15 | 66/F | Anemia | Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease | No | Not on dialysis | 4.8 | ||

| 16 | 2012 Lata S, et al [26] | 1 | Middle age/F | Anemia Melena | Hypertensive Nephropathy | Chronic liver disease 2ry to hepatitis C virus | 6 years | 4.3 |

| 17 | 2013 Jinga M, et al [27] | 1 | 42/F | Anemia Abdominal pain | SLE | No | 3 years (40 months) | 6.7 |

| 18 | 2014 Pisharam JK, et al [15] | 4 | 59/F | Anemia | Diabetic Nephropathy | No | 4 years | 8 |

| 19 | 67/M | Anemia Hematemesis | Diabetic Nephropathy | No | 5 years | 5.7 | ||

| 20 | 71/F | Melena | Diabetic Nephropathy | Chronic hepatitis B infection | 2 years | 5.6 | ||

| 21 | 50/F | Anemia | Diabetic Nephropathy | No | 3 years | 8.3 | ||

| 22 | 2014 Ahn Y, et al [5] | 1 | 52/F | Anemia Melena | Diabetic and Hypertensive Nephropathy | Non-alcoholic liver cirrhosis complicated byortal HTN | 2 years | 5.5 |

| 23 | 2014 Kilincalp S, et al [28] | 1 | 54/M | Anemia | Hypertensive Nephropathy Post-renal transplantation (5 years ago) | No | Post-renal transplantation | 5.8 |

| 24 | 2014 Shimamura Y, et al [29] | 1 | 64/F | Anemia UGIB | Diabetic Nephropathy | No | NA | 6.7 |

| 25 | 2015 Lee DJR, et al [16] | 1 | 40/F | Anemia Melena Hematemesis Hypotension during dialysis | Hypertensive Nephropathy | No | 9 years | 4.8 |

| 26 | 2018 Rimševičius L, et al [30] | 4 | 66/F | Anemia Melena | Diabetic and Hypertensive Nephropathy | No | 3 years | 6 |

| 27 | 75/M | Anemia Melena | Hypertensive Nephropathy | No | 5 years | 11.8 | ||

| 28 | 64/M | Anemia | Chronic pyelonephritis | No | 5 years | 9.8 | ||

| 29 | 80/M | Anemia Melena | NA | No | Not on dialysis | 7.7 | ||

| 30 | 2019 Santos S, et al [31] | 1 | 49/M | Anemia Melena | Chronic glomerulonephritis | No | NA | 6.3 |

| 31 | 2020 Kang SH, et al [32] | 1 | 76/F | Anemia Melena Hematemesis | SLE | No | 5 months | 5.5 |

| Case No. | EGD/Colonoscopy finding | Medical management | Endoscopic management | Surgical management | Management outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1st EGD: Superficial erosion in the gastric antrum 2nd EGD: Red linear streaks ascending to the pylorus |

Conservative | No | No | Blood transfusion dependent which improve within 3 months of HD cessation and CAPD initiation |

| 2 | Longitudinal folds of dilated vessels radiating from the pylorus Colonoscopy: Normal | Hormonal therapy (Estrogen and Progesterone) | No | No | Successful |

| 3 | 1st EGD: Antral gastritis 2nd EGD: Typical picture of watermelon stomach |

Hormonal therapy (Norethisterone and Ethynyloestradol) | No | No | Successful |

| 4 | – Some erosions in the corpus of the stomach and slightly protruding, parallel longitudinal antral streaks converging on the pylorus – Two angiodysplastic lesions in the postbulbar duodenum Colonoscopy: – Diffuse atrophic changes of the intestinal mucosa with several angiodysplasias, 5–7 mm in diameter – Some diverticuli in the sigmoid colon |

Hormonal therapy (Estrogen and Progesterone) | No | No | Successful |

| 5 | 1st EGD: oozing in the antrum, and gastritis and esophagitis with sliding hernia 2nd EGD: Typical picture of watermelon stomach |

No | APC | No | Successful |

| 6 | Oozing in the antrum with diffuse vasodilation in the antrum | No | APC | No | Successful |

| 7 | Visible columns of vessels transversing the antrum in longitudinal folds and converging in the pylorus, with clear red spots and surrounding hyperemy covered by drops of fresh blood Colonoscopy: Normal |

No | Sclerotherapy (Electrocoagulation and APC were not available) | Total gastrectomy | Successful |

| 8 | – Characteristic antral appearance of watermelon stomach – Erythematous stripes in the cardia – Diaphragmatic hernia |

No | Electrocoagulation (10 sessions) | No | Successful |

| 9 | Typical watermelon stomach (longitudinal rugal folds transversing the antrum and converging on the pylorus) | No | Laser photocoagulation Electrocoagulation | No | Death* |

| 10 | Portal hypertensive gastropathy with gastric antral vascular ectasia Colonoscopy: Normal |

No | Electrocoagulation (4 sessions) APC | No | Death** |

| 11 | – Esophageal varices and PHG 2 years before GAVE dx Extensive vascular ectasias and patchy erythema in the distal antrum Colonoscopy: Hemorrhoids |

No | Not tried due to diffuse and advanced vascular ectasias | Subtotal gastrectomy | Successful |

| 12 | – Multiple esophageal ulcers, gastric ulcers, and gastritis. before GAVE dx – Ectatic vessels along the longitudinal folds of the antrum |

No | APC (5 sessions) | No | Successful |

| 13 | Watermelon stomach at the antrum | No | APC (2 sessions) | No | Successful |

| 14 | Diffuse antral vascular ectasia | No | APC (2 sessions) | No | Successful |

| 15 | Watermelon stomach | No | APC (3 sessions) | No | Successful |

| 16 | – Multiple linear gastric vascular malformations in the antrum with spurt oozing Ectasias in the cardia and the duodenum Colonoscopy: Normal |

No | APC | No | Successful |

| 17 | Visible columns of red tortuous ectatic vessels along the longitudinal folds of the antrum | No | APC (Multiple sessions) | No | Successful |

| 18 | 1st EGD: – Hemorrhagic antral gastritis with self-limiting oozing 2nd EGD: – Diffuse erythematous patches in the antrum – Vascular ectasia located at the gastro-esophageal junction |

No | Combination of heater probe and coagulation with open snare (2 sessions) – APC was not available | No | Death due to sepsis |

| 19 | 1st EGD: – Gastritis and a fundal polyp 2nd EGD: – Mild esophagitis, some fresh blood in the distal stomach and multiple antral folds with erythematous patches |

No | Thermal coagulation (3 sessions) | No | Death due to sepsis |

| 20 | 1st EGD: – Antral gastritis and few telangiectasias 2nd EGD: – Fresh blood in the antrum with prominent antral folds and gastritis |

No | Adrenaline injection Thermal coagulation | No | Blood transfusion dependent |

| 21 | Two prominent antral folds and 2 linear erythematous streaks | Conservative# | No | No | Successful |

| 22 | Single gastric antral angiodysplastic lesion with hemorrhage and multiple gastric angioectasias with no bleeding | No | APC (Multiple sessions) | Gastrectomy was considered but patient was high risk | Blood transfusion dependent |

| 23 | Raised erythematous stripes radiating from pylorus up to the lower part of gastric body | No | APC (3 sessions) | No | Successful |

| 24 | Red tortuous ectatic vessels along the longitudinal folds of the antrum | No | APC (3 sessions) | No | Successful |

| 25 | 1st EGD: Distal erosive esophagitis and intense antral erosive gastritis 2nd EGD: Longitudinal antral folds containing visible stripes of tortuous red ecstatic vessels with bleeding Colonoscopy: Normal |

No | APC | No | Successful |

| 26 | Multiple linear gastric vascular malformations with signs of bleeding | No | APC | No | Successful |

| 27 | Multiple linear gastric vascular malformations in the antrum, with 3 mm lesions and no signs of bleeding | No | APC | No | Successful |

| 28 | Multiple l ar gastric vascular malformations in the antrum without any signs of bleeding | No | APC | No | Successful |

| 29 | Multiple linear gastric vascular malformations in the antrum with small signs of bleeding | No | APC | No | Successful |

| 30 | Multiple gastric angiodysplasias arranged in radiating streaks with active bleeding | Bevacizumab | APC | No | Successful |

| 31 | Multiple erythematous raised hyperemic mucosal lesions at the distal antrum without active bleeding | No | APC (8 sessions) | No | Blood transfusion dependent |

CKD – chronic kidney disease; ESRD – end-stage renal disease; F – female; M – male; NA – not available.

Patient died from a new stroke;

Patient died later from sepsis;

only managed by Iron and Recombinant Human Erythropoietin.

GAVE is a disease of elderly people, with a female predominance in hepatic patients and male predominance in all other patients. This can be explained by the age and sex distribution of associated comorbidities [10].

Diagnosis of GAVE depends mainly on its characteristic endoscopic features: parallel red stripes of tortuous ectatic vessels, usually located at the antral mucosal folds [11]. Moreover, it may extensively involve the whole stomach, giving a picture of honeycomb stomach, especially in cirrhotic patients [2,10]. However, the absence of the characteristic watermelon appearance does not entirely exclude the presence of GAVE, as the literature review shows that many patients required more than 1 endoscopy to confirm the presence of GAVE. Moreover, 7 cases (22.5%) in the literature review did not report this finding and were diagnosed based on clinical picture [12–16].

Management of GAVE is controversial, including various medical, endoscopic, and surgical management modalities. Several drugs have been tried in such patients, including estrogen and progesterone analogs, octreotide, and pulse steroids [17]. The effectiveness of medical management is questionable, as only 16.1% of patients with GAVE and CKD in our literature review were successfully managed using only a medical approach.

Nowadays, endoscopic management is considered as the plan of choice. Several techniques have been used, including APC, laser, and sclerotherapy. APC is more easily tolerated, with fewer adverse effects, than other endoscopic techniques. Usually, multiple sessions of APC are required to control bleeding.

However, repeated sessions may lead to stenosis, gastric outlet obstruction, or perforation [17].

In general, surgical management for GAVE is considered as a last option after the failure of other management modalities [18]. However, the clinical improvement of patients was much more noticeable after surgical management vs medical or endoscopic management, in the form of a stable hemoglobin level without blood transfusion. Multiple procedures have been reported as partial vs total gastrectomy and gastroesophagectomy [17,19]. In our literature review, only 2 patients (6.5%) underwent surgical management owing to extensive disease or after the failure of non-operative modalities [4,19].

Our patient was dependent on blood transfusion, with an average transfusion of 3 packed RBCs weekly. Initially, she was managed with 3 sessions of endoscopic APC, which failed to improve her anemia or reduce her transfusion requirements. The gastroenterologist referred her to us as a refractory case for endoscopic management. Therefore, surgical management was considered after multidisciplinary meetings owing to failure of the endoscopic management as well as fear of repeated blood transfusion complications. The patient underwent laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy with Billroth II reconstruction. The laparoscopic approach has well-known advantages over the open approach. The histopathological examination was consistent with GAVE. During close follow-up visits, the patient had a stable hemoglobin level and did not require any blood transfusion.

Herein, we highlight the efficacy of surgical management in patients with GAVE. Indeed, the laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy approach may be considered as an effective modality of management, along with endoscopic management, owing to its favorable outcomes, in terms of bleeding, blood transfusion requirements, and nutritional status, with low complication rates if performed in a well-equipped center by an expert laparoscopic surgeon. Further well-designed studies are required to assess the efficacy and outcome of the laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy approach as first-line management for GAVE.

Conclusions

Gastric antral vascular ectasia is a rare clinical entity that presents with acute upper-gastrointestinal bleeding or chronic anemia. It is usually associated with other comorbidities; however, an association between GAVE and CKD is rare. Its management is controversial, and endoscopic management is considered the preferred method of treatment. Laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy is an effective management modality for GAVE, with dramatic improvement and good outcomes in terms of bleeding, blood transfusion requirements, and nutritional status.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

References:

- 1.Gretz J. The watermelon stomach: Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(6):890–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kar P, Mitra S, Resnick JM, et al. Gastric antral vascular ectasia: Case report and review of the literature. Clin Med Res. 2013;11(2):80–85. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2012.1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jin T, Fei B-Y, Zheng W-H, et al. Successful treatment of refractory gastric antral vascular ectasia by distal gastrectomy: A case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(38):14073. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i38.14073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen H, Le C, Nguyen H. Gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach) – an enigmatic and often-overlooked cause of gastrointestinal bleeding in the elderly. Perm J. 2009;13(4):46–49. doi: 10.7812/tpp/09-055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahn Y, Wang T, Dunlop J. Treatment resistant gastric antral vascular ectasia in a patient undergoing haemodialysis. J Ren Care. 2014;40(4):263–65. doi: 10.1111/jorc.12077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iguchi A, Kazama JJ, Komatsu M, et al. Three cases of gastric antral vascular ectasia in chronic renal failure. Case Rep Nephrol Urol. 2011;1(1):15–19. doi: 10.1159/000332832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liberski S, McGarrity T, Hartle R, et al. YAG laser therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40(5):584–87. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(94)70258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takahashi T, Miya T, Oki M, et al. Severe hemorrhage from gastric vascular ectasia developed in a patient with AML. Int J Hematol. 2006;83(5):467–68. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.06052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kopylov U, Yung DE, Engel T, et al. Diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy versus magnetic resonance enterography and small bowel contrast ultra-sound in the evaluation of small bowel Crohn’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49(8):854–63. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Selinger CP, Ang YS. Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE): An update on clinical presentation, pathophysiology and treatment. Digestion. 2008;77(2):131–37. doi: 10.1159/000124339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jabbari M, Cherry R, Lough JO, et al. Gastric antral vascular ectasia: The watermelon stomach. Gastroenterology. 1984;87(5):1165–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yorioka N, Hamaguchi N, Taniguchi Y, et al. Gastric antral vascular ectasia in a patient on hemodialysis improved with CAPD. Perit Dial Int. 1996;16(2):177–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chien C, Fang J, Huang C. Watermelon stomach – an unusual cause of recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a uremic patient receiving estrogen-progesterone therapy: Case report. Changgeng Yi Xue Za Zhi. 1998;21(4):458–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomori K, Nakamoto H, Kotaki S, et al. Gastric angiodysplasia in patients undergoing maintenance dialysis. Adv Perit Dial. 2003;19:136–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pisharam JK, Ramaswami A, Chong VH, Tan J. Watermelon stomach: A rare cause of anemia in patients with end-stage renal disease. Clinical Nephro. 2014;81(1):58–62. doi: 10.5414/CN107527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee DJR, Fragata J, Pestana J, et al. Erythropoietin resistance in end-stage renal disease patient with gastric antral vascular ectasia. J Bras Nefrol. 2015;37:271–74. doi: 10.5935/0101-2800.20150042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu W-H, Wang Y-K, Hsieh M-S, et al. Insights into the management of gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach) Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2018;11:1756283X17747471. doi: 10.1177/1756283X17747471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belle J, Feiler M, Pappas T. Laparoscopic surgical treatment for refractory gastric antral vascular ectasia: A case report and review. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19(5):e189–e93. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181bb5a19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuccio L, Mussetto A, Laterza L, et al. Diagnosis and management of gastric antral vascular ectasia. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5(1):6. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hermans C, Goffin E, Horsmans Y, et al. Watermelon stomach. An unusual cause of recurrent upper GI tract bleeding in the uraemic patient: Efficient treatment with oestrogen-progesterone therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11(5):871–74. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.ndt.a027418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fábián G, Szigeti N, Kovács T, et al. An unusual multiplex cause of severe gastrointestinal bleeding in a haemodialysed patient. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000;15(11):1869–71. doi: 10.1093/ndt/15.11.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pljesa S, Golubovic G, Tomasevic R, et al. “Watermelon stomach” in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Ren Fail. 2005;27(5):643–46. doi: 10.1080/08860220500200890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stefanidis I, Liakopoulos V, Kapsoritakis A, et al. Gastric antral vascular ectasia (watermelon stomach) in patients with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47(6):e77–82. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.02.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.George P, Pawar G, Pawar B, et al. Gastric antral vascular ectasia in a renal transplant patient. Indian J Nephrol. 2007;17:23–25. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin WH, Cheng MF, Cheng HC, et al. Watermelon stomach in a uremia patient. Kidney Int. 2010;78(8):821. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lata S, Gupta V, Nandwani A, et al. Watermelon stomach in end-stage renal disease patient. Indian J Nephrol. 2012;22:477–79. doi: 10.4103/0971-4065.106055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jinga M, Checheriţă IA, Becheanu G, et al. A rare case of watermelon stomach in woman with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2013;54(3 Suppl.):863–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kilincalp S, Üstün Y, Karaahmet F, et al. A new cause of severe anemia in renal transplant recipients: Watermelon stomach. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2015;19(1):150–51. doi: 10.1007/s10157-014-1035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimamura Y, Koga H, Takizawa H. Watermelon stomach: Gastric antral vascular ectasia. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2015;19(4):753–54. doi: 10.1007/s10157-014-1069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rimševičius L, Galkauskas D, Lavinskas J, et al. Gastric antral vascular ectasia should not be overlooked in erythropoietin resistance: A series of case reports. Acta Med Litu. 2018;25(4):219–25. doi: 10.6001/actamedica.v25i4.3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santos S, Bernardes C, Borges V, et al. Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE) and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT): Two different conditions, one treatment. Ann Hematol. 2020;99(2):367–69. doi: 10.1007/s00277-019-03845-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang SH, Kim AY, Do JY. Gastric antral vascular ectasia in a patient with lupus undergoing hemodialysis: A case report. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):468. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-02140-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]