Abstract

Several collected data representing the spread of some infectious diseases have demonstrated that the spread does not really exhibit homogeneous spread. Clear examples can include the spread of Spanish flu and Covid-19. Collected data depicting numbers of daily new infections in the case of Covid-19 from countries like Turkey, Spain show three waves with different spread patterns, a clear indication of crossover behaviors. While modelers have suggested many mathematical models to depicting these behaviors, it becomes clear that their mathematical models cannot really capture the crossover behaviors, especially passage from deterministic resetting to stochastics. Very recently Atangana and Seda have suggested a concept of piecewise modeling consisting in defining a differential operator piece-wisely. The idea was first applied in chaos and outstanding patterns were captured. In this paper, we extend this concept to the field of epidemiology with the aim to depict waves with different patterns. Due to the novelty of this concept, a different approach to insure the existence and uniqueness of system solutions are presented. A piecewise numerical approach is presented to derive numerical solutions of such models. An illustrative example is presented and compared with collected data from 3 different countries including Turkey, Spain and Czechia. The obtained results let no doubt for us to conclude that this concept is a new window that will help mankind to better understand nature.

Keywords: Piecewise modeling, Piecewise existence and uniqueness, Piecewise numerical scheme, Covid-19 model, Fractional operators and stochastic approach

Introduction

Although mankind has been using mathematical models to attempt replicating the spread patterns of infection diseases within given settlements, however in several cases, one will notice that their mathematical models do not always capture the waves and the different crossovers exhibiting by these waves [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. Some examples including the Spanish flu that started in 1918 and ended after three waves in 1920. Another-recent one is the spread of Covid-19 [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]. The disagreement between experimental data and the solutions of mathematical equation are perhaps since complexities of collected data are not sometimes considered. Another reason is perhaps the non-updating of existing theory, for example, many years the reproductive number have been used in many research papers with no new modification , indeed, the reproductive number may not be able to tell beforehand if a disease will have waves or not. Another example is the use of rates that have been always suggested to be constant, white a constant rate clearly show the homogeneity of the spread. Whereas in the normal situation rate of infection could be a function of time to indeed include into the mathematical equation the spread complexities or non-homogeneity. Another quite useful function to evaluate the stability of equilibrium point is the Lyapunov function. Such function cannot however inform about the wave and their patterns. Recorded data of Covid-19 spread of some countries show multiple waves. For example, collected data from Turkey, Czechia and Spain show three waves at least, where each wave presents a different process. Neither the concept of reproductive number or the Lyapunov function or the existing way of modelling epidemiological problems could possibly predict these waves. Indeed, modelling real world problems with crossover effects has always been a great challenge to modelers. Even though significant efforts have been made by researchers from different background, nevertheless there are still many real world problems exhibiting crossover behaviours with complex patterns. An effort made to address this resulted to an introduction of a fractional differential operators with non-singular kernel exhibiting a crossover from stretched exponential to power-law in terms of mean-square displacement. This non-singular kernel also has crossover from normal to sub-diffusion, also, the kernel can express crossover from random walk to power-law. However, crossover from deterministic setting to stochastic or from stochastic to deterministic cannot be captured by this kernel, thus a great limitation of such operators to be used in these scenarios [13], [14], [15], [16].

Very recently, Atangana and Seda suggested the concepts of piecewise differential and integral operators. Additionally, the extended their innovative idea to modelling by suggesting a piecewise modelling. This idea is perhaps the future of modelling with this innovative idea, we suggest in this paper a new way to model epidemiological problems exhibiting crossover behaviours. In this paper, two illustrative examples will be presented. We will assume that real world spread exhibit three waves with different patterns, classical, nonlocal and randomness, a permutation can be done to have different behaviours based on the above processes.

Modeling spread of infectious diseases with waves

In this section, we present a new way to model spread of infectious diseases exhibiting waves with different patterns. Let assume without loss of generality that a mathematical model with n classes describes spread of an infectious diseases with three waves where each wave exhibits different patterns, assume with no loss of generality that classical mechanical processes, non-local processes, randomnessly and their permutation, which will be considered in different cases. It is worth noting that in a real world problem where different waves or patterns are observed collected data will guide the choice piecewise differential operators. In this section, however, we suggest theoretically for illustration the order of patterns. This will be presented in several cases.

Case 1: Classical-power-law-randomness

In this case, we assume a scenario where the three waves of the spread exhibit the above processes. We assume that the first process starts from to , the second from to , and the last from to . A piecewise mathematical model associate to this can be given as

| (1) |

where are densities of randomness and are the functions of noise.

Case 2: Classical-Mittag-Leffler law-randomness

In this case, we assume a scenario where the three waves present processes with classical behaviors, passage from stretched exponential to power-law and randomness, within the intervals described earlier in Case (1). A piecewise model associate to the above scenarios can be given as

| (2) |

Case 3: Classical-fading memory-randomness

In this case, it is assumed that three waves are observed where the second wave displays fading memory process, which was known to be described best with the differential operator with exponential kernel. We also assume that three waves appear in the intervals described in Case (1), then, the mathematical model associate to this scenario is given as:

| (3) |

It is noted that in Case (1), (2) and (3)

| (4) |

| (5) |

where is the normalization function such that . Also

| (6) |

where is the normalization function such that .

The analysis regarding the theory of existence and uniqueness will not be discussed here in general. However, this can be achieved within each interval In our paper, we will present existence and uniqueness for some examples. But here, we shall present numerical solution of such model.

Numerical solution of piecewise epidemiological model

Assuming that the described models satisfy theoretical aspects of existence and uniqueness. Thus in this section, we present numerical solutions. We shall use in all cases based on the Newton polynomial interpolation [23].

Numerical method for Case 1

We consider the first Case

| (7) |

We divide in three

| (8) |

The numerical solution can then be provided as

| (9) |

Numerical method for Case 2

We deal with the following problem with second Case

| (10) |

The numerical solution for such problem is given by

| (11) |

Numerical method for Case 3

We consider the following problem with third Case

| (12) |

Using same routine, the numerical solution can be obtained as

| (13) |

A mathematical model of Covid-19 spread with piecewise modeling

In this section, we consider a mathematical model of Covid-19 spread introduced in [11] and modify it by piecewise differential operators. Such model can be considered as (see Table 1);

where

| (14) |

The function is the number of individuals susceptible to infection at a given time . The function is the number of individuals infected but without symptoms at a given time . The function is the number of individuals infected but not yet isolated at a given time . The function is the number of individuals quarantined at a given time . The function is the number of individuals confirmed to be infected with the virus, isolated and expecting recovery at a given time . The function is the number of individuals recovered at a given time The function is the concentration of the virus in the environmental reservoir. The initial conditions are

| (15) |

Table 1.

Parameters of the suggested Covid-19 model.

| : | Birth rate | |

| : | Natural mortality rate | |

| : | The disease-induced fatality rate | |

| : | The incubation period between the infected and the onset of symptoms | |

| : | The rate of recovery from the infectious disease | |

| : | The rate at which highly infectious individuals are confirmed | |

| : | The rate at which susceptible are quarantined | |

| : | The rate at which exposed are quarantined | |

| : | The rate at which quarantine individuals are confirmed | |

| : | The rate at which quarantined move back to the susceptible class | |

| : | The rate at which the exposed contribute the disease to the environmental reservoir | |

| : | The rate at which the infected contribute the disease to the environmental reservoir | |

| : | Rate of removal of the virus from the environmental reservoir | |

| : | Total population | |

| : | Transmission rate from the exposed to the susceptible | |

| : | Transmission rate from the highly infected to the susceptible | |

| : | Transmission rate from the environmental reservoir to the susceptible | |

| : | Coefficient providing adjustment to the transmission rate |

Existence and uniqueness of Covid-19 model

In this section, we attempt to present a proof of existence and uniqueness of system solution of this model. However, we shall note that, different techniques will be applied in respect to each interval, indeed for the first and second Case, the well-known procedure using the Banach fixed-point theorem or modified versions will be applied, however, the last part, since concerning stochastic a different technique is applied.

We now present the existence and uniqueness of the piecewise model. For simplicity, we write subject to

| (16) |

where

| (17) |

To show the existence and uniqueness, we shall prove that and , satisfy

-

1.

Linear growth condition

-

2.

The Lipschitz condition.

, another methodology will be adopted.

For proof, we consider for .

Since all the used parameters of our model a positive constant, thus, they are continuous in Lipschitz sense for a given initial size of population , one can find a unique local solution. , where denotes explosion time. To insure the solution is global, one has to prove that such system solution is global, we should prove that . To achieve our goal, we consider is a positive constant such that lies within . Additionally, we define a stopping time

| (18) |

for each .

is monotonically increasing as . with . , if we show that , then we can conclude that and is solution. To achieve that we have to prove that . Nevertheless if the conclusion is contradictory, then there exists and such that

| (19) |

We additionally define a function in space such that

| (20) |

Owning the fact that , this leads to . Additionally, it is assumed that and , therefore a direct application of Ito formula leads to

| (21) |

Here

| (22) |

Then

| (23) |

and

| (24) |

By direct integration from to , we have

| (25) |

Setting for and thus . Noting that for , there must exist at least one which is equal to or . Then or as result

| (26) |

From above, we can write

| (27) |

Here is the indicator function of . Thus leads

| (28) |

which is a contradiction. Therefore under the conditions presented earlier which completes the proof. Within we show that

| (29) |

and

| (30) |

For , we have

| (31) |

where and under the condition . For , we get

| (32) |

if .

| (33) |

if .

| (34) |

under the condition .

| (35) |

if .

| (36) |

if . Finally, we have

| (37) |

under the condition . To verify second condition, we write

| (38) |

| (39) |

| (40) |

| (41) |

| (42) |

| (43) |

| (44) |

Therefore under the condition that

| (45) |

Then assumed that the solution are positive in , then the piecewise has a unique positive solution.

Applications for Covid-19 model

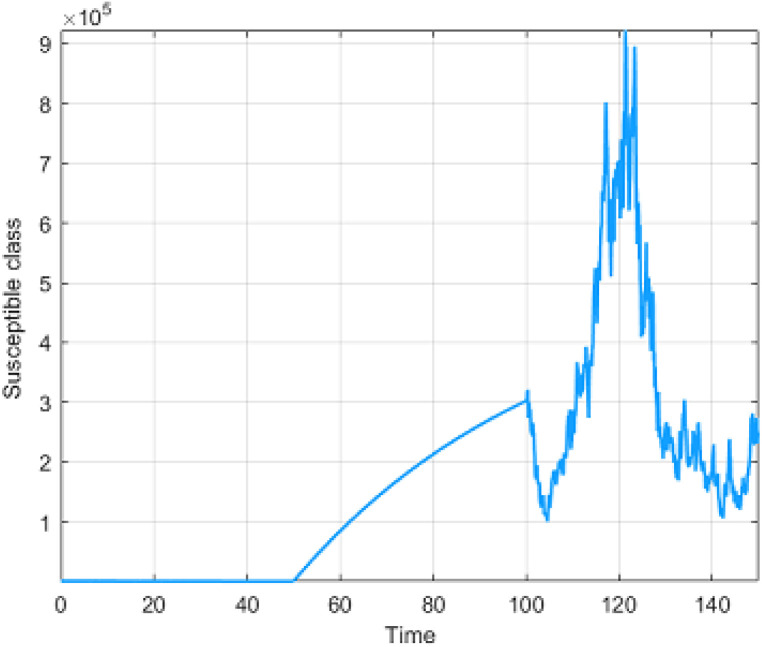

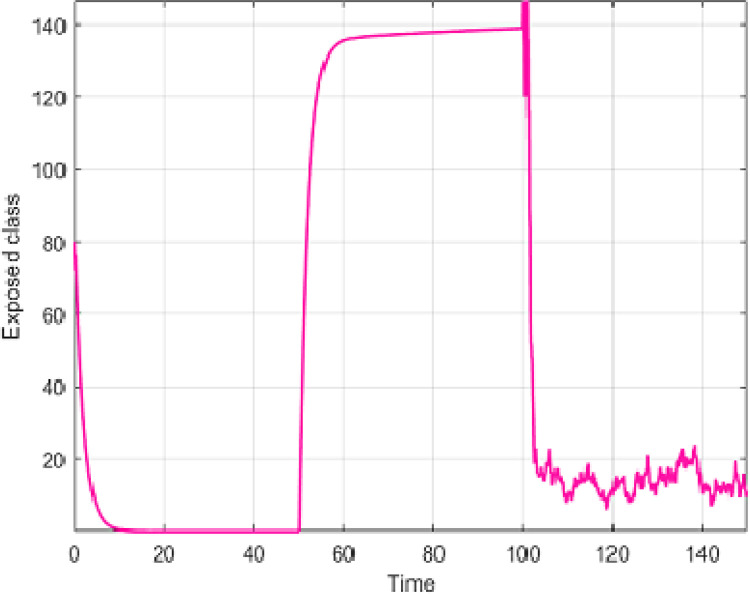

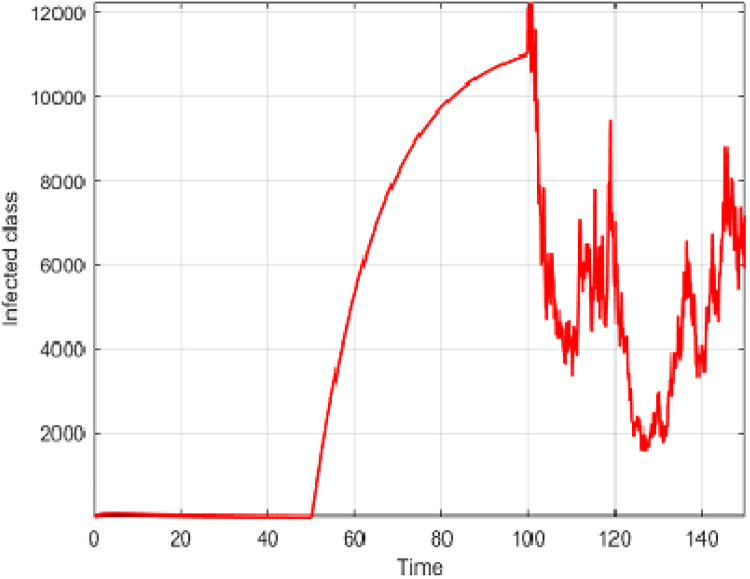

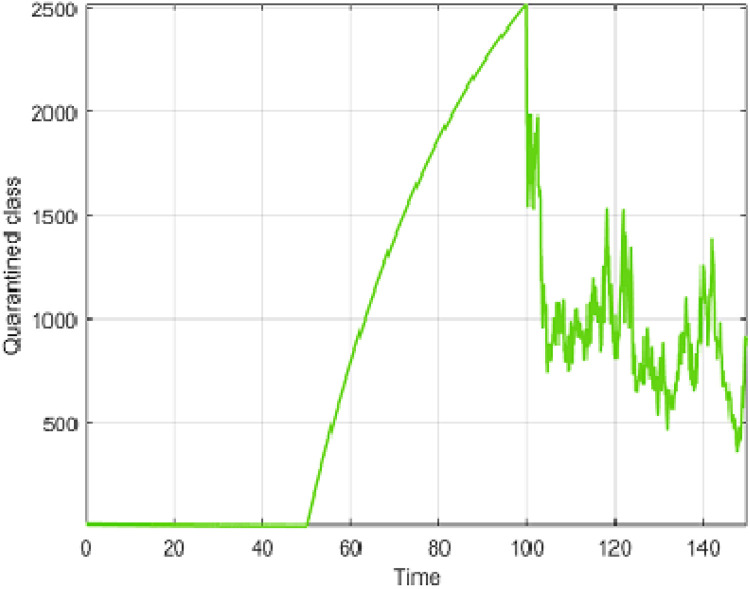

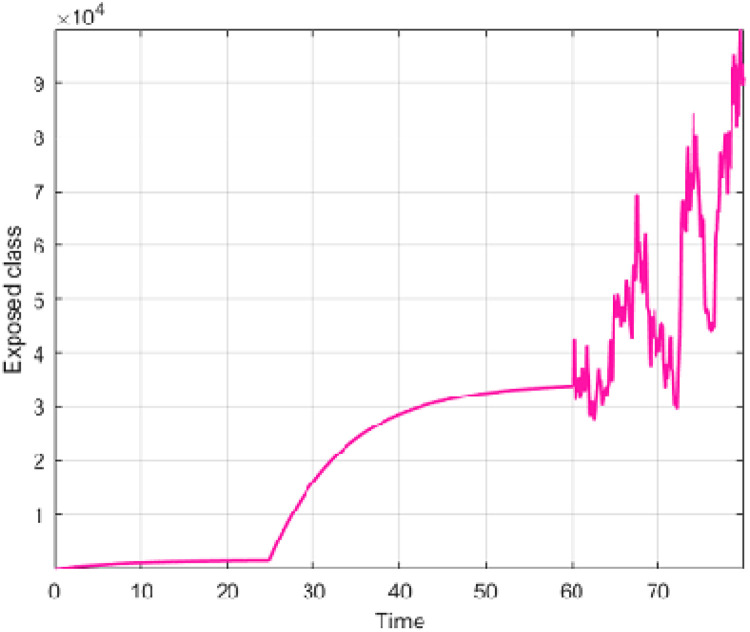

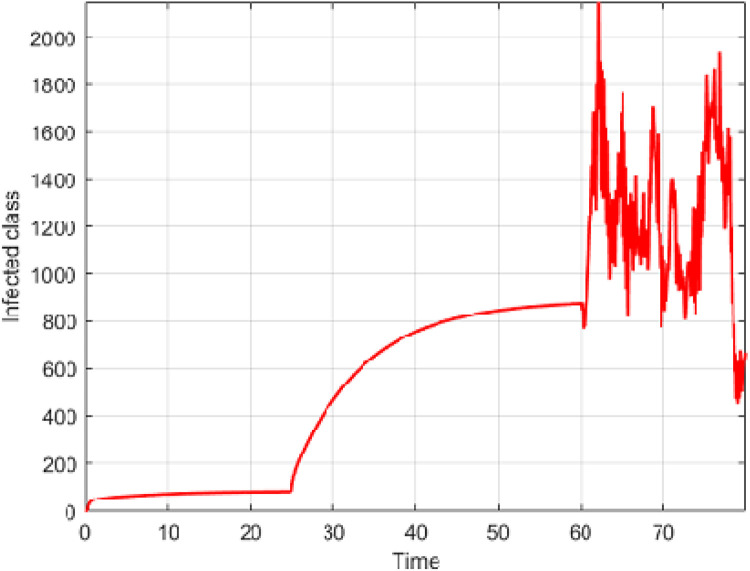

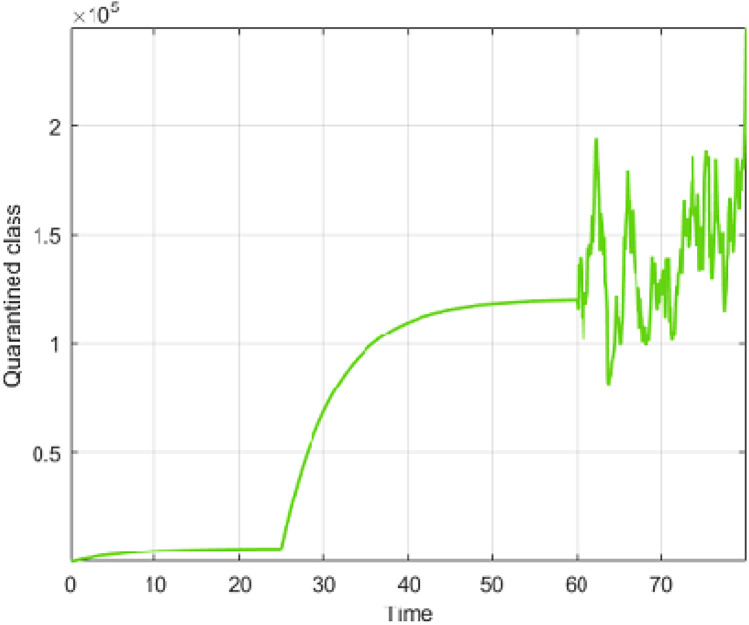

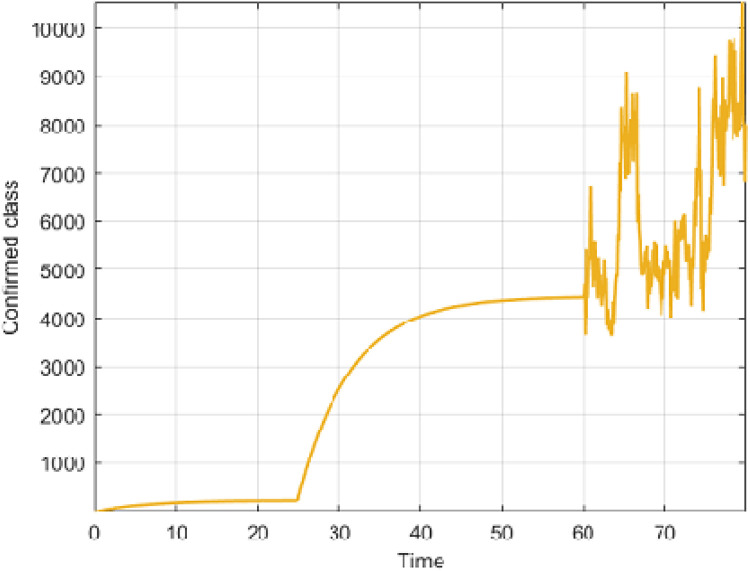

A demonstrative example is better than precept, therefore, in this section, we present an application of the suggested theory. In particular, we will consider a mathematical model that was suggested to depicting the spread of Covid-19 within a given settlement. The model will be later modified to follow the steps presented in piece-wise modeling and for each model, a numerical method will be used to provide a numerical solution to the model. Numerical simulation using the suggested numerical are performed and depicted in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7 for the first Case, Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10, Fig. 11, Fig. 12, Fig. 13, Fig. 14, Fig. 15, Fig. 16, Fig. 17, Fig. 18, Fig. 19, Fig. 20, Fig. 21 for second Case and lastly Fig. 22, Fig. 23, Fig. 24, Fig. 25, Fig. 26, Fig. 27, Fig. 28 for third Case.

Fig. 1.

Numerical visualization for susceptible people for .

Fig. 2.

Numerical visualization for exposed people for .

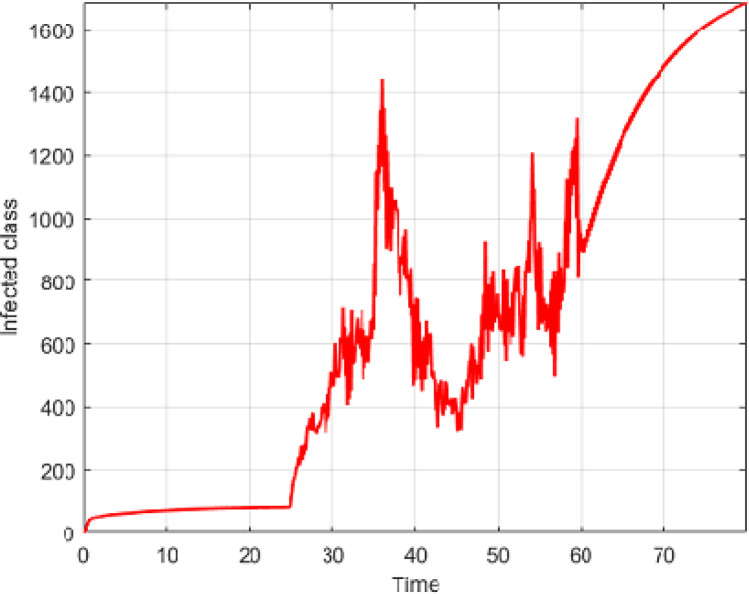

Fig. 3.

Numerical visualization for infected people for .

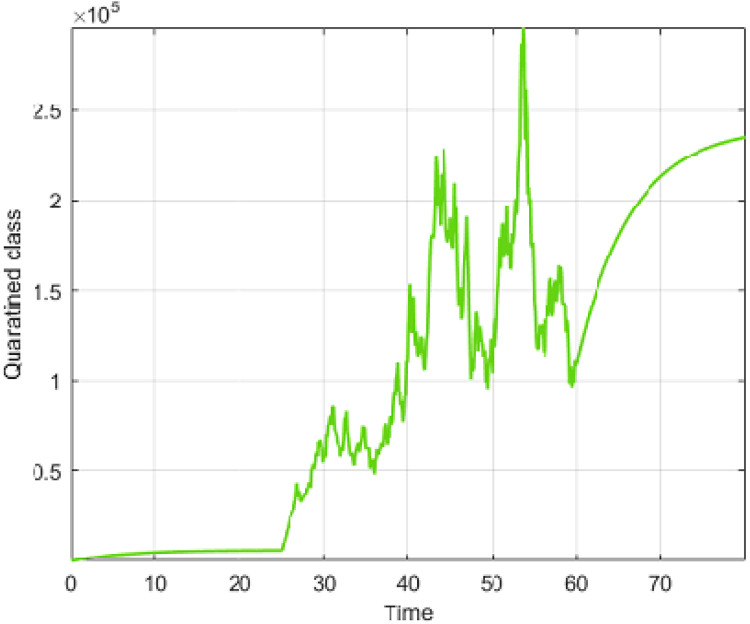

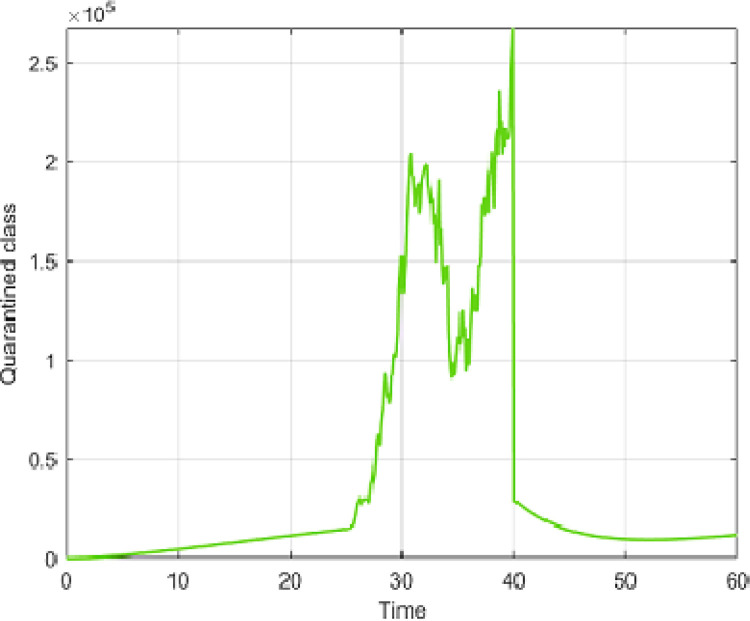

Fig. 4.

Numerical visualization for quarantined people for .

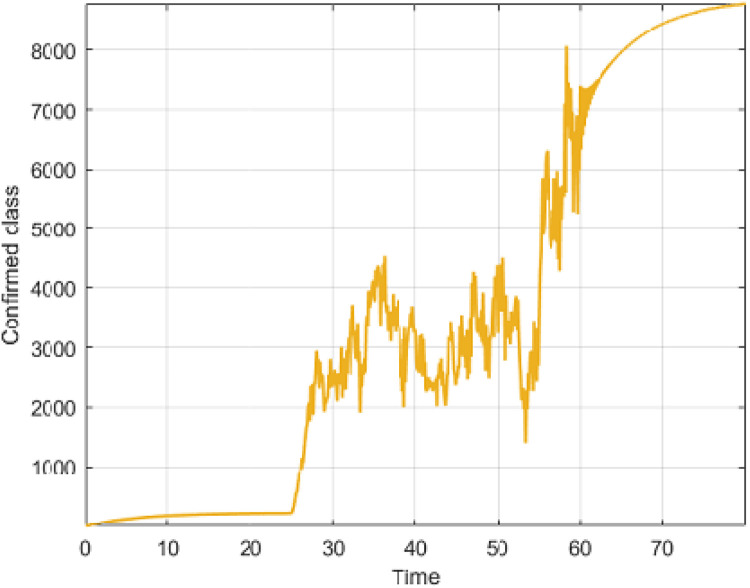

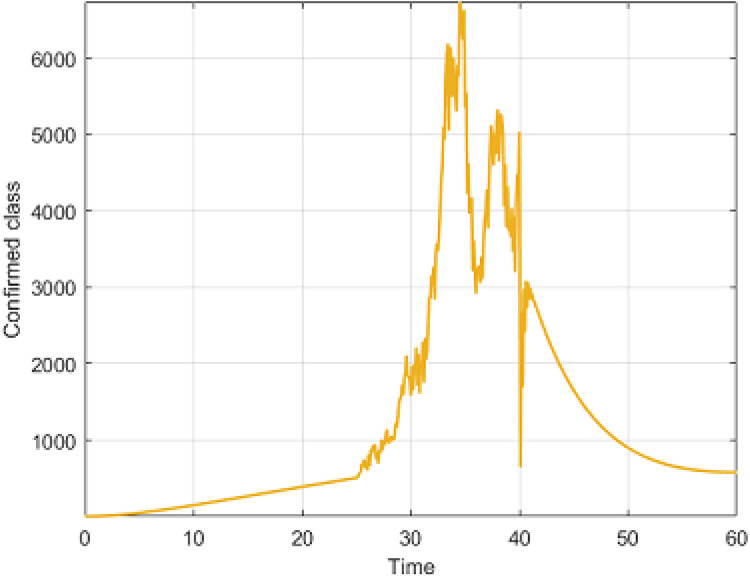

Fig. 5.

Numerical visualization for confirmed people for .

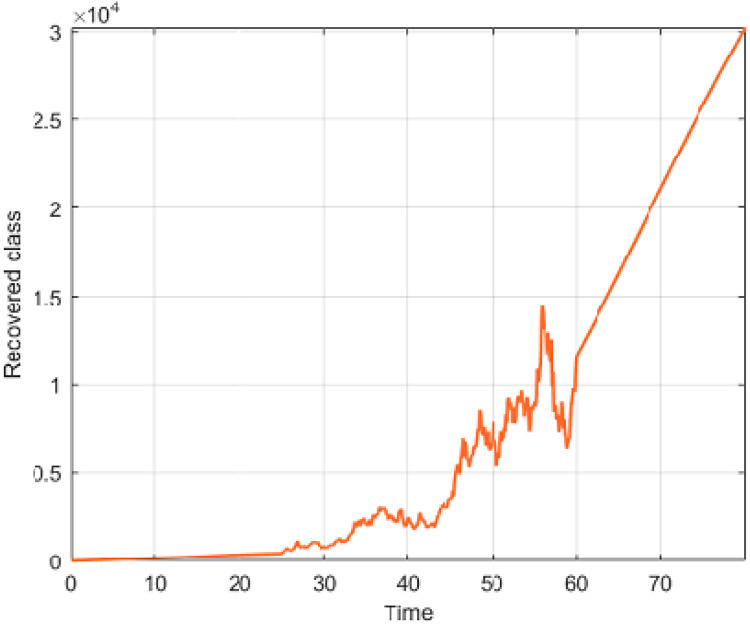

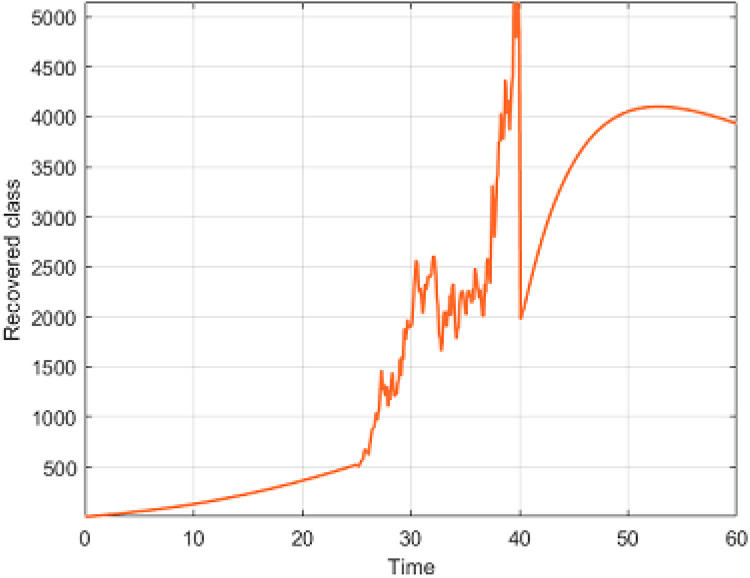

Fig. 6.

Numerical visualization for recovered people for .

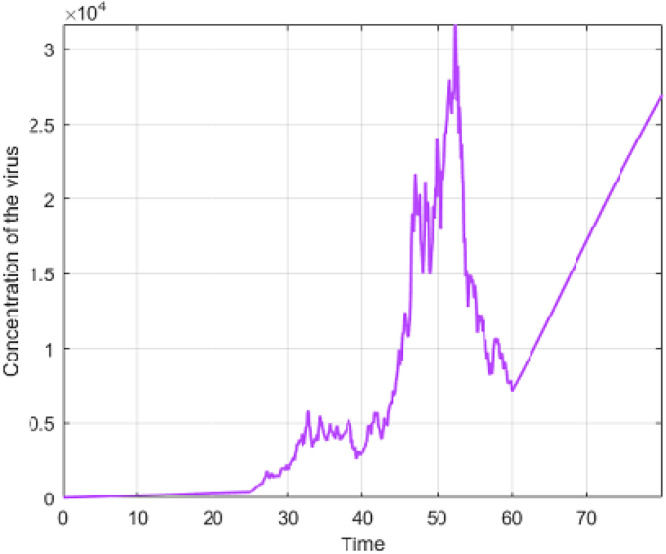

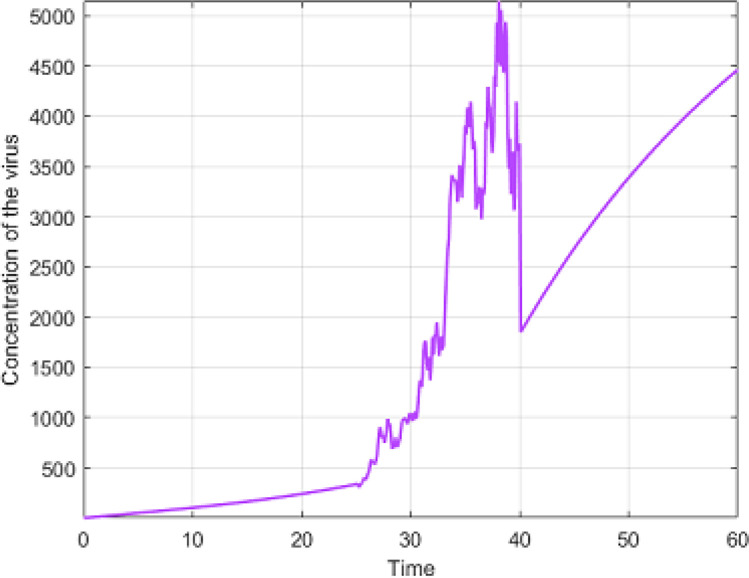

Fig. 7.

Numerical visualization for concentration of the virus for .

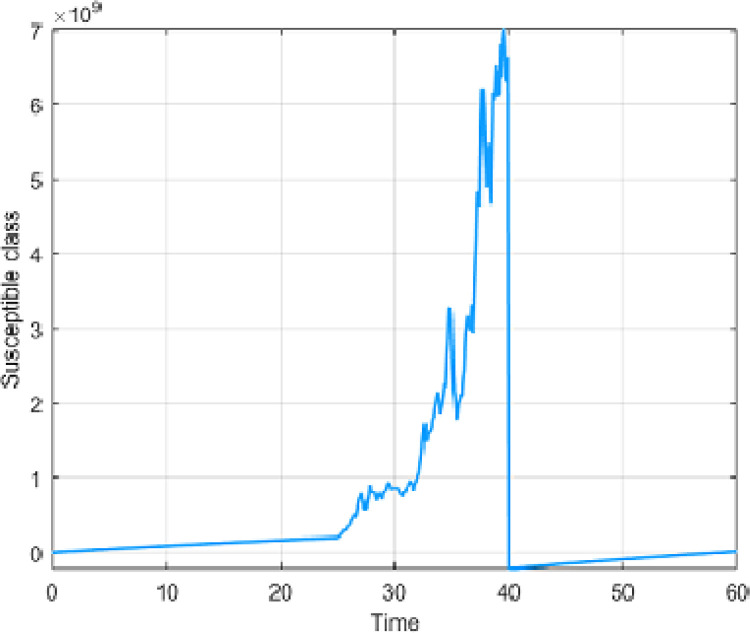

Fig. 8.

Numerical visualization for susceptible people for .

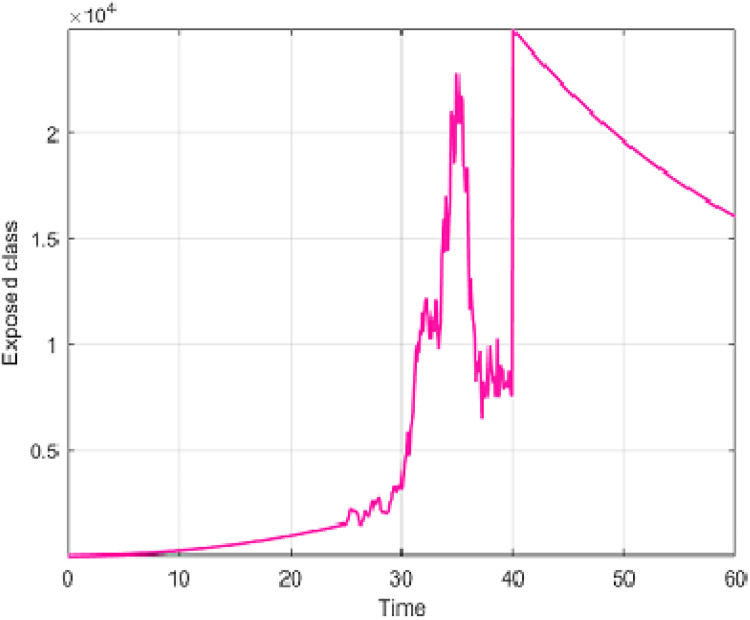

Fig. 9.

Numerical visualization for exposed people for .

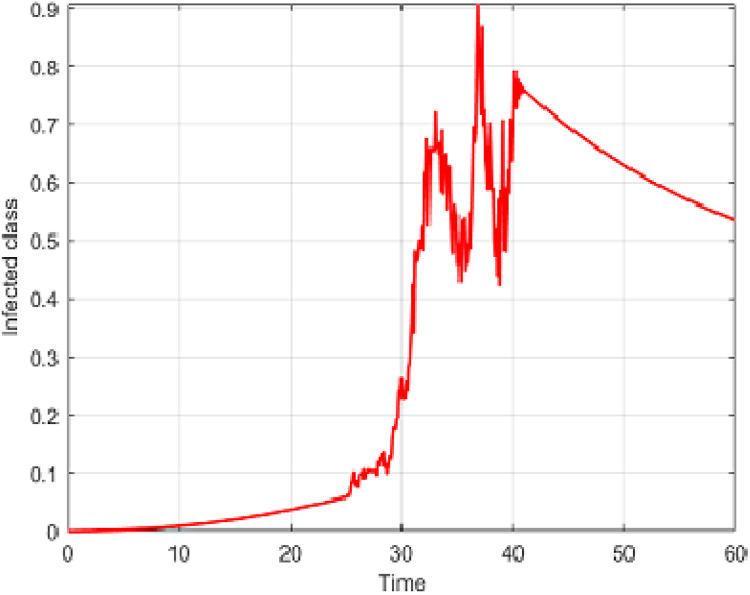

Fig. 10.

Numerical visualization for infected people for .

Fig. 11.

Numerical visualization for quarantined people for .

Fig. 12.

Numerical visualization for confirmed people for .

Fig. 13.

Numerical visualization for recovered people for .

Fig. 14.

Numerical visualization for concentration of the virus for .

Fig. 15.

Numerical visualization for susceptible people for .

Fig. 16.

Numerical visualization for exposed people for .

Fig. 17.

Numerical visualization for infected people for .

Fig. 18.

Numerical visualization for quarantined people for .

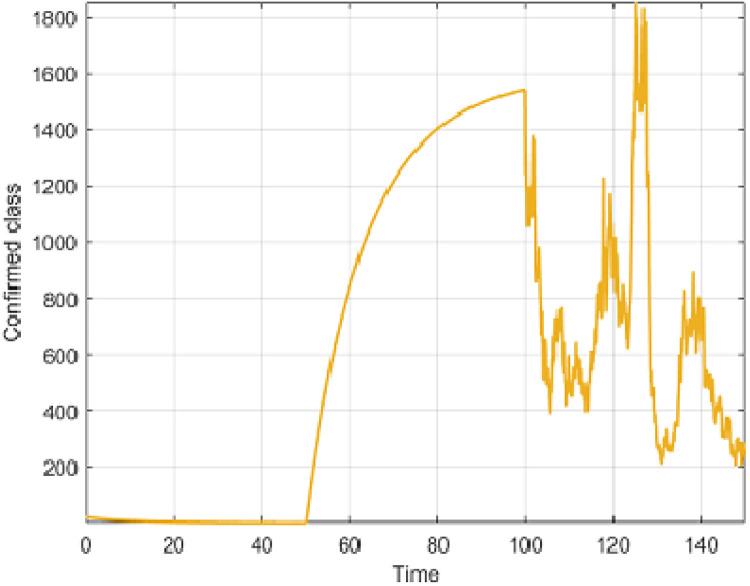

Fig. 19.

Numerical visualization for confirmed people for .

Fig. 20.

Numerical visualization for recovered people for .

Fig. 21.

Numerical visualization for concentration of the virus for .

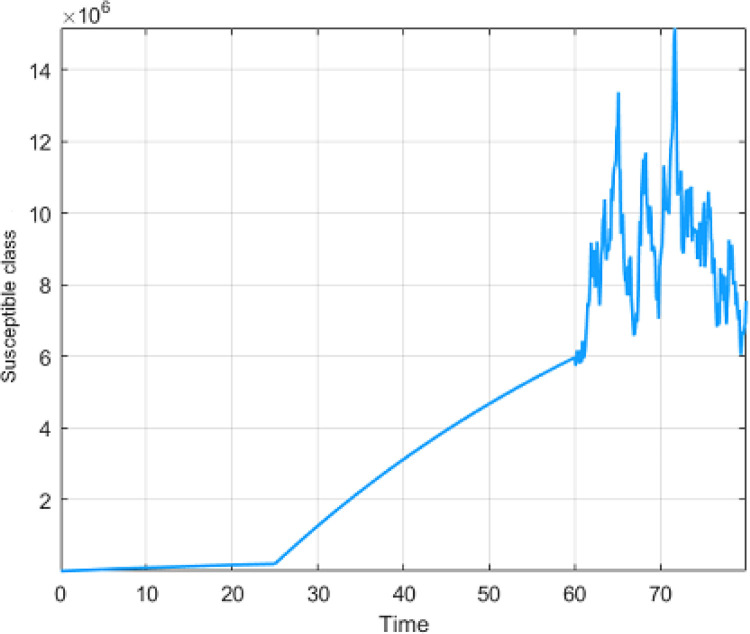

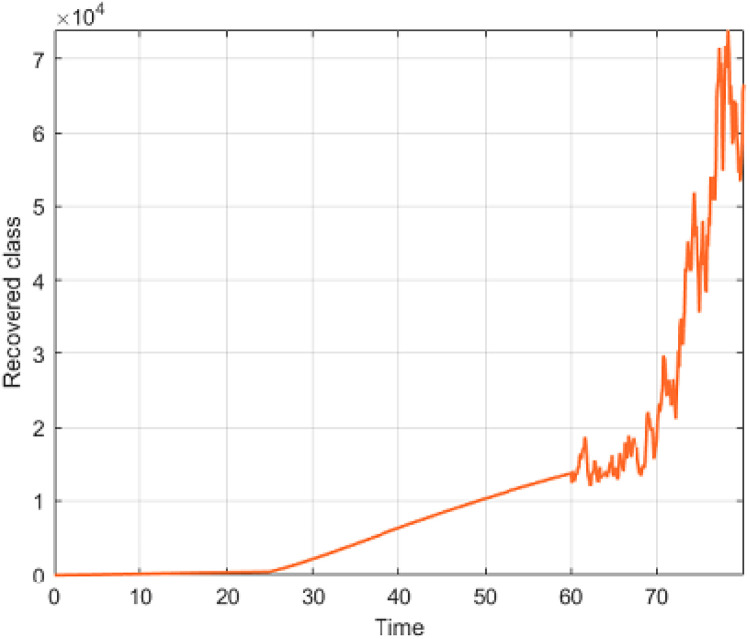

Fig. 22.

Numerical visualization for susceptible people for .

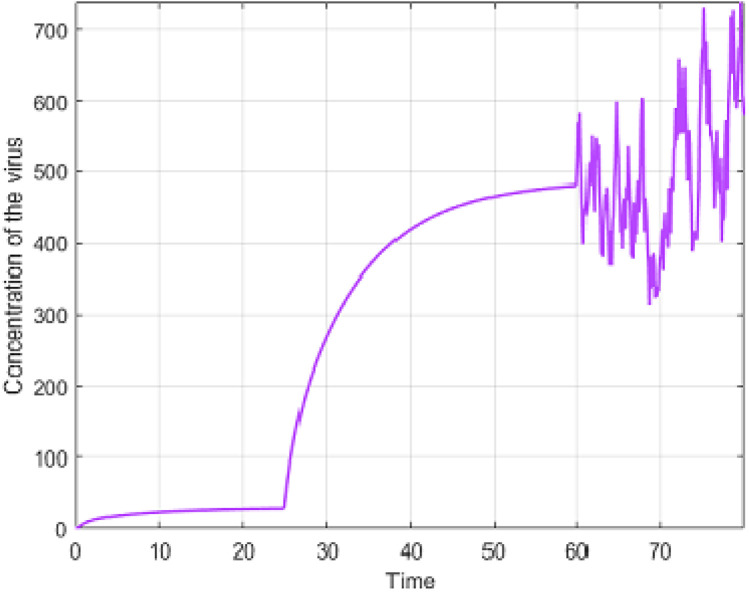

Fig. 23.

Numerical visualization for exposed people for .

Fig. 24.

Numerical visualization for infected people for .

Fig. 25.

Numerical visualization for quarantined people for .

Fig. 26.

Numerical visualization for confirmed people for .

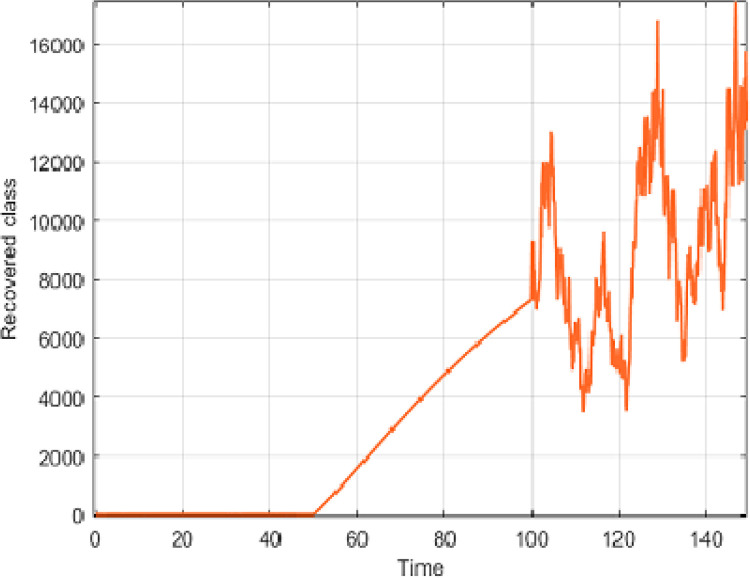

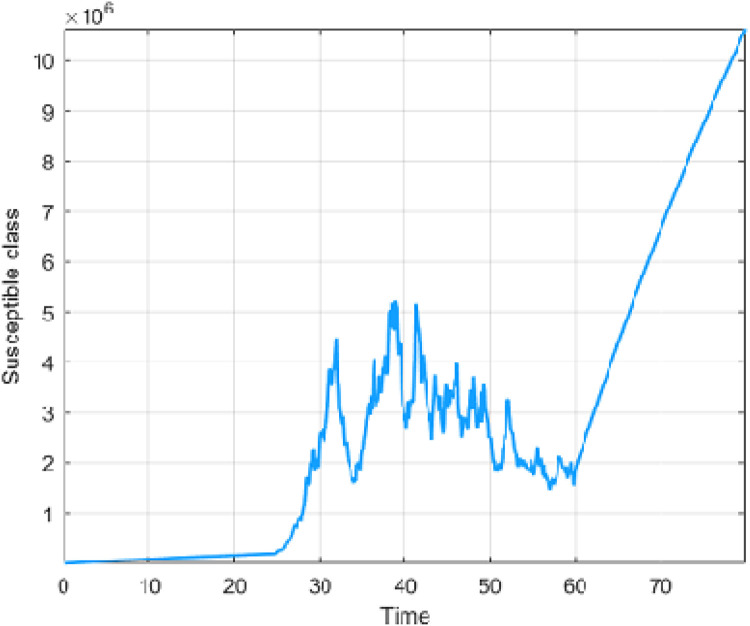

Fig. 27.

Numerical visualization for recovered people for .

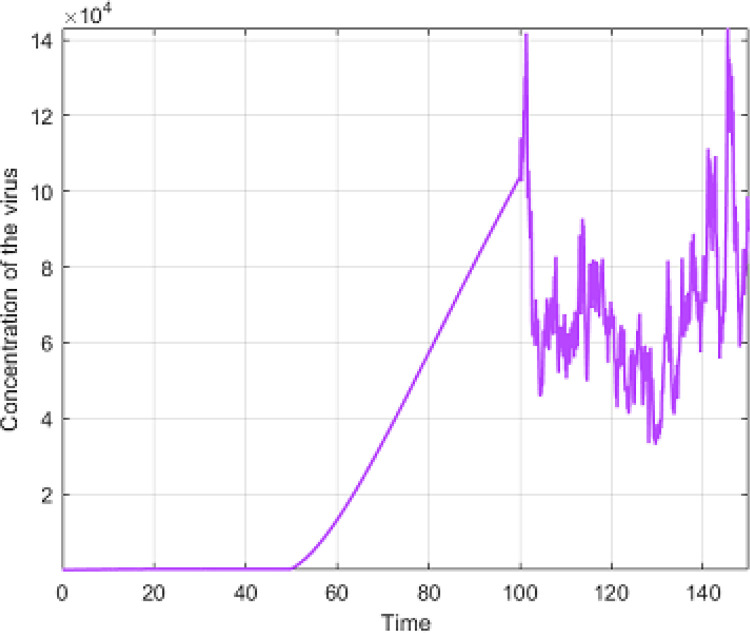

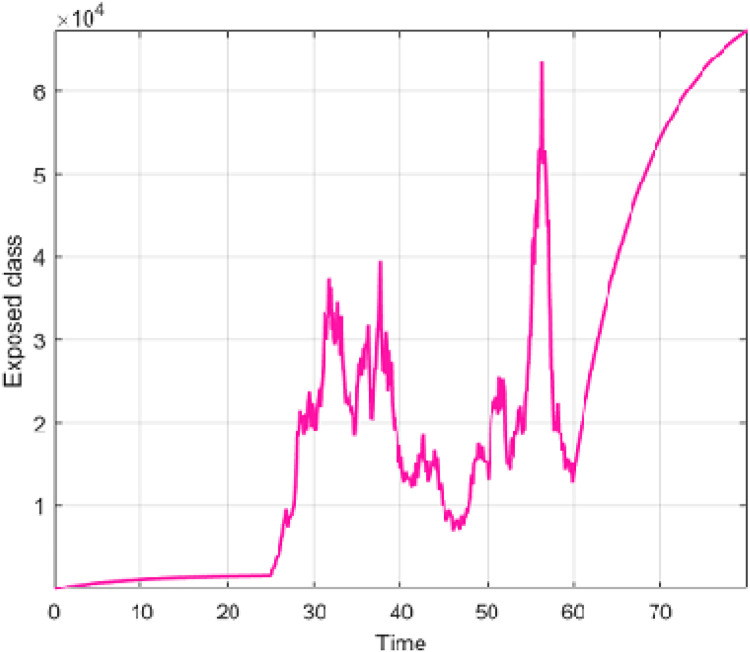

Fig. 28.

Numerical visualization for concentration of the virus for .

Numerical simulation of Covid-19 model for Case 1

In Case 1, we consider a country within which the spread displays three processes, including classical behaviors, power law behavior and finally stochastic behaviors. In this case, if we consider as the last time of the spread, this is to say, the last day where a new infection occur, then, for the first period of time ranging from to , the mathematical model will be constructed with classical differential operator, the second phrase, the model will be with the Caputo-Power law differential operator and finally stochastic approach will be used at the last phase. The mathematical model explaining this dynamic is then presented below.

The initial conditions are considered as

| (46) |

and the parameters are

| (47) |

The numerical simulations for piecewise model are performed in Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7.

Numerical simulation of Covid-19 model for Case 2

In Case 2, we consider a given community where the spread displays three processes, including classical behaviors, fading memory behavior and finally stochastic behaviors. In this case, if we consider as the last time of the spread, this is to say, the last day where a new infection occur, then, for the first period of time ranging from to , the mathematical model will be constructed with classical differential operator, the second phrase, the model will be with the Caputo–Fabrizio differential operator and finally stochastic approach will be used at the last phase. The mathematical model explaining this dynamic is then presented below.

The initial conditions are as follows:

| (48) |

and the parameters are

| (49) |

| (50) |

The numerical simulations of model with piecewise differential and integral operators are performed in Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10, Fig. 11, Fig. 12, Fig. 13, Fig. 14.

In Fig. 15, Fig. 16, Fig. 17, Fig. 18, Fig. 19, Fig. 20, Fig. 21, the numerical simulations of model with piecewise derivative are depicted with

| (51) |

and the parameters

| (52) |

| (53) |

Numerical solution of Covid-19 model for Case 3

In Case 3, assuming a given country within which the spread displays three processes, including classical behaviors, a passage from stretched exponential to power law behavior and finally stochastic behaviors. In this case, if we consider as the last time of the spread, this is to say, the last day where a new infection occur, then, for the first period of time ranging from to , the mathematical model will be constructed with classical differential operator, the second phrase, the model will be with the Atangana–Baleanu fractional differential operator and finally stochastic approach will be used at the last phase. The mathematical model explaining this dynamic is then presented below.

In Fig. 22, Fig. 23, Fig. 24, Fig. 25, Fig. 26, Fig. 27, Fig. 28, the numerical simulations of model with piecewise derivative are depicted with

| (54) |

| (55) |

and the parameters

| (56) |

Comparison between piecewise model and real data for some countries

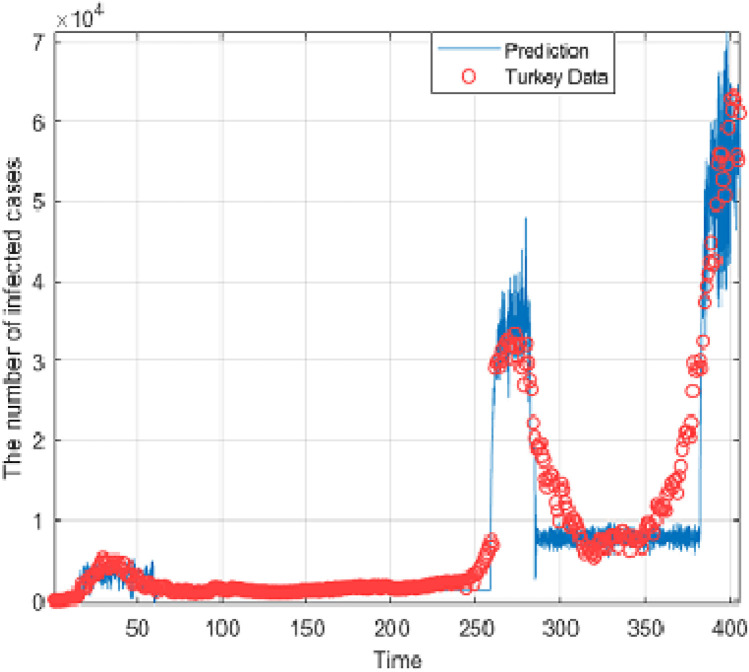

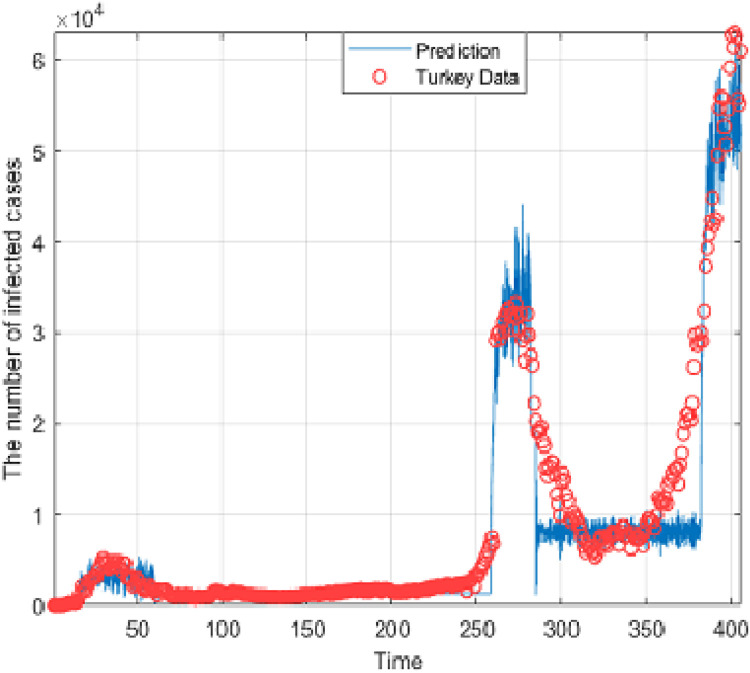

Comparison between a piecewise model and real data in Turkey

In this subsection, we compare modified model by using model that we introduced in the previous chapters with daily number of cases between March 11 and April 20, 2021 in Turkey [24]. Since it will not be easy to predict such long time interval data, to achieve greater compatibility between model that we will suggest and data, we will write our model in more pieces. In other words, although we presented our model in 3 pieces in the previous chapters, of course, we should know that we can write the model in more pieces in order to capture more reality in modeling daily problems. Thus, it will be inevitable for us to achieve our goal. But since this situation brings much more complexity with it, that is why let us first present some notations to avoid this complexity. We will use the notation such that

| (57) |

and

To do comparison, considering above notations, we construct the following model piecewisely

| (58) |

We shall present the parameters and initial conditions that we used for comparison in Turkey. Initial conditions are considered as

| (59) |

and the parameters are

| (60) |

The simulations for comparison are performed using above initial data and parameters in Fig. 29, Fig. 30. We shall note that, the theoretical parameters used here are those that matched with experimental data. The initial conditions are chosen from Turkish population and initial numbers of infected individuals.

Fig. 29.

Comparison between piecewise model and real data in Turkey for .

Fig. 30.

Comparison between piecewise model and real data in Turkey for .

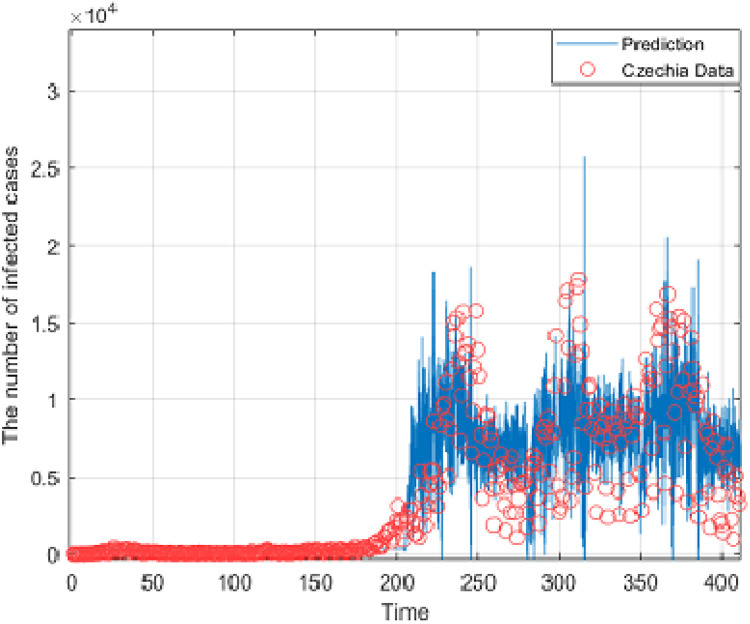

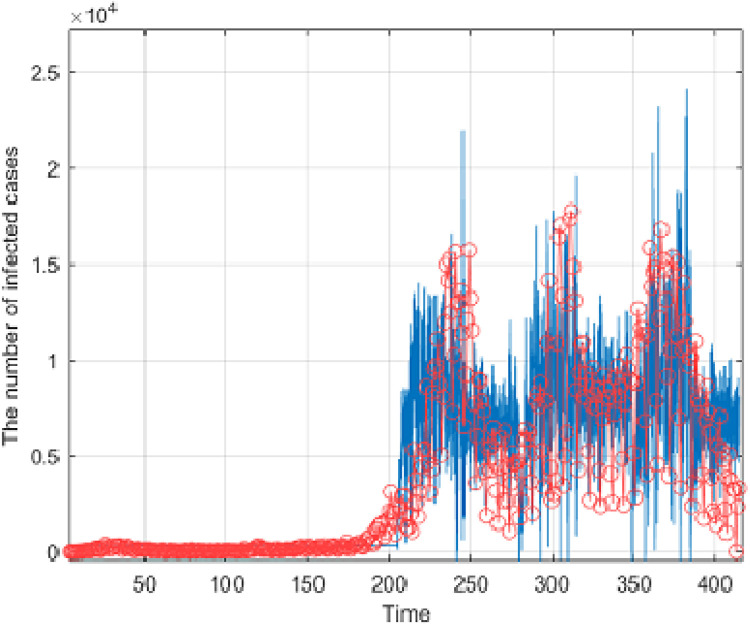

Comparison between piecewise model and real data in Czechia

In this subsection, we compare the daily number of cases between 2 March and 20 April 2021 in Czech Republic with model that will be presented here to analyze the concept we have introduced and to display different processes [24]. Thus, we present the following model which composed of 7 pieces

| (61) |

| (62) |

The parameters and initial conditions that we used for comparison in Czechia are given as

| (63) |

and

| (64) |

The simulations for comparison are presented using above initial data and parameters in Fig. 31, Fig. 32. The theoretical parameters used here are those that matched with experimental data. The initial conditions are chosen from Czechia population and initial numbers of infected individuals.

Fig. 31.

Comparison between piecewise model and real data in Czechia for .

Fig. 32.

Comparison between piecewise model and real data in Czechia for .

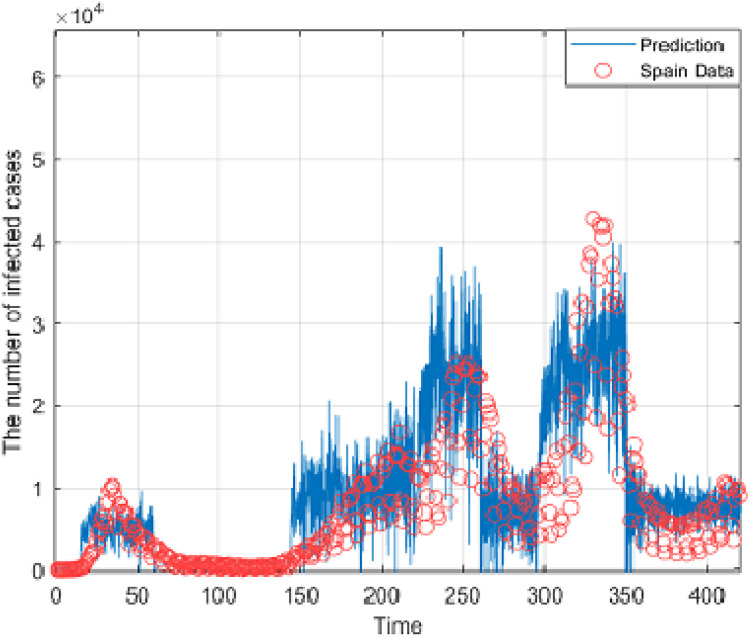

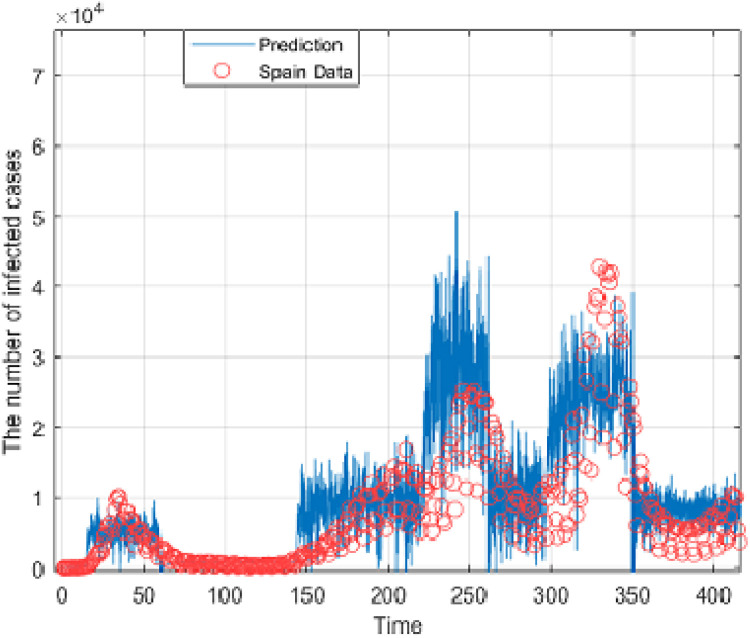

Comparison between piecewise model and real data in Spain

In this subsection, we present a comparison between the daily number of cases on 23 February and 20 April 2021 in Spain and the model that is divided into 9 pieces [24]. To do comparison, considering above notations, we consider the following model

| (65) |

| (66) |

The parameters and initial conditions are as follows

| (67) |

and

| (68) |

The simulations for comparison are provided using above initial data and parameters in Fig. 33, Fig. 34. The theoretical parameters used here are those that matched with experimental data. The initial conditions are chosen from Spain population and initial numbers of infected individuals.

Fig. 33.

Comparison between piecewise model and real data in Spain for .

Fig. 34.

Comparison between piecewise model and real data in Spain for .

Conclusion

Nature can be better understood or even predicted if the limitations of existing theories, approaches, methods are questioned, revised and updated. This is also the Case in epidemiological modeling, for many decades several theories have not been revisited but are still used even to analyze complex problems that cannot be really understood using existing theories. For example, how can we predict waves for a given infectious disease using existing methods? Although significant results have been suggested and some highly informative, however, when looking at the spread of Covid-19, especially data from some countries, one will quickly realize that some of them exhibit crossover behaviors, for example a passage from patterns with deterministic features to stochastic. We have attempted to open a new window of modeling such problems, by using the concept of piecewise modeling. We present some illustrative examples. The agreement of the piecewise models and experimental data let no doubt that this approach will help mankind to better predict crossover behaviors appearing in nature.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Atangana A., Baleanu D. New fractional derivatives with non-local and non-singular kernel, theory and application to heat transfer model. Therm Sci. 2016;20(2):763–769. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caputo M., Fabrizio M. On the notion of fractional derivative and applications to the hysteresis phenomena. Meccanica. 2017;52(13):3043–3052. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atangana A., Igret Araz S. New concept in calculus: Piecewise differential and integral operators. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2021;145 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thabet S.T.M., Abdo M.S., Shah K., Abdeljawat T. Study of transmission dynamics of Covid-19 mathematical model under ABC fractional order derivative. Results Phys. 2020;19:2020. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2020.103507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao W., Veeresha P., Baskonus H.M., Prakasha D.G., Kumar P. A new study of unreported cases of 2019-nCov epidemic outbreaks. Chaos Solitons Fractasl. 2020;138:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atangana E., Atangana A. Facemasks simple but powerful weapons to protect against Covid-19 spread: Can they have sides effects? Results Phys. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2020.103425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan M.A., Atangana A., Alzahrani E. The dynamics of Covid-19 with quarantined and isolation. Adv Difference Equ. 2020;(1):1–22. doi: 10.1186/s13662-020-02882-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghanbari B. On forecasting the spread of the Covid-19 in Iran: The second wave. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;140 doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atangana A., Igret Araz S. Nonlinear equations with global differential and integral operators: Existence, uniqueness with application to epidemiology. Results Phys. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atangana A., Igret Araz S. 2021. Deterministic-stochastic modeling: A new direction in modeling real world problems with crossover effect. hal-03201318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deborah D. Mathematical model for the transmission of Covid-19 with nonlinear forces of infection and the need for prevention measure in Nigeria. J Infect Dis Epidemiol. 2020;6(5):6:158. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh H., Srivastava H.M., Hammouch Z., Nisar K. Numerical simulation and stability analysis for the fractional-order dynamics of COVID-19. Results Phys. 2021;20 doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2020.103722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamou A.A., Azroul E., Hammouch Z., Alaoui A.L. On dynamics of fractional incommensurate model of Covid-19 with nonlinear saturated incidence rate. MedriXv. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamou A.A., Azroul E., Hammouch Z., Alaoui A.L. A fractional multi-order model to predict the COVID-19 outbreak in Morocco. Appl Comput Math. 2021;20(1):177–203. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamou A.A., Azroul E., Alaoui A.L. Fractional model and numerical algorithms for predicting COVID-19 with isolation and quarantine strategies. Int J Appl Comput Math. 2021;7(4):142. doi: 10.1007/s40819-021-01086-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danane J., Allali K., Hammouch Z., Nisar K.S. Mathematical analysis and simulation of a stochastic COVID-19 Lévy jump model with isolation strategy. Results Phys. 2021;23 doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2021.103994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gao W., Baskonus H.M., Shi L. New investigation of bats-hosts-reservoir-people coronavirus model and application to 2019-nCoV system. Adv Difference Equ. 2020;2020:391. doi: 10.1186/s13662-020-02831-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goufo E.F.D., Khan Y., Chaudhry Q.A. HIV and shifting epicenters for COVID-19, an alert for some countries. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;139 doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babaei A., Jafari H., Ahmadi M. A fractional order HIV/AIDS model based on the effect of screening of unaware infectives. Math Methods Appl Sci. 2021;44(13) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao Y., Jiang D. The threshold of a stochastic SIRS epidemic model with saturated incidence. Appl Math Lett. 2014;34:90–93. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao Y., Jiang D. The threshold of a stochastic SIS epidemic model with vaccination. Appl Math Comput. 2014;243:718–727. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Din A., et al. Mathematical analysis of dengue stochastic epidemic model. Results Phys. 2020;19 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atangana A., Araz S.I. Academic Press, Elsevier; 2021. New numerical scheme with Newton polynomial: Theory, methods and applications. [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization, WHO Coronavirus Disease (Covid-19) Dashboard, https://covid19.who.int/table.