Abstract

Purpose

The mental health situation among adolescents in Malaysia has reached a worrying state with the rising number of cases. Despite a significant increase in the literature on mental health, there is a lack of studies that focused on mental health awareness. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the factors affecting Malaysian youth’s mental health awareness as well as the mediating roles of knowledge on mental health, knowledge on professional help, and attitude towards mental health.

Methods

Self-administered questionnaires were distributed to 450 secondary school students aged 15–19 years old in Kuala Lumpur and Melaka who were recruited via purposive sampling. Data analysis was performed using SPSS and SmartPLS to obtain the descriptive analysis, measurement model, and structural model.

Results

The results indicated that mental health awareness was influenced by knowledge on mental health and attitude towards mental health. The findings also revealed that familiarity and media exposure were important determinants of knowledge on mental health, knowledge on professional help, and attitude towards mental health. Moreover, the results indicated that knowledge on mental health positively mediated the relationship between media exposure and mental health awareness. Besides, attitude towards mental health also found to play mediating roles between familiarity and mental health awareness, as well as between media exposure and mental health awareness.

Conclusion

This study contributed important knowledge to the limited literature in this contemporary domain. An effective public mental health campaign is needed to reduce the burden of disease and the cost of mental illness.

Keywords: Mental health awareness, Knowledge on mental health, Knowledge on professional help, Attitude towards mental health, Adolescents, Malaysian youth

1. Introduction

Mental health does not discriminate. Anyone, regardless of age, gender, ethnicity, social class, or income level, can be affected. According to Ritchie et al. [1], about 792 million people (10.7%) suffered from mental health issues. In other words, one in ten people suffered from mental health disorders globally. Mental health disorders may manifest in many forms, including but not limited to depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, and schizophrenia. Anxiety is the most common mental illness in the world, affecting 284 million people. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) [2], 17% of the affected population is aged between 10 and 19 years. Mental illness is estimated to account for 16% of the global burden of disease and injury among people within this age range. Research suggested that the prevalence of several mental health problems (the most common being depression and anxiety) was negatively correlated with self-reported life satisfaction. In other words, people with mental illnesses experienced lower life satisfaction and happiness [1]. Other than that, serious mental health issues can lead to suicide. Ferrari et al. [3] revealed that an individual with depression would be 20 times more likely to die from suicide. Individuals with anxiety, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and anorexia were around 3 times, 13 times, 6 times, and 8 times more likely to die from suicide than someone without these mental disorders.

In Malaysia, the National Health and Morbidity Survey 2017 (NHMS 2017) [4] conducted among more than 30,000 Malay, Chinese, and Indian secondary school adolescents between 13 and 17 years old reported that the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress as 18.3%, 39.7%, and 9.6% respectively. In other words, 1 in 5 adolescents was found to be depressed, 2 in 5 were anxious, and 1 in 10 were stressed. The same survey also showed that 10% of students have suicidal thoughts, an increment from 7.9% in 2012. According to the latest National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS 2019) [5], 2.3% or about half a million adults aged 18 and above in Malaysia suffered from depression. Females (2.7%) were more prone to depression than males (2.0%). Meanwhile, a total of 4,24,000 Malaysian children aged 5–15 years suffered from mental health problems, which was more than the prevalence reported in 2015. Based on the Healthy Mind Programme (Program Minda Sihat) held by the Ministry of Education in 2017, 5104 out of 284,516 students received interventions from school counselors for mental health issues, out of which, 14 were referred to a doctor in a hospital or health clinic. These surveys indicated an alarming deterioration of mental health status among Malaysian teenagers.

Adolescence is a critical developmental stage when a person's identity is established and the groundwork for future mental health is laid [6,7]. The onset of psychological issues such as depression can happen during this period of life because the transition from childhood to adolescence often involves substantial mental and biological changes [8]. An adolescent is also someone who starts to have more independence and adult responsibilities, besides developing decision-making abilities. Therefore, learning and adopting the right knowledge and behaviour regarding mental health at this stage would allow teenagers to have better mental health literacy and to make a better decision about their mental health [9]. Thus, it is very important to start instituting mental health awareness in adolescents.

According to WHO [2], half of all mental health issues began by the age of 14 but the majority of cases went unaware and untreated. Unlike other physical illnesses, Mental health illness is less obvious. There is still a lack of knowledge about mental disorders among teenagers, particularly in terms of the types of mental disorders. Therefore, misconception, stigma, and discrimination remain pervasive. It is vital to advocate mental health awareness so that affected adults and children do not have to suffer alone. Awareness is a form of education [10]. People can manage the symptoms and get proper treatment when they have a basic knowledge on mental health [11]. Greater awareness about mental health and early diagnosis can help to prevent teenage students from suffering mental health problems. Studies have also shown that awareness can lead to positive outcomes on mental health issues [12,13].

Despite a large rise in mental health literature, most of the studies focused on the subject of mental health awareness itself, rather than factors that influenced mental health awareness, such as the recent studies on awareness of mental health by Dev et al. [14], Swetaa et al. [15], and Uddin et al. [16]. Other studies [17,18] concentrated on the prevalence of mental health problems, factors that contributed to mental health problems [19,20], and the literacy of mental health [21,22]. Studies examining the effect of knowledge on mental health, knowledge on professional help, and attitude towards mental health on mental health awareness remain scarce. The mediating effects of knowledge on mental health, knowledge on professional help, and attitude towards mental health on the relationships of both familiarity and media exposure with mental health awareness are also unclear. Furthermore, there are limited numbers of studies using social learning theory to explain awareness in their framework [23,24]. There are also no extant studies that examine the influence of the factors of social learning theory on mental health awareness. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the associated factors of mental health awareness and the mediating roles of knowledge on mental health, knowledge on professional help, and attitude towards mental health.

2. Literature review

2.1. Social learning theory

The Social Learning Theory (SLT) was first developed by Rotter [25]. It asserts that people develop as a result of constant interaction between the individual and the environment. It builds on the tenants of behaviourism (environmental stimulus) and cognitive learning theories (internal processes). SLT promotes the idea of interaction built on triadic reciprocity [26]. Behaviour, cognition, and other personal characteristics, as well as environmental influences, all function as interwoven determinants that can impact one another in this concept of reciprocal determinism. Reciprocity does not imply that the two sides of the influence are equally powerful. In reciprocal causation, neither the patterning nor the degree of mutual impacts is fixed. The relative effect of the three interlocking factors can change depending on the activity, the individual, and the circumstances [27]. The person refers to personal individual cognitive elements; the environment comprises both physical and social environments; whereas the behaviour refers to the actions of an individual [28]. Previous research by Stutz [23] applied SLT to explore the relationship between personal cognitive factors and environmental factors with student loan debt awareness to gain more understanding of the way students make sense of student loan debt. In Stutz’s [23] study, the personal factors included financial anxiety, financial risk tolerance, subjective financial knowledge, and perceived control. Meanwhile, the environmental factors included parent financial socialisation, peer influence, college major, and demographic factors. The findings highlighted the theoretical interplay between environmental factors and personal factors, as well as how they may impact the cognitive mechanisms involved in awareness navigation.

2.2. Mental health awareness

Mental health awareness refers to having recognition, knowledge, and understanding of mental health. It is also known as mental health literacy [14]. Wei et al. [29] divided mental health literacy skills into three key areas, i.e. knowledge on mental health problems, development of good mental health, and knowledge of help-seeking behaviours. Meanwhile, Jorm et al. [30] defined mental health literacy skills under the six attributes of i. able to distinguish the symptoms of various mental disorders, ii. able to determine the factors of disorders, ii. having positive attitudes towards mental health problems and help-seeking behaviour, iv. practicing self-care, v. searching for information on mental health, and lastly, vi. seeking help from professionals. From these concepts of mental health literacy, it is understood that improving people’s knowledge on mental health and mental disorders is important for early recognition and the right treatment of the disorder [14]. Coles et al. [31] stated that a higher level of mental health literacy can improve access to mental health services. Besides, mental health literacy will also decrease the level of stigma. Del et al. [32] reported that by providing mental disorder awareness and education for teenagers, their stigma against mental disorders became significantly lower.

According to Patel et al. (2015) and Rebello et al. [13] mental health awareness campaigns that include literacy programmes and awareness interventions have shown fruitful results. Bamgbade et al. [33] discovered that the mental health knowledge of pharmacy students improved after the mental illness stigma awareness intervention. This finding was supported by Lindow et al. [34] who discovered that students' general knowledge on mental health had increased over time after the “Youth Aware of Mental Health” intervention. Mental health literacy influences positive help-seeking behaviour [35]. Coles et al. [31] observed that when adolescents understand mental illnesses better, they are more likely to advocate for help-seeking. For instance, if adolescents can recognise depression better than social anxiety, then they will be more likely to recommend individuals with depression to seek help.

Additionally, negative mental health attitudes can be mitigated partly by mental health literacy. Svensson and Hansson [36] discovered that individuals with better mental health literacy are less inclined to distance themselves from mental health patients. In contrast, people with a poor understanding of mental health tend to have negative attitudes and stigma against mental health patients as they do not grasp the real nature of the mental illness, cannot recognise possible risks, are unable to acknowledge signs of mental illness, and cannot interpret psychiatric term [22,[37], [38], [39]]. Overall, mental health literacy is correlated with mental wellbeing and physical health. Therefore, the higher the mental health literacy of a person, the better his mental wellbeing and physical health.

2.3. Familiarity

Familiarity is described as having knowledge and experience of mental illness [40]. It can range from having no experience and exposure at all, seeing mental illness portrayed on television, having contact with friends and colleagues with mental illness, to having mental illness personally [41]. Various studies have revealed that personal experiences of mental illness will affect the knowledge on mental health. Tahir et al. [42] and Jorm et al. [30] reported a connection between personal experience with depression with a greater understanding of the signs of depression and the therapy needed. Besides, Berry et al. [43] found that people who did not identify themselves as having mental health issues showed little understanding of mental health. Individuals with personal mental disorders usually have higher literacy on mental health due to the advice given by mental health professionals or prior experience with mental health illness and treatment. Furthermore, having personal contact with mental disorder sufferers also demonstrated increased knowledge on mental health [44]. According to Abi Doumit et al. [45], personal contact and experience with mentally ill people could lead to a greater knowledge of mental disorders. This finding was in line with Ahmed and Baruah [46]and Piper et al. [47] which indicated that individuals with personal contact with mentally ill patients often know more about mental illnesses as they experienced some of the signs, symptoms, and treatment when accompanying the patients. Therefore, the following hypothesis was derived for this research:

H1

Familiarity has a positive influence on the knowledge on mental health.

Research has shown that familiarity affects help-seeking attitudes. Fischer and Farina [48] reported a strong relationship between personal experiences such as previous help-seeking behaviours with present positive intentions or behaviours to pursue psychological help among college students. In other words, college students who have previously sought psychological help are more likely to have the intention or behaviour to pursue psychological help. Researchers further indicated that this positive correlation was associated with greater knowledge of and openness toward mental health services among those with a history of help-seeking [49]. According to Abi Doumit et al. [45] as well as Ahmed and Baruah [46], personal contact with mentally ill patients or experiencing of mental illness resulted in greater knowledge as they received sufficient information about professional help. Therefore, the below hypothesis is formulated:

H2

Familiarity has a positive influence on the knowledge on professional help.

Familiarity and experience with individuals suffering from mental illness are among the most important factors affecting attitudes and behaviours [50]. Studies have shown a negative correlation between having contact with someone who has a mental disorder and endorsing psychological stigma. In other words, the more contact a person has with someone with a mental disorder, the less likely would the person holds a stigma against individuals with mental disorders [40,41,51]. Abi Doumit et al. [45] discovered a positive correlation when accessing familiarity with friends, close, and distant people in relation to attitudes and behaviours. The findings were in line with previous studies in which personal experience with mental illness sufferers gave rise to more positive attitudes [52]. As a matter of fact, people with family members who experience mental disorders are more compassionate and have a more positive attitude than those without mentally ill family members. Similarly, people who have had a mental health condition are also more familiar with mental disorders and displayed fewer stigmatising attitudes. Roth et al. [53] investigated the influences of personal and professional experiences with mental illness on attitudes toward mental illness. They discovered that people with personal or professional experience with mental illness, be it within themselves, among family members or friends, have a more positive attitude towards people with mental illness than those without such experience. Besides, Svensson and Hansson [36] also suggested that individuals without personal contact with mental illness sufferers were linked to greater self-stigma. Thus, it is hypothesised that:

H3

Familiarity has a positive influence on the attitude towards mental health.

2.4. Media exposure

Media exposure is defined as the degree to which the audiences come across specific messages or media content [54]. The media has been a source of mental health information for the public. In a survey of knowledge of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and autism in France, one-third of the respondents rated media as a more frequent source of information compared to doctors, health professionals, or other public service agencies [55]. Besides, Li et al. (2018) found that over half of their study respondents reported mass media as the major source of their information and knowledge regarding the mental disorder. Jafari et al. [56] obtained similar results. Thus, mass media may be a relevant source of information for individuals who have no prior experience with people with mental disorders. Information from mass media may affect their views and attitudes about mental illnesses [44]. Thus, mass media is an effective platform to raise people's knowledge about a particular subject. For instance, research in the area of HIV agreed that mass media is an important avenue in increasing an individual’s knowledge of sexual health, apart from strengthening individual’s knowledge of HIV prevention services and emphasising the benefits of HIV testing [57,58]. Hence, the below hypothesis is proposed:

H4

Media exposure has a positive influence on knowledge on mental health.

Sano et al. [58] reported that the media led to an increase in HIV knowledge and subsequently HIV testing facilities due to the demand that was created for HIV testing. Calvert [59] further affirmed that exposure to quality media content would lead to positive educational effects. Other findings also showed that media promoted help-seeking and coping skills by advancing public knowledge via sharing of stories and experiences of those with mental illness as well as interviews with experts on various educational websites [[60], [61], [62], [63]]. Furthermore, media exposure to mental health issues will also improve public awareness of the illness and its potential negative effects. As a result, people will be more driven to seek more information about the illness, such as the causes, risks, and treatments, thus improving their knowledge of the particular topic [64]. People with more knowledge will seek treatment and engage in preventive measures when suffering from the illness [65]. In line with this, McCrae et al. [66] noted that several popular newspaper reports that focused on the topic of mental health treatment and recovery played a key role in informing readers of the advancements in mental health care, subsequently breaking down the barriers to seeking help. Other studies also revealed that many individuals turned to social media to seek knowledge about mental health treatment choices [67]. Therefore, the below hypothesis is formulated:

H5

Media exposure has a positive influence on knowledge on professional help.

Mass media plays critical functions in society as it shapes culture, influences politics, affects the attitude of people, and takes on an important role in raising concerns about health issues [68]. Li et al. [44] stated that mass media is an important source of information for individuals who have no prior experience with people with mental disorders. Media reports may affect their views and attitudes about mental illnesses. Mass media exposure not only fosters awareness and improves knowledge, but it also plays a part in improving beliefs and reinforcing current attitudes [59,69]. Furthermore, media plays a part in alleviating stigma and correcting misinformation [60,70]. On the other hand, the media is also influential in challenging public stigma, encouraging public debate and discussion, and demonstrating positive stories of those who live with mental health issues [71]. Findings from three studies that compared the impacts of positive, neutral, or negative published news coverage consistently found that positive reports that challenged stigma were insightful, recovery-centred, and more likely to result in a decline in stigmatising attitudes. In contrast, negative reports that involved violent and dangerous stereotypes have raised stigmatising attitudes [[72], [73], [74]]. Furthermore, according to an overview of reader responses on online news articles, articles that shared positive facts about mental illness were more likely to elicit encouraging and stigma-challenging comments, whereas reports that correlated mental illness with aggressive behaviours and quoted individuals with mental disorders were more likely to elicit stigmatising comments [74]. Therefore, the following hypothesis is derived:

H6

Media exposure has a positive influence on attitudes toward mental health.

2.5. Knowledge on mental health

Knowledge on mental health refers to the knowledge of the signs, symptoms, causes, and outcomes of mental health as well as the ability to recognise and label types of mental disorders [75]. Numerous studies have shown that the general population still lacks knowledge about mental health. With respect to the degree of knowledge the general public hold regarding mental health, Mahto et al. [76] stated that the student population was the most uninformed about mental health. The rate of health literacy, particularly mental health literacy, is low in most developing countries such as Malaysia. According to the National Health and Morbidity Survey 2015 by Institute for Public Health [77], only 5.1% of secondary school students had sufficient mental health literacy. However, students are not the only group who lack knowledge on mental health. Webb et al. [78] indicated that stigmatising views were also common among older adults. The most common misconception regarding mental health among older adults is that people are responsible for their mental illnesses. Another existing misconception was that mental health problems such as depression and anxiety disorders do not affect children, in which more than half of the respondents dismissed the notion that their child may be prone to mental health problems based on a study by Yeap and Low [22]. According to Corrigan and Shapiro [79], better awareness can arise from greater knowledge. Jabar et al.’s [80] observed a linear association between the awareness and knowledge of Muslim retailers toward halal cosmetic products. The outcome observed a total variance of 33%, implying that 33% of the awareness can be explained by knowledge. Similarly, Rajamoorthy et al. [81] revealed that knowledge and awareness of hepatitis B were positively correlated among Malaysian households. It is further stated that individuals who possessed more knowledge have 2.5 times more tendency to acquire awareness. Thus, it is hypothesised that:

H7

Knowledge on mental health has a positive influence on mental health awareness.

2.6. Knowledge on professional help

Knowledge on professional help refers to the knowledge of professional resources that are available when seeking help when facing any mental health issues. It can also be defined as knowledge on mental health professionals and the services they provide [82]. Not seeking the necessary help can lead to negative consequences such as suicide. The risk of suicide is higher in youth as they are the least likely to seek help. Studies showed that a higher level of suicidal ideation is commonly associated with help negation, i.e. avoidance of help-seeking from friends, family, or medical professionals [83]. Jorm et al. [84] performed a study on the beliefs surrounding the appropriate first aid for young people with mental disorders. The results showed that a substantial number of adolescents did not think that professional help is beneficial. Some parents also did not support seeking professional help due to poor mental health literacy. In many cases, poor mental health literacy turned out to be the primary barrier to help-seeking among youth who face mental health problems, according to a systematic review by Gulliver et al. [85] and Radez [86]. In addition, poor knowledge regarding the signs of mental illness will prevent people from getting appropriate help for their mental health conditions [87]. Lack of knowledge about mental health services is another obstacle worth mentioning [88]. Getting mental health treatment requires knowing where to find such services and how they work. It is appropriate to assume that those with sufficient knowledge about professional help possess a certain amount of mental health awareness since the knowledge on professional help and treatment is a crucial component of mental health literacy or awareness. Therefore, the following hypothesis is derived:

H8

Knowledge on professional help has a positive influence on mental health awareness.

2.7. Attitude towards mental health

Attitude towards mental health represents individuals' evaluation and beliefs about mental health issues [22]. Attitudes towards various mental disorders, including the definitions and the associated stigma, are believed to take shape at a younger age [89]. A review of children’s attitudes towards those with mental illness suggested that children as young as five years old already viewed mentally ill individuals in a negative manner [90]. The review also showed that the conceptualisation of mental illness was less complex among younger children than adolescents. Even though older children have a better understanding of mental illness than younger children, they tend to have a greater negative attitude toward the mentally ill than younger children. The research concluded that negative attitudes increased with age in both children and adolescents. This finding was supported by Kaushik et al.’s [91] systematic review of the stigma of mental illness among children and adolescents. Apart from that, youth are reluctant to interact with mentally ill individuals and tend to keep a distance from them. Evidence of negative attitudes and stigma has been reported in various studies. According to Pang et al. [92], almost half of the study participants associated negative words with mental illness. The general public is not the only one who would have a negative perception of those with mental disorders, even well-trained mental health professionals who were supposed to be more open-minded expressed negative attitudes and stigmatisation towards mentally ill patients [93]. This was supported by Eissa et al. [94] who observed that some medical students and doctors viewed mentally ill patients as different, dangerous, unpredictable, and hard to communicate with. So far, there is a lack of study on the relationship between attitude and awareness in the context of mental health. Therefore, studies in other contexts such as environmental awareness must be referred to when evaluating the relationship between attitude and awareness. Sabouhi et al. [95] found a strong association between attitude and awareness in their study on the knowledge, awareness, attitudes, and practice of hypertension among hypertensive patients. Besides, Zhao et al. [96] reported a positive relationship between energy-saving attitudes and energy-saving awareness among university students. Hence, the below hypothesis is proposed:

H9

Attitude towards mental health has a positive influence on mental health awareness.

2.8. The mediating role of knowledge on mental health

Various research showed that having a familiarity with mental health issues, be it through personal experience with mental illness or having contact with a person with mental illness can impact their mental health knowledge [42,45,46]. Besides, the media has been a source of information for the public regarding mental health. It is evident in the research by Li et al. [44] in which most of the respondents gained information and knowledge about mental health through media. Moreover, many studies have shown a correlation between knowledge and awareness [95,97]. Thus, the following hypothesis is posited:

H10

Knowledge on mental health mediates the relationship between familiarity and mental health awareness.

H11

Knowledge on mental health mediates the relationship between media exposure and mental health awareness.

2.9. The mediating role of knowledge on professional help

According to Abi Doumit et al. [45] and Ahmed and Baruah [46], having a familiarity with mental health issues can result in greater knowledge since it is associated with sufficient information concerning professional help. Media exposure to mental health issues will raise people's knowledge of mental illnesses and increase their desire to learn more about mental health treatment and care, therefore increasing their overall knowledge of the subject [64]. On the other hand, individuals with knowledge on professional help possessed a certain level of mental health awareness. Individuals who know about mental health treatment, where and who to seek help from are considered to be equipped with basic awareness of mental health. Thus, the research hypotheses formed are:

H12

Knowledge on professional help mediates the relationship between familiarity and mental health awareness.

H13

Knowledge on professional help mediates the relationship between media exposure and mental health awareness.

2.10. The mediating role of attitude towards mental health

Abi Doumit et al. [45] observed a positive link while assessing familiarity with friends, and close and distant individuals in connection to attitudes and behaviours. Ewalds-Kvist et al. [52] study found that people who suffer from mental health problems are more familiar with mental disorders and have less stigmatised attitudes towards them. Meanwhile, mass media provides a source of information that reflects and shapes public attitudes and values by reducing stigma and correcting misinformation [60,70,98]. According to Rickwood [99], awareness is strongly affected by attitudes toward mental illness in the community and services. Low awareness is caused by stigma and a lack of understanding of mental illness. Therefore, it is hypothesised that:

H14

Attitude towards mental health mediates the relationship between familiarity and mental health awareness.

H15

Attitude towards mental health mediates the relationship between media exposure and mental health awareness.

2.11. Theoretical framework

With mental health awareness as the focus of this study, SLT was utilised because of its emphasis on the process of learning and therefore, the precursors to awareness [26]. According to SLT, behaviour or outcome is the consequence of the interaction between environmental stimuli and the individual's internal processes. Internal processes include attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, and personality, all of which are the results of prior learning and experiences. As an effect of the interaction between environment and internal processes, this cycle is continually evolving, resulting in the learning of new knowledge and shifting of attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge. As each individual has a unique awareness and understanding of mental health awareness based on their learning experiences, it is important to try to uncover influential interconnections during this learning process. A theoretical framework that identifies the building blocks of learning is, therefore, suitable to be used in investigating mental health awareness.

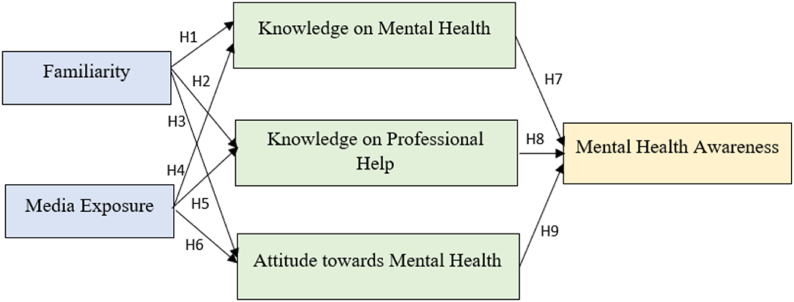

The theoretical framework as shown in Fig. 1 for this study indicated that mental health awareness is related to the social learning process that resulted from the reciprocal interaction of the individual (personal factor) with their environment (environmental factor). Environmental factors in this study included familiarity and media exposure while personal factors encompassed knowledge on mental health, knowledge on professional help, and attitude towards mental health.

Fig. 1.

Research framework.

3. Research methodology

The target population for this study was the youth from secondary schools in Kuala Lumpur and Melaka. As defined by the United Nations (UN) [100], youth are those between the ages of 15 and 24. Hence, purposive sampling was used to recruit 450 students from Kuala Lumpur and Melaka aged 15–19 years old. The online self-administered questionnaires were distributed to students from 12 secondary schools. All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Multimedia University (EA0232021).

The survey questionnaire consisted of four demographic items, namely gender, age, religion, and ethnicity. Familiarity was measured using the seven items adapted from Corrigan et al.’s [101] Level of Contact Report. Five items to quantify media exposure were derived from Wu and Li (2017). Knowledge on mental health was measured using the 16 items adopted from Yin et al.’s [75] Mental Health Knowledge Questionnaire (MHKQ). Three items from Nejatian et al. [82] were adapted to capture the knowledge on professional help. Furthermore, attitude towards mental health was measured using nine items derived from Yeap and Low [22]. Finally, mental health awareness was quantified using the five items adapted from Shah and Praveen [102]. All the independent variables were rated on a five-point Likert scale with 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = neither agree nor disagree; 4 = agree and 5 = strongly agree. Meanwhile, the measurement for mental health awareness applied a ten-point Likert scale from 1 = not at all aware to 10 = extremely aware. SPSS was used to obtain the descriptive analysis. SmartPLS was used for structural equation modelling (SEM). The constructs were validated in the measurement model. Their relationships and mediating effect were tested in the structural model. This study followed Preacher and Hayes [103] method of testing mediation which focused mainly on testing indirect effects, without testing the direct relationship between X and Y.

4. Data analysis and findings

A total of 450 respondents participated in this study, with the majority being females (61,8%, n = 278). More than one-third (37.3%) of them were age 16 years old, followed by 17 years old (22.7%), 15 years old (20.0%), and lastly, 18 and 19 years old (10.0%). Most of the respondents were Malay (48.4%, n = 218), while 35.6% were Chinese and 13.6% were Indians. About half of the respondents were Muslim (49.3%), followed by 137 Buddhists (30.4%) and 53 Hindus (11.8%). The remaining respondents included 7.3% of Christians and others.

4.1. Convergent validity

The convergent validity of the model was verified by the factor loadings with a minimum value of 0.7, average variance extracted (AVE) of 0.5, and construct reliability (CR) of 0.7 [104]. Table 1 shows that most of the standardised factor loadings were greater than 0.7 except ATT4 (0.547), ATT6 (0.616), ATT7 (0.614), FAM2 (0.548), KMH5 (0.698), KMH6 (0.556), KMH9 (0.683), KMH12 (0.572), KMH14 (0.621), KMH15 (0.682), KPH3 (0.683), and MED5 (0.689). However, these items were retained because of their contribution to content validity [105]. Items with poor loadings factors (<0.5) such as ATT1, FAM3, FAM4, FAM5, FAM6, and FAM7 were deleted. The CR items were within a range of 0.753–0.951 and fulfilled the criterion of above 0.7 [104]. This confirmed the indicators' internal reliability consistency. The convergent validity was further verified by AVE which tested the commonality of the construct [104]. The AVE obtained was in the range of 0.508–0.696 which exceeded the minimum value of 0.5. Thus, the convergent validity of these constructs was deemed adequate.

Table 1.

Convergent validity.

| Construct | Items | Statements | Factor Loadings | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude Towards Mental Health | ATT2 | A person who has visited a psychologist’s office does not necessary mean he/she is a person with mental disorder. | 0.713 | 0.890 | 0.508 |

| ATT3 | Anyone can suffer from mental health problems. | 0.783 | |||

| ATT4 | Talking to someone with mental health problems is the same as talking to anyone else. | 0.547 | |||

| ATT5 | People need to adopt a more caring and sympathetic attitude towards people with mental health problems. | 0.709 | |||

| ATT6 | People with mental health problems are not dangerous/violent. | 0.616 | |||

| ATT7 | Most people with mental health problems recovered. | 0.614 | |||

| ATT8 | People with mental health problems should have the same rights as anyone else. | 0.836 | |||

| ATT9 | People with mental health problems should not be blamed for their own condition. | 0.825 | |||

| Mental Health Awareness | AWARE1 | How aware are you of mental health? | 0.883 | 0.920 | 0.696 |

| AWARE2 | How aware are you of the causes of mental health problems? | 0.880 | |||

| AWARE3 | How aware are you of the signs and symptoms of mental health problems? | 0.831 | |||

| AWARE4 | How aware are you of the ways to prevent mental health problems? | 0.813 | |||

| AWARE5 | How aware are you of where to seek consultation and treatment for mental health problems? | 0.759 | |||

| Familiarity | FAM1 | I have watched a television show that included a person with mental illness. | 0.971 | 0.753 | 0.621 |

| FAM2 | I have observed a person with severe mental illness. | 0.548 | |||

| Knowledge on Mental Health | KMH1 | Mental health plays a vital role in our overall health. | 0.793 | 0.951 | 0.550 |

| KMH10 | If one is diagnosed with severe mental disorder such as schizophrenia, medication is needed to be taken continuously. (Schizophrenia is a brain disorder that affects how people think, feel, and perceive the reality.) | 0.708 | |||

| KMH11 | An optimistic attitude towards life, good interpersonal relationships and a healthy lifestyle are helpful to keep a good mental health. | 0.781 | |||

| KMH12 | People with a family history of mental disorders have a higher chance of developing mental disorders or mental problems. | 0.572 | |||

| KMH13 | Mental problems in adolescents does influence their academic achievement. | 0.841 | |||

| KMH14 | The possibility of mental problems or disorders is much higher among the middle and old age people. | 0.621 | |||

| KMH15 | Someone with an unstable temperament is more prone to have mental problems. | 0.682 | |||

| KMH16 | High psychological stress or major life events could induce mental problems or disorders. | 0.838 | |||

| KMH2 | Mental illnesses could be caused by something wrong in thoughts. | 0.788 | |||

| KMH3 | Most people may have a mental problem, but they may not notice the problem. | 0.762 | |||

| KMH4 | Mental illnesses could be caused by stress. | 0.836 | |||

| KMH5 | Mental health includes normal intelligence, stable mood, harmonious relationships, and good ability to adapt and so on. | 0.698 | |||

| KMH6 | Most mental illnesses patients could be cured. | 0.556 | |||

| KMH7 | Psychological or psychiatric services should be sought if one suspects the presence of psychological problems or a mental disorder. | 0.818 | |||

| KMH8 | Individuals at any age can have a mental problem. | 0.797 | |||

| KMH9 | Mental illnesses or psychological problems can be prevented. | 0.683 | |||

| Knowledge on Professional Help | KPH1 | Cognitive Behaviour Therapy is a therapy based on challenging negative thoughts and increasing helpful behaviours. | 0.848 | 0.800 | 0.574 |

| KPH2 | Mental health professionals have to reveal a patient’s health conditions to others in the case of one is at risk of creating harm to own-self and others. | 0.725 | |||

| KPH3 | Given that the patient mental health condition does not pose a serious threat to own’s and others' lives, the mental health professionals will not reveal patient’s health conditions to others in order for others to better support the patient. | 0.691 | |||

| Media Exposure | MED1 | I often watch television programmes on mental health. | 0.822 | 0.913 | 0.679 |

| MED2 | I often read about mental health articles from the newspaper. | 0.813 | |||

| MED3 | I often read/watch about mental health topics from the mobile phone apps or website. | 0.900 | |||

| MED4 | I often read/watch about mental health topics from the social media platform (ie: facebook, Instagram, twitter etc.). | 0.881 | |||

| MED5 | I often hear about mental health topics on the radio. | 0.689 |

Note: CR: Composite Reliability; AVE: Average Variance Extracted.

4.2. Discriminant validity

The discriminant validity is used to test whether a construct is unique, i.e., its measures are not too highly correlated with the other constructs in the same model. In this study, the discriminant validity was assessed using the Heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) criterion [106]. HTMT can be assessed by comparing the HTMT values obtained with the required threshold of HTMT.85 [107] or HTMT.90 [108]. Also, the HTMTinference should not contain the value 1. As shown in Table 2, all the values passed HTMT.90 and the HTMTinference did not show a value of 1, thus indicating discriminant validity.

Table 2.

Discriminant validity using HTMT criterion.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Attitude Towards Mental Health | ||||||

| 2. Familiarity | 0.396 | |||||

| (0.298, 0.472) | ||||||

| 3. Knowledge on Mental Health | 0.732 | 0.404 | ||||

| (0.645, 0.796) | (0.311, 0.497) | |||||

| 4. Knowledge on Professional help | 0.64 | 0.352 | 0.791 | |||

| (0.52.0.745) | (0.224, 0.489) | (0.706, 0.866) | ||||

| 5. Media Exposure | 0.357 | 0.545 | 0.422 | 0.476 | ||

| (0.262, 0.445) | (0.431, 0.661) | (0.345, 0.492) | (0.376, 0.564) | |||

| 6. Mental Health Awareness | 0.318 | 0.273 | 0.304 | 0.22 | 0.405 | |

| (0.232, 0.404) | (0.171, 0.375) | (0.208, 0.396) | (0.126, 0.317) | (0.327, 0.475) |

Note: The values in the brackets represent the 95% bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals derived from bootstrapping with 5000 samples.

4.3. structural model

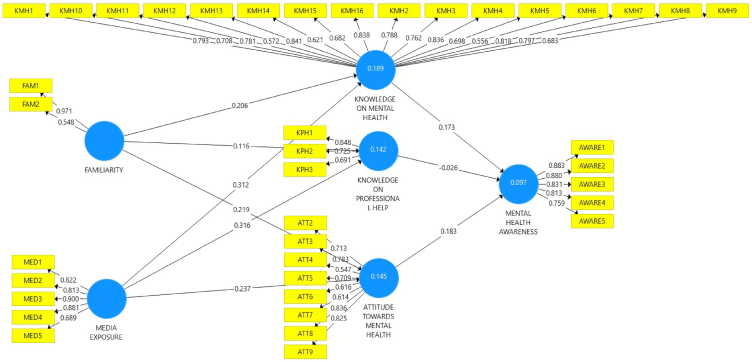

Table 3 and Fig. 2 show that out of the nine paths tested in the structural model, six paths were significant with t-statistics greater than the critical value of 2.326 (p-value < 0.01), and two paths were significant with t-statistics greater than the critical value of 1.645 (p-value < 0.05). The results indicated that eight out of nine hypotheses were supported, namely i. familiarity has a positive influence on knowledge on mental health (H1: β = 0.206, t-value = 4.452), ii. familiarity has a positive influence on knowledge on professional help (H2: β = 0.116, t-value = 2.239), ii. familiarity has a positive influence on attitude towards mental health (H3: β = 0.219, t-value = 3.979), iv. media exposure has a positive influence on knowledge on mental health (H4: β = 0.312, t-value = 6.950), v. media exposure has a positive influence on knowledge on professional help (H5: β = 0.316, t-value = 6.732), vi. media exposure has a positive influence on attitude towards mental health (H6: β = 0.237, t-value = 4.083), vii. knowledge on mental health has a positive influence on mental health awareness (H7: β = 0.173, t-value = 2.248), and vii. attitude towards mental health has a positive influence on mental health awareness (H9: β = 0.183, t-value = 3.197). On the other hand, Table 4 shows that the eighth hypothesis (H8) was not supported. Thus, the knowledge on professional help had no positive influence on mental health awareness as the effect was non-significant (H8: β = −0.026, t-value = 0.401).

Table 3.

Results of partial least square (direct effect).

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Std Beta | Std Error | t-value | Decision | R2 | Q2 | f2 | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Familiarity -> Knowledge on Mental Health | 0.206 | 0.046 | 4.452** | Supported | 0.189 | 0.099 | 0.044 | 1.178 |

| H2 | Familiarity -> Knowledge on Professional Help | 0.116 | 0.052 | 2.239* | Supported | 0.142 | 0.076 | 0.013 | 1.178 |

| H3 | Familiarity -> Attitude Towards Mental Health | 0.219 | 0.055 | 3.979** | Supported | 0.145 | 0.069 | 0.048 | 1.178 |

| H4 | Media Exposure -> Knowledge on Mental Health | 0.312 | 0.045 | 6.95** | Supported | 0.102 | 1.178 | ||

| H5 | Media Exposure -> Knowledge on Professional Help | 0.316 | 0.047 | 6.732** | Supported | 0.099 | 1.178 | ||

| H6 | Media Exposure -> Attitude Towards Mental Health | 0.237 | 0.058 | 4.083** | Supported | 0.056 | 1.178 | ||

| H7 | Knowledge on Mental Health -> Mental Health Awareness | 0.173 | 0.077 | 2.248* | Supported | 0.015 | 2.280 | ||

| H8 | Knowledge on Professional Help -> Mental Health Awareness | −0.026 | 0.065 | 0.401 | Not Supported | 0.000 | 1.619 | ||

| H9 | Attitude towards Mental Health -> Mental Health Awareness | 0.183 | 0.057 | 3.197** | Supported | 0.097 | 0.063 | 0.020 | 1.836 |

Note:** if p-value <0.01, * p-value <0.05.

Fig. 2.

Structural Model for this study.

Table 4.

Mediating analysis.

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Std Beta | Std Error | t-value | Confidence Interval (BC) |

Decision | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||||

| H10 | Familiarity -> Knowledge on Mental Health -> Mental Health Awareness | 0.036 | 0.019 | 1.865 | 0.010 | 0.073 | Not Supported |

| H11 | Media Exposure -> Knowledge on Mental Health -> Mental Health Awareness | 0.054 | 0.026 | 2.074** | 0.014 | 0.100 | Supported |

| H12 | Familiarity -> Knowledge on Professional Help -> Mental Health Awareness | −0.002 | 0.008 | 0.376 | −0.019 | 0.007 | Not supported |

| H13 | Media Exposure -> Knowledge on Professional Help -> Mental Health Awareness | −0.006 | 0.020 | 0.401 | −0.040 | 0.026 | Not supported |

| H14 | Familiarity -> Attitude Towards Mental Health -> Mental Health Awareness | 0.042 | 0.016 | 2.445** | 0.017 | 0.070 | Supported |

| H15 | Media Exposure -> Attitude Towards Mental Health -> Mental Health Awareness | 0.045 | 0.019 | 2.321** | 0.018 | 0.080 | Supported |

Note: ** if p-value <0.01, * p-value <0.05, BC = bias corrected, UL = Upper Level, LL = Lower Level.

R2 is a measure of the model’s explanatory power. Hair et al. [104] suggested that R2 values of 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25 are considered substantial, moderate, and weak respectively. The R2 values obtained for the knowledge on mental health, knowledge on professional help, attitude towards mental health, and mental health awareness were 0.189, 0.142, 0.145, and 0.097 respectively. All the R2 values were below 0.25, thus indicating that the model explanatory power was weak. This could be attributed to the inherently greater amount of unexplainable variation as the models in social or behavioural sciences are not expected to include all the relevant predictors to explain an outcome variable due to the unpredictability of human nature [109]. In this context, R-squared values are bound to be lower as many omitted predictors could have been able to explain the variation.

The effect size (f2) was also assessed. Cohen [110] suggested testing the model for f2 to quantify the means of two groups. According to Cohen [110], f2 with values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 are considered small, moderate, and large. All the effect sizes among the significant constructs were within the range of 0.020–0.102, thus considered as a small effect size as suggested by Cohen [110], except for two constructs, i.e. Familiarity -> Knowledge on professional help (f2 = 0.013) and Knowledge on mental health -> Mental Health Awareness (f2 = 0.015).

A blindfolding procedure was used to assess the predictive relevance. The model has a predictive relevance for a particular endogenous construct when Q2 was greater than 0 (Hair et al. [104]. The Q2 values obtained were 0.099, 0.076, 0.069, and 0.063, thus suggesting that the model had predictive relevance.

The variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to evaluate the collinearity of constructs. All the VIF values were between 1.619 and 2.280, less than 5 as suggested by Hair et al. [104], thus indicating no collinearity problem between the predictor constructs in the structural model.

4.4. Mediating effect test

This study also tested the indirect effects of knowledge on mental health, knowledge on professional help, and attitude towards mental health on the relationship between media exposure and mental health awareness, as well as the relationship between familiarity and mental health awareness. Table 4 shows that three indirect effects were supported, i.e., the relationship between media exposure and mental health awareness was mediated by knowledge on mental health (H11), the relationship between familiarity and mental health awareness was mediated by attitude towards mental health (H14), and lastly the relationship between media exposure and mental health awareness was mediated by attitude towards mental health (H15). The three supported indirect effects, β = 0.054, β = 0.042, and β = 0.045 were significant with t-values of 2.074, 2.445, and 2.321. The indirect effects 95% Boot CI Bias Corrected: [LL = 0.014, UL = 0.100], [LL = 0.017, UL = 0.070], and [LL = 0.018, UL = 0.080] did not straddle a zero in between, thus indicating the presence of mediation [111]. Thus, we can conclude that the mediation effects were statistically significant.

However, the results indicated that three indirect effects were not supported, namely the relationship between familiarity and mental health awareness was not mediated by knowledge on mental health (H10), the relationship between familiarity and mental health awareness was not mediated by knowledge on professional help (H12) and the relationship between media exposure and mental health awareness was not mediated by knowledge on professional help (H13). The indirect effects 95% Boot CI Bias Corrected of H12 and H13 are [LL = −0.019, UL = 0.007] and [LL = −0.040, UL = 0.026] respectively which included zero, thus indicating a lack of mediation. Meanwhile, although the indirect effects 95% Boot CI Bias Corrected of H10 [LL = 0.010, UL = 0.073] does not straddle a 0 in between, but the t-value is below 1.96. Thus, the mediation effects were not significant for H10.

5. Discussion

The result of this study indicated that familiarity cast a positive influence on knowledge on mental health. This finding was consistent with the study by Jorm et al. [30], Tahir et al. [42], Li et al. [44] and Abi Doumit et al. [45] which reported an association between familiarity and knowledge on mental health. This finding also shows that secondary school students who experienced mental illness themselves or had contact with acquaintances with mental illness tended to have more information and knowledge on mental health.

In addition, the findings revealed that familiarity had a positive influence on knowledge on professional help. This finding was in accordance with Abi Doumit et al. [45], Ahmed and Baruah [46] and Fischer and Farina [48] who observed a relationship between familiarity and knowledge. In other words, secondary students who encountered other people with a mental health problem or experienced it themselves tend to have a greater knowledge of the services provided by the professionals because they might have come across the services before.

Furthermore, this study also discovered that familiarity had a positive influence on attitude towards mental health. This finding was supported by Abi Doumit et al. [45], Buizza et al. [50] and Ewalds-Kvist et al. [52] who highlighted the association between familiarity and attitude towards mental health. Hence, secondary school students who were familiar with mental illness (experienced it personally or in contact with people who have) were less likely to cast negative stereotypical views and attitudes toward people with mental disorders. With their personal experience, they are likely to have more compassion and a positive attitude toward individuals with mental illness.

Next, the study also reported that media exposure had a positive influence on knowledge on mental health. This finding was consistent with the study of Li et al. [44], Onsomu et al. [57] and Sano et al. [58] which revealed the influence of media exposure on knowledge. In this study, secondary school students gained information from various sources such as newspapers, television programmes, radio, mobile phone apps, websites, and social media platforms. In fact, mass media is an effective technique to raise public knowledge about a particular subject. Hence, this study showed that exposure to various media can improve the knowledge on mental health among youth.

Apart from that, the study results showed that media exposure positively influenced the knowledge on professional help. This finding was consistent with Sano et al. [58], Evans et al. [64] and McCrae et al. [66]. Media exposure to mental health issues can motivate people to seek more information about the illness, including its causes, risks, and treatment, subsequently improving their knowledge of the particular topic [64]. Other studies also revealed that many individuals turned to social media to seek knowledge about mental health treatment choices [67]. Secondary school students in this study perceived media exposure as an important avenue to help them to gain knowledge of different types of professional help available for mental health treatment and recovery.

Moreover, the results highlighted that media exposure casts a positive influence on attitudes toward mental health. This finding is in accordance with the studies by Li et al. [44], Khan and Ali [69] and Srivastava et al. [98]. Media plays a part in alleviating stigma, correcting misinformation, encouraging public debate and discussion, as well as demonstrating positive stories of those who live with mental health issues [60,70,71]. The results also showed that secondary school students in this study agreed that the positive messages delivered by the media influenced their attitude towards mental health issues and prevent them from discriminating against or negatively viewing people with mental health issues.

Knowledge on mental health was confirmed to have a positive influence on mental health awareness. This finding was supported by Jabar et al. [80], Rajamoorthy et al. [81], Guven and Sulun [97] and Kuppusamy and Mari [112] who evaluated the association between knowledge and awareness. In this study, the result suggested that youth at secondary schools with more knowledge on mental health would have a greater awareness of mental health. This is not surprising because access to more information can improve awareness [79]. When youth gained more information regarding mental health topics, they would be more aware of mental health issues. In contrast, people who lack information will have limited awareness of the issue [97]. Thus, the awareness of a subject matter is dependent on the knowledge possessed. The higher the knowledge on mental health, the higher the level of awareness of mental health issues.

On the other hand, the knowledge on professional help was found to have no positive influence on mental health awareness. This was in contrast with previous studies which revealed a significant correlation between knowledge and awareness [97]. One of the possible reasons could be the lack of publicity on the information regarding mental health professionals such as the directory of specialist hospitals and the lists of the helpline. Chandra et al. [113] contended that the most common reason for not considering mental health professionals as a source of help is the lack of awareness about the kind of therapies available. Another possible explanation for this finding could be the low number of study respondents who considered mental health professionals as the primary source of help when dealing with mental health issues. Jorm et al. [84] assessed the beliefs of appropriate first aid for young people with mental disorders and discovered that a substantial number of adolescents did not think that professional help would be beneficial.

With regard to attitude, this study showed that attitude towards mental health cast a positive influence on mental health awareness. This was consistent with Sabouhi et al. [95] and Zhao et al. [96]. As negative attitudes resulted from stigma and misconception, someone with negative attitudes could be assumed to have low awareness of the subject matter. For example, certain individuals perceive people with mental illness as dangerous and violent. Such misconception can be an indication of low awareness of mental health. Mental health awareness programmes strive to eliminate false beliefs, stigma, and misconceptions surrounding mental health issues. When someone does not possess wrong or false belief, negative attitudes, or stigma toward mental illness, then he or she is considered as having mental health awareness. Hence, it can be concluded that secondary school students with better attitudes toward mental health had a greater mental health awareness.

Besides, the results of this study indicated that knowledge on mental health did not play a mediating role between familiarity and mental health awareness. This could mean that familiarising oneself with mental health issues can improve mental health awareness, but it was not due to having knowledge on mental health. In other words, familiarity towards mental health that secondary school students gained will improve their mental health awareness because they have gained something in the process of familiarisation, but it was not mental health knowledge that lead to their increased awareness on mental health. It may be due to other factor such as positive attitude. Perhaps future studies could look into the factors that mediate the relationship between familiarity and mental health awareness.

This study discovered that knowledge on mental health played a mediating role between media exposure and mental health awareness. In fact, the media is known to be a useful tool to improve people's knowledge of a certain topic. For example, HIV-related research showed that media has been critical in increasing people's sexual health knowledge, strengthening their knowledge of HIV prevention services, and emphasising the benefits of HIV testing [57,58]. Thus, media exposure can result in a greater knowledge level of mental health. We found that the knowledge on mental health positively influenced mental health awareness. This result was in line with Corrigan and Shapiro’s [79] findings in which more information led to better awareness. This was further supported by Sabouhi et al. [95] and Guven and Sulun [97] who revealed a significant level of connection between knowledge and awareness. Kuppusamy and Mari [112] further suggested that an awareness of a subject matter depended on the knowledge possessed. Therefore, secondary school students in this study who acquired knowledge on mental health such as signs, symptoms, causes, and outcomes of mental health as well as the ability to recognise and label types of mental disorders from mass media. These knowledges, in turn, influenced their awareness of mental health topics. When they had higher knowledge of a subject matter, they would have a greater awareness of the topic. Thus, media exposure improved mental health awareness with the help of knowledge on mental health.

The results of the study also indicated a lack of mediating role in the knowledge on professional help between familiarity and mental health awareness. This could be due to the fact that the relationship between knowledge on professional help and mental health awareness is not supported as shown in the discussion above, therefore mediating role of knowledge on professional help is not supported as well. This could mean that familiarity toward mental health among secondary school students was associated with mental health awareness but not because they possessed knowledge on professional help. One of the possible reasons was that they did not view professional help as the primary source of help when encountering mental health problems. Instead, they preferred to seek advices and help from their family and friends.

Additionally, the findings showed that knowledge on professional help did not mediate the relationship between media exposure and mental health awareness. As the relationship between knowledge on professional help and mental health awareness was not supported, thus it was likely that the mediating role of the knowledge on professional help was not supported as well. In other words, the media exposure secondary students had to mental health increased their mental health awareness but it was not because of their knowledge on professional help. As abovementioned, the inadequate knowledge about professional help among secondary school students could stem from the fact that they preferred to seek help from their family and friends rather than from healthcare professionals.

As for attitude towards mental health, the results showed that it mediated the relationship between familiarity and mental health awareness. Previous research by Holmes et al. [40] and Corrigan et al. [41] affirmed that having previous contacts with mentally-ill individuals was negatively linked to endorsing psychological stigma. Abi Doumit et al. [45] observed a positive link while assessing familiarity with friends, and close and distant individuals in connection to attitudes and behaviours. Ewalds-Kvist et al. [52] also found that people with mental health problems were more familiar with mental disorders and thus, displayed less stigma toward them. Interpersonal interaction with mentally ill patients may improve attitudes of empathy, alter beliefs, and minimise stereotypes towards these patients [114]. Sabouhi et al. [95] observed a strong association between attitude and awareness when examining the correlation between knowledge, awareness, attitudes, and practices about hypertension among hypertensive patients. Similarly, Zhao et al. [96] discovered a positive correlation between energy-saving attitudes and energy-saving awareness when investigating energy-saving behaviours, attitudes, and awareness among university students. These findings showed that attitude was correlated to awareness. Often, a person with a good awareness of mental health refers to someone with a positive attitude towards mental health, as well as free from stigma and stereotypes. The mediating test provided evidence that the attitude towards mental health played a certain role in the relationship between familiarity and mental health awareness. Hence, secondary school students who were familiar with mental health issues had a good awareness of mental health topics because they possessed the right beliefs, views, and attitudes through familiarisation.

The result of the study indicated that attitude towards mental health played a mediating role between media exposure and mental health awareness. According to previous studies, the media contributed by reducing stigma and correcting misinformation [60,70]. The media is also known as a powerful ally in combating public stigma, encouraging public debate and discussion, and showcasing positive stories of people living with mental health issues [71]. Thus, media exposure has been found to positively influence one’s attitude towards mental health. Our results also highlighted that attitude towards mental health positively influenced mental health awareness. Sabouhi et al. [95] and Zhao et al. [96] observed a strong association between attitude and awareness in their studies. Hence, it is evident that attitude towards mental health positively influenced mental health awareness. This showed that exposure to mass media influenced secondary school students' attitudes toward mental health, be it positive or negative attitude. In turn, this affected their awareness of mental health topics. Secondary school students with a positive attitude had a greater awareness of mental health issues than those with a negative attitude. In other words, exposure to media regarding mental health topics can improve secondary students' awareness of the subject matter as they have cultivated positive attitudes towards mental health issues, thus resulting in better mental health awareness.

6. Theoretical and practical implications

Despite a significant increase in the literature on mental health, there is a lack of studies focusing on mental health awareness. The findings of this research contributed to the existing knowledge on mental health by providing a comprehensive understanding of the impact of knowledge on mental health, knowledge on professional help, and attitude towards mental health on mental health awareness. This study also tested the indirect association of familiarity and media exposure on mental health awareness through the mediating roles of knowledge on mental health, knowledge on professional help, and attitude towards mental health. Besides, this study contributed to the existing literature by expanding the SLT, a relatively new theory in the context of mental health, especially for developing countries like Malaysia. Hence, the use of SLT to predict mental health awareness in this study enriched the scarce literature and knowledge in this contemporary field. It added important input to the field of mental health and provided a deeper understanding of the existing studies.

Next, the findings of this research concluded that familiarity has a positive influence on knowledge and attitude, as well as an indirect influence on mental health awareness. Previous studies have shown that social support and connection with others who share similar experiences can help individuals who are dealing with mental health problems. Misconceptions about mental health patients may be alleviated by communicating with other people in supportive communities. Hence, a contact-based group intervention in which adolescents may learn about mental illness from someone who has recovered from mental illness can be held at schools. The goal of this session is to encourage contact between adolescents and those who have lived with mental illness to improve their awareness.

Besides, the study findings also suggested that media exposure has a positive influence on knowledge and attitude, as well as an indirect influence on mental health awareness. Therefore, it is pivotal that the media outlets play their parts in sharing the right knowledge with the public in the process of shaping the right attitude towards mental health. Media also plays a part in debunking stigmas related to mental health. According to the Malaysian National Strategic Plan for Mental Health 2020–2025, the eighth strategy focuses on addressing suicide and suicidal behaviour. One of the suggested actions is to promote responsible media reporting on mental illness. Media professionals should think carefully when reporting or portraying mental health issues, such as the inclusion of scenes depicting people with mental illnesses in movies. Besides, information regarding mental health should be distributed on the appropriate media platforms to promote public awareness. Mental health professionals can help to raise public awareness by translating study findings into simpler language that can be easily shared through the media and understood by the public.

Furthermore, the study findings showed that knowledge on mental health is an important factor and mediator of mental health awareness. To implement intervention programmes that can increase students' knowledge on mental health, schools play an important role because teenagers and young people spend most of their time in schools. Firstly, schools can organise educational talks by clinical psychologists, psychiatrists, consumer-educators or carer-educators for the students. Training and seminars can also be held to share mental health knowledge, to instil the right attitude towards mental health, and thus to enhance mental health awareness. Secondly, schools should organise mental health awareness programmes whereby educators can use various tools such as booklets, pamphlets, slideshows, and videos as interventions. Group or individual tasks can also be given during the intervention. School-based awareness programmes have been linked with good outcomes in several settings. In the Malaysian National Strategic Plan for Mental Health 2020–2025, the fifth strategy focuses on establishing and nurturing intra- and inter-sectoral collaboration. One of the suggested actions involved the incorporation of mental health topics into the school curriculum and co-curriculum activities. Successful intervention programmes should be replicated across all schools. More importantly, school teachers must be educated first. The fourth strategy in the Malaysian National Strategic Plan for Mental Health 2020–2025 focuses on strengthening mental health resources, i.e. to equip teachers with appropriate knowledge, attitude, and skills for mental wellbeing. For instance, in the training programme for teachers, mental health should be integrated into the educational psychology and child psychology subjects. Teachers and other school staff should also receive continuous education in mental health topics.

In 2015, Malaysia adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (2030 Agenda) at the United States General Assembly in New York. The third Sustainable Development Goal is on good health and wellbeing, which is to ensure healthy lives and to promote wellbeing for people of all ages. Thus, our findings will provide useful information to assist government agencies, especially the Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health, and Ministry of Youth and Sports to implement comprehensive intervention and preventive programmes. For instance, counsellors with the necessary psychological skills should be trained and stationed in schools to provide the necessary support. Other strategies must also be undertaken to improve the current support system for youth who face mental health problems.

According to the Psychiatric and Mental Health Service Operational Policy of the Ministry of Health Malaysia, regular activities such as healthy lifestyle campaigns and World Mental Health Day should be carried out. However, these activities seldom receive enough media coverage to boost public participation. More efforts should be done to ensure these campaigns and programmes receive widespread attention and participation. Besides, even though the websites of the Malaysian Mental Health Malaysia Association, Malaysian Psychiatry Association, and the Ministry of Health Malaysia provide mental health information to the general public in various languages, many people are unaware of such information due to a lack of publicity. To enhance accessibility, good websites pertaining to mental health concerns should be promoted through various media.

7. Limitations and future recommendations

As only students from 12 secondary schools from Kuala Lumpur and Melaka were included in this study, the results cannot be generalised to the entire youth population in Malaysia. It is recommended that future research expands the study population by using probability sampling to recruit more students from all secondary schools in the country. All the elements in the desired population have equal chances of being selected as a sample when using probability sampling. As a result, the population may be represented more accurately. Furthermore, we did not include sufficient independent variables to adequately evaluate the associated factors of mental health awareness among the students. To obtain a better understanding of factors that improve mental health awareness, future researchers should also include more variables in the study. Moreover, out of the six mediation hypothesis, only three were supported, and the effects were small. It was recommended that future studies could look into improving the mediation effects. It was also recommended that future research look into other factors that mediate the relationship between familiarity and mental health awareness as well as between media exposure and mental health awareness. Besides, the response rates based on age might also potentially affect the internal and external validity, as well as the extent to which the findings can be generalised. The samples mostly comprised students aged 16 years old who might be less knowledgeable regarding mental health issues than older students. Future researchers are recommended to obtain the same number of students of different ages to reduce the bias in the findings. Moreover, this study also could not provide a qualitative perspective of the factors influencing the mental health awareness of Malaysian as only the quantitative methodology was applied in this study. Future research should include a mixed-method approach. The inclusion of a qualitative study can add breadth and depth to the topic of the perceptions and feelings of students regarding mental health issues.

8. Conclusion

Mental health is a major public health concern. Effective public mental health strategies and actions are needed to reduce the current and future disease burden in terms of prevalence and cost. Mental health is just as important as physical health. Therefore, mental health awareness must be strongly advocated so that individuals can understand their symptoms, seek professional treatment, and most importantly, break the mental health stigma so that no one will continue to suffer in silence.

Author contribution statement

Lee Jia En: Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Goh Mei Ling: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Yeo Sook Fern: Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Funding statement

The author would like to thank the Malaysian Ministry of Higher Education for providing the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (No: FRGS/1/2020/SS02/MMU/03/4) to fund this research.

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Ritchie H., Roser M., Dattani S. 2018. Mental Health.https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health (Our World in Data). Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . WHO; 2021. Adolescent Mental Health.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrari A.J., Norman R.E., Freedman G., Baxter A.J., Pirkis J.E., Harris M.G., et al. The burden attributable to mental and substance use disorders as risk factors for suicide: findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Baune BTP, editor. PLoS One. 2014;9(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute for Public Health. National Health and Morbidity Survey 2017 (NHMS 2017): Adolescent Mental Health (DASS-21).

- 5.Institute for Public Health (IPH), National Institutes of Health, Ministry of Health Malaysia . 2020. National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2019: Vol. I: NCDs – Non-communicable Diseases: Risk Factors and Other Health Problems. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards V.J., Holden G.W., Felitti V.J., Anda R.F. Relationship between multiple forms of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: results from the adverse childhood experiences study. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2003;160(8):1453–1460. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibb B.E., Chelminski I., Zimmerman M. Childhood emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, and diagnoses of depressive and anxiety disorders in adult psychiatric outpatients. Depress. Anxiety. 2007;24(4):256–263. doi: 10.1002/da.20238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uba I., Yaacob S.N., Juhari R., Talib M.A. Effect of self-esteem on the relationship between depression and bullying among teenagers in Malaysia. Asian Soc. Sci. 2010;6(12) doi: 10.5539/ass.v6n12p77. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bröder J., Okan O., Bauer U., Bruland D., Schlupp S., Bollweg T.M., et al. Health literacy in childhood and youth: a systematic review of definitions and models. BMC Publ. Health. 2017;17(1) doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4267-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.SWHELPER . SWHELPER; 2015 Nov 17. The Importance of Mental Health Awareness.https://swhelper.org/2015/11/17/importance-mental-health-awareness/ Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam L.T. Mental health literacy and mental health status in adolescents: a population-based survey. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Ment. Health. 2014;8(1):26. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-8-26. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel V., Parikh R., Nandraj S., Balasubramaniam P., Narayan K., Paul V.K., Kumar A.K.S., et al. Assuring health coverage for all in India. Lancet. 2015;386(10011):2422–2435. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00955-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rebello T.J., Marques A., Gureje O., Pike K.M. Innovative strategies for closing the mental health treatment gap globally. Curr. Opin. Psychiatr. 2014;27(4):308–314. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dev A., Gupta S., Sharma K.K., Chadda R.K. Awareness of mental disorders among youth in Delhi. Curr. Med. Res. Pract. 2017;7(3):84–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cmrp.2016.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swetaa A., Gayathri R., Priya V.V. Awareness of mental health among teenagers. Drug Invent. Today. 2019;11(8):2022–2024. doi: 10.1016/j.dit.2019.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]