Abstract

Purpose

The objective of this retrospective study was to determine the feasibility of measuring frailty using patient responses to relevant EORTC QLQ-C30 items as proxy criteria for the Fried Frailty Phenotype, in a cohort of patients with Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma (RRMM).

Methods

Data were pooled from nine Phase III randomized clinical trials submitted to the FDA for regulatory review between 2010 and 2021, for the treatment of RRMM. Baseline EORTC QLQ-C30 responses were used to derive a patient-reported frailty phenotype (PRFP), based on the Fried definition of frailty. PRFP was assessed for internal consistency reliability, structural validity, and known groups validity.

Results

This study demonstrated the feasibility of adapting patient responses to relevant EORTC QLQ-C30 items to serve as proxy Fried frailty criteria. Selected items were well correlated with one another and PRFP as a whole demonstrated adequate internal consistency reliability and structural validity. Known groups analysis demonstrated that PRFP could be used to detect distinct comorbidity levels and distinguish between different functional profiles, with frail patients reporting more difficulty in walking about, washing/dressing, and doing usual activities, as compared to their pre-frail and fit counterparts. Among the 4928 patients included in this study, PRFP classified 2729 (55.4%) patients as fit, 1209 (24.5%) as pre-frail, and 990 (20.1%) as frail.

Conclusion

Constructing a frailty scale from existing PRO items commonly collected in cancer trials may be a patient-centric and practical approach to measuring frailty. Additional psychometric evaluation and research is warranted to further explore the utility of such an approach.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11136-023-03390-5.

Keywords: Patient-reported outcomes, Frailty, Multiple myeloma, Geriatric oncology

Introduction

Frailty is an aging-related syndrome of cumulative physical and physiological decline, resulting in burden of symptoms like weakness and fatigue, greater medical complexity, and lower tolerance to medical and surgical interventions as compared to the general population [1, 2]. This is especially true in cancer, where frailty increases patients’ risk for treatment-related toxicity, treatment discontinuation due to toxicity, disease progression, hospitalization, and death [3–6]. As such, there is growing recognition of the potential benefits to using frailty assessments to help guide anti-cancer treatment decision making [7–10]. Studies suggest that consideration of patients’ frailty level when selecting treatment, adjusting doses, and administering supportive care may help reduce toxicity and improve tolerability [5, 11–14]. Importantly, incorporating an assessment of frailty into clinical decision making may increase access to anti-cancer treatment among “fit” patients who may not have otherwise qualified for treatment due to their age alone [15–17].

Multiple approaches have been proposed to detect frailty and guide treatment decisions in older oncology patients. For instance, numerous studies have shown that use of the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA), as opposed to standard care, can reduce grade 3–5 chemo-related toxicity, functional decline, and mortality in oncology patients [13, 14, 18]. However, with nine domains, numerous sub-instruments, multiple items per instrument, and the need for specialist training and/or multidisciplinary collaboration, CGAs can be time consuming and resource intensive. This complexity and burden have led some to question the practicality of CGAs for routine use in clinical trial and clinical practice settings [3, 4, 19–22].

Another method for frailty screening is the Fried Frailty Phenotype. In their landmark study, Fried et al. defined frailty using a cluster of five variables (unintentional weight loss, self-reported exhaustion, low physical activity/energy expenditure, slow gait speed, and weak grip strength) and determined that frailty, as measured by the Fried Frailty Phenotype, was predictive of falls, worsening mobility, hospitalization, and death [23]. A third well-known approach to measuring frailty is the cumulative deficit model or Frailty Index. This model uses 30 to 40 variables that include medical conditions, lab values, symptoms, health attitudes, and functional impairments to calculate a Frailty Index score for each patient, where higher scores indicate greater risk for adverse outcomes [1].

While both the Fried Frailty Phenotype and the Frailty Index are simpler to use than a full CGA and have been validated in oncology patient populations [24–27], they each have limitations. The Fried Frailty Phenotype requires an in-person objective assessment of grip strength and gait speed by a clinician while the Frailty Index can be difficult to operationalize in clinical trials and clinical practice, given the exhaustive number of variables which need to be consolidated from different data sources (e.g., comorbid conditions and medical history from Electronic Medical Records, symptom report from patients, assessments by clinicians, etc.) [3]. Alternatively, frailty measures that rely solely on patient self-report shift data capturing to the patient and foster patient-centricity [28–31]. A resourceful approach to measuring frailty through patient self-report would be to leverage data from routinely administered patient-reported outcome (PRO) assessments. For instance, the Fried Frailty Phenotype includes criteria like exhaustion and low physical activity which are similar to concepts captured in PRO instruments commonly used in cancer trials such as the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS), and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) item libraries. This presents an opportunity to explore adaptation of pre-existing PRO data to measure frailty in clinical trials and clinical practice.

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life 30-item Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) is commonly deployed in global cancer trials submitted for regulatory decision making [32, 33]. The objective of our retrospective study was to determine the feasibility of measuring frailty using patient responses to relevant EORTC QLQ-C30 items as proxy criteria for the Fried Frailty Phenotype, in a cohort of patients with Multiple Myeloma (MM). MM is a hematologic malignancy of plasma cells, resulting in hypercalcemia, bone disease, anemia, and renal dysfunction [34]. MM serves as an ideal case example because it is a cancer of older adults who represent a highly heterogenous population with varied functional capacities, health status, and ability to tolerate intensive treatment regimens [16]. A number of recent studies have investigated MM-specific frailty measures, including an ongoing trial to determine the impact of frailty-adjusted therapy on clinical outcomes [15, 16, 35–37]. Given the rising interest around frailty in MM and the need for a simple yet resourceful approach to measuring frailty, we conducted this proof-of-concept study to identify relevant EORTC QLQ-C30 items to serve as proxy criteria for the Fried Frailty Phenotype and thus determine patients’ level of frailty.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) internal databases were retrospectively searched to identify Phase III randomized clinical trials that were submitted for regulatory review and approved between 2010 and 2021 for the treatment of MM. Baseline data were pooled for this analysis from nine clinical trials that met inclusion criteria. Trials were included if they incorporated the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire. We also limited this analysis to trials in the relapsed/refractory treatment setting as Relapsed/Refractory Multiple Myeloma (RRMM) patients tend to be older and more medically complex than newly diagnosed patients. Patients were included in this analysis if they had completed the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire in its entirety at baseline (prior to randomization and treatment initiation).

Scale Construction

Co-authors selected candidate EORTC QLQ-C30 items that measure concepts identical or similar to each Fried frailty criterion, in order to derive a five-item patient-reported frailty phenotype (PRFP). For example, EORTC QLQ-C30 item #12, “Have you felt weak?” was identified as a proxy for the “weakness” Fried frailty criterion, which is typically captured by measuring grip strength in the clinic. If a given Fried criterion had more than one potential matching candidate EORTC QLQ-C30 item, polychoric correlation coefficients were computed in order to select the item with the highest correlations to the other frailty criterion’s corresponding EORTC QLQ-C30 items (Table 1). Patient responses to each of the final EORTC QLQ-C30 items selected were dichotomized to determine the presence/absence of their corresponding Fried frailty criteria. Two dichotomization approaches were considered (“Not at all” = absent and “A little”/“Quite a bit”/“Very much” = present vs. “Not at all” “A little” = absent and “Quite a bit”/“Very much” = present). Sensitivity analyses were conducted to select the final dichotomization approach. The latter approach was selected due to its congruence with past literature on the prevalence of frailty in MM and its clinical plausibility [28, 38, 39]. Patients were classified as fit if they met none of the five frailty criteria, pre-frail if they met one or two of the frailty criteria, and frail if they met three or more frailty criteria.

Table 1.

Patient-Reported Frailty Phenotype (PRFP)—Fried frailty criteria, corresponding candidate items considered, and final items selected to constitute the PRFP

| Original fried phenotype of frailty criteria [23] | Score | EORTC QLQ-C30 candidate item(s) for PRFP |

|---|---|---|

| Unintentional weight loss (minimum of 10 pounds or ≥ 5% of body weight within the past year) | 0 or 1 | Have you lacked appetite? (Q13) |

| Exhaustion (self-reported) | 0 or 1 |

Did you need to rest? (Q10) [Alternate candidate item considered: Were you tired? (Q18)] |

| Weakness (typically measured by grip strength) | 0 or 1 | Have you felt weak? (Q12) |

| Slowness (typically measured by observing gait speed) | 0 or 1 | Do you have any trouble taking a short walk outside of the house? (Q3) |

| Low physical activity (typically measured by Kcals expended per week using the short version of the Minnesota Leisure Time Activity Questionnaire) | 0 or 1 |

Were you limited in doing either your work or other daily activities? (Q6) [Alternate candidate items considered: Do you have any trouble doing strenuous activities, like carrying a heavy shopping bag or a suitcase? (Q1) Do you have any trouble taking a long walk? (Q2) Do you need to stay in bed or a chair during the day? (Q4) Do you need help with eating, dressing, washing yourself or using the toilet? (Q5) Were you limited in pursuing your hobbies or other leisure time activities? (Q7)] |

|

Summed Score 0–Fit 1 or 2–Pre-Frail ≥ 3–Frail | ||

*Responses to EORTC QLQ-C30 items were dichotomized as follows—‘not at all’/‘a little’ = 0 and ‘quite a bit’/‘very much’ = 1

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize clinical and demographic characteristics of patients included in this analysis as well as to determine the number and proportion of patients categorized as frail, pre-frail and fit based on the PRFP model.

The PRFP was constructed based on a reflective indicator model with an assumption of unidimensionality since each of its items are a reflection or an effect of the single underlying concept of interest—frailty. Structural validity of this single-factor model was tested using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The model was estimated using a polychoric correlation matrix and the weighted least square means and variances (WLSMV) fitting function. Model fit was evaluated using the following fit indices: (a) chi-square, (b) root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), (c) comparative fit index (CFI), (d) standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and (e) Tucker Lewis Index (TLI). A non-significant chi-square statistic indicated acceptable model fit as well as RMSEA ≤ 0.10, CFI > 0.95, SRMR ≤ 0.08, and TLI > 0.95 [40, 41]. In addition, R2 values (squared multiple correlations) were computed as part of the CFA, in order to determine the proportion of variance in each item explained by the latent construct of frailty. R2 > 0.5 indicated a strong association between each item and frailty.

Internal consistency reliability—i.e., the degree to which selected items were inter-related and measured different aspects of the same underlying construct (frailty)—was assessed using Cronbach’s α, with reliability categorized as acceptable (0.70–0.79), good (0.80–0.89), or very reliable (≥ 0.90) [42, 43]. Ninety five percent confidence intervals were calculated for Cronbach’s α.

Known groups validity was assessed to determine whether the PRFP could be used to discriminate between distinct groups which were known to differ on variables of interest like age, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), mobility, self-care, and engagement in usual activity as measured by the EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D). [44]. Five hypotheses were identified a priori to determine known groups validity:

Frail patients were likely to be older than Pre-Frail and Fit patients.

Frail patients were more likely to have a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score ≥ 2 as compared to Pre-Frail and Fit patients.

Frail patients were more likely to report problems with mobility on the EQ-5D mobility subscale as compared to Pre-Frail and Fit patients.

Frail patients were more likely to report problems with self-care on the EQ-5D self-care subscale as compared to Pre-Frail and Fit patients.

Frail patients were more likely to report problems with their usual activities on the EQ-5D usual activities subscale as compared to Pre-Frail and Fit patients.

Known groups analyses for the variables of age and CCI included the entire study sample. However, only six of nine trials incorporated the EQ-5D 3-Level or 5-Level. Thus, known groups analyses for mobility, self-care, and engagement in usual activities as measured by the EQ-5D were limited to the subgroup of patients from the six trials which included the EQ-5D in their study protocol. Group differences were determined using the chi-square test of independence. All analyses were done using R Studio (version 3.6.1) statistical software and two-sided significance levels were set at 0.05.

Results

Out of 5,272 patients randomized across nine trials, 4,928 patients (93%) completed the EORTC QLQ-C30 at baseline and met inclusion/ exclusion criteria. The median (min–max) age of patients in this study was 65 (30–91) years (Table 2). The majority of patients were white (82.4%), male (55.4%), and located outside the United States (93%). Over three quarters of patients in this analysis had a baseline Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS) score of 0 or 1, and their median (interquartile range) EORTC QLQ-C30 Physical Functioning Subscale summary score was 73 (53–87) out of 100. Approximately half of these patients had RRMM at International Staging System (ISS) disease stage I and had two or three prior lines of treatment at baseline. The majority (60%) of patients had no comorbid conditions at study entry, as indicated by their CCI score of 0.

Table 2.

Distribution of sociodemographic and baseline clinical characteristics of patients (n = 4928)

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic | |

| Age, years: Median [range] | 65 [30–91] |

| < 65 | 2304 (46.8) |

| 65 – 74 | 1896 (38.5) |

| 75 – 80 | 569 (11.5) |

| > 80 | 159 (3.2) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 2732 (55.4) |

| Female | 2196 (44.6) |

| Race | |

| White | 4062 (82.4) |

| Asian | 428 (8.7) |

| Black | 114 (2.3) |

| Other | 70 (1.4) |

| Unknown/ Not reported | 254 (5.2) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/ Latino | 165 (3.3) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 3904 (79.2) |

| Not reported | 859 (17.4) |

| Geographic Region | |

| United States of America | 345 (7) |

| Non-United States of America | 4583 (93) |

| Clinical | |

| ISS Stage | |

| Stage I | 2256 (45.8) |

| Stage II | 1582 (32.1) |

| Stage III | 1034 (21) |

| Missing/unknown | 56 (1.1) |

| Number of prior lines of treatment | |

| 1 | 1919 (38.9) |

| 2 or 3 | 2578 (52.3) |

| ≥ 4 | 428 (8.7) |

| Missing/unknown | 3 (0.1) |

| ECOG Performance Status | |

| 0–Fully active, able to carry on all pre-disease performance without restriction | 1954 (39.8) |

| 1–Restricted in physical strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out work of a light or sedentary nature | 2383 (48.5) |

| 2–Ambulatory and capable of all selfcare but unable to carry out any work activities; up and about more than 50% of waking hours | 545 (11.1) |

| 3–Capable of only limited selfcare; confined to bed or chair more than 50% of waking hours | 31 (0.6) |

| 4–Completely disabled; cannot carry on selfcare; totally confined to bed or chair | 0 |

| Not reported | 15 (0.3) |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 Physical Functioning Subscale summary score: Median [interquartile range] | 73 [53–87] |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |

| 0 | 2951 (59.9) |

| 1 | 1190 (24.1) |

| 2 | 527 (10.7) |

| 3 | 161 (3.3) |

| 4 | 65 (1.3) |

| 5 + | 34 (0.7) |

ISS International Staging System, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, EORTC QLQ-C30 European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life 30-item Questionnaire

We were able to identify potential matching candidate EORTC QLQ-C30 items for each of the Fried criteria. Some criterion had multiple candidate items. For instance, exhaustion corresponded with both item #10 “Did you need to rest?” item #18 “Were you tired?” (Table 1). When multiple candidate items existed for a given Fried criterion, polychoric correlations were used to select a final EORTC QLQ-C30 item. Polychoric correlations for the final selected items ranged from 0.48 (between Items #3 and #13, i.e., trouble taking a short walk and lacking appetite) to 0.74 (between items #6 and #10, i.e., limitations in doing work/daily activities and needing rest) (Appendix A). In the case of the Fried criterion “low physical activity,” one of the alternate candidate items considered (Item #2—Do you have any trouble taking a long walk?) had higher correlations to the other proxy items. However, the second most highly correlated item (Item #6—Were you limited in doing either your work or other daily activities?) was ultimately selected as the final proxy in order to be relevant to respondents with disabilities as well as capture a varied aspect of physical functioning, since Item #3 (ability to take a short walk) already captured the ability to walk. Applying the final items which constituted the PRFP to our study cohort, we found 2,729 fit (55.4%), 1,209 pre-frail (24.5%), and 990 frail (20.1%) RRMM patients.

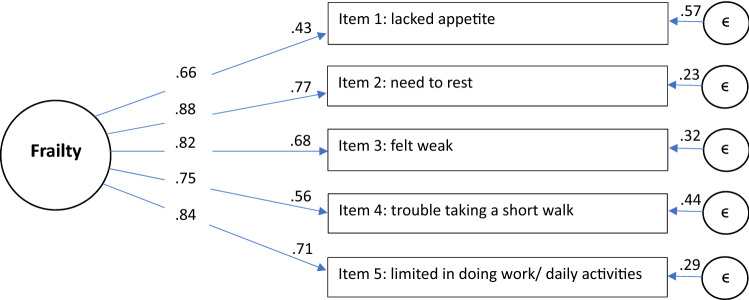

Model fit indices obtained from the CFA demonstrated reasonable model fit for the proposed frailty model: the scaled (robust) chi-square for PRFP was χ2(df) = 171.83(5) (p ≤ 0.05) and RMSEA was 0.082 [95% CI: 0.072–0.093]. Similarly, the CFI was 0.99, SRMR was 0.03, and TLI was 0.99. Factor loadings for each of the PRFP items exceeded the criterion of at least 0.50 or higher [45], ranging from 0.66 to 0.88. Meanwhile, R2 values ranged from 0.43 to 0.77 (Fig. 1). PRFP also showed good internal consistency reliability [Cronbach’s α 0.85 (95% CI: 0.84–0.85)].

Fig. 1.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results for the Patient-Reported Frailty Phenotype (PRFP). The values in-between the arrows from Frailty to each item are the standardized regression coefficients or ‘factor loadings’, an indicator of the strength of the relationship between an item and the underlying construct (frailty). R2 values are displayed to the left of each item box, representing the variance of each item explained by frailty. R2 values > 0.5 are generally preferred [46]. Coefficients adjacent to the error circles on the right represent variance in each item explained by factors other than frailty. It is generally desirable to have more of the variance in each item explained by the construct of interest (in this case frailty) rather than by error/ factors other than frailty

Through known groups analysis, we found that PRFP could be used to distinguish between distinct patient populations in terms of their comorbidities and mobility, self-care, and engagement in usual activities, as measured by the EQ-5D. For instance, frail patients were far more likely to also report problems with mobility (88% of frail vs. 69% of pre-frail vs. 31% of fit patients, p < 0.05), self-care (54% of frail vs. 28% of pre-frail vs. 7% of fit patients, p < 0.05), and engaging in their usual activities (93% of frail vs. 76% of pre-frail vs. 33% of fit patients, p < 0.05), as compared to their Pre-Frail and Fit counterparts on the EQ-5D at baseline (Table 3). On the other hand, known groups analysis for the age variable only showed a weak association between frailty and age (3.4% of frail patients were > 80 years old while 3.5% of pre-frail patients were > 80 years old, and 3% of fit patients were > 80 years old, p < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Known Groups Analysis Results for the Patient-Reported Frailty Phenotype (PRFP)

| Frail | Pre-Frail | Fit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | N = 990 | N = 1209 | N = 2729 |

| ≤ 75 |

859 (86.8%) |

1036 (85.7%) |

2439 (89.4%) |

| 76–80 |

97 (9.9%) |

131 (10.8%) |

207 (7.6%) |

| > 80 |

34 (3.4%) |

42 (3.5%) |

83 (3%) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | N = 990 | N = 1209 | N = 2729 |

| CCI ≤ 1 | 807 (81.5%) |

983 (81.3%) |

2351 (86.1%) |

| CCI ≥ 2 |

183 (18.5%) |

226 (18.7%) |

378 (13.9%) |

| EQ-5D—Mobility | N = 599 | N = 677 | N = 1478 |

| No problems in walking about |

74 (12.4%) |

207 (30.6%) |

1016 (68.7%) |

| Any level of problem in walking about |

525 (87.6%) |

470 (69.4%) |

462 (31.3%) |

| EQ-5D—Self care | N = 599 | N = 676 | N = 1478 |

| No problems in washing/dressing |

274 (45.5%) |

489 (72.3%) |

1371 (92.8%) |

| Any level of problem in washing/dressing |

325 (54.3%) |

187 (27.7%) |

107 (7.2%) |

| EQ-5D—Usual activities | N = 598 | N = 676 | N = 1478 |

| No problems in doing usual activities |

42 (7%) |

161 (23.8%) |

989 (66.9%) |

| Any level of problem in doing usual activities |

556 (93%) |

515 (76.2%) |

489 (33.1%) |

One of the six trials which incorporated the EQ-5D used the 3-Level version while the other five used the 5-Level version. Responses to the 3-Level version were dichotomized for the purposes of this Known Groups Analysis as ‘No problem’ vs. ‘Some problem’/‘Unable to…’, while responses to the 5-Level version were dichotomized as ‘No problem’ vs. ‘Slight’/‘Moderate’/‘Severe’/‘Unable to…’

All differences were statistically significant, p < 0.05, EQ-5D: EuroQol-5 Dimension

Discussion

This feasibility study demonstrated that it is possible to leverage patient responses to routinely administered PRO assessments to measure frailty in MM patients. In our study of almost 5,000 RRMM patients from registrational clinical trials, we were able to adapt EORTC QLQ-C30 data to derive a patient-reported frailty measure based on the Fried Frailty Phenotype. We then used PRFP to determine the prevalence of frailty in our study sample. Our findings were in line with a previous prospective cohort study of RRMM patients, albeit one in which the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) frailty index was used [28]. Similar to our analysis, 53% of patients in their study were fit, 23% were pre-frail, and 24% were frail [28].

In evaluating the measurement properties of PRFP, we found that the proposed patient-reported frailty model was plausible; EORTC QLQ-C30 items that were selected as proxy Fried criteria were well correlated with one another and the measure as a whole demonstrated adequate internal consistency reliability and structural validity. The majority of CFA model fit indices evaluated met their recommended thresholds, with the exception of the chi-square test which was statistically significant. However, chi-square is sensitive to sample size and, given a large sample size, even small departures tend to be significant [46]. Thus, despite the statistically significant chi-square test statistic, our large sample CFA of PRFP lent support to its validity for measuring frailty.

Likewise, results from our known groups analysis supported the ability of PRFP to measure frailty. As hypothesized, PRFP could be used to detect distinct comorbidity levels and distinguish between different functional profiles, with frail patients reporting more difficulty in walking about, washing/dressing, and doing usual activities, than pre-frail and fit patients. However, we only found a weak association between frailty (as measured by PRFP) and age. In general, frailty is thought to correlate with age because of the natural accumulation of aging-associated diseases and disabilities [19]. Yet, we observed that the prevalence of frailty in our sample did not increase significantly with older age. This is perhaps because our study population consisted of clinical trial patients who met stringent inclusion/exclusion criteria for trial enrollment. Thus, inclusion of older patients, especially those above the age of 80, was fairly uncommon in these trials. Moreover, older adults who were included were likely fitter, healthier, and more active than average and therefore not representative of the general RRMM older adult patient population. Another explanation for why we did not observe a strong association between age and frailty in our study is that unlike other commonly used frailty measures in MM, our frailty model excluded age as a component [37]. However, we believe this may be a key strength of the PRFP model because not all patients over 80 are frail and not all frail patients are over 80. By excluding age as a component, the PRFP offers an alternative perspective on frailty that is based on functional deficits, rather than chronological age.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to investigate a fully patient-reported frailty model in the context of MM. Although a number of frailty scales have been developed and tested in MM patients in recent years, they all rely, at least in part, on data collated from clinicians, observers, electronic health records, detailed clinical measurements, and/or laboratory tests [15, 37, 47–51]. Patients, given their lived experience with their condition, are well-equipped to self-report frailty symptoms. However, they remain an underutilized source of data when measuring frailty in oncology, with few studies exploring use of patient self-report to assess frailty in cancer [52, 53]. Meanwhile, multiple studies in the general non-cancer older adult population have demonstrated the feasibility, reliability, and validity of patient-reported frailty measures [29, 30, 54–56]. A key benefit to using patient self-report to measure frailty is that it incorporates the patient’s voice and is a more patient-centric approach [28]. In their recent study, Efficace et al. found a strong correlation between RRMM patients’ frailty status, as measured by the IMWG frailty index, and their self-reported physical functioning and symptom burden as captured by the EORTC QLQ-C30 [28]. The authors noted that fit, pre-frail, and frail patient groups had distinct patient-reported Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) profiles and concluded that their work paves the way for a patient-centered frailty index [28]. Our feasibility study further builds on the groundwork laid by Efficace et al.

Adoption of CGAs and other traditional frailty assessments as the standard of clinical care has been slow due to barriers around time and resources [3, 4, 53]. For instance, in addition to clinical measurements like grip strength and gait speed, the original Frief Frailty Phenotype involves calculating kilocalories of energy expended using the Minnesota Leisure Time Activity instrument [23]. This calculation can be cumbersome and time consuming for routine use [56]. On the other hand, the EORTC QLQ-C30 is already deployed in more than 5000 studies worldwide each year and has been translated into and validated in over 100 languages [57]. This widespread use may help to further study patient-reported approaches to characterize frailty with minimal additional time, effort, and resources needed on the part of clinicians and/or clinical trial sites. In addition to its patient-centricity, this stream of patient-generated data may reduce clinical testing and assessment burden, making patient-reported frailty assessments a potential lower cost, practical solution for clinical practice and clinical trial settings [29–31, 56]. However, it must be acknowledged that PRFP and other similar frailty measures cannot replace a full CGA for the purpose of clinical decision making and treatment adjustment. For instance, a two-step approach could be considered in clinical practice where a patient-reported frailty measure would serve as an efficient and cost-effective preliminary screening tool to prospectively identify patients who are vulnerable for adverse outcomes and might benefit from a full CGA [4].

Our study has important implications from a clinical trial conduct perspective. In the absence of mandated dedicated frailty assessments, such as a CGA, frailty scales which leverage pre-existing PRO data may provide an alternative approach to obtaining important information on frailty status in a less burdensome way. While the EORTC QLQ-C30 is just one possible source of patient-reported data, it is advantageous in that it is frequently embedded into trial protocols and baseline PRO completion rates are typically high [58]. Moreover, PRO-based frailty scales are well positioned for incorporation into decentralized clinical trials, which have seen accelerated growth since the COVID-19 pandemic [59]. Advances in electronic capture of PROs facilitates the ability of a tool like PRFP to be seamlessly embedded into decentralized clinical trials because it can be self-administered, regardless of location.

Our study findings should be interpreted within the context of several limitations. Firstly, the example PRFP constructed in this exploratory study was done as proof-of-concept. Construction of a validated PRFP would require further psychometric evaluation prior to widespread adoption. Similarly, candidate EORTC QLQ-C30 items corresponding to each Fried frailty criterion were selected based on discussion among co-authors. However, we recognize that there is a need for future qualitative research with patients and subject matter experts to further verify and externally validate the selected proxy items which constitute PRFP. Another limitation is that the EORTC QLQ-C30 items selected in our analysis as proxy Fried frailty criteria are not assessed sequentially but asked intermittently throughout the EORTC QLQ-C30. There are also differences in recall, with four of the five items using a seven-day recall, and one item from the Physical Functioning subscale with no recall window. The effect of combining select items from across the EORTC QLQ-C30 and combining items with a recall window to those without, into a single composite frailty measure is unknown and warrants further prospective research and validation. Next, concordance between PRFP and other widely accepted frailty measures in MM such as the IMWG frailty index has not yet been evaluated. This is an important area for future research to gain a better understanding of potential classification errors. Finally, exact matches for Fried frailty criteria were not always available in the EORTC QLQ-C30 for use as proxy items. Specifically, we approximated the closest fit for “unintentional weight loss” as the EORTC QLQ-C30 item on appetite loss. This approximation was made in order to derive a fully patient-reported frailty measure that leveraged pre-existing PRO data. Future patient-reported frailty measures may be constructed from a more detailed search through the entire library of items within existing measurement systems such as EORTC and PROMIS. We were unable to explore adaptation of alternate PRO assessments because our study was limited to a data source which only incorporated the EORTC QLQ-C30. It should be noted that the benefit of a PRFP constructed from the EORTC QLQ-C30 is that it may already be deployed in clinical trials and thus additional information may be obtained from an already existing data source.

Conclusion

Interest in frailty-directed treatment optimization has been growing in oncology due to its potential for minimizing toxicity, improving tolerability, and lengthening duration of treatment to potentially improve survival. This is especially true for older adults who constitute a heterogenous patient population and for whom outcomes related to health-related quality of life and preserving functional independence are of particular importance. Given the significance of frailty at the individual and population levels, having a simple yet effective tool that can be easily deployed in diverse settings ranging from clinical practice to decentralized trials could be valuable. Our initial exploration of clinical trial data in MM patients suggests that it is feasible to leverage patients’ responses to selected items of the EORTC QLQ-C30 to measure frailty. Further research is required to assess the association between frailty—as measured by PRFP—and clinical outcomes in MM as well as evaluate PRFP’s performance against other widely used frailty measures such as the IMWG frailty index. Given that the EORTC QLQ-C30 is deployed in clinical trials across cancer contexts, additional opportunities exist to retrospectively analyze this example PRFP for other hematologic malignancies and solid tumors.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by an appointment to the Research Fellowship Program at the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research—Office of New Drugs, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and FDA.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: MNM; Methodology: MNM; Formal analysis and investigation: MNM; Writing - original draft preparation: MNM, Writing - review and editing: BLK-K, VB, BK, JFF, RDS, DDS, T-YC, EGH, PGK; Supervision: PGK

Funding

This work was supported by Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education

Data availability

Data are not available due to legal restrictions which prevent the U.S. Food and Drug Administration from sharing sponsor-submitted data with third parties. Custom code generated using R programming software for statistical analyses in this manuscript can be shared upon request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, Bergman H, Hogan DB, McDowell I, Mitnitski A. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489–495. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xue QL. The frailty syndrome: Definition and natural history. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2011;27(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ethun CG, Bilen MA, Jani AB, Maithel SK, Ogan K, Master VA. Frailty and cancer: Implications for oncology surgery, medical oncology, and radiation oncology. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2017;67(5):362–377. doi: 10.3322/caac.21406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamaker ME, Jonker JM, de Rooij SE, Vos AG, Smorenburg CH, van Munster BC. Frailty screening methods for predicting outcome of a comprehensive geriatric assessment in elderly patients with cancer: A systematic review. The Lancet Oncology. 2012;13(10):e437–e444. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70259-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Handforth C, Clegg A, Young C, Simpkins S, Seymour MT, Selby PJ, Young J. The prevalence and outcomes of frailty in older cancer patients: A systematic review. Annals of Oncology. 2015;26(6):1091–1101. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, Syin D, Bandeen-Roche K, Patel P, Takenaga R, Devgan L, Holzmueller CG, Tian J, Fried LP. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2010;210(6):901–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boakye D, Rillmann B, Walter V, Jansen L, Hoffmeister M, Brenner H. Impact of comorbidity and frailty on prognosis in colorectal cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2018;64:30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clough-Gorr KM, Thwin SS, Stuck AE, Silliman RA. Examining five- and ten-year survival in older women with breast cancer using cancer-specific geriatric assessment. European Journal of Cancer. 2012;48(6):805–812. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engelhardt M, Ihorst G, Duque-Afonso J, Wedding U, Spät-Schwalbe E, Goede V, Kolb G, Stauder R, Wäsch R. Structured assessment of frailty in multiple myeloma as a paradigm of individualized treatment algorithms in cancer patients at advanced age. Haematologica. 2020;105(5):1183–1188. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.242958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar A, Langstraat CL, DeJong SR, McGree ME, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Weaver AL, LeBrasseur NK, Cliby WA. Functional not chronologic age: Frailty index predicts outcomes in advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecologic Oncology. 2017;147(1):104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.07.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corre R, Greillier L, Le Caër H, Audigier-Valette C, Baize N, Bérard H, Falchero L, Monnet I, Dansin E, Vergnenègre A, Marcq M, Decroisette C, Auliac J-B, Bota S, Lamy R, Massuti B, Dujon C, Pérol M, Daurès J-P, Descourt R, Léna H, Plassot C, Chouaïd C. Use of a comprehensive geriatric assessment for the management of elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: The phase III randomized ESOGIA-GFPC-GECP 08–02 study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(13):1476–1483. doi: 10.1200/jco.2015.63.5839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall PS, Swinson D, Waters JS, Wadsley J, Falk S, Roy R, Tillett T, Nicoll J, Cummings S, Grumett SA, Kamposioras K, Garcia A, Allmark C, Marshall H, Ruddock S, Katona E, Velikova G, Petty RD, Grabsch HI, Seymour MT. Optimizing chemotherapy for frail and elderly patients (pts) with advanced gastroesophageal cancer (aGOAC): The GO2 phase III trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2019;37(15_suppl):4006–4006. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2019.37.15_suppl.4006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li D, Sun C-L, Kim H, Chung V, Koczywas M, Fakih M, Chao J, Chien L, Charles K, Hughes SFDS, Trent M, Roberts E, Celis ESPD, Jayani R, Katheria V, Moreno J, Kelly C, Sedrak MS, Hurria A, Dale W. Geriatric assessment-driven intervention (GAIN) on chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020;38(15_suppl):12010–12010. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.12010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohile SG, Mohamed MR, Culakova E, Huiwen Xu, Loh KP, Magnuson A, Flannery MA, Ramsdale EE, Dunne RF, Gilmore N, Obrecht S, Patil A, Plumb S, Lowenstein LM, Janelsins MC, Mustian KM, Hopkins JO, Berenberg JL, Gaur R, Dale W. A geriatric assessment (GA) intervention to reduce treatment toxicity in older patients with advanced cancer: A University of Rochester Cancer Center NCI community oncology research program cluster randomized clinical trial (CRCT) Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020;38(15_suppl):12009–12009. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.12009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mian HS, Wildes TM, Fiala MA. Development of a medicare health outcomes survey deficit-accumulation frailty index and its application to older patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2018 doi: 10.1200/cci.18.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zweegman S, Engelhardt M, Larocca A. Elderly patients with multiple myeloma: Towards a frailty approach? Current Opinion in Oncology. 2017;29(5):315–321. doi: 10.1097/cco.0000000000000395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zweegman S, Larocca A. Frailty in multiple myeloma: The need for harmony to prevent doing harm. The Lancet Haematology. 2019;6(3):e117–e118. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(19)30011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohile SG, Mohamed MR, Huiwen Xu, Culakova E, Loh KP, Magnuson A, Flannery MA, Obrecht S, Gilmore N, Ramsdale E, Dunne RF, Wildes T, Plumb S, Patil A, Wells M, Lowenstein L, Janelsins M, Mustian K, Hopkins JO, Berenberg J, Anthony N, Dale W. Evaluation of geriatric assessment and management on the toxic effects of cancer treatment (GAP70+): A cluster-randomised study. Lancet. 2021;398(10314):1894–1904. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)01789-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–762. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)62167-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Donovan A, Leech M. Personalised treatment for older adults with cancer: The role of frailty assessment. Technical Innovations & Patient Support in Radiation Oncology. 2020;16:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tipsro.2020.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shahrokni A, Tin A, Alexander K, Sarraf S, Afonso A, Filippova O, Harris J, Downey RJ, Vickers AJ, Korc-Grodzicki B. Development and evaluation of a new frailty index for older surgical patients with cancer. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(5):e193545–e193545. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Welsh TJ, Gordon AL, Gladman JR. Comprehensive geriatric assessment–a guide for the non-specialist. International Journal of Clinical Practice. 2014;68(3):290–293. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2001;56(3):M146–156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abt NB, Richmon JD, Koch WM, Eisele DW, Agrawal N. Assessment of the predictive value of the modified frailty index for Clavien-Dindo grade IV critical care complications in major head and neck cancer operations. JAMA Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery. 2016;142(7):658–664. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2016.0707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Courtney-Brooks M, Tellawi AR, Scalici J, Duska LR, Jazaeri AA, Modesitt SC, Cantrell LA. Frailty: An outcome predictor for elderly gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecologic Oncology. 2012;126(1):20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCarthy AL, Peel NM, Gillespie KM, Berry R, Walpole E, Yates P, Hubbard RE. Validation of a frailty index in older cancer patients with solid tumours. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):892. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4807-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan KY, Kawamura YJ, Tokomitsu A, Tang T. Assessment for frailty is useful for predicting morbidity in elderly patients undergoing colorectal cancer resection whose comorbidities are already optimized. American Journal of Surgery. 2012;204(2):139–143. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Efficace F, Gaidano G, Petrucci MT, Niscola P, Tognazzi L, Antonioli E, Cottone F, Annibali O, Tafuri A, Califano C, Larocca A, Potenza L, Palazzo G, Fozza C, Pastore D, Rigolin GM, Offidani M, Romano A, Tosi P, Kyriakou C, Cascavilla N, Molica S, Gozzetti A, Derudas D, Vignetti M, Cavo M. The accuracy of the international myeloma working group frailty score in capturing health-related quality of life profile of patients with relapsed refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2021;138(Supplement 1):115–115. doi: 10.1182/blood-2021-145977. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morley JE, Malmstrom TK, Miller DK. A simple frailty questionnaire (FRAIL) predicts outcomes in middle aged African Americans. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging. 2012;16(7):601–608. doi: 10.1007/s12603-012-0084-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papachristou E, Wannamethee SG, Lennon LT, Papacosta O, Whincup PH, Iliffe S, Ramsay SE. Ability of self-reported frailty components to predict incident disability, falls, and all-cause mortality: results from a population-based study of older British men. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2017;18(2):152–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saliba D, Elliott M, Rubenstein LZ, Solomon DH, Young RT, Kamberg CJ, Carol Roth RN, MacLean CH, Shekelle PG, Sloss EM, Wenger NS. The Vulnerable Elders Survey: A tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2001;49(12):1691–1699. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, Haes JCJMd, Kaasa S, Klee M, Osoba D, Razavi D, Rofe PB, Schraub S, Sneeuw K, Sullivan M, Takeda F. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1993;85(5):365–376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fernandes LL, Zhou J, Kanapuru B, Horodniceanu E, Gwise T, Kluetz PG, Bhatnagar V. Review of patient-reported outcomes in multiple myeloma registrational trials: Highlighting areas for improvement. Blood Cancer Journal. 2021;11(8):148. doi: 10.1038/s41408-021-00543-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Padala SA, Barsouk A, Barsouk A, Rawla P, Vakiti A, Kolhe R, Kota V, Ajebo GH. Epidemiology, staging, and management of multiple myeloma. Medical Sciences (Basel) 2021 doi: 10.3390/medsci9010003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murillo A, Cronin AM, Laubach JP, Hshieh TT, Tanasijevic AM, Richardson PG, Driver JA, Abel GA. Performance of the International Myeloma Working Group myeloma frailty score among patients 75 and older. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2019;10(3):486–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2018.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Myeloma XIV: Frailty-adjusted Therapy in Transplant Non-Eligible Patients With Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma (FiTNEss). In Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT03720041

- 37.Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Mateos M-V, Larocca A, Facon T, Kumar SK, Offidani M, McCarthy P, Evangelista A, Lonial S, Zweegman S, Musto P, Terpos E, Belch A, Hajek R, Heinz Ludwig A, Stewart K, Moreau P, Anderson K, Einsele H, Durie BGM, Dimopoulos MA, Landgren O, San JF, Miguel PR, Pieter Sonneveld S, Rajkumar V. Geriatric assessment predicts survival and toxicities in elderly myeloma patients: An International Myeloma Working Group report. Blood. 2015;125(13):2068–2074. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-615187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engelhardt M, Dold SM, Ihorst G, Zober A, Moller M, Reinhardt H, Hieke S, Schumacher M, Wasch R. Geriatric assessment in multiple myeloma patients: Validation of the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) score and comparison with other common comorbidity scores. Haematologica. 2016;101(9):1110–1119. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.148189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murugappan MN, King-Kallimanis BL, Bhatnagar V, Kanapuru B, Chen TY, Horodniceanu EG, Singh H, Kluetz PG. Leveraging patient-reported outcomes to measure frailty in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Quality of Life Research. 2021;30(Suppl 1):S1–S177. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown TA. Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. 2. The Guilford Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weston R, Gore PA., Jr A brief guide to structural equation modeling. The counseling psychologist. 2006;34(5):719–751. doi: 10.1177/0011000006286345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fayers PM, Machin D. Quality of life: The assessment, analysis and interpretation of patient-reported outcomes. John Wiley & Sons; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Revicki D. Internal Consistency Reliability. In: Michalos AC, editor. Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Netherlands: Springer; 2014. pp. 3305–3306. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davidson M. Known-Groups Validity. In: Michalos AC, editor. Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Netherlands: Springer; 2014. pp. 3481–3482. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Comrey AL, Lee HB. A first course in factor analysis. Psychology press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bean, J. (2021, 02–26–2021). Using R for Social Work Research. The Ohio State University. Retrieved 01.05.2022 from https://bookdown.org/bean_jerry/using_r_for_social_work_research/

- 47.Cook G, Royle K-L, Pawlyn C, Hockaday A, Shah V, Kaiser MF, Brown SR, Gregory WM, Anthony Child J, Davies FE, Morgan GJ, Cairns DA, Jackson GH. A clinical prediction model for outcome and therapy delivery in transplant-ineligible patients with myeloma (UK Myeloma Research Alliance Risk Profile): a development and validation study. The Lancet Haematology. 2019;6(3):e154–e166. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(18)30220-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Engelhardt M, Domm A-S, Dold SM, Ihorst G, Reinhardt H, Zober A, Hieke S, Baayen C, Müller SJ, Einsele H, Sonneveld P, Landgren O, Schumacher M, Wäsch R. A concise revised Myeloma Comorbidity Index as a valid prognostic instrument in a large cohort of 801 multiple myeloma patients. Haematologica. 2017;102(5):910–921. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2016.162693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Facon T, Hulin C, Dimopoulos MA, Belch A, Meuleman N, Mohty M. A frailty scale predicts outcomes of patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who are ineligible for transplant treated with continuous lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone on the first trial. Blood. 2015;126(23):4239. doi: 10.1182/blood.V126.23.4239.4239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paolo Milani S, Rajkumar V, Merlini G, Kumar S, Gertz MA, Palladini G, Lacy MQ, Buadi FK, Hayman SR, Leung N, Dingli D, Lust JA, Lin Yi, Kapoor P, Go RS, Hwa YL, Gonsalves WI, Zeldenrust SR, Kyle RA, Dispenzieri A. N-terminal fragment of the type-B natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) contributes to a simple new frailty score in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. American Journal of Hematology. 2016;91(11):1129–1134. doi: 10.1002/ajh.24532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patel BG, Luo S, Wildes TM, Sanfilippo KM. Frailty in older adults with multiple myeloma: A study of US Veterans. JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics. 2020;4:117–127. doi: 10.1200/cci.19.00094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kellen E, Bulens P, Deckx L, Schouten H, Van Dijk M, Verdonck I, Buntinx F. Identifying an accurate pre-screening tool in geriatric oncology. Critical Reviews in Oncology Hematology. 2010;75(3):243–248. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mohile SG, Bylow K, Dale W, Dignam J, Martin K, Petrylak DP, Stadler WM, Rodin M. A pilot study of the vulnerable elders survey-13 compared with the comprehensive geriatric assessment for identifying disability in older patients with prostate cancer who receive androgen ablation. Cancer. 2007;109(4):802–810. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin FC, Brighton P. Frailty: Different tools for different purposes? Age and Ageing. 2008;37(2):129–131. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nunes DP, Duarte YA, Santos JL, Lebrão ML. Screening for frailty in older adults using a self-reported instrument. Revista de Saude Publica. 2015;49:2. doi: 10.1590/s0034-8910.2015049005516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Li Y, Chan P, Ma L. Reliability and validity of the self-reported frailty screening questionnaire in older adults. Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. 2020;11:2040622320904278. doi: 10.1177/2040622320904278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.EORTC. EORTC Quality of Life. Retrieved January 24th from https://qol.eortc.org/

- 58.Roydhouse JK, King-Kallimanis BL, Howie LJ, Singh H, Kluetz PG. Blinding and patient-reported outcome completion rates in US Food and Drug Administration cancer trial submissions, 2007–2017. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2019;111(5):459–464. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van Norman GA. Decentralized clinical trials: The future of medical product development? JACC Basic to Translational Science. 2021;6(4):384–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2021.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are not available due to legal restrictions which prevent the U.S. Food and Drug Administration from sharing sponsor-submitted data with third parties. Custom code generated using R programming software for statistical analyses in this manuscript can be shared upon request.