We thank Kampkuiper et al for their insightful comments. In general, we agree with their comments.

Placing the sacroiliac fusion devices so that they are fully contained within the bone with no neural impingement is the first constraint in construct design. Implant malposition is the most common reason for revision surgery with Cher et al1 reporting it to be about 1%. This appears to have improved slightly from 2010 to 2014 (1%–0.9%). In a follow-up study, Cher et al2 reported an overall revision rate of 3% for cases performed between 2015 to 2018. Out of 14,210 cases, 435 underwent revisions. Of these, 54% were for symptomatic implant malposition, which implies a 1.6% implant malposition rate.

The senior author has done all of his cases using intraoperative navigation. It is also routine to do a postimplant placement check scan prior to leaving the operating room. This began in 2010. Having done >270 primaries (average 2.8 implants per case) and >60 revision cases, there have been well over 1000 implants placed. Of those implants, 2 needed repositioning. This corresponds with the Kampkuiper et al’s comments citing Cleveland.

The key to being able to achieve the desired implant placement is the individual bony anatomy. Women typically only have S1 and S2 articulations, whereas men typically have S1-S3 articulations. In addition, the rate of occurrence of dysmorphic sacra (Figure 1) is reported by Matson et al to be between 3.9% and 35.6% of the population.3

Figure 1.

Dysmorphic sacrum as indicated by the upsloped sacral ala.

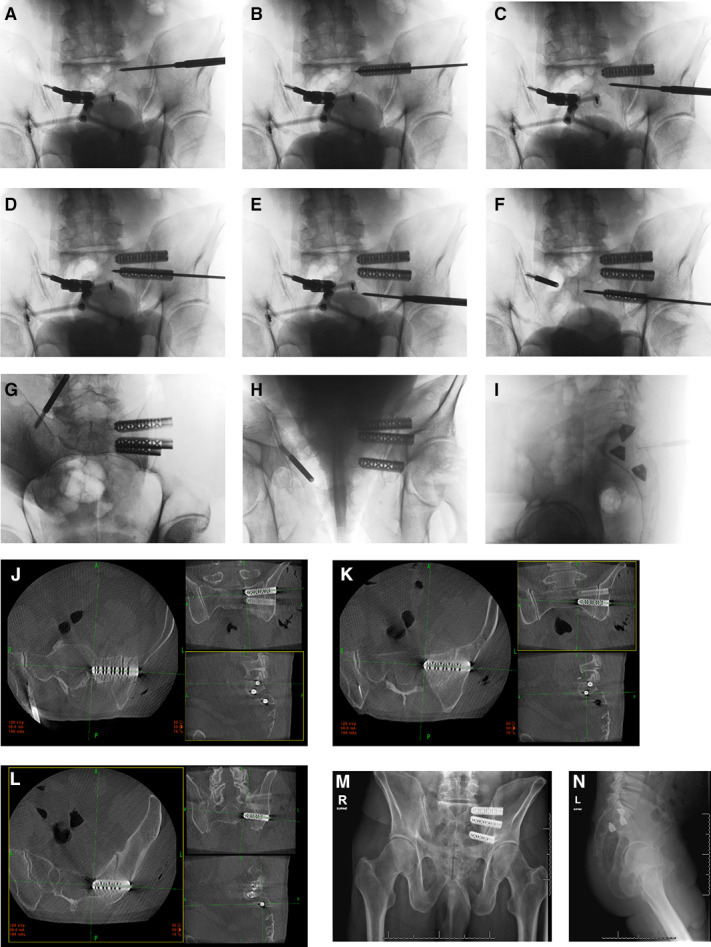

In normal morphology pelves (Figure 2), it is the senior author’s experience that the cephalad S1 implant is positioned parallel to the sacral ala (Figure 3). The caudal S1 implant is then angled parallel to the ventral sacral cortex. The S2 implant is then placed in what would be a through-and-through trajectory of the S2 corridor. This allows for inadvertent pin advancement without the risk of neural injury (Figure 3). We then routinely do 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional check images to ensure optimal placement. This case probably represents the maximum achievable between device angulation and distance. This is in agreement with the diagram and thoughts from Kampkuiper et al.

Figure 2.

Normal morphology sacrum.

Figure 3.

Intraoperative imaging and device placement with 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional imaging.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge SI Bone for donating the implants and financial support for the original study.

References

- 1. Cher DJ, Reckling WC, Capobianco RA. Implant survivorship analysis after minimally invasive sacroiliac joint fusion using the ifuse implant system(®). Med Devices (Auckl). 2015;8:485–492. 10.2147/MDER.S94885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cher D, Wroe K, Reckling WC, Yerby S. Postmarket surveillance of 3D-printed implants for sacroiliac joint fusion. Med Devices (Auckl). 2018;11:337–343. 10.2147/MDER.S180958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Matson DM, Maccormick LM, Sembrano JN, Polly DW. Sacral dysmorphism and lumbosacral transitional vertebrae (LSTV) review. Int J Spine Surg. 2020;14(Suppl 1):14–19. 10.14444/6075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]